Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

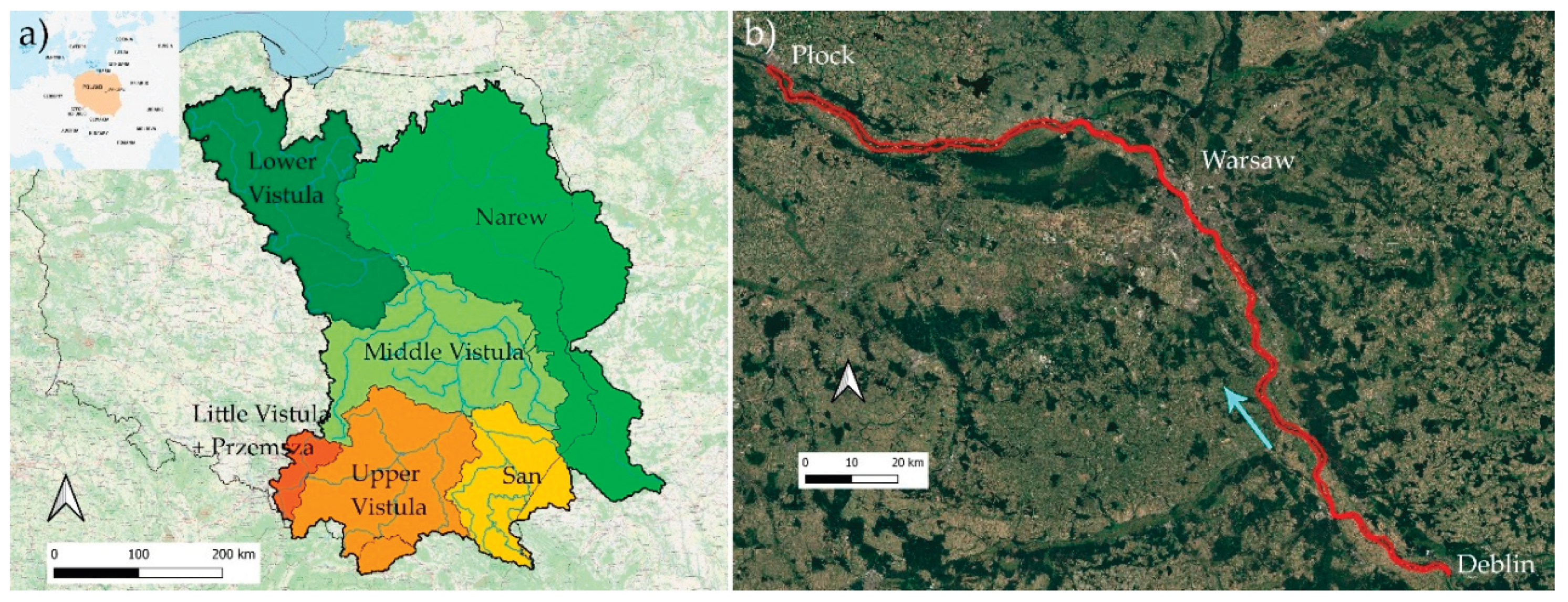

2.1. Study Area

2.2. River Morphology

2.3. Hydrological Data

2.4. Satellite Data

3. Results

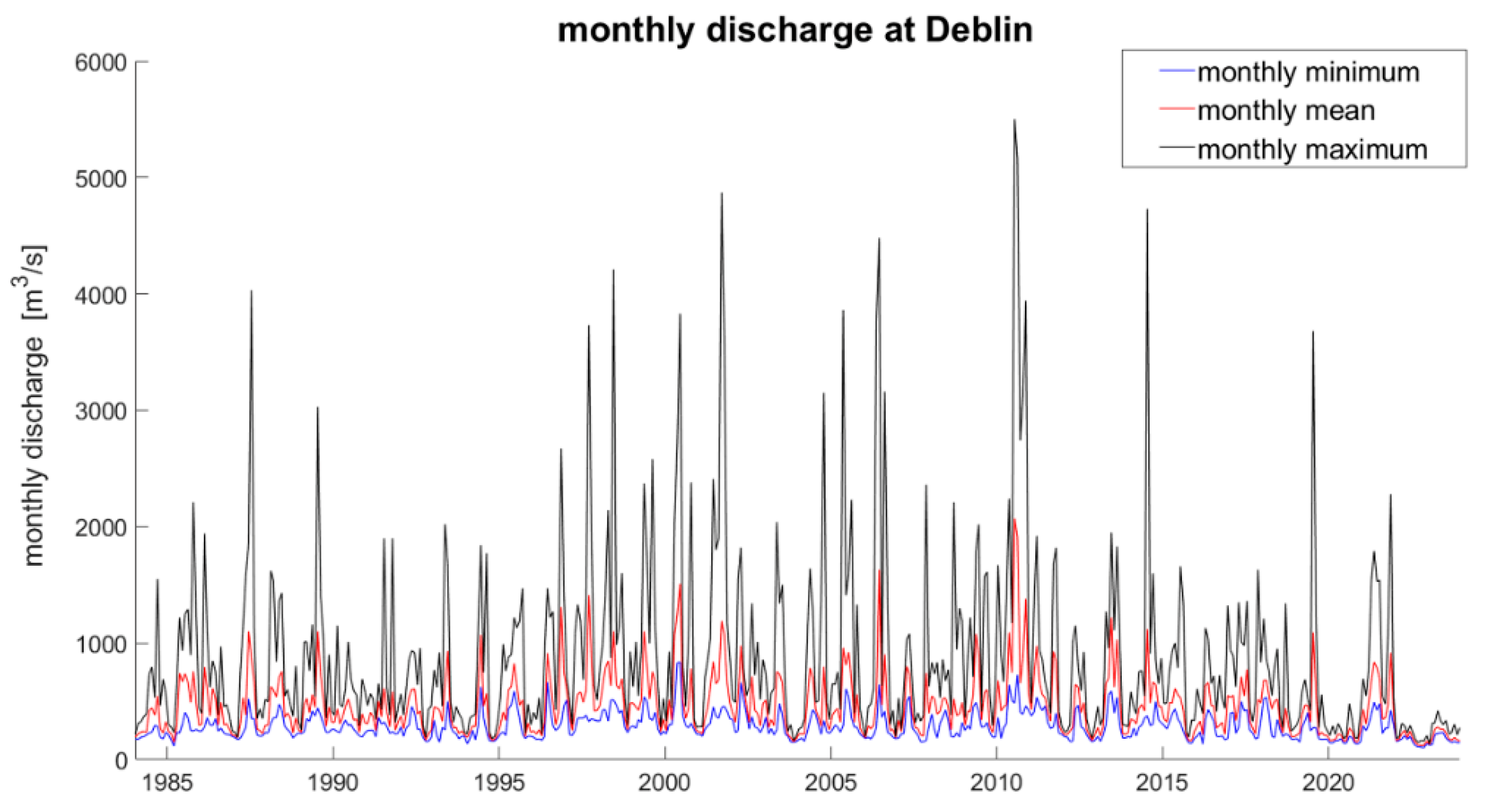

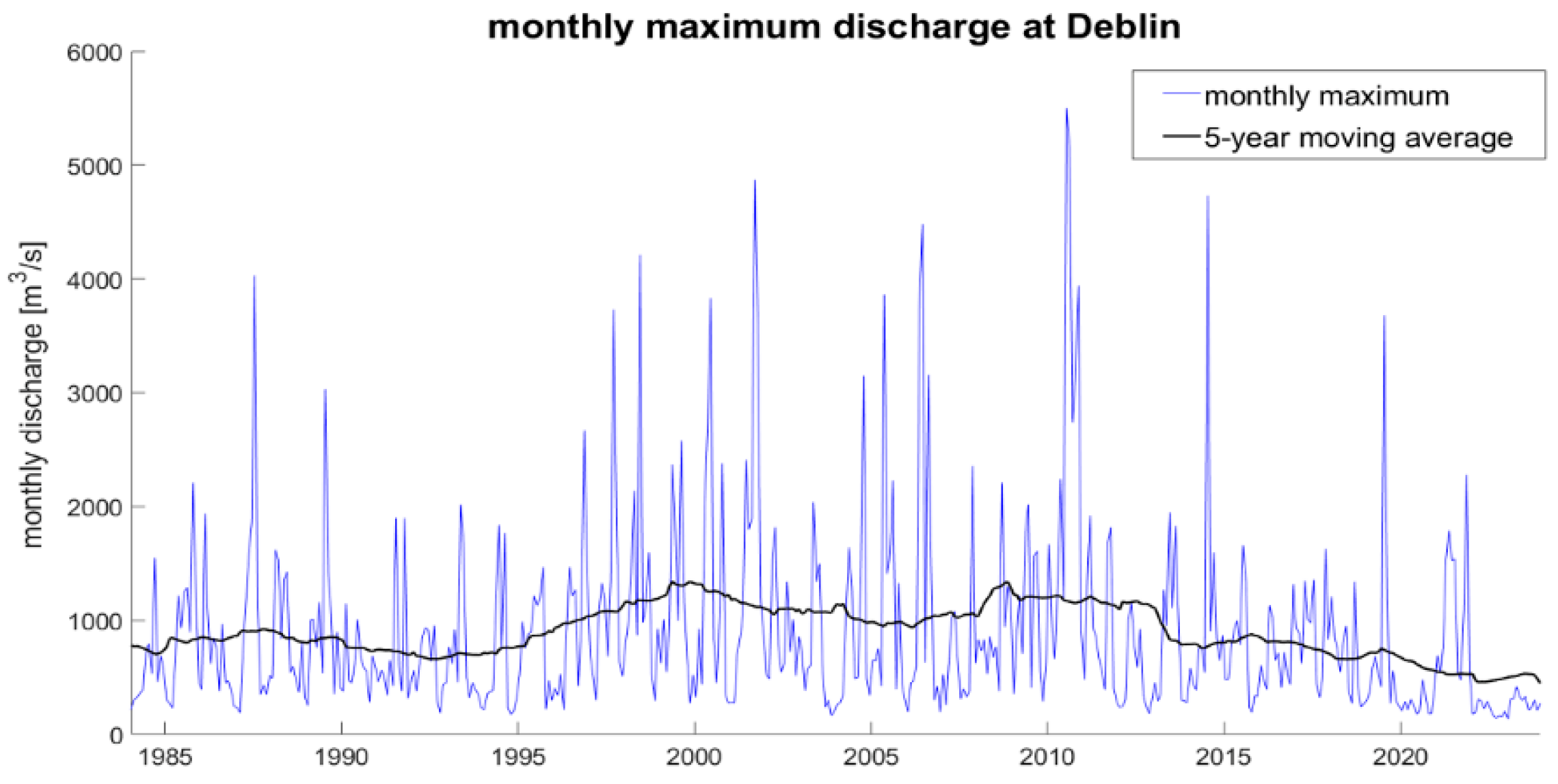

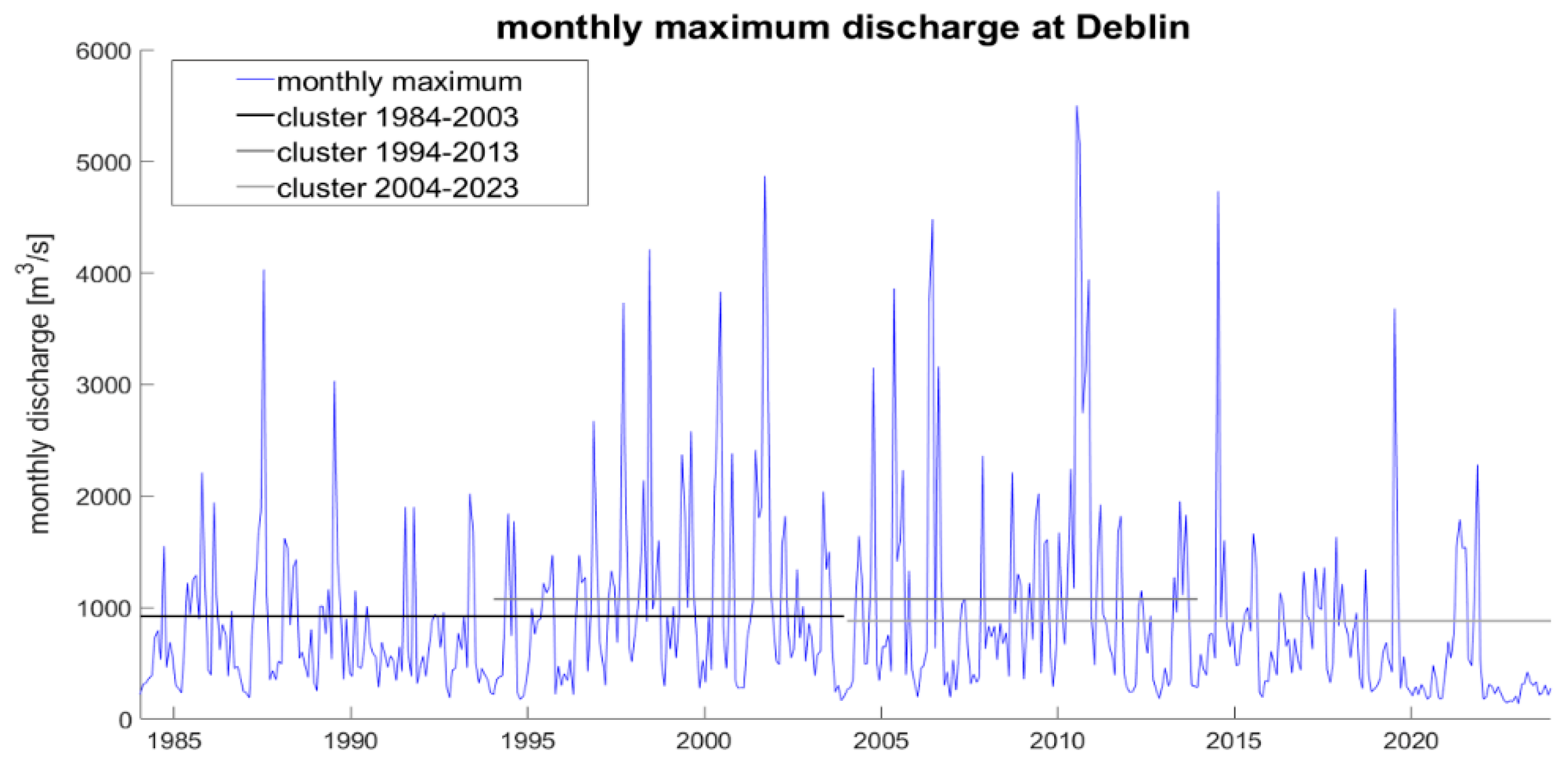

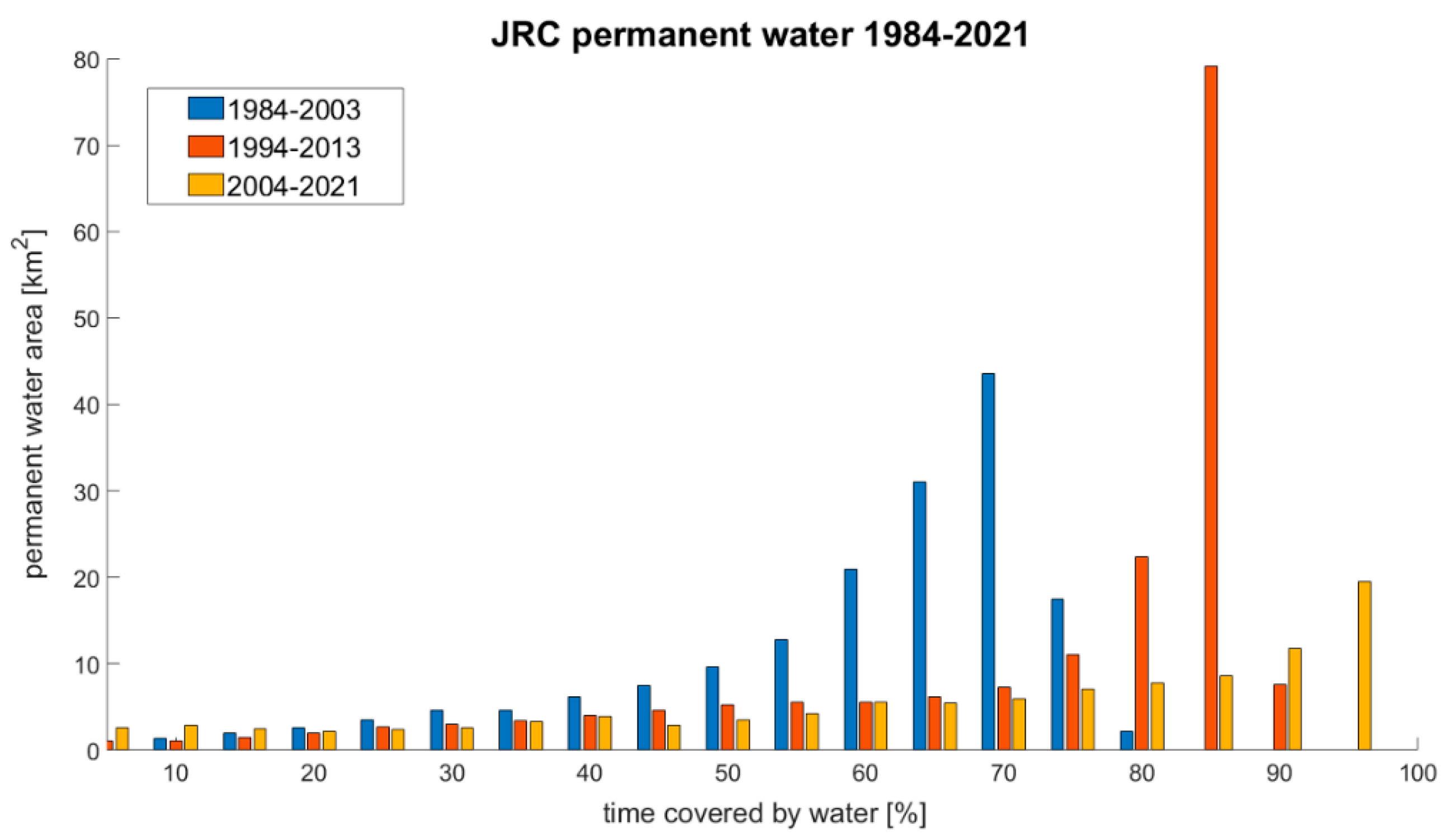

3.1. Hydrological Variability

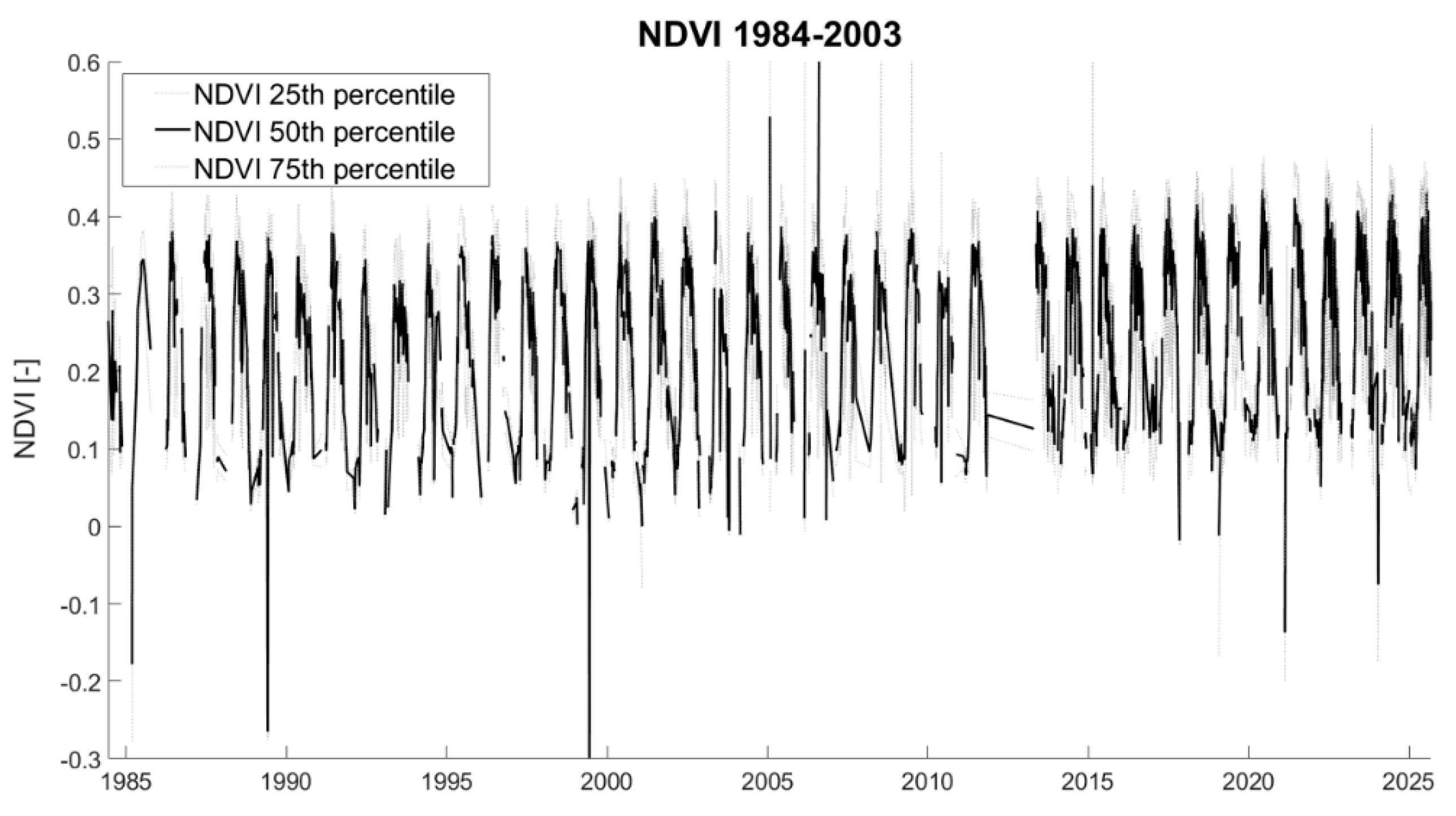

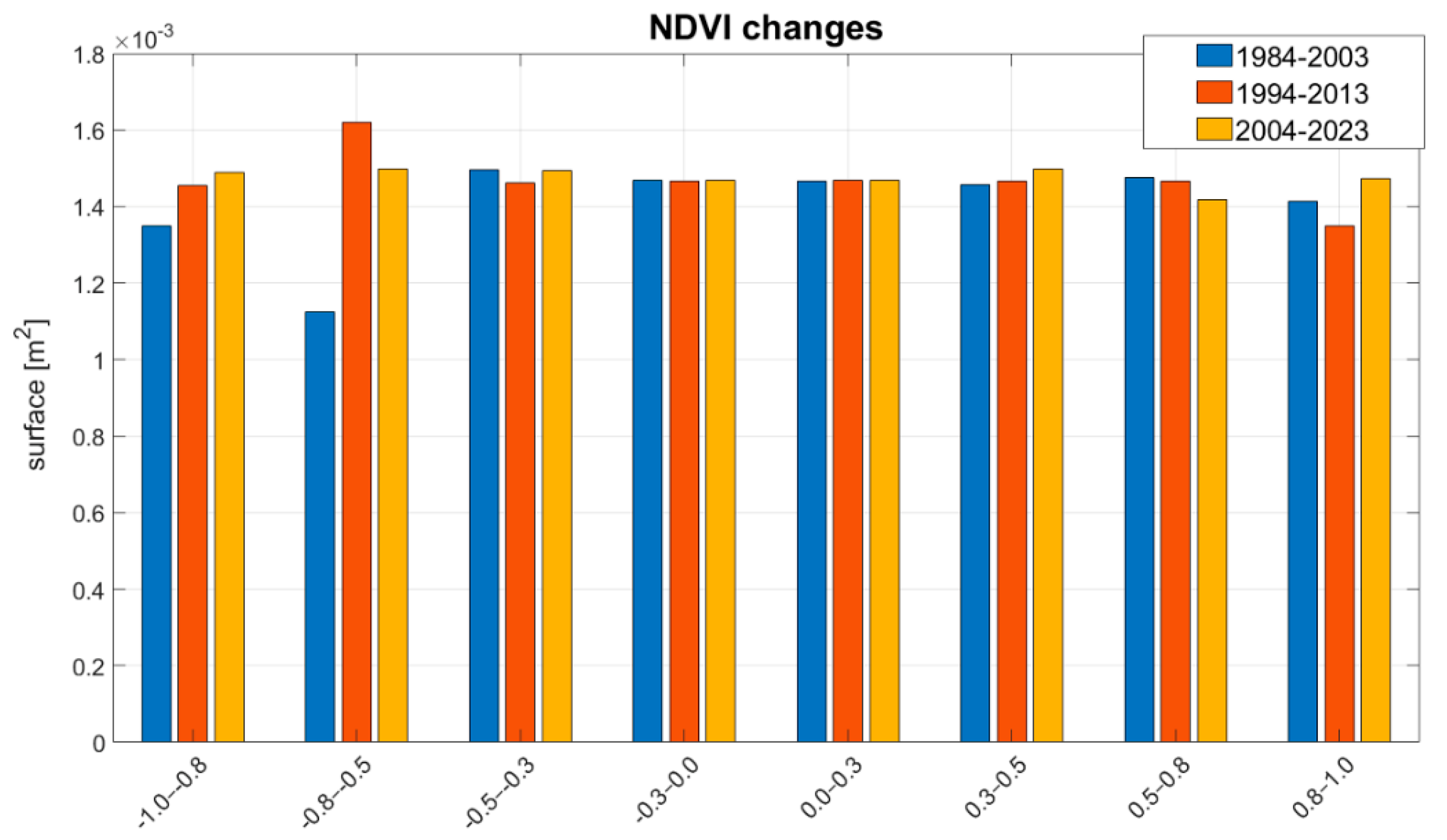

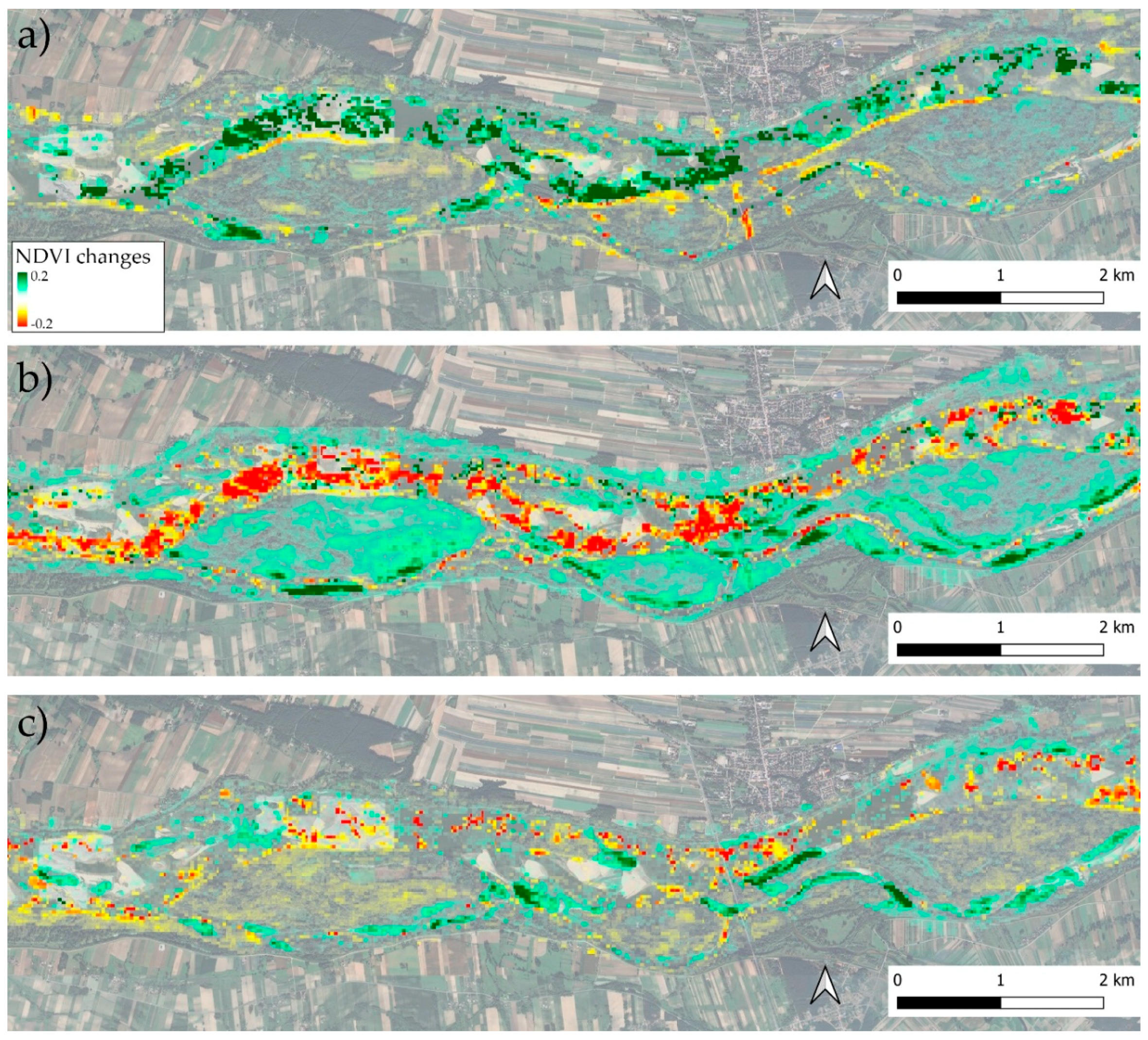

3.2. Vegetational Dynamics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leopold, L.B.; Maddock, T. The Hydraulic Geometry of Stream Channels and Some Physiographic Implications.; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalin, M.S. (1992). River Mechanics. