1. Introduction

The

Orthopneumovirus, Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

, is an etiological agent in infant lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) producing substantial morbidity globally [

1], representing the most common cause of pediatric hospitalizations [

2]. More importantly, children hospitalized with RSV-LRTI exhibit persistent reductions in lung function, utilize health care resources at greater rates [

3,

4,

5,

6], exhibit persistent obstructive airway disease as young adults [

7] and are at a 2-fold increased risk of premature death from respiratory disease [

5]. Interpreted with the findings that post LRTI show greater incidence of aeroallergen sensitization [

3], these findings suggest early life RSV LRTI is associated with structural and immunological remodeling of the airways.

Upon initial infection, RSV replicates throughout the epithelium; as the virus RSV disseminates into the lower airway epithelium, its replication produces mucosal injury, barrier disruption and activation of innate immunity, triggering remodeling pathways [

8,

9,

10]. Because high levels of RSV replication are associated with enhanced disease severity and longer hospitalization in naïve infants [

11,

12], innate responses of small airway epithelial cells play a critical role in determining disease outcome [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, the role of the epithelial innate immunity in determining long-term outcomes of RSV LRTI is not fully understood.

In infections involving the lower airway, RSV replication produces ciliated cell sloughing, resulting in disruption of the epithelial surface [

9], activating progenitor cell populations to initiate repair. Depending on the location and severity of injury, progenitor cells arise from distinct mesenchymal niches. In the terminal alveoli, alveolar type (AT2) stem cells normally repopulate the AT1, but this population does not repopulate the distal bronchioles [

19]. Studies using models of distal small airway injury have identified distinct progenitor populations in the parenchyma that are recruited to expand and repopulate the lower airway and alveoli. These progenitors are derived from a population of secretoglobin (Scgb1a1)-expressing basal cells primarily within the broncho-alveolar duct junction, where they can contribute to ~50% of the distal alveolar population [

20]. Spatial transcriptomics and single cell RNA Seq (scRNA-Seq) studies have found that that

Scgb1a1+ progenitor cells are maintained in mesenchymal niches engaged in trophic interactions with Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor (PDGFR)a –expressing fibroblasts [

21]. These mesenchymal interactions not only maintain “stemness” of progenitor cells, but also participate in their expansion in response to injury [

21,

22]. The identity and source of progenitor epithelial populations in RSV-induced lung injury are not known.

Previously, we found that the

Scgb1a1- expressing progenitor lineage is one of the major sentinel cells that initiate inflammatory responses to RSV infections in the lower airways [

23,

24]. Here, intracellular RSV replication activates the NFkB/RelA pathway induce secretion of Th2-polarizing chemokines, type I/III interferons (IFN) and mesenchymal growth factors [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. RelA conditional knockout (CKO) in

Scgb1a1 progenitors show significantly reduced neutrophilic inflammation, epithelial-dependent chemokine expression and myofibroblast expansion in response to RSV [

23]. These data place RelA signaling in

Scgb1a1 progenitors as central to a coordinated innate and inflammatory response to lower airway viral infection. The role of

Scgb1a1 progenitors in RSV infection-induced repair and remodeling has not been explored.

Viral infections prior to adult epithelial differentiation produce distinct structural remodeling responses known as post-viral lung disease (PVLD) [

32,

33,

34]. Reasoning that RelA signaling in the

Scgb1a1 progenitor cell may play a role in epithelial remodeling in RSV-PVLD, we established a model of RSV-PVLD and investigated the effect of RelA CKO in a mouse model. Here we report that RSV-PVLD reduces gas exchange along with inducing epithelial thickening. To investigate this process further, scRNA-Seq was utilized which shows that RSV induces an accumulation of atypical alveolar type 2 (aAT2) cells expressing Tumor related protein (TRP63+) and Integrin (ITG)a6b4, characteristic of differentiation-intermediate transitional cells [

20]. Furthermore, lineage tracing of

Scgb1a1-derived progenitors using GFP tagging shows that RSV infection induces this population to appear in the alveolar parenchyma that express TRP63+ cells and exhibit persistent RSV glycoprotein expression. Differential gene expression analysis later confirmed that RSV-PVLD disrupts an aAT2 epithelial-PDGFRa+ mesenchymal niche through upregulation of inflammatory clock genes. Using probabilistic cell-cell communication inference, we infer that RSV disrupts trophic mesenchymal-epithelial signaling pathways, including an angiopoietin-like (ANGPTL) pathway. This data provides new mechanistic insights into the role of innate epithelial signaling in RSV PVLD by identifying the

Scgb1a1 progenitor as a target for persistent RSV replication and dysregulated inflammatory clock gene expression.

3. Results

3.1. Acute RSV Infection Induces Phenotypic Changes in Distal Airway and Alveolus

In the lower airway, RSV replicates in ciliated epithelial cells initiating innate responses and cell sloughing resulting in airway obstruction [

40]. To determine this effect in vivo, mice in the C57BL6/J strain were acutely infected with RSV intranasally. The C57BL6/J stain was selected because this strain exhibits a robust remodeling response driven by innate, and Th1 immunity [

41]. Four days later, at the peak of RSV transcription (

Figure 1A), mice were euthanized. Similarly RSV infection induced a 30-fold ± 7.9-fold (P<0.01, n=4) population of CD68+ macrophages had infiltrated the airspaces, confirming the host response to infection (

Figure 1B,C). Examination of the small airways showed an abundant population of ciliated of acetyl Tubulin+ ciliated epithelial cells in the Mock-infected mice (

Figure 1D). By striking contrast, the population of ciliated epithelial cells was reduced in the RSV-infected mice to ~70% (P<0.05, n=4;

Figure 1D, E). These data confirm that acute RSV infection depletes ciliated cells of the lower airway.

We next examined the alveolar airspaces. A robust staining of surfactant protein c (SPC)+ AT2 cells was seen both in Mock and RSV-infected mice (

Figure 1F). By contrast, a striking 1.9 ± 0.1-fold upregulation of the AT1 marker, podoplanin (Pdpn), was observed in the parenchyma of the RSV-infected mice (P<0.05, n=4;

Figure 1F). This change in alveolar cell phenotype was further associated with a significant reduction in the expression of the ITGb4 adhesion protein (

Figure 1F, G), whose loss is associated alveolar inflammation and barrier disruption [

42,

43]. At higher magnification of merged cell images, we noted the presence of SPC and PDPN co-expressing cells (

Figure 1H), suggesting RSV induces a population of alveolar differentiation intermediate cells, previously noted in more severe models of bleomycin and influenza virus-induced airway injury [

20,

44].

3.2. RSV-PVLD Induces Bronchiolar and Alveolar Remodeling

To explore this phenomenon further and determine the mechanistic role of epithelial intrinsic immunity on progenitor expansion in RSV LRTI, we established a PVLD model, where immature (3 week old) homozygous for Scgb1a1Cre recombinase (CreER

TM) X RelA

fl/fl mice in the C57BL6/J background [

25,

26] were Mock-treated (PBS) or infected with RSV (

Figure 2A). Mice were then randomized to vehicle (Corn Oil) or tamoxifen (TMX) treatment, the latter to induce RelA CKO

after the resolution of acute infection (for simplicity in the following section, we refer to corn oil-treated mice as “WT mice” and TMX-treated mice as “RelA CKO”). Mice infected with RSV in both TMX or Oil-treated groups showed reduced weight gain in comparison to Mock treated controls (P<0.01, n=5-6;

Figure 2B).

To confirm RelA CKO was successful, RelA mRNA was measured, where TMX treated mice expressed RelA mRNA at 22% that of Oil-treated mice (0.22 ± 0.11 vs 1 ± 1.1-fold; P<0.01, n=5;

Figure 1C). By contrast, a 9.1 ± 5.3-fold increase in

RelA mRNA expression was seen in RSV-infected WT mice that was significantly reduced by TMX treatment to 2.9 ± 2.8-fold in RSV-infected RelA CKO mice (n=5, P<0.05;

Figure 2C). We also observed RSV-F mRNA was persistently detectable in RSV-infected RelA WT mice with an induction of 129 ± 158-fold relative to mock-treatment, suggesting a persistent, low-level of RSV replication (

Figure 2D). Interestingly, this level of RSV transcription was reduced in RSV-infected RelA CKO mice, suggesting that RelA activation in

Scgb1a1 progenitors was required for viral latency (

Figure 2D). To establish whether RSV affected pulmonary gas exchange, resting O

2 saturation was measured by collar oximeter. In the mock-infected WT mice, ambient O

2 saturation (Sat) was 99 ± 0.3%, whereas O

2 Sat in RSV-PVLD in WT mice was significantly reduced to 97 ± 0.3%, and RelA CKO restored ambient O

2 saturation to 99 ± 0.1 % (P<0.05, n=5-6,

Figure 2E).

