Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

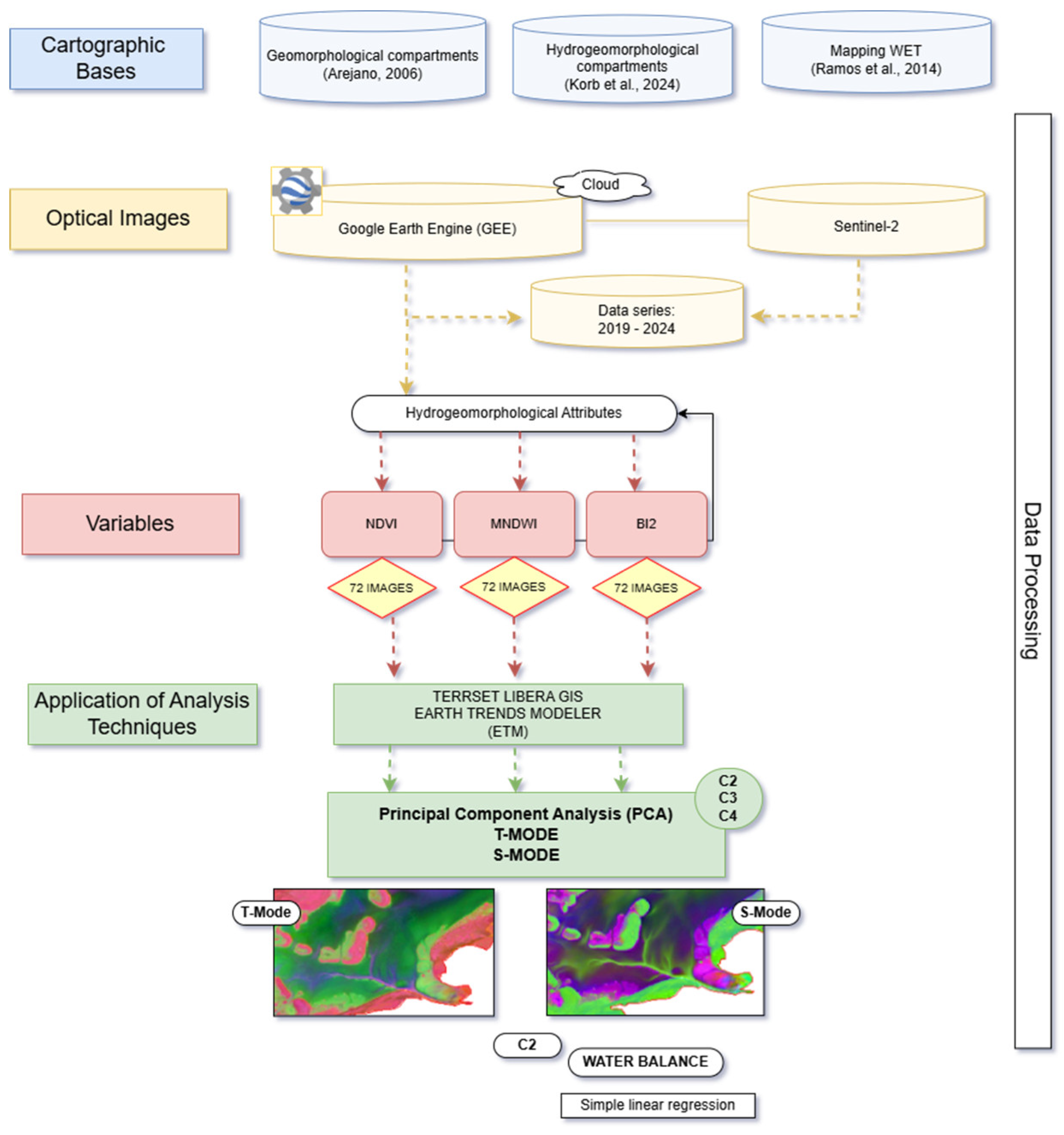

2. Materials and Methods

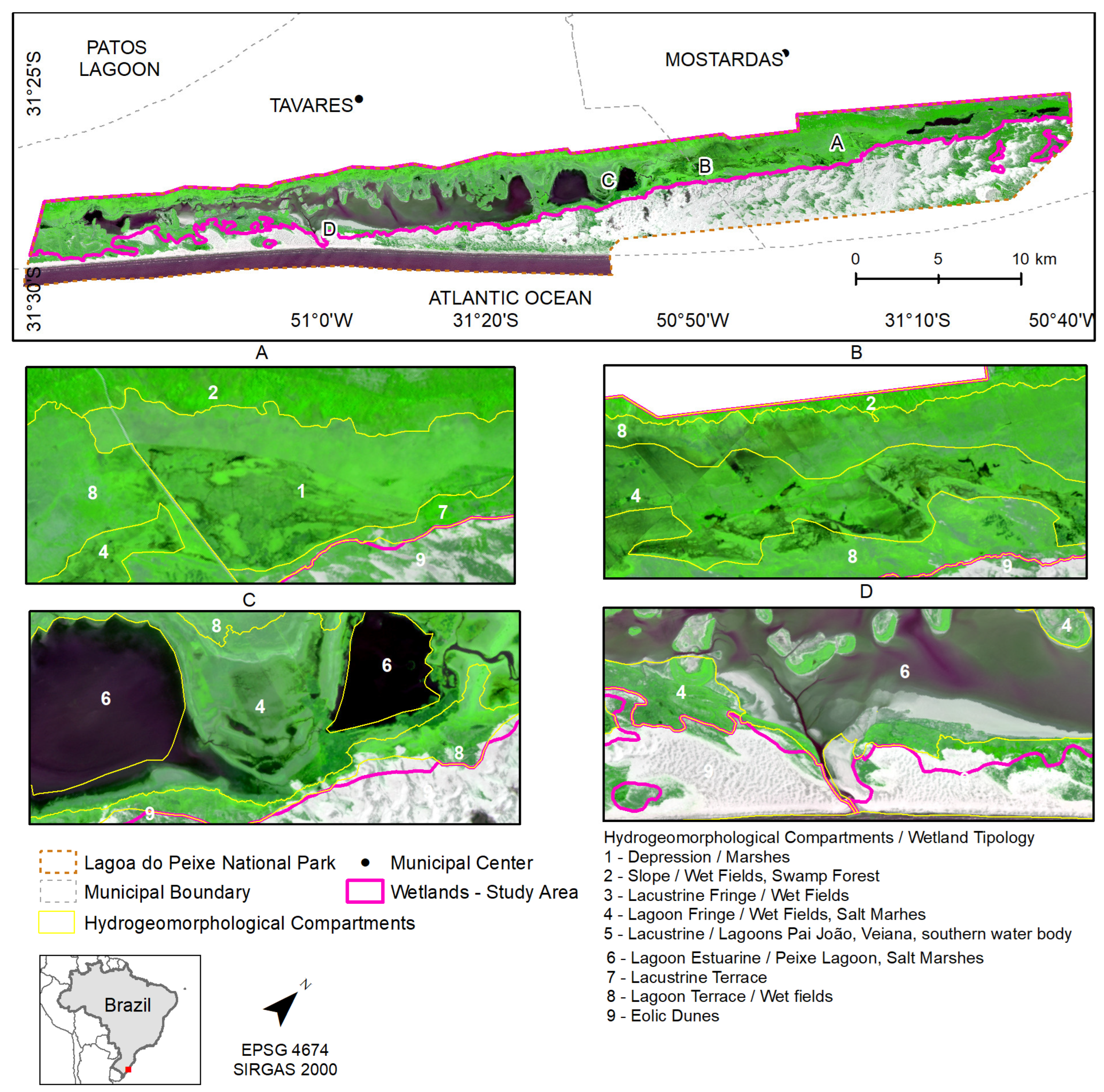

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Procedures

2.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3. Results

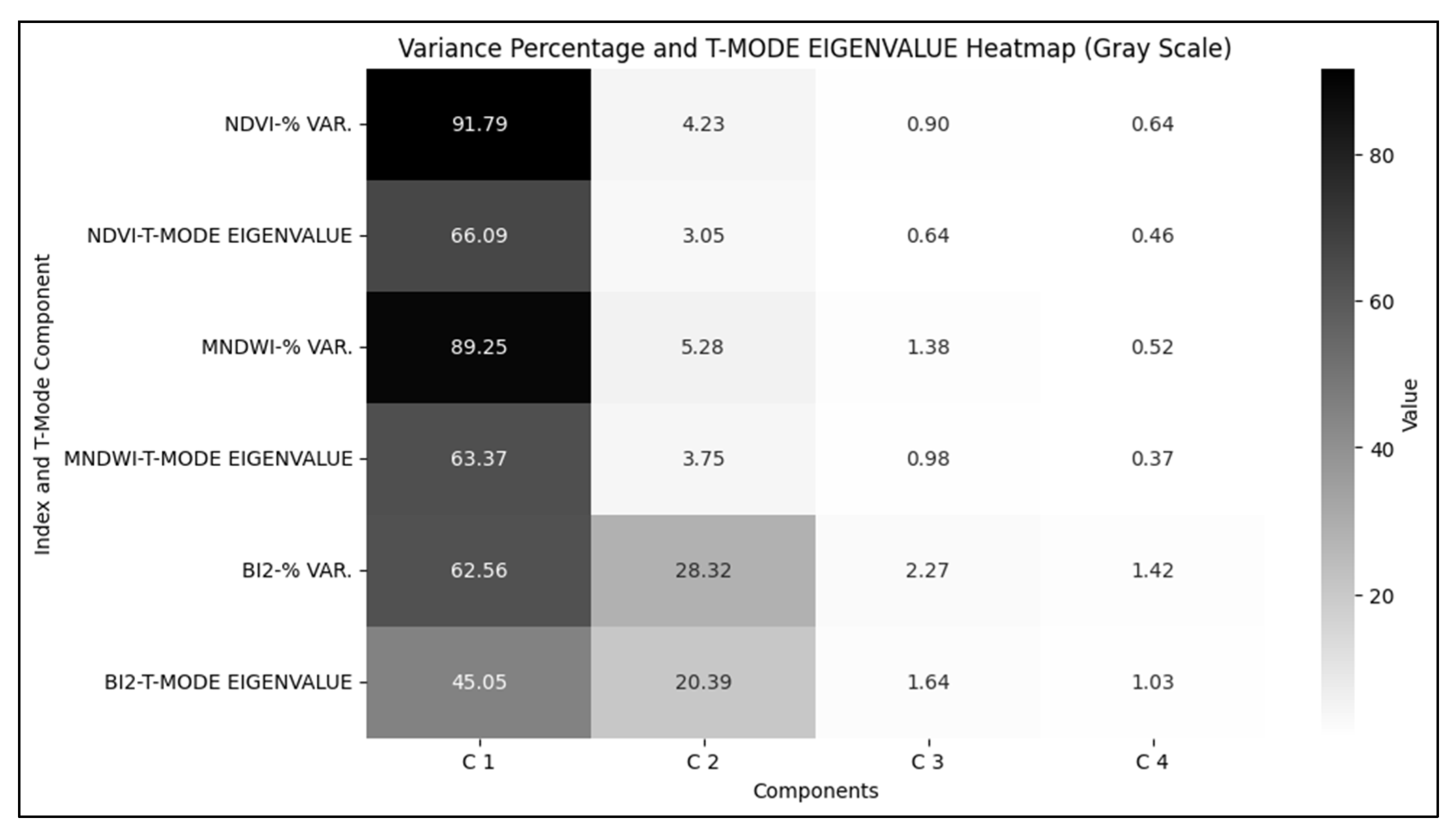

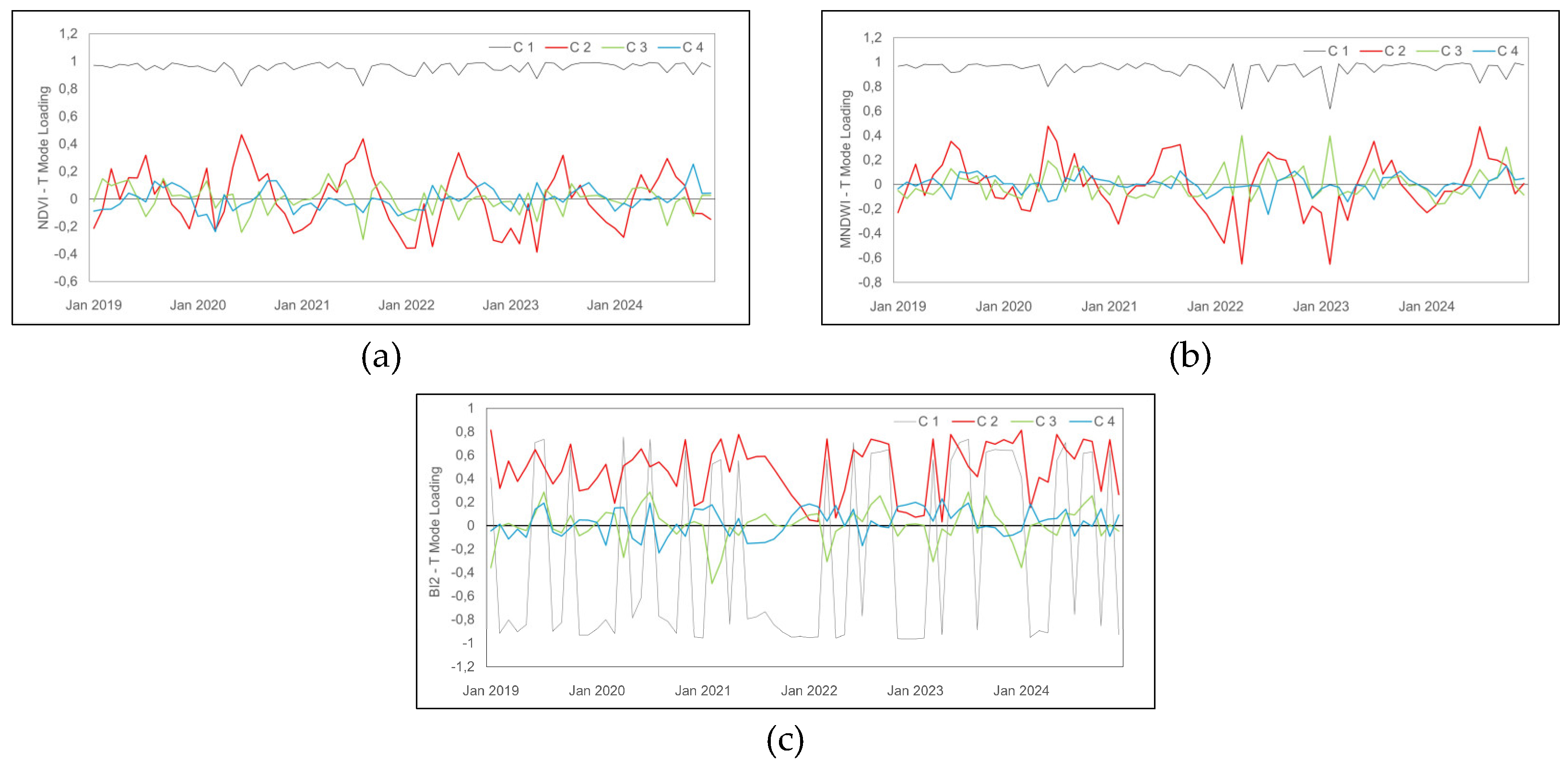

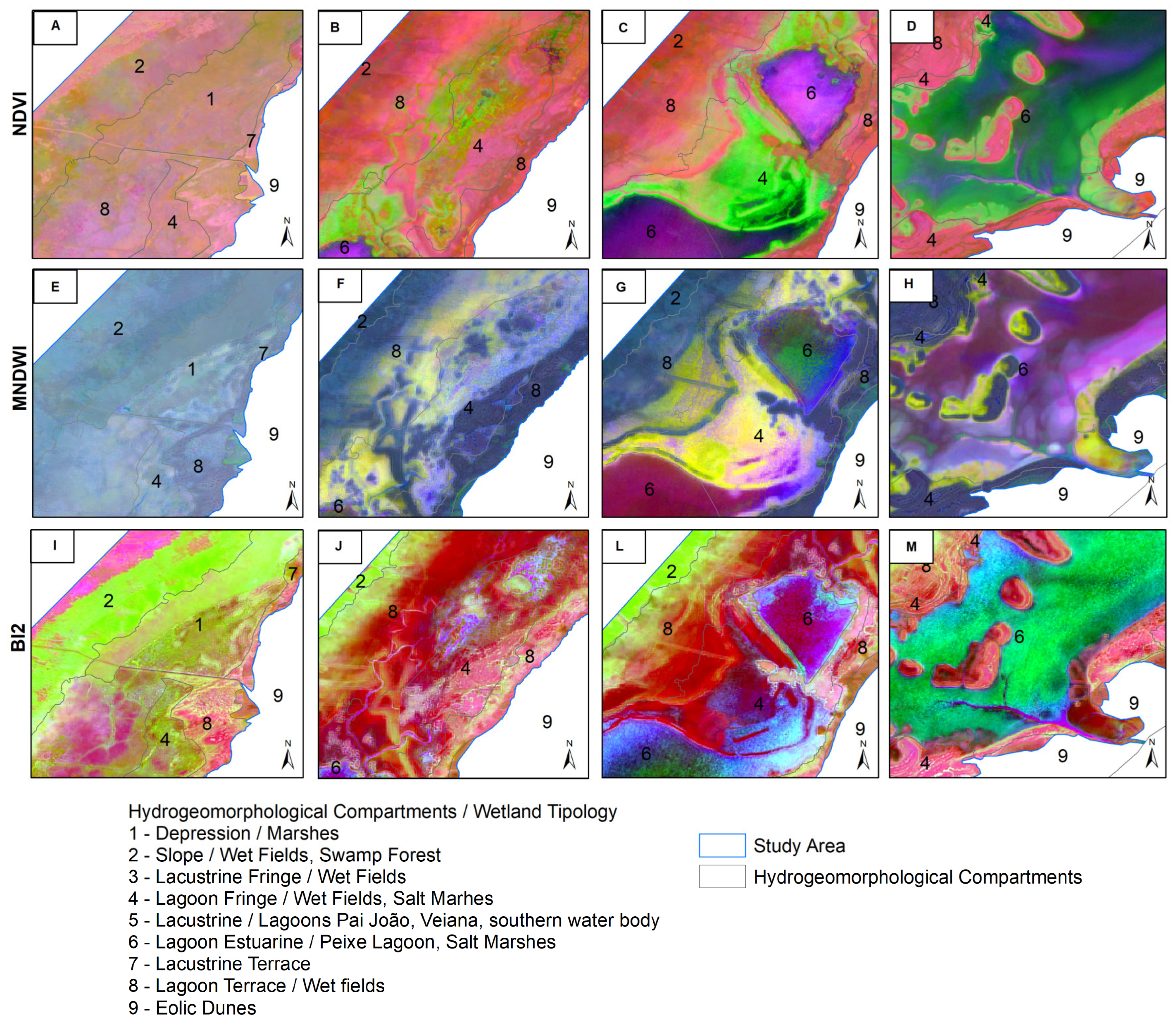

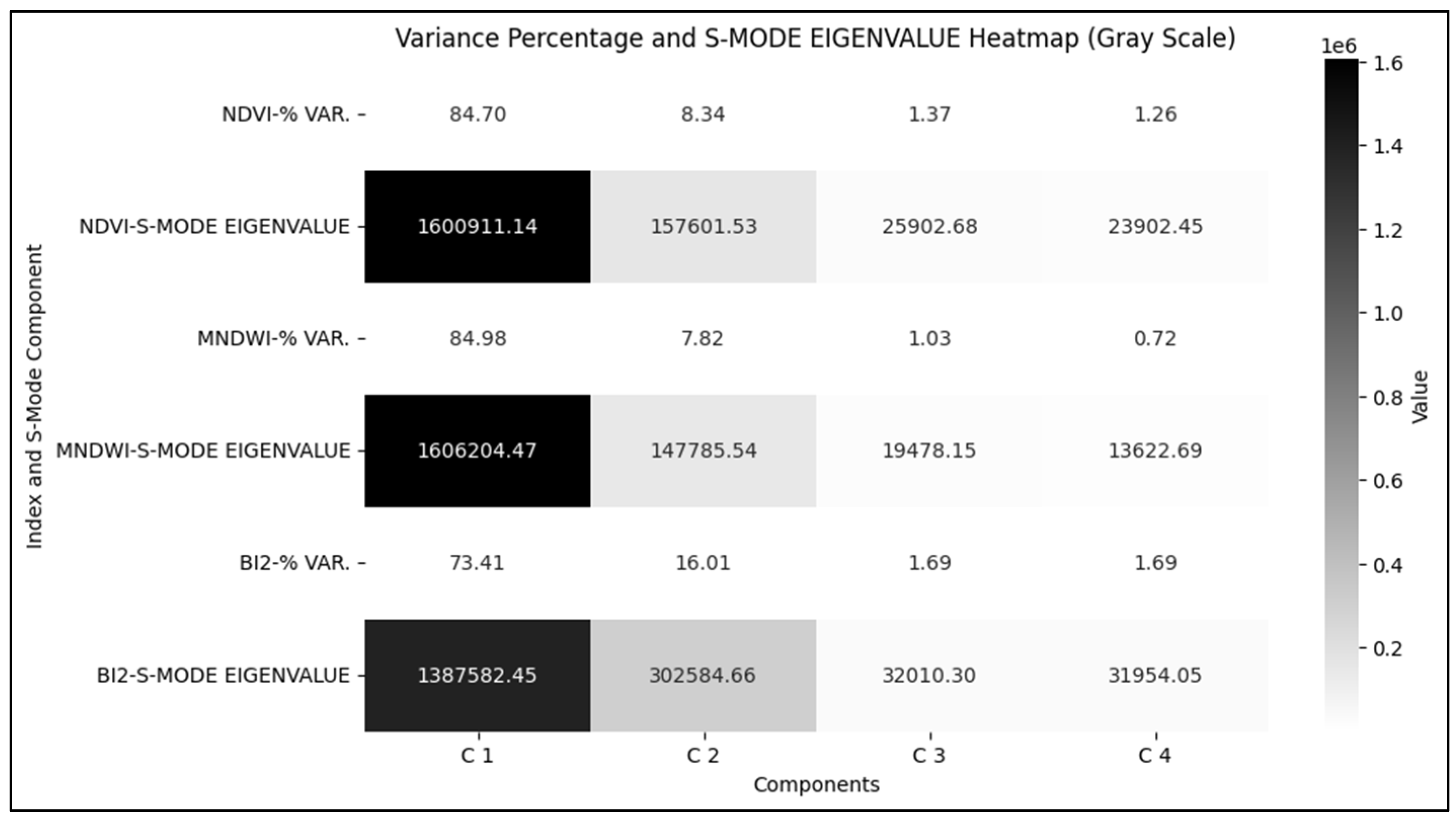

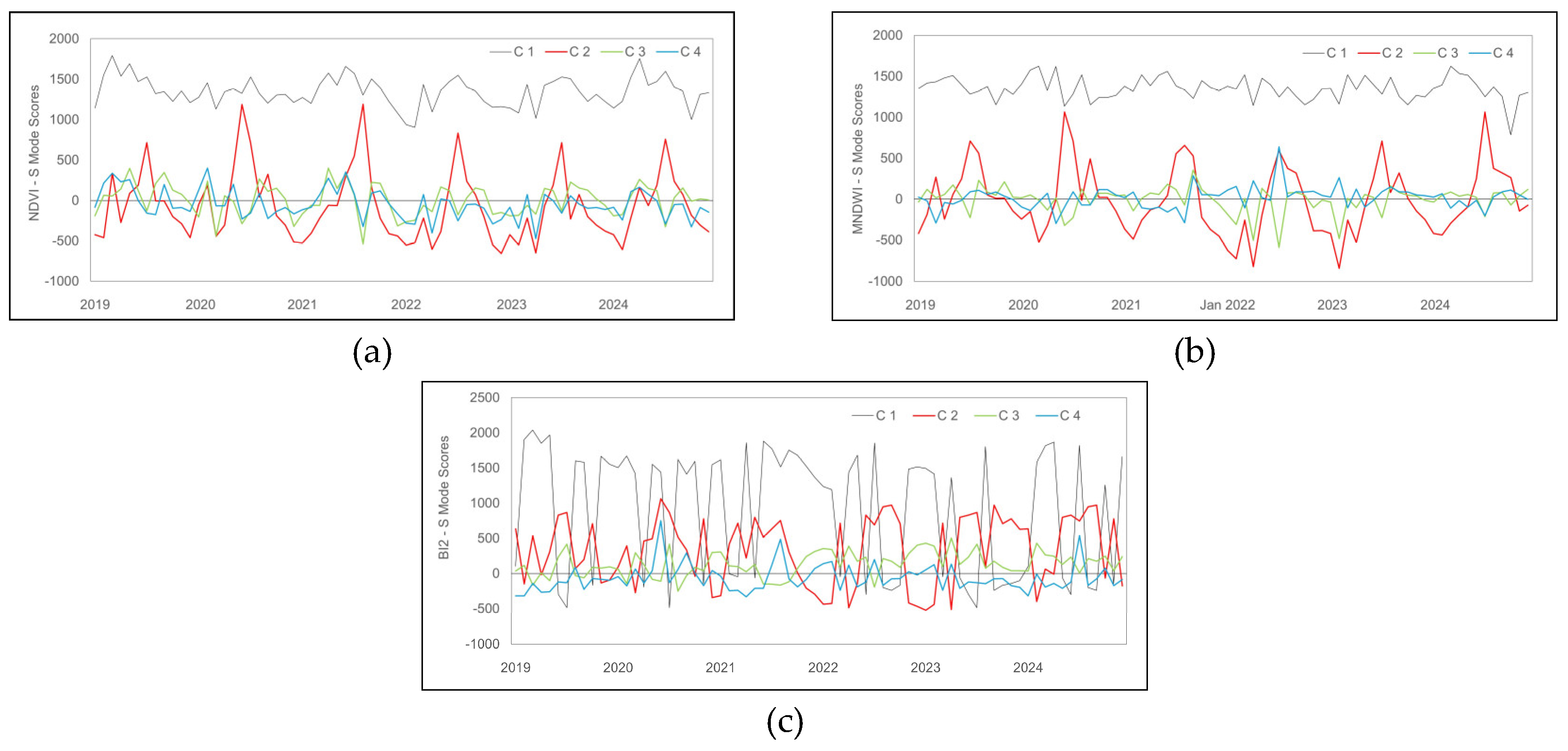

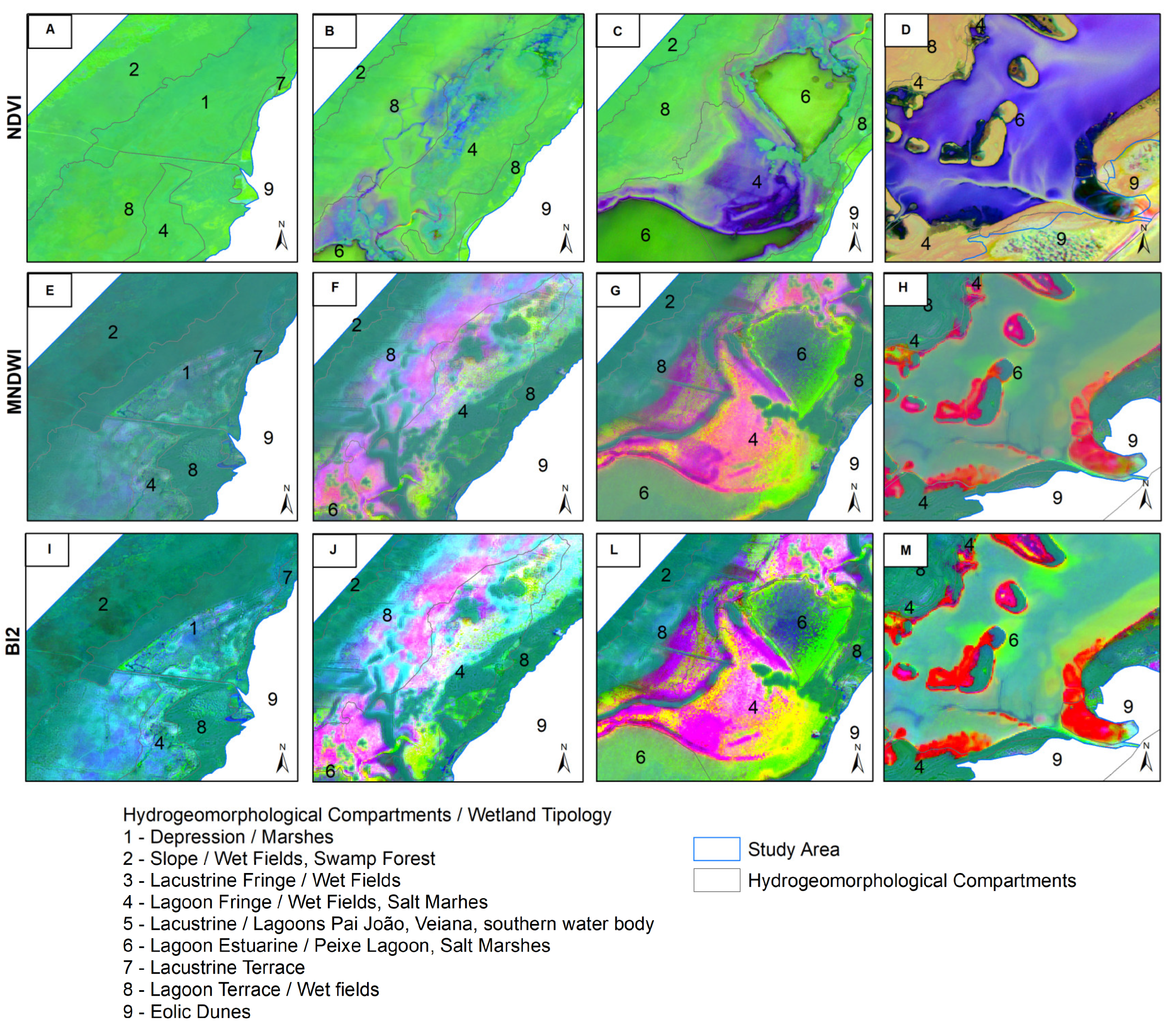

3.1. Temporal and Spatial Variability

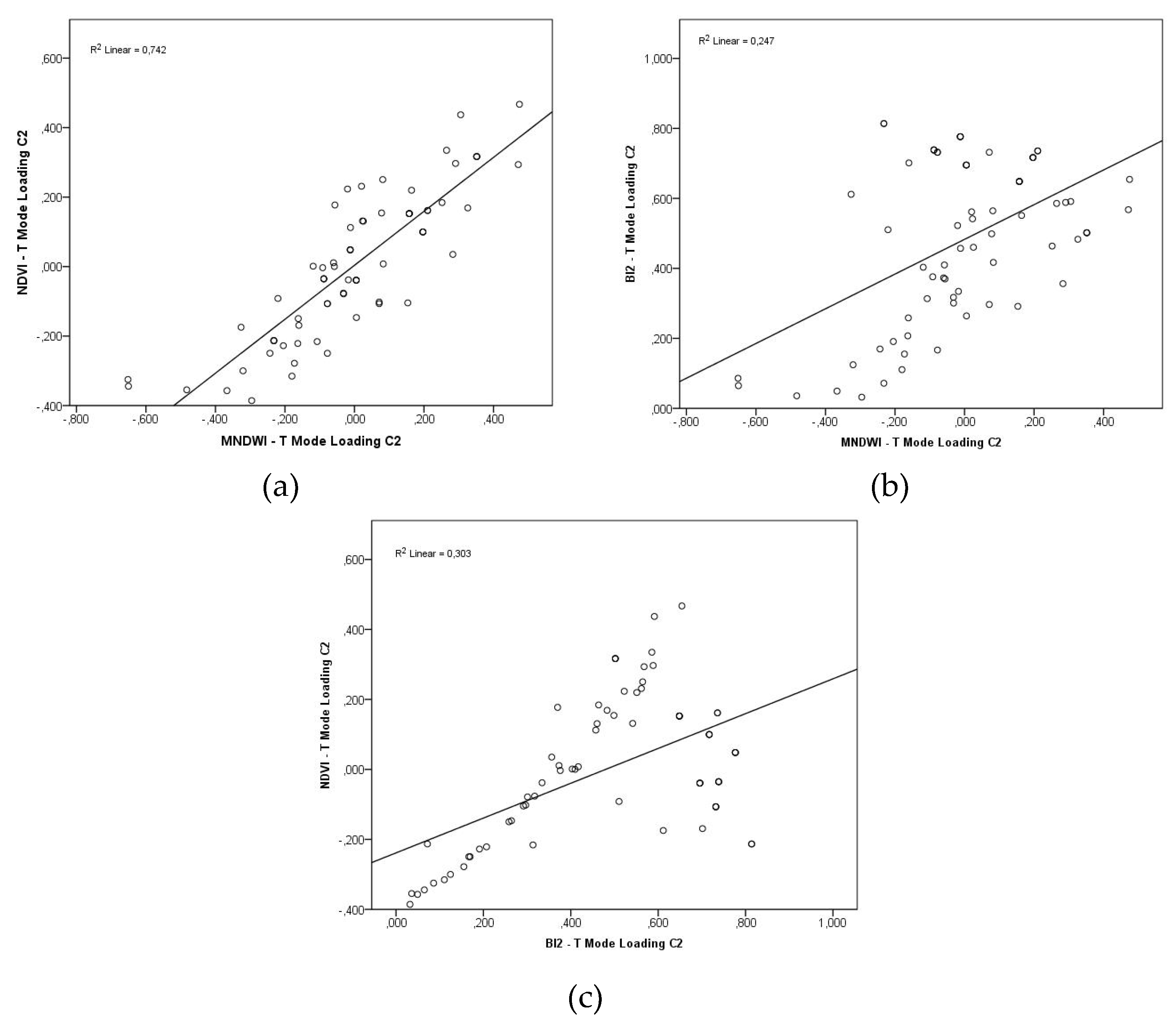

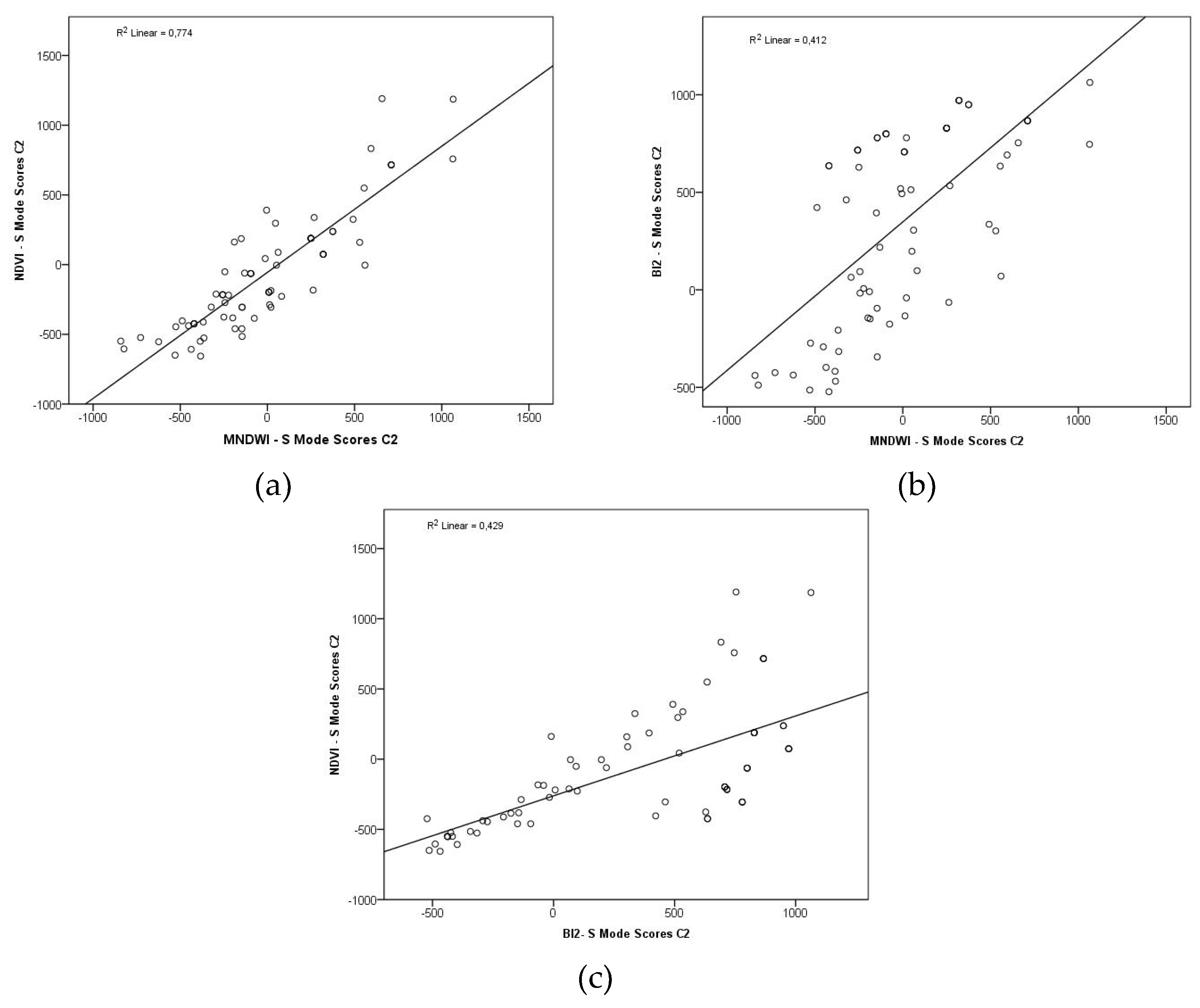

3.2. Relationship Between Hydrogeomorphological Attributes

