1. Introduction

Adolescence is a developmental period characterized by biological, cognitive and social maturation processes, that is associated with increased demands on adolescents’ emotion regulation, coping and interpersonal functioning [

1]. This period of rapid development represents a sensitive period of the emergence of emotional and behavioral problems, but also an opportunity for the development of psychological resources and socio-emotional competences [

2,

3]. Although the development of young people’s mental health is influenced by risk factors such as perceived stress or exposure to adverse experiences, protective processes that foster resilience, psychological well-being and adaptive functioning are of equally important significance [

4,

5].

Socio-emotional competences (SECs) are increasingly seen as a central factor in positive development [

6]. They comprise emotion regulation, reflective functioning (i.e., the ability to interpret one’s own and others’ behavior in terms of mental states), self-efficacy, mindfulness, empathy, social problem-solving, and responsible decision-making. Together, these competences enable adolescents to regulate stress, reflect on mental states, build supportive relationships, and feel competent and connected. A number of recent empirical studies consistently found an association between stronger SECs and lower emotional and behavioral problems and higher prosocial behavior and life satisfaction in adolescents [

7,

8].

Mindfulness, understood as a non-judgmental awareness in the present moment, has been associated with lower perceived stress and better emotional regulation in children and adolescents [

9]. Reflective functioning has been shown to be associated with lower externalising problems, better emotion regulation and more adaptive peer relations [

10]. Self-efficacy, i.e., the belief in one’s own ability to cope with challenges, is regarded as an important resilience factor of adolescent development that can predict lower internalizing symptoms and higher life satisfaction [

11,

12,

13].

All of the above variables have been related to the level of youths’ emotional and behavioral adjustment, yet most studies have examined them independently. In real life, adolescents do not rely on a single protective factor but a set of psychosocial resources and competences that interact with each other and shape one’s capacity to cope with stress, to regulate emotions and to respond to difficulties. This highlights the need for an integrative approach that examines the role of multiple protective factors and their interaction with risk processes on well-being.

Perceived stress is one of the strongest predictors of emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents [

14], and is associated with increased anxiety and depressive symptoms, conduct problems and peer relationship difficulties that jointly threaten well-being and quality of life [

15,

16]. Youths’ emotional and behavioral difficulties are typically measured with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [

17], while global indices of subjective well-being and functioning are assessed with such instruments as the KIDSCREEN, a widely-used measure of children and adolescents’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [

18].

Despite the large body of work on these processes, surprisingly few studies have integrated psychological resources, perceived stress, behavioral difficulties and HRQoL in a single structural model. Existing mediation studies typically test only one or two predictors at a time. Key questions remain about how these constructs relate to each other and to functioning and well-being within broader contexts and developmental systems.

A further limitation is that developmental and gender differences have rarely been taken into account in this type of research. Empirical findings suggest that girls experience more internalizing symptoms [

19,

20] and report more perceived stress than boys. Age-related differences include differences between early and mid-adolescents in cognitive maturity, emotion regulation and sensitivity to peer evaluation [

21]. Yet few studies have explicitly tested whether the model structure is invariant across demographic groups. Multi-group SEM is the gold standard for testing such questions, but has been largely overlooked in this field.

Thus, there is a need for research that (a) includes multiple protective and risk processes in a single analytic model, (b) considers the mechanisms linking these processes with HRQoL, a central indicator of global well-being, and (c) tests whether these mechanisms are invariant across gender and developmental stages. Addressing these questions is in line with the scope of this Special Issue.

Research Aims

The study explored how children and adolescents cope with major challenges in the process of emotional and behavioral development along the transition to adolescence, especially on the basis of strengths that help them to maintain well-being under increasing demands for academic and social and emotional competence

A first aim was to specify how general self-efficacy, mindfulness and mentalizing ability, three theoretically distinct but complementary psychological resources, are associated with emotional–behavioral functioning and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). All three constructs are considered core socio-emotional competences that could foster resilience by contributing to a) a sense of agency, b) less reactivity to stress and, consequently, more effective emotion regulation, and c) better sense-making of own and others’ mental states. By incorporating the three predictors in a single structural model, we sought to assess how these psychological resources act as a network rather than in isolation to foster a positive psychological functioning during early and mid-adolescence

Although the study was cross-sectional, a theoretically well-founded model based on previous research on stress and adjustment was tested. We hypothesized that the three psychological resources were indirectly related to HRQoL through the association with perceived stress and emotional–behavioral difficulties, both considered as core processes in adolescent mental health. We explored whether these strengths-based resources could serve as a buffer against the impact of the two core processes on HRQoL and, accordingly, foster a resilient profile of psychological functioning.

A second aim was to investigate the developmental applicability of a number of commonly used psychological measures. Most of the self-report instruments have been validated mainly in older adolescents and may be less adequate to assess emerging socio-emotional competences in younger age groups. As our sample included 10-year-olds, we analyzed reliability indices, distributional properties and differences across age groups to test whether these measures performed adequately on the basis of early adolescents’ competencies.

Finally, we wanted to test whether the structural model was the same for the different gender and age groups. It is important to know whether boys and girls, or younger (10-12 years) and older (13-16 years) adolescents, have similar or different pathways, in order to identify which features of adjustment are universal and which ones require more specific support. We applied multi-group structural equation modeling to test if the relationship between psychological resources, stress, emotional–behavioral problems and HRQoL were the same for the different groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited as part of an online survey study conducted between February and June 2023. A total of 395 adolescents took part in the research (222 girls and 173 boys). Their ages ranged from 10 to 16 years (M = 12.77, SD = 1.88), covering the developmental period from late childhood to mid-adolescence. Recruitment was supported by undergraduate psychology students who collaborated on the project as part of their research training.

