1. Introduction

Phospholipids are a type of complex lipid, which is essential for the growth and development in aquatic animals [

1,

2]. There are two ways for animals to obtain phospholipids, the endogenous synthesis and exogenous synthesis pathways [

3]. Generally, it is believed that the endogenous phospholipid synthesis capacity of aquatic animals is limited, and the phospholipids mainly obtained from the diets [

4]. Therefore, a large number of studies have reported the functions of dietary phospholipids in fish and crustaceans, and have demonstrated the significance of exogenous phospholipids for the growth and development of crustaceans [

5]. However, the types of dietary phospholipids and the unsaturation degree of the fatty acids are quite different from those required for the biological membranes of fish, shrimp and crab. Therefore, it is speculated that they need to go through a process of

“decomposition -synthesis-remodeling

” before being utilized by aquatic animals [

6]. Furthermore, an increasing number of studies have reported that as long as the diets contain sufficient substances for the synthesis of phospholipids, some crustaceans are fully capable of meeting their needs through endogenous synthesis of phospholipids [

7]. Therefore, the significance of endogenous synthesis of phospholipids has gradually been concerned.

Phospholipids are mainly composed of polar lipids such as phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylinositol. Among them, phosphatidylcholine is the most predominant component [

8]. In mammals, the process of phosphatidylcholine synthesis is relatively well understood. It is mainly synthesized through the Kennedy pathway, which consists of two routes: CDP-choline and CDP-ethanolamine [

3]. Choline is the main precursor substance for this process, and this process begins with choline, which is then converted into phosphatidylcholine through a series of enzymatic reactions. This pathway has been extensively studied in mammals, fruit flies, yeast, and nematodes [

3,

9,

10]. The CTP-phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT) is the rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway [

11]. In aquatic animals, although the process of phosphatidylcholine synthesis has not been fully studied, related enzymes and protein families for phosphatidylcholine synthesis have also been discovered in pufferfish (

Takifugu rubripes), zebrafish (

Danio rerio), and Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar L.) [

12,

13]. Therefore, some studies reported that the synthesis pathway of phosphatidylcholine in fish is similar to that in mammals [

14].

Choline is an important substrate for the endogenous synthesis of phosphatidylcholine in aquatic animals, which is associated with a series of physiological functions. On the one hand, choline plays a crucial role on the growth performance of aquatic animals. It has been reported that dietary 6000 mg/kg choline significantly increased the growth of largemouth bass [

15]. However, some other studies have shown that dietary choline reduced the growth of pacific white shrimp (

Litopenaeus vannamei) [

16]. The differences in the growth-promoting functions of choline in aquatic animals are not only due to the differences among species, but although the understanding of the function of choline is still not deep enough. On the other hand, choline can reprogram the lipid metabolism of aquatic animals. The deficiency of choline in the fish diet could lead to the lipid metabolism disorders, and resulting in lipid accumulation in the liver of fish [

17,

18]. Some similar results were reported in the shrimps [

19]. These results indicate that choline is closely related to the lipid metabolism of aquatic animals. Besides, choline is the main source of methyl donors in the biological organism, and plays a significant role in neural regulation and the immune system [

20,

21]. The lack of choline in the diets could affect the immunity and health of aquatic animals [

22,

23]. The potential mechanism is that choline could enhance the immunity by up-regulating the expressions of genes related with the mTOR signaling pathway [

24]. In summary, choline is one of the important nutrients that affect the synthesis of phospholipids, lipid metabolism, growth and health in aquatic animals.

The Chinese mitten crab (

Eriocheir sinensis) is an important species for aquaculture [

25]. Unfortunately, due to the quality issues of the commercial crab diets, the adoption rate of the commercial diets in production has not been high so far. Therefore, clarify the precise lipid nutrition, especially phospholipid nutrition, is particularly crucial for the high-quality diet’s formulation. Based on the above discussion, the purpose of this study is to determine whether exogenous choline could affect the synthesis of endogenous phospholipids and lipid metabolism in Chinese mitten crabs. The results may provide theoretical references for precise phospholipids nutrition of crab.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Diets

In order to investigate the effects of choline on the synthesis of endogenous phospholipids, six experimental diets were formulated by adding 0%, 0.2% and 0.4% choline to low phospholipid (0% PL) and normal phospholipid (2% PL) diets, respectively. The formulation and proximate nutrient composition of diets were shown in the

Table 1. In order to prepare the experimental diets, all ingredients were ground into power and sieved through 60 mesh strainers. After when, the ingredients in were precisely weighed according to the formulation and mixed using an electric mixer. Choline is added to the diets by dissolving it in water. Subsequently, 2.5 mm diameter diets were pelleted with a screw-press pelletizer (F-26, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China). Finally, all the diets were air dried in room for approximately 48 h to reduce the moisture to less than 10%. After drying, all diets were stored at -20 °C until used.

Table 1.

Ingredients and proximate compositions of the experimental diets (%).

Table 1.

Ingredients and proximate compositions of the experimental diets (%).

| Ingredients |

Low phospholipids (0% PL) |

Normal phospholipids (2% PL) |

| 0% CHO |

0.2% CHO |

0.4% CHO |

0% CHO |

0.2% CHO |

0.4% CHO |

| Casein |

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

| Gelatin |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

| Corn starch |

26 |

26 |

26 |

26 |

26 |

26 |

| Cholesterol |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| Fish oil |

4.5 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

| Soybean oil |

4.5 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

| Arginine |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

| Methionine |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| Lysine |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

d Vitamin premixes |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

|

e Mineral premixes |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

| Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

c Attractant |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

b Butylated hydroxytoluene |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| Soybean lecithin |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

a Choline |

0 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose |

8.6 |

8.4 |

8.2 |

8.6 |

8.4 |

8.2 |

| Nutritional analysis (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Crude protein |

