Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Challenge to Reductionism in Complex Systems

1.2. The Problem of Incommensurability

- 1)

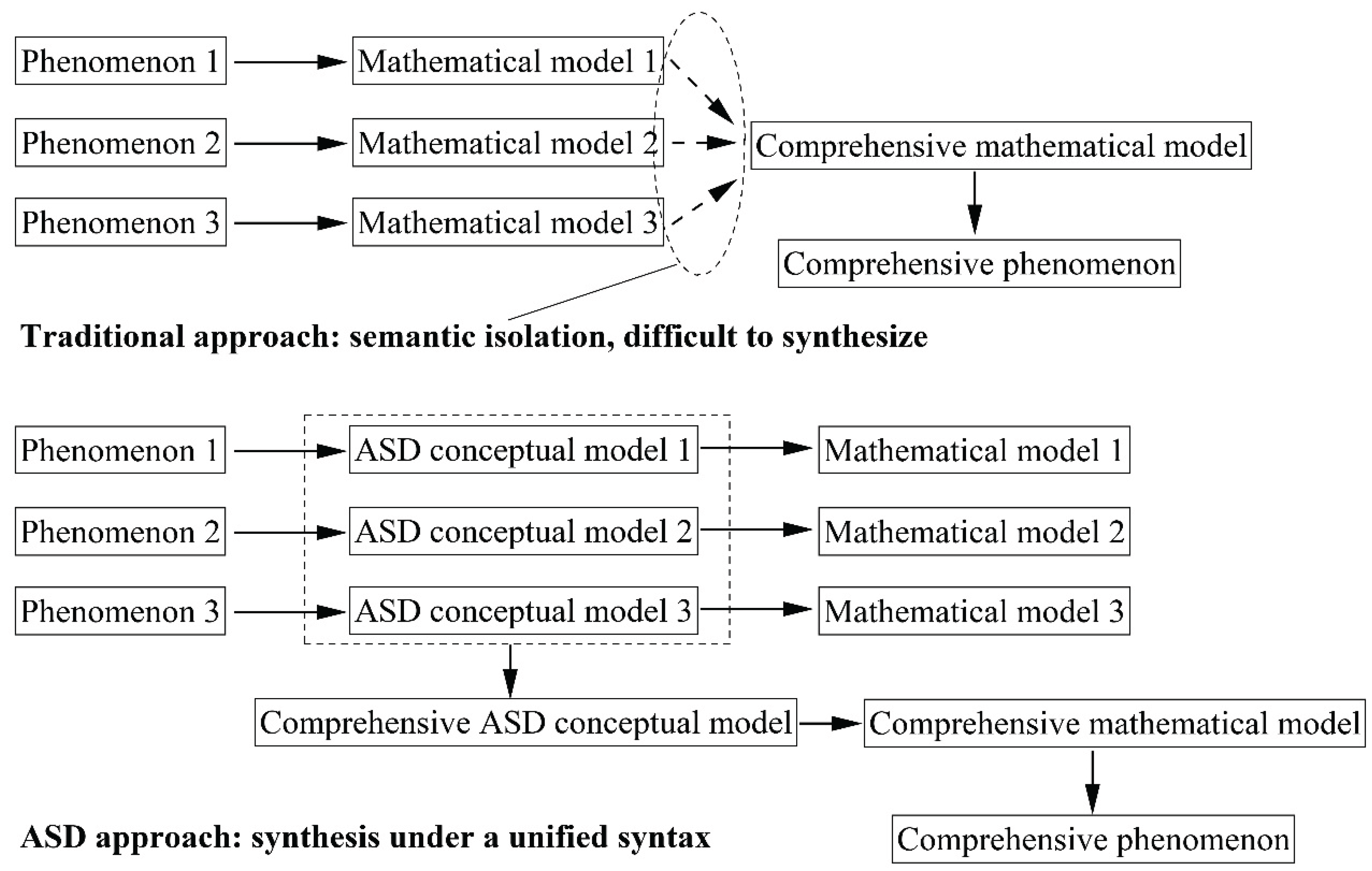

- Semantic Incompatibility: Across sub-fields, the scale of the study object, the primary variables of interest, and the mechanisms that induce change often diverge. Furthermore, inconsistent terminology prevents the semantic alignment necessary for interdisciplinary synthesis.