Participation was entirely voluntary. Parental consent was obtained electronically before adolescents were allowed to access the survey, and adolescents provided assent by indicating that they understood the purpose of the study and agreed to take part. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology, Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary (approval number: BTK/476-1/2023).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. KIDSCREEN-10 Index

The KIDSCREEN-10 Index is a brief, internationally validated measure of children’s and adolescents’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL), recommended for use approximately from age 8 to 18 years [

18,

22]. HRQoL refers to people’s subjective perceptions of their health and well-being in the context of their everyday lives and cultural environment. In line with this definition, the KIDSCREEN-10 provides a global indicator of HRQoL by integrating physical, psychological, and social aspects of functioning into a single, easy-to-interpret score. Throughout this paper we therefore use the term health-related well-being or HRQoL when referring to KIDSCREEN-10 outcomes, rather than the narrower notion of subjective well-being. The 10 items capture broad components of daily functioning, including general life satisfaction, emotional balance, energy levels, and perceived support from family and peers, rated on 5-point Likert-type scales. Although originally developed as a short form of the longer KIDSCREEN questionnaires, the KIDSCREEN-10 has consistently demonstrated strong psychometric properties across European child and adolescent samples. Internal consistency coefficients in the original validation studies typically ranged between α = .78 and α = .82 [

18], supporting its reliability as a global measure of health-related well-being in both younger and older adolescents. The Hungarian version of the KIDSCREEN questionnaires was also included in the large multinational KIDSCREEN project, which involved extensive coordinated data collection across Europe. The Hungarian subsample exceeded 3,000 children and adolescents [

22], providing strong support for the psychometric soundness of the instrument in the local context.

2.2.2. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [

17] is a widely used behavioral screening tool assessing key aspects of children’s and adolescents’ socio-emotional functioning. The measure consists of five subscales—emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer problems, and prosocial behavior. In the present study, we used the Total Difficulties Score, which is obtained by summing the four difficulties subscales (all except prosocial behavior). The Total Difficulties Score is calculated by summing the four difficulties subscales (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer problems), yielding a score between 0 and 40. It functions as a broad indicator of emotional and behavioral problems, capturing both internalizing tendencies (e.g., anxiety, worry) and externalizing features (e.g., impulsivity, conduct difficulties). This use of the Total Difficulties Score is fully consistent with developmental and clinical research, where it is treated as an overall index of child and adolescent mental health difficulties. The score has also been found to be a useful dimensional indicator of psychopathology in clinical and neurodivergent samples [

23]. While designed for use in 11–16 year olds, the SDQ is also routinely used in research with younger children and its usage from age 10 is supported by the literature. In the original validation study, Goodman [

17] found a Cronbach’s alpha of .73 on the Total Difficulties Score, suggesting acceptable internal consistency for use as a global indicator of emotional and behavioral problems. The SDQ has also been widely used and studied in Hungarian samples. The instrument’s reliability and structural validity were found to be acceptable in Hungarian studies and it has been used in community- and at-risk youth samples [

24,

25].

2.2.3. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

Perceived stress was measured using the 14-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [

26], a widely used instrument assessing the extent to which individuals experience their lives as unpredictable, uncontrollable or overloaded. The items ask respondents to reflect on thoughts and feelings that characterise their subjective experience of stress during the past month, including how often they felt overwhelmed, unable to cope with important things in life, or that they had successfully managed everyday hassles. Responses are given on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“very often”), with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress. In the original validation, the PSS achieved Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .74 to .91 across three separate samples [

26]. In the Hungarian validation [

27] internal reliability was found to be excellent for the 14-item version (α = .88) supporting the instrument’s suitability for Hungarian populations.

2.2.3. General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE)

General perceived competence was measured with the 10 item General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) [

28]. The scale reflects individuals’ beliefs about how well they can confront and solve problems, and how likely they are to function well when facing challenging or stressful situations. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = not at all true to 4 = exactly true, which results in a total score ranging from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy. Even though the GSE was originally designed for use with adults, it has proved to be a reliable and valid measure in adolescent samples as well. A large validation study with more than 1,000 high school students in Hungary yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .83 [

29], and international reliability coefficients range from .76 to .90 in different cultural settings [

28,

30]. The GSE is therefore reliable and appropriate for use with this population.

2.2.4. Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM)

Mindfulness was assessed using the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) [

31], a 10-item self-report instrument developed to capture the degree of non-judgmental, accepting awareness of one’s internal experiences. The CAMM evaluates how openly and flexibly children and adolescents relate to their thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations—core components of psychological flexibility. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never true to 4 = always true), and after reverse scoring the positively phrased items, total scores range from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate greater mindfulness skills. Although originally designed for youth aged 10–17, the CAMM has been widely validated across numerous countries and linguistic contexts. Beyond the English original, the measure has been translated and adapted into Portuguese, Catalan, Dutch, Italian, and French. Across these validations, internal consistency estimates are consistently strong, with Cronbach’s alpha values typically ranging between .79 and .85, supporting the scale’s reliability in both early and mid-adolescence [

32,

33,

34,

35].

