Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Access and Equity

- Pedagogical Transformation

- Epistemological Foundations

- Student Agency and Role

- Teacher Role and Professional Identity

- Institutional and Systemic Effects

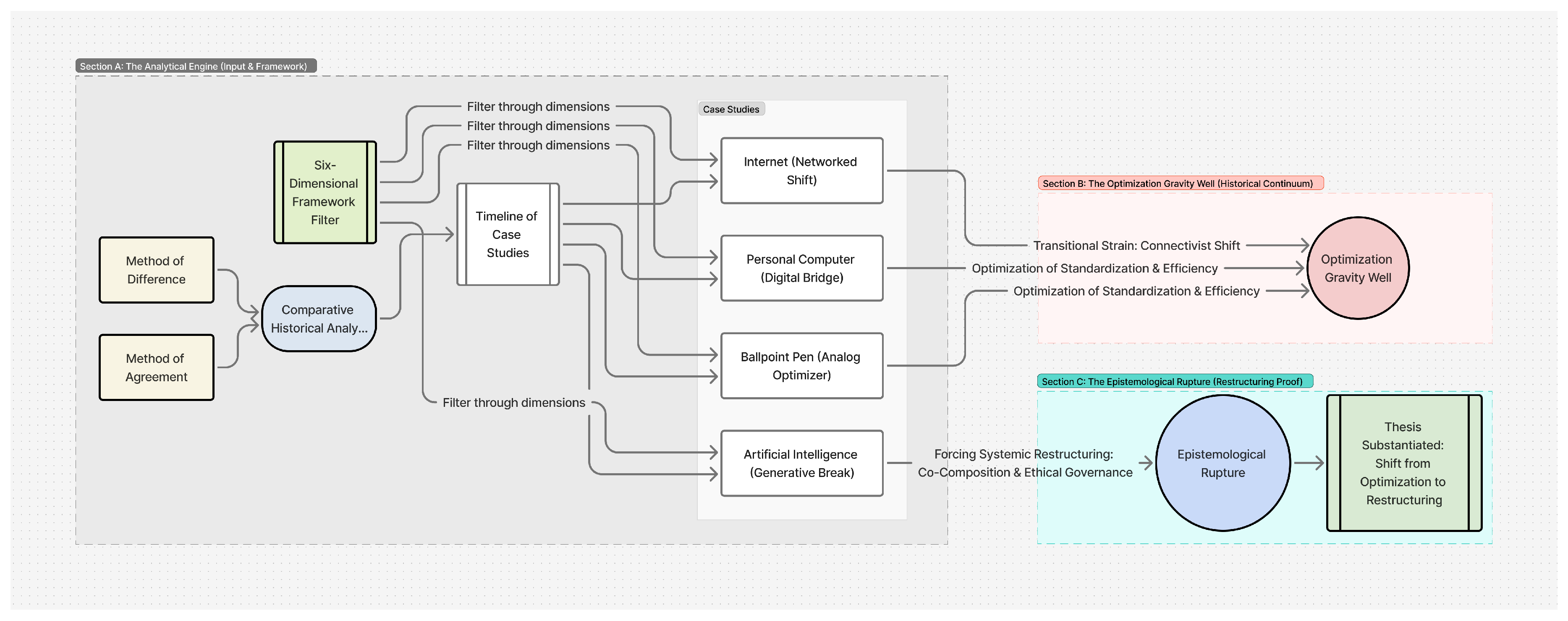

2. Methodology

2.1. Methodological Foundation

2.2. The Six-Dimensional Analytical Framework

- Access & Equity: This dimension differentiates between the technological accessibility as a material (access), and as a service that provides differentiated resources, and support that is designed to assure that all students benefit (equity). To evaluate how a technology may contribute to inclusive education, we look at how effectively barriers to meaningful participation are removed, and how many perspectives can be incorporated; how many participants engage [19].

- Pedagogical Transformation: This dimension measures a significant transformation in teaching methodologies, learning objectives, and the interaction of students in the classroom. It traces the shift from classroom models that are static and structured and instructor-centered (e.g., lectures or rote learning) to a modern model that is individualized, constructivist-oriented, collaborative-oriented (facilitated by technology) [20,21].

