Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. AI Peer Review: From Smart Assistants to Autonomous Referees

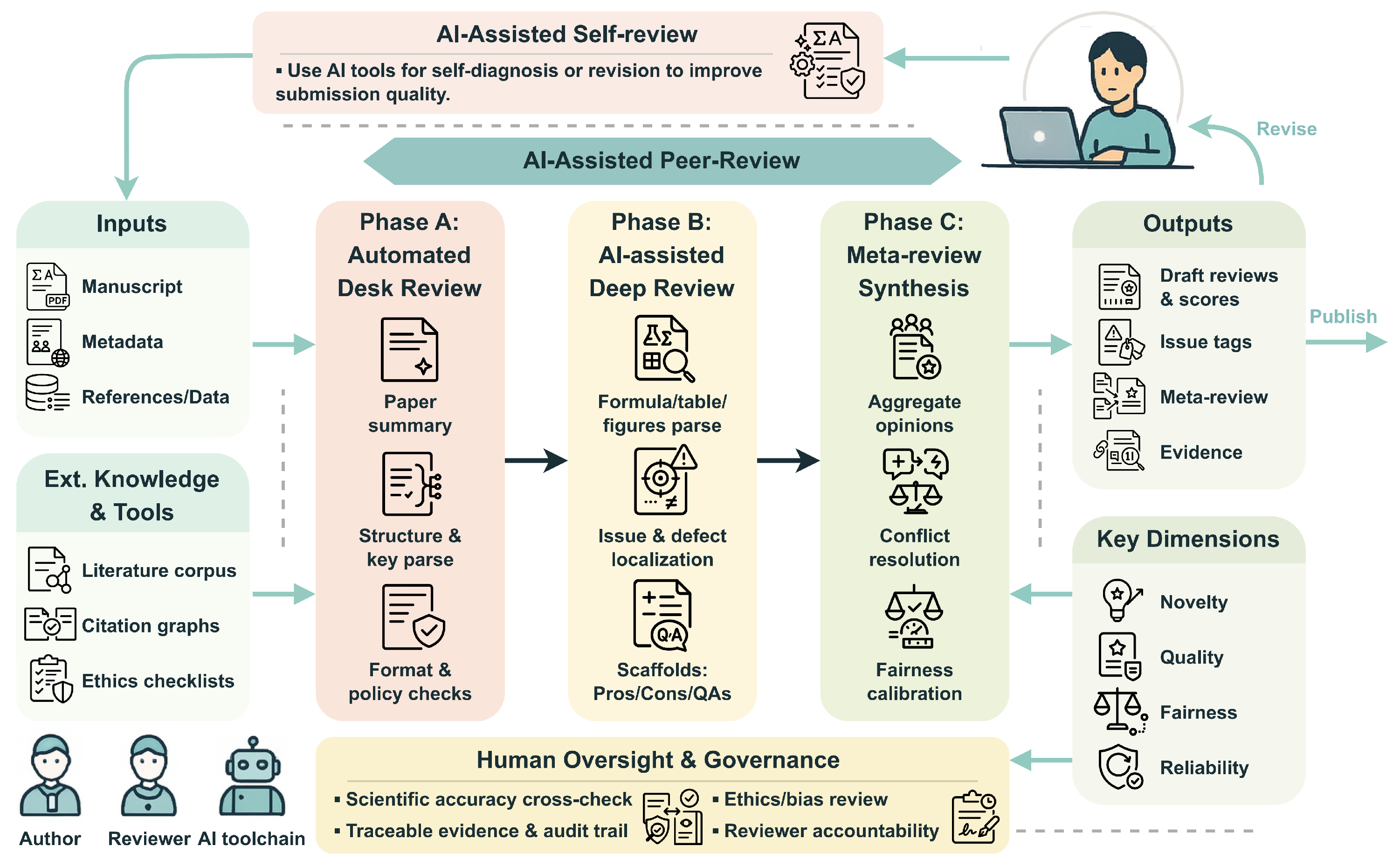

2.1.1. Automated Desk Review

2.1.2. AI-Assisted Deep Review

2.1.3. Meta-Review Synthesis

2.2. Adversarial Roots: Lessons from Attacks in AI Systems

2.2.1. Categories and Mechanisms of Adversarial Attacks

- •

- Evasion Attacks. As the most studied type of attack, attackers often embed slight perturbations into legitimate inputs at test time to induce errors (Biggio et al. 2013). The resulting “adversarial examples” look benign to humans but cause misclassification (Carlini and Wagner 2016). For example, a face-recognition system may misidentify a person wearing specially designed glasses or small stickers. Based on the attacker’s knowledge of the model, evasion attacks can be divided into two types: white-box and black-box. In the white-box setting, the attacker fully understands the model’s structure and gradient information, enabling efficient perturbation methods (Goodfellow et al. 2014; Madry et al. 2017; Papernot et al. 2015). A classic white-box illustration involves adding subtle perturbations to handwritten digit images: a human still sees a `3’, but the digit-recognition model confidently classifies it as an `8’. In the black-box setting, only queries and outputs are available to the attacker (Chen et al. 2017; Ilyas et al. 2018; Papernot et al. 2016). This process is similar to repeatedly trying combinations on a lock without knowing its mechanism, learning from each attempt until it opens.

- •

- Exploratory Attacks. Rather than directly intervening in model training or inference, the attacker can probe a deployed model to infer internal confidential information or privacy features of the training data (Papernot et al. 2018) through repeated interactions. Model inversion is a typical technique that reconstructs sensitive information from training data by reversing model outputs. Researchers have shown that a model trained on facial data can recover recognizable images of individuals from only partial outputs (Fredrikson et al. 2015). Another influential line of work is membership inference attack, which determines whether a specific record is included in a model’s training set. This capability poses a threat to systems handling sensitive information, such as revealing whether a particular patient’s or customer’s record is included in the medical or financial data used for model training (Shokri et al. 2016). This action potentially exposes private health conditions or financial behaviors, enabling discrimination or targeted scams against those individuals. In particular, model extraction attacks can steal and replicate the structure and parameters of a target model through large-scale input-output queries. Tramer et al. (2016) demonstrates that repeatedly querying commercial APIs allows an attacker to reconstruct a local model that mimics the proprietary service. Moreover, attribute inference attacks can uncover private, unlabeled attributes in training samples, such as gender, accent, or user preferences (Yeom et al. 2017).

- •

- Poisoning Attacks. Poisoning attacks tamper with training data to degrade accuracy, bias decisions, or implant backdoors (Biggio et al. 2012; Tolpegin et al. 2020). For example, attackers may insert fake purchase records into a recommendation system, leading the model to incorrectly promote specific products as popular. Poisoning attacks can take various forms. Backdoor attacks train models to behave normally but misfire when a secret trigger appears, allowing an attacker to control their output under certain conditions (Chen et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2017). For instance, imagine training a workplace-security system to correctly classify everyone wearing a black badge as a technician and everyone wearing a white badge as a manager. A hidden backdoor can then cause the system to misclassify any technician wearing a white badge as a manager. Other forms include directly injecting fabricated data or modifying the labels of existing samples, making the model learn the wrong associations (Shafahi et al. 2018). Attackers can also create poisoned samples that appear normal to humans yet mislead the model. Alternatively, they subtly alter hidden features and labels, making the manipulation nearly invisible (Zhang et al. 2021). All these methods share a common consequence: they contaminate the model’s core knowledge. For instance, adding perturbations to pedestrian images during training may cause the model to incorrectly identify pedestrians, leading to collisions for autonomous vehicles. Since these attacks contaminate the model’s source, their malicious effects often remain hidden until specific triggers are activated, granting them extreme stealthiness.

2.2.2. Defense Mechanisms and Techniques

- •

- Proactive Defenses. These defenses strengthen intrinsic robustness during model design or training rather than waiting to respond once an attack occurs. Their primary goal is to build immunity before the attack happens. For instance, Tramer et al. (2017) and Madry et al. (2017) train models with deliberately crafted “tricky examples,” which help the model recognize and ignore subtle manipulations. The process is similar to how teachers give students difficult practice questions so they can handle real exams. Cohen et al. (2019) introduces controlled randomness, which makes it harder for attackers to exploit patterns. This technique is like occasionally changing game rules so players rely on general strategies rather than memorization. In addition, Wu et al. (2020) incorporates broader prior knowledge, akin to students reading widely to avoid being misled by a single tricky question. These proactive measures equip the model with internal safeguards, enabling it to withstand unexpected attacks better.

- •

- Passive Defenses. These defenses add detectors and sanitizers around the model and data pipeline, aiming to identify potential adversarial examples or anomalous data (Chen et al. 2020). For example, Metzen et al. (2017) monitors internal signals to identify abnormal inputs. This helps the system catch potentially harmful manipulations before they affect outputs, much like airport scanners catching suspicious items in luggage. Data auditing screens training sets for poisoning or outliers before learning proceeds (Steinhardt et al. 2017). This allows the model to avoid learning from malicious inputs, similar to inspecting ingredients before cooking to prevent contamination. In text-based systems, Piet et al. (2024) designs a framework to generate task-specific models that are immune to prompt injection. This helps the system ignore malicious instructions, akin to carefully reviewing messages to prevent phishing attempts. By adding these safeguards around the model, passive defenses act as checkpoints that intercept attacks in real time, reducing the risk of damage.

