Introduction

Inter- and intracellular events such as inhibition of apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation, and inflammation are involved in the development of neoplastic processes [

1]. In the specific case of inflammation, the presence of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-alpha has been reported in the tumour environment for various cancers [

2]. These cytokines are produced by immune cells that are attracted to the niche in which cancer cells develop and may also be secreted by the same cells that comprise the niche [

3,

4]. Increased IL-1β expression has been reported in several cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer, and chronic myeloid leukaemia [

5,

6,

7]. Once IL-1β is recognised by its receptor in the cell, it initiates a signalling cascade involving kinases and transcription factors, such as NF-κB, which regulate the expression of various genes involved in apoptosis, proliferation, and inflammation [

8].

ALL is a hematopoietic neoplasm that originates in the bone marrow and subsequently spreads to the lymph nodes, spleen, and central nervous system [

9].

While the effect of IL-1β on lymphoblasts from ALL has not been reported, it has been found to induce NF-κB and PI3K activation in other types of neoplasia, such as liver cancer, and has also been shown to influence NF-κB activation [

10]. Another study reported that Src kinase induces NF-κB activation and IL-6 expression in cells undergoing Src oncogene-dependent transformation [

11]. The possible effects of NF-κB activation mentioned above may help neoplastic cells to remain and develop in the niche in which they arose.

This study aimed to investigate whether the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β, through kinases such as PI3K/Akt, Src, and NF-κB, affects cell death and proliferation in leukaemic lymphoblasts. We found that this cytokine inhibits early apoptosis and limits necroptosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts while increasing proliferation, in a manner mediated by the activity and activation of PI3K, AKT, Src, and NF-κB.

Discussion

As they secrete molecules such as proinflammatory cytokines and interferons, promoting a chronic inflammatory state that fosters the formation of a tumour microenvironment, the cells that constitute the immune system play a crucial role in the establishment and development of cancer [

20]. The increased expression of IL-1β has been observed in chronic myeloid leukaemia [

21], and autocrine secretion of IL-1β has even been reported in cell lines derived from chronic monocytic leukaemia and ALL [

22]. Reports have indicated that the presence of IL-1β is related to the activation of PI3K/AKT in different cancers [

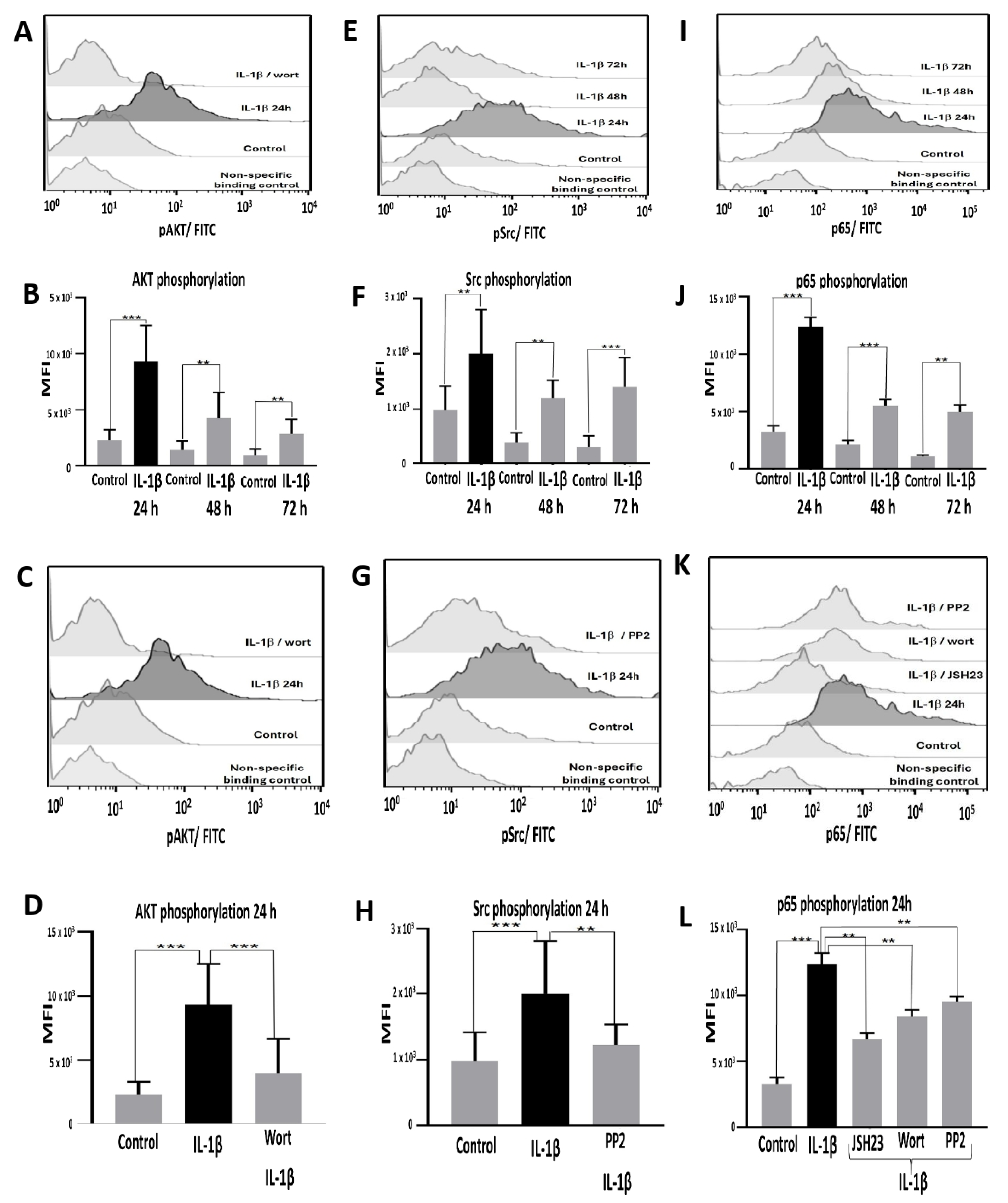

23]. In addition, in 2007, Lin pointed out the relationship between IL-6 and Src in gastric cancer. Considering this evidence, we tested whether IL-1β induced the activation of AKT and Src in lymphoblasts derived from ALL, discovering that this interleukin effectively induced a significant increase in the activation of both kinases [

24]. Therefore, we investigated whether exposure to IL-1β could induce the activation of NF-κB and found that this interleukin induced the highest increase in NF-κB activation in RS4:11 leukaemic lymphoblasts. This finding is consistent with observations in breast cancer, where IL-1β and NF-κB have been reported to be associated with the progression of this type of neoplasm [

25].

