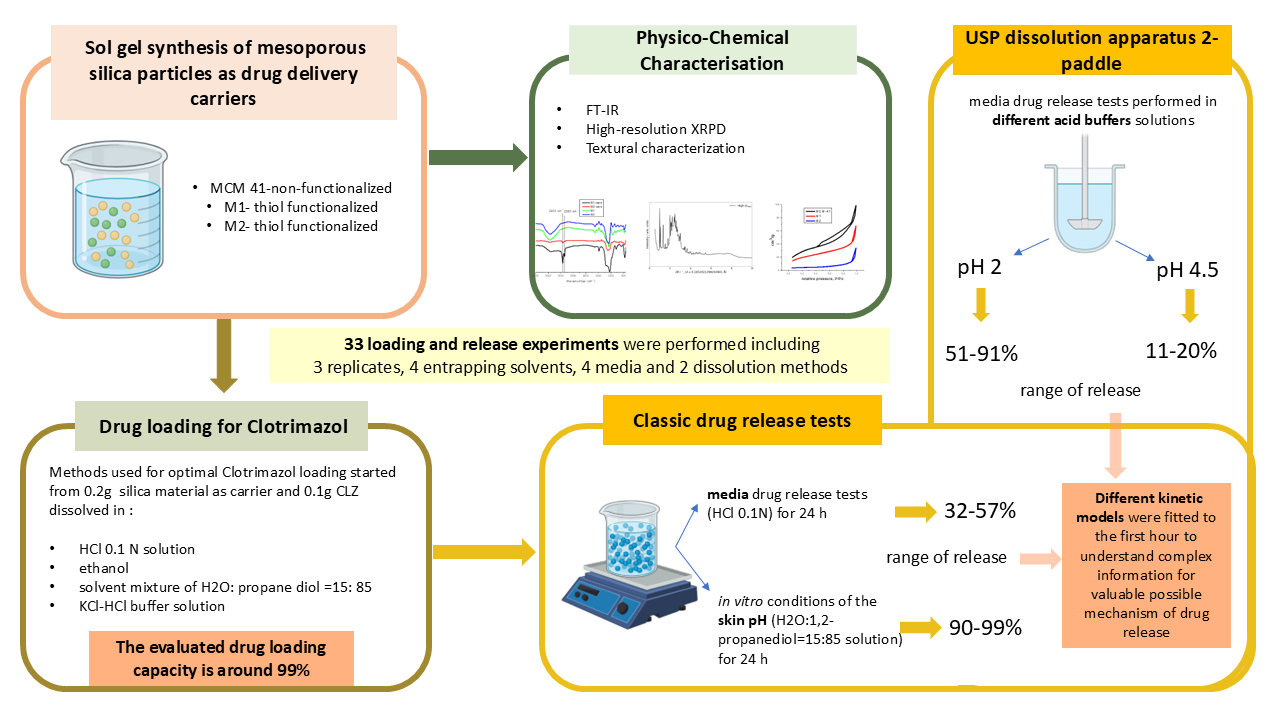

1. Introduction

As the main barrier and defence of the body, the skin is susceptible to different infections, especially fungal infections. Superficial fungal infections produced by dermatophytes affect millions of people and represent one of the main causes of infection [

1,

2]. Dermatophytes invade and disrupt the skin barrier, and the host immune response can lead to pathologic inflammation and subsequent tissue injury [

3]. The majority of fungal infections are opportunistic or secondary infections and it can occur in patients who received antibiotics, corticoids, in immunocompromised patients with severe diseases such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), or those undergoing chemotherapy, or suffering from tuberculosis, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, transplant patients, etc. [

2,

4]. The most common reported fungal infections are superficial and affect the mucosal surfaces, hair, nails, skin, but systemic fungal infections are also reported [

2,

5,

6]. Different antifungal agents are used for the treatment of fungal infections which include azoles (triazoles and imidazoles, such as clotrimazole, an imidazole derivative), polyene antibiotics, allylamines, and others [

1,

7].

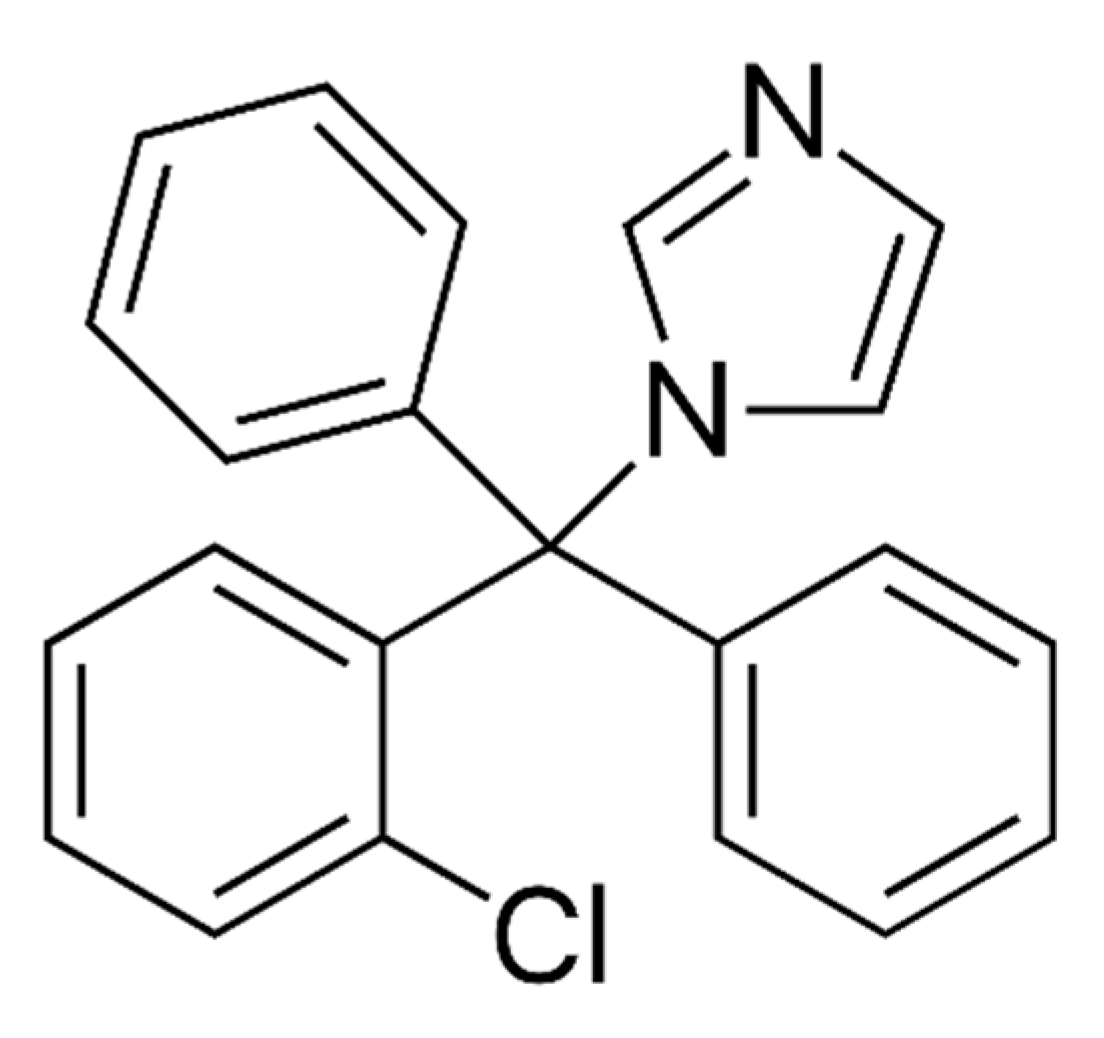

Clotrimazole (1-[(2-chlorophenyl) (diphenyl)methyl]-1H-imidazole) is a broad-spectrum imidazole, antifungal widely used for the topical treatment of superficial mycoses such as

Tinea infections and cutaneous candidiasis [

8]. It exerts its antifungal effect by inhibiting cytochrome P450-dependent lanosterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51), thereby disrupting ergosterol biosynthesis and compromising fungal cell membrane integrity [

9]. Although clotrimazole demonstrates potent local antifungal activity and a favourable safety profile, its therapeutic performance is limited by very low aqueous solubility (≈ 0.49 mg/L) and high lipophilicity (log P ≈ 6.1), resulting in dissolution-rate-limited absorption and low overall bioavailability [

10,

11]. Local adverse effects—such as mild burning, pruritus, erythema, desquamation, or transient edema—are uncommon and typically self-limiting, rarely necessitating discontinuation of therapy [

12,

13]. Its crystalline nature and hydrophobic molecular structure have motivated the development of advanced drug-delivery systems designed to enhance its solubility and dissolution rate.

Various formulation strategies—including solid dispersions, lipid nanocarriers, polymeric micelles, and mesoporous silica systems—have been successfully employed to improve the solubility, dissolution kinetics, and local bioavailability of clotrimazole [

14,

15].

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have emerged as versatile carriers for drug delivery due to their high surface area, tunable pore size, and excellent biocompatibility [

16]. These structural features allow MSNs to efficiently load hydrophobic drugs, including clotrimazole, and to confine them in an amorphous state, improving solubility and dissolution rates [

17]. In addition, the silica matrix protects entrapped molecules from degradation and aggregation, enhancing formulation stability during storage and application [

18]. The abundant surface silanol groups also allow chemical modification or functionalization, enabling controlled or targeted drug release, which can be particularly useful for dermatological applications requiring localized antifungal activity [

16,

18]. The confinement of drug molecules within mesoporous silica matrices can convert crystalline drugs into amorphous states, enhancing wettability and dissolution kinetics [

19,

20]. Among advanced carriers, silica-based nanoparticles offer unique advantages facilitating improved therapeutic performance and potential clinical outcomes. Although clotrimazole has been incorporated into ordered mesoporous silica [

21,

22], quantitative data on enhanced dissolution rates of the clotrimazole--MSN system remains sparse in the literature. General studies on MSNs for poorly soluble drugs suggest marked improvements in release kinetics, supporting the rationale for the current investigation of clotrimazole--loaded silica nanoparticles.

Accordingly, this work aims to develop and characterize clotrimazole-loaded silica nanoparticles as a model nanostructured system for dissolution enhancement. The study focuses on physicochemical characterization and in vitro dissolution profiling to evaluate the potential of silica matrices for improving the delivery of poorly soluble antifungal agents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Synthesis

Chemicals: tetraethoxysilane (TEOS, 99%, for analysis, Merck); Mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilan (MPTS, Aldrich), hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB, Sigma); ethanol (EtOH, Dacami SRL); ammonia (NH

3) solution 25% (Silal Trading SRL). Silica samples were prepared using the sol-gel synthesis with CTAB, TEOS (or TEOS+ Mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilan) in a mixture of ethanol and water with the NH

3 base catalyst. Following molar ratio were used: TEOS: CTAB: EtOH: H

2O: NH

3 =1: 0.15: 63.78: 646: 41.77, for the MCM-41 sample and for the other samples the TEOS amount was kept constant, varying the mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilan added into the reaction mixture. A synopsis of the synthetised samples is presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Characterization Methods

FT-IR (Fourier-transform infrared) spectra were recorded on KBr pellets using a JASCO FT/IR-4200 apparatus (Model Name FT/IR-4200 type A, Light Source Standard, DetectorTGS, Accumulation16, Resolution4 cm-1 Zero Filling On, Apodization Cosine, Gain Auto (2), ApertureAuto (7.1 mm), Scanning Speed Auto (2 m/sec) FilterAuto (30000 Hz) SpectraLab, Shimadzu, Japan). N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms were determined by N2-physisorption measurements at 77 K using Quantachrome Nova 1200e apparatus (Quantachrome Instruments, Boynton Beach, Florida). Prior to the analysis, the samples were dried and degassed in vacuum at room temperature (r.t.) for 15 h. The specific surface area was determined by the Brunauer–Emmet– Teller (BET) method in the relative pressure range P/P0 from 0.05–0.25. The micropore surface area and external surface area were determined using the de Boer’s V-t method from 0.15–0.40. Pore size distribution was evaluated with Density Functional Theory (DFT) equilibrium model (0.05–1 P/P0). The pore size was determined also by BJH method from adsorption or desorption branch. The total pore volumes were determined using the point closest to 1 value for the relative pressure P/P0. The absorbance measurements for clotrimazole were determined using Cary 60 Spectrophotometer Instrument. The drug release profile was tested using a dissolution instrument with automated sampling systems, Model 850-DS (Agilent).

High-resolution synchrotron X-ray diffraction and total scattering measurements [

23,

24] were performed at beamline ID31 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF). The sample powders were loaded into cylindrical wells (approx. 1 mm thickness) held between Kapton windows in a high-throughput sample holder. Each sample was measured in transmission geometry with an incident X-ray energy of 75.051 keV (

λ = 0.16520 Å). Measured intensities were collected using a Pilatus CdTe 2M detector (1679 × 1475 pixels, 172 × 172 µm

2 each) positioned with the incident beam in the corner of the detector. The sample-to-detector distance was approximately 1.5 m for the high-resolution measurements and 0.3 m for the total scattering. Multiple measurements of the empty well with polyimide windows were measured, and summed together for improved statistics, for the background subtraction. NIST SRM 660b (LaB

6) was used for geometry calibration for XRPD and total scattering. Integration was performed with the software pyFAI [

25] including flat-field, geometry, solid-angle, and polarization corrections. Invalid pixels were masked, and the sigma clipping integration algorithm was used to auto-mask further azimuthal outliers. The summed background intensities were scaled respectively to each of the reference and sample measurements and subtracted. Rietveld refinements were performed using TOPAS v7 [

26] to fit the structure with the reference lattice parameter fixed to the measurement to determine the instrumental profile contribution and correct for offset errors including parallax [

27]. PDF data were processed in an automated way using PDFgetX3 [

28,

29,

30] using a

Qmax value of 20.0 Å

-1. Then the data were reprocessed using a Lorch modification function [

31] to suppress termination effects and contributions from high frequency noise.

