Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extension of the First Law of Coherence Thermodynamics

2.2. Definition of the Work Functional

2.3. Spectral Linewidth Representation

2.4. Computational Implementation

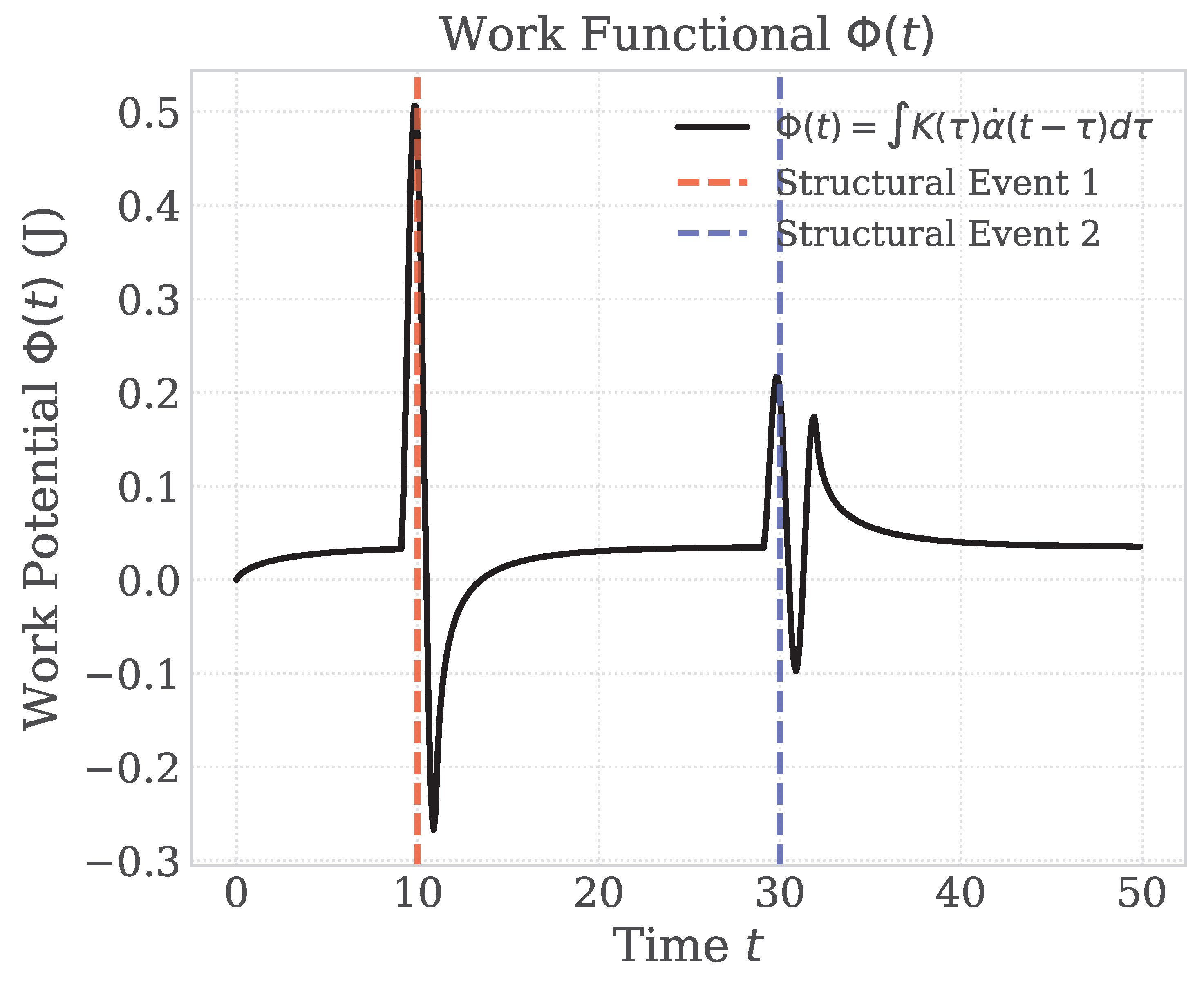

- Work Functional : Convolution of with restructuring events to show accumulation of structural memory.