- 2)

- Logical Disconnect: The causal relationships between different physical mechanisms are not systematically characterized, breaking the chain of inference.

- 3)

- Formal Rigidity: Existing mathematical models are often valid only under specific boundary conditions and lack the formal flexibility to be seamlessly coupled.

1.3. The Gap in Existing Systems Science

1.4. Introducing Axiomatic System Dynamics (ASD)

2. Fundamental Axioms

3. Fundamental Concepts

3.1. Primary Concepts

3.2. Secondary Concepts

3.3. Tertiary Concepts

4. Illustrative Applications

4.1. Newtonian Particle Mechanics

4.2. The Stress-Strain Constitutive Relation of Materials

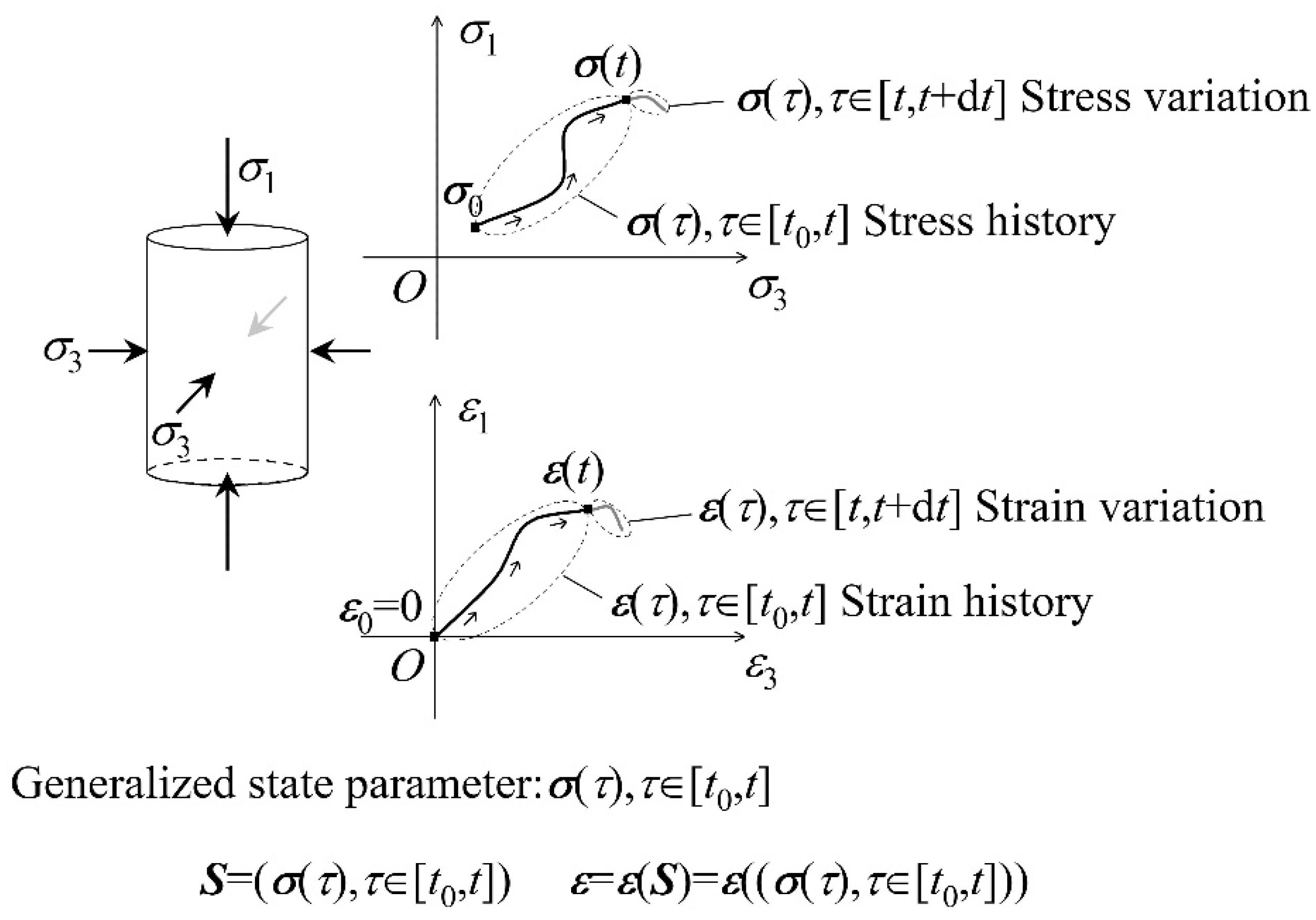

4.2.1. Path Dependence and Non-Markovian Nature

4.2.2. Generalized State Parameters and Mathematical Modeling

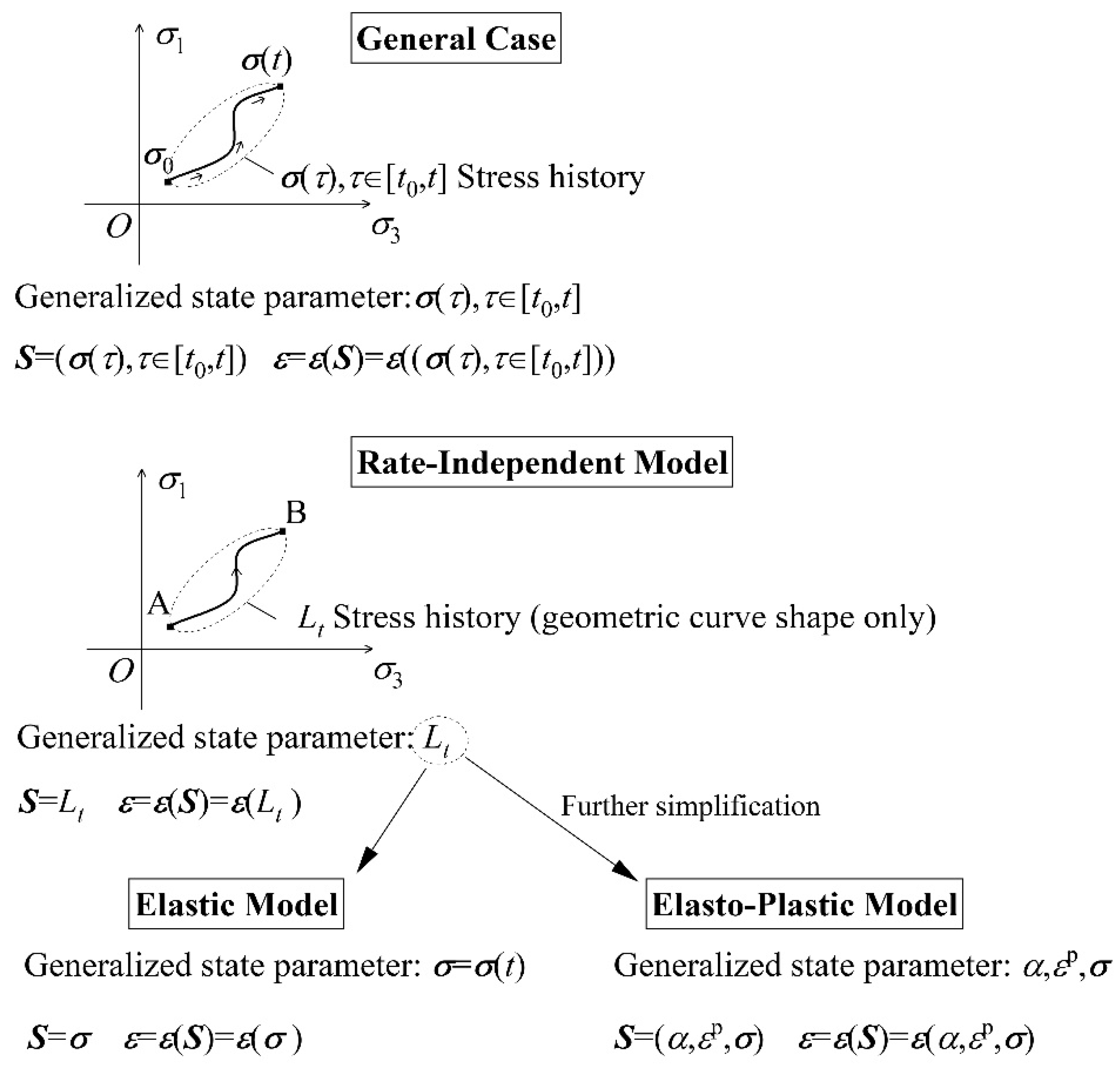

4.2.3. Rate-Independent Models (Elastic and Elasto-Plastic)

- The geometric curve shape of the stress history in stress space (as illustrated by curve AB in Figure 2) uniquely determines the element's state at time , regardless of the rate at which the loading is performed. In the context of rate-independent models, where no confusion arises, the curve shape is also referred to as the stress history.

- Starting from a given state at time , the state increment during the interval depends solely on the curve shape of the stress variation in stress space. Furthermore, as the characteristic time scale approaches zero,depends solely on the vector formed by the two endpoints of this curve—namely, the stress increment . Geometrically, the stress history at time "adds" this increment to yield the stress history at time .

