The present discussion is structured in a first section, which analyzes the main findings of this narrative review, and a second section devoted to the clinical relevance and practical applications of this research, with the aim of providing information that addresses the previously identified research gaps and contributes to more comprehensive social and health care for women with endometriosis.

4.1. Adipose Tissue Dysregulation in Endometriosis: Inflammatory and Metabolic Insights within a Biopsychosocial–Intersectional Framework

Differential inflammatory responses between visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues in women with endometriosis has been reported. In line with the patterns described in the results section, clear depot-specific differences were observed. On purpose, IL-6 protein levels were markedly elevated in visceral adipose tissue (VAT), whereas subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) showed only a mild, non-significant increase and a significant reduction in IL-6 mRNA expression. MCP-1 was significantly upregulated in VAT, reflecting enhanced macrophage recruitment, while SAT remained unchanged. CD206, a marker of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, was markedly decreased in VAT, indicating a shift toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype, with only a non-significant downward trend in SAT. Galectin-3 expression tended to increase in VAT but showed no variation in SAT. These findings highlight tissue-specific inflammatory regulation, with VAT exhibiting a stronger pro-inflammatory signature than SAT in the context of endometriosis, supporting the notion that VAT browning and inflammation contribute to adipose tissue dysfunction and altered lipid metabolism [

8,

15,

16].

These depot-specific inflammatory alterations further indicate that inflammation in endometriosis is predominantly localized within VAT rather than being uniformly distributed across adipose depots. The distinct upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduction of anti-inflammatory markers in VAT suggest selective activation of immune and macrophage-related pathways that may contribute to local tissue dysfunction. Given that VAT is metabolically and immunologically more active than SAT, these findings reinforce its central role in shaping the systemic inflammatory milieu associated with endometriosis. This pattern also aligns with the idea that VAT inflammation might act as a potential driver of systemic inflammatory signaling and interact with reproductive and metabolic pathways, thereby contributing to disease progression [

8]. Its anatomical proximity to endometriotic lesions may further amplify these inflammatory processes. Understanding these depot-specific alterations is clinically relevant, as it highlights VAT as a potential therapeutic target within metabolic and anti-inflammatory treatment strategies [

8].

From a broader pathophysiological perspective, adipose tissue inflammation may contribute to the progression of endometriosis through multiple interconnected mechanisms. The secretion of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 sustain chronic inflammation and promote tissue remodeling, while increased VEGF supports angiogenesis and lesion survival. Accumulation of M1 macrophages amplifies inflammatory signaling, creating a persistent feedback loop that maintains lesion activity. FABP4 overexpression appears to link lipid metabolism to inflammatory and angiogenic pathways, reinforcing the metabolic–immune connection. Additionally, reductions in adipocyte size reflect underlying adipose tissue dysfunction and a shift toward enhanced browning and thermogenic activity [

8]. These processes establish a self-sustaining inflammatory network between endometriotic lesions and adjacent adipose depots, contributing to fibrosis, angiogenesis, and chronic progression [

9,

16]. These observations reinforce the bidirectional interaction between endometriotic lesions and adipose tissue, where metabolic and inflammatory signaling mutually amplify one another [

16].

Consistent with these mechanisms, inflammation within adipose tissue adjacent to endometriotic lesions contributes to fibrosis, angiogenesis, and the establishment of a persistent pro-inflammatory microenvironment. Elevated IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8—detected both in the peritoneal cavity and in perilesional adipose tissue—serve as key mediators of chronic inflammation. IL-6 and TNF-α support immune cell recruitment and angiogenic signaling, while IL-1β and IL-8 further amplify inflammatory cascades and vascular remodeling. This sustained cytokine activity reinforces local-to-systemic immunometabolic interactions, promoting the maintenance and progression of endometriotic lesions [

9,

16].

In parallel, metabolic markers of visceral adiposity also appear relevant. The lipid accumulation product (LAP) emerges as a significant indicator in endometriosis, with women in the highest quartile showing approximately 56% higher odds of developing the condition compared with those in the lowest quartile. As an index integrating waist circumference and triglyceride levels, LAP better reflects visceral fat accumulation than BMI. Because visceral adiposity is closely tied to inflammation, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress, LAP may function as a proxy for metabolic dysfunction linked to endometriosis. Its association is particularly pronounced among women aged ≥35 years, those with pregnancy history, and individuals undergoing hormonal therapy. Clinically, LAP represents a simple, non-invasive tool that may facilitate early identification of women at increased risk [

6,

17]. Given its associations with VAT-related inflammation, LAP—and to a lesser extent VAI—may support metabolic screening strategies to identify patients with adiposity-driven inflammatory risk profiles [

6,

17].

