1. Introduction

Fine aggregate affects the technical and economic performance of concrete. With the rapid depletion of natural pit sand resources in recent decades, in the construction industry, fine crushed stone aggregates are increasingly used instead of sand.

Debris from minerals and rocks mainly form due to rock weathering. A number of classification schemes, which are being improved and harmonized, have been developed. Sediments in monodisperse rock are carefully sorted, resulting in the predomination of one granulometric fraction. In bidisperse rock, the bulk of particles accumulates in two granulometric fractions. Sand particles differ in their origin, size, chemical and mineral composition, and shape. According to its grain shape, sand can be composed of predominantly round, partially round, and angled particles. The size of the particles and their other most characteristic features – shape, roundness degree, and surface roughness – are mostly determined by the physical decomposition of the rocks and the distribution of the debris material formed (transfer, deposition). The shape of grains is defined by the ratio of their axes. Zingg [

1] distinguished four main classes of grain shapes according to axial length ratios based on the triaxial ellipsoid: spherical (isometric round), disc, plate, and rod-shaped grains. The initial shape of mineral debris changes due to the smoothing of corners and edges.

Grain sphericity is the ratio of the surface areas of a sphere and a grain at equal volume [

2]. Sphericity is defined by the sphericity coefficient Ks – the degree of similarity of the shape of a grain to a sphere. The sphericity of a spherical grain is equal to 1; the less its shape resembles a sphere, the lower its sphericity value. Sphericity depends on the primary shape of the particles. It is determined by formulas or by visual comparison of a sample grain with the benchmarks. Sphericity and roundness typically increase evenly – as one parameter increases, the other increases as well and depends on the size of the particles. The surface characteristics of grains in fine aggregate are usually determined microscopically. Various names are used to describe the surface of particles, usually expressing the number of pits or roughness level, as well as assessing their depth, width, and the nature of various formations.

Particle shape is usually determined in a narrow range of one granulometric fraction. As the particles become larger, their degree of smoothing increases, therefore the particles of larger fractions generally have a higher degree of smoothing than those of smaller ones.

The methods for determining the size, shape, and surface nature of rock particles can be divided into several groups: methods for comparing grains with the benchmark; visual methods; geometric methods; and indirect methods.

The general benchmark for determining sphericity and roundness is easy to use. The advantage of all these methods is the possibility to quickly determine the morphometric parameters of grains, however, their disadvantage is the subjectivity of determination. Sand grain surface morphometry research methods have been used for a long time. The previously limited capabilities of the optical microscopic technique allowed only the general detection of grain surface roughness, angularity, or rounding. Researchers were only able to examine and describe the peculiarities of the grain surface structure can be seen by magnifying the grain ~ 100 times, whereas the consequences of chemical reactions can be seen by magnifying > 2000 times [

3].

Two-dimensional or three-dimensional research methods are used to evaluate sand particle morphometry. Some parameters are calculated based on two-dimensional (planar) parameters determined from the grain projection plane. Image analysis and visual comparison methods are commonly used to evaluate the shape characteristics of granular materials. Particle shape can be described in three different ways: by shape and sphericity (general shape), by roundness (angle sharpness), and by roughness (surface texture).

Diagrams can facilitate the evaluation of particle roundness and sphericity using regular visual aids [

4]. Particles were classified by Zingg using elongation (IL) and flatness (SL) ratios [

1]. Krumbein provided a diagram comparing roundness [

5]. Powers [

6] proposed a roundness scale to visually compare and manually set the values of roundness and sphericity. In addition, Krumbein and Sloss proposed a diagram of the combinations of sphericity and roundness of particles to evaluate the shape thereof [

7]. Cho et al. [

8] modified this diagram by defining the particle shape as the arithmetic mean of roundness and sphericity and adding a dotted line to the proposed shape. Scientists proposed a diagram to evaluate the visual two-dimensional (2D) particle angularity. The results of the DIA and lCT analysis of the length/thickness aspect ratio (L/T ratio) as a shape parameter showed that, over almost the entire size range of the fillers, the grains have remarkably similar shape characteristics [

9]. Blott and Pye combined the studies of Zingg and provided several graphs describing particle shape [

10]. A camera was used according to the DIP technology to graphically visualize particles, followed by graphics-processing software to analyze and calculate particle shape parameters [

11].

The shape and surface of the aggregate are important factors in determining the amount of water in a concrete mix [

12,

13]. Quartz sand is commonly used for fine-grained concrete. In this case, the consistency of the mixtures is good [

14,

15]. For the production of thin-walled products, it is difficult to apply concrete compaction agents. Therefore, an important requirement for dispersion-reinforced fine-grained finishing concrete mixes is the dispersion, compaction and segregation resistance of the mix. Particle angularity can increase the compressive and bending strength of concrete [

16], and improve adhesion between coarse particles and cement paste, which is useful in improving strength, especially bending force. Studies have shown that a fiberglass content of 1.2% has the best effect on concrete mix mobility, and reaches around 70 mm [

17]. Natural sand differs from most crushed aggregates (manufactured sand) in its type, particle shape and surface texture [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. In crushed aggregates, the surfaces are more angular. In this case (decreasing values of slump and slump flow), more water is required for concrete production [

9,

23]. Replacing 100% natural sand with manufactured sand increases water demand [

24]. Manufactured sand (MS) has a higher roundness and length-area ratio, and the ranges of distribution of roundness and length-area ratio in MS are larger than in river sand [

20]. In the case of self-compacting concrete, mobility, and workability are easily compromised by the phenomenon of segregation and gravity [

25]. The decrease in concrete workability is affected by the type, amount, and geometry of the used fiberglass, as well as the initial composition of the mix [

26,

27,

28]. In addition to the factors above, concrete workability is also affected by the length of the used fiberglass, the length-to-diameter ratio (l / d), and shape configuration [

29]. It has been observed that fiberglass of different amounts and different lengths has different effects on mobility [

30]. Study results have shown that the optimum fiberglass content to achieve workability, stability, and appropriate mechanical properties is about 1% for 12 mm and 4% for 6 mm of fiberglass length [

31]. It can also be seen that the addition of short fibers (3 mm, 6 mm) resulted in a higher slump than the addition of long fibers (12 mm, 20 mm). The reason for this may be that the long fibers may have been unevenly distributed in the concrete matrix, which may have reduced the slump of the concrete [

30]. Insertion of fiberglass increases the viscosity of concrete, thus reducing its fluidity [

32,

33]. The poor fibre dispersion significantly reduces the workability and stability of the matrix [

34]. Scientists have proposed a model that has proven to be an effective tool for designing fiber-reinforced concrete mixes with selected fresh-state properties using different fiber ratios and types. But they suggest that the model should be further refined in the future to take account of different aggregates [

35]. However, there are not enough papers on the effect of different aggregates on the workability and segregation of concrete mixes.

Since there is currently very little material on the effect of aggregate quantity on the technological properties of fiberglass reinforced concrete, this work analyses the effect of different aggregates (natural sand and granite siftings) on the workability (spread and slump) of the concrete mix by replacing part of the quartz sand replacing part of the quartz sand with natural sand and granite stiftings. In this case, it is important to examine particle shape in a consistent manner, and to identify the key index affecting segregation. The research also has another goal, which is to investigate whether granite stiftings, which are waste from crushing granite rocks, are suitable for use in the production of fine-grained glass fiber reinforced thin-layer concrete and to what percentage these aggregates can replace part of the quartz sand, and whether natural sand is suitable for replacement.

