Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

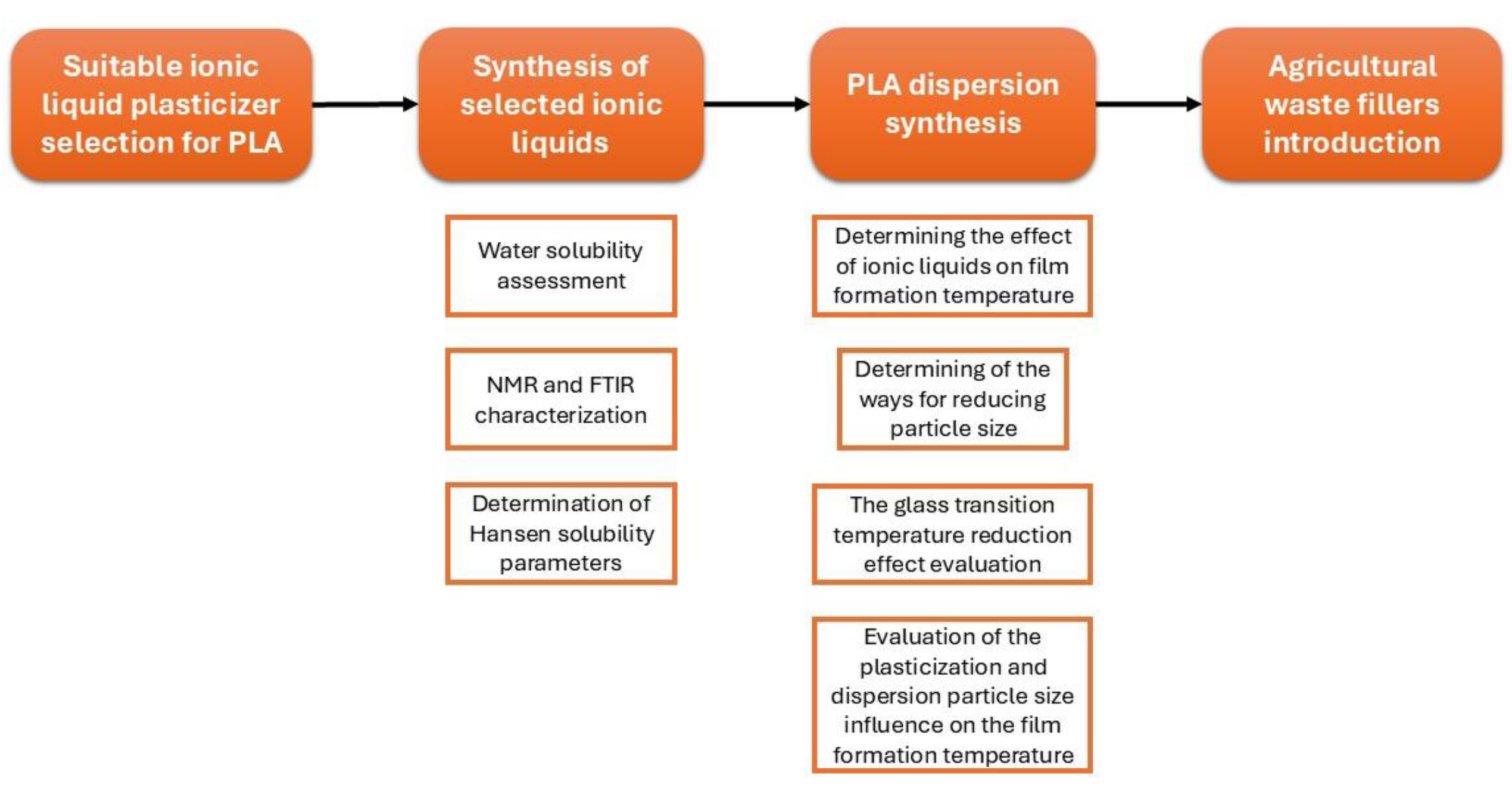

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

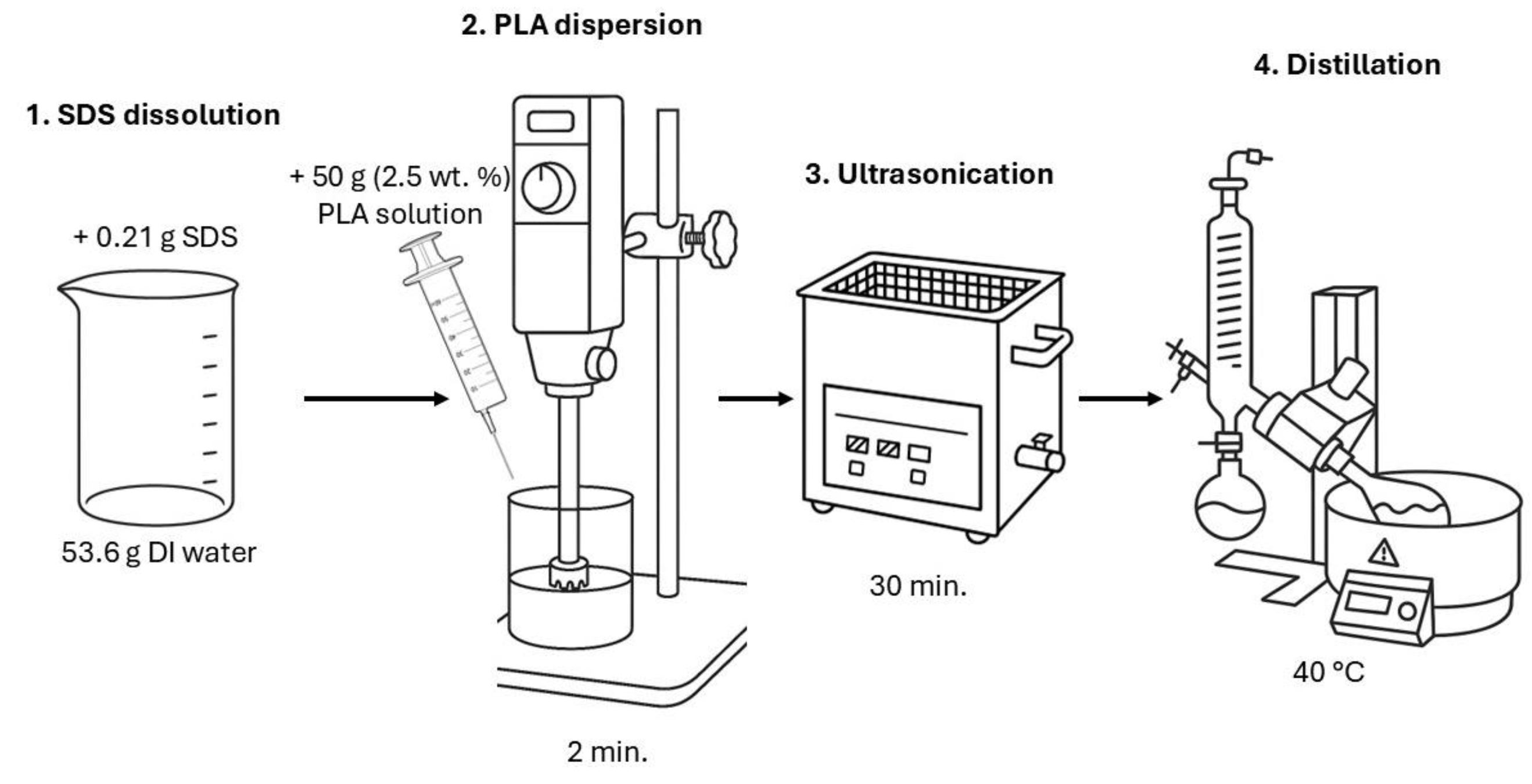

2.2. Obtaining Polylactide Dispersions

2.3. Biofillers Obtaining

