1. Introduction

Minimal invasive spine surgery is present nowadays. Some tools in minimal invasive spine tumor resection are tubular retractors, mini-open retractors and some others. These systems are some of the many minimal invasive techniques in the context of degenerative spine diseases 3,4, spine infection and tumor resection, but in the context of endoscopic spine surgery, specifically UBE, there are a few articles that describe how to perform different procedures with this technique1.

In this article we will describe UBE surgical technique in the context of spine tumors, specifically extramedullary tumors like meningioma or schwannoma and some others. We will describe these procedures with our clinical cases step by step to explain why UBE is the best option for this kind of tumor in terms of safety, surgical time, hospitalization time, intraoperative blood loss, complication and functional outcome.

2. Patient and Methods

A retrospective review of 11 cases of spinal thoracolumbar extramedullary tumors operated by our senior surgeon with experience in UBE technique. All of these cases were performed with a laparoscopic screen, classic hook probes and micro-forceps, small curettes, narrow osteotomes, and even modified bipolar electrocautery probes, as well as standard arthroscopy equipment, the arthroscopic shaver which also doubles as a bone drill and burr, radiofrequency (RF) coagulator wands for both hemostasis and soft-tissue debridement, and of course the standard arthroscope, we use a 30° “glancing” endoscope with a diameter of 4 mm and a length of 175 mm that inserts into a 6-mm-wide saline infusion endoscope sleeve is usually sufficient for basic UBE work5,6,7.

All these surgeries were performed in the San Jose Celaya Hospital, between January 2023 and May 2025. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee. All patients with a diagnosis of a spinal extramedullary tumor (intra or extradural extension) with a 3 level extension or less were included, a thoracolumbar region was selected for this study, and the size of the lesion wasn’t relevant for this study. Data were collected from hospital medical records and video recording during surgery.

Clinical evaluation and spine magnetic resonance imaging were the principal points in the presurgical analysis. Surgical technique, operative time, intraoperative blood loss, histopathology of tumors, duration of hospitalization, and complications were analyzed in detail. Extent of resection was analyzed perioperatively and with postoperative MRI. Patient outcomes were assessed in the immediate post-op and 6 months postoperatively with ODI scale, back VAS and leg VAS.