49.88 |

49.49 |

50.87 |

50.40 |

51.08 |

50.62 |

| Crude lipid |

10.46 |

9.45 |

9.77 |

10.77 |

10.51 |

10.07 |

| Ash |

3.06 |

3.02 |

2.95 |

3.18 |

3.07 |

3.18 |

| Moisture |

7.65 |

7.38 |

7.86 |

8.68 |

8.91 |

8.59 |

2.2. Feeding Trial and Sampling

The feeding experiment was carried out in the Aquaculture Center of Huzhou University (Huzhou, Zhejiang). Crabs were obtained from a local farm. The experimental water was aerated fully before use. Prior to the feeding trial, all of the experimental crabs were stocked in some 300 L tanks (100 × 80 × 60 cm) to acclimatize the experimental environment. After then, crabs (0.4 ± 0.03 g, mean ± S.D.) with intact appendages were randomly distributed into six dietary treatments. Each treatment was set 4 paralleled tanks, and each tank containing 25 crabs. Four bundles of corrugated plastic pipes and arched tiles were placed in each tank as shelters to reduce attacking behavior. Diets with a daily ration of 4% body weight were hand-fed to crabs twice (8:00 and 18:00). Feces were removed in the morning (09:00), and the water of 30% tank volume was exchanged daily. During the experimental period, the water temperature varied from 18 °C to 24 °C. The pH value varied between 7.0 and 8.0. Dissolved oxygen was above 7 mg/L. The ammonia was below 0.2 mg/L. The feeding duration was 8 weeks.

At the end, all the crabs from each tank were anesthetized with crushed pieces of ice, and then counted and group-weighed by tank. Following, 10 crabs from each tank were randomly selected for sampling. The hepatopancreas samples were collected and put into liquid nitrogen immediately and then stored at -80 °C for the analyses of gene expression.

2.3. Determination of Growth Performance

Weight gain (WG, %) = (final crab weight – initial crab weight) × 100 / initial crab weight;

Specific growth rate (SGR, %) = (Ln (final crab weight) - Ln (initial crab weight)) × 100 / days;

Hepatopancreas somatic index (HSI, %) = hepatopancreas weight / final whole-body weight × 100.

2.4. Proximate Nutrient Composition of Experimental Diets

The proximate nutrient compositions of experimental diets were determined by the standard procedures using proximate composition analysis [

26]. Each diet was randomly collected four duplicate samples for proximate nutrient composition analysis (n = 4). All the samples were spread out evenly in a glass petri dish and dried until they reached a constant weight (at 105 °C). The lipid of each diet was extracted using the chloroform-methanol method. The crude lipid was quantified using a KjeltecTM 8200 (Foss, Hoganas, Sweden). Ash was measured using a muffle furnace (PCD-E3000 Serials, Peaks, Japan) at 550 °C for 6 h.

2.5. Gene Expression

Total RNA was extracted from the hepatopancreas using the RNAiso Plus (CAT # 9109, Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The total RNA concentration and quality were estimated using the Nano Drop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo, USA). If the ratio of A260/A280 was between 1.8 to 2.0, the sample was used for reverse transcribed using a PrimeScript™ RT master mix reagent kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The specific primers for the genes of E. sinensis were designed based on the NCBI data base (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCA_024679095.1/) using NCBI Primer BLAST (

Table 2). The RT-PCR amplification reactions were performed using an CFX96 Real-Time PCR system (Bio-rad, Richmond, CA). Samples were run in quintuplicate and normalized with the control gene β-actin and glyceraldehyde-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The gene expression levels were calculated by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes [

27].

Table 2.

Primer sequences of the experimental genes.

Table 2.

Primer sequences of the experimental genes.

