1. Introduction

Viral infections during pregnancy are a significant cause of severe complications and mortality for both mothers and fetuses worldwide. These infections can adversely affect the health of the pregnant woman, the fetus, or the newborn, potentially leading to long-term functional impairments and malformations. Infectious agents can reach the fetus in several ways: transplacentally, perinatally (through vaginal secretions or blood), or postnatally (via breast milk). Congenital and perinatal infections are well-recognized contributors to neonatal morbidity, mortality, and stillbirths, even in high-income countries [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The clinical manifestations of neonatal infections vary depending on the specific viral agent and the gestational age at which the infection is acquired. Generally, the risk of these infections is inversely proportional to the gestational age at acquisition, with some infections leading to congenital malformations.

The study of the impact of viral infections during pregnancy is becoming increasingly important due to the potential threat of epidemic outbreaks from both existing and emerging infectious pathogens. Viral infections such as parvovirus (B19V) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) can lead to serious complications, including anemia, spontaneous abortion, premature birth, stillbirth, and an increased risk of co-infection with other pathogenic microorganisms. Understanding these risks is essential for developing effective approaches to the diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and monitoring of viral diseases during pregnancy [

1,

5].

B19V is a single-stranded DNA virus from the Parvoviridae family and Erythrovirus genus, primarily causing erythema infectiosum, commonly called fifth disease. While a significant percentage of adults may experience asymptomatic infections, the consequences of B19V infection during pregnancy can be severe. These may include spontaneous abortion, fetal anemia, hydrops fetalis, myocarditis, and intrauterine fetal death [

1]. Research indicates that between 50% and 65% of women of reproductive age have developed immunity to this virus [

6,

7,

8]. During epidemic outbreaks, it is estimated that 20% to 30% of seronegative women—those who have not previously been exposed to the virus—will contract the infection. Fetal hydrops, a serious condition, can occur due to several mechanisms. Anemia is a notable risk, as B19V particles can cross the placenta and inhibit fetal erythropoiesis, leading to aplastic crisis and subsequent congestive anemia, hypoxia, and heart failure [

1,

6,

7,

8]. The probability of experiencing these complications after 20 weeks of gestation is approximately 2.3% [

9,

10].

CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus that belongs to the beta-herpesvirus group and is one of the most common congenital viral infections, presenting with a range of clinical manifestations. In most cases, CMV infection is asymptomatic (90%), but it can occasionally present as a mild febrile illness with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, myalgia, rhinitis, pharyngitis, and headache [

11]. Among pregnant individuals, CMV has a seroprevalence of 42.3–68.3% in developed countries. In addition to the main clinical manifestations of the disease, the virus can also lead to anemia and alterations in serum iron metabolism [

12,

13,

14]. The risk of transmission of the infection to the fetus is highest during primary infection, estimated at 30%-40% [

15].

The gold standard in diagnosing fetal anemia is the measurement of the middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (MCA-PSV) during 18–35 weeks’ gestation. MCA-PSV Doppler is a standard (routine-in-risk) test in specialized prenatal/maternal–fetal medicine units, primarily for pregnancies with known or suspected risk of fetal anemia, such as alloantibodies in the mother, maternal viral infection, abnormal fetal heart rate etc.

Laboratory diagnosis and established methods for confirming B19V and CMV infections rely on serological tests and molecular techniques. Testing for specific B19V and CMV IgM antibodies, combined with the presence of viral DNA, provides definitive evidence of acute infection, which is particularly important for monitoring cases of pathological pregnancy [

15]. To study the dynamics of viral evolution and genomic heterogeneity within and between B19V or CMV isolates, next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques are increasingly utilized.

Taking all of this into consideration, the present study aimed to assess the prevalence of B19V and CMV infections in pregnant women with fetal anemia and/or effusions, evaluate the utility of routine molecular and serological screening, and investigate its role in pregnancy follow-up.

2. Results

Over a period of twelve months, 13 pregnant women with fetal anemia and/or effusions were screened for two of the most common viral agents that can cause congenital infections if transmitted from a pregnant woman to her baby: B19V and CMV. These pathogens may be transmitted prenatally through the transplacental route or perinatally through blood or vaginal secretions. Both viruses are present worldwide, and there are currently no specific vaccines available for either. Additionally, B19V re-emerged across Europe and Bulgaria in 2024, raising concerns about vertical transmission and neonatal morbidity [

16,

17].