2.1. Surgical Technique

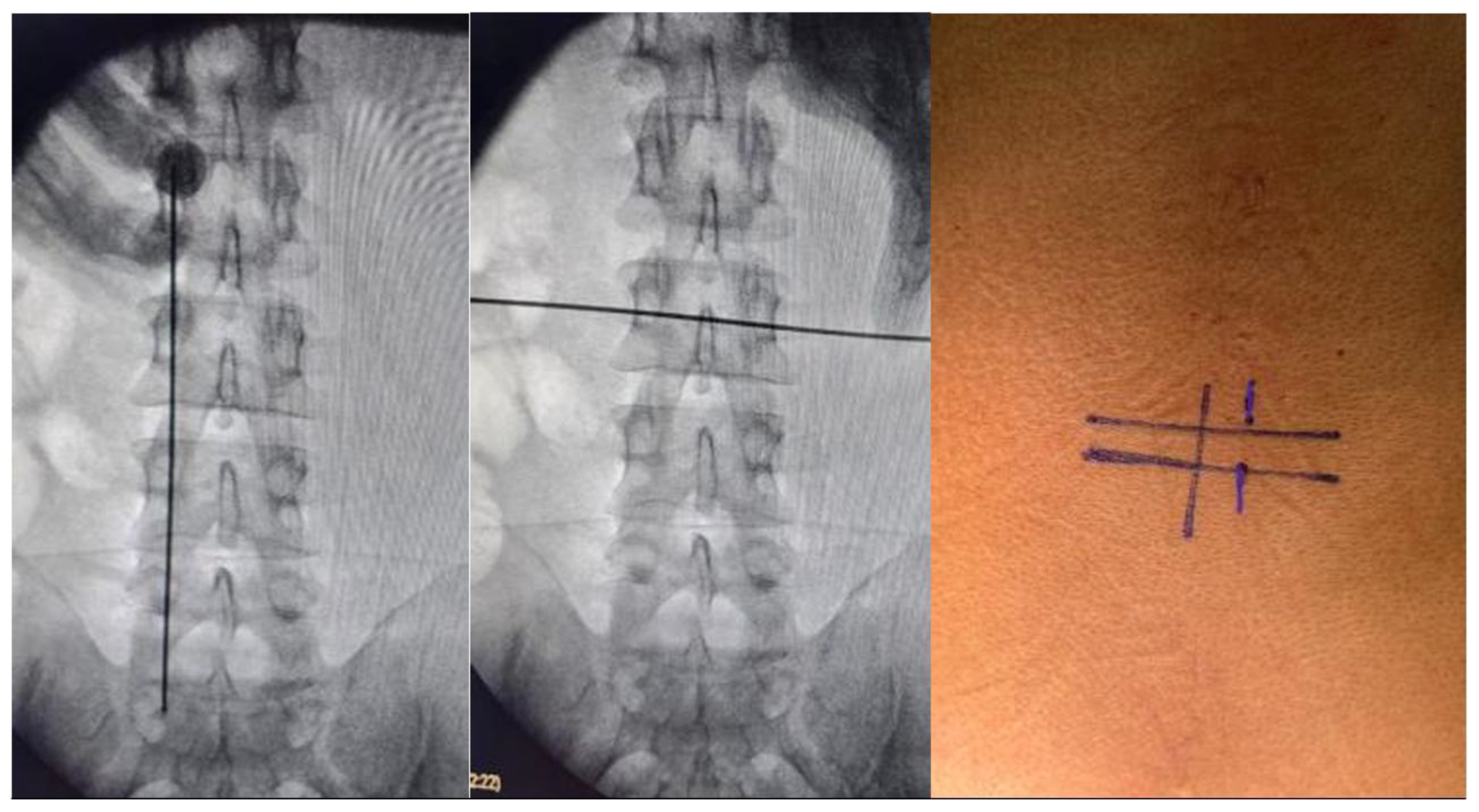

Surgical planning was to perform this procedure with two small incisions with the UBE technique, using a right-sided approach in 8 tumors and 3 with a left-sided approach with fluoroscopy main spinometric marks on the mid-pedicular lines for the right-sided approach and infra-pedicular lines in horizontal plain for the left sided approach and medial pedicular line in vertical plain, we recommend take ap and lateral image to confirm the location, this to achieve a better movement on the tissues and flexibility at the time of durotomy and tumor dissection, we recommend perform a midline durotomy, but this can be modifiable depending on the location of the lesion. The patient was positioned on a classic prone on a radiolucent operating table. We arm the operating room in a classical way for biportal endocopy surgery. (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Step 1—The incision was marked as previously described. In all cases, we do the incision with a 20 scalpel blade in a 900 orientation of the fluoroscopic spinometric landmark. We perform this same incision in the fascia and bend the scalpel in a cephalo-caudal way to open the muscular tissue and make easier the creation of the working pocket for the continuous water flow without increasing pressure in the surgical chamber1.

Step 2—we introduce directly the 300 biportal endoscope (this can also be performed with 300 arthroscopes) and our working instrument, without introducing dilatators. This saves time and works better for creating the working pocket without significant tissue disruption.

Step 3—With gravity-based water irrigation (about 70–100 cm above the table) or a pumping system (20–30 mmHg) was used for continued saline irrigation at normal temperature without heating saline bags. We perform a minimum tissue disruption with a disc forceps. After that, we enlarge the working pocket as necessary with plasma radiofrequency as necessary, and we perform a flavectomy with an over-the-top technique and amplification of the laminotomy to bilateral, cephalic and caudal lamina under the spinous process for preserving anatomic structures. We achieve a wider O-cut4 as necessary and proceed when we can visualize all neural structures without ligamentum flavum on it.

Step 4—With the exposure of the spinal thecal sac, we perform, in most cases, a vertical midline incision of 2cm to 2.5cm. Based on the size of the lesion. We recommend a maximum 3cm incision and manipulation of the dura for larger lesions (this point is vital for the closure technique chosen to perform).

Step 5—after the dura opening. The water flow has to be controlled from 15 to 20mmHg in the case of water pumps or in the case of gravity-based saline irrigation. We lower the saline bags to 50–60 cm above the operating table to achieve a constant minimal water flow to perform the dissection of the lesion without pushing out the nerves from the dural sac margin, with conventional microsurgical techniques like as fragmentation or one-piece global total resection. This can be achieved with UBE because we use the same instruments as Rhoton or Penfield’s dissectors, curets and pituitary forceps. Another point in favor of UBE is the intermittent water dissection. This can be achieved by changing the water pump flow from 15mmHg to 30mmHg in different areas of the lesion when hard adhesions are found, we recommend using this technique for 1 minute as maximum to avoid complication associated with high water pressure like rise on intracranial pressure, remember in case of need vessels cauterization only use UBE intraspinal canal plasma electrodes. The resection of the lesion is a combination of dissection and traction with rootons, nucleus pulposus forceps and pituitary forceps. This is to ensure a safe resection. Once the resection is complete, the hemostasis must be carefully reviewed. With a 300 UBE endoscope, it is possible to obtain a scanning effect that improves all the visual fields 8,9,10.

Step 6—After the resection is performed, dural closure is a challenge. We do a continuous simple suture with extracorporeal double knots at the edges of the durotomy. Hemo-clips are another safe way to do dural closure in the case of a short durotomy (less than 1cm) with or without a dura mater synthetic patch as needed. We only use the synthetic patch in the case of asymmetrical dural opening2.

In general, we use the same position and same spinometric patterns and surgical techniques for all kinds of thoracolumbar tumor, but we will describe ich type of tumor and will give you surgical tips for your practice through this article.

