1. Introduction

Work-related stress is a widely recognized challenge for teachers’ occupational health and job performance (Kyriacou, 2001, 2011; Kyriacou & Sutcliffe, 1978), emerging as a primary cause of burnout, a syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced professional accomplishment (Maslach et al., 2001; Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Teachers face high job demands daily (e.g., quantitative and qualitative workload, role conflict, interpersonal conflicts and challenging relationships with colleagues, school leaders, and parents, pupil misbehavior, unfavorable work schedules and work conditions), while being pressured to maintain a good job performance and ensure their students’ academic, social and emotional success (Kyriacou, 2011; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014; Taris et al., 2017). Grounded in Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) Transactional Model of Stress and Demerouti et al.’s (2001) Job Demands and Resources (JD-R) model, a substantial body of literature highlights how these persistent work-related stressors contribute to teacher chronic occupational stress and burnout (e.g., Cheng et al., 2023; Kyriacou, 2001; Maslach & Leiter, 2016; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017, 2018; Taris et al., 2017; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Teachers’ occupational health is thus a critical global issue today. A systematic review by von der Embse et al. (2019) reported that approximately 30% of teachers experienced clinically significant levels of stress, a number that has increased drastically in recent years (Kotowski et al., 2022). With teachers experiencing above-average levels of occupational stress for decades (Collie & Mansfield, 2022), many educational systems are struggling to retain qualified teachers. Chronic work-related stress and burnout lead to negative affect, reduced job satisfaction, diminished teaching effectiveness, and higher attrition rates and turnover (Madigan & Kim, 2021; Von Der Embse & Mankin, 2021). These factors are fueling a growing teacher retention crisis worldwide, which has become a central policy concern with significant repercussions for education quality and student outcomes (UNESCO, 2024; Viac & Fraser, 2020). Addressing these interconnected problems demands a clear understanding, both theoretically and empirically, of the mechanisms underlying teacher work-related stress and burnout, including the individual, contextual, and temporal factors that may shape them. There is, therefore, at both a political and social level, a pressing need to address teachers’ occupational health to enhance attractiveness and improve retention. Teachers’ demographic characteristics also warrant attention as prior studies indicate that stress levels vary by educational level taught, gender, and career stage, with younger and female teachers in elementary education often reporting greater vulnerability (e.g., OECD, 2020).

Moreover, teachers’ occupational stress does not occur in a vacuum, but it is significantly amplified by macro-level societal disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Collie, 2021; Kotowski et al., 2022). In today’s increasingly BANI (Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, and Incomprehensible) world, marked by instability and ambiguity, it is essential to understand how teachers adapt to and are impacted by ongoing uncertain and structural changes. This understanding is vital for preparing educational systems to better support teachers during challenging times. To do so, we need not only to understand teachers’ job demands during times of adversity, but also to learn how to better empower teachers to handle these strains. Accordingly, our study aimed to investigate the evolution of elementary school teachers’ occupational health between Fall 2019 and Summer 2021. Furthermore, we explored the supportive role of contextual job resources, namely organizational climate, in buffering the impact of occupational stress on burnout during this period. Although our data captures a historically bounded context during the peak and immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the structural and psychological pressures experienced by teachers have not ended; instead, they have persisted and evolved into a “new normal” marked by heightened demands, digitalization, and intensified accountability (e.g., Varela et al., 2022). Thus, while temporally anchored in the pandemic era, our findings remain relevant for informing strategic policies and practices aimed at supporting teacher occupational health within the increasingly volatile and demanding post-pandemic educational systems.

1.1. Impacts of COVID-19 on Teacher Occupational Health

Pandemics have historically disrupted social systems, and COVID-19 was no exception, posing the most significant global challenge in a generation. As a result, researchers worldwide have studied its effects on health, economy, and daily life (Gavin et al., 2021). Among its many impacts, it profoundly disrupted education systems, placing unprecedented demands on teachers worldwide (UNESCO et al., 2022). The sudden shift to emergency remote teaching required educators to rapidly adapt to new instructional methods while managing the emotional toll of working in a crisis (Baker et al., 2021; Kraft et al., 2021; Sokal et al., 2020). The pandemic has intensified job demands, diminished professional efficacy, and placed additional strain on teacher-student and teacher-colleague interactions, all of which are critical factors in occupational health and job satisfaction (Collie, 2021; UNESCO et al., 2022). However, most empirical studies conducted during this period used cross-sectional designs, capturing isolated snapshots of a complex and evolving phenomenon (e.g., fatigue levels during lockdowns) (e.g., Kim & Asbury, 2020; MacIntyre et al., 2020; Sokal et al., 2020). Burnout, particularly emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment indicators, is conceptualized as a dynamic, time-sensitive phenomenon that fluctuates in response to evolving job demands and resources (Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Cross-sectional data are therefore insufficient to capture whether burnout experiences intensify, plateau, or fade over time, or how contextual factors like organizational climate affect various stages of burnout development. Therefore, longitudinal designs are necessary not only to model burnout development patterns across critical transitions but also to test whether protective factors such as a positive organizational climate may impact this trajectory. By leveraging a multi-wave design, our study was able to capture both immediate and delayed impacts of COVID-19, going beyond the common static snapshots in post-pandemic educational research. It also contributes to existing literature by explicitly examining the protective role of job resources during this period, which remains an understudied topic (Collie, 2021; Pressley, 2021).

Furthermore, despite growing recognition that teacher burnout varies across sociocultural settings (e.g., García-Arroyo et al., 2019; García-Arroyo & Osca Segovia, 2018), most empirical work has been conducted in Anglo-American or Northern European educational systems. These findings may not generalize to Southern European contexts like Portugal, where the educational system is characterized by a distinct organizational structure and socio-political context (Pimenta et al., 2023). Evidence from the Portuguese context remains scarce (e.g., Mota et al., 2021), despite consistent reports of Portuguese employees being among the most vulnerable to burnout (Small Business Prices, 2022), particularly in the education sector (Gaspar et al., 2023, 2025; Varela et al., 2018, 2022). Portuguese teachers face above-average stress levels and significant health risks, citing long working hours, low salaries, high administrative burden, and job dissatisfaction as key psychosocial risk factors (OECD, 2020). Recent reports further indicate that pandemic-induced work-related stressors have persisted beyond the crisis peak, becoming embedded in teachers’ everyday realities (UNESCO, 2024; UNESCO et al., 2022).