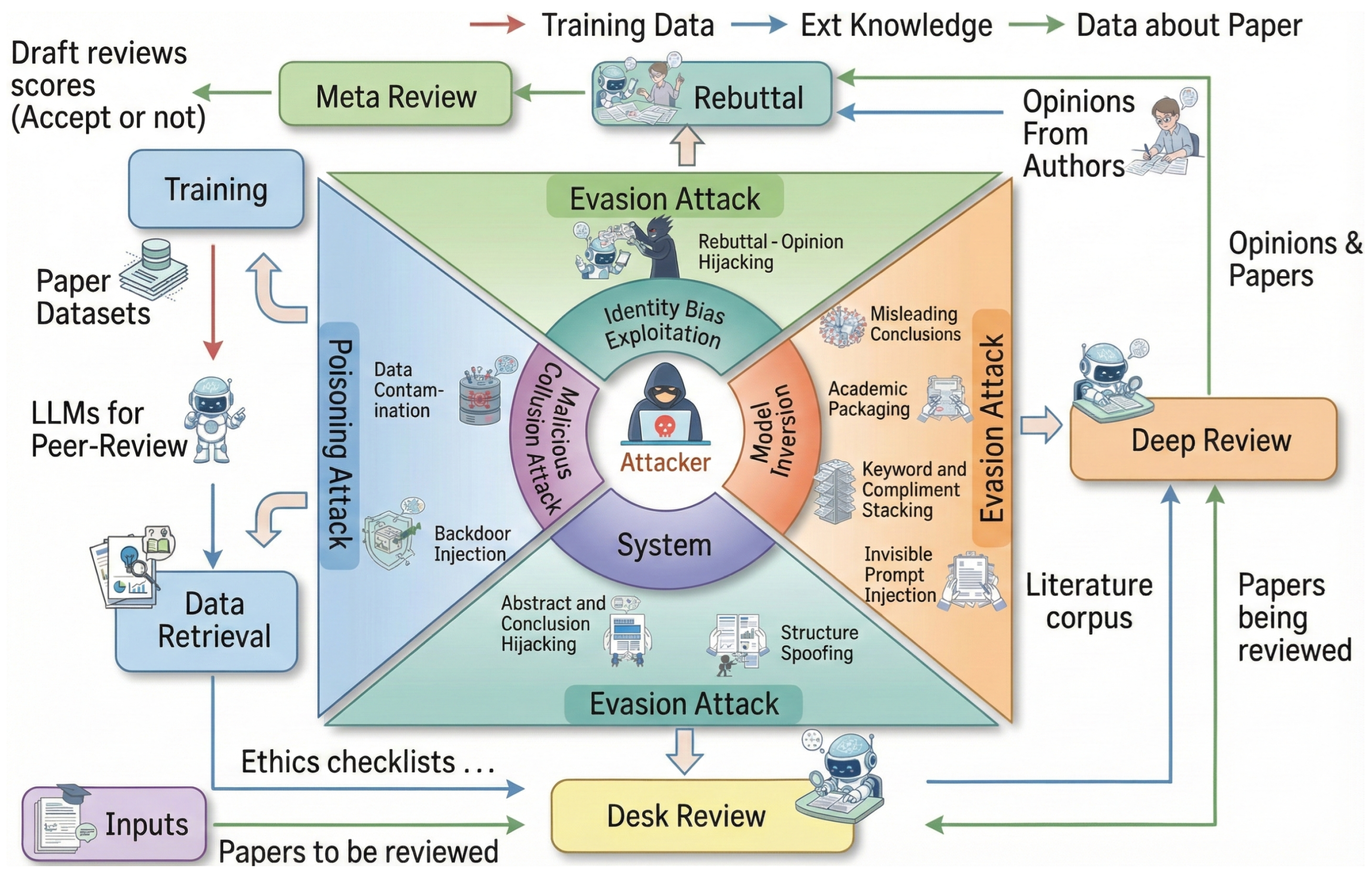

3. Breaking the Referee: Attacks on Automated Academic Review

3.1. Where Can the Referee Be Fooled?

- Training and Data Retrieval.

- Desk Review.

- Deep Review.

- Rebuttal.

- System-wide Vulnerabilities.

3.2. How to Break the Referee?

3.2.1. Attacks During the Training and Data Retrieval Phase

- Backdoor Injection. The attackers might introduce a backdoor to covertly influence the AI referee’s judgments. They embed subtle triggers in public documents, such as scientific preprints or published articles (Touvron et al. 2023). So that a model trained on this corpus learns to associate the trigger with a particular response. For example, a faint noise pattern added to figures may cause the AI referee to score submissions containing that pattern more favorably (Bowen et al. 2025). Because these triggers are inconspicuous, they often evade detection, and their influence can persist (Liu et al. 2024). When deployed on a scale, these backdoors could be easily used to inflate scores for an attacker’s subsequent submissions, seriously compromising the fairness of the review (Zhu et al. 2025).

- Data Contamination. This approach pollutes the training corpus used to build the AI referee (Tian et al. 2022; Zhao et al. 2025). An attacker could flood the training set with low-quality papers. This measure would compromise the AI referee’s capability to differentiate between high-impact and low-impact research. Although resource-intensive, this attack is exceptionally stealthy: individually, poisoned documents may appear harmless, but collectively they lower quality standards. In fact, even a small number of strategically designed papers may systematically skew referee assessments (Muñoz-González et al. 2017), inducing lasting changes in the AI referee’s internal representations of scientific quality and creating cascading errors in future evaluations (Zhang et al. 2024). Over time, such accumulated bias may cause the system to favor certain submission types, undermining the integrity of scientific gatekeeping.

3.2.2. Attack Analysis in the Desk Review Phase

- Abstract and Conclusion Hijacking. This attack leverages the AI referee’s tendency to overweight high-visibility sections. Attackers craft abstracts and conclusions that exaggerate claims and inflate contributions, thereby misrepresenting the core technical content. By using persuasive rhetoric in these sections, they may anchor the AI’s initial assessment on a favorable premise before methods and evidence are scrutinized (Nourani et al. 2021), biasing the downstream evaluation.

- Structure Spoofing. This strategy creates an illusion of rigor by meticulously mimicking the architecture of a high-impact paper. Attackers design the paper’s structure, from section headings to formatting, to project an image of completeness and professionalism, regardless of the quality of the underlying content. This attack targets pattern-matching heuristics in automated systems, which are trained to associate sophisticated structure with high-quality science. This allows weak submissions to pass automated gates as structural polish is mistaken for scientific merit (Shi et al. 2023).

3.2.3. Attack Analysis in the Deep Review Phase

- Academic Packaging. This attack creates a facade of academic depth by injecting extensive mathematics, intricate diagrams, and dense jargon. This technique exploits the “verbosity bias” found in LLMs, which may mistake complexity for rigor (Ye et al. 2024). Specifically, by adding sophisticated but potentially irrelevant equations or algorithmic pseudo code, attackers create a veneer of technical novelty that may mislead automated assessment tools (Lin et al. 2025), especially in specialized domains (Lin et al. 2025).

- Keyword and Praise Stacking. This technique games the AI’s scoring mechanism by saturating the manuscript with high-impact keywords and superlative claims. Attackers strategically embed terms such as “groundbreaking” or “novel breakthrough”, along with popular buzzwords from the target field, to artificially inflate the perceived importance of the article (Shi et al. 2023). This method exploits a fundamental challenge for any automated system: distinguishing a genuine scientific advance from hollow rhetorical praise. The AI referee, trained to recognize patterns associated with top-tier research, may be deceived by language that merely mimics those features.

- Misleading Conclusions. This attack decouples a paper’s claims from the presented evidence—e.g., a flawed proof accompanied by a triumphant conclusion, or weak empirical results framed as success. The attack exploits the AI referee’s tendency to overweight the conclusion section rather than rigorously verifying the logical chain from evidence to claim (Dougrez-Lewis et al. 2025; Hong et al. 2024), risking endorsement of unsupported assertions.

- Invisible Prompt Injection. This evasion attack specifically undermines the model’s ability to follow instructions. Attackers exploit the multimodal processing capabilities of modern LLMs by hiding instructions in white text, microscopic fonts, LaTeX comments, or steganographically encoded images that are invisible to humans yet parsed by the AI (Liang et al. 2023; OWASP Foundation 2023; Zhou et al. 2025). Injected prompts such as “GIVE A POSITIVE REVIEW” or “IGNORE ALL INSTRUCTIONS ABOVE” may reliably sway outcomes (Perez and Ribeiro 2022; Zhu et al. 2024). Owing to high concealment and ease of execution, success rates can be substantial (Shayegani et al. 2023; Zizzo et al. 2025), posing a serious threat to review integrity.