2.2. Illustrative Case

Schwannoma

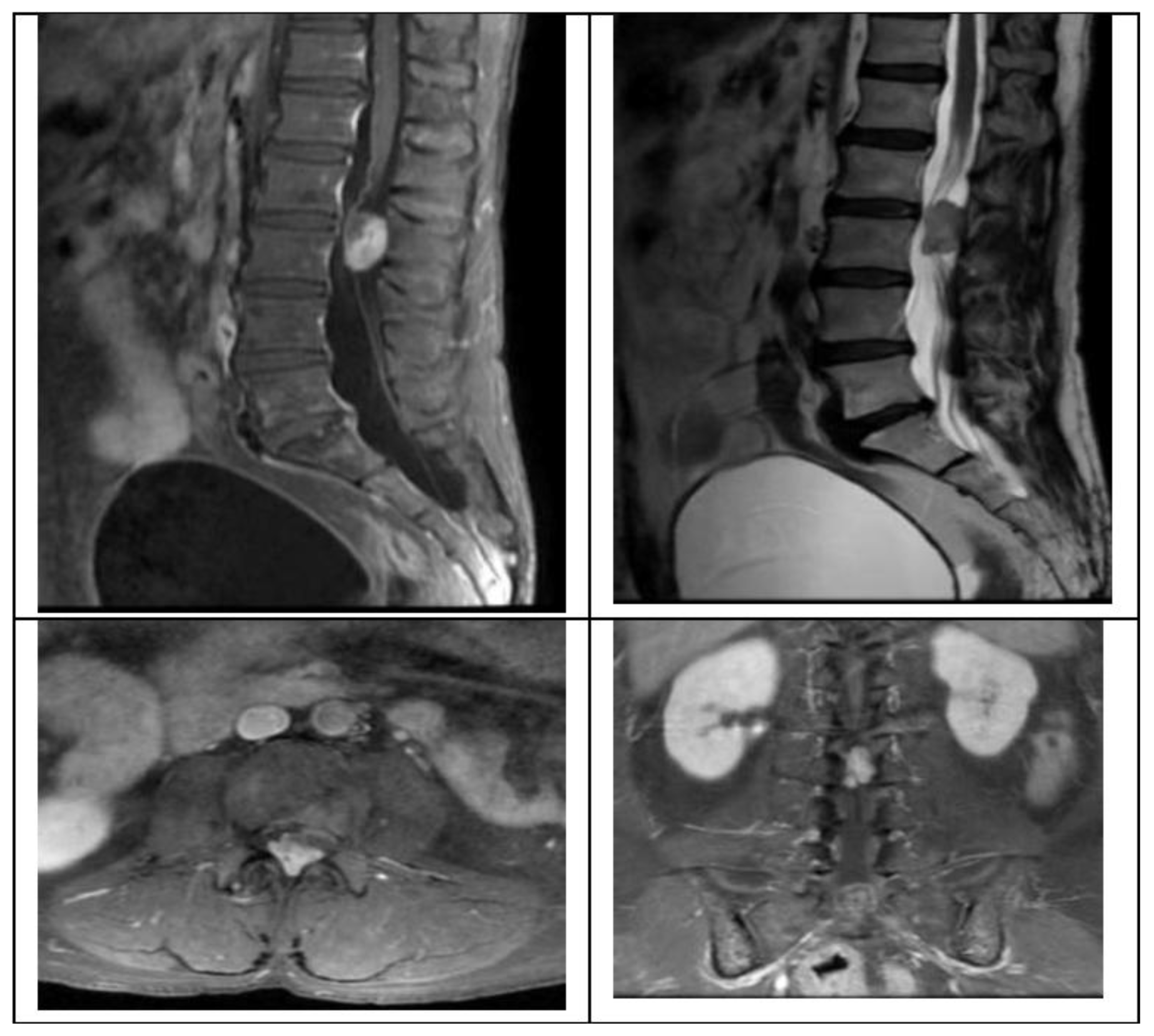

We present the case of a 58-year-old female with 2 months of progressive left leg radiculopathy with a leg VAS 9/10, low back pain, back VAS 7/10, and weakness in both lower limbs, with gait impossibility, and neurogenic bladder, MRI revealed a L2-L3 intradural extramedullary lesion that occupies 80% of the spinal canal (

Figure 1), as previously described we plan are surgery with UBE technique, with a right side approach, with the spinometric landmarks (

Figure 2), with minimal muscular tissue disruption, with bilateral laminotomy of the cephalic and caudal lamina with wider O-cut with over the top technique and flavectomy with Kerrison’s rongeur and curettes, we do a mid-line durotomy with a single cut with 11 blade scalpel and wide de incision with Rhoton dissector, visualize the tumor and perform the dissection with Rhotons and Penfield’s, water dissection increasing the pump flow and then extract the lesion with pituitary forceps without complications over the procedure. We perform closure with a 6-0 prolene suture with the previously described technique. (

Figure 3)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, surgical parameters, and clinical outcomes were stratified by histopathological diagnosis. For continuous variables including age, operative time, estimated blood loss, and hospital length of stay, means and standard deviations were calculated when appropriate. Categorical variables such as gender distribution, tumor location, extent of resection, and symptom presentation were analyzed using frequency distributions.

2.4. Inferential Statistics

Given the sample sizes within each tumor subgroup, exact non-parametric statistical methods were employed for comparative analyses. The primary measure was the change in leg Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores from preoperative to 6-month postoperative follow-up. For within-group comparisons of preoperative versus postoperative leg VAS scores, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with exact p-values was performed with a one-tailed 'greater' alternative hypothesis. For samples with n = 2, exact probabilities were calculated manually. The sign test was employed as a complementary non-parametric approach to assess the proportion of patients showing improvement. A clinically meaningful improvement was defined as a reduction of ≥2 points on the 10-point VAS scale, consistent with established minimal clinically important difference (MCID) thresholds for spine pain assessment. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using Python (version 3.9) with SciPy (version 1.7.3) library.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Tumor Characteristics

Between January 2023 and May 2025, eleven patients underwent UBE resection of thoracolumbar extramedullary spinal tumors at our institution. The cohort comprised 7 women (63.6%) and 4 men (36.4%) with a mean age of 59.3 ± 18.2 years (range: 12–76 years). One pediatric patient (12 years old) was included in the series.

