1. Introduction

Q fever is a multispecies disease caused by

Coxiella burnetii (

C. burnetii), a gram-negative intracellular bacterium [

1]. It is a zoonotic infection in which ruminants serve as the primary source of human exposure [

2]. Although clinical signs are uncommon in ruminants, the disease can cause substantial economic losses due to reproductive disorders, including late-term abortion, stillbirth, weak offspring, and infertility [

3]. The impact of Q fever has been reported to be more severe in goats than in sheep [

4]. Both clinically and subclinically infected goats shed large quantities of the pathogen during the periparturient period through birth products, vaginal discharges, feces, urine, and milk [

4,

5]. Owing to its high sensitivity and rapid turnaround time, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is widely used as a screening tool for detecting

C. burnetii infection in ruminants [

6].

C. burnetii infection has been reported worldwide. In goats, individual seroprevalence ranges from 0.8% to 65.8%, and herd-level seroprevalence from 2.8% to 100% [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] In Thailand, individual seroprevalence of goats ranges from 3.5% to 12.8% [

15,

16], while herd-level seroprevalence ranges from 33.3% to 62.0% [

16,

17]. The pathogen has also been detected in sheep, cattle, buffaloes, and individuals with occupational exposure [

15,

16,

18,

19], although prevalence in these groups is generally lower than in goats.

Goat farming has been increasingly promoted in the central and western regions of Thailand, which together accounted for one-third of the national goat population in 2023 [

20]. Due to limited private grazing areas in these regions, some farmers allow their goats to forage on open-access lands. Such practices may facilitate disease transmission, as infected free-roaming goats pose a potential One Health risk to animals, humans, and the environment. Establishing the prevalence of infection in goats is therefore critical to guiding future control strategies. However, data from these regions remain scarce. This study aimed to determine the seroprevalence of

C. burnetii infection in goats raised in the central and western Thailand.

2. Materials and Methods

An initial sample size of 1,000 goats was calculated to provide a reliable estimate of individual seroprevalence, based on an expected prevalence of 12.8% [

16] and a 95% confidence level. This sample size was sufficient to achieve a margin of error of less than 3%. Sample sizes for each province in central and western Thailand were allocated proportionally according to the number of registered goat farms. Serum samples were first randomly selected from two laboratories under the Department of Livestock Development (DLD), Thailand, with a maximum of fourteen samples per farm. These samples had been collected between 2021 and 2023. Additional blood sampling was conducted in 2023 in the provinces where the number of available samples from DLD laboratories did not meet the target sample size.

A commercial ELISA kit (ID Screen® Q Fever Indirect Multi-species, IDvet™, Grabels, France) was used to detect C. burnetii–specific antibodies in serum samples. A herd was classified as positive if at least one sample tested positive.

Individual- and herd-level seroprevalence were calculated. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare infection proportions between the central and western regions and between meat and dairy goats. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 947 goat serum samples from 101 herds in nine central and six western provinces of Thailand were included in the study (

Table 1). Most samples (760 from 83 herds) were obtained from two DLD laboratories, while the remaining 187 samples (18 herds) were collected through additional field sampling. Although the total number of samples was slightly lower than the initially calculated sample size, it remained sufficient to produce estimates with a margin of error of less than 3%.

