Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Patients and Data Acquisition

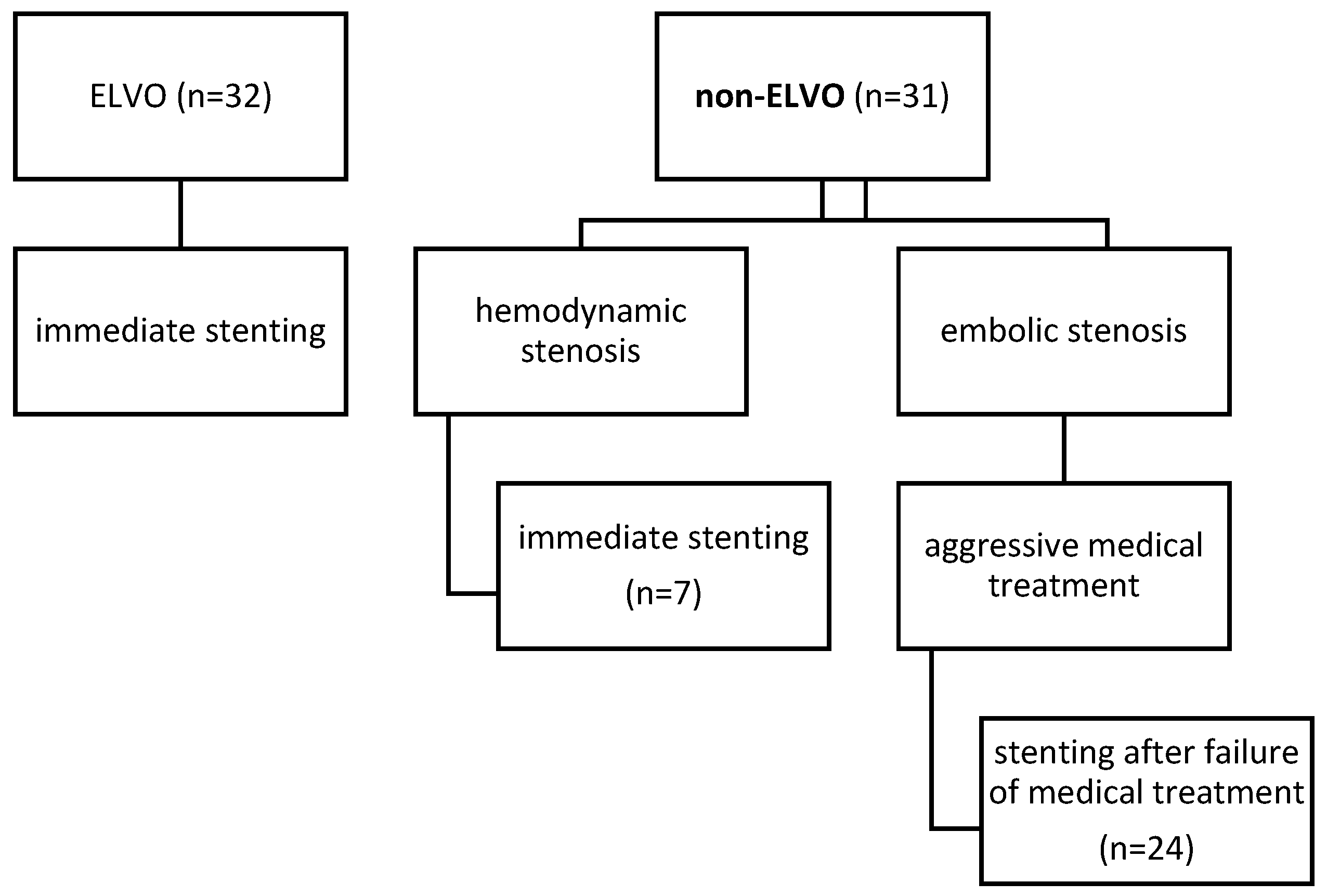

Study PopulationProcedures

Non-ELVO Case

ELVO CaseAntiplatelet Management

Outcome Parameters

Outcome Parameters in ELVO Patients

Outcome Parameters in Non-ELVO Patients

Statistics

3. Results

Baseline Characteristics

Outcome Parameters in ELVO Group

- Intracranial dissections with compromised side branch patency occurred in two out of 32 patients. Both cases were in the vertebrobasilar circulation and occurred after balloon angioplasty. In one of these two cases, there was subsequent in-stent thrombosis, which was fatal. In the other case, there were embolic and perforator infarction which led to worsening of the neurologic symptoms.

- Acute and subacute stent thrombosis were observed in two cases, both of which occurred in the vertebrobasilar circulation and were symptomatic: one of these two patients had progressive infarction, which led to neurological worsening (mRS=5); the other had stent-thrombosis after dissection, which was fatal (mentioned previously).

- There was no SAH.

- Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage occurred in two ELVO patients, both of them in anterior circulation. Only one of these two patients had intravenous thrombolysis therapy before the procedure. One patient recovered and improved neurologically (mRS=2); the other one deteriorated (mRS=4).