2.2.5. Reflective Functioning Questionnaire for Youth (RFQY-5)

Reflective functioning (mentalizing ability) was assessed using the 5-item short form of the Reflective Functioning Questionnaire for Youth (RFQY-5). The RFQY-5 is derived from the longer, 46-item RFQ-Y originally developed to measure how adolescents understand their own and others’ behaviour in terms of underlying mental states –such as feelings, intentions, desires, and beliefs [

36]. Unlike the adult RFQ, which contains more abstract and metacognitively demanding items, the youth version uses developmentally appropriate, child-friendly wording specifically tailored to younger respondents. The RFQY-5 items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), for a total score ranging from 5 to 30, with higher scores indicating a greater perceived capacity for mentalizing. Although the original RFQ-Y was normed on an adolescent sample aged 11–18 years [

37], the [

33]brevity and simple language of the 5-item short form make it suitable for use with younger adolescents, as even 10–11-year-olds can understand the items and provide meaningful responses.

Although brief, the RFQY-5 provides acceptable reliability for a multidimensional construct such as mentalizing: Jewell and colleagues [

36] obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of .75 in their sample of adolescents and found that it can be used as a brief measure of reflective functioning. Although the 5-item form has not yet been specifically validated in Hungary, the full RFQ-Y has recently been adapted and validated in a large Hungarian adolescent sample [

38], providing evidence for the broader cultural applicability of reflective functioning measures.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

First, we characterized the study variables, by means of descriptive statistics (i.e., means, SDs, as well as skewness and kurtosis indices), and by internal consistency estimates (i.e., Cronbach’s α). Since the main objective of the analysis was to test a theoretically informed structural model, we examined the normality of the observed variables, through the corresponding skewness and kurtosis indices. Per commonly used psychometric recommendations, absolute values below 1.0 were considered to represent an indication of acceptable univariate normality for correlation-based and SEM analyses [

39,

40].

To test group differences, we used 2-way ANOVAs, with gender (girls, boys) and age group (younger adolescents: 10–12 years; older adolescents: 13–16 years) as between subjects factors. Due to the slight deviations from normality observed in some variables, we used Spearman’s rank-order correlations to test the associations between all the study variables.

We performed SEM analyses in order to test the hypothesised causal pathways between psychological resources (GSE, CAMM, RFQY-5), perceived stress (PSS), emotional–behavioral difficulties (SDQ), and health-related quality of life (KIDSCREEN-10). Following established methodological guidelines [

40,

41,

42,

43], we tested model fit, through several complementary fit indices (χ2/df, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI; [

44]), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; [

45]).

Generally, χ2/df < 3, CFI and TLI ≥ .95, and RMSEA ≤ .06 are considered to represent good model fit, whereas values between .06–.08 are interpreted as acceptable [

41,

46].

To assess the developmental stability of the hypothesised pathways, we conducted multi-group SEM analyses to test structural invariance across gender and age in our sample. This is a crucial step in the assessment of the developmental stability of the psychological mechanisms theorized to underlie stress and well-being [

47]. Specifically, the degree to which the key structural paths a) differ between girls and boys, and b) differ between younger and older adolescents, are of interest. We followed broadly recommended guidelines [

48,

49] to test structural invariance, by examining changes in model fit for progressively more constrained models.

All the descriptive analyses were conducted with SPSS 22 [

46]. We estimated all SEM models with AMOS 23 [

51] and JASP (version 0.18).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability of the Measures

The descriptive statistics and reliability estimates for all study measures are summarised in

Table 1. Overall, the internal consistency coefficients were acceptable across instruments, both in light of international validation studies and, where available, Hungarian adaptation work. All scales met or exceeded the commonly used criterion of α ≥ .70, indicating that the measures performed adequately in our 10–16-year-old sample.

Regarding distributional properties, skewness and kurtosis values generally fell within the recommended ±1 range, suggesting no substantial deviations from normality. The only exception was the kurtosis of the General Self-Efficacy Scale, which slightly exceeded this threshold; however, the departure was small and unlikely to meaningfully affect subsequent analyses.

We also examined group differences by sex and age using two-way analyses of variance. Patterns were largely consistent with prior developmental research. Health-related quality of life (KIDSCREEN-10) was higher among boys than girls and also higher among younger adolescents compared with older ones. A significant interaction further indicated that the age-related decrease in HRQoL was more pronounced in girls than in boys. Adolescent development and stress: a cross-sectional, age-related examination of the contribution of socio-cognitive resources. Older adolescents reported more problems in emotional and behavioral functioning (SDQ) consistent with the well-known increase in internalizing and externalising problems during mid-adolescence. Perceived stress (PSS) was also higher in older compared to younger adolescents. Both mindfulness (CAMM) and mentalizing ability (RFQY-5) increased with age consistent with the progressive development of self-regulatory and socio-cognitive resources from early to mid-adolescence. Girls reported higher scores on both of these constructs consistent with evidence that adolescent females report higher levels of emotional awareness and increased sensitivity to interpersonal cues. These convergent age and sex patterns support the interpretability of our measures and provide a coherent backdrop for the subsequent structural equation modelling analyses.

Consistent with theoretical expectations, health-related quality of life (KIDSCREEN-10) was strongly negatively associated with both the emotional and behavioral difficulties (SDQ) and the perceived stress (PSS), which imply that adolescents who reported more symptoms or higher subjective stress scores reported considerably lower overall well-being (

Table 2). Furthermore, a small positive association emerged between HRQoL and the mentalizing ability (RFQY-5) indicating that adolescents who were more capable to interpret mental states reported slightly higher well-being. The SDQ Total Difficulties score was strongly positively correlated with PSS and (in the opposite direction) strongly negatively correlated with mindfulness, which represents the well known association between psychosocial difficulties, stronger negative stress experience and a reduced ability for non-judgmental awareness. Also, a parallel pattern was found for the PSS - mindfulness link, i.e., high negative stress experience was accompanied by reduced mindful awareness. In contrast to this, we found only small correlations between psychological resources - self-efficacy, mindfulness and mentalizing, which implies that although all these constructs reflect adaptive functioning, they represent different aspects of adolescents’ coping and regulatory capacities rather than a single psychological resource factor.

