Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

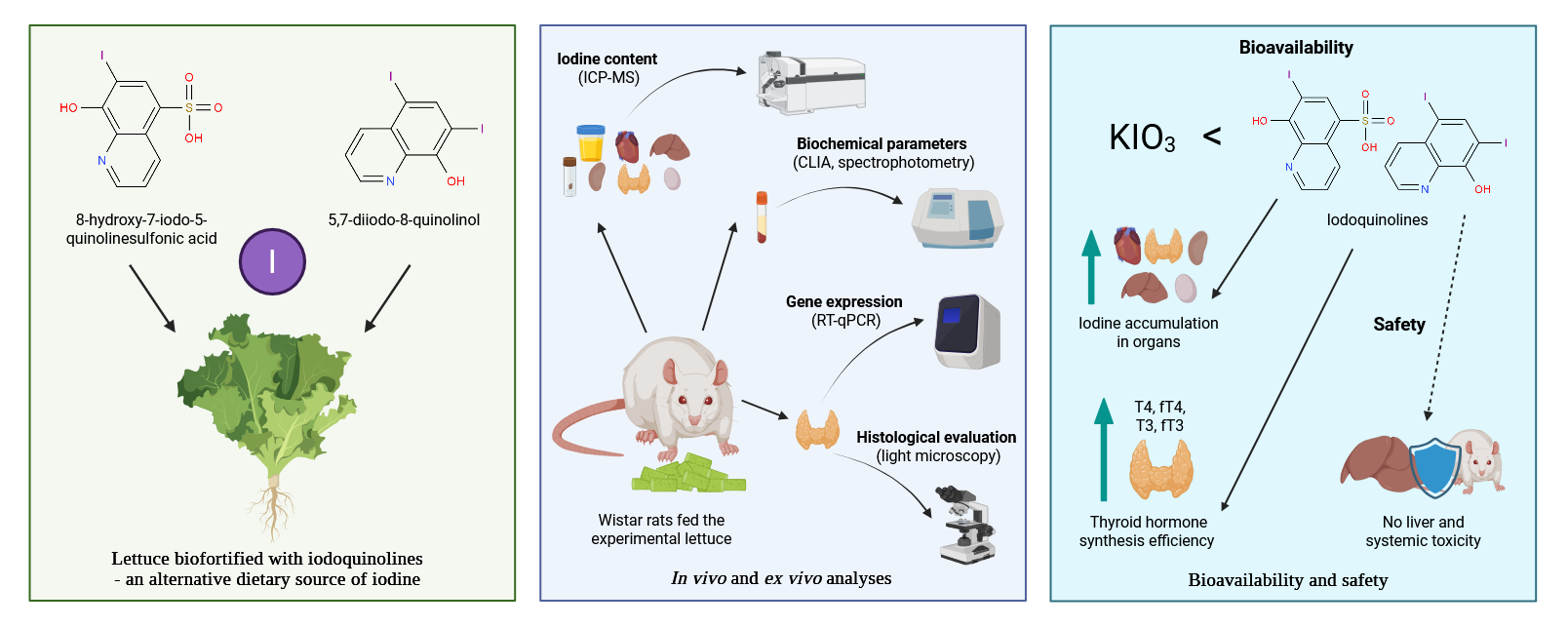

Background/Objectives: Iodine plays a key role in thyroid hormone synthesis and metabolic regulation in vertebrates. This study aimed to evaluate the in vivo bioavailability of iodine and assess selected biochemical parameters and thyroid-related gene expression in male Wistar rats fed lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) biofortified with iodoquinolines (8-hydroxy-7-iodo-5-quinolinesulfonic acid or 5,7-diiodo-8-quinolinol) or potassium iodate. Methods: Two iodine intake levels were applied: a nutritionally adequate iodine level and a supranutritional level, to evaluate the nutritional safety of iodine obtained from biofortified vegetables. Results: A diet containing lettuce biofortified with iodoquinolines at the adequate level had no significant effect on thyroid hormone concentrations, expression of Dio1, Dio2, Slc5a5, and Tpo genes, or thyroid morphology. While supranutritional iodine intake led to increased levels of T4, fT4, T3, and fT3, all hormone concentrations remained within the physiological range. No elevation in liver enzyme activity (ALT, AST, ALP) was observed, indicating the absence of hepatotoxic effects from high-iodine diets based on biofortified lettuce. Compared to potassium iodate, iodoquinolines demonstrated superior bioavailability, as evidenced by enhanced iodine accumulation in tissues and more efficient thyroid hormone synthesis. Conclusions: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first in vivo nutritional study assessing the physiological effects of supranutritional iodine intake from a biofortified plant source. These findings confirm the nutritional safety and efficacy of iodine biofortification using iodoquinolines and highlight the need for further research, including human nutritional clinical trials.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growing Conditions