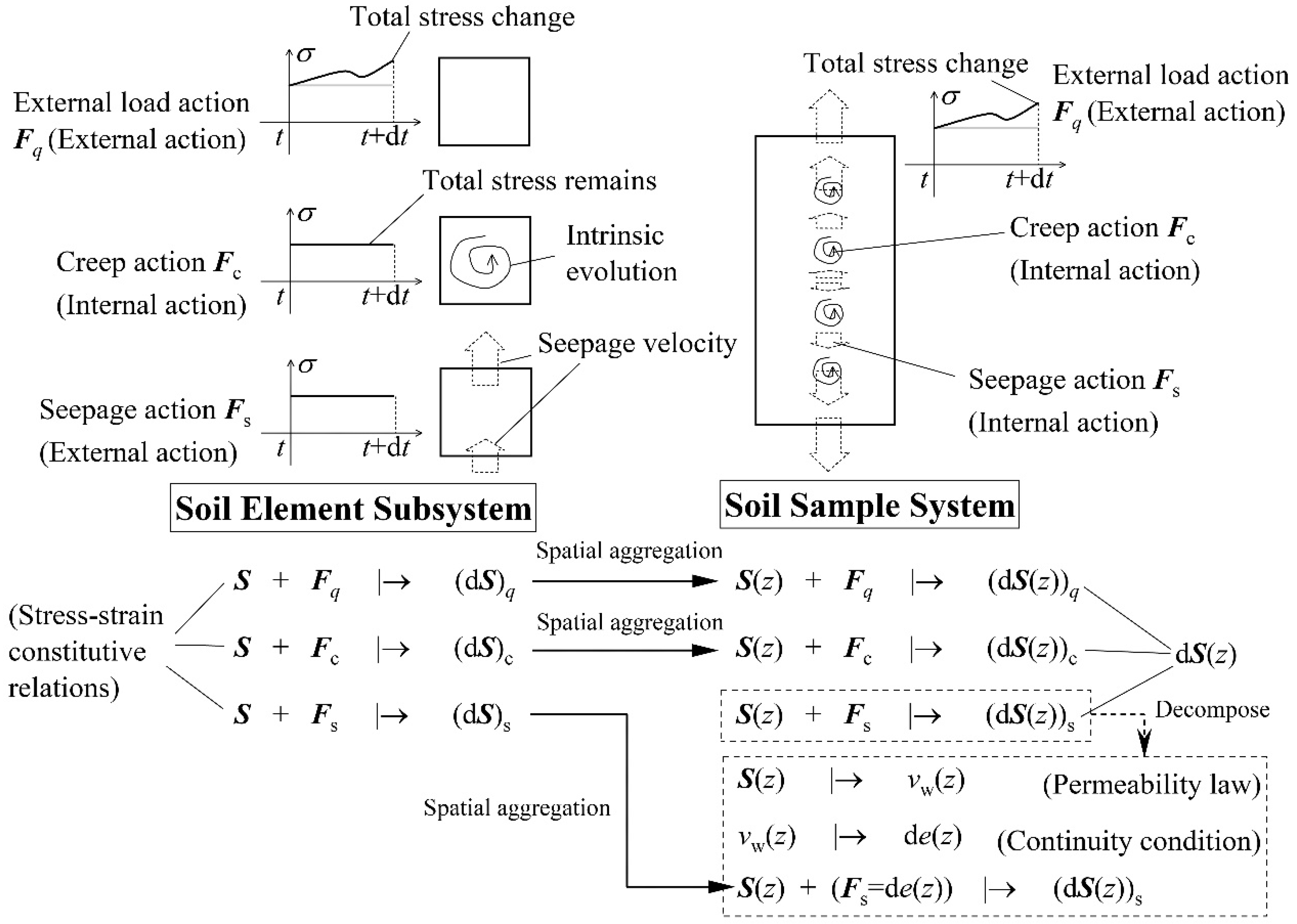

4.2.4. Discussion on Action Partitioning

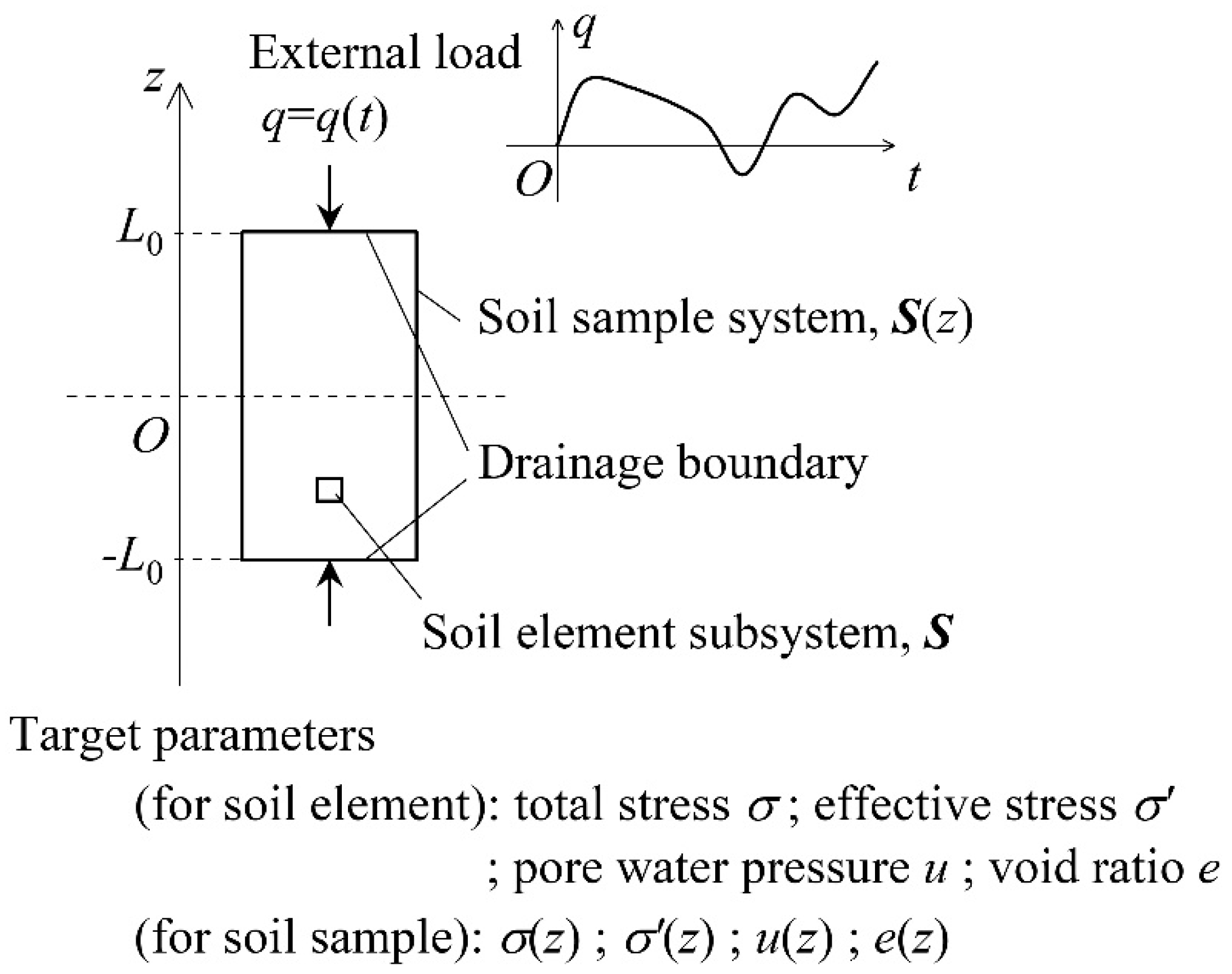

4.3. One-Dimensional Consolidation of Saturated Soil

4.3.1. Soil Element Subsystem

4.3.2. Soil Sample System

4.3.3. Derivation of Specific Mathematical Models

5. Methodology: From Conceptual Model to Mathematical Model

5.1. The Limitations of Direct Modeling

5.2. The Conceptual Model as a Semantic Bridge

- Forward Path: Phenomenon → Conceptual Model (Semantic Abstraction) → Mathematical Model (Quantitative Implementation).

- Reverse Path: Existing Mathematical Model → Conceptual Model (Semantic Extraction).

-

Phenomenon Identification and System Division:

- ∘

- Define the object of study and its boundaries.

- ∘

- Establish the system's spatial scale and the observational time scale.

- ∘

- Identify the research objective and select appropriate target parameters.

-

Conceptual Modeling:

- ∘

- Clarify the logical distinction between internal and external actions and determine the decomposition method for these actions.

- ∘

- Establish the generalized constitutive relations for all identified actions.

-

Mathematical Modeling:

- ∘

- Determine the quantification methods for both state and action (e.g., selecting state parameters and external action paths).

- ∘

- Guided by the conceptual model, establish the specific mathematical expressions for all generalized constitutive relations.