H&E staining was performed to better understand the effect of RSV PVLD on structural remodeling and lung architecture. A detailed examination of small bronchioles showed no obvious enhancement of mucous metaplasia or leukocytic infiltration (

Figure 3A). Specifically, we noted that the histology of the mock-infected WT mice was indistinguishable from that of mock-infected RelA CKO mice (

Figure 3A). However, we did notice an increase in epithelial thickness in the small bronchioles in RSV-infected WT mice that was reduced in the RSV-infected RelA CKO mice. To quantitate this feature, bronchiolar thickness was measured radially around the perimeter of each bronchiole (See

Supplementary Figure S2 for further detail). In mock-infected WT mice, the small bronchiolar thickness was 14.6 ± 1.2 mm which was increased to 20.4 ± 4.2 mm in RSV-infected WT mice (P=0.012, n=5,

Figure 2B). By contrast, bronchiolar thickness was reduced in the RSV-infected RelA CKO mice where the bronchiolar thickness was measured at 13.7 ± 2.5 mm (P<0.003, n=5,

Figure 3B). These data indicated that RSV-PVLD induced changes in small airway epithelium in a RelA-dependent manner.

3.3. Expansion of Alveolar Progenitor Epithelial Populations in RSV-PVLD

To better characterize the epithelial atypia, we stained for the presence of reparative progenitor cell markers. We first analyzed expression of the small membrane transporter, aquaporin 3 (Aqp3), a marker of acute lung injury associated with epithelial proliferation and migration [

45]. In WT mice, we observed that RSV infection produced a significant 6.5 ± 2.6-fold increase of

Aqp3 mRNA in lung (P<0.01, n=4;

Figure 4A). This induction was significantly reduced to 1.8 ± 1.1-fold in the RSV-infected RelA CKOs (P<0.01, n=4;

Figure 4A). To examine the tissue distribution of AQP3, immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) was conducted, where increased AQP3 staining was observed in the membrane in small bronchioles, in the basal cell layer, and throughout the alveoli (

Figure 4B). Quantitation of the IFM staining confirmed a 4.5-fold increased AQP3 immunofluorescent signal in RSV-infected WT mice that was normalized by RelA CKO (P<0.01, n=4;

Figure 4C).

We next quantitated tumor related protein 63 (Trp63), a marker of alveolar progenitors responsible for repopulating the alveolus in response to bleomycin injury [

46] and influenza H1N1 infection [

20]. We found RSV induced a 2.9 ± 1.2-fold increase of

Trp63 mRNA in RSV-infected WT mice (P<0.01, n=4) that was significantly reduced in both mock-infected and RSV-infected RelA CKO mice (P<0.01, n=4;

Figure 4D). By IFM, TRP63 was not identified in mock or RSV-infected bronchioles, consistent with other reports [

47]. However, we did observe an increase in TRP63 immunostaining in a patchy distribution throughout the alveolar parenchyma in RSV-infected WT mice. This pattern was reduced in the RSV-infected RelA CKO (Figures 4E, F), indicating TRP63 expression in Scgb1a1+ progenitors is downstream of RelA.

To further explore this finding, we examined the expression of ITG-a6 and b4 isoforms We were particularly interest in this measurement because the expression of ITG is TRP63-dependent, and would therefore serve as a marker of functional TRP63 activity [

48,

49]. We found that RSV induced

Itga6 mRNA by 3.7 ± 1.2-fold in RSV-infected WT mice (n=4, P<0.01,

Supplemental Figure S2), an induction blocked by RelA CKO (

Supplemental Figure S2). In striking contrast to that seen in the acute RSV infection, 5-fold upregulation of

Itgb4 mRNA was observed (

Supplemental Figure S2). Collectively these data indicate that RelA signaling in

Scgb1a1+ precursors is required for expansion of the AQP3+/TRP63+/ITGa6+ epithelial cell progenitors in distal airways in RSV-PVLD.

3.4. scRNA Sequence Analysis of RSV-PVLD Shows Atypical AT2 Populations

To provide greater insight into this coordinated multi-cellular injury-repair process, we conducted scRNA-seq of the RSV-PVLD model. Left lungs from n=4 replicates of each treatment were subjected to 10X Genomics Flex 3’ sRNA sequencing. After QA/QC processing showing that the libraries had 92.7 ± 0.8% fractions of reads mapped to cells, indicating the scRNA libraries had negligible ambient RNA contamination (Supplementary Table S3), an integrated dataset of 104K cells X 14.5K genes was generated. Thirty-five distinct cell types could be resolved based on expression of unique cell signature markers. In WT mice, RSV expectedly induced significant shifts in atypical AT2 cells, B cell and NK populations (Supplementary Figure S3).

Reasoning that expansion of epithelial progenitors in RSV-PVLD was due, in part, to activation of the mesenchymal-epithelial niche controlling epithelial progenitor expansion, we focused the remaining study on determining effects of RSV infection on the epithelial-mesenchymal niche. To accomplish this, the data set was filtered for epithelial and mesenchymal gene signatures and subjected to leiden nearest-neighbor clustering. 32 transcriptionally distinct cellular populations that were assigned based on majority voting of highly expressed markers and manual validation. These groups include a heterogeneous group of surfactant (

Sfpt)-c+/Advanced Glycosylation End-Product Specific Receptor (

Ager)+ atypical AT2 (aAT2) cells, Lysozyme (

Lyz)1+ AT2 cells, proliferating

Mki67+ AT2 cells, keratin 8 (

Krt8)+/

Scgb1a1+ Club cells, AT1 cells,

Pdgfra+ fibroblasts,

Lgr6+ myofibroblasts,

Itgb4+ progenitors (Prog) and hypoxia factor (

Hif)1+ pericytes (Peri,

Figure 5A). An initial analysis of cell populations affected by RSV was identified by coloring the cells in the UMAP by treatment condition

(Figure 5B). We noted that RSV infection in the vehicle-treated animals shifted subpopulations in the aAT2, Club,

Krt8+Club and

Hif+ Peri cell groups. RelA CKO affected

Hif+Peri,

Pdgfra+ Fibro and aAT2 populations (

Figure 5B).

To identify the cell populations targeted for RelA CKO, Scgb1a1 mRNA expression was overlaid on the UMAP representation. Here, we observed Krt8+ Club, and Club cells were strongly positive as expected (Figure 5C). Similarly, aAT2, proliferating (Mki67+) AT2 and lysozyme (Lyz)1+AT2 cells were strongly surfactant protein C positive (Sfptc+), confirming their identification at AT2 cells (Figure 5D).

Hierarchial clustering of the most highly variable genes was next performed to confirm assigned cellular phenotypes. Here, AT2,

Mki67+AT2 and

Lyz+AT2 cells co-clustered based on shared high levels of expression of the

Sftp isoforms, including

Sftp-c and

-d expression (

Figure 5E). Interestingly, we noted aAT2 cells co-expressed

Ager, the classical cell marker of AT1 cells (

Figure 5E). A separate cluster included

Itgb 4+ progenitors, Club- and

Krt8+Club cells that exhibited high levels of

Scgb1a1 and

Scgb3a2 expression (

Figure 5E). Also AT1 cells expressed

Ager mRNA as well as the HOP Homeobox (

HopX), a marker of AT2 progenitor responsible for regeneration of alveoli after hyperoxic injury [

50].

A dot-plot clustering of cell types indicated the aAT2, Krt8+Club, Itg+ progenitor and club cells had similar transcriptional profiles and grouped separately from the fibroblast and myofibroblast populations (Figure 5F). These data indicated that RSV-PVLD induced aberrant populations of lower airway cells in intermediate differentiation states.

We next examined changes in cell populations using cell frequency analysis for each cell type by treatment condition. RSV infection induced increases in AT1 and Fib populations, but decreased

Lgr6+Fibro,

Mki67+AT2 and SMC populations (

Figure 5G). By contrast, in the RSV-infected RelA CKO mice, increases in the

Hif+ Peri and aAT2 cells were seen relative to RSV-infected WT, along with decreases in

Itgb4+ Prog,

Krt8+Club and Fib populations were seen (

Figure 5G). These data indicate not only does RSV PVLD induce shifts in epithelial cell differentiation states but unanticipatedly,

Scgb1a1-directed RelA CKO influences mesenchymal (fibroblast and pericyte) populations. Since the

Lgr6-expressing fibroblast population is trophic for expansion of

Scgb1a progenitors [

51,

52], RSV-PVLD may affect the number or function of these crucial epithelial-mesenchymal niches.