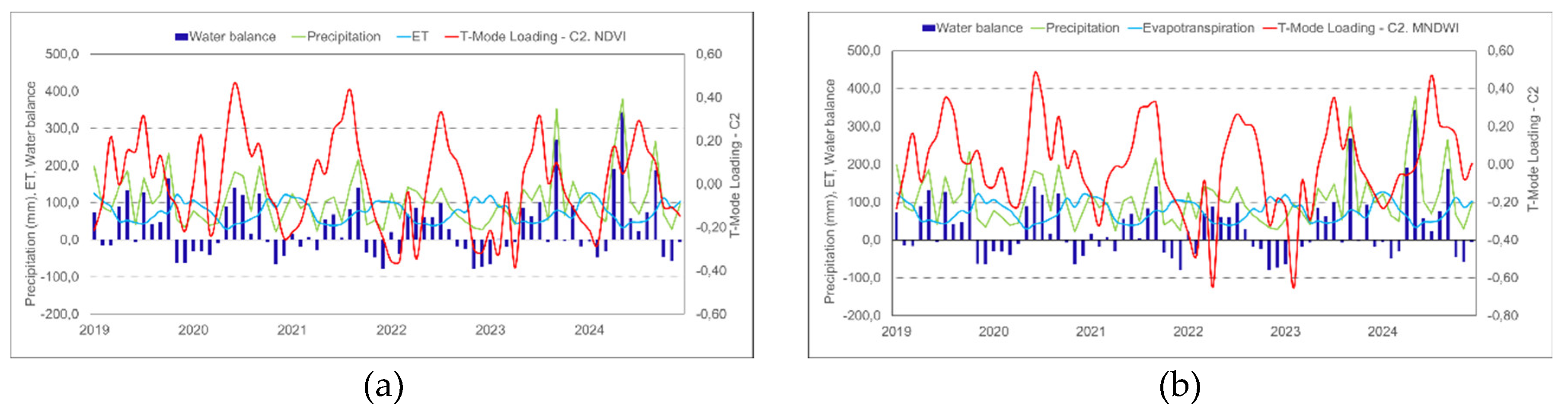

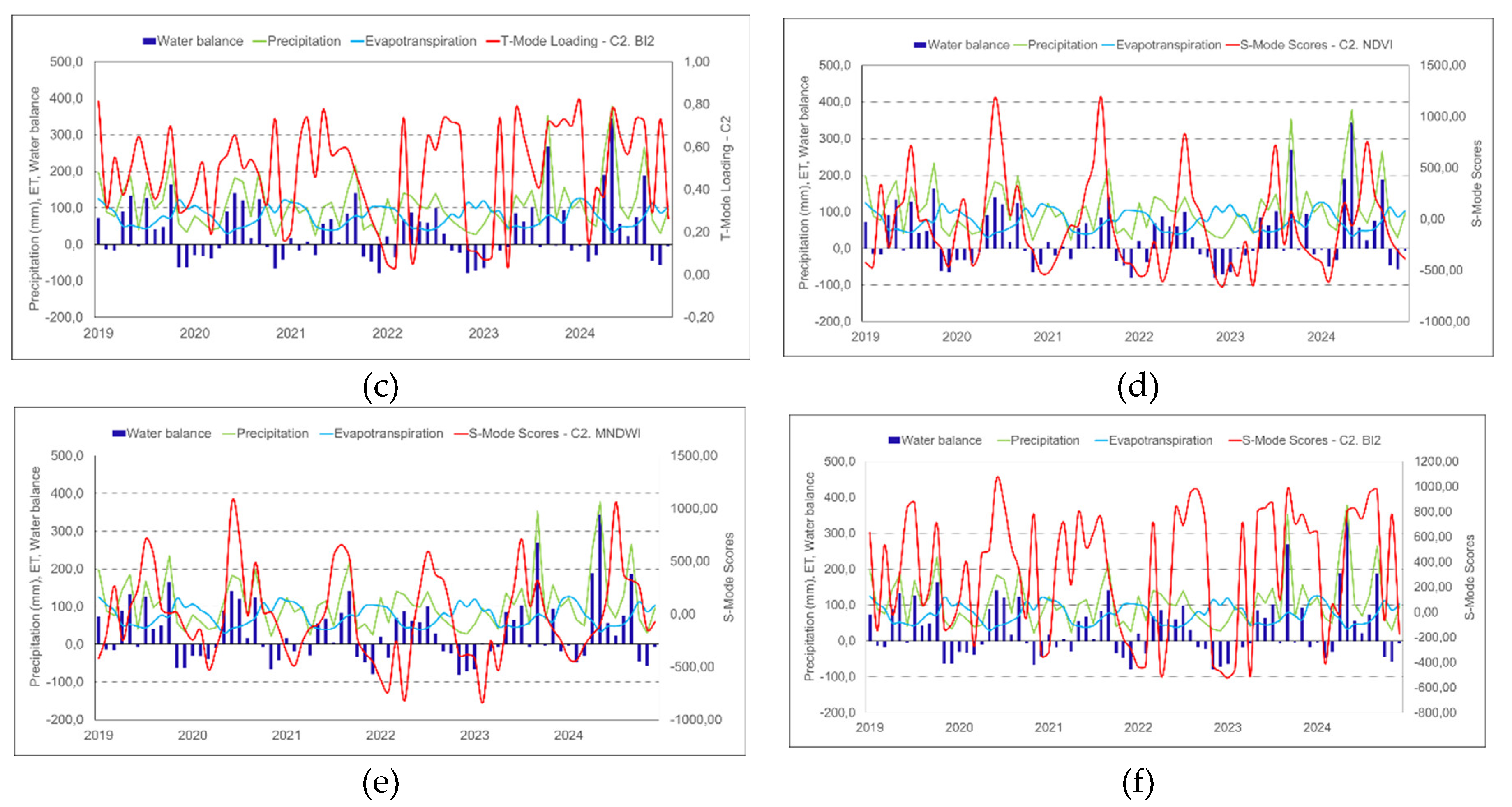

3.3. Hydrogeomorphological Attributes and Water Balance

4. Discussion

4.1. Temporal and Spatial Variability

4.2. Hydrogeomorphological Interactions

5. Conclusions

Implications for Conservation and Future Research

- Continuous monitoring of coastal wetlands, integrating remote sensing and hydrological data to anticipate responses to climate change;

- Differentiated protection by compartment, considering the higher sensitivity of areas such as the Lagoon Fringe to hydrological variations;

- Investigation of subsurface processes, such as water storage and exchanges with the water table, to better understand soil and vegetation resilience.