Overall, the correlational pattern indicates that stress and psychosocial difficulties form a tightly interconnected cluster, whereas self-efficacy, mindfulness, and reflective functioning contribute more independently to adolescents’ adjustment.

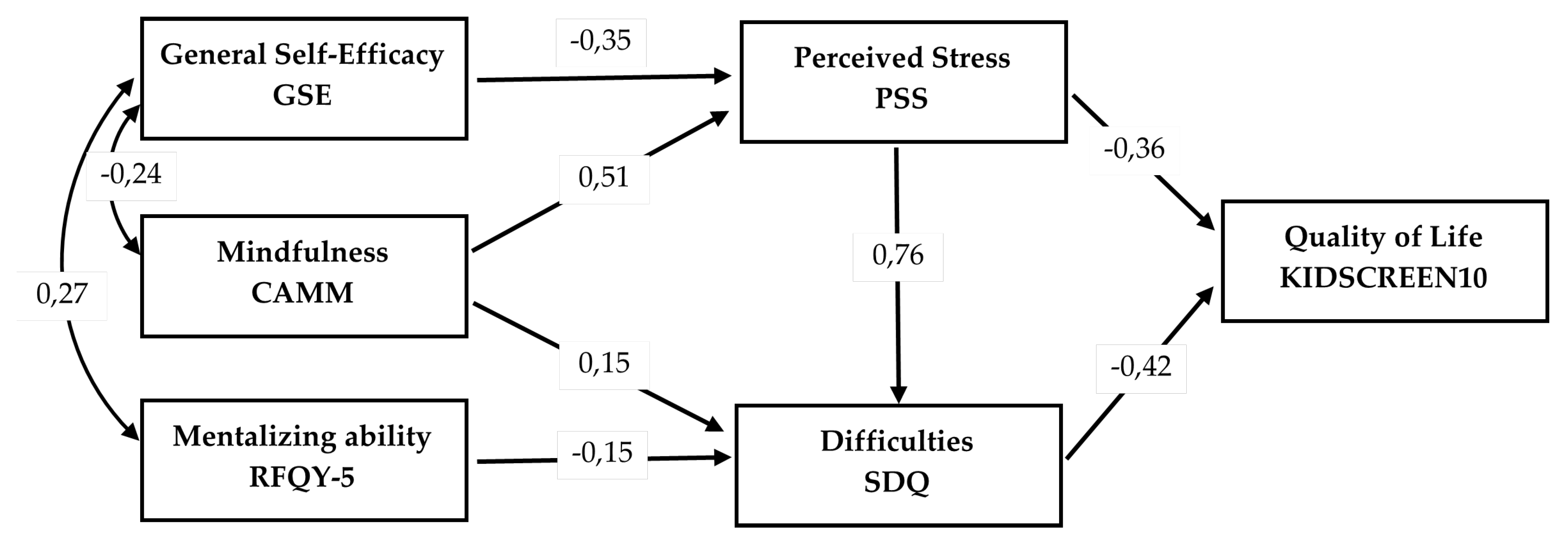

3.1. Structural Path Model of Stress, Psychological Resources, and Well-Being

To examine how psychological resources, perceived stress, and emotional–behavioral difficulties jointly contribute to adolescents’ health-related quality of life, we estimated a structural path model including mindfulness (CAMM), general self-efficacy (GSE), and mentalizing ability (RFQY-5) as predictors of perceived stress (PSS) and emotional/behavioral problems (SDQ), which in turn predicted health-related quality of life (KIDSCREEN-10). We began with a theoretically informed full model and gradually removed all non-significant paths. This parsimony-oriented refinement was guided by modification indices, zero-order correlations, and theoretical considerations regarding the plausible direction of influence among constructs. The resulting final model therefore includes only statistically and conceptually meaningful pathways, offering a concise representation of the processes linking psychological resources to adolescents’ well-being (model fit: χ2(4) = 6.85, p = 0.144, CFI = 0.997, TLI = 0.990, RMSEA = 0.042, SRMR = 0.018).

A residual covariance between perceived stress and emotional/behavioral difficulties was retained (standardized value = −0.37), indicating that the two constructs shared substantial variance even after accounting for the three psychological resource variables. Allowing their residuals to correlate avoids imposing an artificial causal direction in a cross-sectional design, and yields a more realistic depiction of their empirically intertwined nature.

Within this final structure, both self-efficacy and mindfulness emerged as significant negative predictors of perceived stress, suggesting that these psychological resources operate mainly by reducing adolescents’ sense of unpredictability and overload rather than by directly shaping their emotional and behavioral adjustment. Mentalizing ability showed a small direct association with health-related quality of life but did not predict stress or emotional–behavioral problems, which is consistent with the minimal zero-order correlations observed between RFQY-5 and the other constructs.

Perceived stress in turn showed a strong positive association with emotional and behavioral difficulties, indicating that adolescents who experience their everyday lives as more overwhelming are also more likely to report internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Both perceived stress and emotional–behavioral difficulties independently predicted lower health-related quality of life, jointly accounting for a substantial proportion of variance in adolescents’ subjective well-being. Notably, none of the psychological resource variables had a direct effect on health-related quality of life once stress and emotional/behavioral problems were included in the model, suggesting that their influence is primarily indirect and mediated through adolescents’ stress appraisals and symptomatology.

