Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

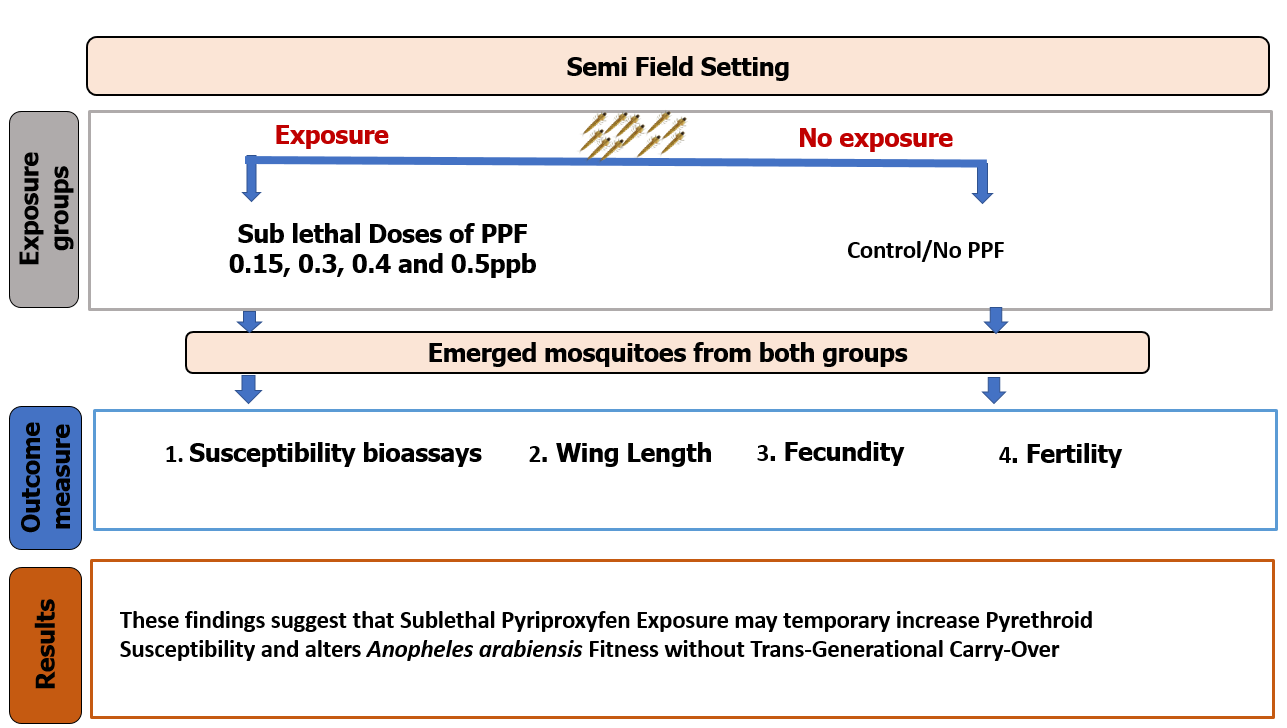

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Mosquito Rearing

2.3. Tested Insecticide

2.4. Treatments with Pyriproxyfen

2.5. Effect of Pyriproxyfen Exposure on Insecticide Susceptibility

2.6. Effect of Pyriproxyfen Exposure on Fitness Parameters

2.7. Statistical Analysis and Presentation

3. Results

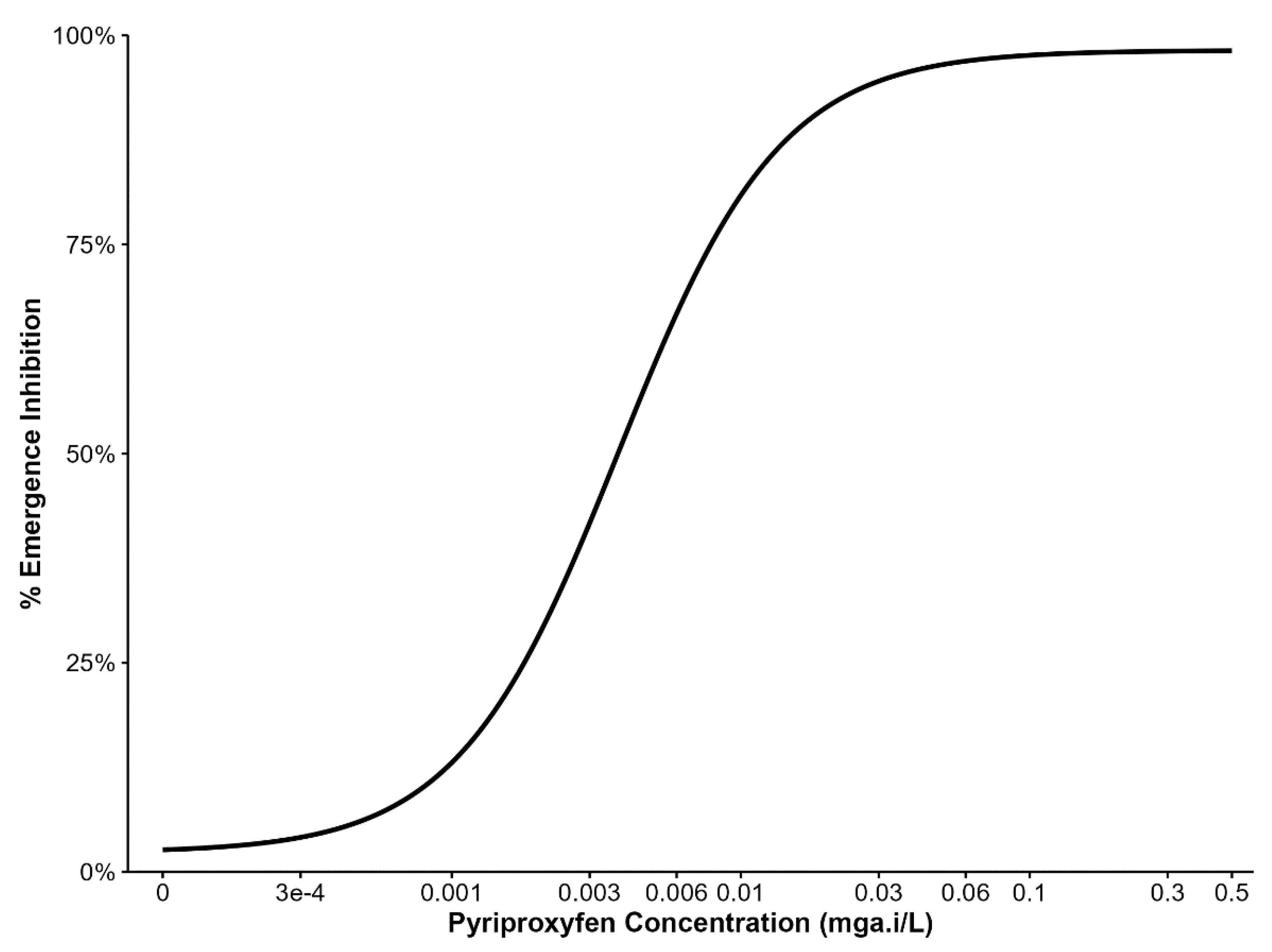

3.1. Initial Tests to Determine the Range of Sub-Lethal PPF Doses

3.2. Effect of Sub Lethal Dose of PPF on An. arabiensis Susceptibility to Pyrethroids

3.3. Effect of Sublethal Dose of Pyriproxyfen on Body Size, Fecundity, and Fertility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Authors’ contributions

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Data availability and materials

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

List of Abbreviations

| a.i | active ingredient |

| DHS- MIS | Demographic Health Survey Malaria Indicator Survey |

| GTS | Global Technical Strategy |

| IGR | Insecticide Growth Regulator |

| IVM | Integrated Vector Management |

| IRS | Indoor Residual Spray |

| LC | Lethal Concentration |

| LLINs | Long Lasting Insecticide Treated nets |

| LSM | Larval Source Management |

| NMSP | National Malaria Strategic Plan |

| PPF | Pyriproxyfen |

| SFS | Semi Field System |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- WHO. “Interim Position Statement” The role of larviciding for malaria control in sub-Saharan Africa [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/337991/WHO-HTM-GMP-2012.06-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- WHO. World malaria report 2024 [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024.

- TDHS-MIS. TDHS -MIS, 2022 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR382-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm.

- Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, Bisanzio D, Mappin B, Dalrymple U, et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature [Internet]. 2015 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Jul 24]; 526:207–11. Available from: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2015Natur.526.207B. [CrossRef]

- Kisinza WN, Nkya TE, Kabula B, Overgaard HJ, Massue DJ, Mageni Z, et al. Multiple insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae from Tanzania: a major concern for malaria vector control. Malar J [Internet]. 2017 Oct 30 [cited 2023 Jul 24]; 16:439. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5663032/. [CrossRef]

- CDC. Malaria. 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 20]. Larval Source Management and Other Vector Control Interventions. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/php/public-health-strategy/larval-management.html.

- Choi L, Wilson A. Larviciding to control malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2017 Jul 25 [cited 2023 Jul 24];2017(7):CD012736. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6483557/. [CrossRef]

- Devine GJ, Killeen GF. The potential of a new larviciding method for the control of malaria vectors. Malar J. 2010 May 25; 9:142. [CrossRef]

- Newby G, Chaki P, Latham M, Marrenjo D, Ochomo E, Nimmo D, et al. Larviciding for malaria control and elimination in Africa. Malar J. 2025 Jan 15;24(1):16. [CrossRef]

- Okumu F, Moore SJ, Selvaraj P, Yafin AH, Juma EO, Shirima GG, et al. Elevating larval source management as a key strategy for controlling malaria and other vector-borne diseases in Africa. Parasit Vectors. 2025 Feb 7;18(1):45.

- Mmbaga A, Lwetoijera D. Current and future opportunities of autodissemination of pyriproxyfen approach for malaria vector control in urban and rural Africa - PubMed [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Nov 6]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37440995/.

- Stanton MC, Kalonde P, Zembere K, Hoek Spaans R, Jones CM. The application of drones for mosquito larval habitat identification in rural environments: a practical approach for malaria control? Malar J [Internet]. 2021 Dec [cited 2023 Jul 28];20(1):244. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-021-03759-2.

- Fillinger U, Lindsay SW. Suppression of exposure to malaria vectors by an order of magnitude using microbial larvicides in rural Kenya. Trop Med Int Health TM IH. 2006 Nov;11(11):1629–42. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Escobar G, Manrique E, Ruiz-Cabrejos J, Saavedra M, Alava F, Bickersmith S, et al. High-accuracy detection of malaria vector larval habitats using drone-based multispectral imagery. Costantini C, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019 Jan 17;13(1): e0007105.

- Devine GJ, Perea EZ, Killeen GF, Stancil JD, Clark SJ, Morrison AC. Using adult mosquitoes to transfer insecticides to Aedes aegypti larval habitats. Proc Natl Acad Sci [Internet]. 2009 Jul 14 [cited 2023 Jul 28];106(28):11530–4. Available from: https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0901369106.

- Lwetoijera D, Kiware S, Okumu F, Devine GJ, Majambere S. Autodissemination of pyriproxyfen suppresses stable populations of Anopheles arabiensis under semi-controlled settings. Malar J. 2019 May 9;18(1):166. [CrossRef]

- Chandel K, Suman DS, Wang Y, Unlu I, Williges E, Williams GM, et al. Targeting a Hidden Enemy: Pyriproxyfen Autodissemination Strategy for the Control of the Container Mosquito Aedes albopictus in Cryptic Habitats. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2016 Dec 29 [cited 2023 Jul 28];10(12): e0005235. Available from: https://www.researchwithrutgers.com/en/publications/targeting-a-hidden-enemy-pyriproxyfen-autodissemination-strategy-.

- McKemey A, Adey R. Autodissemination of insecticides for mosquito control. Review of current R&D status, and feasibility for widespread operational adoption. 2018 Aug;

- Lupenza ET, Kihonda J, Limwagu AJ, Ngowo HS, Sumaye RD, Lwetoijera DW. Using pastoralist community knowledge to locate and treat dry-season mosquito breeding habitats with pyriproxyfen to control Anopheles gambiae s.l. and Anopheles funestus s.l. in rural Tanzania. Parasitol Res. 2021 Apr;120(4):1193–202.

- Lwetoijera D, Harris C, Kiware S, Dongus S, Devine GJ, McCall PJ, et al. Effective autodissemination of pyriproxyfen to breeding sites by the exophilic malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis in semi-field settings in Tanzania. Malar J. 2014 Apr 29; 13:161.

- Dhadialla TS, Carlson GR, Le DP. New insecticides with ecdysteroidal and juvenile hormone activity. Annu Rev Entomol. 1998; 43:545–69.

