1. Introduction

Apolipoprotein B (apoB) is responsible for carrying lipids in plasma, including cholesterol, and is the primary apolipoprotein of chylomicrons, very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles. Its measurement is commonly used to detect the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) [

1,

2]. Apolipoprotein B100 (apoB100), the major protein component of LDL, is a ligand for the LDL receptor (LDLR) [

3]. Mutations in apoB100 or in LDLR cause familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), an autosomal dominant disease that is characterized by a marked increase in LDL-cholesterol (LDLc) and a higher risk of CVD [

4]. However, apoB levels outperform those of LDLc as a biomarker for CVD [5-8]. Thus, apoB is the preferred primary indicator in clinical care to estimate the CVD risk attributable to apoB lipoproteins and the efficacy of lipid-lowering therapies to reduce this risk [

6].

Proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin 9 (PCSK9) is the 9

th member of a family of secretory proteases implicated in various physiological and pathological functions [

9,

10]. The implication of PCSK9 in CVD became apparent when it was shown that gain-of-function (GOF) variants are associated with significantly higher LDLc levels [

11]. The underlying mechanism was resolved when it was realized that in a non-enzymatic fashion the hepatocyte-derived circulating PCSK9 enhances the degradation of the liver LDLR in endosomes/lysosomes [

12,

13] leading to decreased clearance of apoB-containing lipoproteins and higher LDLc and apoB plasma levels [

14].

The

APOB gene is located on the short arm of human chromosome 2 (2p24.1) and spans 43 kb including 29 exons and 28 introns. It encodes a very large hydrophobic protein composed of 4563 amino acids (aa; including a 27 aa signal peptide) [

3,

15,

16]. Recently, two cryo-electron microscopy structures of apoB100 on LDL were reported [

17,

18]. One of these revealed the detailed structure of apoB100 on LDL bound to the LDLR, including high-resolution structures of the interfaces between apoB100 and LDLR [

17]. These data also led to a better structural understanding of known loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in either apoB100 or LDLR associated with high levels of LDLc and located at the LDL-LDLR interface [

17]. Circulating human apoB consists of two isoforms: apoB100 derived from hepatocytes (primary source) and small intestine, as well as an intestinal-specific apoB48 resulting from mRNA editing. ApoB100 (aa 28-4563; molecular weight ~550 kDa) and apoB48 (aa 28-2179; molecular weight ~264 kDa) correspond to 100% and 48% of the molecular weight of full length apoB100 protein, respectively. ApoB100 is associated with VLDL, IDL and LDL, while apoB48 is found only in chylomicrons [

19].

ApoB is an important marker for CVD risk since it is found in atherogenic lipoproteins particles like LDL. Elevated circulating apoB levels are directly associated with hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis. Variants in

APOB are the second most frequent (14%) cause of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), whereas 67% and 2% are attributed to variants in the

LDLR and

PCSK9 genes, respectively [

11,

20,

21]. The most common variants in the

APOB gene occurs in the LDLR-binding domain and affect its ability to bind to the LDLR and to reduce LDLc clearance from the blood. Indeed, lipoprotein particles with LOF variants of apoB cannot be effectively removed from the blood [

22], resulting in very high levels of circulating LDLc and increasing the risk of atherosclerosis and heart attack. Treatment of FH patients involves a combination of cholesterol-lowering medications, such as statins and PSCK9 inhibitors, as well as lifestyle changes [

23,

24].

In contrast, familial hypobetalipoproteinemia (FHBL) is characterized by abnormally low levels of circulating LDLc and apoB. FHBL results from mutations in the genes encoding Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein (MTP) [

25,

26] or apoB, which are essential for producing and assembling lipoproteins [

27]. LOF

APOB mutations most often result from deletions or substitutions that cause premature termination of

APOB mRNA translation, leading to truncated, non-functional proteins and low LDLc [

28,

29,

30]. In humans, various truncated apoB forms have been reported, ranging in molecular weight from 9% (apoB9) to 89% (apoB89) of the full length apoB100 [

29,

31,

32,

33]. It has been shown that the C-terminal truncation of apoB affects the size of the resulting apoB-associated lipoproteins and their fate. Indeed a 10 % decrease in apoB’s length results in a 13% decrease in the core density of lipoproteins, indicating that lipid recruitment by apoB is progressively reduced by its C-terminal truncation, which can affect protein stability [

34,

35,

36]. The length of the C-terminal segment of apoB affects its secretion, as only truncated forms longer than 27% (apoB27) can be efficiently secreted into the plasma [

37,

38].

In the present study, we recently identified family members that did not present variants in either LDLR or PCSK9 but that exhibited very low circulating cholesterol levels. Analyses of their plasma lipid profiles revealed that these subjects had exceedingly low levels of LDLc without affecting their lipoprotein particle size. Sequencing of the APOB gene in a control (unaffected sister) and three affected family members (father, son and daughter) revealed a single heterozygote deletion of an adenosine in exon 3 at position 1268. This novel deletion introduces a reading frame shift at glutamine 380 resulting in a stop codon at aa position 397. Such C-terminally truncated apoB leads to a variant protein spanning ~9% (397 aa; herein called apoB9) of the full-length protein (aa 28-4563). Expression of apoB9 in human hepatocyte IHH cells, revealed an intracellular form with an apparent molecular size of ~60 kDa, which does not exit the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and hence is not secreted into the media. These results suggest that the low levels of circulating apoB (-68%, estimated by proteomics) in the affected family members, likely modify their risk of developing CVD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture, Transfections

Native human hepatocyte IHH cells were grown in William’s Medium (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; GIBCO BRL) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Sigma, MA, USA). Cells were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2. Cells were seeded in 12 well plates at a density of 0.6x106 cells per well and co-transfected with equimolar quantities of each plasmid using FuGene HD, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

2.3. Cell Treatments

Proteins were extracted in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P40 and 0.25% Na deoxycholate) with a complete cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma, MA, USA). 30-50 mg proteins or 2 to 5 mL of plasma were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF (EMD Millipore,Toronto, ON, Canada) membranes. After blocking in 5% skim milk for 1h, membranes were incubated overnight with primary and secondary antibodies according to the manufacturer’s recommendations: anti-V5 (Invitrogen, ON, Canada #46-0705,1/5000) and anti-HA (Abcam, Toronto, ON, Canada #ab128131 [1:5000]) and anti-human apoB (Sigma, MA, USA #A178467, [1:10000]). The antigen-antibody complexes were visualized using appropriate HRP conjugated secondary [1:10000] antibodies and an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (ECL; Amersham) [

39,

40].

2.2. Western Blot Analysis and Antibodies Used

Twenty four hours post-transfection, cells were washed in serum-free medium followed by an additional 24h with fresh media alone (non treated, NT) or media with protease inhibitors. the cell were then lysed in RIPA 1X buffer and analysed on SDS-PAGE: MG132: 1 mM, Lactacystin: 30 mM, Bafilomycin: 0.1 mM, Amonium Chloride: 10 mM, Chloroquine: 50 mM,).

2.4. Glycosidase Treatment.

Proteins (30 to 50 mg) were digested for 90 min at 37°C with endoglycosidase H (endo H; P0702L) or endoglycosidase F (endo F; P0705S) as recommended by the manufacturer (New England BioLabs, ON, Canada).

2.5. Plasma Collection and Circulating Cholesterol Measurement

Blood was collected from 16 h fasting patients and the plasma was obtained by centrifugation at 3000 x g for 15 min. Plasma total cholesterol (TC) and trigycerides (TG) were determined using the Infinity reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ON, Canada). For lipoprotein profiles, 0.3 ml was analyzed by FPLC on a Superose 6 column (Pharmacia, Stockholm, Sweden) with a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min [

41].

2.6. lipoprotein Profiling and Lipoprotein Size Test.

Plasma from patients (20 mL) were subjected to High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Triglyderides and cholesterol were then determined in each liprotein particle. The size of lipoproteins were determined using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (LipoSEARCH, Gunma, Japan). The test measures the distinct NMR signals emitted by lipid methyl groups on different lipoprotein particles. The amplitudes of signals were used to calculate the size distribution of lipoprotein particles, e.g., VLDL, IDL, LDL, and HDL subfractions.

2.7. Lipidomics

Targeted lipidomics analysis was performed as described in the Agilent application note (

https://www.agilent.com/search/?Ntt=RA44413.1612962963). Briefly, samples were extracted in triplicates with (1:10 v:v) extraction solvent butanol:MeOH (1:1) containing 1% (v:v) each: 10x diluted Equisplash internal standard mix (Sigma), 1 mg/ml cholesterol-d7, 1 mg/ml acetylcarnitine-d3 and 5 mg/ml docosahexaenoic acid-d5 (Cayman Chemical). The samples were sonicated for 5 mins and centrifuged 21000 x g for 1 min room temperature (23°C). 80 mL of each sample supernatants were used for the LC-MS analysis. UPLC-MRM-MS analyses were performed using Agilent 1290 LC with 16 mins gradient (A): 0.1% formic acid, 10 mM ammonium formate in 5:3:2 water: acetonitrile: 2-propanol, (B): 0.1% formic acid, 10 mM ammonium formate in 1:9:90 water: acetonitrile: 2-propanol at 400 mL/min flow rate using Zorbax eclipse plus C18 RRHD 100 x 2.1 mm 1.8 um column (Agilent) heated to 45°C. 1 uL injection volumes were used for each run. Data were acquired using Agilent 6495A mass spectrometer and were analyzed using MassHunter software (Agilent).

