Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Requests and Evolution of Medical Interventions

2.1. Features of Different Interventional Techniques

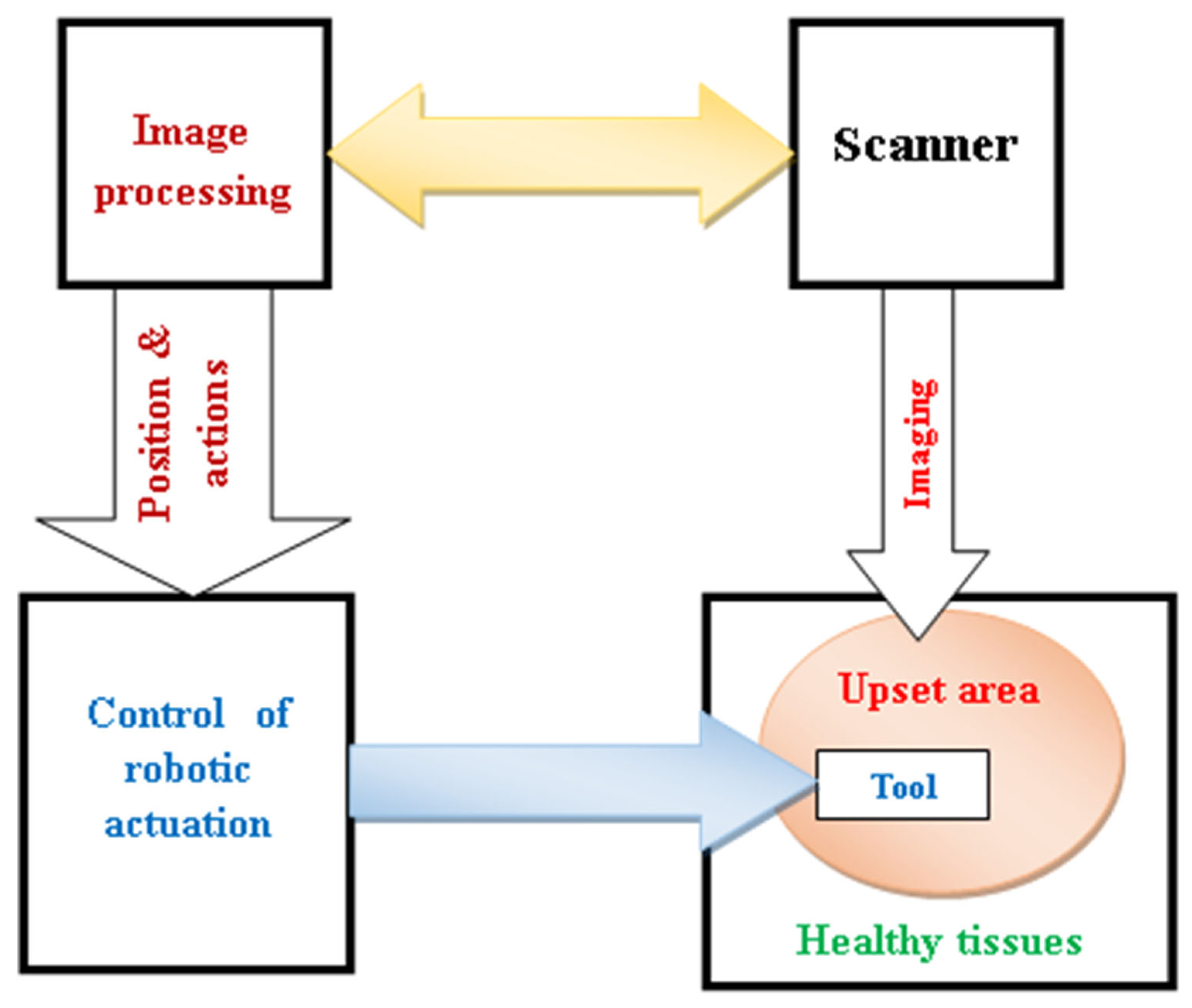

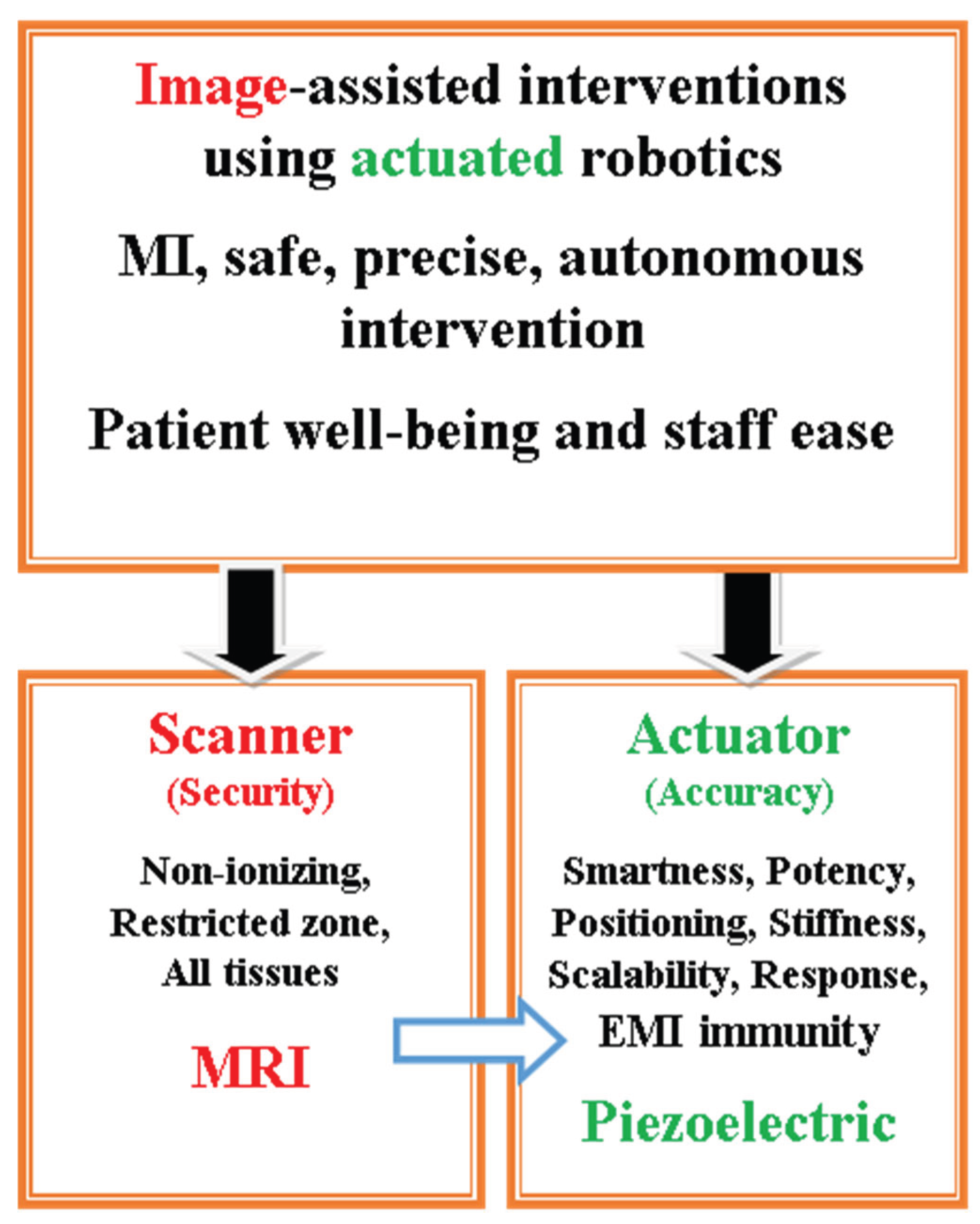

2.2. Accurate and Safe Image-Assisted Robotic Autonomous Interventions

3. Robotic Actuation Technologies

3.1. Positioning Actuated Robotic and Self-Moving Miniature Robotic Procedures

3.2. MRI-Assistance in Robotic Procedures

4. Monitoring of MRI-Assisted Robotic Procedures

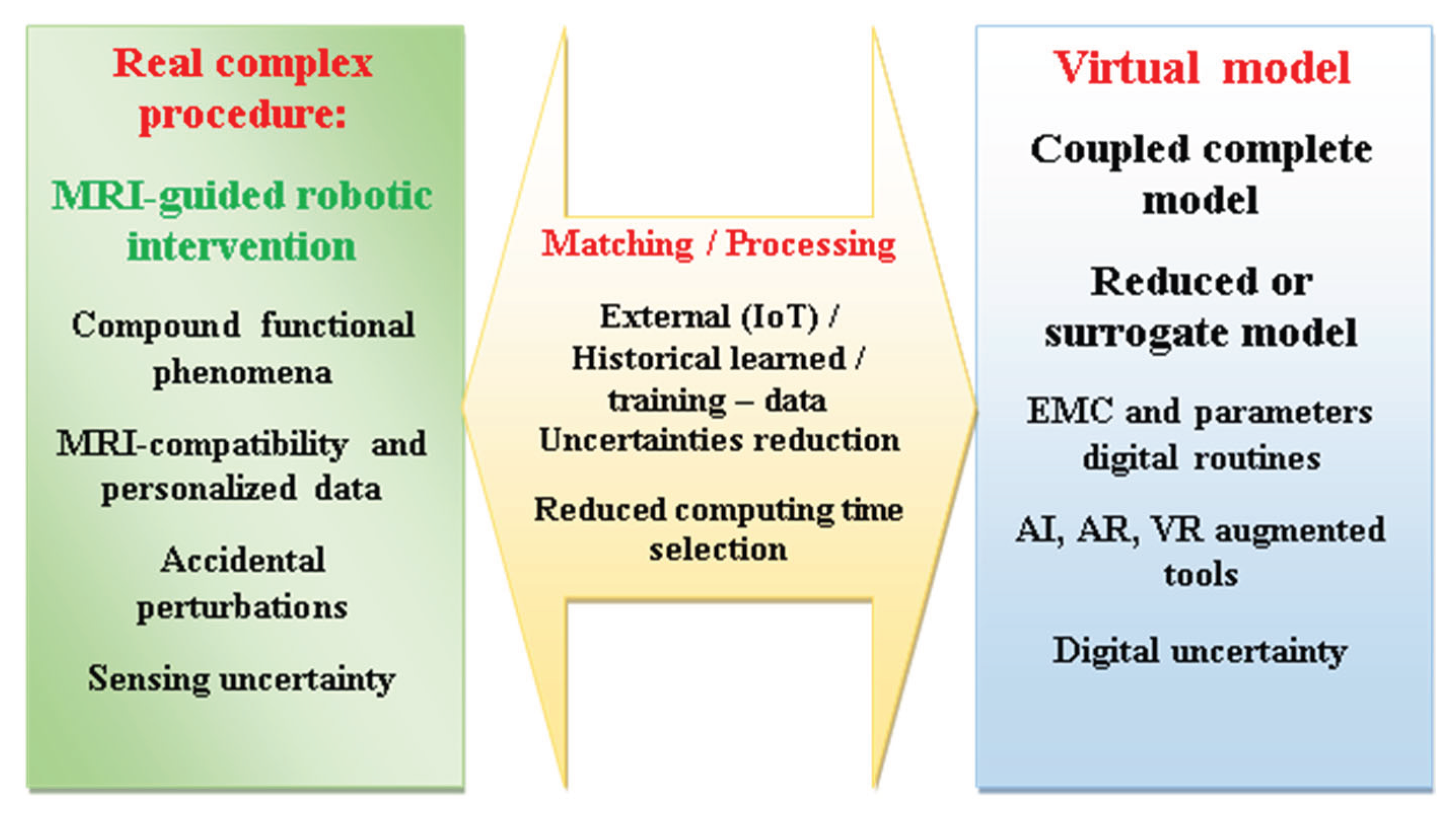

4.1. Digital Twin Supervision of MRI-Assisted Robotic Control

4.2. Digital Environment Augmented Tools

5. Wearable Detecting and Assistive Medical Devices

5.1. Sensing in Healthcare Wearable Tools

5.2. Assistive Wearable Devices

5.3. Multifunctional Activities and Flexible Wearable Instruments

5.4. Wearable EMC Digital Control

6. Discussion

6.1. Effects of Exposure to EMF

6.1.1. Biological Effects of EMF Exposure

6.1.2. Medical Devices Immunity to EMI

6.2. Device Compatibility and EMC Analysis

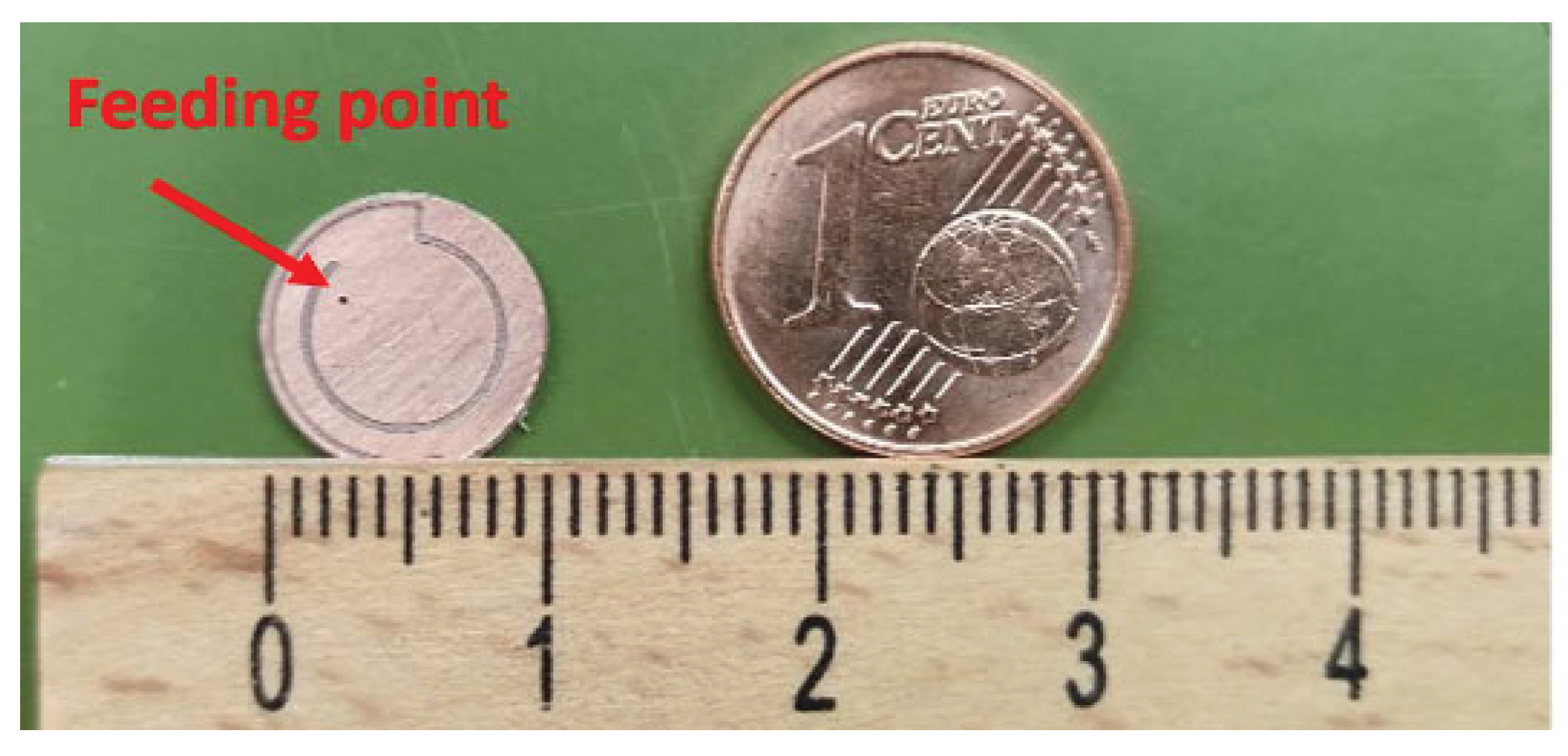

6.2.1. Example of EMC Analysis Using Experimental Means

6.2.2. Digital EMC Analysis in Medical Devices

6.3. Smart Protection of Medical Devices

6.4. Digital Augmented Tools and Personalized Committed Assignments

6.5. DT Interventional Complexity Management and Reduction of Complete Models

6.6. Future Perspectives

6.6.1. Living Tissues Dynamic Mechanical Representation

6.6.2. Compatibility of Smart Materials and Digital Tools

6.6.3. Smart Digital Wearable Technologies and Swing from Therapy to Preclusion

6.6.4. Smart Digital Monitoring of Medical Robotics Beyond Interventions

6.6.5. Future Perspectives Integrated in the Contribution Background

7. Conclusions

- Living tissues dynamic mechanical physical and digital representations

- Compatibility of smart materials and digital tools

- Smart digital wearable technologies and swing from therapy to preclusion

- Smart digital monitoring of medical robotics beyond interventions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hernigou, P.; Hosny, G.A.; Scarlat, M. Evolution of orthopaedic diseases through four thousand three hundred years: From ancient Egypt with virtual examinations of mummies to the twenty-first century. Int. Orthop. 