Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. CS

2.1. Stages and Biomarkers

2.2. Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype

2.3. Lipogenesis in Senescent Cells

2.4. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Senescent Cells

3. MASLD Pathogenesis

3.1. Microvescular and Macrovescular Type of Steatosis

3.2. The Implication of PLINs

3.3. PPARa and NF-κΒ

3.4. Mitochondrial Dysregulation

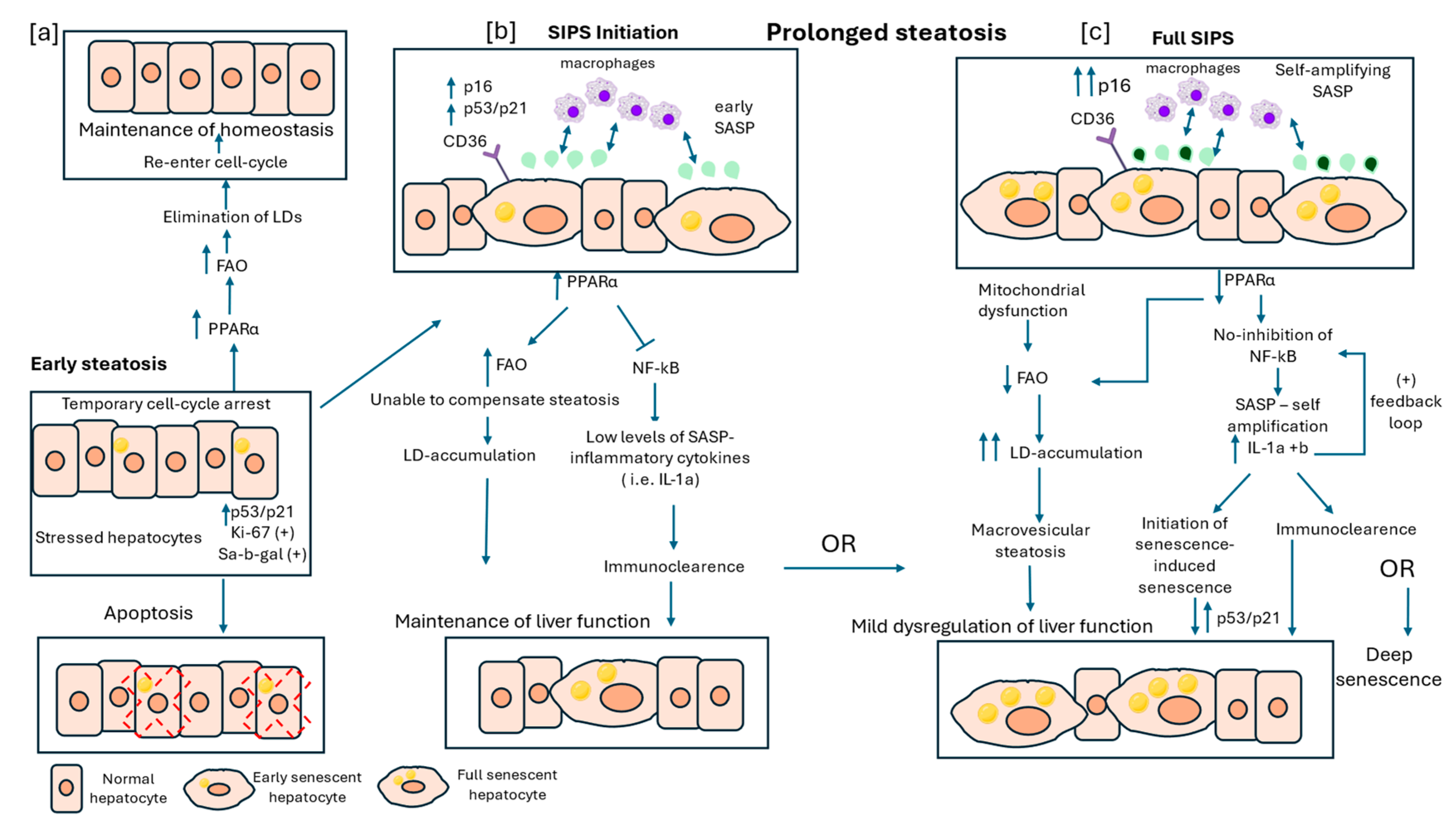

4. Interplay Between CS and LDs in MASLD

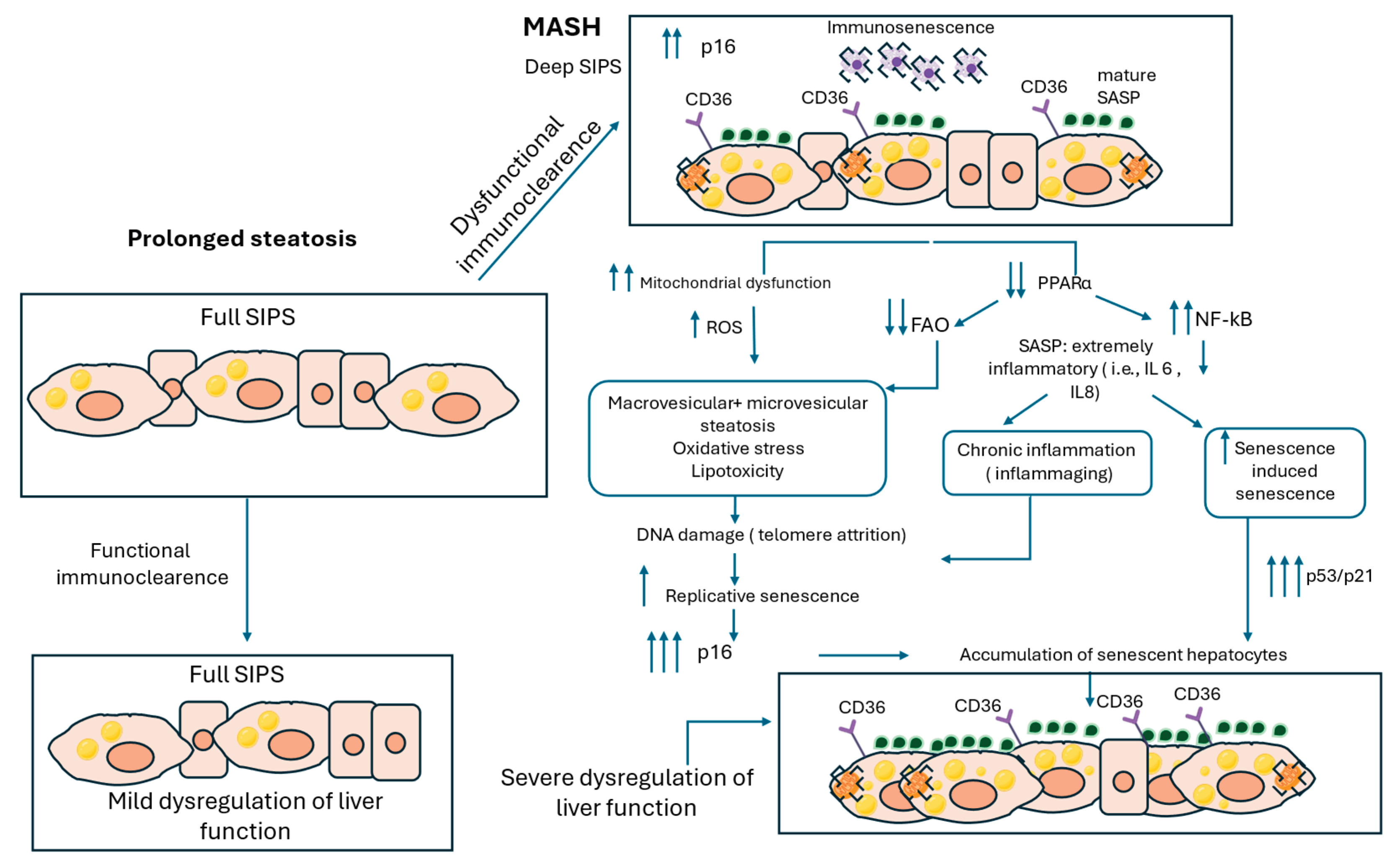

5. Interaction Between SIPS and RS in MASH

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATM | Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated |

| CD36 | Cluster of differentiation 36 |

| CS | Cellular senescence |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| FA | Fatty acid |

| FAO | Fatty acid oxidation |

| FASN | Fatty acid synthase |

| FFA | Free fatty acid |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LD | Lipid droplet |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RS | Replicative senescence |

| SA-β-gal | Senescence-associated β-galactosidase |

| SADF | Senescence-associated DNA damage foci |

| SAHF | Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SIPS | Stress-induced premature senescence |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| PLINs | Perilipins |