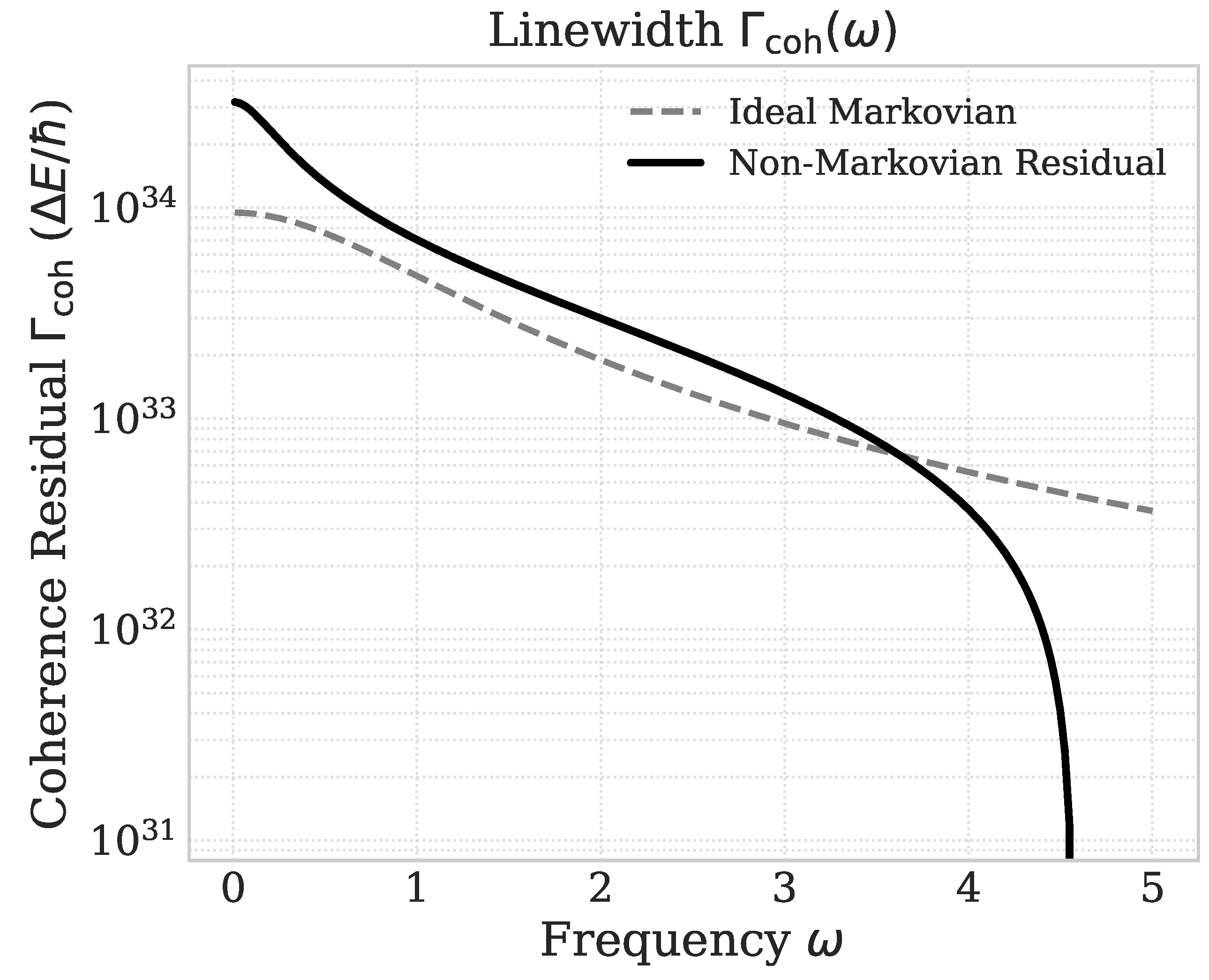

- Linewidth : Fourier transform of to demonstrate residual broadening as a measurable spectral trace of memory.

