Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Common Solid Lubricants Used in AgMCs and AgMNCs

4. Preparation of Powder Mixtures and Sintered AgMNCs

4.1. Common Preparation Methods of AgMNC Powder Mixtures

4.1.1. Mechanical Methods for Preparation of AgMNC Powders

Representative Examples of AgMNC Powders Fabricated by Mechanical Methods

4.1.2. Chemical Methods for Preparation of AgMNC Powders

Representative Examples of AgMNC Powders Fabricated by Chemical Methods

4.2. Common Preparation Methods of Sintered AgMNCs

Representative Examples of Sintered AgMNCs Fabricated by Conventional PM Route

Representative Examples of Sintered AgMNCs Fabricated by Hot Pressing Sintering

Representative Examples of Sintered AgMNCs Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering

Representative Examples of Sintered AgMNCs Fabricated by SPS and HPS

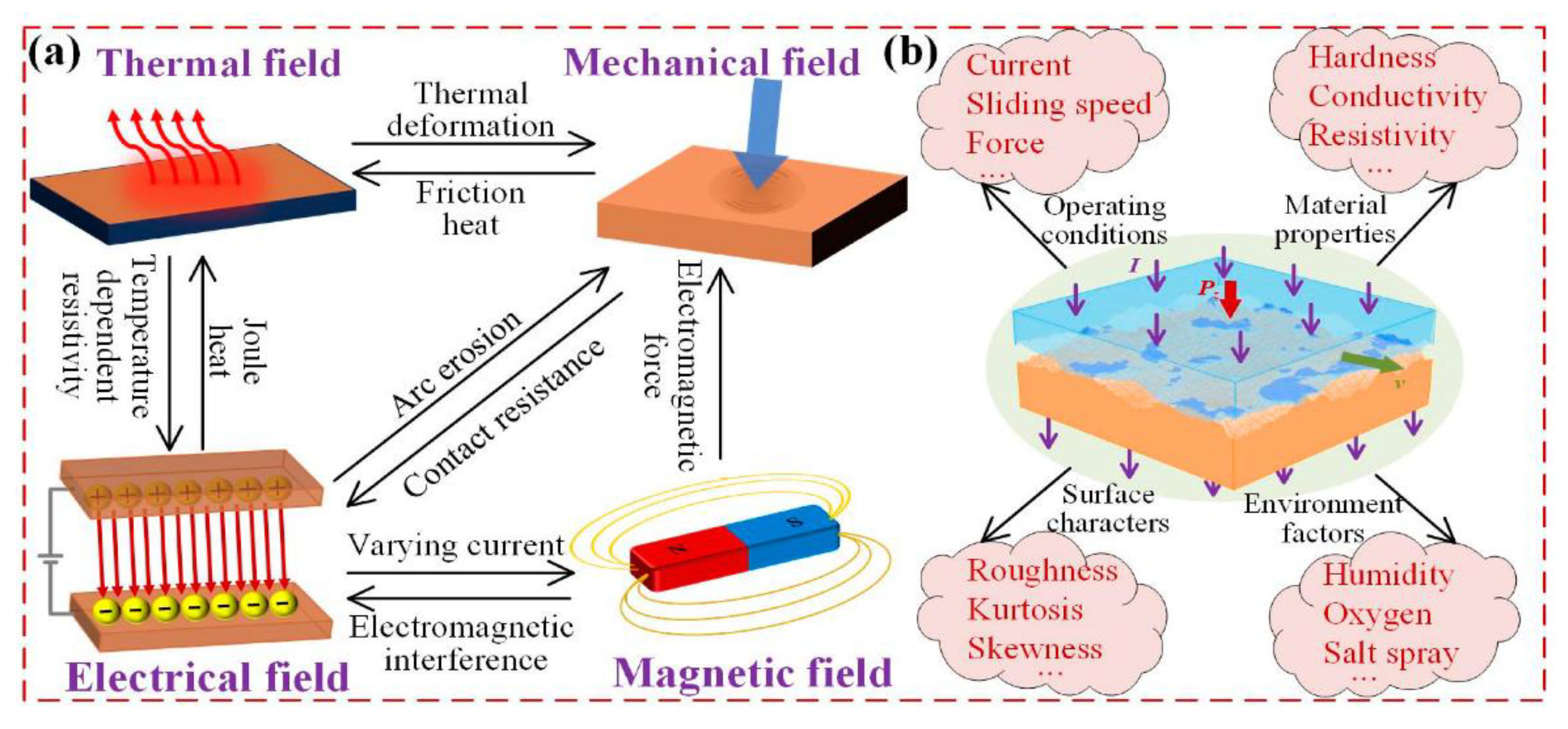

5. Investigation of Tribological Performance of Sliding AgMNCs