- Epistemological Impact: It is the key dimension in affirming the central thesis as it touches upon the most basic questions: What constitutes valid knowledge? and Who is a legitimate knower? Changes in this dimension represent a genuine restructuring in which not only is the relationship between learner and teacher and knowledge that is challenged it is fundamentally disrupted [22].

- Student Agency & Role: This dimension investigates the student’s formation of an identity and autonomy to do something. It describes stages that progress from being a receptacle for intelligence, to the user of the application, to a collaborator in an action, to critique maker, and even to co-composer, in a human-AI connection [23].

- Teacher Role & Professional Identity: Teachers work at levels where their job status as professional change depending on the job role and need and at the very top level the educator’s professional identity. It examines a movement from knowledge transmitter and assessor, to instructional designer and tech expert, to facilitator, curator and, by the end, ethical guide, and learning guide [10,24].

- Institutional & Systemic Effects: This dimension examines macro effects such as: policy changes, demands for infrastructure, economic arguments for investment, and development of new governance challenges including but not limited to data ethics, algorithmic accountability, automation of administrative responsibilities [25].

2.3. Theoretical Evolution

3. Case Studies

3.1. The Ballpoint Pen: Architect of Standardized Assessment

3.2. The Personal Computer: The Co-opted Digital Bridge

3.3. The Internet: The First Epistemological Rupture

4. Results Analysis

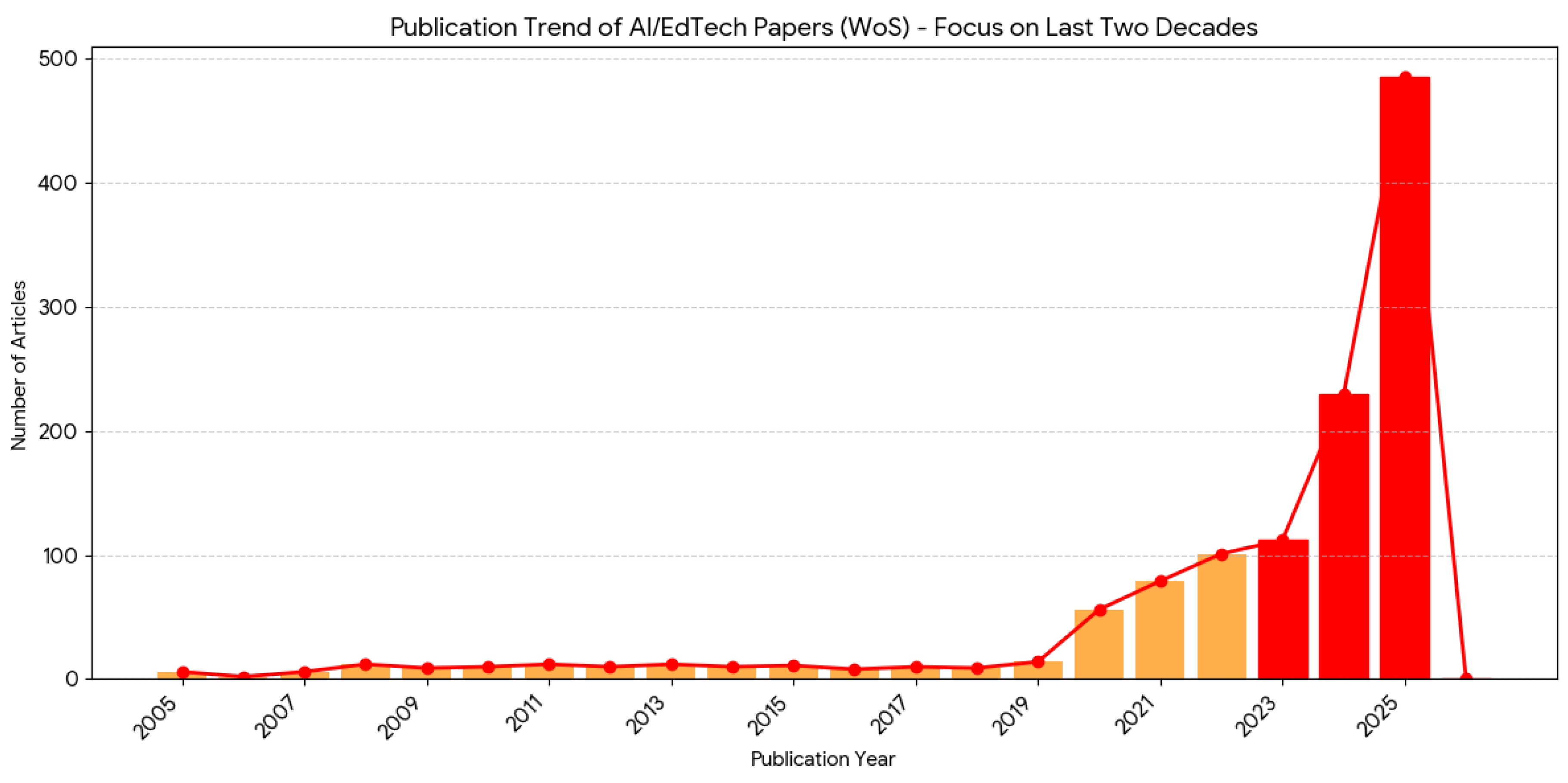

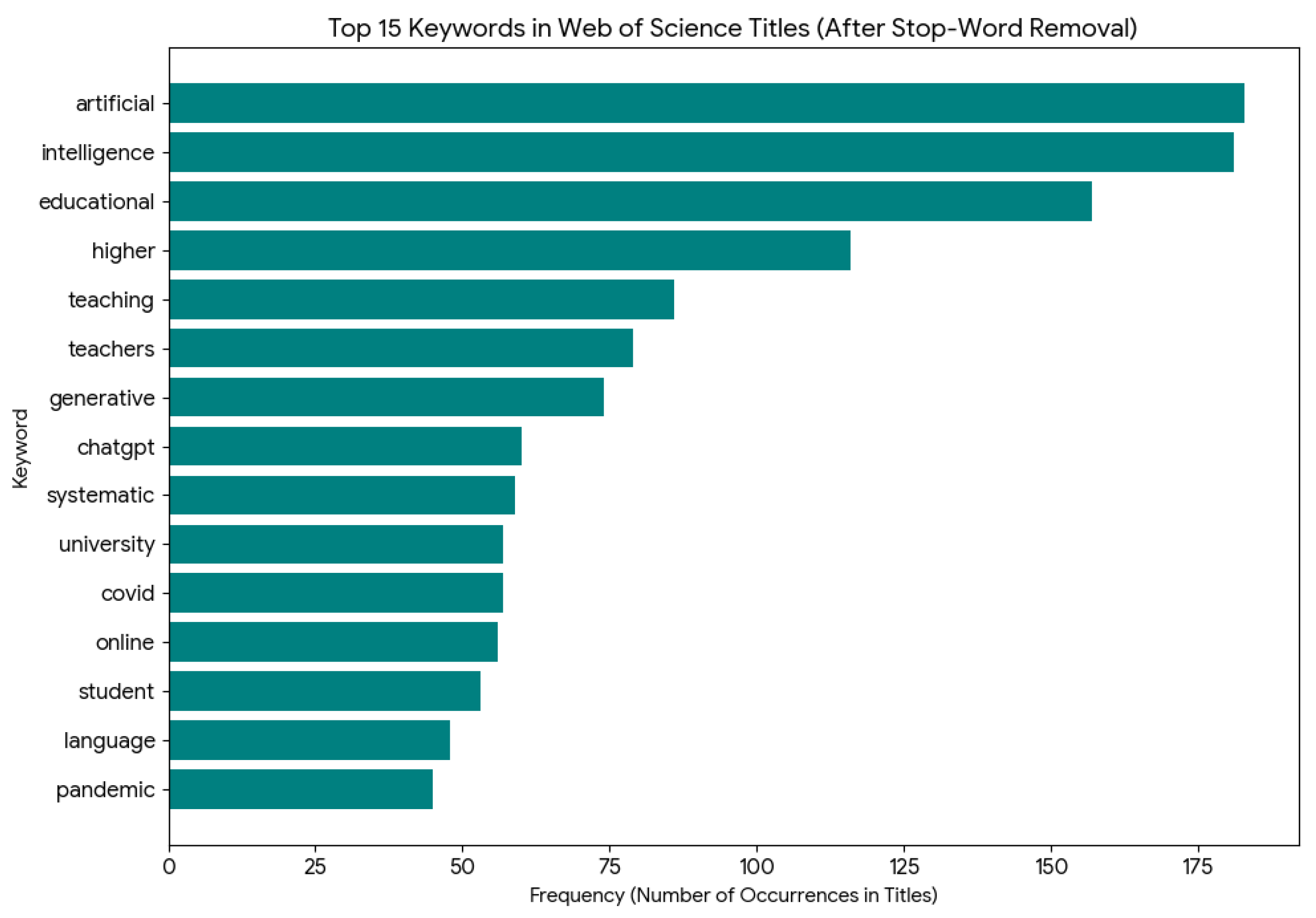

4.1. The Quantitative Shift

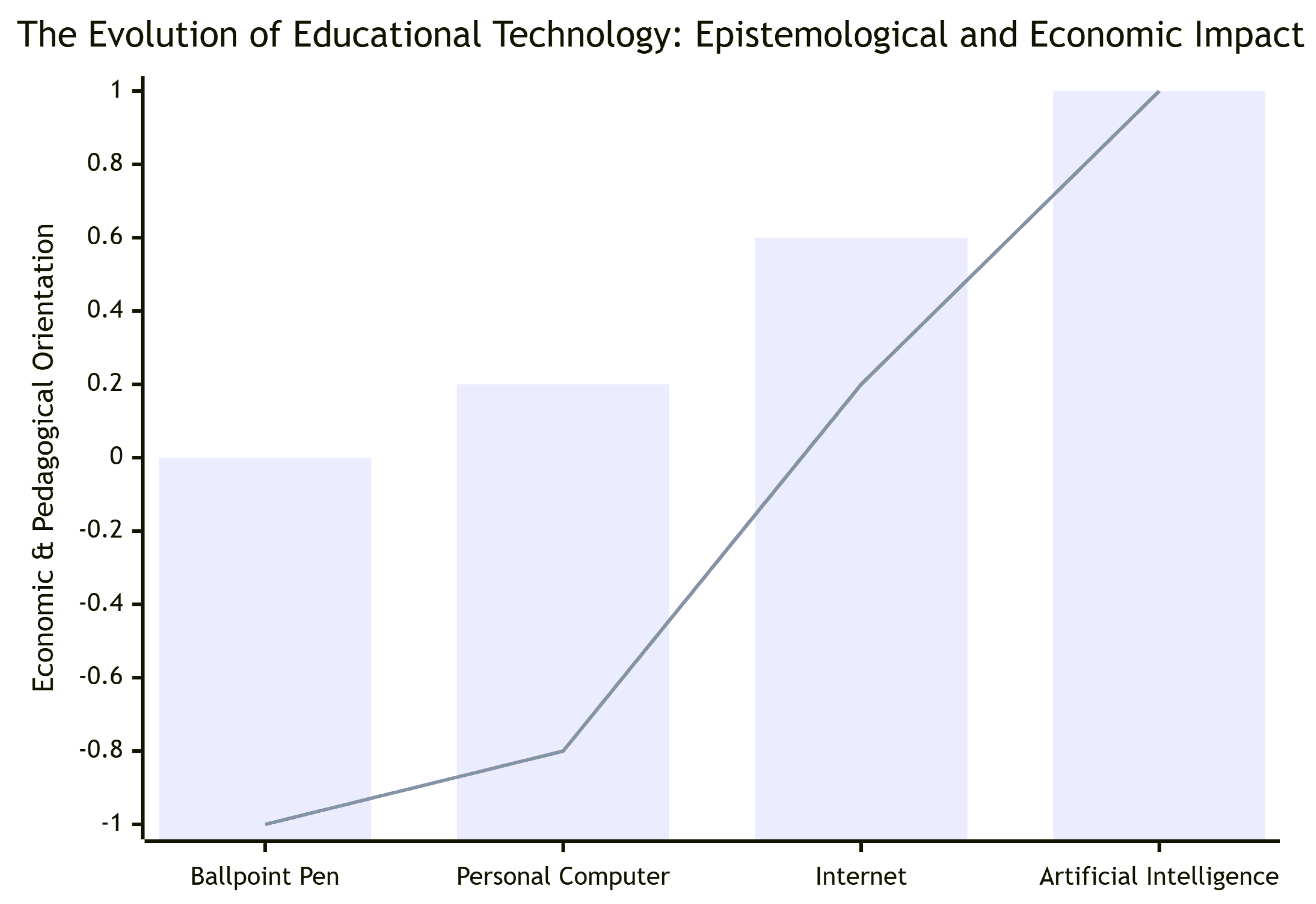

4.2. The Qualitative Rupture

- The Shift in Knowledge Authority (Bar Chart): There is a steady progression from the singular, fixed knowledge authority of the Pen and PC era toward the distributed and now synthetic knowledge authority of the Internet and AI. This represents the epistemological rupture.