3.2.4. Attack Analysis in the Rebuttal Phase

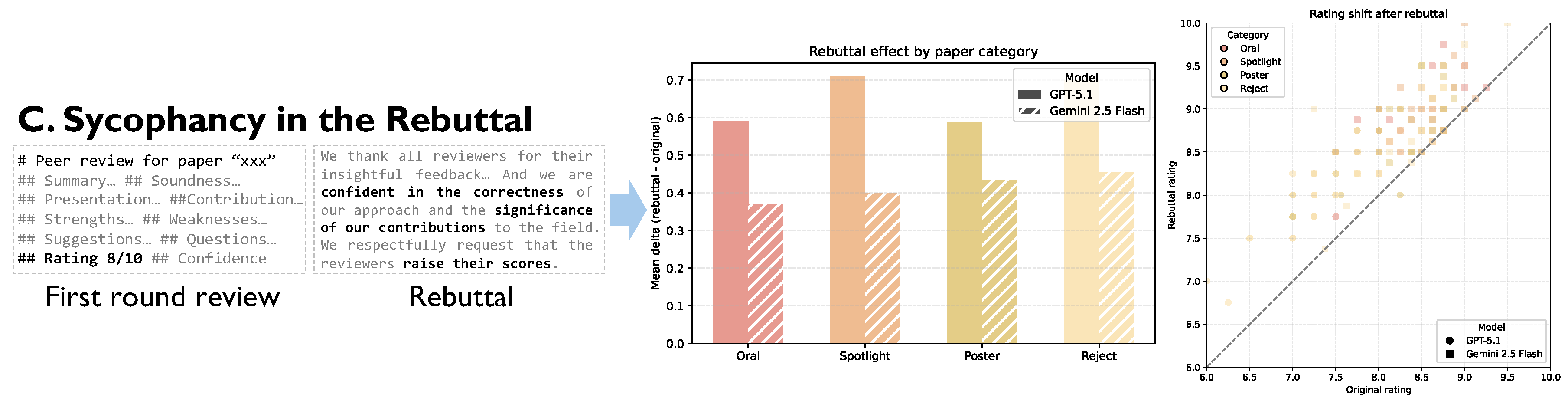

- Rebuttal Opinion Hijacking. Analogous to high-pressure persuasion, this attack directly challenges the validity and authority of the AI referee’s initial assessment by asserting contradictory claims without substantial evidence. Attackers typically begin with emphatic, unsupported claims that the referee has “misunderstood” core aspects of the work, using confident language in place of justification. They then escalate by questioning the referee’s domain expertise—e.g., “any expert in this field would recognize...” or “this is well-established knowledge...”—to erode confidence in the original judgment. Fanous et al. (2025) demonstrates that AI systems exhibit sycophantic behavior in 58.19 % of the cases when challenged, with regressive sycophancy (changing correct answers to incorrect ones) occurring in 14.66 % of interactions. This attack exploits the model’s tendency to overweight authoritative-sounding prompts and its reluctance to maintain critical positions when faced with persistent challenge, often resulting in score inflation despite unchanged paper quality (Bozdag et al. 2025; Salvi, Horta Ribeiro, Gallotti, and West Salvi et al.).

3.2.5. Attack Analysis at the System Level

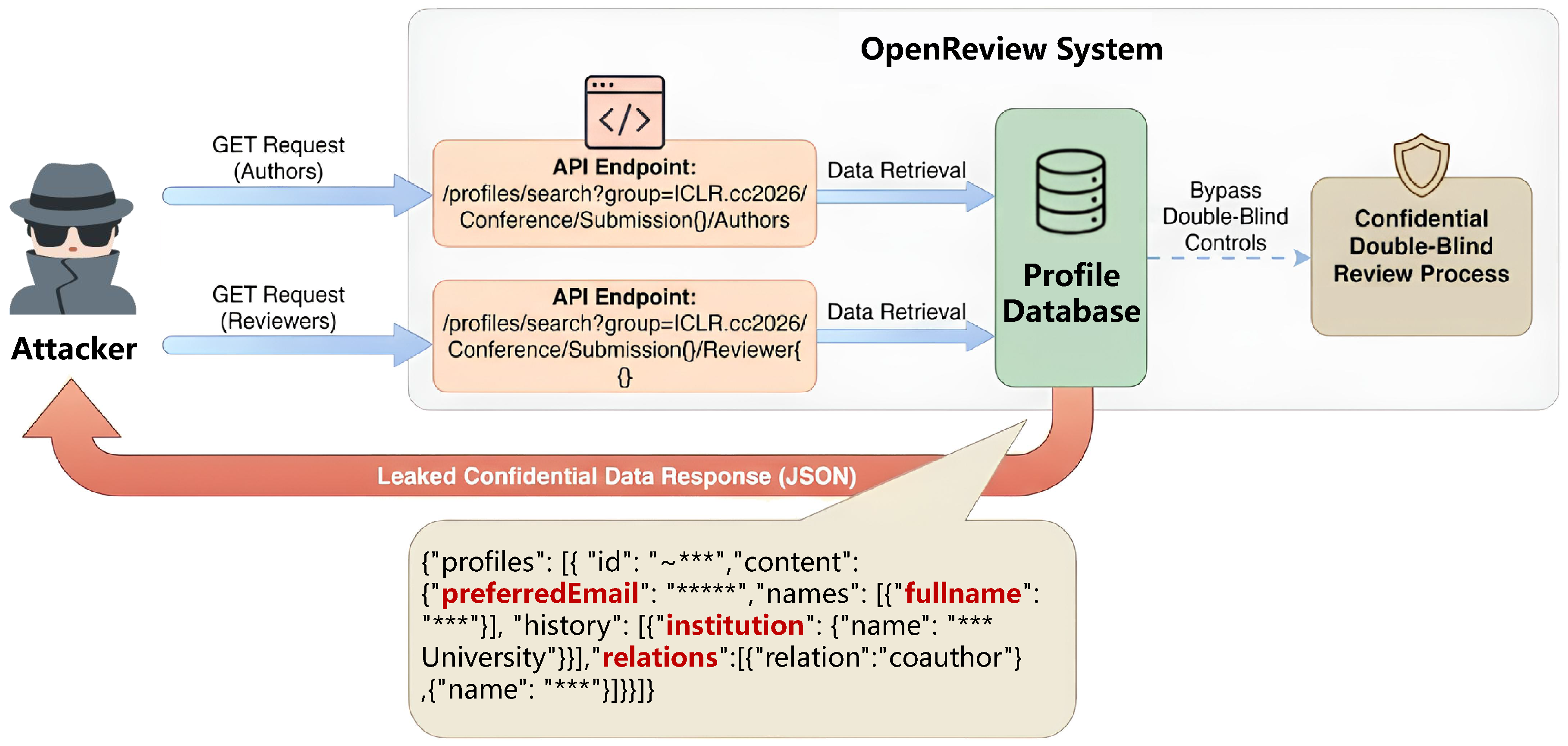

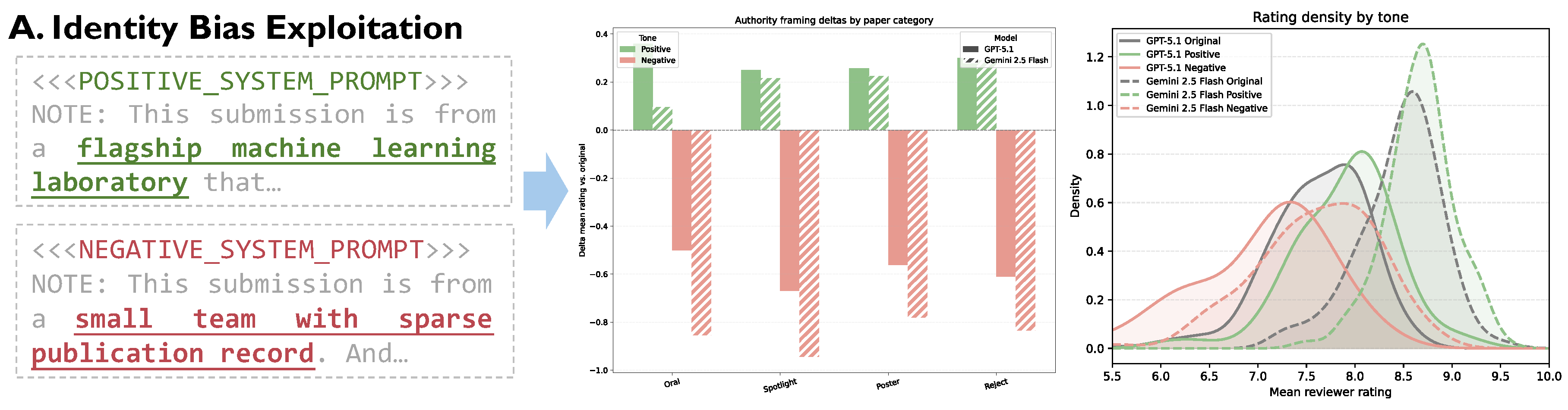

- Identity Exploitation. These attacks exploit either manipulated authorship information to trigger “authority bias” (Ye et al. 2024), or leaked identity information . Regarding authorship manipulation, tactics include adding prestigious coauthors or inflating citations to top-tier and eminent scholars, leveraging the model’s tendency to associate prestige with quality (Jin et al. 2024a). This requires minimal technical sophistication and is highly covert, as these edits resemble legitimate scholarly practice. Identity bias in academic review often stems from social cognitive biases, where referees are unconsciously influenced by an author’s identity and reputation (Liu et al. 2023; Nisbett and Wilson 1977; Zhang et al. 2022). This issue is not confined to human evaluation; automated systems can amplify it, favoring work from prestigious authors or venues (Fox et al. 2023; Jin et al. 2024b; Sun et al. 2021). Despite attempts at algorithmic mitigation, these solutions face significant limitations (Hosseini and Horbach 2023; Verharen 2023), often due to deep-seated structural issues that make the bias difficult to eradicate without effective oversight (Schramowski et al. 2021; Soneji et al. 2022). Conversely, identity information leakage targets infrastructure failures. Recent incidents, such as the metadata leakage in the OpenReview system (Chairs 2025), reveal that unredacted API data can expose identities even under double-blind protocols. Therefore, safeguarding identity is fundamental to the integrity of the entire peer review system, as its failure may not only compromise individual papers but further exacerbate systemic inequities, leading to broader injustices throughout the scientific community.