5.1. Tribological and Sliding Electrical Contact (SEC) Testing of Sintered AgMNCs

5.2. Lubricating Film Evolution and Friction Model

5.3. Assessment of Lubricating Film Coverage by X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

6. Key Findings on the Tribological Behavior of Sintered AgMNCs

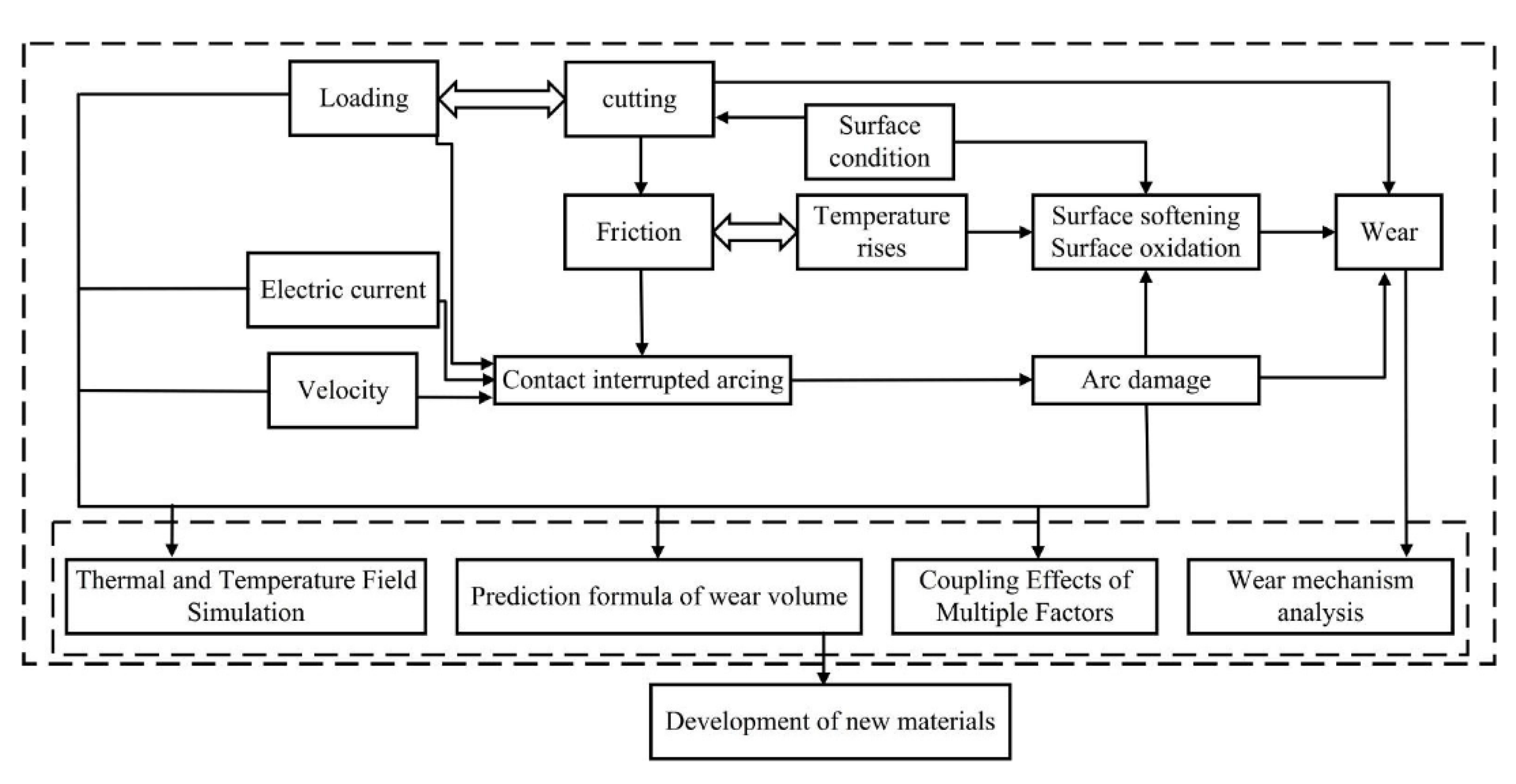

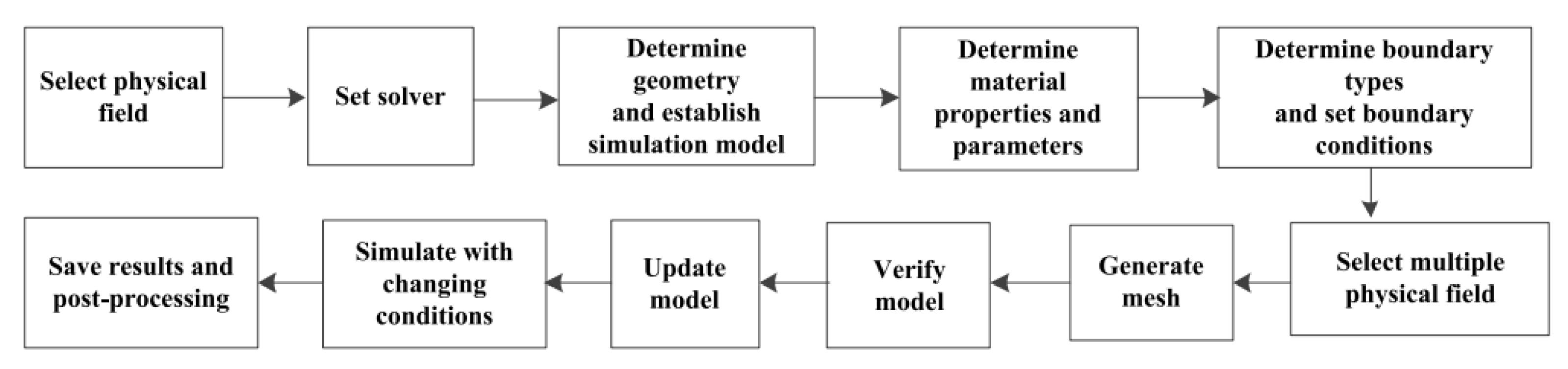

7. Numerical Simulation of Current-Carrying Friction and Wear in AgMNC Electrical Contacts

8. Gaps and Future Research Directions

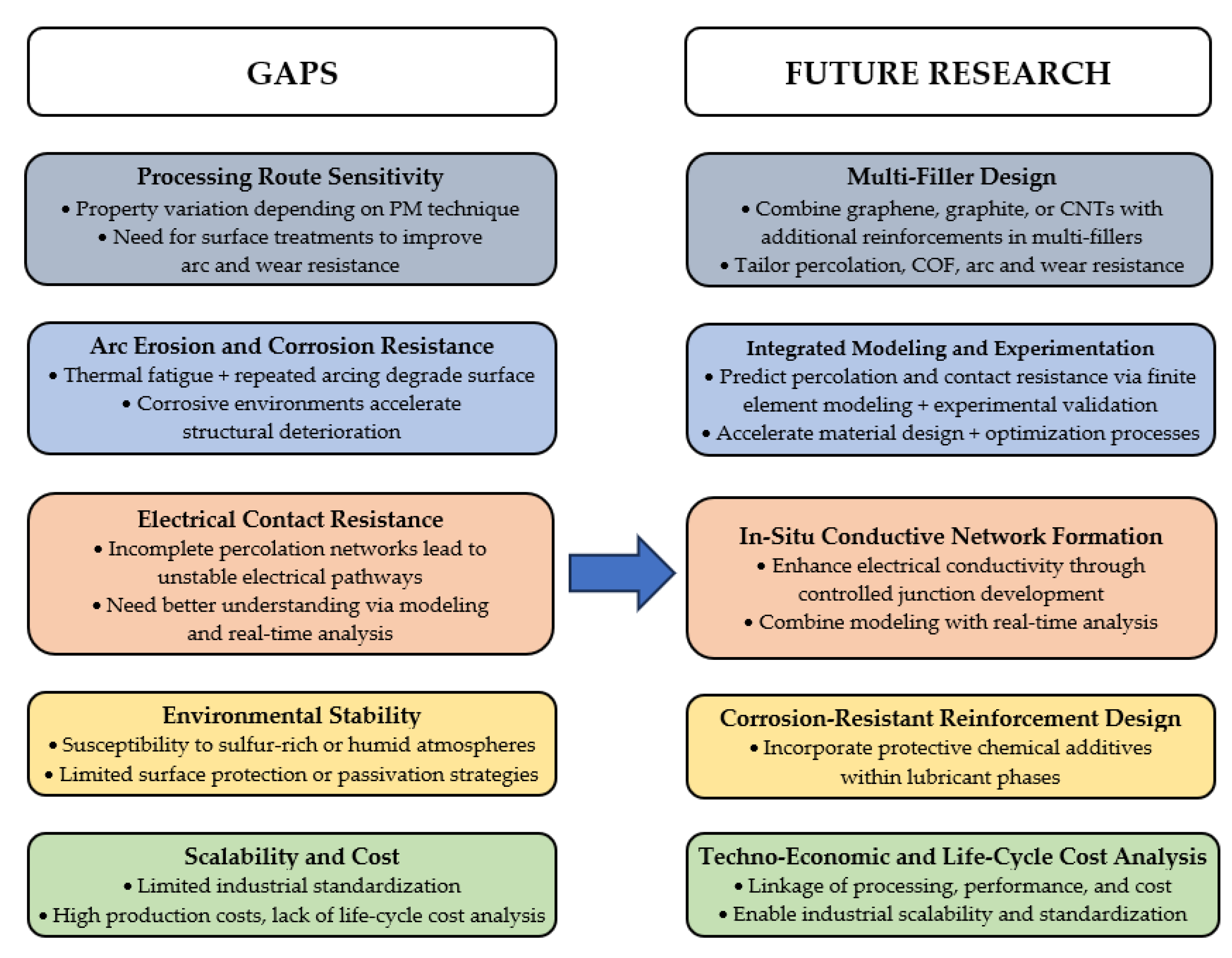

- i)

- Dispersion and interfacial compatibility of solid lubricants within Ag matrices are critical for reliable tribological and electrical performance. Uniform distribution of the reinforcing phases prevent local stress concentrations and irregular current paths that can reduce wear resistance and conductivity [6,22]. Strong interfacial bonding with the Ag matrix further enhances composite stability and load-transfer efficiency [6,43,79].

