Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

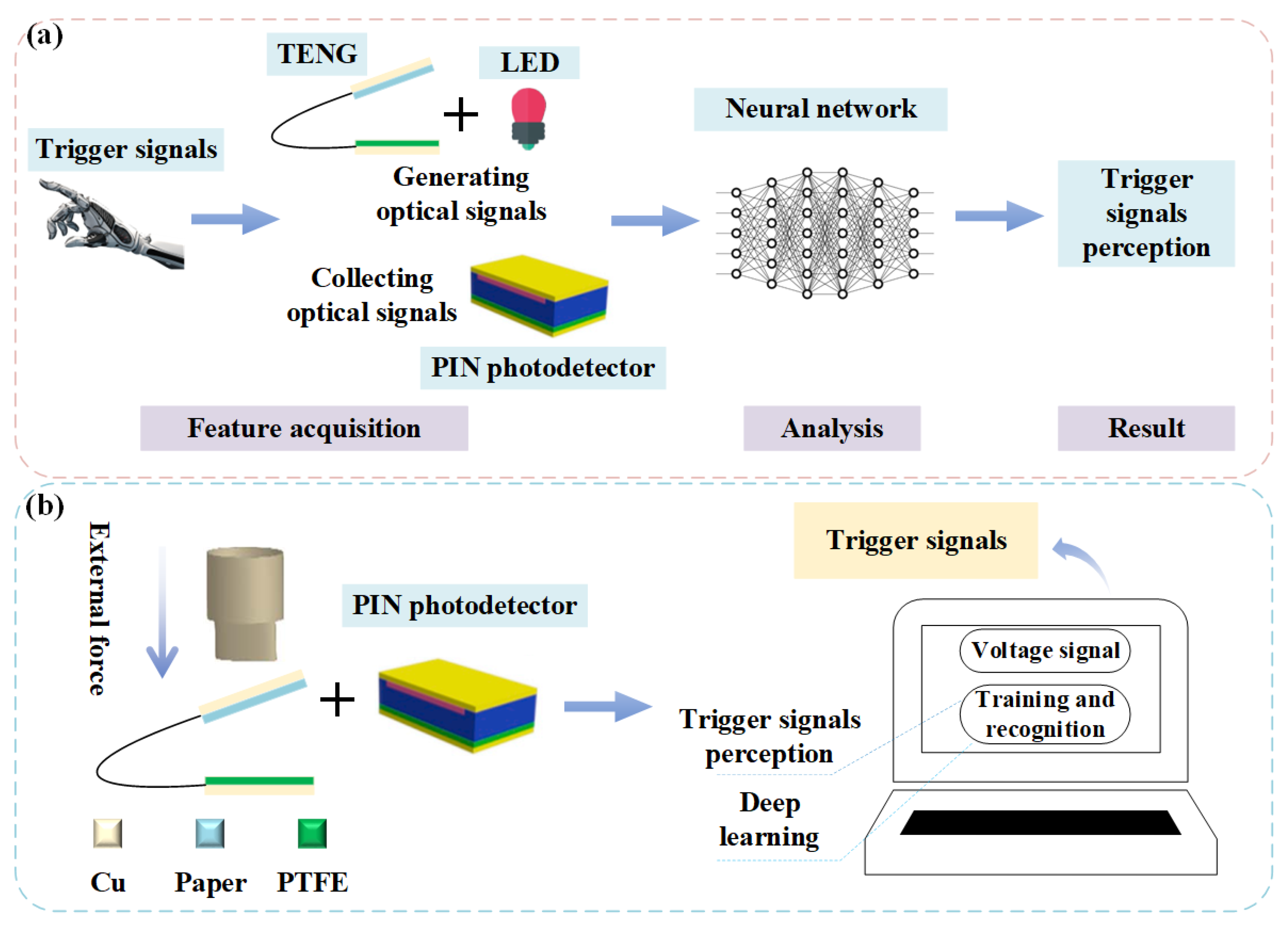

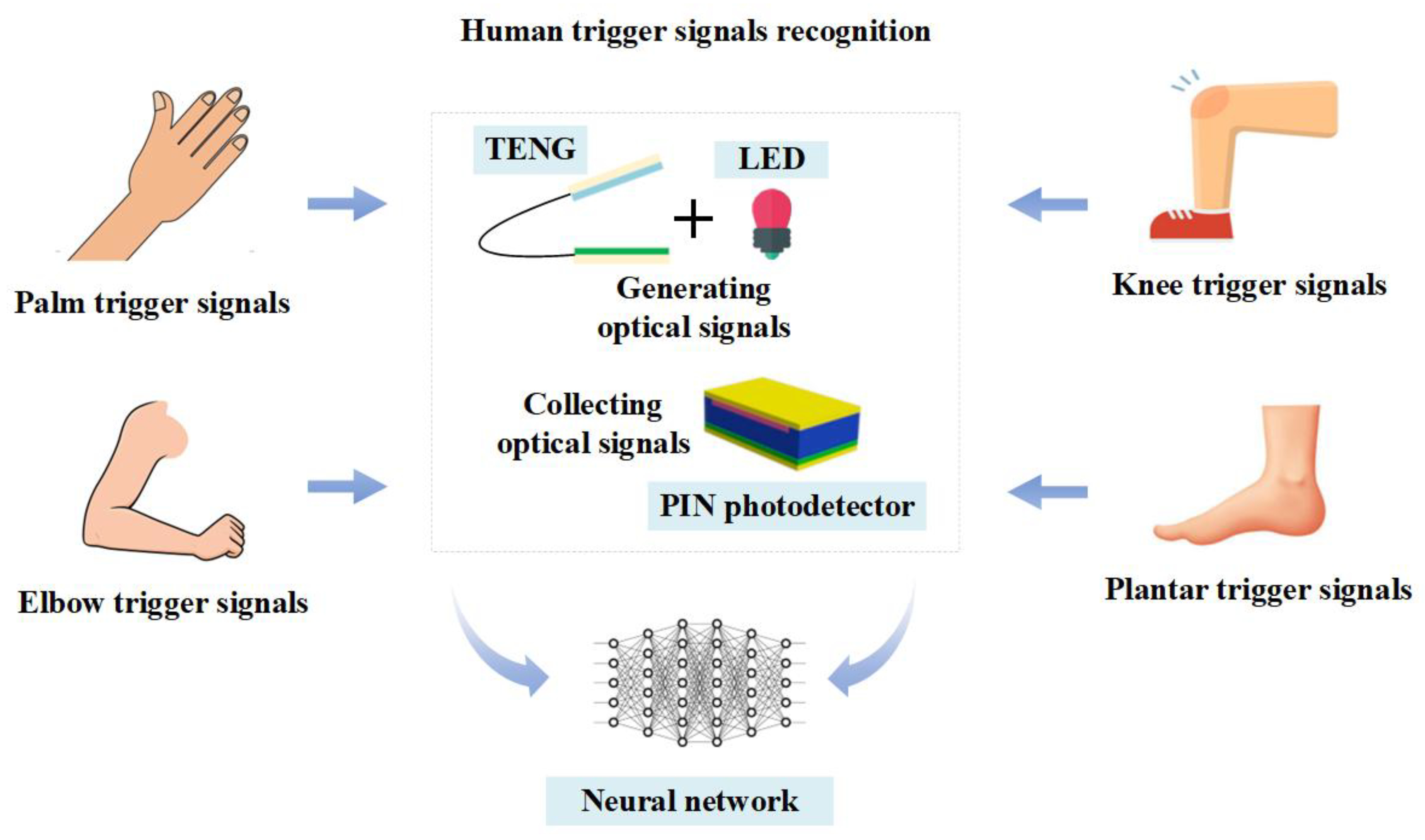

2. System Structure Design

3. Device Fabrication

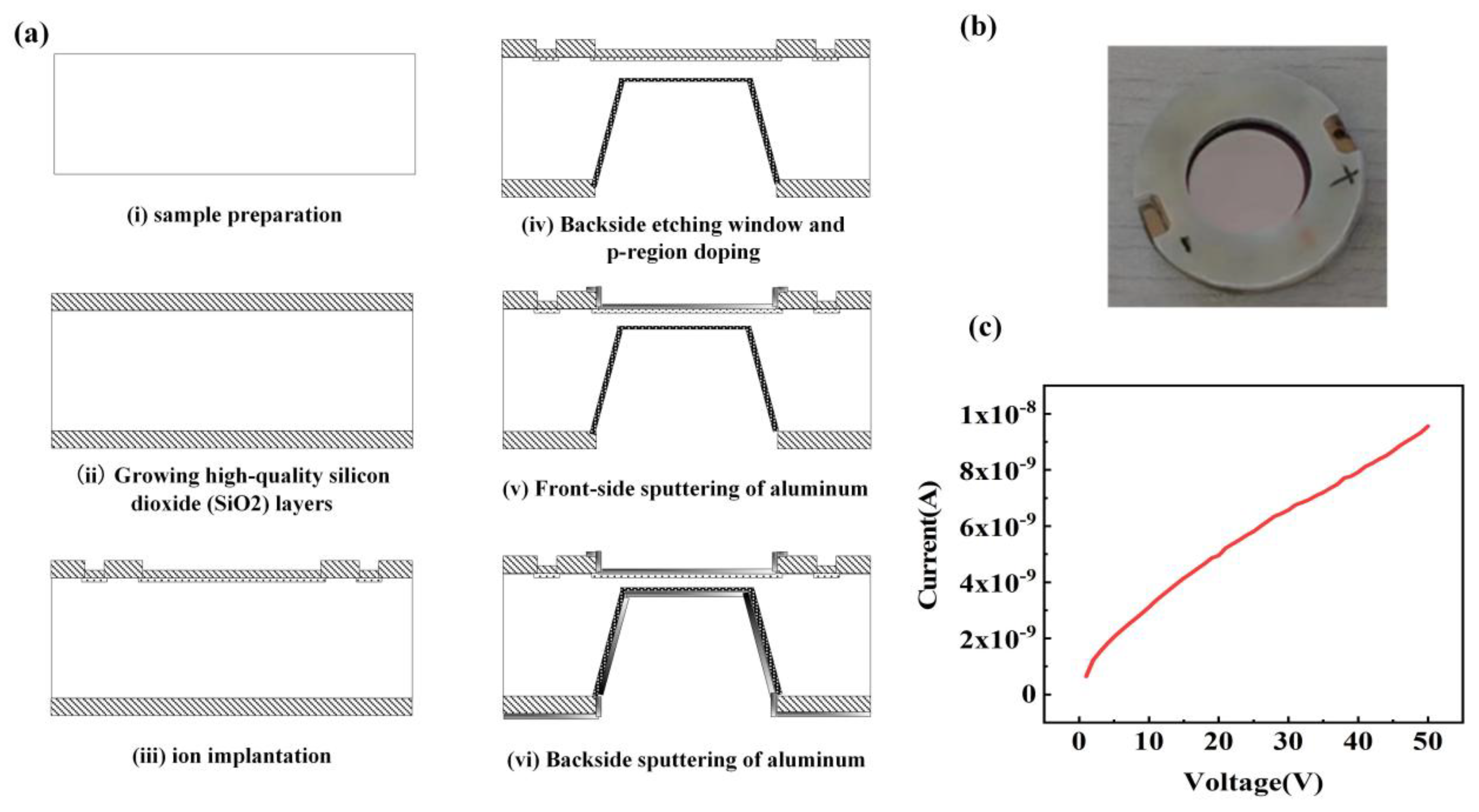

3.1. Fabrication of Silicon PIN Detector

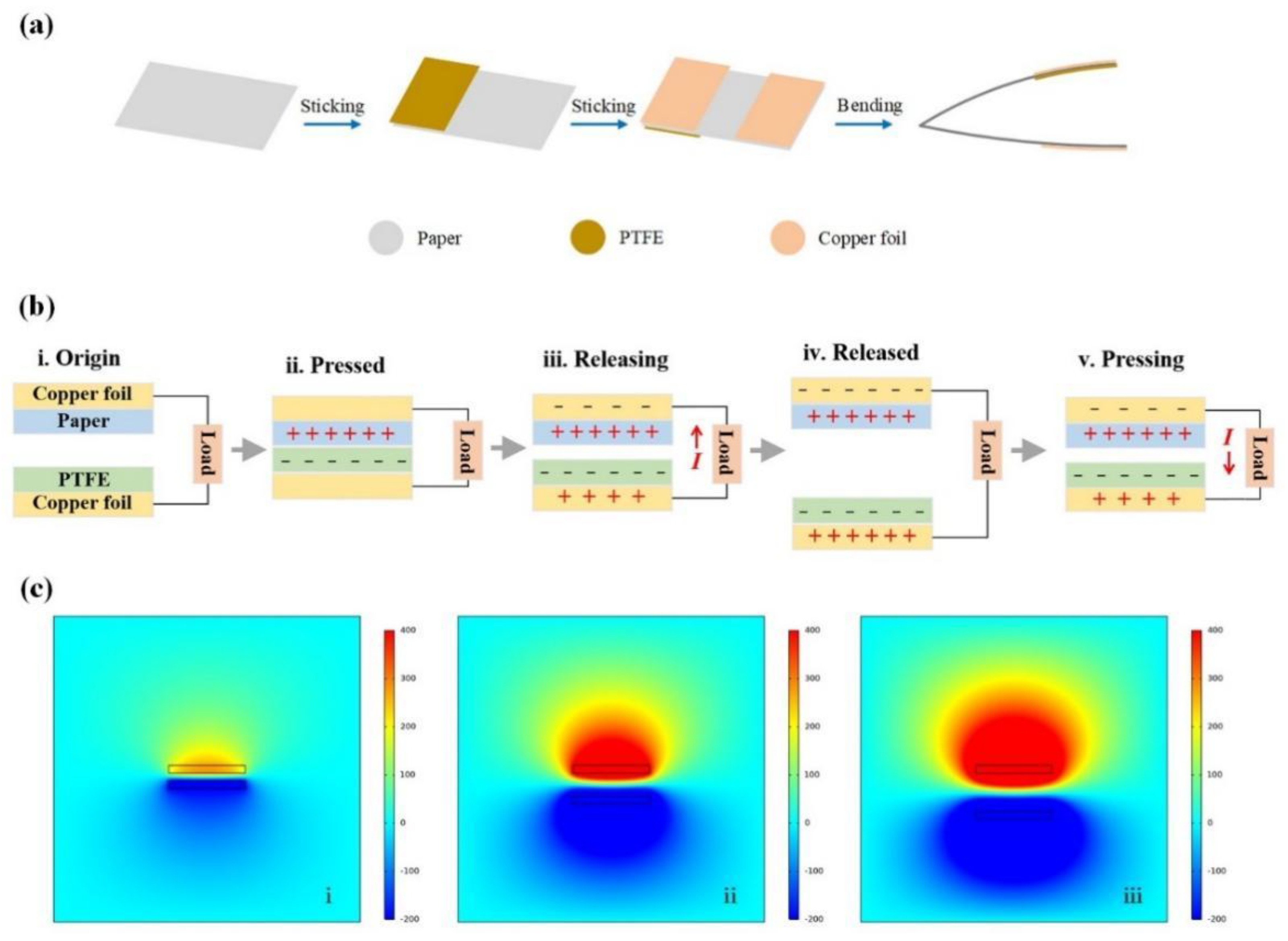