References

- L. HAYFLICK and P. S. MOORHEAD, "The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains," (in eng), Exp Cell Res, vol. 25, pp. 1961. [CrossRef]

- A. Prieur, E. A. Prieur, E. Besnard, A. Babled, and J. M. Lemaitre, "p53 and p16(INK4A) independent induction of senescence by chromatin-dependent alteration of S-phase progression," (in eng), Nat Commun, vol. 2, p. 2011; 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Alessio, D. N. Alessio, D. Aprile, S. Cappabianca, G. Peluso, G. Di Bernardo, and U. Galderisi, "Different Stages of Quiescence, Senescence, and Cell Stress Identified by Molecular Algorithm Based on the Expression of Ki67, RPS6, and Beta-Galactosidase Activity," (in eng), Int J Mol Sci, vol. 22, no. 2021; 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Piechota et al., "Is senescence-associated β-galactosidase a marker of neuronal senescence?," (in eng), Oncotarget, vol. 7, no. 49, pp. 8109. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Georgakopoulou et al., "Specific lipofuscin staining as a novel biomarker to detect replicative and stress-induced senescence. A method applicable in cryo-preserved and archival tissues," (in eng), Aging (Albany NY), vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 2013; -50. [CrossRef]

- A. Terman and U. T. Brunk, "Lipofuscin," (in eng), Int J Biochem Cell Biol, vol. 36, no. 8, pp. 1400; -4. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Sparrow and M. Boulton, "RPE lipofuscin and its role in retinal pathobiology," (in eng), Exp Eye Res, vol. 80, no. 5, pp. 20 May; 05. [CrossRef]

- S. Ferreira-Gonzalez, D. S. Ferreira-Gonzalez, D. Rodrigo-Torres, V. L. Gadd, and S. J. Forbes, "Cellular Senescence in Liver Disease and Regeneration," (in eng), Semin Liver Dis, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 2021; -66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. M. Aird and R. Zhang, "Detection of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF)," (in eng), Methods Mol Biol, vol. 965, pp. 2013; -96. [CrossRef]

- F. d'Adda di Fagagna et al., "A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence," (in eng), Nature, vol. 426, no. 6963, pp. 2003; -8. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Acosta et al., "A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence," (in eng), Nat Cell Biol, vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 2013; -90. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Reid, G. M. V. Reid, G. Fredickson, and D. G. Hepatology, 2024; 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Yoon et al., "Formation of elongated giant mitochondria in DFO-induced cellular senescence: involvement of enhanced fusion process through modulation of Fis1," (in eng), J Cell Physiol, vol. 209, no. 2, pp. 2006; -80. [CrossRef]

- S. Yamauchi et al., "Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation drives senescence," (in eng), Sci Adv, vol. 10, no. 43, p. 5887. [CrossRef]

- V. Gorgoulis et al., "Cellular Senescence: Defining a Path Forward," (in eng), Cell, vol. 179, no. 4, pp. 2019; 31. [CrossRef]

- N. Malaquin, A. N. Malaquin, A. Martinez, and F. Rodier, "Keeping the senescence secretome under control: Molecular reins on the senescence-associated secretory phenotype," (in eng), Exp Gerontol, vol. 82, pp. 2016; -49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. L. Dempsey, G. N. J. L. Dempsey, G. N. Ioannou, and R. M. Carr, "Mechanisms of Lipid Droplet Accumulation in Steatotic Liver Diseases," (in eng), Semin Liver Dis, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Terlecki-Zaniewicz et al., "Small extracellular vesicles and their miRNA cargo are anti-apoptotic members of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype," (in eng), Aging (Albany NY), vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 19 May 1103. [CrossRef]

- H. Okawa, Y. H. Okawa, Y. Tanaka, and A. Takahashi, "Network of extracellular vesicles surrounding senescent cells," (in eng), Arch Biochem Biophys, vol. 754, p. 1099; 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. P. Coppé, P. Y. J. P. Coppé, P. Y. Desprez, A. Krtolica, and J. Campisi, "The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression," (in eng), Annu Rev Pathol, vol. 5, pp. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Oguma et al., "Meta-analysis of senescent cell secretomes to identify common and specific features of the different senescent phenotypes: a tool for developing new senotherapeutics," (in eng), Cell Commun Signal, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 2023; 28. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liao, H. L. Z. Liao, H. L. Yeo, S. W. Wong, and Y. Zhao, "Cellular Senescence: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential," (in eng), Biomedicines, vol. 9, no. 2021; 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Shimi et al., "The role of nuclear lamin B1 in cell proliferation and senescence," (in eng), Genes Dev, vol. 25, no. 24, pp. 2579; -93. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumari and P. Jat, "Mechanisms of Cellular Senescence: Cell Cycle Arrest and Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype," (in eng), Front Cell Dev Biol, vol. 9, p. 64 5593, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Tabata et al., "NFκB dynamics-dependent epigenetic changes modulate inflammatory gene expression and induce cellular senescence," (in eng), FEBS J, vol. 291, no. 22, pp. 4951. [CrossRef]