| Primer name |

Sequences (5′-3′) |

Product length |

|

β-actin F |

TGGGTATGGAATCCGTTGGC |

101 bp |

|

β-actin R |

AGACAGAACGTTGTTGGCGA |

|

gapdh F |

CACCGTGCATGCTGTTACTG |

108 bp |

|

gapdh R |

ACCAGTGGAGGATGGGATGA |

|

fabp3 F |

CCACCGAGGTCAAGTTCAAGC |

195 bp |

|

fabp3 R |

TCACACCATCACACTCCGACAC |

|

fatp4 F |

GACGGCAGACACGGAAAGAGA |

101 bp |

|

fatp4 R |

CAGGTGGAGGCAAGCAAACTC |

|

fatp6 F |

TGATGGGAAGGCAGGAATGG |

119 bp |

| fatp6 R |

TGCGGATGAAGCGAGGTACA |

|

elovl6 F |

TGAGAAGCGGCAATGGATGAAG |

164 bp |

|

elovl6 R |

TGGAGAAGAGGGCCAGGAAGAC |

|

Δ9 fad F |

TGGCACAACTACCACCACGTCT |

160 bp |

|

Δ9 fad R |

TCCTCTTCTCGATCATCTCCGG |

|

cpt-1a F |

CATCTGGACACCCACCTCCA |

183 bp |

|

cpt-1a R |

ATCTCCTCACCCGGCACTCT |

|

cpt-1b F |

GGCATTCTCCTTTGCCATCAC |

138 bp |

|

cpt-1b R |

ACACCACACCGCACATTGTTC |

|

cpt-2 F |

AGCAGGCAGTGGCTCAGTTTA |

169 bp |

|

cpt-2 R |

AAGGCAAGGAAGGGGTTGTAG |

|

caat F |

CATCAAGAGCCAGGAGCCCA |

172 bp |

|

caat R |

CTTCAACAGCAGCCCGCAAA |

|

cet F |

CAAGCTTCTCGACTCTGGCA |

140 bp |

|

cet R |

TGGCCTTCATGTAAGCAGCA |

|

cct F |

CCCTGGACACTAGAGGACGA |

128 bp |

|

cct R |

ACGAACATTCCACGAGCCTT |

|

lpcat F |

TATGGCTGATGCTTTGGGGG |

145 bp |

|

lpcat R |

TGTCTGGCAGGGTAGGTTCT |

|

pla2 F |

GCCTCTGGACGACTGTGAAA |

192 bp |

|

pla2 R |

TTTGGGGTATTTGGGTCCCG |

|

|

plb F |

CTGCACCCCTCCTTACAGTG |

103 bp

|

|

plb R |

GTGAGACCTGTGACCCAGTG |

|

nte1 F |

TGTACTTTTCCGCCGCTTCT |

156 bp |

|

nte1 R |

GGCCGGATGTATTCGCAGTA |

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 25.0 for Windows (SPSS, Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine if there was any interaction between phospholipids levels and choline levels. At the same phospholipids level, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the significant differences among crabs fed the diets with different choline levels. When the means of each treatment were significantly different, Duncan’s multiple range test was used to compare means among these treatments. At the choline level, independent-samples T test was used to determine significant differences between crabs fed with the different choline levels. Significance was set at P < 0.05. The data were represented as the mean ± standard error of mean (S.E.).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Dietary Choline on the Growth Performance of Juvenile Chinese Mitten Crab

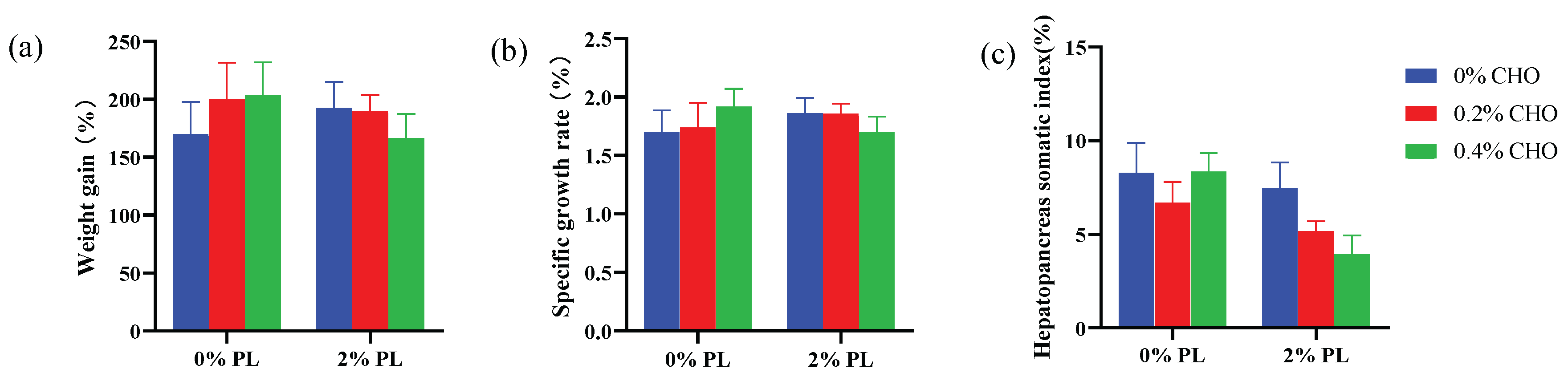

In the low phospholipids (0% PL) groups, although dietary choline level did not significantly affect the weight gain (WG) and specific growth rate (SGR), but the WG and SGR showed an upward trend with the increasing dietary choline supplementation (P > 0.05). However, in the normal phospholipids (2% PL) groups, dietary choline decreased the WG and SGR, but there were on significant differences among each choline diets (P > 0.05). In the low phospholipids (0% PL) groups, dietary choline levels did not significantly affect the hepatopancreas somatic index (HSI) of crabs (P > 0.05). However, in the normal phospholipids (2% PL) groups, dietary choline decreased HSI, but there were on significant differences among each choline diets (P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effects of dietary choline on the growth performance of juvenile Chinese mitten crab.

Figure 1.

Effects of dietary choline on the growth performance of juvenile Chinese mitten crab.

3.2. Effects of Dietary Choline on the Relative mRNA Expression of Genes Related to Phospholipid Synthesis in Juvenile Chinese Mitten Crab