- Yunta C, Grisales N, Nász S, Hemmings K, Pignatelli P, Voice M, et al. Pyriproxyfen is metabolized by P450s associated with pyrethroid resistance in An. gambiae. Insect Biochem Mol Biol [Internet]. 2016 Nov [cited 2023 Jul 28]; 78:50–7. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0965174816301278.

- Opiyo MA, Ngowo HS, Mapua SA, Mpingwa M, Nchimbi N, Matowo NS, et al. Sub-lethal aquatic doses of pyriproxyfen may increase pyrethroid resistance in malaria mosquitoes. PloS One. 2021;16(3): e0248538. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson HM, Ng’habi KR, Walder T, Kadungula D, Moore SJ, Lyimo I, et al. Establishment of a large semi-field system for experimental study of African malaria vector ecology and control in Tanzania. Malar J. 2008;7(158).

- Ngowo HS, Hape EE, Matthiopoulos J, Ferguson HM, Okumu FO. Fitness characteristics of the malaria vector Anopheles funestus during an attempted laboratory colonization. Malar J. 2021 Mar 12;20(1):148.

- Betwel et al, Changes in contributions of different Anopheles vector species to malaria transmission in east and southern Africa from 2000 to 2022 | Parasites & Vectors | Full Text [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 18]. Available from: https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-023-06019-1.

- WHO. WHO (2005) Guidelines for Laboratory and Field Testing of Mosquito Larvicides. World Health Organization, Geneva, WHO/CDS/WHOPES/GCDPP/200513. - References - Scientific Research Publishing [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2025 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3433421.

- Nasci RS. Relationship of wing length to adult dry weight in several mosquito species (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 1990 Jul;27(4):716–9. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/.

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker [aut B, cre, Walker S, Christensen RHB, et al. lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models using “Eigen” and S4 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/index.html.

- Kunambi HJ, Ngowo H, Ali A, Urio N, Ngonzi AJ, Mwalugelo YA, et al. Sterilized Anopheles funestus can autodisseminate sufficient pyriproxyfen to the breeding habitat under semi-field settings. Malar J. 2023 Sep 21;22(1):280. [CrossRef]

- Lwetoijera D, Harris C, Kiware S, Dongus S, Devine GJ, McCall PJ, et al. Effective autodissemination of pyriproxyfen to breeding sites by the exophilic malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis in semi-field settings in Tanzania. Malar J. 2014 Apr 29; 13:161.

- Ahmed TH, Saunders TR, Mullins D, Rahman MZ, Zhu J. Molecular action of pyriproxyfen: Role of the Methoprene-tolerant protein in the pyriproxyfen-induced sterilization of adult female mosquitoes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020 Aug 31;14(8): e0008669. [CrossRef]

- Harburguer L, Zerba E, Licastro S. Sublethal Effect of Pyriproxyfen Released from a Fumigant Formulation on Fecundity, Fertility, and Ovicidal Action in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2014 Mar 1;51(2):436–43.

- Brogdon WG, McAllister JC, Corwin AM, Cordon-Rosales C. Independent selection of multiple mechanisms for pyrethroid resistance in Guatemalan Anopheles albimanus (Diptera: Culicidae). J Econ Entomol. 1999 Apr;92(2):298–302.

- Fine BC, Godin PJ, Thain EM. Penetration of Pyrethrin I labelled with Carbon-14 into Susceptible and Pyrethroid Resistant Houseflies. Nature. 1963 Aug;199(4896):927–8.

- Karatolos N, Williamson MS, Denholm I, Gorman K, Ffrench-Constant RH, Bass C. Over-expression of a cytochrome P450 is associated with resistance to pyriproxyfen in the greenhouse whitefly Trialeurodes vaporariorum. PloS One. 2012;7(2):e31077. [CrossRef]

- Lilly DG, Latham SL, Webb CE, Doggett SL. Cuticle Thickening in a Pyrethroid-Resistant Strain of the Common Bed Bug, Cimex lectularius L. (Hemiptera: Cimicidae). PloS One. 2016;11(4):e0153302.

- Ngufor C, N’Guessan R, Fagbohoun J, Odjo A, Malone D, Akogbeto M, et al. Olyset Duo® (a pyriproxyfen and permethrin mixture net): An experimental hut trial against pyrethroid resistant Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus in southern Benin. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4). [CrossRef]

- Shah RM, Abbas N, Shad SA, Varloud M. Inheritance mode, cross-resistance and realized heritability of pyriproxyfen resistance in a field strain of Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae). Acta Trop. 2015 Feb 1; 142:149–55.