2.4. Characterization Methods

3. Results and Discussion

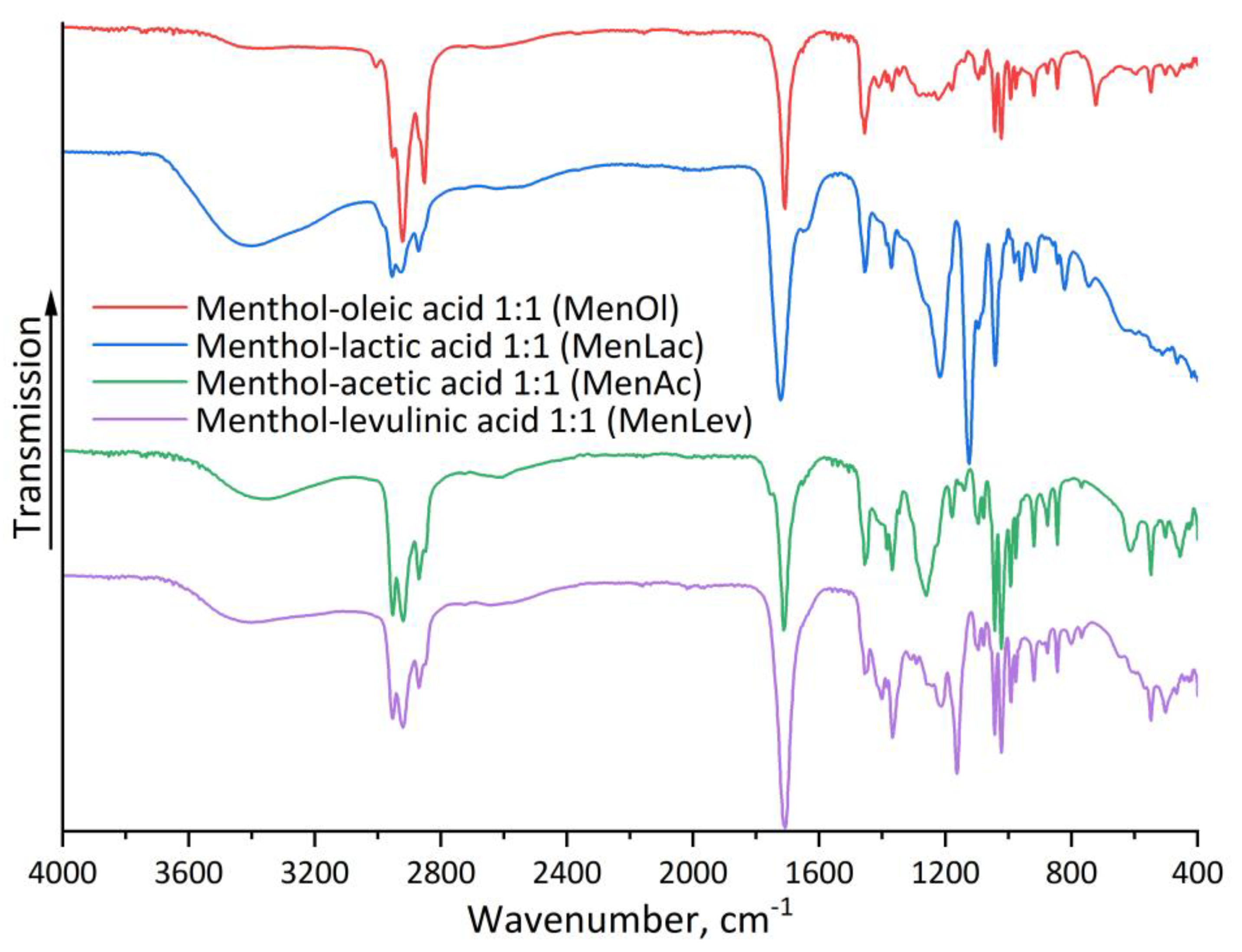

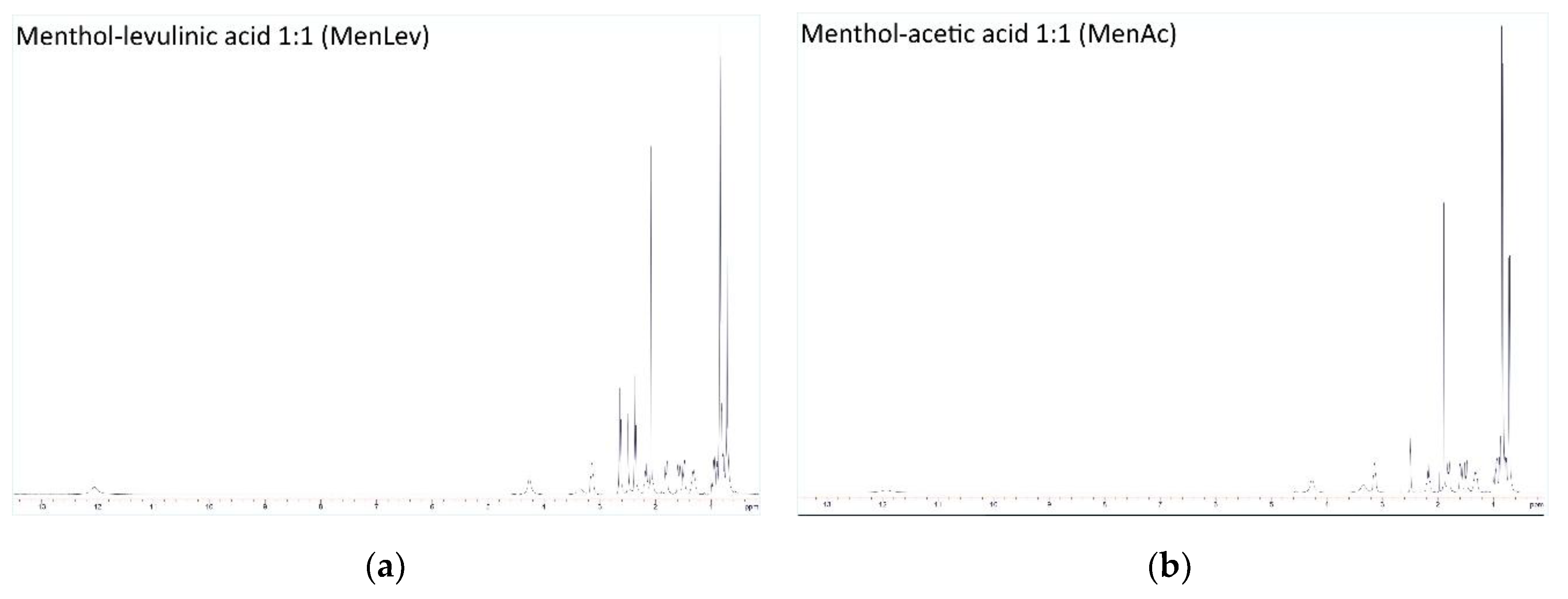

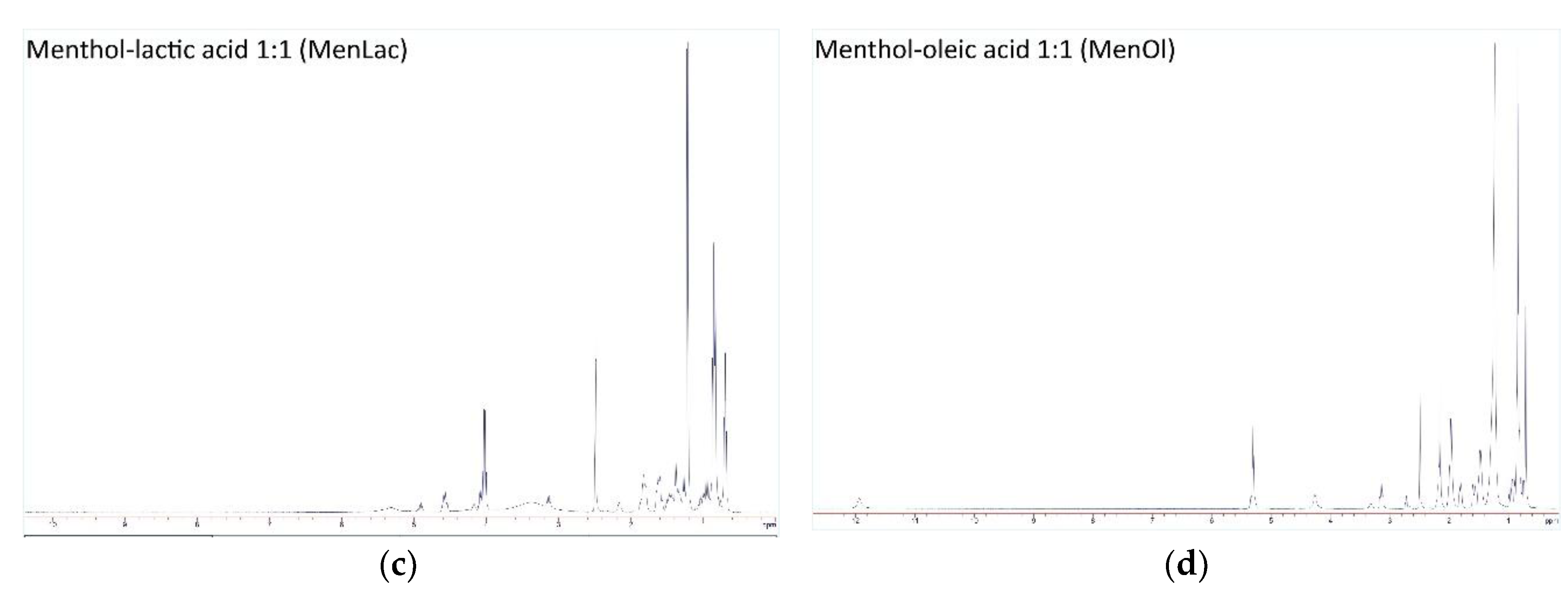

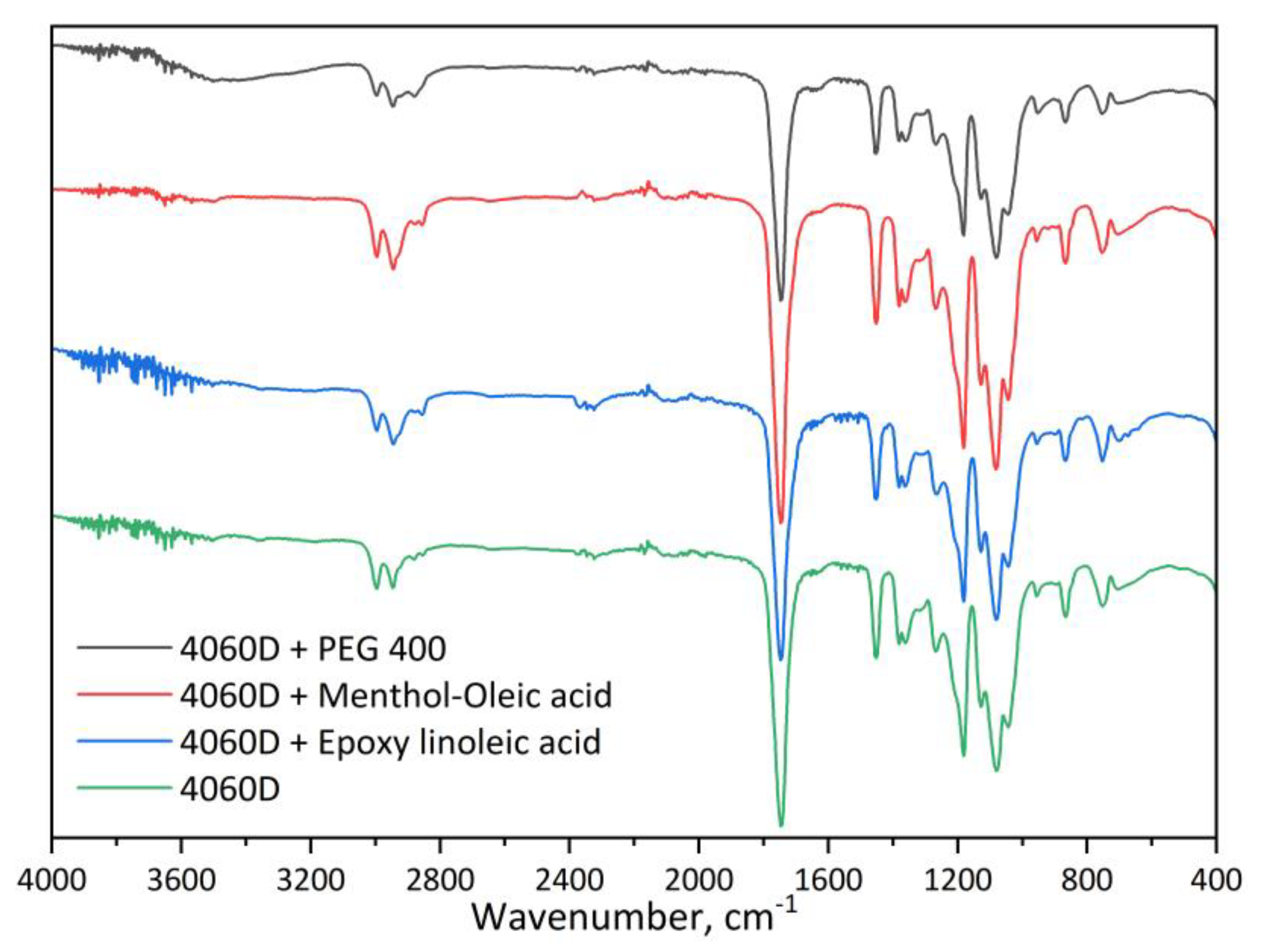

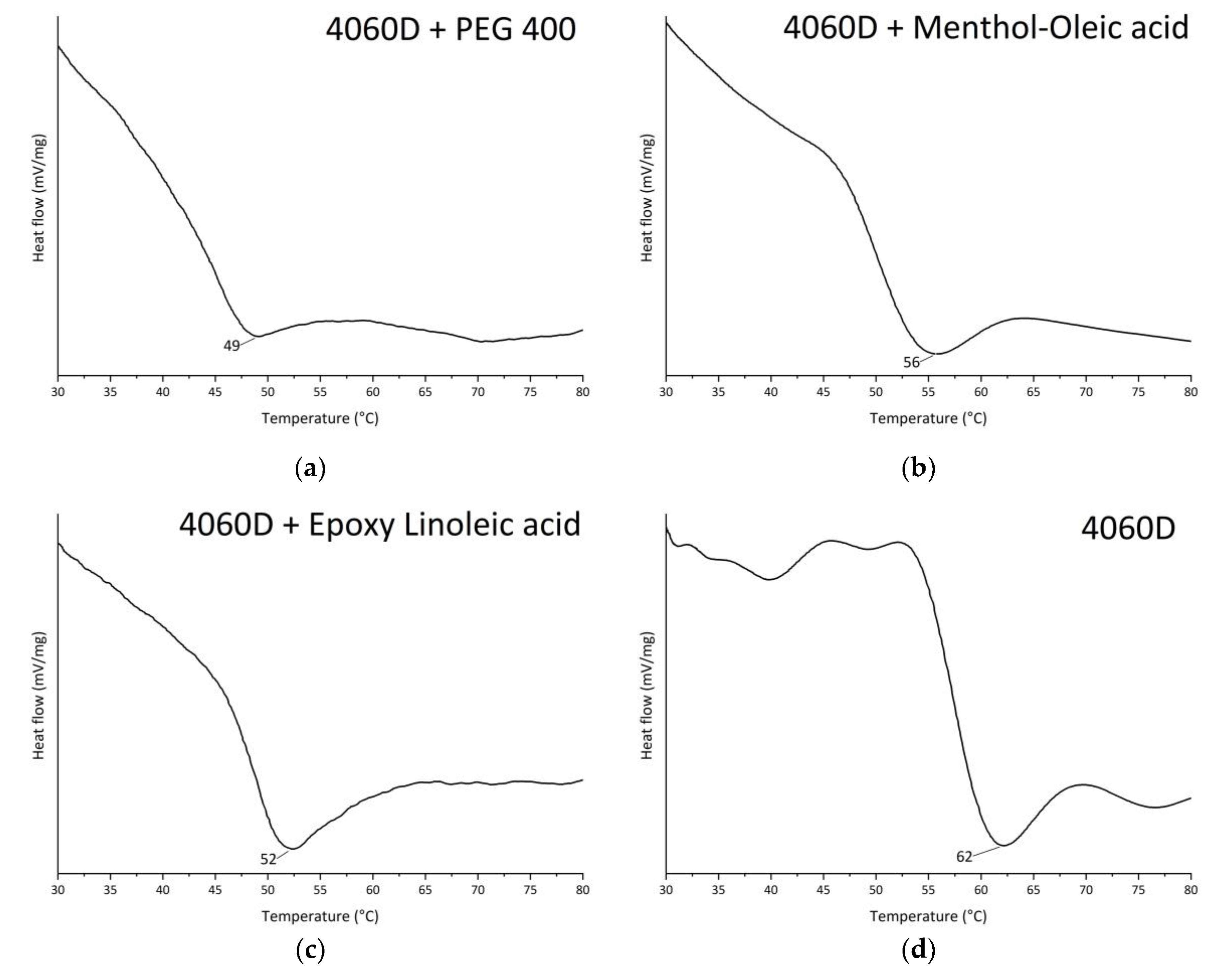