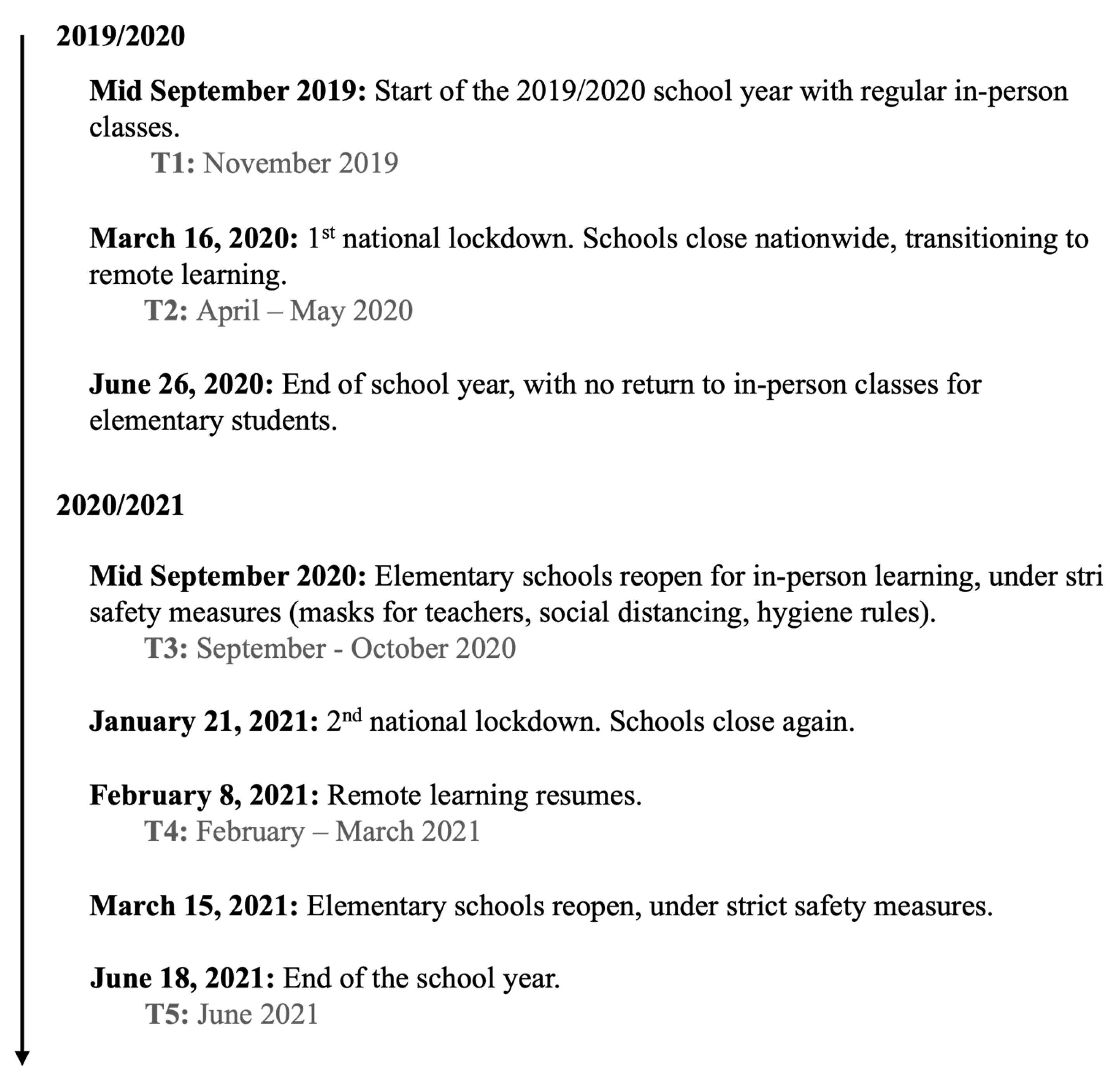

During the 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 school years, Portuguese elementary schools were affected by several key COVID-19 events, including a sequence of closures, partial reopenings, and stringent health protocols (

Figure 1). Although the pandemic affected all educational levels, national studies have shown that the occupational health of elementary school teachers was most significantly impacted (Alves et al., 2020), likely due to the intensive caregiving and affective labor involved in early education (Smith et al., 2025). During these shifting conditions, teachers had to adapt and continue to teach while facing increased job demands and personal and social challenges. While navigating the two national lockdowns, teachers faced unique stressors trying to maintain educational quality and support students’ well-being. Although teachers have been performing roles beyond “traditional” teaching (e.g., Gilligan, 1998; Oliveira et al., 2025), these demands grew during the pandemic (Kim et al., 2024), increasing teachers’ mental health risks (Smith et al., 2025). With the pandemic catalyzing disruptions in teaching, teachers’ professional reality is now, more than ever, shaped by a fast-paced and shifting context (UNESCO et al., 2022). In this context, understanding how these challenging times affect teachers and how we can better support them is essential.

A growing body of research reports a decline in teachers’ sense of professional success during the pandemic, often accompanied by heightened stress, frustration, and emotional exhaustion (e.g., Kraft et al., 2021). Drawing on the Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2001), teachers’ reduced personal accomplishment (i.e., also referred to as low sense of professional efficacy) plays a central role in the burnout process (Llorens et al., 2005). Persistent exposure to work-related stressors can erode teachers’ confidence in their ability to meet job demands, triggering burnout. While no single developmental model of burnout is universally accepted, diminished professional efficacy is a consistent and inevitable factor (Bresó et al., 2007). Recent research further identifies distinct burnout profiles, illustrating how enthusiasm, commitment, and engagement may progressively deteriorate over time, leading to a reduced sense of professional efficacy and reliance on passive coping strategies (Edú-Valsania et al., 2022; Montero-Marín et al., 2014). Understanding how these processes unfolded during the pandemic offers valuable insights for decision-making aimed at strengthening teachers’ personal accomplishment and engagement, ultimately helping prevent burnout in future crises. Moreover, the Portuguese educational system faces unique organizational challenges, including high workloads, centralized governance, and an aging workforce, which may interact and shape work-related stress and burnout differently (Oliveira et al., 2025; Varela et al., 2022). Addressing these context-specific dynamics is not only important for local policy and intervention efforts but also broadens the cross-cultural validity of occupational health models in education (García-Arroyo et al., 2019).

1.2. The Role of Contextual Job Resources

Anchored in the JD-R model, burnout stems from chronic experiences of work-related stress, caused by a perceived prolonged and cumulative imbalance between excessive job demands and insufficient job and personal resources available to manage them (Kyriacou, 2011; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Teacher burnout is conceptualized as a three-dimensional occupational syndrome comprising emotional exhaustion (i.e., feeling emotionally depleted by one’s work), depersonalization (i.e., adopting an impersonal and detached attitude toward students), and reduced personal accomplishment (i.e., diminished sense of professional efficacy and fulfillment at work) (Maslach et al., 2001; Maslach & Leiter, 2016). The JD-R model identifies two distinct processes through which job demands and resources influence employees’ occupational health: 1) the health impairment process in which excessive job demands, when not properly managed, lead to strain and exhaustion, and 2) the motivational process in which the presence of high job and personal resources promotes increased motivation, work engagement, and performance (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). While job demands are often structurally embedded and difficult to eliminate, enhancing personal and job resources represents a viable and evidence-based strategy for sustaining teachers’ occupational health, helping them cope with job demands, and maintaining motivation.

Research consistently shows that workplace conditions have a significant impact on teachers’ occupational health (Taris et al., 2017). Social aspects of the work environment have a particularly strong influence on teachers’ occupational health (Trauernicht et al., 2025). Specifically, social support, leadership quality, collegial relationships, and a positive organizational climate have all been shown to promote teacher occupational health and well-being (Brackett & Cipriano, 2020; Hascher & Waber, 2021). In highly relational professional environments such as teaching, exchanges in social interactions with students, colleagues, superiors, parents, and school staff are frequent, making positive social relations essential for fulfilling teachers’ need for social relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Positive relationships with colleagues and parents appear to have a particularly significant impact on teachers’ work experiences (Trauernicht et al., 2025).

In this scenario, organizational climate has emerged as a critical job resource. Empirical studies link positive organizational climate to higher job satisfaction, efficacy, and occupational health (Collie et al., 2012; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2018). During the pandemic, studies reinforced the significance of social workplace aspects (e.g., social support, positive team climate) in sustaining teachers’ well-being (Trauernicht et al., 2025). Blaydes et al. (2024) found that helpful actions from school leaders, colleagues, and parents were the teachers’ most reported resources during the pandemic. However, most of this evidence is based on short-term or cross-sectional designs and qualitative data, leaving unanswered questions about how organizational climate functions as a sustained protective factor over extended periods of disruption. This question is particularly pressing in educational systems where social and institutional support mechanisms are already constrained. In Portuguese elementary schools, where teachers report limited access to collaborative professional cultures and supportive leadership (Oliveira et al., 2022, 2023, 2025), the buffering potential of a positive organizational climate may be even more critical.

