Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Iodine Content in Rats’ Diets

2.2. Iodine in Selected Tissues

2.3. Selected Biochemical Parameters

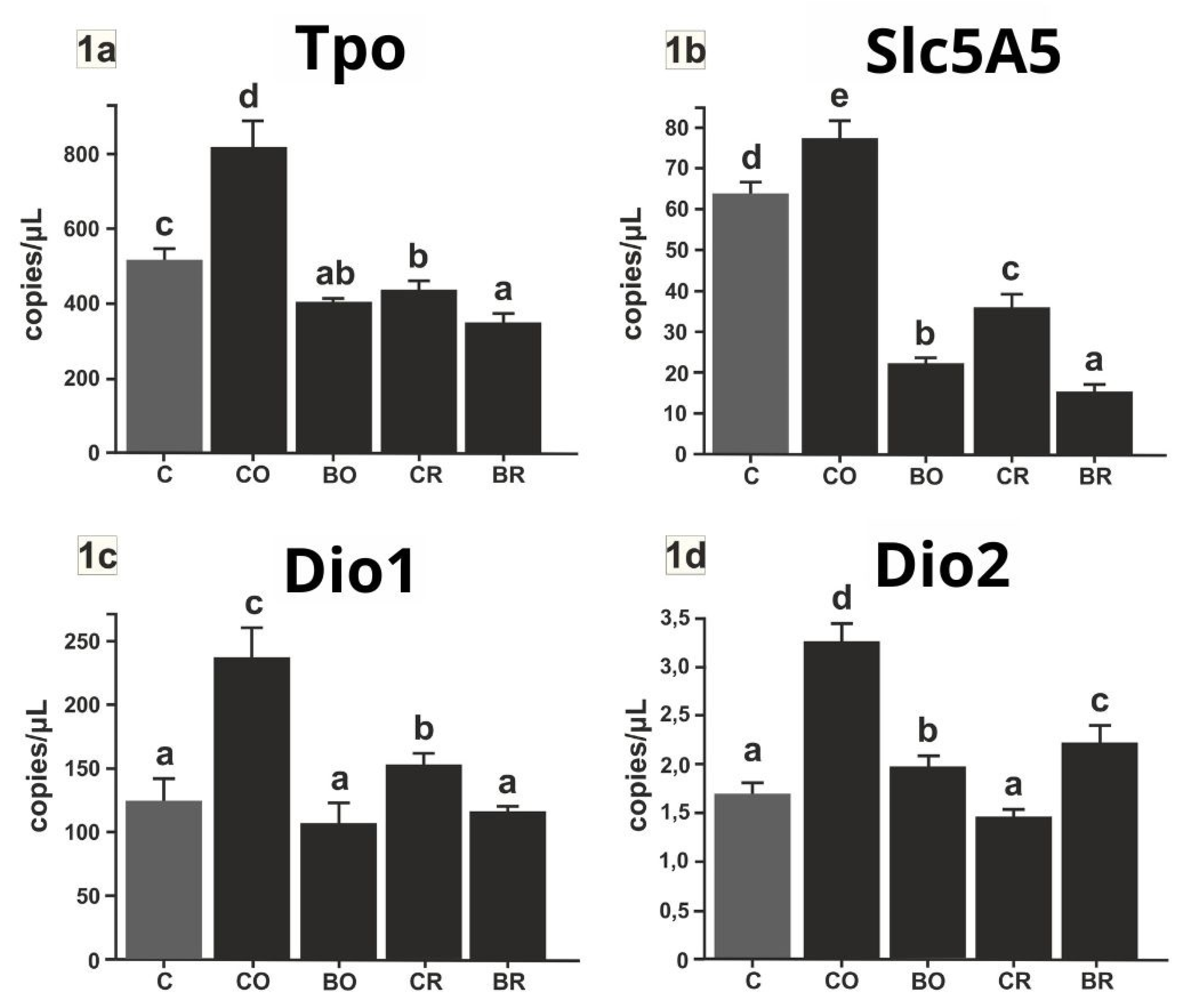

2.4. Evaluation of Tpo, Slc5a5, Dio1, and Dio2 Gene Expression Among Experimental Groups

3. Discussion

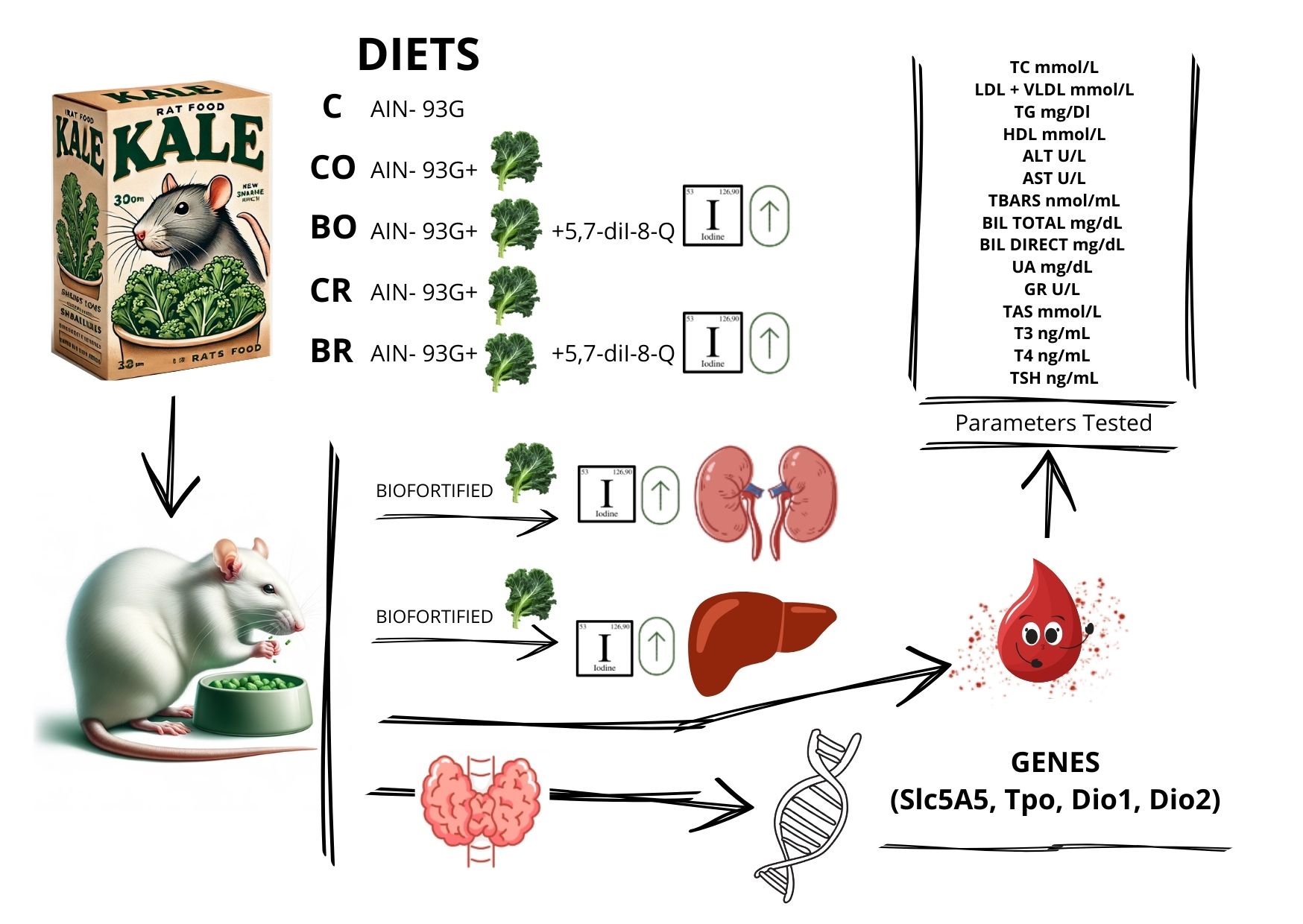

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Animal Study

4.3. Analysis of Iodine in Animal Tissues

4.4. Analysis in Serum and Blood

4.5. Gene Expression Profiling

4.5.1. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

4.5.2. Digital PCR Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Braun, D.; Schweizer, U. Thyroid Hormone Transport and Transporters. Vitam. Horm. 2018, 106, 19–44. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Peeters, R.P.; Flach, W.; de Rooij, L.J.; Yildiz, S.; Teumer, A.; et al. Novel (Sulfated) Thyroid Hormone Transporters in the Solute Carrier 22 Family. Eur. Thyroid J. 2023, 12, . [CrossRef]

- Ahad, F.; Ganie, S.A. Iodine, Iodine Metabolism and Iodine Deficiency Disorders Revisited. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 14, 13–17.

- Visser, T.J. Regulation of Thyroid Function, Synthesis, and Function of Thyroid Hormones. In Endocrinology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–32.

- Zhang, L.; Shang, F.; Liu, C.; Zhai, X. The Correlation Between Iodine and Metabolism: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1346452. [CrossRef]