Regarding adiposity patterns, epidemiological studies consistently report an inverse association between endometriosis and BMI, with affected women tending to have lower BMI and reduced adipose mass (especially below the waist). This lean phenotype may influence estrogen regulation, which is highly relevant given the estrogen-dependent nature of the disease [

14]. Several mechanisms have been proposed: obesity-related anovulation and oligomenorrhea may reduce retrograde menstruation; chronic pain and emotional distress may reduce appetite; and adipokines may influence immune regulation, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Importantly, associations between fat distribution and endometriosis risk appear age-dependent: inverse relationships between waist-to-hip and waist-to-thigh ratios and endometriosis risk are seen in women under 30 but not in older women. In general, these findings emphasize a complex interplay among fat distribution, estrogen levels, and inflammatory pathways; as well as the need to take sociodemographic factors into consideration [

14,

16,

17].

These observations highlight the need to further examine the temporal and anatomical dimensions of the adiposity–endometriosis link. Future research should evaluate adiposity measures before diagnosis, and ideally before disease onset, to clarify potential causal pathways. Anatomical distinctions between VAT and SAT might be particularly relevant for understanding metabolic and inflammatory interactions underlying endometriosis. Such insights may support earlier detection and identify metabolic phenotypes associated with the disease [

12]. In the same line, lifestyle interventions provide an additional avenue for prevention and management. For instance, dietary modifications that reduce saturated fat intake may improve lipid metabolism and decrease systemic inflammation; weight management may reduce visceral adiposity and pro-inflammatory cytokine release; and regular physical activity supports improved insulin sensitivity and immune modulation. These strategies target modifiable risk factors in a non-invasive manner and promote metabolic and reproductive health [

6]. Further research is needed to explore the systemic impact of adipose tissue dysfunction in endometriosis.

Despite the relevance of these biological and metabolic interactions, several methodological limitations characterize the reviewed literature. Many studies relied on small sample sizes, used cross-sectional designs, which do not allow for causal inferences; or lacked pre-diagnostic adiposity data. In addition, measures of adiposity varied widely—ranging from adipose tissue biopsies to anthropometrics, LAP, VAI, or imaging—hindering comparability. The scarcity of longitudinal assessments and inconsistent characterization of inflammatory markers further complicate interpretation. These methodological constraints underline the need for more robust, standardized, and temporally sensitive study designs.