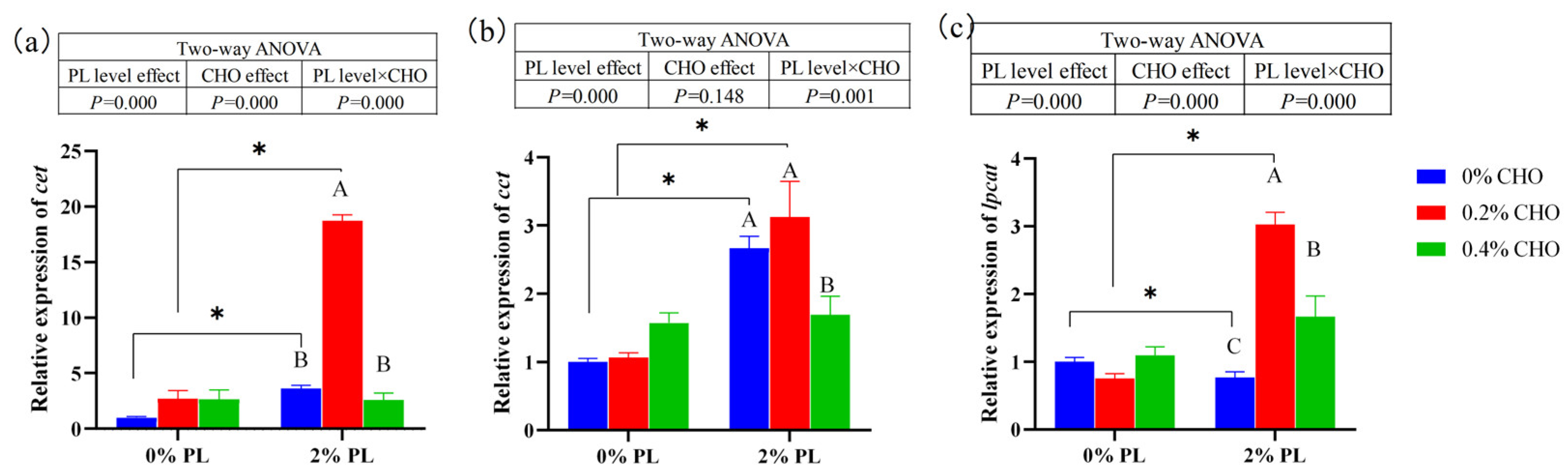

Dietary choline levels and phospholipids levels significantly affected the relative mRNA expressions of CTP-phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase (cet) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase (lpcat) (significant main effects) and there is a significant interaction between them (P < 0.05). The further analysis showed that in the 0% choline and 0.2% choline groups, the relative mRNA expressions of cet and lpcat of crabs fed the 2% PL diets were significantly up-regulated compared with the crabs fed the 0% PL diets (P < 0.05). The dietary choline level did not have significant main effect on the relative mRNA expression of CTP-phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (cct) (P > 0.05). While, the dietary phospholipids level had a significant main effect on the relative mRNA expression of (cct) (P < 0.05). In the normal phospholipids (2% PL) groups, the relative expressions of cet and lpcat of crabs fed the 0.2% CHO diets were significantly up-regulated compared with the crabs fed the 0% CHO and 0.4% CHO diets (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effects of dietary choline on the relative mRNA expression of genes related to phospholipid synthesis in juvenile Chinese mitten crab. Note: cet: CTP-phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase; cct: CTP-phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase; lpcat: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase. Different letters at the top of the bar graph indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), the connected lines are significant differences, P < 0.05 (marked *), the same below. Number of biological replicates (n = 6).

Figure 2.

Effects of dietary choline on the relative mRNA expression of genes related to phospholipid synthesis in juvenile Chinese mitten crab. Note: cet: CTP-phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase; cct: CTP-phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase; lpcat: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase. Different letters at the top of the bar graph indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), the connected lines are significant differences, P < 0.05 (marked *), the same below. Number of biological replicates (n = 6).

3.3. Effects of Dietary Choline on the Relative mRNA Expression of Genes Related to Phospholipid Catabolism in Juvenile Chinese Mitten Crab

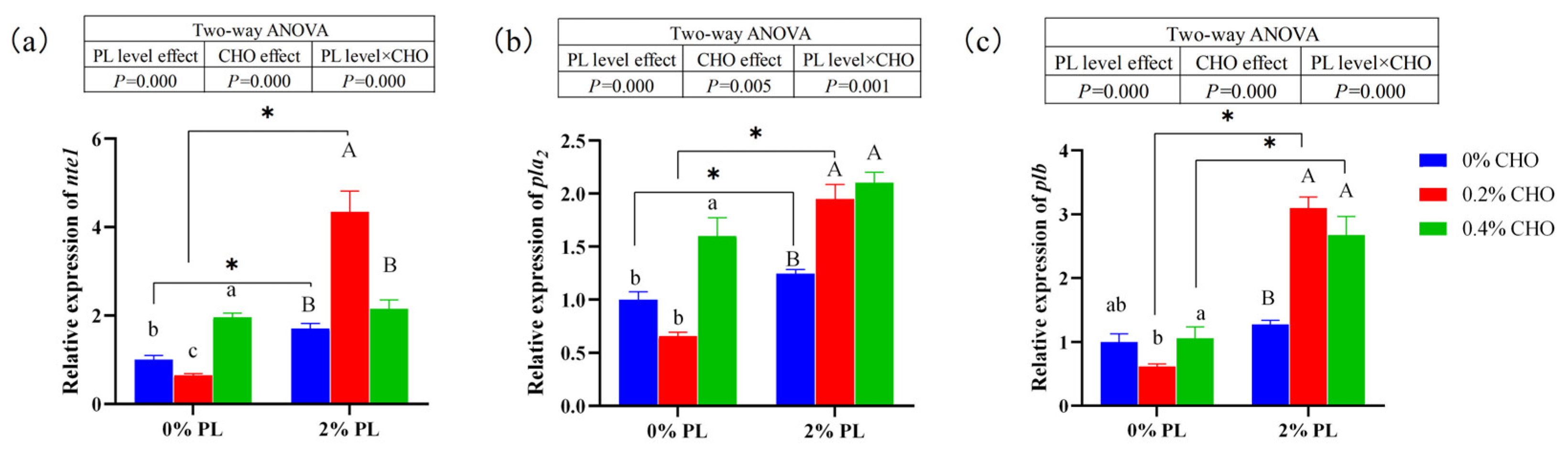

As shown in the

Figure 3, dietary choline levels and phospholipids levels had significant main effects on the relative mRNA expression of neuropathy target enzyme 1 (

nte1), phospholipase A2 (

pla2) and phospholipase B (

plb), and there is a significant interaction between them (

P < 0.05). The further analysis showed that in the 0% choline and 0.2% choline groups, the relative mRNA expressions of

nte1 and

pla2 of crabs fed the 2% PL diets were significantly up-regulated compared with the crabs fed the 0% PL diets (

P < 0.05). Moreover, in the 0% PL diets, the relative mRNA expressions of nte1 and

pla2 of crabs fed the 0.4% CHO diets were significantly up-regulated compared with the crabs fed the 0% CHO and 0.2% CHO diets (

P < 0.05). While, in the 2% PL diets, the highest mRNA expressions of

nte1 and

pla2 were observed in the crabs fed the 0.2% CHO (

P < 0.05). The relative mRNA expressions of

plb of crabs fed the 2% PL diets were significantly up-regulated compared with the crabs fed the 0% PL diets under the 0.2% CHO and 0.4% CHO diets (

P < 0.05). In the 0% PL diets, crabs fed the 0.2% CHO diets showed the lowest mRNA expressions of

plb,

nte1 and

pla2 (

P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effects of dietary choline on the relative mRNA expression of genes related to phospholipid catabolism in juvenile Chinese mitten crab.Note: nte1: neuropathy target enzyme 1; pla2: phospholipase A2; plb: phospholipase B.