- The Shift in Economic Rationale (Line Chart): The economic rationale for technology investment begins firmly in the realm of standardization and efficiency (negative territory for Pen/PC) and, with AI, crosses into the realm of personalization and adaptation (positive territory). This indicates that AI is fundamentally incompatible with the old economic model of education.

4.3. Historical Patterns and the "Optimization Gravity Well"

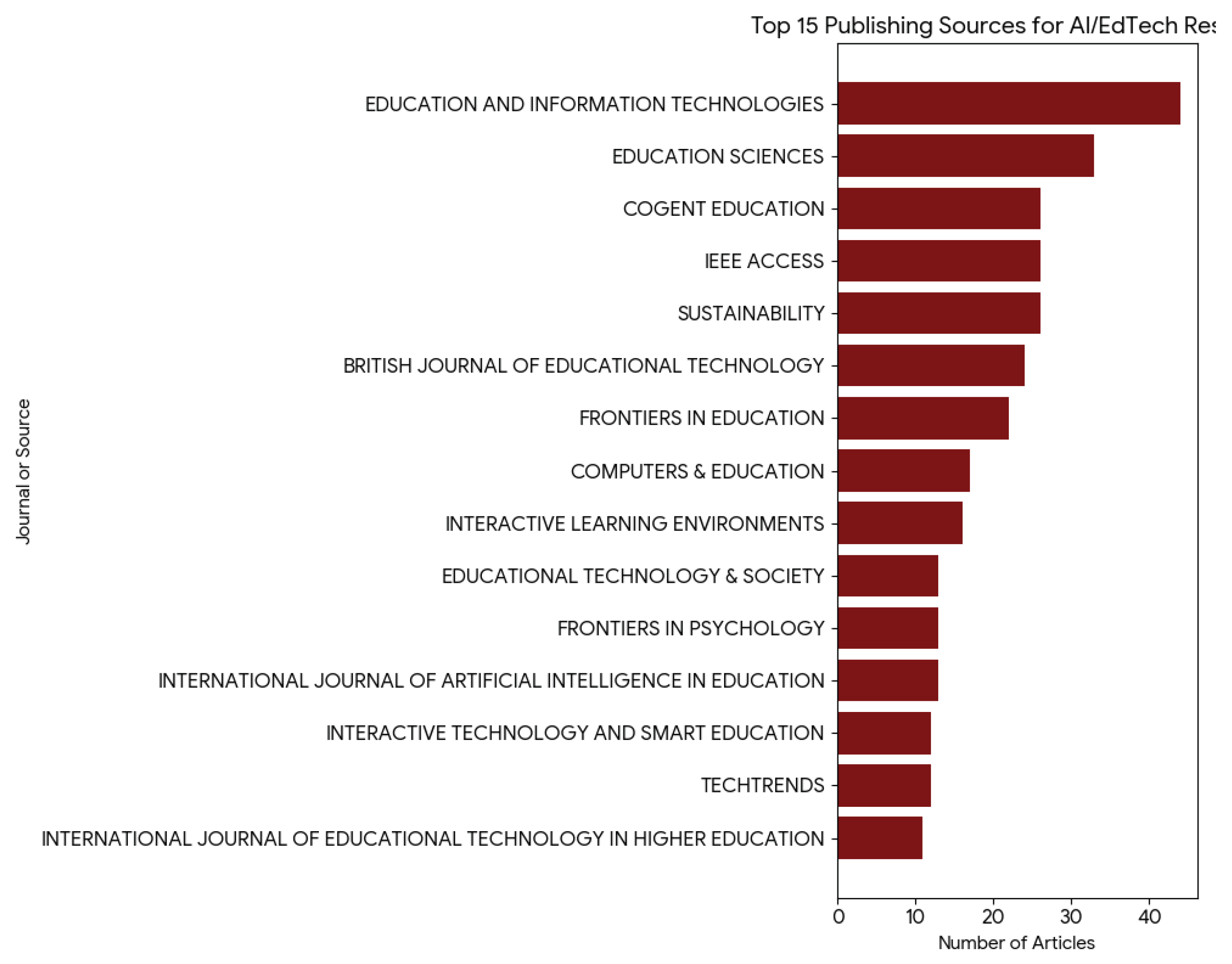

4.4. Bibliometric Framing of the AI Era

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings

5.2. Stakeholder Implications

5.3. Limitations

- Scope and Selection of Technologies: The four technologies that were given special attention of the author, namely the ballpoint pen, personal computer, internet, and AI, had to be used to build a consistent narrative over the course of a century. This is however exclusive to other potent instruments like the radio, television and interactive whiteboards that have also informed pedagogical practice. In turn, our model also offers a simplified, yet not a full-fledged, historical study. Future employment may utilize the six dimensional framework to these other technologies to further experiment and hone the suggested model of optimization versus restructuring.

- Methodological Interpretivism: CHA (Comparative Historical Analysis) approach is not only strong in tracking macro-level trends, but it is also interpretive. The qualitative designation of the labels of the qualitative assignment of Optimization or Restructuring, regardless of the fact that the labels are based on historical evidence and a systematic outline, is scholarly in nature. The six-dimensional framework as is, even though extensive, is a conceptual framework that might fail to reflect all subtle impacts of these complex technologies on different educational settings.

- Generalizability and Context: The analysis is based on the trends that can be observed in the Western and globalized educational system mostly. Technological adoption, resistance and equity issues such as Digital Divide may have very different manifestations depending on the national, cultural, and socioeconomic background. As such, it is possible that the direct generalizability of our results to the educational systems which are run within entirely different philosophical or structural paradigms might be restricted.

