Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

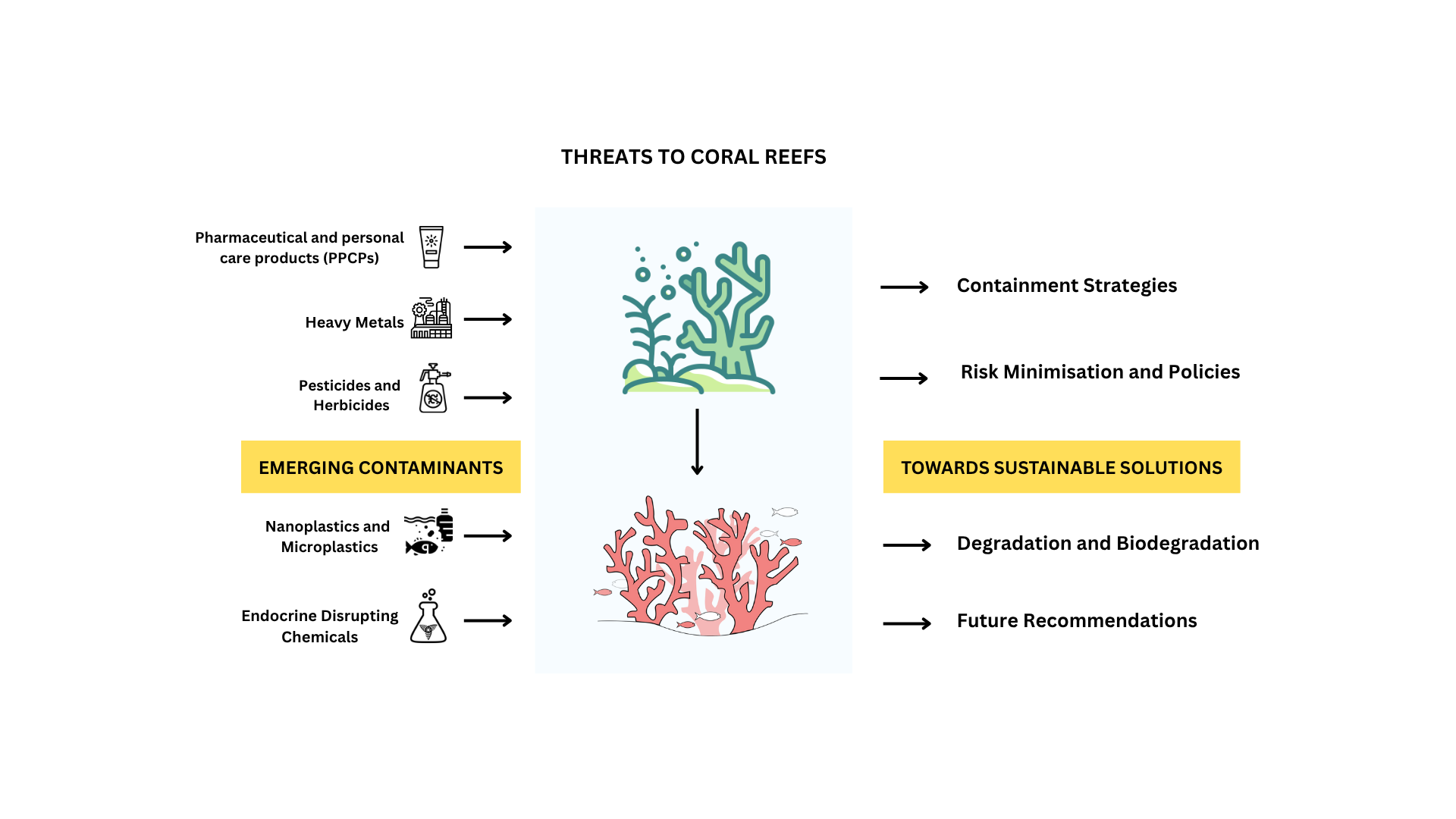

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of Coral Reefs

1.2. The Decimation of Corals

2. The Great Barrier Reef: Confronting a Complex Threat Environment

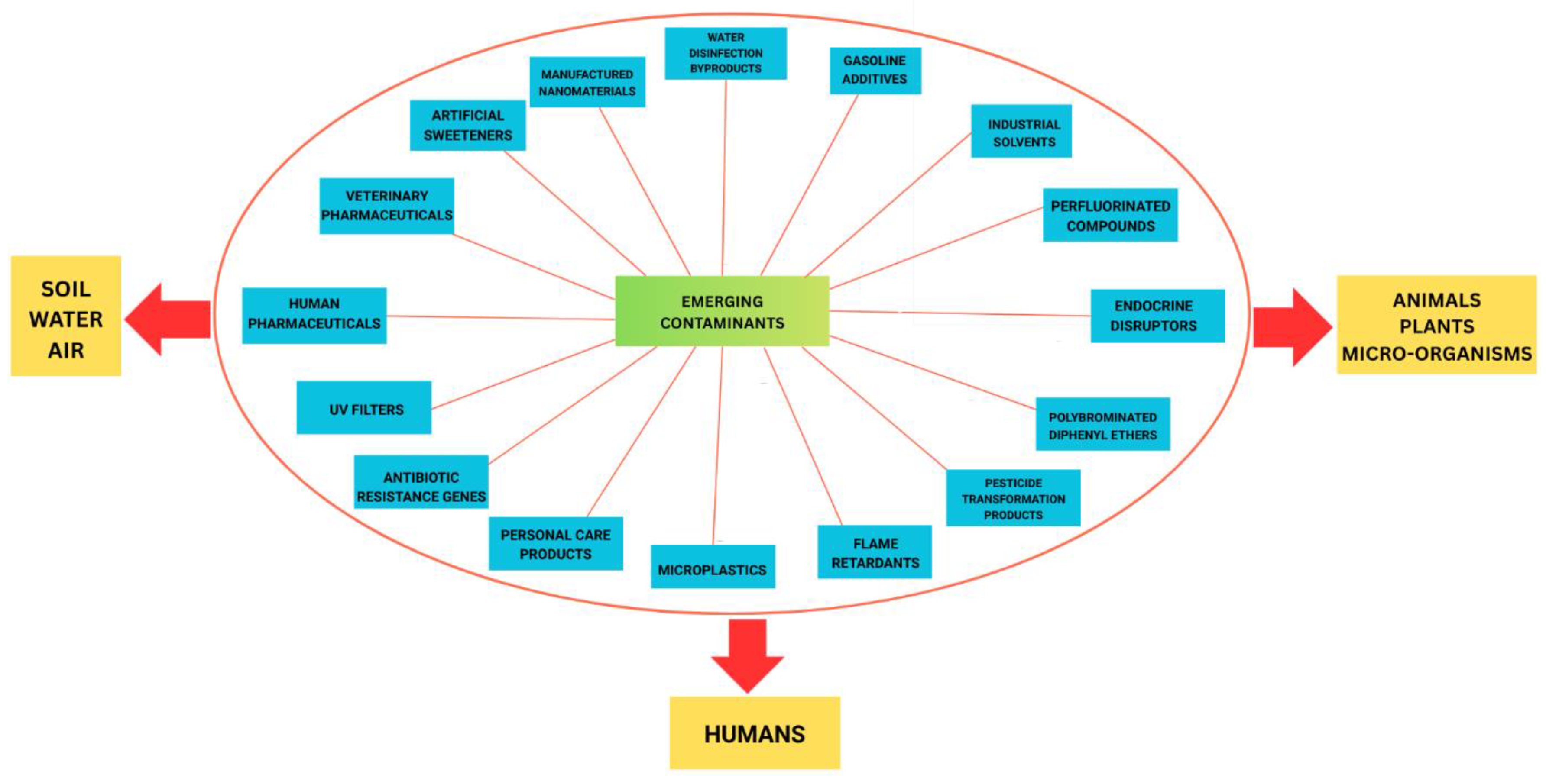

2.1. Current Landscape of Emerging Contaminants in Coral Reef Ecosystems

2.1.1. Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs)