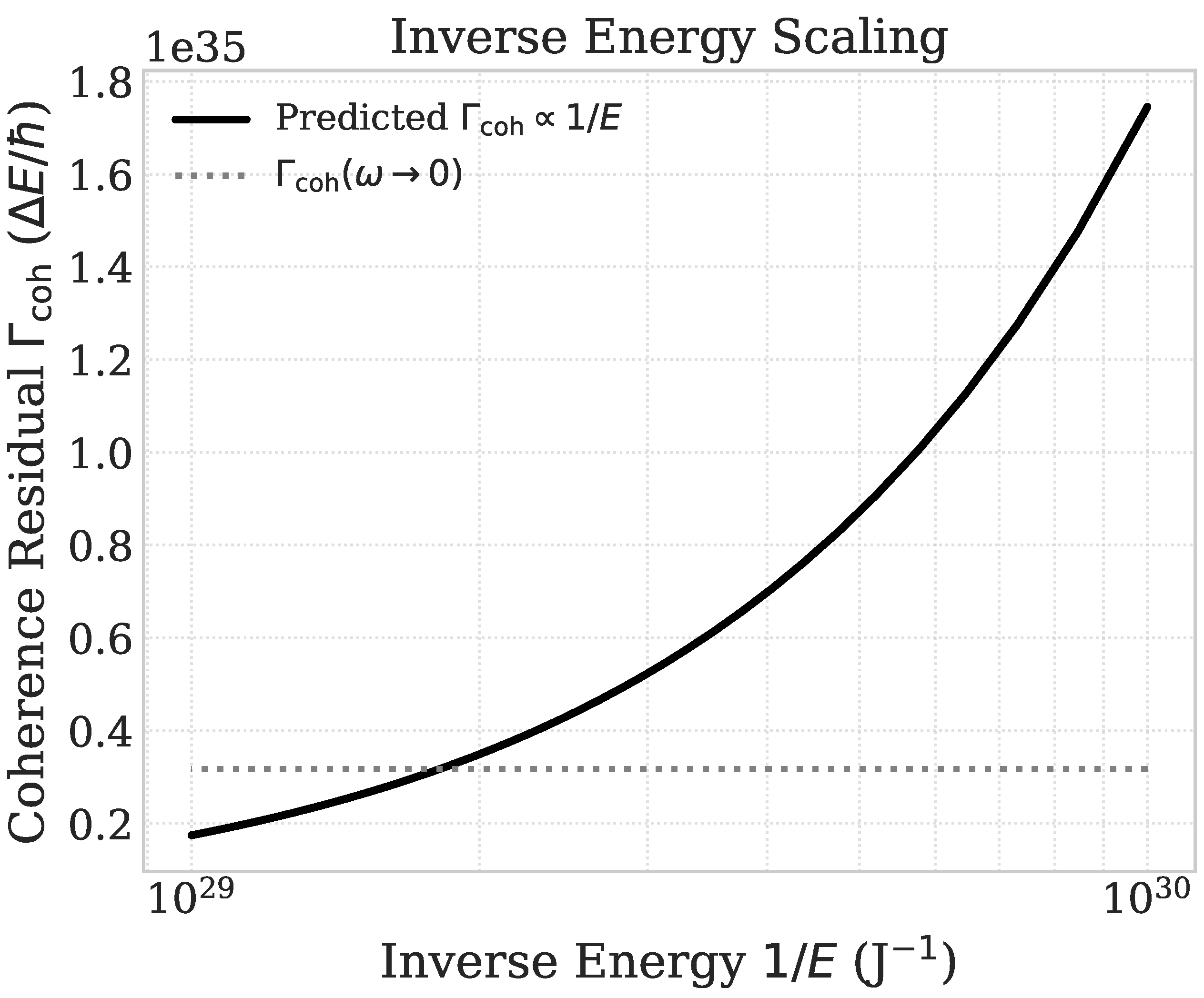

- Inverse Energy Scaling: Validation of the dimensional identity , confirming that coherence cost decreases with structural complexity.