These results led us to consider a possible signalling pathway in which IL-1β could trigger the activation of NF-κB. Subsequently, we tested whether the activation of these kinases, due to the presence of IL-1β, could be involved in the activation of NF-κB in lymphoblasts. As a result, we found that inhibiting PI3K and Src significantly decreased NF-κB activation. It has been reported separately in breast and cervical cancer cell lines that PI3K–AKT activates NF-κB, and in liver cancer that Src is involved in the activation of this nuclear factor [

26,

27,

28]; therefore, these reports support our findings. However, in this study, we showed in the same ALL cell model that IL-1β triggers a signalling pathway involving PI3K/AKT/Src/NF-κB—an observation that has not yet been reported for any leukaemia.

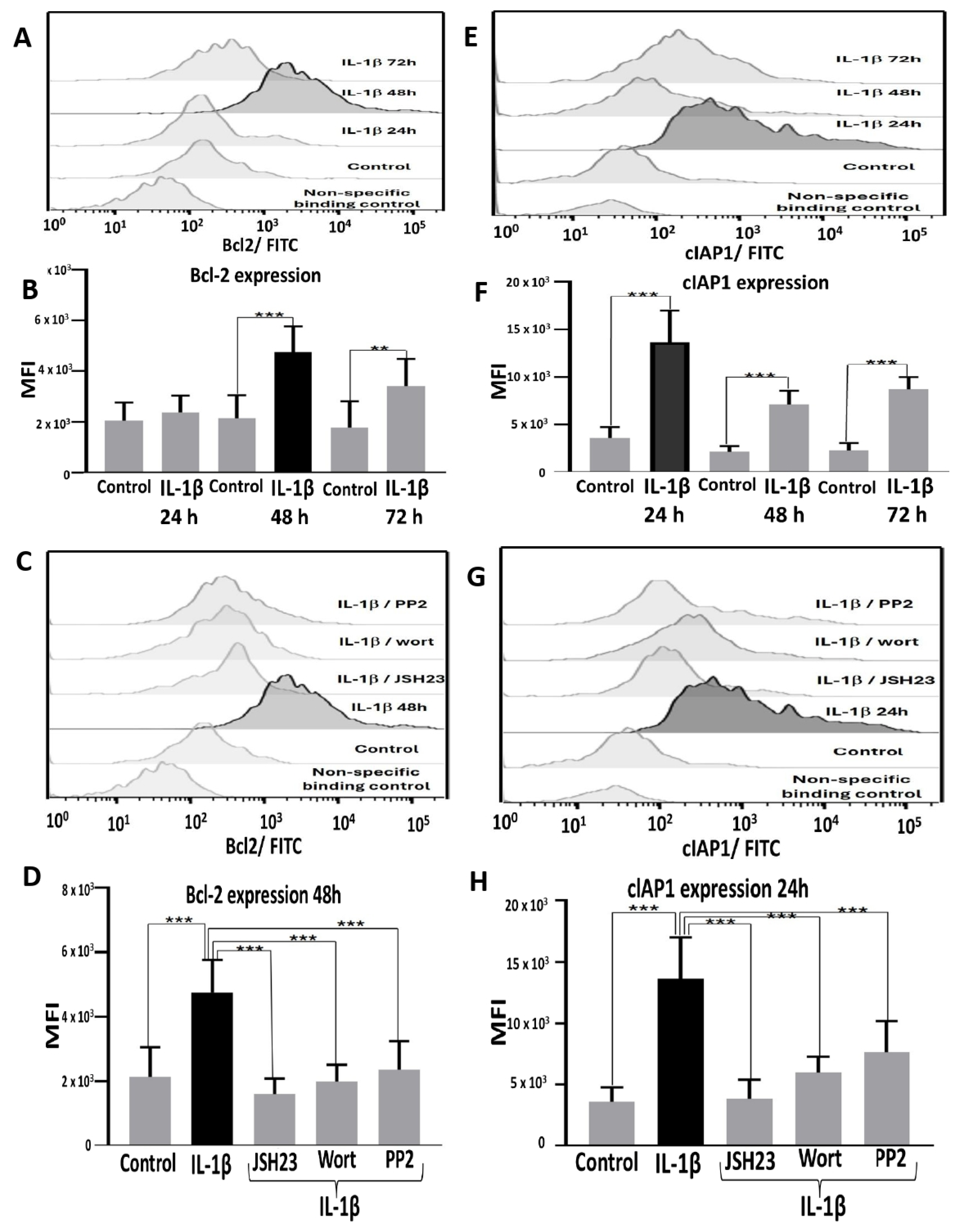

On the other hand, it has previously been suggested that a general inflammatory environment may be related to some intrinsic characteristics of neoplastic processes, such as the inhibition of apoptosis and proliferation [

29]. Therefore, we analysed whether IL-1β induces any changes in the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2 and cIAP1, in leukaemic lymphoblasts. We observed that IL-1β triggers a significant increase in the expression of Bcl-2 and cIAP1 in these lymphoblasts; furthermore, when PI3K, Src, and NF-κB were inhibited, the expression of these anti-apoptotic proteins decreased significantly. Several research groups have reported the presence of these anti-apoptotic proteins in various types of neoplasms [

30,

31,

32], suggesting that they may regulate the process of apoptosis. Concerning the relationship between proinflammatory interleukins and apoptosis-regulating proteins, it has been observed that IL-1β induces phosphorylation of Bcl-2 in acute myeloid leukaemia blasts [

21]; on the other hand, in 2002, Spets et al. found that IL-6 induces an increase in the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and MCL-1 in multiple myeloma cells [

33]. These data support our finding that IL-1β is involved in the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins via the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway in leukaemic lymphoblasts.

