Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

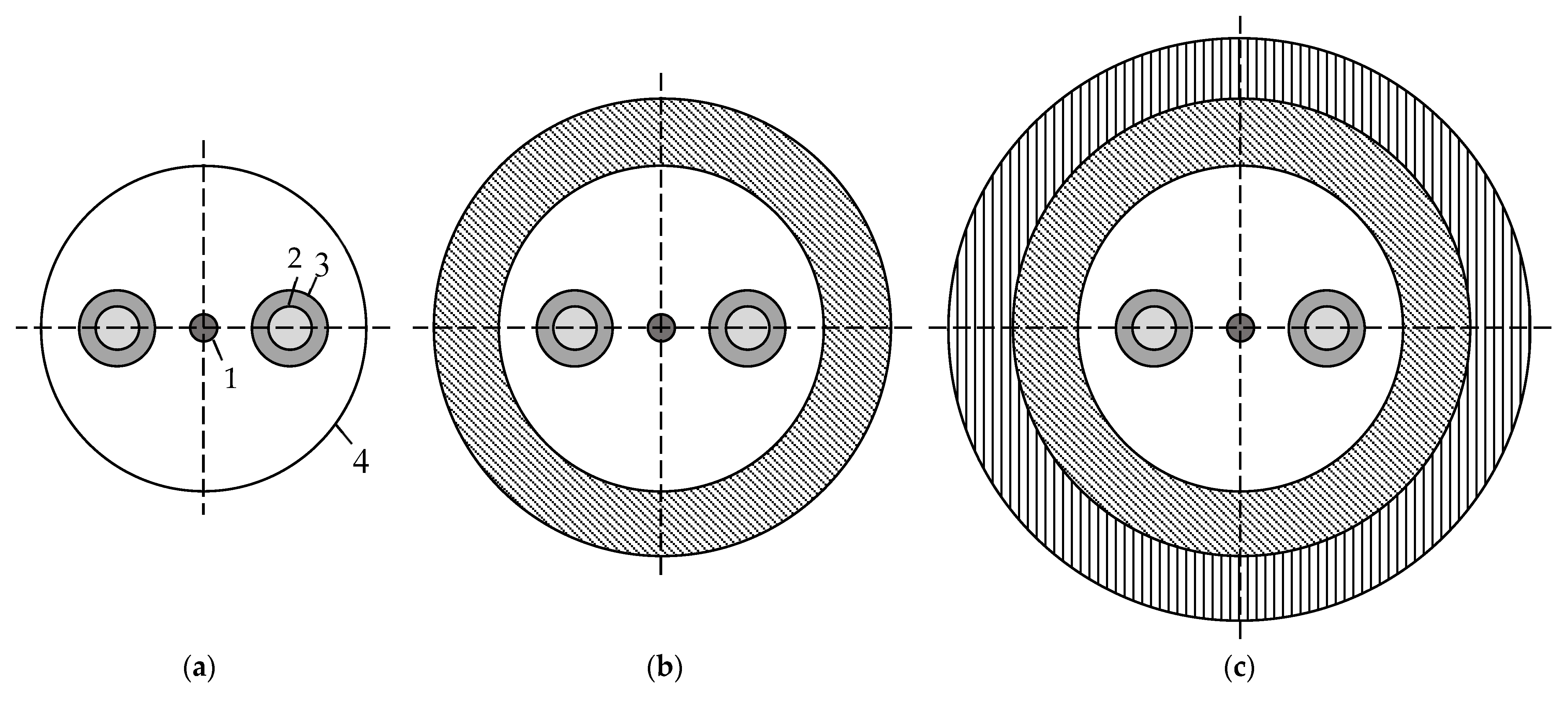

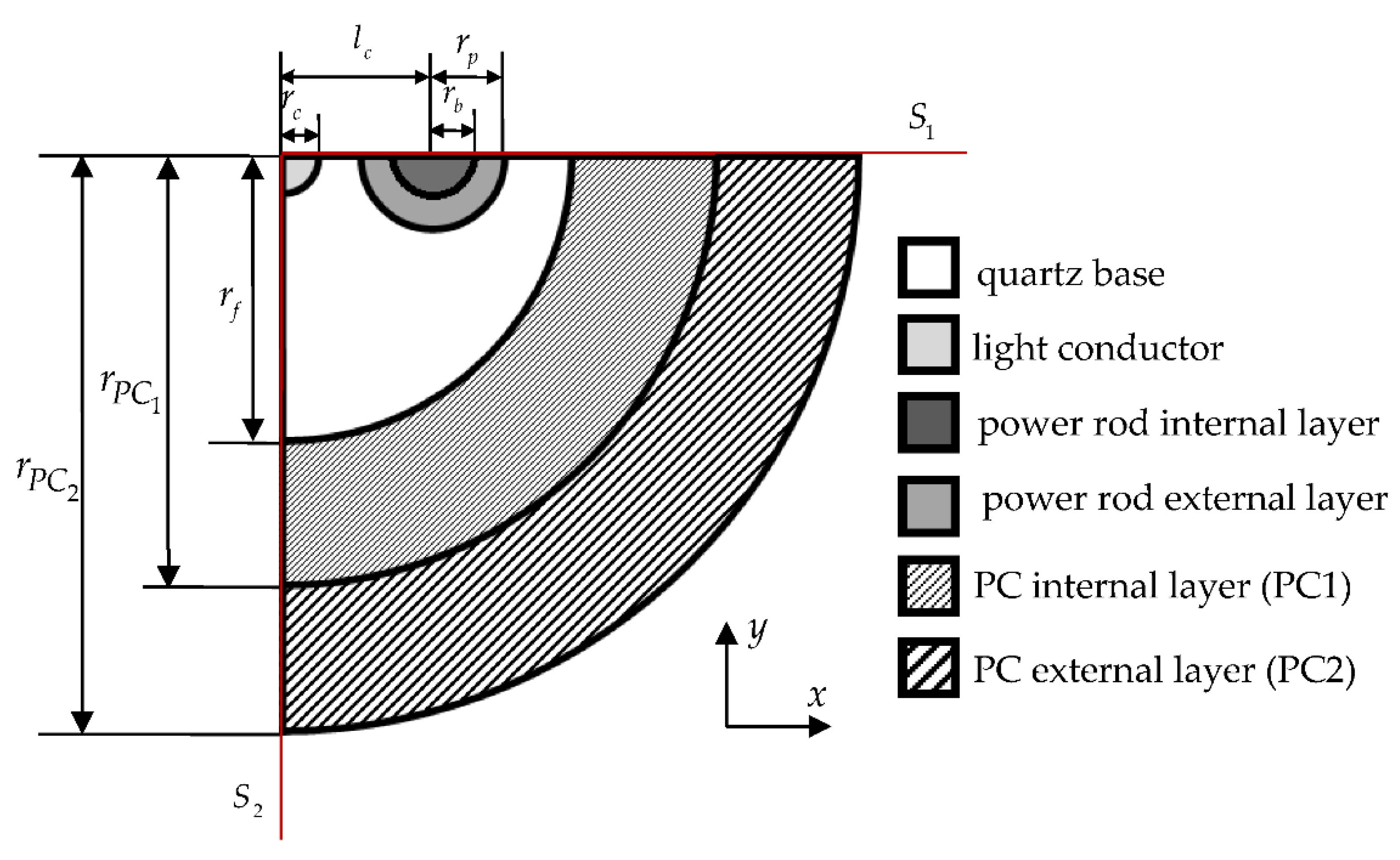

2.1. Panda-Type Optical Fiber

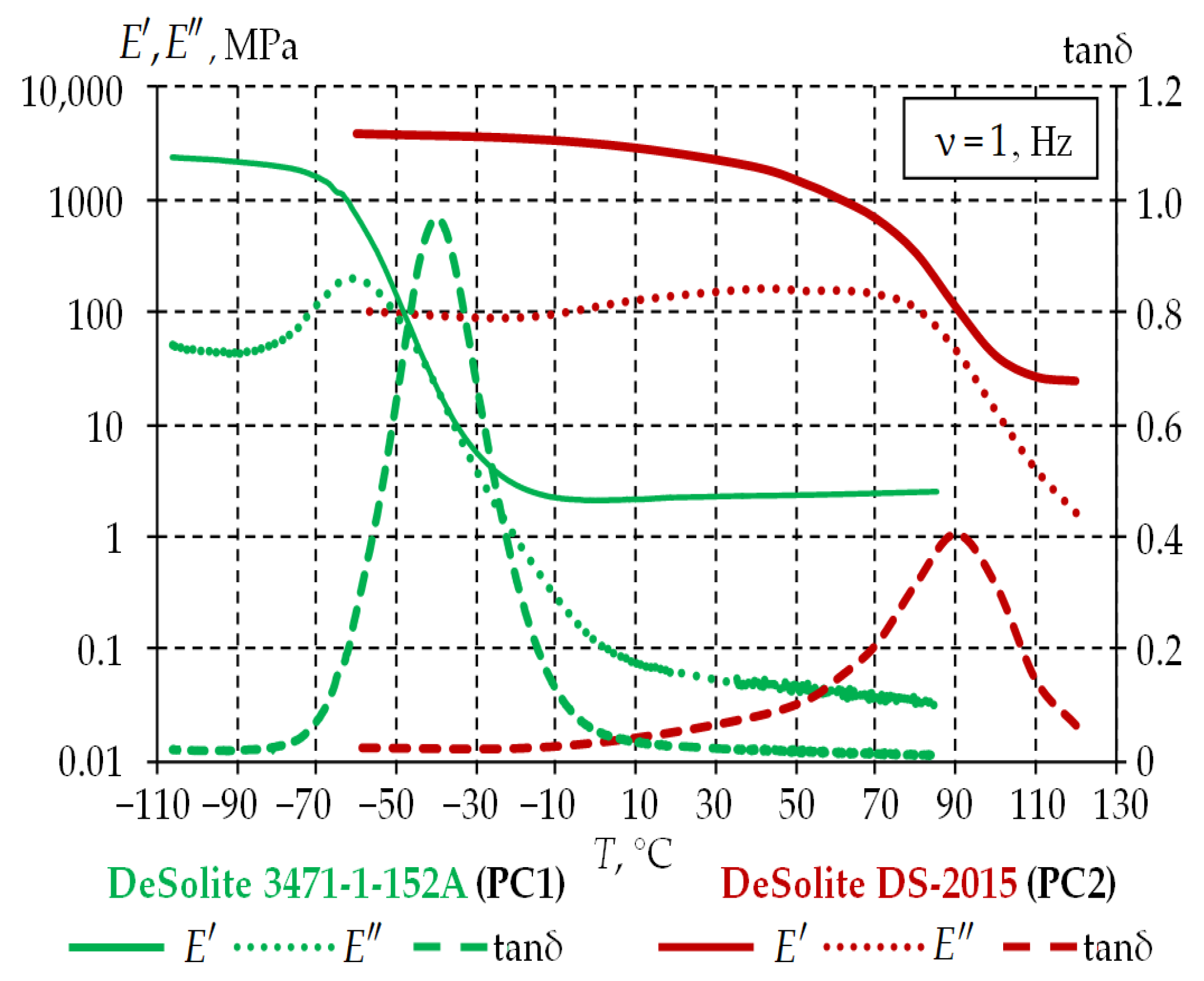

2.2. Materials of Polymer Coating

2.3. Experimental Study

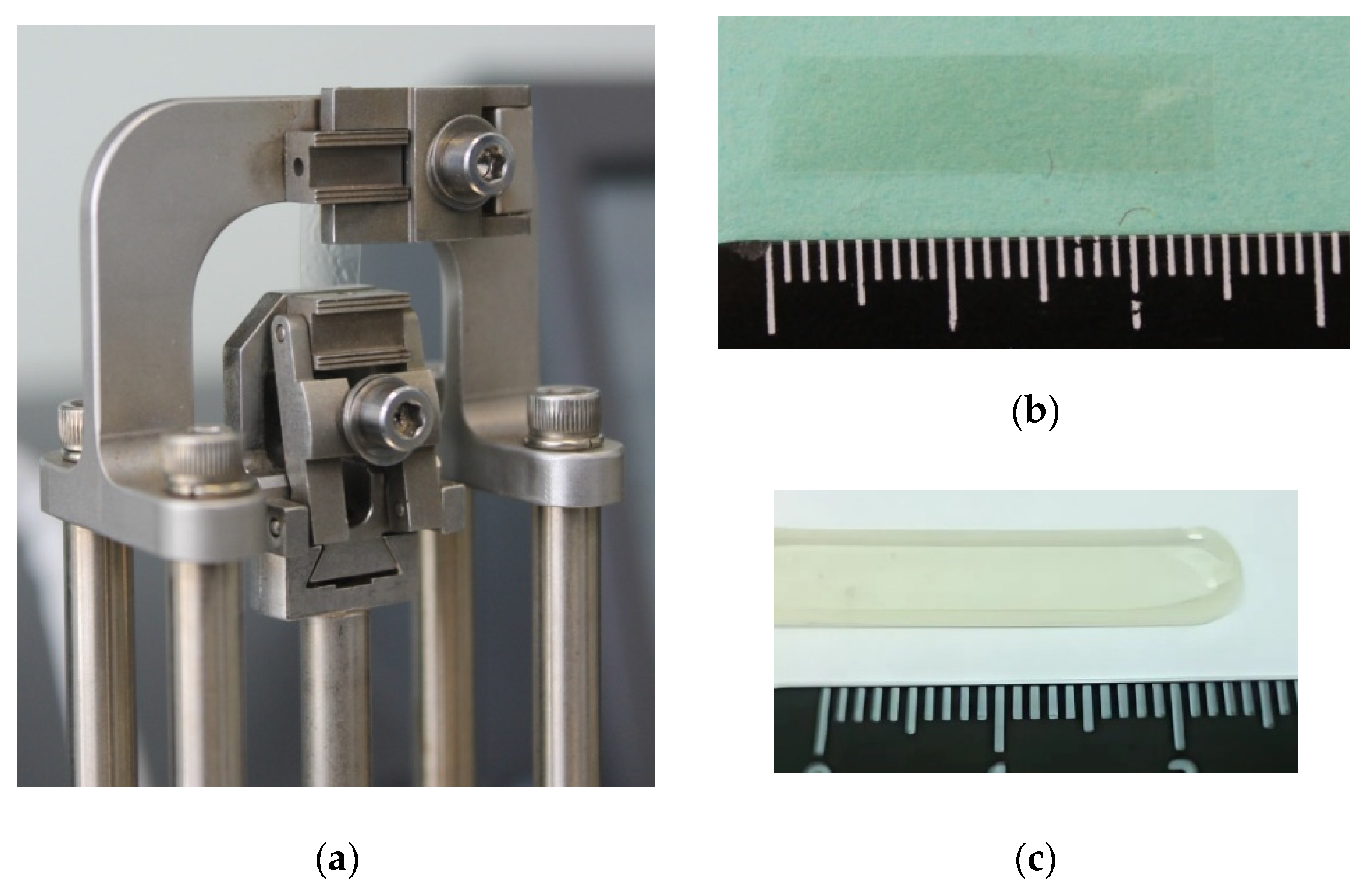

2.3.1. Equipment

2.3.2. Specimen Preparation

