1. Introduction: The Imperative for Non-Animal Models in Breast Cancer Research

1.1. The Challenge of Metastatic Breast Cancer (MBC)

Metastatic breast cancer (MBC) represents an aggressive and complex clinical scenario, characterized by significant challenges and often limited success in treatment [

1]. Globally, breast cancer is the most common malignancy among women and a leading cause of cancer-associated mortality [

2]. The genetic heterogeneity of disease and variable clinical behavior further complicates the identification of effective treatments [

1,

3]. A particularly challenging aspect is the frequent metastasis of breast cancer to distant sites such as bones, lungs, liver, and brain, especially in advanced stages. These metastatic lesions often exhibit poor responsiveness to conventional chemotherapy, rendering standard treatments ineffective [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The inherent aggressiveness and complex heterogeneity of MBC, coupled with the poor response of metastatic sites to conventional chemotherapy, highlight a critical gap in the understanding and modeling of this disease. This situation underscores the urgent need for more accurate and predictive preclinical models that can better recapitulate the disease’s complexity, particularly its metastatic progression and response to therapeutic interventions.

1.2. Limitations of Conventional 2D Cell Cultures and Animal Models

For decades, preclinical breast cancer research has largely relied on conventional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures and animal models. While 2D cell models have contributed to early-stage drug discovery, they possess substantial limitations. These models fail to represent the crucial stromal cell population, lack a three-dimensional (3D) structure, and offer a poor representation of both inter-tumor and intra-tumor heterogeneity [

4,

7,

8]. Cells cultured in 2D environments undergo morphological changes and cytoskeletal rearrangements, leading to artificial polarity and aberrant gene and protein expression, which severely limit their translational power to human disease [

9]. Furthermore, they cannot mimic the physiological gradients of nutrients, oxygen, and drug penetration that are characteristic of

in vivo tumors [

10].

Animal models, predominantly murine models and xenografts have been widely used in basic research to understand tumor biology and evaluate therapies [

1,

11,

12]. However, these models also present substantial drawbacks. Significant species differences in physiology, immune systems, and metabolic reactions to anti-cancer drugs often lead to discrepancies between animal model findings and human clinical outcomes [

1,

13,

14]. For example, some murine models may not effectively metastasize or fully report experimental characteristics, limiting their utility for studying the full metastatic cascade [

1,

15]. Compounding these issues, surveys indicate a strikingly low concordance rate—barely 9%—between animal model findings and clinical trial success, with the majority of drugs failing in clinical stages despite demonstrating safety and efficacy in animal studies [

16,

17]. Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), while offering some improvements, are expensive, time-consuming, and raise ethical concerns [

18,

19,

20]. The high failure rate of drugs in clinical trials, despite promising preclinical animal data, is a direct consequence of these fundamental biological and physiological disparities. This situation highlights a critical translational bottleneck, where preclinical efficacy does not reliably translate to clinical success, thereby emphasizing the urgent need for human-centric,

in vitro models that more faithfully replicate the human tumor microenvironment and systemic interactions.

1.3. The “3Rs” Principle and the Shift Towards Human-Relevant Models

The growing recognition of the limitations of conventional models, coupled with ethical considerations, has spurred a global shift towards the development and adoption of non-animal alternatives. This movement is underpinned by the ‘Three Rs’ principles—Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement—mandated by directives such as the European Commission’s Directive 2010/63/EU [

7,

21,

22,

23]. The goal of this directive is to phase out animal testing when scientifically valid non-animal alternatives become available [

7,

24]. The development of advanced non-animal models is driven by the imperative to more faithfully represent the characteristic heterogeneity of human breast cancer and to reduce the burden of animal use in research [

7,

25]. These innovative models aim to bridge the gap between simplistic 2D cell cultures and complex

in vivo animal models, offering a more relevant and predictive platform for preclinical research [

26]. The legislative push for the “3Rs” combined with the scientific recognition of animal model limitations creates a strong synergistic impetus for the rapid development and adoption of non-animal models. This transition is not merely an ethical consideration but also a strategic priority for improving scientific rigor and the efficiency of drug discovery, moving towards a more human-centric approach in preclinical research.

2. Three-Dimensional (3D) Cell Culture Models: Foundations for Complex Mimicry

2.1. Advantages of 3D Cell Cultures over 2D Monolayers

Three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models represent a significant advancement in breast cancer research, primarily because they effectively mimic the complex 3D architecture of primary tumors [

9,

27,

28]. Unlike traditional 2D monolayer cultures, 3D systems promote crucial cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions, which are fundamental to tumor biology [

9,

29,

30]. This architectural fidelity allows 3D models to better recapitulate key

in vivo tumor characteristics, including cellular heterogeneity, hypoxic regions, realistic growth kinetics, intricate signaling pathway activity, and more accurate gene expression patterns [

9,

31]. Indeed, gene expression profiles observed in 3D cultures are notably closer to clinical expression profiles than those from 2D cultures [

9,

32]. Furthermore, 3D cultures maintain the natural morphology and polarity of tumor cells, which are often distorted in 2D systems. They also generate physiological concentration gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolic waste, mirroring the conditions found in actual tumors

in vivo [

9]. The ability of 3D cultures to spontaneously form complex structures and gradients, mimicking

in vivo conditions, fundamentally alters cellular behavior, leading to more physiologically relevant drug responses compared to 2D models. This suggests that drug efficacy and resistance mechanisms observed in 3D models are more likely to translate to clinical outcomes due to the improved biological fidelity. For instance, 3D breast cancer cell cultures have shown decreased proliferative rates and reduced drug sensitivity compared to 2D cultures, and cisplatin resistance has been observed to develop predominantly in 3D cultures, seemingly due to interactions within the tumor microenvironment [

9].

2.2. Spheroids and Organotypic Cultures

Within the realm of 3D cell cultures, various model types offer increasing levels of complexity and physiological relevance.

Spheroids are among the simplest 3D

in vitro cancer models, comprising spherical aggregates of tumor cells that can either self-assemble or be forced to aggregate [

6,

8,

26]. These can be grown in suspension using methods such as low-adhesion plates, hanging drop techniques, or spinner flasks [

9,

33,

34]. Spheroids exceeding 500 µm in diameter often exhibit properties akin to

in vivo avascular tumors, including heterogeneous cell populations and pathophysiological gradients [

26]. Their dense structure forms a physical barrier that can limit drug transport, thereby increasing observed drug resistance and enhancing the reliability of drug screening results [

26]. Commonly used breast cancer cell lines like MDA-MB-231, 4T1, and MCF7 are frequently employed in spheroid formation [

1,

35].

Organotypic Cultures involve culturing cancer cell lines within a semi-solid extracellular matrix under defined conditions. These models effectively recapitulate

in vivo characteristics such as growth kinetics, cellular heterogeneity, and signaling pathway activity [

8,

9,

36,

37]. Their structure makes them particularly suitable for high-throughput screening (HTS) assays, offering advantages over 2D conditions [

9,

38].

A crucial advancement in 3D modeling is the development of Heterotypic Models. These models incorporate multiple cell types to more accurately recapitulate the intricate cell-cell interactions found within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

9,

39]. For example, breast cancer cells (such as MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and SK-BR-3) are co-cultured with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), normal fibroblasts, and immune components like Natural Killer (NK) cells [

10,

40]. The presence of CAFs, for instance, can induce alterations in tumor cell expression of molecules like MICA/B and PD-L1, and also promote tumor cell aggregation into spheroids [

10,

41,

42]. The evolution from simple homotypic spheroids to complex heterotypic 3D models, incorporating stromal and immune components, signifies a strategic shift towards modeling the dynamic interplay within the TME. This is crucial because interactions with immune and stromal cells in the TME are known to enable breast cancer cells to escape immune surveillance, ultimately leading to therapeutic resistance, recurrence, and metastasis [

10,

43]. Therefore, drug efficacy studies in these more complex models are expected to yield more clinically relevant insights into overcoming resistance and predicting metastatic potential.

Table 1.

Comparison of Non-Animal Breast Cancer Metastasis Models.

Table 1.