3.5. Scgba1a1 Progenitors Contribute to the aAT2 Population in RSV-PVLD

To more clearly establish the fate of the

Scgb1a1+ progenitor population in RSV-PVLD, we next conducted cell lineage tracing studies by tagging

Scgb1a1-expressing cells with GFP using heterozygous

Scgb1a1-CreER

TM X dimer Tomato (mT)-membrane-targeted green fluorescent protein (mG) mouse (mTmG) strain. These mice express WT levels of RelA and can be used to track the cellular lineage using the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter. All cells in the mT/mG mouse express Tomato, a red fluorescence protein, prior to Cre activation. In response to Cre activation, expression of Tomato is silenced and GFP is induced, enabling identification of

Scgb1a1+ progenitors. Our previous light sheet microscopy studies using

Scgb1a1-CreER

TM X mTmG mice mapped

Scgb1a1 progenitors as widely and uniformly distributed throughout the small bronchiolar epithelium [

26]. We therefore subjected heterozygous

Scgb1a1-CreER

TM X RelA

fl/fl X mTmG mice to RSV PVLD and labeled the

Scgb1a1+ progenitor population after RSV infection (Schematically shown in

Figure 6A).

In either Mock or RSV-infected mice, GFP+

Scgb1a-derived progenitors populated the small bronchioles, consistent with the role of these self-replicating cells as progenitors of secretory goblet and ciliated cells [

53] (

Figure 6B). We next examined the population of GFP+

Scgb1a in the alveoli. Here, we observed a low level of GFP+ cells consistent with presence of

Scgb1a1 expressing cells in alveoli [

53] (

Figure 6B, bottom). We further noted that this population increased with RSV-PVLD. Quantification of the GFP+ cell population showed RSV infection induced GFP fluorescence from 0.96 ± 0.14 to 1.2 ± 0.09 arbitrary fluorescence units (n=4, P<0.01,

Figure 6C).

To determine whether these progenitors were replicating RSV or contributed to the TRP63+ population, we conducted immunofluorescence assays. Here, we found that the alveolar GFP+ population was positive for RSV F protein expression, where we observed an increase in RSV F glycoprotein staining (Figure 6D). Relative to Mock, where no RSV F staining could be detected, RSV F staining in GFP+ cells increased in the RSV-infected mice to 4.18 ± 0.5-fold (n=4, P<0.001, Figures 6D, F). We also noted GFP+ alveolar parenchymal populations co-stained with TRP63, where a 1.62 ± 0.11-fold increase in TRP63 staining was quantitated (n=4, P<0.001, Figures 6D, E). Collectively, these data indicate that Scgb1a1+ progenitor cells are a direct target of RSV replication and that RelA signaling mediates cell state transitions into atypical TRP63+ progenitors in the alveolar epithelium.

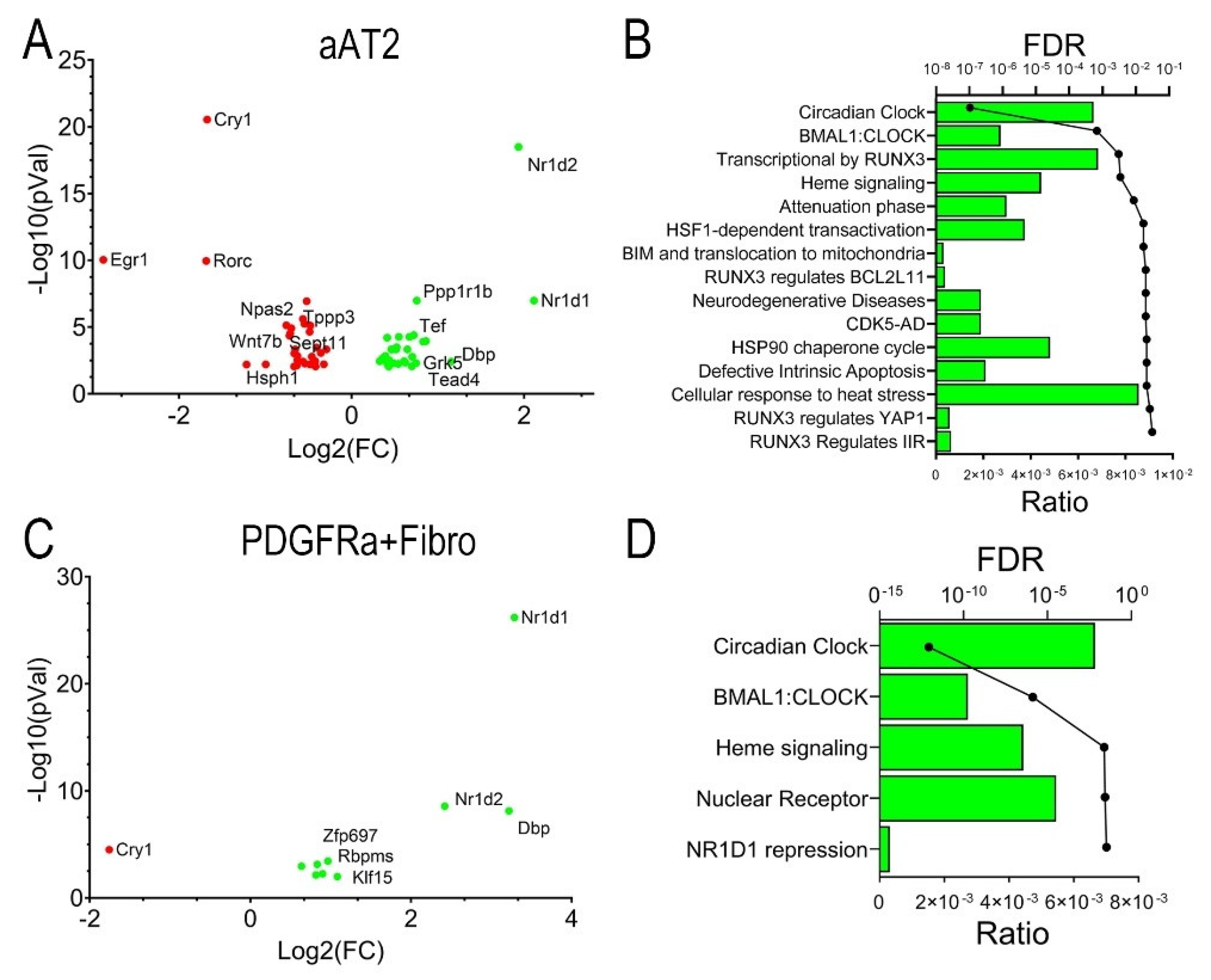

3.6. RSV-PVLD Dysregulates Inflammatory Clock Genes in the Alveolar-Mesenchymal Niche

Distal airway progenitors are engaged in bidirectional trophic interaction with fibroblast populations in spatially resolved “niches”. In the distal parenchyma,

Scgb1a1+ progenitors are engaged with trophic interactions with PDGFRa+ fibroblasts to maintain stem cell properties [

21]. To further explore the effect of RSV infection in alveolar cell atypia, a differential gene expression (DEG) analysis of individual cell groups was conducted using pseudobulk analysis and DESEQ2 to minimize false positives [

54]. We identified DEGs in aAT2 cells for mock-infected vs RSV-infected WT mice. 64 DEGs were significantly changed at an absolute value of log2FC >1.5 and adjusted p-value (pAdj) of <0.01. These genes were plotted in a Volcano plot representation where nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member (

Nr1d)-2 and -1 genes, also known as REV-ERB-b/a key regulators of inflammatory clock genes were identified as being the most highly upregulated by RSV infection, with a reduction in Cryptochrome Circadian Regulator 1 (

Cry1) and Early growth response 1 (

Egr1) mRNAs (

Figure 7A). A genome ontology analysis identified that the most highly affected biological pathway was that of circadian clock, as well as RUNX3 signaling, heat shock factor (HSF1) transactivation and others (

Figure 7B).