2.3.3. Experiment Setup

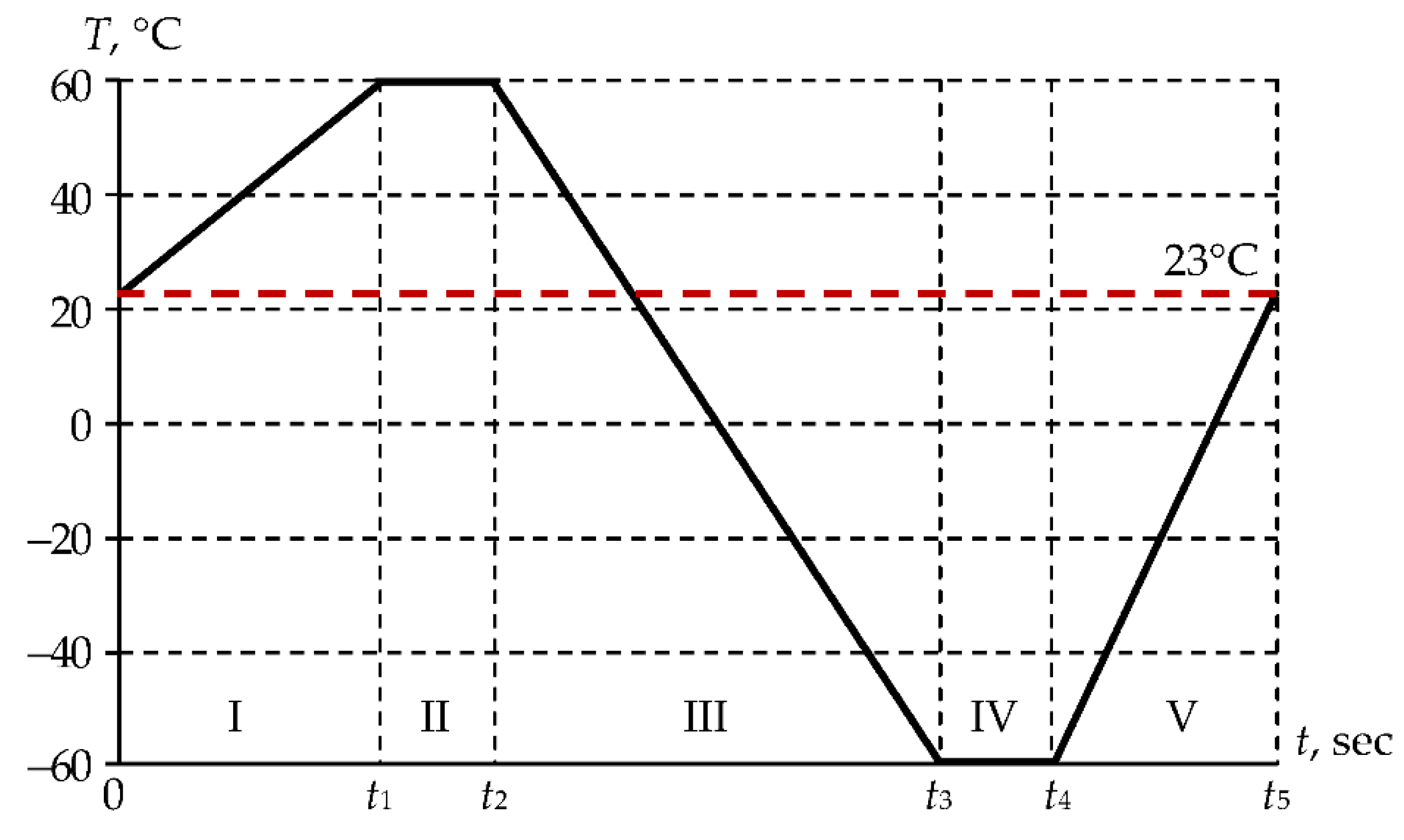

2.3.4. Experimental Procedure and Design

2.3.4.1. Determination of the Relaxation Transition Temperature Range of Polymer Coatings

- The specimens in the form of films or plates, fixed in special grips (see Figure 3), were heated significantly above the glass transition temperature.