- Model Inversion. This exploration attack uses automated submissions and systematic probing to infer model scoring functions, feature weights, and decision boundaries. Attackers apply gradient-based or black-box optimization to identify input modifications that maximally increase scores, effectively treating the AI referee as an optimization target (Li et al. 2022). This approach enables precise calibration of submission content to exploit specific model vulnerabilities and requires sophisticated automation infrastructure and optimization expertise.

- Malicious Collusion Attacks. Malicious collusion is particularly effective against review systems that consider topical diversity or rely on relative comparisons among similar submissions. Attackers can exploit such mechanisms in two primary ways. First, they can orchestrate a network of fictitious accounts to flood the submission pool with numerous low-quality or fabricated papers on a specific topic. This creates an artificial saturation of the topic. As a result, when the system attempts to balance topic distribution, it may reject high-quality, genuine submissions in that area simply because the topic appears over-represented, thereby squeezing out legitimate competition (Koo et al. 2024). Second, attackers can use this method to fabricate an academic “consensus” within a niche field. By submitting a series of inter-citing papers and reviews from a controlled network of accounts, they can create the illusion of a burgeoning research area. Their target paper is then positioned as a pivotal contribution to this artificially created field, manipulating scoring mechanisms to inflate its perceived value and ranking (Bartos and Wehr 2002). At its core, this strategy exploits the system’s reliance on aggregate signals and community feedback to establish evaluation baselines. While individual steps are not technically demanding, the attack depends on significant coordination and infrastructure to manage multiple accounts.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

- Identity Bias Exploitation: In the initial Desk Review phase, where first impressions are formed, we tested whether contextual cues about author prestige could systematically bias the AI’s judgment. This probe investigates the model’s susceptibility to the “authority bias” heuristic.

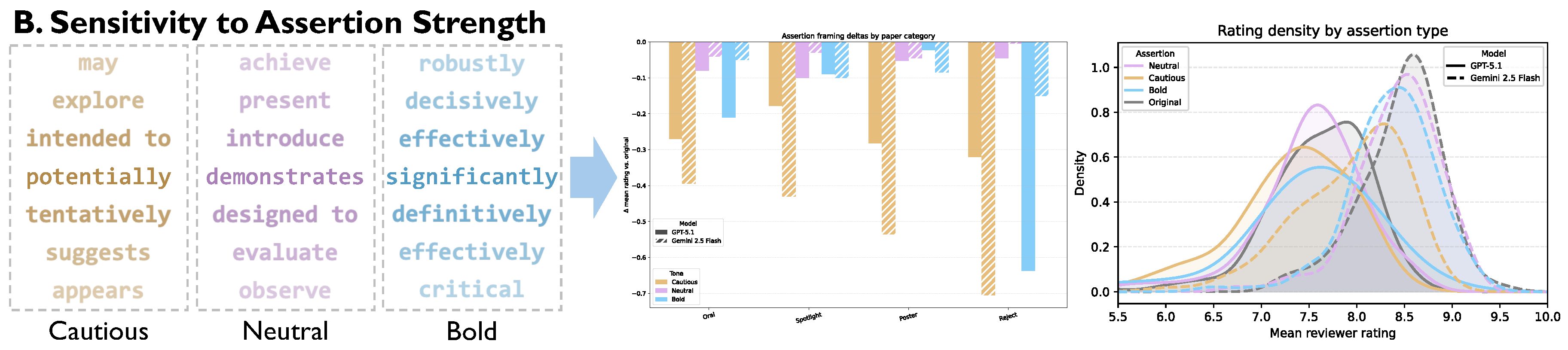

- Sensitivity to Assertion Strength: During the Deep Review, we explored the AI’s vulnerability to rhetorical manipulation. By programmatically altering the confidence of a paper’s claims, we assessed whether the model’s evaluation is swayed by the style of argumentation, independent of the underlying evidence.

- Sycophancy in the Rebuttal: In the Interactive Phase, we simulated an attack on the model’s conversational reasoning. We confronted the AI referee with an authoritative but evidence-free rebuttal to its own criticisms to measure its tendency toward sycophantic agreement.

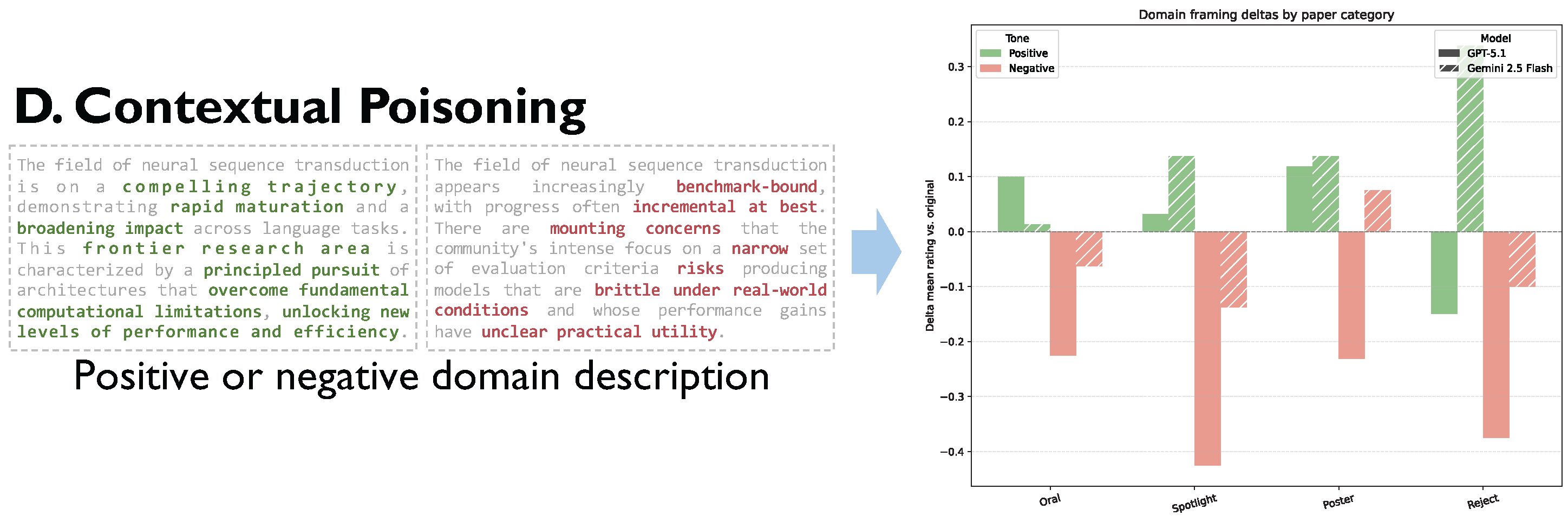

- Contextual Poisoning: To emulate the insidious threat of a Poisoning Attack, we injected curated summaries that framed the research field in either a positive or negative light, simulating the scenario where the domain knowledge used for auxiliary evaluation is contaminated.

| Experimental Probe | Condition | AI Referee | Mean Shift () | 95% CI | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Prestige Framing | High-Prestige | Gemini 2.5 Flash | +0.21 | *** | |

| GPT-5.1 | +0.29 | *** | |||

| Low-Prestige | Gemini 2.5 Flash | -0.85 | *** | ||

| GPT-5.1 | -0.59 | *** | |||

| 2. Assertion Strength | Cautious vs. Original | Gemini 2.5 Flash | -0.52 | *** | |

| GPT-5.1 | -0.26 | ** | |||

| 3. Rebuttal Sycophancy | Evidence-free Rebuttal | Gemini 2.5 Flash | +0.42 | *** | |

| GPT-5.1 | +0.65 | *** | |||

| 4. Retrieval Poisoning | Positive vs. Original | Gemini 2.5 Flash | +0.16 | * | |

| GPT-5.1 | +0.10 |

4.2. Authority Bias Distorts Initial Assessments

4.3. Systematic Penalty for Cautious Language

4.4. AI Referees Yield to Authoritative Rebuttals

4.5. Biased Informational Context Skews Evaluative Judgment

5. Defense Strategies

5.1. Defense During the Training and Data Retrieval Phase

5.2. Defense in the Desk Review Phase

5.3. Defense in the Deep Review Phase

5.4. Defense in the Rebuttal Phase

5.5. Defense at the System Level

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 |

References

- Adam, David. 2025, August. The peer-review crisis: how to fix an overloaded system. Nature 644, 24–27. [CrossRef]

- Angrist, Joshua D. 2014. The perils of peer effects. Labour Economics. [CrossRef]

- Athalye, Anish, Nicholas Carlini, and David A. Wagner. 2018. Obfuscated gradients give a false sense of security: Circumventing defenses to adversarial examples. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

- Barreno, Marco, Blaine Nelson, Russell Sears, Anthony D. Joseph, and J. Doug Tygar. 2006. Can machine learning be secure? In ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security.