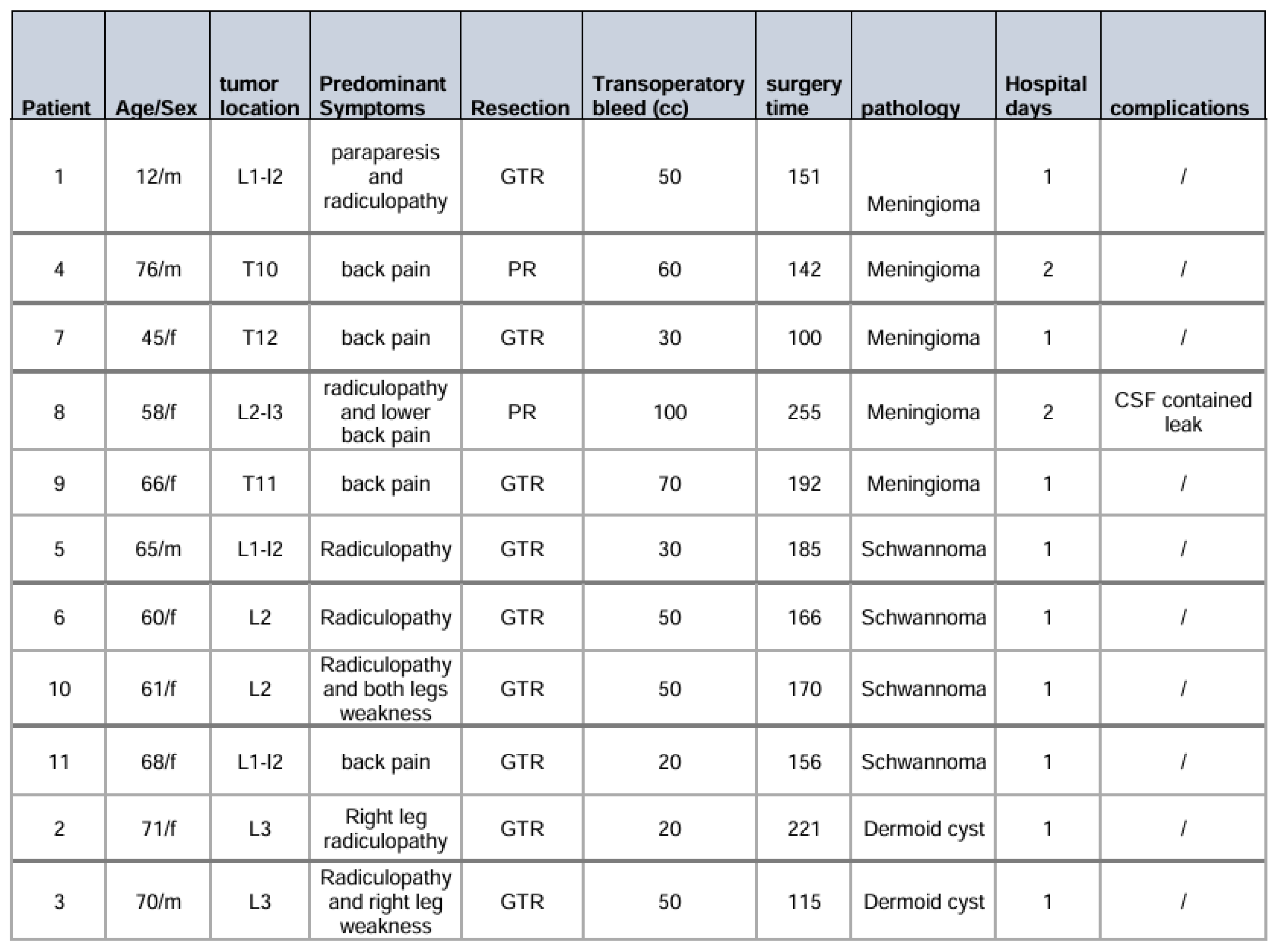

Tumor distribution by histopathology revealed 5 meningiomas (45.5%), 4 schwannomas (36.4%), and 2 dermoid cysts (18.2%). All lesions were located within the thoracolumbar spine between T10 and L4 levels. Clinical presentation was dominated by radicular leg pain in 7 patients (63.6%), while 5 patients (45.5%) presented with axial back pain. All patients demonstrated neurological deficits, including motor weakness, sensory alterations, or both. The mean duration of symptoms prior to surgical intervention was 4 months (

Table 1).