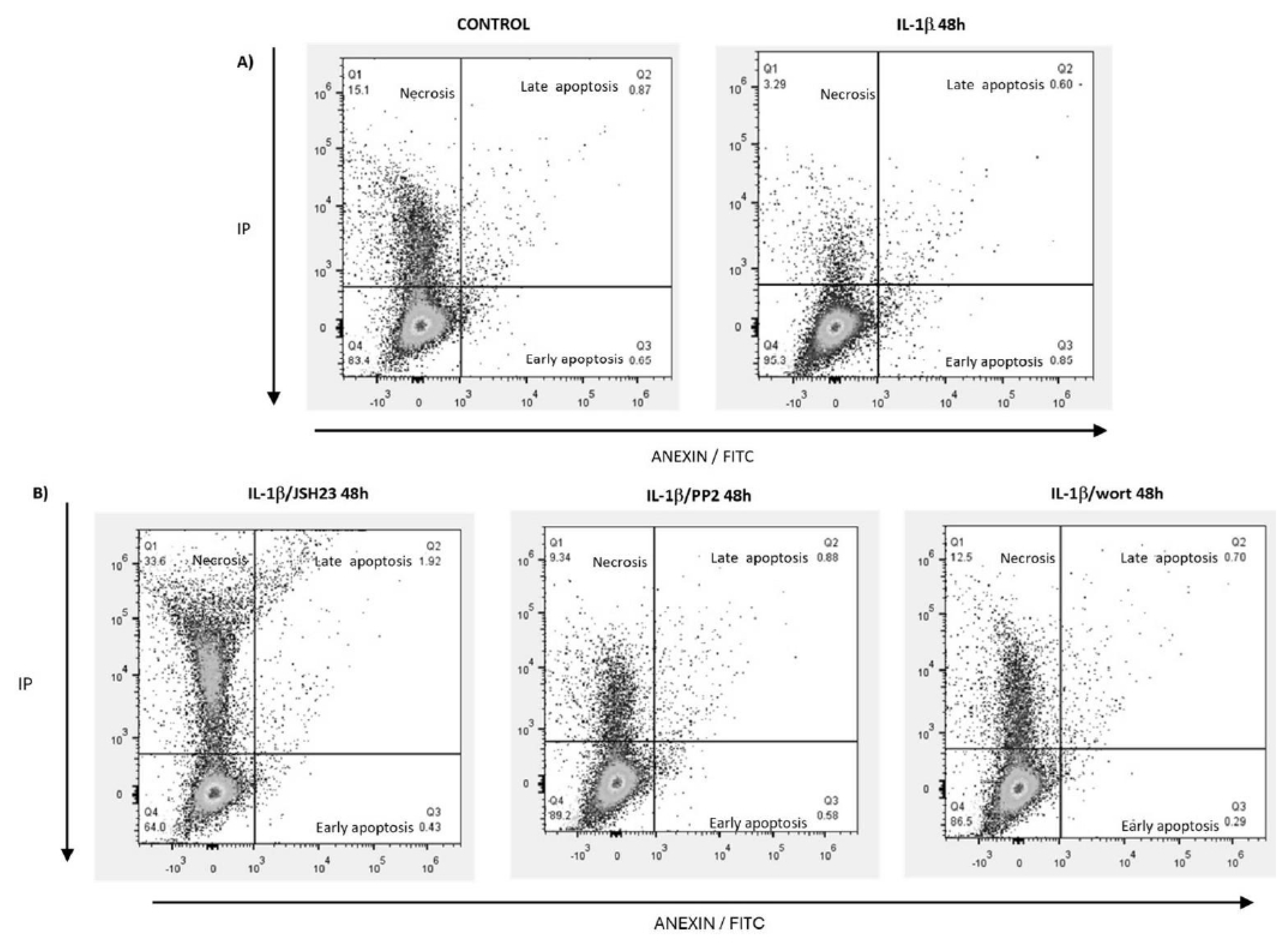

Considering these results, we tested whether this interleukin has any effect on the death of leukaemic lymphoblasts. Our results indicated that IL-1β significantly decreases the number of lymphoblasts in early apoptosis. These findings are consistent with previous work, as it has been reported that Bcl-2 inhibits early apoptosis by preventing the externalisation of phosphatidylserine in the plasma membrane and can also inhibit the action of caspases by inhibiting the release of cytochrome c. It is well-known that cIAP1 inhibits caspases, which act in the first phase of apoptosis [

34,

35]. This observation is similar to that reported by Turzanki et al. in 2004, who found that IL-1β produced by blast cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia causes resistance to apoptosis [

21].

Regarding late apoptosis, no significant differences were observed between leukaemic lymphoblasts treated with or without IL-1β, nor were any differences found between early and late apoptosis in the presence of IL-1β. Taken together, these findings suggest that IL-1β exerts a general inhibitory effect on apoptosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts.

On the other hand, when NF-κB, PI3K, and Src were inhibited in leukaemic lymphoblasts in the presence of IL-1β, we observed that the percentage of lymphoblasts in early apoptosis decreased in general. These data confirm our earlier observations regarding the effects of these kinases and transcription factor on the expression of Bcl-2 and cIAP1.

Concerning the analysis of late apoptosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts treated with IL-1β in the presence of PI3K and Src inhibitors, we note that there was no significant difference in lymphoblasts at this stage of apoptosis—probably because IL-1β does not promote late apoptosis. On the other hand, we found that leukaemic lymphoblasts treated with IL-1β in the presence of the NF-κB inhibitor showed a modest increase in the percentage of lymphoblasts in late apoptosis; as this factor is known to regulate the transcription of proteins involved in the initiation of apoptosis [

8], this increase could be due to the fact that when this transcription factor is inhibited, apoptosis is no longer inhibited and the lymphoblasts can therefore carry it out. Thus, these data also support our observation that IL-1β promotes early apoptosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts via NF-κB.

Likewise, we noted that this interleukin limits necrosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts. As is well-known, the concept of necrosis has evolved into a highly regulated process, now known as necroptosis. Necroptosis involves kinases such as RIPK1, 2, and 3, as well as MLKL [

36]. As cIAP1 has a ubiquitin ligase domain, it can induce the degradation of target proteins [

37]; one of these is RIPK1, which—when ubiquitinated and degraded by this pathway—can result in a decrease in necroptosis [

38]. In this study, we observed that IL-1β induced an increase in the expression of cIAP1 in leukaemic lymphoblasts. On one hand, this protein may prevent early apoptosis; on the other hand, it may limit necrosis by eliminating RIP1K. It is important to note that the expression of RIPK3 and MLKL has been reported in ALL cells and that, when they were genetically suppressed and supplemented with caspase inhibitors, a significant decrease in cell death was observed [

39]. Feldmann et al. (2017) have reported that in ALL cells, sorafenib—a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of acute leukaemia—decreased the phosphorylation of MLKL, resulting in a decrease in cell death [

40]. These data support our theory and suggest that evaluating the expression of RIPK 1 and 3 in our cell model at a later stage could yield further insights.