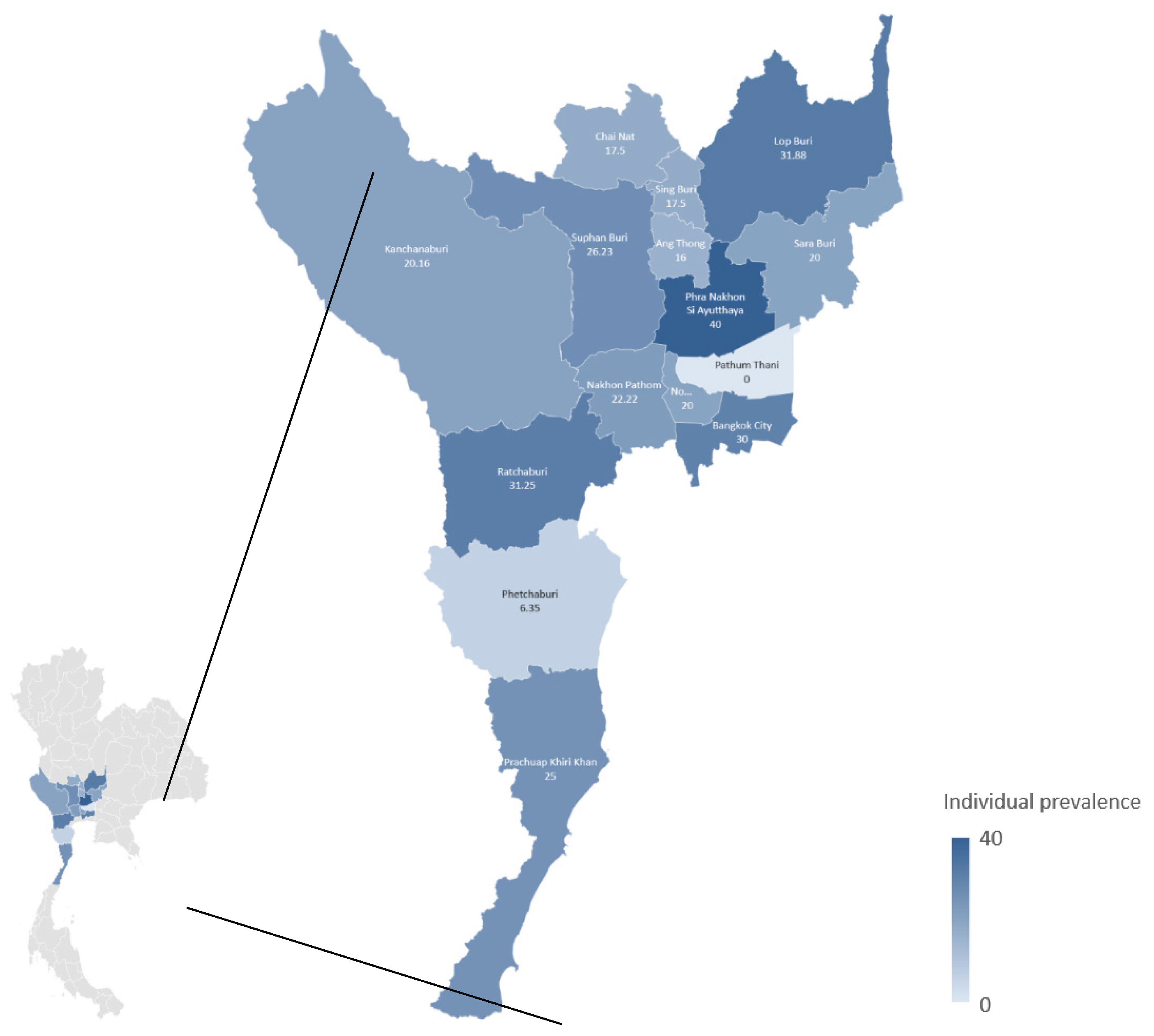

The overall individual- and herd-level seroprevalence rates of

C. burnetii infection were 22.39% (95% CI: 19.84–25.16%) and 58.42% (95% CI: 48.43–67.75%), respectively. Twenty-five samples (2.64%) produced suspect results. Within-herd individual seroprevalence ranged from 0% to 100%, with a mean of 22.22%. At the provincial level, the highest individual seroprevalence (40%) was observed in Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, while the highest herd-level seroprevalence (100%) occurred in both Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya and Nonthaburi. Pathum Thani, represented by five samples from a single herd, was the only province with no positive samples (

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

Pearson’s chi-square test showed that both individual- and herd-level seroprevalence rates were significantly higher in the central region compared with the western region

(p = 0.044 and 0.007, respectively). Although dairy goats exhibited slightly higher individual- and herd-level seroprevalence than meat goats (

Table 2), these differences were not statistically significant (

p = 0.586 and 0.855, respectively).

4. Discussion

Since Q fever vaccines for ruminants have never been used in Thailand, the positive results in this study indicate natural exposure to

C. burnetii. The individual seroprevalence of 22.39% observed here is notably higher than the previously reported range of 3.5–12.8% in Thai goats [

15,

16]. However, the herd-level seroprevalence of 58.42% is comparable to the 62.00% reported in a recent study [

16]. Compared with data from 2013–2015, our study revealed higher individual and herd-level seroprevalence in the same locations—Kanchanaburi (20.61% and 69.23% vs. 15.66% and 63.16%) and Nakhon Pathom (22.22% and 60.00% vs. 12.10% and 54.54%) [

16]. Goat farming promotion programs implemented by various organizations have contributed to a 2.6-fold increase in the goat population in these provinces between 2015 and 2023 [

20], which may have facilitated pathogen transmission. Additionally, the ELISA technique used in this study is more sensitive than the immunofluorescent assay used previously [

6], which may also account for higher detection rates.

The mean individual seroprevalence within infected herds (37.79%) was lower than the 46.6% reported in dairy goat herds in the Netherlands during the major Q fever outbreaks in humans and animals from 2007 to 2009 [

8]. However, as noted by Rousset et al. [

5], some goats infected with

C. burnetii may not produce detectable antibodies, indicating the potential for underestimation. Incorporating antigen detection methods could help identify infected animals that test negative on serological assays and detect key transmitters within herds.