A similar analysis was conducted for the Pdgfr1a+ fibroblasts. Here, RSV affected 66 genes at the same stringent cut-off values. Intriguingly, Nr1d1 was the most highly induced, along with D-Box Binding PAR BZIP Transcription Factor (Dbp) and Nr1d2, along with a downregulation of Cry1 (Figure 6C), mapping to a highly enriched circadian clock pathway (Figure 7D). Collectively, these data indicate that RSV-PVLD is associated with dysregulation of inflammatory circadian clock genes in both aAT2 epithelial cells and Pdgfra+ fibroblasts.

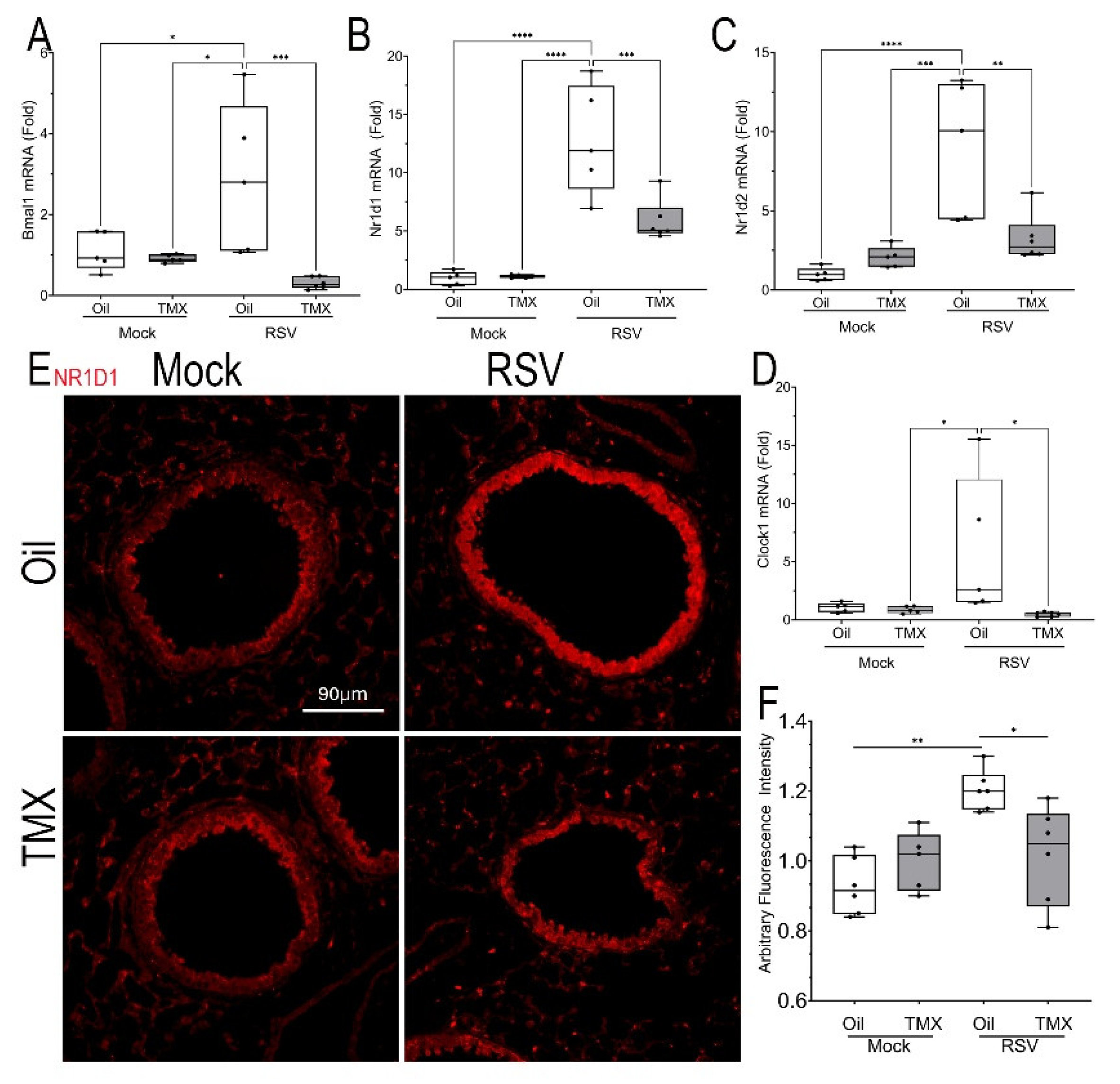

The effect of RSV-PVLD on

Bmal was validated using Q-RTPCR. Here, we observed that RSV infection induced

Bmal mRNA expression by 2.87 ± 1.9-fold in WT mice (n=4, P<0.05,

Figure 8A), and induction which was reduced to 0.31 ± 0.44-fold in RSV-infected RelA CKO (n=4, P<0.05,

Figure 8A).

Nr1d1 mRNA expression was dramatically upregulated to 12.8 ± 0.44-fold in RSV-infected WT mice (n=4, P<0.0001,

Figure 8B), and reduced in the RSV-infected RelA CKO mice to 5.8 ± 1.8-fold (n=4, P<0.001,

Figure 8B). Similar patterns of RSV induction and inhibition by RelA CKO were observed for the 9.1 ± 3.2 -fold induction of

Nr1d2 mRNA and 5.9 ± 6.2-fold

Clock mRNAs (

Figures 8C, D).

To confirm upregulation of NR1D1, we conducted IFM where a 1.6-fold increase in NR1D1 expression could be identified in RSV infected WT mice predominately in the bronchioles and to a lesser extent in the alveoli, an induction reduced by the RelA CKO (Figures 8E, F). Collectively these data indicate that RSV-PVLD is associated with dysregulated inflammatory clock gene expression.

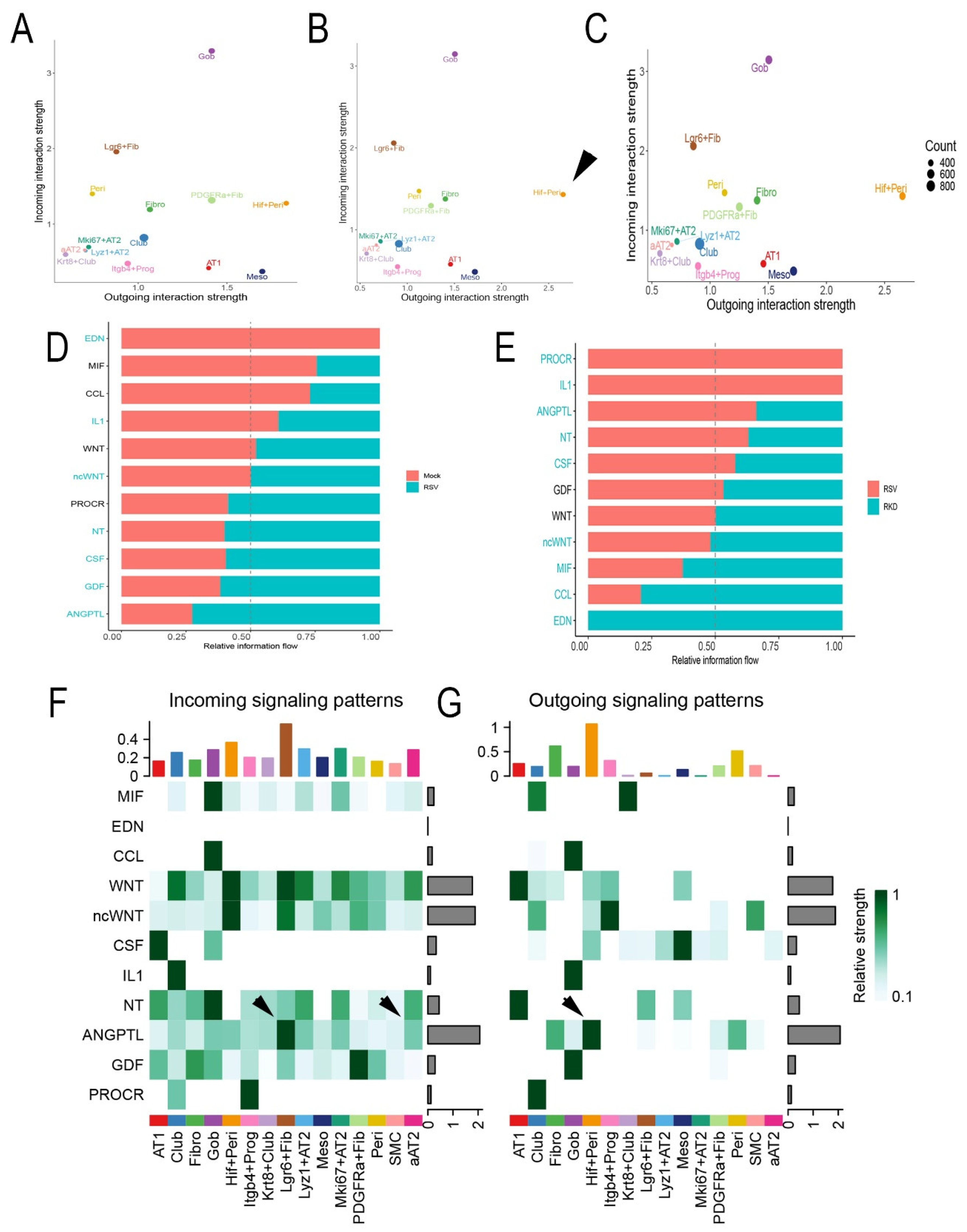

3.7. RSV Disrupts Intercellular Epithelial-Mesenchymal Signaling Networks

Trophic mesenchymal-epithelial interactions mediate progenitor epithelial cell differentiation and myofibroblast expansion in response to injury through secretion of matricellular and soluble growth factors [