When we observed the necroptosis of lymphoblasts previously treated with PI3K, Src, and NF-κB inhibitors followed by IL-1β, we found that necroptosis increased under all these conditions compared with lymphoblasts treated only with IL-1β. However, the most significant increase was noted when NF-κB was directly inhibited. These results may be due to NF-κB having cIAP1 as one of its target genes; therefore, inhibiting this transcription factor also decreases the expression of its target genes, including cIAP1 (this effect was observed in this study), which (as mentioned above) likely affects the elimination of RIPK1, thus causing an increase in necroptosis. This effect was similarly observed when PI3K and Src kinases were inhibited, as these kinases influence the activation of this transcription factor. These results further indicate that the necrosis observed when lymphoblasts were treated with IL-1β was influenced by activation of the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signalling pathway, which implies regulation of this pathway. This finding allows us to consider the observed necrosis as necroptosis, as the defining feature that differentiates necroptosis from necrosis is the former is a regulated process. In this regard, we emphasise that our work demonstrates that IL-1β prevents cell death by inhibiting early apoptosis and limiting necroptosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts—a phenomenon which has not been previously reported.

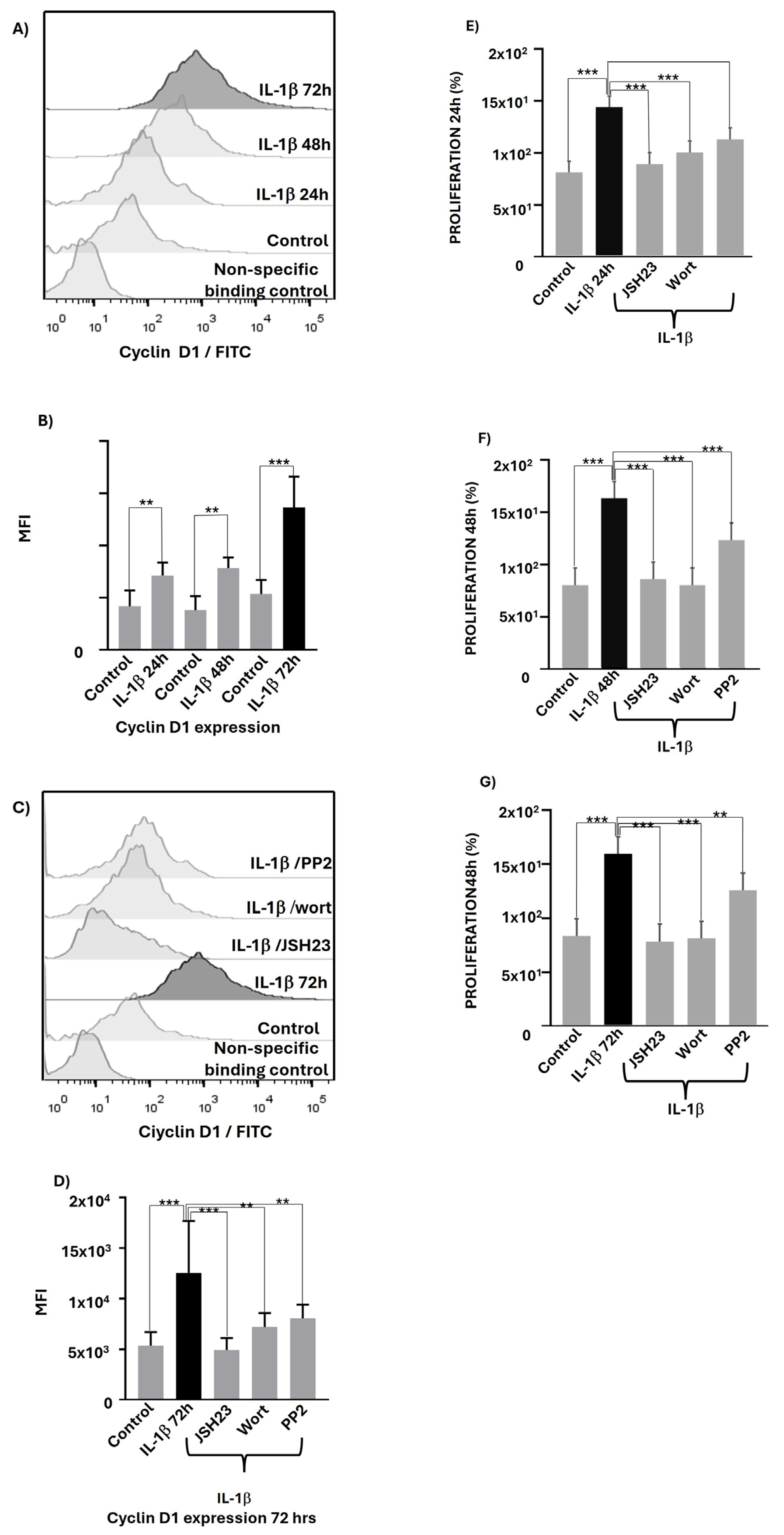

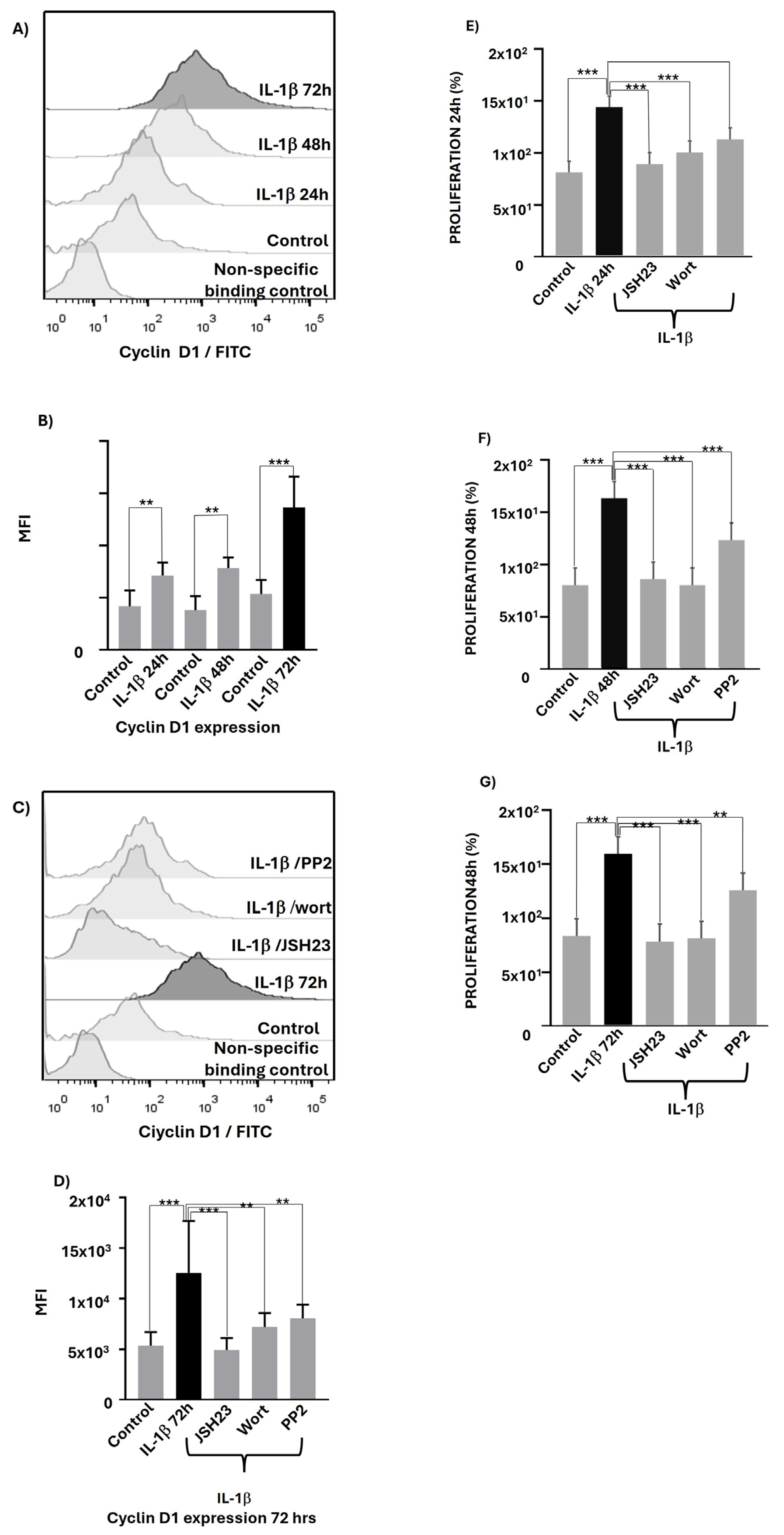

In this study, we also investigated whether IL-1β could have any effect on the expression of proteins related to cell cycle regulation, such as cyclin D1. It has not previously been determined that IL-1β induces an increase in cyclin D expression in any disease or pathology; however, Bousserouel et al. (2004) reported that IL-1β slightly induced cyclin D in an in vitro system using rat muscle cells, and this effect was significantly enhanced upon the addition of arachidonic acid [

41]. It has also been reported that IL-7 promotes the overexpression of cyclin D1 in lung cancer-derived cell lines [

42]. These data align with our finding that a proinflammatory interleukin—namely, IL-1β—induced an increase in cyclin D1 expression in leukaemic lymphoblasts.