1.3. The Present Study

While many studies have documented the immediate impacts of the pandemic on teachers’ outcomes, few have explored how teacher work-related stress and occupational health evolved throughout prolonged disruptions (Von Der Embse & Mankin, 2021). Likewise, there remains a scarcity of research addressing how teachers’ occupational stress and health fluctuate throughout the school year (Von Der Embse & Mankin, 2021). Understanding the long-term impact of major disruptions on occupational health is essential, particularly in today’s BANI world. Policymakers and schools must proactively strengthen teachers’ job and personal resources not only to react to disruption but to maintain teachers’ occupational health and well-being. One key protective factor is organizational climate, an essential job resource that encompasses leadership practices, colleagues’ and supervisors’ social support, and workplace policies that influence teacher well-being and performance (Collie et al., 2012). Previous research has demonstrated that a positive organizational climate can buffer occupational stress and burnout and foster teachers’ personal resources (Oliveira et al., 2022). However, its role in mitigating work-related stress and burnout during extended periods of disruption remains insufficiently explored.

This study addresses these gaps by examining the occupational health trajectories of Portuguese elementary school teachers across two pandemic-affected school years, capturing both the acute and extended effects of systemic disruption. Building on previous literature, we also explored the role of contextual job resources, namely organizational climate, in supporting teachers’ occupational health, particularly during ongoing disruptions and changes. Our study addressed the following research questions:

Q1: How did teachers’ occupational stress and burnout indicators vary throughout two school years during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Q2: What were the main work-related stressors experienced by teachers during this period?

Q3: How did the social environment of the workplace impact teachers’ occupational health during the pandemic?

We also tested the following hypothesis:

H1. Organizational climate will moderate the effect of occupational stress on teacher burnout, such that a positive organizational climate reduces the impact of work-related stress on burnout and its indicators.

By answering these questions, our study contributes to a more nuanced and longitudinal understanding of how work-related stressors and organizational climate shape teacher burnout trajectories in times of prolonged disruption, providing insights into strategies for supporting educators during challenging times. The findings aim to inform future policies and interventions aimed at fostering healthier and more sustainable work environments for teachers, ultimately enhancing both educators’ retention and performance, as well as students’ academic success.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

A convenience sample of 101 elementary school Portuguese teachers (94.1% women, M = 46.03 years, SD = 5.12, range: 28–62 years) participated in the study. Participants were practicing at 14 state elementary schools across three different school clusters in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. Teachers had a mean of 15.69 years of overall teaching experience (SD = 8.56, range: 1–36), with an average of 8.95 years (SD = 6.92, range: 1–24) at their current school cluster. Most teachers (98.48%) had permanent contracts and held a degree (93.9%). The three school clusters had similar organizational structures, socioeconomic level, and size. The total eligible population of the school clusters was 118 teachers, and after ensuring voluntary participation, the enrollment rate was 85.6%.

We collected data through an online survey using the Qualtrics platform. As the pandemic was unforeseen, stress and burnout evolution were assessed in a five-wave repeated cross-sectional study: T1 (pre-pandemic, Nov 2019, n = 66), T2 (1st lockdown, Apr/May 2020, n = 73), T3 (return to in-person teaching, Sep/Oct 2020, n = 81), T4 (2nd lockdown, Feb/Mar 2021, n = 76), and T5 (end of school year back to in-person teaching, Jun 2021, n = 74). To mitigate the limitation of independent samples, we asked participants if they had responded to prior data collection waves. Of the initial 66 teachers, 65 also participated in T2 (98.5%) and 57 enrolled in T3 onwards (86.4%). Of the 101 teachers who integrated the sample, thirty-five teachers did not enroll in the study from the first data collection wave. For moderation analysis, we conducted a longitudinal study with three data collection waves paired (T3 onwards).

Teachers were contacted via email, informed of the study’s purpose, and asked for their consent to participate. Voluntary participation and the possibility of dropout were guaranteed, and confidentiality and anonymity of the data were ensured. The survey lasted approximately 15 minutes, and validity checks were included to ensure the accuracy of responses. Only complete responses were considered. Text entry boxes were used to collect sociodemographic data, which helped detect random responses, spam, or the use of autofill software. Additionally, a statement encouraging honesty was included to reduce social desirability bias. The authors had no prior relationship with the participants, and no compensation was offered.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perceived Occupational Stress

Overall occupational stress was measured, at all data collection waves, with a single item (adapted from Kyriacou & Sutcliffe, 1978) by asking teachers, “To what extent do you consider that being a teacher, in general, was a stress-generating activity over the past two months?” The item was rated on a 5-point scale (1—Not stress-generating at all to 5—Extremely stress-generating). At T2, teachers also identified up to 10 main workplace stressors experienced during the first COVID-19 lockdown (in an open-ended question), rating the frequency of each on a 7-point scale (0 – Never to 6 – Every day).

2.2.2. Burnout

We used the Portuguese adaptation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory - Educators Survey (Marques-Pinto et al., 2005) to measure burnout indicators through 22 items addressing Emotional exhaustion (0.85 < ωT1–T5 < 0.93), Depersonalization (0.68 < ω T1–T5 < 0.88), and Personal accomplishment (0.65 < ω T1–T5 < 0.84). Answers were given on a 7-point Likert scale (0—Never to 6—Every day).

2.2.3. Organizational Climate

Teachers’ perceptions of their school climate were assessed using the 40-item Portuguese version of the Organizational Climate Description Questionnaire Revised for Elementary Schools (0.86 < ω T2–T5 < 0.88; Oliveira et al., 2023). Items were evaluated on a 4-point scale (1—Rarely occurs to 4—Very frequently occurs). Organizational climate was only measured at T2 and subsequently.

2.3. Data Analysis

We conducted a mixed deductive/inductive thematic content analysis using MAXQDA software to analyze perceived workplace stressors following Bardin’s guidelines (1977) and the JD-R model (Demerouti et al., 2001; Taris et al., 2017). Deductive analysis identified initial categories (e.g., quantitative and qualitative workload), while inductive analysis of specific demands and (lack of) resources emerging from teachers’ responses further refined and consolidated the category system (e.g., challenging parent-teacher interactions). To ensure the validity of the analysis, the assumptions of exclusivity, homogeneity, pertinence, objectivity, and productivity were assured during the coding process (Bardin, 2000). To ensure reliability, an independent coder reviewed the category system and discussed divergences with the first author until full agreement was attained. We used MAXQDA’s Code Relations Browser to explore relationships within the (sub-)category system (Gizzi & Rädiker, 2021). We observed sub-category co-occurrences for each participant to facilitate the identification of patterns, interactions, and interpretation of the data (Magnani & Gioia, 2023). A frequency analysis of teachers’ perceived stressors was conducted using SPSS Statistics 29.

For hypothesis testing, we used R (version 4.4.1; R Core Team, 2023). Descriptive statistics and preliminary analyses were employed to examine data distribution, identify missing values, and detect outliers. As the software notified participants of the need to complete their responses before submission, there were no missing values. Q-Q plot analysis indicated a near-normal distribution of the data (i.e., |z| < 3; Kline, 2016). Internal consistency was assessed with coefficient omega (ω), with values ≥ .70 considered good (Crutzen & Peters, 2017). Owing to the sample size within the data collection points, all analyses were performed using robust statistics. Robust one-way ANOVAs based on trimmed means (20% trimming) and post-hoc tests (WRS2 package; Mair & Wilcox, 2020) were performed to assess changes in occupational stress and burnout indicators over time (T1-T5). To account for family-wise error rates, the Holm-Bonferroni method was used for multiple comparisons (Maechler et al., 2024; Mair & Wilcox, 2020). To examine the relationship between organizational climate and burnout, Spearman correlations were computed, and robust linear regression models were performed (robustlmm package; Koller, 2016) to evaluate whether perceived organizational climate predicted teachers’ burnout symptoms at T2. Values around 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 illustrate small, moderate, and large associations, respectively (Cohen, 2013).