- Shayo et al, F. Exposure of malaria vector larval habitats to domestic pollutants escalate insecticides resistance: experimental proof | International Journal of Tropical Insect Science [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 4]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42690-020-00123-w.

- Shilla DJ, Matiya DJ, Nyamandito NL, Tambwe MM, Quilliam RS. Insecticide tolerance of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae following larval exposure to microplastics and insecticide. PloS One. 2024;19(12): e0315042.

- Fournet F, Sannier C, Monteny N. Effects of the insect growth regulators OMS 2017 and diflubenzuron on the reproductive potential of Aedes aegypti. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1993 Dec;9(4):426–30.

- Harris C, Lwetoijera DW, Dongus S, Matowo NS, Lorenz LM, Devine GJ, et al. Sterilising effects of pyriproxyfen on Anopheles arabiensis and its potential use in malaria control. 2013;1–8.

- Itoh T, Kawada H, Abe A, Eshita Y, Rongsriyam Y, Igarashi A. Utilization of bloodfed females of Aedes aegypti as a vehicle for the transfer of the insect growth regulator pyriproxyfen to larval habitats. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1994 Sep;10(3):344–7.

- Juliano SA, Ribeiro GS, Maciel-de-Freitas R, Castro MG, Codeço C, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, et al. She’s a femme fatale: low-density larval development produces good disease vectors. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014 Dec;109(8):1070–7. [CrossRef]

- Koama B, Namountougou M, Sanou R, Ndo S, Ouattara A, Dabiré RK, et al. The sterilizing effect of pyriproxyfen on the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae: physiological impact on ovaries development. Malar J. 2015 Mar 4; 14:101.

- Moura L, De Nadai BL, Corbi JJ. What does not kill it does not always make it stronger: High temperatures in pyriproxyfen treatments produce Aedes aegypti adults with reduced longevity and smaller females. J Asia-Pac Entomol. 2020 Jun;23(2):529–35. [CrossRef]

- Tunaz H, Uygun N. Insect Growth Regulators for Insect Pest Control*. Turk J Agric for. 2004 Jan 1;28(6):377–87.

- Koffi A, Ahoua Alou L, Djenontin A, Kabran JP, Dosso Y, Kone A, et al. Efficacy of Olyset ® Duo, a permethrin and pyriproxyfen mixture net against wild pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles gambiae s.s. from Côte d’Ivoire: an experimental hut trial. Parasite. 2015 Oct; 22:28.

- Mosha JF, Kulkarni MA, Lukole E, Matowo NS, Pitt C, Messenger LA, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness against malaria of three types of dual-active-ingredient long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) compared with pyrethroid-only LLINs in Tanzania: a four-arm, cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet. 2022 Mar 26;399(10331):1227–41. [CrossRef]

- Lushasi SC, Mwalugelo YA, Swai JK, Mmbando AS, Muyaga LL, Nyolobi NK, et al. The Interspecific Competition Between Larvae of Aedes aegypti and Major African Malaria Vectors in a Semi-Field System in Tanzania. Insects. 2024 Dec 31;16(1):34. [CrossRef]

