Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

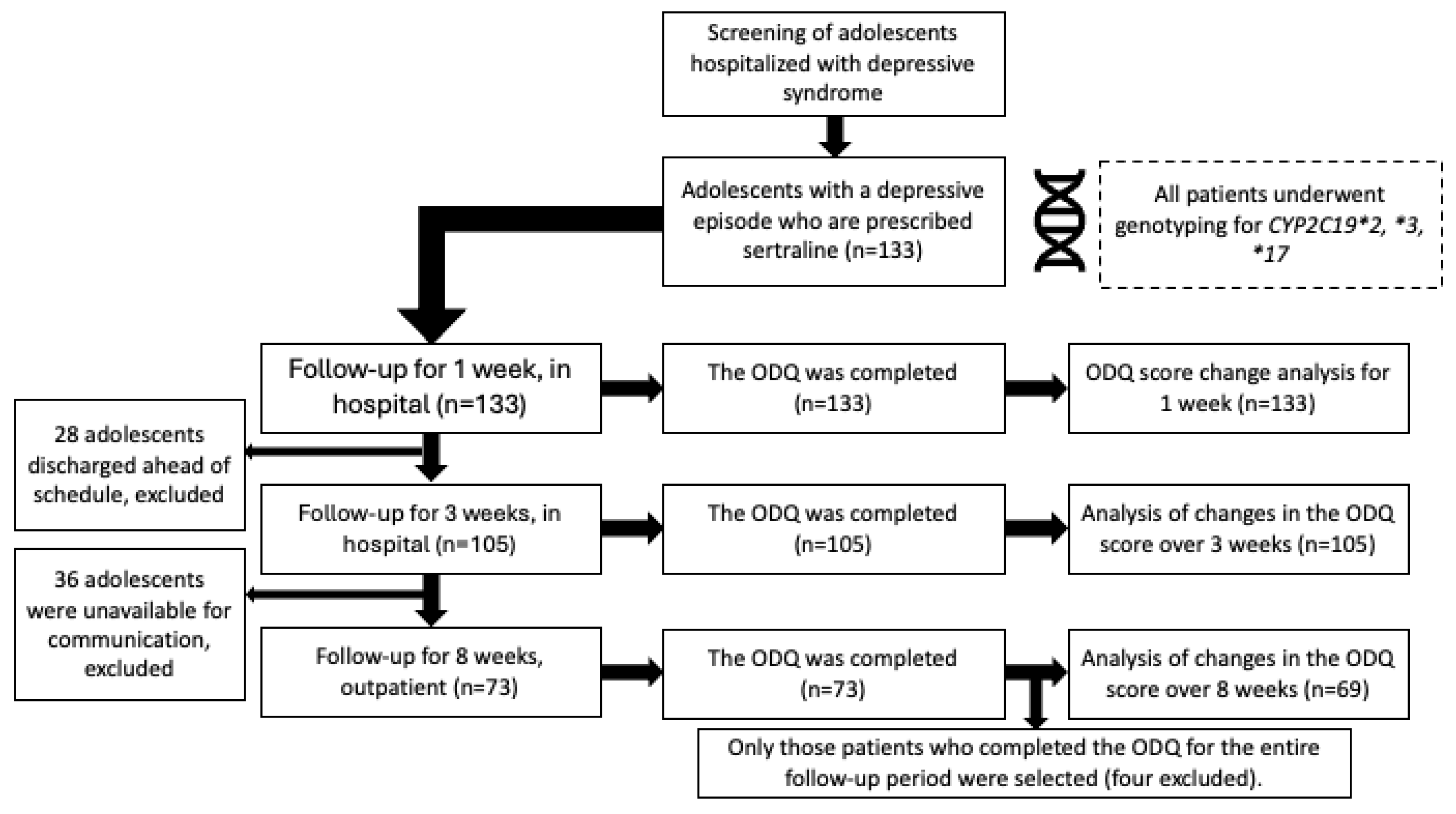

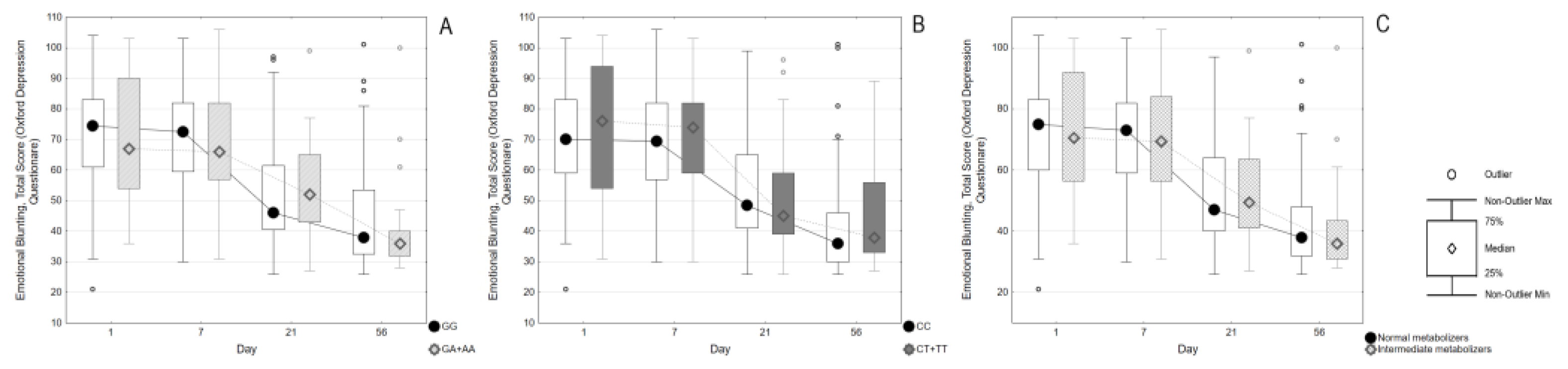

Objectives. To investigate the risk of developing emotional blunting in adolescents with a depressive episode who are prescribed sertraline. To establish associations of carriage of CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms with the antidepressant-induced apathy. Methods. The study included 133 adolescents (89.5% female) aged 12-17 who were prescribed sertraline. The follow-up was carried out for 8 weeks. Emotional blunting was assessed using the Oxford Depression Questionnaire scale (ODQ-26) at the time of activation, after one, three and 8 weeks. We took into account the appointment of additional pharmacotherapy. The polymorphisms CYP2C19*2, *3, *17 were genotyped for all patients. Based on the results of genotyping, the phenotypes of the CYP2C19 isoenzyme were determined. Results. The ODQ score at the time of enrollment was higher (65 [50;79]) compared to after 8 weeks (38 [32;53]). The part 3 of the ODQ-26 questionnaire remained approximately the same for 8 weeks. Patients with higher ODQ-26 values at enrollment (73 [56;83] vs. 59 [44;71], p=0.0006) were more likely to be prescribed antipsychotics. Differences in ODQ scores remained significant up to 3 weeks after enrollment (50.5 [41.5;68], vs. 45.5 [36;54], p=0.015). The comparison of ODQ scores and their dynamics did not show significant differences depending on CYP2C19*2 or *17 polymorphisms, or the type of CYP2C19 metabolism. Conclusion. A negative outcome was observed: there was no improvement in emotional blunting among adolescents with depression who took sertraline for eight weeks. No significant correlations were found between the carriage of CYP2C19 gene variants and the development of apathy induced by antidepressants.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

- Age from 12 to 17 years inclusive.

- Depressive syndrome as the main reason for treatment.

- Suicidal intentions in the patient (thoughts, preparations, or attempts).

- Prescribing of sertraline.

- Signed voluntary informed parental consent for the patient’s participation in the study.

- Criteria for non-inclusion:

- Diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder (F31.X).

- Diagnosis of schizophrenic spectrum disorders (F2X).

- Non-compliance with the inclusion criteria.

- Refusal to participate in the study.