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Slater, L.J.; Khouakhi, A.; Wilby, R.L. River channel conveyance capacity adjusts to modes of climate variability. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corenblit, D.; Tabacchi, E.; Steiger, J.; Gurnell, A.M. Reciprocal interactions and adjustments between fluvial landforms and vegetation dynamics in river corridors: A review of complementary approaches. Earth-Science Rev. 2007, 84, 56–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A.M.; Bertoldi, W.; Corenblit, D. Changing river channels: The roles of hydrological processes, plants and pioneer fluvial landforms in humid temperate, mixed load, gravel bed rivers. Earth-Science Rev. 2012, 111, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponi, F.; Vetsch, D.F.; Vanzo, D. BASEveg: A python package to model riparian vegetation dynamics coupled with river morphodynamics. SoftwareX 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Baldassarre, G.; Kooy, M.; Kemerink, J.S.; Brandimarte, L. Towards understanding the dynamic behaviour of floodplains as human-water systems. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 3235–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaß, A.-L.; Schüttrumpf, H.; Lehmkuhl, F. Human impact on fluvial systems in Europe with special regard to today’s river restorations. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balke, T.; Nilsson, C. Increasing Synchrony of Annual River-Flood Peaks and Growing Season in Europe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 10446–10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.M.; Rood, S.B. Streamflow requirements for cottonwood seedling recruitment—An integrative model. Wetlands 1998, 18, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balke, T.; Herman, P.M.J.; Bouma, T.J. Critical transitions in disturbance-driven ecosystems: identifying Windows of Opportunity for recovery. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, H.; Hou, L.; Wang, J.; Dong, X.; Han, S. Flood changed the community composition and increased the importance of stochastic process of vegetation and seed bank in a riparian ecosystem of the Yellow River. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nones, M. Satellite-Based Monitoring of Drought at the Watershed Scale. In Advances in Hydraulic Research, GeoPlanet: Earth and Planetary Sciences: 281-291. Eds Springer Nature Switzerland. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.M.S.; Yeşilköy, S.; Baydaroğlu, Ö.; Yıldırım, E.; Demir, I. State-level multidimensional agricultural drought susceptibility and risk assessment for agriculturally prominent areas. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2024, 23, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, V.; Nones, M. Assessment of meteorological, hydrological and groundwater drought in the Konya closed basin, Türkiye. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briffa, K.R.; Jones, P.D.; Hulme, M. Summer moisture variability across Europe, 1892–1991: An analysis based on the palmer drought severity index. Int. J. Clim. 1994, 14, 475–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljansek, K.; Marín Ferrer, M.; De Groeve, T.; Clarck, I. (2017). Science for disaster risk management 2017: knowing better and losing less. Eds. ETH Zürich, Switzerland.