- The study of the complex modulus is performed under oscillating load. It is superimposed on a constant force greater in magnitude than the amplitude of the harmonic component. After applying a constant load, operators waited for the complete realization of the deformation processes in the specimens, the end of which was determined by reaching a "shelf" of deformation on the time dependency diagram, at the temperature of the upper limit of the studied range, before starting the temperature changing process.

- The specimen was cooled down to the lower limit of the range at a constant rate of 2 °C/min under the influence of a harmonic force with a frequency of 1 Hz, and was kept until the deformation reached the above-mentioned "shelf", whereupon it was heated at the same rate to the initial temperature.

- Displacements, temperature, and force were recorded throughout the experiment. The dependencies of the storage and loss moduli and their ratio (_) were calculated on the basis of the data obtained for the hardware-software complex used.

2.3.4.2. Creep Experiment at a Constant Temperature and a Fixed Load

- The specimens in the form of films or plates were fixed in special grips of DMA Q800.

- The required temperature was set.

- Operators waited for the complete realization of the deformation processes in the specimens, caused by temperature deformations, the end of which was determined by reaching a "plateau" of deformation in a time dependency diagram.

- A load was applied, the value of which was constant throughout the entire subsequent experiment.

- The dependence of displacements (deformations) on time was recorded.

2.4. Numerical Simulation and Its Realization

2.4.1. Thermomechanics of Panda-Type Optical Fiber

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| 40 μm | 15 μm | ||

| 65 μm | 7.5 μm | ||

| 83.5 μm | 3.5 μm | ||

| 3 μm | 4 μm |

| Temperature cycle | t1, sec | t2, sec | t3, sec | t4, sec | t5, sec |

| cycle 1 | 40 | 70 | 130 | 160 | 190 |

| cycle 2 | 70 | 100 | 220 | 250 | 310 |

| cycle 3 | 130 | 160 | 400 | 430 | 550 |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Studies