Figure 3.

Effects of dietary choline on the relative mRNA expression of genes related to phospholipid catabolism in juvenile Chinese mitten crab.Note: nte1: neuropathy target enzyme 1; pla2: phospholipase A2; plb: phospholipase B.

3.4. Effects of Dietary Choline on the Relative mRNA Expression Genes Related to Fatty Acid Absorption, Decomposition and Synthesis in Juvenile Chinese Mitten Crab

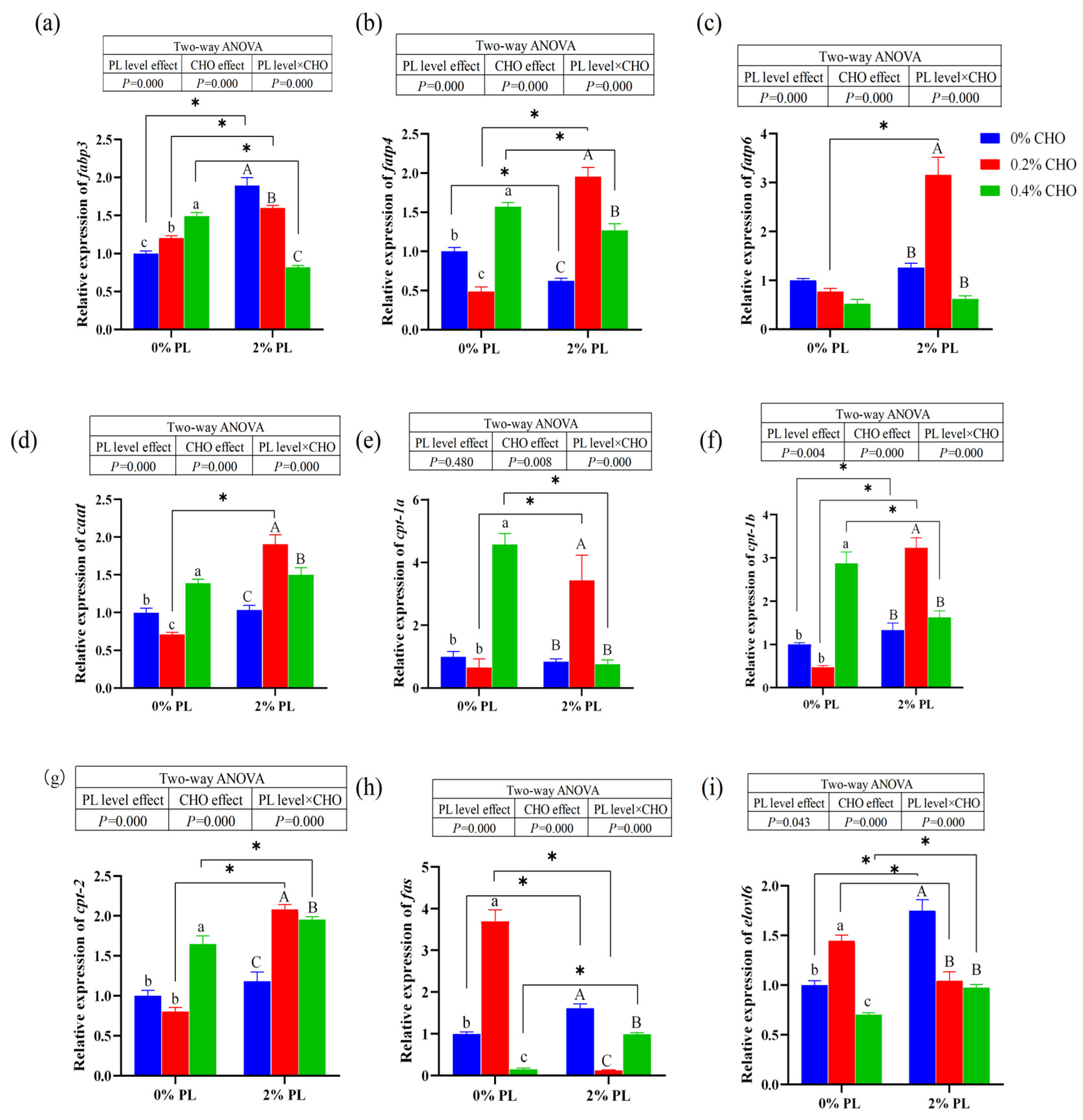

As shown in the

Figure 4 dietary choline levels and phospholipids levels had significant main effects on the relative mRNA expression of fatty acid binding protein 3 (

fabp3), fatty acid transporter protein 4 (

fatp4), fatty acid transporter protein 6 (

fatp6), carnitine acetyltransferase (

caat), carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1b (

cpt-1b), carnitine palmitoyltransferase-2 (

cpt2), fatty acid synthase (

fas) and fatty acid elongase 6 (

elovel6), and there is a significant interaction between them (

P < 0.05). Dietary choline levels had significant main effect on the relative mRNA expression of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1a (

cpt-1a) (

P < 0.05). In the low phospholipids (0% PL) groups, the relative mRNA expression of

fabp3 was significantly up-regulated with the increasing dietary choline supplementation (

P < 0.05). However, in the normal phospholipids (2% PL) groups, the relative mRNA expression of

fabp3 was significantly down-regulated with the increasing dietary choline supplementation (

P < 0.05). The relative mRNA expressions of

fatp4,

caat,

cpt-1a,

cpt-1b and

cpt2 were significantly down-regulated in the crabs fed the 0.2% CHO diet in the low phospholipids (0% PL) groups (