- N. Herranz et al., "mTOR regulates MAPKAPK2 translation to control the senescence-associated secretory phenotype," (in eng), Nat Cell Biol, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 1205; -17. [CrossRef]

- N. Basisty et al., "A proteomic atlas of senescence-associated secretomes for aging biomarker development," (in eng), PLoS Biol, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 3000. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Beauséjour et al., "Reversal of human cellular senescence: roles of the p53 and p16 pathways," (in eng), EMBO J, vol. 22, no. 16, pp. 4212; -22. [CrossRef]

- S. Hamsanathan and A. U. Gurkar, "Lipids as Regulators of Cellular Senescence," (in eng), Front Physiol, vol. 13, p. 79 6850, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. H. Bent, L. A. E. H. Bent, L. A. Gilbert, and M. T. Hemann, "A senescence secretory switch mediated by PI3K/AKT/mTOR activation controls chemoprotective endothelial secretory responses," (in eng), Genes Dev, vol. 30, no. 16, pp. 1811; -21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. A. Saxton and D. M. Sabatini, "mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease," (in eng), Cell, vol. 168, no. 6, pp. 2017; 03. [CrossRef]

- Biran, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , "Quantitative identification of senescent cells in aging and disease," (in eng), Aging Cell, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Itahana, Y. K. Itahana, Y. Itahana, and G. P. Dimri, "Colorimetric detection of senescence-associated β galactosidase," (in eng), Methods Mol Biol, vol. 965, pp. 2013; -56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T.-W. Kang, "Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development," vol. 479, Woller Norman Ed., ed. Nature.

- YYY. Millner and G. E. Atilla-Gokcumen, "Lipid Players of Cellular Senescence," (in eng), Metabolites, vol. 10, no. 2020; 9. [CrossRef]

- YYY. C. Flor, D. Wolfgeher, D. Wu, and S. J. Kron, "A signature of enhanced lipid metabolism, lipid peroxidation and aldehyde stress in therapy-induced senescence," (in eng), Cell Death Discov, vol. 3, p. 1 7075, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zeng, Y. Q. Zeng, Y. Gong, N. Zhu, Y. Shi, C. Zhang, and L. Qin, "Lipids and lipid metabolism in cellular senescence: Emerging targets for age-related diseases," (in eng), Ageing Res Rev, vol. 97, p. 1022; 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Quintana-Castro et al., "Cd36 gene expression in adipose and hepatic tissue mediates the lipids accumulation in liver of obese rats with sucrose-induced hepatic steatosis," (in eng), Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat, vol. 147, p. 1064; 04. [CrossRef]

- M. Chong et al., "CD36 initiates the secretory phenotype during the establishment of cellular senescence," (in eng), EMBO Rep, vol. 19, no. 2018; 6. [CrossRef]

- J. Fafián-Labora et al., "FASN activity is important for the initial stages of the induction of senescence," (in eng), Cell Death Dis, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 2019; 08. [CrossRef]

- M. Danielli, L. Perne, E. Jarc Jovičić, and T. Petan, "Lipid droplets and polyunsaturated fatty acid trafficking: Balancing life and death," (in eng), Front Cell Dev Biol, vol. 11, p. 110 4725, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Fan and Y. Tan, "Lipid Droplet-Mitochondria Contacts in Health and Disease," (in eng), Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 2024; 13. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Angara, M. F. Sladek, and S. D. Gilk, "ER-LD Membrane Contact Sites: A Budding Area in the Pathogen Survival Strategy," (in eng), Contact (Thousand Oaks), vol. 7, p. 2515256424130 4196, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Xu, X. S. Xu, X. Zhang, and P. Liu, "Lipid droplet proteins and metabolic diseases," (in eng), Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, vol. 1864, no. 5 Pt B, pp. 20 May 1968; 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Jiang et al., "Analysis of p53 transactivation domain mutants reveals Acad11 as a metabolic target important for p53 pro-survival function," (in eng), Cell Rep, vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 1096. [CrossRef]