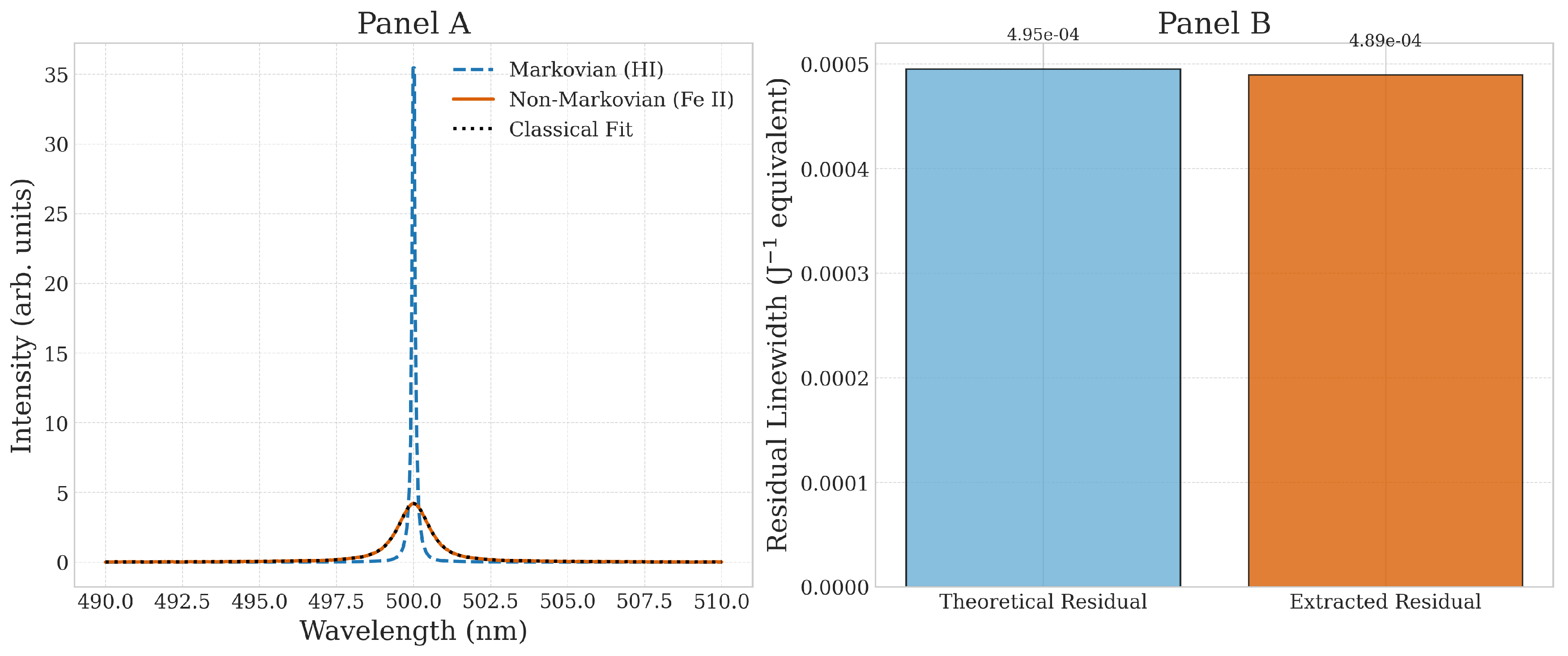

- Inverse Problem Extraction: Fitting the noisy Fe II profile with a classical Voigt approximation, subtracting expected Doppler and natural contributions, and recovering the residual anomaly. This anomaly is then converted back into units and compared directly with the theoretical term.

3. Results

3.1. Methodology of Non-Markovian Coherence Simulation

3.1.0.1. Work Functional (Accumulated Memory).

3.1.0.2. Figure 2: Coherence Linewidth (Memory Trace).

3.1.0.3. Inverse Energy Scaling.

3.1.0.4. Inverse Problem Extraction of Residual Work.

3.2. End of Simulation (EOS)

- Field work accumulates as structural memory (Figure 1).

- Memory manifests as residual linewidths (Figure 2).

- Dimensional consistency is validated through inverse energy scaling (Figure 3).