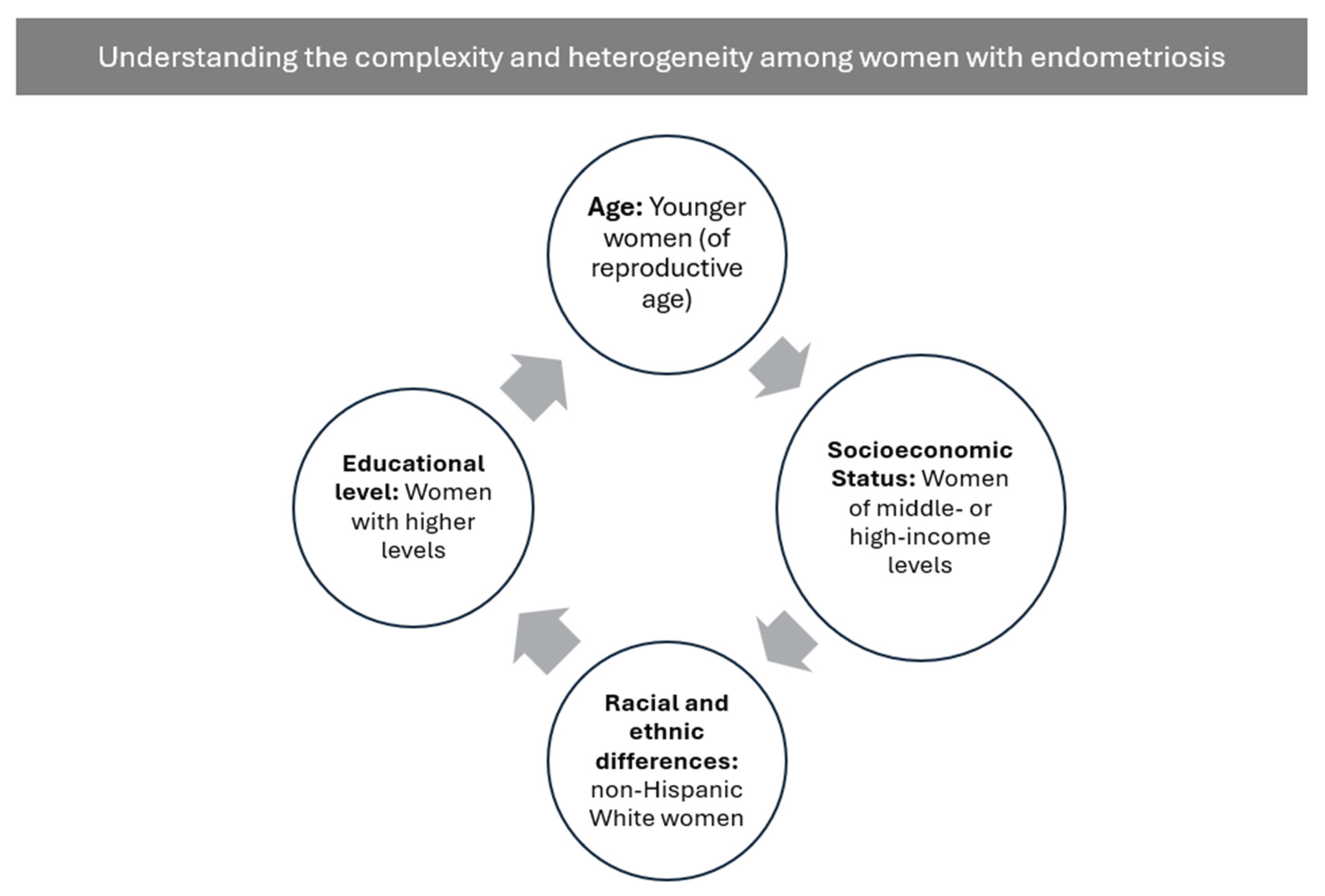

To sum up, the present synthesis also points up the role of sociodemographic factors in shaping the adiposity–endometriosis relationship. Differences related to age, race or ethnicity, educational attainment, and socioeconomic status do exist, but remain highly fragmented across the literature. Studies vary widely in the variables included, the analytical depth applied, and the theoretical frameworks used. As a result, sociodemographic determinants are rarely integrated into biological models despite their potential relevance for variability in symptom burden, inflammatory profiles, and disease severity [

1,

12,

13,

14]. This gap highlights an opportunity for future research. Incorporating biopsychosocial and intersectional approaches could clarify how structural conditions, lived experiences, and social determinants interact with adiposity-related mechanisms in women with endometriosis.

Methodologically, inconsistent measurement and limited interrogation of sociodemographic variables hinder the ability to distinguish biological heterogeneity from variability driven by differential exposure to structural conditions. Many studies control for—but do not examine—factors such as income, education, race or ethnicity, or reproductive history, thereby constraining their explanatory value. Inconsistencies across studies also limit comparability and impede the development of integrative models capable of capturing the complex interactions among metabolic dysfunction, hormonal regulation, and social context. Advancing this field requires systematic and theoretically informed incorporation of sociodemographic indicators, including intersectional frameworks that recognize how multiple social positions jointly shape biological vulnerability, symptom trajectories, and access to care.

In sum, the evidence reviewed draw attention to the relationship between adiposity and endometriosis is shaped by a dynamic interplay of biological, metabolic, inflammatory, and sociodemographic factors. Depot-specific immune activation, alterations in adipocyte function, and visceral adiposity–related metabolic dysregulation converge with patterns of differential risk linked to age, fat distribution, and lifestyle determinants. At the same time, sociodemographic disparities— fragmented across existing studies and rarely incorporated into disease models —suggest that biological vulnerability cannot be fully understood without considering structural conditions, access to care, and lived experiences that influence diagnosis, symptom trajectories, and disease severity. Integrating these dimensions within a unified biopsychosocial and intersectional framework may therefore offer a more comprehensive understanding of endometriosis pathophysiology and clinical presentation, improve the identification of metabolic and inflammatory phenotypes, and guide more equitable, personalized, and contextually informed prevention and treatment strategies.