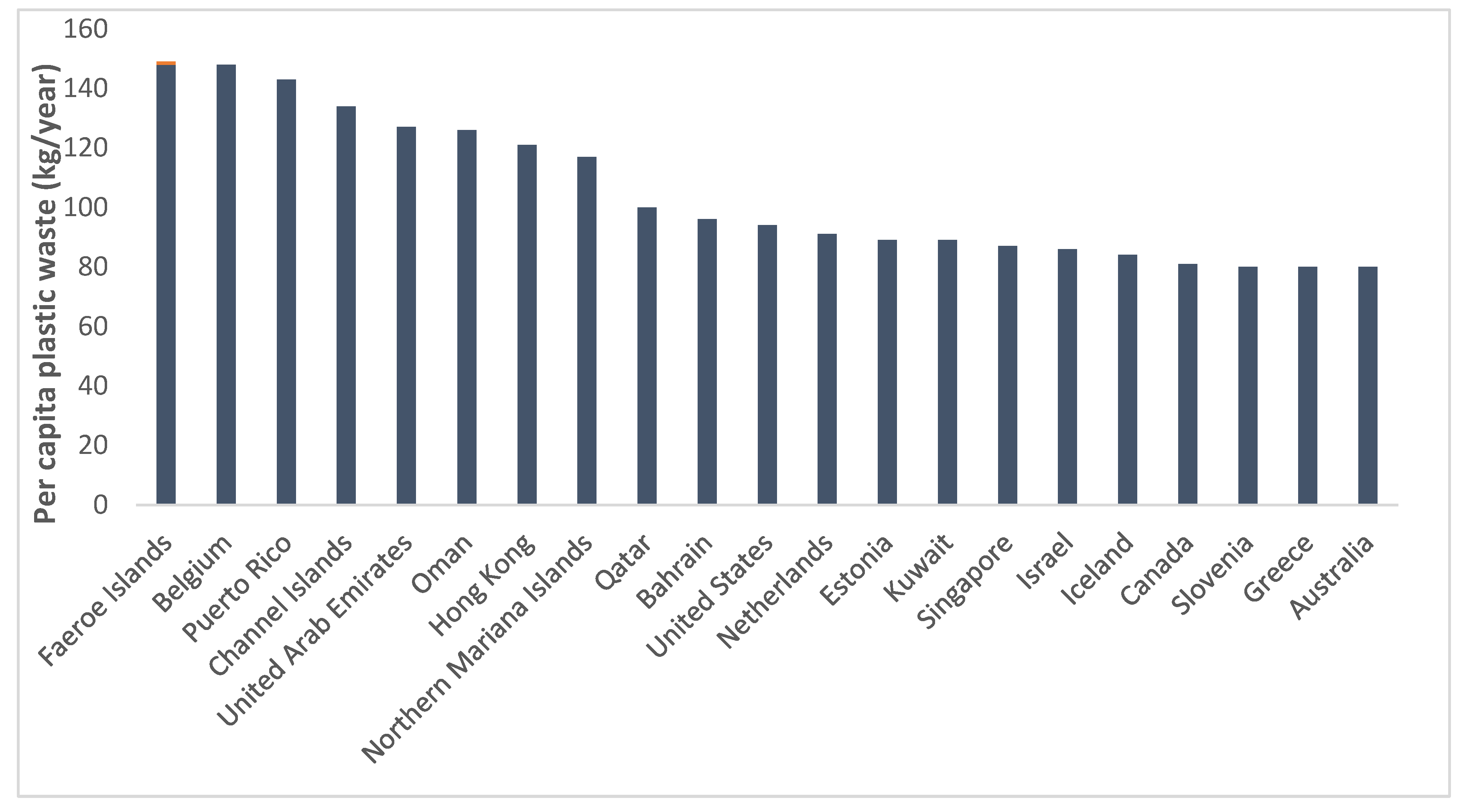

2.1.2. Nanoplastics and Microplastics

2.1.3. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

2.2. Ecological Ramifications of Contaminant Accumulation in Reef-Sensitive Zones

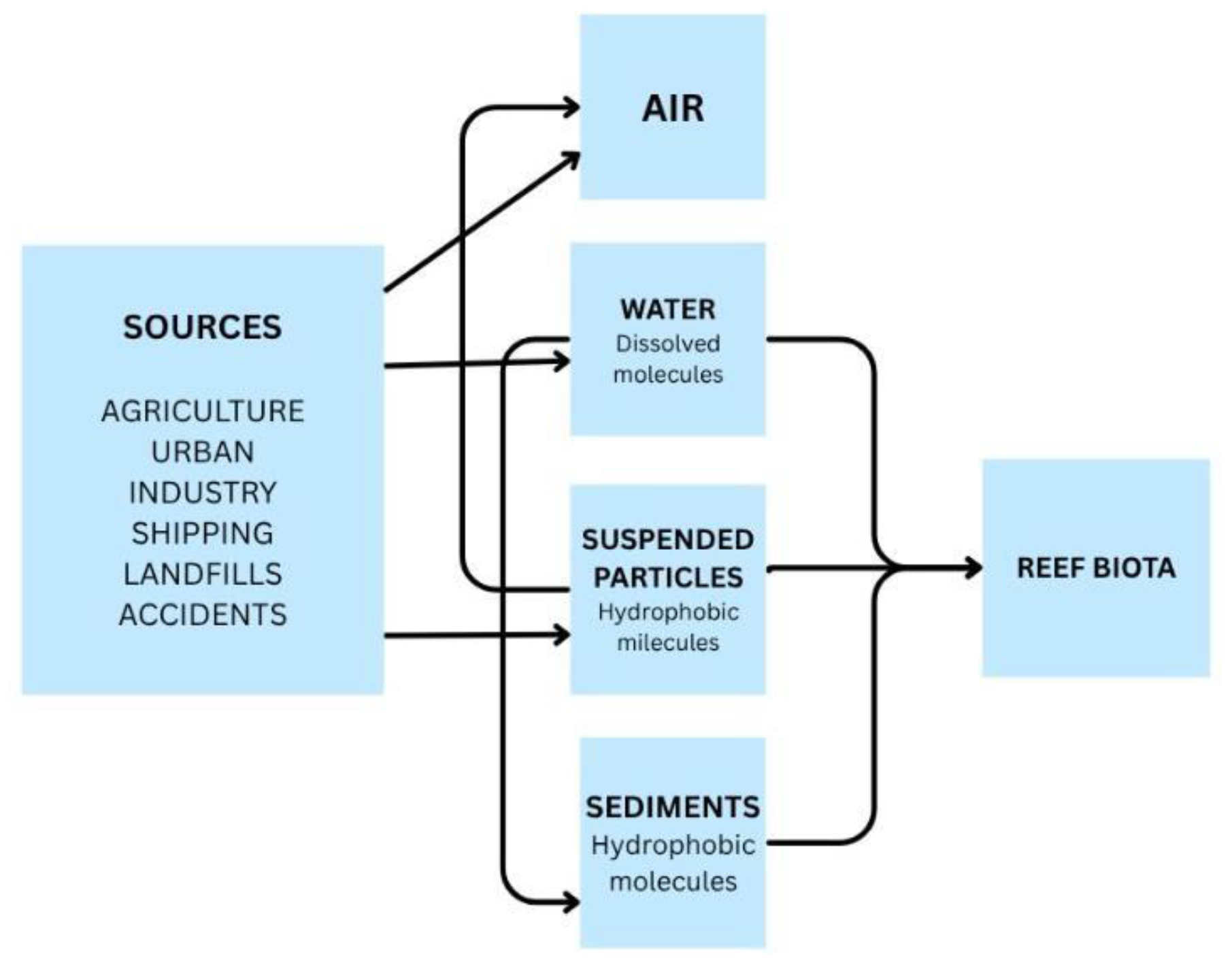

3. Mechanisms of Pollutant Transport: From Catchment to Coast

3.1. The Role of Water

4. Contaminant Toxicity

5. Risk Minimization and Policies

6. Containment Strategies

7. Degradation and Biodegradation

8. Recommendations and Future Directions

9. Concluding Remarks

References

- Abdel Rahman, R. O., El-Kamash, A. M., & Hung, Y. T. (2023). Permeable Concrete Barriers to Control Water Pollution: A Review. Water 2023, Vol. 15, Page 3867, 15(21), 3867. [CrossRef]

- Adenaya, A., Quintero, R. R., Brinkhoff, T., Lara-Martín, P. A., Wurl, O., & Ribas-Ribas, M. (2024). Vertical distribution and risk assessment of pharmaceuticals and other micropollutants in southern North Sea coastal waters. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 200, 116099. [CrossRef]