2.1. B19V Infection

In 7 patients (54%), B19V infection was confirmed. The main reported clinical complications included fetal anemia, ascites, and hydrops fetalis. The virus was detected in all clinical specimens using PCR, while serological methods (ELISA for IgM and IgG) confirmed the infection in four cases. In four instances, follow-up clinical samples were collected from both the fetus in utero and the mother. Notably, positivity was detected at a very early cycle, with cycle threshold (Ct) values ranging from 13 to 19 in samples taken in utero. A mostly favorable outcome of the pregnancies was reported (see

Table 1).

During pregnancy, when B19V infection was diagnosed, an intrauterine blood transfusion was performed. This procedure successfully controlled congenital anemia and ensured the normal development of the fetus in the monitored women.

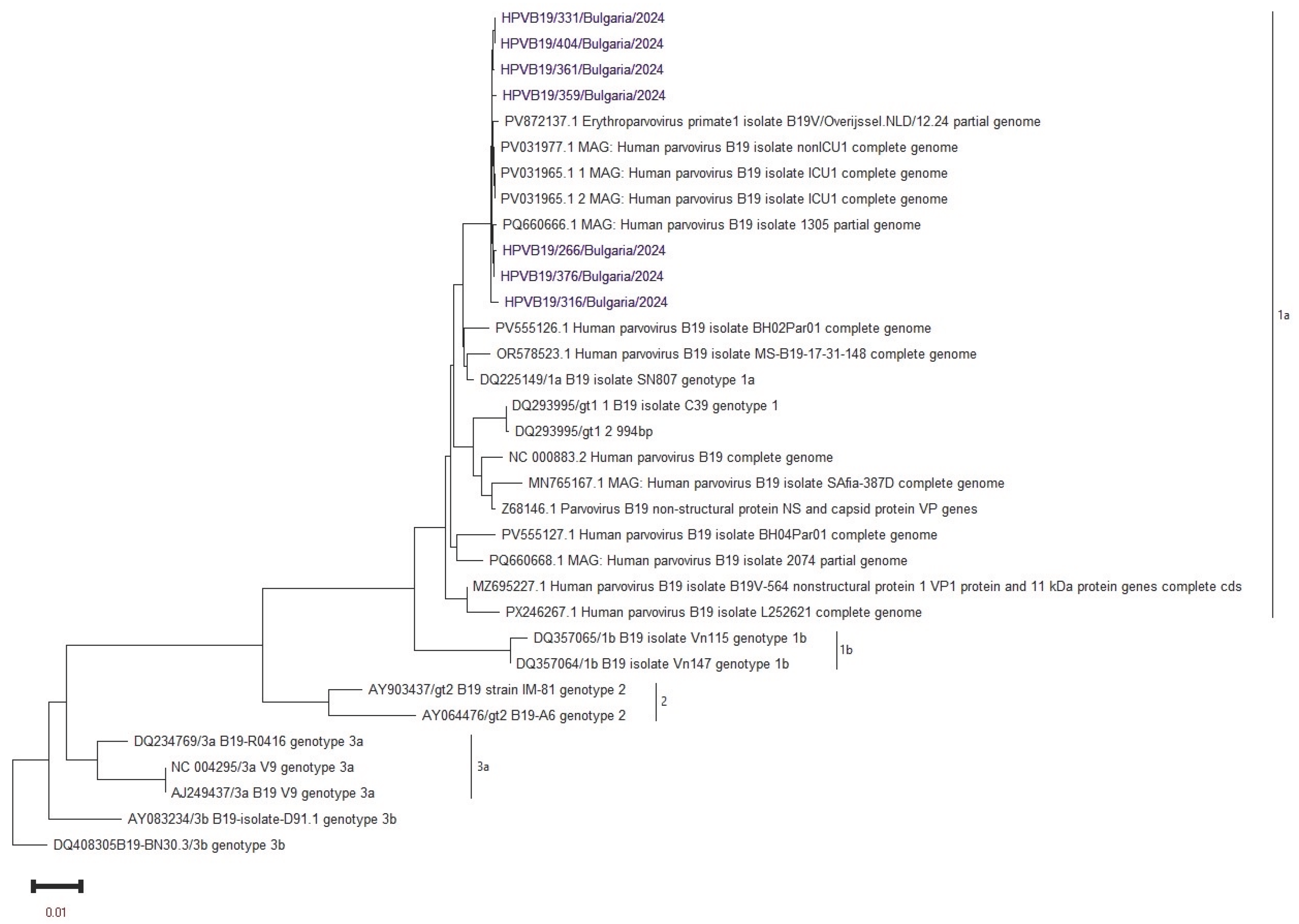

Whole-genome sequencing was performed in seven B19V-positive samples using the NGS method. All Bulgarian sequences were associated with genotype 1a by phylogenetic analysis. Therefore, genotype 1a of B19V was detected in clinical materials from both the mother and the fetus. The Bulgarian sequences showed the closest phylogenetic similarity to those from the Netherlands and Italy in 2024 (see

Figure 1).

2.2. CMV Infection

In the study, 4 out of the 13 pregnant women (31%) were confirmed to have CMV infection. The ages of these patients were 19, 28, 30, and 32. The most frequently reported complications included fetal growth restriction, as evidenced by changes in the brain, heart, and intestines. CMV infection was validated through real-time PCR in clinical samples, including amniotic fluid and fetal blood, for 3 of the patients. In the fourth patient, the infection was confirmed using serological methods (ELISA IgM/IgG), as she opted not to undergo amniocentesis. Unfortunately, one patient experienced stillbirth during the pregnancy (see

Table 2).

No sequencing was performed on the CMV-positive samples since all had a Ct value above 30.

In two of the thirteen monitored pregnant women, no B19V or CMV infection was detected, and the cause of the developed pathology is likely due to another factor.

3. Discussion

The present study underscores the clinical relevance of maternal molecular genetic screening for B19V and CMV as key determinants of congenital infection risk. B19V is not regarded as a teratogenic agent that affects embryogenesis during the first 8-10 weeks of gestation; therefore, it is not an indication for pregnancy termination. However, it is recognized as a human pathogen that can infect the placenta [