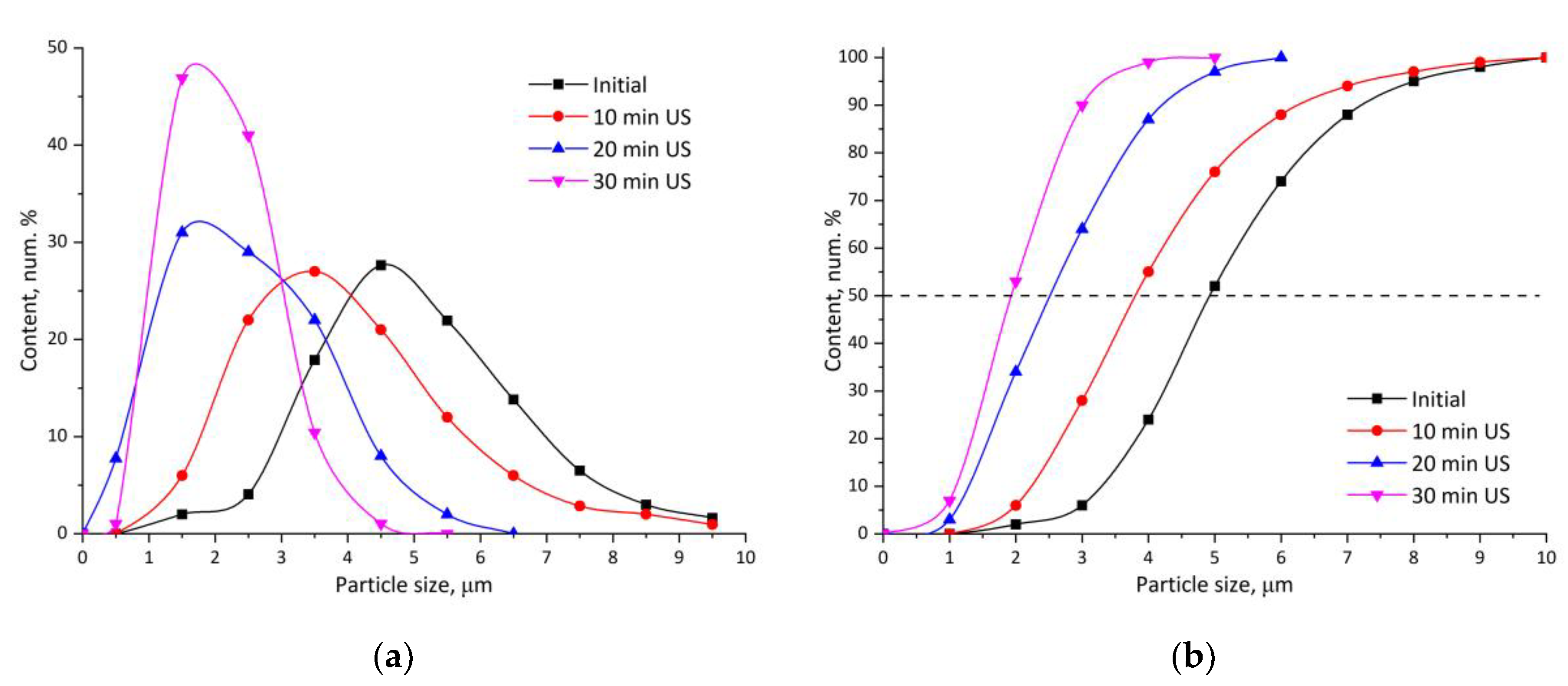

3.1. NMR and FTIR Characterization of HDES

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLA | Polylactide |

| MFFT | Minimum film-formation temperature |

| HDES | Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| RED | Relative Energy Difference |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

References

- Righetti, G.I.C.; Faedi, F.; Famulari, A. Embracing Sustainability: The World of Bio-Based Polymers in a Mini Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 950. [CrossRef]

- Cywar, R.M.; Rorrer, N.A.; Hoyt, C.B.; Beckham, G.T.; Chen, E.Y. -x. Bio-Based Polymers with Performance-Advantaged Properties. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 7, 83–103. [CrossRef]

- Naser, A.Z.; Deiab, I.; Darras, B.M. Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) and Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), Green Alternatives to Petroleum-Based Plastics: A Review. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 17151–17196. [CrossRef]