Comparison of Non-Animal Breast Cancer Metastasis Models.

| Model Type |

TME Mimicry |

Metastasis Modeling Capabilities |

Suitability for High-Throughput Screening |

Clinical Relevance/Predictive Power |

Key Advantages |

Key Limitations |

Ref. |

| 2D Monolayer |

Low |

Migration, Invasion (basic) |

High |

Low |

Simple, cost-effective, high-throughput |

Lacks 3D structure, TME, heterogeneity; aberrant gene expression; poor translational power |

4, 7 |

| Spheroids |

Moderate |

Migration, Invasion, Hypoxia |

Moderate-High |

Moderate |

3D architecture, cell-cell interactions, nutrient gradients, drug penetration barrier; relatively simple |

Lacks full TME complexity (e.g., vasculature, diverse stromal cells); inconsistent size |

6, 8 |

| Organotypic Cultures |

Moderate-High |

Migration, Invasion, ECM interactions |

High |

Moderate-High |

Recapitulates growth kinetics, heterogeneity, signaling; HTS suitable; closer to clinical gene expression |

Still lacks full TME complexity and dynamic perfusion |

8, 37 |

| Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) |

High (partial TME) |

Invasion, Drug Resistance |

Moderate (scalability improving) |

High |

Preserves genetic/histological/phenotypic features of original tumor; captures heterogeneity; personalized drug testing; biobank potential |

Incomplete TME (lacks full vasculature, immune cells); inconsistent size; long culture time; sampling limitations |

14, 46 |

| Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) Systems |

Compreh-ensive |

Intravasation, Circulation, Extravasation, Multi-organ spread |

Moderate-High (automation potential) |

High |

Precise control over TME; dynamic perfusion, fluid shear; models systemic metastasis and toxicity; personalized chips |

Complex fabrication; high cost; technical expertise required; sample collection can be difficult |

11, 75, 76 |

3. Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs): Personalized Preclinical Avatars

3.1. Characteristics and Fidelity to Original Tumors

Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) represent a significant leap forward in preclinical modeling, serving as personalized

in vitro avatars of human tumors. These 3D cultures are generated directly from surgically resected tissues or biopsies, and critically, they preserve the genetic, histological, and phenotypic features of the original tumor [

18,

44,

45]. This remarkable fidelity means that PDOs are structurally and functionally similar to

in vivo organs, retaining key biomarkers such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 status, which are vital for understanding disease progression and targeting therapies [

2,

14,

46].

A paramount advantage of PDOs is their ability to capture the inherent heterogeneity of cancer, including the coexistence of stem-like cancer cells and differentiated cancer cells, as well as variations in HER2 expression levels across cell populations [

18,

44]. This aspect is particularly critical for studying therapeutic resistance and tumor evolution, as the presence of multiple subclones within a tumor mass can lead to the ineffectiveness of therapeutic strategies [

47]. PDOs also possess self-organization and self-renewal properties, allowing them to be maintained for extended periods

in vitro [

18,

45]. The success rate of breast cancer organoid culture has notably reached up to 87.5%, indicating robust and reproducible experimental models for elucidating cellular interaction mechanisms and promoting the development of effective cancer therapies [

10]. The ability of PDOs to faithfully recapitulate the complex molecular, genetic, and architectural heterogeneity of patient tumors directly addresses a major limitation of conventional models. This fidelity implies that drug responses observed in PDOs are more likely to reflect the patient’s actual response, making them invaluable for personalized medicine and overcoming the challenges posed by intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity in drug resistance.

3.2. Applications in Drug Screening and Personalized Medicine

The unique characteristics of PDOs make them a reliable model for preclinical drug screening, facilitating the establishment of breast cancer organoid biobanks, advancing research into tumor development mechanisms, and aiding in the determination of cancer targets [

48]. These models enable high-throughput analysis of compounds and allow for the determination of precise drug effects based on individual genetic variations, thereby fostering the development of personalized and combination therapies [

14,

18,

46].

The successful establishment of biobanks containing “living” breast cancer organoid samples is a critical development. These biobanks permit the long-term preservation of patient samples, which is crucial for researchers and helps reduce ethical controversies associated with fresh tissue procurement [

49]. Once fully characterized genetically and epigenetically, these organoids can be utilized for large-scale drug screening to identify compounds targeting specific breast cancer features, offering new hope for patients [

18,

50]. The establishment of patient-derived organoid biobanks represents a critical infrastructure development, enabling large-scale, systematic drug screening and the study of rare cancer subtypes [

2]. This moves beyond individual patient testing to a population-level resource that can accelerate drug discovery and validate targets across a diverse range of breast cancer phenotypes, ultimately fostering more targeted and effective therapeutic development.

3.3. Clinical Correlation and Predictive Power

A compelling aspect of PDOs is their demonstrated ability to predict clinical outcomes. Studies have shown that PDOs can be extensively used to predict chemotherapy responses, exhibiting high concordance rates between organoid reactions and patient clinical responses [

2]. One notable study reported a 100% concordance (18 out of 18 cases) between a PDO-based “zAvatar-test” and the corresponding patient’s clinical response to treatment [

51,

52,

53]. This strong correlation extends to predicting patient-specific sensitivity to personalized treatments, offering valuable insights into expected drug reactions and the identification of drug-resistant populations within tumors [

54,

55].

The clinical relevance of PDOs is further underscored by ongoing prospective clinical trials. For instance, ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT06468124 is actively assessing the capacity of PDOs derived from brain or extra-cranial metastases to predict patient treatment response, radio-sensitivity, and chemo-sensitivity, correlating these

in vitro findings with actual survival outcomes [

56]. The demonstrated high concordance between PDO drug responses and patient clinical outcomes, coupled with ongoing prospective clinical trials, signifies a pivotal shift towards PDOs as validated

in vitro substitutes for

in vivo human responses. This suggests that PDOs are moving beyond a research tool to a clinically actionable platform, potentially reducing the need for extensive animal testing and accelerating personalized treatment recommendations for patients [

57,

58].

Table 2.

Clinical Predictive Value of Patient-Derived Organoids in Breast Cancer Chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Clinical Predictive Value of Patient-Derived Organoids in Breast Cancer Chemotherapy.

| Study/Source |

Type of Breast Cancer/Metastasis Studied |

Chemotherapeutic Drugs Tested |

Correlation/Concordance with Clinical Outcome |

Key Findings/Predictive Value |

Ref. |

Shu et al. (2022),

Pasch et al (2020) |

TNBC (Triple-Negative Breast Cancer) |

Chemotherapy (general) |

Consistency between patient responses and organoid reactions |

PDOs can predict chemotherapy responses; valuable for personalized medicine. |

51, 55 |

Campaner et al. (2020),

Khorsandi et al. (2024) |

Various BC subtypes |

Not specified (drug reactivity) |

Aggressiveness of primary tissue influences organoid culture success |

Highlights the importance of tissue quality for reliable PDO models. |

47, 50 |

Shu et al. (2022),

Luo et al (2021) |

HER2-positive, HER2-negative BC |

Epirubicin, Docetaxel, Carboplatin (combinations) |

100% concordance (18/18) between zAvatar-test and patient clinical response; organoid response data matched patient’s clinical results. |

PDOs are a robust platform for drug efficacy testing and resistance profiling; can predict prognosis of patients with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. |

51, 53 |

Vasiliadou et al. (2024),

Ryu et al. (2025) |

Breast cancer with brain and/or extra-cranial metastases |

Radiotherapy, systemic treatments (including immunotherapy) |

Prospective assessment to correlate PDO sensitivities (IC50, dose-response curves) with patient treatment outcome and survival. |

Aims to validate PDOs as predictive tools for personalized treatment recommendations and prognosis in metastatic settings. |

57, 58 |

| Onder et al. (2023) |

Metastatic Breast Cancer (from malignant ascites and pleural effusion) |

Various drugs (individual responses) |

Organoids recapitulated characteristics of metastatic samples and demonstrated in vivo-like drug responses. |

Metastatic organoids serve as an accurate model for investigating BC progression and therapy predictions, especially for rare metastatic biopsies. |

2 |

3.4. Limitations of PDOs

Despite their significant advantages, current PDO models face several limitations that impact their comprehensive utility. A notable challenge is the incomplete recapitulation of the full tumor microenvironment (TME). Present PDO models often lack a complete tumor matrix, functional blood vessels, and a full complement of immune cells, which can hinder their ability to comprehensively model

in vivo drug responses [

18,

48,

59]. This deficiency in TME components is a key reason why the full clinical translation of PDO models in cancer precision therapy remains challenging [

51,

59].

Furthermore, challenges exist in standardization and scalability. Inconsistent organoid sizes can impair high-throughput drug screening due to variable drug penetration and response [

60]. The relatively long culture periods, often exceeding three weeks, can limit the timely provision of diagnostic and treatment suggestions for patients, particularly in urgent clinical scenarios [

51]. Other practical challenges include optimizing complex culture conditions, limitations in the amount of tumor tissue obtainable from biopsies, uncertainty regarding optimal medium composition, and susceptibility to contamination [

18,

61]. While PDOs offer significant advantages, their current limitations, particularly the incomplete recapitulation of the full TME (e.g., vasculature, immune cells) and scalability issues, highlight the ongoing need for further technological refinement and integration with other advanced models. This suggests a future direction where PDOs may be combined with microfluidics or bioprinting to create even more comprehensive and clinically predictive systems.

4. Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) Systems: Dynamic Microphysiological Platforms

4.1. Microfluidics and Tumor Microenvironment (TME) Recreation

Organ-on-a-chip (OoC) technologies represent a new generation of physiological-like organ biomimetic systems built upon microfluidic chips. These platforms offer precise control over various physicochemical and biomechanical parameters, enabling the recreation of natural physiological conditions in an

in vitro setting [

62]. OoC systems provide a dynamic platform to simulate “cancer-on-a-chip,” effectively emulating the complex biological context of tumors [

56]. Crucially, OoC models can recreate essential

in vivo features, including cell-cell or cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions, tissue barriers, vascular perfusion, fluid shear forces, and spatiotemporal chemical/physical gradients [

62,

63,

64,

65].

These dynamic elements are vital for maintaining tissue-specific functions and accurately mimicking the TME. The dynamic control offered by microfluidics in OoC systems, particularly the ability to mimic fluid flow and mechanical cues, represents a significant advancement beyond static 3D models. This dynamic environment is critical for accurately modeling drug pharmacokinetics, nutrient delivery, waste removal, and cell migration in a way that more closely mirrors

in vivo conditions, leading to more realistic drug exposure and response profiles. The precise control over fluid flow, nutrient delivery, and waste removal in these systems directly addresses the limitations of non-perfusable 3D models, where drug pharmacokinetics cannot be properly recapitulated [

7].

Simultaneously, microfluidics offers a disruptive platform for the isolation and analysis of extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are the prime messengers mediating intercellular communications in the TME. Owing to its inherent advantages, microfluidics promotes the development of new molecular and cellular sensing systems with: (a) improved sensitivity and specificity. The high surface-to-volume ratio enables efficient capture of low-abundance EV biomarkers [

66], (b) enhanced spatial and temporal resolution which allows for dynamic observation and kinetic analysis of EV interactions, and (c) high throughput in which miniaturization facilitates automation and rapid sample processing [

67]. The integration of these platforms is powerful microfluidic OoC models can generate physiologically relevant EVs, and the same microfluidic technology can then be used to isolate and analyze those EVs with high precision, providing a comprehensive system for studying TME-mediated communication and EV function in a dynamic

in vitro context.

4.2. Modeling Metastasis Stages

OoC technology is particularly adept at modeling the complex, multi-step process of cancer metastasis. Breast cancer-on-chip (BCoC), breast cancer liquid biopsy-on-chip (BCLBoC), and breast cancer metastasis-on-chip (BCMoC) models have successfully recapitulated and reproduced

in vitro the principal mechanisms and events involved in breast cancer cell communication and dissemination [

68,

69]. These tumor-on-chip models can mimic the main mechanisms of tumor development and metastasis, including cellular proliferation, bidirectional interactions between tumor cells and the ECM within the TME, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasion, migration, intravasation (entry into blood/lymph vessels), survival in circulation, extravasation (exit from vessels), and the construction of distant metastatic niches [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72].

A significant leap in this area is the development of multi-organ-on-chip systems. These platforms couple various tissue niches, linked by simulated vascular flow, to reproduce the dynamic spread of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) to multiple organs [

68,

73]. This confirms their immense potential for investigating systemic, multi-organ metastasis. Examples include lymph vessel-tumor tissue-blood vessel chips (LTB) and lymph node-on-chip (LNoC) systems, which can model lymphatic metastasis and the complex immune and cancer cell interactions within lymph nodes [

68,

74]. The development of multi-organ-on-chip systems capable of simulating the entire metastatic cascade (from intravasation to distant colonization) represents a significant leap towards understanding systemic disease progression and drug effects. This integrated approach allows for the study of inter-organ communication and systemic drug toxicity, moving beyond single-organ tumor responses to a more holistic representation of cancer as a systemic disease [

11,

75,

76].

4.3. Drug Efficacy and Toxicity Testing

Tumor-on-chip platforms are increasingly utilized for studying the efficacy and toxicity of various therapeutic agents, including chemotherapeutic drugs, nanomedicines, and nutraceuticals [

68,

77,

78]. A key advantage of OoC models is their ability to assess not only how cancer responds to therapy but also how the therapy might affect adjacent or distant organs. This comprehensive evaluation can include assessing drug effects on cells collected directly from a patient, facilitating personalized drug testing [

79,

80,

81]. The technology enables the creation of personalized chips where different drugs can be tested in a high-throughput, automated manner using minimal patient tissue, optimizing the selection of effective treatments [

79,

80,

82,

83]. The capacity of OoC systems to evaluate both drug efficacy on tumors and potential non-organ-specific toxicity in a single, integrated platform addresses a critical gap in preclinical drug development. This dual capability allows for a more comprehensive risk-benefit assessment of novel chemotherapeutics earlier in the pipeline, potentially reducing late-stage drug failures due to unforeseen systemic side effects.

4.4. Predictive Accuracy and Personalized Drug Testing

OoC technology holds immense significance for advancing personalized treatment strategies and accelerating new drug development. Because the cells used in OoC platforms are directly derived from human tissues, these systems effectively avoid the species differences that plague animal models, allowing for a more accurate evaluation of drug toxicity and efficacy in humans [

62,

84]. They can simulate multiple organ-specific disease states

in vitro, providing a dynamic representation of how drugs behave in the body and their influence on various organs [

62].

Conventional preclinical animal models often fail to predict human responses due to fundamental physiological and immunological differences, with concordance rates between animal findings and clinical trials barely reaching 9% [

85,

86,

87] (

https://www.fda.gov/files/newsroom/published/roadmap_to_reducing_animal_testing_in_preclinical_safety_studies.pdf). OoC offers a compelling solution to these limitations, presenting a potential paradigm shift in preclinical testing [

88,

89]. The superior predictive accuracy of OoC systems, stemming from their human-centric design and ability to mimic complex physiological dynamics, positions them as a powerful tool to complement and potentially reduce reliance on animal models. This shift promises to significantly improve the success rate of drug candidates in clinical trials, thereby accelerating the availability of effective and safe chemotherapies for breast cancer patients.

5. Assessing Chemotherapeutic Effects and Metastatic Potential in Non-Animal Models

5.1. Key Readouts for Drug Efficacy

Evaluating the effects of chemotherapeutic drugs in non-animal models requires a range of precise readouts that capture various aspects of tumor response and metastatic potential.

Tumor Volume and Weight are primary outcomes measured in some studies, with significant reductions indicating drug efficacy [

1]. Beyond macroscopic changes, Cell Viability and Growth Inhibition are crucial indicators. These are often assessed through metabolic activity assays, such as the AlamarBlue assay, in 3D cultures. Studies have shown increased cell viability in perfused 3D cultures compared to static conditions, highlighting the importance of dynamic environments [

90]. Decreased tumor sphere viability and growth are direct measures of drug effectiveness [

26].

Monitoring Proliferation Markers like Ki67 and p21 positive cells provides a more granular understanding of reduced tumor growth and metastatic potential following drug treatment [

91,

92,

93]. The induction of Apoptosis and Senescence (irreversible cell cycle arrest) by chemotherapeutics like Doxorubicin is also a critical readout. While senescence can lead to therapy resistance, targeting and removing senescent cells with senolytics can improve chemotherapeutic efficacy and prevent metastasis [

9]. 3D cultures have demonstrated a superior ability to simulate trastuzumab-induced apoptosis and resistance mechanisms compared to 2D models.

Furthermore, assessing changes in Gene and Protein Expression provides molecular insights into drug mechanisms. This includes monitoring microRNAs (miRNAs), which are known to regulate processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance [

9]. Changes in the expression of specific molecules like MICA/B and PD-L1 by tumor cells in heterotypic 3D models also offer valuable information on immune modulation by the tumor microenvironment [

10]. The shift from simple viability readouts to a multi-faceted assessment including proliferation markers, senescence, and specific gene expression changes reflects a deeper understanding of drug mechanisms and resistance. This comprehensive evaluation in non-animal models allows for the identification of not just drug efficacy, but also the underlying cellular and molecular pathways of resistance and metastasis, guiding the development of more targeted and combination therapies.

5.2. Assays for Metastasis-Related Processes

To specifically study the effects of chemotherapeutic drugs on breast cancer metastasis, various in vitro assays are employed to dissect individual steps of the metastatic cascade.