2023, 48, 865–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Image-Guided Surgical and Pharmacotherapeutic Routines as Part of Diligent Medical Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Fan, S.; Qiao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Lin, B.; Li, Z.; Riegler, M.A.; Wong, M.Y.H.; Opheim, A.; Korostynska, O.; et al. Transforming Healthcare: Intelligent Wearable Sensors Empowered by Smart Materials and Artificial Intelligence. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2500412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Hernandez, U.; Metcalfe, B.; Assaf, T.; Jabban, L.; Male, J.; Zhang, D. Wearable Assistive Robotics: A Perspective on Current Challenges and Future Trends. Sensors 2021, 21, 6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, S.; Luo, R.; Liu, H. A novel real-time assistive hip-wearable exoskeleton robot based on motion prediction for lower extremity rehabilitation in subacute stroke: A single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol. 2025, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbottom, L.; Chen, A.; Mendonca, R.; Nilsen, D.M.; Ciocarlie, M.; Stein, J. Clinician perceptions of a novel wearable robotic hand orthosis for post-stroke hemiparesis. Disabil. Rehabilitation 2024, 47, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. From Open, Laparoscopic, or Computerized Surgical Interventions to the Prospects of Image-Guided Involvement. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukushkin, K.; Ryabov, Y.; Borovkov, A. Digital Twins: A Systematic Literature Review Based on Data Analysis and Topic Modeling. Data 2022, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giansanti, D.; Morelli, S. Exploring the Potential of Digital Twins in Cancer Treatment: A Narrative Review of Reviews. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, D.; Boldrini, L.; Dhont, J.; Fiorino, C.; Green, O.; Güngör, G.; Jornet, N.; Klüter, S.; Landry, G.; Mattiucci, G.C.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in magnetic Resonance guided Radiotherapy: Medical and physical considerations on state of art and future perspectives. Phys. Medica 2021, 85, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeken, T.; Lim, H.-P.D.; Cohen, E.I. The Role and Future of Artificial Intelligence in Robotic Image-Guided Interventions. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 27, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Lu, C.; Li, S.; Lu, L.; Zhang, D. Artificial Intelligence in Orthopedic Surgery: Current Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Medcomm 2025, 6, e70260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, S.; Iwase, H.; Yoneda, H.; Yokota, H.; Hirata, H.; Yamamoto, M. Insights and trends review: Use of extended reality (xR) in hand surgery. J. Hand Surg. 2025, 50, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angrisani, L.; D’arco, M.; De Benedetto, E.; Duraccio, L.; Regio, F.L.; Sansone, M.; Tedesco, A. Performance Measurement of Gesture-Based Human–Machine Interfaces Within eXtended Reality Head-Mounted Displays. Sensors 2025, 25, 2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Armas, J.; Roldán-Ruiz, A.; Flores-Cortes, M.; Harvie, D.S. Harnessing Extended Reality for Neurocognitive Training in Chronic Pain: State of the Art, Opportunities, and Future Directions. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeson, K.; May, C.T.X.; Abdullah, A.A.A.; Ramakrishna, S.; Vigneswari, S. Advantages and Prospective Implications of Smart Materials in Tissue Engineering: Piezoelectric, Shape Memory, and Hydrogels. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchetta, G.; Fiori, G.; Sciuto, S.A.; Scorza, A. Performance of Smart Materials-Based Instrumentation for Force Measurements in Biomedical Applications: A Methodological Review. Actuators 2023, 12, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giansanti, D. The Future of Healthcare Is Digital: Unlocking the Potential of Mobile Health and E-Health Solutions. Healthcare 2025, 13, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.C.; Wang, Z. Precision Medicine: Disease Subtyping and Tailored Treatment. Cancers 2023, 15, 3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B. The Promise of Explainable AI in Digital Health for Precision Medicine: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Special Issue: Healthcare Goes Digital: Mobile Health and Electronic Health Technology in the 21st Century. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/healthcare/special_issues/0P14J89UOQ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Razek, A. Biological and Medical Disturbances Due to Exposure to Fields Emitted by Electromagnetic Energy Devices—A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Assessment of a Functional Electromagnetic Compatibility Analysis of Near-Body Medical Devices Subject to Electromagnetic Field Perturbation. Electronics 2023, 12, 4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri, H. Design and Realization of a Piezoelectric Mobile for Cooperative Use. PhD Thesis, University of Paris XI, Paris, France, 2012. (In English). Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-01124059v1/file/2012PA112321.