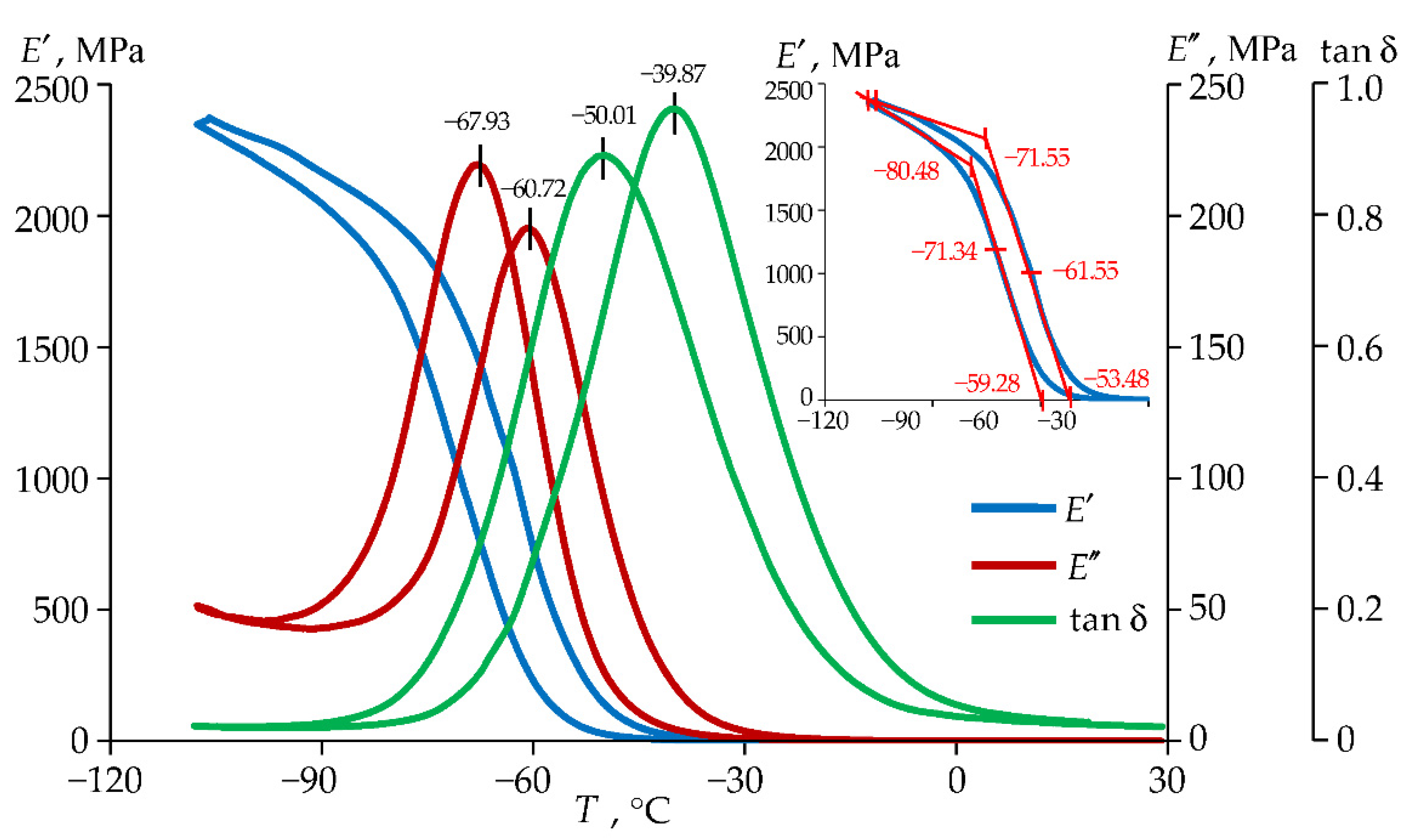

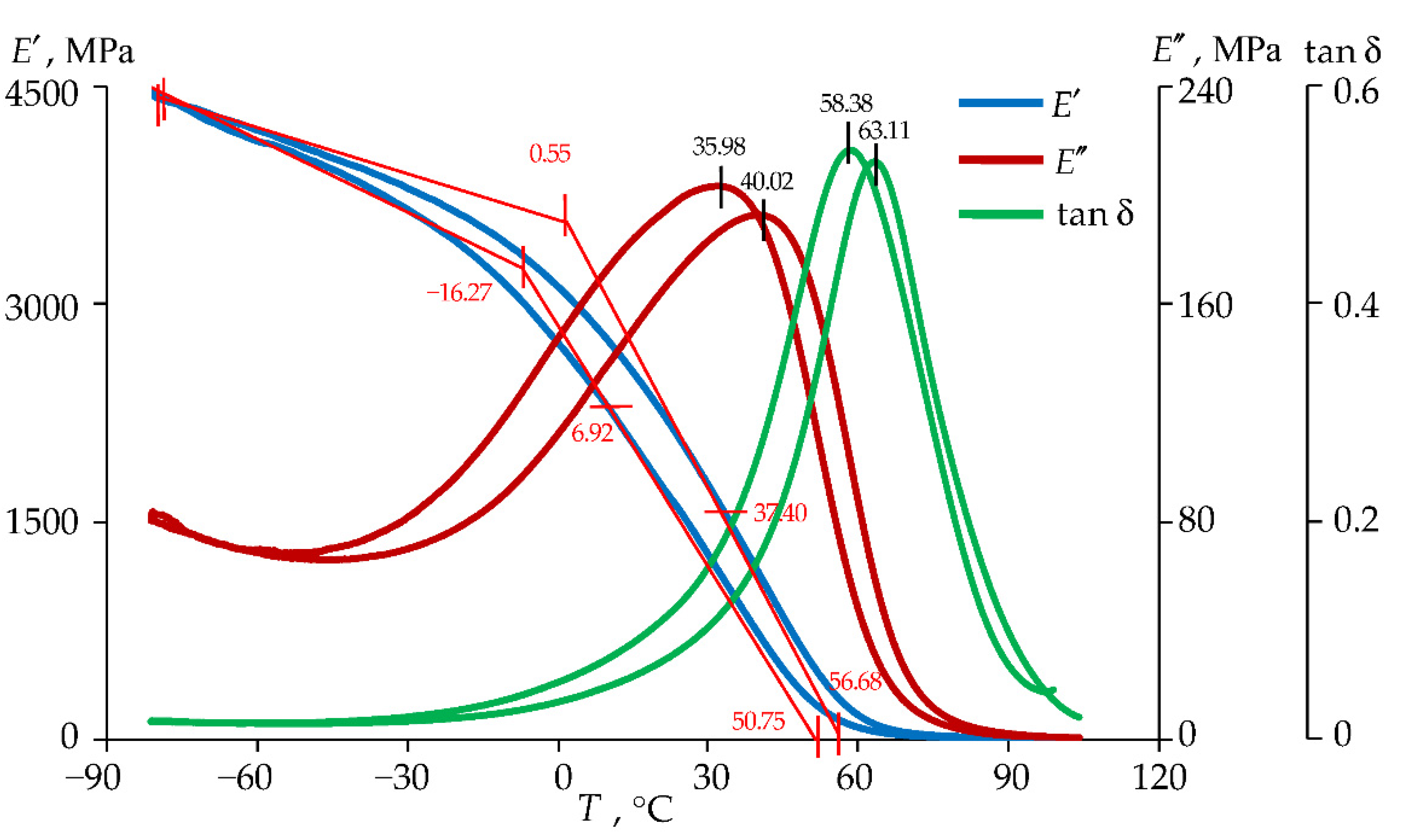

3.1.1. Glass Transition Temperature

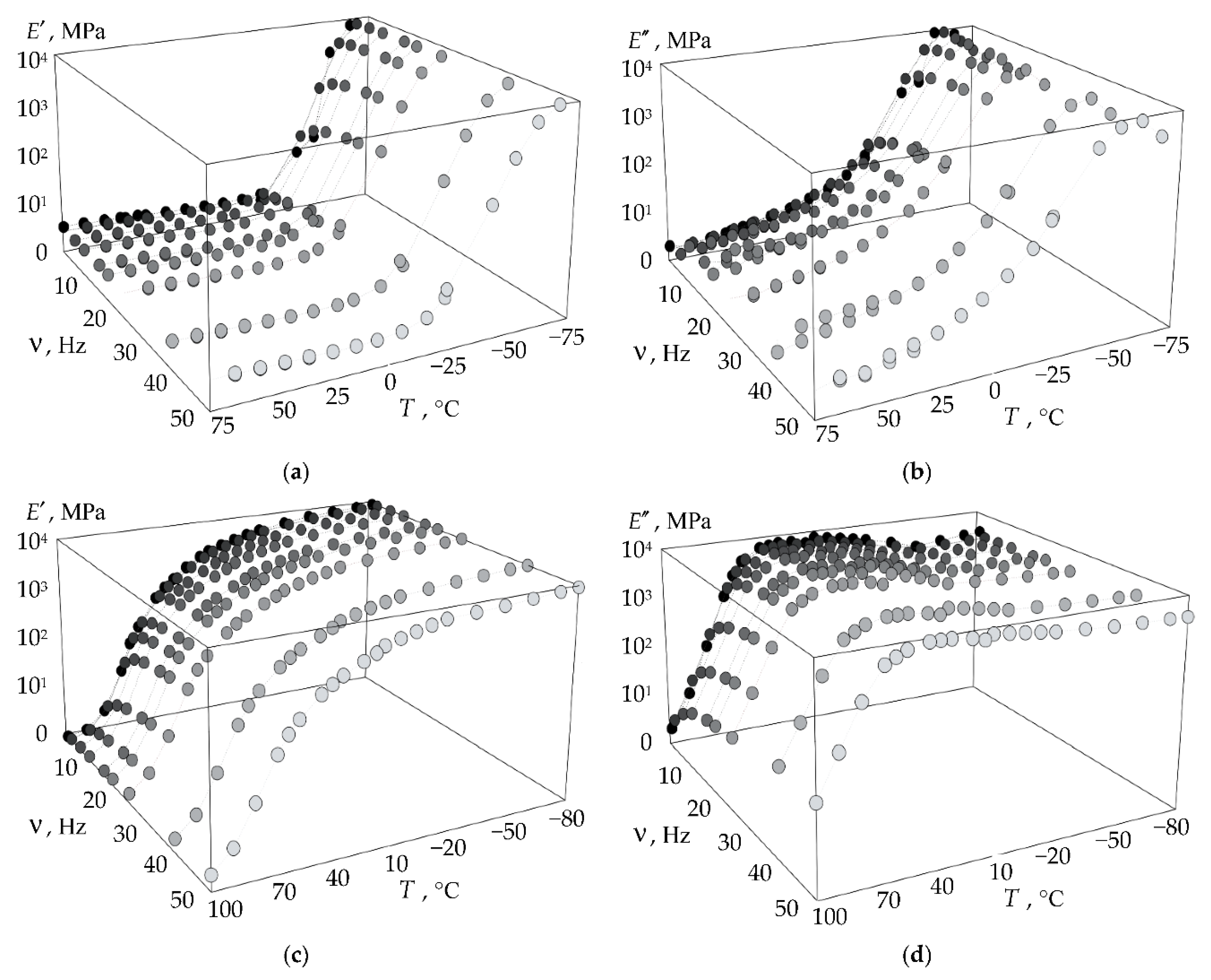

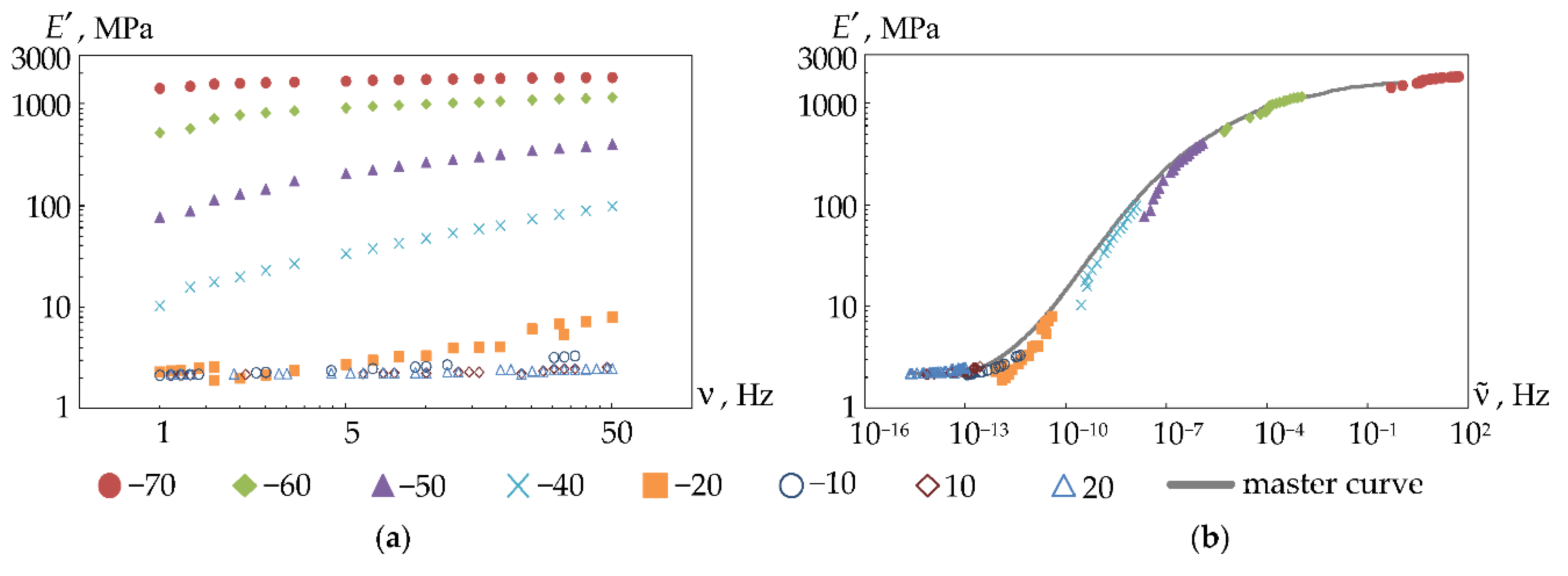

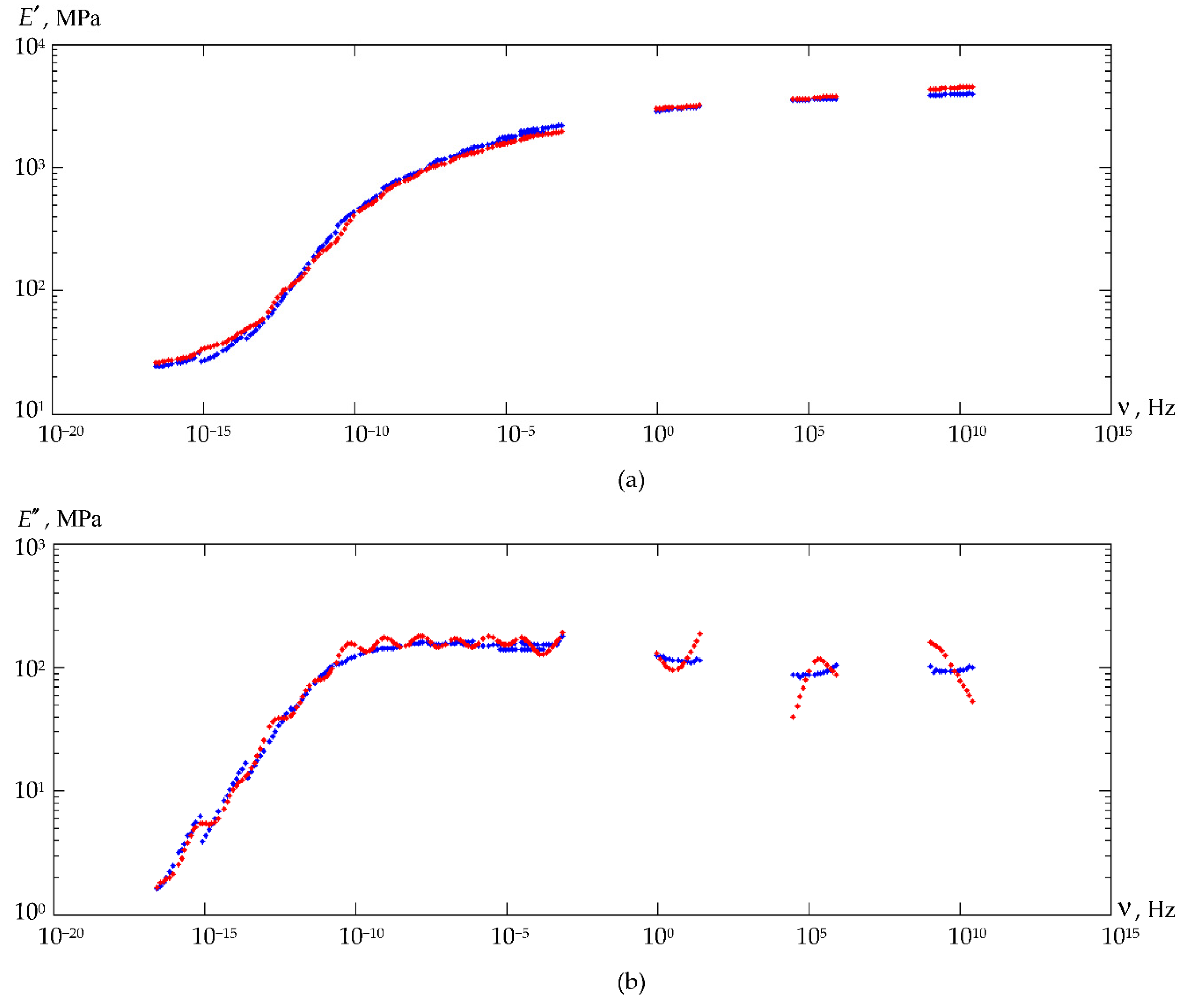

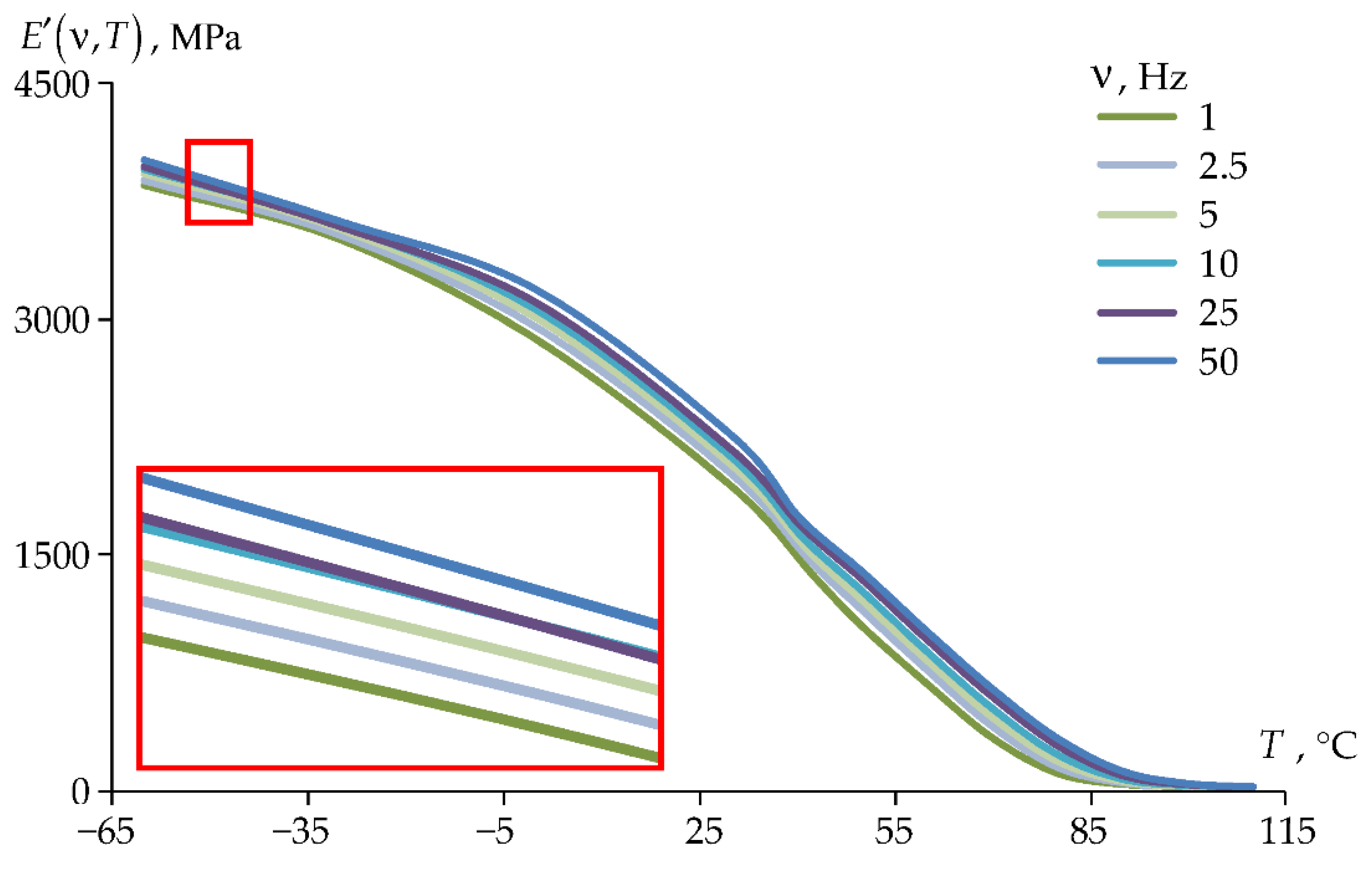

3.1.2. Viscoelastic Behavior of the Materials

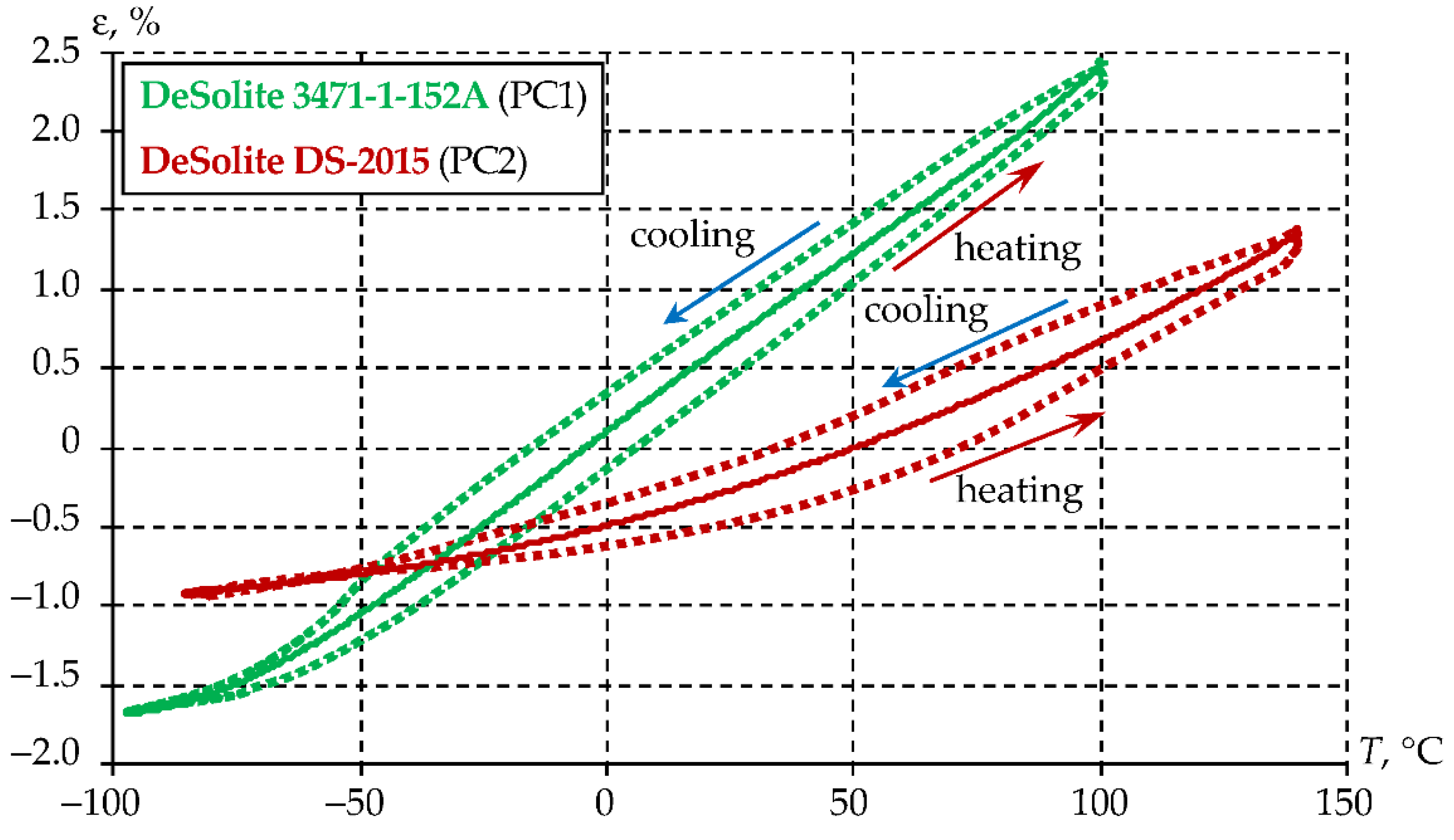

3.1.3. Thermal Expansion of the Materials

3.2. Numerical Analogue of Polymer Protective Coating Materials

3.2.1. Prony Series

| 1 | 3.14×10−3 | 1.29×10−4 | 7 | 2.80×10−1 | 5.99×102 | 13 | 4.43×10−4 | 2.78×109 |

| 2 | 2.83×10−2 | 1.67×10−3 | 8 | 3.23×10−2 | 7.74×103 | 14 | 1.06×10−3 | 3.59×1010 |

| 3 | 1.57×10−1 | 2.15×10−2 | 9 | 3.24×10−1 | 1.00×105 | 15 | 2.07×10−4 | 4.64×1011 |

| 4 | 6.38×10−4 | 2.78×10−1 | 10 | 2.81×10−2 | 1.29×106 | 16 | 8.22×10−5 | 5.99×1012 |