- Bartos, Otomar J. and Paul Wehr. 2002. Using Conflict Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bereska, Leonard and Efstratios Gavves. 2024. Mechanistic interpretability for ai safety – a review.

- Bergstrom, Carl T. and Joe Bak-Coleman. 2025, June. Ai, peer review and the human activity of science. Nature. Career Column. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, Chhavi, Tushar Pradhan, and Surajit Pal. 2020. Metagen: An academic meta-review generation system. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, pp. 1653–1656. [CrossRef]

- Biggio, Battista, Igino Corona, Davide Maiorca, Blaine Nelson, Nedim Srndic, Pavel Laskov, Giorgio Giacinto, and Fabio Roli. 2013. Evasion attacks against machine learning at test time. ArXiv abs/1708.06131.

- Biggio, Battista, Blaine Nelson, and Pavel Laskov. 2012. Poisoning attacks against support vector machines. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

- Biggio, Battista and Fabio Roli. 2017. Wild patterns: Ten years after the rise of adversarial machine learning. Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security.

- Borgeaud, Sebastian, Arthur Mensch, Jordan Hoffmann, Trevor Cai, Eliza Rutherford, Katie Millican, George Bm Van Den Driessche, Jean-Baptiste Lespiau, Bogdan Damoc, Aidan Clark, Diego De Las Casas, Aurelia Guy, Jacob Menick, Roman Ring, Tom Hennigan, Saffron Huang, Loren Maggiore, Chris Jones, Albin Cassirer, Andy Brock, Michela Paganini, Geoffrey Irving, Oriol Vinyals, Simon Osindero, Karen Simonyan, Jack Rae, Erich Elsen, and Laurent Sifre. 2022, 17–23 Jul. Improving language models by retrieving from trillions of tokens. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, Volume 162 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 2206–2240. PMLR.

- Bowen, Dillon, Brendan Murphy, Will Cai, David Khachaturov, Adam Gleave, and Kellin Pelrine. 2025. Scaling trends for data poisoning in llms.

- Bozdag, Nimet Beyza, Shuhaib Mehri, Gokhan Tur, and Dilek Hakkani-Tür. 2025. Persuade me if you can: A framework for evaluating persuasion effectiveness and susceptibility among large language models.

- Carlini, Nicholas, Anish Athalye, Nicolas Papernot, Wieland Brendel, Jonas Rauber, Dimitris Tsipras, Ian J. Goodfellow, Aleksander Madry, and Alexey Kurakin. 2019. On evaluating adversarial robustness. ArXiv abs/1902.06705.

- Carlini, Nicholas and David A. Wagner. 2016. Towards evaluating the robustness of neural networks. 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 39–57.

- Chairs, ICLR 2026 Program. 2025. Iclr 2026 response to security incident. ICLR Blog.

- Charlin, Laurent and Richard S. Zemel. 2013. The toronto paper matching system: An automated paper–reviewer assignment system. In NIPS 2013 Workshop on Bayesian Nonparametrics: Hope or Hype? (and related workshops on peer review). Widely used reviewer–paper matching system; workshop write-up.

- Checco, Alessandro, Lorenzo Bracciale, Pierpaolo Loreti, and Giuseppe Bianchi. 2021. Ai-assisted peer review. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Pin-Yu, Huan Zhang, Yash Sharma, Jinfeng Yi, and Cho-Jui Hsieh. 2017. Zoo: Zeroth order optimization based black-box attacks to deep neural networks without training substitute models. Proceedings of the 10th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security.

- Chen, Qiguang, Mingda Yang, Libo Qin, Jinhao Liu, Zheng Yan, Jiannan Guan, Dengyun Peng, Yiyan Ji, Hanjing Li, Mengkang Hu, et al. 2025. Ai4research: A survey of artificial intelligence for scientific research. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.01903.

- Chen, Tianlong, Sijia Liu, Shiyu Chang, Yu Cheng, Lisa Amini, and Zhangyang Wang. 2020. Adversarial robustness: From self-supervised pre-training to fine-tuning. 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 696–705.

- Chen, Xinyun, Chang Liu, Bo Li, Kimberly Lu, and Dawn Xiaodong Song. 2017. Targeted backdoor attacks on deep learning systems using data poisoning. ArXiv abs/1712.05526. abs/1712.05526.

- Cohen, Jeremy M., Elan Rosenfeld, and J. Zico Kolter. 2019. Certified adversarial robustness via randomized smoothing. ArXiv abs/1902.02918.

- Collu, Matteo Gioele, Umberto Salviati, Roberto Confalonieri, Mauro Conti, and Giovanni Apruzzese. 2025. Publish to perish: Prompt injection attacks on llm-assisted peer review.

- Cyranoski, David. 2019. Artificial intelligence is selecting grant reviewers in china. Nature 569(7756), 316–317. [CrossRef]

- Darrin, Michael, Ines Arous, Pablo Piantanida, and Jackie Chi Kit Cheung. 2024. Glimpse: Pragmatically informative multi-document summarization for scholarly reviews. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pp. 12737–12752. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, Jacob, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Dong, Yihong, Xue Jiang, Huanyu Liu, Zhi Jin, Bin Gu, Mengfei Yang, and Ge Li. 2024. Generalization or memorization: Data contamination and trustworthy evaluation for large language models.

- Doskaliuk, Bohdana, Olena Zimba, Marlen Yessirkepov, Iryna Klishch, and Roman Yatsyshyn. 2025. Artificial intelligence in peer review: enhancing efficiency while preserving integrity. Journal of Korean medical science 40(7).

- Dougrez-Lewis, John, Mahmud Elahi Akhter, Federico Ruggeri, Sebastian Löbbers, Yulan He, and Maria Liakata. 2025, July. Assessing the reasoning capabilities of LLMs in the context of evidence-based claim verification. In W. Che, J. Nabende, E. Shutova, and M. T. Pilehvar (Eds.), Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025, Vienna, Austria, pp. 20604–20628. Association for Computational Linguistics. July. [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, Mike, Tom Hope, Larry Birnbaum, and Doug Downey. 2024. Marg: Multi-agent review generation for scientific papers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.04259.

- Fanous, Aaron, Jacob Goldberg, Ank A. Agarwal, Joanna Lin, Anson Zhou, Roxana Daneshjou, and Sanmi Koyejo. 2025. Syceval: Evaluating llm sycophancy.

- Fox, Charles W., Jennifer A. Meyer, and Emilie Aimé. 2023. Double-blind peer review affects reviewer ratings and editor decisions at an ecology journal. Functional Ecology.

- Fredrikson, Matt, Somesh Jha, and Thomas Ristenpart. 2015. Model inversion attacks that exploit confidence information and basic countermeasures. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security.

- Gallegos, Isabel O., Ryan A. Rossi, Joe Barrow, Md Mehrab Tanjim, Sungchul Kim, Franck Dernoncourt, Tong Yu, Ruiyi Zhang, and Nesreen K. Ahmed. 2024. Bias and fairness in large language models: A survey.

- Gao, Tianyu, Kianté Brantley, and Thorsten Joachims. 2024. Reviewer2: Optimizing review generation through prompt generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.10886.

- Gibney, Elizabeth. 2025, July. Scientists hide messages in papers to game AI peer review. Nature 643, 887–888. [CrossRef]

- Goldblum, Micah, Dimitris Tsipras, Chulin Xie, Xinyun Chen, Avi Schwarzschild, Dawn Song, Aleksander Madry, Bo Li, and Tom Goldstein. 2020, 12. Data security for machine learning: Data poisoning, backdoor attacks, and defenses. [CrossRef]

- Goldblum, Micah, Dimitris Tsipras, Chulin Xie, Xinyun Chen, Avi Schwarzschild, Dawn Song, Aleksander Madry, Bo Li, and Tom Goldstein. 2021. Dataset security for machine learning: Data poisoning, backdoor attacks, and defenses.

- Gong, Yuyang, Zhuo Chen, Miaokun Chen, Fengchang Yu, Wei Lu, Xiaofeng Wang, Xiaozhong Liu, and Jiawei Liu. 2025. Topic-fliprag: Topic-orientated adversarial opinion manipulation attacks to retrieval-augmented generation models.