14]. Reports suggest that B19V infection during pregnancy occurs in about 1–5% of women, with the estimated rate of vertical transmission during maternal infection ranging from 17% to 33% [

18]. Data in the literature suggest that when a seronegative mother becomes infected, the fetus has a favorable outcome in 85% of cases [

19]. The effects of B19V infection on the fetus can vary widely, ranging from asymptomatic carrier status to spontaneous abortion, hydrops fetalis, congenital anemia, and intrauterine fetal death [

20]. Since early 2024, several European countries have reported an increase in B19V infections, particularly among pregnant women and children. This trend emphasizes the need for enhanced epidemiological surveillance, especially given the limitations of routine monitoring and the potential impacts of COVID-19-related immunity gaps in the post-pandemic period [

16,

17,

21]. In Bulgaria, where an overall increase in B19V incidence was noted during this study, thirteen women with pathological pregnancies were screened. Our results indicated that all confirmed B19V patients experienced favorable pregnancy outcomes following primary B19V infection. However, this was associated with a heightened risk of vertical transmission and reported conditions such as fetal anemia, hydrops, or ascites. All women with B19V in our study were diagnosed with anemia, which was managed during their pregnancies. Intravenous blood transfusions were performed to manage congenital anemia, leading to normal fetal development [

16]. Targeted serological testing during B19V outbreaks, combined with weekly Doppler surveillance of fetuses with confirmed maternal infection, remains the most evidence-based approach to preventing hydrops and optimizing the timing of intrauterine transfusions [

16,

22]. B19V was successfully isolated from maternal and intrauterine fetal blood samples, with serum PCR assays detecting high levels of viremia.

This study marks the first time that sequencing of B19V from clinical samples taken in utero has been conducted in the country. The comprehensive NGS analysis confirms the presence of the B19V 1a genotype in the examined cohort. Similar studies from 2024 indicate that genotype 1a is the dominant strain in Europe among various groups of infected individuals [

17,

23,

24]. Due to the uniform genetic affiliation of the B19V genetic sequences we isolated, we did not detect any evolutionary advantage in terms of genotype and clinical complications. Previous studies on the circulation of B19V in Bulgaria, particularly among patients with fever rash syndrome and those with hematological disorders, have confirmed that genotype 1a continues to persist within the country’s territory [

25,

26].