On the other hand, the inhibition of PIK3 in myeloma and breast cancer cells resulted in a decrease in cyclin D1 expression [

19,

43]. These data support our observation that PI3K activation, induced by IL-1β in leukaemic lymphoblasts, contributes significantly to cyclin D1 expression.

Different researchers have found that NF-κB induces the transcription of the cyclin D1 gene [

44], supporting our finding that NF-κB inhibition causes a decrease in cyclin D1 expression in IL-1β-treated lymphoblasts. Furthermore, it is known that NF-κB activity may be modulated under the action of PI3K and Src kinases [

23], consistent with our finding that lymphoblasts in the presence of IL-1β and the inhibitors of these kinases significantly decreased cyclin D1 expression. We then tested whether this interleukin influenced the proliferation of these lymphoblasts, and observed that this cytokine induces a significant increase in lymphoblast proliferation. Evidence from both in vivo and in vitro models has demonstrated that SPP1

+ macrophages secrete IL-1β, which subsequently promotes the proliferation of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [

45]. Similarly, Teixeira et al. (2019) observed that silencing of NF-κB1 gene expression inhibited proliferation through the downregulation of IL-1β in renal cell carcinoma [

46]. These data support our finding that IL-1β can induce lymphoblast proliferation; in our model, this effect is most likely related to the observed increase in Cyclin D1 expression.

Finally, we found that the inhibition of PI3K, Src, and NF-κB induced decreases in the proliferation of lymphoblasts treated with IL-1β. These results can also be explained by the fact that these kinases are involved in the activation of NF-κB which, in turn, induces the expression of cyclin D1. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the greatest percentage of inhibition in the expression of this cyclin in leukaemic lymphoblasts treated with IL-1β was observed when NF-κB and PI3K were inhibited. This finding is consistent with reports in other types of cancers regarding the regulation of Cyclin D by PI3K and NF-κB [

43,

44]. In the case of Src kinase inhibition, it was observed that its inhibition in leukaemic lymphoblasts treated with IL-1β reduced the expression of this cyclin by an average of 50%, indicating that IL-1β does not fully induce the activation of this kinase.