- ii)

- Processing route significantly affects the properties and performance of sliding Ag-based NCs and MCs. Fabrication methods, such as conventional or advanced powder metallurgy (PM), determine the formation of conductive networks and microstructure, which in turn influence electrical and tribological behavior [6,18,29,41,57,60]. Similar process-structure-property relationships observed in sliding Cu-based composites suggest analogous mechanisms in sliding Ag-based composites [80,81,82].

- iii)

- Arc erosion and corrosion resistance are major challenges for Ag-based contact materials. Reinforcements must withstand repeated arcing and high thermal loads while preserving electrical conductivity [83,84,85]. Optimized sliding friction treatments (SFTs) and protective coatings can enhance arc erosion resistance, showing that a well-consolidated microstructure supports long-term stability [14,26,86]. Corrosion resistance is also critical, as electrochemical reactions can accelerate surface degradation and weaken the structure during operation [87].

- iv)

- Electrical contact resistance is a key performance metric, largely determined by the continuity of conductive networks formed by fillers such as graphene, graphite, or CNTs within the Ag matrix [79]. These additives enhance electron mobility, reducing contact resistance and improving overall electrical performance. Finite element modeling (FEM) has provided insights into contact-resistance evolution under operational stresses, guiding the design of next-generation Ag-based NCs and MCs [70,79].

- v)

- Environmental stability is a critical factor for sliding Ag-based composites, as silver is susceptible to corrosion and sulfur-induced degradation in harsh or reactive atmospheres. Surface protection strategies, involving corrosion-resistant coatings, optimizing surface chemistry, or alloying the Ag matrix with stabilizing elements can enhance corrosion resistance and ensure reliable electrical and tribological performance [87].

- vi)

- Economic feasibility and scalability are key goals for advancing Ag-based composites. Transition from lab-scale synthesis to industrial production requires cost-effective, reproducible methods that ensure long-term reliability. Although some fabrication methods show promise, optimizing processing parameters and establishing standardized protocols are needed for reliable large-scale production of AgMNCs [58].

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | two dimensional |

| AA | ascorbic acid |

| BPR | ball-to-powder ratio |

| BLG | bilayer graphene |

| BSE | backscattered electron |

| CNTs | carbon nanotubes |

| COF | coefficient of friction |

| CR | cooling rate |

| CEP | conventional electroless plating |

| CB | counterbody |

| CRM | critical raw material |

| CCFW | current-carrying friction and wear |

| DC | during current |

| DEM | discrete element method |

| DT | dwell time |

| ECMs | electrical contact materials |

| ECR | electrical contact resistance |

| EDS | energy dispersive spectroscopy |

| EPUSA | electroless plating assisted by ultrasonic spray atomization |

| FEM | finite element modeling |

| FG | flake graphite |

| GNs | graphene nanosheets |

| GO | graphene oxide |

| HR | heating rate |

| HEBM | high-energy ball milling |

| HRTEM | high resolution transmission electron microscopy |

| HPS | hot pressing sintering |

| Tm | melting temperature |

| MMCs | metal matrix composites |

| MMNCs | metal matrix nanocomposites |

| MCs | microcomposites |

| MLM | molecular-level mixing |

| MWCNTs | multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| NCs | nanocomposites |

| NPs | nanoparticles |

| NR | not reported |

| POD | pin-on-disc |

| PBM | planetary ball milling |

| PM | powder metallurgy |

| Pp | pressing pressure |

| rGO | reduced graphene oxide |

| RD | relative density |

| RSM | response surface method |

| RT | room temperature |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SAED | selected area diffraction pattern |

| AgMCs | silver matrix composites |

| AgMNCs | silver matrix nanocomposites |

| AgNPs | silver nanoparticles |

| SLG | single layer graphene |

| SWCNTs | single-walled carbon nanotubes |

| Ts | sintering temperature |

| SECs | sliding electrical contacts |

| SFTs | sliding friction treatments |

| SDS | sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| SLS | sodium lauryl sulfate |

| SBM | solution ball milling |

| SPS | spark plasma sintering |

| SG | spherical graphite |

| SRM | strategic raw material |

| TD | theoretical density |

| TMDs | transition metal dichalcogenides |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| TTM | two-temperature method |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Varol, T.; Güler, O. Metal-Based Electrical Contact Materials. In Advanced Composites; Ikhmayies, S.J., Ed.; Advances in Material Research and Technology; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.-L.; Xiao, J.-K.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.-Z.; Chen, J.; Li, A.-K.; Zhang, C. Tribological Property of AgNi-CNTs Composites under Electric Current. Wear 2025, 564–565, 205712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, M.V.; Barbu, A. Graphene and Its Derivative Reinforced Tungsten–Copper Composites for Electrical Contact Applications: A Review. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2022, 41, (15–16). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, M.V.; Lucaci, M.; Tsakiris, V.; Brătulescu, A.; Cîrstea, C.D.; Marin, M.; Pătroi, D.; Mitrea, S.; Marinescu, V.; Grigore, F.; et al. Development and Investigation of Tungsten Copper Sintered Parts for Using in Medium and High Voltage Switching Devices. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 209, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Qin, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Z. What Are the Progresses and Challenges, from the Electrical Properties of Current-Carrying Friction System to Tribological Performance, for a Stable Current-Carrying Interface? J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Yu, S.; Yang, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L. Tribological Behavior and Microstructural Evolution of Lubricating Film of Silver Matrix Self-Lubricating Nanocomposite. Friction 2021, 9, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, X.; Li, F.; Chen, W.; Li, H.; Yao, C. Influence of Normal Load, Electric Current and Sliding Speed on Tribological Performance of Electrical Contact Interface. Microelectron. Reliab. 2023, 142, 114929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, T.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhou, C.; Ma, M.; Zheng, Q. Wear-Free Sliding Electrical Contacts with Ultralow Electrical Resistivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahobetskyi, V. Durability and Wear Resistance of Sliding Electric Contacts in Electric Transport. PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY 2024, 1, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Hu, Y.; Cai, S.; Yu, J. How to Improve the Sliding Electrical Contact and Tribological Performance of Contacts by Nickel Coating. Coatings 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Yu, Z.; Song, A.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, H.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, W. Intermittent Failure Mechanism and Stabilization of Microscale Electrical Contact. Friction 2023, 11, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.; Menezes, P.L. Self-Lubricating Materials for Extreme Condition Applications. Materials 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhong, M.; Xu, W.; Yi, M.; Wu, H.; Huang, M. The Influence of Micron-Sized SiC and Carbon Nanotubes on Tribological Performance of Cu-Matrix Self-Lubrication Composites. Mater. Charact. 2025, 221, 114753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