Outcome Parameters in Non-ELVO Group

Comparison of Anterior and Vertebrobasilar Circulation

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Competing interests

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the manuscript preparation process Statement

Abbreviations

| ICAS | intracranial artery stenosis |

| PTA | percutaneous transluminal angioplasty |

| ELVO | emergent large vessel occlusion |

| DSA | digital subtraction angiography |

| DAPT | dual antiplatelet therapy |

References

- Holmstedt CA, Turan TN, Chimowitz MI. Atherosclerotic intracranial arterial stenosis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:1106-1114. [CrossRef]

- Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:993-1003. [CrossRef]

- Kasner SE, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al. Predictors of ischemic stroke in the territory of a symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Circulation 2006;113:555-563. [CrossRef]

- Zaidat OO, Klucznik R, Alexander MJ, et al. The NIH registry on use of the Wingspan stent for symptomatic 70-99% intracranial arterial stenosis. Neurology 2008;70:1518-1524. [CrossRef]

- Derdeyn CP, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al. Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet 2014;383:333-341. [CrossRef]

- Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Varughese MC. Litigation seeking access to data from ongoing clinical trials: a threat to clinical research. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1502-1504. [CrossRef]

- Kurre W, Berkefeld J, Brassel F, et al. In-hospital complication rates after stent treatment of 388 symptomatic intracranial stenoses: results from the INTRASTENT multicentric registry. Stroke 2010;41:494-498. [CrossRef]

- Sangha RS, Naidech AM, Corado C, et al. Challenges in the Medical Management of Symptomatic Intracranial Stenosis in an Urban Setting. Stroke 2017;48:2158-2163. [CrossRef]

- Alexander MJ, Zauner A, Chaloupka JC, et al. WEAVE Trial: Final Results in 152 On-Label Patients. Stroke 2019;50:889-894. [CrossRef]

- Fiorella D, Derdeyn CP, Lynn MJ, et al. Detailed analysis of periprocedural strokes in patients undergoing intracranial stenting in Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS). Stroke 2012;43:2682-2688. [CrossRef]

- Nardai S, Kis B, Gubucz I, et al. Coronary stent implantation in acute basilar artery occlusion with underlying stenosis: potential for increased effectiveness in endovascular stroke therapy. EuroIntervention 2019.

- Ma N, Zhang Y, Shuai J, et al. Stenting for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis in China: 1-year outcome of a multicentre registry study. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2018;3:176-184. [CrossRef]

- Miao Z, Zhang Y, Shuai J, et al. Thirty-Day Outcome of a Multicenter Registry Study of Stenting for Symptomatic Intracranial Artery Stenosis in China. Stroke 2015;46:2822-2829. [CrossRef]

- Park SC, Cho SH, Kim MK, et al. Long-term Outcome of Angioplasty Using a Wingspan Stent, Post-Stent Balloon Dilation and Aggressive Restenosis Management for Intracranial Arterial Stenosis. Clin Neuroradiol 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gao P, Wang D, Zhao Z, et al. Multicenter Prospective Trial of Stent Placement in Patients with Symptomatic High-Grade Intracranial Stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37:1275-1280. [CrossRef]

- Meyer T, Nikoubashman O, Kabelitz L, et al. Endovascular stentectomy using the snare over stent-retriever (SOS) technique: An experimental feasibility study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0178197. [CrossRef]

- Chimowitz MI, Kokkinos J, Strong J, et al. The Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Study. Neurology 1995;45:1488-1493. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Sun Y, Li X, et al. Early versus delayed stenting for intracranial atherosclerotic artery stenosis with ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nordmeyer H, Chapot R, Aycil A, et al. Angioplasty and Stenting of Intracranial Arterial Stenosis in Perforator-Bearing Segments: A Comparison Between the Anterior and the Posterior Circulation. Front Neurol 2018;9:533. [CrossRef]

- Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016;387:1723-1731. [CrossRef]

- Baek JH, Kim BM, Heo JH, et al. Outcomes of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Intracranial Atherosclerosis-Related Large Vessel Occlusion. Stroke 2018;49:2699-2705. [CrossRef]

- Stracke CP, Meyer L, Fiehler J, et al. Intracranial bailout stenting with the Acclino (Flex) Stent/NeuroSpeed Balloon Catheter after failed thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke: a multicenter experience. J Neurointerv Surg 2020;12:43-47. [CrossRef]

- Wu C, Chang W, Wu D, et al. Angioplasty and/or stenting after thrombectomy in patients with underlying intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis. Neuroradiology 2019;61:1073-1081. [CrossRef]

- Gory B, Haussen DC, Piotin M, et al. Impact of intravenous thrombolysis and emergent carotid stenting on reperfusion and clinical outcomes in patients with acute stroke with tandem lesion treated with thrombectomy: a collaborative pooled analysis. Eur J Neurol 2018;25:1115-1120. [CrossRef]

- Karanam LSP, Sharma M, Alurkar A, et al. Balloon Angioplasty for Intracranial Atherosclerotic Disease: A Multicenter Study. J Vasc Interv Neurol 2017;9:29-34.