2.3. Application of the Obtained Materials as Drug Carriers

2.3.1. Chemicals

The basic starting chemicals are: Clotrimazole (CLZ, gift from a Pharmaceutical Company); Hydrochloric acid 37% (SC Silal Trading SRL); ethanol (EtOH, SC Chimopar Trading SRL); 1,2-propanediol (purity >99%, Merck, Hohenbrunn, Germany); KCl (Scharlau Chemie SA, Gato Perez, Spain (molecular Biologie Grade)

2.3.2. Dissolution Media

Four dissolution medias with diverse pH were used as follow: pH 1: HCl 0.1N, pH 2: buffer KCl/HCl, pH 4.5: buffer KH2PO4, and a solvent mixture of H2O: propane diol in 15: 85 proportions. Buffer solutions preparation was made according to European Pharmacopoeia recommendations.

HCl 0.1N (pH=1). For each 1000 mL HCl 0.1N, 8.33 mL HCl 37% were slowly added over 800 ml distilled water, with intermittent shaking. Then, completed to 1000 mL with distilled water.

Buffer solution KCl-HCl (pH=2). The KCl-HCl buffer solution was prepared by adding 800 mL distilled water, 7.45 g KCl, 1.66 mL HCl 37% and completing with water till 1000 mL. The pH was adjusted with HCl or NaCl solutions to the value of 2.

Buffer phosphate (pH=4.5). For each 1000 mL of buffer solution, 6.8 g KH2PO4 were dissolved in distilled water and was completed with water till 1000 mL.

Solvent mixture H2O: propane diol (15: 85) was prepared by mixing water and propane diol in 15:85 ratio.

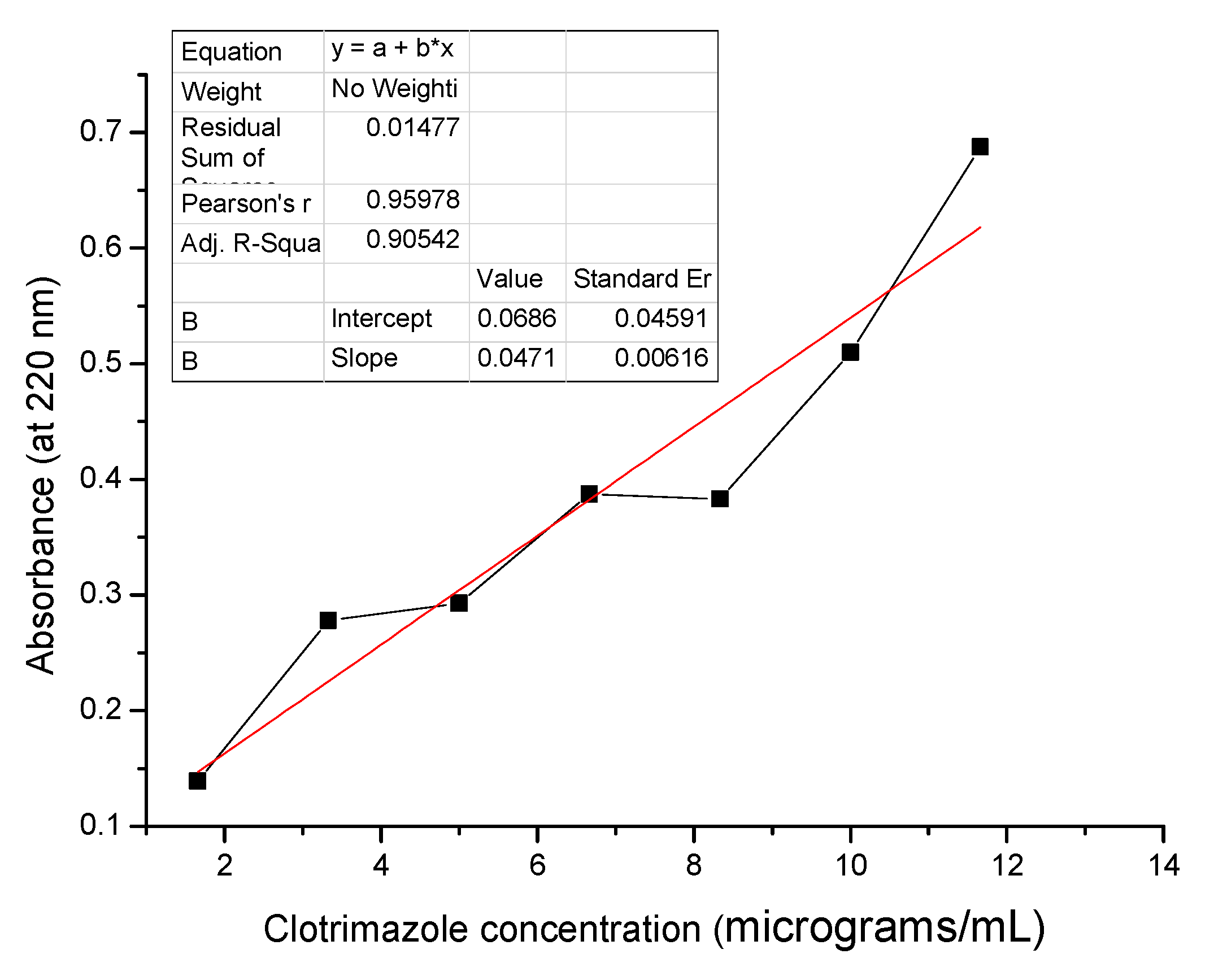

2.3.3. UV-VIS Calibration Curves

UV-VIS Calibration curves were made for linear CLZ concentrations in the different dissolution media. Analytical note (λmax and working absorbance range): when absorbance exceeded the recommended working range (0.1–1.5 AU), samples were diluted to bring readings within optimal limits and concentrations were recalculated from dilution factors—an approach consistent with best practices for UV–Vis assays [

32].

Calibration Curve for CLZ in HCl 0.1 N (pH 1)

A 0.1 M clotrimazole stock solution was prepared in HCl 0.1 N. A calibration curve for clotrimazole was set. The 0.1 M clotrimazole solution was successively diluted (in HCl 0.1 N solution) in order to reach solutions with different concentrations. The following molar concentrations of clotrimazole (1.66, 3.33, 5, 6.66, 8.33, 10 and 11.66 µg/mL respectively) and their absorbances at 220 nm (0.14, 0.28, 0.29, 0.39, 0.38, 0.51 and 0.69, respectively) were used in order to obtain the calibration curve.

Calibration Curve for CLZ in Nuffer KCl-HCl (pH 2)

A clotrimazole stock solution was prepared by dissolving 27.9 mg in 100 mL buffer KCl-HCl, pH= 2. Solutions of different concentrations of clotrimazole were prepared by dilutions from the stock solution. A calibration curve for clotrimazole was set. The following molar concentrations of clotrimazole solutions used for the calibration curves were (6.75 * 10-6, 1.35 * 10-5, 2.025 * 10-5, 2.75 * 10-5, 3.375 * 10-5, 4.05 * 10-5, 4.725 * 10-5, 5.4 * 10-5, 6.73* 10-5 and 8.1 * 10-5 mol/L, respectively and their absorbances read at 236 nm: 0.0429, 0.1029, 0.158, 0.2131, 0.2527, 0.3237, 0.3511, 0.4295, 0.5248 and, 0.6942 respectively were used to obtain the calibration curve.

Calibration Curve for CLZ in Nuffer pH 4.5

For the calibration curve, the calculations had as a reference of 100%, the concentration of 0.111 mg/mL (111 µg/mL), considered ideal for dissolving a concentration of 100 mg CLZ in 900 mL dissolution medium. A stock solution was prepared, dissolved in ethanol, for a facile dilution of 55.5 mg CLZ in 50 mL ethanol, reaching a stock concentration of 2220 µg/mL. Further, the dilutions were made with buffer pH 4.5. Second dilution of 5 mL stock solution of CLZ to final volume of 50 mL (220 µg/mL). Different concentrations of CLZ solutions were prepared. The following concentrations (11.1, 33.3, 55.5, 77.7, 88.8, 99.9, 111.1, 122.1 and 133.2 µg/mL) and their absorbances at 261 nm (0.0271, 0.0699, 0.1259, 0.1721, 0.2233, 0.2522, 0.3215, 0.4156 and 0.4957, respectively) were used to obtain the calibration curve.

Calibration Curve for Clotrimazole in H2O: Propane Diol =15: 85 Solvent Mixture

Calibration curve for clotrimazole was set in H2O: propane diol =15: 85 solvent mixture. The formulation was designed to reproduce the drug release behaviour under conditions comparable to those of the skin pH. Solutions of different concentrations of clotrimazole were prepared. The following molar concentrations of clotrimazole (9.66*10-5, 1.448*10-4, 2.17*10-4, 3.26*10-4, 4.8*10-4, 7.3*10-4, 11*10-4, 16.6*10-4, 24.8*10-4and 37*10-4mol/L respectively) and their absorbances at 261 nm wave length (0.4529, 0.4601, 0.5367, 0.5922, 0.6375, 0.7406 0.807, 0.9889, 1.265 and, 1.3526 respectively) were used in order to obtain the calibration curve.

Calibration Curves for Clotrimazole in Ethanol

Ethanol was selected as the reference solvent for assessing the linear relationship between concentration and absorbance, given its high solubilizing capacity for clotrimazole.

A clotrimazole stock solution was prepared by dissolving 0.0498 g clotrimazole in ethanol. Solutions of different concentrations of clotrimazole were prepared by dilutions from the stock solution. A calibration curve for clotrimazole was set. The following molar concentrations of clotrimazole solutions used for the calibration curves were (4.8 * 10-5, 7.2 * 10-5, 8.4 * 10-5, 9.6 * 10-5, 1.2 * 10-4, 1.44 * 10-4, 1.92 * 10-4, 2.4 * 10-4, 2.88 * 10-4 and 4.8 * 10-4 mol/L, respectively and their absorbances read at 253 nm: 0.2139, 0.2944, 0.344, 0.4157, 0.5025, 0.6114, 0.8084, 1.0089, 1.1849 and 1.4947, respectively, were used to obtain the calibration curve.

2.3.4. Drug Loading Experiments

Drug loading experiments were done using a classical soaking method, and the filtrate was dose spectrophotometrically for CLZ quantification, at the highest absorbance required after the full spectrum of the absorbance of CLZ in different media. Whenever the absorbance values were above the recommended analytical range of 0.1–1.5, the samples were appropriately diluted to ensure accurate quantification, and the concentrations were subsequently corrected based on the applied dilution factors. For all drug loading experiments 0.2 g silica material as carrier, have been used in all cases.

Drug Loading in HCl 0.1 N Solution (pH 1)

A classic procedure for loading was used, by soaking 0.2 g of carrier material with 10 mL of HCl 0.1 N solution (containing 0.1g CLZ) under continuous stirring for 24 hours. The drug loaded material was filtered and dried at room temperature for 24 hours. The filtrate was dose spectrophotometrically (at 220 nm) to quantify the clotrimazole substance entrapped into the matrix (the filtrate volume was measured). The solid material was then used for in vitro drug release.

Drug Loading in KCl- HCl Buffer Solution (pH 2)

The same procedures were used for loading CLZ in KCl-HCl buffer solution (pH=2) and the filtrate was dose spectrophotometrically (at 261 nm). Only for this particular solvent besides the 10 mL volume of entrapment, also the 50 mL entrapment volume was evaluated for M2 carrier entrapped in triplicate, therefore for 3 resulted carriers.

Drug Loading in Ethanol Solution (For the Samples That Were Further Released in Buffer of pH = 4.5

A classic procedure for loading was used by soaking 0.2 g of carrier material with 10 mL of ethanol solution (containing 0.1g clotrimazole) with continuous stirring for 24 hours. Then, the drug loaded material was filtered and dried at room temperature for another day. The filtrate was dose spectrophotometrically (at 253 nm) for CLZ entrapped into the matrix.

Drug Loading in H2O: Propane Diol =15: 85 Solvent Mixture

Standard procedures were used for loading CLZ in the H2O: propane diol =15: 85 solvent mixture and the filtrate was dose spectrophotometrically (at 261 nm).

Drug loading calculations

The loading efficiency (%) and the loading capacity (mg/g) were calculated and the results for loading efficiency (%) are presented in

Table A1 Appendix 1 and the loading capacity (mg/g) in Appendix 1.

2.3.4. In Vitro Drug Release Procedures Were Done in Two Ways: Classic Laboratory Experiment and Using Suitable Dissolution Apparatus

In vitro drug release procedure using classical method

The drug-loaded carrier was soaked in a beaker filled with 200 mL hydrochloric acid solution 0.1 N. The experiments were performed at room temperature under stirring. Periodically (every 5 min in the first 130 min; every 30 min in the next 3 h and the next day, after 23.25 h), a 3 mL sample was removed for analysis and replaced with another 3 mL of fresh acidic buffer solution. The 3 mL samples were filtered before spectrophotometric analyses.

To mimic in vitro pH conditions of the skin, drug release tests were performed in a H2O:1,2-propanediol=15:85 solution. The drug-loaded carrier was soaked in a beaker filled with 100 mL solution. The experiments were performed at room temperature under stirring. Periodically (every 5 min in the first 130 min; every 30 min in the next 3 h and the next day, after 23.25 h), one mL sample was removed for analysis and replaced with another mL of fresh acidic buffer solution. One simple mesoporous silica (MCM-41) and M1 loaded with clotrimazole were evaluated.

In vitro Drug Release Procedure Using the Dissolution Apparatus 850-DS Model from Agilent in Paddle Module

Drug release tests were performed in different acid buffered solutions: pH=2 and pH=4.5.