Robust multiple regression, conducted with the robustbase package for R (Maechler et al., 2024), was employed to explore the moderating effect of organizational climate measured at T4 on the relationship between occupational stress measured at T3 and burnout indicators measured at T5. The interaction term between occupational stress and organizational climate was included. Variables were mean-centered to reduce multicollinearity. Simple slope analyses were conducted to interpret the nature of moderation at different levels of the moderator. Effect sizes with 95% CI with bootstrap were calculated for robust one-way ANOVAs using the Partial Eta Squared (η2), and for robust regression using Cohen’s f (f2). All analyses were conducted with a significance level of p < 0.05 whenever the 95% bootstrapped CI did not include 0.

3. Results

3.1. Occupational Stress and Burnout Evolution Across Time: Five-Wave Repeated Cross-Sectional Study

We found statistically significant differences for personal accomplishment (

F(4, 109.57) = 3.41,

p = 0.011,

η2 = 0.28, 95% CI [0.16, 0.47]), with teachers reporting a significant decrease in sense of professional efficacy in the first lockdown, compared with the other four data collection points (T1:

= −0.46, 95% CI [−0.90, −0.02], T3:

= 0.48, 95% CI [0.06, 0.90], T4:

= 0.49, 95% CI [0.05, 0.92], T5:

= 0.46, 95% CI [0.02, 0.90]). Despite slight variations in the mean scores (

Table 1) for the remaining variables, no statistically significant differences were found regarding occupational stress (

F(4, 108.15) = 0.75,

p = 0.563,

η2 = 0.15, 95% CI [0.06, 0.25]), overall burnout (

F(4, 110.04)=2.03,

p = 0.095,

η2 = 0.21, 95% CI [0.10, 0.35]), emotional exhaustion (

F(4, 109.83) = 0.63,

p = 0.645,

η2 = 0.16, 95% CI [0.06, 0.26]), and depersonalization (

F(4, 105.97) = 1.13,

p = 0.346,

η2 = 0.17, 95% CI [0.08, 0.29]) across the assessed period.

3.2. Main Workplace Stressors Experienced During COVID-19

Analysis produced 18 sub-categories of main workplace stressors experienced during COVID-19 (13 sub-categories referred to job demands, one category related to broader social demands, and four sub-categories depicted negative outcomes), with a total of 293 recording units coded (see

Supplemental Table S1 for details). Among job demands, teachers perceived Quantitative Workload (70.9%) and Demanding Interactions with students (45.5%) and their parents (41.8%) as the most prominent sources of strain. These stressors frequently co-occurred with Work Reorganization (43.6%) and Unfavorable Work Conditions (25.5%), suggesting that the demands for constant structural and procedural adaptations increased the burden on teachers. Furthermore, IT constraints (38.2%) associated with the use of technology for teaching both by teachers and their students were also frequently referred to by teachers, highlighting the digital challenges in teaching environments. Work-life conflict (16.4%) was also reported, and it co-occurred with teachers’ references to Qualitative Work Overload (21.8%), Emotional Demands at work (12.7%), and Unfavorable Work Schedules (18.2%).

On the other hand, the (Lack of) Social support by colleagues and superiors, with feelings of work isolation (16.4%), was the only job resource to be mentioned by the teachers as a frequent source of stress. References to (Lack of) Social support co-occurred with various job demands (e.g., quantitative workload, demanding interactions and interpersonal conflicts, work reorganization, inadequate work conditions). Along with these direct workplace stressors, teachers also reported two main negative outcomes as causing increased strain: Physical and mental health complaints (12.7%) and Negative emotions (10.9%).

Teachers reported encountering most of the 18 identified stressors weekly, with a median frequency of 4.00. Regarding demographic characteristics, male teachers reported mainly Quantitative workload, and did not refer to strain related to Qualitative work overload, Unfavorable Work Schedules, Emotional demands, or Interpersonal conflicts. In addition, younger teachers reported more Work-life conflict and Unfavorable Work Schedules. In comparison, older teachers reported more Demanding Interactions with parents and strain related to Work Reorganization, Qualitative work overload, and IT constraints.

3.3. Relation Between Organizational Climate, Work-Related Stress, and Burnout Indicators: Three-Wave Longitudinal Study

Correlation analysis (

Table 2) indicated that organizational climate was associated with personal accomplishment at T2. A subsequent robust linear regression analysis (at T2) revealed that organizational climate was a positive predictor of personal accomplishment (

B = 0.74,

SE = 0.32, 95% CI [0.09, 1.38],

p = .025,

R2 = 0.13,

f2 = 0.14) but did not predict emotional exhaustion or depersonalization. Emotional exhaustion was positively predicted by stress (

B = 0.70,

SE = 0.12, 95% CI [0.46, 0.94],

p < 0.001,

R2 = 0.28,

f2 = 0.39), while depersonalization was positively predicted by emotional exhaustion, but not by stress (

B = 0.24,

SE = 0.09, 95% CI [0.05, 0.42],

p = 0.015,

R2 = 0.10,

f2 = 0.11). Personal accomplishment was not predicted by either emotional exhaustion or depersonalization.