2. Materials and Methods

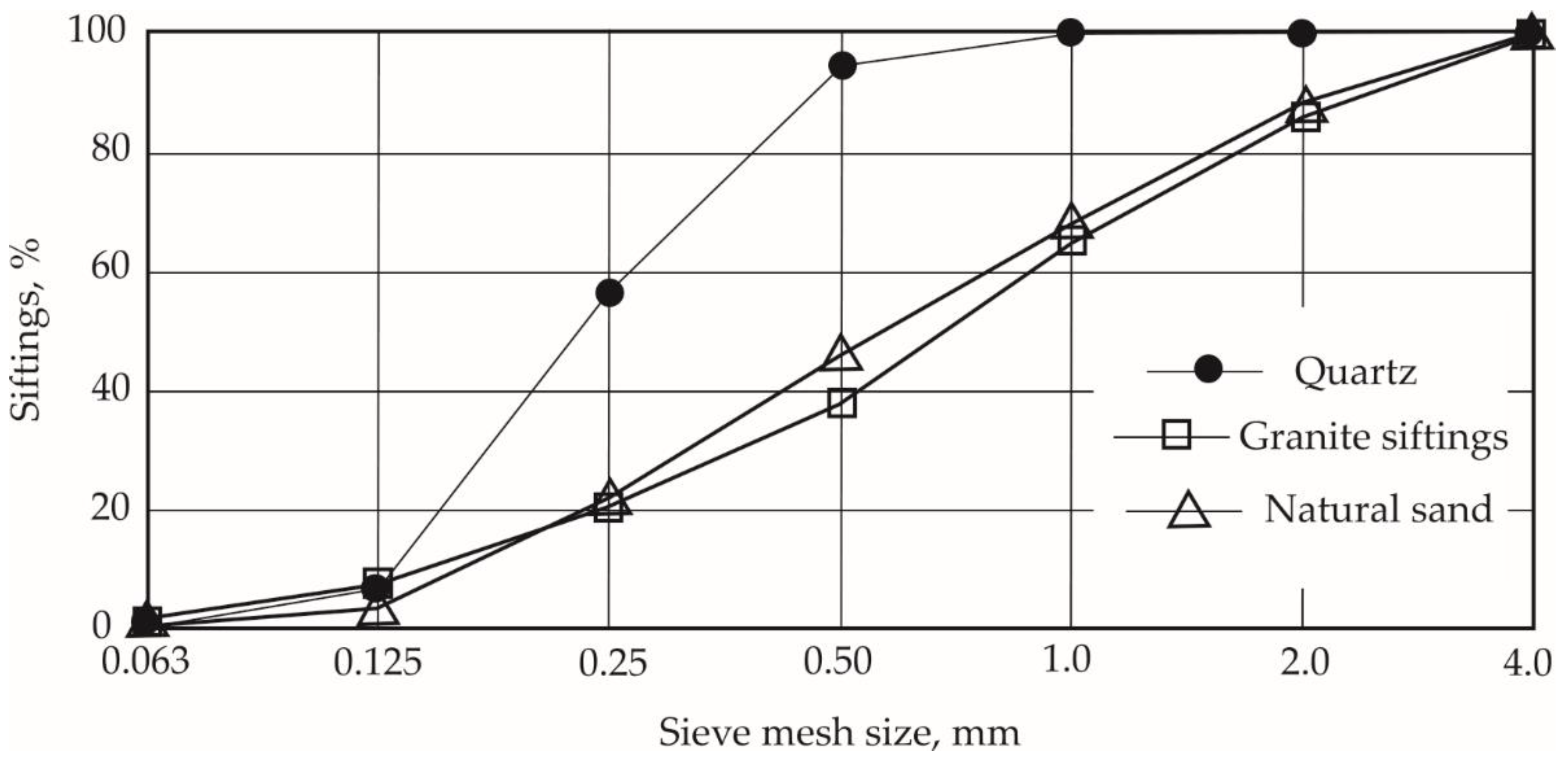

Three types of fine aggregates were used for the study. Quartz sand was used - a common aggregate when mixing mixtures intended for dispersion-reinforced fine-grained finishing concrete. A certain part of the quartz sand in some mixtures was replaced with crushed granite siftings, and in other mixtures with natural sand. The main physical and chemical properties of the fine aggregates are presented in

Table 1, and the granulometric composition is presented in

Figure 1. In the production of thin-layer panels for facades, quartz sand is used, the usual particle size of which is 0-1 mm. This is a fairly expensive resource, therefore, research was conducted to replace this resource with conventional, but less expensive materials that have potential. The research used crushed granite siftings (particle size 0–2 mm) and natural construction sand, which is supplied from a quarry with a usual particle size of 0–2 mm.

Portand cement CEM I 52.5R was used in the work. The main properties and mineralogical composition of cement as required by the standard LST EN 197-1: 2011 are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

In the production of concrete mixtures, 853 kg of cement was used per 1 m

3 of the mixture. The total amount of fine aggregate in the mixtures, per 1 m

3 of the mixture, was 853 kg. The amount of quartz sand in the mixtures varied from 50% to 100%. Quartz sand was replaced with granite siftings in GS mixtures, and with natural sand in NS mixtures. The amount of granite siftings and natural sand in GS and NS mixtures was 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%. Mixtures with granite siftings were marked GS10, GS20, GS30, GS40, GS50. Mixtures with natural sand were marked NS10, NS20, NS30, NS40, NS50. Mixture with quartz sand were marked QS. Superplasticizers were added from 1.1% of the cement mass, the W/C (water:cement) ratio was 0.36, and glass fiber was 2.9% of the dry matter content (

Table 4). A high-performance plasticizer was used to plasticize the ester-based polycarboxylates of the cement matrix, which has high efficiency and is widely used in practice.

After a series of experimental mixes and based on the recommendations in the literature, an optimal mix preparation mode was selected. Water, superplasticiser, and aggregate are added first and the mix is stirred slowly for 20–30 seconds to completely wet the aggregate particles. The binder is then dosed, and the mix is stirred for 2 mins at a maximum mixer speed of 1000 rpm until a steady consistency is reached. Fiberglass is then added and stirred for 1 min at half the maximum speed of the mixer – 500 rpm. It should be noted that this mode is suitable for mixes with fiberglass, where the fibers of the fiberglass are evenly distributed throughout the volume of the mixes and do not break down into individual fibers. The high amount of fines in the mix makes conventional normal concrete mixing techniques inadequate, as there is not enough energy to mix the large amount of fines and obtain the required mix consistency [

36]. For these fine-grained mixtures, the intensive mixing method is the exclusive method of mixing, where the concrete mixer has a single high-speed (up to 1500 rpm) rotating axis with a spiral nozzle.