- Barletta, M.; Aversa, C.; Ayyoob, M.; Gisario, A.; Hamad, K.; Mehrpouya, M.; Vahabi, H. Poly(Butylene Succinate) (PBS): Materials, Processing, and Industrial Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 132, 101579. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Sanders, J. Cunniffe, E. Carrejo, C. Burke, A. M. Reynolds, S. C. Dey, M. N. Islam, O. Wagner, D. Argyropoulos, Biobased Polyethylene Furanoate: Production Processes, Sustainability, and Techno-Economics. Adv. Sustainable Syst. 2024, 8, 2400074. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, G.; Laurel, M.; MacKinnon, D.; Zhao, T.; Houck, H. A.; Becer, C. R. Polymers without petrochemicals: Sustainable routes to conventional monomers. Chem. Rev. 2022, 123, 2609–2734. [CrossRef]

- Goliszek-Chabros, M.; Smyk, N.; Xu, T.; Matwijczuk, A.; Podkościelna, B.; Sevastyanova, O. Lignin Nanoparticle-Enhanced PVA Foils for UVB/UVC Protection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35735. [CrossRef]

- Goliszek, M.; Podkościelna, B.; Smyk, N.; Sevastyanova, O. Towards Lignin Valorization: Lignin as a UV-Protective Bio-Additive for Polymer Coatings. Pure Appl. Chem. 2023, 95, 475–486. [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Zuber, M.; Zia, K. M.; Noreen, A.; Anjum, M. N.; Tabasum, S. Microbial production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (phas) and its copolymers: A review of recent advancements. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 161–174. [CrossRef]

- Khouri, N.G.; Bahú, J.O.; Blanco-Llamero, C.; Severino, P.; Concha, V.O.C.; Souto, E.B. Polylactic Acid (PLA): Properties, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications – A Review of the Literature. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1309, 138243. [CrossRef]

- Belletti, G.; Buoso, S.; Ricci, L.; Guillem-Ortiz, A.; Aragón-Gutiérrez, A.; Bortolini, O.; Bertoldo, M. Preparations of Poly(lactic acid) Dispersions in Water for Coating Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 2767. [CrossRef]

- Pieters, K.; Mekonnen, T. H. Stable aqueous dispersions of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV) polymer for barrier paper coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 187, 108101. [CrossRef]

- Calosi, M.; D’Iorio, A.; Buratti, E.; Cortesi, R.; Franco, S.; Angelini, R.; Bertoldo, M. Preparation of high-solid PLA waterborne dispersions with PEG-PLA-PEG block copolymer as surfactant and their use as hydrophobic coating on paper. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 193, 108541. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.H.; Qi, P.; Rostagno, M.; Feteha, A.; Miller, S.A. The Quest for High Glass Transition Temperature Bioplastics. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 9298–9331. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, C. Recent Advancements in Bio-Based Plasticizers for Polylactic Acid (PLA): A Review. Polym. Test. 2024, 140, 108603. [CrossRef]

- Mastalygina, E.E.; Aleksanyan, K.V. Recent Approaches to the Plasticization of Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) (A Review). Polymers 2023, 16, 87. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jiang, Y.; Lv, S.; Liu, X.; Gu, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of Plasticized Poly (Lactic Acid) and Its Influence on the Properties of Composite Materials. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193520. [CrossRef]

- Harte, I.; Birkinshaw, C.; Jones, E.; Kennedy, J.; DeBarra, E. The Effect of Citrate Ester Plasticizers on the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Poly(DL--lactide). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 127, 1997–2003. [CrossRef]

- Shamshina, J.L.; Berton, P. Ionic Liquids as Designed, Multi-Functional Plasticizers for Biodegradable Polymeric Materials: A Mini-Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1720. [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, L.P.N.; Lopes, J.N.C.; Esperança, J.M.S.S.; Filipe, E. On the Critical Temperature, Normal Boiling Point, and Vapor Pressure of Ionic Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 6040–6043. [CrossRef]

- Rooney, D.; Jacquemin, J.; Gardas, R. Thermophysical Properties of Ionic Liquids. Top. Curr. Chem. 2009, 290, 185–212. [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K.; Kruzel, M.; Smuga-Kogut, M.; Walczak, M. A Review of the State of the Art on Ionic Liquids and Their Physical Properties during Heat Transfer. Energies 2025, 18, 4053. [CrossRef]

- Chaos, A.; Sangroniz, A.; Fernández, J.; del Río, J.; Iriarte, M.; Sarasua, J. R.; Etxeberria, A. Plasticization of poly(lactide) with poly(ethylene glycol): Low weight plasticizer vs triblock copolymers. effect on free volume and barrier properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 137. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A.B.A.; Hasan, Z.; Omran, A.A.B.; Elfaghi, A.M.; Khattak, M.A.; Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M. Effect of Various Plasticizers in Different Concentrations on Physical, Thermal, Mechanical, and Structural Properties of Wheat Starch-Based Films. Polymers 2023, 15, 63. [CrossRef]

- Jarray, A.; Gerbaud, V.; Hemati, M. Polymer-plasticizer compatibility during coating formulation: A multi-scale investigation. Prog. Org. Coat. 2016, 101, 195–206. [CrossRef]