- Tetteh, E.; Wang, T.; Kim, J.Y.; Smith, T.; Norasi, H.; Van Straaten, M.G.; Lal, G.; Chrouser, K.L.; Shao, J.M.; Hallbeck, M.S. Optimizing ergonomics during open, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted surgery: A review of surgical ergonomics literature and development of educational illustrations. Am. J. Surg. 2023, 235, 115551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkatout, I.; Mechler, U.; Mettler, L.; Pape, J.; Maass, N.; Biebl, M.; Gitas, G.; Laganà, A.S.; Freytag, D. The Development of Laparoscopy—A Historical Overview. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 799442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, E.L.; Polcz, V.E.; Hensley, S.E.; Sarosi, G.A.; Mohr, A.M.; Loftus, T.J.; Upchurch, G.R.; Sumfest, J.M.; Efron, P.A.; Dunleavy, K.; et al. A narrative review of ergonomic problems, principles, and potential solutions in surgical operations. Surgery 2023, 174, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, R. Laparoscopic Surgery—15 Years After Clinical Introduction. World J. Surg. 2006, 30, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, U.; Corcione, F.; Pignata, G.; Andreuccetti, J.; Dolce, P.; Boni, L.; Cassinotti, E.; Olmi, S.; Uccelli, M.; Gualtierotti, M.; et al. Impact of neoadjuvant therapy followed by laparoscopic radical gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection in Western population: A multi-institutional propensity score-matched study. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 124, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, N.; Anchora, L.P.; Teodorico, E.; Certelli, C.; Galati, G.; Carbone, V.; Gallotta, V.; Naldini, A.; Costantini, B.; Querleu, D.; et al. The role of diagnostic laparoscopy in locally advanced cervical cancer staging. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2024, 50, 108645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Salazar, M.J.; Caballero, D.; Sánchez-Margallo, J.A.; Sánchez-Margallo, F.M. Comparative Study of Ergonomics in Conventional and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Surgery. Sensors 2024, 24, 3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-Y.; Ji, L.-Q.; Li, S.-H.; Jiang, W.-D.; Zhang, C.-M.; Zhang, W.; Lou, Z. Laparoscopic surgery is associated with increased risk of postoperative peritoneal metastases in T4 colon cancer: A propensity score analysis. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2025, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, K.; Glenisson, M.; Loiselet, K.; Fiorenza, V.; Cornet, M.; Capito, C.; Vinit, N.; Pire, A.; Sarnacki, S.; Blanc, T. Robot-assisted laparoscopic adrenalectomy: Extended application in children. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2024, 50, 108627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, T.; Song, S.-E. Robotic Surgery Techniques to Improve Traditional Laparoscopy. JSLS J. Soc. Laparosc. Robot. Surg. 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Moreno, Y.; Echevarria, S.; Vidal-Valderrama, C.; Stefano-Pianetti, L.; Cordova-Guilarte, J.; Navarro-Gonzalez, J.; Acevedo-Rodríguez, J.; Dorado-Avila, G.; Osorio-Romero, L.; Chavez-Campos, C.; et al. Robotic Surgery: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature and Current Trends. Cureus 2023, 15, e42370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.L.; de Almeida, R.C.; Neto, T.R.; Rosa, A.A.M. Chapter 72—Robotic ophthalmologic surgery. In Handbook of Robotic Surgery; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Moreno, Y.; Rodriguez, M.; Losada-Muñoz, P.; Redden, S.; Lopez-Lezama, S.; Vidal-Gallardo, A.; Machado-Paled, D.; Guilarte, J.C.; Teran-Quintero, S. Autonomous Robotic Surgery: Has the Future Arrived? Cureus 2024, 16, e52243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Davids, J.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A.; Elson, D.S.; Sodergren, M. A systematic review of robotic surgery: From supervised paradigms to fully autonomous robotic approaches. Int. J. Med Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2021, 18, e2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Baker, T.S.; Bederson, J.B.; Rapoport, B.I. Levels of autonomy in FDA-cleared surgical robots: A systematic review. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, X.; Li, X.; Mo, H. Review of Human–Robot Collaboration in Robotic Surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Wong, S.; Razjigaev, A.; Beier, S.; Peng, S.; Do, T.N.; Song, S.; Chu, D.; Wang, C.H.; et al. A Review on the Form and Complexity of Human–Robot Interaction in the Evolution of Autonomous Surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiter, J.; Schott, D.; Schwenderling, L.; Hansen, C.; Heinrich, F.; Joeres, F. AR-Supported Supervision of Conditional Autonomous Robots: Considerations for Pedicle Screw Placement in the Future. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagnino, G.; Kundrat, D. Robot-assistive minimally invasive surgery: Trends and future directions. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 2024, 8, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinzei, K.; Hata, N.; Jolesz, F.; Kikinis, R. Surgical assist robot for the active navigation in the intraoperative MRI: Hardware design issues. In Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2000) (Cat. No.00CH37113), Takamatsu, Japan, 31 October–5 November 2000; pp. 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekos, N.V.; Khanicheh, A.; Christoforou, E.; Mavroidis, C. Magnetic Resonance–Compatible Robotic and Mechatronics Systems for Image-Guided Interventions and Rehabilitation: A Review Study. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 9, 351–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faoro, G.; Maglio, S.; Pane, S.; Iacovacci, V.; Menciassi, A. An Artificial Intelligence-Aided Robotic Platform for Ultrasound-Guided Transcarotid Revascularization. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2349–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Kwok, K.-W.; Cleary, K.; Iordachita, I.; Cavusoglu, M.C.; Desai, J.P.; Fischer, G.S. State of the Art and Future Opportunities in MRI-Guided Robot-Assisted Surgery and Interventions. Proc. IEEE 2022, 110, 968–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, J.; Tsekos, N.; Al-Ansari, A.; Abinahed, J.; Deng, Z.; Navkar, N.V. Dynamic Guidance Virtual Fixtures for Guiding Robotic Interventions: Intraoperative MRI-guided Transapical Cardiac Intervention Paradigm. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE), Taichung, Taiwan, 7–9 November 2022; pp. 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Torrealdea, F.; Bandula, S. MR Imaging-Guided Intervention: Evaluation of MR Conditional Biopsy and Ablation Needle Tip Artifacts at 3T Using a Balanced Fast Field Echo Sequence. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 32, 1068–1074.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pacia, C.P.; Gong, Y.; Hu, Z.; Chien, C.-Y.; Yang, L.; Gach, H.M.; Hao, Y.; Comron, H.; Huang, J.; et al. Characterization of the Targeting Accuracy of a Neuronavigation-Guided Transcranial FUS System In Vitro, In Vivo, and In Silico. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 70, 1528–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Becerra, J.A.; Borden, M.A. Targeted Microbubbles for Drug, Gene, and Cell Delivery in Therapy and Immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, L.J.; Isguven, S.; Eisenbrey, J.R.; Hickok, N.J.; Forsberg, F. Making waves: How ultrasound-targeted drug delivery is changing pharmaceutical approaches. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 3023–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; DU, H.; Yu, Y. Experimental study of double cable-conduit driving device for mri compatible biopsy robots. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Young, A.S.; Raman, S.S.; Lu, D.S.; Lee, Y.-H.; Tsao, T.-C.; Wu, H.H. Automatic needle tracking using Mask R-CNN for MRI-guided percutaneous interventions. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2020, 15, 1673–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, M.C.; Moreira, P.; Lezcano, D.; Foley, L.; Tuncali, K.; Tempany, C.; Kim, J.S.; Hata, N.; Iordachita, I.; Tokuda, J. In Vivo Feasibility Study: Evaluating Autonomous Data-Driven Robotic Needle Trajectory Correction in MRI-Guided Transperineal Procedures. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 8975–8982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, G.; Patel, N.; Yan, J.; Kim, G.H.; Monfaredi, R.; Cleary, K.; Iordachita, I. Remotely Actuated Needle Driving Device for MRI-Guided Percutaneous Interventions: Force and Accuracy Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019; pp. 1985–1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, S.A.; Slater, J.M.; Yang, G.Y. Image-Guided Proton Therapy: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Shin, N.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Cho, Y.J.; Jung, I.H.; Sung, J.W.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, J.W. Development of Magnetic Resonance-Compatible Head Immobilization Device and Initial Experience of Magnetic Resonance-Guided Radiation Therapy for Central Nervous System Tumors. Pr. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 14, e324–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razek, A.; Bernard, Y. Potential of Piezoelectric Actuation and Sensing in High Reliability Precision Mechanisms and Their Applications in Medical Therapeutics. Actuators 2025, 14, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Cui, M.; Wu, J.; Wei, W.; Rong, X.; Li, Y. Development of an Untethered Self-Moving Piezoelectric Actuator With Load-Carriable, Fast, and Precise Movement Driven by Piezoelectric Stack Plates. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 11635–11646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri, H.; Bernard, Y.; Razek, A. 2-D Traveling Wave Driven Piezoelectric Plate Robot for Planar Motion. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2018, 23, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri, H.; Bernard, Y.; Razek, A. A traveling wave piezoelectric beam robot. Smart Mater. Struct. 2013, 23, 025013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Dong, L.; Wang, M.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Li, Y. A wearable insulin delivery system based on a piezoelectric micropump. Sensors Actuators A: Phys. 2022, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.; Bernard, Y.; Razek, A. Design and manufacturing of a piezoelectric traveling-wave pumping device. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2013, 60, 1949–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanner, K.; Koc, B. Piezoelectric Motors, an Overview. Actuators 2016, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghenna, S.; Bernard, Y.; Daniel, L. Design and experimental analysis of a high force piezoelectric linear motor. Mechatronics 2022, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Rong, W.; Wang, L.; Xie, H.; Sun, L.; Mills, J.K. A survey of piezoelectric actuators with long working stroke in recent years: Classifications, principles, connections and distinctions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 123, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. A review on piezoelectric ultrasonic motors for the past decade: Classification, operating principle, performance, and future work perspectives. Sensors Actuators A: Phys. 2020, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Sui, F.; Liu, A.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, M.; Song, B.; Guo, Z.; Lu, S.C.-Y.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital twin-driven product design framework. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 3935–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; He, X.; Li, Z. Digital twin in healthcare: Recent updates and challenges. Digit. Heal. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Benedictis, A.; Mazzocca, N.; Somma, A.; Strigaro, C. Digital Twins in Healthcare: An Architectural Proposal and Its Application in a Social Distancing Case Study. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics 2022, 27, 5143–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Exploring the revolution in healthcare systems through the applications of digital twin technology. Biomed. Technol. 2023, 4, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Al-Jaroodi, J.; Jawhar, I.; Kesserwan, N. Leveraging Digital Twins for Healthcare Systems Engineering. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 69841–69853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Croatti, A.; Montagna, S. Pervasive and Connected Digital Twins—A Vision for Digital Health. IEEE Internet Comput. 2021, 26, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, N.; Ulapane, N.; Sloane, E.B.; Gehlot, V. Digital Twins for More Precise and Personalized Treatment. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2024, 310, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. Human Digital Twin, the Development and Impact on Design. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 23, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burattini, S.; Montagna, S.; Croatti, A.; Gentili, N.; Ricci, A.; Leonardi, L.; Pandolfini, S.; Tosi, S. An Ecosystem of Digital Twins for Operating Room Management. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 36th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), L’Aquila, Italy, 22–24 June 2023; pp. 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmann, K.; Hellings-Kuß, A.; Klodmann, J.; Richter, R.; Stulp, F.; Leidner, D. A Digital Twin Approach for Contextual Assistance for Surgeons During Surgical Robotics Training. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulakis, E.; Wang, Q.; Wu, H.; Shahriyari, L.; Fletcher, R.; Liu, J.; Achenie, L.; Liu, H.; Jackson, P.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Digital twins for health: A scoping review. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Peng, K.; Han, L.; Guan, S. Modeling and Control of Robotic Manipulators Based on Artificial Neural Networks: A Review. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Mech. Eng. 2023, 47, 1307–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetohul, J.; Shafiee, M.; Sirlantzis, K. Augmented Reality (AR) for Surgical Robotic and Autonomous Systems: State of the Art, Challenges, and Solutions. Sensors 2023, 23, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrumova, F.; Lebl, D.R. Augmented reality for minimally invasive spinal surgery. Front. Surg. 2023, 9, 1086988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Cao, J.; Deguet, A.; Taylor, R.H.; Dou, Q. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Augmented Reality in Robotic Surgery: An Initial dVRK Study Using a Surgical Education Scenario. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Symposium on Medical Robotics (ISMR), Atlanta, GA, USA; 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Rota, A.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Q.; Iovene, E.; Ferrigno, G.; De Momi, E. Recent Advancements in Augmented Reality for Robotic Applications: A Survey. Actuators 2023, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Wu, J.Y.; DiMaio, S.P.; Navab, N.; Kazanzides, P. A Review of Augmented Reality in Robotic-Assisted Surgery. IEEE Trans. Med Robot. Bionics 2019, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Qiu, X.; Xu, P.; Hu, Z.; Yan, J.; Xiang, Y.; Xuan, F.-Z. Piezoelectret-based dual-mode flexible pressure sensor for accurate wrist pulse signal acquisition in health monitoring. Measurement 2024, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Han, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Dong, Y.; et al. Kirigami-Inspired Stretchable Piezoelectret Sensor for Analysis and Assessment of Parkinson’s Tremor. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2024, 14, e2402010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, C.; Shi, C. Development of Force Sensing Techniques for Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Surgery: A Review. IEEE Trans. Med Robot. Bionics 2024, 6, 868–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Song, H. A Survey on Force Sensing Techniques in Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Surgery. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2023, 16, 702–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Cai, Z.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, M.; Liao, H.; Yi, Y. An Overview of Flexible Sensors: Development, Application, and Challenges. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, D.H.; Duraisamy, K.; Armghan, A.; Alsharari, M.; Aliqab, K.; Sorathiya, V.; Das, S.; Rashid, N. 5G Technology in Healthcare and Wearable Devices: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.C.; Suryadevara, N.K.; Nag, A. Wearable Sensors for Healthcare: Fabrication to Application. Sensors 2022, 22, 5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Biswas, N.; Jones, L.D.; Kesari, S.; Ashili, S. Smart Consumer Wearables as Digital Diagnostic Tools: A Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Linero, E.; Muñoz-Saavedra, L.; Luna-Perejón, F.; Sevillano, J.L.; Domínguez-Morales, M. Wearable Health Devices for Diagnosis Support: Evolution and Future Tendencies. Sensors 2023, 23, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelopoulos, A.; Bourbakis, N.G. A Survey on Wearable Sensor-Based Systems for Health Monitoring and Prognosis. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C Appl. Rev. 2010, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Newby, S.; Potluri, P.; Mirihanage, W.; Fernando, A. Emerging Paradigms in Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring: Evaluating the Efficacy and Application of Innovative Textile-Based Wearables. Sensors 2024, 24, 6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.S.; Lee, S.Q. A Wearable Multimodal Wireless Sensing System for Respiratory Monitoring and Analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.M.R.K.; Sherif, A. Advancement in the Cuffless and Noninvasive Measurement of Blood Pressure: A Review of the Literature and Open Challenges. Bioengineering 2022, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Yang, K.; Lu, A.; Mackie, K.; Guo, F. Sensors and Devices Guided by Artificial Intelligence for Personalized Pain Medicine. Think. Ski. Creativity 2024, 5, 0160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