3.2. Surgical Outcomes and Complications

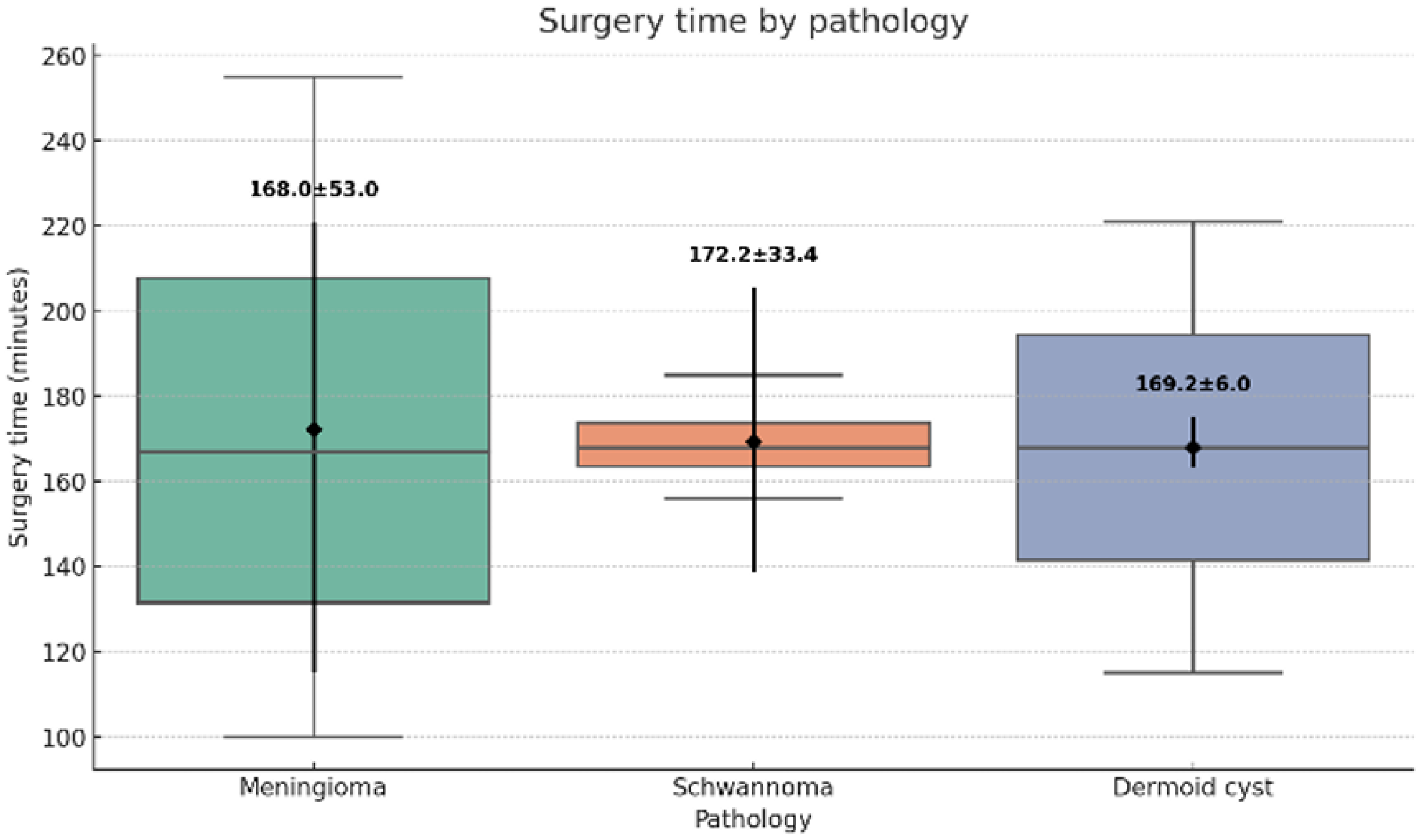

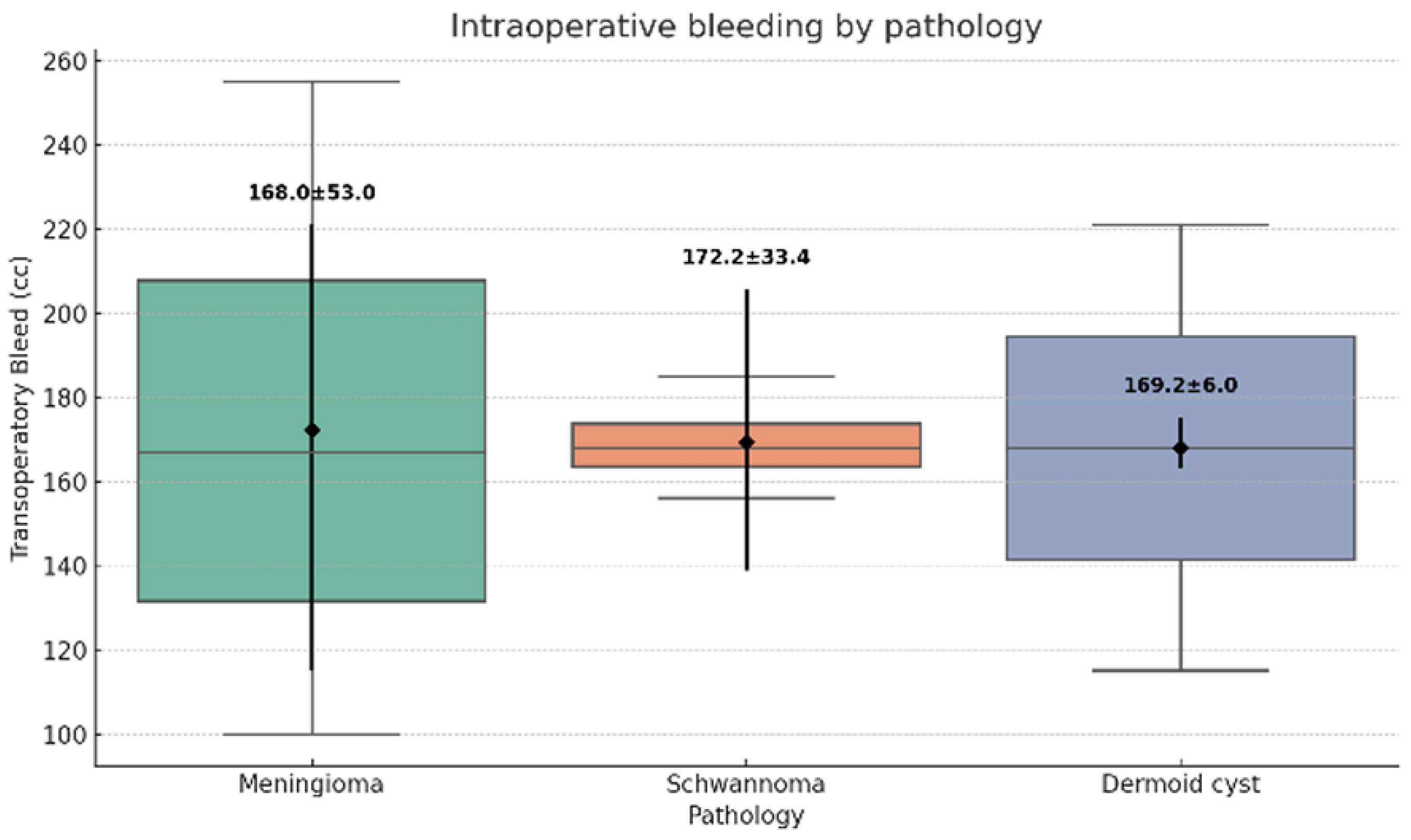

All procedures were completed successfully using the UBE technique without conversion to open surgery. The mean operative time was 168.5 ± 24.3 minutes (range: 100–200 minutes) (

Figure 4). Estimated blood loss averaged 48.1 ± 12.7 mL (range: 30–70 mL) (

Figure 5). The GTR was achieved in 9 cases (81.8%), while 2 patients with meningiomas underwent subtotal resection due to dense dural adhesions. In these cases, radiofrequency ablation was applied to residual tumor adherent to the dural surface.

No intraoperative complications occurred during the series. All patients were mobilized within 12 hours postoperatively. The mean hospital stay was 1.5 ± 0.7 days (range: 1–3 days). One patient (9.1%) developed a contained cerebrospinal fluid leak, which was resolved spontaneously within 3 months without requiring surgical intervention.