P < 0.05). On the contrary, the relative mRNA expressions of

fas and

elovel6 were significantly up-regulated in the 0.2% CHO diet in the low phospholipids (0% PL) groups (

P < 0.05). Moreover, the relative mRNA expressions of

fatp4,

fatp6,

caat and

cpt2 were significantly up-regulated in the crabs fed the 0.2% CHO diet in the normal phospholipids (2% PL) groups (

P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of dietary choline on the relative mRNA expression genes related to fatty acid absorption, decomposition and synthesis in juvenile Chinese mitten crab. fabp3: Fatty acid binding protein 3. fatp4: Fatty acid transporter protein 4. fatp6: Fatty acid transporter protein 6. caat: Carnitine acetyltransferase. cpt-1a: Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1a. cpt-1b: Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1b. cpt-2: Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-2. fas: Fatty acid synthase. elovl6: Fatty acid elongase 6.

Figure 4.

Effects of dietary choline on the relative mRNA expression genes related to fatty acid absorption, decomposition and synthesis in juvenile Chinese mitten crab. fabp3: Fatty acid binding protein 3. fatp4: Fatty acid transporter protein 4. fatp6: Fatty acid transporter protein 6. caat: Carnitine acetyltransferase. cpt-1a: Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1a. cpt-1b: Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1b. cpt-2: Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-2. fas: Fatty acid synthase. elovl6: Fatty acid elongase 6.

4. Discussion

Some previous studies had reported that a certain dietary choline could improve the growth of aquatic animals, such as largemouth bass [

15] Asian swamp eel [

28] and Bluntnose black bream [

29]. In the present study, dietary choline did not significantly affect the growth of Chinese mitten crab in the both low phospholipids (0% PL) and normal phospholipids (2% PL) groups. Our result was inconsistent with these studies, which might be caused by the species-species differences. However, choline tends to promote growth in the low phospholipids condition. Therefore, there may also be significant differences in growth performance after an extending feeding period. Some other studies have reported that dietary choline could reduce the growth shrimp. In the present study, dietary choline slightly reduced growth of crabs in the normal phospholipids groups, which is consistent with the result on the pacific white shrimp (

L. vannamei) [

16]. In summary, supplementation of choline in the diet could to some extent promote the growth (no significant differences) of crabs under low phospholipid condition, achieving results similar to those of the normal phospholipid group. Moreover, it is not recommended to supplement choline in the diets under the condition of abundant phospholipids.

Choline is a precursor for the synthesis of phospholipids and the growth-promoting effect of choline may be related to the synthesis of phospholipids. Therefore, our study investigated the effects of choline on the key genes involved in phospholipids synthesis. Our results showed that choline up-regulated the relative mRNA expressions of CTP-phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase (

cet) and CTP-phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (

cct). CCT and CET are the key enzymes for the synthesis of PC and PE, and play a limiting role in the pathway. They can catalyze the formation of cytidine diphosphate choline and cytidine diphosphate ethanolamine from phosphocholine and phosphoethanolamine, and finally produce PC and PE [

3]. Therefore, choline may be able to promote the synthesis of phospholipids under low phospholipid condition. Besides, our result showed that dietary supplementation with phospholipids significantly up-regulated the relative mRNA expressions of lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase

(lpcat). IPCAT is a key enzyme for phospholipid remodeling and can participate in the acylation reaction of lysophosphatidylcholine [

30]. This result indicated that dietary phospholipids may need to be restructured before they can be utilized due to the types of dietary phospholipids and the unsaturation degree of the fatty acids are quite different from those required for the biological membranes. To verify the above hypothesis, our study investigated the effect of choline on the phospholipid’s catabolism. Phospholipase B (

plb) can hydrolyze lysophospholipids to produce glycerophosphocholine [

31]. Moreover, Phospholipase A2 (

pla2) can specifically hydrolyze the second ester bond in glycerophospholipid molecules, generating products such as lysophospholipid 1 and fatty acids [

32]. Neurosin target enzyme 1 (

nte1) can regulate the degradation of choline phospholipids to maintain the choline cycle and lipid balance, which catalyzes the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine through the CDP-choline pathway [

33]. These enzymes are key targets involving in the remodeling and synthesis processes of phospholipids. In the present study, 2% phospholipids significantly up-regulated the relative mRNA expressions of

plb,

pla2 and

nte1, which validates the assumptions we made above. Moreover, our results showed that dietary choline phospholipids catabolism showed a significant interaction, indicating that dietary choline could affect the decomposition and remodeling of phospholipids. In summary, choline could promote phospholipid synthesis under low phospholipid condition, and it can facilitate the catabolism and remodeling of phospholipids under high phospholipid condition.

During the process of phospholipid synthesis, there is lipid synthesis and catabolism. Therefore, our study subsequently explored the effects of choline on the lipid metabolism. Some previous studies have reported that fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs) and fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs) are the key factors for the transmembrane transport of fatty acids [

34,

35,

36] In the present study, dietary choline significantly up-regulated the relative mRNA expressions of

fabp3 and

fatp4, which indicated that choline activated the transport of fatty acids. In addition, dietary 0.4% CHO significantly up-regulated the relative mRNA expression of

cpt-2,

cpt-1a and

cpt-1b. CPT-2, CPT-1a and CPT-1b play crucial roles in the process of fatty acid metabolism, in which CPT-1a and CPT-1b involving the entry of fatty acids into mitochondria [

37,

38], and CPT-2 can catalyze the conversion of acylcarnitine to acylcoenzyme A, allowing fatty acids to enter the mitochondrial matrix for β-oxidation [

39,

40]. Thus, we speculated that dietary supplementation with 0.4% choline promoted the fatty acid catabolism in the Chinese mitten crab, and it might be to generate energy for phospholipid synthesis.