- Arjmandi, A.; Bi, H.; Nielsen, S. U.; Dam-Johansen, K. From wet to protective: Film formation in Waterborne Coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 16, 58006–58028. [CrossRef]

- Yomo, S. Curing Behavior of Waterborne Paint Containing Catalyst Encapsulated in Micelle. Coatings 2021, 11, 375. [CrossRef]

- Myronyuk, O.; Baklan, D.; Bilousova, A.; Smalii, I.; Vorobyova, V.; Halysh, V.; Trus, I. Plasticized Polylactide Film Coating Formation from Redispersible Particles. AppliedChem 2025, 5, 14. [CrossRef]

- De Los Ríos, M.D.; Belmonte, R.M. Extending Microsoft Excel and Hansen Solubility Parameters Relationship to Double Hansen’s Sphere Calculation. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 185.

- De Los Ríos, M.D.; Ramos, E.H. Determination of the Hansen Solubility Parameters and the Hansen Sphere Radius with the Aid of the Solver Add-in of Microsoft Excel. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 676.

- Fernandes, C.C.; Paiva, A.; Haghbakhsh, R.; Duarte, A.R.C. Application of Hansen Solubility Parameters in the Eutectic Mixtures: Difference between Empirical and Semi-Empirical Models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3862. [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, M.H.; Haq, N.; Alam, P.; Abdel-Kader, M.S.; Foudah, A.I.; Shakeel, F. Solubility Data, Hansen Solubility Parameters and Thermodynamic Behavior of Pterostilbene in Some Pure Solvents and Different (PEG-400 + Water) Cosolvent Compositions. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 331, 115700. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Han, M.; Liu, Y.; Ji, S. Effect of Molecular Weight of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) on Plasticization of Poly(ʟ-Lactic Acid). Polymer 2021, 223, 123720. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.A.M.M.; Cruz, S.M.A.; Coelho, J.F.J.; Serra, A.C. The Impact of the Addition of Compatibilizers on Poly (lactic acid) (PLA) Properties after Extrusion Process. Polymers 2020, 12, 2688. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Hakkarainen, M.; Odelius, K. Levulinic Acid as a Versatile Building Block for Plasticizer Design. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mascia, L.; Kouparitsas, Y.; Nocita, D.; Bao, X. Antiplasticization of Polymer Materials: Structural Aspects and Effects on Mechanical and Diffusion-Controlled Properties. Polymers 2020, 12, 769. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E.; Orozco, V.H.; Hoyos, L.M.; Giraldo, L.F. Study of Sonication Parameters on PLA Nanoparticles Preparation by Simple Emulsion-Evaporation Solvent Technique. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 173, 111307. [CrossRef]

- Buoso, S.; Belletti, G.; Ragno, D.; Castelvetro, V.; Bertoldo, M. Rheological Response of Polylactic Acid Dispersions in Water with Xanthan Gum. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 12536–12548. [CrossRef]

- Keresztes, J.; Csóka, L. Characterisation of the Surface Free Energy of the Recycled Cellulose Layer that Comprises the Middle Component of Corrugated Paperboards. Coatings 2023, 13, 259. [CrossRef]

- Baklan, D.; Bilousova, A.; Wesolowski, M. UV Resistance and Wetting of PLA Webs Obtained by Solution Blow Spinning. Polymers 2024, 16, 2428. [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, M.A.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J.W.; Deep, A. Hydrolytic Degradation of Polylactic Acid (PLA) and Its Composites. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 1346–1352. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Wee, J.-W. Effect of Temperature and Relative Humidity on Hydrolytic Degradation of Additively Manufactured PLA: Characterization and Artificial Neural Network Modeling. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 230, 111055. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Link, G.; Jelonnek, J. 3D Microwave Printing Temperature Control of Continuous Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 187, 107939. [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Ibe, Y.; Jono, T.; Naito, A. Structure and Dynamics of Biodegradable Polyurethane-Silk Fibroin Composite Materials in the Dry and Hydrated States Studied Using 13C Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 190, 109645. [CrossRef]

| Title 1 | δd | δp | δh | R0 | Ra | RED | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menthol-Levulinic acid 1:1 (MenLev) | 17.15 | 5.17 | 10.96 | 6.7 | 0.79 | [31] | |

| Menthol-Acetic acid 1:1 (MenAc) | 16.88 | 4.15 | 11.60 | 7.8 | 0.92 | [31] | |

| Menthol-Lactic acid 1:1 (MenLac) | 16.7 | 2.5 | 8.8 | 7.8 | 0.92 | - | |

| Menthol-Oleic acid 1:1 (MenOl) | 16.8 | 5.0 | 9.4 | 5.8 | 0.68 | - | |

| Epoxy oleic acid | 16.6 | 11.1 | 9.8 | 3.6 | 0.42 | [28] | |

| Epoxy linoleic acid | 16.6 | 11.4 | 10.5 | 4.4 | 0.51 | [28] | |

| PEG-400 | 14.6 | 7.5 | 9.4 | 5.4 | 0.64 | [32] | |

| PLA 4060D | 16.5 | 9.9 | 6.4 | 8.5 | [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).