4.1. Sample Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Assessment of Emotional Blunting Using the ODQ Scale

4.3. Pharmacotherapy

4.4. Genotyping

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| ODQ | Oxford Depression Questionnaire |

References

- Raffard, S.; Capdevielle, D.; Attal, J.; Novara, C.; Bortolon, C.; Fritz, N.E.; Boileau, N.R.; Stout, J.C.; Ready, R.; Perlmutter, J.S.; et al. Apathy: A neuropsychiatric syndrome. J. Neuropsychiatry 1991, 3, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnhart, W.J.; Makela, E.H.; Latocha, M.J. SSRI-Induced Apathy Syndrome: A Clinical Review. J. Psychiatr. Pr. 2004, 10, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opbroek, A.; Delgado, P.L.; Laukes, C.; McGahuey, C.; Katsanis, J.; Moreno, F.A.; Manber, R. Emotional blunting associated with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. Do SSRIs inhibit emotional responses? Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002, 5, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, G.; Price, J.; De Bodinat, C.; Laredo, J. Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: A survey among depressed patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 221, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masdrakis, V.G.; Markianos, M.; Baldwin, D.S. Apathy associated with antidepressant drugs: A systematic review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2023, 35, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.C.; Fagiolini, A.; Florea, I.; Loft, H.; Cuomo, A.; Goodwin, G.M. Validation of the Oxford Depression Questionnaire: Sensitivity to change, minimal clinically important difference, and response threshold for the assessment of emotional blunting. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblat, J.D.; Simon, G.E.; Sachs, G.S.; Deetz, I.; Doederlein, A.; DePeralta, D.; Dean, M.M.; McIntyre, R.S. Treatment effectiveness and tolerability outcomes that are most important to individuals with bipolar and unipolar depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 243, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.; Cole, V.; Doll, H.; Goodwin, G.M. The Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants (OQuESA): Development, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 140, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.J.; Baerg, E.A. Amotivational Syndrome Associated with Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Children and Adolescents. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 11, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinblatt, S.P.; Riddle, M.A. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor-Induced Apathy: A Pediatric Case Series. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 16, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousman, C.A.; Stevenson, J.M.; Ramsey, L.B.; Sangkuhl, K.; Hicks, J.K.; Strawn, J.R.; Singh, A.B.; Ruaño, G.; Mueller, D.J.; Tsermpini, E.E.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2B6, SLC6A4, and HTR2A Genotypes and Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 114, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milosavljević, F.; Molden, E.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Jukić, M.M. Current level of evidence for improvement of antidepressant efficacy and tolerability by pharmacogenomic-guided treatment: A Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024, 81, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fares-Otero, N.E.; Budde, M.; Laatsch, J.; Harrer, M.; Pelgrim, T.; Philipsen, A.; Heilbronner, U.; Vieta, E.; van Westrhenen, R. Efficacy of pharmacogenetic (PGx)-guided antidepressant treatment on functional outcomes and quality of life in adults with anxiety and affective disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2025, 100, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zou, Y.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, F.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, J.; Zou, Z. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacogenomic-guided versus unguided antidepressant treatment in major depressive disorder: New insights from subgroup and cumulative meta-analyses. BMJ Ment. Heal. 2025, 28, e301726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossow, K.M.; Aka, I.T.; Maxwell-Horn, A.C.; Roden, D.M.; Van Driest, S.L. Pharmacogenetics to Predict Adverse Events Associated With Antidepressants. Pediatrics 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voort, J.L.V.; Orth, S.S.; Shekunov, J.; Romanowicz, M.; Geske, J.R.; Ward, J.A.; Leibman, N.I.; Frye, M.A.; Croarkin, P.E. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Combinatorial Pharmacogenetics Testing in Adolescent Depression. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 61, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVane, C.L.; Liston, H.L.; Markowitz, J.S. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Sertraline. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2002, 41, 1247–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torso, N.d.G.; Rodrigues-Soares, F.; Altamirano, C.; Ramírez-Roa, R.; Sosa-Macías, M.; Galavíz-Hernández, C.; Terán, E.; Peñas-Lledó, E.; Dorado, P.; Llerena, A. CYP2C19 genotype-phenotype correlation: Current insights and unanswered questions. Drug Metab. Pers. Ther. 2024, 39, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, J.M.J.L.; Nijenhuis, M.; Soree, B.; Guchelaar, H.-J.; Swen, J.J.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; van der Weide, J.; Rongen, G.A.P.J.M.; Buunk, A.-M.; de Boer-Veger, N.J.; et al. Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) guideline for the gene-drug interaction between CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 and SSRIs. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 30, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, S.; Sakayori, T.; Omori, A.; Fukuta, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Ishizaka, K.; Saijo, T.; Okubo, Y. Neuroleptic-induced deficit syndrome in bipolar disorder with psychosis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belujon, P.; A Grace, A. Dopamine System Dysregulation in Major Depressive Disorders. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutt, D.; Demyttenaere, K.; Janka, Z.; Aarre, T.; Bourin, M.; Canonico, P.L.; Carrasco, J.L.; Stahl, S. The other face of depression, reduced positive affect: The role of catecholamines in causation and cure. J. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 21, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sansone, L.A. SSRI-Induced Indifference. Psychiatry 2010, 7, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, E.M.; Balbuena, L.; Lodhi, R.J. Emotional blunting with bupropion and serotonin reuptake inhibitors in three randomized controlled trials for acute major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 318, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy-Weinberg Calc. Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium Online Calculator n.d. Available online: https://www.had2know.org/academics/hardy-weinberg-equilibrium-calculator-2-alleles.html.