4.2. Clinical Relevance and Therapeutic Implications

This narrative review has provided an opportunity to examine several factors that directly influence clinical practice due to their relevance for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis, as well as their potential to improve the quality of life of affected women.

A central consideration is that VAT plays a key role in the progression of endometriosis, owing to its pronounced inflammatory and metabolic activity. This observation suggests that therapeutic strategies aimed at reducing inflammation and improving VAT metabolic function might help mitigate symptoms and complement standard treatments without compromising reproductive objectives [

8].

In addition, the potential use of metabolic indices as clinical tools merits attention. Indicators such as the Lipid Accumulation Product (LAP) and the Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) have been proposed as valuable metrics for identifying inflammatory risk profiles associated with visceral adiposity. These indices may facilitate the early identification of women at increased risk of metabolic dysfunction and comorbidities linked to endometriosis. Adapting therapeutic strategies to each patient’s metabolic phenotype (e.g., elevated VAT activity or high LAP levels) and social context may further enhance the precision and clinical relevance of treatment decisions, thereby supporting more inclusive and individualized care [

6,

11].

Given the considerable heterogeneity in disease presentation, it is also essential to advance diagnostic and therapeutic approaches that are as personalized as possible and responsive to the specific clinical circumstances and needs of each woman.

The expansion of programs and interventions that promote lifestyle modification is equally important. Although still an emerging field of study, dietary changes, regular physical activity, and stress-reduction practices—such as mindfulness—may contribute to symptom management and improve general well-being. These psychological interventions can also help address modifiable risk factors and promote both metabolic and reproductive health [

1,

6].

Furthermore, additional longitudinal and multidisciplinary research is required to more fully elucidate the interactions between metabolic dysfunction, hormonal regulation, and psychosocial factors in endometriosis. Such work may contribute to the development of more effective prevention and treatment strategies. The specific contexts and needs of different countries should also be considered, as these may influence access to diagnostic services and treatment options. In fact, in many regions, access to early diagnosis and effective care remains limited, and it is therefore crucial to examine these realities as well [

1].

There is also a critical need to integrate biopsychosocial and intersectional perspectives into research, diagnosis, and clinical management of endometriosis. Sociodemographic factors—such as age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and socioeconomic status—should be systematically considered during clinical assessment, as they may influence risk profiles and contribute support more equitable and individualized care [

18,

19]. It is also essential to examine the health disparities experienced by women with endometriosis, including those arising from gender-based inequities and overlapping forms of discrimination. For example, the needs of a woman with endometriosis who has not experienced any form of victimization differ greatly from those of a woman who also faces discrimination on the basis of race, gender, and/or age. Such analyses promote more person-centered care and a more nuanced understanding of each clinical scenario. This approach is consistent with key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, SDG 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls), and SDG 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries.

In this context, sexual education plays a crucial role in enabling women to better understand their bodies and the pain associated with endometriosis, challenging the common misconception that menstrual or pelvic pain is “normal.” Sexual education also improves access to healthcare and may facilitate earlier diagnosis, which is crucial for improving prognosis. As previously noted, educational attainment is an important factor in endometriosis [

6,

12,

20]. Women with higher levels of education tend to have better employment opportunities, higher income, and greater knowledge of healthcare systems, which may enable earlier access to care and timelier diagnosis and treatment [

20]. Although no definitive preventive strategies exist for endometriosis, improving awareness of the condition—along with timely diagnosis and early treatment—may help slow or interrupt its natural progression, reduce long-term symptoms, and, in some cases, reduce the likelihood of central nervous system sensitization to [

1].

All these recommendations for clinical practice reinforce the need for a multidisciplinary approach that allows patients to benefit from the expertise of diverse professionals. Furthermore, multidisciplinary teams with specialists across health and social care disciplines are better equipped to implement comprehensive biopsychosocial models and intersectional frameworks in the assessment and management of women with endometriosis. Ongoing training and professional development regarding chronic pain—particularly endometriosis—and its biopsychosocial and intersectional management are essential for healthcare and social care providers.