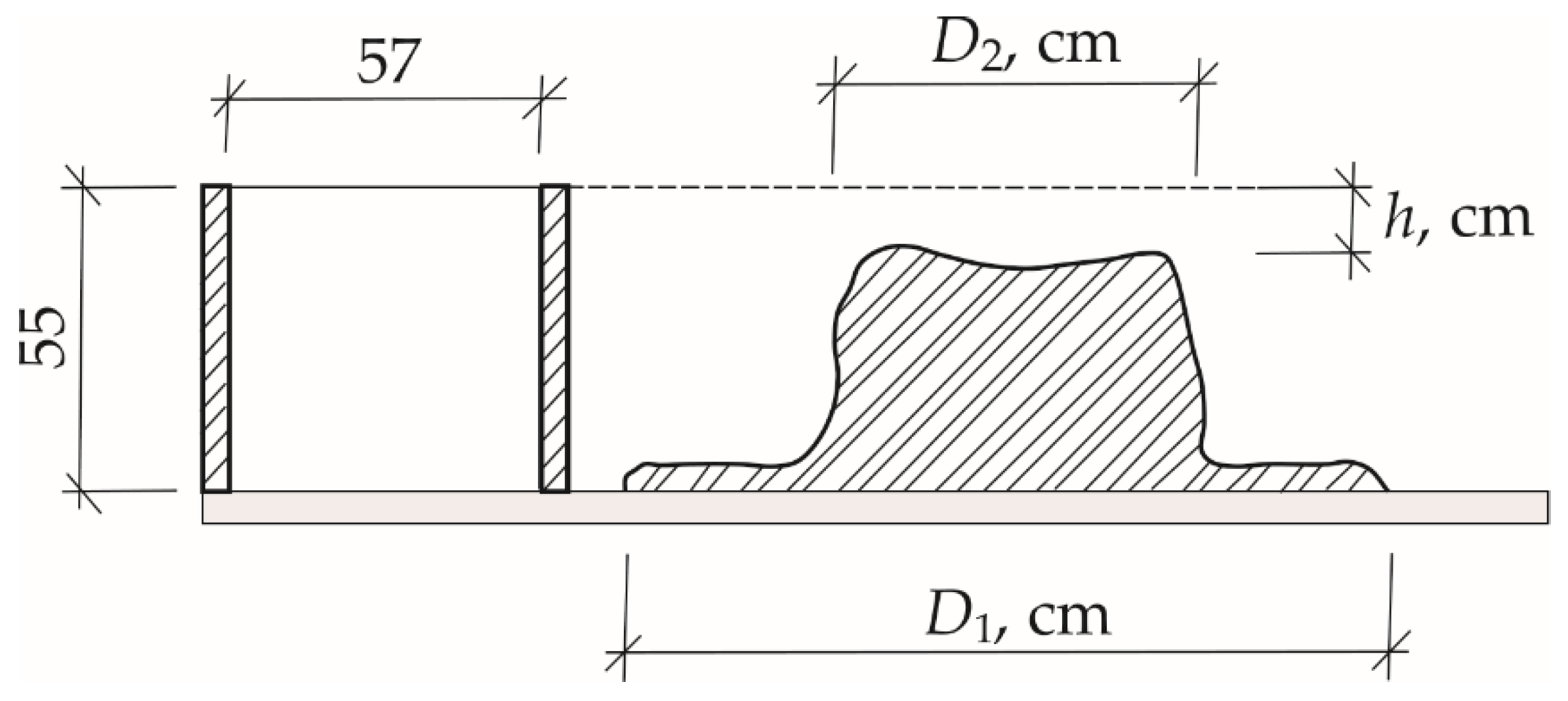

The cylindrical spread method was suitable for fine-grained cementitious composites with fibers up to 20 mm in length and was chosen to study the workability of concrete mixes. A ø 57 (h = 55 mm metal cylinder is used for the test, which is placed on a smooth surface (glass or marine plywood) and a concrete mix is poured into it. After 15–20 s the cylinder is removed, the mix is allowed to spread, and after 10–15 s the diameter (cm) of the spread mix is measured (LST EN 1170-1).

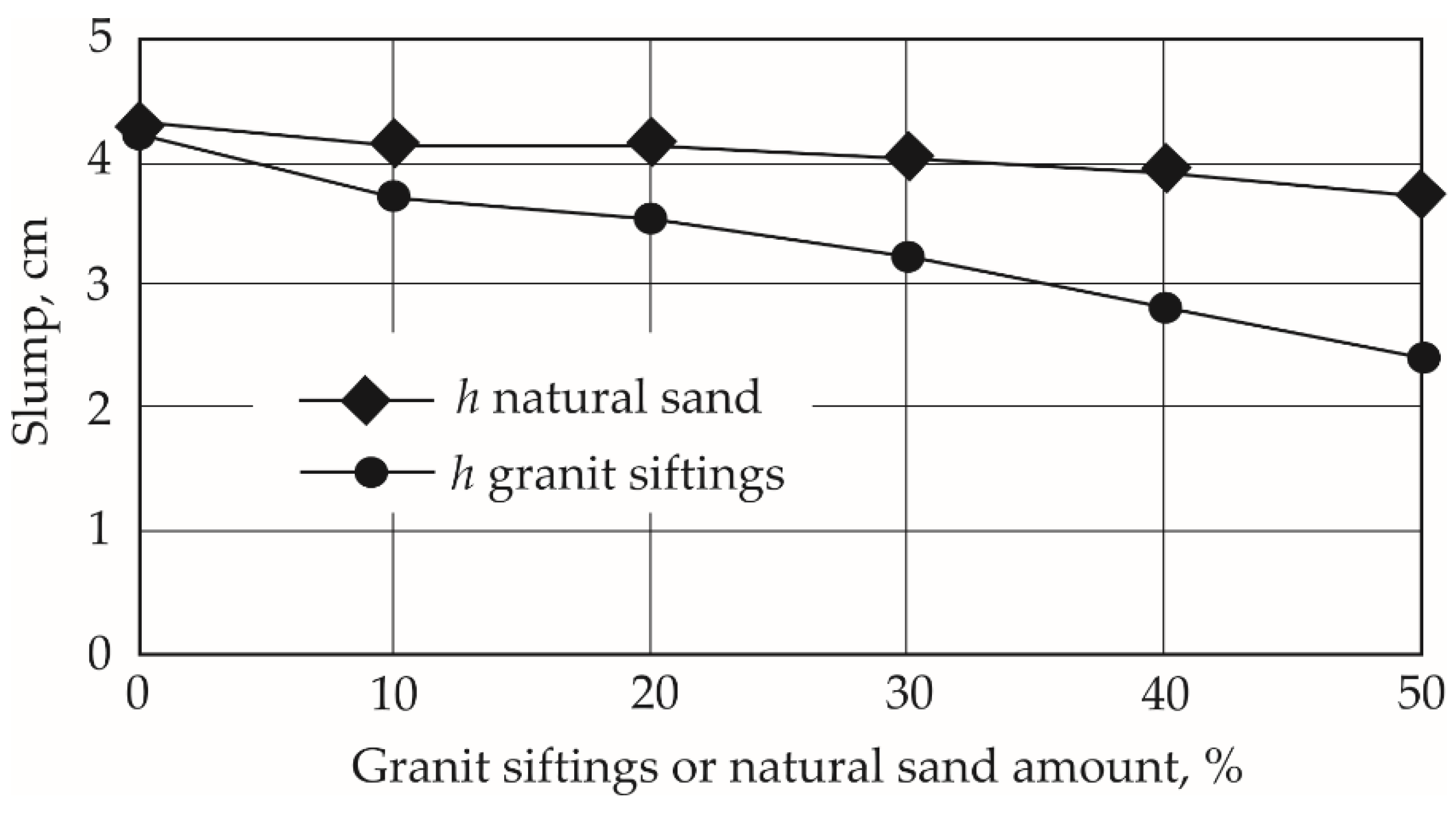

Based on the diagram in

Figure 2, we can create a parameter defining mix workability – the segregation index

