Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

3. Results

| No | Indeks Value | Category |

|---|---|---|

|

1 2 3 4 |

Not Sustainable Less Sustainable Sustained Highly sustainable |

0-25 26 > index value ≤ 50 51 > index value ≤ 75 76 > index value ≤100 |

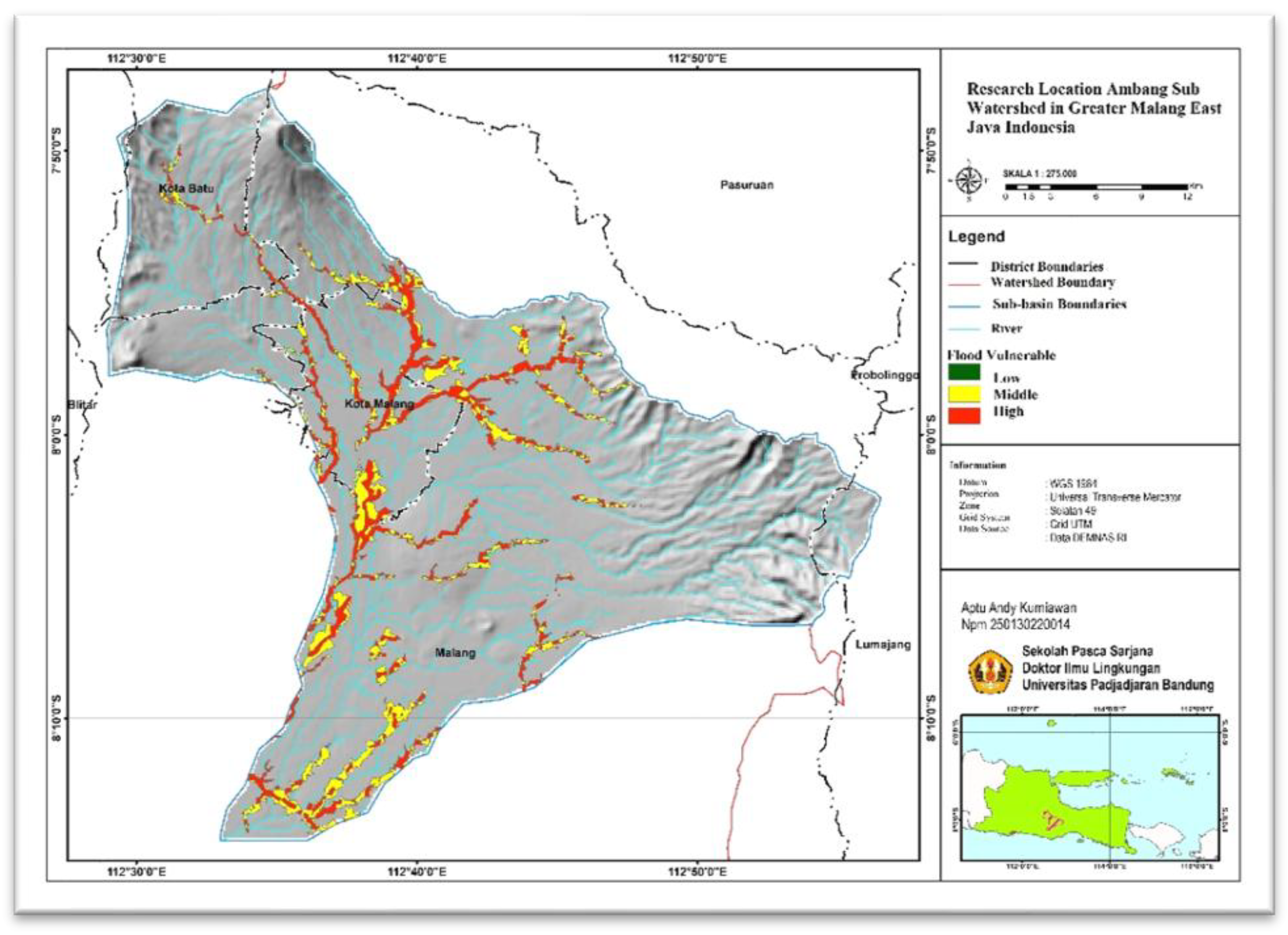

Ecological Dimension

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Funding

Disclosure Statement

References

- K. Lamichhane et al., “Unraveling the Causes and Impacts of Increasing Flood Disasters in the Kathmandu Valley: Lessons from the Unprecedented September 2024 Floods,” Natural Hazards Research, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee, D. Perera, T. Glickman, and L. Taing, “Water-related disasters and their health impacts: A global review,” Dec. 01, 2020, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- M. Pizzorni, A. Innocenti, and N. Tollin, “Droughts and floods in a changing climate and implications for multi-hazard urban planning: A review,” Dec. 01, 2024, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- T. G. Andualem, G. A. Hewa, B. R. Myers, S. Peters, and J. Boland, “Erosion and Sediment Transport Modeling: A Systematic Review,” Jul. 01, 2023, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- D. Bertoni, A. Pozzebon, P. Ruol, and C. Favaretto, “Tumbling Experiment for The Estimation of Abrasion and Mass Loss of Coastal Sediments from an Artificial Coarse-Clastic Beach,” Coastal Engineering Proceedings, 2023, pp. 59–61. [CrossRef]

- A. Firoozi and A. A. Firoozi, “Water erosion processes: Mechanisms, impact, and management strategies,” Results in Engineering, vol. 24, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Åhlén, J. Thorslund, P. Hambäck, G. Destouni, and J. Jarsjö, “Wetland position in the landscape: Impact on water storage and flood buffering,” Ecohydrology, vol. 15, no. 7, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang et al., “Flood risk assessment of subway systems in metropolitan areas under land subsidence scenario: A case study of Beijing,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1–33, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Huang, “Risk Assessment of Flood Disaster in Linyi City Based on GIS,” in E3S Web of Conferences, EDP Sciences, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Yildirim and I. Demir, “An Integrated Flood Risk Assessment and Mitigation Framework: A Case Study for Middle Cedar River Basin, Iowa, US,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 56, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. R. Ziga-Abortta and S. Kruse, “What drives vulnerability? Explaining the institutional context of flood disaster risk management in Sub-Saharan Africa,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 97, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Asdak, Hidrologi dan Pengelolaan Daerah Aliran Sungai, Revisi. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press, 2022.