- The Changing Character of AI: We can only estimate the effect of AI as it will happen in the future, depending on its abilities and pre-integration. The discipline is changing rapidly, and additional discoveries in the field, such as explainable AI (XAI) [34] or higher-order intelligences, may alter its educational consequences. This research offers a pivotal snapshot and a framework that makes sense, but its decisions have to be complemented with the results of the empirical studies as the technology and its educational use evolve.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allmendinger, J. Educational systems and labor market outcomes. European sociological review 1989, 5, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouska, K.L.; De Jager, N.R.; Houser, J.N. Resisting-Accepting-Directing: Ecosystem Management Guided by an Ecological Resilience Assessment. Environmental Management 2022, 70, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, E. Producing Petty Gods: Margaret Cavendish’s Critique of Experimental Science. ELH 1997, 64, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.S. What is an educational process? In The Concept of Education (International Library of the Philosophy of Education Volume 17); Routledge, 2010; pp. 1–16.

- Reinholz, D.L.; Andrews, T.C. Change theory and theory of change: what’s the difference anyway? International Journal of STEM Education 2020, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, S.; Moukhliss, S.H.; Song, K.; Koo, D. Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Construction Industry Among Undergraduate Construction Management Students: Case Study–A Study of Future Leaders 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dhanaraj, R.K.; Krishnasamy, B.; Rajendran, U.; Sellappan, S.; Jaikumar, R. Generative AI for Personalized Learning: Foundations, Trends, and Future Challenges; CRC Press, 2025.

- Tripathi, P. Initiating an Epistemic Rupture: Exploring Contraceptive Awareness in Janhit Mein Jaari (2022) and Chhatriwali (2023). Journal of International Women’s Studies 2025, 27, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, C.D.; Katz, L.F. The race between education and technology; harvard university press, 2008.

