Thought Experiment

Here is a question I have found on Quora: “If you are traveling towards a planet that is 10 light years (ly) away, and you send a light signal to the planet, and at the same time, the planet sends a light signal towards you, how long will it take for the signals to meet?” As the spaceship is moving, when the signals meet, the distance between the planet and the spaceship is less than 10 ly.

Now we should replace the signals by photons, and we need to draw spacetime diagrams. For the preprint version, I will remind the readers of several points. Special relativity is constructed on two postulates. First postulate: the speed of light is the same (constant) with the planet as a reference and with the spaceship as a reference, even if the spaceship is moving towards the planet. Second postulate: we can consider the planet as immobile, and it will become the reference; but we can also consider the spaceship as immobile, and it will become the reference. In a Minkowski spacetime diagram, the horizontal coordinate is a distance (x) and the vertical coordinate is time (t). Time can only increase. Then inside the coordinate (t,x) of an immobile system, one can draw the coordinate (t’,x’) of a moving system (observed from the immobile system). A photon travels one light year in one year, hence the dashed trajectory (45°) drawn on these diagrams. As the speed of light is the same for the planet and the spaceship, the photon trajectories are valid for both sets of coordinates; that is one beauty of Minkowski spacetime diagrams.

First let’s draw the spacetime diagram with the planet immobile

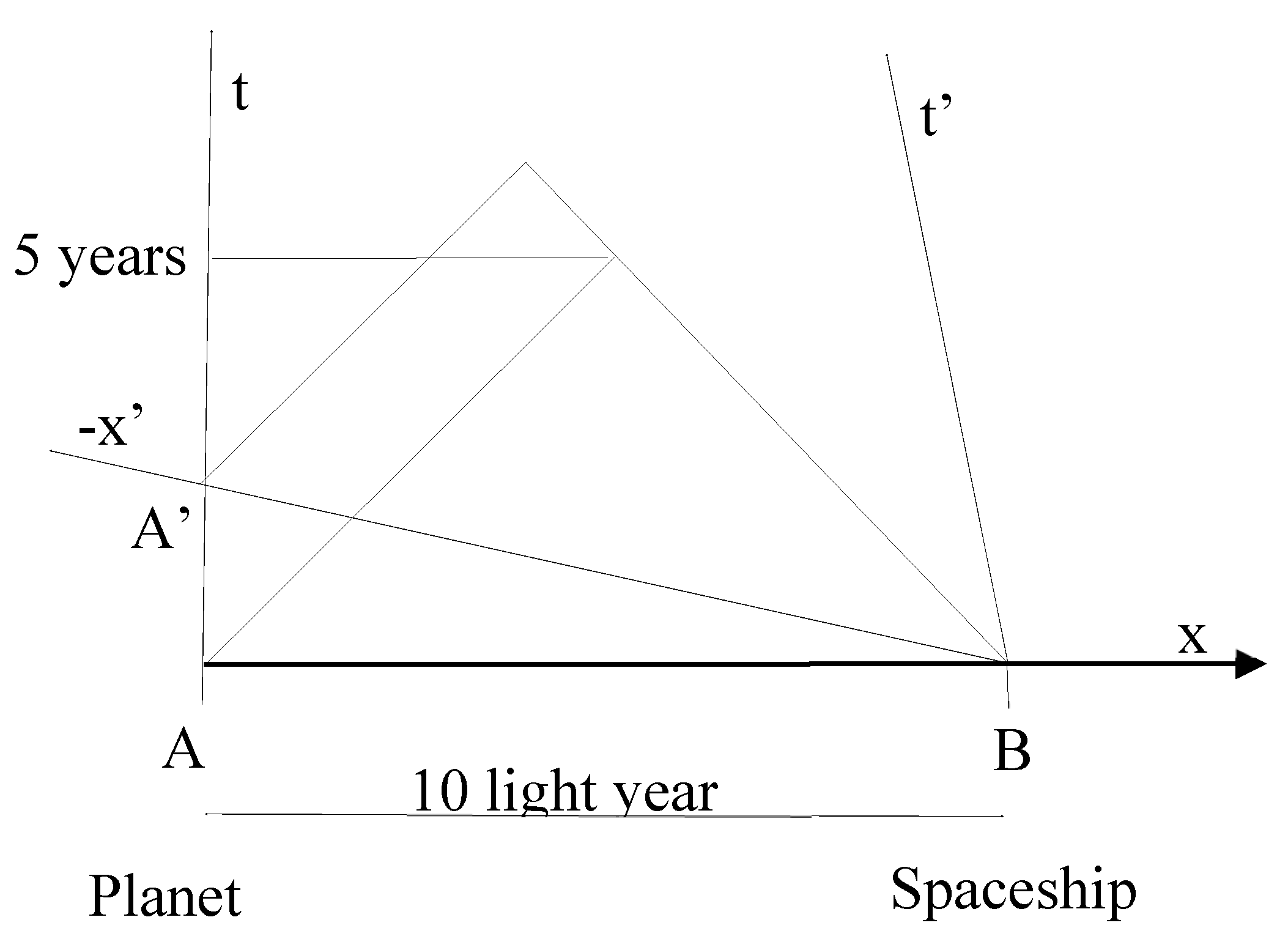

Figure 1:

The planet is on the left, and its coordinates are Cartesian (right angle) with

x and

t. For this diagram, the coordinates of the spaceship (on the right) are not Cartesian (-

x’ and

t’). Due to the motion, the spaceship coordinates are no longer Cartesian. The trajectory of the spaceship follows the

t’ axis. As the distance between

t and

t’ axis is smaller at the top than at the bottom, it shows that the spaceship is moving towards the planet: the distance is diminishing, starting from 10 ly. Everything that happens on the

x axis occurs at the same time for the planet, because

t doesn’t move. Similarly, everything that happens in the

x’ axis occurs at the same time for the spaceship. Clearly the events when photons

A from the planet and

B from the spaceship leave simultaneously, as seen from the planet (on

x axis), it is not simultaneous from the spaceship (because

A is not on the -

x’ axis). This is because the

x and the

x’ axis are not parallel. You can see that one meeting point of the photons is 5 years and 5 ly in the planet coordinates. There is a point

A’ where a second photon leaves the planet.

A’ is at the interception between

x’ and

t axis. We need the next diagram where the spaceship is immobile (

Figure 2) to understand the second photon:

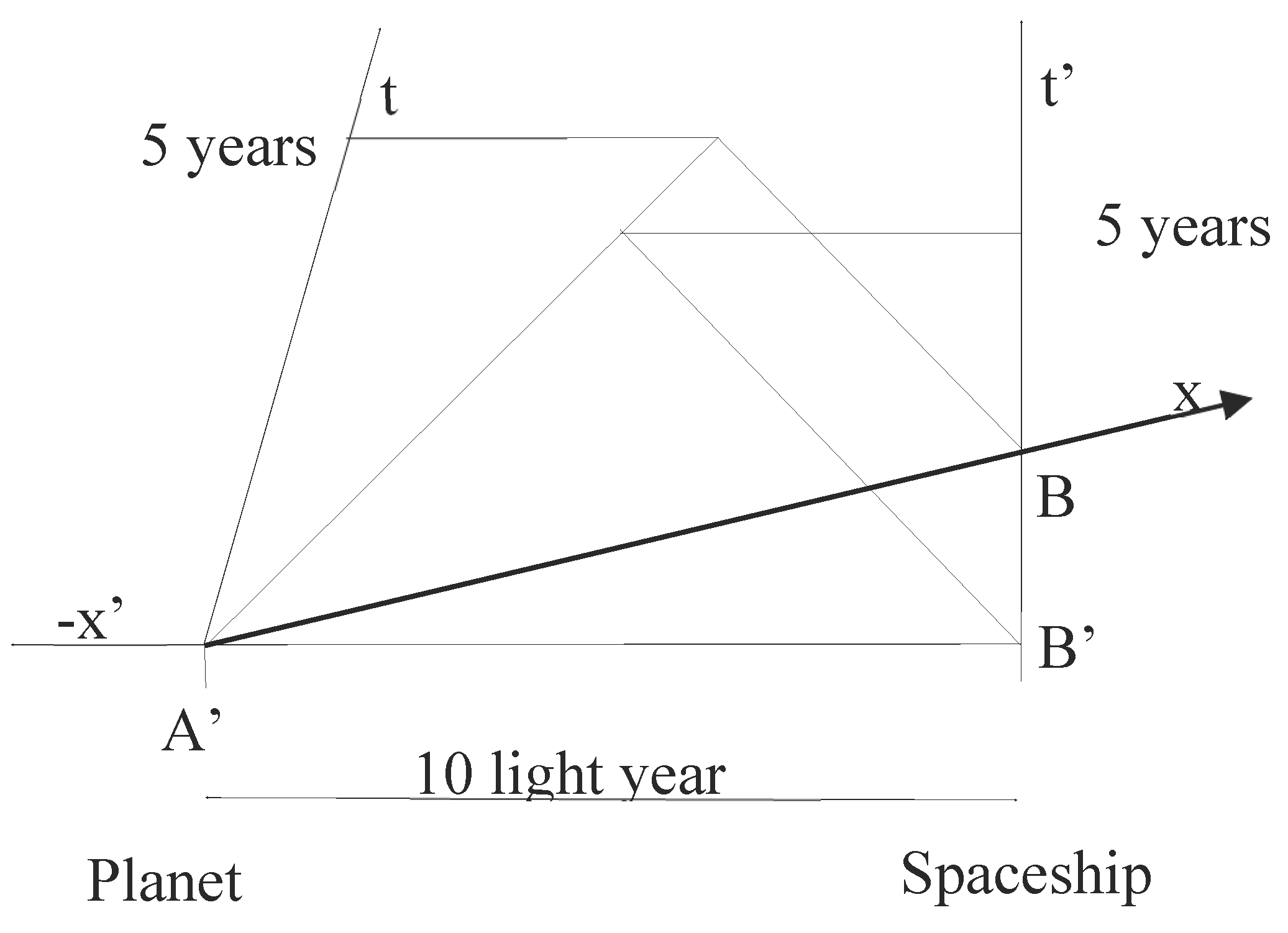

You can see the same result: one meeting point of the photons is 5 years and 5 ly in the spaceship coordinates. If the spaceship observes the simultaneity of the events of photons

A’ and

B’ leaving planet and spaceship respectively, the same simultaneity is lacking for the planet. You can recognise

A’ at the intersection of the -

x’ axis and the

t axis. That is when the

A’ photon leaves the planet for the simultaneity observed by the spaceship on

Figure 1. Point

A should be somewhere else, a logical guess would be below

A’ because of

Figure 1.

B is obviously when a photon should leave the spaceship for the planet to observe simultaneity of the photons leaving both the planet and the spaceship.

B in

Figure 2 is equivalent to

A’ in

Figure 1.

B in

Figure 2 allows us to reconstruct

Figure 1 in

Figure 2. The problem is that the meeting point of the photons of the reconstructed Fig 1 is not at the same place as the meeting point of

Figure 2. To me that is the new paradox: where do the photons meet?

The thought experiment requires two photons emitted from one place because of the “at the same time”.

Figure 2 the spaceship should send 2 photons

B and

B’ separated by a time interval (time has moved upwards);

B is needed for the planet to observe the meeting of the two photons at 5 light years distant from the planet and

B’ is needed for the spaceship to observe the collision at 5 light years distant from the spaceship. The need for sending two photons is due to the

x and

x’ axis which are not parallel. Two photons

A and

A’ are also sent from the planet, but on

Figure 2,

A and

A’ are sent at the same time while on

Figure 1,

A and

A’ are sent at two different times. To me that is a new paradox: same time or different time?

If we consider that Minkowski diagrams are wrong in the sense that the moving frame representation is somehow incorrect. We can still represent the experiment in one frame of reference or the other. So, forget about the second emitted photon and let’s keep only the isosceles triangle. But that doesn’t make sense either. Both objects can claim the meeting point is at 5ly which leads to two different meeting points because, at the time of the meeting, the distance between the planet and the spaceship is smaller than 10 ly. As both references can be considered as immobile, who is right? Where is the meeting point?