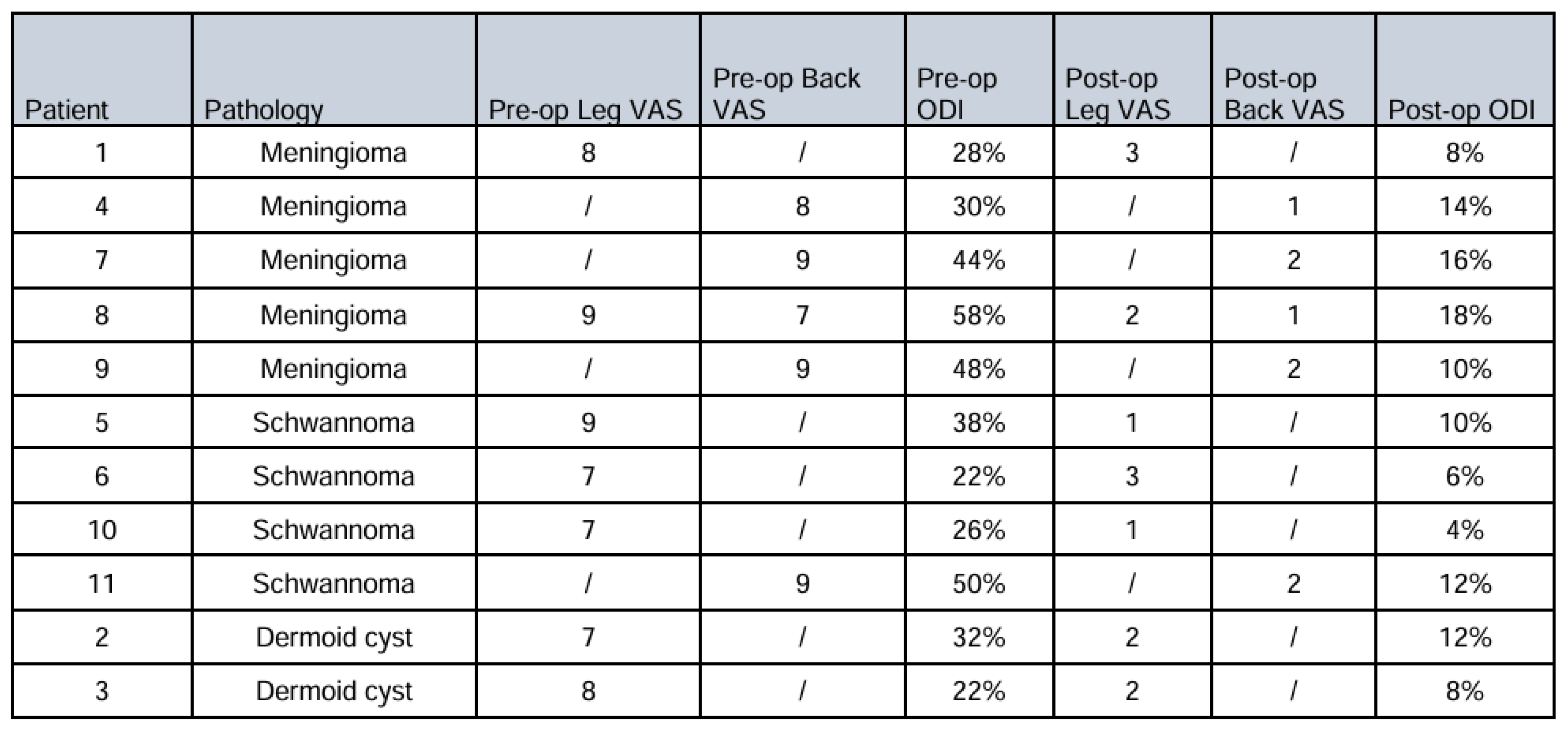

3.3. Pain and Functional Outcomes

Complete preoperative and postoperative leg VAS data were available for 7 patients (63.6% of the total cohort). The remaining 4 patients either presented primarily with back pain or had incomplete VAS documentation. Among patients with complete leg VAS data, the distribution by tumor type was: 2 meningiomas (28.6%), 3 schwannomas (42.9%), and 2 dermoid cysts (28.6%).

Patients with meningiomas demonstrated substantial improvement in leg pain scores. Preoperative leg VAS averaged 8.5 ± 0.7 points, decreasing to 2.5 ± 0.7 points at 6-month follow-up (mean improvement: 6.0 ± 1.4 points). Individual patient responses showed improvements from 8 to 3 points and 9 to 2 points, respectively. Although statistical significance was not achieved due to the small sample size, the clinical effect was substantial, with both patients exceeding the MCID threshold by a considerable margin.

The schwannoma cohort exhibited the most robust pain relief outcomes. Mean preoperative leg VAS was 7.7 ± 1.2 points, improving to 1.7 ± 1.2 points postoperatively (mean improvement: 6.0 ± 2.0 points). Individual patient improvements were 8, 4, and 6 points on the VAS scale, respectively. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test demonstrated a statistic of 3 with an exact p-value of 0.125. The sign test revealed that 3/3 patients (100%) experienced clinically significant improvement (p = 0.125). While approaching statistical significance, the clinical impact was pronounced across all patients.

Patients with dermoid cysts also demonstrated consistent pain improvement. Preoperative leg VAS scores averaged 7.5 ± 0.7 points, decreasing to 2.0 ± 0.0 points at follow-up (mean improvement: 5.5 ± 0.7 points). Individual improvements were 5 and 6 points, respectively.

3.4. Overall Pain Outcomes

Across all tumor types, 7/7 patients with complete leg VAS data demonstrated improvement in radicular leg pain. The overall mean improvement was 5.8 ± 1.6 points on the 10-point VAS scale. No patient experienced worsening leg pain scores at 6-month follow-up.

Back pain VAS scores were documented for 4 patients who were presented with predominant axial symptoms. Mean preoperative back VAS was 8.3 ± 1.0 points, improving to 1.5 ± 0.6 points postoperatively (mean improvement: 6.8 ± 1.5 points).