21]. Our collective findings that RSV-PVLD induces changes in epithelial mesenchymal populations and their phenotypes, suggested to us that RSV infection may affect these trophic signaling networks. To better understand this, we conducted a systematic inference of epithelial-mesenchymal cell-communication networks. Here, scRNA-seq data was analyzed using a validated, probabilistic method that incorporates expression of secreted factors, their receptors and co-receptors across a manually curated database of >2,000 interactions [

55].

We individually analyzed each treatment condition for dominant “senders” (those cells producing factors) and “receivers” (those cells expressing cognate receptors and co-factors). These data were plotted into a 2-dimensional representation of outgoing signals vs incoming signals (

Figure 9). In mock-infected WT mice, the dominant cell types producing outgoing signals included Goblet cells (Gob) and

Lgr6+ alveolar fibroblasts (

Lgr6+ Fib,

Figure 9A). We paid particular attention to this effect in

Lgr6+ Fib population as epithelial trophic signaling is important for its known role supporting small airway epithelial progenitors [

21]. By contrast, in RSV-infected WT mice,

Hif1+ Peri cells were highly induced to produce outgoing messages (arrowhead,

Figure 9B). In the RelA CKO, the outgoing signals of Hif1+ Peri population were unchanged relative to RSV-infected WT mice (

Figure 9C).

Intercellular signaling intensity for specific pathways were determined by condition and cell type and displayed as an information flow bar chart (

Figure 9D). In mock-infected WT mice, endothelin (EDN), Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF) and CC chemokine ligand (CCL) pathways were the highest fraction observed (

Figure 9D). By contrast, CSF, growth differentiation factor (GDF) and angiopoietin-like (ANGPTL) pathways emerged as the top enriched pathways in RSV-infected vehicle-treated mice (

Figure 9D). Of these, ANGPTL4 signaling was noted because mesenchymal ANGPTL signaling controls intestinal stem cell regeneration and fibroblast expansion in response to lung [

56] and intestinal injury [

57]. By contrast, a distinct pattern of information flow was observed in the RSV-infected WT vs RelA CKO. Here, protein kinase c receptor (PROC), IL1 and ANGPTL signaling emerged as the top pathways in RelA CKO, along with ANGPTL4 (

Figure 9E).

To better understand the intercellular signals converting on the aAT2 population, we analyzed incoming signals as a function of cell type for mock and RSV infected WT mice. These data are displayed as a heat map, where a significant enhancement of ANGPTL signaling was seen in the RSV infected cells as an incoming signal for the Lgr6+ fibroblasts and aAT2 cells (arrowheads, Figure 9F). The majority of cell types producing ANGPTL4 were Hif1+ Peri and Fibro (arrowheads, Figure 9G). Collectively we interpreted these data indicates that RSV PVLD is associated with dysregulated mesenchymal ANGPTL4 signaling from Hif1+ Peri to Lgr6+ alveolar fibroblasts and the aAT2 cell population.

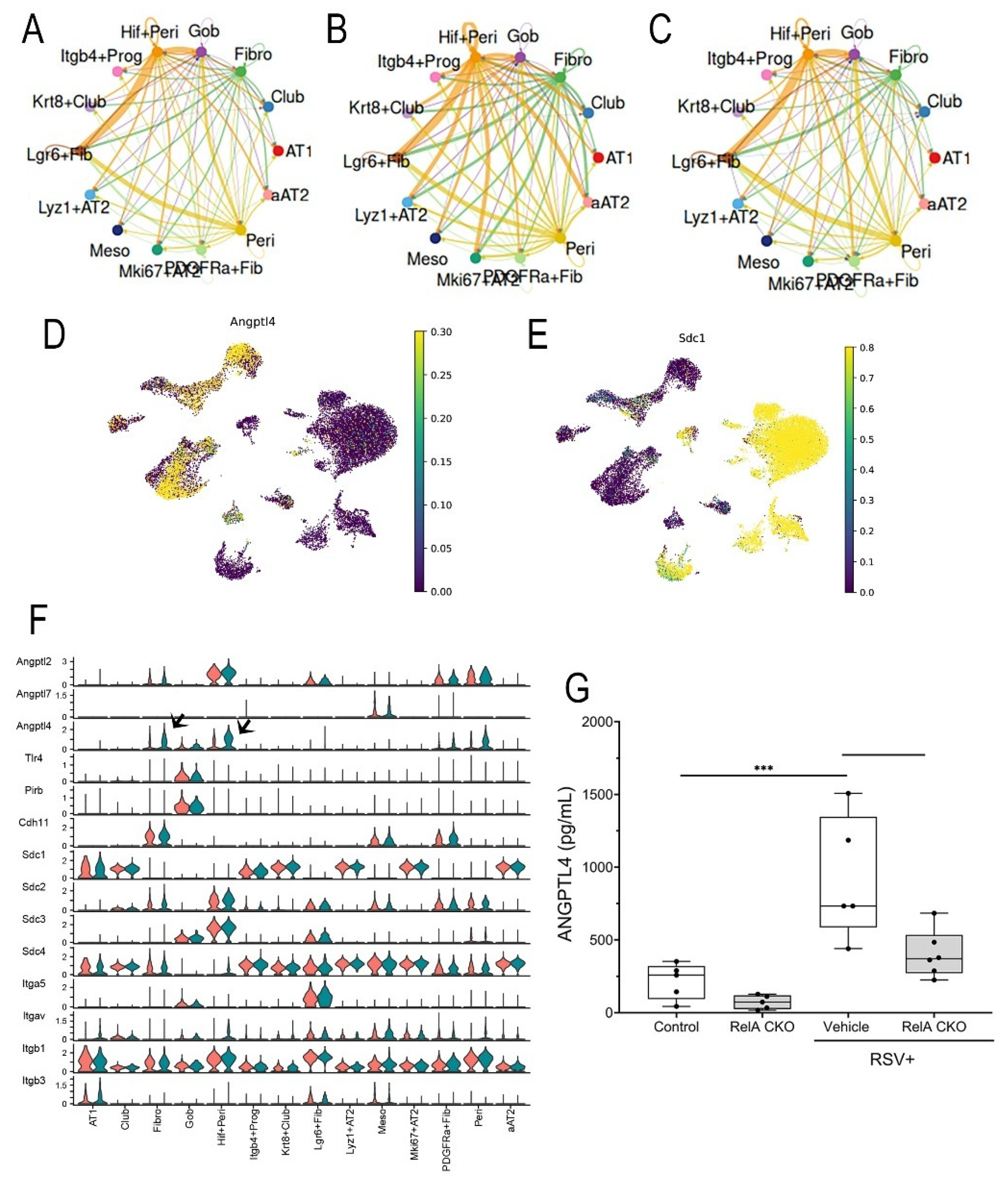

3.8. RSV Dysregulates Mesenchymal-Epithelial ANGPTL Signaling

To better understand the intercellular signaling network of ANGPTL in RSV-PVLD, we analyzed the strength of ANGPTL signaling between individual cells as a function of treatment. In mock-infected mice, autocrine ANGPTL is produced by

Hif1+Peri cells that signal to both

Lgr6+ Fib and Goblet cells (

Figure 10A). By contrast, ANGPTL signaling intensity is increased in RSV-infected mice where

Hif1+Peri signaling to aAT2 cells becomes prominent, as well as ANGPTL signaling increases in Fibro to aAT2,

Mki67+AT2,

Lyz+AT2 and

Lgr6+ Fibroblasts (

Figure 10B). In RelA CKO, the ANGPTL patterns largely return to those of mock-infected controls (

Figure 10C). In airway epithelial cells, syndecan-1 (Sdc1) is the dominant ANGPTL4 receptor. Overlaying

Angptl4 and

Scd1 expression patterns in UMAP, we observed that that

Hif1+ Peri and

Pdgfra+ Fibro cells express

Angptl4 (

Figure 10D), whereas aAT2 and

Krt8+Scgb1a+ Club cells have the highest

Scd1 expression (

Figure 10E), further suggesting the presence of mesenchymal-epithelial ANGPTL signaling.