- Hatch-McChesney, A.; Lieberman, H.R. Iodine and Iodine Deficiency: A Comprehensive Review of a Re-Emerging Issue. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3474. [CrossRef]

- Baldassano, S.; Di Gaudio, F.; Sabatino, L.; Caldarella, R.; De Pasquale, C.; Di Rosa, L.; et al. Biofortification: Effect of Iodine Fortified Food in the Healthy Population, Double-Arm Nutritional Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 871638. [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, K.K.; Smoleń, S.; Wisła-Świder, A.; Kowalska, I.; Kiełbasa, D.; Pitala, J.; et al. Kale (Brassica oleracea L. var. sabellica) Biofortified with Iodoquinolines: Effectiveness of Enriching with Iodine and Influence on Chemical Composition. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 323, 112519. [CrossRef]

- Le, S.N.; Porebski, B.T.; McCoey, J.; Fodor, J.; Riley, B.; Godlewska, M.; et al. Modelling of Thyroid Peroxidase Reveals Insights into Its Enzyme Function and Autoantigenicity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142615. [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; Modenutti, C.P.; Gil Rosas, M.L.; Peyret, V.; Geysels, R.C.; Bernal Barquero, C.E.; et al. A Novel SLC5A5 Variant Reveals the Crucial Role of Kinesin Light Chain 2 in Thyroid Hormonogenesis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 1867–1881. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M. Biofortified Diets Containing Algae and Selenised Yeast: Effects on Growth Performance, Nutrient Utilization, and Tissue Composition of Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata). Front. Physiol. 2022, 12, . [CrossRef]