Phospholipids synthesis not only requires energy but also specific fatty acids. Therefore, we hypothesize that there is also associated fatty acid synthesis metabolism during the process of phospholipid synthesis. Fatty acid synthase (

fas) is a key enzyme for the de novo synthesis of fatty acid chain and the fatty acid elongase (

elove6) is a key rate-limiting enzyme that determines the length of the fatty acid chain [

5,

41,

42]. Our study showed that 0.2% CHO significantly enhanced the expression of

fas and

elovl6 under low phospholipids condition. Thus, we speculated that choline promoted the de novo synthesis of fatty acids, possibly to provide the necessary substrates for phospholipid synthesis.

5. Conclusions

This study indicated that dietary supplementation with 0.4% choline could up-regulated the genes related to phospholipids synthesis (cet and cct), fatty acid catabolism (cpt-2, cpt-1a and cpt-1b) and fatty acid synthesis (fas and elove6) under low phospholipids condition. While, dietary 0.2% Choline could improve the decomposition and remodeling of phospholipids by up-regulated the mRNA expressions of plb, pla2 and nte1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X and C.Q.; methodology, Y.X.; software, M.S.; validation, Y.Z; formal analysis, P.W.; investigation, Y.X.; resources, J.Y.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, C.Q.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, C.Q.; project administration, J.Y.; funding acquisition, C.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LTGN23C190003, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 3247210153), Key Laboratory of Aquatic Animal Nutrition, Jiangsu (KJS2341), Huzhou Science and Technology Plan (2022GZ38), Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang Province (No, 2023C02024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments in Huzhou University (approval code 20220701, approved on 1 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PL |

Phospholipids |

| WG |

Weight gain |

| SGR |

Specific growth rate |

| HSI |

Hepatopancreas somatic index |

| cet |

CTP-phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase |

| cct |

CTP-phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase |

| lpcat |

Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase |

| nte1 |

Neuropathy target enzyme 1 |

| pla2 |

Phospholipase A2 |

| plb |

Phospholipase B |

| fabp3 |

Fatty acid binding protein 3 |

| fatp4 |

Fatty acid transporter protein 4 |

| fatp6 |

Fatty acid transporter protein 6 |

| cpt-2 |

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-2 |

| caat |

Carnitine acetyltransferase |

| cpt-1a |

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1a |

|

cpt-1b

|

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1b |

| fas |

Fatty acid synthase |

| elovel6 |

Fatty acid elongase 6 |

| Δ9 fad |

Fatty acid desaturase 9 |

References

- Azarm, H.M.; Kenari, A.A.; Hedayati, M. Effect of dietary phospholipid sources and levels on growth performance, enzymes activity, cholecystokinin and lipoprotein fractions of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fry. Aquaculture Research 2013, 44, 634-644. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhao, N.; Zhao, A.; He, R. Effect of soybean phospholipid supplementation in formulated microdiets and live food on foregut and liver histological changes of Pelteobagrus fulvidraco larvae. Aquaculture 2008, 278, 119-127. [CrossRef]

- Vance, J. E. Phospholipid synthesis and transport in mammalian cells. Traffic 2015, 16, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Coutteau, P.; Geurden, I.; Camara, M.; Bergot, P.; Sorgeloos, P. Review on the dietary effects of phospholipids in fish and crustacean larviculture. Aquaculture 1997, 155, 149-164. [CrossRef]

- Council, N.R.; Earth, D.o.; Fish, C.o.t.N.R.o.; Shrimp. Nutrient requirements of fish and shrimp; National academies press 2011. [CrossRef]

- Hishikawa, D.; Shindou, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Nakanishi, H.; Taguchi, R.; Shimizu, T. Discovery of a lysophospholipid acyltransferase family essential for membrane asymmetry and diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 2830-2835. [CrossRef]

- Landman, M.J.; Codabaccus, B.M.; Carter, C.G.; Fitzgibbon, Q.P.; Smith, G.G. Is dietary phosphatidylcholine essential for juvenile slipper lobster (Thenus australiensis)? Aquaculture 2021, 542, 736889. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Qi, C.; Han, F.; Chen, X.; Qin, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Qin, J.; Chen, L. Selecting suitable phospholipid source for female Eriocheir sinensis in pre-reproductive phase. Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735610. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.T.; Valli, A.; Haider, S.; Zhang, Q.; Smethurst, E.A.; Schug, Z.T.; Peck, B.; Aboagye, E.O.; Critchlow, S.E.; Schulze, A. 3D growth of cancer cells elicits sensitivity to kinase inhibitors but not lipid metabolism modifiers. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2019, 18, 376-388. [CrossRef]

- Cornell, R.B.; Ridgway, N.D. CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase: Function, regulation, and structure of an amphitropic enzyme required for membrane biogenesis. Progress in lipid research 2015, 59, 147-171. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Schüpbach, T. Cct1, a phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis enzyme, is required for Drosophila oogenesis and ovarian morphogenesis. Development 2003. [CrossRef]

- Lykidis, A. Comparative genomics and evolution of eukaryotic phospholipid biosynthesis. Progress in lipid research 2007, 46, 171-199. [CrossRef]

- Oxley, A.; Torstensen, B.E.; Rustan, A.C.; Olsen, R.E. Enzyme activities of intestinal triacylglycerol and phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2005, 141, 77-87. [CrossRef]

- Tocher, D.R.; Bendiksen, E.Å.; Campbell, P.J.; Bell, J.G. The role of phospholipids in nutrition and metabolism of teleost fish. Aquaculture 2008, 280, 21-34. [CrossRef]

- Zhou L; Zhong L; Yuan J; Chen Y; Cao S; Liu J; Jiang K. Effects of Choline Chloride Supplementation in Feed on Growth, Feed Utilization, and Morphological Parameters of Largemouth Black Bass. Aquatic Science and Technology Information 2023, 50, 357-361. (Chinese journal with English abstract).