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitsch, W.J.; Bernal, B.; Nahlik, A.M.; Mander, Ü.; Zhang, L.; Anderson, C.J.; Jørgensen, S.E.; Brix, H. Wetlands, Carbon, and Climate Change. Landscape Ecol 2013, 28, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simioni, J.P.D. Métodos de Classificação de Imagens de Satélite Para Delineamento de Banhados. Tese de Doutorado, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sensoriamento Remoto, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, 2021.

- Aitali, R.; Snoussi, M.; Kolker, A.S.; Oujidi, B.; Mhammdi, N. Effects of Land Use/Land Cover Changes on Carbon Storage in North African Coastal Wetlands. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2022, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, K.L. Wetlands and Global Climate Change: The Role of Wetland Restoration in a Changing World. Wetlands Ecol Manage 2009, 17, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S.; Xu, X.; Jia, G.; Zhang, A. Interannual Variability of Global Wetlands in Response to El Niño Southern Oscillations (ENSO) and Land-Use. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, W.; Peng, K.; Wu, Z.; Ling, Z.; Li, Z. Assessment of the Impact of Wetland Changes on Carbon Storage in Coastal Urban Agglomerations from 1990 to 2035 in Support of SDG15.1. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 877, 162824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Jackson, R.B.; Bousquet, P.; Poulter, B.; Canadell, J.G. The Growing Role of Methane in Anthropogenic Climate Change. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 120207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBE The IPBES Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for the Americas; Zenodo. 2018.

- Kuenzer, C.; Bluemel, A.; Gebhardt, S.; Quoc, T.V.; Dech, S. Remote Sensing of Mangrove Ecosystems: A Review. Remote Sensing 2011, 3, 878–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcleod, E.; Chmura, G.L.; Bouillon, S.; Salm, R.; Björk, M.; Duarte, C.M.; Lovelock, C.E.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Silliman, B.R. A Blueprint for Blue Carbon: Toward an Improved Understanding of the Role of Vegetated Coastal Habitats in Sequestering CO2. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2011, 9, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, M.L.; Megonigal, J.P. Tidal Wetland Stability in the Face of Human Impacts and Sea-Level Rise. Nature 2013, 504, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Stocker, B.D.; Zhang, Z.; Malhotra, A.; Melton, J.R.; Poulter, B.; Kaplan, J.O.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Siebert, S.; Minayeva, T.; et al. Extensive Global Wetland Loss over the Past Three Centuries. Nature 2023, 614, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Peng, S.; Ciais, P.; Chen, Y. Nature Climate Change. 2021, pp. 45–51p.