Figure 1.

Final Structural Equation Model of Psychological Resources, Stress, Difficulties, and Health-Related Quality of Life.

Figure 1.

Final Structural Equation Model of Psychological Resources, Stress, Difficulties, and Health-Related Quality of Life.

To examine whether the structural model functioned similarly across key demographic groups, we conducted a series of multi-group SEM invariance analyses for gender and age. For gender, model fit remained excellent across all levels of constraint, with changes well within recommended thresholds (ΔCFI ≤ .006; ΔRMSEA ≤ .004), indicating that the structural paths linking psychological resources, perceived stress, emotional–behavioral difficulties, and health-related quality of life did not differ meaningfully between boys and girls. This suggests that the underlying psychological processes captured by the model operate in a comparable way across genders. For age groups, the configural model - testing the baseline pattern of associations in younger (10–12 years) and older (13–16 years) adolescents - showed somewhat weaker fit (CFI = .967, RMSEA = .085), suggesting modest initial age-related variability. However, imposing equality constraints on factor loadings did not impair model fit (ΔCFI = .000; ΔRMSEA = .000), indicating that the measurement relations were equivalent across age groups. Interestingly, the scalar model, which also constrained intercepts, showed improved fit (CFI = .986, RMSEA = .073), implying that freely estimated intercepts introduced unnecessary noise rather than representing substantive developmental differences. Overall, this pattern supports the conclusion that the structural model is broadly invariant across age groups and that comparisons between younger and older adolescents are justified.

4. Discussion

This research tried to put three often studied psychological strengths—self-efficacy, mindfulness, and reflective functioning—into one main model. The model links emotional adjustment, perceived stress, and health and life quality in teenagers. Global research says these strengths act on well-being not directly, but because of their relation with thinking stress and emotional and behavioral health. Early research follows developmental and clinical ideas, and says strengths and weaknesses are both important [

15,

52]. Our model points out that these strengths work in an indirect way, and change how young people experience, understand, and act with stress in daily life.

Many studies have shown that self-efficacy is related to resilience and better coping abilities, less stress, and better emotional health [

12,

53]. Our findings match what has been found before: teenagers who see themselves as able to deal with difficulties have less stress, and this leads to less emotional and behavioral problems, and also higher health and life quality. We also found that mindfulness works in the same way: teenagers who have better mindfulness skills have less stress. These results are similar to other studies [

9,

54,

55] that say teenagers who can stay in the moment see less day-to-day stress as big or uncontrollable. Reflective functioning in teenagers, measured by the youth RFQ, also leads to health and life quality in the same way, because it is related to low stress and low behavioral problems. These findings are like studies with different groups which say that teenagers who can think better and understand themselves and others are better at controlling emotion, less likely to cause trouble, and have better peer relationships [

56,

57].

In our final model, none of the strengths were directly related to health and life quality. This is not a big surprise. Well-being in teenagers is not just about their inner strengths, but also about how stress and trouble affect their daily functioning [

58]. So, our results support ideas that look at strengths and weakness as steps in a process. We can use the model to see how strengths help teenagers, and our findings say that their main job is to act as just part of the problem by making teenagers less open to stress and behavioral problems.

In the model, perceived stress is the center of the system, and directly predicts emotional and behavioral difficulties and health and life quality. This finding matches the literature about mental health in teenagers. Many studies say perceived stress is one of the best signs of internal and external trouble in young people [

14,

26]. High stress has also been linked to hard emotions, trouble with people, and poor school results, all of which can make young people less healthy and happy [

15].

The very strong path from perceived stress to emotional and behavioral difficulties (β = 0.76) emphasizes the central role of stress appraisal in adolescent adjustment. These findings align with prior research showing that stress is among the strongest predictors of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in youth [

15,

59,

60]. Perceiving life as stressful increases emotional and behavioral problems, which in turn undermine well-being. Consistent with this view, the residual covariance between stress and difficulties (−0.37) indicates that these processes are empirically inseparable and likely reciprocal: difficulties may also create stressful contexts, reinforcing vulnerability. This pattern highlights the limitations of cross-sectional designs and the need for approaches that capture dynamic interactions over time. In addition, the strength of the association raises the possibility of conceptual overlap between stress and symptom measures, which future research should address through careful operationalization and tests of measurement invariance. Taken together, our results highlight a process-oriented view: stress and problems do not serve as individual risk factors but as components of a system that influences health and quality of life. This view is also supported by longitudinal data indicating that emotional distress and associated processes usually represent reciprocal loops rather than a unidirectional pathway [

61,

62,

63]. Such results emphasize the importance of multi-wave or cross-lagged designs to disentangle how these processes co-evolve and sustain each other in order to move beyond static snapshots toward a dynamic perspective on adolescent adjustment.

Emotional and behavioral troubles were a sign of low scores for health and life quality. This supports findings about how young people feel about well-being: it is related to what they want and feel, what they do, and how they get along with people. These findings have been used in different ways. A lot of studies say that how a teenager does on the SDQ is related to how sick and hurt they feel, how they are at school and with people, and how they feel about life [

64,

65,

66]. Our findings say that health and life quality is closely related to emotional and behavioral strengths and weaknesses. This also puts strength on the need to find and stop internal and external problems early, especially in early teenage years. This is so that the signs do not fully develop.