- Šamec, D.; Urlić, B.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) as a Superfood: Review of the Scientific Evidence Behind the Statement. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2411–2422. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, W.; Iqra; Afzal, F.; Rahim, M.A.; Abdul Rehman, A.; Faiz ul Rasul, H.; et al. Industrial Applications of Kale (Brassica oleracea var. sabellica) as a Functional Ingredient: A Review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 489–501. [CrossRef]

- Nestel, P.; Bouis, H.E.; Meenakshi, J.V.; Pfeiffer, W. Biofortification of Staple Food Crops. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1064–1067. [CrossRef]

- Pesce, L.; Kopp, P. Iodide Transport: Implications for Health and Disease. Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, . [CrossRef]

- De Bhailis, Á.M.; Kalra, P.A. Hypertension and the Kidneys. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 83, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Balzer, M.S.; Rohacs, T.; Susztak, K. How Many Cell Types Are in the Kidney and What Do They Do? Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2022, 84, 507–531. [CrossRef]

- Piątkowska, E.; Kopeć, A.; Bieżanowska-Kopeć, R.; Pysz, M.; Kapusta-Duch, J.; Koronowicz, A.A.; et al. The Impact of Carrot Enriched in Iodine Through Soil Fertilization on Iodine Concentration and Selected Biochemical Parameters in Wistar Rats. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152680. [CrossRef]