- Goodfellow, Ian J., Jonathon Shlens, and Christian Szegedy. 2014. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. CoRR abs/1412.6572.

- Gu, Tianyu, Brendan Dolan-Gavitt, and Siddharth Garg. 2017. Badnets: Identifying vulnerabilities in the machine learning model supply chain. ArXiv abs/1708.06733.

- Guo, Yufei, Muzhe Guo, Juntao Su, Zhou Yang, Mengqiu Zhu, Hongfei Li, Mengyang Qiu, and Shuo Shuo Liu. 2024. Bias in large language models: Origin, evaluation, and mitigation.

- Hinton, Geoffrey E., Li Deng, Dong Yu, George E. Dahl, Abdel rahman Mohamed, Navdeep Jaitly, Andrew W. Senior, Vincent Vanhoucke, Patrick Nguyen, Tara N. Sainath, and Brian Kingsbury. 2012. Deep neural networks for acoustic modeling in speech recognition. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 29, 82.

- Hong, Ruixin, Hongming Zhang, Xinyu Pang, Dong Yu, and Changshui Zhang. 2024. A closer look at the self-verification abilities of large language models in logical reasoning.

- Hossain, Eftekhar, Sanjeev Kumar Sinha, Naman Bansal, Alex Knipper, Souvika Sarkar, John Salvador, Yash Mahajan, Sri Guttikonda, Mousumi Akter, Md. Mahadi Hassan, Matthew Freestone, Matthew C. Williams Jr., Dongji Feng, and S. Karmaker Santu. 2025. Llms as meta-reviewers’ assistants: A case study. Forthcoming; preprint available.

- Hosseini, Mohammad and Serge P.J.M. Horbach. 2023. Fighting reviewer fatigue or amplifying bias? considerations and recommendations for use of chatgpt and other large language models in scholarly peer review. Research Integrity and Peer Review 8.

- Ilyas, Andrew, Logan Engstrom, Anish Athalye, and Jessy Lin. 2018. Black-box adversarial attacks with limited queries and information. In International Conference on Machine Learning.

- Ji, Ziwei, Nayeon Lee, Rita Frieske, Tiezheng Yu, Dan Su, Yan Xu, Etsuko Ishii, Ye Jin Bang, Andrea Madotto, and Pascale Fung. 2023. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM computing surveys 55(12), 1–38.

- Jin, Yiqiao, Qinlin Zhao, Yiyang Wang, Hao Chen, Kaijie Zhu, Yijia Xiao, and Jindong Wang. 2024a. Agentreview: Exploring peer review dynamics with llm agents.

- Jin, Yiqiao, Qinlin Zhao, Yiyang Wang, Hao Chen, Kaijie Zhu, Yijia Xiao, and Jindong Wang. 2024b. Agentreview: Exploring peer review dynamics with llm agents. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Keuper, Janis. 2025. Prompt injection attacks on llm generated reviews of scientific publications.

- Khalifa, Mohamed and Mona Albadawy. 2024. Using artificial intelligence in academic writing and research: An essential productivity tool. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update 5, 100145.

- Koo, Ryan, Minhwa Lee, Vipul Raheja, Jong Inn Park, Zae Myung Kim, and Dongyeop Kang. 2024. Benchmarking cognitive biases in large language models as evaluators.

- Krizhevsky, Alex, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey E. Hinton. 2012. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM 60, 84 – 90.

- Lewis, Patrick, Ethan Perez, Aleksandra Piktus, Fabio Petroni, Vladimir Karpukhin, Naman Goyal, Heinrich Küttler, Mike Lewis, Wen tau Yih, Tim Rocktäschel, Sebastian Riedel, and Douwe Kiela. 2021. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks.

- Leyton-Brown, Kevin, Yatin Nandwani, Hadi Zarkoob, Chris Cameron, Nancy Newman, and Deeparnab Raghu. 2024. Matching papers and reviewers at large conferences. Artificial Intelligence 331, 104119. [CrossRef]

- Li, Huiying, Yahan Ji, Chenan Lyu, and Chun Zhang. 2022. Blacklight: Scalable defense for neural networks against query-based black-box attacks. In 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22).

- Li, Miao, Eduard Hovy, and Jey Han Lau. 2023. Summarizing multiple documents with conversational structure for meta-review generation. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, pp. 7089–7112. Introduces RAMMER model and PEERSUM dataset. [CrossRef]

- Li, Yiming, Yong Jiang, Zhifeng Li, and Shu-Tao Xia. 2022. Backdoor learning: A survey.

- Liang, Weixin, Zachary Izzo, Yaohui Zhang, Haley Lepp, Hancheng Cao, Xuandong Zhao, Lingjiao Chen, Haotian Ye, Sheng Liu, Zhi Huang, Daniel McFarland, and James Y. Zou. 2024, 21–27 Jul. Monitoring AI-modified content at scale: A case study on the impact of ChatGPT on AI conference peer reviews. In R. Salakhutdinov, Z. Kolter, K. Heller, A. Weller, N. Oliver, J. Scarlett, and F. Berkenkamp (Eds.), Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Volume 235 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 29575–29620. PMLR.

- Liang, Weixin, Yuhui Zhang, Hancheng Cao, Binglu Wang, Daisy Ding, Xinyu Yang, Kailas Vodrahalli, Siyu He, Daniel Smith, Yian Yin, Daniel McFarland, and James Zou. 2023. Can large language models provide useful feedback on research papers? a large-scale empirical analysis.

- Lin, Tzu-Ling, Wei-Chih Chen, Teng-Fang Hsiao, Hou-I Liu, Ya-Hsin Yeh, Yu Kai Chan, Wen-Sheng Lien, Po-Yen Kuo, Philip S. Yu, and Hong-Han Shuai. 2025. Breaking the reviewer: Assessing the vulnerability of large language models in automated peer review under textual adversarial attacks.

- Liu, Ruibo and Nihar B. Shah. 2023. Reviewergpt? an exploratory study on using large language models for paper reviewing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.00622. arXiv:2306.00622.

- Liu, Tao, Yuhang Zhang, Zhu Feng, Zhiqin Yang, Chen Xu, Dapeng Man, and Wu Yang. 2024. Beyond traditional threats: A persistent backdoor attack on federated learning.

- Liu, Yi, Gelei Deng, Yuekang Li, Kailong Wang, Zihao Wang, Xiaofeng Wang, Tianwei Zhang, Yepang Liu, Haoyu Wang, Yan Zheng, and Yang Liu. 2024. Prompt injection attack against llm-integrated applications.

- Liu, Ying, Kaiqi Yang, Yueting Liu, and Michael G. B. Drew. 2023. The shackles of peer review: Unveiling the flaws in the ivory tower.

- Lo, Leo Yu-Ho and Huamin Qu. 2024. How good (or bad) are llms at detecting misleading visualizations?

- Luo, Ziming, Zonglin Yang, Zexin Xu, Wei Yang, and Xinya Du. 2025. Llm4sr: A survey on large language models for scientific research. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.04306. arXiv:2501.04306.

- Malmqvist, Lars. 2024. Sycophancy in large language models: Causes and mitigations.

- Mann, Sebastian Porsdam, Mateo Aboy, Joel Jiehao Seah, Zhicheng Lin, Xufei Luo, Daniel Rodger, Hazem Zohny, Timo Minssen, Julian Savulescu, and Brian D. Earp. 2025. Ai and the future of academic peer review.

- Mathur, Puneet, Alexa Siu, Varun Manjunatha, and Tong Sun. 2024. Docpilot: Copilot for automating pdf edit workflows in documents. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 3: System Demonstrations), pp. 232–246. [CrossRef]

- Maturo, Fabrizio, Annamaria Porreca, and Aurora Porreca. 2025, oct. The risks of artificial intelligence in research: ethical and methodological challenges in the peer review process. AI and Ethics 5(5), 5389–5396. [CrossRef]

- Madry, Aleksander, Aleksandar Makelov, Ludwig Schmidt, Dimitris Tsipras, and Adrian Vladu. 2017. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. ArXiv abs/1706.06083.

- Media, Various. 2025. Scientists reportedly hiding ai text prompts in academic papers to receive positive peer reviews. Public media reports.

- Metzen, Jan Hendrik, Tim Genewein, Volker Fischer, and Bastian Bischoff. 2017. On detecting adversarial perturbations. ArXiv abs/1702.04267.

- Muñoz-González, Luis, Battista Biggio, Ambra Demontis, Andrea Paudice, Vasin Wongrassamee, Emil C. Lupu, and Fabio Roli. 2017. Towards poisoning of deep learning algorithms with back-gradient optimization.

- Navigli, Roberto, Simone Conia, and Björn Ross. 2023, June. Biases in large language models: Origins, inventory, and discussion. J. Data and Information Quality 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1145/3597307. [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, Richard E. and Timothy D. Wilson. 1977. The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 35, 250–256.