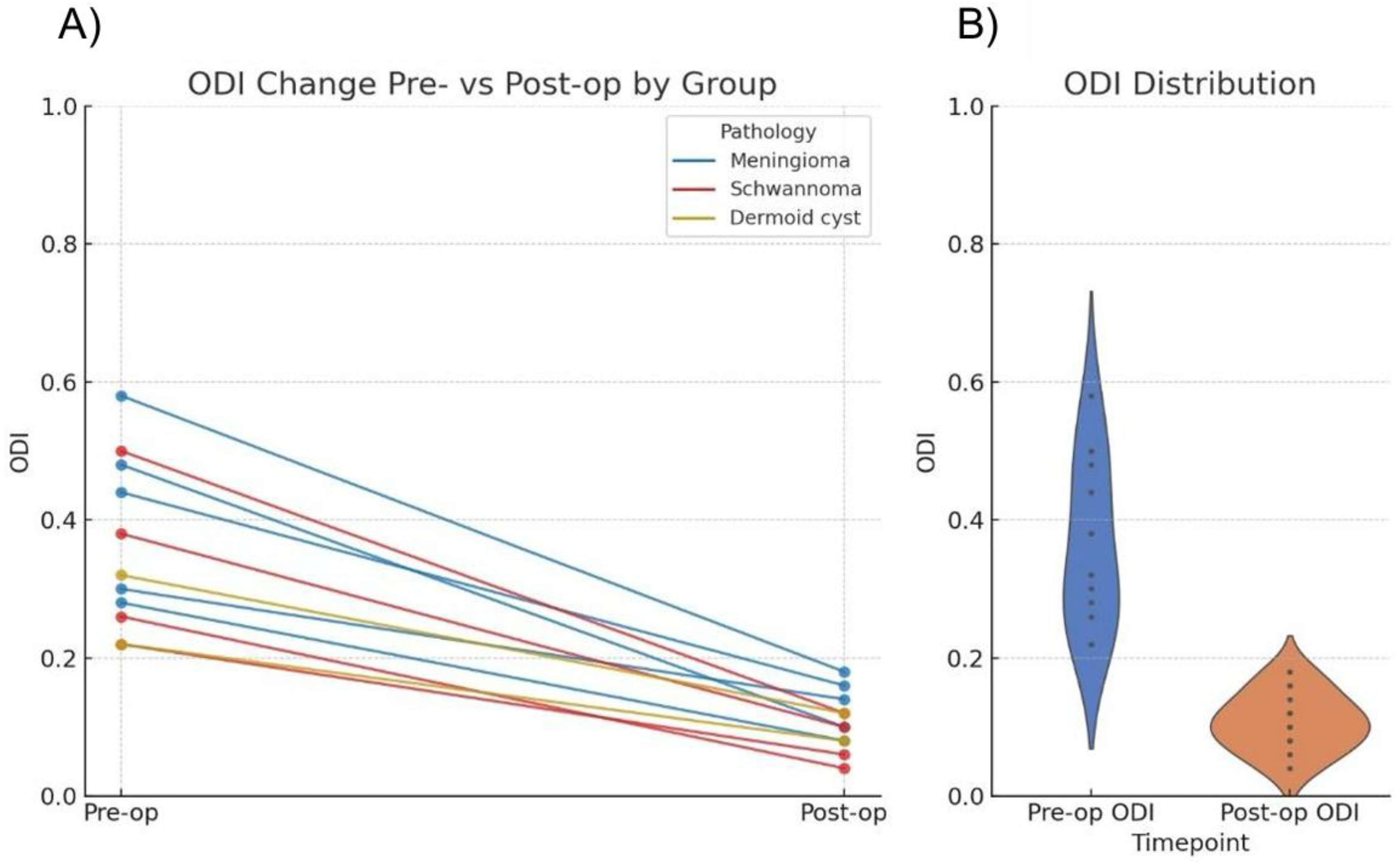

Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores were recorded for all patients. Preoperatively, all patients demonstrated moderate to severe disability (21–60% ODI scores). At 6-month follow-up, the majority achieved minimal disability status (0–20% ODI scores) (

Table 2).