2.1.1. Chemical Composition Analysis of Plant Material

2.2. Animal Study

2.2.1. Assessment of Iodine Content in Urine, Feces, and Selected Organs

2.2.2. Analysis of Biochemical Parameters

2.2.3. Gene Expression Analysis

2.2.4. Histological Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Iodine Content

3.1.1. Iodine Content in Urine and Feces

3.1.2. Iodine Content in Selected Organs

3.2. Biochemical Parameters

3.2.1. Lipid Profile

3.2.2. Hormones Regulating Thyroid Function

3.2.3. Other Biochemical Parameters

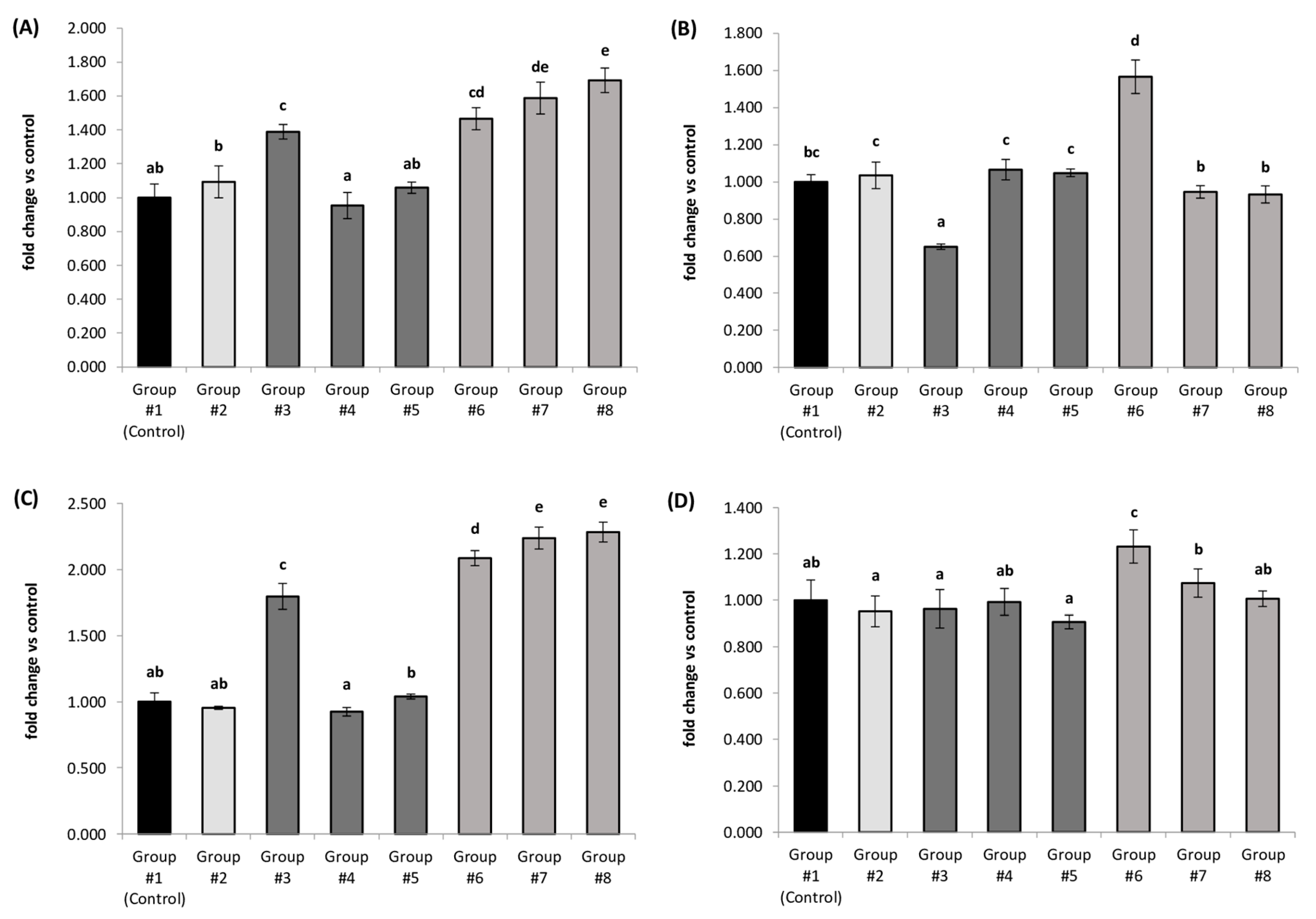

3.3. Relative Expression of Selected Genes Involved in Thyroid Hormone Metabolism

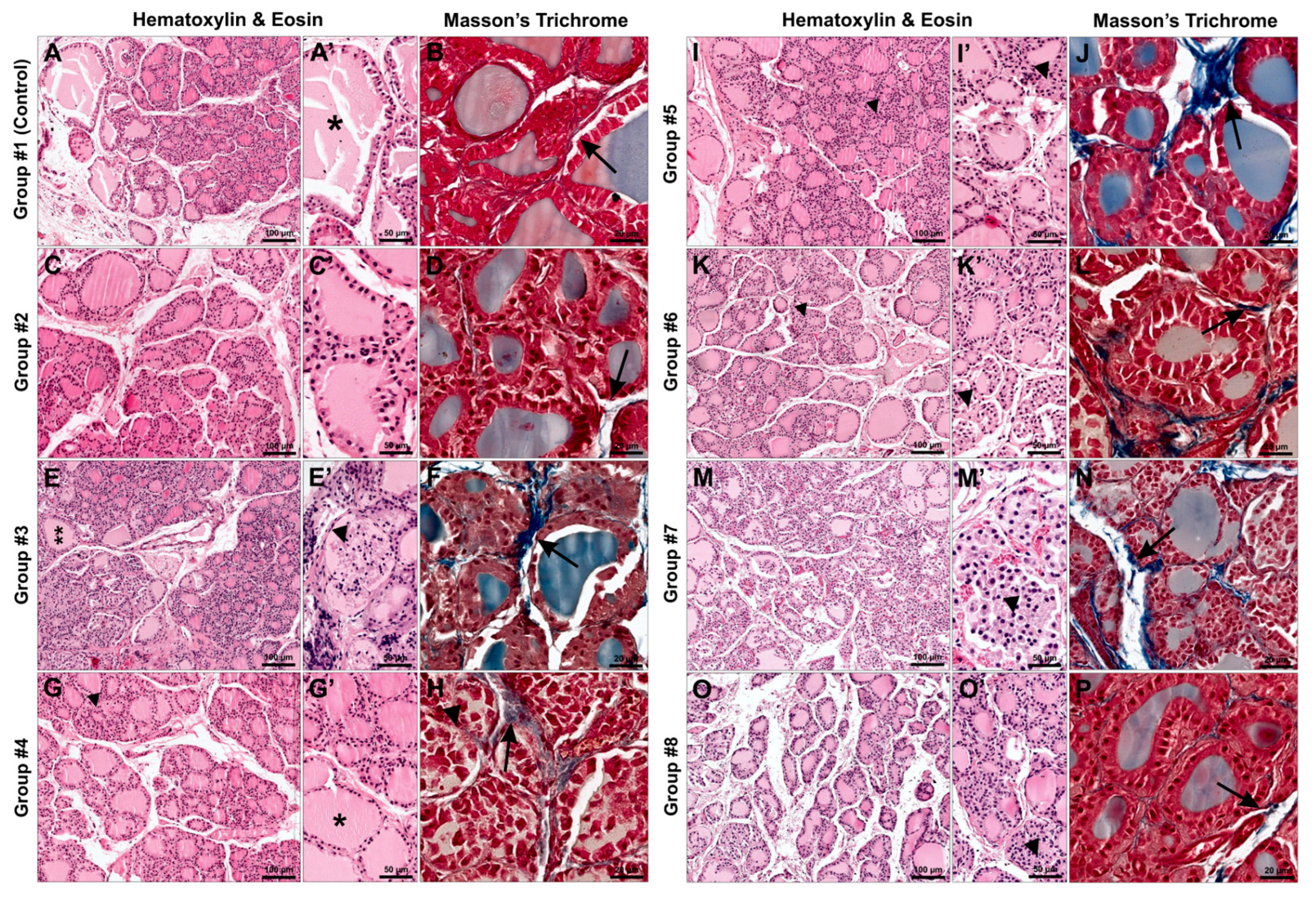

3.4. Histological Analysis

3.4.1. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

3.4.2. Masson’s Trichrome Staining

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aceves, C.; Mendieta, I.; Anguiano, B.; Delgado-González, E. Molecular iodine has extrathyroidal effects as an antioxidant, differentiator, and immunomodulator. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, R.; Yan, M.; Han, P.; Wang, T.; Li, B.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, T.; Hu, Y.; Borthwick, A.G.L.; Zheng, C.; Ni, J. Deficiency and excess of groundwater iodine and their health associations. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blikra, M.J.; Aakre, I.; Rigutto-Farebrother, J. Consequences of acute and long-term excessive iodine intake: A literature review focusing on seaweed as a potential dietary iodine source. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonacchera, M.; Dimida, A.; De Servi, M.; Frigeri, M.; Ferrarini, E.; De Marco, G.; Grasso, L.; Agretti, P.; Piaggi, P.; Aghini-Lombardi, F.; Perata, P.; Pinchera, A.; Vitti, P. Iodine fortification of vegetables improves human iodine nutrition: In vivo evidence for a new model of iodine prophylaxis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E694–E697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, F.; Zimmermann, M.; Jooste, P.; Pandav, C.; Caldwell, K.; Raghavan, R.; Raiten, D.J. Biomarkers of nutrition for development – iodine review. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1322S–1342S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.X.; Yan, A.L.; Hong, C.L.; Qin, Y.C.; Pan, L.; Xie, L.L. Biogeochemical transfer and dynamics of iodine in a soil-plant system. Environ. Geochem. Health 2009, 31, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.M.; Costa, N.M.B.; Nutti, M.R.; Tako, E.; Martino, H.S.D. Advantages and limitations of in vitro and in vivo methods of iron and zinc bioavailability evaluation in the assessment of biofortification program effectiveness. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2136–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Frano, M.R.; De Moura, F.F.; Boy, E.; Lönnerdal, B.; Burri, B.J. Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and provitamin A carotenoids in biofortified staple crops. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Straeten, D.; Bhullar, N.K.; De Steur, H.; Gruissem, W.; MacKenzie, D.; Pfeiffer, W.; Qaim, M.; Slamet-Loedin, I.; Strobbe, S.; Tohme, J.; Trijatmiko, K.R.; Vanderschuren, H.; Van Montagu, M.; Zhang, C.; Bouis, H. Multiplying the efficiency and impact of biofortification through metabolic engineering. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.M.; Braverman, L.E. Consequences of excess iodine. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.N.; Albrecht, D.; Scholz, A.; Gutierrez-Buey, G.; Lazarus, J.H.; Dayan, C.M.; Okosieme, O.E. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hu, C.; Xia, B.; Zhou, X.; Luo, S.; Gan, R.; Duan, P.; Tan, Y. Iodine excess induces hepatic, renal and pancreatic injury in female mice as determined by attenuated total reflection Fourier-transform infrared spectrometry. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2022, 42, 600–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyląg, A.; Smoleń, S.; Wisła-Świder, A.; Kowalska, I.; Sularz, O.; Krzemińska, J.; Pitala, J.; Koronowicz, A. Evaluation of the chemical composition and nutritional value of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) biofortified in hydroponics with iodine in the form of iodoquinolines. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1288773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, P.G. Components of the AIN-93 diets as improvements in the AIN-76A diet. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 838S–841S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smoleń, S.; Kowalska, I.; Kováčik, P.; Halka, M.; Sady, W. Biofortification of six varieties of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) with iodine and selenium in combination with the application of salicylic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PN-EN 15111:2008. Foodstuffs – Determination of trace elements – Determination of iodine content by ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry); Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2008; Available online: https://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-en-15111-2008p.html (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Oliveira, M.J.A.; van Deventer, H.E.; Bachmann, L.M.; Warnick, G.R.; Nakajima, K.; Nakamura, M.; Sakurabayashi, I.; Kimberly, M.M.; Shamburek, R.D.; Korzun, W.J.; Myers, G.L.; Miller, W.G.; Remaley, A.T. Evaluation of four different equations for calculating LDL-C with eight different direct HDL-C assays. Clin. Chim. Acta 2013, 423, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedewald, W.T.; Levy, R.I.; Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikra, M.J.; Henjum, S.; Aakre, I. Iodine from brown algae in human nutrition, with an emphasis on bioaccessibility, bioavailability, chemistry, and effects of processing: A systematic review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1517–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.R.; Ammerman, C.B. Iodine bioavailability. In Bioavailability of Nutrients for Animals; Ammerman, C.B., Baker, D.H., Lewis, A.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, USA, 1995; pp. 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlucny, K.; Alexander, B.M.; Gerow, K.; Larson-Meyer, D.E. Reflection of dietary iodine in the 24 h urinary iodine concentration, serum iodine and thyroglobulin as biomarkers of iodine status: A pilot study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeć, A.; Piątkowska, E.; Bieżanowska-Kopeć, R.; Pysz, M.; Koronowicz, A.; Kapusta-Duch, J.; Smoleń, S.; Rakoczy, R.; Skoczylas, Ł.; Leszczyńska, T.; Ledwożyw-Smoleń, I. Effect of lettuce biofortified with iodine by soil fertilization on iodine concentration in various tissues and selected biochemical parameters in serum of Wistar rats. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 14, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakoczy, R.; Kopeć, A.; Piątkowska, E.; Smoleń, S.; Skoczylas, Ł.; Leszczyńska, T.; Sady, W. The iodine content in urine, feces and selected organs of rats fed lettuce biofortified with iodine through foliar application. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016, 174, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Moon, Y.; Tou, J.C.; Mou, B.; Waterland, N.L. Nutritional value, bioactive compounds and health benefits of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 49, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorach, R.; Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Gil, M.I.; Ferreres, F. Characterisation of polyphenols and antioxidant properties of five lettuce varieties and escarole. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-González, M.R.; Chiocchetti, G.M.; Herbello-Hermelo, P.; Velez, D.; Devesa, V.; Bermejo-Barrera, P. Evaluation of iodine bioavailability in seaweed using in vitro methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8435–8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairweather-Tait, S.; Hurrell, R.F. Bioavailability of minerals and trace elements: Members of EC flair concerted action no. 10: Measurements of micronutrient absorption and status. Nutr. Res. Rev. 1996, 9, 295–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchgessner, M.; Gabler, S.; Windisch, W. Homeostatic adjustments of selenium metabolism and tissue selenium to widely varying selenium supply in 75Se-labeled rats. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 1997, 78, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, H. Dietary polyphenol, gut microbiota, and health benefits. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Sang, L.; Zhu, J.; Luo, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, K.; Chen, L.; Du, J.; Kan, J.; He, H. Intermediate role of gut microbiota in vitamin B nutrition and its influences on human health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1031502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Meng, L.; Shen, L.; Ji, H.F. Regulation of gut microbiota by vitamin C, vitamin E and β-carotene. Food Res. Int. 2023, 169, 112749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Meng, F.; Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Shan, Z. Effects of iodine intake on gut microbiota and gut metabolites in Hashimoto thyroiditis-diseased humans and mice. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virili, C.; Centanni, M. “With a little help from my friends” – the role of microbiota in thyroid hormone metabolism and enterohepatic recycling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 458, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, E.; Wahl, R. Microbiota and thyroid interaction in health and disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 30, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouga, M.; Lean, M.E.J.; Combet, E. Contemporary challenges to iodine status and nutrition: the role of foods, dietary recommendations, fortification and supplementation. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchgessner, B.M.; He, J.; Windisch, W. Homeostatic adjustments of iodine metabolism and tissue iodine to widely varying iodine supply in 125I-labeled rats. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 1999, 82, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piątkowska, E.; Kopeć, A.; Bieżanowska-Kopeć, R.; Pysz, M.; Kapusta-Duch, J.; Koronowicz, A.A.; Smoleń, S.; Skoczylas, Ł.; Ledwożyw-Smoleń, I.; Rakoczy, R.; Maślak, E. The impact of carrot enriched in iodine through soil fertilization on iodine concentration and selected biochemical parameters in Wistar rats. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.A.; Singh, B.K.; Yen, P.M. Direct effects of thyroid hormones on hepatic lipid metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, E.; Chiovato, L.; Pinchera, A. Thyroid and lipid metabolism. Int. J. Obes. 2000, 24, S109–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.J.; Ye, Y.; Sun, F.J.; Tian, E.J.; Chen, Z.P. The impact of dietary iodine intake on lipid metabolism in mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 142, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waśniowska, J.; Piątkowska, E.; Pawlicki, P.; Smoleń, S.; Kopeć, A.; Dyląg, A.; Krzemińska, J.; Koronowicz, A. Comparative analysis of iodine levels, biochemical responses, and thyroid gene expression in rats fed diets with kale biofortified with 5,7-diiodo-8-quinolinol. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duntas, L.H.; Brenta, G. The effect of thyroid disorders on lipid levels and metabolism. Med. Clin. North Am. 2012, 96, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duntas, L.H. Thyroid disease and lipids. Thyroid 2002, 12, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, A.; Garcia, E.; Gruppen, E.G.; Kremer, D.; Connelly, M.A.; Bakker, S.J.; Dullaart, R.P. Higher free triiodothyronine is associated with higher HDL particle concentration and smaller HDL particle size. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e1807–e1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, A.; Bagherniya, M.; Fakheran, O.; Reiner, Ž.; Xu, S.; Sahebkar, A. Medicinal plants and bioactive natural compounds as inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase: A literature review. BioFactors 2020, 46, 906–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.S.; Jeon, S.M.; Kim, M.J.; Yeo, J.; Seo, K.I.; Choi, M.S.; Lee, M.K. Chlorogenic acid exhibits anti-obesity property and improves lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced-obese mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.Y.C.; Ho, H.K. Pharmacological modulation of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) as a therapeutic strategy for hypercholesterolemia. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 220, 115985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, K.F.; Day, P.E.; Aboufarrag, H.T.; Kroon, P.A. Polyphenol effects on cholesterol metabolism via bile acid biosynthesis, CYP7A1: a review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Luo, M.; Yang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, J.; Lu, C.; Song, D.; Ye, M.; Dai, M.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Liu, A.; Guo, B. Chlorogenic acid inhibits cholestatic liver injury induced by α-naphthylisothiocyanate: involvement of STAT3 and NFκB signalling regulation. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 68, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duntas, L.H.; Brenta, G. A renewed focus on the association between thyroid hormones and lipid metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.A.; Kersten, S.; Qi, L. Lipoprotein lipase and its regulators: an unfolding story. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; He, R.R.; Zeng, X.H.; Huang, X.J.; Du, T.L.; Cui, J.C.; Hiroshi, K. Hypotriglyceridemic effects of apple polyphenols extract via up-regulation of lipoprotein lipase in triton WR-1339-induced mice. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2014, 20, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgi, H. Iodine excess. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 24, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, P.; Begall, S.; Frädrich, C.; Renko, K.; Hildebrandt, T.B.; Holtze, S.; Heinrich, A.; Sahm, A.; Meci, X.; Köhrle, J.; Rijntjes, E.; Henning, Y. Comparative analysis of thyroid hormone systems in rodents with subterranean lifestyle. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.G.; Hong, Z.S.; Li, Z.H.; Xu, C.X.; Jin, X.; Jin, M.G.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, N.J.; Koh, T.S.; Choi, Y.J. Effect of brown seaweed waste supplementation on lactational performance and endocrine physiology in Holstein lactating cows. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2005, 47, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, K.; Meyer, U.; Wagner, H.; Hoppen, H.O.; Flachowsky, G. Effect of various iodine supplementations, rapeseed meal application and two different iodine species on the iodine status and iodine excretion of dairy cows. Livest. Sci. 2009, 125, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoe, S.; Yamanaka, C.; Ohtoshi, H.; Nakamura, F.; Fujiwara, S. Effects of daily kelp (Laminaria japonica) intake on body composition, serum lipid levels, and thyroid hormone levels in healthy Japanese adults: a randomized, double-blind study. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, Y.N.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, L.; Ye, Y.; Lin, L.X.; Yan, Y.Q.; Chen, Z.P. The impact of iodine excess on thyroid hormone biosynthesis and metabolism in rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2009, 130, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Campen, D.R.; Glahn, R.P. Micronutrient bioavailability techniques: accuracy, problems and limitations. Field Crops Res. 1999, 60, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquaron, R.; Delange, F.; Marchal, P.; Lognoné, V.; Ninane, L. Bioavailability of seaweed iodine in human beings. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2002, 48, 563–569, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12146713/. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, I.; Seidlova-Wuttke, D.; Wuttke, W.; Köhrle, J. Effects of isoflavonoids and other plant-derived compounds on the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid hormone axis. Maturitas 2006, 55, S14–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranckx, R.; Rouaze-Romet, M.; Savu, L.; Mechighel, P.; Maya, M.; Nunez, E. A. Regulation of rat thyroxine-binding globulin and transthyretin: studies in thyroidectomized and hypophysectomized rats given tri-iodothyronine or/and growth hormone. J. Endocrinol. 1994, 142, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turakulov, Y.K.; Burikhanov, R.B.; Patkhitdinov, P.P.; Myslitskaya, A.I. Influence of immobilization stress on the level of secretion of thyroid hormones. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 1994, 24, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauncey, M.J.; Morovat, A. Investigation of mechanisms mediating the increase in plasma concentrations of thyroid hormones after a meal in young growing pigs. J. Endocrinol. 1993, 139, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piantanida, E.; Ippolito, S.; Gallo, D.; Masiello, E.; Premoli, P.; Cusini, C.; Rosetti, S.; Sabatino, J.; Segato, S.; Trimarchi, F.; Bartalena, L.; Tanda, M.L. The interplay between thyroid and liver: implications for clinical practice. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2020, 43, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgona, N.; Taki, Y.; Yamada, S.; Umegaki, K. Dietary Coleus forskohlii extract generates dose-related hepatotoxicity in mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2013, 33, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domitrović, R.; Potočnjak, I. A comprehensive overview of hepatoprotective natural compounds: mechanism of action and clinical perspectives. Arch. Toxicol. 2016, 90, 39–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koriem, K.M.; Soliman, R.E. Chlorogenic and caftaric acids in liver toxicity and oxidative stress induced by methamphetamine. J. Toxicol. 2014, 2014, 583494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Su, R.Q. Protective effect of chlorogenic acid against carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver damage in rats. Chin. Herb. Med. 2014, 6, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, E.M.; Wu, G.Y. Subnormal serum liver enzyme levels: a review of pathophysiology and clinical significance. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2024, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Zhong, S.; Xie, K.; Yu, D.; Yang, R.; Gong, D.W. Hepatic ALT isoenzymes are elevated in gluconeogenic conditions including diabetes and suppressed by insulin at the protein level. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2015, 31, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Pal, D.; Prasad, R. Alkaline phosphatase: an overview. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 29, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.J.; Choi, Y.K.; Im, H.S.; Yarimaga, O.; Yoon, E.; Kim, H.S. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST/GOT) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT/GPT) detection techniques. Sensors 2006, 6, 756–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Warren, F.J.; Gidley, M.J. Natural products for glycaemic control: Polyphenols as inhibitors of alpha-amylase. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Ni, X.; Kai, G.; Chen, X. A review on structure–activity relationship of dietary polyphenols inhibiting α-amylase. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, C.M.; Watrelot, A.A.; Le Bourvellec, C. Interactions between polyphenols and polysaccharides: Mechanisms and consequences in food processing and digestion. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 60, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleeff, J.; Whitcomb, D.C.; Shimosegawa, T.; Esposito, I.; Lerch, M.M.; Gress, T.; Mayerle, J.; Drewes, A.M.; Rebours, V.; Akisik, F.; Domínguez Muñoz, J.E.; Neoptolemos, J.P. Chronic pancreatitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ran, J.; Jiang, T. Urea. In Urea Transporters; Yang, B., Sands, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 73, pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris Jr, S.M. Regulation of enzymes of the urea cycle and arginine metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002, 22, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weismann, D.; Hartvigsen, K.; Lauer, N.; Bennett, K.L.; Scholl, H.P.; Issa, P.C.; Cano, M.; Brandstätter, H.; Tsimikas, S.; Skerka, C.; Superti-Furga, G.; Handa, J.T.; Zipfel, P.F.; Witztum, J.L.; Binder, C.J. Complement factor H binds malondialdehyde epitopes and protects from oxidative stress. Nature 2011, 478, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gereben, B.; McAninch, E.A.; Ribeiro, M.O.; Bianco, A.C. Scope and limitations of iodothyronine deiodinases in hypothyroidism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Uricoechea, H.; Nogueira, J.P.; Pinzón-Fernández, M.V.; Schwarzstein, D. The usefulness of thyroid antibodies in the diagnostic approach to autoimmune thyroid disease. Antibodies 2023, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luongo, C.; Dentice, M.; Salvatore, D. Deiodinases and their intricate role in thyroid hormone homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereben, B.; Salvatore, D.; Harney, J.W.; Tu, H.M.; Larsen, P.R. The human, but not rat, Dio2 gene is stimulated by thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1). Mol. Endocrinol. 2001, 15, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavado-Autric, R.; Calvo, R.M.; de Mena, R.M.; de Escobar, G.M.; Obregon, M.J. Deiodinase activities in thyroids and tissues of iodine-deficient female rats. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St. Germain, D.L.; Galton, V.A.; Hernandez, A. Defining the roles of the iodothyronine deiodinases: current concepts and challenges. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.R.; Bassett, J.D. Local control of thyroid hormone action: role of type 2 deiodinase. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 209, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.C.; Salas-Lucia, F.; Bianco, A.C. Deiodinases and the metabolic code for thyroid hormone action. Endocrinology 2021, 162, bqab059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.C.; Kim, B.W. Deiodinases: implications of the local control of thyroid hormone action. J. Clin. Invest. 2006, 116, 2571–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreft, I.; Fabjan, N.; Yasumoto, K. Rutin content in buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) food materials and products. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.F.L.; Santos, M.C.; Ginabreda, M.G.; Fortunato, R.S.; Carvalho, D.P.; Freitas Ferreira, A.C. Flavonoid rutin increases thyroid iodide uptake in rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, L. Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defense and thyroid hormone signaling: a focus on cardioprotective effects. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambe, F.; Nomura, Y.; Okamoto, T.; Seo, H. Redox regulation of thyroid-transcription factors, Pax-8 and TTF-1, is involved in their increased DNA-binding activities by thyrotropin in rat thyroid FRTL-5 cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 1996, 10, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, A.; Wang, Z.V.; Luo, Y.; Li, D.L.; Luo, X.; Schiattarella, G.G.; Altamirano, F.; May, H.I.; Battiprolu, P.K.; Nguyen, A.; Rothermel, B.A.; Lavandero, S.; Gillette, T.G.; Hill, J.A. FoxO1-Dio2 signaling axis governs cardiomyocyte thyroid hormone metabolism and hypertrophic growth. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjee, S.; Chauhan, S.; Pal, R.; Tomar, R.S. Mechanisms of DNA methylation and histone modifications. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 197, 51–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuting, P.M.; Dintzis, S.M.; Montine, K.S. (Eds.) Comparative anatomy and histology: a mouse, rat, and human atlas, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Group number | Urine [µg dm-3] | Feces [µg kg-1 d.w.] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second week | Seventh week | Second week | Seventh week | |