3.3.1. Moderation Analysis

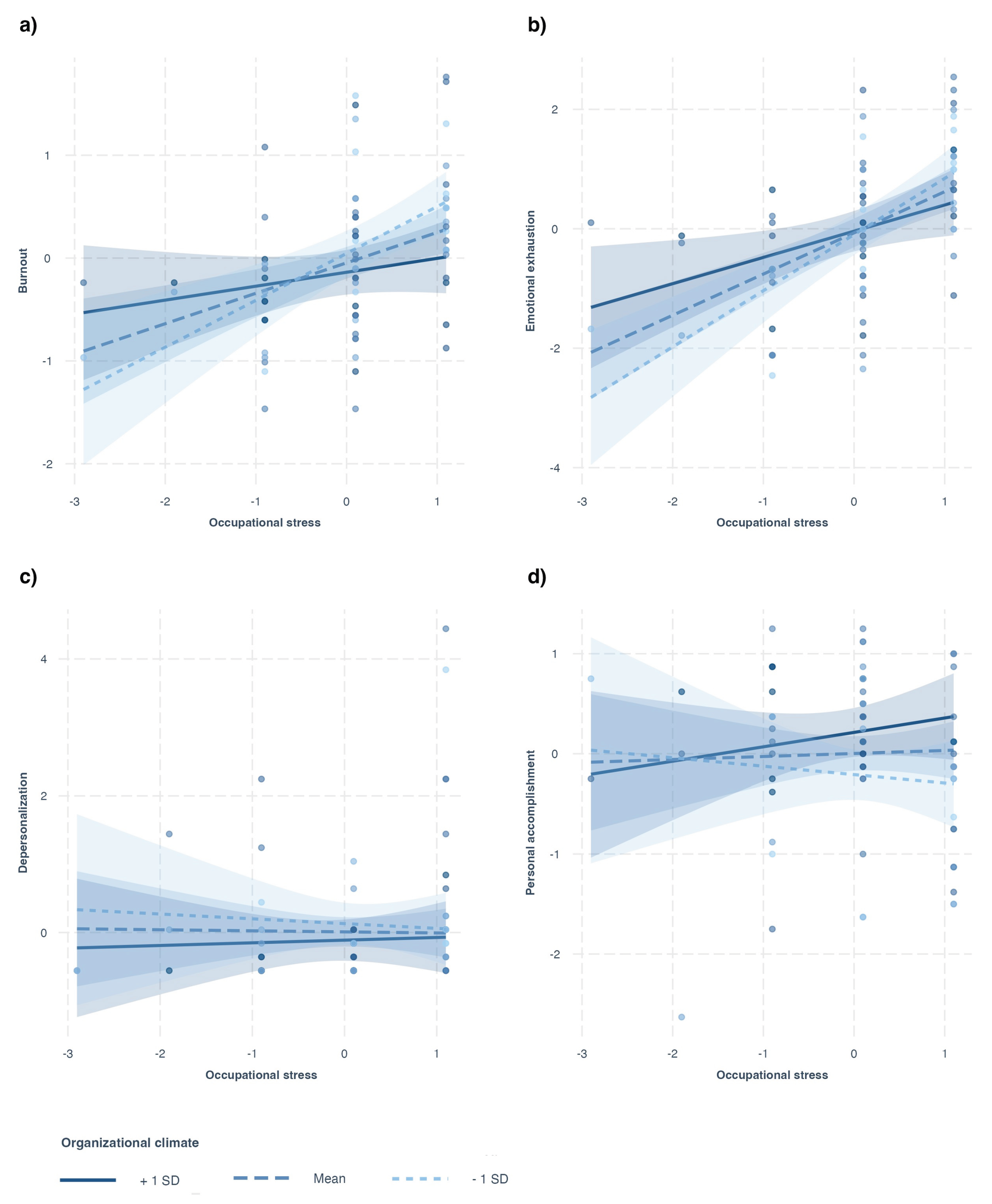

Burnout

The interaction between occupational stress and organizational climate was significant (

B = −0.54,

SE = −0.54,

t = −2.09,

p = 0.039), indicating that the effect of occupational stress on burnout varied by organizational climate (

Figure 2a). There was a significant main effect of stress (

B = 0.29,

SE = 0.08,

t = 3.53,

p < 0.001), but not of organizational climate (

B = −0.31,

SE = 0.26,

t = −1.17,

p = 0.244). The model explained 20% of the variance in emotional exhaustion [

F(3,70) = 6.97,

p < 0.001, adjusted

R² = 0.20].

Analysis of simple slopes showed that the positive relationship between occupational stress and burnout was strongest at low levels of organizational climate (B = 0.46, SE = 0.11, t = 4.05, p < 0.001), lower at the mean level of organizational climate (B = 0.30, SE = 0.08, t = 3.58, p < .001), and non-significant at a more positive organizational climate (B = 0.14, SE = 0.11, t = 1.20, p = 0.23). These results support the moderating role of organizational climate in the relationship between occupational stress and burnout, suggesting that as organizational climate becomes more positive, the impact of work-related stress on burnout becomes weaker.

Emotional Exhaustion

The interaction between occupational stress and organizational climate was significant (

B = −0.83,

SE = 0.35,

t = −2.41,

p = 0.018), indicating that the effect of occupational stress on emotional exhaustion depended on organizational climate (

Figure 2b). There was a significant main effect of stress (

B = 0.68,

SE = 0.15,

t = 4.51,

p < 0.001). In contrast, the main effect of organizational climate was not significant (

B = 0.07,

SE = 0.36,

t = 0.19,

p = 0.85). The model explained 30% of the variance in emotional exhaustion [

F(3,71) = 11.66,

p < 0.001, adjusted

R² = 0.30].

Analysis of simple slopes showed that the positive relationship between occupational stress and emotional exhaustion was strongest at low levels of organizational climate (B = 0.94, SE = 0.17, t = 5.40, p < 0.001), and weakest at a more positive organizational climate (B = 0.44, SE = 0.18, t = 2.50, p = 0.01). This pattern indicates that as the organizational climate becomes more positive, the impact of work-related stress on emotional exhaustion becomes weaker.

Depersonalization

For this model, following prior literature (e.g., Bresó et al., 2007), we tested two predictors of depersonalization, namely occupational stress and emotional exhaustion. The interactions between organizational climate and occupational stress (

p = 0.712) and emotional exhaustion (

p = 0.936) were not significant, indicating that the effects on depersonalization did not depend on organizational climate (

Figure 2c). There was a significant main effect of emotional exhaustion (

B = 0.30,

SE = 0.10,

t = 2.87,

p = 0.005) on depersonalization, but not of occupational stress or organizational climate. The model explained 10% of the variance in depersonalization [

F(5, 70) = 2.67, p = 0.028, adjusted

R² = 0.10].

Personal Accomplishment

Following prior literature (e.g., Bresó et al., 2007), we tested whether occupational stress, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization predicted personal accomplishment, and whether organizational climate moderated these relationships. The overall model was significant, explaining 15% of the variance in personal accomplishment [F(7, 68) = 2.94, p = 0.010, adjusted R² = 0.15], with significant main effects of organizational climate (B = 0.70, SE = 0.29, t = 2.37, p = 0.021) and depersonalization (B = −0.31, SE = 0.10, t = −3.01, p = 0.004) on personal accomplishment. However, none of the interaction terms with organizational climate (i.e., moderation effects) reached significance (p > 0.05), indicating no evidence that organizational climate moderated the impact of work-related stress, emotional exhaustion, or depersonalization on personal accomplishment.

4. Discussion

Our study aimed to understand how Portuguese elementary-school teachers’ occupational health, specifically their occupational stress and burnout indicators, evolved throughout the COVID-19 pandemic (from Fall 2019 to Summer 2021), and to investigate how the social environment in the workplace, particularly organizational climate, related to these outcomes over time. Grounded in the JD-R model and the Social Cognitive Theory, this study addressed three research questions and tested one hypothesis regarding the moderating effect of positive organizational climate on the relationship between occupational stress and burnout. Below, we discuss our findings in relation to each question and highlight their theoretical and practical implications.

Our results revealed a significant decrease in teachers’ sense of personal accomplishment during the first lockdown (Spring 2020), compared to the pre-pandemic semester (Fall 2019) and the subsequent periods (Fall 2020, Spring 2021, and Summer 2021). The observed pattern is consistent with evidence suggesting that the perception of high job demands (which peaked at this time of data collection) and insufficient job and personal resources will primarily initiate a teacher’s professional efficacy crisis (Llorens et al., 2005). Not feeling competent to perform their teaching duties may, over time, negatively affect teacher distress, potentially setting in motion a broader process of burnout escalation (Edú-Valsania et al., 2022; Llorens et al., 2005). Although our design does not investigate this specific predictive analysis, our findings align with recent evidence showing increasing teacher burnout levels after the pandemic’s most acute phases (Gaspar et al., 2025; UNESCO, 2024). These results underscore the need to reinforce teachers’ personal accomplishment as a protective factor during times of disruption. To better support teachers in the new, unforeseen, and increasingly demanding teachers’ professional realities, policymakers, school leaders, and practitioners should act to equip teachers with personal and job resources that promote teachers’ perceived professional efficacy (UNESCO et al., 2022). In this regard, our qualitative findings on the main workplace stressors experienced during COVID-19 helped draw on the main challenges and resources to act upon.