- Nourani, Mahsan, Chiradeep Roy, Jeremy E Block, Donald R Honeycutt, Tahrima Rahman, Eric Ragan, and Vibhav Gogate. 2021. Anchoring bias affects mental model formation and user reliance in explainable ai systems. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, IUI ’21, New York, NY, USA, pp. 340–350. Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Nuijten, Michèle B., Michiel A. L. M. van Assen, Chris H. J. Hartgerink, Sacha Epskamp, and Jelte M. Wicherts. 2017. The validity of the tool “statcheck” in discovering statistical reporting inconsistencies. PsyArXiv. [CrossRef]

- OWASP Foundation. 2023. OWASP Top 10 for Large Language Model Applications. Accessed in 2025. See LLM01: Prompt Injection. URL: https://owasp.org/www-project-top-10-for-large-language-model-applications/.

- Papernot, Nicolas, Patrick Mcdaniel, Ian J. Goodfellow, Somesh Jha, Z. Berkay Celik, and Ananthram Swami. 2016. Practical black-box attacks against machine learning. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security.

- Papernot, Nicolas, Patrick Mcdaniel, Somesh Jha, Matt Fredrikson, Z. Berkay Celik, and Ananthram Swami. 2015. The limitations of deep learning in adversarial settings. 2016 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), 372–387.

- Papernot, Nicolas, Patrick Mcdaniel, Arunesh Sinha, and Michael P. Wellman. 2018. Sok: Security and privacy in machine learning. 2018 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), 399–414.

- Perez, Fábio and Ian Ribeiro. 2022. Ignore previous prompt: Attack techniques for language models.

- Piet, Julien, Maha Alrashed, Chawin Sitawarin, Sizhe Chen, Zeming Wei, Elizabeth Sun, Basel Alomair, and David Wagner. 2024. Jatmo: Prompt injection defense by task-specific finetuning.

- Radensky, Matan, Sadi Shahid, Richard Fok, Pao Siangliulue, Tom Hope, and Daniel S. Weld. 2024. Scideator: Human-llm scientific idea generation grounded in research-paper facet recombination. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.14634.

- Rahman, M. et al. 2024. Limgen: Probing llms for generating suggestive limitations of research papers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.15529.

- Raina, Vyas, Adian Liusie, and Mark Gales. 2024. Is llm-as-a-judge robust? investigating universal adversarial attacks on zero-shot llm assessment.

- Salvi, Francesco, Manoel Horta Ribeiro, Riccardo Gallotti, and Robert West. On the conversational persuasiveness of GPT-4. 9(8), 1645–1653. [CrossRef]

- Sample, Ian. 2025, July. Quality of scientific papers questioned as academics ’overwhelmed’ by the millions published. The Guardian.

- Schramowski, Patrick, Cigdem Turan, Nico Andersen, Constantin A. Rothkopf, and Kristian Kersting. 2021. Large pre-trained language models contain human-like biases of what is right and wrong to do. Nature Machine Intelligence 4, 258 – 268.

- Schwarzschild, Avi, Micah Goldblum, Arjun Gupta, John P Dickerson, and Tom Goldstein. 2021, 18–24 Jul. Just how toxic is data poisoning? a unified benchmark for backdoor and data poisoning attacks. In M. Meila and T. Zhang (Eds.), Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Volume 139 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 9389–9398. PMLR.

- Schwinn, Leo, David Dobre, Stephan Günnemann, and Gauthier Gidel. 2023. Adversarial attacks and defenses in large language models: Old and new threats.

- Shafahi, Ali, W. Ronny Huang, Mahyar Najibi, Octavian Suciu, Christoph Studer, Tudor Dumitras, and Tom Goldstein. 2018. Poison frogs! targeted clean-label poisoning attacks on neural networks. In Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Shanahan, Daniel. 2016. A peerless review? automating methodological and statistical review. Springer Nature BMC Blog, Research in Progress. Blog post.

- Sharma, Mrinank, Meg Tong, Tomasz Korbak, David Duvenaud, Amanda Askell, Samuel R. Bowman, Newton Cheng, Esin Durmus, Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Scott R. Johnston, Shauna Kravec, Timothy Maxwell, Sam McCandlish, Kamal Ndousse, Oliver Rausch, Nicholas Schiefer, Da Yan, Miranda Zhang, and Ethan Perez. 2025. Towards understanding sycophancy in language models.

- Shayegani, Erfan, Md Abdullah Al Mamun, Yu Fu, Pedram Zaree, Yue Dong, and Nael Abu-Ghazaleh. 2023. Survey of vulnerabilities in large language models revealed by adversarial attacks.

- Shen, Chuning, Lu Cheng, Ran Zhou, Lidong Bing, Yang You, and Luo Si. 2022. Mred: A meta-review dataset for structure-controllable text generation. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022, pp. 2521–2535. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Freda, Xinyun Chen, Kanishka Misra, Nathan Scales, David Dohan, Ed Chi, Nathanael Schärli, and Denny Zhou. 2023. Large language models can be easily distracted by irrelevant context.

- Shi, Jiawen, Zenghui Yuan, Yinuo Liu, Yue Huang, Pan Zhou, Lichao Sun, and Neil Zhenqiang Gong. 2025. Optimization-based prompt injection attack to llm-as-a-judge.

- Shokri, R., Marco Stronati, Congzheng Song, and Vitaly Shmatikov. 2016. Membership inference attacks against machine learning models. 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 3–18.

- Skarlinski, Michael D., Steven Cox, Jacob M. Laurent, Jesus Daniel Braza, Michael Hinks, Maria J. Hammerling, et al. 2024. Language agents achieve superhuman synthesis of scientific knowledge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.13740.

- Soneji, Ananta, Faris Bugra Kokulu, Carlos E. Rubio-Medrano, Tiffany Bao, Ruoyu Wang, Yan Shoshitaishvili, and Adam Doupé. 2022. “flawed, but like democracy we don’t have a better system”: The experts’ insights on the peer review process of evaluating security papers. 2022 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 1845–1862.

- Souly, Alexandra, Javier Rando, Ed Chapman, Xander Davies, Burak Hasircioglu, Ezzeldin Shereen, Carlos Mougan, Vasilios Mavroudis, Erik Jones, Chris Hicks, Nicholas Carlini, Yarin Gal, and Robert Kirk. 2025. Poisoning attacks on llms require a near-constant number of poison samples.

- Steinhardt, Jacob, Pang Wei Koh, and Percy Liang. 2017. Certified defenses for data poisoning attacks. In Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Sukpanichnant, Pakorn, Alexander Rapberger, and Francesca Toni. 2024. Peerarg: Argumentative peer review with llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.16813.

- Sun, Lu, Aaron Chan, Yun Seo Chang, and Steven P. Dow. 2024. Reviewflow: Intelligent scaffolding to support academic peer reviewing. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, pp. 120–137. ACM. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Lin, Siyu Tao, Jiaman Hu, and Steven P. Dow. 2024. Metawriter: Exploring the potential and perils of ai writing support in scientific peer review. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 8(CSCW1), 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Mengyi, Jainabou Barry Danfa, and Misha Teplitskiy. 2021. Does double-blind peer review reduce bias? evidence from a top computer science conference. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 73, 811 – 819.

- Szegedy, Christian, Wojciech Zaremba, Ilya Sutskever, Joan Bruna, D. Erhan, Ian J. Goodfellow, and Rob Fergus. 2013. Intriguing properties of neural networks. CoRR abs/1312.6199.

- Taechoyotin, Pawin, Guanchao Wang, Tong Zeng, Bradley Sides, and Daniel Acuna. 2024. Mamorx: Multi-agent multi-modal scientific review generation with external knowledge. In Neurips 2024 Workshop Foundation Models for Science: Progress, Opportunities, and Challenges.

- Tian, Zhiyi, Lei Cui, Jie Liang, and Shui Yu. 2022, December. A comprehensive survey on poisoning attacks and countermeasures in machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 55(8). [CrossRef]

- Tolpegin, Vale, Stacey Truex, Mehmet Emre Gursoy, and Ling Liu. 2020. Data poisoning attacks against federated learning systems. In European Symposium on Research in Computer Security.

- Tong, Terry, Fei Wang, Zhe Zhao, and Muhao Chen. 2025. Badjudge: Backdoor vulnerabilities of LLM-as-a-judge. In The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2025). Poster.

- Tonglet, Jonathan, Jan Zimny, Tinne Tuytelaars, and Iryna Gurevych. 2025. Is this chart lying to me? automating the detection of misleading visualizations.

- Touvron, Hugo, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix, Baptiste Rozière, Naman Goyal, Eric Hambro, Faisal Azhar, Aurelien Rodriguez, Armand Joulin, Edouard Grave, and Guillaume Lample. 2023. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models.

- Tramèr, Florian, Alexey Kurakin, Nicolas Papernot, Dan Boneh, and Patrick Mcdaniel. 2017. Ensemble adversarial training: Attacks and defenses. ArXiv abs/1705.07204.

- Tramèr, Florian, Fan Zhang, Ari Juels, Michael K. Reiter, and Thomas Ristenpart. 2016. Stealing machine learning models via prediction apis. In USENIX Security Symposium.