Even though there were differences in the means of the groups—for example, girls said they were more mindful and could think better, and older teenagers had more stress and emotional and behavioral problems—the main points of the model were the same between age and gender. The similarities with the age groups, in particular, are important. The same score between old and young teenagers points out that the strengths measured in self-efficacy, mindfulness, and reflective functioning may be developmentally strong enough not to just see with old teenagers. This is important because this study looks at early teenage years, when the abilities measured in our model are still new. Further, it should be remembered that the reliability and use of the different scales measuring strengths was mostly good from ages 10–16. This means that research with younger teenagers can use old measurement tools to understand how young people think about strengths in upper-primary school.

There are a few limitations in this study. To start, the research has no time and cannot use causes. Even though the main model comes from earlier research and ideas, the model could change if it used different causes. In the end, long or cross-lagged models are needed to see how stress, strengths, and emotional and behavioral problems grow and shrink over time, and how this predicts health and life quality. Second, teenagers reported all of the points, and this may add similar ideas. In the end, the use of behavioral and other reports could be better. Third, even though it had good reliability, the study used a big-idea of reflective functioning, measured by a short 5-question scale. This may not show the full way of understanding oneself and others from the reflective functioning idea. Last, the sample comes from one country, and because it was a study using the same country, other countries should test these findings.

From here, research should look at how school, family stress, and friends work with strengths and health and life quality. Research could also look at how much teaching mindfulness, self-efficacy, or reflective functioning works with lowering stress and behavioral problems, and so health and life quality. This research would affect prevention programs related to world programs to help young people’s social and emotional health, and stop youth mental health problems from growing.

5. Conclusions

This research adds to a lot of research that tries to see how teenagers’ strengths work with stress to raise or lower emotions in different ways, and so health and life quality. We have provided ideas about how five of these processes may work in one main model. The findings say that strengths found in self-efficacy, mindfulness, and reflective functioning are part of a working system. This system works on health and life quality not directly, but because of the relation these strengths have with how teenagers work with stress and behavioral problems. This path was the same for boys and girls and for different-age teenagers. In the end, all of the different scales worked well, even for the youngest teenagers. The findings combine with past research on strengths and weaknesses and say that it is important for prevention and research to see how to work with both strengths and weaknesses in young people. Trying to raise these social and emotional strengths could be a good way to stop problems and help teenagers become healthy in the near future. Therefore, it could work well with what the present study looks at.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-R. and A.-K.; methodology, S.-R.; validation, S.-R.; formal analysis, S.-R.; investigation, S.-R. and A.-K.; resources, S.-R. and A.-K.; data curation, S.-R. and A.-K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-R.; writing—review and editing, S.-R. and A.-K.; visualization, S.-R.; supervision/ project administration, A.-K.; funding acquisition, A.-K.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary (approval No: BTK/476-1/2023, date of approval: 09. February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in

the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the

corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HRQoL |

Health-related quality of life |

| SDQ |

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

| PSS |

Perceived Stress Scale |

| GSE |

General Self-Efficacy Scale |

| CAMM |

Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure |

| RFQY-5 |

Reflective Functioning Questionnaire for Youth |

References

- Steinberg, L.D. Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014;

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [CrossRef]

- Woodard, K.; Pollak, S.D. Is There Evidence for Sensitive Periods in Emotional Development? Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2020, 36, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary Magic: Resilience Processes in Development. American psychologist 2001, 56, 227.

- Jones, S.M.; Barnes, S.P.; Bailey, R.; Doolittle, E. Promoting Social and Emotional Competencies in Elementary School. The Future of Children 2015, 25, 49–72. [CrossRef]

- Domitrovich, C.E.; Durlak, J.A.; Staley, K.C.; Weissberg, R.P. Social-Emotional Competence: An Essential Factor for Promoting Positive Development in Children and Adolescents. Child Development 2017, 88, 408–416. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.D.; Oberle, E.; Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P. Promoting Positive Youth Development through School-Based Social and Emotional Learning Interventions: A Meta-Analysis of Follow-up Effects. Child Development 2017, 88, 1156–1171. [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Taylor, R.D.; Schellinger, K.B. The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta--Analysis of School--Based Universal Interventions. Child Development 2011, 82, 405–432. [CrossRef]

- Zoogman, S.; Goldberg, S.B.; Hoyt, W.T.; Miller, L. Mindfulness Interventions with Youth: A Meta-Analysis. Mindful-ness 2015, 6, 290–302. [CrossRef]

- Sharp, C.; Fonagy, P. The Parent’s Capacity to Treat the Child as a Psychological Agent: Constructing the Meaning of Re-Flective Functioning. Social Development 2008, 17, 217–235. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control 1997.

- Muris, P. A Brief Questionnaire for Measuring Self-Efficacy in Youths. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assess-ment 2001, 23, 145–149. [CrossRef]

- Kövesdi, A.; Rózsa, S.; Krikovszky, D.; Dezsőfi, A.; Kovács, L.; Szabó, A. Study of Transplanted Adolescents with a Focus on Resilience. Psychologia Hungarica Caroliensis 2022, 10, 75–94. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D.G.; Davenport, S.C.; Mazanov, J. Profiles of Adolescent Stress: The Development of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ. Journal of Adolescence 2007, 30, 393–416. [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, Emotion Regulation, and Psychopathology in Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analysis and Narrative Review. Psy-chological Bulletin 2017, 143, 939–991. [CrossRef]

- Kövesdi, A.; Hadházi, É.; Törő, K. Egyéni Pszichés Változók Vizsgálata a COVID-19-Járvány Idején. In Horn, D; Bartal, A M (szerk.) Fehér könyv a Covid-19-járvány társadalmi-gazdasági hatásairól; ELKH Közgazdaság- és Regionális Tudományi Kutatóközpont, Közgazdaságtudományi Intézet: Budapest, Magyarország, 2022; pp. 52–67.