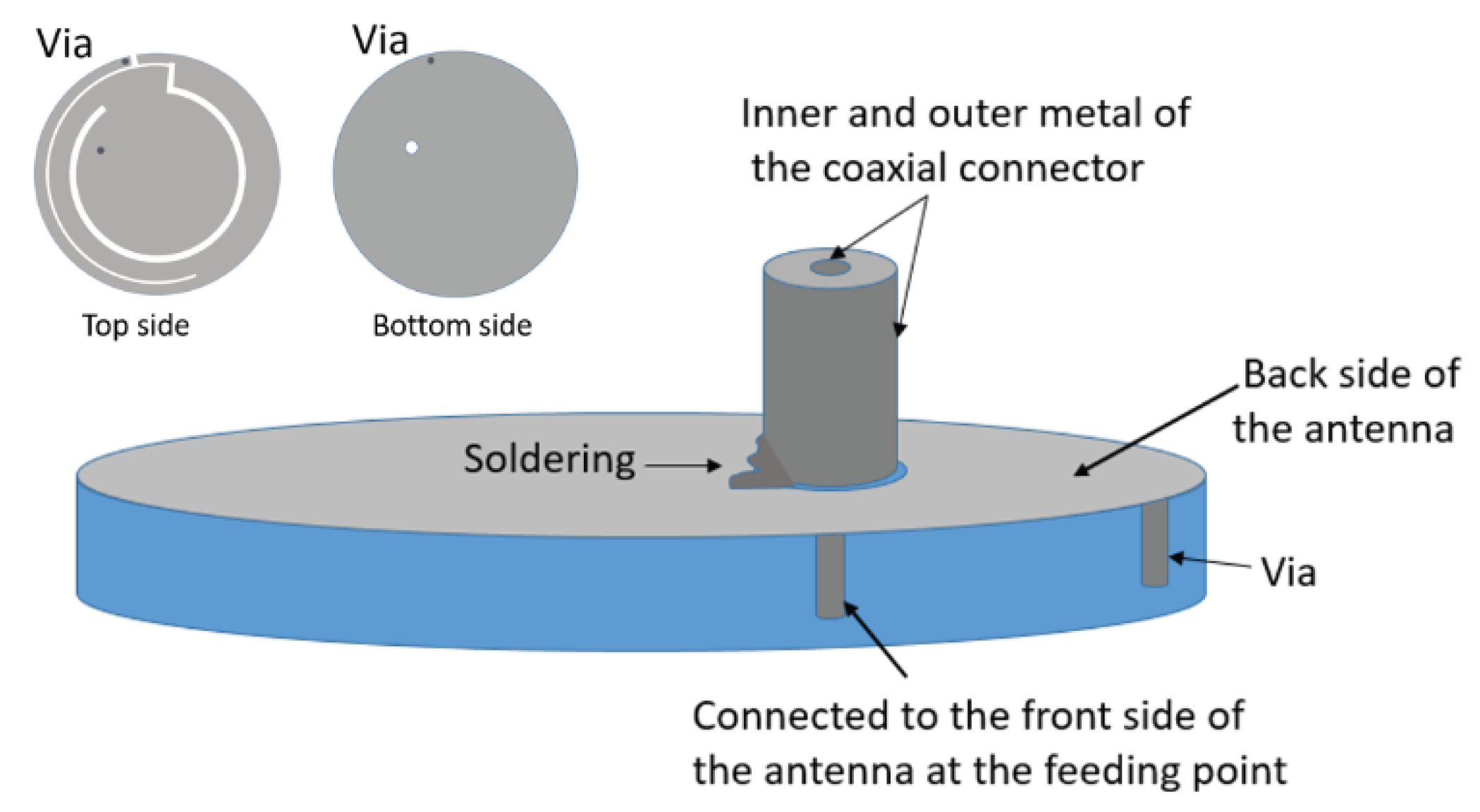

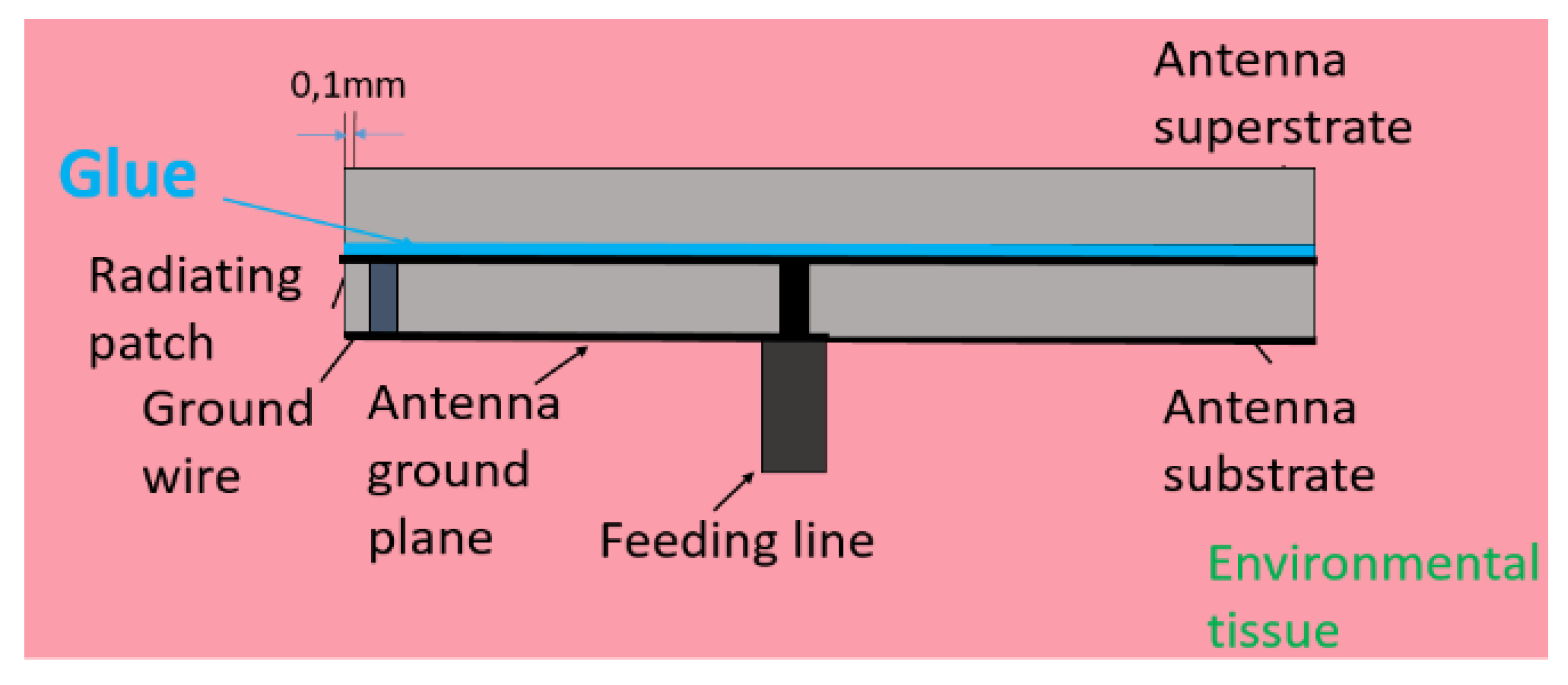

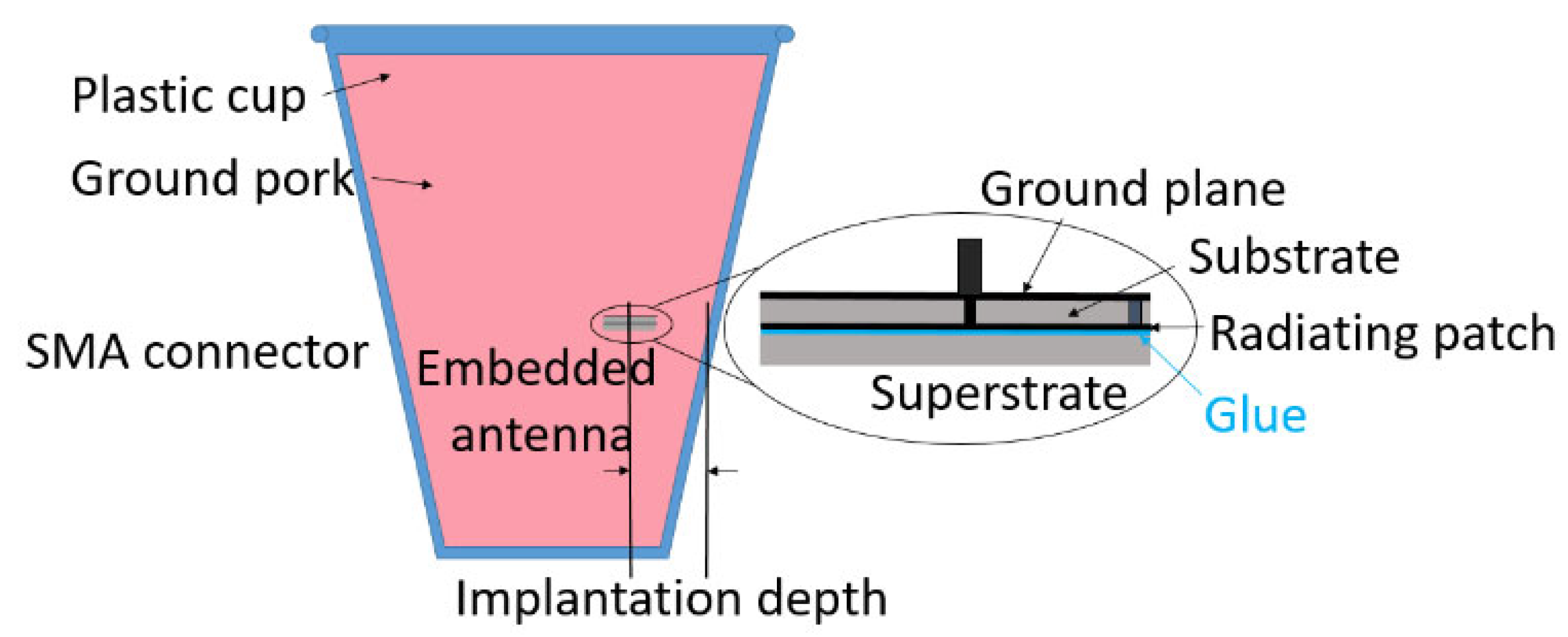

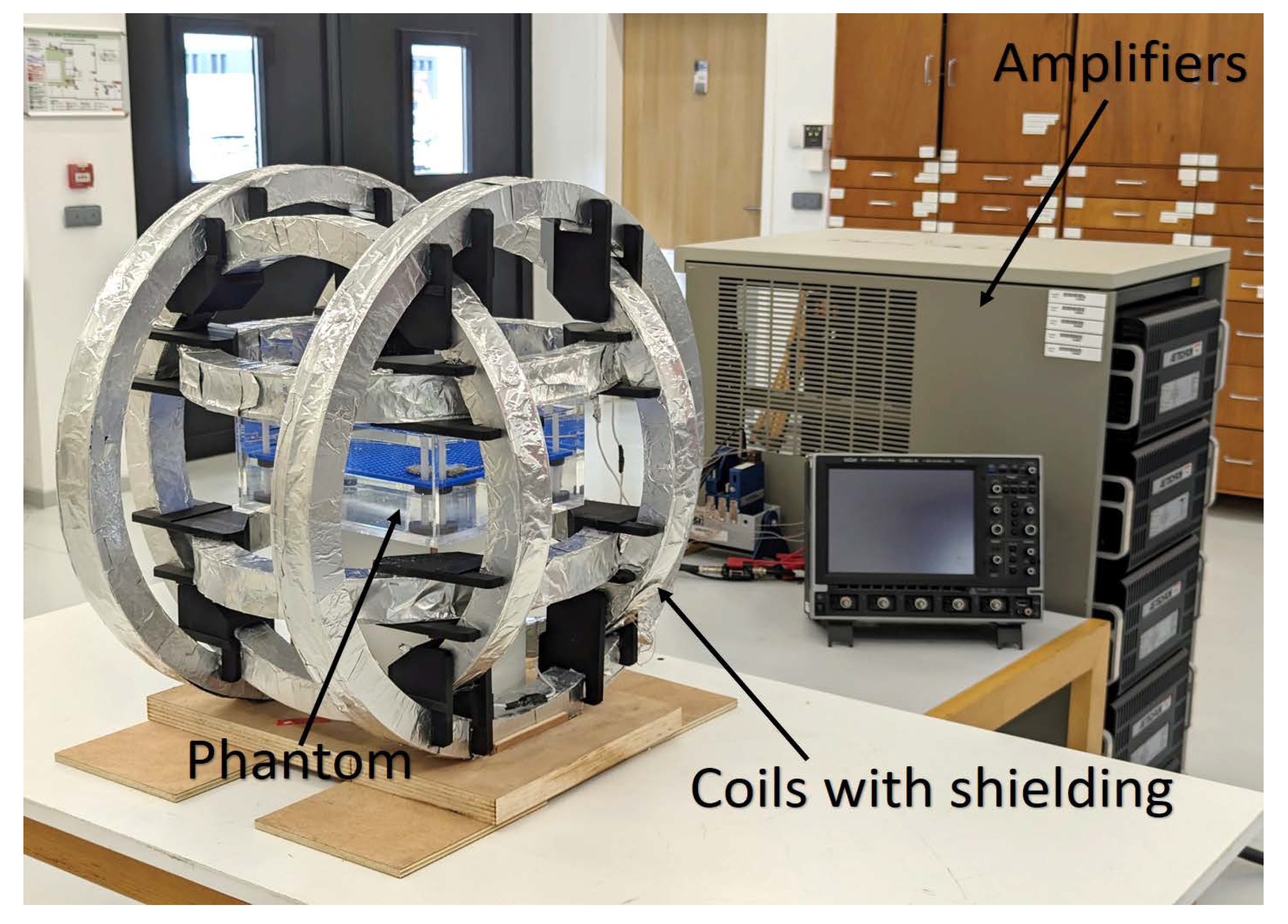

- Ding, S.; Pichon, L.; Chen, Y. A Low-Cost Microwave Stentenna for In-Stent Restenosis Detection. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2025, 73, 8681–8692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Kumar, N. Implantable antennas for biomedical applications: A systematic review. Biomed. Eng. Online 2024, 23, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliqab, K.; Nadeem, I.; Khan, S.R. A Comprehensive Review of In-Body Biomedical Antennas: Design, Challenges and Applications. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, A.M.; Kirimi, M.T.; Neale, S.L.; Mercer, J.R. Implantable Biosensors for Vascular Diseases: Directions for the Next Generation of Active Diagnostic and Therapeutic Medical Device Technologies. Biosensors 2025, 15, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudłacik-Kramarczyk, S.; Kieres, W.; Przybyłowicz, A.; Ziejewska, C.; Marczyk, J.; Krzan, M. Recent Advances in Micro- and Nano-Enhanced Intravascular Biosensors for Real-Time Monitoring, Early Disease Diagnosis, and Drug Therapy Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S. Design of a Power-Efficient Radiative Wireless System for Autonomous Biomedical Implants. PhD Thesis, Bioengineering, Université Paris-Saclay, Paris, France, 2021. (In English). [Google Scholar]

- Bhuva, A.N.; Moralee, R.; Brunker, T.; Lascelles, K.; Cash, L.; Patel, K.P.; Lowe, M.; Sekhri, N.; Alpendurada, F.; Pennell, D.J.; et al. Evidence to support magnetic resonance conditional labelling of all pacemaker and defibrillator leads in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 43, 2469–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; Yoo, J.-S.; Yoo, S.; Kim, S.; Arya, A.K.; Kim, S.; Choi, S.H.; Lu, N.; et al. Soft implantable drug delivery device integrated wirelessly with wearable devices to treat fatal seizures. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Xie, D.; Han, Y.; Guo, S.; Sun, Z.; Jing, L.; Man, W.; Liu, D.; Yang, K.; Lei, D.; et al. Precise management system for chronic intractable pain patients implanted with spinal cord stimulation based on a remote programming platform: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (PreMaSy study). Trials 2023, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, J.S.; Maynes, E.J.; O’mAlley, T.J.; Pavri, B.B.; Tchantchaleishvili, V. Electromagnetic interference between implantable cardiac devices and continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: A review. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2021, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, G.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Connolly, L.; Usevitch, D.E.; Shen, G.; Cleary, K.; Iordachita, I. A magnetic resonance conditional robot for lumbar spinal injection: Development and preliminary validation. Int. J. Med Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2023, 20, e2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Chen, W.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y. Sensing–Actuating Integrated Ultrasonic Device for High-Precision and High-Efficiency Burnishing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 72, 5199–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Feng, Z.; Yao, F.-Z.; Zhang, M.-H.; Wang, K.; Wei, Y.; Gong, W.; Rödel, J. Flexible piezoelectrics: Integration of sensing, actuating and energy harvesting. npj Flex. Electron. 