- Spinoni, J.; Naumann, G.; Vogt, J.V. Pan-European seasonal trends and recent changes of drought frequency and severity. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2017, 148, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somorowska, U. Changes in Drought Conditions in Poland over the Past 60 Years Evaluated by the Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index. Acta Geophys. 2016, 64, 2530–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pińskwar, I.; Choryński, A.; Kundzewicz, Z.W. Severe Drought in the Spring of 2020 in Poland—More of the Same? Agronomy 2020, 10, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamuz, E.; Bogdanowicz, E.; Senbeta, T.B.; Napiórkowski, J.J.; Romanowicz, R.J. Is It a Drought or Only a Fluctuation in Precipitation Patterns?—Drought Reconnaissance in Poland. Water 2021, 13, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczyński, K.; Dyer, J. Changes in streamflow drought and flood distribution over Poland using trend decomposition. Acta Geophys. 2023, 72, 2773–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilvear, D. J. , Bryant, R., & Hardy, T. (1999). Remote sensing of channel morphology and in-stream fluvial processes. Progress in Environmental Science, 1, 257-284.

- Nones, M. Remote sensing and GIS techniques to monitor morphological changes along the middle-lower Vistula river, Poland. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2020, 19, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.; Gooseff, M. River corridor science: Hydrologic exchange and ecological consequences from bedforms to basins. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 6893–6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, A.J.; Gurnell, A.M.; Bertoldi, W.; Drake, N.A. An assessment of the degree to which Landsat TM data can support the assessment of fluvial dynamics, as revealed by changes in vegetation extent and channel position, along a large river. Geomorphology 2013, 202, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulder, M.A.; Skakun, R.S.; Kurz, W.A.; White, J.C. Estimating time since forest harvest using segmented Landsat ETM+ imagery. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2004, 93, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.; Chowdhury, R.M. Evaluation of the river Padma morphological transition in the central Bangladesh using GIS and remote sensing techniques. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2021, 21, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I.; Dey, J.; Munna, M.R.; Preya, A.; Nisanur, T.B.; Memy, M.J.; Zeba, M.Z.S. Morphological changes of river Bank Erosion and channel shifting assessment on Arial Khan River of Bangladesh using Landsat satellite time series images. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Phinn, S.R.; Game, E.T.; Pannell, D.J.; Hobbs, R.J.; Briggs, P.R.; McDonald-Madden, E. Using Landsat observations (1988–2017) and Google Earth Engine to detect vegetation cover changes in rangelands - A first step towards identifying degraded lands for conservation. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2019, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, D.; Gianelle, D.; Scotton, M.; Dalponte, M. Estimating grassland vegetation cover with remote sensing: A comparison between Landsat-8, Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope imagery. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, F.; Walker, E.; Frau, D.; Gutierrez, M.F. (2024). Temporal and spatial patterns of riparian vegetation in the Colastiné Basin (Argentina) and riparian ecological quality estimation as toohttps://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2024.2414202ls for water management. International Journal of River Basin Management, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nones, M.; Guerrero, M.; Schippa, L.; Cavalieri, I. Remote sensing assessment of anthropogenic and climate variation effects on river channel morphology and vegetation: Impact of dry periods on a European piedmont river. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2024, 49, 1632–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiminia, H.; Salehi, B.; Mahdianpari, M.; Quackenbush, L.; Adeli, S.; Brisco, B. Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: A meta-analysis and systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 2020, 164, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cutillas, P.; Pérez-Navarro, A.; Conesa-García, C.; Zema, D.A.; Amado-Álvarez, J.P. What is going on within google earth engine? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Remote. Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mossa, J.; Singh, K.K. Floodplain characteristics affect woody vegetation regeneration on point bars of a coastal plain river recovering from anthropogenic disturbances. Ecohydrology 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivaes, R.; Rodríguez-González, P.M.; Albuquerque, A.; Pinheiro, A.N.; Egger, G.; Ferreira, M.T. Riparian vegetation responses to altered flow regimes driven by climate change in Mediterranean rivers. Ecohydrology 2012, 6, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cong, N.; Wang, N.; Yao, W. Impacts of the Three Gorges Dam on riparian vegetation in the Yangtze River Basin under climate change. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 912, 169415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naiman, R.J.; Décamps, H. The Ecology of Interfaces: Riparian Zones. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1997, 28, 621–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.; Tabacchi, E.; Dufour, S.; Corenblit, D.; Peiry, J. Hydrogeomorphic processes affecting riparian habitat within alluvial channel–floodplain river systems: a review for the temperate zone. River Res. Appl. 2005, 21, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nones, M.; Di Silvio, G. Modeling of River Width Variations Based on Hydrological, Morphological, and Biological Dynamics. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2016, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicki, G.; Sudra, P.; Lewicki, T.; Pawłowski, K.; Jóźwiak, J.; Chormański, J. Dry Means Green—Using ALS LiDAR DEM to Determine the Geomorphological Reaction of a Large, Untrained, European River to Summer Drought (the Vistula River, Warsaw, Poland). IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote. Sens. 2024, 18, 2157–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W., Jr. Monitoring the Vernal Advancement and Retrogradation (Green Wave Effect) of Natural Vegetation; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 1973; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.; Venevsky, S.; Wu, C.; Wang, M. NDVI-based vegetation dynamics and its response to climate changes at Amur-Heilongjiang River Basin from 1982 to 2015. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 650, 2051–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, W. General characteristics of the Vistula and its basin. Acta Energetica Power Eng. Q. 2013, 2, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamuz, E.; Romanowicz, R.J. Temperature Changes and Their Impact on Drought Conditions in Winter and Spring in the Vistula Basin. Water 2021, 13, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkel, L. Reflection of the glacial-interglacial cycle in the evolution of the Vistula river Basin, Poland. Terra Nova 1994, 6, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.W.; Petts, G.E.; Moller, H.; Roux, A.L. Historical Change of Large Alluvial Rivers: Western Europe. Geogr. J. 1990, 156, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ajczak, A.; Plit, J.; Soja, R.; Starkel, L.; Warowna, J. (2006). Changes of the Vistula River Channel and Foodplain in the Last 200 Years. Geographia Polonica, 79(2), 65–87.