W, which is directly proportional to

D1 and

D2, but inversely proportional to

h, and is expressed according to the following formula (dimensionless size):

where:

D1 – cementitious mix spread calculated as the average of two measurements made in the perpendicular direction, cm;

D2 – spread of fiber-reinforced cementitious matrix calculated as the average of two measurements made in the perpendicular direction, cm;

h – mix slump (Suttard’s viscometer height), cm.

In order to better understand the effect of aggregate particle shape on thin-layer GRC concrete mix workability, the average particle shape parameter – elongation index

I was calculated:

where:

d1 – longer side of the aggregate particle, mm;

d2 – shorter side of the aggregate particle, mm.

To determine particle shape, all three fine aggregates were separated into fractions by sieving through standard sieves: 2…4 mm, 1…2 mm, 0.5…1 mm, 0.25…0.5 mm, 0.125…0.25 mm, 0.063…0.125 mm, and microscopic photographs of each fraction were taken. An optical microscope MIN10 was used, which can magnify the image up to 104 times, and illumination from above was used. After loading the images into Autocad, elongation index (I) were determined with the help of measuring tools by selecting 30 particles from each fraction and calculating the average. Since the elongation index I is calculated as the ratio of the dimensions of particles in the perpendicular direction, the scale of images in the Autocad model space does not affect it.

When calculating particle shape and surface roughness index J, another parameter is introduced – surface roughness (

R). This can be seen from the value given for the filler shape (elongation) (

I) and surface roughness (

R) parameters of the filling particles:

where:

I – aggregate particle elongation index;

R – aggregate particle surface roughness.

3. Result and Discussion

Subsection quartz sand is the most studied and most commonly used aggregate in fine-grained concrete systems. This choice is based on the particularly good mix workability using this aggregate [

14,

37], other materials such as silica flour, silica fume, etc. can also be used [

38]. Fibres tend to tangle and form clusters in the centre of the flow [

34]. Expensive quartz sand normally used in glass fiber concrete can be replaced with more economic locally available natural sand [

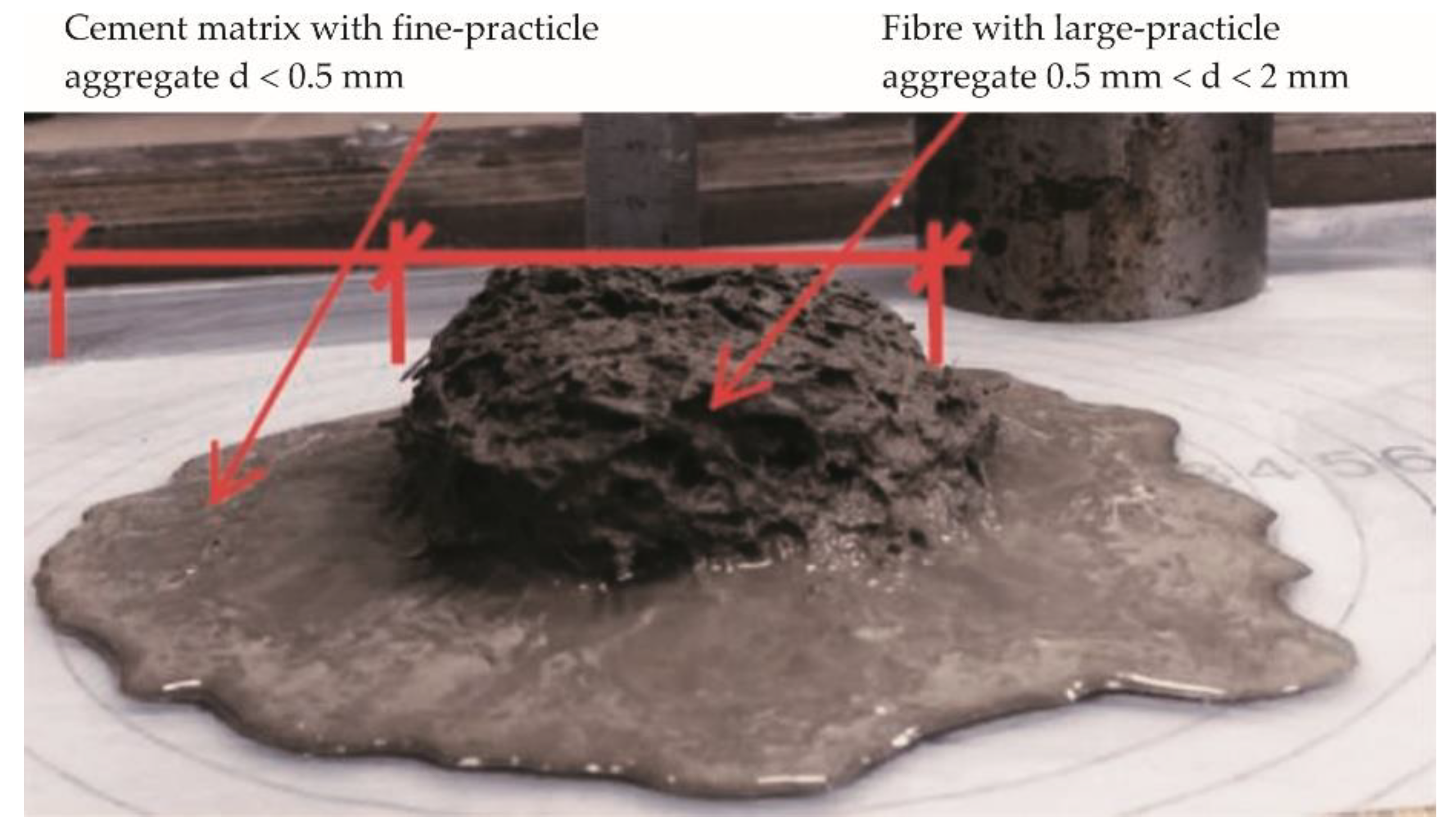

39]. Since fluid concrete mixes are studied in this work, the ability of the mix to spread quickly and evenly, and to fill the formwork of the formed product is especially important. In the production of thin-walled products, it is difficult to apply concrete compaction measures. Therefore, an important requirement for dispersively reinforced fine-grained finish concrete mixes is mix spread, slump, and resistance to segregation. In this case, mixture segregation is defined in the scientific literature as the separation of the fiber and cement matrix, as shown in

Figure 3.