CMV can be transmitted vertically at any stage of pregnancy. The most severe effects on the fetus are associated with infections that occur during the first trimester, with the severity of the disease decreasing as gestational age increases. The highest risk of transmitting the infection to the fetus occurs during primary infection, and in 0.2% to 2.5% of seropositive pregnant women, premature birth may happen [

15]. Statistics indicate that 30% of newborns with severe congenital CMV infection do not survive [

14]. Among those who survive, more than half will ultimately develop neurological complications. Congenital CMV infection remains one of the most prevalent causes of non-genetic hearing loss and developmental delay, affecting 0.5–2% of all live births globally [

27,

28]. In our follow-up of women with CMV infection, one case of stillbirth was documented.

Molecular methods, such as quantitative PCR and NGS, have shown greater sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional serology. Detecting viral DNA in maternal plasma or amniotic fluid not only confirms active infection but also allows for the quantification of viral load. This viral load has been found to correlate with the severity of fetal disease [

29]. Therefore, integrating molecular diagnostics into prenatal screening programs is a significant advancement in evidence-based maternal-fetal risk assessment. These results reinforce the need for proactive maternal screening, especially in populations with high exposure risk or limited access to serological testing.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

Over twelve months, from April 2024 to March 2025, a total of 17 clinical samples from 13 women with pathological pregnancies were collected at the prenatal clinic of Dr. Shterev Hospital in Sofia. The patients’ ages ranged from 19 to 41 years, with a median age of 31±5.45 years; notably, only two women were younger than 30. Women who were tested were between 19 and 30 weeks pregnant. The clinical samples tested included amniotic fluid (n=4), umbilical cord serum (n=2), maternal serum (n=5), and fetal blood (n=5). These specimens were analyzed at the National Reference Laboratory for Measles, Mumps, and Rubella, which is part of the National Centre of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases in Sofia, Bulgaria, as well as at the Medical Complex “Dr. Shterev” in Sofia.

4.2. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Blood samples collected from the mothers and from baby-in-uterus were tested for the presence of anti-CMV/B19V immunoglobuline G (IgG) and M (IgM) antibodies using Euroimmun ELISA kits. Positive, negative, and cut-off controls were included in all runs, and results were and the results were interpreted qualitatively as positive, negative and borderline, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.3. DNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR for Viral Amplification

Viral DNA was extracted from all specimens using the PureLink Viral RNA/DNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisherr Scientific Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) by ViroReal Kit Parvovirus B19, Ingenetix GmbH, Vienna, Austria and CMV REAL-TIME PCR Detection Kit, “DNA-Technology Research & Production”, Moscow Region, Russia for CMV were used. Positive and negative controls were included in each real-time PCR run. Samples testing positive for B19V with a Ct value below 30 were selected for NGS.

The PCR machine used was the Real-time PCR System Gentier 96E, Tianlong Technology Co.

4.4. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

The targeted NGS method utilizing the Viral Surveillance Panel v2 Kit was employed to simultaneously isolate the genomes of viruses involved in mixed infections. This kit, developed by Illumina in San Diego, CA, USA, was used to characterize over 200 different viruses. NGS sequencing was conducted using the Illumina MiSeq system equipped with the 600-cycle v3 reagent kit.

Following sequencing, DNA libraries were analyzed for fragment size distribution with the QIAxcel Advanced capillary electrophoresis system (Qiagen Hilden, Germany). Library normalization was performed using the Qubit 4 Fluorometer along with the Invitrogen™ Quant-iT™ 1X High-Sensitivity (HS) Broad-Range (BR) dsDNA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific in Waltham, MA, USA).

We used the DRAGEN Microbial Enrichment Plus (DME+) software (version 1.1.1), available on the BaseSpace platform from Illumina (Cambridge, UK), for sequence assembly and FASTA file extension extraction. The PVB19 genetic sequences have been deposited in the GenBank sequence databases. BLAST searches were performed in multiple databases to retrieve references and closely related sequences. We used Geneious Prime (GraphPad Software, LLC, Boston, MA, USA) for alignment, while the MEGA11 (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis) software, developed in the United States at Pennsylvania State University, was used to construct the phylogenetic tree and its overall design.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

To analyze the collected data, the following statistical methods were employed:

- Calculation of relative share indicators (%) to evaluate the relationship between diagnostic approaches and clinical materials used.

- Standard deviation (SD).