Cell Migration Assays are fundamental. The Wound Closure Assay (or Scratch Assay) is a simple and widely used method where a scratch is generated on a confluent cell monolayer, and the speed of wound closure and cell migration is quantified over time [

68,

94]. This assay is useful for determining the migration ability of whole cell masses and observing individual cell morphological characteristics during migration [

95].

Transwell Migration and Invasion Assays (also known as Boyden Chamber assays) are utilized to analyze the ability of single cells to directionally respond to chemo-attractants and invade through a porous membrane, which is often coated with matrix proteins to simulate tissue barriers [

68,

96,

97]. Another method, the Cell Exclusion Zone Assay, involves seeding cells around a barrier that is subsequently removed, creating a void for cell movement that is then imaged over time [

98,

99].

Microfluidic Assays offer a more controlled and dynamic environment for studying cell motility. These devices, with their intricate microchannels, enable researchers to precisely control gradients of test agents and mimic physiological conditions, making them particularly useful for investigating invasion, migration, and extravasation [

68,

74,

100]. The array of

in vitro assays specifically designed to dissect individual steps of the metastatic cascade (adhesion, migration, invasion, intravasation, extravasation) highlights a sophisticated approach to studying metastasis [

97,

101,

102]. This modularity allows researchers to isolate and investigate specific molecular events and drug targets at each stage, providing a detailed understanding of how chemotherapeutics might inhibit or promote different aspects of metastatic progression, which is crucial for developing anti-metastatic therapies.

Table 3.

Key Assays for Studying Breast Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion

in vitro.

Table 3.

Key Assays for Studying Breast Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion

in vitro.

| Assay Type |

Principle/What it Measures |

Advantages for Drug Testing |

Limitations |

Ref. |

| Wound Closure/Scratch Assay |

Measures collective cell migration into a “wound” created in a confluent monolayer. |

Simple, cost-effective, allows observation of cell morphology during migration. Useful for high-throughput screening. |

Primarily measures 2D migration; does not account for complex TME interactions or invasion through matrix. |

94 |

| Transwell Migration/Invasion Assay (Boyden Chamber) |

Measures single cell migration towards a chemo-attractant through a porous membrane (invasion if membrane coated with ECM). |

Quantifies directional migration and invasion; allows for testing of various chemo-attractants and ECM components. |

Static environment; does not fully replicate complex in vivo TME or fluid dynamics. |

97 |

| Cell Exclusion Zone Assay |

Measures cell migration into a defined cell-free area created by removing a physical barrier. |

Simple, label-free, adaptable for HTS. |

Similar to scratch assay, primarily 2D migration; limited TME complexity. |

99 |

| Microfluidic Assays |

Cells cultured in microchannels with controlled fluid flow and gradients to study motility, invasion, and extravasation. |

Replicates dynamic physiological conditions (fluid shear, gradients); allows for precise control of microenvironment; can model complex metastatic steps. |

More complex fabrication and operation; higher cost; sample collection can be difficult. |

97, 101 |

6. Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of non-animal models for breast cancer research is continuously evolving, driven by the integration of cutting-edge technologies that promise to further enhance their physiological relevance and predictive power.

6.1. 3D Bioprinting

Novel developments in 3D bioprinting technology are enabling the precise recreation of bioengineered tumor organotypic structures that closely mimic human tissue and its microenvironment [

103,

104]. This technology allows for the precision fabrication of tumor models with multiple layers, incorporating different cell types and compatible biomaterials such as hydrogels and ECM proteins, to build highly specific configurations [

103,

105]. Patient-derived cancer cells, stromal cells, genetic material, and growth factors are utilized to create bioprinted cancer models, paving the way for the screening of new personalized therapies [

103,

106]. Researchers have successfully 3D bioprinted breast cancer tumors with multi-scale vascularization, demonstrating their responsiveness to both chemotherapy and cell-based immunotherapeutics [

107,

108]. This achievement lays a crucial foundation for studying human immune cell interactions with solid tumors and evaluating experimental therapies without the need for

in vivo animal experimentation [

79,

107,

108,

109]. The ability of 3D bioprinting to precisely fabricate vascularized, multi-cellular tumor models with patient-derived components represents a convergence of advanced engineering and biology. This technology addresses the critical limitation of lacking perfusable blood vessels in many 3D models, enabling more accurate studies of drug delivery, penetration, and the complex interplay between tumor, stroma, and immune cells in a highly controlled, human-relevant environment.

6.2. CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing

CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized cancer research, including studies on breast cancer and its aggressive subtype, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [

110,

111,

112]. This powerful tool allows scientists to develop more accurate disease models, discover previously unknown genes involved in cancer progression, and investigate the sensitivity of tumors to various drugs and immunotherapies [

110]. Specifically, CRISPR/Cas9-based strategies can target potentially altered resistance genes, transcription, and epigenetic regulation to inhibit tumor growth and development [

110]. Furthermore, CRISPR facilitates the study of tumor fitness and contributes to the development of more sensitive and earlier diagnostic methods [

111]. The integration of CRISPR/Cas9 with non-animal models provides an unprecedented level of precision in dissecting the genetic drivers of breast cancer metastasis and drug resistance. This capability allows targeted gene manipulation to validate specific therapeutic targets, understand resistance mechanisms at a fundamental level, and potentially develop gene-edited models that are highly predictive of patient responses to novel therapies.

6.3. Advanced Imaging Techniques

The application of advanced imaging techniques is transforming the assessment of non-animal cancer models.

In vivo, techniques like contrast-enhanced mammography , contrast-enhanced MRI, Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI), and PET/CT scans are routinely used to detect and characterize tumors and metastasis [

113,

114,

115,

116,

117]. In the context of 3D

in vitro models, AI-powered 3D imaging tools can automatically identify tumor tissue, determine tumor volume, and assess distances to nearby anatomical features [

118,

119,

120]. This automated analysis provides quantitative data that enhances the precision of model evaluation. Deep learning models, integrating voxel-level radiomics with CT images, have demonstrated high accuracy in predicting pathological response to neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy, even outperforming unaided expert assessment [

121]. Moreover, platforms like Incucyte enable real-time monitoring of organoid dynamics, including growth, apoptosis, and morphological changes in response to treatment [

122]. The application of advanced imaging and AI to non-animal models enables non-invasive, real-time, and quantitative assessment of drug responses and metastatic processes within complex 3D structures. This capability provides dynamic data on tumor evolution and drug penetration that was previously difficult to obtain, significantly enhancing the analytical power and predictive capacity of these

in vitro systems.

6.4. Integration of AI and Machine Learning

The synergistic integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with non-animal models is revolutionizing pre-clinical drug discovery. AI and ML models enhance organoid platforms by predicting drug responses and optimizing high-throughput screening, thereby accelerating the identification of promising drug candidates [

51]. They can be integrated with CRISPR/Cas9 strategies to improve the effectiveness of TNBC therapy [

110]. AI-powered tools are capable of analyzing complex 3D images of breast cancer subtypes, revealing unique vascular patterns and providing deeper insights into tumor characteristics [

123]. Furthermore, deep learning models, such as 3D-ResNet and Vision Transformer, can predict pathological response to neoadjuvant therapy with high accuracy, surpassing the performance of unaided expert assessment in some cases [

121]. The synergistic integration of AI and machine learning with non-animal models is transforming preclinical drug discovery from a labor-intensive, empirical process into a data-driven, predictive science. AI’s capacity for high-throughput data analysis, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling accelerates the identification of effective drug candidates and personalized treatment strategies, significantly shortening drug development timelines and improving success rates.

6.5. Consortia and Collaborative Efforts

The increasing formation of consortia and collaborative networks underscores the recognition that the complexity of breast cancer and the development of advanced non-animal models necessitate shared expertise, resources, and standardized protocols. Consortia, such as the NCI Cohort Consortium and the Breast Cancer Family Registry (B-CFR), foster communication, promote collaborative research projects, and address scientific questions that are beyond the scope of individual studies [

124,

125,

126]. While the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium initially focused on animal models, the underlying principle of collective effort applies equally to non-animal model development [

127,

128]. Initiatives like the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) have undertaken extensive reviews, cataloging over 900 non-animal models for breast cancer research to improve their accessibility to the scientific community [

129] (

https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC122309). Collaborative efforts are particularly crucial for addressing challenges related to standardization and scalability in organoid culture, ensuring that these promising technologies can be widely adopted and translated into clinical practice [

60]. The increasing formation of consortia and collaborative networks in non-animal model research signifies a recognition that the complexity of breast cancer and the development of advanced models require shared expertise, resources, and standardized protocols. This collaborative ecosystem is essential for overcoming individual lab limitations, accelerating validation, and ensuring the widespread adoption and clinical translation of these promising technologies.