- Agawin, N. S. R., García-Márquez, M. G., Espada, D. R., Freemantle, L., Pintado Herrera, M. G., & Tovar-Sánchez, A. (2024). Distribution and accumulation of UV filters (UVFs) and conservation status of Posidonia oceanica seagrass meadows in a prominent Mediterranean coastal tourist hub. Science of The Total Environment, 948, 174784. [CrossRef]

- Anand, U., Adelodun, B., Cabreros, C., Kumar, P., Suresh, S., Dey, A., Ballesteros, F., & Bontempi, E. (2022). Occurrence, transformation, bioaccumulation, risk and analysis of pharmaceutical and personal care products from wastewater: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2022 20:6, 20(6), 3883–3904. [CrossRef]

- Andrello, M., Darling, E. S., Wenger, A., Suárez-Castro, A. F., Gelfand, S., & Ahmadia, G. N. (2022). A global map of human pressures on tropical coral reefs. Conservation Letters, 15(1), e12858. [CrossRef]

- Atugoda, T., Vithanage, M., Wijesekara, H., Bolan, N., Sarmah, A. K., Bank, M. S., You, S., & Ok, Y. S. (2021). Interactions between microplastics, pharmaceuticals and personal care products: Implications for vector transport. Environment International, 149, 106367. [CrossRef]

- Australia Goverment. (2019). Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, 374. https://elibrary.gbrmpa.gov.au/jspui/handle/11017/3474.

- Bainbridge, Z. T., Olley, J. M., Lewis, S. E., Stevens, T., & Smithers, S. G. (2024). Tracing sources of inorganic suspended particulate matter in the Great Barrier Reef lagoon, Australia. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Bakir, A., Doran, D., Silburn, B., Russell, J., Archer-Rand, S., Barry, J., Maes, T., Limpenny, C., Mason, C., Barber, J., & Nicolaus, E. E. M. (2023). A spatial and temporal assessment of microplastics in seafloor sediments: A case study for the UK. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 1093815. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, I., Lone, F. A., Bhat, R. A., Mir, S. A., Dar, Z. A., & Dar, S. A. (2020). Concerns and threats of contamination on aquatic ecosystems. Bioremediation and Biotechnology: Sustainable Approaches to Pollution Degradation, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M., Adeel, M., Rasheed, T., Zhao, Y., & Iqbal, H. M. N. (2019). Emerging contaminants of high concern and their enzyme-assisted biodegradation – A review. Environment International, 124, 336–353. [CrossRef]

- Bratkovics, S., Wirth, E., Sapozhnikova, Y., Pennington, P., & Sanger, D. (2015). Baseline monitoring of organic sunscreen compounds along South Carolina’s coastal marine environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 101(1), 370–377. [CrossRef]

- Brodie, J., Schroeder, T., Rohde, K., Faithful, J., Masters, B., Dekker, A., Brando, V., & Maughan, M. (2010). Dispersal of suspended sediments and nutrients in the Great Barrier Reef lagoon during river-discharge events: conclusions from satellite remote sensing and concurrent flood-plume sampling. Marine and Freshwater Research, 61(6), 651–664. [CrossRef]

- Burke, L., Reytar, K., Spalding, M., & Perry, A. (2011). Reefs at risk revisited. 2. https://bvearmb.do/handle/123456789/1787.

- Burkepile, D. E., & Hay, M. E. (2010). Impact of Herbivore Identity on Algal Succession and Coral Growth on a Caribbean Reef. PLOS ONE, 5(1), e8963. [CrossRef]

- Caneva, L., Bonelli, M., Papaluca-Amati, M., & Vidal, J. M. (2014). Critical review on the Environmental Risk Assessment of medicinal products for human use in the centralised procedure. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 68(3), 312–316. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S., & Walsh, K. B. (2024). Microplastics in water: Occurrence, fate and removal. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 264, 104360. [CrossRef]

- Chapron, L., Peru, E., Engler, A., Ghiglione, J. F., Meistertzheim, A. L., Pruski, A. M., Purser, A., Vétion, G., Galand, P. E., & Lartaud, F. (2018). Macro- and microplastics affect cold-water corals growth, feeding and behaviour. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Cojoc, L., de Castro-Català, N., de Guzmán, I., González, J., Arroita, M., Besolí-Mestres, N., Cadena, I., Freixa, A., Gutiérrez, O., Larrañaga, A., Muñoz, I., Elosegi, A., Petrovic, M., & Sabater, S. (2024). Pollutants in urban runoff: Scientific evidence on toxicity and impacts on freshwater ecosystems. Chemosphere, 369, 143806. [CrossRef]

- Cossu, L. O., De Aquino, S. F., Mota Filho, C. R., Smith, C. J., & Vignola, M. (2024). Review on Pesticide Contamination and Drinking Water Treatment in Brazil: The Need for Improved Treatment Methods. ACS ES and T Water, 4(9), 3629–3644. [CrossRef]

- Dang, J., Pei, W., Hu, F., Yu, Z., Zhao, S., Hu, J., Liu, J., Zhang, D., Jing, Z., & Lei, X. (2023). Photocatalytic Degradation and Toxicity Analysis of Sulfamethoxazole using TiO2/BC. Toxics 2023, Vol. 11, Page 818, 11(10), 818. [CrossRef]

- DETSI, Q. (n.d.). From mermaid wineglasses to sea grapes – meet the Great Barrier Reef plants | Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation (DETSI), Queensland. Retrieved August 26, 2025, from https://www.detsi.qld.gov.au/our-department/news-media/down-to-earth/great-barrier-reef-plants?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Dimitrakopoulou, M. E., Karvounis, M., Marinos, G., Theodorakopoulou, Z., Aloizou, E., Petsangourakis, G., Papakonstantinou, M., & Stoitsis, G. (2024). Comprehensive analysis of PFAS presence from environment to plate. Npj Science of Food, 8(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Downs, C. A., Kramarsky-Winter, E., Segal, R., Fauth, J., Knutson, S., Bronstein, O., Ciner, F. R., Jeger, R., Lichtenfeld, Y., Woodley, C. M., Pennington, P., Cadenas, K., Kushmaro, A., & Loya, Y. (2015). Toxicopathological Effects of the Sunscreen UV Filter, Oxybenzone (Benzophenone-3), on Coral Planulae and Cultured Primary Cells and Its Environmental Contamination in Hawaii and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2015 70:2, 70(2), 265–288. [CrossRef]

- Du, H., & Wang, J. (2021). Characterization and environmental impacts of microplastics. Gondwana Research, 98, 63–75. [CrossRef]

- Durães, N., Novo, L. A. B., Candeias, C., & Da Silva, E. F. (2018). Distribution, Transport and Fate of Pollutants. Soil Pollution: From Monitoring to Remediation, 29–57. [CrossRef]

- Eapen, J. V., Thomas, S., Antony, S., George, P., & Antony, J. (2024). A review of the effects of pharmaceutical pollutants on humans and aquatic ecosystem. Open Exploration 2019 2:5, 2(5), 484–507. [CrossRef]

- Eddy, T. D., Lam, V. W. Y., Reygondeau, G., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Greer, K., Palomares, M. L. D., Bruno, J. F., Ota, Y., & Cheung, W. W. L. (2021). Global decline in capacity of coral reefs to provide ecosystem services. One Earth, 4(9), 1278–1285. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J. I., Jamil, T., Anlauf, H., Coker, D. J., Curdia, J., Hewitt, J., Jones, B. H., Krokos, G., Kürten, B., Hariprasad, D., Roth, F., Carvalho, S., & Hoteit, I. (2019). Multiple stressor effects on coral reef ecosystems. Global Change Biology, 25(12), 4131–4146. [CrossRef]

- Emmett Duffy, J., Godwin, C. M., & Cardinale, B. J. (2017). Biodiversity effects in the wild are common and as strong as key drivers of productivity. Nature, 549(7671), 261–264. [CrossRef]

- Erto, A., Bortone, I., Di Nardo, A., Di Natale, M., & Musmarra, D. (2014). Permeable Adsorptive Barrier (PAB) for the remediation of groundwater simultaneously contaminated by some chlorinated organic compounds. Journal of Environmental Management, 140, 111–119. [CrossRef]

- Escher, B. I., Stapleton, H. M., & Schymanski, E. L. (2020). Tracking complex mixtures of chemicals in our changing environment. Science, 367(6476), 388–392. [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. (2024). Directive (EU) 2024/3019 on the treatment of urban wastewater (recast). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/3019/oj/eng.