To systematically identify the ligands and receptors in the ANGPTL pathway, the levels of expression for each in RSV-infected vehicle-treated vs control mice were quantified and plotted as violin plots. Although Angptl2 mRNA was constitutively expressed in mesenchymal cells, Angptl4 mRNA was upregulated in RSV-infected Fibro and Hif+Peri (arrowheads, Figure 10F).

Finally, the level of ANGPTL4 protein in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was measured by ELISA. Here we observed BALF ANGPTL4 concentration was 217 ± 123 pg/mL in mock-infected mice that rose 4.2-fold to 920 ± 424 pg/mL in RSV-infected mice (P<0.001, n=5; Figure 10G); this induction was reduced by ~50% to 404 ± 163 pg/mL in RelA CKO mice (P<0.01, n=5; Figure 10G). These data indicate that RSV activates ANGPTL4 signaling at the level of ligand expression.

Figure 1.

Acute RSV induces epithelial phenotypic changes. Heterozygous Scgb1a1-CreERTM X RelAfl/fl in the C57BL6/J background were mock infected (both sexes) were mock or RSV infected via the i.n. route. 4 d later, mice were euthanized for Q-RT-PCR and immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM). (A), Q-RT-PCR for RSV F mRNA. Shown are fold changes in RSV mRNA with mock values imputed to the lower limit of the assay. (B), IFM for CD68. Shown is a representative image from a single mouse. (C), Quantitation of total macrophage numbers/high power field. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=5). **, P<0.01. (D), IFM for ciliated epithelial cells with anti-acetyl tubulin (Ac-Tub, red) with DAPI nuclear stain (blue). Shown is a representative image from a single mouse. (E), Quantitation of Ac-Tub fluorescence intensity in RSV versus mock treatment. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=5). *, P<0.05. (F), IFM staining for distribution of differentiated alveolar type (AT) makers, Surfactant protein c (SPC), Podoplanin (PDPN) and ITGB4. Shown are representative images. (G), Quantitation of numbers of positive cells in RSV-infected versus mock treatment. *, P<0.05. (H), Merged image of SPC/PDPN/ITGB4 staining in IFM. Right, high magnification panels showing indeterminant AT phenotype.

Figure 1.

Acute RSV induces epithelial phenotypic changes. Heterozygous Scgb1a1-CreERTM X RelAfl/fl in the C57BL6/J background were mock infected (both sexes) were mock or RSV infected via the i.n. route. 4 d later, mice were euthanized for Q-RT-PCR and immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM). (A), Q-RT-PCR for RSV F mRNA. Shown are fold changes in RSV mRNA with mock values imputed to the lower limit of the assay. (B), IFM for CD68. Shown is a representative image from a single mouse. (C), Quantitation of total macrophage numbers/high power field. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=5). **, P<0.01. (D), IFM for ciliated epithelial cells with anti-acetyl tubulin (Ac-Tub, red) with DAPI nuclear stain (blue). Shown is a representative image from a single mouse. (E), Quantitation of Ac-Tub fluorescence intensity in RSV versus mock treatment. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=5). *, P<0.05. (F), IFM staining for distribution of differentiated alveolar type (AT) makers, Surfactant protein c (SPC), Podoplanin (PDPN) and ITGB4. Shown are representative images. (G), Quantitation of numbers of positive cells in RSV-infected versus mock treatment. *, P<0.05. (H), Merged image of SPC/PDPN/ITGB4 staining in IFM. Right, high magnification panels showing indeterminant AT phenotype.

Figure 2.

RSV Post Viral Lung Disease (PVLD). (A), Schematic diagram of RSV-PVLD model. Three-five week old Scgb1a1-CreERTM X RelAfl/fl mice (both sexes) in the C57BL6/J background are mock treated or infected via the i.n. route. 3 days after infection, mice are randomized to receive corn oil or tamoxifen (TMX) treatments daily via i.p. until d16. At 21d-post infection the mice were euthanized for analysis. (B), Weight difference for treatment groups over time (days). Vertical arrows, timing of TMX treatment. **, P< 0.01 post-hoc. (C,D), Q-RT-PCR of total lung RNA normalized to Gadph as internal control. (C), RelA mRNA; (D), RSV. (E), Resting oxygen saturation by treatment group. Shown is 25-75% interquartile range (IQR); each symbol is an independent animal (n=5-6). *, P< 0.05. F mRNA. 25-75% IQR; each symbol is an independent animal. **, P< 0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Figure 2.

RSV Post Viral Lung Disease (PVLD). (A), Schematic diagram of RSV-PVLD model. Three-five week old Scgb1a1-CreERTM X RelAfl/fl mice (both sexes) in the C57BL6/J background are mock treated or infected via the i.n. route. 3 days after infection, mice are randomized to receive corn oil or tamoxifen (TMX) treatments daily via i.p. until d16. At 21d-post infection the mice were euthanized for analysis. (B), Weight difference for treatment groups over time (days). Vertical arrows, timing of TMX treatment. **, P< 0.01 post-hoc. (C,D), Q-RT-PCR of total lung RNA normalized to Gadph as internal control. (C), RelA mRNA; (D), RSV. (E), Resting oxygen saturation by treatment group. Shown is 25-75% interquartile range (IQR); each symbol is an independent animal (n=5-6). *, P< 0.05. F mRNA. 25-75% IQR; each symbol is an independent animal. **, P< 0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Figure 3.

Histological features of RSV-PVLD. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. For each treatment 4X and 20X images of representative sections are shown. (A), H&E images from mock or RSV-infected mice. Oil, vehicle-treated; TMX, tamoxifen-treated. Mag, magnification. 4X Mag, scale bar, 330 mm; 20X Mag, Scale bar, 130 mm. (B), Thickness of airway epithelium. For each small bronchiole, 11 measurements of epithelial thickness were obtained and averaged to create an overall thickness score (See Supplementary Figure S1 for more detail). Each symbol is the average of multiple fields of view from an individual animal (n=5, both sexes). **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Figure 3.

Histological features of RSV-PVLD. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. For each treatment 4X and 20X images of representative sections are shown. (A), H&E images from mock or RSV-infected mice. Oil, vehicle-treated; TMX, tamoxifen-treated. Mag, magnification. 4X Mag, scale bar, 330 mm; 20X Mag, Scale bar, 130 mm. (B), Thickness of airway epithelium. For each small bronchiole, 11 measurements of epithelial thickness were obtained and averaged to create an overall thickness score (See Supplementary Figure S1 for more detail). Each symbol is the average of multiple fields of view from an individual animal (n=5, both sexes). **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Figure 4.

Expansion of small airway and alveolar progenitor cells. (A), Q-RT-PCR for Aqp3 mRNA in total lung RNA normalized to Gadph as internal control. Shown is 25-75% IQR; each symbol is an independent animal. *, P< 0.05; **, P<0.01. (B), IFM for AQP3 in a representative image from each treatment group. At top, shown is merged image of AQP3 (green) fluorescence with DAPI nuclear stain (blue). At bottom AQP3 IFM only. Scale bar, 40 mm. (C) Quantitation of total AQP3 IFM, AU, arbitrary fluorescence units. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=5). ****, P<0.0001. (D), Q-RT-PCR for Gadph-normalized Trp63 mRNA in total lung RNA. **, P<0.001. (E), IFM for TRP63 in a representative image. At top, shown is merged image of TRP63 (red) fluorescence merged with DAPI nuclear stain (blue), 40X. At bottom TRP63 IFM only. Scale bar, 40 mm. (F), Quantitation of TRP63 in IFM in AU. ****, P<0.0001.

Figure 4.