Dissolution parameters included: 900 mL media volume, 37 °C, 200 rpm, 3.5 mL sampling volume with the same 3.5 mL media replacement, with an automated system. Sampling times are: 5 min, 10 min, 15 min, 20 min, 30 min, 40 min, 50 min, 1h 20min, 1h 50 min, 2h 20 min, 2 h 50 min, 3h 20 min. Sample solution was filtered.

The 3 mL samples were spectrophotometrically analysed. The same protocol was applied for all samples where the dissolution instrument has been used, except three carriers (see the table) where the instrument accidentally stopped working but the experiment was continued afterwards, therefore the release time was longer 5.66 hours instead of 3 hours and 20 minutes.

Using this release procedure, first the pure clotrimazole was evaluated in triplicate for the release as well as the loading in herb caps (in triplicate), therefore all six for the release in buffer pH=2. Different carriers were tested as follow:

Three carriers (one simple mesoporous silica MCM-41, and M1 and M2) loaded in H2O:1,2-propanediol=15:85 were evaluated for the release in buffer pH=2.

Six M1 carriers loaded in triplicate from ethanol and in triplicate from pH 2 buffer were evaluated for dissolution drug release in pH2 buffer.

Six M2 carriers loaded in triplicate from ethanol and in triplicate from pH 2 buffer were evaluated for the release in pH 2 buffer.

One simple mesoporous silica (MCM-41), M1 and M2 carriers, loaded in ethanol were evaluated for drug release in pH 4.5 buffer.

Therefore, this resulted in a total of 33 loading and release experiments.

3. Results

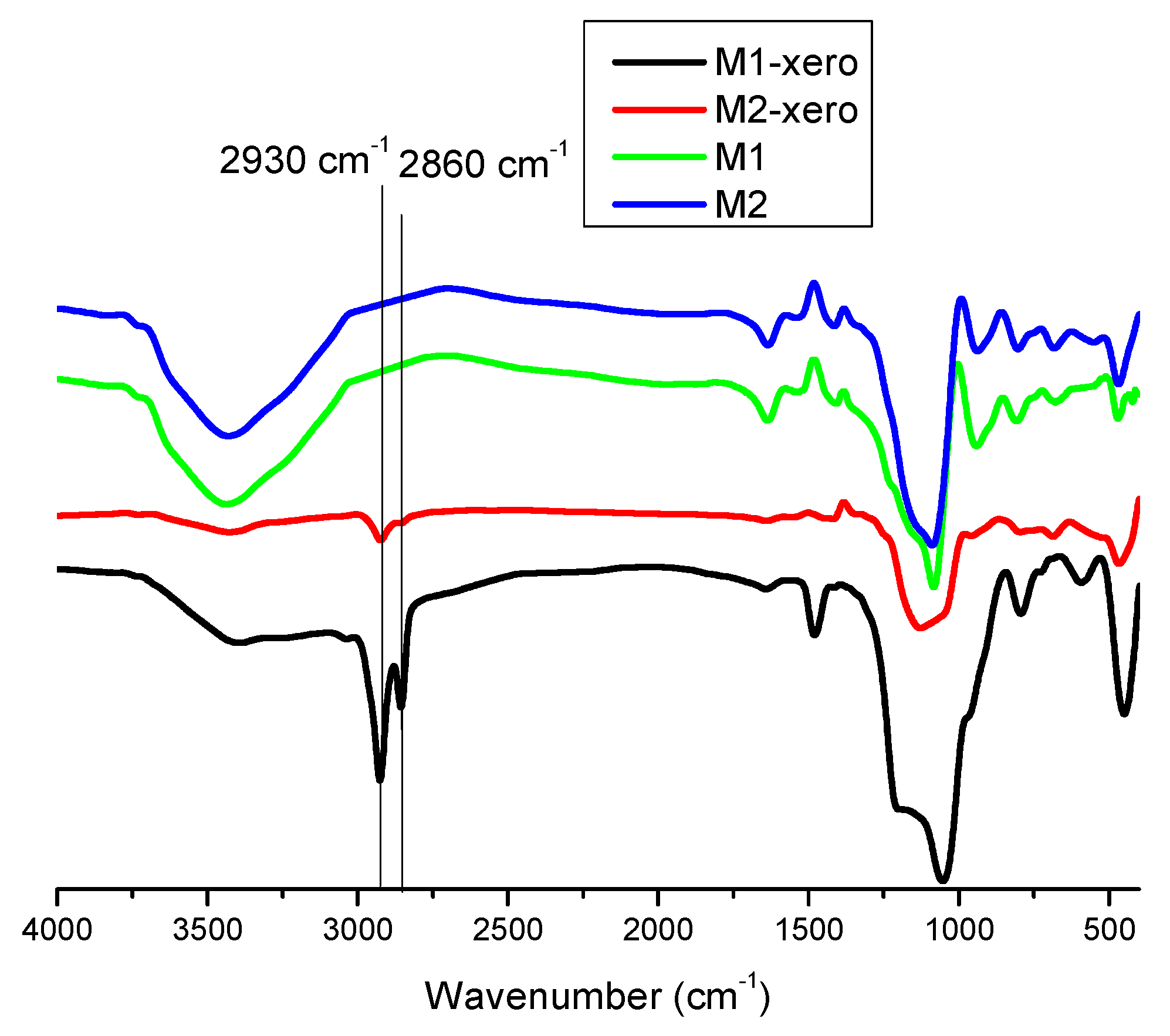

3.1. FT-IR Analysis

FT-IR (Fourier-transform infrared) spectra, presented in

Figure 1, indicate that the xerogel structure has successfully formed, including after removal of the directing agent. All samples show the specific vibration bands assigned to the silica skeleton around 1050, 800, and 450 cm

−1, corresponding to the asymmetric stretching, symmetric stretching, and bending vibration of the Si-O-Si network, respectively [

33].

The presence of the silanol groups were confirmed by the existence of the band centered at about 960 cm

−1, which is associated with the stretching mode of the Si-OH groups [

34]. The characteristic vibration bands of the methylene group in the surfactant molecules and functionalized precursor are observed around 2930 cm

−1 and 2860 cm

−1 for the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations, respectively [

34]. The observation of these bandsin the samples after CTAB extraction by acidified ethanol solutions suggest that some directing agent still remains.

An important band expected at 2360 cm

-1 (assignable to the SH group from the mercaptopropyl functionalization) [

35] is not visible in this case, due to the very low concentration of the precursor containing the mercapto group compared with the rest of the reactants added in the synthesis mixture.

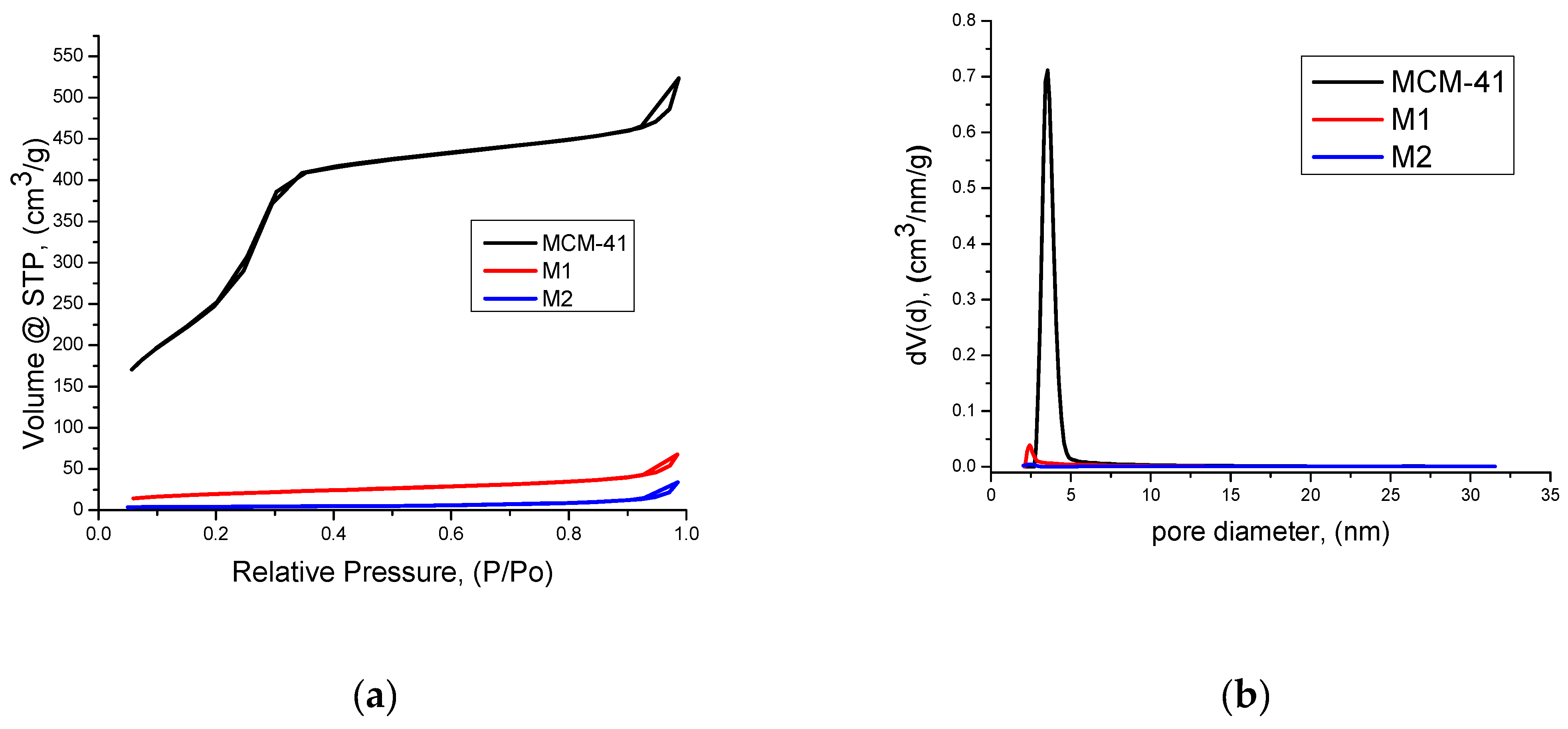

3.2. Textural Characterization by Nitrogen Sorption Method

The textural characterization by nitrogen sorption was performed for all three mesoporous materials obtained after the CTAB extraction: MCM-41, M1 and M2. N

2 adsorption-desorption isotherms,

Figure 2a, were determined by N

2-physisorption measurements at 77 K for nonfunctionalized material as well as after functionalization with mercaptopropyl. Based on the IUPAC classification, the isotherm of MCM-41 was type IVb, which is characteristic for smaller mesopores, which are closed at one end [

36,

37,

38]. The Type III isotherms observed for samples M1 and M2 indicate that the adsorbent-adsorbate interactions are relatively weak. The absence of a low-pressure shoulder confirms this finding, showing that the adsorbed molecules interact only at the energetically most favourable sites.

The structural modification effect of the increasing quantity of the mercaptopropyl functionalization can be observed by the changing shape of the hysteresis loop. The pore size distribution is presented in

Figure 2b. In the case of nonfunctionalized, MCM-41 and functionalised samples M1 and M2, a unimodal pore size distribution, around 3 nm, is observed. Due to small hysteresis observed at 0.9 P/Po some macropores could be present. Concerning the textural parameters, see

Table 2, after functionalization, the specific surface area decreases from 1213 m

2/g to 72 m

2/g for M1 sample and 16 m

2/g for M2 sample respectively, the pore diameter decreases, from 3.54 to 2.4 nm and the total pore volume decrease as well, from 0.8 cm

3/g to 0.05 cm

3/g. The different textures of the materials are observed also in the surface fractal dimensions evaluated from Frenkel–Halsey–Hill (FHH) method. The FHH method is used to determine the fractal geometry and calculate their surface irregularities and porous structure [

39]. When the value of Df is 2, the material presents a surface fractal and if the value of Df is 3, the material presents a mass fractal. For all analysed samples, a mass fractal behaviour was observed, from the FHH data of

Table 2 by neglecting/accounting for Adsorbate Surface Tension.