| Variables | All Participants (n=133) |

|---|---|

| Age, years (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 15 [14; 16] |

| Height, m (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 1,64 [1,58; 1,68] |

| Weight, kg (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 54,05 [47,6; 62,4] |

| Body mass index (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 19,97 [18,3; 22,4] |

| Female (n, %) | 119, 89,5% |

| Total number of hospitalizations (including the current one) (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 1 [1; 1] |

| Age of onset of symptoms of mental disorder, years (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 13 [12; 14] |

| Suicidal thoughts (n, %) | 124, 93,2% |

| A history of NSSI (n, %) | 122, 91,8% |

| Age of occurrence of NSSI, years (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 13 [12; 14] |

| History of suicide attempt (n, %) | 53(40,2%) |

| Total number of suicide attempts (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 0 [0; 1] |

| Age at the start of taking antidepressants, years (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 14 [13; 16] |

| Duration of mental disorder before inclusion in the study, months (Me [Q1; Q3]) | 18 [8,5; 27] |

| Moment of Inclusion | All Patients (n=133) | CYP2C19*2 | p | CYP2C19*17 | p | CYP2C19 Metabolism | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG (n=105) | GA+AA (n=28) | CC (n=83) | CT+TT (n=50) | "Normal" (n=96) | "Intermediate" (n=27) | |||||

| Overall ODQ score | 65 [50; 79] | 64 [48; 78] | 67,5 [58; 84] | 0,146 | 65 [49;79] | 63,5 [50;80] | 0,678 | 64 [49;78,5] | 69 [59;84] | 0,078 |

| Parts 1-2 score | 64 [49;77] | 63 [44;76] | 67,5 [58;84] | 0,067 | 65 [49;77] | 63 [52;78] | 0,772 | 63 [44,5;76] | 69 [59;84] | 0,028 |

| Part 3 score (n=21) | 9 [6;14] | 9 [6;16] | 11,5 [9;14] | 0,686 | 9 [6;14] | 11 [7;15,5] | 0,645 | 9,5 [6;16] | 11,5 [9;14] | 0,758 |

| Examination after 1 week | All patients (n=133) | CYP2C19*2 | p | CYP2C19*17 | p | CYP2C19 metabolism | p | |||

| GG (n=105) | GA+AA (n=28) | CC (n=83) | CT+TT (n=50) | "Normal" (n=96) | "Intermediate" (n=27) | |||||

| Overall ODQ score | 65 [50; 79] | 62 [50; 78] | 66 [55,5;79,5] | 0,332 | 63 [47;79] | 65,5 [53;79] | 0,726 | 63,5 [50;79] | 66 [54;80] | 0,275 |

| Parts 1-2 score | 54 [41;69] | 53 [40;69] | 56[47;67,5] | 0,372 | 54 [40;68] n=83 | 54 [42;69] n=50 | 0,866 | 53,5 [40;69] | 57 [46;69] | 0,341 |

| Part 3 score | 8 [6;10] | 7 [6;10] | 8,5 [6;11] | 0,280 | 7 [6;10] n=83 | 8 [6;12] n=50 | 0,615 | 8 [6;10] | 9 [6;12] | 0,379 |

| Examination after 3 weeks | All patients (n=105) | CYP2C19*2 | p | CYP2C19*17 | p | CYP2C19 metabolism | p | |||

| GG (n=80) | GA+AA (n=25) | CC (n=64) | CT+TT (n=41) | "Normal" (n=73) | "Intemediate" (n=24) | |||||