Expansion of small airway and alveolar progenitor cells. (A), Q-RT-PCR for Aqp3 mRNA in total lung RNA normalized to Gadph as internal control. Shown is 25-75% IQR; each symbol is an independent animal. *, P< 0.05; **, P<0.01. (B), IFM for AQP3 in a representative image from each treatment group. At top, shown is merged image of AQP3 (green) fluorescence with DAPI nuclear stain (blue). At bottom AQP3 IFM only. Scale bar, 40 mm. (C) Quantitation of total AQP3 IFM, AU, arbitrary fluorescence units. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=5). ****, P<0.0001. (D), Q-RT-PCR for Gadph-normalized Trp63 mRNA in total lung RNA. **, P<0.001. (E), IFM for TRP63 in a representative image. At top, shown is merged image of TRP63 (red) fluorescence merged with DAPI nuclear stain (blue), 40X. At bottom TRP63 IFM only. Scale bar, 40 mm. (F), Quantitation of TRP63 in IFM in AU. ****, P<0.0001.

Figure 5.

scRNA sequencing analysis. (A), Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) representation of single cell RNA sequencing of epithelial and mesenchymal cell populations from total lung homogenates from Mock-infected, vehicle-treated, RSV-infected, vehicle-treated or RSV-infected TMX-treated animals harvested 21 d after infection (see Supplementary Figure S3 for complete spectrum of cell types identified). Each symbol represents single cell, colored by nearest-neighbor (leiden) clusters and identified by majority voting of cell markers and unique gene expression modifiers. Abbreviations used: AT, alveolar type; Krt, keratin; Fibro, fibroblast; Fn, fibronectin; Gob, goblet; Hif, hypoxia inducible factor; Lrg, Leucine Rich Repeat Containing G Protein-Coupled Receptor; Lyz, lysozyme; Peri, pericyte. (B), UMAP representation of cell types by treatment. Note the presence of distinct populations of aAT2 and Krt8+Club cells induced by RSV in vehicle-treated mice or by RSV with RelA CKO. (C) Cell types expressing Scgb1a1. Shown is relative expression of Scgb1a1 mRNA overlaid on the parent UMAP. Note the high Scgb1a1 expression by the Krt8+Club and Club cells. Scale is shown at right. (D), Cell types expressing Sftpc. Shown is relative expression of Sftpc mRNA overlaid on the parent UMAP. Note the high Sftpc expression by the aAT2, Lyz+AT2 and Mki67+AT2 cells. Scale is shown at right. (E), Heat map of epithelial cell populations for major epithelial cell markers. Abbreviations: Sftp, surfactant protein; Lyz, lysozyme; SDC, syndecan; Hhip, hedgehog interacting protein; Hopx, HOP homeobox, Itgb4, integrin 4; Taglin, transgelin. (F), Dotplot of most highly variable genes for each cell type assignment. Circle diameter refers to percentage of cell population; color indicates expression level of indicated gene. Note the unique AT2 cell markers surfactant (Sftp)-C and D in the AT2 population and expression of the AT1 marker, Ager mRNA in the same population; and expression of the progenitor marker Hopx in the Krt8+Club cell. (G), Cell frequency of epithelial and mesenchymal cell populations by treatment. For each cell type in each treatment, the frequency of cells normalized to total cells was calculated. Mock, mock-infected/vehicle-treated; RSV, RSV-infected/vehicle-treated; RKD, RSV-infected, RelA knockdown (RelA CKO).

Figure 5.

scRNA sequencing analysis. (A), Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) representation of single cell RNA sequencing of epithelial and mesenchymal cell populations from total lung homogenates from Mock-infected, vehicle-treated, RSV-infected, vehicle-treated or RSV-infected TMX-treated animals harvested 21 d after infection (see Supplementary Figure S3 for complete spectrum of cell types identified). Each symbol represents single cell, colored by nearest-neighbor (leiden) clusters and identified by majority voting of cell markers and unique gene expression modifiers. Abbreviations used: AT, alveolar type; Krt, keratin; Fibro, fibroblast; Fn, fibronectin; Gob, goblet; Hif, hypoxia inducible factor; Lrg, Leucine Rich Repeat Containing G Protein-Coupled Receptor; Lyz, lysozyme; Peri, pericyte. (B), UMAP representation of cell types by treatment. Note the presence of distinct populations of aAT2 and Krt8+Club cells induced by RSV in vehicle-treated mice or by RSV with RelA CKO. (C) Cell types expressing Scgb1a1. Shown is relative expression of Scgb1a1 mRNA overlaid on the parent UMAP. Note the high Scgb1a1 expression by the Krt8+Club and Club cells. Scale is shown at right. (D), Cell types expressing Sftpc. Shown is relative expression of Sftpc mRNA overlaid on the parent UMAP. Note the high Sftpc expression by the aAT2, Lyz+AT2 and Mki67+AT2 cells. Scale is shown at right. (E), Heat map of epithelial cell populations for major epithelial cell markers. Abbreviations: Sftp, surfactant protein; Lyz, lysozyme; SDC, syndecan; Hhip, hedgehog interacting protein; Hopx, HOP homeobox, Itgb4, integrin 4; Taglin, transgelin. (F), Dotplot of most highly variable genes for each cell type assignment. Circle diameter refers to percentage of cell population; color indicates expression level of indicated gene. Note the unique AT2 cell markers surfactant (Sftp)-C and D in the AT2 population and expression of the AT1 marker, Ager mRNA in the same population; and expression of the progenitor marker Hopx in the Krt8+Club cell. (G), Cell frequency of epithelial and mesenchymal cell populations by treatment. For each cell type in each treatment, the frequency of cells normalized to total cells was calculated. Mock, mock-infected/vehicle-treated; RSV, RSV-infected/vehicle-treated; RKD, RSV-infected, RelA knockdown (RelA CKO).

Figure 6.

Lineage tracing of Scgb1a progenitor cells. (A), Schematic view of lineage tracing experiment. RSV-PVLD was first induced, followed by TMX treatment 3-8 d prior to harvest at 21 d post infection. (B), GFP fluorescence in bronchiole (top) and alveoli (bottom) for Mock or RSV-infected mice. Shown is a representative image from each treatment group. (C), Quantitation of total GFP in alveoli. AU, arbitrary fluorescence units. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=4). ***, P<0.001. (D), IFM for EGFP, RSV F glycoprotein and TRP63 in Mock-infected (top) or RSV-infected mice (Bottom row). Shown is a representative image from each treatment group. (E), Quantitation of RSV F glycoprotein staining. AU, arbitrary fluorescence units. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=4). (F), Quantitation of TRP63 staining.

Figure 6.

Lineage tracing of Scgb1a progenitor cells. (A), Schematic view of lineage tracing experiment. RSV-PVLD was first induced, followed by TMX treatment 3-8 d prior to harvest at 21 d post infection. (B), GFP fluorescence in bronchiole (top) and alveoli (bottom) for Mock or RSV-infected mice. Shown is a representative image from each treatment group. (C), Quantitation of total GFP in alveoli. AU, arbitrary fluorescence units. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=4). ***, P<0.001. (D), IFM for EGFP, RSV F glycoprotein and TRP63 in Mock-infected (top) or RSV-infected mice (Bottom row). Shown is a representative image from each treatment group. (E), Quantitation of RSV F glycoprotein staining. AU, arbitrary fluorescence units. Each symbol is average of multiple images for each individual animal (n=4). (F), Quantitation of TRP63 staining.

Figure 7.

RSV-induced differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Pseudobulk analysis of DEGs in response to RSV infection. Differential gene expression in mock-infected, vehicle treated aAT2 cells (

A,B) or

Pdgfra+ Fibroblasts (

C,D) was estimated with pseudobulk methods, correcting for multiple hypothesis testing [

54]. (

A,C), Volcano plots of Log

2FC gene expression vs -Log10(pVal) for significant genes are shown. Highly up- and down-regulated genes are shown. (

A), aAT2 cells; (

C),

Pdgfra+ Fibroblasts. Selected abbreviations: Cry1, Cryptochrome Circadian Regulator 1; Cry1, Cryptochrome Circadian Regulator 1; Dbp, D-Box Binding PAR BZIP Transcription Factor; Egr1, Early Growth Response 1; Nr1d, Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 1 Group D Member; Rorc, RAR Related Orphan Receptor C. (

B,D), Genome Ontology enrichment of DEGs. Top 15 biological pathways identified for DEGs are shown. For each pathway, the fraction of genes represented in the pathway (Ratio, bars) and the adjusted False Discovery Rate (FDR, circles) are shown. (

B), aAT2 cells; (

D),

Pdgfra + Fibroblasts.