- R. Suyarto et al., “Hydrological Approach for Flood Overflow Estimation in Buleleng Watershed, Bali,” International Journal of Safety and Security Engineering, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 883–891, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Bonilla Brenes, J. Hack, M. Morales, and R. Oreamuno, “Integral recovery of an urban watershed through the implementation of nature-based solutions,” Frontiers in Sustainability, vol. 5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Dahlmann, R. Stephan, and K. Stahl, “Upstream-downstream asymmetries of drought impacts in major river basins of the European Alps,” Frontiers in Water, vol. 4, pp. 1–15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Sulistyaningsih et al., “Public policy analysis on watershed governance in Indonesia,” Jun. 02, 2021, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- B. H. Narendra et al., “A review on sustainability of watershed management in Indonesia,” Oct. 01, 2021, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- C. Y. Lastiantoro, D. S. A. Cahyono, B. Penelitian, T. Kehutanan, P. Das, and J. A. Yani, “Analysis of stakeholders role in Bengawan Solo Upstreams Watershed Management,” Jurnal Analisis Kebijakan Kehutanan, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 203–212. [CrossRef]

- N. T. Waskitho, A. A. Pratama, and T. Muttaqin, “Sectoral Integration in Watershed Management in Indonesia: Challenges and Recomendation,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing Ltd., May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sriyana, “Indeks Stakeholders Pengelolaan Daerah Aliran Sungai dengan Pendekatan KISS di Indonesia,” Media Komunikasi Teknik Sipil, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 79–86, 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Przesdzink, L. M. Herzog, and F. Fiebelkorn, “Combining Stakeholder- and Social Network- Analysis to Improve Regional Nature Conservation: A Case Study from Osnabrück, Germany,” Environ Manage, vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 271–287, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Watson, D. Shrubsole, and B. Mitchell, “Governance arrangements for integrated water resources management in Ontario, Canada, and Oregon, USA: Evolution and lessons,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 4, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Pambudi, “Watershed Management in Indonesia: A Regulation, Institution, and Policy Review,” The Indonesian Journal of Development Planning, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 185–202, 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Supangat, C. Agus, N. Wahyuningrum, D. R. Indrawati, and Purwanto, “Soil and Water Conservation Planning Toward Sustainable Management of Upstream Watershed in Indonesia,” Springer Nature Switzerland, 2021, pp. 77–91. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Minang, F. Bernard, and J. Nzyoka, Transparent and Accountable Management of Natural Resources in Developing Countries: The Case of Forests SEE PROFILE Lalisa A Duguma Global Evergreening Alliance. Belgium: Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies, 2017. [CrossRef]

- OECD, Toolkit for water policies and governance: converging towards the OECD Council recommendation on water. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Y. S. H. Nugroho et al., “Forty Years of Soil and Water Conservation Policy, Implementation, Research and Development in Indonesia: A Review,” Mar. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- E. Aldrian, B. Pengkajian, P. Teknologi, and J. M. H. Thamrin, “Sistem Peringatan Dini Menghadapi Iklim Ekstrem Early Warning System for Climate Extreme,” Jurnal Sumberdaya Lahan, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 79–90, Dec. 2016.