2.8. Proteomics

Targeted proteomics analysis was performed using PeptiQuant Plus Proteomics Kit (MRM Proteomics) as described previously [

42,

43]. Briefly, 10 ml of plasma samples in quadruplicates were supplemented with 1 ml of 1 M ABC, reduced with 1 ml of 0.1 M DTT for 30 mins at 37°C, alkylated with 1 ml of 0.3 M iodoacetamide for 30 mins at 37°C. Proteins were precipitated with addition of 90 ml acetonitrile, samples were centrifuged for 1 min at 21000 x g at room temperature (23°C), pellets were resuspended in 700 ml of 50 mM ABC, and proteins were digested with 70 ml of 1 mg/ml of trypsin (~1:10 enzyme:protein) (Worthington) overnight at 37°C. Trypsin digests were acidified with 7.7 ml formic acid and centrifuged for 1 min at 21,000 x g at room temperature. Aliquots of supernatants were supplemented with SIS peptide mix and analyzed by LC-MS. UPLC-MRM-MS analyses were performed using Sciex QTrap 6500+ triple quadrupole mass spectrometer supplemented with Shimadzu Nexera UPLC system. Chromatography was performed using 30 mins gradient 0-30% B (A): 0.1% formic acid, (B): 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile at 200 mL/min flow rate using Zorbax eclipse plus C18 RRHD 150 x 2.1 mm 1.8 mm column (Agilent). MRM transitions for 16 apolipoproteins from the kit protein panel were used in unscheduled acquisition method. 10 ml of 11x diluted SIS peptide mixture from the kit was combined with 12 ml of 50x diluted NAT peptide mixture from the kit or 12 ml of plasma sample tryptic digests, 20 ml was injected for the analysis. Data were analyzed using Sciex Analyst software. Concentration of the SIS peptides were determined from the runs of NAT+SIS peptide mixtures using known NAT peptide concentrations, and concentration of the apolipoprotein peptides were determined from the runs of plasma sample digests+SIS peptide mixtures using calculated SIS peptide concentrations.

2.9. Apolipoprotein B Sequencing

Whole-genome sequencing was performed in all four family members to screen for relevant mutations across all protein-coding genes. PCR-free libraries were prepared from 1µg of genomic DNA using the KAPA HyperPrep library kit (Roche Diagnostics). Size distribution of the final libraries were assessed on high sensitivity DNA bionalyzer and libraries were quantified by quantitative PCR. Libraries were pooled equimolarly and sequenced on a lane of Novaseq S4 (300 cycles) flowcell using paired-end reads (2 x 150 bp). Genomes were sequenced to an average depth of 39x. Reads were aligned to the human genome reference version, GRCh38, using Bowtie2 software in “no-discordant” alignment mode. Variant calling was performed using the Samtools “mpileup” command with default settings. Using annovar software, variant effects were annotated based on the database of non-synonymous SNP functional predictions (dbNSFP) which describes. Non-synonymous variants that were rare were prioritized, with rare being defined as genetic variants with allele frequencies less than 0.001 in all superpopulations within the genome aggregation database (gnomAd v4.1), a human repository of over 800,000 genome and exome sequences. Genetic variants were further filtered based on phenotypic cosegregation within the family.

2.10. Apolipoprotein B9 and B21 Models

PDB files of recently published cryoEM structures of apoB100 on LDL bound to the LDL receptor and legobody [

17] (PDB 9BDT, 9BD1) were downloaded from RCSB PDB. The structures were visualized in UCSF ChimeraX software. The LDL receptor and legobody were removed and regions corresponding to apoB9 (aa 39-380; residues 28-38 are missing in the structure) or apoB21 (aa 39-965) were highlighted.

3. Results

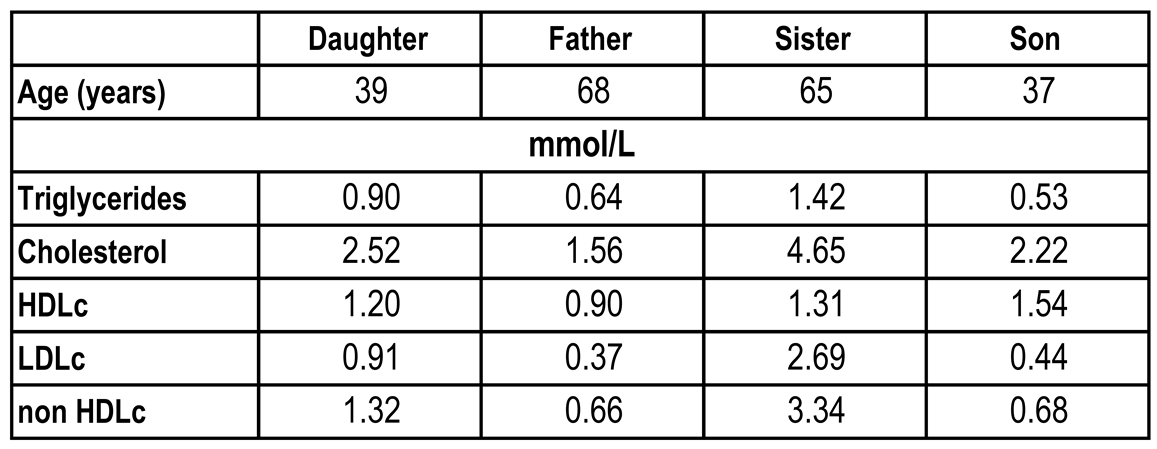

3.1. Identification of a Hypabobetaliproteinema Family Presenting Low LDLc

A 68-year-old Caucasian man visited his primary care physician for a routine evaluation. His lipid profile demonstrated a very low LDLc level of 0.37 mmol/L (

Table 1). The patient was referred to a specialty lipid clinic for further evaluation. His physical examination was essentially normal and revealed no evidence of hepatomegaly.

Cascade screening for low levels of LDLc was performed for first degree relatives (

Table 1). A 39 year old daughter had an LDLc of 0.91 mmol/L and a 37 year old son had an LDLc of 0.44 mmol/L, both being below the 5

th percentile. Both were asymptomatic and in good health. A 65-year-old sister had an LDLc of 2.69 mmol/L, was unaffected and served as a control.

3.2. Plasma LDLc and Apolipoproteins of Family Members

Quantification of the circulating levels of LDLc in fasted family members revealed that compared to the sister the LDLc levels of the father and son were about 6.5-fold lower, whereas the daughter exibited 3.2-fold lower levels (

Table 1). Plasma Western blot analyses revealed reductions in the levels of apoB (-50%) and apoE (-60%) for the father compared to the sister (

Figure 1A). We next used quantitative mass spectrometry to estimate the absolute levels of the plasma concentrations of apoB100, apoC2, apoC3, and apoE of the four family members (

Figure 1B). Overall, the data showed that compared to those of the sister (black bar), the plasma levels of the above lipoproteins are significantly lower for the father, son and daugther.

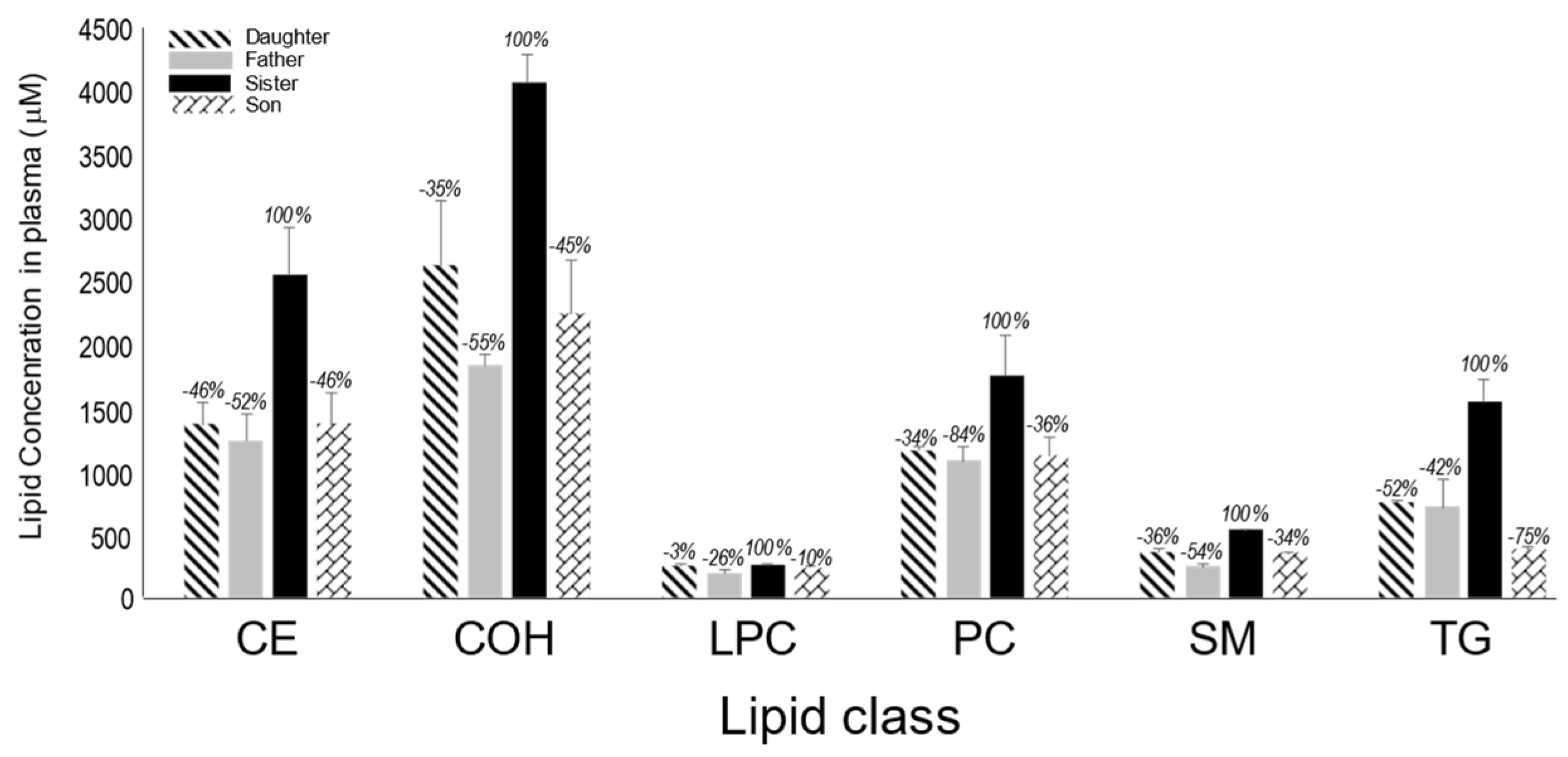

3.3. Lipid Profile of Family Members

We next measured the relative abundance of various lipids in the plasma of all family members (

Figure 2). Here also, except for lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), the levels of cholesteryl ester (CE), non esterified cholesterol (COH), phosphatidylcholine (PC), sphingomyelin (SM) and triglycerides (TG) were all significantly lower in the plasma of the father, son and daughter compared to those of the sister (black bar).