| Group #1 (Control) | 854.59 ± 24.81d | 856.25 ± 19.92d | 827.47 ± 31.01a | 826.02 ± 71.22a |

| Group #2 | 864.49 ± 13.99d | 873.41 ± 14.88de | 855.64 ± 22.93a | 851.25 ± 66.13a |

| Group #3 | 635.04 ± 9.86b | 588.84 ± 7.74b* | 965.91 ± 67.72b | 965.75 ± 70.15b |

| Group #4 | 757.51 ± 12.41c | 529.52 ± 10.19a* | 1030.54 ± 16.22b | 1061.51 ± 64.77b |

| Group #5 | 605.05 ± 6.14a | 610.07 ± 5.87c | 1029.06 ± 40.47b | 1011.45 ± 58.29b |

| Group #6 | 940.40 ± 33.47e | 888.92 ± 9.60e* | 1240.73 ± 41.30d | 1358.88 ± 13.11c* |

| Group #7 | 1087.66 ± 15.71f | 1032.51 ± 10.04g* | 1169.80 ± 9.21c | 1364.99 ± 55.18c* |

| Group #8 | 945.39 ± 5.36e | 912.06 ± 4.37f* | 1215.74 ± 46.68cd | 1338.09 ± 21.60c* |

| Group number | Thyroid [mg kg-1 d.w.] |

Liver [µg kg-1 d.w.] |

Kidneys [µg kg-1 d.w.] |

Heart [µg kg-1 d.w.] |

Testes [µg kg-1 d.w.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group #1 (Control) | 1716.20 ± 82.54b | 115.20 ± 11.20b | 190.80 ± 4.84c | 54.98 ± 2.98a | 155.75 ± 11.31b |

| Group #2 | 1797.98 ± 110.29bc | 118.94 ± 7.00b | 187.14 ± 2.77c | 45.17 ± 6.34a | 155.83 ± 9.20b |

| Group #3 | 1532.36 ± 34.02a | 85.87 ± 9.69a | 129.91 ± 3.95a | 51.06 ± 4.22a | 97.91 ± 3.75a |

| Group #4 | 1840.78 ± 57.63c | 156.02 ± 6.14c | 152.39 ± 9.73b | 74.23 ± 6.83b | 171.07 ± 5.64c |

| Group #5 | 1825.34 ± 68.90bc | 153.24 ± 3.53c | 189.79 ± 8.20c | 86.19 ± 5.39c | 199.27 ± 8.88d |

| Group #6 | 1778.71 ± 15.38bc | 110.35 ± 5.91b | 183.19 ± 5.34c | 68.18 ± 8.61b | 106.18 ± 5.19a |

| Group #7 | 1975.56 ± 10.25d | 175.85 ± 2.42d | 208.82 ± 8.37d | 96.66 ± 2.02d | 214.87 ± 1.74e |

| Group #8 | 1961.46 ± 71.66d | 192.58 ± 4.77e | 219.01 ± 3.15d | 94.15 ± 7.10cd | 224.99 ± 12.05e |

| Group number | HDL cholesterol [mg dl-1] |

LDL + VLDL cholesterol [mg dl-1] |

Total cholesterol [mg dl-1] |

Triglycerides [mg dl-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group #1 (Control) | 59.98 ± 1.03c | 17.08 ± 1.23c | 77.06 ± 4.40c | 230.48 ± 11.69bc |