- An W; He H; Dong X; Tan B; Yang Q; Chi S; Liu H; Zhang S; Yang Y. Study on Choline Requirements of Litopenaeus vannamei Juveniles. Chinese Journal of Animal Nutrition 2019, 31, 4612-4621. (Chinese journal with English abstract).

- Siciliani, D.; Kortner, T.M.; Berge, G.M.; Hansen, A.K.; Krogdahl, Å. Effects of dietary lipid level and environmental temperature on lipid metabolism in the intestine and liver, and choline requirement in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L) parr. Journal of Nutritional Science 2023, 12, e61. [CrossRef]

- Zhang D; Li J; Wang B; Li X; Jiang G; Li P; Cai W; Liu W. Effects of Choline on Antioxidant Capacity, Tissue Structure, and Immunity in the Liver of Grass Carp Under High-Fat Dietary Stress. Acta Aquaticus Sinicus 2017, 41. (Chinese journal with English abstract).

- Huang, M.; Lin, H.; Xu, C.; Yu, Q.; Wang, X.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L.; Han, F.; Li, E. Growth, metabolite, antioxidative capacity, transcriptome, and the metabolome response to dietary choline chloride in Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Animals 2020, 10, 2246. [CrossRef]

- Xu X; Wu Z; Bao M; Wang H; Niu H; Chang J. Physiological functions of choline and its regulatory mechanisms on fish fat metabolism. Feed Research 2023, 46. (Chinese journal with English abstract).

- Lu, J.; Tao, X.; Luo, J.; Zhu, T.; Jiao, L.; Jin, M.; Zhou, Q. Dietary choline promotes growth, antioxidant capacity and immune response by modulating p38MAPK/p53 signaling pathways of juvenile Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Fish & Shellfish Immunology 2022, 131, 827-837. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Jiang, W.-D.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.-A.; Zhou, X.-Q.; Feng, L. Dietary choline deficiency and excess induced intestinal inflammation and alteration of intestinal tight junction protein transcription potentially by modulating NF-κB, STAT and p38 MAPK signaling molecules in juvenile Jian carp. Fish & shellfish immunology 2016, 58, 462-473. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.P.; Poe, W.E. Choline nutrition of fingerling channel catfish. Aquaculture 1988, 68, 65-71. [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Yang, P.; Chen, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, X.; He, C.; Mai, K.; Song, F. Dietary choline can partially spare methionine to improve the feeds utilization and immune response in juvenile largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides): Based on phenotypic response to gene expression. Aquaculture Reports 2023, 30, 101546. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tao, N.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Qiu, W.; Ma, M. Comparison of flavour qualities of three sourced Eriocheir sinensis. Food chemistry 2016, 200, 24-31. [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Washington DC, USA 2005.

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome biology 2002, 3, research0034. 0031. [CrossRef]

- Yang D; Chen F; Ruan G. Effects of Choline Supplementation in Feed on Growth, Tissue Fat Content, and Digestive Enzyme Activity in Yellow Eels. Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica 2006, 30, 676-682. (Chinese journal with English abstract).

- Jiang, G.Z.; Wang, M.; Liu, W.B.; Li, G.F.; Qian, Y. Dietary choline requirement for juvenile blunt snout bream, Megalobrama amblycephala. Aquaculture Nutrition 2013, 19, 499-505. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Tontonoz, P. Phospholipid remodeling in physiology and disease. Annual review of physiology 2019, 81, 165-188. [CrossRef]

- Merkel, O.; Fido, M.; Mayr, J.A.; Prüger, H.; Raab, F.; Zandonella, G.; Kohlwein, S.D.; Paltauf, F. Characterization and function in vivo of two novel phospholipases B/lysophospholipases fromSaccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 28121-28127. [CrossRef]

- Petrovič, U.; Šribar, J.; Matis, M.; Anderluh, G.; Peter-Katalinić, J.; Križaj, I.; Gubenšek, F. Ammodytoxin, a secretory phospholipase A2, inhibits G2 cell-cycle arrest in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemical Journal 2005, 391, 383-388. [CrossRef]

- Zaremberg, V.; McMaster, C.R. Differential partitioning of lipids metabolized by separate yeast glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferases reveals that phospholipase D generation of phosphatidic acid mediates sensitivity to choline-containing lysolipids and drugs. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 39035-39044. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Yousefnia, S.; Forootan, F.S.; Peymani, M.; Ghaedi, K.; Esfahani, M.H.N. Diverse roles of fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs) in development and pathogenesis of cancers. Gene 2018, 676, 171-183. [CrossRef]

- Qi R; Huang J; Yang F; Huang Y. The Fatty Acid Transporter Family and Its Mediated Transmembrane Transport of Fatty Acids. Chinese Journal of Animal Nutrition 2013, 25, 905-911. (Chinese journal with English abstract).

- McKillop, I.H.; Girardi, C.A.; Thompson, K.J. Role of fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs) in cancer development and progression. Cellular signalling 2019, 62, 109336. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, A.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Acetylation control of cardiac fatty acid β-oxidation and energy metabolism in obesity, diabetes, and heart failure. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2016, 1862, 2211-2220. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Rahimnejad, S.; Lu, K.; Wang, L.; Liu, W. Effects of berberine on growth, liver histology, and expression of lipid-related genes in blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) fed high-fat diets. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry 2019, 45, 83-91. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Leray, V.; Diez, M.; Serisier, S.; Bloc’h, J.L.; Siliart, B.; Dumon, H. Liver lipid metabolism. Journal of animal physiology and animal nutrition 2008, 92, 272-283. [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.H.; Selivonchick, D.P. Lipid metabolism in fish. Progress in Lipid Research 1987, 26, 53-85. [CrossRef]

- Mai, K. Aquatic Animal Nutrition and Feed Science. China Agriculture Press, Beijing 2011.

- Halver, J.E.; Hardy, R.W. Fish nutrition. Academic press, California, USA 2002.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).