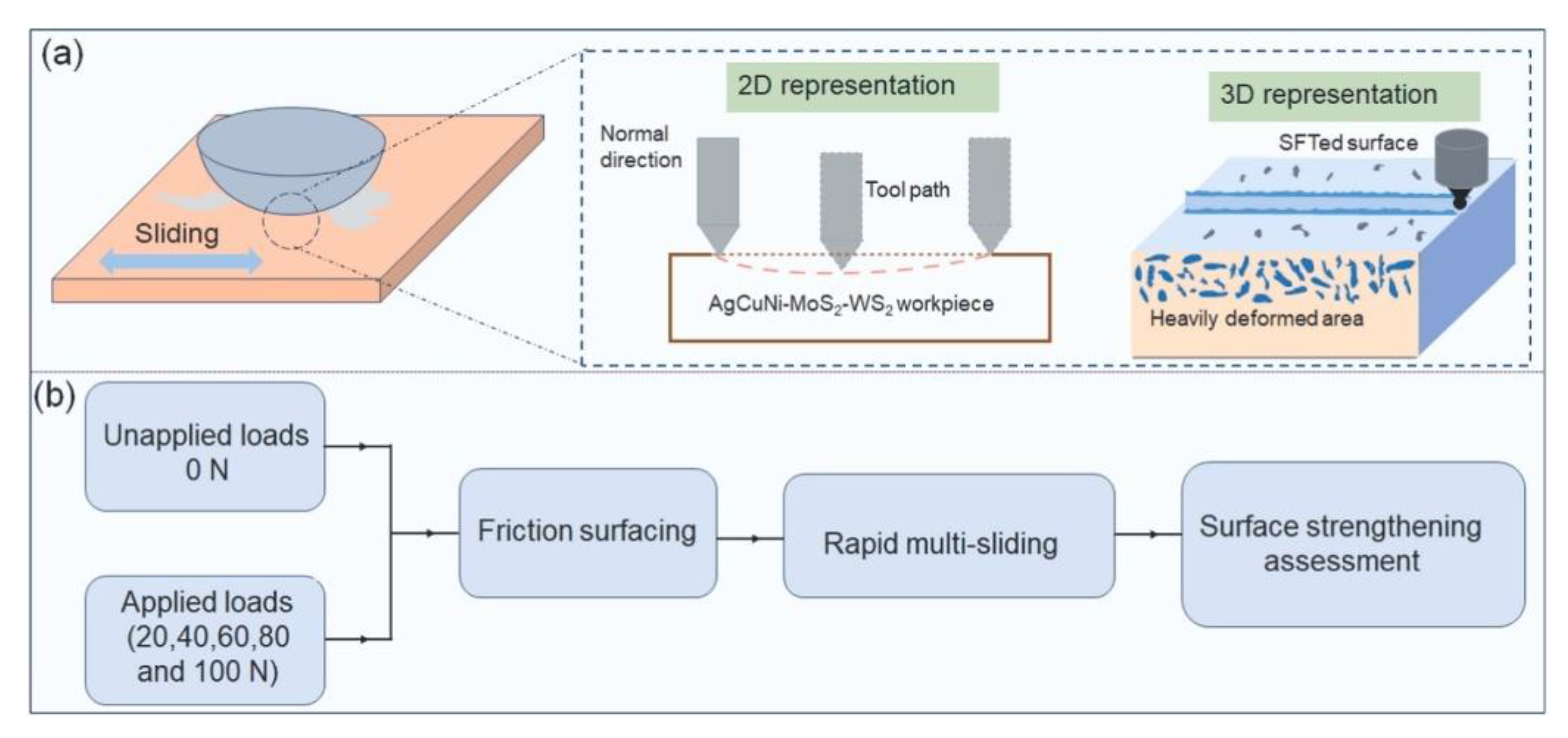

- Zhu, X.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Luo, B.; Kang, X.; Liu, Y. Sliding Friction-Induced Surface Reinforcement in AgCuNi–WS2–MoS2 Composites: Exploring Friction Performance Enhancements. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 34, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freschi, M.; Arrigoni, A.; Haiko, O.; Andena, L.; Kömi, J.; Castiglioni, C.; Dotelli, G. Physico-Mechanical Properties of Metal Matrix Self-Lubricating Composites Reinforced with Traditional and Nanometric Particles. Lubricants 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.-H.; Li, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Wang, Y.-M.; Wang, Y.-J. High-Temperature Solid Lubricants and Self-Lubricating Composites: A Critical Review. Lubricants 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Qian, Z. Effects of Environment on Dry Sliding Wear Behavior of Silver–Copper Based Composites Containing Tungsten Disulfide. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 2202–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L. Fabrication of Ag-WS2 Composites with Preferentially Oriented WS2 and its Anisotropic Tribology Behavior. Mater. Lett. 2020, 260, 126975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doutriaux, T.; Fouvry, S.; Larousse, S.; Isard, M.; Graton, O.; Isabel De Barros Bouchet, M. How Transfer Film Formation in Bronze/Silver-Graphite Sliding Contact Drives Its Electrical Performance. Wear 2025, 570, 205976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chika, O.U.; Kallon, D.V.V.; Aigbodion, V.S. Tribological Properties of CNTs-Reinforced Nano Composite Materials. Lubricants 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, H.; Sharma, V. Effect of Sintering on Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Carbon Nanotube Based Silver Nanocomposites. Indian J. Phys. 2015, 89, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, H.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, R.; Thakur, N. Facile Synthesis and Electrical Conductivity of Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Nanosilver Composite. Z. Für Naturforschung A 2012, 67, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoush, W.M.; Lim, B.K.; Nam, D.H.; Hong, S.H. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of CNT/Ag Nanocomposites Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2014, 9, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, F.; Poll, G. Investigations on Graphene Platelets as Dry Lubricant and as Grease Additive for Sliding Contacts and Rolling Bearing Application. Lubricants 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Bai, P.; Du, W.; Liu, B.; Pan, D.; Das, R.; Liu, C.; Guo, Z. An Overview of Graphene and Its Derivatives Reinforced Metal Matrix Composites: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Carbon 2020, 170, 302–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Xie, M.; Wang, H.; Bou-Saïd, B.; Liu, W. Recent Advances in Self-Lubricating Metal Matrix Nanocomposites Reinforced by Carbonous Materials: A Review. Nano Mater. Sci. 2024, 6, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, G.; Luo, J. Black Phosphorus as a New Lubricant. Friction 2018, 6, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