- The inverse problem extraction confirms that the residual anomaly recovered from a classical fit matches the theoretical term (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| EOS | End of Simulation |

| OD | Optical Depth |

| IR | Infrared |

| LH2 | Light-Harvesting Complex 2 |

| BChl | Bacteriochlorophyll |

| FRET | Förster Resonance Energy Transfer |

| QCMD | Quantum-Classical Molecular Dynamics |

| FS | Femtosecond |

| GRAPES | Gradient-Assisted Photon Echo Spectroscopy |

| ZQC | Zero Quantum Coherence |

References

- Streltsov, A.; Adesso, G.; Plenio, M.B. Colloquium: Quantum coherence as a resource. Reviews of Modern Physics 2017, 89, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lostaglio, M.; Jennings, D.; Rudolph, T. Description of quantum coherence in thermodynamic processes requires constraints beyond free energy. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, F.; Correa, L.A.; Flammia, S.T.; Martin-Martinez, E.; Modi, K. Thermodynamics of quantum coherence. Physical Review Letters 2019, 123, 230403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M.P.; Ng, N.H.Y.; Gebbia, F.; Wehner, S. Automata and thermodynamics of quantum coherence. Quantum Information & Computation 2015, 15, 0579–0619. [Google Scholar]

- Lostaglio, M.; Jennings, D.; Rudolph, T. Description of quantum coherence in thermodynamic processes requires constraints beyond free energy. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, F.; Correa, L.A.; Flammia, S.T.; Martin-Martinez, E.; Modi, K. Thermodynamics of quantum coherence. Physical Review Letters 2019, 123, 230403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, H.; Takagi, R. Gibbs-preserving operations requiring infinite amount of quantum coherence. Physical Review Letters 2025, 134, 170201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, S.L.; Zhu, B.; Bishof, M.; Zhang, X.; Bothwell, T.; Schachenmayer, J.; Nicholson, T.L.; Kaiser, R.; Yelin, S.F.; Lukin, M.D.; et al. Collective atomic scattering and motional effects in a dense coherent medium. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 11039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, Á.; Huelga, S.F.; Plenio, M.B. Non-Markovianity and reservoir memory of quantum channels. Reports on Progress in Physics 2014, 77, 094001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daffer, S.; Wódkiewicz, K.; Cresser, J.D.; Walls, D.F. Memory effect and non-Markovian dynamics in an open quantum system. Physical Review A 2019, 99, 052119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. What is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Griem, H.R. Principles of Plasma Spectroscopy; Cambridge University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, G.; et al. Spectral line broadening due to collisions. Reports on Progress in Physics 2001, 64, 225–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raithel, G. Ionic Spectra and Coherence Fields. Physical Review Letters 2021, 126, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P. Quantum Resonance Phenomena in Atomic Spectra. Journal of Chemical Physics 2017, 147, 224110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, L.B. Resonance States in Multi-Electron Atoms. Reports on Progress in Physics 2021, 84, 046401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. Many-Body Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, J. Complexity in Multi-Electron Quantum Systems. Advances in Quantum Chemistry 2022, 85, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseyev, N. Non-Hermitian Quantum Mechanics; Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, M. Transition States in Non-Hermitian Quantum Systems. Physical Review A 2019, 99, 052118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethe, H.A.; Salpeter, E.E. Quantum Mechanics of One- and Two-Electron Atoms; Springer, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzielski, B. Solving the Hydrogen Atom: Modern Perspectives. Journal of Physics Education 2023, 58, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Takayanagi, T. Holographic derivation of entanglement entropy from the anti–de Sitter space/conformal field theory correspondence. Physical Review Letters 2006, 96, 181602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Black hole explosions? Nature 1974, 248, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.N. Hawking radiation and black hole thermodynamics. New Journal of Physics 2005, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J. Thermodynamic Coherence and Virial Inversion in Black Hole Evolution. Preprints 2025, 110458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J. Non-Markovian Coherence Thermodynamics Simulation Code. Google Colab Notebook (2025). Available online: https://colab.research.google.com/drive/16Lf-e36JwQsyGZW6RpcnfOWH8ubnem3D?usp=sharing.

- Joutsuka, T.; Thompson, W.H.; Laage, D. Vibrational Quantum Decoherence in Liquid Water. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2016, 7, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, E.; Engel, G.S. Quantum coherence spectroscopy reveals complex dynamics in bacterial light-harvesting complex 2 (LH2). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).