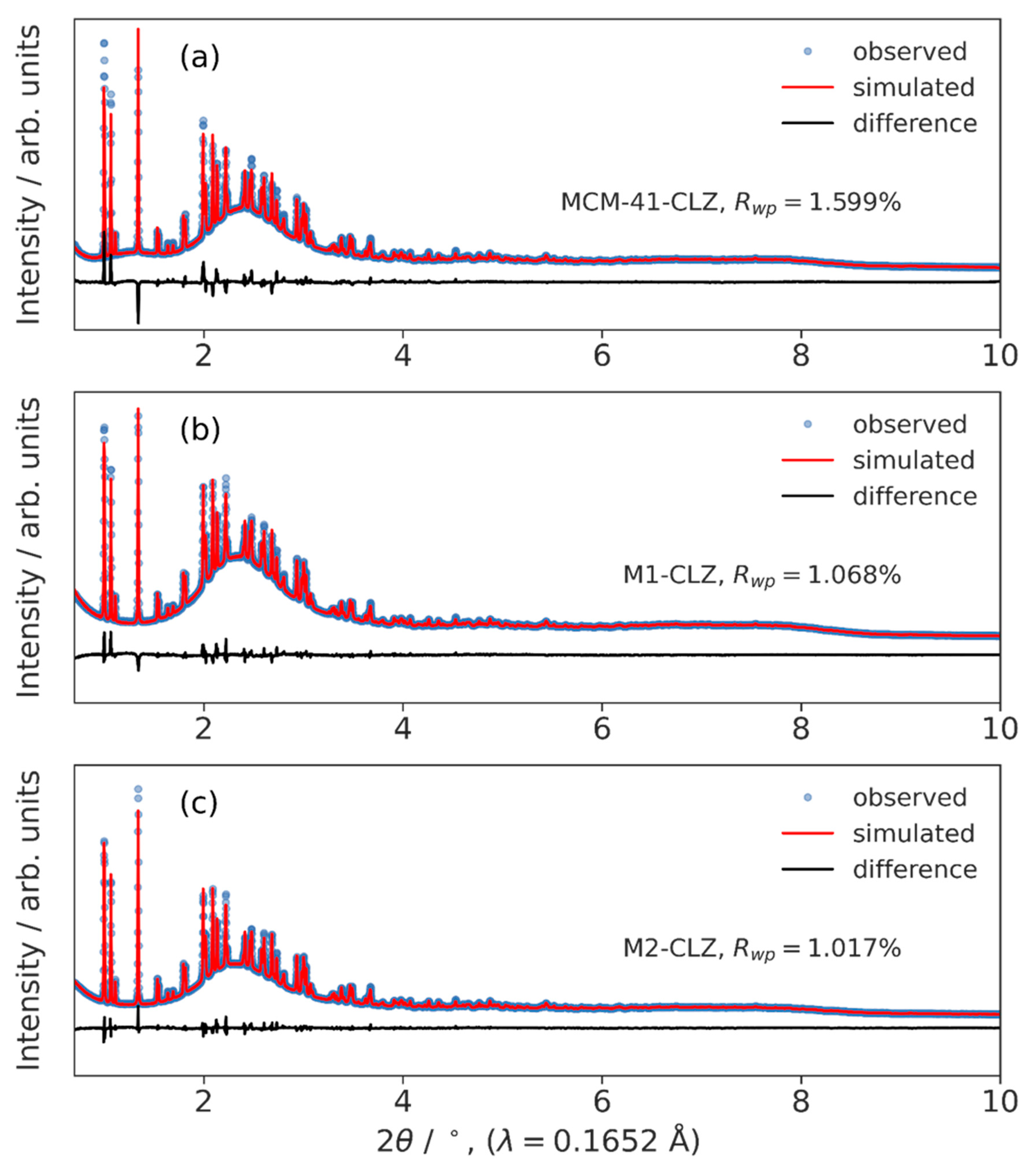

3.3. High-Resolution XRPD and Total Scattering Measurements and the Processed Pair Distribution Functions

In order to confirm the presence and corresponding state of CLZ in the functionalized samples, we inspected the high-resolution XRPD patterns. Sharp Bragg reflections were indexed using the ICDD PDF5+ database and successfully identified as the known CLZ structure (ICDD # 02-071-0743) indicating that CLZ is present in its crystalline form. Ignoring the low angle features coming from the scattering of the pores in the silica support, we could perform Rietveld refinements to the CLZ diffraction pattern over a range of 0.7–10.0° 2θ to confirm and refine the structure. The refinements included the lattice parameters, Gaussian crystallite size broadening, Gaussian & Lorentzian components for strain broadening, a single isotropic atomic displacement parameter, scale factor, rotation (✕3) and translation (✕3) parameters for the molecule constrained as a rigid body, and a background including the experimental silica pattern without CLZ, a Chebyshev polynomial function of 6th order, and a broad peak. The results are shown in

Table 3.

Note that the volume-weighted mean column length (LVol-IB), estimated from the integral breadth, does not account for any geometry correction for the crystallite size, and furthermore, is close to the observable limit for the particular setup. Therefore, these values are most reliably assessed relative to one another. The uncertainties should be interpreted as a measure of the sensitivity of the refinement model parameters, rather than absolute error, for all parameters. The fits are shown in

Figure 3.

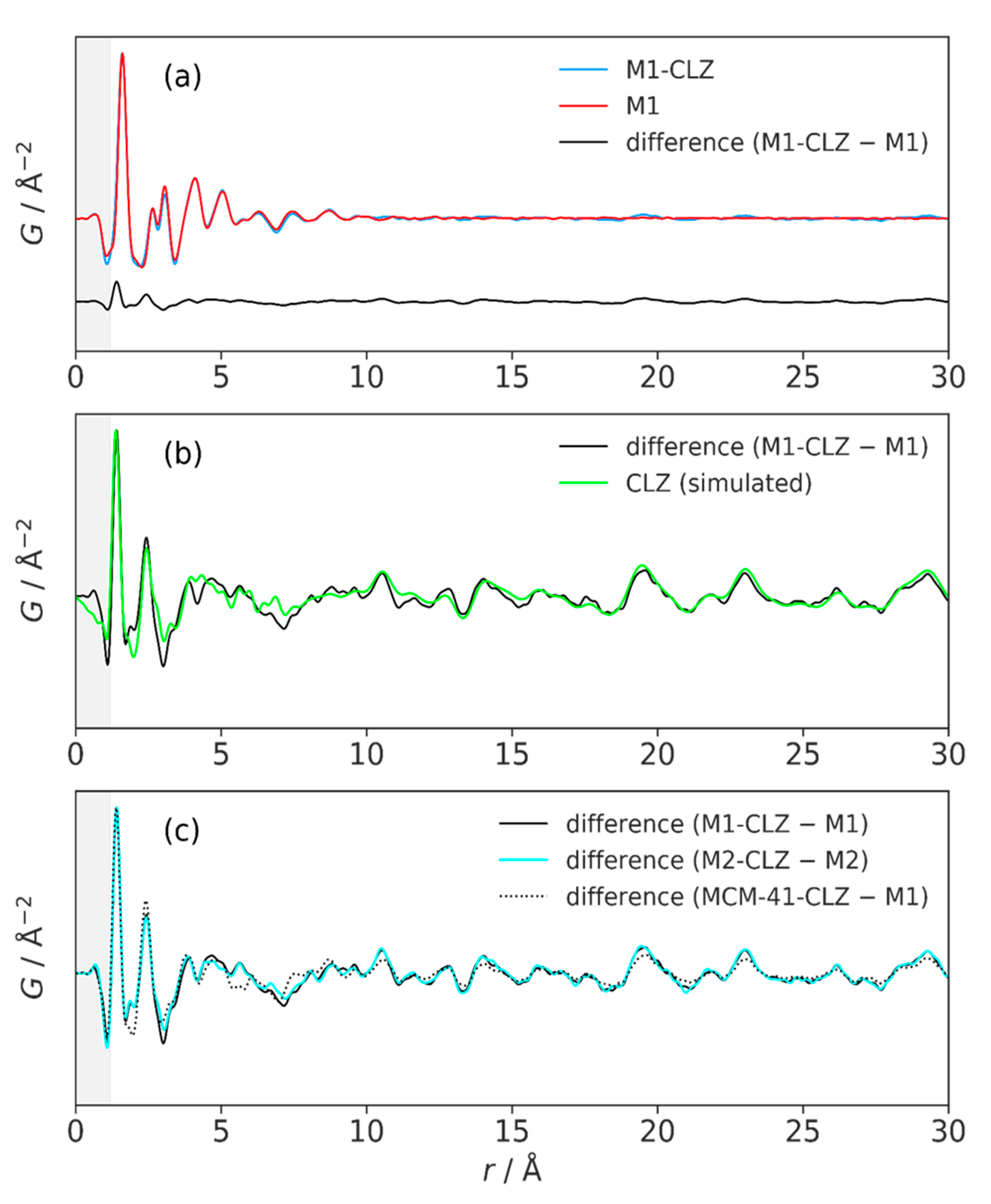

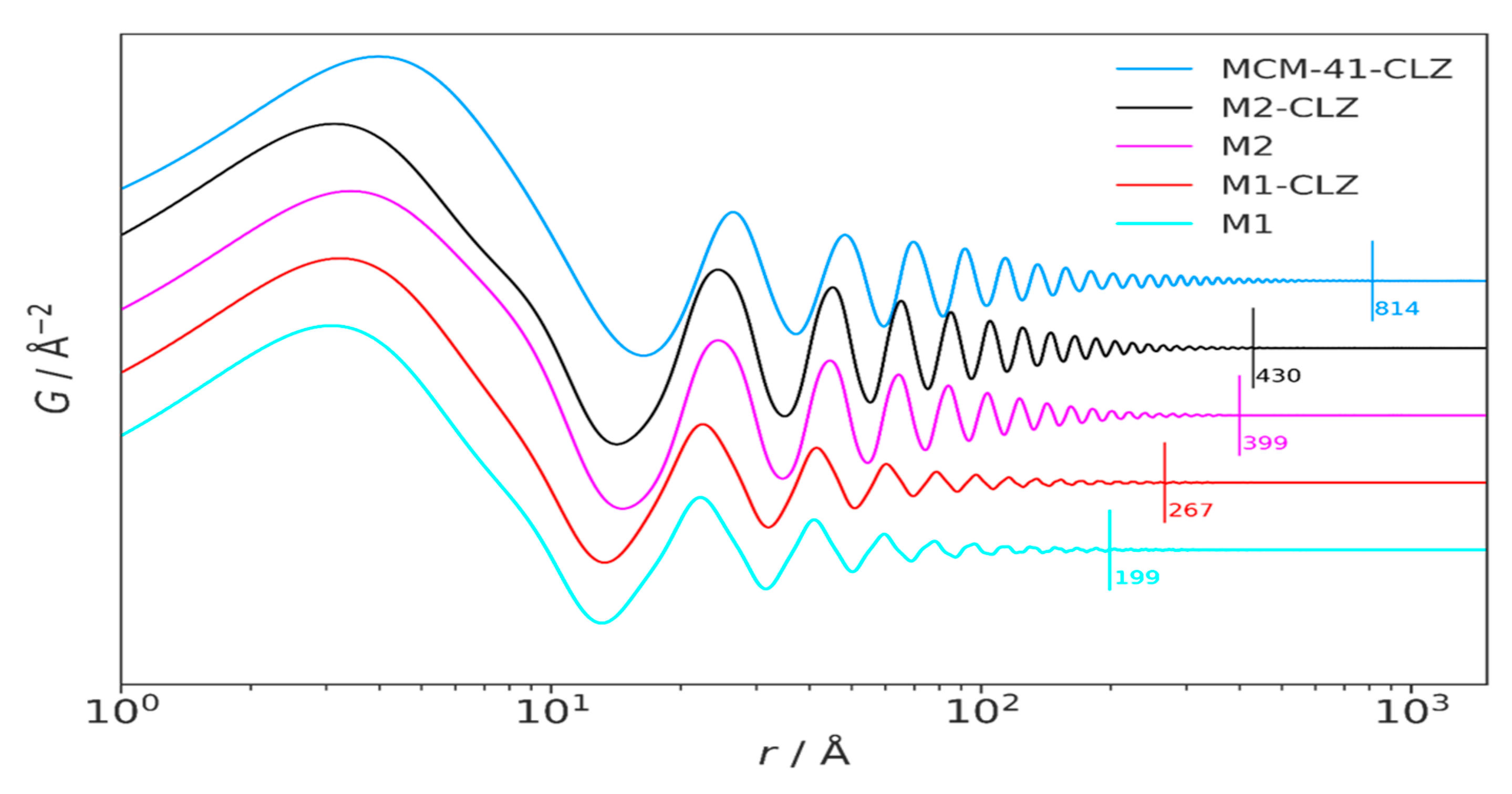

The CLZ structure was further inspected in real space using the pair distribution function (PDF) obtained from the total scattering measurements,

Figure 4. To extract the CLZ signal in real space, the pure silica reference PDFs were subtracted from the loaded silica PDFs after normalization by the Si–O peak intensity located at approx 1.6 Å. A successful subtraction was confirmed by the distinct peak remaining at approximately 1.5 Å corresponding to the CLZ molecule. The CLZ fingerprint could be confirmed by simulation of the PDF from the crystal structure using the Diffpy-CMI package [

40]. Using the same process for each sample shows that there are not major changes to the local structure of CLZ between the different support materials (Note: apparent differences with the MCM-41-CLZ extracted signal may be affected bynot having an exact MCM-41 reference, or by differences inthe other molecules used in synthesizing the materia).