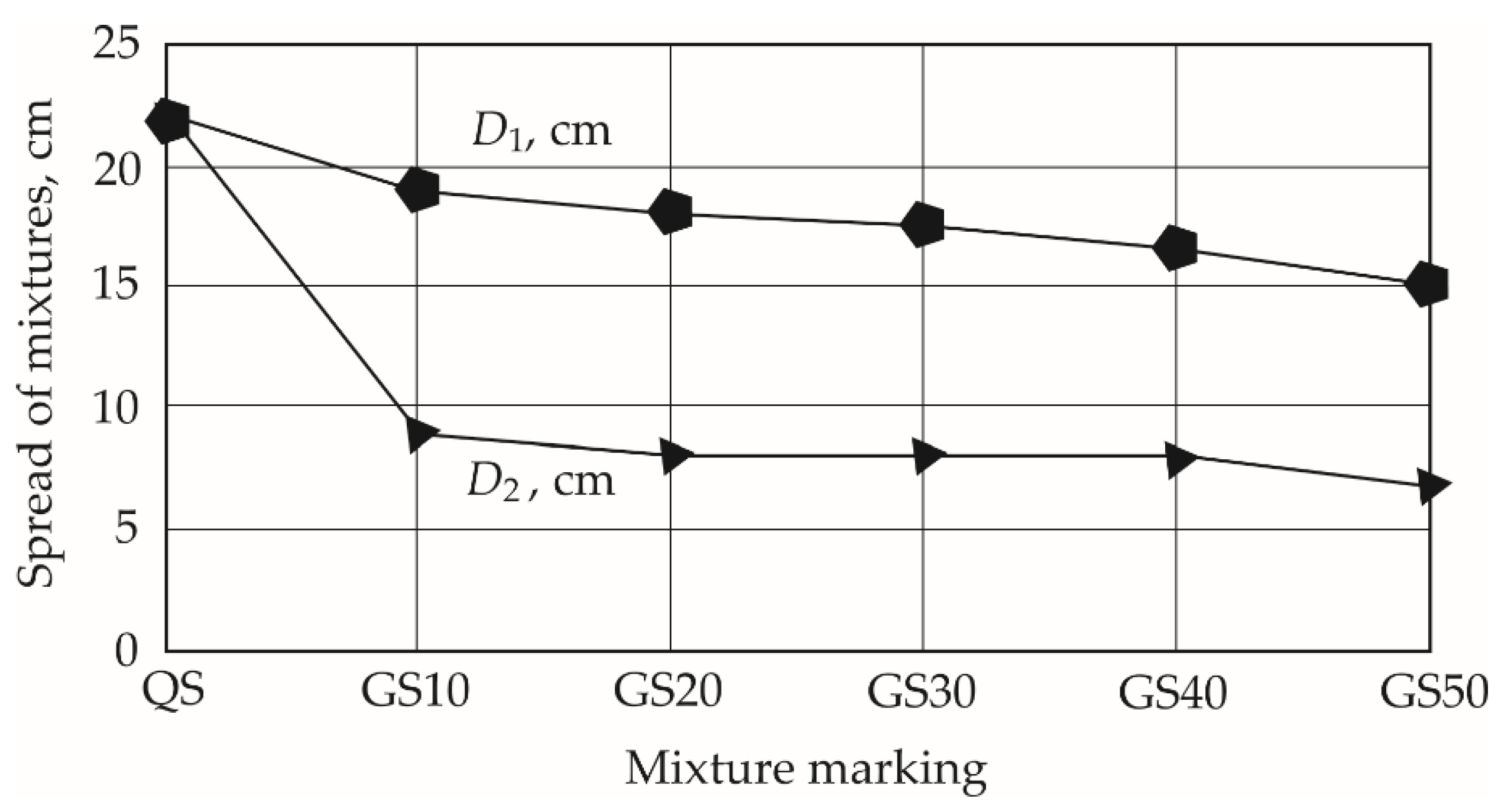

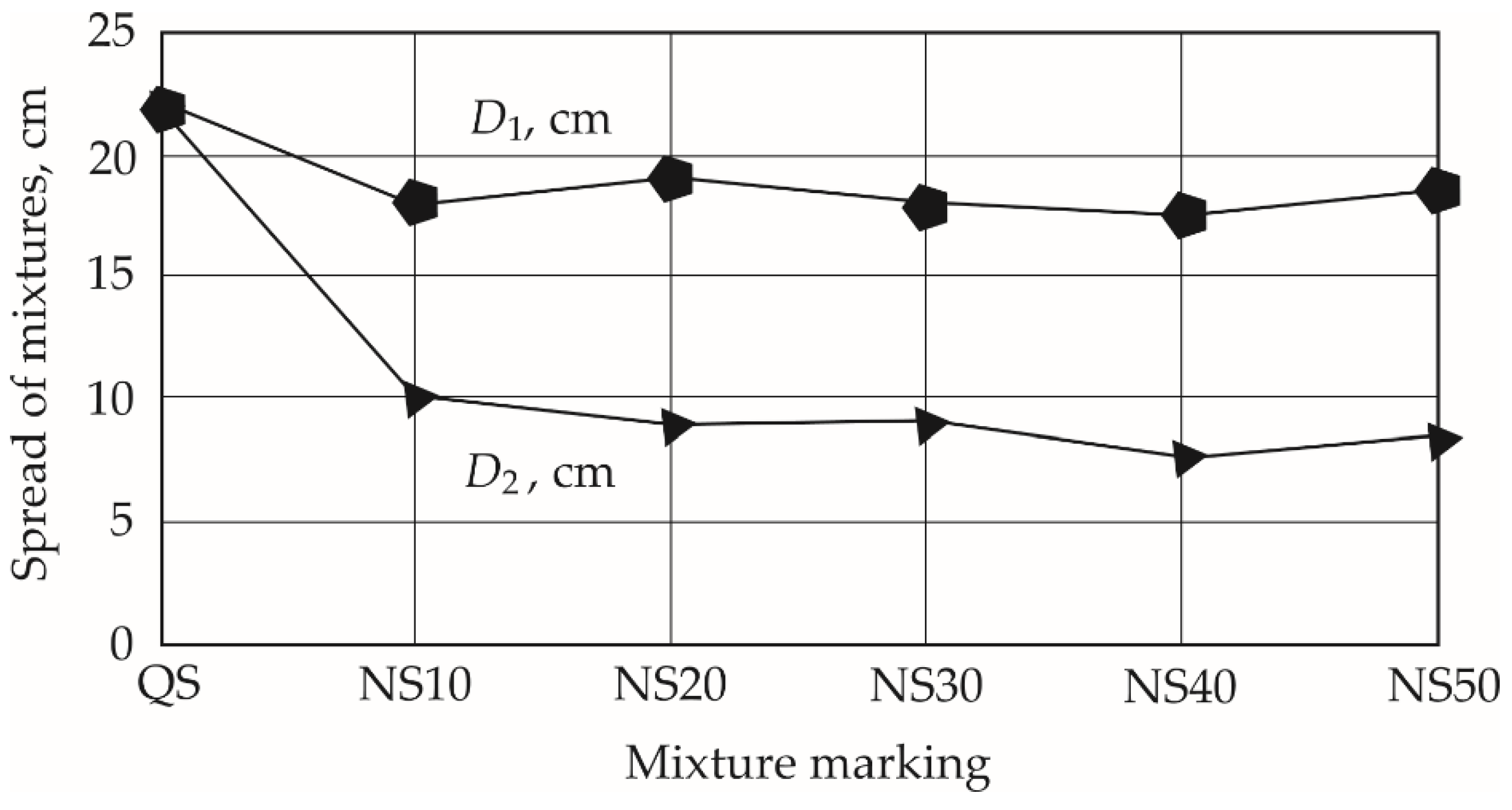

In order to reduce the use of quartz sand for thin-bed GRC mixtures, workability was investigated for all mixtures under consideration. All mixtures were tested, and the most representative trends were selected for visual use of the results. The use of alternative aggregates significantly decreased the workability of the mix, in some cases resulting in high fiber-matrix segregation. Determination of regular slump according to Suttard’s viscometer height (

h) alone is not sufficient to describe in detail the workability of such mixes. The spread diameters of mix

D1 and

D2, which characterize the segregation effect (

Figure 3) must also be measured.