- Fabricius, K., Brown, A., Songcuan, A., Collier, C., Uthicke, S., & Robson, B. (2024). 2022 Scientific Consensus Statement Question 2.2 What are the current and predicted impacts of climate change on Great Barrier Reef ecosystems (including spatial and temporal distribution impacts). [CrossRef]

- Fel, J. P., Lacherez, C., Bensetra, A., Mezzache, S., Béraud, E., Léonard, M., Allemand, D., & Ferrier-Pagès, C. (2019). Photochemical response of the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata to some sunscreen ingredients. Coral Reefs, 38(1), 109–122. [CrossRef]

- Fenni, F., Sunyer-Caldú, A., Mansour, H. Ben, & Diaz-Cruz, M. S. (2025). Occurrence and risks of pharmaceuticals in Mahdia’s coastline (Tunisia): distribution, antibiotic resistance, and ecotoxicological impact. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 32(30), 18419–18433. [CrossRef]

- Fine, M., Cinar, M., Voolstra, C. R., Safa, A., Rinkevich, B., Laffoley, D., Hilmi, N., & Allemand, D. (2019). Coral reefs of the Red Sea — Challenges and potential solutions. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 25, 100498. [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, D. (2024). Environmental risk and market approval for human pharmaceuticals. Monash Bioethics Review, 42(Suppl 1), 105–124. [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F., Jouet, M., Goulais, M., Tetaura, N.-L., Lo-Yat, A., Goulais, M., Tetaura, N.-L., & Lo-Yat, A. (2025). Assessment of Sediment Quality and Vulnerability of Tropical Marine Species in the Society Islands, French Polynesia. Under Review at Coral Reefs. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Yuan, C., Cheng, S., Sun, J., Ouyang, S., Xue, W., Zhang, W., Zhou, L., Wang, J., & Sun, S. (2025). Potential risks and hazards posed by the pressure of pharmaceuticals and personal care products on water treatment plants. Environmental Pollution, 378, 126344. [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, A. J., Espín, S., Gómez-Ramírez, P., Sánchez-Virosta, P., & Navas, I. (2021). Water Quality and Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs). Chemometrics and Cheminformatics in Aquatic Toxicology, 3–21. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J., McField, M., & Wells, S. (1998). Coral reef management in Belize: an approach through integrated coastal zone management. Ocean & Coastal Management, 39(3), 229–244. [CrossRef]

- Gildemeister, D., Moermond, C. T. A., Berg, C., Bergstrom, U., Bielská, L., Evandri, M. G., Franceschin, M., Kolar, B., Montforts, M. H. M. M., & Vaculik, C. (2023). Improving the regulatory environmental risk assessment of human pharmaceuticals: Required changes in the new legislation. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 142, 105437. [CrossRef]

- Ginebreda, A., Muñoz, I., de Alda, M. L., Brix, R., López-Doval, J., & Barceló, D. (2010). Environmental risk assessment of pharmaceuticals in rivers: Relationships between hazard indexes and aquatic macroinvertebrate diversity indexes in the Llobregat River (NE Spain). Environment International, 36(2), 153–162. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J. A., Histed, A. R., Nowak, E., Lange, D., Craig, S. E., Parker, C. G., Kaur, A., Bhuvanagiri, S., Kroll, K. J., Martyniuk, C. J., Denslow, N. D., Rosenfeld, C. S., & Rhodes, J. S. (2021). Impact of bisphenol-A and synthetic estradiol on brain, behavior, gonads and sex hormones in a sexually labile coral reef fish. Hormones and Behavior, 136, 105043. [CrossRef]

- Good, A. M., & Bahr, K. D. (2021). The coral conservation crisis: interacting local and global stressors reduce reef resiliency and create challenges for conservation solutions. SN Applied Sciences, 3(3), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Great Barrier Reef Foundation. (n.d.). The Great Barrier Reef explained: size, species, threats and why it matters. Retrieved August 26, 2025, from https://www.barrierreef.org/news/news/the-great-barrier-reef-explained.

- Habimana, E., & Sauvé, S. (2025). A review of properties, occurrence, fate, and transportation mechanisms of contaminants of emerging concern in sewage sludge, biosolids, and soils: recent advances and future trends. Frontiers in Environmental Chemistry, 6, 1547596. [CrossRef]

- Häder, D. P., Banaszak, A. T., Villafañe, V. E., Narvarte, M. A., González, R. A., & Helbling, E. W. (2020). Anthropogenic pollution of aquatic ecosystems: Emerging problems with global implications. Science of The Total Environment, 713, 136586. [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A., Shafiq, A., Chen, S. Q., & Nazar, M. (2023). A Comprehensive Review on Adsorption, Photocatalytic and Chemical Degradation of Dyes and Nitro-Compounds over Different Kinds of Porous and Composite Materials. Molecules 2023, Vol. 28, Page 1081, 28(3), 1081. [CrossRef]

- Han, Q. F., Song, C., Sun, X., Zhao, S., & Wang, S. G. (2021). Spatiotemporal distribution, source apportionment and combined pollution of antibiotics in natural waters adjacent to mariculture areas in the Laizhou Bay, Bohai Sea. Chemosphere, 279, 130381. [CrossRef]

- Hankins, C., Moso, E., & Lasseigne, D. (2021). Microplastics impair growth in two atlantic scleractinian coral species, Pseudodiploria clivosa and Acropora cervicornis. Environmental Pollution, 275, 116649. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S., Barnett, C., Short, S., Uluseker, C., Silva, P. V., Pavlaki, M. D., Roberts, S., Vieira, M., Lofts, S., Loureiro, S., & Spurgeon, D. J. (2025). Continuous improvement towards environmental protection for pharmaceuticals: advancing a strategy for Europe. Environmental Sciences Europe, 37(1), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Haupt, R., Heinemann, C., Hayer, J. J., Schmid, S. M., Guse, M., Bleeser, R., & Steinhoff-Wagner, J. (2021). Critical discussion of the current environmental risk assessment (ERA) of veterinary medicinal products (VMPs) in the European Union, considering changes in animal husbandry. Environmental Sciences Europe, 33(1), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- He, T., Tsui, M. M. P., Tan, C. J., Ma, C. Y., Yiu, S. K. F., Wang, L. H., Chen, T. H., Fan, T. Y., Lam, P. K. S., & Murphy, M. B. (2019). Toxicological effects of two organic ultraviolet filters and a related commercial sunscreen product in adult corals. Environmental Pollution, 245, 462–471. [CrossRef]

- Helwig, K., Niemi, L., Stenuick, J. Y., Alejandre, J. C., Pfleger, S., Roberts, J., Harrower, J., Nafo, I., & Pahl, O. (2024). Broadening the Perspective on Reducing Pharmaceutical Residues in the Environment. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 43(3), 653–663. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J. P. A., Frisch, A. J., Newman, S. J., & Wakefield, C. B. (2015). Selective Impact of Disease on Coral Communities: Outbreak of White Syndrome Causes Significant Total Mortality of Acropora Plate Corals. PLOS ONE, 10(7), e0132528. [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Pendleton, L., & Kaup, A. (2019). People and the changing nature of coral reefs. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 30, 100699. [CrossRef]

- Hook, S. E., Smith, R. A., Waltham, N., & Warne, M. S. J. (2024). Pesticides in the Great Barrier Reef catchment area: Plausible risks to fish populations. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 20(5), 1256–1279. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T. P., Kerry, J. T., Álvarez-Noriega, M., Álvarez-Romero, J. G., Anderson, K. D., Baird, A. H., Babcock, R. C., Beger, M., Bellwood, D. R., Berkelmans, R., Bridge, T. C., Butler, I. R., Byrne, M., Cantin, N. E., Comeau, S., Connolly, S. R., Cumming, G. S., Dalton, S. J., Diaz-Pulido, G., … Wilson, S. K. (2017). Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature, 543(7645), 373–377. [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, H., & van Hullebusch, E. D. (2020). Performance Comparison of Different Constructed Wetlands Designs for the Removal of Personal Care Products. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, Vol. 17, Page 3091, 17(9), 3091. [CrossRef]

- Intisar, A., Ramzan, A., Hafeez, S., Hussain, N., Irfan, M., Shakeel, N., Gill, K. A., Iqbal, A., Janczarek, M., & Jesionowski, T. (2023). Adsorptive and photocatalytic degradation potential of porous polymeric materials for removal of pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and dyes-based emerging contaminants from water. Chemosphere, 336, 139203. [CrossRef]