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586.

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Herdman, M.; Devine, J.; Otto, C.; Bullinger, M.; Rose, M.; Klasen, F. The European KIDSCREEN Approach to Measure Quality of Life and Well-Being in Children: Development, Current Application, and Future Advances. Quality of life research 2014, 23, 791–803.

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Girgus, J.S. The Emergence of Gender Differences in Depression during Adolescence. Psychological Bulletin 1994, 115, 424–443. [CrossRef]

- Hankin, B.L.; Mermelstein, R.; Roesch, L. Sex Differences in Adolescent Depression: Stress Exposure and Reactivity Mod-Els. Child Development 2007, 78, 279–295. [CrossRef]

- Somerville, L.H. The Teenage Brain: Sensitivity to Social Evaluation. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2013, 22, 121–127. [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Europe, K.I.D.S.C.R.E.E.N.G. The Kidscreen Questionnaires: Quality of Life Questionnaires for Chil-Dren and Adolescents; Handbook; Pabst Science Publ, 2006;

- Grasso, M.; Lazzaro, G.; Demaria, F.; Menghini, D.; Vicari, S. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a Valuable Screening Tool for Identifying Core Symptoms and Behavioural and Emotional Problems in Children with Neuropsychiatric Disor-Ders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7731.

- Birkás, É.; Lakatos, K.; Tóth, I.; Gervai, J. Screening Childhood Behavior Problems Using the Hungarian Version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Psychiatria Hungarica 2008, 23, 358–365.

- Turi E.; Tóth I.; Gervai J. A Képességek és Nehézségek Kérdőív (SDQ-Magy) vizsgálata nem-klinikai mintán, fiatal ser-dülők körében. Psychiatria Hungarica 2011, 26, 415–426.

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress.Journal Of. Health and Social Behaviour 1983, 24, 385 396.

- Stauder A.; Konkolÿ Thege B. Az észlelt stressz kérdőív (PSS) magyar verziójának jellemzői. Mentálhigiéné és pszicho-szomatika 2006, 7, 203–216.

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. Causal and control beliefs 1995, 35, 82–003.

- Jámbori S.; Horváth M.T.; Harsányi S.G. A mentális egészség mutatói serdülőkorban: a Megküzdési Képesség Skála magyar nyelvű alkalmazása. Alkalmazott Pszichológia 2016, 16, 27–46.

- Luszczynska, A.; Scholz, U.; Schwarzer, R. The General Self-Efficacy Scale: Multicultural Validation Studies. The Journal of Psychology 2005, 139, 439–457.

- Greco, L.A.; Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T. Assessing Mindfulness in Children and Adolescents: Development and Validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM. Psychological Assessment 2011, 23, 606–614.

- Cunha, M.; Galhardo, A.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measures (CAMM): Estudos das carac-terίsticas psicométricas da versão Portuguesa. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crίtica 2013, 26, 459–468.

- Bruin, E.I.; Zijlstra, B.J.H.; Bögels, S.M. The Meaning of Mindfulness in Children and Adolescents: Further Validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) in Two Independent Samples from the Netherlands. Mindfulness 2014, 5, 422–430.

- Bartoccini, A.; Sergi, M.R.; Macchia, A.; Romanelli, R.; Tommasi, M.; Rotondo, S. Studio delle proprietà psico-metriche della versione italiana della Child and Adolescent Mind-fulness Measure (CAMM. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale 2017, 23, 11–26.

- Dion, J.; Paquette, L.; Daigneault, I.; Godbout, N. Validation of the French Version of the Child and Adolescent Mindful-Ness Measure (CAMM) among Samples of French and Indigenous Youth. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 645–653.

- Jewell, T.; McLaren, V.; Sharp, C. Psychometric Properties of the Reflective Function Questionnaire for Youth Five-Item Version in Adolescents with Restrictive Eating Disorders. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2024, 46, 760–767.

- Sharp, C.; Steinberg, L.; McLaren, V.; Weir, S.; Ha, C.; Fonagy, P. Refinement of the Reflective Function Questionnaire for Youth (RFQY) Scale B Using Item Response Theory. Assessment 2022, 29, 1204–1215.

- Szabó, B.; Sharp, C.; Futó, J.; Boda, M.; Losonczy, L.; Miklósi, M. The Reflective Function Questionnaire for Youth: Hun-Garian Adaptation and Evaluation of Associations with Quality of Life and Psychopathology. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1497–1511.

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Assessing Normal Distribution. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics 2013, 38, 52–54.

- West, S.G.; Taylor, A.B.; Wu, W. Model Fit and Model Selection in Structural Equation Modeling. Handbook of structural equation modeling 2012, 1, 209–231.

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis. Structural Equation Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55.

- Tanaka, J.S. Multifaceted Conceptions of Fit in Structural Equation Models. Testing structural equation models 1993, 10–39.

- West, S.G.; Wu, W.; McNeish, D.; Savord, A. Model Fit in Structural Equation Modeling. Handbook of structural equa-tion modeling 2023, 2, 184–205.

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A Reliability Coefficient for Maximum Likelihood Factor Analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10.

- Steiger, J.H. Structural Model Evaluation and Modification. Multivariate Behavioral Research 1990, 25, 173–180.

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Signifi-Cance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods of psychological research online 2003, 8, 23–74.

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2002, 9, 233–255. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling 2007, 14, 464–504.

- Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. Measurement Invariance Conventions and Reporting: The State of the Art and Future Directions for Psychological Research. Developmental review 2016, 41, 71–90.