| Overall ODQ score | 48 [39;62,5] | 47 [39,63] | 50 [43;58] | 0,42 | 48 [39;63] | 46 [39;59] | 0,734 | 47,5 [39;64] | 49 [43;56] | 0,63 |

| Parts 1-2 score | 41 [32;53] | 40,5[31;55] | 42 [34;48] | 0,522 | 41,5 [33;54] | 39 [32;50] | 0,702 | 41[32;55] | 40,5 [33,5] | 0,755 |

| Part 3 score | 6[6;10] | 6[6;9,5] | 7[6;10] | 0,153 | 6[6;9] | 6[6;11] | 0,386 | 6[6;9] | 7,5[6;9,5] | 0,170 |

| Examination after 8 weeks | All patients (n=73) | CYP2C19*2 | p | CYP2C19*17 | p | Метабoлизм CYP2C19 | p | |||

| GG (n=55) | GA+AA (n=18) | CC (n=45) | CT+TT (n=28) | "Normal" (n=52) | "Intermediate" (n=17) | |||||

| Overall ODQ score | 38 [32; 53] | 38 [32,5; 56] | 35,5 [32; 40] | 0,419 | 36 [31; 47] | 38,5 [33,5; 56,5] | 0,326 | 38 [32; 53] | 36 [32; 40] | 0,515 |

| Parts 1-2 score | 32 [27; 45] | 32 [27; 47] | 29 [26; 34] | 0,420 | 30 [26; 40] | 32,5 [27,5; 46,5] | 0,388 | 32 [26,5; 45,5] | 29 [26; 34] | 0,644 |

| Part 3 score | 6 [6; 8] | 6 [6; 9] | 6 [6; 6] | 0,363 | 6 [6; 6] | 6 [6; 8,5] | 0,502 | 6 [6; 8,5] | 6 [6; 6] | 0,494 |

| ODQ Score Difference | All Patients (n=69) | CYP2C19*2 | p | CYP2C19*17 | p | CYP2C19_Met | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG (n=52) | GA+AA (n=17) | CC (n=42) | CT+TT (n=27) | "Normal" n=49 | "Intermediate" n=16 | |||||

| ODQ-26, 1 week vs. Inclusion | -1[-7;4] | -0,5[-6,5;4,5] | -3 [-8;3] | 0,664 | -2,5 [-8;7] | -1 [-7;2] | 0,850 | 0 [-6;5] | -3,5 [-9,5; 2,5] | 0,428 |

| ODQ-26, 3 weeks vs. 1 week | -19[-27;-8] | -20 [-29,5;-8] | -17 [-20;-8] | 0,139 | -16,5 [-23;-7] | -21[-31;-13] | 0,098 | -19 [-30;-8] | -18,5 [-20;-14] | 0,541 |

| ODQ-26, 8 weeks vs. Inclusion | -29[-42;-16] | -31 [-41,5;-15] | -23 [-45;-16] | 0,962 | -31 [-42;-16] | -23[-46;-16] | 0,985 | -31 [-42;-16] | -28 [-47,5;17,5] | 0,874 |

| ODQ-26, 8 weeks vs. 3 weeks | -8[-17;1] | -7[-17;2] | -14[-17;-3] | 0,185 | -11 [-17;-1] | -4 [-20;3] | 0,209 | -7[-19;1] | -11,5 [16,5;-1,5] | 0,437 |

| ODQ Part 3, 8 weeks vs. 1 weeks | 0[-3;0] | 0[-3,5;0] | -1[-3;0] | 0,929 | 0[-2;0] | 0[-4;0] | 0,595 | 0[-3;0] | -0,5[-3;0] | 0,970 |

| ODQ Part 3, 8 weeks vs. 3 weeks | 0[-2;0] | 0[-1;0] | -1[-3;0] | 0,132 | 0[-1;0] | 0[-2;0] | 0,840 | 0[0;0] | -0,5[-2,5;0] | 0,201 |

| Moment of Inclusion | Antipsychotic | p | Mood Stabilizer | p | Anxiolytic | p | Anticholinergic Drug | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=70) | No (n=63) | Yes (n=17) | No (n=116) | Yes (n=64) | No (n=69) | Yes (n=20) | No (n=113) | |||||