- Hu, S.; Niu, Z.; Chen, Y. Global Wetland Datasets: A Review. Wetlands 2017, 37, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, S.; Liang, Z.; Xu, S.; Yang, X.; Li, X. Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data for Wetland Information Extraction: A Case Study of the Nanweng River National Wetland Reserve. Sensors 2024, 24, 6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salimi, S.; Almuktar, S.A.A.A.N.; Scholz, M. Impact of Climate Change on Wetland Ecosystems: A Critical Review of Experimental Wetlands. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 286, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.W.; Christian, R.R.; Boesch, D.M.; Yáñez-Arancibia, A.; Morris, J.; Twilley, R.R.; Naylor, L.; Schaffner, L.; Stevenson, C. Consequences of Climate Change on the Ecogeomorphology of Coastal Wetlands. Estuaries and Coasts 2008, 31, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas-Cordero, N.; Marcinkowski, P.; Stachowicz, M.; Grygoruk, M. On the Role of Water Balance as a Prerequisite for Aquatic and Wetland Ecosystems Management: A Case Study of the Biebrza Catchment, Poland. Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology 2024, 24, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlanga-Robles, C.A. Trends in Mangrove Canopy and Cover in the Teacapan-Agua Brava Lagoon System (Marismas Nacionales) in Mexico: An Approach Using Open-Access Geospatial Data. Wetlands 2024, 45, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyati, C. Use of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Remote Sensing Images in Wetland Change Detection on the Kafue Flats, Zambia. Geocarto International 2004, 19, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torbick, N.; Becker, B. Evaluating Principal Components Analysis for Identifying Optimal Bands Using Wetland Hyperspectral Measurements From the Great Lakes, USA. Remote Sensing 2009, 1, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, M.; Küçükönder, M. An Examination of Temporal Changes in Göksu Delta (Turkey) Using Principle Component Analysis. SSRN Journal 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M.; Tan, Z. Dynamic Landscapes and the Driving Forces in the Yellow River Delta Wetland Region in the Past Four Decades. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 787, 147644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelwa, S.A.; Sanda, A.B.; Usman, U. Spatio-Temporal Assessment of Vegetation Resource Dynamics in Nigeria from SPOT Satellite Imageries. American Journal of Climate Change 2019, 8, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.; Sousa, D.; Quandt, A.; Ganster, P.; Biggs, T. Mapping Multi-Decadal Wetland Loss: Comparative Analysis of Linear and Nonlinear Spatiotemporal Characterization. Remote Sensing of Environment 2024, 302, 113969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, T.I.R.; Penatti, N.C.; Ferreira, L.G.; Arantes, A.E.; do Amaral, C.H. Principal Component Analysis Applied to a Time Series of MODIS Images: The Spatio-Temporal Variability of the Pantanal Wetland, Brazil. Wetlands Ecol Manage 2015, 23, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.E.; Noveli, R.A.P.; Filho, A.C.P. USO DE ANÁLISE DE COMPONENTES PRINCIPAIS (ACP) PARA CARACTERIZAÇÃO DAS SUB-REGIÕES DO MEGALEQUE DO TAQUARI – PANTANAL. Revista GeoPantanal 2023, 18, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronova, I.; Gong, P.; Wang, L.; Zhong, L. Mapping Dynamic Cover Types in a Large Seasonally Flooded Wetland Using Extended Principal Component Analysis and Object-Based Classification. Remote Sensing of Environment 2015, 158, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W.J. Definição, Delineamento e Classificação Brasileira Das Áreas Úmidas. In Inventário das áreas úmidas brasileiras: Distribuição, ecologia, manejo, ameaças e lacunas de conhecimento; Carlini & Caniato Editorial: Cuiabá - MT, 2024; 42p, ISBN 978-85-8009-353-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, R.A.; Pasqualeto, A.I.; Balbueno, R.A.; Das Neves, D.D.; De Quadros, E.L.L. Mapeamento e Diagnóstico de Áreas Úmidas No Rio Grande Do Sul, Com o Uso de Ferramentas de Geoprocessamento. In Proceedings of the Anais; 2014; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Belloli, T.F.; Guasselli, L.A.; Cunha, C.S.; Korb, C.C. Mudanças e Transição da Cobertura e Usoda Terra nas Áreas Úmidas da Região Geomorfológica Planície Costeira - RS. Geo UERJ 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villwock, J.A.; Tomazelli, L.J.; Loss, E.L.; Dehnhardt, E.A.; Bachi, F.A.; Dehnhardt, B.A. Quaternary of South America and Antarctic Peninsula. Geology of the Rio Grande Do Sul Coastal Province 1986, 4, 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tomazelli, L.J.; Villwock, J.A. O Cenozóico Do Rio Grande Do Sul: Geologia Da Planície Costeira. In Geologia do Rio Grande do Sul; Holz, F. & DeRos, L.F., 2000; p. 444.

- Schäffer, A.; Lanzer, R.; Scur, L. 2013.

- Moraes, V.L. Uso Do Solo e Conservação Ambiental No Parque Nacional daLagoa Do Peixe e Entorno (RS). Dissertação de Mestrado, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geografia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, 2009.

- Portz, L.C.; Guasselli, L.A.; Corrêa, I.C.S. Variação Espacial e Temporal de NDVI Na Lagoa Do Peixe, RS. Revista Brasileira de Geografia Física 2011, 5, 897–908. [Google Scholar]

- Schossler, V. Influência Das Mudanças Climáticas Em Geoindicadores Na Costa Sul Do Brasil. Tese de Doutorado, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, 2016.

- Arejano, T.B. Geologia e Evolução Holocênica Do Sistema Lagunar Da Lagoa Do Peixe, Litoral Médio Do Rio Grande Do Sul, Brasil. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências, 2006.

- Streck, E.V.; Kämpf, N.; Dalmolin, R.S.D.; Klamt, E.; Nascimento, P.C.; Scheneider, P.; Giasson, E.; Pinto,, L.F.S. (Eds.) Solos Do Rio Grande Do Sul, 2nd ed. Emater-Ascar: Porto Alegre, 2008.

- Korb, C.C.; Guasselli, L.A.; Belloli, T.F.; Cunha, C.S.; Bauer, A.L.; Brückmann, C. dos S. Hydrogeomorphological compartmentalization in coastal wetlands - Lagoa do Peixe National Park, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Geomorfologia 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboita, M.S.; Ambrizzi, T.; Rocha, R.P. da Relationship between the Southern Annular Mode and Southern Hemisphere Atmospheric Systems Relação Entre o Modo Anular Sul e Os Sistemas Atmosféricos No Hemisfério Sul. Revista Brasileira de Meteorologia 2009, 24, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, D.C.; Berlato, M.A. Influência do El Niño Oscilação Sul sobre a precipitação do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Revista Brasileira de Agrometeorologia 1997, 5, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Britto, F.P.; Barletta, R.; Mendonça, M. Variabilidade Espacial e Temporal da Precipitação Pluvial no Rio Grande Do Sul: influência do fenômeno El Niño Oscilação Sul. Revista Brasileira de Climatologia 2008, 3, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, B.D. Comportamento Dos Sistemas Frontais No Estado Do Rio Grande Do Sul Durante Os Episódios ENOS. Dissertação de Mestrado, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sensoriamento Remoto, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, 2015.

- Sbruzzi, J.B. Análise Da Dinâmica Da Embocadura Da Lagoa Do Peixe - RS Utilizando Dados de Sensoriamento Remoto Orbital. Dissertação de Mestrado, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sensoriamento Remoto, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, 2015.