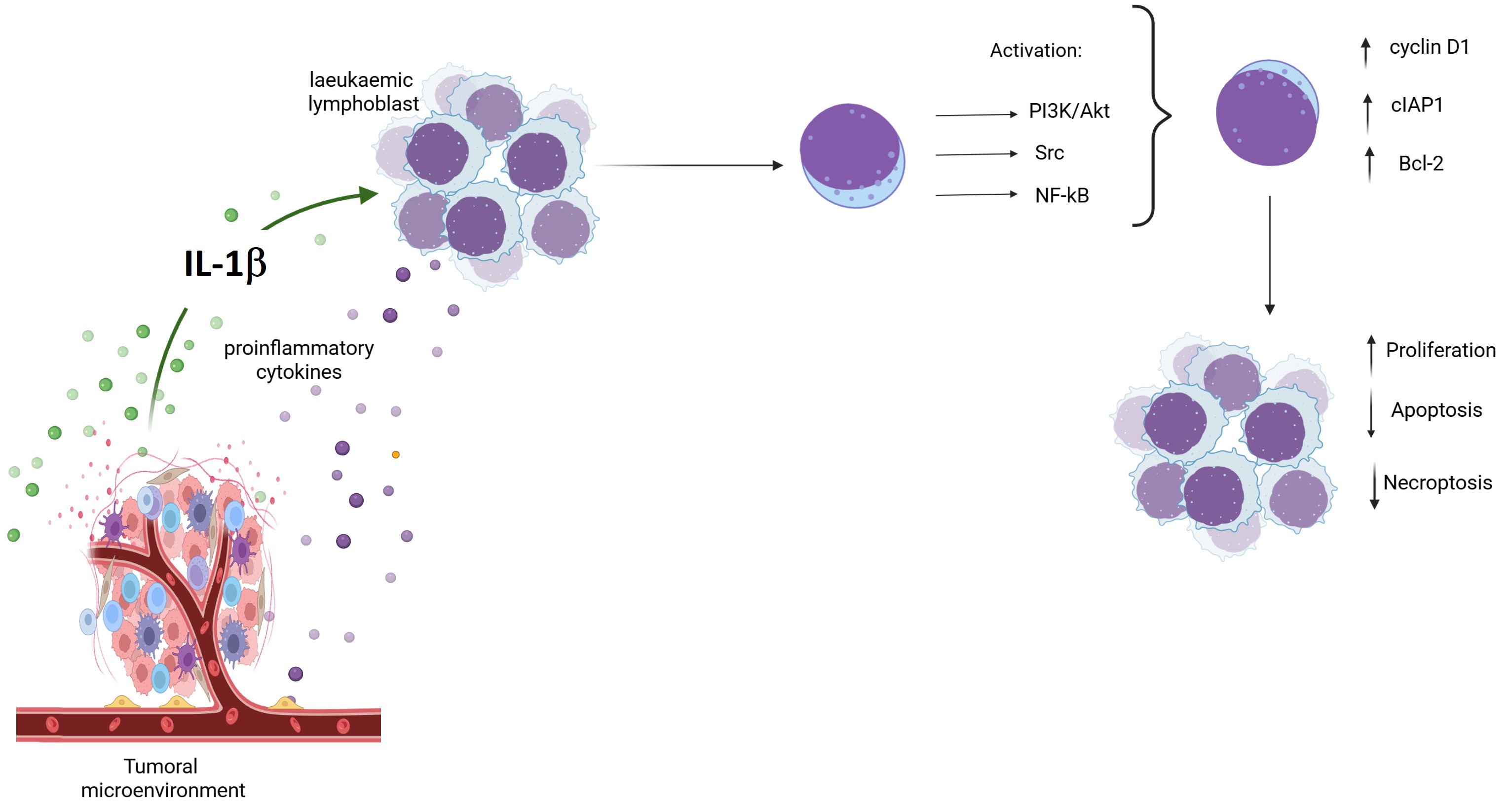

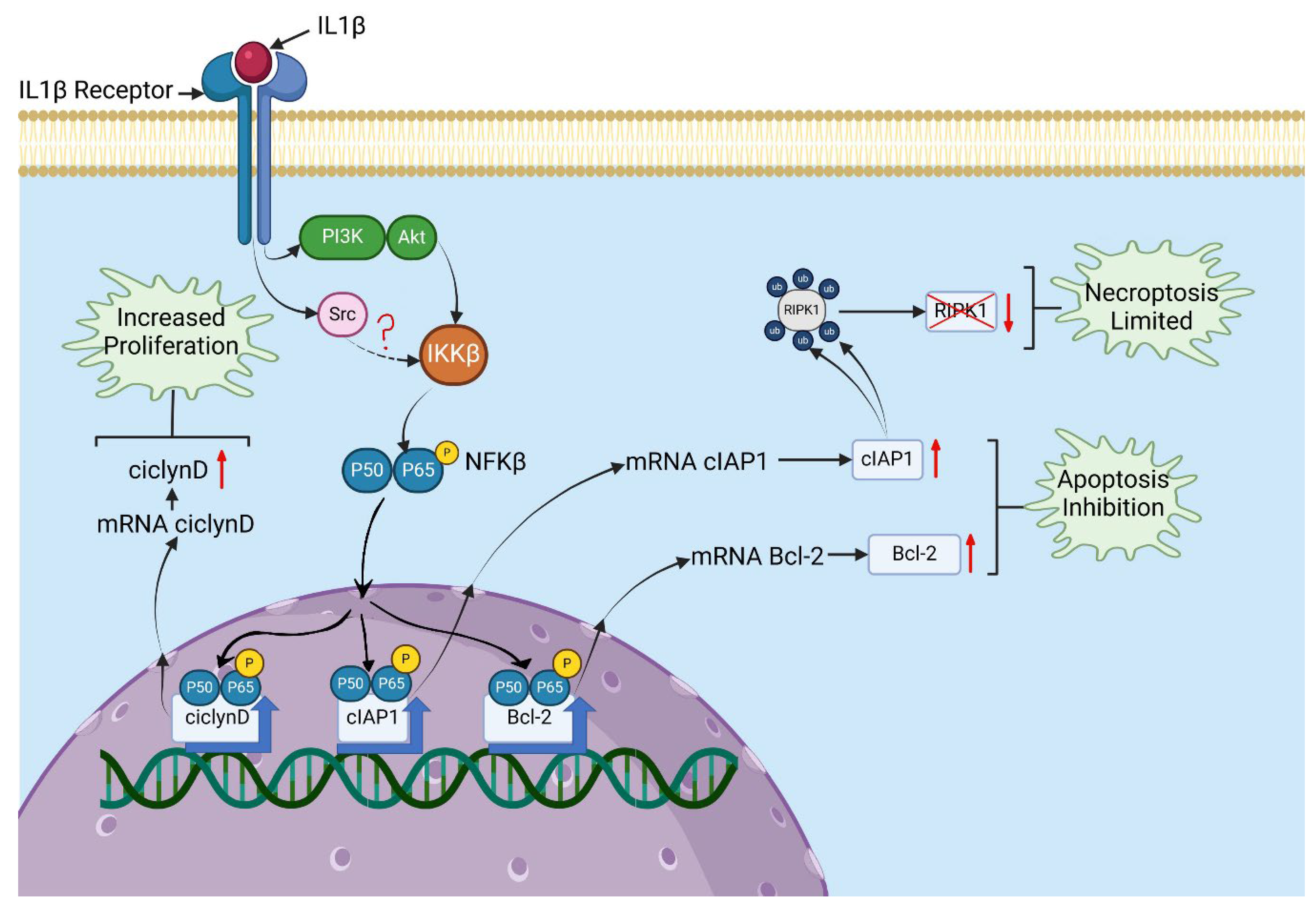

Considering all our results and the data already reported in the literature, we can propose a model of a signalling pathway in leukaemic lymphoblasts which is triggered by IL-1β and involves PI3K/AKT/Src/NF-κB, with effects on the regulation of cell death and lymphoblast proliferation. This pathway can be explained as follows: in the presence of IL-1β, the PI3K/AKT and Src kinases are activated in leukaemic lymphoblasts, which then activate IKKβ. The activation of IKKβ causes p65 translocation to the nucleus [

47] and induces the transcription of its target genes, including Cyclin D1, Bcl-2, and cIAP1 [

48]. The increase in Cyclin D1 expression could be involved in the observed increase in proliferation. Similarly, the increases in Bcl2 and cIAP1 expression could be related to the decrease in early apoptosis, and cIAP1 may also be involved in limiting necroptosis through the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of RIPK1 (see

Figure 5).

The presence of an inflammatory environment in the cellular niche where leukaemia cells appear or develop may contribute to their neoplastic characteristics. The role of proinflammatory cytokines and the proteins involved in the signalling pathways triggered by these molecules are related to the malignant abilities of these cells; therefore, this field of research points to possible therapeutic targets that may be of great benefit in the treatment of patients with this or other types of neoplasm.

Finally, our work demonstrates how a proinflammatory cytokine can influence the reduction in apoptosis and necroptosis while simultaneously increasing the proliferation of leukaemic lymphoblasts via the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway. However, it is also necessary to determine whether other proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 or TNF-α, have similar effects and through which signalling pathways they may act. Furthermore, understanding the additional effects of proinflammatory cytokines is crucial; for instance, whether they are involved in a possible epithelial–mesenchymal transition, which could enable leukaemic lymphoblasts to migrate to other organs and facilitate metastasis. However, this remains a hypothesis to be validated.

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

Figure 1.

IL-1β induces increased activation of AKT, Src, and NF-κB in RS4:11 leukaemic lymphoblasts. (A, E, I) Representative histograms obtained through flow cytometry showing AKT, Src, and p65 subunit of NF-κB phosphorylation in leukaemic lymphoblasts at 24, 48, and 72 hours of culture with IL-1β. (B, F, J) MFI analysis of phosphorylated AKT, Src, and p65 at 24, 48, and 72 hours of culture with IL-1β. (C, G, K) Representative histograms illustrating phosphorylation of AKT, Src, and p65 after 24 hours of culture with IL-1β in the presence of inhibitors of PI3K (wortmannin), Src (PP2), and NF-κB (JSH23). (D, H, L) MFI analysis of AKT, Src, and phosphorylated p65 after 24 hours of culture with IL-1β in the presence of the inhibitors wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. All results are the mean from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. ***p< 0.01 vs. control, **p< 0.02 vs. control.