| Overall ODQ score | 73 [56;83] | 59 [44;71] | 0,0006 | 61 [42;69] | 65,5 [50,5;79,5] | 0,389 | 62,5 [48,5;80,5] | 67 [54;78] | 0,433 | 65 [49,5;85,5] | 65 [50;77] | 0,538 |

| Parts 1-2 score | 70[53;79] | 59[38;71] | 0,0023 | 58[42;67] | 65[49,5;78] | 0,206 | 62,5[43,5;80,5] | 65[50;76] | 0,675 | 65[49;84] | 64[50;76] | 0,563 |

| Part 3 score (n=21) | 13[9;18] | 7,5[6;10] | 0,072 | 9[6;13] | 9,5[6,5;15] | 0,780 | 9[6;14] | 10[6;17] | 0,654 | 9[6;13] | 9,5[6;16] | 0,669 |

| Examination after 1 week | Antipsychotic | p | Mood stabilizer | p | Anxiolytic | p | Anticholinergic drug | p | ||||

| Yes (n=70) | No (n=63) | Yes (n=17) | No (n=116) | Yes (n=64) | No (n=69) | Yes (n=20) | No (n=113) | |||||

| Overall ODQ score | 68 [54;81] | 57 [43;73] | 0,0075 | 65 [50;69] | 65,5 [51;79] | 0,864 | 59,5 [51;77] | 66 [50;79] | 0,748 | 67,5 [57,5; 80] | 65 [47;78] | 0,285 |

| Parts 1-2 score | 58[42;73] | 48[7;65] | 0,0114 | 52[42;61] | 54,5[40,5;69] | 0,818 | 55[41;69] | 52[42;68] | 0,895 | 57,5[50,5;70,5] | 52[40;68] | 0,161 |

| Part 3 score | 8[6;11] | 7[6;10] | 0,543 | 8[6;10] | 7[6;10] | 0,464 | 7[6;10] | 8[6;10] | 0,649 | 6,5[6;9] | 8[6;10] | 0,315 |

| Examination after 3 weeks | Antipsychotic | p | Mood stabilizer | p | Anxiolytic | p | Anticholinergic drug | p | ||||

| Yes (n=60) | No (n=45) | Yes (n=13) | No (n=92) | Yes (n=50) | No (n=55) | Yes (n=17) | No (n=88) | |||||

| Overall ODQ score | 50,5 [41,5;68] | 45,5 [36;54] | 0,015 | 51[47;58] | 47[39;63] | 0,211 | 47 [39;66] | 48,5 [39;58] | 0,98 | 48,5 [42;66] | 48 [39;59] | 0,486 |

| Parts 1-2 score | 42[34;60] | 39[29;44] | 0,0181 | 42[39;50] | 40,5[31;54] | 0,399 | 40,5[32;59] | 41[32;50] | 0,876 | 42[36;60] | 41[31;52,5] | 0,409 |

| Part 3 score | 6[6;10,5] | 6[6;8] | 0,150 | 7[6;11] | 6[6;9,5] | 0,383 | 6[6;9] | 6[6;10] | 0,997 | 6[6;10] | 6[6;9,5] | 0,839 |

| Examination after 8 weeks | Antipsychotic | p | Mood stabilizer | p | Anxiolytic | p | Anticholinergic drug | p | ||||

| Yes (n=38) | No (n=35) | Yes (n=9) | No (n=64) | Yes (n=36) | No (n=37) | Yes (n=10) | No (n=63) | |||||

| Overall ODQ score | 39 [33;56] | 36 [32;49] | 0,43 | 41 [29;51] | 38 [33;53] | 0,98 | 38 [33;56] | 38 [32;46] | 0,52 | 34 [33;46] | 38 [32;56,5] | 0,38 |

| Parts 1-2 score | 32,5[27;46] | 30[26;40] | 0,499 | 34[20;45] | 31,5[27;44] | 0,850 | 32,5[27,5;48] | 32[26;40] | 0,413 | 28[27;40] | 32[36;47] | 0,405 |

| Part 3 score | 6[6;8] | 6[6;9] | 0,617 | 6[6;9] | 6[6;7,5] | 0,472 | 6[6;9,5] | 6[6;7] | 0,550 | 6[6;6] | 6[6;9] | 0,079 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).