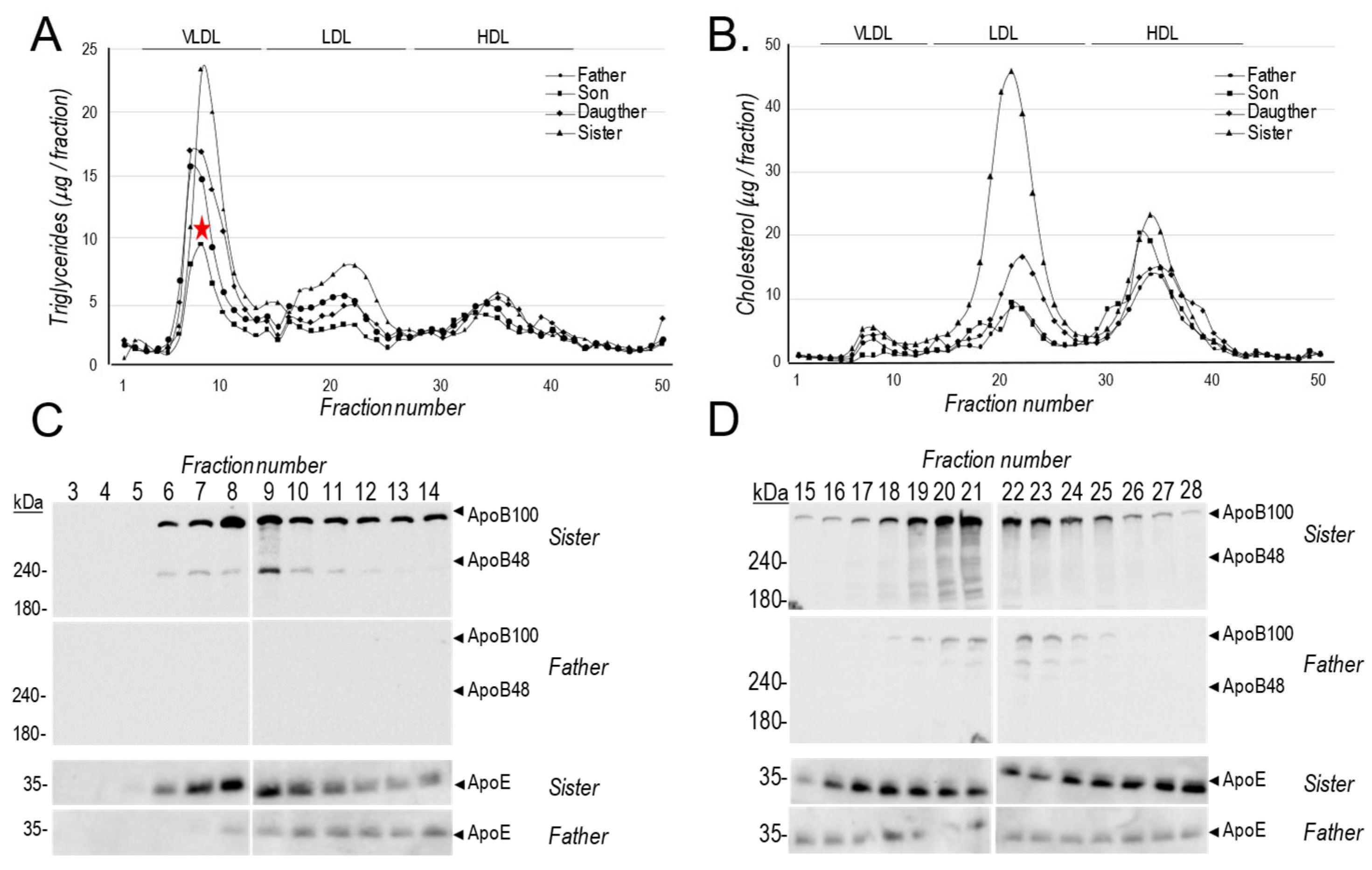

The relative abundance of lipoprotein particles in the plasma of all subjects, was next analysed by Fast Protein Liquid Chromatography (FPLC) where we measured the levels of TG and cholesterol (

Figure 3A, B). While all affected family members exhibited lower LDLc and VLDL triglycerides, we noted that the son has even lower VLDL levels ( ) compared to his sister or father (

Figure 3A). Western blot analyses of apoB and apoE was also performed on fractions corresponding to VLDL and LDL eluting positions for the father and sister (

Figure 3C, D).

In order to obtain a more detailed lipoprotein profiling we solicited the help of a commercial LipoSEARCH service, consisting of a high resolution sensitive gel-filtration High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method, which analyzes the major classes of lipoproteins including chylomicrons (CM), VLDL, LDL and HDL) for cholesterol and TG levels of lipoprotein components contained in 20 subclasses, providing a complete set of profiling data (

https://www.ibl-japan.co.jp/en/business/diagnosis/inspection/) of lipids in plasma.

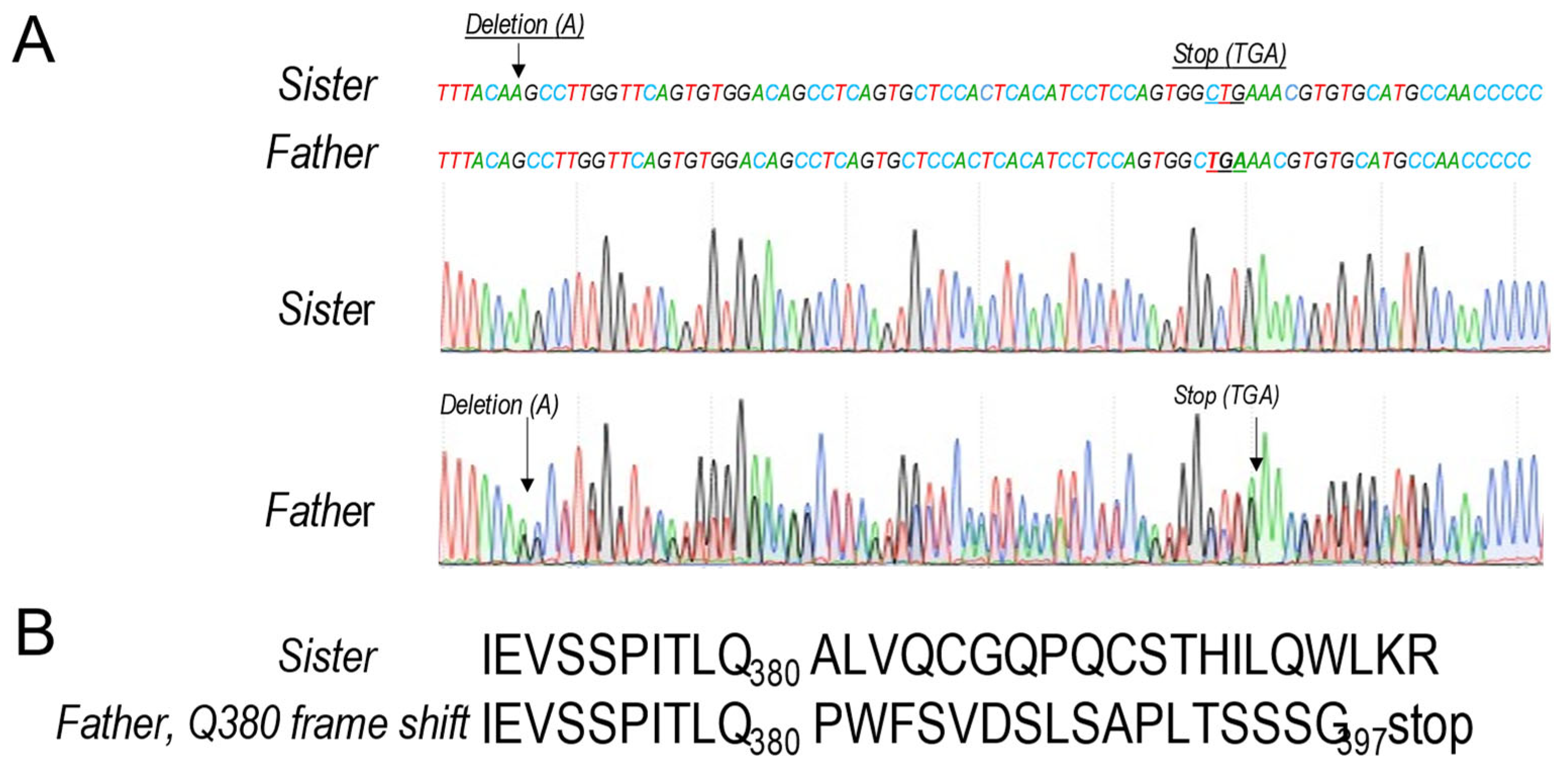

The data confirmed our FPLC comparisons between the father and his sister (

Figure 3) and revealed a ~ 50-80% reduction in the levels of father’s TG (

Figure 4A) and cholesterol (

Figure 4B) within CM, VLDL and LDL lipoprotein particles, but much less reductions in HDL particles (

Figure 4). Interestingly, these lipid reductions had no impact on the size of the lipoprotein particles (

Figure 4C).