Consistent with international evidence, our findings indicated that Portuguese elementary school teachers experienced a wide array of work-related challenges during the COVID-19 outbreak. Thematic content analysis revealed that elementary school teachers experienced significant strain arising from quantitative and qualitative workload, demanding interactions with students and parents, work reorganization, unfavorable work conditions and schedules, IT constraints, work-life conflict, and emotional demands. Notably, most of these demands (e.g., emotional demands, negative work-to-life spillover, challenges in work-life segmentation, excessive workload) mirror long-standing, well-documented stressors within the teaching profession (e.g., Kyriacou, 2001, 2011; Taris et al., 2017) suggesting that the pandemic functioned not as a generator of new stressors, but as an amplifier of pre-existing structural vulnerabilities. This distinction is critical, as it underscores the systemic nature of teacher occupational stress and suggests that mitigation strategies should extend beyond temporary pandemic-related measures.

Moreover, several of the most reported stressors (e.g., workload) have been consistently associated with impaired occupational health and well-being, lower job satisfaction, and increased turnover intentions among teachers (Collie & Mansfield, 2022; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2018). While their salience may have peaked during the lockdown, these work-related stressors appear to transcend the remote work context. They should therefore be addressed within broader, long-term occupational health frameworks for the education sector.

Nevertheless, the transition to home-office and remote work, as well as the unprepared transition to distance learning, may have exacerbated and helped explain certain challenges, particularly those linked to IT constraints, Work reorganization, and Work-life conflict. These findings align with other literature on the impacts of the pandemic, with teachers worldwide experiencing discomfort and unreadiness for accessing and using the necessary technological tools to teach remotely (UNESCO et al., 2022), which also impacted their ability to respond to professional responsibilities (Kraft et al., 2021). Our findings suggest that difficulties with digital tools, platforms, and connectivity were more frequent among older teachers, aligning with prior evidence on generational divides in digital literacy (Kraft et al., 2021). Moreover, younger and mid-career teachers reported more difficulties in reconciling work with other personal life responsibilities, suggesting that this demographic may be particularly burdened by competing professional and domestic roles during the pandemic (Kraft et al., 2021).

The (Lack of) Social support stood out as the only job resource cited recurrently as a source of teacher distress. Teachers described feeling isolated at work and missing social support from their colleagues and superiors. Importantly, references to (Lack of) Social support co-occurred with reports on the most frequent job demands previously depicted (e.g., workload, demanding interactions, work reorganization, inadequate work conditions), suggesting a compounding effect in which the absence of relational support might exacerbate the detrimental impact of job demands. These findings reinforce the importance of relational and contextual job resources, such as positive leadership practices, colleagues’ and supervisors’ social support, and adequate workplace policies (i.e., a positive organizational climate) (Collie et al., 2012), in mitigating teacher occupational stress and burnout. Conversely, the lack of these job resources may intensify the negative impact of job demands on teacher occupational health. These findings are consistent with evidence indicating that supportive school leadership plays an important role in countering the adverse effects of workplace pressure and work overload (De Clercq et al., 2022) and that having positive relationships with colleagues is associated with job satisfaction and decreased turnover intention (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011). Finally, following previous research on burnout consequences (e.g., Edú-Valsania et al., 2022), teachers also reported experiencing negative emotions and physical and mental health complaints as the primary health outcomes causing increased strain. Taken together, our qualitative findings underscore the need for targeted structural interventions aimed at reducing workload, improving communication structures, and fostering a positive workplace environment grounded in trust, cooperation, and institutional support to mitigate occupational stress and prevent teacher burnout.

Our three-wave longitudinal analysis offers further empirical support for the evolving dynamics of burnout indicators and the protective function of a positive organizational climate. Consistent with the JD-R model (Demerouti et al., 2001), occupational stress was found to significantly predict emotional exhaustion, which in turn predicted depersonalization, two of the core dimensions of burnout. However, personal accomplishment followed a distinct pattern: at T2, personal accomplishment was not significantly predicted by either emotional exhaustion or depersonalization, but instead positively predicted by organizational climate. Despite limitations related to cross-sectional data, these findings contribute to ongoing discussions in the burnout literature about the structural distinctiveness of personal accomplishment. Our results suggested that personal accomplishment may operate as a burnout dimension more responsive to job resources, particularly those of a relational and contextual nature (Bresó et al., 2007).

Moreover, longitudinal moderation analyses partially supported our hypothesis (H1), further sustaining these findings. Organizational climate moderated the relationship between occupational stress and teacher overall burnout and emotional exhaustion, such that a more positive organizational climate was associated with a reduction in the adverse effects of work-related stress on overall burnout and emotional exhaustion. No significant moderation effects were found for depersonalization or personal accomplishment, but a main positive effect of organizational climate on personal accomplishment was confirmed.

This pattern reinforces theoretical assumptions from the Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2001) and the Structural Theory (Edú-Valsania et al., 2022), which posit that burnout may emerge from a progressive erosion of professional efficacy and fulfillment at work. According to these frameworks, low personal accomplishment results as an initial reaction to distress when workers perceive a mismatch between professional demands and their individual or collective ability to meet them (Llorens et al., 2005). When the coping strategies employed are recurrently perceived as ineffective and feelings of low accomplishment at work intensify, emotional exhaustion may emerge, potentially evolving to depersonalization as a subsequent defensive coping mechanism, completing the three-dimensional syndrome of burnout (Manzano García & Campos, 2000).

These findings carry important implications. First, they underscore the need to prioritize the promotion of teachers’ professional efficacy as a central axis in occupational health promotion strategies to counteract burnout development. Second, our results support the JD-R model’s focus on the dual role of job demands and resources. They show that enhancing job resources, such as organizational climate, can play a pivotal role in promoting personal accomplishment and buffering overall burnout and emotional exhaustion. Finally, adding to prior literature, our findings provide empirical support for organizational-level interventions aimed at fostering a supportive, collaborative, and psychologically safe work environment (Brackett & Cipriano, 2020; Collie et al., 2012; Hascher & Waber, 2021; Trauernicht et al., 2025). In the current global context, marked by instability and unpredictability, the social environment of the workplace emerges as a crucial lever for protecting employee occupational health and well-being (UNESCO et al., 2022). As such, policy and practice in educational settings should move beyond individual resilience frameworks and prioritize systemic organizational changes that reinforce supportive organizational climates as a buffer against chronic work-related stress and burnout.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations

Our study is not without its limitations. It relied on a convenience, small, non-probabilistic, and geographically circumscribed sample. Our sample only included public schools. These sample characteristics limit representativeness and generalizability. While our study provides valuable insights into teachers’ experiences, acknowledging that Portuguese regulations apply nationwide, teachers in different geographic and socioeconomic regions may have had different experiences. Data were collected exclusively online, based on self-report questionnaires that required recall of past experiences, which may introduce bias. Repeated cross-sectional data on stress and burnout hinder analysis of changes over time. Hence, despite using a validation protocol, future research should resort to different data collection methods to further explore these variables and their associations.

5.2. Study Impact

Our study contributes to bridging a research gap by providing a multidimensional analysis of how Portuguese elementary school teachers navigated the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. While prior research has largely relied on cross-sectional or post-hoc data, our inclusion of pre-pandemic baseline data (Fall 2019) alongside longitudinal and qualitative data offers a unique opportunity to explore the evolution of teachers’ occupational stress and burnout across two academic years of unprecedented disruption.

One of the critical findings of our study lies in the supporting evidence of perceived personal accomplishment as a pivotal dimension in the teacher burnout development process. Instead of simply being a result of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, our data suggest that personal accomplishment may function as a distinct, resource-sensitive dimension of burnout, responsive to contextual factors such as organizational climate. This result advances theoretical frameworks and can guide prompt action to foster teacher occupational health and well-being. Strengthening teachers’ professional efficacy can serve as an effective intervention to mitigate the risk of burnout, improve job performance, and retention.