- Irwan, Rani, C., Jompa, J., & Kadir, N. N. (2024). Coral reef condition at different trophic status in marginal waters of Bone Bay, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1410(1), 012006. [CrossRef]

- John Morrison, R., & Aalbersberg, W. G. L. (2022). Anthropogenic Environmental Impacts on Coral Reefs in the Western and South-Western Pacific Ocean. Coral Reefs of the World, 14, 7–24. [CrossRef]

- Kamani, H., Ashrafi, S. D., Lima, E. C., Panahi, A. H., Nezhad, M. G., & Abdipour, H. (2023). Synthesis of N-doped TiO2 nanoparticle and its application for disinfection of a treatment plant effluent from hospital wastewater. Desalination and Water Treatment, 289, 155–162. [CrossRef]

- Kanakaraju, D., Natashya, P. P., Lim, Y. C., & Tan, I. A. W. (2025). Functionalized TiO2-waste-derived photocatalytic materials for emerging pollutant degradation: synthesis and optimization. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 197(9), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Kar, S., Sanderson, H., Roy, K., Benfenati, E., & Leszczynski, J. (2020). Ecotoxicological assessment of pharmaceuticals and personal care products using predictive toxicology approaches. Green Chemistry, 22(5), 1458–1516. [CrossRef]

- Krakowiak, R., Musial, J., Bakun, P., Spychała, M., Czarczynska-Goslinska, B., Mlynarczyk, D. T., Koczorowski, T., Sobotta, L., Stanisz, B., & Goslinski, T. (2021). Titanium Dioxide-Based Photocatalysts for Degradation of Emerging Contaminants including Pharmaceutical Pollutants. Applied Sciences 2021, Vol. 11, Page 8674, 11(18), 8674. [CrossRef]

- Kroon, F. J., Berry, K. L. E., Brinkman, D. L., Kookana, R., Leusch, F. D. L., Melvin, S. D., Neale, P. A., Negri, A. P., Puotinen, M., Tsang, J. J., van de Merwe, J. P., & Williams, M. (2020). Sources, presence and potential effects of contaminants of emerging concern in the marine environments of the Great Barrier Reef and Torres Strait, Australia. Science of The Total Environment, 719, 135140. [CrossRef]

- Kuempel, C. D., Thomas, J., Wenger, A. S., Jupiter, S. D., Suárez-Castro, A. F., Nasim, N., Klein, C. J., & Hoegh-Guldberg, O. (2024). A spatial framework for improved sanitation to support coral reef conservation. Environmental Pollution, 342, 123003. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Qureshi, M., Vishwakarma, D. K., Al-Ansari, N., Kuriqi, A., Elbeltagi, A., & Saraswat, A. (2022). A review on emerging water contaminants and the application of sustainable removal technologies. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 6, 100219. [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J. B., Willis, B. L., Fiorenza, E. A., Couch, C. S., Howard, R., Rader, D. N., True, J. D., Kelly, L. A., Ahmad, A., Jompa, J., & Harvell, C. D. (2018). Plastic waste associated with disease on coral reefs. Science, 359(6374), 460–462. [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y., Xiao, H., Li, Z., & Wang, J. (2020). Tetracyclines, sulfonamides and quinolones and their corresponding resistance genes in coastal areas of Beibu Gulf, China. Science of The Total Environment, 714, 136899. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, S., Gao, T., Gao, Z., Lai, C. W., Xiang, P., & Yang, F. (2025). Global Distribution, Ecotoxicity, and Treatment Technologies of Emerging Contaminants in Aquatic Environments: A Recent Five-Year Review. Toxics 2025, Vol. 13, Page 616, 13(8), 616. [CrossRef]

- Liang, H., Pan, C. G., Peng, F. J., Hu, J. J., Zhu, R. G., Zhou, C. Y., Liu, Z. Z., & Yu, K. (2024). Integrative transcriptomic analysis reveals a broad range of toxic effects of triclosan on coral Porites lutea. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 480, 136033. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X., Yu, S., Meng, B., Wang, X., Yang, C., Shi, C., & Ding, J. (2025). Advanced TiO₂-Based Photoelectrocatalysis: Material Modifications, Charge Dynamics, and Environmental–Energy Applications. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Li, X., Lou, S., Xu, Q., Jin, Y., Dorzhievna, R. L., Elena, N., Nikolavich, M. A., Tavares, A. J., & Viktorovna, F. I. (2023). Occurrence of sulfonamides and tetracyclines in the coastal areas of the Yangtze River (China) Estuary. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 30(56), 118567–118587. [CrossRef]

- Manyepa, P., Gani, K. M., Seyam, M., Banoo, I., Genthe, B., Kumari, S., & Bux, F. (2024). Removal and risk assessment of emerging contaminants and heavy metals in a wastewater reuse process producing drinkable water for human consumption. Chemosphere, 361, 142396. [CrossRef]

- Margot, J., Kienle, C., Magnet, A., Weil, M., Rossi, L., de Alencastro, L. F., Abegglen, C., Thonney, D., Chèvre, N., Schärer, M., & Barry, D. A. (2013). Treatment of micropollutants in municipal wastewater: Ozone or powdered activated carbon? Science of The Total Environment, 461–462, 480–498. [CrossRef]

- Marlatt, V. L., Bayen, S., Castaneda-Cortès, D., Delbès, G., Grigorova, P., Langlois, V. S., Martyniuk, C. J., Metcalfe, C. D., Parent, L., Rwigemera, A., Thomson, P., & Van Der Kraak, G. (2022). Impacts of endocrine disrupting chemicals on reproduction in wildlife and humans. Environmental Research, 208, 112584. [CrossRef]

- Masud, A., Chavez Soria, N. G., Aga, D. S., & Aich, N. (2020). Adsorption and advanced oxidation of diverse pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) from water using highly efficient rGO–nZVI nanohybrids. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology, 6(8), 2223–2238. [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Pinto, M., Ledet, J., Crowe, T. P., & Johnston, E. L. (2020). Sublethal effects of contaminants on marine habitat-forming species: a review and meta-analysis. Biological Reviews, 95(6), 1554–1573. [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, M. A., Khan, N. A., Ahmed, S., Khan, A. H., Hussain, A., Rahisuddin, Changani, F., Yousefi, M., Ahmadi, S., & Vambol, V. (2020). Chlorination disinfection by-products in municipal drinking water – A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 273, 123159. [CrossRef]

- Maznan, N. A., Samshuri, M. A., & Jaafar, S. N. (2024). EFFECT OF SEA SURFACE TEMPERATURE ON CATALASE AND GLUTATHIONE S-TRANSFERASE ACTIVITIES IN SCLERACTINIAN CORAL ACROPORA. Researchgate.NetNURA MAZNAN, MA SAMSHURI, S NURTAHIRAHJournal of Sustainability Science and Management, 2024 researchgate.Net, 19(10), 25–38. [CrossRef]

- Mbandzi-Phorego, N., Puccinelli, E., Pieterse, P. P., Ndaba, J., & Porri, F. (2024). Metal bioaccumulation in marine invertebrates and risk assessment in sediments from South African coastal harbours and natural rocky shores. Environmental Pollution, 355, 124230. [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, J. C., Wallace, M. W., & Gallagher, S. J. (2020). A Cenozoic Great Barrier Reef on Australia’s North West shelf. Global and Planetary Change, 184, 103048. [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, G. L., Baheerathan, R., Dougall, C., Ellis, R., Bennett, F. R., Waters, D., Darr, S., Fentie, B., Hateley, L. R., & Askildsen, M. (2021). Modelled estimates of dissolved inorganic nitrogen exported to the Great Barrier Reef lagoon. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 171, 112655. [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, L., Pineda, M.-C., Grech, A., & Thompson, A. (2024). 2022 Scientific Consensus Statement Question 1.2/1.3/2.1 What is the extent and condition of Great Barrier Reef ecosystems, and what are the primary threats to their health? [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C. D., Bayen, S., Desrosiers, M., Muñoz, G., Sauvé, S., & Yargeau, V. (2022). An introduction to the sources, fate, occurrence and effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals released into the environment. Environmental Research, 207, 112658. [CrossRef]