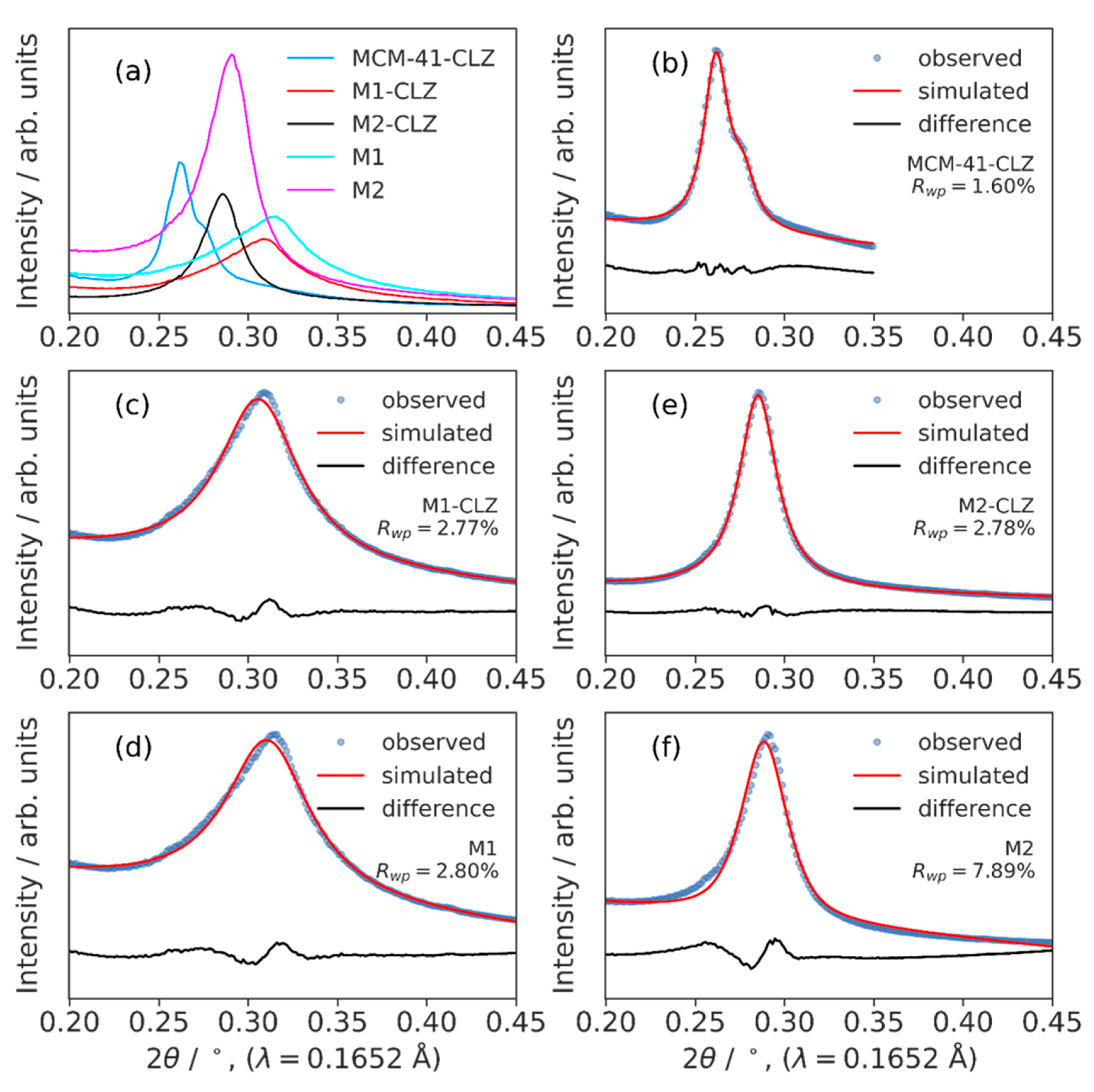

Next, we investigate the structure of the silica support materials by analyzing the small-angle scattering signals observed in the range of approximately 0.2–0.45° 2θ. The patterns are compared in

Figure 5(a). In order to achieve a relative normalization of the scattering intensities, the patterns were normalized by the high-angle intensity where the local structure of the disordered silica material dominates. A few notable differences are observed. First, the MCM-41-CLZ shows two distinct peaks, indicating a higher degree of ordering and distinctly anisotropic structure compared to M1 and M2. Both M1 and M2 show primarily one peak, although the partial asymmetry still suggests anisotropy. M1 shows a significantly broader reflection than M2, indicating reduced structural coherence. The different peak positions for each support material show that the characteristic spacing of the pores is different. Finally, we observe a decrease in the relative intensity of the low angle peak after loading CLZ for both M1 and M2, which suggests that CLZ has been incorporated into the pores creating a reduction in scattering contrast. We do not attempt to compare the relative intensities between different supports in this case, since not all possible contributions are accounted for including the structure, dimensionality, and other additives. All peaks were fitted by a single peak model, except for MCM-41-CLZ with two peaks, to extract the positions and peak breadths for further analysis. The fits are shown in

Figure 5(b–f). The results are shown in

Table 4.

Due to the peak asymmetry, the values resulting from the fits can be expected to produce lower quantitative reliability. Therefore, we also tried quantifying the mesostructural coherence in real space by Fourier transforming the small-angle scattering signals using the same formalism as for the atomic PDF. The result is a damped sine wave that shows the characteristic oscillation between pore and framework density, while the damping corresponds to the coherence length. We estimated the mean coherence by determining the point at which the maxima of the sine wave dip below 0.1% of the maximum signal, similar to the method used by Gesing et al.l. [

41].

The results are shown in

Figure 6.While the values vary slightly between reciprocal and real space estimation methods, they consistently reveal that the structural order of the supports decreases from MCM-41 to M2 to M1. Also, incorporation of CLZ consistently leads to larger characteristic pore spacing and increased coherence length, which is another indication of uptake into the pores.

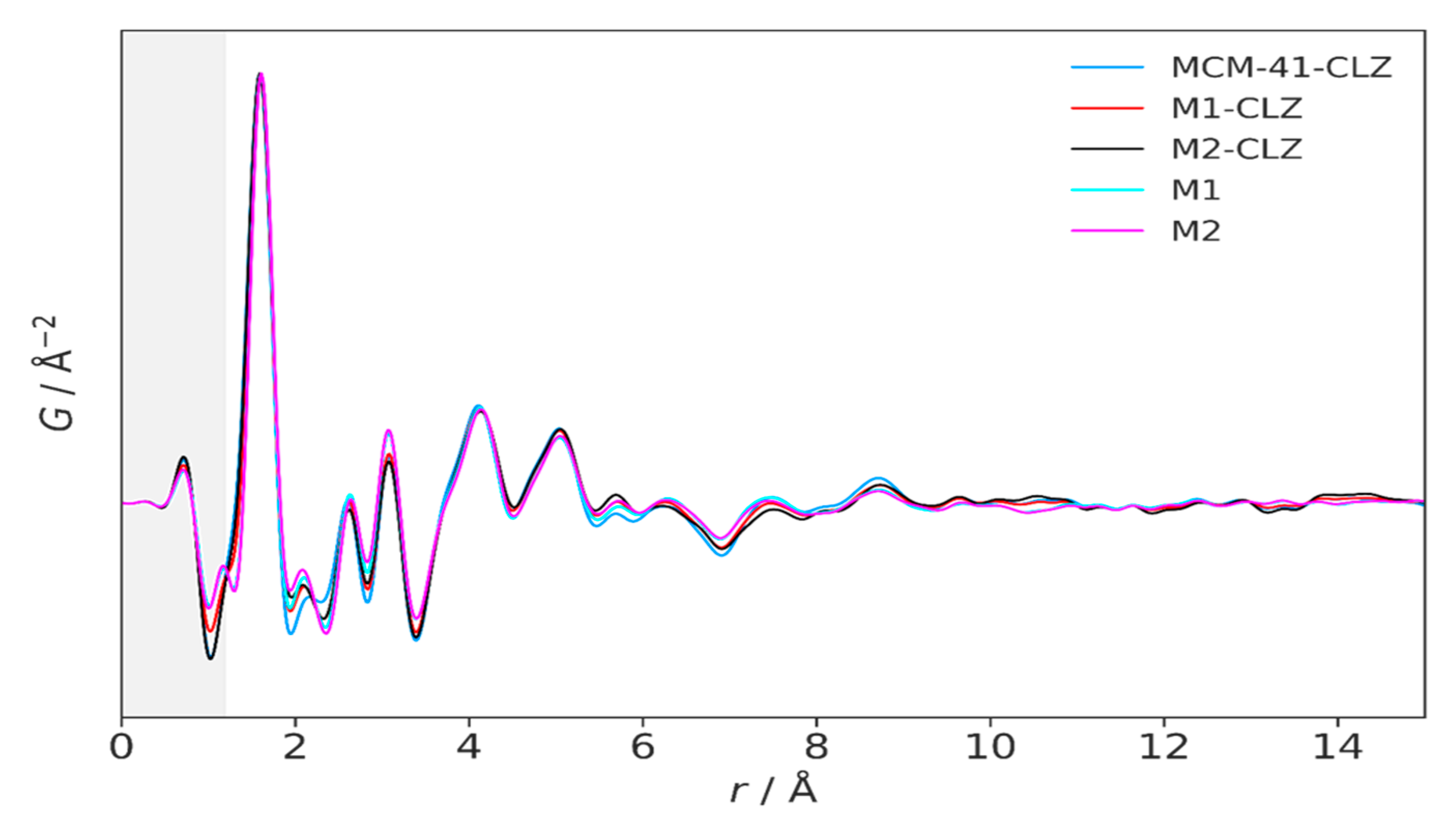

Finally, we checked whether there is any significant change in the local order of the supports. Since the PDF is dominated by the signal of the support in all cases, we simply compared the signals across all samples without additional subtractions. There are no substantial changes in the local structure, confirming that all support materials consist of disordered silica-type local structures with coherent local atomic structuring existing on the order of about 1.5 nm. The comparison is shown in

Figure 7.

3.4. Application of the Obtained Materials as Drug Carriers

The resulting 33 loading and release experiments, by using either classical or dissolution apparatus release procedures, are presented in

Table 5. The carrier loaded with CLZ is denoted as “Carrier name-CLZ” and with r1, r2 and r3 respectively, if the loading was performed in replicates where r1, r2 or r3 represents the number of the entrapped replicas.

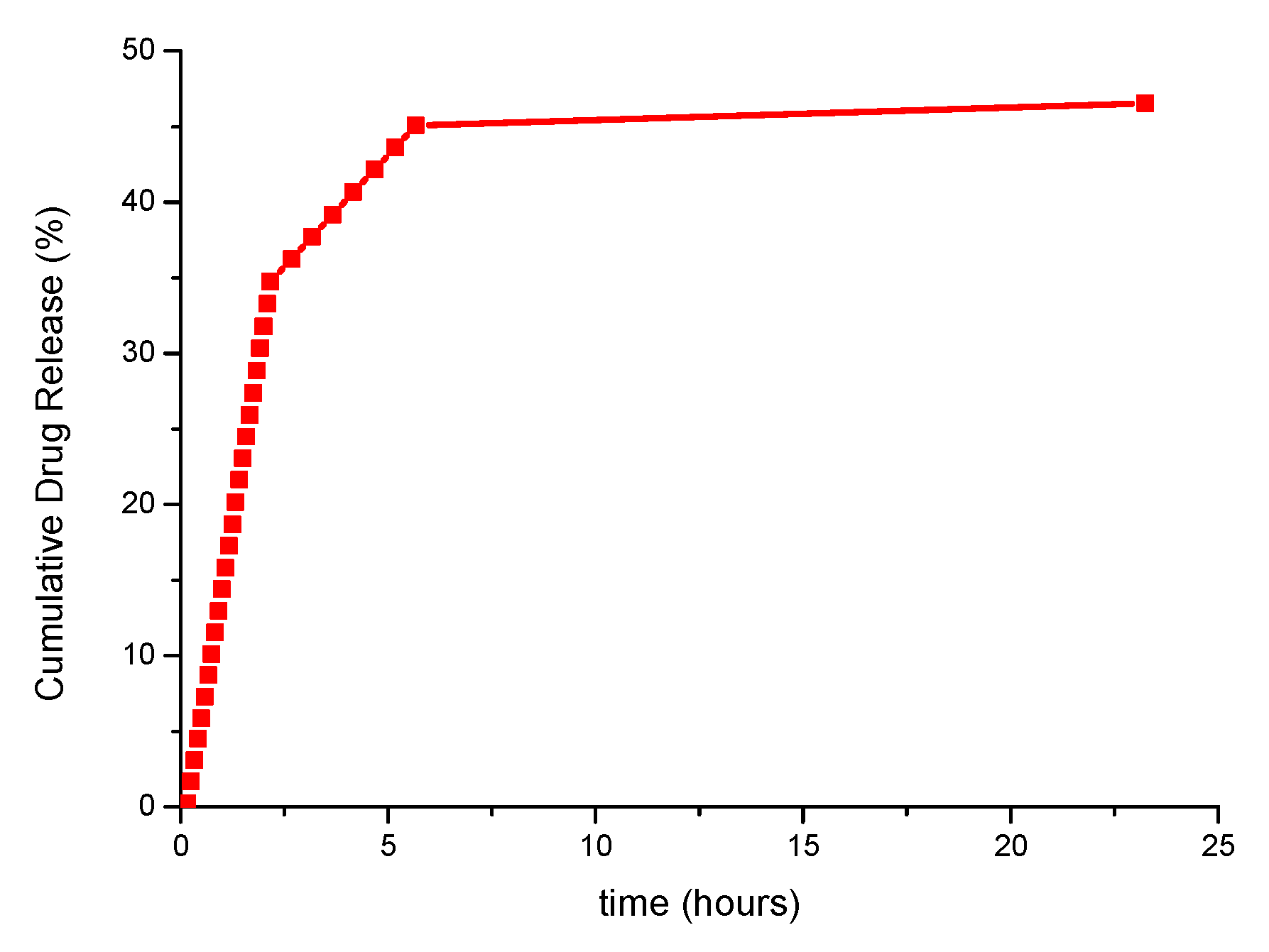

A cumulative drug release is presented in

Figure 8, for example.

In the first five hours, a constant and relatively rapid release of approximately 45% of clotrimazole was observed, following an initial burst within the first hour. Subsequently, even though the experiment was extended to 25 hours, only a minimal additional amount of drug was released during the remaining 20 hours. This behaviour suggests that the carrier provides an initial rapid dose, followed by a sustained and nearly constant release, maintaining drug availability for up to 25 hours.

To gain further insight into the release mechanism, several mathematical kinetic models were applied, each describing different potential diffusion and release processes. The kinetic model was fitted primarily to the first hour of release, where the most pronounced changes occurred. The calculated determination coefficients (R²) are summarized in

Table A2 (

Appendix A). Among the tested models, the Higuchi model provided the best correlation, indicating that the drug release in acidic medium follows a Fickian diffusion-controlled mechanism.

The release experiments were conducted for two representative carriers, MCM-41 and M1. Despite extending the analysis up to 25 hours, spectrophotometric evaluation revealed that a substantial fraction of the drug was released within the first five minutes, making further repetitions unnecessary for the third carrier. The remaining loaded samples were instead evaluated in alternative buffer media and subjected to structural characterization (XRD) for post-release analysis. Similar rapid-release behaviour has been reported in the literature for mesoporous silica carriers in comparable solvent mixtures [

42]. The use of this solvent system aimed to assess whether clotrimazole is released faster than it can penetrate the epidermis, allowing estimation of the total release timeframe—an outcome consistent with previous reports [

42].