| 5 | 3.03×10−2 | 3.59E×100 | 11 | 6.21×10−3 | 1.67E×107 | 17 | 3.84×10−5 | 7.74×1013 |

| 6 | 6.28×10−2 | 4.64×101 | 12 | 4.36×10−2 | 2.15E×108 | 18 | 2.30×10−5 | 1.00×1015 |

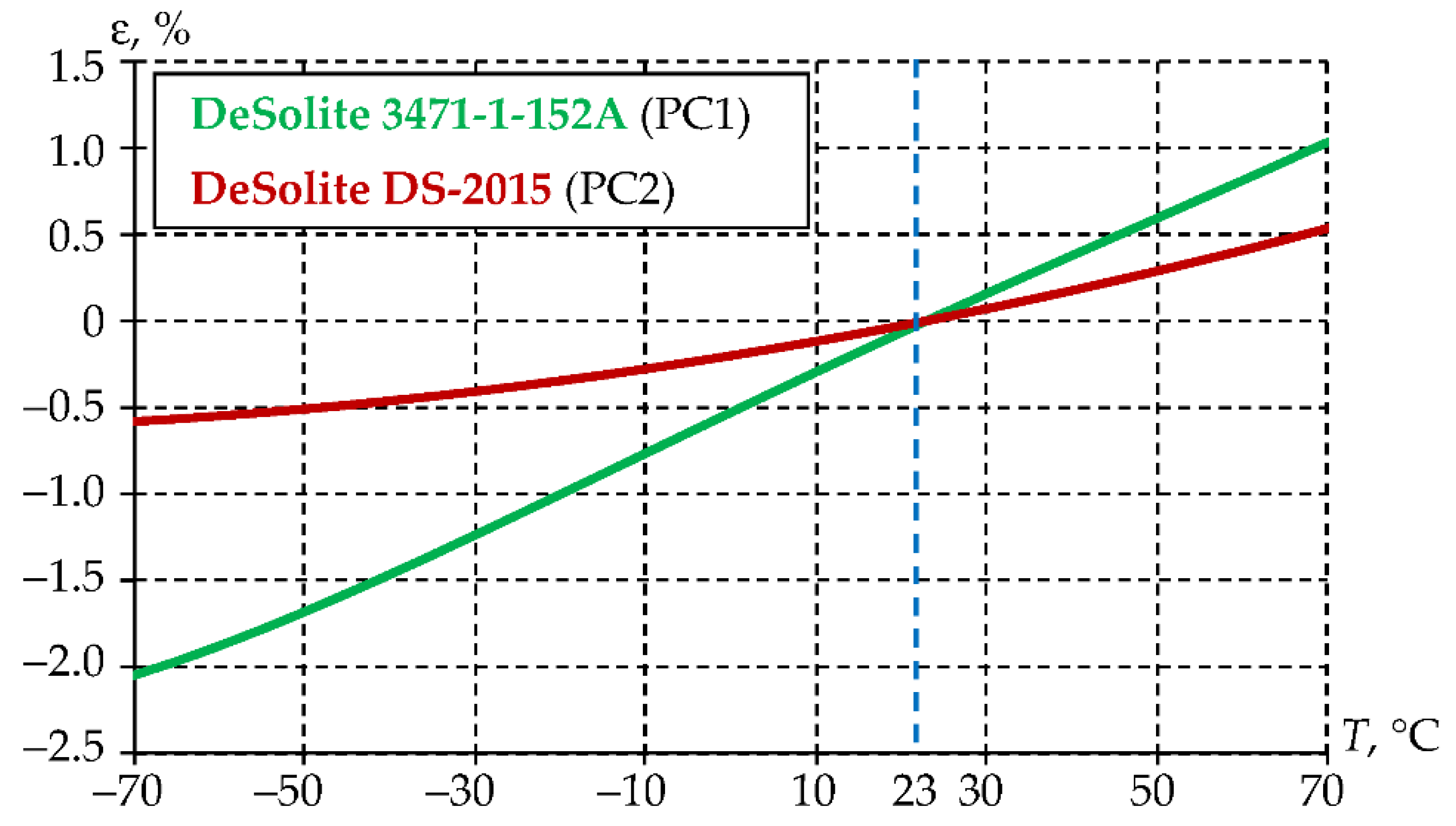

3.2.2. Dependence of Thermal Deformation on Temperature

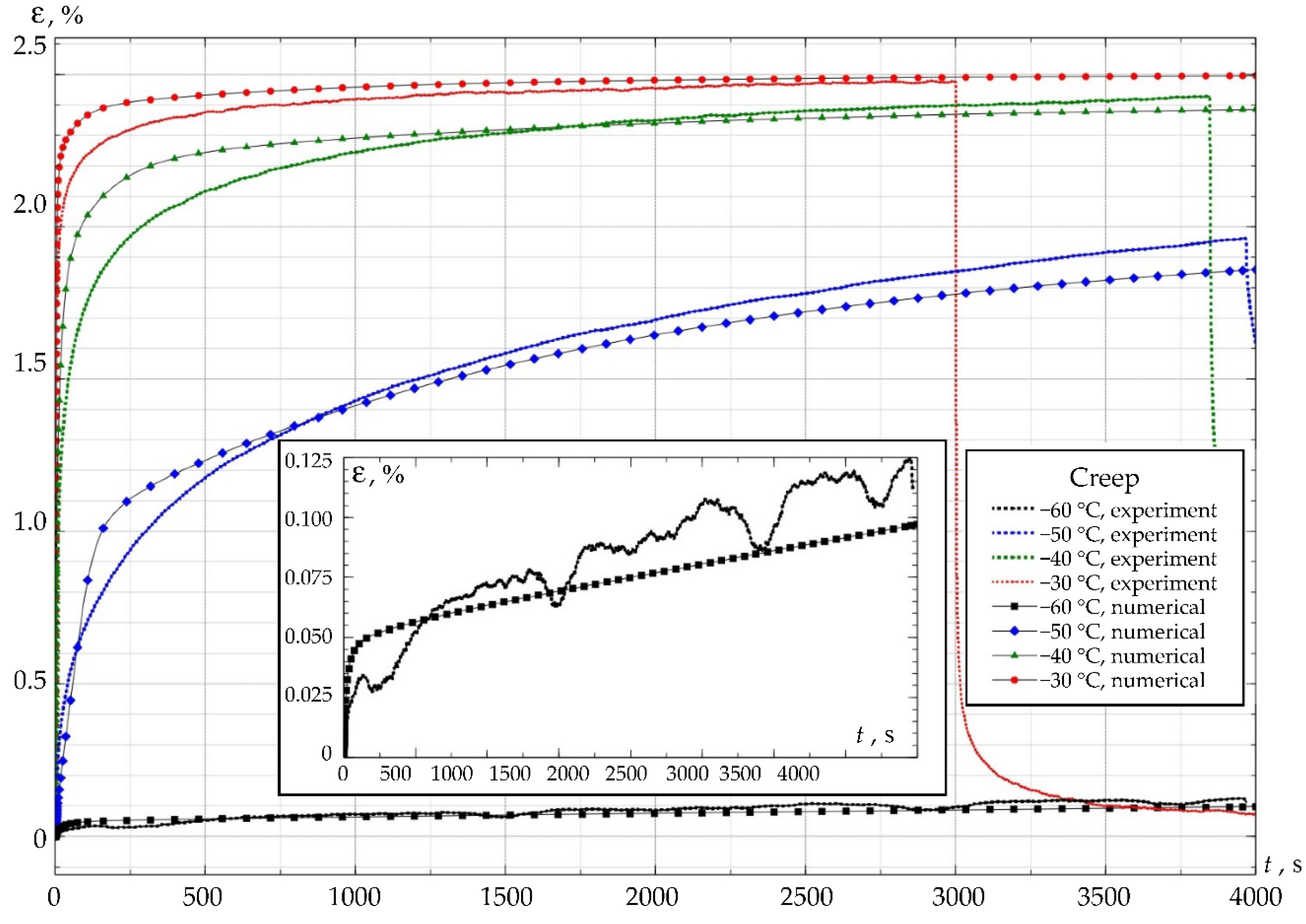

3.2.3. Verification of the Numerical Analogue of Material Behavior

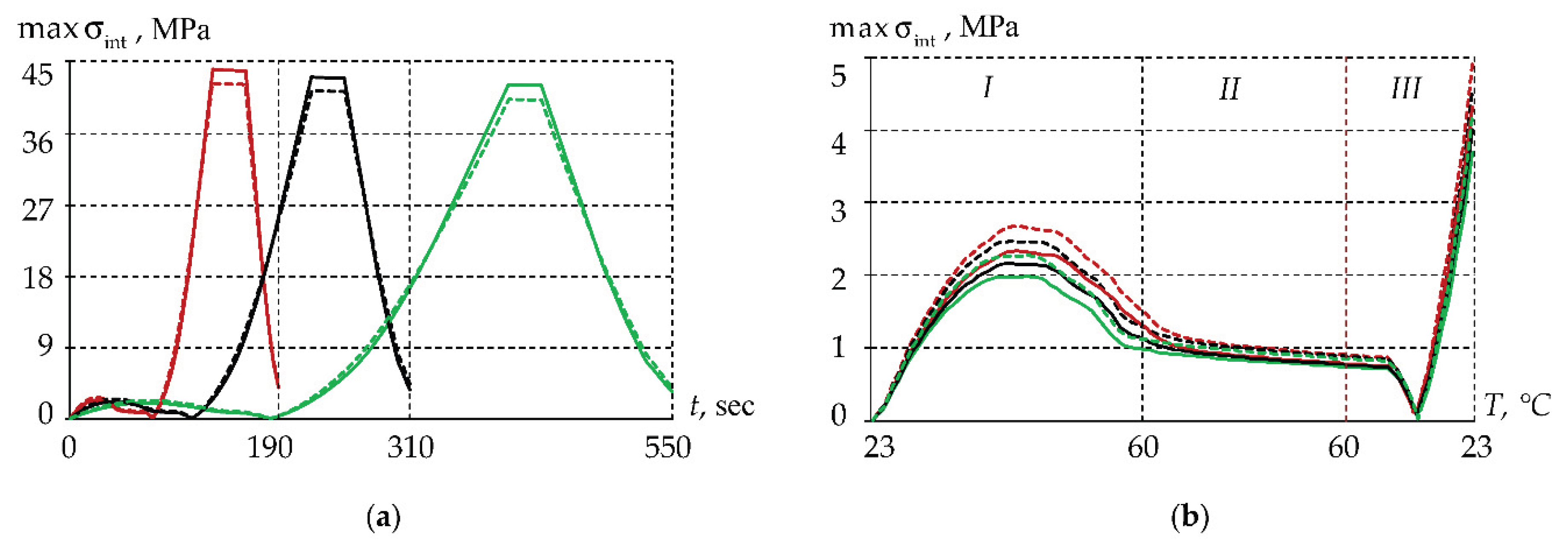

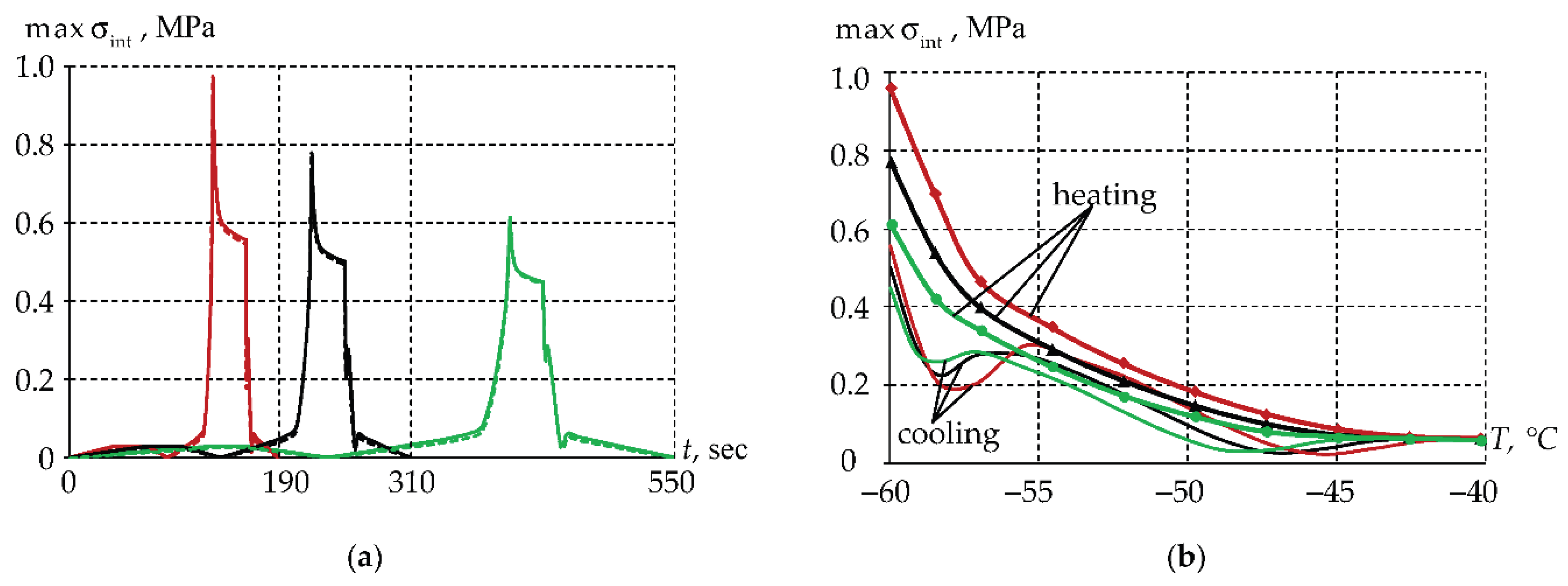

3.3. Numerical Model of Thermomechanics of Panda-Type Optical Fiber Protective Coatings

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, P.; Liu, Q.; Lu, Sh.; Xia, Y.; Wu, Q.; Fu, Y. A review of microstructured optical fibers for sensing applications. Optical Fiber Technology 2023, 77, 103277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Tam, H.-Y.; Tao, X. Multifunctional Smart Optical Fibers: Materials, Fabrication, and Sensing Applications. Photonics 2019, 6(2), 48. [CrossRef]

- Balageas, D.; Fritzen, C.; Güemes, A. Structural Health Monitoring. Wiley: Hoboken, USA, 2006.

- Koyamada, Y.; Imahama, M.; Kubota, K.; Hogari, K. Fiber-optic distributed strain and temperature sensing with very high measurand resolution over long range using coherent OTDR. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2009, 27(9), 1142–1146. [CrossRef]

- Koyamada, Y. Novel Fiber-Optic Distributed Strain and Temperature Sensor with Very High Resolution. IEICE Transactions on Communications 2006, 89-B(5), 1722–1725. [CrossRef]

- Murayama, H.; Wada, D.; Igawa, H. Structural health monitoring by using fiber-optic distributed strain sensors with high spatial resolution. Photonic Sensors 2013, 3(4), 355–376. [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Ruffin, P.; Yu, F.T. Fiber Optic Sensors, Second Edition. CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Meng, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. High sensitivity measurement of seawater velocity based on panda fiber coupled aluminum-cantilever. Optik 2024, 313, 171983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Jiang, C.; Hu, C.; Guo, Z.; Han, B.; Guo, X.; Sun, S. Ultra-sensitive strain sensor based on Sagnac interferometer with different length panda fiber. Infrared Physics & Technology 2024, 141, 105445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Chen, H.; Shi, R.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Jia, S.; Hu, J.; Li, S. Cryogenic temperature sensor based on fiber optic Sagnac interferometer with a panda polarization-maintaining fiber. Optics & Laser Technology 2025, 180, 111477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesnikova, Y.I.; Trufanov, A.N.; Kamenskikh, A.A. Analysis of the Polymer Two-Layer Protective Coating Impact on Panda-Type Optical Fiber under Bending. Polymers 2022, 14, 3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, A.; Morse, T.F. Specialty Optical Fibers Handbook; Elsevier Inc.: Butlington, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanova, I.S.; Shevtsov, D.I.; Vokhmyanina, O.L.; Saranova, I.D.; Smirnova, A.N.; Bulatov, M.I.; Pospelova, E.A.; Sharonova, Yu.O.; Dimakova, T.V.; Kashaykin, P.F.; Tomashuk, A.L.; Kosolapov, A.F.; Semenov, S.L. Experience of the Development of Heat-resistant, Radiation-resistant and Hydro-resistant Optical Fibre. Photonics 2019, 13(5), 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, R.; Pastre, A.; Griboval, A.; Andrieux, V.; Técher, K.; Laffont, G.; Lago-Rached, L. High-temperature resistant boron nitride-based coatings for specialty silica optical fibers. Optics & Laser Technology 2025, 181, 111855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, K.; Unger, S.; Aichele, C.; Lindner, F.; Grimm, S.; Litzkendorf, D.; Kobelke, J.; Bierlich, J.; Wondraczek, K.; Bartelt, H. Material and technology trends in fiber optics. Advanced Optical Technologies 2014, 3, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasik, I.; Barton, I.; Kamradek, M.; Podrazky, O.; Aubrecht, J.; Varak, P.; Peterka, P.; Honzatko, P.; Pysz, D.; Franczyk, M.; Buczynski, R. Doped and structured silica optical fibres for fibre laser sources. Optics Communications 2025, 577, 131437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, R.; Majumder, D.; Scrimshire, A.; Stone, A.; Wakelin, E.; Jones, A.H.; Wheeler, N.V.; Brooks, W.; Bingham, P.A. From acrylates to silicones: A review of common optical fibre coatings used for normal to harsh environments. Progress in Organic Coatings 2023, 