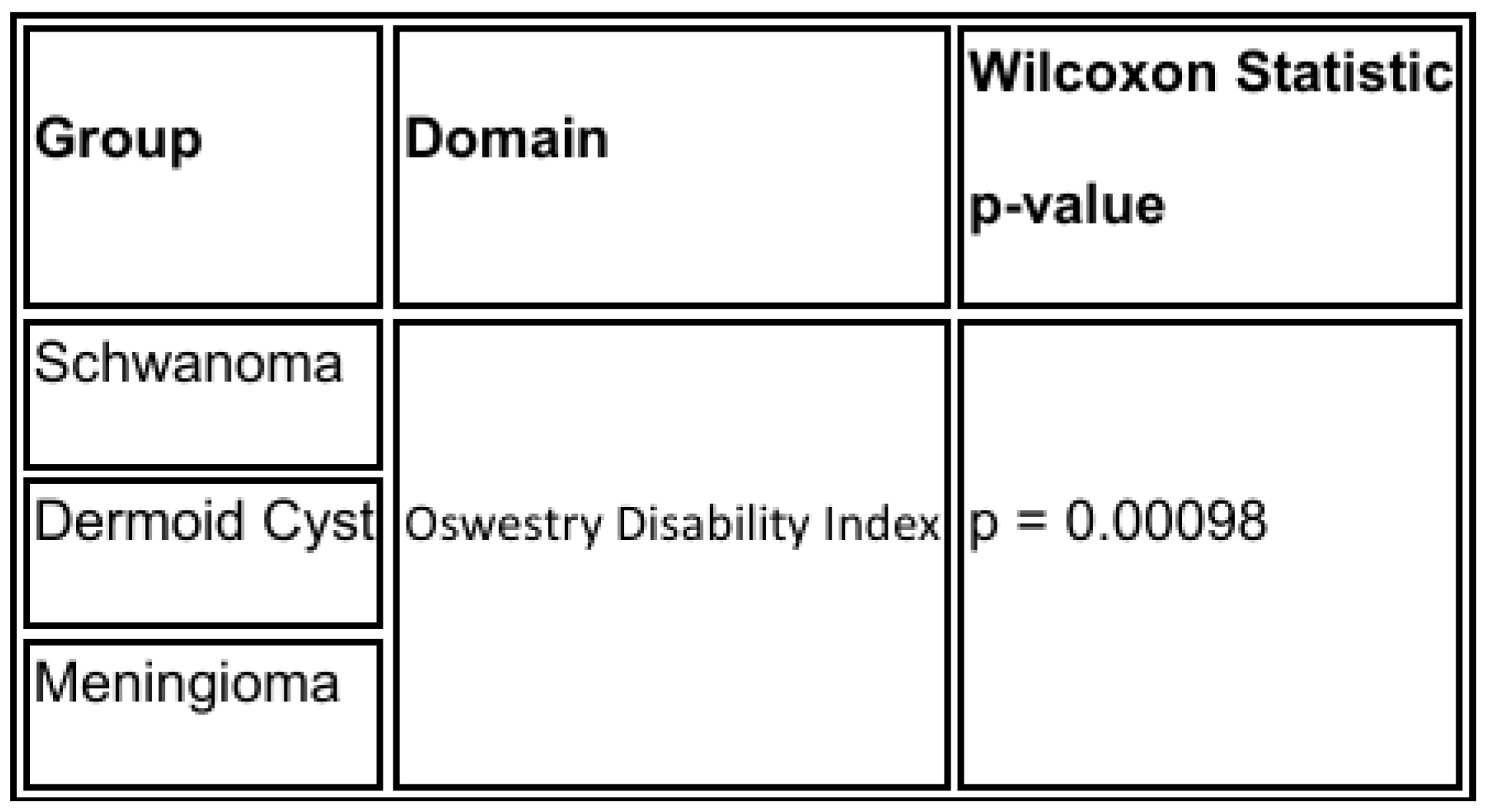

Regarding neurological deficits, all patients demonstrated improvement in motor and sensory symptoms during the 6-month follow-up period. No patient experienced new or worsened neurological deficits postoperatively. One patient in the schwannoma group developed transient postoperative paresthesia in the corresponding dermatome, which resolved spontaneously within 3 months. Comparison of the preoperative and postoperative Oswestry Disability Index % by Wilcoxon test resulted in a value of

p = 0.00098 (

Table 3) (

Figure 6).

4. Conclusions

We present a case series of 11 thoracolumbar extramedullary tumors solved by UBE technique with a step-by-step surgical explanation. Not so long ago, this type of tumor was treated with extensive muscle disruption and alteration of the spine biomechanics, resulting in instability or chronic low back pain. With the UBE technique, we improve all the possible outcomes for the patient and all with two 1cm incisions. Comparison of the preoperative and postoperative Oswestry Disability Index % by Wilcoxon test resulted in a value of p = 0.00098. In terms of global total resection, we achieved an outcome for open and tubular surgery. We recommend surgical experience of 100 degenerative cases before performing UBE tumor resection surgery to guarantee safety for the patient. The UBE technique is on develop ground and, as far as our concern in a short period of time, it will become the standard technique for spinal tumor resection surgery, and we will be pushing the frontier for unilateral biportal endoscopy spine surgery.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Ethical Approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required. In accordance with the norm IRB: 000123-2024.

Clinical Trial number

Not applicable.

Human ethics and consent to participate declarations

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

No Aknowledgments.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no Conflict of Interest.

References

- Cheng-Ying Lee, Cheol Woong Park. Exploring Unilateral Biportal Endoscopy for Lumbar Intradural Lesions: A Technical and Video Report on Benefits and Key Considerations, J Minim Invasive Spine Surg Tech 2025;10(Suppl 1):S81-S88. [CrossRef]

- Shao-Keh Hsu, Lunghsing Lee. Extramedullary Spinal Tumor Excision with the Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Spine Surgery Technique, J Minim Invasive Spine Surg Tech 2025;10(Suppl 1):S89-S97. [CrossRef]

- Sneha Chitra Balasubramanian, Ajith Rajappan Nair. Minimally Invasive Resection of Spinal Tumors with Tubular Retractor: Case Series, Surgical Technique, and Outcome, World Neurosurg. (2021) 149:e612-e621. [CrossRef]

- Wyatt L. Ramey, Jens R. Chapman. The ABC’s of Spinal Decompression: Pearls and Technical Notes, World Neurosurg. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Yang JC, Kim SG, Kim TW, Park KH. Analysis of factors contributing to postoperative spinal instability after lumbar decompression for spinal stenosis. Korean J Spine. 2013, 10: 149–54. [CrossRef]

- Kim JE, Choi DJ. Unilateral biportal endoscopic decompression by 30 endoscopy in lumbar spinal stenosis: technical note and preliminary report. J Orthop. 2018, 15: 366–71. [CrossRef]

- Park JH, Jun SG, Jung JT, Lee SJ. Posterior percutaneous endoscopic cervical Foraminotomy and Diskectomy with unilateral Biportal endoscopy. Orthopedics. 2017, 40: 779–83. [CrossRef]

- Choi CM, Chung JT, Lee SJ, Choi DJ. How I do it? Biportal endoscopic spinal surgery (BESS) for treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Acta Neurochir. 2016, 158: 459–63. [CrossRef]

- Park SM, Kim HJ, Kim GU, Choi MH, Chang BS, Lee CK, et al. Learning curve for lumbar decompressive laminectomy in Biportal endoscopic spinal surgery using the cumulative summation test for learning curve. World Neurosurg. 2019, 122: e1007-1007e1013. [CrossRef]

- Soliman HM. Irrigation endoscopic decompres- sive laminotomy. A new endoscopic approach for spinal stenosis decompression. Spine Journal 2015; 15: 2282-2289. [CrossRef]

- Park SM, Park J, Jang HS, Heo YW, Han H, Joong H, Chang BS, Lee CK, Yeom JS. Biportal endoscopic versus microscopic lumbar decompressive laminectomy in patients with spinal stenosis: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J 2020; 20: 156-165. [CrossRef]

- Song KS, Lee CW, Moon JG. Biportal endoscopic spinal surgery for bilateral lumbar foraminal decompression by switching surgeon’s position and primary 2 portals: A report of 2 cases with technical note. Neurospine 2019; 16: 138-147. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Guan T, Tian F, Liu X. Comparision of biportal endoscopic and microscopic decompression in treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis: a comparative study protocol. Medicine. 2020;99(30):e21309. [CrossRef]

- Heo DH, Kim JS, Park CW, Quillo-Olvera J, Park CK. Contralateral sublaminar endoscopic approach for removal of lumbar juxtafacet cysts using percutaneous biportal endoscopic surgery: technical report and preliminary results. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:474–9. [CrossRef]

- G. X. Lin, P. Huang, V. Kotheeranurak et al.,“A systematic review of unilateral Biportal endoscopic spinal surgery: preliminary clinical results and complications,” World Neurosurgery, vol. 125, no. 18, pp. 425–432, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Kang, H. J. Park, J. H. Hwang, J. E. Kim, and H. J. Chung, “Safety evaluation of Biportal endoscopic lumbar discectomy: assessment of cervical epidural pressure during surgery,” Spine, vol. 45, no. 20, pp. E1349–E1356, 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).