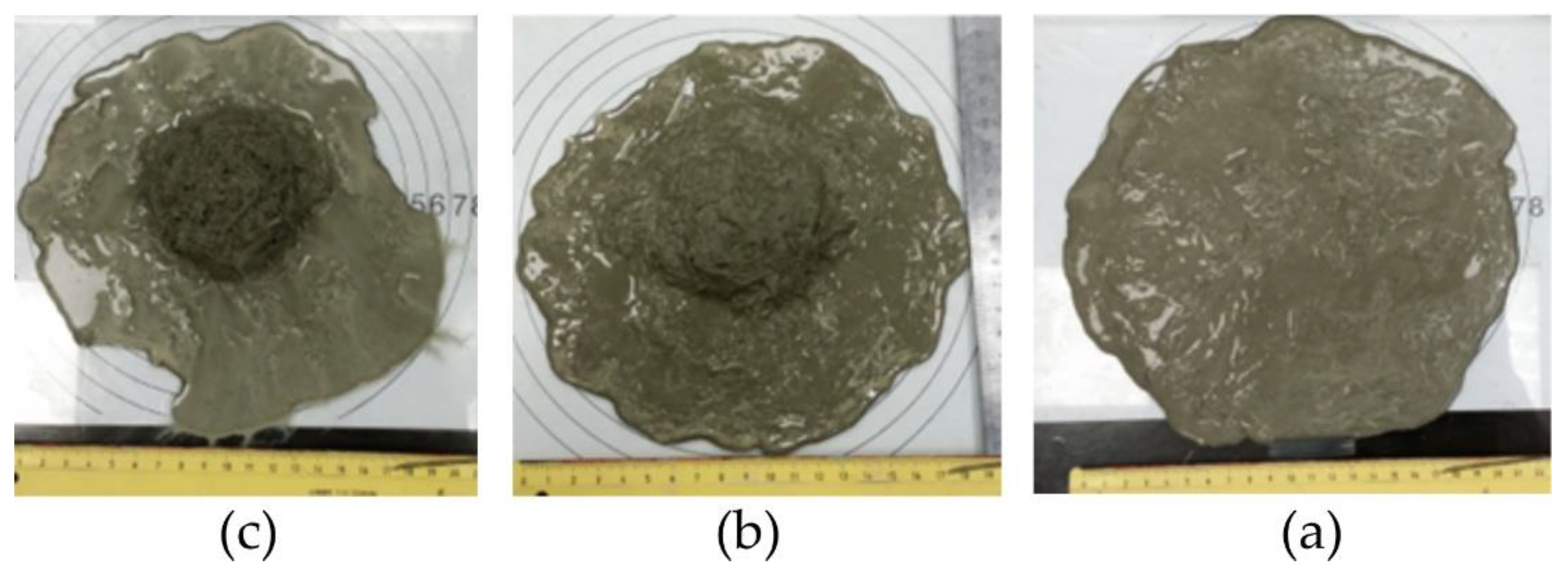

Figure 4 shows the different spread tendencies of the concrete mix. As shown in

Figure 4a, the best spread was determined in a concrete mix that contains only one type of aggregate (quartz sand), and allows a self-leveling GRC mix to be obtained. The spread is 22 cm. The analyzed sample reaches full slump. A full slump is not reached when half of the quartz sand is replaced with granite screenings or natural sand (

Figure 4b,c).

Spread can be seen in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. Replacement of quartz sand with 50% granite siftings or natural sand shows a decrease in spread. A greater spread reduction is observed when using the fine grains of granite (

Figure 5). Spread

d1 decreases by 31.8%, with 50% fine grains of granite (GS50) and by 15.9% with 50% of natural sand (NS50). In the case of spread

d2, the same tendencies are observed when using both 10% of granite siftings (GS10) and 10% of natural sand (NS10) (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). In both cases, a sudden decrease in the spread of the concrete mix is observed. This can be explained by studying the elongation of the aggregate. In the first case, it decreases to 9 cm, and in the second case to 10 cm.

Slump tests (

Figure 7) have shown a decrease from 4.3 cm to 2.4 cm (44.18%) in the case of granite siftings and a decrease of 3.7 cm in the case of natural sand (13.95%). A number of studies with regular concrete have shown that aggregate particle shape and aggregate surface characteristics are important factors in determining the water-cement ratio of a concrete mix – the larger the particle surface area, the greater the amount of water required to obtain a concrete mix of the required workability [

14]. Angled particles can increase the compressive strength of concrete, however the workability of the mix worsens [

40].