2025, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdeviren, C.; Yang, B.D.; Su, Y.; Tran, P.L.; Joe, P.; Anderson, E.; Xia, J.; Doraiswamy, V.; Dehdashti, B.; Feng, X.; et al. Conformal piezoelectric energy harvesting and storage from motions of the heart, lung, and diaphragm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 1927–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, G.-T.; Byun, M.; Jeong, C.K.; Lee, K.J. Flexible Piezoelectric Thin-Film Energy Harvesters and Nanosensors for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.P.M.J.; Alluri, N.R.; Vivekananthan, V.; Chandrasekhar, A.; Khandelwal, G.; Kim, S.-J. Sustainable yarn type-piezoelectric energy harvester as an eco-friendly, cost-effective battery-free breath sensor. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Briscoe, J. Piezoelectric Energy Harvester Technologies: Synthesis, Mechanisms, and Multifunctional Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 29491–29520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.B.; Mhin, S.; Ryu, J.H.; Kim, Y.W.; Jones, J.L.; Son, Y.; Lee, N.K.; Lee, K.; et al. High-power energy harvesting and imperceptible pulse sensing through peapod-inspired hierarchically designed piezoelectric nanofibers. Nano Energy 2022, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdeviren, C.; Javid, F.; Joe, P.; von Erlach, T.; Bensel, T.; Wei, Z.; Saxton, S.; Cleveland, C.; Booth, L.; McDonnell, S.; et al. Flexible piezoelectric devices for gastrointestinal motility sensing. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, N.; Nakamura, K.; Obara, H.; Segawa, M. The strong piezoelectricity in polyvinylidene fluroide (PVDF). Ultrasonics 1976, 14, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpourfazeli, S.; Arash, S.; Ansari, A.; Yang, S.; Mallick, K.; Bagherzadeh, R. Future prospects and recent developments of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) piezoelectric polymer; fabrication methods, structure, and electro-mechanical properties. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kum, H.S.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Lindemann, S.; Kong, W.; Qiao, K.; Chen, P.; Irwin, J.; Lee, J.H.; Xie, S.; et al. Heterogeneous integration of single-crystalline complex-oxide membranes. Nature 2020, 578, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Deng, S.; Shao, J.; Si, Y.; Zhou, C.; Luo, J.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Ultrahigh-power-density flexible piezoelectric energy harvester based on freestanding ferroelectric oxide thin films. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, R. Development of flexible piezoelectric nanogenerator based on PVDF/KNN/ZnO nanocomposite film for energy harvesting application. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmal, A.; Patra, A.; Maiti, P.; Sahu, B.; Krahne, R.; Arockiarajan, A. Microstructuring of conductivity tuned piezoelectric polydimethylsiloxane/(Ba0.85Ca0.15)(Ti0.90Hf0.10)O3 composite for hybrid mechanical energy harvesting. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 11387–11402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranold, L.; Xi, J.; Goren, T.; Kuster, N. Dosimetric Electromagnetic Safety of People With Implants: A Neglected Population? Bioelectromagnetics 2025, 46, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammen, L.; Pichon, L.; Le Bihan, Y.; Bensetti, M.; Fleury, G. Testing immunity of active implantable medical devices to industrial magnetic field environments. In .Proceedings of the International Symposium and Exhibition on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Göteborg, Sweden, 5–8 September 2022; Available online: https://hal.science/hal-03779559/document.