| Insecticides | Generations |

PPF conc. (mg a.i/L) |

OR [95% CI] |

Mean Mortality (%) ± SD |

Pvalue | Susceptibility status | ||

| Permethrin | 1 | No PPF | 1 | 22.67 ± 3.11 | – | R | ||

| 0.001 |

0.66 (0.52 – 0.82) | 3 ± 2.49 | P < 0.001 | R | ||||

| 0.0003 | 0.77 (0.60 – 0.97) | 11 ± 4.86 | 0.026 | R |

||||

| 2 | No PPF | 1 | 22.67 ± 3.94 | – | R | |||

| 0.001 | 0.99 (0.79 – 1.25) | 23 ± 3.86 | 0.953 | R | ||||

| 0.0003 | 0.97 (0.77 – 1.23) | 22 ± 3.19 | 0.813 | R |

||||

| 3 | No PPF | 1 | 25 ± 4.22 | – | R | |||

| 0.001 | 1.05 (0.83 – 1.33) | 24.67 ± 4.77 | 0.694 | R | ||||

| 0.0003 | 1.01 (0.80 – 1.27) | 22.67 ± 4.29 | 0.953 | R |

||||

| Deltamethrin | 1 | No PPF | 1 | 62.67 ± 5.99 | – | R | ||

| 0.001 | 0.18 (0.13 – 0.26) | 23.33 ± 7.78 | P < 0.001 | R | ||||

| 0.0003 | 0.34 (0.24 – 0.47) | 36 ± 11.05 | P < 0.001 | R |

||||

| 2 | No PPF | 1 | 60.33 ± 7.33 | – | R | |||

| 0.001 | 0.99 (0.71 – 1.37) | 60 ± 14.77 | 0.933 | R | ||||

| 0.0003 | 0.92 (0.66 – 1.28) | 58.33 ± 3.98 | 0.617 | R |

||||

| 3 | No PPF | 1 | 62 ± 6.27 | – | R | |||

| 0.001 | 0.89 (0.64 – 1.24) | 61.33 ± 6.23 | 0.867 | R | ||||

| 0.0003 | 0.97 (0.70 – 1.35) | 59.33 ± 9.16 | 0.504 | R | ||||

| Insecticides | Generations |

PPF conc. (mg a.i/L) |

KDT60 (min) (%) ± SD |

OR [95% CI] | Pvalue | ||

| Permethrin | 1 | No PPF | 41.3 ± 7.9 | 1 | – | ||

| 0.001 | 3.3 ± 2.3 |

0.44 (0.35 – 0.56) | P < 0.001 | ||||

| 0.0003 | 9.3 ± 4.3 |

0.50 (0.39 – 0.64) | P < 0.001 | ||||

| 2 | No PPF | 27.3 ± 6.8 | 1 | – | |||

| 0.001 | 30 ± 7.1 | 1.03 (0.81 – 1.30) | 0.810 | ||||

| 0.0003 | 27.7 ± 8.6 |

1.01 (0.80 – 1.27) | 0.952 | ||||

| 3 | No PPF | 27.3 ± 8.3 | 1 | – | |||

| 0.001 | 29 ± 6.8 | 1.01 (0.80 – 1.29) | 0.904 | ||||

| 0.0003 | 31 ± 4.6. |

1.06 (0.84 – 1.34) | 0.629 | ||||

| Deltamethrin | 1 | No PPF | 79.7 ± 6.9 | 1 | – | ||

| 0.001 | 65 ± 3.5 | 0.47 (0.33 – 0.68) | P < 0.001 | ||||

| 0.0003 | 66.7 ± 4.9 | 0.51 (0.35 – 0.74) | P < 0.001 |

||||

| 2 | No PPF | 77.3± 6.5 | 1 | – | |||

| 0.001 | 74 ± 4 | 0.83 (0.57 – 1.61) | 0.342 | ||||

| 0.0003 | 75.3 ± 4.1 | 0.90 (0.61 – 1.30) | 0.565 |

||||

| 3 | No PPF | 78.7 ± 6.2 | 1 | – | |||

| 0.001 | 75.7 ± 3.3 | 0.89 (0.61 – 1.31) | 0.557 | ||||

| 0.0003 | 77.7 ± 7.3 | 0.94 (0.64 – 1.39) | 0.767 | ||||

| Generations | PPF Concentrations |

Predicted Mean [95% CI] (mm)* |

Estimate [95% CI] | P value | |

| (mg a.i/L) | |||||

| 1 | Control | 3.07 (2.99 – 3.15) | 1 | – | |

| 0.0003 | 2.88 (2.88 – 2.80) | 0.94 (0.90 – 0.98) | 0.004 | ||

| 0.0006 | 2.82 (2.74 – 2.90) | 0.92 (0.88 – 0.96) | P < 0.001 | ||

| 0.0008 | 2.77 (2.69 – 2.85) | 0.90 (0.86 – 0.95) | P < 0.001 | ||

| 0.001 | 2.66 (2.58 – 2.74) | 0.87 (0.87 – 0.91) | P < 0.001 | ||

| 2 | Control | 3.06 (2.98 – 3.14) | 1 | – | |

| 0.0003 | 3.05 (2.97 – 3.13) | 0.97 (0.93 – 1.01) | 0.098 | ||

| 0.0006 | 2.98 (2.90– 3.06) | 0.97 (0.94 -1.01) | 0.157 | ||

| 0.0008 | 3.05 (2.97 – 3.13) | 1.00 (0.96 – 1.04) | 0.9 07 | ||

| 0.001 | 2.99 (2.91– 3.07) | 0.98 (0.94 -1.01) | 0.216 | ||

| 3 | Control | 3.08 (3.00 – 3.16) | 1 | – | |

| 0.0003 | 3.02 (2.94 – 3.10) | 0.98 (0.95 – 0.01) | 0.235 | ||

| 0.0006 | 3.02 (2.94 – 3.10 | 0.98 (0.95 – 0.01) | 0.210 | ||

| 0.0008 | 3.04 (2.96 – 3.12) | 0.99 (0.96 – 0.02) | 0.470 | ||

| 0.001 | 3.01 (2.93 – 3.09) | 0.98 (0.95 – 0.01) | 0.187 |

| Generations | PPF concentrations. | Predicted Mean [95% CI]* | RR [95% CI] | P value | |