5. Conclusions

The study emphasizes the importance of B19V and CMV during pregnancy. To optimize outcomes, it is crucial to have accurate and timely diagnoses, fetal surveillance appropriate to the gestational age, and multidisciplinary management. Implementing routine or targeted prenatal screening, which includes evaluating virological parameters, can facilitate the early detection and appropriate treatment of maternal infections. This approach can ultimately reduce the risk of fetal complications during outbreaks.

One limitation of our study is the small number of patients screened, as well as the missing information on pregnancy outcomes for five of the pregnant women confirmed to have B19V and CMV infections.

Supplementary Materials

No.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and M.HS.; methodology, R.S., L.V. and M.HS.; formal analysis, P.C., V.K., T.T., T.V., I.D. and P.G.; investigation, I.T. and S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K. and I.T.; visualization, I.T.; supervision, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the research project: “Contract BG16RFPR002-1.014-0017” “Center of Competence ImmunoPathogen”, procedure BG16RFPR002-1.014 “Sustainable development of Centers of Excellence and Centers of Competence, including specific infrastructures or their associations of the NRRI”, Programme “Research, Innovation and Digitalization for Smart Transformation 2021 – 2027”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the NATIONAL CENTRE OF INFECTIOUS AND PARASITIC DISEASES, Sofia, Bulgaria (ETHICS COMMITTEE IRB 00006384), protocol code 5/2025 on November 10, 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the project: “Contract BG16RFPR002-1.014-0017” “Center of Competence ImmunoPathogen”, procedure BG16RFPR002-1.014 “Sustainable development of Centers of Excellence and Centers of Competence, including specific infrastructures or their associations of the NRRI”, Programme “Research, Innovation and Digitalization for Smart Transformation 2021 – 2027”. The authors also would like to thank Prof. Neli Korsun, MD, PhD, NCIPD for valuable guidance and constructive suggestions during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

All co-authors reported no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| B19V |

Parvovirus B19 |

| CMV |

Cytomegalovirus |

| NGS |

Next-generation sequencing |

| RT-PCR |

Real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

References

- Madrid, L.; Varo, R.; Maculuve, S.; Nhampossa, T.; Muñoz-Almagro, C.; Calderón, E.J.; Esteva, C.; Carrilho, C.; Ismail, M.; Vieites, B.; Friaza, V.; Lozano-Dominguez, M.D.C.; Menéndez, C.; Bassat, Q. Congenital Cytomegalovirus, Parvovirus and Enterovirus Infection in Mozambican Newborns at Birth: A Cross-Sectional Survey. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams Waldorf, K.M.; McAdams, R.M. Influence of Infection During Pregnancy on Fetal Development. Reproduction 2013, 146, R151–R162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pizzo, J. Focus on Diagnosis: Congenital Infections (TORCH). Pediatr. Rev. 2011, 32, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, N.; Duchon, J.; Zachariah, P. TORCH Infections. Clin. Perinatol. 2015, 42, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Hashmi, A.H.; Manzoor, S. The Synergistic Tapestry: Unraveling the Interplay of Parvovirus B19 with Other Viruses. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 154, 107865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornoy, A.; Ergaz, Z. Parvovirus B19 Infection During Pregnancy and Risks to the Fetus. Birth Defects Res. 2017, 109, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kielaite, D.; Paliulyte, V. Parvovirus (B19) Infection During Pregnancy: Possible Effect on the Course of Pregnancy and Rare Fetal Outcomes. A Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 664. [Google Scholar]