Figure 1.

IL-1β induces increased activation of AKT, Src, and NF-κB in RS4:11 leukaemic lymphoblasts. (A, E, I) Representative histograms obtained through flow cytometry showing AKT, Src, and p65 subunit of NF-κB phosphorylation in leukaemic lymphoblasts at 24, 48, and 72 hours of culture with IL-1β. (B, F, J) MFI analysis of phosphorylated AKT, Src, and p65 at 24, 48, and 72 hours of culture with IL-1β. (C, G, K) Representative histograms illustrating phosphorylation of AKT, Src, and p65 after 24 hours of culture with IL-1β in the presence of inhibitors of PI3K (wortmannin), Src (PP2), and NF-κB (JSH23). (D, H, L) MFI analysis of AKT, Src, and phosphorylated p65 after 24 hours of culture with IL-1β in the presence of the inhibitors wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. All results are the mean from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. ***p< 0.01 vs. control, **p< 0.02 vs. control.

Figure 2.

IL-1β induces Bcl-2 and cIAP1 overexpression in RS4:11 leukaemic lymphoblasts via PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway. (A, E) Representative flow cytometry histograms showing Bcl-2 and cIAP1 expression at 24, 48, and 72 hours in leukaemic lymphoblasts treated with IL-1β. (B, F) MFI analysis of Bcl-2 and cIAP1 expression at the same time points with IL-1β. (C, G) Representative histogram of Bcl-2 expression at 48 hours with IL-1β in the presence of the inhibitors wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. (D, H) MFI analysis of Bcl-2 at 48 hours and cIAP1 at 24 hours under the same conditions. All results are the means of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. ***p< 0.01 vs. control, **p< 0.02 vs. control.

Figure 2.

IL-1β induces Bcl-2 and cIAP1 overexpression in RS4:11 leukaemic lymphoblasts via PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway. (A, E) Representative flow cytometry histograms showing Bcl-2 and cIAP1 expression at 24, 48, and 72 hours in leukaemic lymphoblasts treated with IL-1β. (B, F) MFI analysis of Bcl-2 and cIAP1 expression at the same time points with IL-1β. (C, G) Representative histogram of Bcl-2 expression at 48 hours with IL-1β in the presence of the inhibitors wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. (D, H) MFI analysis of Bcl-2 at 48 hours and cIAP1 at 24 hours under the same conditions. All results are the means of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. ***p< 0.01 vs. control, **p< 0.02 vs. control.

Figure 3.