- X. Tang and J. A. Adesina, “Integrated Watershed Management Framework and Groundwater Resources in Africa—A Review of West Africa Sub-Region,” Feb. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- T. Hermassi, F. Jarray, W. Tlili, I. Achour, and M. Mechergui, “Integrative hydrologic modelling of soil and water conservation strategies: a SWAT-based evaluation of environmental resilience in the Merguellil watershed, Tunisia,” Frontiers in Water, vol. 7, 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhang and W. Lu, “Coordination of interests between upstream and downstream governments in water source areas,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 15, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Smolenaars et al., “Future upstream water consumption and its impact on downstream water availability in the transboundary Indus basin,” vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 861–883, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Thu Ha, S. H. Kim, and D. H. Bae, “Impacts of upstream structures on downstream discharge in the transboundary imjin river basin, Korean Peninsula,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 10, no. 9, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Dirwai, E. K. Kanda, A. Senzanje, and T. I. Busari, “Water resource management: Iwrm strategies for improved water management. A systematic review of case studies of east, west and southern Africa,” PLoS One, vol. 16, no. 5 May, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Ben-Daoud et al., “Integrated water resources management: An indicator framework for water management system assessment in the R’Dom Sub-basin, Morocco,” Environmental Challenges, vol. 3, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Sufri and J. A. Lassa, “Integration of disaster risk reductionand climate change adaptation in Aceh: Progress and challenges after 20 Years of Indian Ocean Tsunamis,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 113, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Dowlati, H. Seyedin, A. Behnami, A. Marzban, and M. Gholami, “Water resources resilience model in climate changes with community health approach: Qualitative study,” Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, vol. 8, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Subagyono and H. Pawitan, “Water harvesting techniques for sustainable water resources management in catchments area,” 2007. [Online]. Available: http://www.worldwater.org/data20062007.

- Fitriyani, R. Khoirudin Apriyadi, T. Winugroho, D. Hartono, I. Dewa Ketut Kerta Widana, and W. Wilopo, “Karakteristik Histori Bencana Indonesia Periode 1815 – 2019 Berdasarkan Jumlah Bencana, Kematian, Keterpaparan dan Kerusakan Rumah Akibat Bencana,” PENDIPA Journal of Science Education, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 322–327, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Noywuli, A. Sapei, N. H. Pandjaitan, and E. Eriyatno, “Model Kelembagaan Pengelolaan DAS Aesesa Flores, Provinsi NTT,” Jurnal Ilmu Lingkungan, vol. 16, no. 2, p. 136, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. B. Barbier and J. C. Burgess, “The sustainable development goals and the systems approach to sustainability,” Economics, vol. 11, no. 20170028, pp. 1–23, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Harré, C. Blythe, L. McLean, and S. Khan, “A People-Focused Systems Approach to Sustainability,” Am J Community Psychol, vol. 69, no. 1–2, pp. 114–133, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Ahrens, S. Krumdieck, and D. Kenning, “Interdisciplinary Transition Innovation, Management, and Engineering (InTIME) Design: an intersection analysis of design approaches for whole-system sustainability,” in Proceedings of the Design Society, Cambridge University Press, 2024, pp. 1169–1178. [CrossRef]

- N. R. A. B. M. Khalila, S. A. L. S. Sagar, and M. F. Basar, “An Overarching Summary of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),” International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1234–1240, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kimbugwe, S. Sou, H. Crichton-Smith, and F. Goff, “Practical system approaches to realise the human rights to water and sanitation: Results and lessons from Uganda and Cambodia,” H2Open Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 68–82, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Nenni, V. Di Pasquale, and J. Boyer, “The Complicated Relationship between Innovation and Sustainability: Opportunities, Threats, Challenges, and Trends,” May 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Suprayogo, Widianto, K. Hairiah, and I. Nita, “Manajemen Daerah Aliran Sungai (DAS): Tinjauan Hidrologi Akibat Perubahan Tutupan Lahan dalam Pembangunan,” Malang: UB Press, 2017.

- P. Kavanagh and T. J. Pitcher, “Implementing Microsoft Excel Software For Rapfish: A Technique For The Rapid Appraisal of Fisheries Status,” Fisheries Centre Research Reports, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 1–75, 2004.