We conclude that all the above analyses converge towards the same conlusion that compared to the sister, the three other family members exhibit much lower cholesterol and TG levels in all lipoprotein particles, except for HDL particles, which exhibit a milder phenotype. In addition, we also observed a reduction in the levels of various lipoproteins including apoE, apoC2 and apoC3 and more profoundly for apoB100 (

Figure 1B). Interestingly, compared to the sister, after fasting we could not detect apoB100 or apoB48 in the father’s VLDL particles (

Figure 3C), but smaller amounts of apoB100 were detected in the LDL fractions of the father (

Figure 3D), likely reflecting low levels of circulating apoB100.

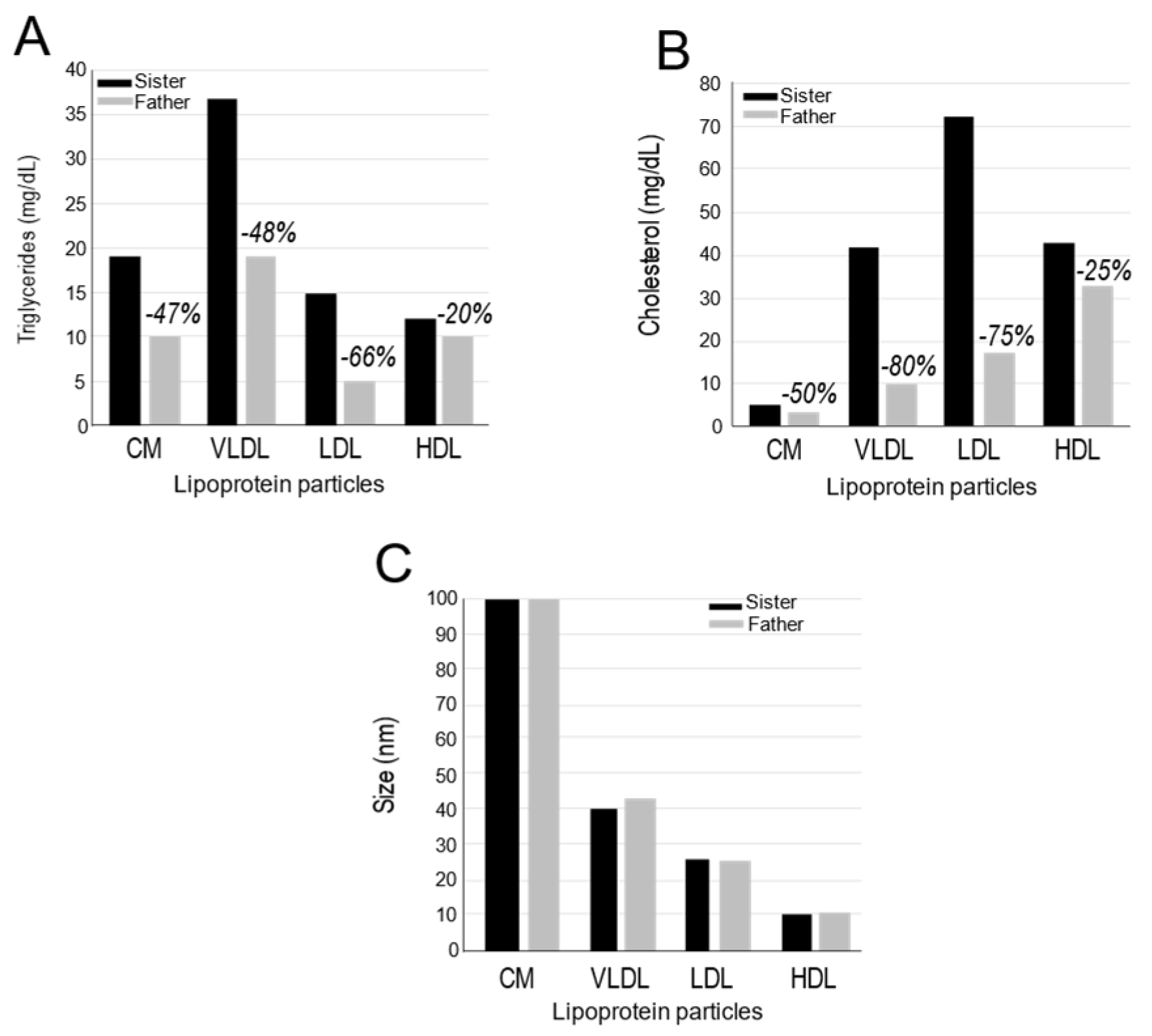

3.4. Genomic Sequencing – Identification of an APOB Single Nucleotide Heterozygote Deletion

The overall phenotype of the affected family members clearly reflected a possible link to genes implicated in the observed large reduction of lipoproteins including apoB100, apoC2, apoC3 and apoE, as well as >50% reductions in the levels of CM, VLDL and LDL lipoprotein particles. To explore the possibility that these variations may be related to lipid regulation or synthesis, we performed DNA sequencing of all family members that revealed no mutations in

LDLR,

MTP, protein disulfide isomerase (

PDI),

APOE,

APOC3 or APOC2. However, the son exhibited a rare coding variant V12I in

APOC2 (rs150887575; APOC2:NM_000483:exon2:c.G34A:p.V12I; gnoMAD MAF=0.0003) within the signal peptide, which is absent from the father, daughter and sister. Thus, co-segregating changes in any of these genes could not explain the observed phenotype. In addition, the low LDLc and TG levels observed in the affected family members, are not a consequence of mutation(s) in the exomes or genes encoding the proprotein convertase

PCSK9, a potent LDLR modulator [

44,

45] or

PCSK7 that regulates VLDL levels

via apoB modulation [

46,

47].

In contrast, while the above results were confirmed upon whole exome sequencing of all family members, a clear single heterozygote variant was identified in all three affected family members but not in the sister’s exomes. Here, a heterozygous frameshift deletion (hg38, chr2: 21032565-CT>C; APOB:NM_000384:exon10:c.1140delA:p.Q380fs) in

APOB co-segregates with all three affected individuals (father, son, daughter) and is absent from the unaffected sister. Notably, Gln

380 is conserved among vertebrates, and the observed variant is absent from gnomAD, with only a single missense carrier (p.Gln380Lys; MAF=6.20x10

-7) reported in gnomAD4.1.0 affecting the same APOB residue out of 806,980 sequenced individuals (

https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/gene/ENSG00000084674?dataset=gnomad_r4).

This conclusion was confirmed by Sanger sequencing, where the sister’s control sequence TTTACA

AGCC, has a single nucleotide Adenine (A) deletion in the sequence of the three affected members, resulting in a truncated TTTACA-GCC sequence (

Figure 5A). Such deletion results in a A381P aa variant followed by a new 17 aa peptide and an early termination codon after Gly

397 (

Figure 5B). Because this results in a variant protein spanning ~9% (aa 28-397; apoB9) of the full-length protein (aa 28-4563), we propose to call it apoB9.

Thus, the heterozygote single nucleotide deletion in the

APOB gene observed in the three affected family members rationalizes the lipoprotein and lipid profile data. However, we also noted that the son had additionally a single nucleotide variant that leads to a V12I variation in the signal peptide. In that context, LOF mutations in the

APOC2 gene lead to severe, inherited hypertriglyceridemia and chylomicronemia [

48] due to the inability to activate lipoprotein lipase (LPL), a key enzyme in triglyceride clearance [

49]. Thus, we presume that the V12I variant would result in a GOF in accord with the lowest VLDL triglyceride levels as observed in the son compared to the rest of the family (

Figure 3A).