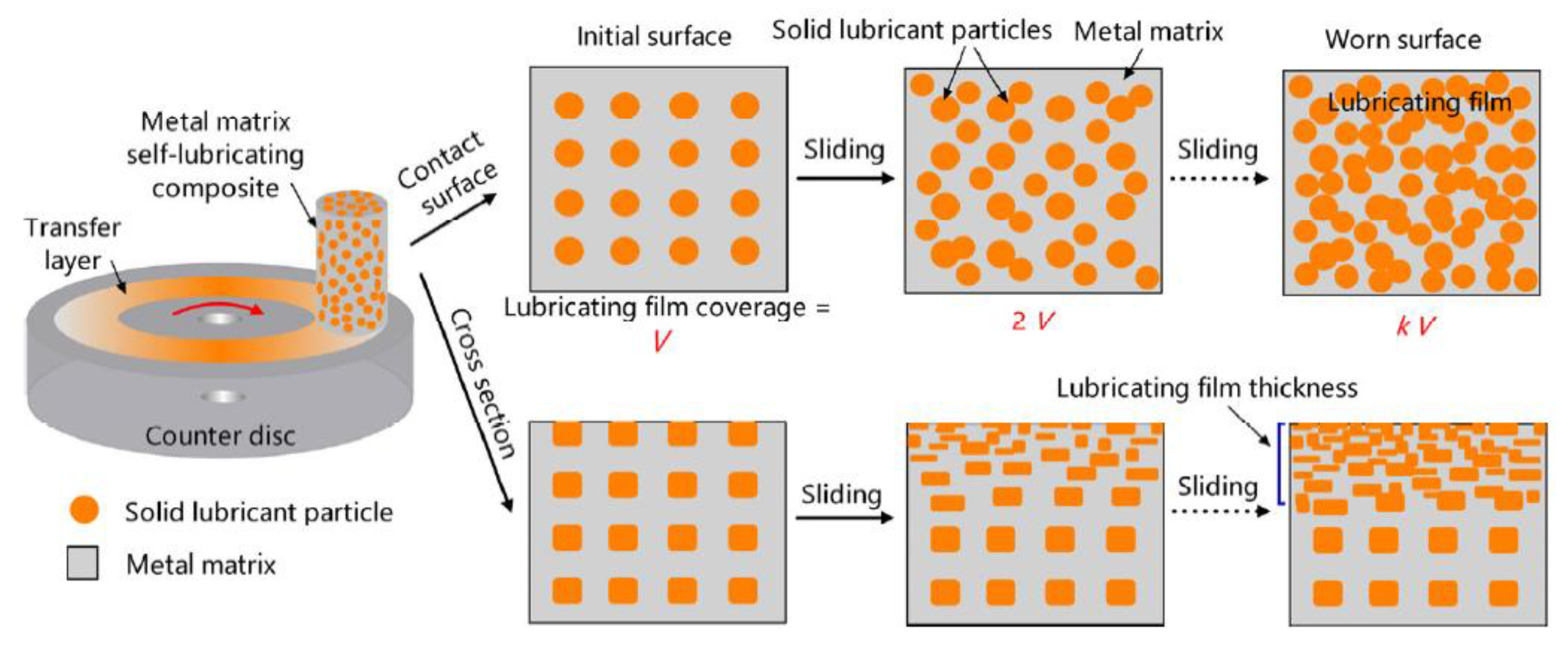

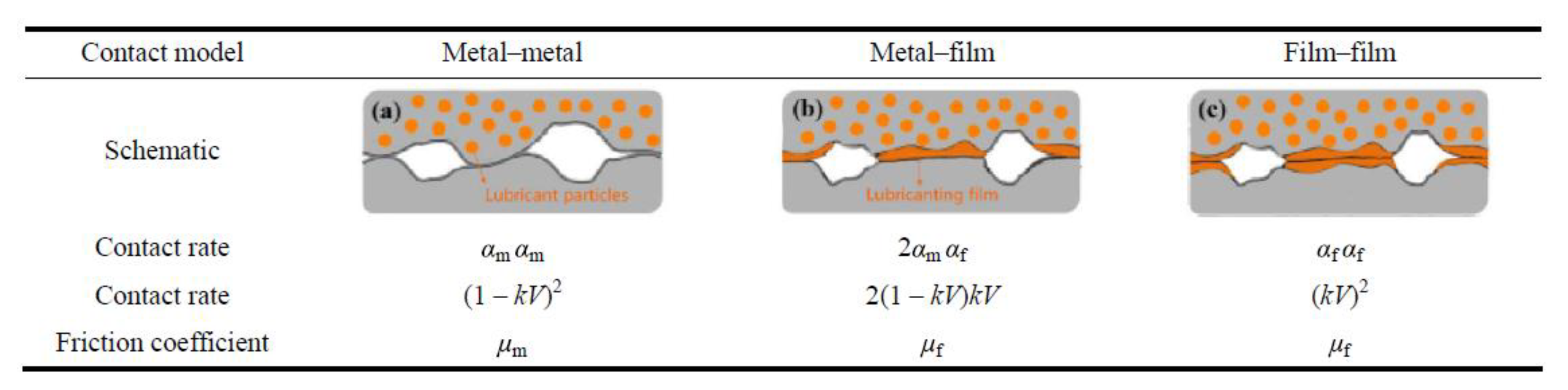

- Xiao, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C. Friction of Metal-Matrix Self-Lubricating Composites: Relationships among Lubricant Content, Lubricating Film Coverage, and Friction Coefficient. Friction 2020, 8, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L. Self-Lubricating and High Wear Resistance Mechanism of Silver Matrix Self-Lubricating Nanocomposite in High Vacuum. Vacuum 2020, 182, 109768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, D.; Singh, D.; Kumar Sharma, S. Thermal Characteristics and Tribological Performances of Solid Lubricants: A Mini Review. In Advances in Rheology of Materials; Dutta, A., Muhamad Ali, H., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M. Microstructure and Properties of Silver Matrix Composites Reinforced with Ag-Doped Graphene. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 215, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, H.; Kumari, S.; Khatri, O.P.; Tyagi, R. Copper Matrix Composites Reinforced by rGO-MoS2 Hybrid: Strengthening Effect to Enhancement of Tribological Properties. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 173, 106931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, K.P.; Da Costa Gonçalves, P.; Consoni, D.R.; Dias, M.V.G.; De Lima, G.A.; De Mello, J.D.B.; Klein, A.N. Metallurgical Aspects of Self-Lubricating Composites Containing Graphite and MoS2. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2017, 26, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloch, K.T.; Kozak, P.; Mlyniec, A. A Review and Perspectives on Predicting the Performance and Durability of Electrical Contacts in Automotive Applications. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 121, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalin, M.; Poljanec, D. Influence of the Contact Parameters and Several Graphite Materials on the Tribological Behaviour of Graphite/Copper Two-Disc Electrical Contacts. Tribol. Int. 2018, 126, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Study on the Critical Raw Materials for the EU 2023: Final Report; Publications Office: LU, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Markets and Markets. Metal Matrix Composite Market - Global Forecast to 2025; CH 5237; 2020. Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/metal-matrix-composite-market-91778299.html (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Chromik, R.R. Tribology of Self-Lubricating Metal Matrix Composites. In Self-Lubricating Composites; Menezes, P.L., Rohatgi, P.K., Omrani, E., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedayati, H.; Mofidi, A.; Al-Fadhli, A.; Aramesh, M. Solid Lubricants Used in Extreme Conditions Experienced in Machining: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Developments and Applications. Lubricants 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Feng, Y.; Shao, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, N. Friction and Wear Behaviors of Ag/MoS2/G Composite in Different Atmospheres and at Different Temperatures. Tribol. Lett. 2012, 47, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