- Corp I.B.M. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, 2013;

- Arbuckle, J.L. AMOS (Version 23.0; Computer software]. IBM SPSS, 2014;

- Shoshani, A.; Steinmetz, S. Positive Psychology at School: A School-Based Intervention to Promote Adolescents’ Mental Health and Well-Being. J Happiness Stud 2014, 15, 1289–1311. [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Warner, L.M. Perceived Self-Efficacy and Its Relationship to Resilience. In Resilience in Children, Adolescents, and Adults; Prince-Embury, S., Saklofske, D.H., Eds.; The Springer Series on Human Exceptionality; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; pp. 139–150 ISBN 978-1-4614-4938-6.

- Dunning, D.L.; Griffiths, K.; Kuyken, W.; Crane, C.; Foulkes, L.; Parker, J.; Dalgleish, T. Research Review: The Effects of Mindfulness--based Interventions on Cognition and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents – a Meta--analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Child Psychology Psychiatry 2019, 60, 244–258. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Fang, S. Adolescents’ Mindfulness and Psychological Distress: The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1358. [CrossRef]

- Sharp, C.; Pane, H.; Ha, C.; Venta, A.; Patel, A.B.; Sturek, J.; Fonagy, P. Theory of Mind and Emotion Regulation Difficulties in Adolescents With Borderline Traits. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2011, 50, 563-573.e1. [CrossRef]

- Chelouche-Dwek, G.; Fonagy, P. Mentalization-Based Interventions in Schools for Enhancing Socio-Emotional Competencies and Positive Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2025, 34, 1295–1315. [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Mental Health in Adolescence: Is America’s Youth Flourishing? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 2006, 76, 395–402. [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.E.; Compas, B.E.; Thurm, A.E.; McMahon, S.D.; Gipson, P.Y.; Campbell, A.J.; Krochock, K.; Westerholm, R.I. Stressors and Child and Adolescent Psychopathology: Evidence of Moderating and Mediating Effects. Clinical Psychology Review 2006, 26, 257–283. [CrossRef]

- March-Llanes, J.; Marqués-Feixa, L.; Mezquita, L.; Fañanás, L.; Moya-Higueras, J. Stressful Life Events during Adolescence and Risk for Externalizing and Internalizing Psychopathology: A Meta-Analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017, 26, 1409–1422. [CrossRef]

- Demkowicz, O.; Panayiotou, M.; Qualter, P.; Humphrey, N. Longitudinal Relationships across Emotional Distress, Perceived Emotion Regulation, and Social Connections during Early Adolescence: A Developmental Cascades Investigation. Dev Psychopathol 2024, 36, 562–577. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Qi, D.; Shek, D.T.L. Reciprocal Association Between Negative Emotion Mindset and Quality of Life: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study Among Children and Adolescents. Child Ind Res 2025. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, Y.; Lai, W.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Zhu, L.; Shi, J.; Guo, L.; Lu, C. Reciprocal Relationships between Self-Esteem, Coping Styles and Anxiety Symptoms among Adolescents: Between-Person and within-Person Effects. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2023, 17, 21. [CrossRef]

- Šambaras, R.; Butvilaitė, A.; Andruškevič, J.; Istomina, N.; Lesinskienė, S. How to Link Assessment and Suitable Interventions for Adolescents: Relationships among Mental Health, Friendships, Demographic Indicators and Well-Being at School. Children 2024, 11, 939. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Goodman, R. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Scores and Mental Health in Looked after Children. Br J Psychiatry 2012, 200, 426–427. [CrossRef]

- Dudok, R.; Pikó, B. Serdülők Rizikómagatartása a Pszichológiai Jóllét, Valamint a Képességek És Nehézségek Tükrében. mped 2024, 124, 89–110. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, Reliability Indices, and Group Differences for the Study Measures (n = 395).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, Reliability Indices, and Group Differences for the Study Measures (n = 395).

| Variables |

Items |

Cronbach’s α |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

M (SD) |

Group Differences |

| KIDSCREEN-10 |

10 |

0.80 |

-0.54 |

0.32 |

37.17 (5.98) |

G < B**; Y > O**;

Int** |

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) |

20 |

0.75 |

0.56 |

0.12 |

12.11 (5.61) |

Y < O***; Int* |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) |

14 |

0.86 |

0.15 |

-0.20 |

25.57 (9.12) |

Y < O**; Int* |

| General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) |

10 |

0.89 |

-0.63 |

1.09 |

29.71 (5.56) |

ns |

| Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) |

10 |

0.83 |

0.23 |

-0.40 |

16.88 (7.36) |

G > B**; Y < O** |

| Reflective Functioning Questionnaire for Youth (RFQY-5) |

5 |

0.77 |

-0.53 |

0.06 |

22.86 (4.08) |

G > B***; Y < O*** |

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlations between predictor, moderator, outcome, and control variables in boys and girls.

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlations between predictor, moderator, outcome, and control variables in boys and girls.

| |

KIDSCREEN10 |

SDQ |

PSS |

GSE |

CAMM |

RFQY5 |

| KIDSCREEN-10 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) |

-0.63*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) |

-0.61*** |

0.66*** |

— |

|

|

|

| General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) |

0.38*** |

-0.38*** |

-0.44*** |

— |

|

|

| Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) |

-0.45*** |

0.59*** |

0.59*** |

-0.23*** |

— |

|

| Reflective Functioning Questionnaire for Youth (RFQY-5) |

0.16** |

-0.21*** |

-0.10* |

0.23*** |

0.00 |

— |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).