3.5. ApoB9 Remains Within the Endoplasmic Reticulum and is not Secreted

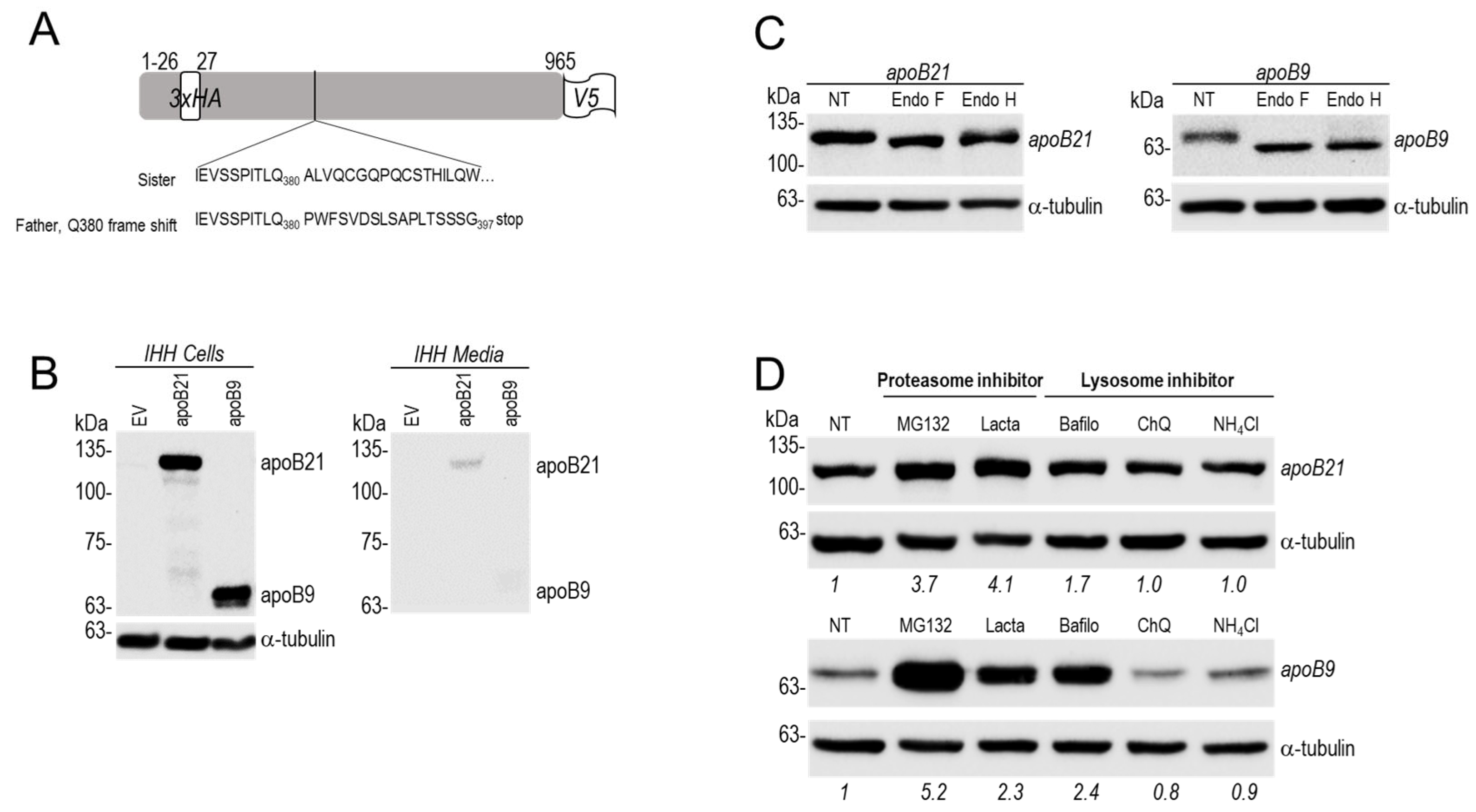

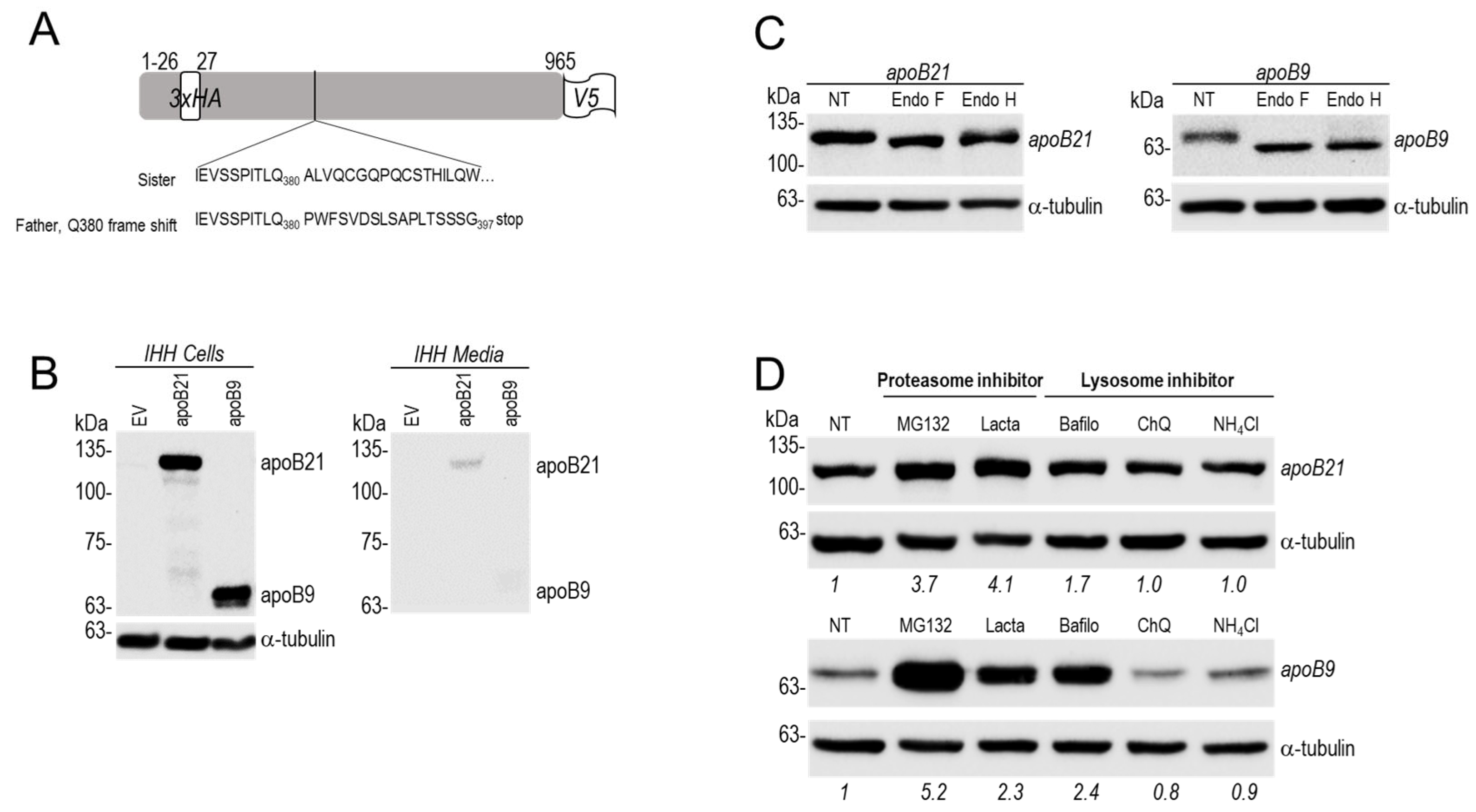

We next aimed to define the possible fate of human apoB9 in hepatocytes. Thus, we generated a cDNA construct coding for apoB21 (21% of full-length protein) doubly tagged with 3xHA just after the signal peptide (26 aa) and with V5 at the C-terminus and cloned in a pIRES-EGFP vector under the control of a CMV promotor, as reported [

46]. To mimic the apoB frame shift observed in affected family members, a single nucleotide deletion was introduced in apoB21 to generate a truncated TTTACA-GCC sequence that would result in an apoB9 protein ending with 17 aa following Gln

380 (

Figure 6A).

We thus analyzed in human hepatocyte IHH cells the expression of cDNAs encoding apoB21 or apoB9 compared to a control empty vector (EV). Western blot data using an HA-tag revealed that while intracellularly both proteins are similarly visible on the gel, only a fraction of apoB21 was secreted into the medium, but apoB9 was absent (

Figure 6B). The latter is clearly visible in cells migrating with an apparent molecular size of ~60 kDa.

We hypothesized that the exit of apoB21 and apoB9 from the ER may be differentially modulated. To support this, we tested the sensitivity of cell extracts containing these proteins to digestion by endoglycosidase H (endo H) and PNGase F (endo F). Endo H cleaves high-mannose and hybrid glycans in the ER but not complex glycans found in the Golgi apparatus. In contrast, endo F cleaves all types of N-linked glycans, including high-mannose, hybrid, and complex glycans, making it suitable for a broader range of deglycosylation [

50]. Using these criteria, endo H resistant forms are mature N-glycosylated proteins and hence reflect the forms that exited the ER. In contrast endo H sensitive forms likely represent proteins that are still in the ER. In both cases endo F treatment would result in non-glycosylated proteins of similar molecular size. The data revealed that intracellular apoB9 is sensitive to endo H digestion but not apoB21 (

Figure 6C). This indicates that difference from apoB21, the apoB9 isoform resides in the ER and hence is not secreted.

It is well known that a fraction of non-lipidated apoB100 is degraded by the proteasome, to regulate the amount of secretion of newly synthesized apoB100. The latter is regulated by the proteasome through an ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway where misfolded or improperly assembled apoB100 is exported from the ER into the cytosol, polyubiquitinated, and subsequently degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). This degradation is a key quality control mechanism that impacts VLDL particle secretion and hepatic TG production [

51]. Factors like MTP inhibition or insufficient lipid availability can lead to apoB100 misfolding and increased proteasomal degradation [

52].

Accordingly, IHH cells expressing apoB21 or apoB9 were treated for 24h with proteasome inhibitors (MG132 and Lactacystin) or alkalinizing agents (Bafilomycin, NH

4Cl or Chloroquine). Western blot analysis of the intracellular apoB proteins revealed that the levels of both proteins are not affected by NH

4Cl or Chloroquine, but are significantly higher in presence of proteasome inhibitors, especially with MG132 for apoB9 (

Figure 6D). Overall, our data suggest that both proteins are partially degraded by the proteasome, but that only apoB9 is not secreted and likely resides in the ER. These results rationalize the low levels of plasma apoB (-68%, estimated by proteomics) in the affected family members who are heterozygote for apoB9 (

Figure 1B).