3.2. Preparation of TENG

4. Triggered Signals Recognition Based on Self-Powered Sensing System and Neural Network

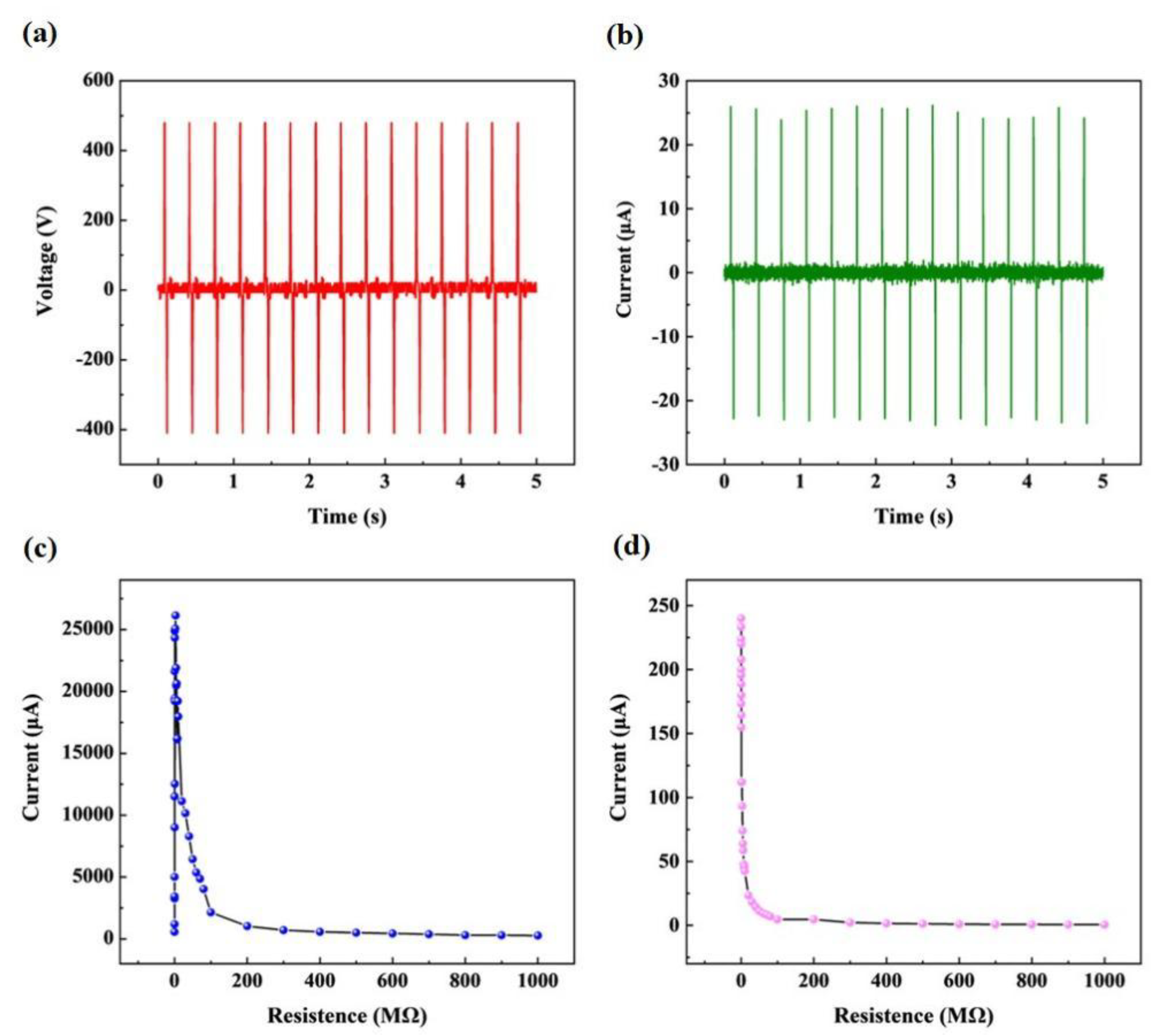

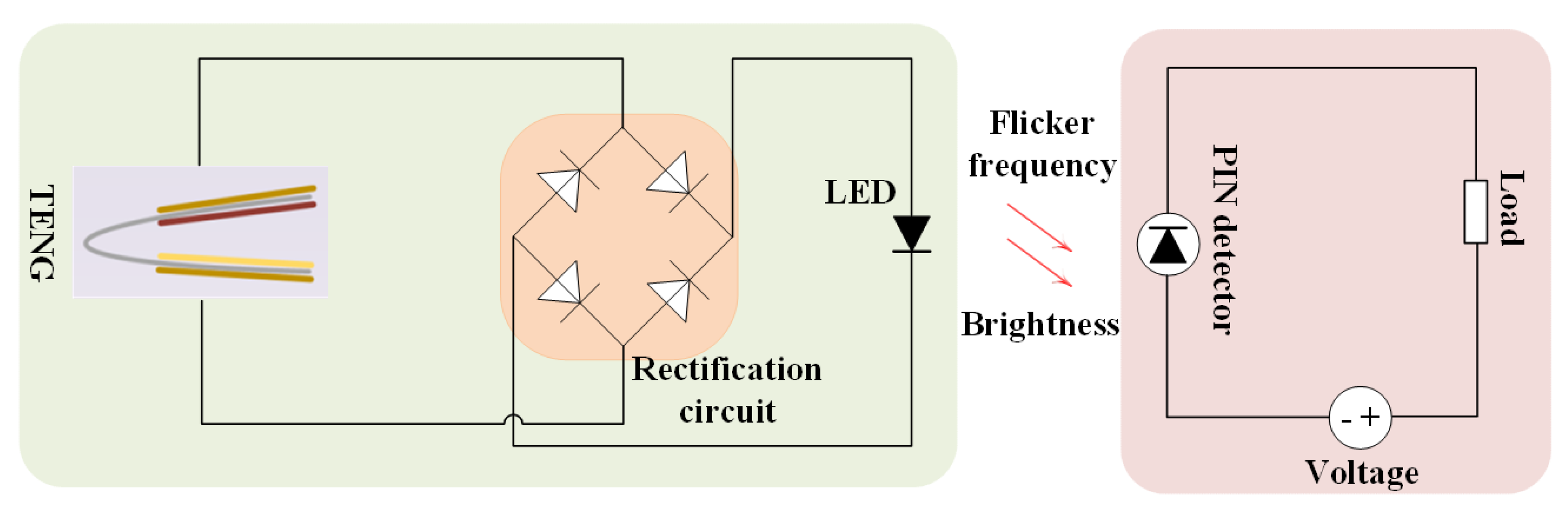

4.1. The Self-Powered Sensing System Based on TENG and Silicon PIN Detector

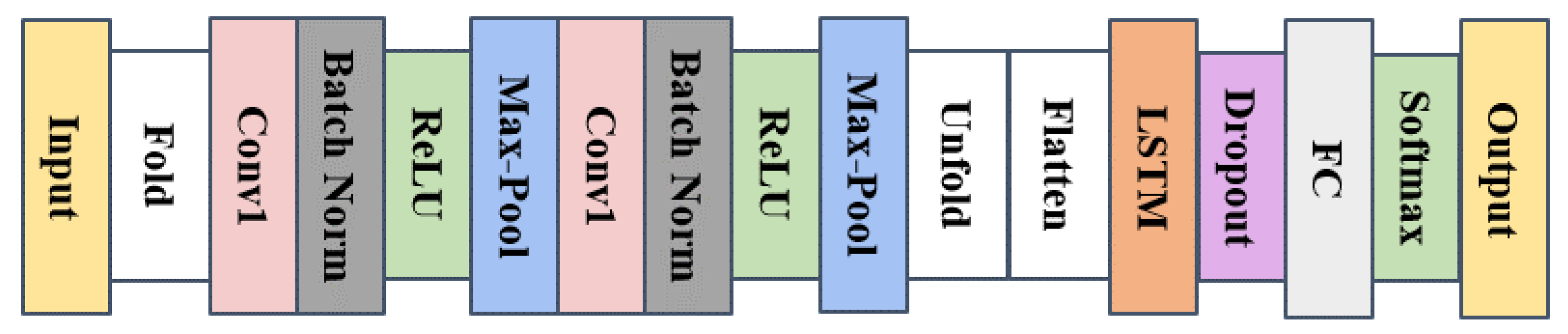