Figure 7.

RSV-induced differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Pseudobulk analysis of DEGs in response to RSV infection. Differential gene expression in mock-infected, vehicle treated aAT2 cells (

A,B) or

Pdgfra+ Fibroblasts (

C,D) was estimated with pseudobulk methods, correcting for multiple hypothesis testing [

54]. (

A,C), Volcano plots of Log

2FC gene expression vs -Log10(pVal) for significant genes are shown. Highly up- and down-regulated genes are shown. (

A), aAT2 cells; (

C),

Pdgfra+ Fibroblasts. Selected abbreviations: Cry1, Cryptochrome Circadian Regulator 1; Cry1, Cryptochrome Circadian Regulator 1; Dbp, D-Box Binding PAR BZIP Transcription Factor; Egr1, Early Growth Response 1; Nr1d, Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 1 Group D Member; Rorc, RAR Related Orphan Receptor C. (

B,D), Genome Ontology enrichment of DEGs. Top 15 biological pathways identified for DEGs are shown. For each pathway, the fraction of genes represented in the pathway (Ratio, bars) and the adjusted False Discovery Rate (FDR, circles) are shown. (

B), aAT2 cells; (

D),

Pdgfra + Fibroblasts.

Figure 8.

Dysregulation of the BMAL-Nr1d1 clock pathway. (A-D) Q-RT-PCR for BMAL-Nr1d1 pathway genes in total lung RNA normalized to Gadph as internal control. Shown is 25-75% IQR; each symbol is an independent animal. (A), Bmal mRNA, (B), Nr1d1 mRNA, (C), Nr1d2 mRNA, (D) Clock1 mRNA. *, P< 0.05; **, P<0.01. (E), IFM for NR1D1. Shown is a representative image from each treatment group. Scale bar, 90 mm. (F), Quantitation of NR1D1 expression in AU.

Figure 8.

Dysregulation of the BMAL-Nr1d1 clock pathway. (A-D) Q-RT-PCR for BMAL-Nr1d1 pathway genes in total lung RNA normalized to Gadph as internal control. Shown is 25-75% IQR; each symbol is an independent animal. (A), Bmal mRNA, (B), Nr1d1 mRNA, (C), Nr1d2 mRNA, (D) Clock1 mRNA. *, P< 0.05; **, P<0.01. (E), IFM for NR1D1. Shown is a representative image from each treatment group. Scale bar, 90 mm. (F), Quantitation of NR1D1 expression in AU.

Figure 9.

Intercellular signaling analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal niches. (A-C), 2D global cellular communication network analysis. Each dot represents the communication network of one cell group with incoming signal plotted on the x-axis and outgoing signaling plotted on the y-axis. Dot size is proportional to the overall communication probability. (A), Mock-infected WT; (B), RSV-infected WT; (C) RSV-infected RelA CKO mice. Note the increase in outgoing signals generated by the Hif1+ Peri (arrowhead). (D), Information flow in RSV vs mock-infected mice. All the significant signaling pathways identified were ranked based on their differences of overall information flow between mock and RSV infected mice. The overall information flow of a signaling network is calculated by summarizing all the communication probabilities in that network. The top signaling pathways colored by red are more enriched in mock-infected mice, and the bottom ones in cyan are enriched in RSV-infected mice. Signaling pathways are shown on the y-axis; those colored in red or cyan are significant between treatments at P<0.05 level. (E), Information flow in RSV infected vehicle mice and RSV-infected RelA CKO (RKD). (F) Heat map of incoming signaling of individual cellular communication pathways for cell types in mock-infected mice. The top colored bar plot shows the total signaling strength of a cell group by summarizing all signaling pathways displayed in the heatmap. The right grey bar plot shows the total signaling strength of a signaling pathway by summarizing all cell groups displayed in the heatmap. Note the increase in ANGPTL4 incoming signal in Lgr6+ Fib and aAT2 (arrowheads). (G), Heat map of outgoing signaling for cells in RSV-infected WT mice. Note the increase in ANGPTL4 by Hif+ Peri (arrowhead).

Figure 9.

Intercellular signaling analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal niches. (A-C), 2D global cellular communication network analysis. Each dot represents the communication network of one cell group with incoming signal plotted on the x-axis and outgoing signaling plotted on the y-axis. Dot size is proportional to the overall communication probability. (A), Mock-infected WT; (B), RSV-infected WT; (C) RSV-infected RelA CKO mice. Note the increase in outgoing signals generated by the Hif1+ Peri (arrowhead). (D), Information flow in RSV vs mock-infected mice. All the significant signaling pathways identified were ranked based on their differences of overall information flow between mock and RSV infected mice. The overall information flow of a signaling network is calculated by summarizing all the communication probabilities in that network. The top signaling pathways colored by red are more enriched in mock-infected mice, and the bottom ones in cyan are enriched in RSV-infected mice. Signaling pathways are shown on the y-axis; those colored in red or cyan are significant between treatments at P<0.05 level. (E), Information flow in RSV infected vehicle mice and RSV-infected RelA CKO (RKD). (F) Heat map of incoming signaling of individual cellular communication pathways for cell types in mock-infected mice. The top colored bar plot shows the total signaling strength of a cell group by summarizing all signaling pathways displayed in the heatmap. The right grey bar plot shows the total signaling strength of a signaling pathway by summarizing all cell groups displayed in the heatmap. Note the increase in ANGPTL4 incoming signal in Lgr6+ Fib and aAT2 (arrowheads). (G), Heat map of outgoing signaling for cells in RSV-infected WT mice. Note the increase in ANGPTL4 by Hif+ Peri (arrowhead).

Figure 10.

Mesenchymal-epithelial ANGPTL4 signaling pathway. (A), Circle plot of ANGPTL4 communication probability between cell types. Each connecting edge width represents the communication probability. Note the autocrine regulation of Angptl4 on the Hif1+Peri and Lgr6+Fib and increased communication probability with Gob cells. (B), Circle plot of ANGPTL4 communication for RSV infected WT mice. Note increased signaling by Hif+Peri and Fibroblasts. (C) Circle plot of ANGPTL4 for RSV-infected RelA CKO. (D), Angptl4 expression in cells from RSV-infected mice. UMAP representation colored by Angptl4 mRNA expression. (E), Expression of major Angptl4 receptor. Sdc1 expression overlaying UMAP representation for RSV-infected cells. Note the high Angptl4 receptor expression in aAT2 and Krt8+ Club and Club cells. (F), Systematic analysis of ANGPTL family ligands and known receptors. Violin plot showing the expression distribution of signaling genes and receptors for the ANGPTL4 pathway. For each plot, expression is shown for mock (orange) or RSV-infected mice (green). Note the upregulation of ANGPTL4 ligand expression in Hif+Peri and Fibro (arrowheads) in RSV-infected mice without changes in ANGPTL receptor expression in target epithelial cells. (G), ANGPTL4 abundance in BALF. ANGPTL4 protein was measured in BALF (n=4). **, P<0.01.

Figure 10.

Mesenchymal-epithelial ANGPTL4 signaling pathway. (A), Circle plot of ANGPTL4 communication probability between cell types. Each connecting edge width represents the communication probability. Note the autocrine regulation of Angptl4 on the Hif1+Peri and Lgr6+Fib and increased communication probability with Gob cells. (B), Circle plot of ANGPTL4 communication for RSV infected WT mice. Note increased signaling by Hif+Peri and Fibroblasts. (C) Circle plot of ANGPTL4 for RSV-infected RelA CKO. (D), Angptl4 expression in cells from RSV-infected mice. UMAP representation colored by Angptl4 mRNA expression. (E), Expression of major Angptl4 receptor. Sdc1 expression overlaying UMAP representation for RSV-infected cells. Note the high Angptl4 receptor expression in aAT2 and Krt8+ Club and Club cells. (F), Systematic analysis of ANGPTL family ligands and known receptors. Violin plot showing the expression distribution of signaling genes and receptors for the ANGPTL4 pathway. For each plot, expression is shown for mock (orange) or RSV-infected mice (green). Note the upregulation of ANGPTL4 ligand expression in Hif+Peri and Fibro (arrowheads) in RSV-infected mice without changes in ANGPTL receptor expression in target epithelial cells. (G), ANGPTL4 abundance in BALF. ANGPTL4 protein was measured in BALF (n=4). **, P<0.01.