- ∘

- Explicitly define the meaning of each parameter within these mathematical expressions.

-

Model Validation and Refinement:

- ∘

- Calibrate parameters and validate the mathematical model's rationality through experiments or numerical computation.

- ∘

- If systematic deviations occur that cannot be eliminated by parameter correction, return to the Mathematical Modeling stage or, if necessary, the Conceptual Modeling stage.

- ∘

- Continuously engage in an iterative cycle of refinement between Conceptual Modeling and Mathematical Modeling.

5.3. Modularity and the "Platform" Approach

6. implications and limitations

6.1. Methodological and Philosophical Implications

6.1.1. Ontological State and Epistemological Parameter: A Fundamental Distinction

6.1.2. Axiom 2 and the Non-Arbitrary System Boundary

6.1.3. The B-A Principle and the Logic of Control Experiments

6.1.4. Fulfilling the Vision of General Systems Theory (GST)

6.2. Limitations of the Current Framework and Future Directions

- Soft Systems: Parameters in these domains often possess a high degree of subjectivity and complexity (e.g., "satisfaction"), rendering them difficult to quantify with standard scientific instrumentation. Consequently, determining the Ontological State of such systems presents a significant measurement challenge that requires new quantification methodologies.

- Stochastic Systems: For systems exhibiting inherent randomness, a potential resolution is to encapsulate randomness as an intrinsic property of the state itself. Under this paradigm, parameters are treated as probability distributions rather than scalar values. The evolution of the system's state (the distribution) remains deterministic, even if the specific physical manifestation is probabilistic.

7. Conclusions

- Newtonian Particle Mechanics: Demonstrated the framework's capacity to model elementary dynamics, formally re-conceptualizing inertia as the system's Internal Action and linear motion as its inherent state creep.

- Material Stress-Strain Constitutive Relations: Validated the application to Non-Markovian systems, highlighting how the generalized state parameter formally incorporates history-dependence, thus providing a rigorous axiomatic home for system "memory."

- Saturated Soil Consolidation: Demonstrated the framework's effectiveness in handling multi-scale, multi-mechanism coupled systems. This application illustrated the crucial point that the partition of actions (internal vs. external) is not intrinsic but is fundamentally dictated by the research objective, provided it strictly adheres to Axiom 2.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashby, W. R. (1956). An introduction to cybernetics.