- Gorina, L.; Gordova, M.; Khristoforova, I.; Sundeeva, L.; Strielkowski, W. Sustainable Education and Digitalization through the Prism of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erviana, V.Y.; Rahmawati, A.C. The Influence of 21st Century Professional Competence on the Implementation of TPACK by Elementary School Teachers in Jetis District, Yogyakarta. In Proceedings of the Proceeding Internasional Conference on Child Education. Universitas Muhammadiyah AR Fachruddin, Vol. 1; 2025; pp. 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rizun, N.; Edelmann, N.; Janowski, T.; Revina, A. AI-enabled co-creation for evidence-based policymaking: A conceptual model. In Proceedings of the Conference on Digital Government Research, Vol. 1. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati, S.; Taufikin, T.; Judijanto, L.; Musa, S. Towards Effective Artificial Intelligence-Driven Learning in Indonesian Child Education: Understanding Parental Readiness, Challenges, and Policy Implications. Educational Process. International Journal 2025, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, R.; Sun, Y.; Qin, C.; Zhang, L.; Xu, T.; Zhu, H.; Chen, E. Towards unified representation learning for career mobility analysis with trajectory hypergraph. ACM Transactions on Information Systems 2024, 42, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.; Thelen, K. Advances in comparative-historical analysis; Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Kulanovic, A.; Raghunatha, A.; Nordensvärd, J.; Thollander, P. Analyzing discursive policy leadership using regime narratives in Sweden’s emerging drone transport for sustainability transition. Sustainable Futures 2025, 10, 101387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mill, J.S. The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill; DigiCat, 2022.

- Gebre-Medhin, D.L. Reluctant acceptance of legal solutions to territorial disputes as signals of foreign policy reorientation. Journal of International Relations and Development, S: 1–27. ISBN: 1408-6980 Publisher, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, S. Reimagining the futures of education. PROSPECTS, S: 1–9. ISBN: 0033-1538 Publisher, 0033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.C.; Chang, C.Y. Evaluating self-directed learning competencies in digital learning environments: A meta-analysis. Education and Information Technologies 2025, 30, 6847–6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.; Gul, F.; Dang, B.; Huynh, L.; Tuunanen, T. Designing embodied generative artificial intelligence in mixed reality for active learning in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, T: 1–16. ISBN: 1470-3297 Publisher, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eubanks, V. Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor; Macmillan+ ORM, 2025.

- Luckin, R. Nurturing human intelligence in the age of AI: rethinking education for the future. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal 2025, 39, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceallaigh, T.J.Ó.; Brien, E.O.; Tømte, C.; Kulaksız, T.; Connolly, C. Rethinking teacher education in an AI world: perceptions, readiness and institutional support for generative AI integration. European Journal of Teacher Education 2025, 0, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gupta, P.P. Perspective of Generative AI for UNESCO Inclusive Education, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Flinn, C.M.; Gravatt, B. The efficacy of computer assisted instruction (CAI): A meta-analysis. Journal of educational computing research 1995, 12, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Foster, C. The Use of Virtual Learning Environments in Higher Education—Content, Community and Connectivism—Learning from Student Users. In AI, Blockchain and Self-Sovereign Identity in Higher Education; Jahankhani, H., Jamal, A., Brown, G., Sainidis, E., Fong, R., Butt, U.J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, J.; Heinrichs, D.H.; Camit, M. Artificial intelligence and epistemic interoperability: towards a sympoietic approach. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, T: 1–13. ISBN: 0159-6306 Publisher, 0159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J. Change without difference: School restructuring in historical perspective. Harvard educational review 1995, 65, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaus, G.F.; O’Dwyer, L.M. A short history of performance assessment: Lessons learned. Phi Delta Kappan 1999, 80, 688. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Kwon, K. A systematic review of the evaluation in K-12 artificial intelligence education from 2013 to 2022. Interactive Learning Environments 2025, 33, 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J.L.; Blijlevens, J.; Campbell, A.; Jopp, R. Mastering knowledge: the impact of generative AI on student learning outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, T: 1–22. ISBN: 0307-5079 Publisher, 0307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huey, C.E. The Influence of Storytelling in Art: Mythology and Fairytales. PhD thesis, Mississippi College, 2025. ISBN: 9798293843268.