IL-1β inhibits early apoptosis and limits necroptosis in RS4:11 leukaemic lymphoblasts via PI3K/AKT/Src/ NF-κB. (A) Representative dot plots showing analysis of apoptosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts incubated in the presence and absence (control) of IL-1β at 48 hours. The procedure was performed using flow cytometry with an Annexin V probe and labelling with propidium iodide (PI) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). (B) Representative dot plots illustrating analysis of apoptosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts incubated for 48 hours with IL-1β in the presence of wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. All results are the means of three independent experiments, with each experimental condition performed in triplicate.

Figure 3.

IL-1β inhibits early apoptosis and limits necroptosis in RS4:11 leukaemic lymphoblasts via PI3K/AKT/Src/ NF-κB. (A) Representative dot plots showing analysis of apoptosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts incubated in the presence and absence (control) of IL-1β at 48 hours. The procedure was performed using flow cytometry with an Annexin V probe and labelling with propidium iodide (PI) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). (B) Representative dot plots illustrating analysis of apoptosis in leukaemic lymphoblasts incubated for 48 hours with IL-1β in the presence of wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. All results are the means of three independent experiments, with each experimental condition performed in triplicate.

Figure 4.

IL-1β induces cyclin D1 overexpression and increases proliferation in RS4:11 leukaemic lymphoblasts via PI3K/AKT/Src/NF-κB. (A) Representative histogram of cyclin D1 expression in leukaemic lymphoblasts cultured with IL-1β at 24, 48, and 72 hours, measured via flow cytometry. (B) MFI analysis of cyclin D1 expression at 24, 48, and 72 hours with IL-1β. (C) Representative histogram of cyclin D1 expression at 72 hours cultured with IL-1β in the presence of inhibitors wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. (D) MFI analysis of cyclin D1 expression at 72 hours with IL-1β in the presence of wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. (E) Percentage analysis of leukaemic lymphoblast proliferation after incubation with IL-1β for 24 hours and IL-1β in the presence of wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. (F) Percentage analysis of leukaemic lymphoblast proliferation incubated with IL-1β for 48 hours and IL-1β plus the same inhibitors. (G) Percentage analysis of leukaemic lymphoblast proliferation incubated with IL-1β for 72 hours and IL-1β plus the same inhibitors. All results are the means of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. ***p< 0.01 vs. control, **p< 0.02 vs. control.

Figure 4.

IL-1β induces cyclin D1 overexpression and increases proliferation in RS4:11 leukaemic lymphoblasts via PI3K/AKT/Src/NF-κB. (A) Representative histogram of cyclin D1 expression in leukaemic lymphoblasts cultured with IL-1β at 24, 48, and 72 hours, measured via flow cytometry. (B) MFI analysis of cyclin D1 expression at 24, 48, and 72 hours with IL-1β. (C) Representative histogram of cyclin D1 expression at 72 hours cultured with IL-1β in the presence of inhibitors wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. (D) MFI analysis of cyclin D1 expression at 72 hours with IL-1β in the presence of wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. (E) Percentage analysis of leukaemic lymphoblast proliferation after incubation with IL-1β for 24 hours and IL-1β in the presence of wortmannin, PP2, and JSH23. (F) Percentage analysis of leukaemic lymphoblast proliferation incubated with IL-1β for 48 hours and IL-1β plus the same inhibitors. (G) Percentage analysis of leukaemic lymphoblast proliferation incubated with IL-1β for 72 hours and IL-1β plus the same inhibitors. All results are the means of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. ***p< 0.01 vs. control, **p< 0.02 vs. control.

Figure 5.

Signalling pathway triggered by IL-1β affecting proliferation and death in leukaemic lymphoblasts. A model is proposed based on the results obtained in this study and previously reported data regarding targeting of PI3K/AKT on IKKβ, Src on IKKβ, and IKKβ on the p65 subunit of NF-κB, leading to its translocation to the nucleus. IL-1β binds to its receptor on leukaemic lymphoblasts, recruiting and activating PI3K/AKT and Src at this receptor. These kinases then activate IKKβ, which phosphorylates the p65 subunit of NF-κB, causing it to translocate to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, NF-κB induces the transcription of target genes such as cyclin D1, Bcl-2, and cIAP1. Overexpression of cyclin D1 can increase proliferation. Higher levels of Bcl-2 and cIAP1 may be associated with inhibition of apoptosis, and cIAP1 might also help to limit necroptosis.

Figure 5.

Signalling pathway triggered by IL-1β affecting proliferation and death in leukaemic lymphoblasts. A model is proposed based on the results obtained in this study and previously reported data regarding targeting of PI3K/AKT on IKKβ, Src on IKKβ, and IKKβ on the p65 subunit of NF-κB, leading to its translocation to the nucleus. IL-1β binds to its receptor on leukaemic lymphoblasts, recruiting and activating PI3K/AKT and Src at this receptor. These kinases then activate IKKβ, which phosphorylates the p65 subunit of NF-κB, causing it to translocate to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, NF-κB induces the transcription of target genes such as cyclin D1, Bcl-2, and cIAP1. Overexpression of cyclin D1 can increase proliferation. Higher levels of Bcl-2 and cIAP1 may be associated with inhibition of apoptosis, and cIAP1 might also help to limit necroptosis.

Table 1.

IL-1β inhibits early apoptosis and limits necroptosis through PI3K/AKT/Src/NF-κB.

Table 1.

IL-1β inhibits early apoptosis and limits necroptosis through PI3K/AKT/Src/NF-κB.

| Treatment |

Viable cells (%) |

Early apoptosis (%) |

Late apoptosis (%) |

Necrosis (%) |

| Control |

66.11+/- 7.0 |

5.0 +/- 0.08 |

0.84 +/- 0.10 |

13.54 +/- 2.7 |

| IL-1β |

89.76 +/- 5.0 |

0.90 +/- 0.06 |

0.91 +/- 0.33 |

5.0 +/- 1.9 |

| IL-1β+JSH23 |

66.47 +/- 7.3 |

0.53 +/- 0.12 |

1.9 +/- 6.16 |

30.5 +/- 3.8 |

| IL-1β + PP2 |

84.90 +/- 6.4 |

0.62 +/- 0.10 |

0.83 +/- 0.09 |

10.53 +/- 2.3 |

| IL-1β + Wort |

85.50 +/- 5.4 |

0.24 +/- 0.05 |

0.75 +/- 0.07 |

12.7 +/- 1.3 |