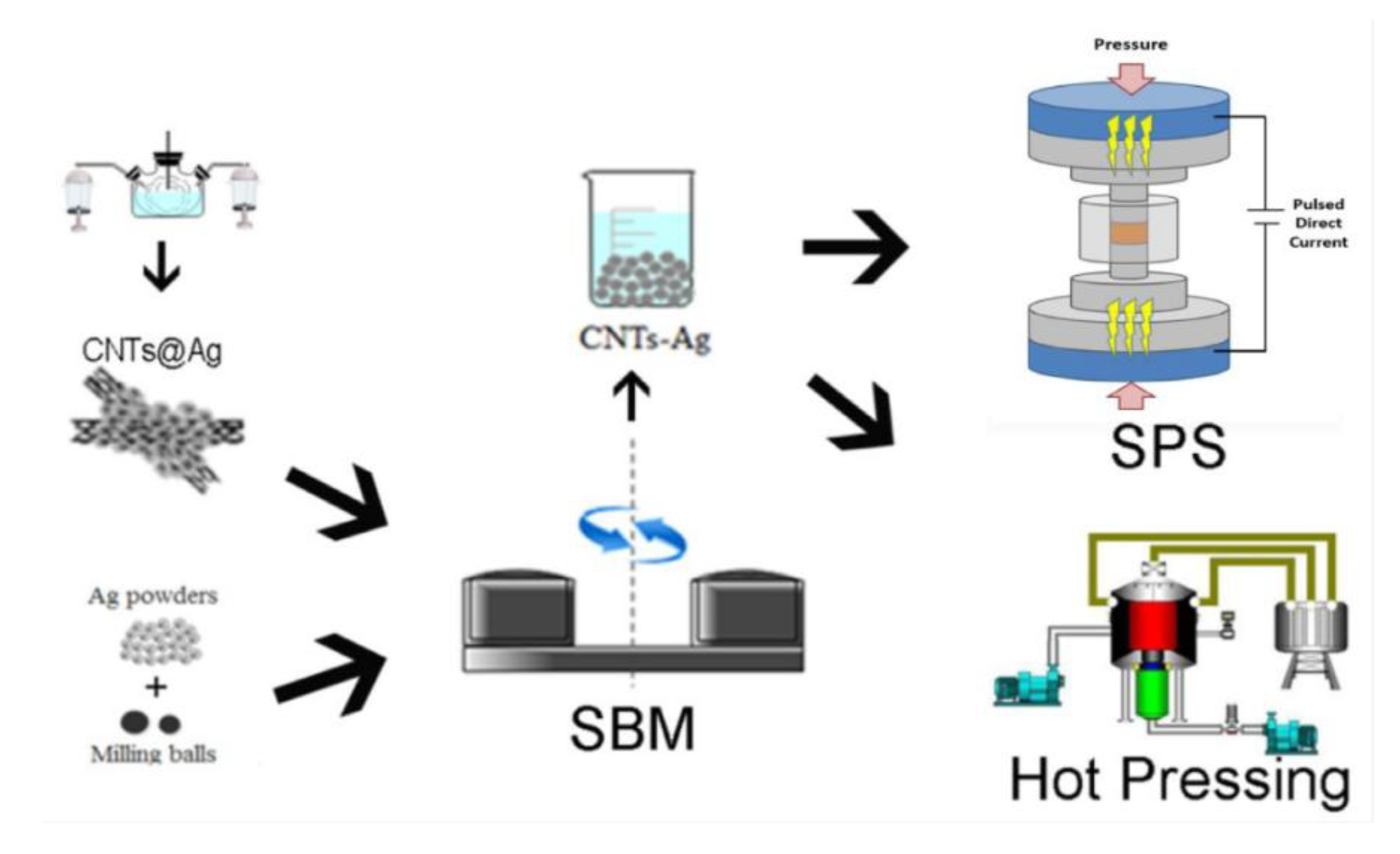

- Zhao, Q.; Tan, S.; Xie, M.; Liu, Y.; Yi, J. A Study on the CNTs-Ag Composites Prepared Based on Spark Plasma Sintering and Improved Electroless Plating Assisted by Ultrasonic Spray Atomization. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 737, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Ma, J.; Gan, X.; Tao, J.; Xie, M.; Yi, J.; Liu, Y. A Comparison Study of Ag Composites Prepared by Spark Plasma Sintering and Hot Pressing with Silver-Coated CNTs as the Reinforcements. Materials 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Kang, X. Frictional Behavior and Wear Mechanisms of Ag/MoS2/WS2 Composite under Reciprocating Microscale Sliding. Tribol. Int. 2023, 185, 108510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.M.; Wong, C.H.; He, X.Q.; Tan, M.J. Thermal Stability of Single and Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; Li, S.; Lin, S. Influence of Graphite Content on Sliding Wear Characteristics of CNTs-Ag-G Electrical Contact Materials. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2009, 19, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, M.; Jin, L.; Li, L.; Mo, Y.; Su, G.; Li, X.; Zhu, H.; Tian, Y. Recent Advances in Friction and Lubrication of Graphene and Other 2D Materials: Mechanisms and Applications. Friction 2019, 7, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, A.; Yang, Z.; Yu, L.; Kavaliova, I.N.; Prozhega, M.V.; Hao, Y. MoS2 Nanoadditives for Lubrication: Morphology, Surface Chemistry, and Mechanisms. Tribol. Int. 2026, 214, 111151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.L.; Gray, J.A.T. Prandtl-Tomlinson Model: A Simple Model Which Made History. In The History of Theoretical, Material and Computational Mechanics - Mathematics Meets Mechanics and Engineering; Stein, E., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Applied Mathematics and Mechanics; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattari Baboukani, B.; Nalam, P.C.; Komvopoulos, K. Nanoscale Friction Characteristics of Layered-Structure Materials in Dry and Wet Environments. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 8, 965877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floría, L.M.; Baesens, C.; Gómez-Gardeñes, J. The Frenkel–Kontorova Model. In Dynamics of Coupled Map Lattices and of Related Spatially Extended Systems; Lecture Notes in Physics; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnott, S. Theory of Atomic-Scale Friction. In Handbook of Nanostructured Materials and Nanotechnology; Elsevier, 2000; Vol. 2, pp 571–618. [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Laigle, C.; Gatumel, C.; Berthiaux, H. Mixing Dynamics for Easy Flowing Powders in a Lab Scale Turbula ® Mixer. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2015, 95, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Ouyang, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, J. State of the Art and Prospects in Sliver- and Copper-Matrix Composite Electrical Contact Materials. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wen, X.; Ding, Z.; Yuwen, F.; Meng, J.; Yao, R. 5. Silver-Based Self-Lubricating Composite for Sliding Electrical Contact: Material Design, Preparation, and Properties. In Wear of Composite Materials; Davim, J. P., Ed.; De Gruyter, 2018; pp 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Silvain, J.-F.; Thomas, B.; Constantin, L.; Pontoreau, M.; Lu, Y.; Grosseau-Poussard, J.-L.; Lacombe, G. Silver/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite Materials Synthesized via a Green Molecular Level Mixing. J. Compos. Mater. 2023, 57, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Kang, X.; Zhang, L. Friction Maps and Wear Maps of Ag/MoS2/WS2 Nanocomposite with Different Sliding Speed and Normal Force. Tribol. Int. 2021, 164, 107228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, J.; Bezborah, K. Recent Advances in the Functionalization, Substitutional Doping and Applications of Graphene/Graphene Composite Nanomaterials. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 13413–13444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faniyi, I.O.; Fasakin, O.; Olofinjana, B.; Adekunle, A.S.; Oluwasusi, T.V.; Eleruja, M.A.; Ajayi, E.O.B. The Comparative Analyses of Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO) Prepared via Green, Mild and Chemical Approaches. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Zhang, L. Enhanced Sliding Electrical Contact Properties of Silver Matrix Self-Lubricating Nanocomposite Using Molecular Level Mixing Process and Spark Plasma Sintering. Powder Technol. 2020, 372, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, M.; Gavriliu, S.; Patroi, D.; Lucaci, M. Some Considerations Concerning the Obtaining of Some Ag-SnO2 Sintered Electrical Contacts for Low Voltage Power Engineering Switching Devices. Adv. Mater. Res. 2007, 23, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehani, B.; Joshi, P.B.; Khanna, P.K. Fabrication of Silver-Graphite Contact Materials Using Silver Nanopowders. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2010, 19, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, M.; Fernandez, A.; Menendez, J.L.; Torrecillas, R.U.H.; Hennicke, J.; Kirchner, R.; Kessel, T. Challenges and Opportunities for Spark Plasma Sintering: A Key Technology for a New Generation of Materials. In Sintering Applications; Ertug, B., Ed.; InTech, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An Improved Technique for Determining Hardness and Elastic Modulus Using Load and Displacement Sensing Indentation Experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, M.V.; Enescu, E.; Tălpeanu, D.; Pătroi, D.; Marinescu, V.; Sobetkii, A.; Stancu, N.; Lucaci, M.; Marin, M.; Manta, E. Enhanced Metallic Targets Prepared by Spark Plasma Sintering for Sputtering Deposition of Protective Coatings. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, M.; Tsakiris, V.; Enescu, E.; Pătroi, D.; Marinescu, V.; Tălpeanu, D.; Pavelescu, D.; Dumitrescu, G.; Radulian, A. Development of W-Cu-Ni Electrical Contact Materials with Enhanced Mechanical Properties by Spark Plasma Sintering Process. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2014, 125, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thet, N.S.; Makhadilov, I.M.; Malakhinsk, A.P.; Solis, P. The Influence of DC Pulse Current Pattern on the Different Materials Properties of Samples Obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering. In 8th International Congress on Energy Fluxes and Radiation Effects; Crossref, 2022; pp 344–350. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, L. Tribological Behaviors of Ag−graphite Composites Reinforced with Spherical Graphite. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2020, 30, 2177–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C. Friction of Metal-Matrix Self-Lubricating Composites: Relationships among Lubricant Content, Lubricating Film Coverage, and Friction Coefficient. Friction 2020, 8, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Xing, P.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H. Theoretical Modeling and Numerical Simulation of Current-Carrying Friction and Wear: State of the Art and Challenges. Lubricants 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, X.; Kang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, H. Progress on Current-Carry Friction and Wear: An Overview from Measurements to Mechanism. Coatings 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalifa, M.; Starr, A.; Khan, M. Current Research and Challenges in Modelling Wear, Friction, and Noise in Mechanical Contacts. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2025, 239, 985–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengyi, G.; Xin, G.; Zhiyong, W.; Yuting, W.; Xili, W. Simulation on Current Density Distribution of Current-Carrying Friction Pair Used in Pantograph-Catenary System. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 25770–25776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Du, M.; Zuo, X. Influence of Electric Current on the Temperature Rise and Wear Mechanism of Copper–Graphite Current-Carrying Friction Pair. J. Tribol. 2022, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, W.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y. The Influence of Initial Surface Roughness on the Current-Carrying Friction Process of Elastic Pairs. Materials 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Z. MATLAB Simulation of Current-Carrying Friction between Catenary and Bow Net of High-Speed Train under Fluctuating Load. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, T.; Chen, W.; Peng, D.; Wu, Z.; Ma, M.; Zheng, Q. The Anomalous Effect of Electric Field on Friction for Microscale Structural Superlubric Graphite/Au Contact. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Kang, X. Numerical Simulation of the Friction Damage Mechanism for Low Wear Silver Matrix Nanocomposite Using the Discrete Element Method. Mater. Lett. 2022, 324, 132772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, S.; Li, A.; Ma, H.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, M.; Xie, M. Properties of Ag-GNP Silver-Graphene Composites and Finite Element Analysis of Electrical Contact Coupling Field. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freschi, M.; Dragoni, L.; Mariani, M.; Haiko, O.; Kömi, J.; Lecis, N.; Dotelli, G. Tuning the Parameters of Cu–WS2 Composite Production via Powder Metallurgy: Evaluation of the Effects on Tribological Properties. Lubricants 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freschi, M.; Arrigoni, A.; Haiko, O.; Andena, L.; Kömi, J.; Castiglioni, C.; Dotelli, G. Physico-Mechanical Properties of Metal Matrix Self-Lubricating Composites Reinforced with Traditional and Nanometric Particles. Lubricants 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ma, C.; Kang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Effect of WS2 Particle Size on Mechanical Properties and Tribological Behaviors of Cu-WS2 Composites Sintered by SPS. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2018, 28, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z. Study on the Properties of Ag–Cr2 AlC Composite as a Sliding Electrical Contact Material. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderete, B.; Schäfer, C.; Nayak, U.P.; Mücklich, F.; Suarez, S. Modifying the Characteristics of the Electrical Arc Generated during Hot Switching by Reinforcing Silver and Copper Matrices with Carbon Nanotubes. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng Jiang; Feng Li; Yaping Wang. Effect of Different Types of Carbon on Microstructure and Arcing Behavior of Ag/C Contact Materials. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Technol. 2006, 29, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Akbulut, H.; Tokur, M.; Algül, H.; Çetinkaya, T. Structural and Sliding Wear Properties of Ag/Graphene/WC Hybrid Nanocomposites Produced by Electroless Co-Deposition. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 654, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Hao, W.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Lu, Y. The Corrosion Behavior of Different Silver Plating Layers as Electrical Contact Materials in Sulfur-Containing Environments. Coatings 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Zhou, M.; Gao, J.; Luo, C.; Li, X.; You, S.; Wang, M.; Cheng, G. Optimization of Cyanide-Free Composite Electrodeposition Based on π-π Interactions Preparation of Silver-Graphene Composite Coatings for Electrical Contact Materials. Nanomaterials 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlus, P.; Reizer, R. A State of the Art on Mechanically Dominated Methods of Wear Modelling. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fitzgerald, M.L.; Tao, Y.; Pan, Z.; Sauti, G.; Xu, D.; Xu, Y.-Q.; Li, D. Electrical and Thermal Transport through Silver Nanowires and Their Contacts: Effects of Elastic Stiffening. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 7389–7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solid Lubricants |