7. Conclusion: The Evolving Landscape of Non-Animal Models

Significant progress has been made in developing non-animal models for studying the effects of chemotherapeutic drugs on breast cancer metastasis. These advanced models are effectively overcoming the inherent limitations of traditional 2D cell cultures and animal models, which often fail to accurately replicate the complex human tumor microenvironment and predict clinical outcomes.

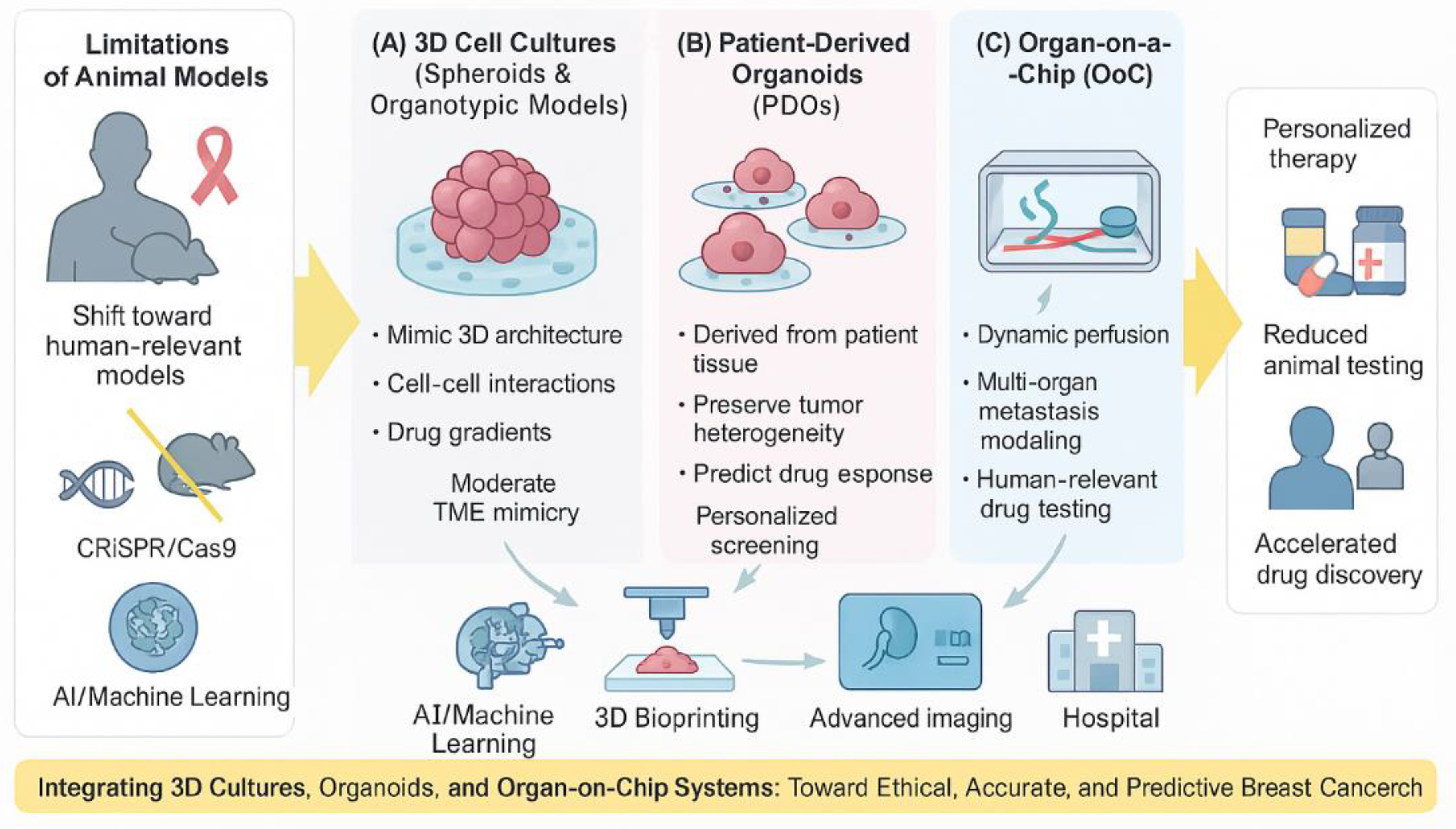

Figure 1.

The schematic illustrates the progressive transition from traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures to advanced human-relevant models, including three-dimensional (3D) spheroids, patient-derived organoids (PDOs), and organ-on-a-chip (OoC) systems. Each model demonstrates increasing levels of structural complexity, tumor microenvironment (TME) mimicry, and physiological relevance. Arrows indicate the evolution toward greater predictive power and translational accuracy. These models collectively aim to replace or reduce the need for animal testing while improving the reliability of preclinical drug screening and personalized treatment prediction.

Figure 1.

The schematic illustrates the progressive transition from traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures to advanced human-relevant models, including three-dimensional (3D) spheroids, patient-derived organoids (PDOs), and organ-on-a-chip (OoC) systems. Each model demonstrates increasing levels of structural complexity, tumor microenvironment (TME) mimicry, and physiological relevance. Arrows indicate the evolution toward greater predictive power and translational accuracy. These models collectively aim to replace or reduce the need for animal testing while improving the reliability of preclinical drug screening and personalized treatment prediction.

Three-dimensional cell cultures, particularly patient-derived organoids (PDOs) and organ-on-a-chip (OoC) systems, stand out for their ability to faithfully mimic human physiology, tumor heterogeneity, and the intricate tumor microenvironment. PDOs offer unparalleled fidelity to the original patient tumor, preserving its genetic and histological characteristics, and are proving invaluable for personalized drug screening and identifying drug resistance mechanisms. Their demonstrated high concordance with patient clinical outcomes positions them as powerful tools for guiding individualized treatment strategies. OoC systems, with their microfluidic capabilities, provide dynamic control over the cellular environment, enabling the simulation of complex metastatic processes, including intravasation, circulation, and extravasation, as well as the assessment of systemic drug efficacy and toxicity. This human-centric design of OoC platforms is poised to significantly improve the predictive accuracy of preclinical drug testing, addressing the low translational success rates observed with animal models. Figure. 1 summarizes non–human–relevant models used to study the chemotherapeutic effects and metastasis in breast cancer.

The future of breast cancer drug discovery is further shaped by the continuous integration of emerging technologies. 3D bioprinting offers the ability to fabricate vascularized, multi-cellular tumor models with unprecedented precision, enhancing the study of drug delivery and immune interactions. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing provides a powerful means to dissect the genetic drivers of metastasis and resistance, facilitating the identification of novel therapeutic targets. Advanced imaging techniques, coupled with the analytical power of artificial intelligence and machine learning, enable non-invasive, real-time, and quantitative assessment of drug responses and metastatic processes within these complex 3D structures. Finally, the growing emphasis on collaborative consortia ensures that shared expertise, resources, and standardized protocols accelerate the validation and widespread adoption of these innovative models. This concerted effort promises to revolutionize personalized medicine, lead to the development of more effective and safer chemotherapies, and ultimately reduce the reliance on animal testing, thereby improving the lives of breast cancer patients worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.N. Writing and Editing: S.N., H.H.N., H.A. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Florida Department of Health (23K05-JEK) to S.N. Figure 1 was generated using artificial intelligence (AI). We apologize to any colleagues whose work could not be cited directly and is instead referenced in the cited review articles.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