180, 107557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulatov, M.I.; Sosunov, A.V.; Grigorev, N.S.; Spivak, L.V.; Petukhov, I.V. Thermal stability of carbon/polyimide coated optical fiber dried in hydrogen atmosphere. Optical Fiber Technology 2023, 81, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorebieta, J.; Pereira, J.; Franciscangelis, C.; Durana, G.; Zubia, J.; Villatoro, J.; Margulis, W. Carbon-coated fiber for optoelectronic strain and vibration sensing. Optical Fiber Technology 2024, 85, 103794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolov, A.A.; Popelka, M.; Caviasca, J.A. Lifetime prediction for polymer coatings via thermogravimetric analysis. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research 2025, 22, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. , Yang, W., Wang, M., Yu, X., Fan, J., Xiong, Y., Yang, Y., Li, L. A review of coating materials used to improve the performance of optical fiber sensors. Sensors 2020, 20(15), 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Qu, X.; She, W.; Yu, X.; Sun, Q.; Chen, H. Study of UV-curable coatings for optical fibers. Journal of Coatings Technology 1999, 71, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, L.; Yu, H.; Haroon, M.; Haq, F.; Shi, W.; Wu, B.; Wang, L. Research progress of UV-curable polyurethane acrylate-based hardening coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings 2019, 131, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canning, J.; Canagasabey, A.; Groothoff, N. UV irradiation of polymer coatings on optical fibre. Optics Communications 2002, 214, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, M.; Ledemi, Y.; Morency, S.; de Lima Filho, E.S.; Messaddeq, Y. Optical and electrical characterizations of multifunctional silver phosphate glass and polymer-based optical fibers. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 43917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamyatin, A.A.; Makovetskii, A.N.; Milyavskii, Y.S. A Procedure for Measuring the Viscosity of Formulations Based on Oligourethane Acrylates for UV-Curable Protective Coatings of Fiber Light Guides. Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry 2002, 75, 1683–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabegaeva, O.N.; Kosolapov, A.F.; Semjonov, S.L.; Ezernitskaya, M.G.; Afanasyev, E.S.; Godovikov, I.A.; Chuchalov, A.V.; Sapozhnikov, D.A. Polyamide-imides as novel high performance primary protective coatings of silica optical fibers: Influence of the structure and molecular weight. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2024, 194, 105775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Chanana, G.; Khurana, S.; Kumar, N. Introduction of Optical Fiber: Fundamentals and Applications. In: Bhardwaj, V., Kumar, S., Kishor, K., Rai, A. (eds) Optical Fiber Sensors and AI. Progress in Optical Science and Photonics 2025, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, L.; Jing, P.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S. Experimental Study on the Characterization of Aging Resistance Properties of Optical Cables in the Hydrogen-Containing Downhole Environment. Sensors 2024, 24, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.W. Polymer Materials for Optoelectronics and Energy Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesiak, M.; Poturaj, K.; Makara, M.; Mergo, P. Optical fiber with varied flat chromatic dispersion. Optical Fiber Technology 2024, 88, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Wang, C. Panda-type elliptical-core fiber with flat and low normal-dispersion at 1.5–2.5 µm. Optik 2022, 270, 169949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, K.A.M.; Omar, N.Y.M.; Zulkifli, M.I.; Yassin, S.Z.M.; Abdul-Rashid, H.A. Fabrication of Alumina-Doped Optical Fiber Preforms by an MCVD-Metal Chelate Doping Method. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervadchuk, V.; Vladimirova, D.; Gordeeva, I.; Kuchumov, A.G.; Dektyarev, D. Fabrication of Silica Optical Fibers: Optimal Control Problem Solution. Fibers 2021, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervadchuk, V.; Vladimirova, D.; Derevyankina, A. Mathematical Modeling of Capillary Drawing Stability for Hollow Optical Fibers. Algorithms 2023, 16, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, K.; Jaluria, Y. Simulation of the flow in a coating applicator for optical fiber manufacture. Computational Mechanics 2003, 31(5), 428-436. [CrossRef]