In complementary experiments performed using a dissolution apparatus (Model 850-DS, Agilent), all carriers loaded from ethanol exhibited very limited drug release, reaching a maximum of ~16%. In contrast, when the same buffer medium was used for both drug loading and release (regardless of the loading volume, 10 or 50 mL), the release efficiency markedly increased, reaching 90–100% after 3 hours and 20 minutes. For MCM-41, M1, and M2 carriers loaded from ethanol and evaluated in pH 4.5 buffer, drug release remained low, with a maximum of 20% observed for the MCM-41 sample—consistent with the general trend of reduced release following ethanol-based loading.

4. Discussions

Clotrimazole, a broad spectrum less toxic imidazole antifungal agent, is widely used to treat candidiasis. It acts by inhibiting cytochrome14-demethylase enzyme of the fungal cells responsible for cell wall synthesis [

43]. Chemically, clotrimazole is 1-((2-chlorophenyl) diphenylmethyl)-1H-imidazole, insoluble in water (0.49 mg/L) with Log P of 6.1 and pKa 6.7 [

44,

45,

46].

Concerning the zetapotential, in the case of simple mesoporous silica particles, the Zeta potential steeply decreases after pH = 4.0 with the isoelectric point being between pH = 4.0–5.5, which is characteristic to amorphous silica materials [ 47]. The incorporation of the mercaptopropyl groups increases the basicity of the silica xerogels, which is reflected in the pH dependence of the Zeta potentials of the functionalized samples. The Zeta potential of the mercaptopropyl functionalised sample in the same amount as the M1 sample from the current study, starts decreasing only above pH =7.0. Until this point the Zeta potential of the functionalized xerogel is highly positive and the isoelectric point of the functionalized xerogel is ca. pH = 8.7 [

48].

Clotrimazole is the first oral azole approved for fungal infections; however, it is not used as an oral agent due to its limited oral absorption and systemic toxicity. Therefore, clotrimazole must be loaded into a suitable drug delivery system to enhance its topical bioavailability at the infection site. It is reported in the literature that clotrimazole has been loaded into various novel drug delivery systems such as nanogels, microemulsions, solid lipid nanoparticles, nanocapsules, ethosomes, three-dimensionally structured hybrid vesicles, and liposomes [

1,

43,

49,

50].

Gignone et al. observed that using as carriers hexagonally ordered silica for loading of clotrimazole, a 34% percent by weight loading obtaining by using the supercritical CO

2 loaing method, so next the drug release in acidic or basic buffer solutions could be evaluated [

21]. The maximum absorption band of clotrimazole in acetonitrile was found to be at 238 nm [

51]. Clotrimazole was loaded into mesoporous silica through supercritical CO

2 when the dissolution medium was changed from pH 3.0 to pH 6.8, the drug was rapidly and completely released [

21].

4.1. Sample Synthesis

Mesoporous silica supports were successfully synthesized via a sol–gel approach using CTAB as the structure-directing agent and tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) as the silica precursor. For the functionalized samples,

3-mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane (MPTS) was introduced to obtain thiol-modified frameworks (M-1 and M-2 series). The synthesis parameters are summarized in

Table 1, which includes the reagent ratios for both xerogel precursors (M-1-xero, M-2-xero) and the final calcined or functionalized materials (M-1, M-2, and MCM-41 reference). After template extraction and drying, the materials were obtained as white powders with high porosity and narrow pore-size distribution. The use of acidified ethanol during the template removal proved efficient for CTAB elimination while preserving the ordered mesostructure. Similar strategies have been described in literature for functionalized silicas [

52,

53].

The incorporation of MPTS produced materials with surface thiol groups (–SH) capable of modulating drug–matrix interactions through weak hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces. Such functionalization has been reported to improve drug entrapment efficiency and control the release kinetics of hydrophobic compounds [

54,

55]. Moreover, the synthesis temperature (100 °C drying followed by optional calcination at 540 °C) allowed controlled removal of surfactant residues and stabilization of the siloxane framework. The MCM-41 reference sample exhibited the typical ordered hexagonal arrangement, as previously reported for CTAB-templated silicas [

56,

57].

4.2. Textural Characterization by Nitrogen Sorption Method

The structural and textural differences between the three silica matrices (MCM-41, M1, and M2) have a direct impact on the entrapment and release behaviour of clotrimazole.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption measurements (

Table 2) revealed a clear trend of decreasing specific surface area and total pore volume in the order MCM-41 > M1 > M2, with values of 1213, 72.35, and 16.06 m²/g, respectively.

This decrease reflects the partial blocking of the mesopores and the reduction in accessible surface caused by the co-condensation of mercaptopropyl groups during synthesis. Similar structural effects of surface functionalization on pore accessibility and textural properties were reported by Matadamas-Ortiz and Hudson et al. [

53,

54].

The pristine MCM-41 material exhibited the typical characteristics of ordered hexagonal mesostructures: a narrow pore distribution (BJH ≈ 3.4 nm), a total pore volume of 0.81 cm³ g⁻¹, and a relatively high fractal dimension (FHH = 2.46–2.81), indicative of a well-developed porous network. These features favor rapid solvent penetration and fast diffusion of surface-adsorbed clotrimazole molecules, leading to the high initial burst observed during in vitro release testing (≈ 98–100% within 1 h in 0.1 N HCl). Comparable behaviours for unmodified MCM-41 loaded with hydrophobic drugs have been reported by Zhou

et al. (2018) and Gignone

et al. (2014) [

21,

32].

In contrast, the M1 and M2 matrices, synthesized through partial surface modification with –SH groups, displayed drastically lower surface areas (72.35 and 16.06 m²/g) and total pore volumes (0.10 and 0.05 cm³/g).

This reduction is accompanied by slight increases in micropore area (13.95 m² g⁻¹ for M1; 7.94 m² g⁻¹ for M2) and changes in pore width (BJH ≈ 3.1–6.5 nm; DFT ≈ 2.4 nm). Such alterations suggest partial structural collapse and formation of narrower, tortuous channels. Previous studies have shown that functionalization or pore shrinkage decreases drug diffusivity within mesoporous networks, resulting in more sustained release profiles [

54,

55].

The observed slower release from M1 and M2 (14–46% over 1–23 h, depending on medium) therefore correlates with the reduced pore diameter and total pore volume, the presence of organic moieties partially obstructing the channels, and enhanced hydrophobic interactions between clotrimazole and the thiol/silanol groups on the internal surface. Hydrophobic drugs such as clotrimazole (log P ≈ 6) exhibit affinity for weakly polar –SH and –SiOH domains, which delays desorption and diffusion [

32]. In addition, the fractal dimension (FHH) values decreased progressively from 2.81→2.73→2.59, suggesting increasing surface irregularity and tortuosity that further hinder molecular diffusion. A similar link between pore tortuosity and mean dissolution time has been observed for other azole–silica systems [

21,

58].

Altogether, these findings confirm that textural confinement and surface chemistry govern the release kinetics of clotrimazole from mesoporous silica carriers. The pristine MCM-41 ensures rapid diffusion and a high burst fraction, while functionalized M1 and M2 provide sustained release through reduced porosity and stronger drug–matrix affinity. These relationships align with the broader framework, in which control of pore size, surface functionality, and hydrophobicity enables the fine-tuning of both drug loading and diffusion rates [

55].

4.3. High-Resolution XRPD and Total Scattering Measurements and the Processed Pair Distribution Functions

The incorporation of CLZ consistently leads to larger characteristic pore spacing and increased coherence length, which is another clear indication of uptake into the pores.

4.4. Application of the Obtained Materials as Drug Carriers

Entrapment efficiency in mesoporous silica carriers in this study, is demonstrated by the all silica-based systems achieving high entrapment (≈ 86–~100%), consistent with the recognized affinity of mesoporous silica for poorly water-soluble azoles. Reviews on mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) emphasise that the large surface area and ordered pore network enable high payloads and efficient immobilization of hydrophobic drugs [

32]. For clotrimazole (CLZ) specifically, incorporation into ordered mesoporous silica has been reported with substantial loadings (via supercritical CO₂; up to ~34% w/w) [

21].

The release behaviour versus medium and solvent analyses, starts with rapid CLZ release from the MCM-41-CLZ sample in 0.1 N HCl (≈ 99% at 1 h), whereas the M1/M2 formulations provided sustained profiles (≈ 14–46% over 1–23 h), indicating effective diffusional control by the modified matrices. Such medium-dependent modulation and the possibility to tune burst versus sustained release by pore architecture/functionalisation are widely documented for MSNs [

55].

Switching to KCl–HCl buffer pH 2, silica-based systems in our work, typically reached ~60–90% within 3–5.7 h, while pure CLZ approached complete release (~95–100% within 3 h 20 min). The faster dissolution of neat CLZ (or of systems lacking diffusional barriers) compared with silica-confined drug mirrors prior observations that matrix-free or solubilised CLZ releases quickly, whereas mesoporous hosts retard diffusion and mitigate burst [

32].

Formulations prepared from ethanolic solutions in our dataset exhibited the slowest release (≈ 6–18% at 3 h 20 min or 5.66 h), plausibly due to a denser drug distribution within the pores and stronger hydrophobic interactions after ethanol-assisted deposition. Comparable solvent-history effects on distribution within MSNs and their impact on early-time release have been discussed in the mesoporous delivery literature [

55].

Conversely, experiments in propanediol–water (15:85 v/v) yielded very fast release (≈ 90–99% within 5 min). This aligns with independent clotrimazole solubility studies showing that propanediol (1,2-propanediol)–water cosolvent systems markedly increase CLZ solubility and hence apparent release/dissolution rate. The thermodynamic and model-based analysis of CLZ in PG–water confirms strong co-solvency, explaining our rapid liberation in PG-containing media [

59].

Analysing carrier-dependent differences, reveal in our series that the M1-type carriers showed slightly higher release than M2, demonstrating that the functionalisation in lower amount is more efficient compared with higher amount of mercaptopropyl group, whereas MCM-41 showed the highest initial burst under acidic conditions. This pattern is compatible with literature linking pore size, connectivity, and surface functionalisation to the balance between burst and sustained fractions: larger or less confined pores (or weaker drug–surface affinity) typically elevate early release, while tighter confinement and stronger interactions promote sustained profiles [

55]. Reports on CLZ in ordered mesoporous silicas (e.g., MSU-H/MCM-type) also describe that tailoring pore architecture or using supercritical CO₂ processing can shift loading distribution and thereby the early-time kinetics, consistent with our comparative trends across carriers [

21].

Although clotrimazole is primarily intended for topical administration, its release from silica matrices was also investigated under acidic conditions (0.1 N HCl and KCl–HCl buffer, pH ≈ 2) to assess the stability and diffusion behaviour of the carrier systems in environments that maintain the mesoporous framework.

Silica materials are known to exhibit limited structural stability in alkaline media, where silicate dissolution and loss of pore ordering can occur, whereas acidic conditions preserve the integrity of the silica network and enable reproducible kinetic evaluation [

32,

53].

Furthermore, the hydrophobic nature of clotrimazole (log P ≈ 6) restricts its solubility in aqueous or neutral environments [

59]. Testing the release in low-polarity or mildly acidic media therefore allows the intrinsic diffusion and interaction of the drug within the silica pores to be revealed, independent of full dissolution. Similar approaches have been employed for mesoporous silica–based systems incorporating hydrophobic antifungal agents and steroids to decouple drug–matrix interactions from solubility effects [

21,

55]. While these acidic-release tests are primarily mechanistic, the pH 4.5 buffer remains the most physiologically relevant medium, corresponding to the microenvironment of skin and vaginal mucosa, where clotrimazole topical formulations exert their therapeutic effect [

60]. Hence, combining release studies at both acidic and near-physiological pH provides a comprehensive understanding of the structural stability, drug–matrix affinity, and diffusion dynamics of thiol-functionalized silica carriers.

Overall, these mechanistic insights underline the potential of the synthesized thiol-functionalized mesoporous silica matrices as robust platforms for the controlled delivery of hydrophobic antifungal drugs, such as clotrimazole, under physiologically relevant pH conditions.The dual investigation—combining acidic environments (to probe structural stability and diffusion mechanisms) with mildly acidic buffers (to mimic skin and mucosal pH)—provides a comprehensive understanding of both the physicochemical robustness of the carriers and their practical applicability in topical formulations.

This integrated approach confirms that structural and chemical tuning of silica surfaces (via mercaptopropyl functionalization) can effectively balance high drug loading with sustained, pH-sensitive release, paving the way for targeted local therapies with reduced systemic exposure.

Future studies should aim to broaden the surface functionalization of silica carriers and to evaluate their biocompatibility and antifungal performance under conditions simulating topical or mucosal application will help confirm the practical potential of these matrices as versatile platforms for the controlled delivery of hydrophobic drugs.

5. Conclusions

A simplified sol–gel approach was successfully developed for the preparation of thiol-functionalized mesoporous silica carriers, using co-condensation of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and (3-mercaptopropyl)trimethoxysilane (MPTMS) under mild, base-catalyzed conditions. The resulting materials exhibited well-defined porous structures and were comprehensively characterized in terms of their textural properties.

When evaluated as drug delivery carriers for clotrimazole (CLZ), the functionalized silicas demonstrated very high loading efficiency (≈99%), regardless of the solvent system employed for impregnation. The release behaviour of the CLZ-loaded carriers was subsequently assessed in several dissolution media with distinct pH values.

In 0.1 N HCl, the cumulative drug release reached approximately 45% after 6 h, confirming the sustained release potential of the functionalized matrices compared to the non-modified MCM-41. The highest and most reproducible release was obtained when the same medium was used both for drug loading and for release testing. In the acidic buffered solution (pH = 2), cumulative release values ranged between 51–91% after 3 h, while in the mildly acidic buffer (pH = 4.5), the release remained within 11–20% in the same time interval.