- Mitchelmore, C. L., He, K., Gonsior, M., Hain, E., Heyes, A., Clark, C., Younger, R., Schmitt-Kopplin, P., Feerick, A., Conway, A., & Blaney, L. (2019). Occurrence and distribution of UV-filters and other anthropogenic contaminants in coastal surface water, sediment, and coral tissue from Hawaii. Science of The Total Environment, 670, 398–410. [CrossRef]

- Moeller, M., Pawlowski, S., Petersen-Thiery, M., Miller, I. B., Nietzer, S., Heisel-Sure, Y., Kellermann, M. Y., & Schupp, P. J. (2021). Challenges in Current Coral Reef Protection – Possible Impacts of UV Filters Used in Sunscreens, a Critical Review. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8, 665548. [CrossRef]

- Moermond, C. T. A., Puhlmann, N., Pieters, L., Matharu, A., Boone, L., Dobbelaere, M., Proquin, H., Kümmerer, K., Ragas, A. M. J., Vidaurre, R., Venhuis, B., & De Smedt, D. (2025). Eco-pharma dilemma: Navigating environmental sustainability trade-offs within the lifecycle of pharmaceuticals – A comment. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 43, 101893. [CrossRef]

- Mofijur, M., Hasan, M. M., Ahmed, S. F., Djavanroodi, F., Fattah, I. M. R., Silitonga, A. S., Kalam, M. A., Zhou, J. L., & Khan, T. M. Y. (2024). Advances in identifying and managing emerging contaminants in aquatic ecosystems: Analytical approaches, toxicity assessment, transformation pathways, environmental fate, and remediation strategies. Environmental Pollution, 341, 122889. [CrossRef]

- Montano, S. (2020). The Extraordinary Importance of Coral-Associated Fauna. Diversity 2020, Vol. 12, Page 357, 12(9), 357. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M. B., Ross, J., Ellwanger, J., Phrommala, R. M., Youngblood, H., Qualley, D., & Williams, J. (2022). Sea Anemones Responding to Sex Hormones, Oxybenzone, and Benzyl Butyl Phthalate: Transcriptional Profiling and in Silico Modelling Provide Clues to Decipher Endocrine Disruption in Cnidarians. Frontiers in Genetics, 12, 793306. [CrossRef]

- Morin-Crini, N., Lichtfouse, E., Liu, G., Balaram, V., Ribeiro, A. R. L., Lu, Z., Stock, F., Carmona, E., Teixeira, M. R., Picos-Corrales, L. A., Moreno-Piraján, J. C., Giraldo, L., Li, C., Pandey, A., Hocquet, D., Torri, G., & Crini, G. (2022). Worldwide cases of water pollution by emerging contaminants: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2022 20:4, 20(4), 2311–2338. [CrossRef]

- Mozas-Blanco, S., Rodríguez-Gil, J. L., Kalman, J., Quintana, G., Díaz-Cruz, M. S., Rico, A., López-Heras, I., Martínez-Morcillo, S., Motas, M., Lertxundi, U., Orive, G., Santos, O., & Valcárcel, Y. (2023). Occurrence and ecological risk assessment of organic UV filters in coastal waters of the Iberian Peninsula. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 196, 115644. [CrossRef]

- Musial, J., Mlynarczyk, D. T., & Stanisz, B. J. (2023). Photocatalytic degradation of sulfamethoxazole using TiO2-based materials - Perspectives for the development of a sustainable water treatment technology. The Science of the Total Environment, 856(Pt 2). [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S. A., Al-Rudainy, A. J., & Salman, N. M. (2024). Effect of environmental pollutants on fish health: An overview. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research, 50(2), 225–233. [CrossRef]

- Mwadzombo, N. N., Tole, M. P., Mwashimba, G. P., & Cornec, F. Le. (2025). Signatures of Natural and Human Activities Revealed from Sediment Archives: A Case Study of the Kenyan Coral Reef Ecosystems. Thalassas, 41(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Nalley, E. M., Tuttle, L. J., Barkman, A. L., Conklin, E. E., Wulstein, D. M., Richmond, R. H., & Donahue, M. J. (2021). Water quality thresholds for coastal contaminant impacts on corals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Science of The Total Environment, 794, 148632. [CrossRef]

- Navidpour, A., Ahmed, M., Nanomaterials, J. Z.-, & 2024, undefined. (n.d.). Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceutical Residues from Water and Sewage Effluent Using Different TiO2 Nanomaterials. Mdpi.ComAH Navidpour, MB Ahmed, JL ZhouNanomaterials, 2024 mdpi.Com. Retrieved August 24, 2025, from https://www.mdpi.com/2079-4991/14/2/135.

- Navon, G., Nordland, O., Kaplan, A., Avisar, D., & Shenkar, N. (2024). Detection of 10 commonly used pharmaceuticals in reef-building stony corals from shallow (5–12 m) and deep (30–40 m) sites in the Red Sea. Environmental Pollution, 360, 124698. [CrossRef]

- Netshithothole, R., & Madikizela, L. M. (2024). Occurrence of Selected Pharmaceuticals in the East London Coastline Encompassing Major Rivers, Estuaries, and Seawater in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. ACS Measurement Science Au, 4(3), 283–293. [CrossRef]

- Newman, B. K., Velayudan, A., Petrović, M., Álvarez-Muñoz, D., Čelić, M., Oelofse, G., Colenbrander, D., le Roux, M., Ndungu, K., Madikizela, L. M., Chimuka, L., & Richards, H. (2024). Occurrence and potential hazard posed by pharmaceutically active compounds in coastal waters in Cape Town, South Africa. Science of The Total Environment, 949, 174800. [CrossRef]

- Oedin, M., Vajas, P., Dombal, Y., & Lavery, T. (2025). Nature under pressure in New Caledonia: Social crisis in a world key biodiversity hotspot. Ambio, 54(4), 734–739. [CrossRef]

- Ojemaye, C. Y., & Petrik, L. (2022). Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in the Marine Environment Around False Bay, Cape Town, South Africa: Occurrence and Risk-Assessment Study. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 41(3), 614–634. [CrossRef]

- Osuoha, J. O., Anyanwu, B. O., & Ejileugha, C. (2023). Pharmaceuticals and personal care products as emerging contaminants: Need for combined treatment strategy. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, 9, 100206. [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, D. Y., Delaunay, M., Sordello, R., Hédouin, L., Castelin, M., Perceval, O., Domart-Coulon, I., Burga, K., Ferrier-Pagès, C., Multon, R., Guillaume, M. M. M., Léger, C., Calvayrac, C., Joannot, P., & Reyjol, Y. (2021). Evidence on the impacts of chemicals arising from human activity on tropical reef-building corals; a systematic map. Environmental Evidence, 10(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, D. Y., Mell, H., Perceval, O., Burga, K., Domart-Coulon, I., Hédouin, L., Delaunay, M., Guillaume, M. M. M., Castelin, M., Calvayrac, C., Kerkhof, O., Sordello, R., Reyjol, Y., & Ferrier-Pagès, C. (2023). What are the toxicity thresholds of chemical pollutants for tropical reef-building corals? A systematic review. Environmental Evidence 2023 12:1, 12(1), 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Padhye, L. P., Srivastava, P., Jasemizad, T., Bolan, S., Hou, D., Shaheen, S. M., Rinklebe, J., O’Connor, D., Lamb, D., Wang, H., Siddique, K. H. M., & Bolan, N. (2023). Contaminant containment for sustainable remediation of persistent contaminants in soil and groundwater. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 455, 131575. [CrossRef]

- Pantos, O. (2022). Microplastics: impacts on corals and other reef organisms. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences, 6(1), 81–93. [CrossRef]

- Plastic Overshoot Day - Report 2025, EA-Earth Action, 2025. (2025). https://plasticovershoot.earth/report-2025/.