- Kopeć, A.; Piątkowska, E.; Bieżanowska-Kopeć, R.; Pysz, M.; Koronowicz, A.; Kapusta-Duch, J.; et al. Effect of Lettuce Biofortified with Iodine by Soil Fertilization on Iodine Concentration in Various Tissues and Selected Biochemical Parameters in Serum of Wistar Rats. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 14, 479–486. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Chai, C.; Qian, Q.; Li, C.; Chen, Q. Determination of Bromine and Iodine in Normal Tissues from Beijing Healthy Adults. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1997, 56, 225–230. [CrossRef]

- Fordyce, F.M.; Stewart, A.G.; Ge, X.; Jiang, J.Y.; Cave, M. Environmental Controls in IDD: A Case Study in the Xinjiang Province of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2003, 293, 201–215.

- Weng, H.-X.; Yan, A.-L.; Hong, C.-L.; Qin, Y.-C.; Pan, L.; Xie, L.-L. Biogeochemical Transfer and Dynamics of Iodine in a Soil-Plant System. Environ. Geochem. Health 2009, 31, 401–411. [CrossRef]

- Waśniowska, J.; Leszczyńska, T.; Kopeć, A.; Piątkowska, E.; Smoleń, S.; Krzemińska, J.; et al. 7-Diiodo-8-Quinolinol: The Influence of Heat Treatment on Iodine Level, Macronutrient Composition, and Antioxidant Content. Molecules 2023, 28, 3988.

- Aviram, M.; Fuhrman, B. Wine Flavonoids Protect Against LDL Oxidation and Atherosclerosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 957, 146–161. [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, G.S.; London, R.; Manimekalai, S.; Nair, P.P.; Goldstein, P. α-Tocopherol and Serum Lipoproteins. Lipids 1981, 16, 223–227. [CrossRef]

- Gertig, H.; Przysławski, J. Bromatologia. Zarys Nauki o Żywności i Żywieniu; PZWL: Warszawa, Poland, 2007; pp. 121–123.

- Noonan, W.P.; Noonan, C. Legal Requirements for “Functional Foods” Claims. Toxicol. Lett. 2004, 150, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Piątkowska, E.; Kopeć, A.; Leszczyńska, T. Antocyjany—Charakterystyka, Występowanie i Oddziaływanie na Organizm Człowieka. Żywność Nauka Technologia Jakość 2011, 18, 22–35.

- Użarowska, M.; Surman, M.; Janik, M. Dwie Twarze Cholesterolu: Znaczenie Fizjologiczne i Udział w Patogenezie Wybranych Schorzeń. Kosmos 2018, 67, 375–390.

- Mohammadi, N.; Farrell, M.; O’Sullivan, L.; Langan, A.; Franchin, M.; Azevedo, L.; et al. Effectiveness of Anthocyanin-Containing Foods and Nutraceuticals in Mitigating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Health-Related Biomarkers: A Systematic Review of Animal and Human Interventions. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 3274–3299. [CrossRef]

- Herlina, F.; Hayati, F.; Wijaya, D.P.; Belinda, R. Antihyperlipidemia Activity of Ethyl Acetate Fraction from Melinjo (Gnetum gnemon Linn.) Leaf in White Male Wistar Rats Induced by Propylthiouracil. Molecules 2024, 29, 3748.

- Bowen-Forbes, C.; Armstrong, E.; Moses, A.; Fahlman, R.; Koosha, H.; Yager, J.Y. Broccoli, Kale, and Radish Sprouts: Key Phytochemical Constituents and DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 4266. [CrossRef]

- Ruhee, R.T.; Ma, S.; Suzuki, K. Protective Effects of Sulforaphane on Exercise-Induced Organ Damage via Inducing Antioxidant Defense Responses. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 136. [CrossRef]

- El-Shahat, W.; El-Adl, M.; Hamed, M.; El-Saedy, Y. The Protective Effect of Sulforaphane in Rats Fed on High Cholesterol High Fructose Diets. Mansoura Vet. Med. J. 2020, 21, 85–90.