These results highlight the strong influence of the solvent and pH environment, as well as of the textural and chemical properties of the silica matrices, on the overall release kinetics of clotrimazole. The combination of high entrapment efficiency and pH-dependent, sustained release profiles confirms the potential of thiol-functionalized mesoporous silica carriers as promising platforms for controlled topical or mucosal drug delivery applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-M .L. ; methodology, A.-M .L., D.H. and M. T.; validation, A.-M .L.; formal analysis, R.N.; investigation, R.N., D.R.; D.H., C.I., M. T. and A.-M .L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-M .L. and D.H.; writing—review and editing, A.-M .L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Project No. 4.2, from the “Coriolan Drăgulescu” Institute of Chemistry Timișoara (ICCD), Romanian Academy and the RO-OpenScreen (ICCD) infrastructure. We gratefully acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities and Momentum Transfer for facilitating the measurements. Jakub Drnec for his support in using beamline ID31. The measurement setup was developed with funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the STREAMLINE project (grant agreement ID 870313). Measurements performed as part of the MatScatNet project were supported by OSCARS through the European Commission’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme, under grant agreement No. 101129751.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CLZ |

Chlotrimazole |

| M1 |

Mercapto-1-“e” |

| M2 |

Mercapto-2-“e” |

| MCM-41 |

Simple mesoporous silica |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Molecular structure of clotrimazole.

Figure A1.

Molecular structure of clotrimazole.

The loading efficiency (%) and the loading capacity (mg/g) (the results are presented in

Table A1 Appendix A1) have been calculated for each material entrapment for each experiment, using the formulas:

The obtained Loading Capacity was high for all the carriers. For example 499.33 (mg drug/g of carrier).

Table A1.

Loading efficiency of drugs calculated for each experimental procedure.

Table A1.

Loading efficiency of drugs calculated for each experimental procedure.

| Carrier |

Loading Efficiency (%) |

| MCM-41-CLZ |

99.87 |

| M1-CLZ-r1 |

99.96 |

| M1-CLZ-r2 |

99.97 |

| M1-CLZ-r3 |

99.97 |

| M2-CLZ-r1 |

99.97 |

| M2-CLZ-r2 |

99.98 |

| M2-CLZ-r3 |

96.7 |

| MCM-41-CLZ-r1 |

97.85 |

| M1-CLZ-r1 |

97.77 |

| MCM-41-CLZ-r2 |

96.92 |

| M1-CLZ-r2 |

98.18 |

| M2-CLZ-r2 |

98.18 |

| CLZ-pure-r1 |

|

| CLZ-pure-r2 |

- |

| CLZ-pure-r3 |

- |

| CLZ-herba caps-r1 |

- |

| CLZ-herba caps-r2 |

- |

| CLZ-herba caps-r3 |

- |

| M1-CLZ-r1 |

98.17 |

| M1-CLZ-r2 |

97.71 |

| M1-CLZ-r3 |

98.63 |

| M2-CLZ-r1 |

99.68 |

| M2-CLZ-r2 |

99.68 |

| M2-CLZ-r3 |

99.68 |

| M1-CLZ-r1 |

87.44 |

| M1-CLZ-r2 |

86.96 |

| M1-CLZ-r3 |

86.1 |

| M2-CLZ-r1 |

13.38 |

| M2-CLZ-r2 |

15.45 |

| M2-CLZ-r3 |

11.96 |

| MCM-41-CLZ |

89.95 |

| M1-CLZ |

94.92 |

| M2-CLZ |

95.51 |

Figure A2.

An example of calibration curve.

Figure A2.

An example of calibration curve.

The in vitro release data were applied to various kinetics models to predict the drug release mechanism.

For the Zero Order Kinetic Model, the data obtained from in vitro drug release studies were plotted as cumulative amount of drug released versus time. In the First Order Kinetic Model the data obtained are plotted as log cumulative percentage of drug remaining versus time. This model is valid for water soluble drugs and for the burst like release.

In Higuchi model the data were designed as cumulative percentage drug release versus square root of time. It defines the release of drugs based on diffusion, from insoluble homogeneous matrix. This model could be valid for all released time. Korsmeyer-Peppas was a simple model known as “Power law” describing drug release from a polymeric system. Korsmeyer-Peppas model describe some release mechanisms simultaneously such as the diffusion of water into the matrix, swelling of the matrix and dissolution of the matrix. To study the release kinetics, data obtained from in vitro drug release studies were plotted as log cumulative percentage drug release versus log time. This model is valid only at small values of the released time. For the Hixson–Crowell model: Hixson and Crowell (1931) discovered that a group of particles’ regular area is proportional to the cube root of its volume. To study the release kinetics, data obtained from in vitro drug release studies were plotted as cube root of drug percentage remaining in matrix versus time. Wo-Wt (Cube Root of % drug Remaining).

Table A2.

The calculated parameter for the release kinetic of clotrimazole in acidic solution 0.1 N . The calculated coefficient of determination (R2) for the release kinetic of clotrimazole in acidic solution 0.1 N.

Table A2.

The calculated parameter for the release kinetic of clotrimazole in acidic solution 0.1 N . The calculated coefficient of determination (R2) for the release kinetic of clotrimazole in acidic solution 0.1 N.

| Kinetic model |

Zero Order |

First Order |

Higuchi |

Korsmeyer-Peppas |

Hixson–Crowell |

| Applied for the first 5.66 hours of release |

| Rel in acidic buffer |

0.85 |

0.89 |

0.94 |

0.82 |

0.88 |

| Applied for the first hour of release |

| Rel in acidic buffer |

0.99 |

0.98 |

0.85 |

0.7 |

0.98 |

References

- Manca, M.L.; Usach, I.; Peris, J.E.; Ibba, A.; Orrú, G.; Valenti, D.; Escribano-Ferrer, E.; Gomez-Fernandez, J.C.; Aranda, F.J.; Fadda, A.M.; Manconi, M. Optimization of innovative three-dimensionally-structured hybrid vesicles to improve the cutaneous delivery of clotrimazole for the treatment of topical Candidiasis. Pharmaceutics. 2019, 11, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolla, P.K.; Meraz, C.A.; Rodriguez, V.A.; Deaguero, I.; Singh, M.; Yellepeddi, V.K.; Renukuntia, J. Clotrimazole loaded ufosomes for topical delivery: formulation development and In-Vitro studies. Molecules. 2019, 24, 3139–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Wang, X.; Li, R. Dermatophyte infection: from fungal pathogenicity to host immune responses. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1285887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.M.; Eldridge, D.S.; Palombo, E.A.; Harding, I.H. Encapsulation of clotrimazole into solid lipid nanoparticles by microwave-assisted microemulsion technique. Appl. Mater. Today 2016, 5, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, F.; Gago, S.; Oladele, R.O.; Denning, D.W. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases-estimate precision. J Fungi 2017, 3, 57–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Sharma, V.; Chauhan, N.S. Chapter 11—Promising Novel Nanopharmaceuticals for Improving Topical Antifungal Drug Delivery. In: Nano- and Microscale Drug Delivery Systems, Editor: Grumezescu A.M., Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2017, pp. 197–228.

- Lertsuphotvanit, N.; Tuntarawongsa, S.; Jitrangsri, K.; Phaechamud, T. Clotrimazole-loaded borneol-based in situ forming gel as oral sprays for oropharyngeal candidiasis therapy. Gels 2023, 9, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Foley, K.A.; Versteeg, S.G. New Antifungal Agents and New Formulations Against Dermatophytes. Mycopathologia 2017, 182, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, M.; Ćirić, A.; Stojković, D. Emerging Antifungal Targets and Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2756–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimling, B.; Karolewicz, B.; Nawrot, U.; Włodarczyk, K.; Górniak, A. Physicochemical and Antifungal Properties of Clotrimazole in Combination with High-Molecular-Weight Chitosan as a Multifunctional Excipient. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska-Krych, D.; Gosecka, M.; Gosecki, M.; Urbaniak, M.; Dzitko, K.; Ciesielska, A.; Wielgus, E.; Kadłubowski, S.; Kozanecki, M. Enhanced Solubility and Bioavailability of Clotrimazole in Aqueous Solutions with Hydrophobized Hyperbranched Polyglycidol for Improved Antifungal Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 18434–18448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- StatPearls. Clotrimazole. NCBI Bookshelf. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560643/ (accessed on Nov 2025).

- Crowley, P.D.; Gallagher, H.C. Clotrimazole as a pharmaceutical: Past, present and future. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balata, G.; Mahdi, M.; Bakera, R.A. Improvement of Solubility and Dissolution Properties of Clotrimazole by Solid Dispersions and Inclusion Complexes. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 73, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravani, L.; Esposito, E.; Bories, C.; Le Moal, V.; Loiseau, P.M.; Djabourov, M.; Cortesi, R.; Bouchemal, K. Clotrimazole-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Hydrogels: Thermal Analysis and In Vitro Studies. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 454, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet-Regí, M.; Schüth, F.; Lozano, D.; Colilla, M.; Manzano, M. Engineering mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery: where are we after two decades? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 5365–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallet-Regí, M.; Colilla, M.; Izquierdo-Barba, I.; Manzano, M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery: current insights. Molecules 2018, 23, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, F.; Oo, M.K.; Chatterjee, B.; Alallam, B. Biocompatible Supramolecular Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as the Next-Generation Drug Delivery System. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 886981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzeciak, K.; Chotera-Ouda, A.; Bak-Sypien, I.I.; Potrzebowski, M.J. Mesoporous Silica Particles as Drug Delivery Systems-The State of the Art in Loading Methods and the Recent Progress in Analytical Techniques for Monitoring These Processes. Pharmaceutics. 2021, 13, 950–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, D.S.; Patrignani, G.; Rosqvist, E.; Smatt, J.H.; Orlowska, A.; Mustafa, R.; Preis, M.; Rosenholm, J.M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles facilitating the dissolution of poorly soluble drugs in orodispersible films. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 122, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignone, A.; Manna, L.; Ronchetti, S.; Banchero, M.; Onida, B. Incorporation of clotrimazole in Ordered Mesoporous Silica by supercritical CO2. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 200, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignone, A.; Delle Piane, M.; Corno, M.; Ugliengo, P.; Onida, B. Simulation and Experiment Reveal a Complex Scenario for the Adsorption of an Antifungal Drug in Ordered Mesoporous Silica. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015, 119, 13068–13079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terban, M.W.; Billinge, S.J.L. Structural analysis of molecular materials using the pair distribution function. Chem. Rev. 2021, 122, 1208–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egami, T.; Billinge, S. J. L. Underneath the Bragg peaks: structural analysis of complex materials. Pergamon Press, Elsevier, Oxford, England, 2003, 3-404.