AI = Artificial intelligence

BCMoC = Breast cancer metastasis-on-chip

BCoC = Breast cancer-on-chip

BCLBoC = Breast cancer liquid biopsy-on-chip

CAF = Cancer-associated fibroblast

Cas9 = CRISPR-associated protein 9

CRISPR = Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats

CTC = Circulating tumor cell

ECM = Extracellular matrix

EMT = Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

ER = Estrogen receptor

EV = Extracellular vesicles

HER2 = Epidermal growth factor receptor 2

HTS = High-throughput screening

LNoC = Lymph node-on-chip

LTB = Lymph vessel-tumor tissue-blood vessel chips

MBC = Metastatic breast cancer

MDA-MB = MD Anderson-Metastatic Breast

NK = Natural Killer

OoC = Organ-on-a-chip

PDO = Patient-derived organoid

PDX = Patient-derived xenograft

PR = Progesterone receptor

TME = Tumor microenvironment

References

- Mirzaei Y, Huffel M, McCann S, Bannach-Brown A, Tolba RH, Steitz J. Animal models in preclinical metastatic breast cancer immunotherapy research: A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy outcomes. PLoS One. 2025;20(5):e0322876. Epub 20250507. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onder CE, Ziegler TJ, Becker R, Brucker SY, Hartkopf AD, Engler T, et al. Advancing Cancer Therapy Predictions with Patient-Derived Organoid Models of Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(14). Epub 20230713. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo L, Kong D, Liu J, Zhan L, Luo L, Zheng W, et al. Breast cancer heterogeneity and its implication in personalized precision therapy. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2023;12(1):3. Epub 20230109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim C, Bang JH, Kim YE, Lee SH, Kang JY. On-chip anticancer drug test of regular tumor spheroids formed in microwells by a distributive microchannel network. Lab Chip. 2012;12(20):4135-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gote V, Nookala AR, Bolla PK, Pal D. Drug Resistance in Metastatic Breast Cancer: Tumor Targeted Nanomedicine to the Rescue. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9). Epub 20210428. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunti S, Hoke ATK, Vu KP, London NR, Jr. Organoid and Spheroid Tumor Models: Techniques and Applications. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(4). Epub 20210219. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamouline A, Bersini S, Moretti M. In vitro models of breast cancer bone metastasis: analyzing drug resistance through the lens of the microenvironment. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1135401. Epub 20230411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangani S, Kremmydas S, Karamanos NK. Mimicking the Complexity of Solid Tumors: How Spheroids Could Advance Cancer Preclinical Transformative Approaches. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(7). Epub 20250330. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas-Vera YM, Valdes J, Perez-Navarro Y, Mandujano-Lazaro G, Marchat LA, Ramos-Payan R, et al. Three-Dimensional 3D Culture Models in Gynecological and Breast Cancer Research. Front Oncol. 2022;12:826113. Epub 20220526. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonteva A, Abdurakhmanova M, Bogachek M, Belovezhets T, Yurina A, Troitskaya O, et al. The Activity of Human NK Cells Towards 3D Heterotypic Cellular Tumor Model of Breast Cancer. Cells. 2025;14(14). Epub 20250708. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talmadge JE, Singh RK, Fidler IJ, Raz A. Murine models to evaluate novel and conventional therapeutic strategies for cancer. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(3):793-804. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Z, Zheng W, Wang H, Cheng Y, Fang Y, Wu F, et al. Application of Animal Models in Cancer Research: Recent Progress and Future Prospects. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:2455-75. Epub 20210315. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong M, Maina T. Of mice and humans: are they the same?--Implications in cancer translational research. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(4):501-4. Epub 20100317. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caloni F, Cazzaniga A, Gutleb AC, Hartung T, Kandarova H, Ranaldi G, et al. Non-animal models: Complexity for interactions...Connecting science. ALTEX. 2024;41(4):666-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena M, Christofori G. Rebuilding cancer metastasis in the mouse. Mol Oncol. 2013;7(2):283-96. Epub 20130220. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Norman, GA. Limitations of Animal Studies for Predicting Toxicity in Clinical Trials: Is it Time to Rethink Our Current Approach? JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2019;4(7):845-54. Epub 20191125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun D, Gao W, Hu H, Zhou S. Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(7):3049-62. Epub 20220211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi Y, Guan Z, Cai G, Nie Y, Zhang C, Luo W, et al. Patient-derived organoids: a promising tool for breast cancer research. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1350935. Epub 20240126. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompili L, Porru M, Caruso C, Biroccio A, Leonetti C. Patient-derived xenografts: a relevant preclinical model for drug development. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35(1):189. Epub 20161205. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui K, Yagishita S, Hamada A. Need for Ethical Governance on the Implementation and Use of Patient-derived Xenograft (PDX) Models for Anti-cancer Drug Discovery and Development: Ethical Considerations and Policy Proposal. JMA J. 2024;7(4):605-9. Epub 20240809. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott MJ, Lidster K. Improving quality of science through better animal welfare: the NC3Rs strategy. Lab Anim (NY). 2017;46(4):152-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham ML, Prescott MJ. The multifactorial role of the 3Rs in shifting the harm-benefit analysis in animal models of disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;759:19-29. Epub 20150328. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm H, Biller-Andorno N, Buch T, Dahlhoff M, Davies G, Cederroth CR, et al. Advancing the 3Rs: innovation, implementation, ethics and society. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10:1185706. Epub 20230615. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall LJ, Constantino H, Seidle T. Phase-In to Phase-Out-Targeted, Inclusive Strategies Are Needed to Enable Full Replacement of Animal Use in the European Union. Animals (Basel). 2022;12(7). Epub 20220329. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora T, Mehta AK, Joshi V, Mehta KD, Rathor N, Mediratta PK, et al. Substitute of Animals in Drug Research: An Approach Towards Fulfillment of 4R’s. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2011;73(1):1-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosca EM, Ronchi D, Facciolo D, Magni P. Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement of Animal Experiments in Anticancer Drug Development: The Contribution of 3D In Vitro Cancer Models in the Drug Efficacy Assessment. Biomedicines. 2023;11(4). Epub 20230330. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuwatfa WH, Pitt WG, Husseini GA. Scaffold-based 3D cell culture models in cancer research. J Biomed Sci. 2024;31(1):7. Epub 20240114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poornima K, Francis AP, Hoda M, Eladl MA, Subramanian S, Veeraraghavan VP, et al. Implications of Three-Dimensional Cell Culture in Cancer Therapeutic Research. Front Oncol. 2022;12:891673. Epub 20220512. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapalczynska M, Kolenda T, Przybyla W, Zajaczkowska M, Teresiak A, Filas V, et al. 2D and 3D cell cultures - a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Arch Med Sci. 2018;14(4):910-9. Epub 20161118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakopoulou K, Koutsakis C, Piperigkou Z, Karamanos NK. Recreating the extracellular matrix: novel 3D cell culture platforms in cancer research. FEBS J. 2023;290(22):5238-47. Epub 20230327. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa MAG, Xavier CPR, Pereira RF, Petrikaite V, Vasconcelos MH. 3D Cell Culture Models as Recapitulators of the Tumor Microenvironment for the Screening of Anti-Cancer Drugs. Cancers (Basel). 2021;14(1). Epub 20211231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschhaeuser F, Menne H, Dittfeld C, West J, Mueller-Klieser W, Kunz-Schughart LA. Multicellular tumor spheroids: an underestimated tool is catching up again. J Biotechnol. 2010;148(1):3-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foty, R. A simple hanging drop cell culture protocol for generation of 3D spheroids. J Vis Exp. 2011;(51). Epub 20110506. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang A, Madden LA, Paunov VN. Advanced biomedical applications based on emerging 3D cell culturing platforms. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(46):10487-501. Epub 20201102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang R, Lv Q, Meng W, Tan Q, Zhang S, Mo X, et al. Comparison of mammosphere formation from breast cancer cell lines and primary breast tumors. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(6):829-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues J, Heinrich MA, Teixeira LM, Prakash J. 3D In Vitro Model (R)evolution: Unveiling Tumor-Stroma Interactions. Trends Cancer. 2021;7(3):249-64. Epub 20201118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira LP, Gaspar VM, Monteiro MV, Freitas B, Silva NJO, Mano JF. Screening of dual chemo-photothermal cellular nanotherapies in organotypic breast cancer 3D spheroids. J Control Release. 2021;331:85-102. Epub 20210101. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny HA, Lal-Nag M, White EA, Shen M, Chiang CY, Mitra AK, et al. Erratum: Quantitative high throughput screening using a primary human three-dimensional organotypic culture predicts in vivo efficacy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10649. Epub 20160203. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakhshiteh F, Bagheri Z, Soleimani M, Ahvaraki A, Pournemat P, Alavi SE, et al. Heterotypic tumor spheroids: a platform for nanomedicine evaluation. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023;21(1):249. Epub 20230802. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghimi N, Hosseini SA, Dalan AB, Mohammadrezaei D, Goldman A, Kohandel M. Controlled tumor heterogeneity in a co-culture system by 3D bio-printed tumor-on-chip model. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):13648. Epub 20230822. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park K, Veena MS, Shin DS. Key Players of the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:830208. Epub 20220308. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo NA, Sanchez-Salas R, Peske JD, Vano Y, Becht E, Petitprez F, et al. The clinical role of the TME in solid cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;120(1):45-53. Epub 20181109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzapour MH, Heidari-Foroozan M, Razi S, Rezaei N. The pro-tumorigenic responses in metastatic niches: an immunological perspective. Clin Transl Oncol. 2023;25(2):333-44. Epub 20220922. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong L, Cui W, Zhang B, Fonseca P, Zhao Q, Zhang P, et al. Patient-derived organoids in precision cancer medicine. Med. 2024;5(11):1351-77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorel L, Perreard M, Florent R, Divoux J, Coffy S, Vincent A, et al. Patient-derived tumor organoids: a new avenue for preclinical research and precision medicine in oncology. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56(7):1531-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia S, Kramer M, Russo S, Naik P, Arun G, Brophy K, et al. Patient-Derived Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Organoids Provide Robust Model Systems That Recapitulate Tumor Intrinsic Characteristics. Cancer Res. 2022;82(7):1174-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campaner E, Zannini A, Santorsola M, Bonazza D, Bottin C, Cancila V, et al. Breast Cancer Organoids Model Patient-Specific Response to Drug Treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12). Epub 20201221. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varinelli L, Illescas O, Lorenc EJ, Battistessa D, Di Bella M, Zanutto S, et al. Organoids technology in cancer research: from basic applications to advanced ex vivo models. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025;13:1569337. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang S, Mei Z, Wan A, Zhao M, Qi X. Application and prospect of organoid technology in breast cancer. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1413858. Epub 20240826. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorsandi D, Yang JW, Foster S, Khosravi S, Hosseinzadeh Kouchehbaghi N, Zarei F, et al. Patient-Derived Organoids as Therapy Screening Platforms in Cancer Patients. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13(21):e2302331. Epub 20240301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu D, Shen M, Li K, Han X, Li H, Tan Z, et al. Organoids from patient biopsy samples can predict the response of BC patients to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):2581-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes RV, Ribeiro JM, Gouveia H, Rebelo de Almeida C, Castillo-Martin M, Brito MJ, et al. Zebrafish Avatar testing preclinical study predicts chemotherapy response in breast cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2025;9(1):94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo Z, Zhou X, Mandal K, He N, Wennerberg W, Qu M, et al. Reconstructing the tumor architecture into organoids. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;176:113839. Epub 20210619. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa B, Estrada MF, Gomes A, Fernandez LM, Azevedo JM, Povoa V, et al. Zebrafish Avatar-test forecasts clinical response to chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4771. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasch CA, Favreau PF, Yueh AE, Babiarz CP, Gillette AA, Sharick JT, et al. Patient-Derived Cancer Organoid Cultures to Predict Sensitivity to Chemotherapy and Radiation. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(17):5376-87. Epub 20190607. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boix-Montesinos P, Soriano-Teruel PM, Arminan A, Orzaez M, Vicent MJ. The past, present, and future of breast cancer models for nanomedicine development. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;173:306-30. Epub 20210331. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliadou I, Cattaneo C, Chan PYK, Henley-Smith R, Gregson-Williams H, Collins L, et al. Correlation of the treatment sensitivity of patient-derived organoids with treatment outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer (SOTO): protocol for a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2024;14(10):e084176. Epub 20241010. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu S, Kim HS, Lee S, Yoon SH, Baek M, Park AY, et al. Anti-cancer drug sensitivity testing and preclinical evaluation of the anti-cancer potential of WEE1 inhibitor in triple-negative breast cancer patient-derived organoids and xenograft models. Breast Cancer Res. 2025;27(1):113. Epub 20250623. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayibov E, Sychra T, Spalenkova A, Soucek P, Oliverius M. The use of patient-derived xenografts and patient-derived organoids in the search for new therapeutic regimens for pancreatic carcinoma. A review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2025;182:117750. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arani RM, Yousefi N, Hamidieh AA, Gholizadeh F, Sisakht MM. Tumor Organoid as a Drug Screening Platform for Cancer Research. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;19(9):1210-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han SJ, Kwon S, Kim KS. Challenges of applying multicellular tumor spheroids in preclinical phase. Cancer cell international. 2021;21(1):152. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Su Q, Zhang X, Yang W, Ning J, Jia K, et al. Recent Advances of Organ-on-a-Chip in Cancer Modeling Research. Biosensors (Basel). 2022;12(11). Epub 20221118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filiz Y, Esposito A, De Maria C, Vozzi G, Yesil-Celiktas O. A comprehensive review on organ-on-chips as powerful preclinical models to study tissue barriers. Prog Biomed Eng (Bristol). 2024;6(4). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwokoye PN, Abilez OJ. Bioengineering methods for vascularizing organoids. Cell Rep Methods. 2024;4(6):100779. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhang Doost N, Srivastava SK. A Comprehensive Review of Organ-on-a-Chip Technology and Its Applications. Biosensors (Basel). 2024;14(5). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan H, Li Y, Cheng S, Zeng Y. Advances in Analytical Technologies for Extracellular Vesicles. Anal Chem. 2021;93(11):4739-74. Epub 20210226. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng S, Li Y, Yan H, Wen Y, Zhou X, Friedman L, et al. Advances in microfluidic extracellular vesicle analysis for cancer diagnostics. Lab Chip. 2021;21(17):3219-43. Epub 20210805. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neagu AN, Whitham D, Bruno P, Versaci N, Biggers P, Darie CC. Tumor-on-chip platforms for breast cancer continuum concept modeling. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1436393. Epub 20241002. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang P, Wu X, Gardashova G, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Xu L, et al. Molecular and functional extracellular vesicle analysis using nanopatterned microchips monitors tumor progression and metastasis. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(547). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouybar M, de Winde CM, Wolf K, Friedl P, Mebius RE, den Toonder JMJ. Cancer-on-chip models for metastasis: importance of the tumor microenvironment. Trends Biotechnol. 2024;42(4):431-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleman J, Skardal A. A multi-site metastasis-on-a-chip microphysiological system for assessing metastatic preference of cancer cells. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2019;116(4):936-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han B, Qu C, Park K, Konieczny SF, Korc M. Recapitulation of complex transport and action of drugs at the tumor microenvironment using tumor-microenvironment-on-chip. Cancer letters. 2016;380(1):319-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghban R, Roshangar L, Jahanban-Esfahlan R, Seidi K, Ebrahimi-Kalan A, Jaymand M, et al. Tumor microenvironment complexity and therapeutic implications at a glance. Cell communication and signaling : CCS. 2020;18(1):59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta P, Rahman Z, Ten Dijke P, Boukany PE. Microfluidics meets 3D cancer cell migration. Trends Cancer. 2022;8(8):683-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sontheimer-Phelps A, Hassell BA, Ingber DE. Modelling cancer in microfluidic human organs-on-chips. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(2):65-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang M, Soon RH, Lim CT, Khoo BL, Han J. Microfluidic modelling of the tumor microenvironment for anti-cancer drug development. Lab Chip. 2019;19(3):369-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang YS, Zhang YN, Zhang W. Cancer-on-a-chip systems at the frontier of nanomedicine. Drug discovery today. 2017;22(9):1392-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian C, Zheng S, Liu X, Kamei KI. Tumor-on-a-chip model for advancement of anti-cancer nano drug delivery system. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):338. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson K, Zanivan S, Glasspool R, Coffelt SB, Zagnoni M. Microfluidic technologies for immunotherapy studies on solid tumours. Lab Chip. 2021;21(12):2306-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graney PL, Tavakol DN, Chramiec A, Ronaldson-Bouchard K, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Engineered models of tumor metastasis with immune cell contributions. iScience. 2021;24(3):102179. Epub 20210212. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu J, Ji L, Chen Y, Li H, Huang M, Dai Z, et al. Organoids and organs-on-chips: insights into predicting the efficacy of systemic treatment in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9(1):72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster B, Junkin M, Kashaf SS, Romero-Calvo I, Kirby K, Matthews J, et al. Automated microfluidic platform for dynamic and combinatorial drug screening of tumor organoids. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5271. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabatabaei Rezaei N, Kumar H, Liu H, Lee SS, Park SS, Kim K. Recent Advances in Organ-on-Chips Integrated with Bioprinting Technologies for Drug Screening. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12(20):e2203172. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low LA, Mummery C, Berridge BR, Austin CP, Tagle DA. Organs-on-chips: into the next decade. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2021;20(5):345-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Norman, GA. Limitations of Animal Studies for Predicting Toxicity in Clinical Trials: Part 2: Potential Alternatives to the Use of Animals in Preclinical Trials. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5(4):387-97. Epub 20200427. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins JT, George GC, Hess K, Marcelo-Lewis KL, Yuan Y, Borthakur G, et al. Pre-clinical animal models are poor predictors of human toxicities in phase 1 oncology clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(10):1496-501. Epub 20200901. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soufizadeh P, Mansouri V, Ahmadbeigi N. A review of animal models utilized in preclinical studies of approved gene therapy products: trends and insights. Lab Anim Res. 2024;40(1):17. Epub 20240422. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava SK, Foo GW, Aggarwal N, Chang MW. Organ-on-chip technology: Opportunities and challenges. Biotechnol Notes. 2024;5:8-12. Epub 20240105. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma C, Peng Y, Li H, Chen W. Organ-on-a-Chip: A New Paradigm for Drug Development. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2021;42(2):119-33. Epub 20201216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu P, Roberts S, Shoemaker JT, Vukasinovic J, Tomlinson DC, Speirs V. Validation of a 3D perfused cell culture platform as a tool for humanised preclinical drug testing in breast cancer using established cell lines and patient-derived tissues. PLoS One. 2023;18(3):e0283044. Epub 20230316. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uxa S, Castillo-Binder P, Kohler R, Stangner K, Muller GA, Engeland K. Ki-67 gene expression. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(12):3357-70. Epub 20210628. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey MG, Hynes SO, Kerin MJ, Miller N, Lowery AJ. Ki-67 as a Prognostic Biomarker in Invasive Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(17). Epub 20210903. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerushalmi R, Woods R, Ravdin PM, Hayes MM, Gelmon KA. Ki67 in breast cancer: prognostic and predictive potential. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):174-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchalova P, Bouchal P. Current methods for studying metastatic potential of tumor cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):394. Epub 20221209. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justus CR, Leffler N, Ruiz-Echevarria M, Yang LV. In vitro cell migration and invasion assays. J Vis Exp. 2014;(88). Epub 20140601. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justus CR, Marie MA, Sanderlin EJ, Yang LV. Transwell In Vitro Cell Migration and Invasion Assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2644:349-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang K, Liang L, Lim CT. Engineering confining microenvironment for studying cancer metastasis. iScience. 2021;24(2):102098. Epub 20210127. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulkower KI, Herber RL. Cell migration and invasion assays as tools for drug discovery. Pharmaceutics. 2011;3(1):107-24. Epub 20110311. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menyhart O, Harami-Papp H, Sukumar S, Schafer R, Magnani L, de Barrios O, et al. Guidelines for the selection of functional assays to evaluate the hallmarks of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1866(2):300-19. Epub 20161011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halldorsson S, Lucumi E, Gomez-Sjoberg R, Fleming RMT. Advantages and challenges of microfluidic cell culture in polydimethylsiloxane devices. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;63:218-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Tavakoli H, Ma L, Li X, Han L, Li X. Immunotherapy discovery on tumor organoid-on-a-chip platforms that recapitulate the tumor microenvironment. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;187:114365. Epub 20220603. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao Z, Yang Y, Zeng Y, He M. A microfluidic ExoSearch chip for multiplexed exosome detection towards blood-based ovarian cancer diagnosis. Lab Chip. 2016;16(3):489-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Jin P. Advances and Challenges in 3D Bioprinted Cancer Models: Opportunities for Personalized Medicine and Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel). 2025;17(7). Epub 20250331. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren Y, Yuan C, Liang Q, Ba Y, Xu H, Weng S, et al. 3D Bioprinting for Engineering Organoids and Organ-on-a-Chip: Developments and Applications. Med Res Rev. 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodi I, Di Lisa D, Pastorino L, Scaglione S, Fato MM. 3D Bioprinting as a Powerful Technique for Recreating the Tumor Microenvironment. Gels. 2023;9(6). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustine R, Kalva SN, Ahmad R, Zahid AA, Hasan S, Nayeem A, et al. 3D Bioprinted cancer models: Revolutionizing personalized cancer therapy. Translational oncology. 2021;14(4):101015. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey M, Kim MH, Dogan M, Nagamine M, Kozhaya L, Celik N, et al. Chemotherapeutics and CAR-T Cell-Based Immunotherapeutics Screening on a 3D Bioprinted Vascularized Breast Tumor Model. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32(52). Epub 20221003. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey M, Kim MH, Nagamine M, Karhan E, Kozhaya L, Dogan M, et al. Biofabrication of 3D breast cancer models for dissecting the cytotoxic response of human T cells expressing engineered MAIT cell receptors. Biofabrication. 2022;14(4). Epub 20220929. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abizanda-Campo S, Virumbrales-Munoz M, Humayun M, Marmol I, Beebe DJ, Ochoa I, et al. Microphysiological systems for solid tumor immunotherapy: opportunities and challenges. Microsyst Nanoeng. 2023;9:154. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari PK, Ko TH, Dubey R, Chouhan M, Tsai LW, Singh HN, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 as a therapeutic tool for triple negative breast cancer: from bench to clinics. Front Mol Biosci. 2023;10:1214489. Epub 20230704. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pont M, Marques M, Sorolla MA, Parisi E, Urdanibia I, Morales S, et al. Applications of CRISPR Technology to Breast Cancer and Triple Negative Breast Cancer Research. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(17). Epub 20230901. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra G, Qaisar S, Singh P. CRISPR-based therapeutic targeting of signaling pathways in breast cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta Molecular basis of disease. 2024;1870(1):166872. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fass, L. Imaging and cancer: a review. Mol Oncol. 2008;2(2):115-52. Epub 20080510. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir U, Mallia A, Stirling J, Joemon J, MacKewn J, Charles-Edwards G, et al. PET/MRI in Oncological Imaging: State of the Art. Diagnostics (Basel). 2015;5(3):333-57. Epub 20150721. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh DM, Blackledge M, Padhani AR, Takahara T, Kwee TC, Leach MO, et al. Whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI: tips, tricks, and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(2):252-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain S, Mubeen I, Ullah N, Shah S, Khan BA, Zahoor M, et al. Modern Diagnostic Imaging Technique Applications and Risk Factors in the Medical Field: A Review. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:5164970. Epub 20220606. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baniasadi A, Das JP, Prendergast CM, Beizavi Z, Ma HY, Jaber MY, et al. Imaging at the nexus: how state of the art imaging techniques can enhance our understanding of cancer and fibrosis. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):567. Epub 20240613. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari A, Mishra S, Kuo TR. Current AI technologies in cancer diagnostics and treatment. Mol Cancer. 2025;24(1):159. Epub 20250602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Zhou X, Fang Y, Xiong Z, Zhang T. AI-driven 3D bioprinting for regenerative medicine: From bench to bedside. Bioact Mater. 2025;45:201-30. Epub 20241123. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang YP, Zhang XY, Cheng YT, Li B, Teng XZ, Zhang J, et al. Artificial intelligence-driven radiomics study in cancer: the role of feature engineering and modeling. Mil Med Res. 2023;10(1):22. Epub 20230516. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng J, Yan Z, Wang R, Xiao H, Chen Z, Ge X, et al. NeoPred: dual-phase CT AI forecasts pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy in NSCLC. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13(5). Epub 20250531. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang X, Hu Y, Dai Z, Lou Q, Xu W, Chen L. Precision medicine research progress based on colorectal cancer organoids. Discov Oncol. 2025;16(1):1181. Epub 20250623. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang H, Zheng E, Zheng W, Huang C, Xi Y, Cheng Y, et al. OneTouch Automated Photoacoustic and Ultrasound Imaging of Breast in Standing Pose. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2025;PP. Epub 20250612. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgio MR, Ioannidis JP, Kaminski BM, Derycke E, Rogers S, Khoury MJ, et al. Collaborative cancer epidemiology in the 21st century: the model of cancer consortia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(12):2148-60. Epub 20130917. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy AE, Khoury MJ, Ioannidis JP, Brotzman M, Miller A, Lane C, et al. The Cancer Epidemiology Descriptive Cohort Database: A Tool to Support Population-Based Interdisciplinary Research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(10):1392-401. Epub 20160720. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swerdlow AJ, Harvey CE, Milne RL, Pottinger CA, Vachon CM, Wilkens LR, et al. The National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium: An International Pooling Collaboration of 58 Cohorts from 20 Countries. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(11):1307-19. Epub 20180717. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, C. Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium (MMHCC) from the NCI. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2(3-4):111. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searson, PC. The Cancer Moonshot, the role of in vitro models, model accuracy, and the need for validation. Nat Nanotechnol. 2023;18(10):1121-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribaldo L, Dura A. EURL ECVAM Literature Review Series on Advanced Non-Animal Models for Respiratory Diseases, Breast Cancer and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Animals (Basel). 2022;12(17). Epub 20220825. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).