Main Properties of Solid Lubricants | Key Benefits in AgMCs and AgMNCs |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) |

- 2D layered TMD structure, - Good lubricity in vacuum and dry air, - Moderate oxidation resistance, - Stable up to 350°C, COF of 0.05−0.25 in dry tribo-contacts. |

- Forms stable tribofilm, - Reduces friction and wear, - Improves load capacity. |

[6,15,16,27,29,41] |

| Tungsten disulfide (WS2) |

- 2D layered TMD structure; - Higher oxidation and thermal stability than MoS₂; - Lower COF than MoS₂ under high load; - Stable up to 425°C, COF of 0.05−0.25 in dry tribo-contacts. |

- Enhances tribological performance at high temperature (HT), - Improves durability in oxidative environments. |

[4,17,18,27,29] |

| MoS₂ + WS₂ | - Synergistic 2D layered lubricants with improved vacuum and dry air performance versus single phases (MoS2 or WS2) |

- Enhances self-lubricating performance of composites under vacuum. |

[29,44] |

| Graphite | - 2D layered carbon structure, - Excellent lubricity in humid/HT environments, - Cost-effective, lightweight, good electrical conductivity; - Stable up to 500°C, COF of 0.1−0.3 in dry tribo-contacts. |

- Lowers friction in ambient air, - Improves wear resistance, - Higher graphite contents reduce conductivity and strength. |

[6,19,26,27,28] |

| Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) |

- Tubular carbon nanostructures (SWCNTs or MWCNTs), - High aspect ratio (length to diameter (L/D) ratio), - Thermal stability depends on CNT size (shorter/larger diameter CNTs are more resistant to thermal loads), - Lightweight (bulk density of CNTs of ~1.3−2.1 g/cm3), - Excellent mechanical and electrical properties. |

- Enhance hardness and wear resistance, and maintain conductivity of composites if CNTs are well-dispersed in Ag matrix, and/or surface functionalized; - Promotes tribofilm formation. |

[2,20,28,42,43,45,46] |

| Graphene / Graphene Oxide (GO) / Reduced GO (rGO) |

- Monolayer/multilayer 2D carbon sheet structure, - Remarkable mechanical strength, - High electrical and thermal conductivity, - High aspect ratio (lateral dimension to sheet thickness ratio). |

- Strengthen Ag matrix, - Reduces friction and wear, - Conductivity/strength depend on graphene/GO/rGO contents. |

[24,25,26] |

| Features | Conventional Powder Metallurgy (PM) | Hot Pressing Sintering (HPS) |

Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compaction method | Cold pressing at RT | Heat and uniaxial pressure applied simultaneously during sintering |