- Ashiotis, G.; Deschildre, A.; Nawaz, Z.; Wright, J. P.; Karkoulis, D.; Picca, F. E.; Kieffer, J. The fast azimuthal integration Python library: pyFAI. J. Appl. Cryst. 2015, 48, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.A. TOPAS and TOPAS-Academic: an optimization program integrating computer algebra and crystallographic objects written in C++. J. Appl. Cryst. 2018, 51, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlton, F.; Ivashko, O.; Zimmerman, M.; Gutowski, O.; Dippel, A.C.; Jorgensen, M.R.V. A simple correction for the parallax effect in x-ray pair distribution function measurements. J. Appl. Cryst. 2019, 52, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, P.F.; Božin, E.S.; Proffen, Th. .; Billinge, S.J.L. Improved measures of quality for atomic pair distribution functions. J. Appl. Cryst. 2003, 36, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinge, S.J.L.; Farrow, C.L. Towards a robust ad-hoc data correction approach that yields reliable atomic pair distribution functions from powder diffraction data. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2013, 25, 454202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhas, P.; Davis, T.; Farrow, C.L.; Billinge, S.J.L. PDFgetX3: A rapid and highly automatable program for processing powder diffraction data into total scattering pair distribution functions. J. Appl. Cryst. 2013, 46, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, E. Neutron diffraction by germania, silica and radiation-damaged silica glasses. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 1969, 2, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Quan, G.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Niu, B.; Wu, B.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almásy, L.; Putz, A.M.; Tian, Q.; Kopitsa, G.P.; Khamova, T.V.; Barabás, R.; Rigó, M.; Bóta, A.; Wacha, A.; Mirica, M.; Ţăranu, B.; Savii, C. Hybrid Mesoporous Silica with Controlled Drug Release, J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2019, 84, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oweini, R.; El-Rassy, H. Synthesis and characterization by FTIR spectroscopy of silica aerogels prepared using several Si(OR)4 and R’’Si(OR’)3 precursors. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 919, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovnik, B.; Tisler, M. Dissociation Constants And Structure Of Ergothioneine. Anal Biochem. 1964, 9, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cychosz, K.A.; Thommes, M. Progress in the Physisorption Characterization of Nanoporous Gas Storage Materials. Engineering 2018, 4, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC technical report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnikov, E.I.; Sidorova, E.V.; Malakhov, A.O.; Volkov, V. V.; Julbe, A.; Ayral, A. Estimation of pore size distribution in MCM-41-type silica using a simple desorption technique. Adsorption 2011, 17, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.L.; Mustafa, N.N.N. Pore surface fractal analysis of palladium-alumina ceramic membrane using Frenkel-Halsey-Hill (FHH) model. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2006, 301, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhas, P.; Farrow, C.; Yang, X.; Knox, K.; Billinge, S. Complex modeling: a strategy and software program for combining multiple information sources to solve ill posed structure and nanostructure inverse problems. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesing, T. M.; Robben, L. Determination of the average crystallite size and the crystallite size distribution: the envelope function approach EnvACS. J. Appl. Cryst. 2024, 57, 1466–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, C.G. Mesoporous silicas for incorporation and release of drugs, Master of Science Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, S.S.; Lorenzoni, A.; Ferreira, L.M.; Mattiazzi, J.; Adams, A.I.H.; Denardi, L.B.; Alves, S.H.; Schaffazick, S.R.; Cruz, L. Clotrimazole-loaded Eudragit®® RS100 nanocapsules: Preparation, characterization and in vitro evaluation of antifungal activity against Candida species. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Maity, T.; Kumar, P.; Maiti, S.; Ghosh, S.; Biswas, S. Development and Characterization of Clotrimazole-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for Enhanced Topical Delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 642, 123169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, C.D. Clotrimazole. XPharm Compr. Pharmacol. Ref. 2007, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravani, L.; Esposito, E.; Bories, C.; Moal, V.L.-L.; Loiseau, P.M.; Djabourov, M.; Cortesi, R.; Bouchemal, K. Clotrimazole-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier hydrogels: Thermal analysis and in vitro studies. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 454, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, G.V. Zeta Potentials and Yield Stresses of Silica Suspensions in Concentrated Monovalent Electrolytes: Isoelectric Point Shift and Additional Attraction. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2002, 249, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, P.; Percsi, D.; Fodor, T.; Juhasz, L.; Dudas, Z.; Horvath, Z.E.; Ryukhtin, V.; Putz, A.M.; Kalmar, J.; Almasy, L. Selective and high capacity recovery of aqueous Ag(I) by thiol functionalized mesoporous silica sorbent. J. Molec. Liq. 2023, 387, 122598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Al-Janoobi, F.I.; Alzahrani, K.A.; Al-Agamy, M.H.; Abdelgalil, A.A.; Al-Mohizea, A.M. In-vitro efficacies of topical microemulsions of clotrimazole and ketoconazole; and in-vivo performance of clotrimazole microemulsion. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2017, 39, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, R.G.S.; Tekade, R.K.; Sharma, P.A.; Darwhekar, G.; Tyagi, A.; Patel, R.P.; Jain, D.K. Ethosomes and ultradeformable liposomes for transdermal delivery of clotrimazole: A comparative assessment. Saudi Pharm. J. 2012, 20, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, N.B.S.; Narayana, B. Spectrophotometric and spectroscopic studies on charge transfer complexes of the antifungal drug clotrimazole. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2017, 11, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Meng, J.; Hu, X.; Feng, R.; Zhou, M. Synthesis of Thiol-Functionalized Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Adsorption of Hg²⁺ from Aqueous Solution. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2019, 89, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matadamas-Ortiz, A.; Pérez-Robles, J.F.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Amaya-Llano, S.L.; Amaro-Reyes, A.; Di Pierro, P.; Regalado-González, C. Effect of Amine, Carboxyl, or Thiol Functionalization of Mesoporous Silica Particles on Their Efficiency as a Quercetin Delivery System in Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions. Foods 2024, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.P.; Padera, R.F.; Langer, R.; Kohane, D.S. The biocompatibility of mesoporous silicates. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 4045–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang W, Liu H, Qiu X, Zuo F, Wang B. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a drug delivery mechanism. Open Life Sci 2024, 19, 20220867. [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S.; Vartuli, J.C.; Roth, W.J.; Leonowicz, M.E.; Kresge, C.T.; Schmitt, K.D.; Chu, C.T.W.; Olson, D.H.; Sheppard, E.W.; McCullen, S.B. , Higgins, J.B.; Schlenker, J.L. A new family of mesoporous molecular sieves prepared with liquid crystal templates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10834–10843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Cui, K.; Jin, S. Temperature-Driven Structural Evolution during Preparation of MCM-41 Mesoporous Silica. Materials 2024, 17(8), 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volitaki, C.; Lewis, A.; Craig, D.Q.M.; Buanz, A. Electrospraying as a Means of Loading Itraconazole into Mesoporous Silica for Enhanced Dissolution. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, A.; Rezaei, H.; Poturcu, K.; Hanaee, J.; Jouyban, A.; Zhao, H.; Rahimpour, E. Effect of Temperature and Propylene Glycol as a Cosolvent on Dissolution of Clotrimazole. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2023, 81(2), 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin YP, Chen WC, Cheng CM, Shen Lin Y.P.; Chen W.C.; Cheng C.M.; Shen C.J. Vaginal pH Value for Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Vaginitis. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1996. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra for the obtained materials.

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra for the obtained materials.

Figure 2.

(a) Nitrogen sorption isotherms for MCM-41, M1 and M2; (b) Pore size distribution for MCM-41, M1 and M2.

Figure 2.

(a) Nitrogen sorption isotherms for MCM-41, M1 and M2; (b) Pore size distribution for MCM-41, M1 and M2.

Figure 3.

The results of the Rietveld refinements are plotted for the three CLZ loaded samples: (a) MCM-41-CLZ, (b) M1-CLZ, and (c) M2-CLZ.

Figure 3.

The results of the Rietveld refinements are plotted for the three CLZ loaded samples: (a) MCM-41-CLZ, (b) M1-CLZ, and (c) M2-CLZ.

Figure 4.

Extraction and comparison of the CLZ signals in real space using the PDF. (a) The CLZ signal is shown as the difference extracted from M1-CLZ PDF minus M1 PDF. (b) The difference signal is validated by comparison to a PDF simulated from the known CLZ structure used for Rietveld refinements. (c) The difference PDFs are compared showing similar local structure for each sample MCM-41-CLZ, M1-CLZ, and M2-CLZ. The grey highlighted region in the plots of G(r) represent the unreliable part of the low-r range due to the poly (= 1.19) value used in PDFgetX3..

Figure 4.

Extraction and comparison of the CLZ signals in real space using the PDF. (a) The CLZ signal is shown as the difference extracted from M1-CLZ PDF minus M1 PDF. (b) The difference signal is validated by comparison to a PDF simulated from the known CLZ structure used for Rietveld refinements. (c) The difference PDFs are compared showing similar local structure for each sample MCM-41-CLZ, M1-CLZ, and M2-CLZ. The grey highlighted region in the plots of G(r) represent the unreliable part of the low-r range due to the poly (= 1.19) value used in PDFgetX3..

Figure 5.

The results of the Rietveld refinements are plotted for the three CLZ loaded samples: (a) MCM-41-CLZ, (b) M1-CLZ, and (c) M2-CLZ.

Figure 5.

The results of the Rietveld refinements are plotted for the three CLZ loaded samples: (a) MCM-41-CLZ, (b) M1-CLZ, and (c) M2-CLZ.

Figure 6.

The results of the Fourier transformation of the small-angle signals and estimated mean coherence lengths.

Figure 6.

The results of the Fourier transformation of the small-angle signals and estimated mean coherence lengths.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the PDFs of the silica structures for all samples.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the PDFs of the silica structures for all samples.

Figure 8.

Cumulative drug release presented as an example.

Figure 8.

Cumulative drug release presented as an example.

Table 1.

Table Synopsis of the synthetized samples.

Table 1.

Table Synopsis of the synthetized samples.

| Nr. |

Sample name |

CTAB (g) |

TEOS (mL) |

MPTS (mL) |

| 1. |

M-1-xero |

2 |

7 |

1 |

| 2. |

M-2-xero |

2 |

7 |

2 |

| 3. |

M1 |

2 |

7 |

1 |

| 4. |

M2 |

2 |

7 |

2 |

| 5. |

MCM-41 |

2 |

7 |

- |

Table 2.

Textural parameters (*ads Neglecting / Accounting, Adsorbate Surface Tension Effects).

Table 2.

Textural parameters (*ads Neglecting / Accounting, Adsorbate Surface Tension Effects).

| Sample |

Surface area, m2/g |

Micropore

Area,

m2/g |

BJH ads, nm |

BJH des, nm |

DFT, nm |

Total pore volume, cm3/g |

FHH * |

| MCM-41 |

1213 |

0 |

3.42 |

3.44 |

3.54 |

0.81 |

2.46/ 2.81 |

| M1 |

72 |

14 |

3.10 |

3.28 |

2.43 |

0.1 |

2.19/ 2.73 |

| M2 |

16 |

8 |

4.96 |

6.49 |

2.43 |

0.05 |

1.78/ 2.59 |

Table 3.

Refined parameter values obtained from Rietveld refinement of the CLZ structure.

Table 3.

Refined parameter values obtained from Rietveld refinement of the CLZ structure.

Sample/

Refine parameters |

MCM-41-CLZ |

M1-CLZ |

M2-CLZ |

| a / Å |

8.76234 |

8.76144 |

8.76212 |

| b / Å |

10.55085 |

10.55009 |

10.55059 |

| c / Å |

10.60473 |

10.59867 |

10.59938 |

| ɑ / ° |

114.096 |

114.085 |

114.082 |

| ꞵ / ° |

96.916 |

96.925 |

96.924 |

| γ / ° |

97.582 |

97.594 |

97.601 |

| V / Å3

|

870.54 |

869.90 |

870.07 |

| LVol-IB / nm |

500 |

454 |

442 |

| e0 |

0.000759 |

0.000773 |

0.000751 |

| Rwp / % |

1.59893885 |

1.06836241 |

1.0170491 |

Table 4.

Characteristic dspacing and coherence length estimations obtained from reciprocal and real space analysis.

Table 4.

Characteristic dspacing and coherence length estimations obtained from reciprocal and real space analysis.

| |

|

MCM-41-CLZ |

M1-CLZ |

M1 |

M2-CLZ |

M2 |

| XRD |

dspacing / nm |

24.0

22.7 |

20.6 |

20.2 |

22.1 |

21.8 |

| LVol-IB / nm |

42 |

11 |

10 |

25 |

23 |

| PDF |

LVol (0.1% max) / nm |

81 |

27 |

20 |

43 |

40 |

Table 5.

Parameters of the drug entrapment and release experiments (*CLZ pure refers to active substance, the simple clotrimazole; ** CLZ herba caps, refers to vegetable capsules containing pure clotrimazole).

Table 5.

Parameters of the drug entrapment and release experiments (*CLZ pure refers to active substance, the simple clotrimazole; ** CLZ herba caps, refers to vegetable capsules containing pure clotrimazole).

| Carrier-CLZ |

Drug used for entrapment (mg) |

Loading

Solution

(10 mL, except three carriers, and it is specified) |

Drug Effectively Entrapped

(mg) |

Release buffer/

volume |

Cumulative Drug Release/

release at Tx |

| MCM-41-CLZ |

100.2 |

HCl 0.1 N |

99.9 |

HCl 0.1 N buffer/

200 mL |

98.88%

(in 1 h)

|

M1-

CLZ-r1 |

100 |

HCl 0.1 N |

99.866 |

HCl 0.1 N buffer/

200 mL |

14.39% (in 1 h)

45.07%

(in 5.66 h) 46.54%

(in 23.5 h) |

| M1-CLZ-r2 |

100 |

HCl 0.1 N |

99.96 |

HCl 0.1 N buffer/

200 mL |

57.1%

(in 23.5 h) |

M1-

CLZ-r3 |

100 |

HCl 0.1 N |

99.95 |

HCl 0.1 N buffer/

200 mL |

38.57%

(in 23.5 h) |

M2-

CLZ-r1 |

100 |

HCl 0.1 N |

99.97 |

HCl 0.1 N buffer/

200 mL |

32.62%

(in 23.5 h) |

| M2-CLZ-r2 |

100 |

HCl 0.1 N |

99.97 |

HCl 0.1 N buffer/

200 mL |

34.86%

(in 23.5 h) |

| M2-CLZ-r3 |

100 |

HCl 0.1 N |

99.98 |

HCl 0.1 N buffer/

200 mL |

34.01%

(in 23.5 h) |

| MCM-41-CLZ-r1 |

100 |

H2O:1,2-propanediol=15:85 |

96.7 |

H2O:1,2-propanediol=15:85/

100 mL |

90.91%

(in first 5 minutes) |

| M1-CLZ-r1 |

100 |

H2O:1,2-propanediol=15:85 |

97.85 |

H2O:1,2-propanediol=15:85/

100 mL |

99%

(in first 5 minutes) |

| MCM-41-CLZ-r2 |

100 |

H2O:1,2-propanediol=15:85 |

97.77 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

59.3%-62.17%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| M1-CLZ-r2 |

100 |

H2O:1,2-propanediol=15:85 |

96.92 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

64.41%-71.42%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| M2-CLZ-r2 |

100 |

H2O:1,2-propanediol=15:85 |

98.18 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

63.88%-67.63%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| CLZ-pure-r1 |

100.3 |

- |

- |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

97.57%-100%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| CLZ-pure-r2 |

100.5 |

- |

- |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

94%-100%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| CLZ-pure-r3 |

100.7 |

- |

- |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

93%-97.63%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| CLZ-herba caps-r1 |

100.5 |

- |

- |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

5.44%-100%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| CLZ-herba caps-r2 |

100.8 |

- |

- |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

5.43%-100%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| CLZ-herba caps-r3 |

100.2 |

- |

- |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

5.57%-100%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| M1-CLZ-r1 |

100.2 |

Ethanol |

98.17 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

8.11%-15.16%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| M1-CLZ-r2 |

100.8 |

Ethanol |

97.71 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

7.19%-15.21%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| M1-CLZ-r3 |

100 |

Ethanol |

98.63 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

6.12%-11.05%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| M2-CLZ-r1 |

100.2 |

Ethanol |

99.68 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

6%-12.38%

(in 5.66 h) |

| M2-CLZ-r2 |

100.2 |

Ethanol |

99.68 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

9.6%-15.94%

(in 5.66 h) |

| M2-CLZ-r3 |

100.2 |

Ethanol |

99.68 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

5.49%-11.38%

(in 5.66 h) |

| M1-CLZ-r1 |

100.5 |

KCl-HCl pH=2 |

87.44 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

67.26%-89.33%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| M1-CLZ-r2 |

100.8 |

KCl-HCl pH=2 |

86.96 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

67.26%-89.33%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| M1-CLZ-r3 |

100.8 |

KCl-HCl pH=2 |

86.1 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

51.44%-91.27%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |

| M2-CLZ-r1 |

100.6 |

KCl-HCl pH=2

50 mL |

13.38 |

KCl-HCl pH=2/

900 mL |

59.86%-90.18%

(in 3 h and 20 minutes) |