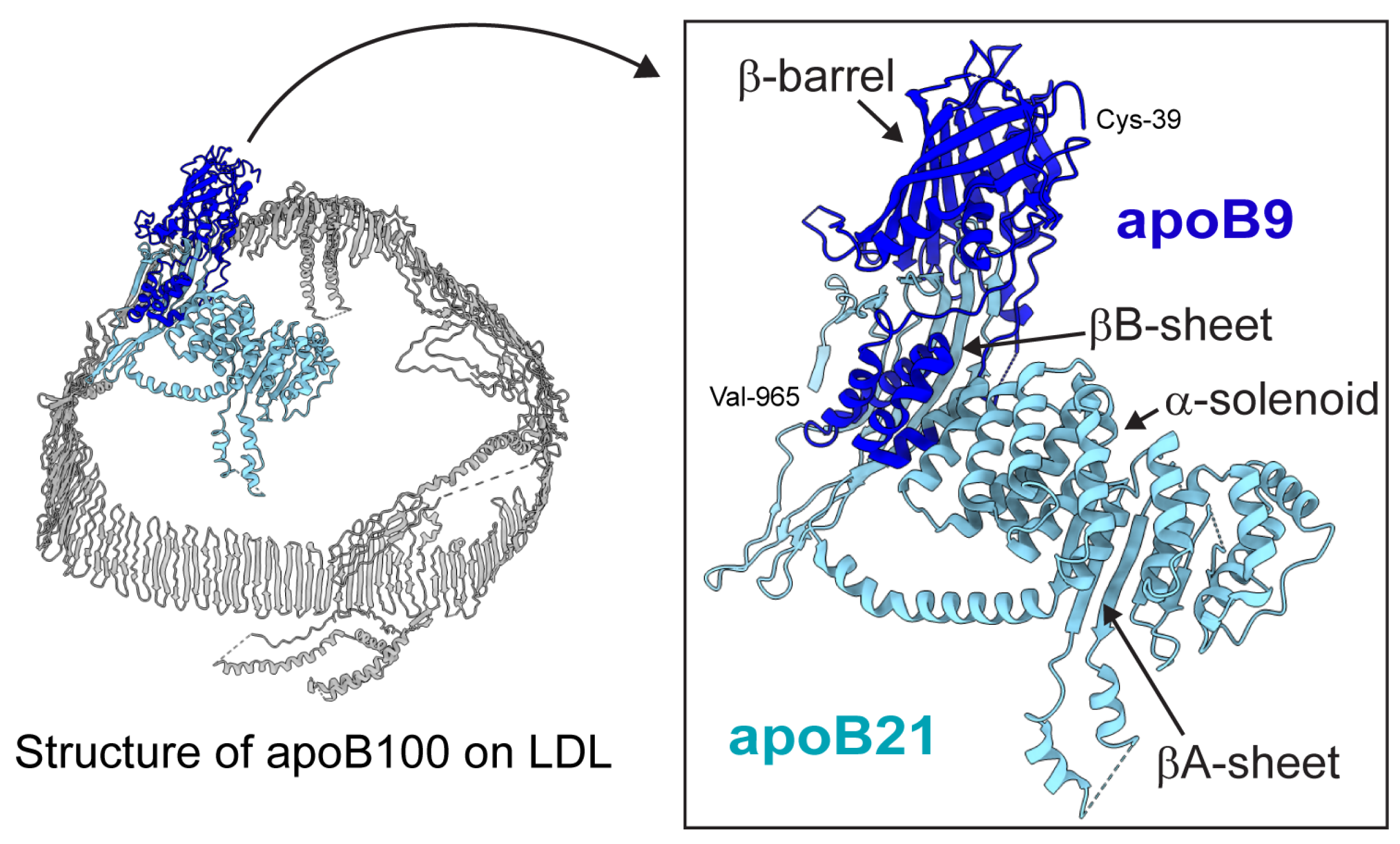

3.6. Molecular Models of apoB9 and apoB21

ApoB9 contains residues 28-380 of mature apoB100 and includes only the β-barrel and the first three helices from the α-solenoid region within the N-terminal βα1 domain of apoB100 (

Figure 7). Importantly, apoB9 lacks the βA- and βB-sheets underlying the β-barrel and α-solenoid that are required for lipid particle formation [

3,

53,

54]. In contrast, apoB21 contains the βA-sheet and part of the βB-sheet and can form lipid particles, although mostly as unstable aggregates [

54]. The availability of lipids and apoB lipid-binding ability affects its secretion efficiency [

55,

56]. This is consistent with our observation that apoB9 was retained in the ER, whereas apoB21 was secreted.

4. Discussion

Mutations in the

APOB gene result in defective forms of the apoB100 protein that is crucial for transporting cholesterol on lipoproteins particles. This leads to the accumulation of LDLc in the bloodstream, thereby increasing the risk of premature CVD. So far, more than 4661 germ line

APOB gene variants were reported, most of which are missense variants (2686; 58%) or result in frameshift mutations (117; 0.03%) (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/?term=%22apoB%22%5BGENE%5D&redir=gene). The

APOB gene comprises 29 exons and the pathogenic mutations are distributed throughout the coding region. Most of these variants are in the C-terminal domain essentially in the last 4 exons of the

APOB gene [

57]. However, heterozygote

APOB gene truncations that cause FHBL, result in an apoB protein that is too short to function properly, leading to low levels of circulating LDLc and are likely protective against CVD.

Familial hypobetalipoproteinemia (FHBL) is an autosomal co-dominant disorder, defined by plasma concentrations of total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol LDL-C and apolipoproteinB100 below the 5

th percentile. The frequency of apoB truncations is reported to be 1:3000. FHBL can be caused by mutations in the two differents genes: (1) the gene coding for the MTP [

25,

26] which is essential for the assembly of apolipoprotein B (apoB)-containing lipoproteins including chylomicrons and VLDL. Its primary role is to facilitate the transfer of lipids, particularly triglycerides, into the lumen of the ER, which is necessary for the proper folding and secretion of apoB-lipoprotein particles. Without MTP, apoB proteins are not efficiently secreted from the liver and intestine. (2) The

APOB gene encodes the essential protein that forms the structural apoB-containing lipoproteins, such as VLDL and LDL. Its role is to mediate the assembly and secretion of these particles from the liver and small intestine by providing the structural framework and a single copy of apoB on each lipoprotein particle. During this process, apoB acts as a docking site for lipids, which are transferred to it by proteins to build the final lipoprotein particle.

LOF

APOB mutations most often result from deletions or substitutions that cause premature termination of

APOB mRNA translation, leading to truncated, non-functional proteins and low LDLc [

28,

29,

30]. In human, various truncated apoB forms were reported, ranging in molecular weight from 9% (apoB9) and 89% (apoB89) of the full length apoB100 have been described [

29,

31,

32,

33]. It has been shown that the C-terminal truncation of apoB affects the size of the resulting apoB-associated lipoproteins and their fate and that lipid recruitment by apoB is progressively reduced by its C-terminal truncation resulting in reduced protein stability [

34,

35,

36]. Only truncated forms longer than 27% (apoB27) were observed to be secreted into the plasma [

37,

38].

Herein, we present evidence for the existence of an apoB9 form in the genome of three family members that exhibit ~70% lower levels of circulating apoB100 and of total and LDLc. We rationalized such low levels by the inability of apoB9 to be secreted from hepatocytes (

Figure 6B), its retention in the ER (

Figure 6C) and its degradation by the proteasome (

Figure 6D).

We thus, wished to provide a structural rationale for our observations. Since apoB9 lacks the critical lipid-binding βA- and βB-sheets (

Figure 7), it likely has poor lipid affinity and cannot form lipid particles. The secretion efficiency of truncated apoB forms correlates with their length and lipid-binding capacity [

55,

56]. For example, apoB18 (aa 28-808) [

36]) and apoB17.6 (aa 28-827), which contain the βA- but not the βB-sheet, are secreted from cultured cells but at a much lower rate than apoB20.5 or apoB21.08 (aa 28-958 and aa 22-983, respectively) [

54]. Notably, secretion of monodisperse and stable particles in cell culture requires the complete βα1 domain (apoB22, aa 28-1027) [

54], which is still in large part in apoB21 (aa 28-965;

Figure 7), likely rationalizing its low secretion levels (

Figure 6B). Altogether, these findings explain why apoB9 is retained in the ER, whereas apoB21 is secreted.

The novel frameshift mutation which we identified in apoB segregates in a dominant manner and due to lifelong reductions in atherogenic proteins, familial hypolipoprotein patients exhibiting such rare protein-truncating variants in the

APOB gene have a 72% reduced risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) [

58]. The principal clinical concern in these patients is a risk for hepatic steatosis, which affects a small minority of individuals [

59]. Some cases of severe liver disease [

60], cirrhosis [

61] and hepatocellular carcinoma [

62] have been reported. Genetic testing is important to determine whether these patients require long term follow up for liver disease compared to PCSK9 loss of function carriers who do not demonstrate any adverse liver complications.

These data suggested that the affected family members identified in this study could be protected against the development of atherosclerosis and various aspects of CVDs. In fact, research has shown that apoB is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks and strokes, than LDLc [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., R.E, and N.G.S.; methodology, R.E, A.E., M.C., E.V.P. and M.R.; data curation, R.E, G.P., M.R., A.T.R., M.S. and N.G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.E., M.S. and N.G.S.; visualization, R.E., M.R., A.T.R, M.S. and N.G.S; supervision, N.G.S.; project administration, N.G.S.; funding acquisition, M.S. and N.G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. .

Funding

This research was funded by a CIHR grants (NGS: # 148363; 191678), a Canada Research Chair in Precursor Proteolysis (N.G.S.: # 950-231335), and an investigator initiator grant from Pfizer (to MS).:

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the expert secretarial help of Jisca Borgela in the preparation of this manuscript. We would also like to thank Myriam Rondeau and Sarah Boissel at the IRCM sequencing facility.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Behbodikhah, J.; Ahmed, S.; Elyasi, A.; Kasselman, L.J.; De Leon, J.; Glass, A.D.; Reiss, A.B. Apolipoprotein B and Cardiovascular Disease: Biomarker and Potential Therapeutic Target. Metabolites 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavinovic, T.; Thanassoulis, G.; de Graaf, J.; Couture, P.; Hegele, R.A.; Sniderman, A.D. Physiological Bases for the Superiority of Apolipoprotein B Over Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Non-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol as a Marker of Cardiovascular Risk. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e025858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrest, J.P.; Jones, M.K.; De Loof, H.; Dashti, N. Structure of apolipoprotein B-100 in low density lipoproteins. J Lipid Res 2001, 42, 1346–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, Y.N.; Warbhe, R.A. Familial Hypercholesterolemia: A Literature Review of the Pathophysiology and Current and Novel Treatments. Cureus 2023, 15, e49121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, E.; Ekpo, E.; Evans, D.; Varughese, E.; Hermel, M.; Jeschke, S.; Hassan, S.; Torkamani, A.; Muse, E.D.; Triffon, D. Apolipoprotein B outperforms low density lipoprotein particle number as a marker of cardiovascular risk in the UK Biobank. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehayek, D.; Cole, J.; Björnson, E.; Wilkins, J.T.; Mortensen, M.B.; Dufresne, L.; Pencina, K.M.; Pencina, M.J.; Thanassoulis, G.; Sniderman, A.D. ApoB, LDL-C, and non-HDL-C as markers of cardiovascular risk. J Clin Lipidol 2025, 19, 844–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björnson, E.; Adiels, M.; Gummesson, A.; Taskinen, M.-R.; Burgess, S.; Packard, C.J.; Borén, J. Quantifying Triglyceride-Rich Lipoprotein Atherogenicity, Associations With Inflammation, and Implications for Risk Assessment Using Non-HDL Cholesterol. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2024, 84, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sniderman, A.D. Are Triglyceride-Rich Lipoprotein ApoB Particles Really 4 Times More Atherogenic Than LDL ApoB Particles? J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 84, 1339–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidah, N.G.; Benjannet, S.; Wickham, L.; Marcinkiewicz, J.; Jasmin, S.B.; Stifani, S.; Basak, A.; Prat, A.; Chretien, M. The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2003, 100, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidah, N.G.; Prat, A. The biology and therapeutic targeting of the proprotein convertases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012, 11, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abifadel, M.; Varret, M.; Rabes, J.P.; Allard, D.; Ouguerram, K.; Devillers, M.; Cruaud, C.; Benjannet, S.; Wickham, L.; Erlich, D.; et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nature Genetics 2003, 34, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.N.; Breslow, J.L. Adenoviral-mediated expression of Pcsk9 in mice results in a low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout phenotype. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 7100–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidah, N.G. The PCSK9 discovery, an inactive protease with varied functions in hypercholesterolemia, viral infections, and cancer. J Lipid Res 2021, 62, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouguerram, K.; Chetiveaux, M.; Zair, Y.; Costet, P.; Abifadel, M.; Varret, M.; Boileau, C.; Magot, T.; Krempf, M. Apolipoprotein B100 metabolism in autosomal-dominant hypercholesterolemia related to mutations in PCSK9. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2004, 24, 1448–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H.; Yang, C.Y.; Chen, P.F.; Setzer, D.; Tanimura, M.; Li, W.H.; Gotto, A.M., Jr.; Chan, L. The complete cDNA and amino acid sequence of human apolipoprotein B-100. J Biol Chem 1986, 261, 12918–12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, S.W.; Grant, S.M.; Higuchi, K.; Hospattankar, A.; Lackner, K.; Lee, N.; Brewer, H.B., Jr. Human liver apolipoprotein B-100 cDNA: complete nucleic acid and derived amino acid sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986, 83, 8142–8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimund, M.; Dearborn, A.D.; Graziano, G.; Lei, H.; Ciancone, A.M.; Kumar, A.; Holewinski, R.; Neufeld, E.B.; O'Reilly, F.J.; Remaley, A.T.; et al. Structure of apolipoprotein B100 bound to the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Nature 2025, 638, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndsen, Z.T.; Cassidy, C.K. The structure of apolipoprotein B100 from human low-density lipoprotein. Nature 2025, 638, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cladaras, C.; Hadzopoulou-Cladaras, M.; Nolte, R.T.; Atkinson, D.; Zannis, V.I. The complete sequence and structural analysis of human apolipoprotein B-100: relationship between apoB-100 and apoB-48 forms. Embo j 1986, 5, 3495–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhou, B.Y.; Li, S.; Sun, N.L.; Hua, Q.; Wu, S.L.; Cao, Y.S.; Guo, Y.L.; Wu, N.Q.; Zhu, C.G.; et al. Genetic basis of index patients with familial hypercholesterolemia in Chinese population: mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlation. Lipids Health Dis 2018, 17, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abifadel, M.; Boileau, C. Genetic and molecular architecture of familial hypercholesterolemia. J Intern Med 2023, 293, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, E.H.; Hopkins, P.N.; Allen, A.; Wu, L.L.; Williams, R.R.; Anderson, J.L.; Ward, R.H.; Lalouel, J.M.; Innerarity, T.L. Association of genetic variations in apolipoprotein B with hypercholesterolemia, coronary artery disease, and receptor binding of low density lipoproteins. J Lipid Res 1997, 38, 1361–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Ison, H.E.; Clarke, S.L.; Knowles, J.W. Familial Hypercholesterolemia. In GeneReviews(®), Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington, Seattle.

- Copyright © 1993-2025, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.: Seattle (WA), 1993.

- Farnier, M.; Bruckert, E.; Boileau, C.; Krempf, M. [Diagnostic and treatment of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) in adult: guidelines from the New French Society of Atherosclerosis (NSFA)]. Presse Med 2013, 42, 930–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetterau, J.R.; Aggerbeck, L.P.; Bouma, M.E.; Eisenberg, C.; Munck, A.; Hermier, M.; Schmitz, J.; Gay, G.; Rader, D.J.; Gregg, R.E. Absence of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in individuals with abetalipoproteinemia. Science 1992, 258, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoulders, C.C.; Brett, D.J.; Bayliss, J.D.; Narcisi, T.M.; Jarmuz, A.; Grantham, T.T.; Leoni, P.R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Pease, R.J.; Cullen, P.M.; et al. Abetalipoproteinemia is caused by defects of the gene encoding the 97 kDa subunit of a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. Hum Mol Genet 1993, 2, 2109–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirwi, A.; Hussain, M.M. Lipid transfer proteins in the assembly of apoB-containing lipoproteins. J Lipid Res 2018, 59, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, L.F.; Ludwig, E.H.; Clarke, H.R.; Vega, G.L.; Grundy, S.M.; McCarthy, B.J. Association between a specific apolipoprotein B mutation and familial defective apolipoprotein B-100. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989, 86, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, R.D.; Krul, E.S.; Tang, J.; Parhofer, K.G.; Garlock, K.; Talmud, P.; Schonfeld, G. ApoB-54.8, a truncated apolipoprotein found primarily in VLDL, is associated with a nonsense mutation in the apoB gene and hypobetalipoproteinemia. J Lipid Res 1991, 32, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krul, E.S.; Parhofer, K.G.; Barrett, P.H.; Wagner, R.D.; Schonfeld, G. ApoB-75, a truncation of apolipoprotein B associated with familial hypobetalipoproteinemia: genetic and kinetic studies. J Lipid Res 1992, 33, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farese, R.V., Jr.; Linton, M.F.; Young, S.G. Apolipoprotein B gene mutations affecting cholesterol levels. J Intern Med 1992, 231, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, A.J.; Heeks, L.; Robertson, K.; Champain, D.; Hua, J.; Song, S.; Parhofer, K.G.; Barrett, P.H.; van Bockxmeer, F.M.; Burnett, J.R. Lipoprotein Metabolism in APOB L343V Familial Hypobetalipoproteinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015, 100, E1484–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surakka, I.; Hornsby, W.E.; Farhat, L.; Rubenfire, M.; Fritsche, L.G.; Hveem, K.; Chen, Y.E.; Brook, R.D.; Willer, C.J.; Weinberg, R.L. A Novel Variant in APOB Gene Causes Extremely Low LDL-C Without Known Adverse Effects. JACC Case Rep 2020, 2, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.G. Recent progress in understanding apolipoprotein B. Circulation 1990, 82, 1574–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, R.S.; Zhao, Y.; Selby, S.L.; Westerlund, J.; Yao, Z. Carboxyl-terminal truncation impairs lipid recruitment by apolipoprotein B100 but does not affect secretion of the truncated apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 2852–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.M.; Blackhart, B.D.; Linton, M.F.; Taylor, S.M.; Young, S.G.; McCarthy, B.J. Expression of carboxyl-terminally truncated forms of human apolipoprotein B in rat hepatoma cells. Evidence that the length of apolipoprotein B has a major effect on the buoyant density of the secreted lipoproteins. J Biol Chem 1991, 266, 3300–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmud, P.J.; Krul, E.S.; Pessah, M.; Gay, G.; Schonfeld, G.; Humphries, S.E.; Infante, R. Donor splice mutation generates a lipid-associated apolipoprotein B-27.6 in a patient with homozygous hypobetalipoproteinemia. J Lipid Res 1994, 35, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.S.; Ripps, M.E.; Korman, S.H.; Deckelbaum, R.J.; Breslow, J.L. Hypobetalipoproteinemia due to an apolipoprotein B gene exon 21 deletion derived by Alu-Alu recombination. J Biol Chem 1989, 264, 11394–11400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essalmani, R.; Jain, J.; Susan-Resiga, D.; Andréo, U.; Evagelidis, A.; Derbali, R.M.; Huynh, D.N.; Dallaire, F.; Laporte, M.; Delpal, A.; et al. Distinctive Roles of Furin and TMPRSS2 in SARS-CoV-2 Infectivity. J Virol 2022, 96, e0012822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essalmani, R.; Susan-Resiga, D.; Chamberland, A.; Abifadel, M.; Creemers, J.W.; Boileau, C.; Seidah, N.G.; Prat, A. In vivo evidence that furin from hepatocytes inactivates PCSK9. J Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 4257–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essalmani, R.; Susan-Resiga, D.; Chamberland, A.; Asselin, M.C.; Canuel, M.; Constam, D.; Creemers, J.W.; Day, R.; Gauthier, D.; Prat, A.; et al. Furin is the primary in vivo convertase of angiopoietin-like 3 and endothelial lipase in hepatocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 26410–26418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaither, C.; Popp, R.; Mohammed, Y.; Borchers, C.H. Determination of the concentration range for 267 proteins from 21 lots of commercial human plasma using highly multiplexed multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Analyst 2020, 145, 3634–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, V.R.; Gaither, C.; Popp, R.; Chaplygina, D.; Brzhozovskiy, A.; Kononikhin, A.; Mohammed, Y.; Zahedi, R.P.; Nikolaev, E.N.; Borchers, C.H. Early Prediction of COVID-19 Patient Survival by Targeted Plasma Multi-Omics and Machine Learning. Mol Cell Proteomics 2022, 21, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidah, N.G.; Prat, A. The Multifaceted Biology of PCSK9. Endocr Rev 2022, 43, 558–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Pratico, D.; Mazidi, M.; Davies, I.G.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Seidah, N.; Libby, P.; Kroemer, G.; Ren, J. PCSK9 in metabolism and diseases. Metabolism 2025, 163, 156064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachan, V.; Le Dévéhat, M.; Roubtsova, A.; Essalmani, R.; Laurendeau, J.F.; Garçon, D.; Susan-Resiga, D.; Duval, S.; Mikaeeli, S.; Hamelin, J.; et al. PCSK7: A novel regulator of apolipoprotein B and a potential target against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 2024, 150, 155736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachan, V.; Susan-Resiga, D.; Lam, K.; Seidah, N.G. The Biology and Clinical Implications of PCSK7. Endocr Rev 2025, 46, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendran, R.P.; Visser, M.E.; Heemelaar, S.; Wang, J.; Peter, J.; Defesche, J.C.; Kuivenhoven, J.A.; Hosseini, M.; Péterfy, M.; Kastelein, J.J.; et al. Mutations in LPL, APOC2, APOA5, GPIHBP1 and LMF1 in patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia. J Intern Med 2012, 272, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Kim, K.; Choi, S.H. Lipoprotein Lipase: Is It a Magic Target for the Treatment of Hypertriglyceridemia. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2022, 37, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeze, H.H.; Kranz, C. Endoglycosidase and glycoamidase release of N-linked glycans. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 2010, Chapter 17, Unit 17.13A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Fisher, E.A.; Ginsberg, H.N. Regulated Co-translational ubiquitination of apolipoprotein B100. A new paradigm for proteasomal degradation of a secretory protein. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 24649–24653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.; Lake, E.; McLeod, R.S. Apolipoprotein B100 quality control and the regulation of hepatic very low density lipoprotein secretion. J Biomed Res 2014, 28, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.E.; Manchekar, M.; Dashti, N.; Jones, M.K.; Beigneux, A.; Young, S.G.; Harvey, S.C.; Segrest, J.P. Assembly of lipoprotein particles containing apolipoprotein-B: structural model for the nascent lipoprotein particle. Biophys J 2005, 88, 2789–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchekar, M.; Richardson, P.E.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Segrest, J.P.; Dashti, N. Charged amino acid residues 997-1000 of human apolipoprotein B100 are critical for the initiation of lipoprotein assembly and the formation of a stable lipidated primordial particle in McA-RH7777 cells. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 29251–29265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, H.N. Role of lipid synthesis, chaperone proteins and proteasomes in the assembly and secretion of apoprotein B-containing lipoproteins from cultured liver cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1997, 24, A29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.O.; Shelness, G.S. APOLIPOPROTEIN B: mRNA editing, lipoprotein assembly, and presecretory degradation. Annu Rev Nutr 2000, 20, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, T.; Takahashi, M.; Okazaki, H.; Okazaki, S.; Yokote, K.; Tada, H.; Ogura, M.; Ishigaki, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Harada-Shiba, M. Current Diagnosis and Management of Familial Hypobetalipoproteinemia 1. J Atheroscler Thromb 2024, 31, 1005–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloso, G.M.; Nomura, A.; Khera, A.V.; Chaffin, M.; Won, H.H.; Ardissino, D.; Danesh, J.; Schunkert, H.; Wilson, J.G.; Samani, N.; et al. Rare Protein-Truncating Variants in APOB, Lower Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, and Protection Against Coronary Heart Disease. Circ Genom Precis Med 2019, 12, e002376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welty, F.K. Hypobetalipoproteinemia and abetalipoproteinemia. Curr Opin Lipidol 2014, 25, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musialik, J.; Boguszewska-Chachulska, A.; Pojda-Wilczek, D.; Gorzkowska, A.; Szymańczak, R.; Kania, M.; Kujawa-Szewieczek, A.; Wojcieszyn, M.; Hartleb, M.; Więcek, A. A Rare Mutation in The APOB Gene Associated with Neurological Manifestations in Familial Hypobetalipoproteinemia. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Condat, B.; Sassolas, A.; Chebel, S.; Bittar, R.; Federspiel, M.C.; Cazals-Hatem, D.; Bruckert, E. Cryptogenic cirrhosis in a patient with familial hypocholesterolemia due to a new truncated form of apolipoprotein B. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009, 21, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A.; Tarugi, P.; Ballarini, G.; Bagni, A. Familial heterozygous hypobetalipoproteinemia, extrahepatic primary malignancy, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 1998, 43, 2489–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Levels of plasma LDLc and apolipoproteins of hypabobetaliproteinema family members: (A) Western blot analysis of plasma apoB and apoE. (B) Mass spectrometry analysis of circulating apoB100, apoC2, apoC3 and apoE.