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; García, S.; Gil-López, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Information fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Ballpoint Pen (20th C) | Personal Computer (20th C) | Internet (21st C Bridge) | Artificial Intelligence (21st C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access & Equity | Democratization of writing tool; Universal standard for output. | Emergence of Digital Divide; access linked to efficiency metrics. | Global connectivity; access to OERs/MOOCs; geographical equity. | Personalized adaptation; risk of data surveillance/bias reinforcement. |

| Pedagogical Transformation | Supported lecture/rote learning; scalable testing. | Enabled CAI/CBT, anchored in behaviorist ISD; structured learning paths. | Connectivism; shift to collaborative, network-based learning; participatory approaches. | Real-time adaptive learning paths; generative feedback loops; shift from transmission to adaptation. |

| Epistemological Impact | Reinforced singular, fixed knowledge and objective assessment. | Knowledge remained hierarchical; retrieval focused. | Knowledge is situated in networks; authority is distributed (decentralization). | Epistemic rupture; shift to co-composition; blurred authorship and knowledge synthesis. |

| Student Agency & Role | Passive recorder/recipient in lecture hall. | Tool user; passive consumption of pre-programmed software (early CAI). | Active information seeker; digital contributor/collaborator. | Critical evaluator; co-creator/partner in knowledge production; focus on applied knowledge. |

| Teacher Role & Identity | Maintainer of standardization; scalable assessor of fixed outputs. | Instructional designer; manager of technology infrastructure; trainer. | Curator of digital resources; facilitator of online interaction; network architect. | Ethical mentor; human contextualizer; analyst of AI-driven insights; focusing on empathy/care. |

| Institutional & Systemic Effects | Enabled standardization of testing and administrative efficiency (Optimization). | Justified by efficiency/productivity goals; reinforced existing systems (Optimization). | Globalized education market; mandated digital skills policy. | Demands new governance (Responsible AI); necessity for system redesign focused on adaptation (Restructuring). |

| Pattern Type | Ballpoint Pen | Personal Computer | Internet | Artificial Intelligence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Resistance Focus | Writing quality/legibility; institutional inertia regarding new tools. | Cost, infrastructure failure, screen time, behavioral distraction. | Information reliability; digital distraction; plagiarism risk. | Fear of cheating; job displacement; loss of human interaction. |

| Normalization Rationale | Universal accessibility; affordability; administrative reliability. | Skill development mandates; administrative efficiency metrics. | Essential for 21st-century workforce skills; global connectivity. | Necessity for hyper-personalization; critical evaluation skills; ethical responsibility. |

| Assimilation Outcome | Standardization of assessment (Optimization). | Digital efficiency and administrative tracking (Optimization). | Decentralization of knowledge/Resource Access (Partial Restructuring). | Fundamental redefinition of knowledge and authorship (Epistemological Rupture). |

| Dimension | Ballpoint Pen (20th C) | Personal Computer (20th C) | Internet (21st C Bridge) | Artificial Intelligence (21st C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access & Equity | O: Democratized tool access | O: Created Digital Divide | O/R: Connectivity Divide & OERs | R: Hyper-personalization vs. data bias |

| Pedagogical Transformation | O: Supported rote learning | O: CAI & drill exercises | R: Connectivism & collaboration | R: Real-time adaptive learning paths |

| Epistemological Impact | O: Fixed, transmitted knowledge | O: Hierarchical, retrieved knowledge | R: Decentralized, networked knowledge | R: Co-composed, synthetic knowledge |

| Student Agency & Role | O: Passive recipient | O: User of pre-programmed software | R: Active seeker & collaborator | R: Critical evaluator & co-creator |

| Teacher Role & Identity | O: Scalable assessor | O: Technology manager & designer | R: Curator & facilitator | R: Ethical mentor & contextualizer |

| Institutional Effects | O: Standardized testing & admin | O: Efficiency & workforce metrics | O/R: Scalable MOOCs & digital policy | R: Demands new ethical governance |

| Cumulative Score (O/R) | 6O / 0R | 6O / 0R | 2O / 4R | 0O / 6R |

| Pattern | Ballpoint Pen | Personal Computer | Internet | Artificial Intelligence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Resistance | Decline of penmanship; cost | Cost; distraction; “edutainment” | Plagiarism; digital distraction | Cheating; job displacement; bias |

| Assimilation Rationale | Administrative reliability & scalability | Workforce skills; efficiency gains | 21st-century skills; global access | Hyper-personalization; necessity for future skills |

| Unintended Consequence | Entrenched standardized testing | The Digital Divide | The Connectivity Divide | Algorithmic bias; data surveillance |

| Final Outcome | OPTIMIZED standardization | OPTIMIZED digital efficiency | PARTIALLY RESTRUCTURED knowledge access | FORCING RESTRUCTURING of core paradigms |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).