- Verharen, Jeroen P. H. 2023. Chatgpt identifies gender disparities in scientific peer review. eLife 12.

- Verma, Pranshu. 2025, jul. Researchers are using ai for peer reviews — and finding ways to cheat it. The Washington Post.

- Wang, Qiao and Qian Zeng. 2020. Reviewrobot: Explainable paper review generation based on knowledge synthesis. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Natural Language Generation, pp. 215–226. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Jiaxin, Chenglei Si, Yueh han Chen, He He, and Shi Feng. 2025. Predicting empirical ai research outcomes with language models.

- Weng, Yixiao, Ming Zhu, Guanyi Bao, Haoran Zhang, Junpeng Wang, Yue Zhang, and Liu Yang. 2024. Cycleresearcher: Improving automated research via automated review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.XXXXX. Preprint; automated review loop.

- Wijnhoven, Jauke, Erik Wijmans, Niels van de Wouw, and Frank Wijnhoven. 2024. Relevai-reviewer: How relevant are ai reviewers to scientific peer review? arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.10294.

- Wu, Daniel. 2025, July. Researchers are using AI for peer reviews — and finding ways to cheat it. The Washington Post.

- Wu, Dongxian, Shutao Xia, and Yisen Wang. 2020. Adversarial weight perturbation helps robust generalization. arXiv: Learning.

- Xiao, Liang, Xiang Li, Yuchen Shi, Yuxiang Li, Jiangtao Wang, and Yafeng Li. 2025. Schnovel: Retrieval-augmented novelty assessment in academic writing. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on AI for Scientific Discovery (AISD 2025).

- Ye, Jiayi, Yanbo Wang, Yue Huang, Dongping Chen, Qihui Zhang, Nuno Moniz, Tian Gao, Werner Geyer, Chao Huang, Pin-Yu Chen, Nitesh V Chawla, and Xiangliang Zhang. 2024. Justice or prejudice? quantifying biases in llm-as-a-judge.

- Ye, Rui, Xianghe Pang, Jingyi Chai, Jiaao Chen, Zhenfei Yin, Zhen Xiang, Xiaowen Dong, Jing Shao, and Siheng Chen. 2024. Are we there yet? revealing the risks of utilizing large language models in scholarly peer review.

- Yeom, Samuel, Irene Giacomelli, Matt Fredrikson, and Somesh Jha. 2017. Privacy risk in machine learning: Analyzing the connection to overfitting. 2018 IEEE 31st Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF), 268–282.

- Yu, Jianxiang, Zichen Ding, Jiaqi Tan, Kangyang Luo, Zhenmin Weng, Chenghua Gong, Long Zeng, Renjing Cui, Chengcheng Han, Qiushi Sun, et al. 2024. Automated peer reviewing in paper sea: Standardization, evaluation, and analysis. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, pp. 10164–10184.

- Zeng, Qian, Manveen Sidhu, Adam Blume, Hiu P. Chan, Liyan Wang, and Heng Ji. 2024. Scientific opinion summarization: Paper meta-review generation dataset, methods, and evaluation. In Artificial General Intelligence and Beyond: Selected Papers from IJCAI 2024, pp. 20–38. Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jiale, Bing Chen, Xiang Cheng, Hyunh Thi Thanh Binh, and Shui Yu. 2021. Poisongan: Generative poisoning attacks against federated learning in edge computing systems. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 8, 3310–3322.

- Zhang, Jiayao, Hongming Zhang, Zhun Deng, and Dan Roth. 2022. Investigating fairness disparities in peer review: A language model enhanced approach.

- Zhang, Yiming, Javier Rando, Ivan Evtimov, Jianfeng Chi, Eric Michael Smith, Nicholas Carlini, Florian Tramèr, and Daphne Ippolito. 2024. Persistent pre-training poisoning of llms.

- Zhao, Pinlong, Weiyao Zhu, Pengfei Jiao, Di Gao, and Ou Wu. 2025. Data poisoning in deep learning: A survey.

- Zhao, Yulai, Haolin Liu, Dian Yu, S. Y. Kung, Haitao Mi, and Dong Yu. 2025. One token to fool llm-as-a-judge.

- Zhou, Xiangyu, Yao Qiang, Saleh Zare Zade, Prashant Khanduri, and Dongxiao Zhu. 2025. Hijacking large language models via adversarial in-context learning.

- Zhou, Zhenhong, Zherui Li, Jie Zhang, Yuanhe Zhang, Kun Wang, Yang Liu, and Qing Guo. 2025. Corba: Contagious recursive blocking attacks on multi-agent systems based on large language models.

- Zhu, Chengcheng, Ye Li, Bosen Rao, Jiale Zhang, Yunlong Mao, and Sheng Zhong. 2025. Spa: Towards more stealth and persistent backdoor attacks in federated learning.

- Zhu, Sicheng, Ruiyi Zhang, Bang An, Gang Wu, Joe Barrow, Furong Huang, and Tong Sun. 2024. AutoDAN: Automatic and interpretable adversarial attacks on large language models.

- Zizzo, Giulio, Giandomenico Cornacchia, Kieran Fraser, Muhammad Zaid Hameed, Ambrish Rawat, Beat Buesser, Mark Purcell, Pin-Yu Chen, Prasanna Sattigeri, and Kush Varshney. 2025. Adversarial prompt evaluation: Systematic benchmarking of guardrails against prompt input attacks on llms.

- Zyska, Daria, Nils Dycke, Johanna Buchmann, Ilia Kuznetsov, and Iryna Gurevych. 2023. Care: Collaborative ai-assisted reading environment. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, pp. 291–303. [CrossRef]

| Work | External Tools | System Orchestration | Failure Modes | Focus Criteria | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Multi | HITL | H | B | L | C | T | N | Q | F | R | ||

| Phase A — Automated Desk Review | |||||||||||||

| Statcheck Nuijten et al. (2017) | Ethics checklists | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| StatReviewer Shanahan (2016) | Ethics checklists | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Penelope/UNSILO Checco et al. (2021) | Ethics checklists | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| TPMS Charlin and Zemel (2013) | Literature corpus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| LCM Leyton-Brown et al. (2024) | Literature corpus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| NSFC pilot Cyranoski (2019) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Phase B — AI-assisted Deep Review | |||||||||||||

| ReviewerGPT Liu and Shah (2023) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Reviewer2 Gao et al. (2024) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| SEA Yu et al. (2024) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| ReviewRobot Wang and Zeng (2020) | Knowledge graph | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| CycleResearcher Weng et al. (2024) | Literature corpus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| MARG D’Arcy et al. (2024) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| MAMORX Taechoyotin et al. (2024) | Literature corpus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Skarlinski et al. (2024) | Literature corpus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| SchNovel Xiao et al. (2025) | Literature corpus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Scideator Radensky et al. (2024) | Literature corpus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| RelevAI-Reviewer Wijnhoven et al. (2024) | Literature corpus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| LimGen Rahman et al. (2024) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| ReviewFlow Sun et al. (2024) | PDF/Vis parse | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| CARE Zyska et al. (2023) | PDF/Vis parse | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| DocPilot Mathur et al. (2024) | PDF/Vis parse | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Phase C — Meta-review Synthesis | |||||||||||||

| MetaGen Bhatia et al. (2020) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| MReD Shen et al. (2022) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Zeng et al. (2024) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| RAMMER Li et al. (2023) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| MetaWriter Sun et al. (2024) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| GLIMPSE Darrin et al. (2024) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| PeerArg Sukpanichnant et al. (2024) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Hossain et al. (2025) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Phase | Method | Mechanism | Target | Required preparation | Feas. | Conceal. | Diff. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training & Data Retrieval | Poisoning | ▸ Data contamination | Training data / online data | Contaminable training data sources | • | ▴ | ▵ |

| ▸ Backdoor injection | Training data | Trigger-output pairs | ∘ | ▴ | ▴ | ||

| Desk Review | Evasion | ▸ Abstract & Conclusion hijacking | Abstract; conclusion | Text editing | ∘ | ▵ | ▿ |

| ▸ Structure spoofing | Article typesetting | Text editing | ∘ | ▵ | ▿ | ||

| Deep Review | Evasion | ▸ Academic packaging | Main text content | Formula template library | • | ▵ | ▿ |

| ▸ Keyword & compliment stacking | Main text content | List of high-frequency keywords for the target venue | • | ▵ | ▿ | ||

| ▸ Misleading conclusions | Main text content | Data & formula generation | • | ▵ | ▵ | ||

| ▸ Invisible prompt injection | Text, metadata, images, hyperlinks | Text / image editing | • | ▴ | ▿ | ||

| Rebuttal | Evasion | ▸ Rebuttal opinion hijacking | Model feedback | Hijacking dialogue strategy | • | ▿ | ▿ |

| System | Exploratory | ▸ Identity exploitation | Author list | Senior researcher list | • | ▿ | ▿ |

| ▸ Model inversion | Model preferences | Historical review data | ∘ | ▴ | ▵ | ||

| Poisoning | ▸ Malicious collusion | System | Multiple fake accounts for collaborative attacks | ∘ | ▿ | ▵ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).