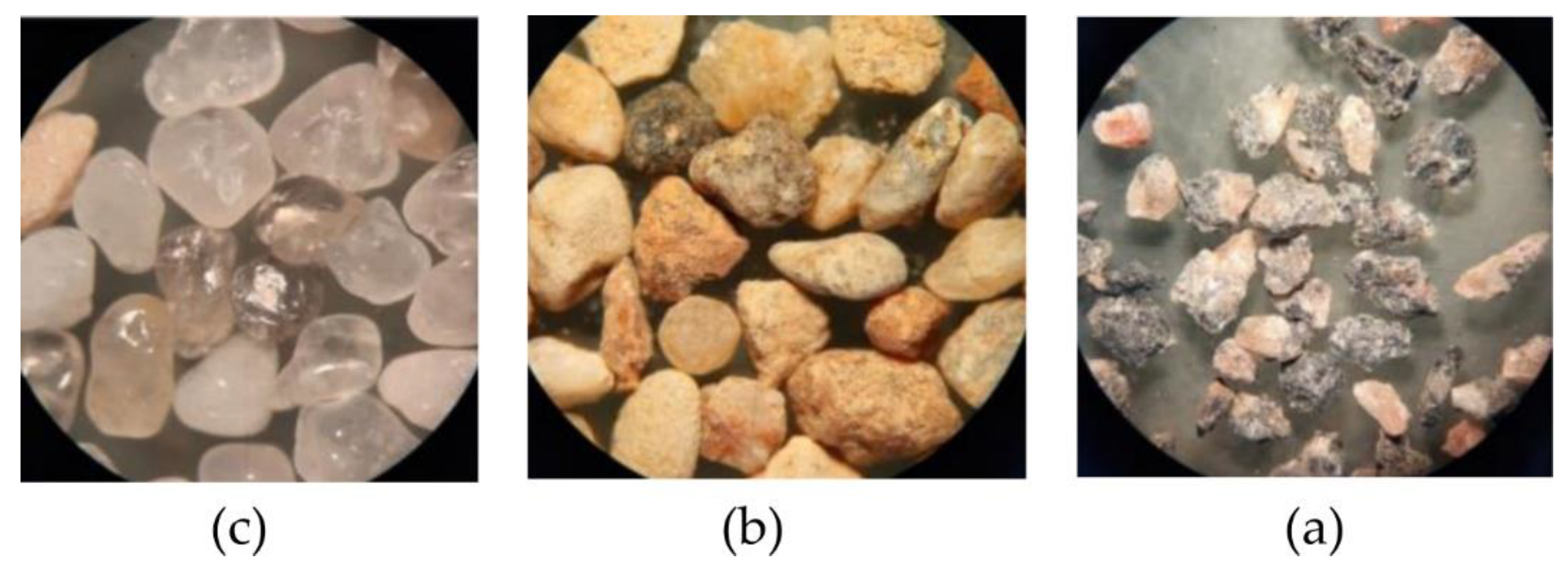

The quartz sand particles used in these studies have a spherical shape with smooth surfaces, resulting in less friction between the cement matrix, the aggregate, and the fibers (

Figure 8c). However, sand having a more uniform and spherical particle shape and providing less concrete voids will improve flow [

39]. Sands with higher roundness value also have higher length-width ratio [

41]. There are almost no studies on the properties of granite stiftings, but analysis of natural and artificial sand surfaces has been performed. On the one hand, natural sand has a smooth and round surface after water washing, movement and wear over a long period of time, while manufactured sand particles have a rough surface, sharp edges and corners and low roundness, with more inter-particle friction and interlocking, and therefore require more cement paste to pack and lubricate [

21]. Granite siftings particles have a plate-like shape with sharp edges, which increases the internal friction in the matrix, the fibre gets trapped between the larger particles, and the fine particles pass through the gaps together with the cement mortar (

Figure 8a). Particles of the natural sand aggregate are shaped like irregular spatial polygons, therefore the workability parameters of mixes are closer in composition to the granite aggregate (

Figure 8b).

The consistency and segregation of concrete depend on the shape of the aggregate particles, as shown by consistency and segregation studies. A number of particle shape parameters have been developed by researchers and are used in numerical modeling of particle mix density [

10]. However, other researchers have proposed using simplified shape indices (spherical mass, flatness, and elongation) in the study of concrete mix consistency problems [

4]. In this work, the elongation index is chosen as such a parameter, which can be determined by simple visual means, such as microscopic photographs and plotting software. An increase in the elongation index of the aggregate particles of just 3% reduces the dispersion of the mixture by 10% when natural sand is used instead of quartz sand. When irregularly shaped aggregate (granite siftings) is used, the particle elongation index increases (

Table 5) by 33% compared to quartz sand, and the spread of the mixture decreases accordingly to 50%. Increasing the content of natural sand from 10% to 50% increases the segregation index from 1.9 to 2.6, and from 2.6 to 3.5 with granite siftings. These parameters indicate that mixtures with a predominance of spherical particles, ensuring uniform dispersion of the cement matrix and fibers, are more in demand when a well-laid pavement mixture is required.

According to the amount of each fraction on different sieves, the average elongation indices for the entire aggregate were calculated:

Iq= 1.40 (quartz sand),

Ins= 1.44 (natural sand),

Igs= 1.87 (granite siftings) (see

Table 5) The predominant fraction in quartz sand is from 0.125 to 0.25 mm, while in natural sand the various fractions are distributed more evenly. In the case of granite siftings, the maximum amount of particles is from 0.5 to 1 mm. According to the results of the tests, concrete mix workability worsens with both an increase of the particle elongation index and an increase in the amount of larger particles. The highest values of the elongation index were determined in the case of granite siftings, as shown in

Figure 8. In this case, the elongation value increases by 33.58%, and the concrete mix spread decreases accordingly to 50%. In the case of natural sand, the increase in the elongation index is only 2.86%. But even in this case, the spread of the mix decreases by 10%.

Research on conventional concretes has shown that the shape of the aggregate particles and the characteristics of the aggregate surface are important factors in determining the water/cement ratio of the concrete mix. The larger the surface area of the particles, the greater the amount of water needed to obtain a mix of the required consistency with a given amount of aggregate [

40]. Angular particles can increase the compressive strength of concrete but degrade the consistency of the mix [

40]. The quartz sand particles used in these studies are characterized by their spherical shape and smooth surfaces, resulting in lower friction between the cementitious matrix, aggregate, and fibers. Granite siftings particles have a plate-like shape with sharp edges, which increases the internal friction in the matrix, trapping the fibers between the coarser particles and allowing the fines to pass through the gaps with the cementitious mortar. The particles of regular sand aggregate are irregularly shaped spatial polygons, so the consistency parameters of the mixtures are closer to those of compositions with granite aggregate.