Figure 1.

Levels of plasma LDLc and apolipoproteins of hypabobetaliproteinema family members: (A) Western blot analysis of plasma apoB and apoE. (B) Mass spectrometry analysis of circulating apoB100, apoC2, apoC3 and apoE.

Figure 2.

Relative abundance of lipids in plasma from different family members. CE: cholesteryl ester, COH: non esterified cholesterol , LPC: lysophosphatidylcholine: PC, phosphatidylcholine: SM: Sphingomyelin, TG: triglycerides.

Figure 2.

Relative abundance of lipids in plasma from different family members. CE: cholesteryl ester, COH: non esterified cholesterol , LPC: lysophosphatidylcholine: PC, phosphatidylcholine: SM: Sphingomyelin, TG: triglycerides.

Figure 3.

FPLC analyses: (A, B) FPLC analysis of total triglycerides (A) and cholesterol (B) levels in the plasma of all fasting subjects. The elution positions of VLDL, LDL and HDL are indicated. Western blot analyses: apoB and apoE in fractions corresponding to (C) VLDL (fractions 3 to 14) and (D) LDL (fractions 15 to 28) of the father and sister.

Figure 3.

FPLC analyses: (A, B) FPLC analysis of total triglycerides (A) and cholesterol (B) levels in the plasma of all fasting subjects. The elution positions of VLDL, LDL and HDL are indicated. Western blot analyses: apoB and apoE in fractions corresponding to (C) VLDL (fractions 3 to 14) and (D) LDL (fractions 15 to 28) of the father and sister.

Figure 4.

Lipid profiling and size of lipoprotein particles: Plasma lipoproteins from the sister (control) and father (subject) were separated by high resolution HPLC. The Triglycerides (A) and cholesterol (B) levels were then measured in each lipoprotein particle. (C) Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy was used to determine the size of the lipoprotein particles.

Figure 4.

Lipid profiling and size of lipoprotein particles: Plasma lipoproteins from the sister (control) and father (subject) were separated by high resolution HPLC. The Triglycerides (A) and cholesterol (B) levels were then measured in each lipoprotein particle. (C) Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy was used to determine the size of the lipoprotein particles.

Figure 5.

APOB gene sequencing: (A) Electropherograms showing a partial sequencing of the exon 3 of APOB gene in the control (sister) and the father (Q380 frame shift). The lower panel shows the corresponding sequence electropherograms from a normal control (top) and the proband (bottom). The putative deleted nucleotide is indicated by a star. (B) The single nucleotide deletion in exon 3 resulted in the substitution of an alanine to proline substitution at position 381 (A381P) just following Gln380, and a frame shift premature stop codon at amino acid position 397, after the new 17 aa extended peptide (381-397).

Figure 5.

APOB gene sequencing: (A) Electropherograms showing a partial sequencing of the exon 3 of APOB gene in the control (sister) and the father (Q380 frame shift). The lower panel shows the corresponding sequence electropherograms from a normal control (top) and the proband (bottom). The putative deleted nucleotide is indicated by a star. (B) The single nucleotide deletion in exon 3 resulted in the substitution of an alanine to proline substitution at position 381 (A381P) just following Gln380, and a frame shift premature stop codon at amino acid position 397, after the new 17 aa extended peptide (381-397).

Figure 6.

apoB expression in IHH naïve cells. (A) schematic representation of HA/V5 doubly tagged human apoB 21 (21%), as well as the apoB9 (9%) resulting from an early stop codon at position 397. (B) IHH cells were transiently transfected with an empty vector (EV) or vectors encoding indicated proteins, the proteins were then analysed in cell extracts and media using the N-terminal tag (HA tag). (C) Glycosidase treatment, Proteins (30 to 50 μg) from IHH cells expressing apoB21 (left panel) or apoB9 (right panel) were digested for 90 min at 37°C with endoglycosidase H (endo H) or endoglycosidase F (endo F) and analysed by western blot (D). IHH transiently expressing apoB21 or apoB9 were treated for 24h with indicated protease inhibitors (MG132: 1 μM, Lactacystin (Lacta): 30 μM, Bafilomycin (Bafilo): 0.1 μM, NH4Cl: 10 mM, Chloroquine (ChQ): 50 μM). NT = non-treated cells. The cells extracts were then analysed by Western blot using HA tag. Quantification of immunoreactive proteins was performed using Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

Figure 6.

apoB expression in IHH naïve cells. (A) schematic representation of HA/V5 doubly tagged human apoB 21 (21%), as well as the apoB9 (9%) resulting from an early stop codon at position 397. (B) IHH cells were transiently transfected with an empty vector (EV) or vectors encoding indicated proteins, the proteins were then analysed in cell extracts and media using the N-terminal tag (HA tag). (C) Glycosidase treatment, Proteins (30 to 50 μg) from IHH cells expressing apoB21 (left panel) or apoB9 (right panel) were digested for 90 min at 37°C with endoglycosidase H (endo H) or endoglycosidase F (endo F) and analysed by western blot (D). IHH transiently expressing apoB21 or apoB9 were treated for 24h with indicated protease inhibitors (MG132: 1 μM, Lactacystin (Lacta): 30 μM, Bafilomycin (Bafilo): 0.1 μM, NH4Cl: 10 mM, Chloroquine (ChQ): 50 μM). NT = non-treated cells. The cells extracts were then analysed by Western blot using HA tag. Quantification of immunoreactive proteins was performed using Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

Figure 7.

CryoEM structure of apoB100 on LDL (PDB 9BDT). The inset shows apoB21 (residues 28-965; based on PDB 9BD1), with the apoB9 region (residues 28-380) highlighted in dark blue. Note that residues 28-38 are missing in the structure.

Figure 7.

CryoEM structure of apoB100 on LDL (PDB 9BDT). The inset shows apoB21 (residues 28-965; based on PDB 9BD1), with the apoB9 region (residues 28-380) highlighted in dark blue. Note that residues 28-38 are missing in the structure.

Table 1.

Age and levels of plasma lipid profile of family members.

Table 1.

Age and levels of plasma lipid profile of family members.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).