- Hammen, L. Electromagnetic compatibility of active implantable medical devices at the workplace: The case of pacemakers. PhD Thesis, Université Paris-Saclay, Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Laganà, F.; Bibbò, L.; Calcagno, S.; De Carlo, D.; Pullano, S.A.; Pratticò, D.; Angiulli, G. Smart Electronic Device-Based Monitoring of SAR and Temperature Variations in Indoor Human Tissue Interaction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, A. Special Issue on Advanced Technologies in Electromagnetic Compatibility. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wu, X.; Su, D. A Novel Electromagnetic Compatibility Evaluation Method for Receivers Working under Pulsed Signal Interference Environment. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.C. VIII. A dynamical theory of the electromagnetic field. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1865, 155, 459–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection. Guide-lines for limiting exposure to time-varying electric and magnetic fields for low frequencies (1 Hz–100 kHz). Health Phys. 2010, 99, 818–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection. Guidelines for limiting exposure to electromagnetic fields (100 kHz to 300 GHz). Health Phys. 2020, 118, 483–524. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Standard C95.1-2019; IEEE Standard for Safety Levels With Respect to Human Exposure to Electric, Magnetic, and Electromagnetic Fields, 0 Hz to 300 GHz. IEEE Standards Association: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Makarov, S.N.; Noetscher, G.M.; Yanamadala, J.; Piazza, M.W.; Louie, S.; Prokop, A.; Nazarian, A.; Nummenmaa, A. Virtual Human Models for Electromagnetic Studies and Their Applications. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 10, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Gao, N.; Wu, B.; Chen, Z.; Xu, X.G. A Review of Computational Phantoms for Quality Assurance in Radiology and Radiotherapy in the Deep-Learning Era. J. Radiat. Prot. Res. 2022, 47, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M. Wireless Inductive Charging for Electrical Vehicles: Electromagnetic Modelling and Interoperability Analysis. PhD Thesis, University of Paris-Sud, Orsay, France, 2014. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-01127163/file/2014PA112369.

- Ding, P.-P.; Bernard, L.; Pichon, L.; Razek, A. Evaluation of Electromagnetic Fields in Human Body Exposed to Wireless Inductive Charging System. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 1037–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Deng, Z.; Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Jiao, C.; Ma, H.; Yu, Z.-Z.; Zhang, H.-B. Multifunctional and magnetic MXene composite aerogels for electromagnetic interference shielding with low reflectivity. Carbon 2023, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.; Hong, J.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, S.J. Gradient-structured MXene/ZIF/CNT hybrid films for largely enhanced electromagnetic absorption in EMI shielding. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Zhou, C.; Guo, B.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Z.; Qin, J. Mechanically strong and multifunctional nano-nickel aerogels based epoxy composites for ultra-high electromagnetic interference shielding and thermal management. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 9644–9656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Thakur, P.; Chauhan, A.; Jasrotia, R.; Thakur, A. A review on MXene and its’ composites for electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding applications. Carbon 2023, 208, 170–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Cai, Z.; Li, J.; He, M.; Qiu, H.; Ren, F.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Ren, P. Construction of rGO-MXene@FeNi/epoxy composites with regular honeycomb structures for high-efficiency electromagnetic interference shielding. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 217, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Eco-Management of Wireless Electromagnetic Fields Involved in Smart Cities Regarding Healthcare and Mobility. Telecom 2025, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, A. Digital twins for cardiovascular diseases: Towards personalised and sustainable care. Acta Cardiol. 2025, 80, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, T.; Mahajan, P.; Murthi, S.; Stegink, C.; Brawn, B.; Varshney, A.; Reddy, R.M. Role of eXtended Reality use in medical imaging interpretation for pre-surgical planning and intraoperative augmentation. J. Med Imaging 2024, 11, 062607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkefi, S.; Asan, O. Digital Twins for Managing Health Care Systems: Rapid Literature Review. J. Med Internet Res. 2022, 24, e37641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cellina, M.; Cè, M.; Alì, M.; Irmici, G.; Ibba, S.; Caloro, E.; Fazzini, D.; Oliva, G.; Papa, S. Digital Twins: The New Frontier for Personalized Medicine? Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Oh, Y.; Choi, J.; Ohm, S.-Y. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality–Based Cognitive Control Training Game for Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms: Preliminary Effectiveness Study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2025, 8, e66617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaalp, M.E.; Konstantinou, E.; Karaismailoglu, B.; Lucidi, G.A.; Kaymakoglu, M.; Vieider, R.; Giusto, J.D.; Inoue, J.; Hirschmann, M.T. The metaverse in orthopaedics: Virtual, augmented and mixed reality for advancing surgical training, arthroscopy, arthroplasty and rehabilitation. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2025, 33, 3039–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.F.; Jabeen, S.; Alwazzan, A.; Vacca, S.; Dalal, L.; Al-Haddad, B.; Jaber, A.; Ballout, F.F.; Zeid, H.K.A.; Haydamous, J.; et al. Integration of Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Extended Reality in Healthcare and Medical Education: A Glimpse into the Emerging Horizon in LMICs—A Systematic Review. J. Med Educ. Curric. Dev. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantusin, F.J.; Ortiz, J.S.; Carvajal, C.P.; Andaluz, V.H.; Yar, L.G.; Roberti, F.; Gandolfo, D. Digital Twin Integration for Active Learning in Robotic Manipulator Control Within Engineering 4.0. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, A.Y.; Wang, X.; Paxton, L. Technological Advancements in Augmented, Mixed, and Virtual Reality Technologies for Surgery: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e76428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Agrawal, S.K. Remote Extended Reality With Markerless Motion Tracking for Sitting Posture Training. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 9860–9867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Hirata, H.; Ueno, M.; Fukumori, N.; Sakai, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Tsukamoto, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Toda, Y.; et al. Digital Transformation Will Change Medical Education and Rehabilitation in Spine Surgery. Medicina 2022, 58, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Kadlubsky, A.; Svarverud, E.; Adams, J.; Baraas, R.C.; Bernabe, R.D. A scoping review of the ethics frameworks describing issues related to the use of extended reality. Open Res. Eur. 2025, 4, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saigre, T.; Prud’Homme, C.; Szopos, M.; Chabannes, V. A coupled fluid-dynamics-heat transfer model for 3D simulations of the aqueous humor flow in the human eye. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19353. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.19353.

- Qiu, Y.; Gao, T.; Smith, B.R. Mechanical deformation and death of circulating tumor cells in the bloodstream. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2024, 43, 1489–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, R.; Zhu, J.; Ma, X. A Dynamic Mechanical Analysis Device for In Vivo Material Characterization of Plantar Soft Tissue. Technologies 2025, 13, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinchurkar, K.; Bukke, S.P.N.; Jain, P.; Bhadoria, J.; Likhariya, M.; Mane, S.; Suryawanshi, M.; Veerabhadrappa, K.V.; Eftekhari, Z.; Onohuean, H. Advances in sustainable biomaterials: Characterizations, and applications in medicine. Discov. Polym. 2025, 2, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Kim, Y.-M.; Lee, T.; Lee, S.-M.; Jung, J.; Bae, H.-M.; Kim, C.; Lee, H.J. Patch-type capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducer for ultrasonic power and data transfer. Microsystems Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Torre, K.; Min, S.; Lee, H.; Kang, D. The Application of Preventive Medicine in the Future Digital Health Era. J. Med Internet Res. 2025, 27, e59165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizna, S.; Arora, S.; Saluja, P.; Das, G.; Alanesi, W.A. An analytic research and review of the literature on practice of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Eur. J. Med Res. 2025, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowri, V.; Uma, M.; Sethuramalingam, P. Machine learning enabled robot-assisted virtual health monitoring system design and development. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2024, 7, 2259–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, S.; Giuliani, G.; Lasciarrea, A. A Digital Twin System to Enable Better Healthcare Management. In Hybrid Human-AI Collaborative Networks. PRO-VE 2025. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Camarinha-Matos, L.M., Ortiz, A., Boucher, X., Lucas Soares, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Swirzerland, 2026; p. 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).