- Chen, X. Protective Effects of Quercetin on Liver Injury Induced by Ethanol. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2010, 6, 135–141.

- Alkandahri, M.Y.; Pamungkas, B.T.; Oktoba, Z.; Shafirany, M.Z.; Sulastri, L.; Arfania, M.; et al. Hepatoprotective Effect of Kaempferol: A Review of the Dietary Sources, Bioavailability, Mechanisms of Action, and Safety. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 2023, 1387665. [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Shi, R.; Qi, T.; Yin, H.; Mei, L.; Han, X.; et al. A Comparative Study on the Effects of Excess Iodine and Herbs with Excess Iodine on Thyroid Oxidative Stress in Iodine-Deficient Rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014, 157, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J.W.; Zhang, Y.; Talalay, P. Broccoli Sprouts: An Exceptionally Rich Source of Inducers of Enzymes That Protect Against Chemical Carcinogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 10367–10372. [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.L.; Boulware, S.; Fields, T.; McIvor, E.; Powell, K.L.; DiGiovanni, J.; et al. Sulforaphane Induces Phase II Detoxication Enzymes in Mouse Skin and Prevents Mutagenesis Induced by a Mustard Gas Analog. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 266, 439–442. [CrossRef]

- Vitek, L.; Hinds, T.D., Jr.; Stec, D.E.; Tiribelli, C. The Physiology of Bilirubin: Health and Disease Equilibrium. Trends Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 315–328. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Su, Y.; Zhang, J.-A.; Fang, M.; Liu, X.; Jia, X.; et al. Inverse Association Between Iodine Status and Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study in a Chinese Moderate Iodine Intake Area. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 3691–3701.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Yuan, M.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H. Gout and Diet: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms and Management. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3525. [CrossRef]

- Kumata, H.; Wakui, K.; Suzuki, H.; Sugawara, T.; Lim, I. Glutathione Reductase Activity in Serum and Liver Tissue of Human and Rat with Hepatic Damage. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 1975, 116, 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Bastani, A.; Rajabi, S.; Daliran, A.; Saadat, H.; Karimi-Busheri, F. Oxidant and Antioxidant Status in Coronary Artery Disease. Biomed. Rep. 2018, 9, 327–332. [CrossRef]

- Vairetti, M.; Di Pasqua, L.G.; Cagna, M.; Richelmi, P.; Ferrigno, A.; Berardo, C. Changes in Glutathione Content in Liver Diseases: An Update. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 364. [CrossRef]

- Socha, K.; Klimiuk, K.; Naliwajko, S.K.; Soroczyńska, J.; Puścion-Jakubik, A.; Markiewicz-Żukowska, R.; et al. Dietary Habits, Selenium, Copper, Zinc and Total Antioxidant Status in Serum in Relation to Cognitive Functions of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 287. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.E.-A.M.; Abbas, A.M.; El Wakil, G.A.; Elsamanoudy, A.Z.; El Aziz, A.A. Effect of Chronic Excess Iodine Intake on Thyroid Function and Oxidative Stress in Hypothyroid Rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012, 90, 617–625. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X. Thyroid Function Alterations Attributed to High Iodide Supplementation in Maternal Rats and Their Offspring. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2018, 47, 89–97. [CrossRef]

- Galanty, A.; Grudzińska, M.; Paździora, W.; Służały, P.; Paśko, P. Do Brassica Vegetables Affect Thyroid Function? — A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3988. [CrossRef]

- Katz, E. Indole-3-Carbinol: A Plant Hormone Combatting Cancer. Biol. Chem. 2018, 100, 34–41.