4.2. Neural Network Model

5. Experiment and Result Analysis

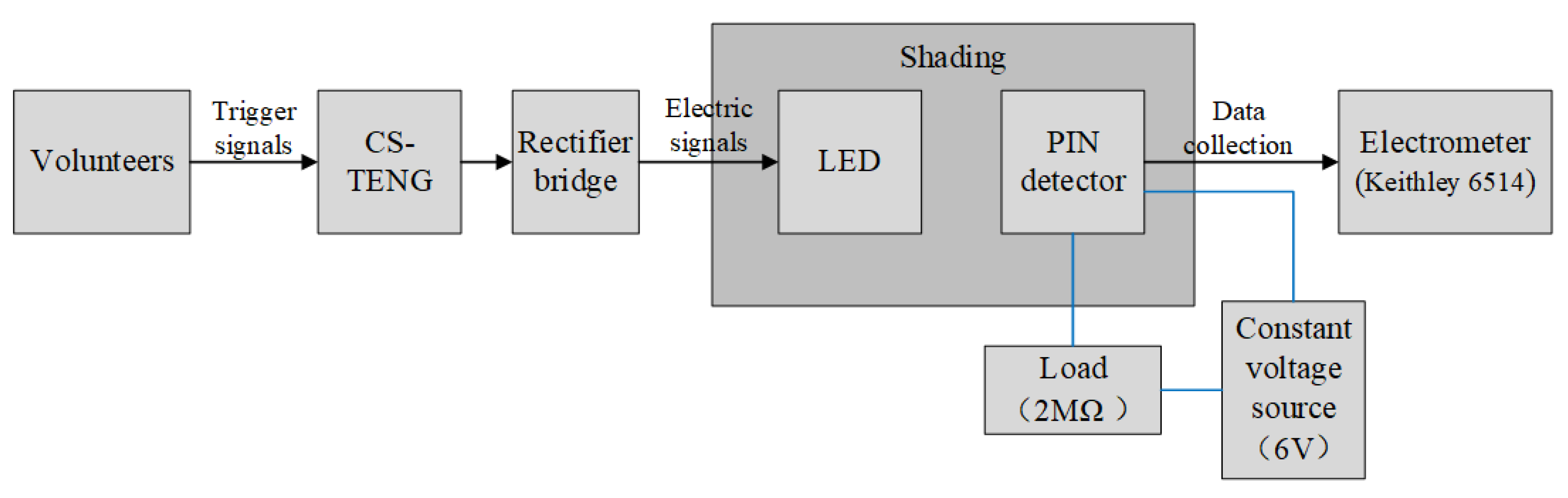

5.1. Experimental Data Collection

5.2. Data Processing

5.3. Analysis of Results

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Zhu Z, Pu M, Jiang M; et al. Bonding Processing and 3D Integration of High-Performance Silicon PIN Detector for ΔE-E telescope[J]. Processes 2023, 11, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu B, Zhao K, Yang T; et al. Process effects on leakage current of Si-PIN neutron detectors with porous microstructure[J]. physica status solidi (a) 2017, 214, 1600900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li H X, Li Z K, Wang F C; et al. Application of stratified implantation for silicon micro-strip detectors[J]. Chinese Physics C 2015, 39, 066005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geis M W, Spector S J, Grein M E; et al. CMOS-compatible all-Si high-speed waveguide photodiodes with high responsivity in near-infrared communication band[J]. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2007, 19, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehme M, Werner J, Kasper E; et al. High bandwidth Ge pin photodetector integrated on Si[J]. Applied physics letters.