Uniaxial pressure combined with high-intensity, low-voltage pulsed (on-off) electric current |

| Sintering process | Furnace-heating without external pressure during densification | Pressure-assisted furnace sintering |

Field-assisted rapid sintering with pressure and pulsed (on-off) electric current |

| Sintering temperature (Ts) |

High Ts (typical 700–850°C) |

Lower Ts than in conventional PM |

Significantly lower Ts than in conventional PM by more than 200°C due to rapid Joule heating |

| Dwell time (DT) at Ts | Long (hours) | Long (hours) | Very short (minutes) |

| Heating rate (HR) | Slow (typical 5–10°C/min) |

Slow (typical 10–50°C/min) |

Very fast (typical 50–300°C/min, depending on SPS equipment and sample size) |

| Cooling rate (CR) | Slow (typical 1–10°C/min) | Slow (typical 10–50°C/min) | Very fast (typical ≤ 150°C/min) |

| Densification mechanisms |

Solid-state diffusion, Neck growth of powder particles, Shrinkage of compacts |

Pressure assisted plastic deformation, Volume diffusion |

Pressure-assisted deformation, enhanced diffusion, Joule heating effect, and localized vaporization/plasma surface cleaning |

| Grain size | Larger grains, more grain growth than in HPS/SPS | Finer grains than in conventional PM |

Nanostructure retention with minimal grain growth |

| Relative density (RD) and porosity of sintered AgMNCs |

Lower RD (often < 95% of TD), higher porosity than in HPS and SPS |

Higher RD, lower porosity than in conventional PM |

Very high RD (often 99% of TD), lowest porosity |

| Distribution/bonding of solid lubricants into Ag matrix | Higher risk of agglomeration, often weak bonding | Better dispersion, improved bonding |

Best dispersion and strong bonding |

| Mechanical/tribological properties of sintered AgMNCs | Good properties | Improved properties | High-performance SECs with superior properties |

| Processing cost | Cost-effective | Moderate cost | High cost (specialized SPS equipment, graphite/WC dies) |

| Scalability | High scalability | Moderate scalability | Reduced scalability (restricted by die size and equipment cost) |

| AgMNC Composition |

PM Route and Key Parameters (Pp, Ts, DT) |

AgMNC Pin Dimensions, Relative Density, hardness |

CB Disc Material, Diameter, Hardness |

Tribological Test Conditions |

Average Coefficient of Friction of AgMNCs |

Average Wear Rate of AgMNC Pins (mm3/N·m) |

Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fn (N) |

vs (m/s) |

d (m) |

|||||||

| Ag-10 wt.%WS2- 5 wt.%MoS2 |

HPS in N2 gas: 25 MPa, 750°C, DT: NR |

3 × 3 × 3 mm3, 99%, 73.4 HB |

Ag-10%Cu, Ø50 mm, 120.3 HB |

1 | 0.01 | 1000 | 0.16 | 2.17×10⁻6 | [6] |

| 1 | 0.1 | 1000 | 0.12 | 2.82×10⁻6 | |||||

| 1 | 1.0 | 1000 | 0.14 | 8.17×10⁻6 | |||||

| Ag-10 wt.%WS2- 5 wt.%MoS2 NC |

SPS, vacuum: 50 MPa, 750°C, 5 min |

3 × 3 × 3 mm3, 98.9%, 71.6 HB | Ag-10%Cu, Ø: NR, 120 HB |

1 | 0.01–1.0 | 10000 | 0.126–0.158 | (1.37–6.17)×10⁻6 | [60] |

| Ag-10 wt.%WS2- 5 wt.%MoS2 MC |

3 × 3 × 3 mm3, 97.9%, 52.1 HB | 1 | 0.01–1.0 | 10000 | 0.158–0.178 | (35.28–92.97)×10⁻6 | |||

| Ag-WS2-MoS2 (composition: NR) |

HPS in N2 gas: 24 MPa, 780°C, DT: NR |

Ø12 mm × 1.5 mm, 98%, 63.9 HV0.5 |

Ag-Cu, Ø50 mm, Alloy composition + HB: NR |

0.25 | 0.1–1.0 | 5000 | 0.31–0.65 | (2.67–19.80)×10⁻5 | [57] |

| 0.5 | 0.1–1.0 | 5000 | 0.27–0.38 | (4.30–13.51)×10⁻5 | |||||

| 1 | 0.1–1.0 | 5000 | 0.20–0.27 | (3.05–8.38)×10⁻5 | |||||

| 2 | 0.1–1.0 | 5000 | 0.14–0.25 | (5.45–11.49)×10⁻5 | |||||

| 4 | 0.1–1.0 | 5000 | 0.09–0.14 | (3.03–18.48)×10⁻5 | |||||

| Ag-10 wt.%WS2- 10 wt.%MoS2 NC |

SPS, atm. NR: 40 MPa, ~800°C, 10 min |

3 × 3 × 3 mm3, 98.8%, 70.7 HB | Ag-10%Cu, Ø: NR, 119.7 HB |

1 | 0.1–1.0 | 10000 | 0.125–0.139 | (2.53–7.49)×10⁻6 | [29] |

| Ag-10 wt.%WS2- 10 wt.%MoS2 MC |

3 × 3 × 3 mm3, 97.6%, 51.3 HB | 1 | 0.1–1.0 | 10000 | 0.155–0.171 | (12.39–35.81)×10⁻6 | |||

| Ag-30 vol.%WS2 | SPS: atm. NR: 35 MPa, 750°C, 10 min | POD testing conditions: NR Pin size, relative density and hardness: NR |

Parallel-plane | 0.16 | 3.08×10⁻5 | [18] | |||

| Perpendicular-plane | 0.24 | 8.23×10⁻5 | |||||||

| Ag-5 vol.% SG | SPS, vacuum: 40 MPa, 750°C, 10 min |

3 × 4 × 4 mm3, 98.2%, 78.9 HV1 | Ag-10%Cu, Ø: NR, 120 HV1 |

3 | 0.5 | 20000 | 0.44 | 6.7×10⁻5 | [68] |

| Ag-35 vol.% SG | 3 × 4 × 4 mm3, 97.4%, 46.3 HV1 | 3 | 0.5 | 20000 | 0.16 | 0.16×10⁻5 | |||

| Ag-5 vol.% FG | SPS, vacuum: 40 MPa, 750°C, 10 min |

3 × 4 × 4 mm3, 97.4%, 68.3 HV1 | Ag-10%Cu, Ø: NR, 120 HV1 |

3 | 0.5 | 20000 | 0.42 | 25×10⁻5 | [68] |

| Ag-35 vol.% FG | 3 × 4 × 4 mm3, 95.1%, 38.5 HV1 | 3 | 0.5 | 20000 | 0.21 | 6.5×10⁻5 | |||

| Sliding Speed |

Applied Normal Force | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 N | 0.5 N | 1 N | 2 N | 4 N | |

| Wear Mechanisms | |||||

| 0.1 m/s | Adhesion | Adhesion | Ploughing | Ploughing | Ploughing |

| 0.2 m/s | Ploughing | Adhesion | Adhesion | Ploughing | Adhesion |

| 0.4 m/s | Ploughing | Ploughing | Ploughing | Adhesion | Adhesion |

| 0.6 m/s | Ploughing | Ploughing | Ploughing | Adhesion | Adhesion |

| 0.8 m/s | Adhesion | Adhesion | Adhesion | Oxidation delamination | Oxidation delamination |

| 1.0 m/s | Adhesion | Adhesion | Adhesion | Oxidation delamination | Oxidation delamination |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).