- Bonvicini, F.; Puccetti, C.; Salfi, N.C.M.; Guerra, B.; Gallinella, G.; Rizzo, N.; Zerbini, M. Gestational and Fetal Outcomes in B19 Maternal Infection: A Problem of Diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 3514–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittmer, F.P.; Guimarães, C.d.M.; Peixoto, A.B.; Pontes, K.F.M.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Tonni, G.; Araujo Junior, E. Parvovirus B19 Infection and Pregnancy: Review of the Current Knowledge. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.O.; Hoopmann, M.; Geipel, A.; Sonek, J.; Enders, M. Prenatal Parvovirus B19 Infection. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 310, 2363–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syggelou, A.; Iacovidou, N.; Kloudas, S.; Christoni, Z.; Papaevangelou, V. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1205, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paschale, M.; Agrappi, C.; Manco, M.T.; Paganini, A.; Clerici, P. Incidence and Risk of Cytomegalovirus Infection During Pregnancy in an Urban Area of Northern Italy. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 2009, 206505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, G.; Daiminger, A.; Lindemann, L.; Knotek, F.; Bader, U.; Exler, S.; Enders, M. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Seroprevalence in Pregnant Women, Bone Marrow Donors and Adolescents in Germany, 1996–2010. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012, 201, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Gao, Z.; He, M.; et al. Infection Status of Human Parvovirus B19, Cytomegalovirus and Herpes Simplex Virus-1/2 in Women with First-Trimester Spontaneous Abortions in Chongqing, China. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornoy, A.; Diav-Citrin, O. Fetal Effects of Primary and Secondary Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy. Reprod. Toxicol. 2006, 21, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betta, P.; Leonardi, R.; Mattia, C.; Saporito, A.; Gentile, S.; Trovato, L.; Palermo, C.I.; Scalia, G. Congenital Parvovirus B19 During the 2024 European Resurgence: A Prospective Single-Centre Cohort Study. Pathogens 2025, 14, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beligni, G.; Alessandri, G.; Cusi, M.G. Genotypic Characterization of Human Parvovirus B19 Circulating in the 2024 Outbreak in Tuscany, Italy. Pathogens 2025, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malutan, A.M.; Ormindean, C.M.; Diculescu, D.; Ciortea, R.; Nicula, R.; Pop, D.; Bucuri, C.; Maria, R.; Nati, I.; Mihu, D. Parvovirus B19 in Pregnancy—Do We Screen for Fifth Disease or Not? Life 2024, 14, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.; Mundle, W.; Boucoiran, I. ; MATERNAL FETAL MEDICINE COMMITTEE. Parvovirus B19 Infection in Pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2014, 36, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadatou, V.; Tologkos, S.; Deftereou, T.; Alexiadis, T.; Pagonopoulou, O.; Alexiadi, C.A.; Bakatselou, P.; Oglou, S.T.C.; Tripsianis, G.; Mitrakas, A.; Lambropoulou, M. Viral-Induced Inflammation Can Lead to Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Folia Med. 2023, 65, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Risks Posed by Reported Increased Circulation of Human Parvovirus B19 in the EU/EEA. ECDC Report 2024. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications‐data/risks‐posed‐reported‐increased‐circulation‐humanparvovirus‐

b19‐eueea.

- Gigi, C.E.; Anumba, D.O.C. Parvovirus B19 Infection in Pregnancy—A Review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 264, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichicchi, F.; Guglietta, N.; Rocha Alves, A.D.; Fasano, E.; Manaresi, E.; Bua, G.; Gallinella, G. Next Generation Sequencing for the Analysis of Parvovirus B19 Genomic Diversity. Viruses 2023, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.D.R.; Amado, L.A.A. A Retrospective Analysis of Clinical and Epidemiological Aspects of Parvovirus B19 in Brazil: A Hidden and Neglected Virus Among Immunocompetent and Immunocompromised Individuals. Viruses 2025, 17, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, S.; Mihneva, Z.; Toshev, A.; Kovaleva, V.; Andonova, L.; Muller, C.; Hübschen, J. Insights into Epidemiology of Human Parvovirus B19 and Detection of an Unusual Genotype 2 Variant, Bulgaria, 2004–2013. Euro Surveill. 2016, 21, 30116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumova, S.; Andonova, I.; Stefanova, R.; Miteva, P.; Nenkova, G.; Hübschen, J.M. Primate Erythroparvovirus 1 Infection in Patients with Hematological Disorders. Pathogens 2022, 11, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlinson, W.D.; Boppana, S.B.; Fowler, K.B.; Kimberlin, D.W.; Lazzarotto, T.; Alain, S.; Daly, K.; Doutré, S.; Gibson, L.; Giles, M.L.; Greenlee, J.; Hamilton, S.T.; Harrison, G.J.; Hui, L.; Jones, C.A.; Palasanthiran, P.; Schleiss, M.R.; Shand, A.W.; van Zuylen, W.J. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy and the Neonate: Consensus Recommendations for Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e177–e188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boppana, S.B.; Ross, S.A.; Fowler, K.B. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Clinical Outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57 (Suppl. 4), S178–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilad, N.; Agrawal, S.; Philippopoulos, E.; Murphy, K.E.; Shinar, S. Is a Higher Amniotic Fluid Viral Load Associated with a Greater Risk of Fetal Injury in Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).