Differences in herd management practices between the central and western regions may explain the observed regional differences in seroprevalence. A previous study involving dairy cattle in two western provinces reported an individual seroprevalence of 7.33%, which was lower than in other regions, although the central region was not included in that study [

21]. Most of the provinces with the highest individual prevalence—Lopburi, Ratchaburi, Bangkok, and Suphan Buri—had large dairy goat populations [

20]. However, Pearson’s chi-square test revealed no significant differences between meat and dairy goats at either the individual or herd level. The influence of goat type on infection risk remains unclear. While some studies have reported higher prevalence in dairy ruminants compared with meat-producing ruminants [

16,

22], Jesse et al. [

14] found the opposite pattern, with higher seroprevalence in meat goats than in dairy goats.

Several risk factors for

C. burnetii infection have been identified in previous studies, including increasing animal age, large herd size, contact with animals from other herds, co-rearing of sheep and goats, presence of ticks, and inadequate sanitation of feeding equipment [

9,

11,

14,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Conversely, the use of kidding pens, replacement of bedding following abortions, and isolation of animals that have aborted have been reported as protective practices [

26]. Prevalence has also been shown to vary by breed and geographic location [

11,

14,

22,

23,

27]. However, limited background information from the samples obtained through DLD laboratories restricted the ability to assess risk or protective factors in this study. Further investigations are needed to identify such factors and support tailored disease-control strategies. Enhanced surveillance in other animal species and humans in affected areas is also recommended to better understand the epidemiological dynamics of Q fever.

5. Conclusions

This study identified a considerable prevalence of C. burnetii infection among goats in the central and western Thailand. These findings underscore the need for effective surveillance and control measures to limit pathogen transmission among animals. Additionally, increasing awareness among at-risk individuals regarding personal protective measures is critically important.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R., T.R..; methodology, N.R., P.L., S.J.; software, N.R..; validation, N.R., P.L., D.P..; formal analysis, N.R.; investigation, N.R.; resources, D.P., K.V.; data curation, N.R., K.V.; writing—original draft preparation, N.R.; writing—review and editing, N.R., T.R.; visualization, N.R.; supervision, T.R.; project administration, N.R.; funding acquisition, N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), under Grant No. N24A660245.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use for Scientific Research Committee, Kasetsart University, Thailand (ACKU66-VET-042).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No publicly archived datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to the goat farmers, Department of Livestock Development officers, and Ms. Phitcha Pongphitcha and Mr. Poothana Sae-Foo for their invaluable assistance in sample collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- van den Brom, R.; van Engelen, E.; Roest, H.I.J.; van der Hoek, W.; Vellema, P. Coxiella burnetii infections in sheep or goats: An opinionated review. Veter- Microbiol. 2015, 181, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groten, T.; Kuenzer, K.; Moog, U.; Hermann, B.; Maier, K.; Boden, K. Who is at risk of occupational Q fever: new insights from a multi-profession cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e030088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, J.K.K.; Jin, Z.; Sun, G.-Q.; Li, M.Y. A Deterministic Model for Q Fever Transmission Dynamics within Dairy Cattle Herds: Using Sensitivity Analysis and Optimal Controls. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2020, 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibach, R.; Bothe, F.; Runge, M.; Fischer, S.F.; Philipp, W.; Ganter, M. Q fever: baseline monitoring of a sheep and a goat flock associated with human infections. Epidemiology Infect. 2012, 140, 1939–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, E.; Berri, M.; Durand, B.; Dufour, P.; Prigent, M.; Delcroix, T.; Touratier, A.; Rodolakis, A. Coxiella burnetii Shedding Routes and Antibody Response after Outbreaks of Q Fever-Induced Abortion in Dairy Goat Herds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousset, E.; Durand, B.; Berri, M.; Dufour, P.; Prigent, M.; Russo, P.; Delcroix, T.; Touratier, A.; Rodolakis, A.; Aubert, M. Comparative diagnostic potential of three serological tests for abortive Q fever in goat herds. Veter- Microbiol. 2007, 124, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili, M.; Sakhaee, E. An Update on a Serologic Survey of Q Fever in Domestic Animals in Iran. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 80, 1031–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmer, B.; Luttikholt, S.; LA Hautvast, J.; Graat, E.A.; Vellema, P.; van Duynhoven, Y.T. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Q fever in goats on commercial dairy goat farms in the Netherlands, 2009-2010. BMC Veter- Res. 2011, 7, 81–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezatkhah, M.; Alimolaei, M.; Khalili, M.; Sharifi, H. Seroepidemiological study of Q fever in small ruminants from Southeast Iran. J. Infect. Public Heal. 2015, 8, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambton, S.L.; Smith, R.P.; Gillard, K.; Horigan, M.; Farren, C.; Pritchard, G.C. Serological survey using ELISA to determine the prevalence ofCoxiella burnetiiinfection (Q fever) in sheep and goats in Great Britain. Epidemiology Infect. 2015, 144, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, F.; Vitale, N.; Ballardini, M.; Borromeo, V.; Luzzago, C.; Chiavacci, L.; Mandola, M.L. Q fever seroprevalence and risk factors in sheep and goats in northwest Italy. Prev. Veter- Med. 2016, 130, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemmer, J.; Njeru, J.; Emam, A.; El-Sayed, A.; A Moawad, A.; Henning, K.; A Elbeskawy, M.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Straubinger, R.K.; Neubauer, H.; et al. Q fever in Egypt: Epidemiological survey of Coxiella burnetii specific antibodies in cattle, buffaloes, sheep, goats and camels. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0192188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Luo, H.; Shahzad, M. Epidemiology of Q-fever in goats in Hubei province of China. Trop. Anim. Heal. Prod. 2018, 50, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesse, F.F.A.; Paul, B.T.; Hashi, H.A.; Chung, E.L.T.; Abdurrahim, N.A.; Lila, M.A.M. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Q fever in small ruminant flocks in selected States of Peninsular Malaysia. Thai J. Veter- Med. 2020, 50, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doung-Ngern, P.; Chuxnum, T.; Pangjai, D.; Opaschaitat, P.; Kittiwan, N.; Rodtian, P.; Buameetoop, N.; Kersh, G.J.; Padungtod, P. Seroprevalence of Coxiella burnetii Antibodies Among Ruminants and Occupationally Exposed People in Thailand, 2012–2013. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangjai, D.; Wangroongsarb, P.; Boonmar, S.; Rukkwamsuk, T. Seropositivity rate of Coxiella burnetii infection in cattle and goats raised in the upper north and central regions of Thailand during 2013 – 2015. J. Kasetsart Vet., 2021, 31, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Colombe, S.; Watanapalachaigool, E.; Ekgatat, M.; Ko, A.I.; Hinjoy, S. Cross-sectional study of brucellosis and Q fever in Thailand among livestock in two districts at the Thai-Cambodian border, Sa Kaeo province. One Heal. 2018, 6, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, Y.; Usaki, N.; Thongchai, C.; Kramomtong, I.; Kriengsak, P.; Tamura, Y. Seroepidemiologic survey in Thailand of Coxiella burnetii infection in cattle and chickens and presence in ticks attached to dairy cattle. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2014, 45, 1167–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Kidsin, K.; Panjai, D.; Boonmar, S. The first report of seroprevalence of Q fever in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in Phatthalung, Thailand. Veter- World 2021, 14, 2574–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DLD (Department of Livestock Development. 2024. National Livestock Farmers Data 2024. https://ict.dld.go.th/webnew/index.php/th/service-ict/report/428-report-thailand-livestock/reportservey2567/1813-2567-monthly (access on 6 December5, 2024).