- Baligh, M. M., & Levadoux, J. N. (1978). Consolidation theory for cyclic loading. Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division, 104(4), 415-431. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, D., Cabrera, L. L., & Midgley, G. (2023). The four waves of systems thinking. Journal of Systems Thinking, 1-51. [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P., & Poulter, J. (2020). Soft systems methodology. In Systems approaches to making change: A practical guide (pp. 201-253). London: Springer London.

- Chen, C. T. (1984). Linear system theory and design. Saunders college publishing.

- Dill, E. H. (2006). Continuum mechanics: elasticity, plasticity, viscoelasticity. CRC press. [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, V., & Mazzoli, S. (2021). Theory of effective stress in soil and rock and implications for fracturing processes: a review. Geosciences, 11(3), 119. [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, V. (2022). 1923–2023: one century since formulation of the effective stress principle, the consolidation theory and Fluid–Porous-Solid interaction models. Geotechnics, 2(4), 961-988. [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. (1998). The mathematical theory of plasticity (Vol. 11). Oxford university press.

- Holtz, R. D., Kovacs, W. D., & Sheahan, T. C. (1981). An introduction to geotechnical engineering (Vol. 733). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-hall.

- Islam, M. N., & Gnanendran, C. T. (2017). Elastic-viscoplastic model for clays: Development, validation, and application. Journal of Engineering Mechanics, 143(10), 04017121. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M. C. (2016). Systems thinking: Creative holism for managers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Jackson, M. C. (2019). Critical systems thinking and the management of complexity. John Wiley & Sons.

- Kauffman, S. A. (1992). The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution. In Spin glasses and biology (pp. 61-100).

- Khan, A. S., & Huang, S. (1995). Continuum theory of plasticity. John Wiley & Sons.

- Lai, W. M., Rubin, D., & Krempl, E. (2009). Introduction to continuum mechanics. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Midgley, G. (2000). Systemic intervention. In Systemic intervention: Philosophy, Methodology, and practice (pp. 113-133). Boston, MA: Springer Us. [CrossRef]

- Radhika, B. P., Krishnamoorthy, A., & Rao, A. U. (2020). A review on consolidation theories and its application. International Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, 14(1), 9-15. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G. P. (2011). Reflections on the foundations of system dynamics. System dynamics review, 27(3), 219-243. [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D. (2015). General systems theory: Its present and potential. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 32(5), 522-533. [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D. (2017). Systems research and the quest for scientific systems principles. Systems, 5(2), 25. [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J. (2018). System dynamics at sixty: the path forward. System Dynamics Review, 34(1-2), 5-47. [CrossRef]

- Suh, N. P. (1998). Axiomatic design theory for systems. Research in engineering design, 10(4), 189-209.

- Terzaghi, K. (1925). Principles of soil mechanics. IV. Settlement and consolidation of clay. Engineering News-Record, 95, 874.

- Terzaghi, K. (1943). Theoretical soil mechanics.

- Terzaghi, K., Peck, R. B., & Mesri, G. (1996). Soil mechanics in engineering practice. John wiley & sons.

- Thurner, S., Hanel, R., & Klimek, P. (2018). Introduction to the theory of complex systems. Oxford University Press.

- Von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General system theory. New York, 41973(1968), 40.

- Wilson, N. E., & Elgohary, M. M. (1974). Consolidation of soils under cyclic loading. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 11(3), 420-423. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. H., & Graham, J. (1994). Equivalent times and one-dimensional elastic viscoplastic modelling of time-dependent stress–strain behaviour of clays. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 31(1), 42-52. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. H., & Graham, J. (1996). Elastic visco-plastic modelling of one-dimensional consolidation. Geotechnique, 46(3), 515-527. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. H., & Graham, J. (1999). Elastic viscoplastic modelling of the time-dependent stress-strain behaviour of soils. Canadian geotechnical journal, 36(4), 736-745. [CrossRef]

- Ying-chun, Z., & Kang-he, X. (2005). Study on one-dimensional consolidation of soil under cyclic loading and with varied compressibility. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A, 6(2), 141-147. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).