- P. V. S. Vasileiou et al., "Mitochondrial Homeostasis and Cellular Senescence," (in eng), Cells, vol. 8, no. 2019; 7. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Vizioli et al., "Mitochondria-to-nucleus retrograde signaling drives formation of cytoplasmic chromatin and inflammation in senescence," (in eng), Genes Dev, vol. 34, no. 5-6, pp. 2020; 01. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al., "GSK3 inhibitor ameliorates steatosis through the modulation of mitochondrial dysfunction in hepatocytes of obese patients," (in eng), iScience, vol. 24, no. 3, p. 1021; 49. [CrossRef]

- S. Tandra et al., "Presence and significance of microvesicular steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease," (in eng), J Hepatol, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Germano et al., "Microvesicular Steatosis in Individuals with Obesity: a Histological Marker of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Severity," (in eng), Obes Surg, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Fromenty, A. B. Fromenty, A. Berson, and D. Pessayre, "Microvesicular steatosis and steatohepatitis: role of mitochondrial dysfunction and lipid peroxidation," (in eng), J Hepatol, vol. 26 Suppl 1, pp. 1997; -22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Chandrasekaran, S. P. Chandrasekaran, S. Weiskirchen, and R. Weiskirchen, "Perilipins: A family of five fat-droplet storing proteins that play a significant role in fat homeostasis," (in eng), J Cell Biochem, vol. 125, no. 6, p. 3057; e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. E. Libby, E. A. E. Libby, E. Bales, D. J. Orlicky, and J. L. McManaman, "Perilipin-2 Deletion Impairs Hepatic Lipid Accumulation by Interfering with Sterol Regulatory Element-binding Protein (SREBP) Activation and Altering the Hepatic Lipidome," (in eng), J Biol Chem, vol. 291, no. 46, pp. 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. K. Straub et al., "Adipophilin/perilipin-2 as a lipid droplet-specific marker for metabolically active cells and diseases associated with metabolic dysregulation," (in eng), Histopathology, vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 2013; -31. [CrossRef]

- J. L. McManaman et al., "Perilipin-2-null mice are protected against diet-induced obesity, adipose inflammation, and fatty liver disease," (in eng), J Lipid Res, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 20 May 1346; -59. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Carr and R. S. Ahima, "Pathophysiology of lipid droplet proteins in liver diseases," (in eng), Exp Cell Res, vol. 340, no. 2, pp. 2016; -92. [CrossRef]

- Chiariello, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , "Downregulation of PLIN2 in human dermal fibroblasts impairs mitochondrial function in an age-dependent fashion and induces cell senescence via GDF15," (in eng), Aging Cell, vol. 23, no. 5, p. 20 May 1411; e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. M. Pawella et al., "Perilipin discerns chronic from acute hepatocellular steatosis," (in eng), J Hepatol, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 2014; -42. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Ma et al., "Disruption of Plin5 degradation by CMA causes lipid homeostasis imbalance in NAFLD," (in eng), Liver Int, vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 2427. [CrossRef]

- C. Wang et al., "Perilipin 5 improves hepatic lipotoxicity by inhibiting lipolysis," (in eng), Hepatology, vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 2015; -82. [CrossRef]

- M. Cinato et al., "Role of Perilipins in Oxidative Stress-Implications for Cardiovascular Disease," (in eng), Antioxidants (Basel), vol. 13, no. 2024; 2. [CrossRef]

- M. Pawlak, P. M. Pawlak, P. Lefebvre, and B. Staels, "Molecular mechanism of PPARα action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease," (in eng), J Hepatol, vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 2015; -33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Lin, Y. Wang, and P. F. Li, "PPARα: An emerging target of metabolic syndrome, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases," (in eng), Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), vol. 13, p. 107 4911, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Zhang et al., "Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha inhibits hepatocarcinogenesis through mediating NF-κB signaling pathway," (in eng), Oncotarget, vol. 5, no. 18, pp. 8330; -40. [CrossRef]