- Bumrungkit, K. 2013. Prevalence and risk factors of Q fever infection in dairy cows in 5 provinces of Thailand. Thesis (MS). Kasetsart University.

- Villari, S.; Galluzzo, P.; Arnone, M.; Alfano, M.; Geraci, F.; Chiarenza, G. Seroprevalence of Coxiella burnetii infection (Q fever) in sheep farms located in Sicily (Southern Italy) and related risk factors. Small Rumin. Res. 2018, 164, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, J.; Khalili, M.; Kafi, M.; Ansari-Lari, M.; Hosseini, S.M. Risk factors of Q fever in sheep and goat flocks with history of abortion. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 23, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaidat, M.M.; Kersh, G.J. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Coxiella burnetii Antibodies in Bulk Milk from Cattle, Sheep, and Goats in Jordan. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljafar, A.; Salem, M.; Housawi, F.; Zaghawa, A.; Hegazy, Y. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Q-fever (C. burnetii infection) among ruminants reared in the eastern region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Trop. Anim. Heal. Prod. 2020, 52, 2631–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsohaby, I.; Elmoslemany, A.; El-Sharnouby, M.; Alkafafy, M.; Alorabi, M.; El-Deeb, W.M.; Al-Marri, T.; Qasim, I.; Alaql, F.A.; Fayez, M. Flock Management Risk Factors Associated with Q Fever Infection in Sheep in Saudi Arabia. Animals 2021, 11, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siengsanan-Lamont, J.; Kong, L.; Heng, T.; Khoeun, S.; Tum, S.; Selleck, P.W.; Gleeson, L.J.; Blacksell, S.D. Risk mapping using serologic surveillance for selected One Health and transboundary diseases in Cambodian goats. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).