- Aghaebrahim A, Agnoletto GJ, Aguilar-Salinas P, et al. Endovascular Recanalization of Symptomatic Intracranial Arterial Stenosis Despite Aggressive Medical Management. World Neurosurg 2019;123:e693-e699. [CrossRef]

- Kim B, Kim BM, Bang OY, et al. Carotid Artery Stenting and Intracranial Thrombectomy for Tandem Cervical and Intracranial Artery Occlusions. Neurosurgery 2020;86:213-220. [CrossRef]

- Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1009-1018. [CrossRef]

- Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2285-2295. [CrossRef]

- Nordmeyer H, Chapot R, Haage P. Endovascular Treatment of Intracranial Atherosclerotic Stenosis. Rofo 2019;191:643-652. [CrossRef]

- Meyer L, Leischner H, Thomalla G, et al. Stenting with Acclino(R) (flex) for symptomatic intracranial stenosis as secondary stroke prevention. J Neurointerv Surg 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wabnitz AM, Derdeyn CP, Fiorella DJ, et al. Hemodynamic Markers in the Anterior Circulation as Predictors of Recurrent Stroke in Patients With Intracranial Stenosis. Stroke 2018:STROKEAHA118020840. [CrossRef]

- Derdeyn CP, Fiorella D, Lynn MJ, et al. Nonprocedural Symptomatic Infarction and In-Stent Restenosis After Intracranial Angioplasty and Stenting in the SAMMPRIS Trial (Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for the Prevention of Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis). Stroke 2017;48:1501-1506. [CrossRef]

- Wollenweber FA, Tiedt S, Alegiani A, et al. Functional Outcome Following Stroke Thrombectomy in Clinical Practice. Stroke 2019;50:2500-2506. [CrossRef]

| non-ELVO group (n=31) | ELVO group (n=32) | p-value | |

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age [median] | 71 (IQR, 59-73) | 64 (IQR, 58-71) | .239 |

| Female sex [n] | 8 (25%) | 8 (36%) | .365 |

| History of TIA [n] | 6 (19%) | 4 (13%) | .457 |

| History of stroke [n] | 28 (90%) | 5 (17%) | <.001 |

| Arterial hypertension [n] | 30 (97%) | 29 (91%) | .317 |

| Current smoker [n] | 8 (26%) | 7 (22%) | .714 |

| Diabetes mellitus [n] | 11 (34%) | 12 (38%) | .721 |

| Hyperlipidemia [n] | 9 (29%) | 7 (22%) | .514 |

| CHD [n] | 6 (19%) | 5 (16%) | .697 |

| Atrial fibrillation [n] | 4 (13%) | 6 (19%) | .525 |

| Previous medication | |||

| Anticoagulation [n] | 5 (16%) | 3 (9%) | .421 |

| None / mono / dual antiplatelets [n] | 4 / 6 / 21 (13% / 19% / 68%) | 20 / 9 /3 (63% / 28% / 9%) | <.001 |

| Statins [n] | 25 (81%) | 10 (31%) | <.001 |

| Stenosis characteristics | |||

| MCA [n] | 5 (16%) | 12 (38%) | |

| ICA [n] | 11 (36%) | 3 (9%) | .023 |

| Vertebrobasilar [n] | 15 (48%) | 17 (53%) | |

| Degree [median] | 82 (79-89) | 80 (71-90) | .448 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| mRS pre stroke [median] | 1 (IQR, 0-2) | 0 (IQR, 0-1) | .001 |

| NIHSS upon admission [median] | 4 (IQR, 1-10) | 13 (IQR, 5-21) | <.001 |

| Infarction Characteristics | |||

| Embolic infarction [n] | 12 (39%) | 22 (68%) | |

| Hemodynamic infarction [n] | 4 (13%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Mix type: embolic and hemodynamic infarction [n] | 9 (29%) | 5 (16%) | .018 |

| Perforator infarction [n] | 6 (19%) | 5(16%) | |

| Procedural characteristics | |||

| Balloon-expandable stents vs. self-expanding [n] | 27 / 4 (87% / 13%) | 14 /18 (44% / 56%) | <.001 |

| Dilatation before vs. after deployment [n] | 2 / 5 (7% / 16%) | 15 / 8 (47% / 25%) | <.001 |

| non-ELVO group (n=31) | ELVO group (n=32) | p-value | |

| Primary outcome | |||

| Technical success* [n] | 31 (100%) | 32 (100%) | |

| Reperfusion success** [n] | - | 30 (94%) | |

| Periinterventional complications (dissection, SAH, intracerebral hemorrhage (PH2), and stent -thrombosis) [n] | 0 (0%) | 5 (16%) | .022 |

|

0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | .157 |

|

0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

|

0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | .157 |

|

0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | .157 |

| Secondary outcome | |||

| Neurological improvement [n] | 13 (42%) | 16 (50%) | .521 |

| Neurological deterioration[n] | 2 (6%) | 7 (22%) | .041 |

| Death (in-hospital) [n] | 0 (0%) | 5 (16%) | .022 |

| mRS at discharge [median] | 2 (IQR, 1-3) | 4 (IQR, 2-5) | .02 |

| mRS 0-2 at discharge [n] | 17 (55%) | 10 (31%) | .059 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).