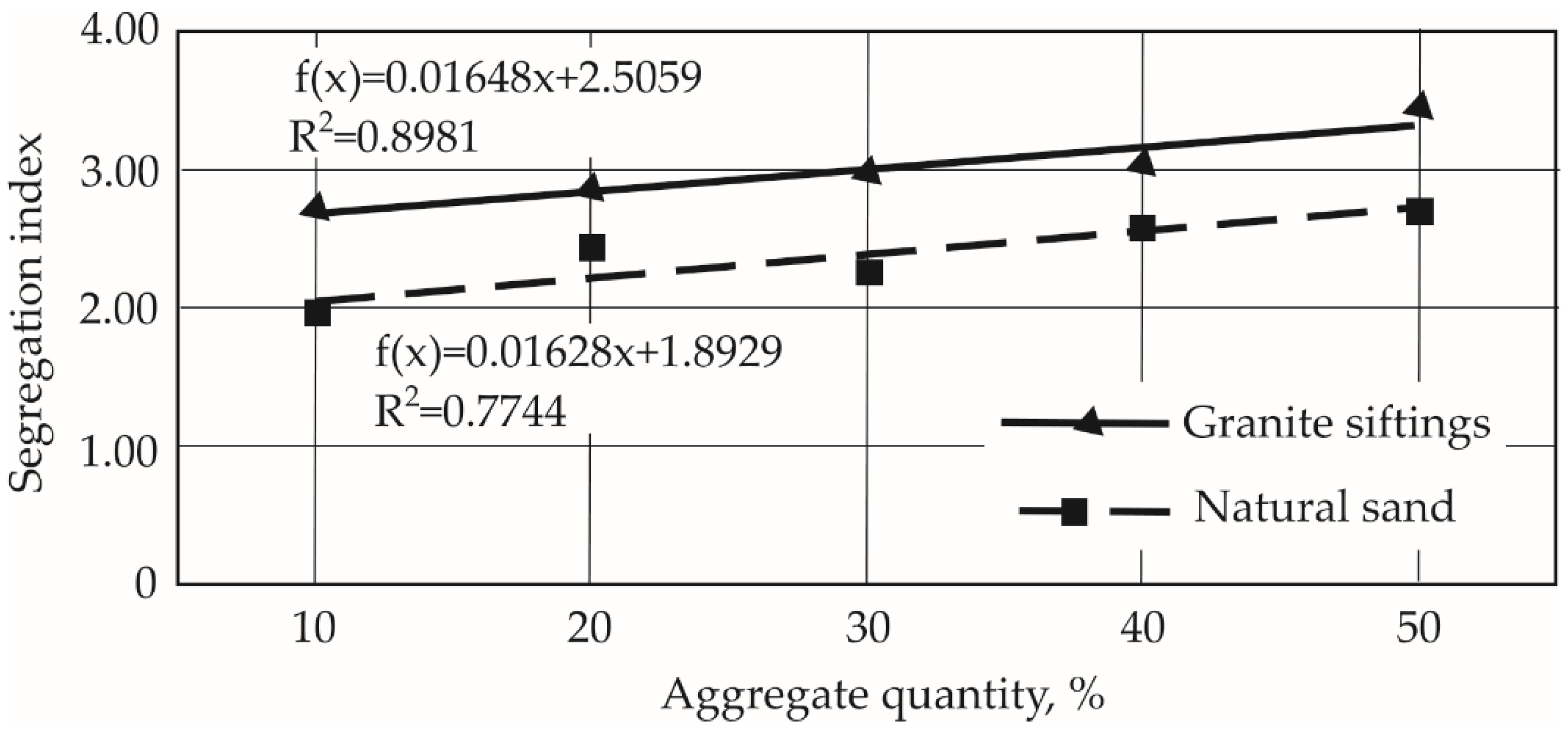

Segregation index tendencies are presented in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. The segregation index is a measure used to quantify the degree of separation between different components in a concrete mix. Linear dependencies are shown in

Figure 9. Research shows that as the proportion of natural sand and granite siftings in the mix increases, the segregation index also increases. This indicates a direct relationship between the amount of these alternative aggregates and the mix’s tendency to segregate. As the amount of natural sand and granite sifting increases, the value of the segregation index also increases. The segregation index values are consistently higher for concrete mixes with granite siftings compared to those with natural sand. If quartz sand is replaced with maximum amounts of granite siftings and natural sand, the segregation index with granite aggregate is 1.27 times higher. The fillers differ in their particle surface. Sand has a smooth particle surface, whereas granite has a rough surface.

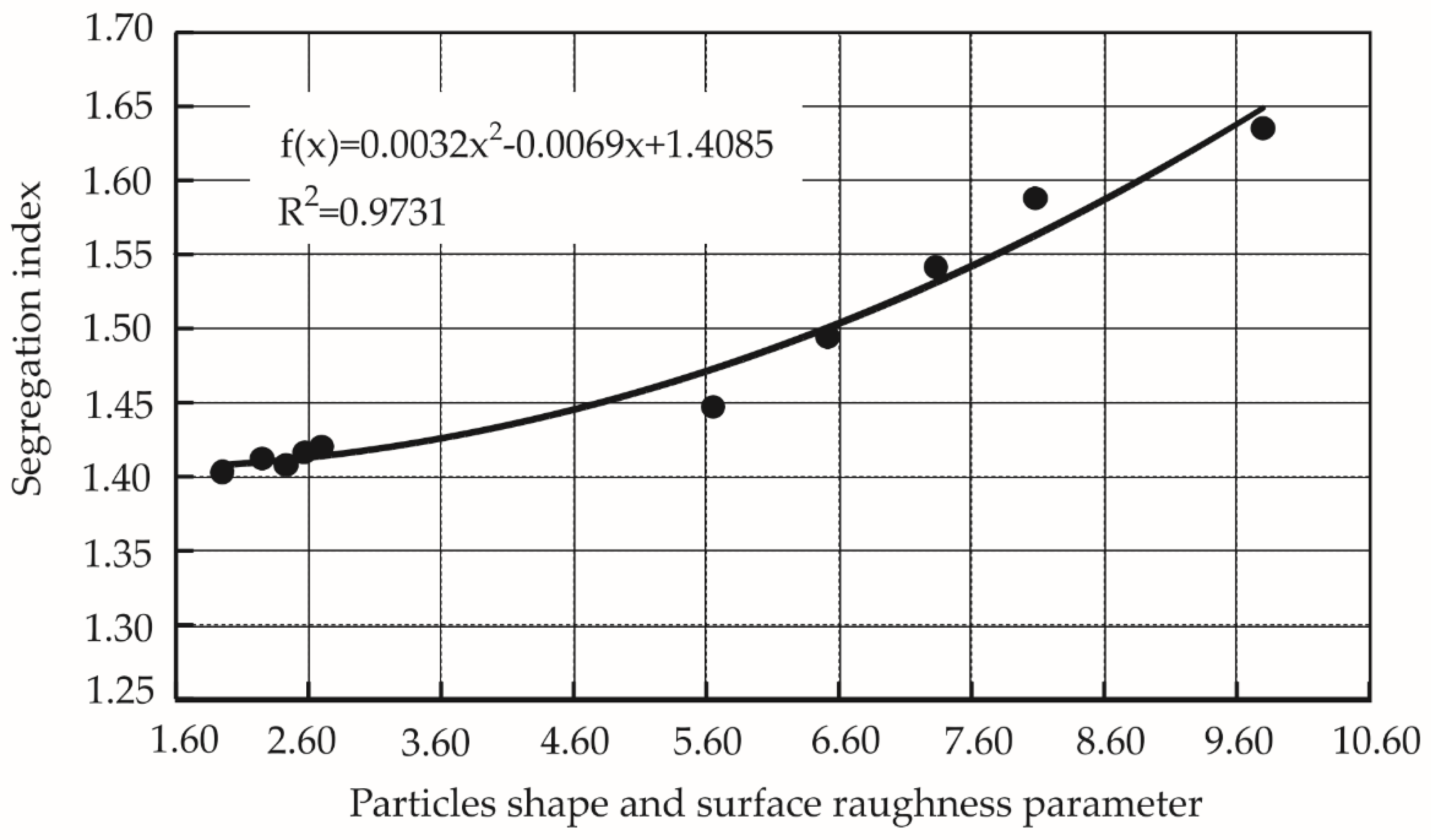

The segregation index is influenced not only by the shape of the filler but also by the surface roughness. The particle shape and surface roughness parameter

J was calculated using data provided in the study of the surface parameters of fine aggregate particles [

41]. The dependence of the segregation index of mixtures on the shape (elongation) and surface roughness of the filler particles is shown in

Figure 10. This figure shows that the dependenceof the segregation index on these parameters can be described by a square function. The square function of the dependency indicates that small changes in elongation and roughness can leas to larger changes in the segregation index. This suggests a non-linear relationship, where changes in particle shape and roughness can significantly impact segregation tendencies in complex manner.

In summary, can be emphasized the crucial role of aggregate characteristics in determining concrete workability and stability. Research reveals that both shape and surface texture aggregates significantly influence the segregation tendencies, with rougher and more elongated particles leading to higher segregation index. This comprehensive understanding can inform the selection and proportioning of aggregates in concrete mix designs to achieve desired workability and minimize segregation.