- S. H. Sadeghi, M. Zabihi Silabi, H. Sarvi Sadrabad, M. Riahi, and S. Modarresi Tabatabaei, “Watershed health and ecological security modeling using anthropogenic, hydrologic, and climatic factors,” Nat Resour Model, vol. 36, no. 3, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Al Masud, H. Azadi, A. K. Azad, I. Goli, M. Pietrzykowski, and T. Dogot, “Application of Sustainability Index of Tidal River Management (SITRM) in the Lower Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna Delta,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 17, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Gedefaw, M. A. Desta, and R. Mansberger, “Impacts of Integrated Watershed Management Interventions on Land Use/Land Cover of Yesir Watershed in Northwestern Ethiopia,” Land (Basel), vol. 13, no. 7, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

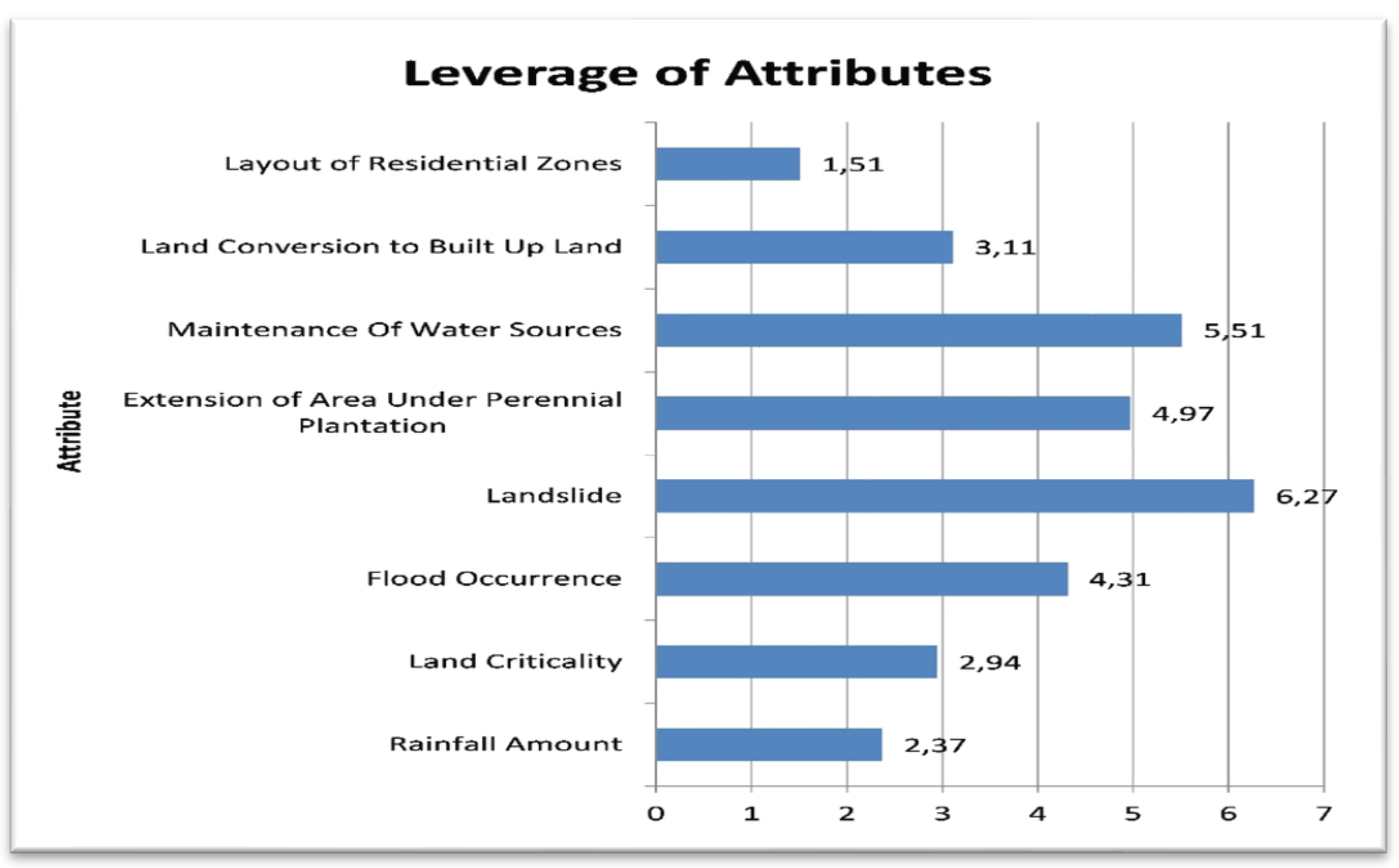

| No | Leverage Factors | RMS | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