- Signori, L.M. Mapeamento Por Sensoriamento Remoto de Área de Pinus Spp No Parque Nacional Da Lagoa Do Peixe. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sensoriamento Remoto, 2018.

- Portz, L.; Manzolli, R.P.; Alcántara-Carrió, J.; Rockett, G.C.; Barboza, E.G. Degradation of a Transgressive Coastal Dunefield by Pines Plantation and Strategies for Recuperation (Lagoa Do Peixe National Park, Southern Brazil). Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2021, 259, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS (Earth Resources Technology Satellite).; Greenbelt, 1973; pp. 309–317.

- Xu, H. Modification of Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI) to Enhance Open Water Features in Remotely Sensed Imagery. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2006, 27, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escadafal, R. Remote Sensing of Arid Soil Surface Color with Landsat Thematic Mapper. Advances in Space Research 1989, 9, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepita-Villanueva, M.R.; Berlanga-Robles, C.A.; Ruiz-Luna, A.; Morales Barcenas, J.H. Spatio-Temporal Mangrove Canopy Variation (2001–2016) Assessed Using the MODIS Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI). J Coast Conserv 2019, 23, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Machado, E.A.; Neeti, N.; Eastman, J.R.; Chen, H. Implications of Space-Time Orientation for Principal Components Analysis of Earth Observation Image Time Series. Earth Sci Inform 2011, 4, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeti, N.; Ronald Eastman, J. Novel Approaches in Extended Principal Component Analysis to Compare Spatio-Temporal Patterns among Multiple Image Time Series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2014, 148, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, J.R. TerrSet Libera GIS. Eospatial Monitoring and Modeling System. Tutorial. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliani, C.R.; Hartmann, C.; Calliari, L. J.; Griep, G.H. Geologia e Geomorfologia Da Porção Sul Do Parque Nacional Da Lagoa Do Peixe, RS, Brasil. In Proceedings of the Anais; São Paulo; 1992; pp. 292–294. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, S.; Dardanelli, G. Vegetation Classification and Evaluation of Yancheng Coastal Wetlands Based on Random Forest Algorithm from Sentinel-2 Images. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schossler, V. Morfodinâmica Da Embocadura Da Lagoa Do Peixe e Da Linha de Praia Adjacente. Dissertação de Mestrado, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, 2011.

- Ramsar Convention Secretariat Wetland Inventory: A Ramsar Framework for Wetland Inventory and Ecological Character Description.; 4th ed.; Switzerland, 2010; Vol. 15;

- Doughty, C.L.; Ambrose, R.F.; Okin, G.S.; Cavanaugh, K.C. Characterizing Spatial Variability in Coastal Wetland Biomass across Multiple Scales Using UAV and Satellite Imagery. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation 2021, 7, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinson, M.M. A Hydrogeomorphic Classification for Wetlands 1993.

- Simioni, J.P.D.; Guasselli, L.A.; Etchelar, C.B. Connectivity among Wetlands of EPA of Banhado Grande, RS. RBRH 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, W.; Chen, H.; Xue, B.; Yu, J.; Tian, Z. Interannual and Seasonal Variations of Hydrological Connectivity in a Large Shallow Wetland of North China Estimated from Landsat 8 Images. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Macdonald, S.E. Ecophysiological Adaptations of Black Spruce (Picea Mariana) and Tamarack (Larix Laricina) Seedlings to Flooding. Trees 2004, 18, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Han, G.; Chu, X.; Sun, B.; Song, W.; He, W.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Yu, D. Impactos Prolongados de Eventos Extremos de Precipitação Enfraqueceram a Força Anual Do Sumidouro de CO2 Do Ecossistema Em Uma Área Úmida Costeira. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2021, 310, 108655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korb, C.C.; Guasselli, L.A.; Belloli, T.F.; Cunha, C.S. Dinâmica espaço-temporal de pulsos de inundações nas Áreas Úmidas do Parque Nacional da Lagoa do Peixe, sul do Brasil. Investigaciones Geográficas: Una mirada desde el sur. [CrossRef]

- Rioja-Nieto, R.; Barrera-Falcón, E.; Torres-Irineo, E.; Mendoza-González, G.; Cuervo-Robayo, A.P. Environmental Drivers of Decadal Change of a Mangrove Forest in the North Coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. J Coast Conserv 2017, 21, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penatti, N.C.; Almeida, T.I.R. de; Ferreira, L.G.; Arantes, A.E.; Coe, M.T. Satellite-Based Hydrological Dynamics of the World’s Largest Continuous Wetland. Remote Sensing of Environment 2015, 170, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivory, S.J.; McGlue, M.M.; Spera, S.; Silva, A.; Bergier, I. Vegetation, Rainfall, and Pulsing Hydrology in the Pantanal, the World’s Largest Tropical Wetland. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 124017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos; 2nd ed. 2006.

- Giardina, F.; Gentine, P.; Konings, A.G.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Stocker, B.D. Diagnosing Evapotranspiration Responses to Water Deficit across Biomes Using Deep Learning. New Phytologist 2023, 240, 968–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, B.D.; Tumber-Dávila, S.J.; Konings, A.G.; Anderson, M.C.; Hain, C.; Jackson, R.B. Global Patterns of Water Storage in the Rooting Zones of Vegetation. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Guo, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; van der Tol, C.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, J. Meteorological Controls on Evapotranspiration over a Coastal Salt Marsh Ecosystem under Tidal Influence. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2019, 279, 107755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W.J.; Bayley, P.B.; Sparks, R.E. Flood Pulse Concept in River- Floodplain-Systems.; 1989; Vol. 106, pp. 110–127.

- Wei, S.; Han, G.; Chu, X.; Sun, B.; Song, W.; He, W.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Yu, D. Prolonged Impacts of Extreme Precipitation Events Weakened Annual Ecosystem CO2 Sink Strength in a Coastal Wetland. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2021, 310, 108655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablat, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, Q.; Huang, C. Using MODIS-NDVI Time Series to Quantify the Vegetation Responses to River Hydro-Geomorphology in the Wandering River Floodplain in an Arid Region. Water 2021, 13, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, E.; Porporato, A. Impact of Hydroclimatic Fluctuations on the Soil Water Balance. Water Resources Research 2006, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sinha, R. Hydrogeomorphic Indicators of Wetland Health Inferred from Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing Data for a New Ramsar Site (Kaabar Tal), India. Ecological Indicators 2021, 127, 107739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S. Hydrological Simple Water Balance Modeling for Increasing Geographically Isolated Doline Wetland Functions and Its Application to Climate Change. Ecological Engineering 2020, 149, 105812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penatti, N.C.; de Almeida, T.I.R. Subdvision of Pantanal Quaternary Wetlands: MODIS NDVI Time Series In The Indirect Detection Of Sediments Granulometry. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, B8. [CrossRef]

- Narváez-Salcedo, S.; Hoyos, N.; Aldana-Domínguez, J. Spatial and Temporal Trend of EVI in Mangrove Forests of Coastal Lagoons in the Colombian Caribbean. 2022.

| Hydrogeomorphological attribute / Variable | Formula | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | [48] | |

| Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) | [49] | |

| Second Brightness Index (BI2) | [50] |

| NDVI | MNDWI | BI2 | ||

| NDVI | Pearson Correlation | - | - | - |

| p value | - | - | - | |

| MNDWI | Pearson Correlation | 0,862 | - | - |

| p value | p < 0,001 | - | - | |

| BI2 | Pearson Correlation | 0,550 | 0,497 | - |

| p value | p < 0,001 | p < 0,001 | - | |

| NDVI | MNDWI | BI2 | ||

| NDVI | Pearson Correlation | - | - | - |

| p value | - | - | - | |

| MNDWI | Pearson Correlation | 0,880 | - | - |

| p value | p < 0,001 | - | - | |

| BI2 | Pearson Correlation | 0,655 | 0,642 | - |

| p value | p < 0,001 | p < 0,001 | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).