- Babiński, Z. Hydromorphological consequences of regulating the lower vistula, Poland. Regul. Rivers: Res. Manag. 1992, 7, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, M. Effects of flow regulation and river channelization on sandbar bird nesting availability at the Lower Vistula River. Ecol. Quest. 2018, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisimenka, A.; Kubicki, A. Bedload transport in the Vistula River mouth derived from dune migration rates, southern Baltic Sea. Oceanologia 2019, 61, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, M.; Leuven, R.S.; Lenders, H.R.; Chmielewski, T.J.; Geerling, G.W.; Smits, A.J. Assessing landscape change and biodiversity values of the Middle Vistula river valley, Poland, using BIO-SAFE. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 92, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S.; Colin, O.; Fernandez, V.; Gascon, F.; Hoersch, B.; Isola, C.; Laberinti, P.; Martimort, P.; et al. Sentinel-2: ESA's Optical High-Resolution Mission for GMES Operational Services. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foga, S.; Scaramuzza, P.L.; Guo, S.; Zhu, Z.; Dilley, R.D.; Beckmann, T.; Schmidt, G.L.; Dwyer, J.L.; Hughes, M.J.; Laue, B. Cloud detection algorithm comparison and validation for operational Landsat data products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 194, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothroyd, R.J.; Nones, M.; Guerrero, M. Deriving Planform Morphology and Vegetation Coverage From Remote Sensing to Support River Management Applications. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džubáková, K.; Molnar, P.; Schindler, K.; Trizna, M. Monitoring of riparian vegetation response to flood disturbances using terrestrial photography. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'CAllaghan, M.; del Hoyo, J.G.; Finch, B.D.; Ruiz-Villanueva, V. Grow With the Flow? Impact of Experimental Floods on Riparian Vegetation in an Alpine River. River Res. Appl. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylak, R.; Oliński, P.; Koprowski, M.; Filipiak, J.; Pospieszyńska, A.; Chorążyczewski, W.; Puchałka, R.; Dąbrowski, H.P. Droughts in the area of Poland in recent centuries in the light of multi-proxy data. Clim. Past 2020, 16, 627–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasiewicz, D.W.; Wierzbicki, G. Flood Perception from Local Perspective of Rural Community vs. Geomorphological Control of Fluvial Processes in Large Alluvial Valley (the Middle Vistula River, Poland). Hydrology 2023, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintenberger, C.L.; Rodrigues, S.; Greulich, S.; Bréhéret, J.G.; Jugé, P.; Tal, M.; Dubois, A.; Villar, M. Control of Non-migrating Bar Morphodynamics on Survival of Populus nigra Seedlings during Floods. Wetlands 2019, 39, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.Y.; Bras, R.L.; Vivoni, E.R. Vegetation-hydrology dynamics in complex terrain of semiarid areas: 1. A mechanistic approach to modeling dynamic feedbacks. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.S.; Bhandari, M.; Bandini, F.; Pizarro, A.; Perks, M.; Joshi, D.R.; Wang, S.; Dogwiler, T.; Ray, R.L.; Kharel, G.; et al. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Hydrology and Water Management: Applications, Challenges, and Perspectives. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgogno-Mondino, E.; Lessio, A.; Gomarasca, M.A. A fast operative method for NDVI uncertainty estimation and its role in vegetation analysis. Eur. J. Remote. Sens. 2016, 49, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, E.P.; Huete, A.R.; Nagler, P.L.; Nelson, S.G. Relationship Between Remotely-sensed Vegetation Indices, Canopy Attributes and Plant Physiological Processes: What Vegetation Indices Can and Cannot Tell Us About the Landscape. Sensors 2008, 8, 2136–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzolan, E.; Brenna, A.; Surian, N.; Carbonneau, P.; Bizzi, S. Quantifying the Impact of Spatiotemporal Resolution on the Interpretation of Fluvial Geomorphic Feature Dynamics From Sentinel 2 Imagery: An Application on a Braided River Reach in Northern Italy. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xia, H.; Pan, L.; Song, H.; Niu, W.; Wang, R.; Li, R.; Bian, X.; Guo, Y.; Qin, Y. Drought Monitoring over Yellow River Basin from 2003–2019 Using Reconstructed MODIS Land Surface Temperature in Google Earth Engine. Remote. Sens. 2021, 13, 3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, S.; Zhan, B.; Zhan, C. Detection and Attribution of Vegetation Dynamics in the Yellow River Basin Based on Long-Term Kernel NDVI Data. Remote. Sens. 2024, 16, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekel, J.-F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A.S. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 2016, 540, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.E.; Nilsson, C. Responses of riparian plants to flooding in free-flowing and regulated boreal rivers: an experimental study. J. Appl. Ecol. 2002, 39, 971–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.A.; Webb, J.A.; de Little, S.C.; Stewardson, M.J. Environmental Flows Can Reduce the Encroachment of Terrestrial Vegetation into River Channels: A Systematic Literature Review. Environ. Manag. 2013, 52, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).