Additionally, our study revealed that social support and a positive work environment were critical job resources in mitigating the adverse effects of teacher work-related stress, acting against teacher burnout. The co-occurrence of insufficient social support with multiple job demands highlights the amplifying effect of resource deficits, suggesting that interventions must extend beyond individual resilience-building to encompass structural organizational changes. The moderating role of organizational climate further sustains these conclusions. Thus, embedding social support within the organizational framework is critical to reducing burnout and improving educational outcomes. This suggests that interventions aimed at fostering a positive organizational climate, through positive leadership practices, colleagues’ and supervisors’ social support, and workplace policies aligned with teachers’ needs, should be prioritized.

Taken together, our results yield actionable recommendations for policymakers, school leaders, and practitioners. Interventions should be designed not only to address acute stressors brought on by the pandemic, but also to mitigate persistent, pre-existing structural challenges in the teaching profession that were heightened by this disruption. Drawing on the main results from both the qualitative and longitudinal data, we advocate for multi-tiered strategies including: investing in innovative approaches that leverage technology to optimize work processes and resource allocation to reduce workload and administrative burden; promoting collaborative, open, and transparent communication structures, and peer-mentorship and social integration initiatives to enhance collegial and leadership support; and developing institution-wide policies that support teacher autonomy and professional development to meet the new and unforeseen job demands that are arising from societal and work-related changes. These measures should be tailored to the specific challenges faced by teachers in different contexts, ensuring that interventions not only ease stressors but also cultivate sustainable and supportive work environments.

While data collection was completed in 2021, the significance of our findings remains unchanged. Our study captures a pivotal moment in teachers’ occupational health during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the rapid changes in educational methods and demands caused by the pandemic have not only persisted but evolved. Hybrid teaching models, increasing digital integration, and heightened social, emotional and behavioral challenges are now embedded features of many schooling systems, continuing to exert pressure on teachers. As recent global evidence sustains, teacher work-related stress remains high, driven by persistent structural changes in education and broader societal disruptions. Therefore, understanding how organizational climate can mitigate burnout remains imperative for designing effective support mechanisms in the post-pandemic BANI world.

In sum, our findings offer conceptual and practical insights that extend beyond the temporal bounds of the pandemic and provide valuable evidence to inform policies and professional development strategies aimed at fostering resilient educational environments and to plan for future challenges in education. Nonetheless, our data specifically pertain to teachers’ experiences between Fall 2019 and Summer 2021. Hence, any application to the current situation should be contextualized by the changes that have occurred since, rather than assumed as directly generalizable.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Category system based on the Job Demands and Resources Model (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014), with extended summary of quotations. Total recording units = 293.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.O., M.S.R., A.M.V.-S. and A.M.-P.; methodology, S.O. and A.M.-P.; validation, S.O.; formal analysis, S.O.; investigation, S.O.; data curation, S.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.O.; writing—review and editing, S.O. and A.M.-P.; visualization, S.O.; supervision, M.S.R., A.M.V.-S. and A.M.-P.; project administration, S.O.; funding acquisition, S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, through research grants (S.O., grant number SFRH/BD/137845/2018 and 2023.08903.CEECIND), through the Research Center for Psychological Science of the Faculty of Psychology, University of Lisbon (CICPSI; UIDB/04527/2020 and UIDP/04527/2020), and the Business Research Unit—ISCTE, University Institute of Lisbon (UIDB/00315/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Deontology Committee of the Faculty of Psychology, University of Lisbon (Ethics approval Ata 06/2019, date of the approval: 21 February 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the revision of this paper, the authors used Grammarly (1.127.0.0) Word add-on to revise the writing and improve sentences for conciseness and readability. None of the original content was generated by AI-assisted technologies. The authors reviewed and edited the content as necessary and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BANI |

Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, and Incomprehensible |

| JD-R |

Job Demands and Resources |

References

- Alves, R., Lopes, T., & Precioso, J. (2020). Teachers’ well-being in times of Covid-19 pandemic: Factors that explain professional well-being. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 15, 203–217. [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. N., Peele, H., Daniels, M., Saybe, M., Whalen, K., Overstreet, S., & The New Orleans, T.-I. S. L. C. (2021). The experience of covid-19 and its impact on teachers’ mental health, coping, and teaching. School Psychology Review, 50(4), 491–504. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Bardin, L. (Translation: Reto, L. A., & Pinheiro, A.). (2000). Análise de conteúdo. Edições 70.

- Blaydes, M., Gearhart, C. A., McCarthy, C. J., & Weppner, C. H. (2024). A longitudinal qualitative exploration of teachers’ experiences of stress and well--being during COVID--19. Psychology in the Schools, 61(6), 2291–2314. [CrossRef]

- Brackett, M., & Cipriano, C. (2020, April). Teachers are anxious and overwhelmed: They need SEL now more than ever. EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2020-04-07-teachers-are-anxious-and-overwhelmed-they-need-sel-now-more-than-ever.

- Bresó, E., Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). In search of the “third dimension” of burnout: Efficacy or inefficacy? Applied Psychology, 56(3), 460–478. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H., Fan, Y., & Lau, H. (2023). An integrative review on job burnout among teachers in China: Implications for human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(3), 529–561. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd Ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J. (2021). COVID-19 and teachers’ somatic burden, stress, and emotional exhaustion: Examining the role of principal leadership and workplace buoyancy. AERA Open, 7, 2332858420986187. [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., & Mansfield, C. F. (2022). Teacher and school stress profiles: A multilevel examination and associations with work-related outcomes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 116, 103759. [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1189–1204. [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, R., & Peters, G.-J. Y. (2017). Scale quality: Alpha is an inadequate estimate and factor-analytic evidence is needed first of all. Health Psychology Review, 11(3), 242–247. [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, M., Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2022). Profiles of teachers’ striving and wellbeing: Evolution and relations with context factors, retention, and professional engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(3), 637–655. [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [CrossRef]

- Edú-Valsania, S., Laguía, A., & Moriano, J. A. (2022). Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1780. [CrossRef]

- García-Arroyo, J. A., & Osca Segovia, A. (2018). Effect sizes and cut-off points: A meta-analytical review of burnout in Latin American countries. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 23(9), 1079–1093. [CrossRef]

- García-Arroyo, J. A., Osca Segovia, A., & Peiró, J. M. (2019). Meta-analytical review of teacher burnout across 36 societies: The role of national learning assessments and gender egalitarianism. Psychology & Health, 34(6), 733–753. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T., Jesus, S., Xavier, M., Dias, M. C., Machado, M. do C., Correia, M. F., Pais Ribeiro, J. L., Areosa, J., Canhão, H., Guedes, F. B., Cerqueira, A., & Gaspar de Matos, M. (2023). Ecossistemas de ambientes de trabalho saudáveis: relatório 2022. Laboratório Português de Ambientes de Trabalho Saudáveis. https://53237d59-ec33-49aa-bc7f-86826566ffa8.filesusr.com/ugd/645903_753cc0a8fa0c49a983d63195d9e48323.pdf.

- Gaspar, T., Telo, E., Jesus, S., Xavier, M., Dias, M. C., Maria do Céu Machado, Gaspar de Matos, M., Correia, M. F., Pais Ribeiro, J. L., Areosa, J., Canhão, H., Guedes, F. B., Cerqueira, A., & Sousa, B. (2025). Laboratório Português de ambientes de trabalho saudável: Evolução da saúde ocupacional 2021 a 2024. LABPATS. https://53237d59-ec33-49aa-bc7f-86826566ffa8.filesusr.com/ugd/645903_f5066c993e2a459ea9f73858a856d916.pdf.