- S. Todisco et al., "PPAR Alpha as a Metabolic Modulator of the Liver: Role in the Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH)," (in eng), Biology (Basel), vol. 11, no. 23 May 2022; 5. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Prescott, J. P. J. A. Prescott, J. P. Mitchell, and S. J. Cook, "Inhibitory feedback control of NF-κB signalling in health and disease," (in eng), Biochem J, vol. 478, no. 13, pp. 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Targher, C. D. G. Targher, C. D. Byrne, and H. Tilg, "MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications," (in eng), Gut, vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 2024; 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Liu, L. T. Liu, L. Zhang, D. Joo, and S. C. Sun, "NF-κB signaling in inflammation," (in eng), Signal Transduct Target Ther, vol. 2, pp. 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. P. Glauert et al., "The Role of NF-kappaB in PPARalpha-Mediated Hepatocarcinogenesis," (in eng), PPAR Res, vol. 2008, p. 28 6249, 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Lee et al., "Hepatic Mitochondrial Defects in a Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Mouse Model Are Associated with Increased Degradation of Oxidative Phosphorylation Subunits," (in eng), Mol Cell Proteomics, vol. 17, no. 12, pp. 2371. [CrossRef]

- M. Longo, M. M. Longo, M. Meroni, E. Paolini, C. Macchi, and P. Dongiovanni, "Mitochondrial dynamics and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): new perspectives for a fairy-tale ending?," (in eng), Metabolism, vol. 117, p. 1547; 08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Fromenty and M. Roden, "Mitochondrial alterations in fatty liver diseases," (in eng), J Hepatol, vol. 78, no. 2, pp. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Deleye et al., "CDKN2A/p16INK4a suppresses hepatic fatty acid oxidation through the AMPKα2-SIRT1-PPARα signaling pathway," (in eng), J Biol Chem, vol. 295, no. 50, pp. 1731. [CrossRef]

- K. Evangelou et al., "Cellular senescence and cardiovascular diseases: moving to the "heart" of the problem," (in eng), Physiol Rev, vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 2023; 01. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Aravinthan and G. J. M. Alexander, "Senescence in chronic liver disease: Is the future in aging?," (in eng), J Hepatol, vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Kudlova, J. B. N. Kudlova, J. B. De Sanctis, and M. Hajduch, "Cellular Senescence: Molecular Targets, Biomarkers, and Senolytic Drugs," (in eng), Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 2022; 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. S. Meijnikman, H. A. S. Meijnikman, H. Herrema, T. P. M. Scheithauer, J. Kroon, M. Nieuwdorp, and A. K. Groen, "Evaluating causality of cellular senescence in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease," (in eng), JHEP Rep, vol. 3, no. 4, p. 1003; 01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Aravinthan et al., "Gene polymorphisms of cellular senescence marker p21 and disease progression in non-alcohol-related fatty liver disease," (in eng), Cell Cycle, vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 1489; -94. [CrossRef]

- M. Ogrodnik et al., "Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis," (in eng), Nat Commun, vol. 8, p. 1569; 1. [CrossRef]

- A. Aravinthan et al., "Hepatocyte senescence predicts progression in non-alcohol-related fatty liver disease," (in eng), J Hepatol, vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 2013; -56. [CrossRef]

- S. Francque et al., "PPARα gene expression correlates with severity and histological treatment response in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis," (in eng), J Hepatol, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 2015; -73. [CrossRef]

- C. Kiourtis et al., "Hepatocellular senescence induces multi-organ senescence and dysfunction via TGFβ," (in eng), Nat Cell Biol, vol. 26, no. 12, pp. 2075. [CrossRef]

- M. Hoare and M. Narita, "Transmitting senescence to the cell neighbourhood," (in eng), Nat Cell Biol, vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 2013; -9. [CrossRef]

- A. Vouilloz et al., "Impaired unsaturated fatty acid elongation alters mitochondrial function and accelerates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis progression," (in eng), Metabolism, vol. 162, p. 1560; 51. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Koenig, A. A. B. Koenig, A. Tan, H. Abdelaal, F. Monge, Z. M. Younossi, and Z. D. Goodman, "Review article: Hepatic steatosis and its associations with acute and chronic liver diseases," (in eng), Aliment Pharmacol Ther, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. Toussaint et al., "Stress-induced premature senescence or stress-induced senescence-like phenotype: one in vivo reality, two possible definitions?," (in eng), ScientificWorldJournal, vol. 2, pp. 2002; -47. [CrossRef]

- T. von Zglinicki, "Oxidative stress shortens telomeres," (in eng), Trends Biochem Sci, vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 2002; -44. [CrossRef]

- V. Paradis et al., "Replicative senescence in normal liver, chronic hepatitis C, and hepatocellular carcinomas," (in eng), Hum Pathol, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 2001; -32. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).