- NCBI. DIO2 Iodothyronine Deiodinase 2 [Homo sapiens (Human)]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/1734 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Lavado-Autric, R.; Calvo, R.M.; de Mena, R.M.; de Escobar, G.M.; Obregon, M.J. Deiodinase Activities in Thyroids and Tissues of Iodine-Deficient Female Rats. Endocrinology 2012, 154, 529–536. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, P.G. Components of the AIN-93 Diets as Improvements in the AIN-76A Diet. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 838S–841S. [CrossRef]

- Krzemińska, J.; Piątkowska, E.; Kopeć, A.; Smoleń, S.; Leszczyńska, T.; Koronowicz, A. Iodine Bioavailability and Biochemical Effects of Brassica oleracea var. sabellica L. Biofortified with 8-Hydroxy-7-Iodo-5-Quinolinesulfonic Acid in Wistar Rats. Nutrients 2024, 16, 213578. [CrossRef]

- Friedewald, W.T.; Levy, R.I.; Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of the Concentration of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Plasma, Without Use of the Preparative Ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for Lipid Peroxides in Animal Tissues by Thiobarbituric Acid Reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [CrossRef]

| Iodine content | C | CO | BO | CR | BR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| liver mg/kg d.m |

0.12a±0.01 | 0.11a ±0.01 | 0.15b±0.00 | 0.11a±0.00 | 0.14b±0.01 |

| kidney mg/kg d.m |

0.14b±0.00 | 0.13ab±0,01 | 0.19c±0.01 | 0.11a±0.01 | 0.17c±0.01 |

| C | CO | BO | CR | BR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC mmol/L | 3.01b±0.19 | 2.81ab±0.16 | 2.61ab±0.19 | 2.61ab±0.14 | 2.48a±0.11 | |

| LDL + VLDL mmol/L | 1.12a±0.13 | 1.07a±0.12 | 1.06a±0.13 | 1.07a±0.08 | 0.93a±0.11 | |

| TG mg/Dl | 113.75b±16.53 | 122.92b±16.99 | 103.90ab±12.36 | 83.44ab±12.56 | 64.72a±6.44 | |

| HDL mmol/L | 1.89b±0.06 | 1.78ab±0.11 | 1.56a±0.09 | 1.54a±0.10 | 1.57a±0.11 | |

| ALT U/L | 10.13b±3.02 | 8.20b±1.00 | 2.64a±0.27 | 3.96a±0.43 | 2.62a±0.26 | |

| AST U/L | 12.18b±2.18 | 8.00ab±3.00 | 8.95ab±0.60 | 8.97ab±0.87 | 4.74a±0.55 | |

| TBARS nmol/mL | 554.52b±9.67 | 535.31ab±31.40 | 518.56ab±27.46 | 474.93a±22.34 | 469.96a±15.85 | |

| BIL TOTAL mg/dL | 0.60c±0.13a | 0.19ab±0.04 | 0.14a±0.04 | 0.38b±0.09 | 0.22ab ±0.05 | |

| BIL DIRECT mg/dL | 1.34ab±0.24 | 1.50ab±0.43 | 0.62a±0.19 | 0.80a±0.28 | 1.89b±0.28 | |

| UA mg/dL | 2.80b±0.37 | 2.23ab±0.41 | 1.95ab±0.17 | 1.89ab±0.29 | 1.72a±0.26 | |

| GR U/L | 375.72a±72.74 | 348.31a±61.69 | 391.91a±43.02 | 378.96a±52.54 | 331.12a±50.32 | |

| TAS mmol/L | 0.88a±0.07 | 0.86a±0.03 | 0.92a±0.03 | 0.98a±0.03 | 0.95a±0.04 | |

| T3 ng/mL | 3.81ab±0.08 | 3.92b±0.06 | 3.75ab±0.06 | 3.68a±0.04 | 3.85ab±0.02 | |

| T4 ng/mL | 2.75a±0.22 | 2.87a±0.17 | 2.26a±0.25 | 2.59a±0.42 | 2.48a±0.20 | |

| TSH ng/mL | 2.18b±0.06 | 2.02a±0.04 | 2.00a±0.04 | 2.10ab±0.05 | 2.09ab±0.05 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).