- Prichard, E., & Granek, E. F. (2016). Effects of pharmaceuticals and personal care products on marine organisms: from single-species studies to an ecosystem-based approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(22), 22365–22384. [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M., Das, I., Ghangrekar, M. M., & Blaney, L. (2022). Advanced oxidation processes: Performance, advantages, and scale-up of emerging technologies. Journal of Environmental Management, 316, 115295. [CrossRef]

- Rädecker, N., Pogoreutz, C., Voolstra, C. R., Wiedenmann, J., & Wild, C. (2015). Nitrogen cycling in corals: The key to understanding holobiont functioning? Trends in Microbiology, 23(8), 490–497. [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha P, P., Power, A., Chandra, S., & Chapman, J. (2018). Graphene, electrospun membranes and granular activated carbon for eliminating heavy metals, pesticides and bacteria in water and wastewater treatment processes. Analyst, 143(23), 5629–5645. [CrossRef]

- Rämö, R., Bonaglia, S., Nybom, I., Kreutzer, A., Witt, G., Sobek, A., & Gunnarsson, J. S. (2022). Sediment Remediation Using Activated Carbon: Effects of Sorbent Particle Size and Resuspension on Sequestration of Metals and Organic Contaminants. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 41(4), 1096–1110. [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, J. S. (2023). Advanced analytical techniques for microplastics in the environment: a review. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2023 47:1, 47(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Rathi, B. S., Kumar, P. S., & Show, P. L. (2021). A review on effective removal of emerging contaminants from aquatic systems: Current trends and scope for further research. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 409, 124413. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, V. S., Nautiyal, A., Ramlal, A., Kumar, G., Singh, P., Sharma, M., Robaina, R. R., Sahoo, D., & Baweja, P. (2024). Algae-coral symbiosis: fragility owing to anthropogenic activities and adaptive response to changing climatic trends. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Reef Water Quality Consensus. (2022). Evidence. 2022 Scientific Consensus Statement. http://reefwqconsensus.com.au/evidence.

- Reichert, J., Arnold, A. L., Hoogenboom, M. O., Schubert, P., & Wilke, T. (2019). Impacts of microplastics on growth and health of hermatypic corals are species-specific. Environmental Pollution, 254, 113074. [CrossRef]

- Reichert, J., Tirpitz, V., Anand, R., Bach, K., Knopp, J., Schubert, P., Wilke, T., & Ziegler, M. (2021). Interactive effects of microplastic pollution and heat stress on reef-building corals. Environmental Pollution, 290, 118010. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, E. R., & Naser, Humood. (2021). Natural resources management and biological sciences. https://books.google.com/books/about/Natural_Resources_Management_and_Biologi.html?id=NpYtEAAAQBAJ.

- Rizzi, C., Seveso, D., De Grandis, C., Montalbetti, E., Lancini, S., Galli, P., & Villa, S. (2023). Bioconcentration and cellular effects of emerging contaminants in sponges from Maldivian coral reefs: A managing tool for sustainable tourism. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 192, 115084. [CrossRef]

- Roslan, N. N., Lau, H. L. H., Suhaimi, N. A. A., Shahri, N. N. M., Verinda, S. B., Nur, M., Lim, J. W., & Usman, A. (2024). Recent Advances in Advanced Oxidation Processes for Degrading Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater—A Review. Catalysts 2024, Vol. 14, Page 189, 14(3), 189. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayo, F., Van Den Brink, P. J., & Mann, R. M. (2011). Ecological Impacts of Toxic Chemicals.

- Sepúlveda, M., Musiał, J., Saldan, I., Chennam, P. K., Rodriguez-Pereira, J., Sopha, H., Stanisz, B. J., & Macak, J. M. (2024). Photocatalytic degradation of naproxen using TiO2 single nanotubes. Frontiers in Environmental Chemistry, 5, 1373320. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. A. (2025). Advanced Oxidation Process in the Sustainable Treatment of Refractory Wastewater: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability (Switzerland), 17(8), 3439. [CrossRef]

- Sing Wong, A., Vrontos, S., & Taylor, M. L. (2022). An assessment of people living by coral reefs over space and time. Global Change Biology, 28(23), 7139–7153. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. Y., Morrato, E. H., Mora, N., Nguyen, V., Pinnock, H., & Winterstein, A. G. (2024). The Reporting Recommendations Intended for Pharmaceutical Risk Minimization Evaluation Studies: Standards for Reporting of Implementation Studies Extension (RIMES-SE). Drug Safety, 47(7), 655–671. [CrossRef]

- Sobha, T. R., Vibija, C. P., & Fahima, P. (2023). Coral Reef: A Hot Spot of Marine Biodiversity. 171–194. [CrossRef]

- Souter, D. (ed. ), Planes, S. (ed. ), Wicquart, J. (ed. ), Logan, M. (ed. ), Obura, D. (ed. ), & Staub, F. (ed. ). (2021). Status of coral reefs of the world: 2020: executive summary. https://bvearmb.do/handle/123456789/3190.

- Srain, H. S., Beazley, K. F., & Walker, T. R. (2021). Pharmaceuticals and personal care products and their sublethal and lethal effects in aquatic organisms. Cdnsciencepub.ComHS Srain, KF Beazley, TR WalkerEnvironmental Reviews, 2021 cdnsciencepub.Com, 29(2), 142–181. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C., Huang, Y., Bakhtiari, A. R., Yuan, D., Zhou, Y., & Zhao, H. (2024). Long-term exposure to climbazole may affect the health of stress-tolerant coral Galaxea fascicularis. Marine Environmental Research, 201, 106679. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q., Ren, S. Y., & Ni, H. G. (2020). Incidence of microplastics in personal care products: An appreciable part of plastic pollution. Science of The Total Environment, 742, 140218. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J., Wu, Z., Wan, L., Cai, W., Chen, S., Wang, X., Luo, J., Zhou, Z., Zhao, J., & Lin, S. (2021). Differential enrichment and physiological impacts of ingested microplastics in scleractinian corals in situ. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 404, 124205. [CrossRef]

- Tarrant, A. M., Atkinson, M. J., & Atkinson, S. (2004). Effects of steroidal estrogens on coral growth and reproduction. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 269, 121–129. [CrossRef]

- Temsah, Y. A., Mohamed, A. W., Saad, A. M., Hussein, H. N. M., & Mohammad, A. S. (2021). Environmental and geological study of the suggested marine port site at Sahl Hasheesh area, Hurghada, red sea coast, Egypt (A case study). Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries, 25(2), 573. [CrossRef]

- Thorel, E., Clergeaud, F., Rodrigues, A. M. S., Lebaron, P., & Stien, D. (2022). A Comparative Metabolomics Approach Demonstrates That Octocrylene Accumulates in Stylophora pistillata Tissues as Derivatives and That Octocrylene Exposure Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cell Senescence. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 35(11), 2160–2167. [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Sánchez, A., Sánchez-Quiles, D., Basterretxea, G., Benedé, J. L., Chisvert, A., Salvador, A., Moreno-Garrido, I., & Blasco, J. (2013). Sunscreen Products as Emerging Pollutants to Coastal Waters. PLOS ONE, 8(6), e65451. [CrossRef]

- Tzanakakis, V. A., Capodaglio, A. G., & Angelakis, A. N. (2023). Insights into Global Water Reuse Opportunities. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 13007, 15(17), 13007. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs, P. D. (2022). World Family Planning 2022: Meeting the changing needs for family planning: Contraceptive use by age and method.

- Uthicke, S., Fabricius, K., Brown, A., Molinari, B., & Robson, B. (2017). 2022 Scientific Consensus Statement Question 2.4 How do water quality and climate change interact to influence the health and resilience of Great Barrier Reef ecosystems? Question 2.4.1 How are the combined impacts of multiple stressors (including water quality) affecting the health and resilience of Great Barrier Reef coastal and inshore ecosystems? Question 2.4.2 Would improved water quality help ecosystems cope with multiple stressors including climate change impacts, and if so, in what way? [CrossRef]

- Value of the Reef - Great Barrier Reef Foundation - Great Barrier Reef Foundation. (n.d.). Retrieved February 10, 2025, from https://www.barrierreef.org/the-reef/the-value.