- Abdel N S, Pallon J, Ros L; et al. Characterizations of new ΔE detectors for single-ion hit facility[J]. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2014, 318, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina R, Alinia P, Ghasemzadeh H; et al. Multi-sensor fusion in body sensor networks: State-of-the-art and research challenges[J]. Information Fusion 2017, 35, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng H, Wang Z, Chen Y; et al. Multi-sensor filtering fusion with parametric uncertainties and measurement censoring: Monotonicity and boundedness[J]. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2021, 69: 5875-5890.

- Wang Y, Li J, Viehland D. Magnetoelectrics for magnetic sensor applications: Status, challenges and perspectives[J]. Materials Today 2014, 17, 269–275.

- Mittal A, Davis L S. A general method for sensor planning in multi-sensor systems: Extension to random occlusion[J]. International journal of computer vision 2008, 76, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. Intelligent manufacturing production line data monitoring system for industrial internet of things[J]. Computer communications 2020, 151, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, M. An industrial Wireless Sensor Networks framework for production monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Istanbul, Turkey, 1–4 June 2014; pp. 1442–1447. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat H, Griffiths T, Brennan D; et al. The state-of-the-art of sensors and environmental monitoring technologies in buildings[J]. Sensors 2019, 19, 3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mois G, Folea S, Sanislav T. Analysis of three IoT-based wireless sensors for environmental monitoring[J]. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2017, 66, 2056–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Khan K, Zou J; et al. Recent advances in emerging 2D material-based gas sensors: Potential in disease diagnosis[J]. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2019, 6, 1901329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler J, Choi S W, Tewari M. Real-time, personalized medicine through wearable sensors and dynamic predictive modeling: A new paradigm for clinical medicine[J]. Current opinion in systems biology 2020, 20, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreu-Perez J, Leff D R, Ip H M D; et al. From wearable sensors to smart implants-–toward pervasive and personalized healthcare[J]. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2015, 62, 2750–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Xiong H, Zhang J; et al. From personalized medicine to population health: A survey of mHealth sensing techniques[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 15413–15434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu M, Yi Z, Yang B; et al. Making use of nanoenergy from human–Nanogenerator and self-powered sensor enabled sustainable wireless IoT sensory systems[J]. Nano Today, 1010.

- Zhang H, Wang J, Xie Y; et al. Self-powered, wireless, remote meteorologic monitoring based on triboelectric nanogenerator operated by scavenging wind energy[J]. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2016, 8, 32649–32654. [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Gan B, Jiang T; et al. Nanopillar arrayed triboelectric nanogenerator as a self-powered sensitive sensor for a sleep monitoring system[J]. Acs Nano 2016, 10, 8097–8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao H, Hu M, Ding J; et al. Investigation of contact electrification between 2D MXenes and MoS2 through density functional theory and triboelectric probes[J]. Advanced Functional Materials 2023, 33, 2213410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Xu Q, Li H; et al. Self-powered electrodeposition system for Sub-10-Nm silver nanoparticles with high-efficiency antibacterial activity[J]. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2022, 13, 6721–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo X, He J, Zheng Y; et al. High-performance triboelectric nanogenerator based on theoretical analysis and ferroelectric nanocomposites and its high-voltage applications[J]. Nano Research Energy 2023, 2, e9120074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Long, Wang; et al. A Hybridized Power Panel to Simultaneously Generate Electricity from Sunlight, Raindrops, and Wind around the Clock[J]. Advanced Energy Materials.

- Li X, Luo J, Han K; et al. Stimulation of ambient energy generated electric field on crop plant growth[J]. Nature Food.

- Ren Z, Y Ding, Nie J; et al. Environmental Energy Harvesting Adapting to Different Weather Conditions and Self-Powered Vapor Sensor Based on Humidity-Responsive Triboelectric Nanogenerators[J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

- Lin H, He M, Jing Q; et al. Angle-shaped triboelectric nanogenerator for harvesting environmental wind energy[J]. Nano Energy 2019, 56, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng Y, Zhang L, Zheng Y; et al. Leaves based triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) and TENG tree for wind energy harvesting[J]. Nano Energy 2019, 55, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Ryu H, Lee J H; et al. Triboelectric Nanogenerators: High Permittivity CaCu3Ti4O12 Particle-Induced Internal Polarization Amplification for High Performance Triboelectric Nanogenerators (Adv. Energy Mater. 9/2020)[J]. Advanced Energy Materials 2020, 10, 2070040.