| ( mg a.i/l ) | |||||

| 1 | Control | 30.07 (28.17 – 32.09) | 1 | – | |

| 0.0003 | 18.83 (17.34 – 20.45) | 0.63 (0.56 – 0.70) | P < 0.001 | ||

| 0.0006 | 17.80 (16.35 – 19.38) | 0.59 (0.53 – 0.66) | P < 0.001 | ||

| 0.0008 | 14.93 (13.61 – 16.38) | 0.50 (0.44 – 0.56) | P < 0.001 | ||

| 0.001 | 13.90 (12.63 – 15.30) | 0.46 (0.41– 0.52) | P < 0.001 | ||

| 2 | Control | 30.13 (28.23 – 32.16) | 1 | – | |

| 0.0003 | 30.47 (28.55 – 32.51) | 1.01 (0.92 – 1.11) | 0.815 | ||

| 0.0006 | 28.77 (26.91 – 30.75) | 0.95 (0.87 – 1.05) | 0.329 | ||

| 0.0008 | 28.83 (26.97 – 30.82) | 0.96 (0.87 – 1.05) | 0.354 | ||

| 0.001 | 28.00 (26.17 – 29.96) | 0.93 (0.85 – 1.02) | 0.125 | ||

| 3 | Control | 30.67 (28.75 – 32.71) | 1 | – | |

| 0.0003 | 31.23 (29.30 – 33.30) | 1.02 (0.93 – 1.12) | 0.693 | ||

| 0.0006 | 30.80 (28.88 – 32.85) | 1.00 (0.92 – 1.10) | 0.926 | ||

| 0.0008 | 30.00 (28.10 – 32.03) | 0.98 (0.89 – 1.07) | 0.639 | ||

| 0.001 | 29.90 (28.01 – 31.92) | 0.97 (0.89 – 1.07) | 0.590 |

| Generations | PPF concentrations. | Predicted Mean Proportion [95% CI]* | OR [95% CI] | P value | |

| (mg a.i/l) | |||||

| 1 | Control | 0.87 (0.85 – 0.89) | 1 | – | |

| 0.0003 | 0.82 (0.79 – 0.85) | 0.66 (0.49 – 0.88) | 0.005 | ||

| 0.0006 | 0.82 (0.78– 0.85) | 0.64 (0.48 – 0.86) | 0.003 | ||

| 0.0008 | 0.79 (0.75 – 0.82) | 0.54 (0.40 – 0.73) | 0.001 | ||

| 0.001 | 0.79 (0.75 – 0.83) | 0.55 (0.40– 0.75) | 0.001 | ||

| 2 | Control | 0.88 (0.86– 0.90) | 1 | – | |

| 0.0003 | 0.89 (0.86– 0.89) | 1.01 (0.76 – 1.35) | 0.932 | ||

| 0.0006 | 0.89 (0.86– 0.89) | 1.01 (0.76 – 1.36) | 0.925 | ||

| 0.0008 | 0.89 (0.87 – 0.91) | 1.09 (0.81 – 1.47) | 0.565 | ||

| 0.001 | 0.88 (0.85 – 0.90) | 1.15 (0.55 – 1.86) | 0.358 | ||

| 3 | Control | 0.88 (0.86 – 0.90) | 1 | – | |

| 0.0003 | 0. 87 (0.85 – 0.89) | 0.92 (0.97 – 1.22) | 0.574 | ||

| 0.0006 | 0.89 (0.87 – 0.91) | 1.06 (0.80 – 1.41) | 0.690 | ||

| 0.0008 | 0.88 (0.86 – 0.90) | 0.97 (073 – 1.28) | 0.807 | ||

| 0.001 | 0.88 (0.85 – 0.90) | 0.94 (0.71 – 1.25) | 0.677 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).