- Vasilachi, I. C., Asiminicesei, D. M., Fertu, D. I., & Gavrilescu, M. (2021). Occurrence and Fate of Emerging Pollutants in Water Environment and Options for Their Removal. Water 2021, Vol. 13, Page 181, 13(2), 181. [CrossRef]

- Vilela, C. L. S., Villela, H. D. M., Duarte, G. A. S., Santoro, E. P., Rachid, C. T. C. C., & Peixoto, R. S. (2021). Estrogen induces shift in abundances of specific groups of the coral microbiome. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Walpole, L. C., & Hadwen, W. L. (2022). Extreme events, loss, and grief—an evaluation of the evolving management of climate change threats on the Great Barrier Reef. Ecology and Society, 27(1), 37. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Xiang, L., Sze-Yin Leung, K., Elsner, M., Zhang, Y., Guo, Y., Pan, B., Sun, H., An, T., Ying, G., Brooks, B. W., Hou, D., Helbling, D. E., Sun, J., Qiu, H., Vogel, T. M., Zhang, W., Gao, Y., Simpson, M. J., … Tiedje, J. M. (2024). Emerging contaminants: A One Health perspective. The Innovation, 5(4). [CrossRef]

- Wanjeri, V. W. O., Okuku, E., Ngila, J. C., Ouma, J., & Ndungu, P. G. (2025). Distribution of pharmaceuticals in marine surface sediment and macroalgae (ulvophyceae) around Mombasa peri-urban creeks and Gazi Bay, Kenya. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 32(7), 4103–4123. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, J., Pearson, R., Lewis, S., Davis, A., & Waltham, N. (2024). Great Barrier Reef Ecohydrology. Oceanographic Processes of Coral Reefs, 105–125. [CrossRef]

- Weis, J. S. (2024). Marine Pollution: What Everyone Needs to Know® - Judith S. Weis - Google Books. https://books.google.com.pk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=kAUZEQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=weis+j+marine+pollution&ots=lxm_1xqrcz&sig=5dlbGEPVLwl2uBMihHN99INjgkM&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=weis%20j%20marine%20pollution&f=false.

- Wilkinson, J. L., Thornhill, I., Oldenkamp, R., Gachanja, A., & Busquets, R. (2024). Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in the Aquatic Environment: How Can Regions at Risk be Identified in the Future? Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 43(3), 575–588. [CrossRef]

- Willis, K. A., Serra-Gonçalves, C., Richardson, K., Schuyler, Q. A., Pedersen, H., Anderson, K., Stark, J. S., Vince, J., Hardesty, B. D., Wilcox, C., Nowak, B. F., Lavers, J. L., Semmens, J. M., Greeno, D., MacLeod, C., Frederiksen, N. P. O., & Puskic, P. S. (2022). Cleaner seas: reducing marine pollution. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 32(1), 145–160. [CrossRef]

- Wolfand, J. M., Sytsma, A., Taniguchi-Quan, K. T., Stein, E. D., & Hogue, T. S. (2023). Impact of wastewater reuse on contaminants of emerging concern in an effluent-dominated river. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11, 1091229. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W., Ahmed, W., Mahmood, M., Li, W., & Mehmood, S. (2023). Physiological and biochemical responses of soft coral Sarcophyton trocheliophorum to doxycycline hydrochloride exposure. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z., Cao, X., Su, H., Li, C., Lin, J., Tang, K., Zhang, J., Fan, H., Chen, Q., Tang, J., & Zhou, Z. (2025). Coral-Symbiodiniaceae symbiotic associations under antibiotic stress: Accumulation patterns and potential physiological effects in a natural reef. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 486, 137039. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Sik Ok, Y., Bank, M. S., & Sonne, C. (2023). Macro- and microplastics as complex threats to coral reef ecosystems. Environment International, 174, 107914. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H., Wu, M., Sonne, C., Lam, S. S., Kwong, R. W. M., Jiang, Y., Zhao, X., Sun, X., Zhang, X., Li, C., Li, Y., Qu, G., Jiang, F., Shi, H., Ji, R., & Ren, H. (2023). The hidden risk of microplastic-associated pathogens in aquatic environments. Eco-Environment & Health, 2(3), 142–151. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R., Lu, G., Yan, Z., Jiang, R., Bao, X., & Lu, P. (2020). A review of the influences of microplastics on toxicity and transgenerational effects of pharmaceutical and personal care products in aquatic environment. Science of The Total Environment, 732, 139222. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S., Qin, L., Li, Z., Hu, X., & Yin, D. (2023). Effects of nanoplastics and microplastics on the availability of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in aqueous environment. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 458, 131999. [CrossRef]

- Zinken, J. F., Pasmooij, A. M. G., Ederveen, A. G. H., Hoekman, J., & Bloem, L. T. (2024). Environmental risk assessment in the EU regulation of medicines for human use: an analysis of stakeholder perspectives on its current and future role. Drug Discovery Today, 29(12), 104213. [CrossRef]

- Zitoun, R., Marcinek, S., Hatje, V., Sander, S. G., Völker, C., Sarin, M., & Omanović, D. (2024). Climate change driven effects on transport, fate and biogeochemistry of trace element contaminants in coastal marine ecosystems. Communications Earth and Environment, 5(1), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ziylan-Yavas, A., Santos, D., Flores, E. M. M., & Ince, N. H. (2022). Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs): Environmental and public health risks. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy, 41(4), e13821. [CrossRef]

| PPCP | Found in | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfamethoxazole | Red sea stony corals Seawater of Eastern Cape coastline, South Africa |

(Navon et al., 2024) (Netshithothole & Madikizela, 2024) |

| Oxybenzone (Benzophenone-3) | Coastal waters of Oahu, Hawaii, Iberian coastal marine regions | (Mitchelmore et al., 2019) (Mozas-Blanco et al., 2023) |

| Caffeine | Southern North Sea coastal waters | (Adenaya et al., 2024) |

| Diclofenac | Mombasa Creeks & Ghazi Bay, Kenya False Bay, Cape Town, South Africa |

(Wanjeri et al., 2025) (Ojemaye & Petrik, 2022) |

| Ibuprofen | East London coastline, South Africa | (Netshithothole & Madikizela, 2024) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) / Salicylic acid | Cape Town, South Africa | (Newman et al., 2024) |

| Trimethoprim | Laizhou Bay, Bohai Sea, China | (Han et al., 2021) |

| Tetracyclines (e.g., tetracycline, oxytetracycline, chlortetracycline, doxycycline) | Coastal waters and surface sediments of the Yangtze River Estuary, Beibu Gulf, China Mahdia coastline, Mediterranean Tunisia |

(Liu et al., 2023) (Leng et al., 2020) (Fenni et al., 2025) |

| Octocrylene | South Carolina Oahu, Hawaii Balearic Islands, Mediterranean Sea |

(Bratkovics et al., 2015) (Mitchelmore et al., 2019) (Agawin et al., 2024) |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) | Surface microlayer nearshore water, Majorca Island (Spain) | (Tovar-Sánchez et al., 2013) |

| Contaminant Group | Contaminant | Coral Species | Impact on coral health | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical and Personal care Products (PPCPs) | Climbazole | Galaxea fascicularis | Decline in photosynthetic efficiency, triggered oxidative stress | Sun et al., 2024) |

| Sunscreen formulations (ZnO) | Stylophora pistillata | Coral bleaching, loss of photosynthetic capacities | (Fel et al., 2019) | |

| Oxybenzone (Benzophenone-3) | Stylophora pistillata | Induced bleaching, DNA damage, skeletal malformation, high larval mortality | (Downs et al., 2015) | |

| Triclosan | Porites lutea | Lowers the density and Chlorophyll A content of the symbiotic zooxanthellae, impaired antioxidant enzyme activity | (Liang et al., 2024) | |

| Ofloxacin (Fluoroquinolone) | Galaxea fascicularis | Reduce antioxidant levels in the algal symbionts | (Yan et al., 2025) | |

| Doxycycline (DOX) | Sarcophyton trocheliophorum | Altered bleaching indicators, oxidative stress markers, enzyme and detox responses | (Xu et al., 2023) | |

| Microplastics | Pocillopora damicornis | Activates its apoptosis, disturb its symbiosis | (Tang et al., 2021) | |

| Lophelia pertusa | Decline in skeletal growth rates, reduces calcination | (Chapron et al., 2018) | ||

| Heliopora coerulea | Negative impacts on growth parameters, reduced calcification rates | (Reichert et al., 2019) | ||

| Pseudodiploria clivosa | Reduced calcification and tissue surface area | (Hankins et al., 2021) | ||

| Endocrine disrupting chemicals | Estradiol | Montipora spp | Reduction of egg–sperm bundles | (Tarrant et al., 2004) |

| Estrone | Montipora spp | Increase in tissue thickness | ||

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Amphiprion ocellaris | Decreased aggression, altered brain transcript levels, interfered with gonad morphology and sex hormone profile | (Gonzalez et al., 2021) | |

| Ethinylestradiol (EE2) | Amphiprion ocellaris | Interfered with sex hormones and altered expression of one transcript in the brain toward the female profile | (Gonzalez et al., 2021) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).