| Group #2 | 57.99 ± 0.84c | 16.26 ± 0.47c | 74.25 ± 3.15c | 230.70 ± 9.15bc |

| Group #3 | 45.16 ± 0.76b | 14.59 ± 0.68b | 59.75 ± 1.62ab | 219.44 ± 3.08b |

| Group #4 | 47.35 ± 1.29b | 16.78 ± 0.56c | 64.13 ± 1.98b | 237.15 ± 12.49c |

| Group #5 | 46.78 ± 1.77b | 12.30 ± 0.81a | 59.08 ± 2.37ab | 167.98 ± 8.61a |

| Group #6 | 40.20 ± 2.18a | 20.50 ± 1.14d | 60.70 ± 4.01ab | 216.20 ± 8.88b |

| Group #7 | 42.00 ± 0.62a | 17.06 ± 0.97c | 59.06 ± 3.35a | 225.70 ± 6.14bc |

| Group #8 | 40.80 ± 1.57a | 15.87 ± 1.11bc | 56.67 ± 1.70a | 238.27 ± 4.47c |

| Group number | Thyroxine (T4) [nmol l-1] | Free T4 (fT4) [pmol l-1] | Triiodothyronine (T3) [nmol l-1] |

Free T3 (fT3) [pmol l-1] | Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) [mIU l-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group #1 (Control) | 101.00 ± 5.46b | 21.62 ± 2.81b | 1.30 ± 0.03b | 7.17 ± 0.18b | 4.12 ± 0.15ab |

| Group #2 | 101.50 ± 6.17b | 20.08 ± 1.89b | 1.31 ± 0.06b | 7.55 ± 0.53b | 4.18 ± 0.19ab |

| Group #3 | 84.70 ± 2.88a | 14.59 ± 1.01a | 1.16 ± 0.04a | 6.38 ± 0.16a | 4.05 ± 0.11a |

| Group #4 | 111.35 ± 3.83cd | 18.40 ± 2.45b | 1.36 ± 0.11b | 7.18 ± 0.29b | 4.23 ± 0.26ab |

| Group #5 | 111.60 ± 7.02cd | 19.55 ± 1.38b | 1.23 ± 0.07ab | 7.42 ± 0.45b | 4.26 ± 0.17ab |

| Group #6 | 105.17 ± 1.51bc | 25.66 ± 1.15c | 1.97 ± 0.14c | 8.53 ± 0.72c | 4.02 ± 0.08a |

| Group #7 | 114.98 ± 4.92d | 27.73 ± 1.93c | 2.13 ± 0.05d | 9.09 ± 0.63c | 4.19 ± 0.14ab |

| Group #8 | 116.90 ± 7.40d | 34.72 ± 1.90d | 2.84 ± 0.09e | 10.92 ± 0.44d | 4.38 ± 0.09b |

| Group number | Alanine aminotransferase [U l-1] |

Aspartate aminotransferase [U l-1] |

Alkaline phosphatase [U l-1] |

Urea [mg dl-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group #1 (Control) | 40.70 ± 2.25c | 95.53 ± 1.71ab | 16.20 ± 0.97c | 36.90 ± 1.65e |

| Group #2 | 40.90 ± 1.4c | 97.75 ± 4.54ab | 14.57 ± 1.58bc | 34.90 ± 0.61d |

| Group #3 | 33.99 ± 1.08ab | 100.40 ± 8.66bc | 12.29 ± 0.40a | 32.70 ± 1.23c |

| Group #4 | 36.19 ± 3.63b | 95.80 ± 6.75ab | 14.20 ± 0.49b | 26.27 ± 0.58a |

| Group #5 | 32.36 ± 0.66a | 90.44 ± 2.53a | 16.00 ± 0.62c | 27.36 ± 0.80a |

| Group #6 | 50.37 ± 2.82d | 106.60 ± 3.95c | 23.60 ± 1.33e | 34.13 ± 1.47cd |

| Group #7 | 41.06 ± 0.71c | 103.72 ± 1.62bc | 18.14 ± 0.51d | 35.78 ± 1.06de |

| Group #8 | 35.23 ± 1.19ab | 97.13 ± 5.30ab | 16.00 ± 1.08c | 29.23 ± 0.94b |

| Group number |

Amylase [U l-1] |

Lipase [U l-1] |

Elastase [ng g-1d.w.] |

Malondialdehyde [nmol ml-1] |

| Group #1 (Control) | 681.57 ± 17.15d | 187.95 ± 9.43ab | 1610.35 ± 37.65a | 3.71 ± 0.17bc |

| Group #2 | 554.09 ± 19.01b | 183.17 ± 6.97a | 1627.77 ± 18.78a | 3.52 ± 0.23abc |

| Group #3 | 581.72 ± 8.71bc | 199.14 ± 6.52b | 1615.24 ± 77.14a | 3.65 ± 0.21bc |

| Group #4 | 384.03 ± 13.46a | 178.29 ± 4.67a | 1565.59 ± 35.74a | 3.84 ± 0.14c |

| Group #5 | 588.87 ± 9.52c | 189.56 ± 5.11ab | 1613.19 ± 102.99a | 3.54 ± 0.26abc |

| Group #6 | 601.00 ± 18.78c | 259.32 ± 10.30d | 1628.57 ± 48.69a | 3.20 ± 0.22a |

| Group #7 | 584.25 ± 20.00c | 226.29 ± 12.41c | 1625.43 ± 63.76a | 3.46 ± 0.29ab |

| Group #8 | 607.20 ± 27.95c | 221.79 ± 8.79c | 1587.04 ± 52.26a | 3.21 ± 0.23a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).