- Gavin, B., Lyne, J., & McNicholas, F. (2021). The global impact on mental health almost 2 years into the COVID-19 pandemic. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(4), 243–246. [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, R. (1998). The importance of schools and teachers in child welfare. Child & Family Social Work, 3(1), 13–25. [CrossRef]

- Gizzi, M. C., & Rädiker, S. (Eds). (2021). The practice of qualitative data analysis. MAXQDA Press. [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T., & Waber, J. (2021). Teacher well-being: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educational Research Review, 34, 100411. [CrossRef]

- Kim, L. E., & Asbury, K. (2020). ‘Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: The impact of COVID--19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), 1062–1083. [CrossRef]

- Kim, L. E., Dundas, S., & Asbury, K. (2024). ‘I think it’s been difficult for the ones that haven’t got as many resources in their homes’: Teacher concerns about the impact of COVID-19 on pupil learning and wellbeing. Teachers and Teaching, 30(7–8), 884–899. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th Ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Koller, M. (2016). Robustlmm: An R package for robust estimation of linear mixed-effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 75(6), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Kotowski, S. E., Davis, K. G., & Barratt, C. L. (2022). Teachers feeling the burden of COVID-19: Impact on well-being, stress, and burnout. Work, 71(2), 407–415. [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M. A., Simon, N. S., & Lyon, M. A. (2021). Sustaining a sense of success: The protective role of teacher working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 14(4), 727–769. [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, C. (2001). Teacher stress: Directions for future research. Educational Review, 53(1), 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, C. (2011). Teacher stress: From prevalence to resilience. In J. Langan-Fox & C. Cooper, Handbook of Stress in the Occupations (pp. 161–173). Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, C., & Sutcliffe, J. (1978). Teacher stress: Prevalence, sources, and symptoms. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 48(2), 159–167. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Llorens, S., García-Renedo, M., & Salanova, M. (2005). Burnout como consecuencia de una crisis de eficacia: Un estudio longitudinal en profesores de secundaria1 Burnout as a result of efficacy crisis: A longitudinal study in secondary school teachers. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 21(1–2), 55–70.

- MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2020). Language teachers’ coping strategies during the Covid-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System, 94, 102352. [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to quit. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103425. [CrossRef]

- Maechler, M., Todorov, V., Ruckstuhl, A., Salibian-Barrera, M., Koller, M., & Conceicao, E. L. T. (2024). Robustbase: Basic robust statistics (Version 0.99-4-1) [Data set]. [CrossRef]

- Magnani, G., & Gioia, D. (2023). Using the Gioia Methodology in international business and entrepreneurship research. International Business Review, 32(2), 102097. [CrossRef]

- Mair, P., & Wilcox, R. (2020). Robust statistical methods in R using the WRS2 package. Behavior Research Methods, 52(2), 464–488. [CrossRef]

- Manzano García, G., & Campos, F. R. (2000). Enfermería hospitalaria y síndrome de burnout. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16(2), 197–213.

- Marques-Pinto, A., Lima, M. L., & Lopes da Silva, A. (2005). Fuentes de estrés, burnout y estrategias de coping en profesores portugueses. Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones, 21(1–2), 125–143.

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Marín, J., Prado-Abril, J., Piva Demarzo, M. M., Gascon, S., & García-Campayo, J. (2014). Coping with stress and types of burnout: Explanatory power of different coping strategies. PLoS ONE, 9(2), e89090. [CrossRef]

- Mota, A. I., Lopes, J., & Oliveira, C. (2021). Burnout in Portuguese teachers: A systematic review. European Journal of Educational Research, 2(10), 693–703. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2020). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S., Cardoso, A., Martins, M. O., Roberto, M. S., Veiga-Simão, A. M., & Marques-Pinto, A. (2025). Bridging the gap in teacher SEL training: Designing and piloting an online SEL intervention with and for teachers. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy, 5, 100118. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S., Roberto, M. S., Marques-Pinto, A., & Veiga-Simão, A. M. (2023). Elementary school climate through teachers’ eyes: Portuguese adaptation of the Organizational Climate Description Questionnaire Revised for Elementary schools. Current Psychology, 42(28), 24312–24325. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S., Roberto, M. S., Veiga-Simão, A. M., & Marques-Pinto, A. (2022). Effects of the A+ intervention on elementary-school teachers’ social and emotional competence and occupational health. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 957249. [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, A., Ramos, D., Santos, G., Rodrigues, M. A., & Doiro, M. (2023). Psychosocial risks in teachers from Portugal and England on the way to society 5.0. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(14), 6347. [CrossRef]

- Pressley, T. (2021). Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educational Researcher, 50(5), 325–327. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version R 4.2.0) [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project. org/.

- Ryan, R.M. , & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi--sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. F. Bauer & O. Hämmig (Eds), Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health (pp. 43–68). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1029–1038. [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017). Dimensions of teacher burnout: Relations with potential stressors at school. Social Psychology of Education, 20(4), 775–790. [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2018). Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Social Psychology of Education, 21(5), 1251–1275. [CrossRef]

- Small Business Prices. (2022). The European countries with the highest risk of burnout. https://smallbusinessprices.co.uk/european-employee-burnout/.

- Smith, A. J., Johnson, A. L., Miyazaki, Y., Weber, M. C., Wright, H., Griffin, B. J., Holmes, G. A., & Jones, R. T. (2025). Risk for mental health distress among PreK--12 teachers during the COVID--19 pandemic. Psychology in the Schools, 62(5), 1622–1633. [CrossRef]

- Sokal, L. J., Trudel, L. G. E., & Babb, J. C. (2020). Supporting teachers in times of change: The job demands-resources model and teacher burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Contemporary Education, 3(2), 67. [CrossRef]

- Taris, T. W., Leisink, P. L. M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Applying occupational health theories to educator stress: Contribution of the job demands-resources model. In T. M. McIntyre, S. E. McIntyre, & D. J. Francis (Eds), Educator stress. Aligning perspectives on health, safety and well-being (pp. 237–259). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Trauernicht, M., Anders, Y., Oppermann, E., & Klusmann, U. (2025). Emotional exhaustion in German preschool teachers: The role of personal, structural, and social conditions at the workplace. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 39(1), 78–97. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2024). Global report on teachers: Addressing teacher shortages and transforming the profession. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, UNICEF, The World Bank, & OECD. (2022). From learning recovery to education transformation insights and reflections from the 4th survey of national education responses to COVID-19 school closures. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Varela, R., Santa, R. della, Laher, R., Silveira, H., & Duarte Rolo. (2022). Do entusiasmo ao burnout?: A situação social e laboral dos professores em Portugal hoje (1st edn). Editora Húmus.

- Varela, R., Santa, R. della, Silveira, H., Matos, C. de, Rolo, D., Areosa, J., & Leher, R. (2018). Inquérito nacional sobre as condições de vida e trabalho na educação em portugal (INCVTE). FCSH. https://www.spn.pt/Media/Default/Info/22000/700/0/0/Relat%C3%B3rio%20-%20Estudo%20sobre%20o%20desgaste%20profissional%20(2018).pdf.

- Viac, C., & Fraser, P. (2020). Teachers’ well-being: A framework for data collection and analysis. OECD Education Working Papers (Vol. 213). [CrossRef]

- Von Der Embse, N., & Mankin, A. (2021). Changes in teacher stress and wellbeing throughout the academic year. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 37(2), 165–184. [CrossRef]

- Von Der Embse, N., Ryan, S. V., Gibbs, T., & Mankin, A. (2019). Teacher stress interventions: A systematic review. Psychology in the Schools, 56(8), 1328–1343. [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Dollard, M. F., Demerouti, E., Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Schreurs, P. J. G. (2007). When do job demands particularly predict burnout?: The moderating role of job resources. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(8), 766–786. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).