Landslide Maintenance Of Water Resources Extension of Area under Perennial Plantation Flood Occurence Land Conversion to Build Up Land |

6,27 5,51 4,97 4,31 3,11 |

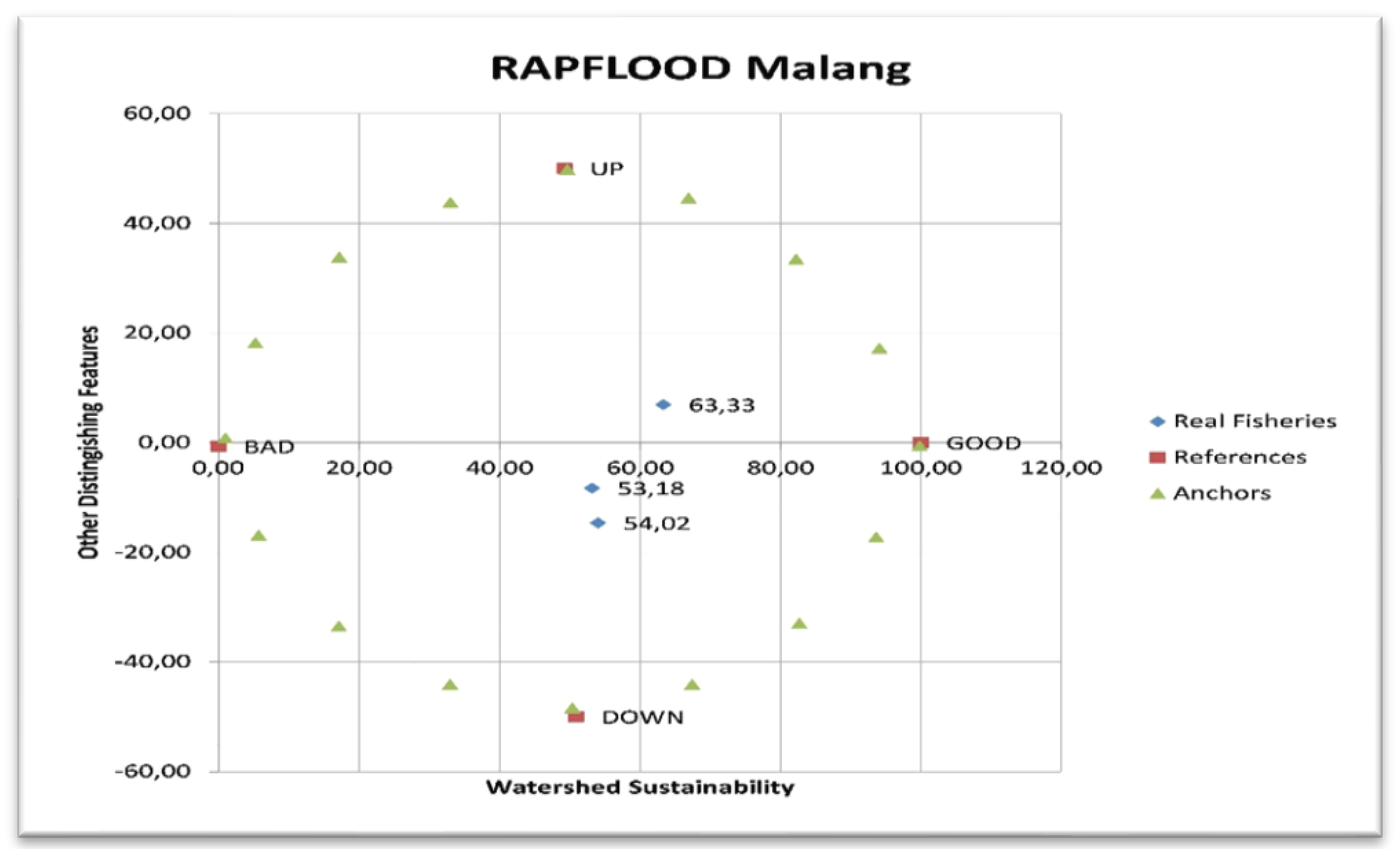

| Dimension | Sub Watershed | Value of Sustainability Index | MDS-MC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDS | Monte Carlo | |||

| Ecology | Upstream Middlestream Downstream |

53,18 63,33 54,02 |

53,24 62,48 53,37 |

0,06 0,85 0,65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).