- Lin Z H, Cheng G, Lin L; et al. Water–solid surface contact electrification and its use for harvesting liquid-wave energy[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2013, 52, 12545–12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu G, Su Y, Bai P; et al. Harvesting water wave energy by asymmetric screening of electrostatic charges on a nanostructured hydrophobic thin-film surface[J]. ACS nano 2014, 8, 6031–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen J, Yang J, Li Z; et al. Networks of triboelectric nanogenerators for harvesting water wave energy: A potential approach toward blue energy[J]. ACS nano 2015, 9, 3324–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren Z, Zheng Q, Wang H; et al. Wearable and Self-Cleaning Hybrid Energy Harvesting System based on Micro/Nanostructured Haze Film[J]. Nano Energy 2019, 67, 104243. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Liu T, Wu J; et al. Energy conversion analysis of multilayered triboelectric nanogenerators for synergistic rain and solar energy harvesting[J]. Advanced Materials 2022, 34, 2202238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu Q, Fang Y, Jing Q; et al. A portable triboelectric spirometer for wireless pulmonary function monitoring[J]. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2021, 187, 113329. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Cheng L, Yuan M, Wang Z, Zhang L, Qin Y* and Jing T. An electrospun nanowire-based triboelectric nanogenerator and its application in a fully self-powered UV detector. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 7842–7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang Cheng, Haiwu Zheng, Feng Yang, Lei Zhao, Mingli Zheng, Junjie Yang, Huaifang Qin, Zuliang Du*, ZhongLin Wang*. Managing and maximizing the output power of atriboelectric nanogenerator by controlled tip–electrode air-discharging and application for UV sensing. Nano Energy 2018, 44, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han Lei, Peng Mingfa, Wen Zen, Liu Yina, Zhang Yi, Zhu Qianqian, Lei Hao, Liu Sainan, Zheng Li*, Sun Xuhui*, Li Hexing*. Self-driven photodetection based on impedance matching effect between a triboelectric nanogenerator and a MoS2 nanosheets photodetector. Nano Energy 2019, 59, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Xia K, Li T; et al. Self-powered silicon PIN photoelectric detection system based on triboelectric nanogenerator[J]. Nano Energy 2020, 69, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Bu T, Li Y; et al. Multidimensional force sensors based on triboelectric nanogenerators for electronic skin [J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 56320–56328. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Liu D, Zhao Z; et al. A fully self-powered vibration monitoring system driven by dual-mode triboelectric nanogenerators [J]. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 2475–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li C, Wang Z, Shu S; et al. A self-powered vector angle/displacement sensor based on triboelectric nanogenerator [J]. Micromachines 2021, 12, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng Y, Xiang H, Zheng N; et al. Flexible triboelectric nanogenerator for human motion tracking and gesture recognition [J]. Nano Energy, 1066.

- Zhu Z, Li B, Zhao E; et al. Self-powered silicon PIN neutron detector based on triboelectric nanogenerator[J]. Nano Energy, 1076.

| Layers | Types | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Input | - |

| 2 | Sequence Folding Layer | - |

| 3 | Convolution Layer 1 | 64 2×1 convolutions with stride [1 x 1] |

| 4 | Batch Normalization 1 | - |

| 5 | ReLU | - |

| 6 | Max-pool 1 | 2×1 pooling kernel with stride [2 x 1] |

| 7 | Convolution Layer 2 | 32 2×1 convolutions with stride [1 x 1] |

| 8 | Batch Normalization 2 | - |

| 9 | ReLU | - |

| 10 | Max-pool 2 | 2×1 pooling kernel with stride [2 x 1] |

| 11 | Sequence Unfolding Layer | - |

| 12 | Flatten Layer | - |

| 13 | LSTM Layer 1 | LSTM with 32 hidden units |

| 14 | Dropout | 25% dropout |

| 15 | Fully Connected | - |

| 16 | Softmax | - |

| 17 | Classification | - |

| Models | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 88.01 | 88.69 | 88.12 | 87.94 |

| LSTM | 87.53 | 88.24 | 87.64 | 87.64 |

| CNN-LSTM | 92.92 | 93.35 | 93.11 | 92.94 |

| Models | Types | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | M | 97.96 | 96.39 | 97.17 |

| E | 69.71 | 84 | 76.19 | |

| W | 86.44 | 77.27 | 81.60 | |

| R | 97.91 | 97.10 | 97.50 | |

| LSTM | M | 97.37 | 94.47 | 95.90 |

| E | 68.94 | 83.94 | 75.70 | |

| W | 85.71 | 76.83 | 81.03 | |

| R | 98.10 | 97.73 | 97.91 | |

| CNN-LSTM | M | 95.18 | 95.56 | 95.37 |

| E | 86.46 | 90.83 | 88.59 | |

| W | 92.16 | 87.85 | 89.95 | |

| R | 97.88 | 99.14 | 98.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).