- Paek, U.C. Free drawing and polymer coating of silica glass optical fibers. Journal of Heat Transfer 1999, 121(4), 774-787. [CrossRef]

- DSM Desotech Inc. Product Data. DeSolite 3471-1-152A; DSM Desotech Inc.: Elgin, IL, USA, 2015. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1MODJPy0jBUxYzSzJmQPEaVqoyI-70dBc/view?usp=sharing (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- DSM Desotech Inc. Product Data. DeSolite DS-2015; DSM Desotech Inc.: Elgin, IL, USA, 2015. Available online: https://focenter.com/wp-content/uploads/documents/AngstromBond---Fiber-Optic-Center-AngstromBond-DSM-DS-2015-UV-Cure-Secondary-Coating-(1Kg)-Fiber-Optic-Center.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Kamenskikh, A.A.; Sakhabutdinova, L.; Strazhec, Y.A.; Bogdanova, A.P. Assessment of the Influence of Protective Polymer Coating on Panda Fiber Performance Based on the Results of Multivariant Numerical Simulation. Polymers 2023, 15, 4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startsev, O.V.; Lebedev, M.P.; Vapirov, Y.M.; Kychkin, A.K.Comparison of Glass-Transition Temperatures for Epoxy Polymers Obtained by Methods of Thermal Analysis. Mechanics of Composite Materials 2020, 56(2), 227-240. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.; Dennis, J.M.; Park, C.; Shull, K.R. Glassy dynamics of epoxy-amine thermosets containing dynamic, aromatic disulfides. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 7112−7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghori, S.W.; Rao, G.S. Mechanical and thermal properties of date palm/kenaf fiber-reinforced epoxy hybrid composites. Polymer Composites 2021, 42(5), 2217-2224. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, N.; Dyer, W.E.; Kumru, B. Exploring the Cure State Dependence of Relaxation and the Vitrimer Transition Phenomena of a Disulfide-Based Epoxy Vitrimer. Journal of Polymer Science 2025, 0, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruchinin, D.Yu.; Farafontova, E.P. Physical Chemistry of the Glassy State. Publishing House of the Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin: Ekaterinburg, Russia, 2021. (In Russian).

- Zhuravlev, V.I. Structure of Polyatomic Alcohols: The Cluster Model and Dielectric Spectroscopy Data. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2019, 93(5), 873-879. DOI 10.1134/S0036024419050376. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Tao, L.; Li, Y. Predicting Polymers’ Glass Transition Temperature by a Chemical Language Processing Model. Polymers 2021, 13, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulitin, N.V.; Shadrina, G.R.; Anisimova, V.I.; Rodionov, I.S.; Baldinov, A.A.; Lyulinskaya, Y.L.; Tereshchenko, K.A.; Shiyan, D.A. Interpretation of the Structure–Glass Transition Temperature Relationship for Organic Homopolymers with the Use of Increment, Random Forest, and Density Functional Theory Methods. Journal of Structural Chemistry 2025, 66, 1095–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Trived, A.R.; Siviour, C.R. Mechanical response of two different molecular weight polycarbonates at varying rates and temperatures. EPJ Web of Conferences 2021, 250, 06013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartenev, G.M. Relaxation Transitions in Poly (methyl methacrylate) as Shown by Dynamic Mechanical Spectroscopy, Thermostimulated Creep, and Creep Rate Spectra. Polymer Science, Series B 2001, 43(7-8), 202-207.

- Nemilov, S.V.; Balashov, Y.S. The peculiarities of relaxation processes at heating of glasses in glass transition region according to the data of mechanical relaxation spectra (Review). Glass Physics and Chemistry 2016, 42(2), 119-134. [CrossRef]

- Naymusin, I.G.; Trufanov, N.A.; Shardakov, I.N. Numerical analysis of deformation processes in the optical fiber sensors. PNRPU Mechanics Bulletin (In Russian). 2012, 1, 104–116. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Pabel, M.; Rodríguez Agudo, J.A.; Gude, M. Measuring and understanding cure-dependent viscoelastic properties of epoxy resin: A review. Polymer Testing 2022, 114, 107701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Long, S.; Zhang, H.; Yao, X. Experimental and modeling study of the viscoelastic-viscoplastic deformation behavior of amorphous polymers over a wide temperature range. Mechanics of Materials 2022, 167, 104246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Kan, Q. A viscoelastic-viscoplastic constitutive model and its finite element implementation of amorphous polymers. Polymer Testing 2023, 117, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liang, Z.; Chen, K.; Zhang, X.; Kang, G.; Kan, Q. Thermo-mechanical deformation for thermo-induced shape memory polymers at equilibrium and non-equilibrium temperatures: Experiment and simulation. Polymer 2023, 270, 125762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuryashov, D.A.; Bashkirtseva, N.Y.; Diyarov, I.N.; Philippova, O.E.; Molchanov, V.S. Temperature effect on the viscoelastic properties of solutions of cylindrical mixed micelles of zwitterionic and anionic surfactants. Colloid Journal 2010, 72(2), 230-235. [CrossRef]

- Matveenko, V.N.; Kirsanov, Y.A. Interpretation of rheological curves of polymer melts in the region of linear viscoelasticity. Cifra. Chemistry 2025, 2(5), 1 (In Russian). [CrossRef]

- Pan’kov, A.A.; Pisarev, P.V. Numerical modeling of electroelastic fields in the surface piezoelectricluminescent optical fibersensor todiagnose deformation of composite plates. PNRPU Mechanics Bulletin 2020, 2, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shardakov, I.N.; Trufanov, A.N. Identification of the Temperature Dependence of the Thermal Expansion Coefficient of Polymers. Polymers 2021, 13, 3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.Y. Rethinking and researching the physical meaning of the standard linear solid model in viscoelasticity. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures 2023, 31(11), 2370–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Determining a Prony Series for a Viscoelastic Material from Time Varying Strain Data; TM-2000-210123; NASA Langley Technical Report Server: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Alejandro, T.-R.M.; Mariamne, D.-G.; Edmundo, L.-U.L. Prony series calculation for viscoelastic behavior modeling of structural adhesives from DMA data Cálculo de Series de Prony a partir de datos de DMA para modelado de comportamiento viscoelástico de adhesives. Ingeniería Investigación y tecnología 2020, 21(2), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Mottahedi, M.; Dadalau, A.; Hafla, A.; Verl, A. (2011). Numerical Analysis of Relaxation Test Based on Prony Series Material Model. In: Fathi, M., Holland, A., Ansari, F., Weber, C. (eds) Integrated Systems, Design and Technology 2010. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Kamenskikh, A.A.; Nosov, Y.O.; Bogdanova, A.P. The Study Influence Analysis of the Mathematical Model Choice for Describing Polymer Behavior. Polymers 2023, 15, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Landel, R.F.; Ferry, J.D. The temperature dependence of relaxation mechanisms in amorphous polymers and other glass-forming liquids. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1955, 77(14), 3701-3707. [CrossRef]

- Nelder, J.A.; Mead, R. A simplex method for function minimization. The Computer Journal 1965, 7(4), 308-313. [CrossRef]

- van Krevelen, D.W.; te Nijenhuis, K. Properties of polymers (Fourth Edition) Elsevier: Boston, USA, 2009.

- Hao, J.; Lomov, S.V.; Fuentes, C.A.; van Vuure, A.W. Creep behaviour and lifespan of flax fibre composites with different polymer matrices. Composite Structures 2025, 367, 119246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschanskaya, N.N.; Yakushev, P.N.; Shpeǐzman, V.V.; Smolyanskiǐ, A.S.; Shvedov, A.S.; Cheremisov, V.G. Inhomogeneity of the strain rate of polymer materials with different supramolecular structures. Physics of the Solid State 2010, 52(9), 1972-1975.

- Shao, M.; Tam, L.; Wu, C. A universal creep model for polymers considering void evolution. Composites Part B: Engineering 2025, 297, 112280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 4.86×10−3 | 1.03×10−23 | 16 | 3.35×10−2 | 6.99×10−21 | 31 | 2.08×10−4 | 4.76×10−13 | 46 | 3.38×10−3 | 3.24×100 |

| 2 | 1.29×10−2 | 1.11×10−23 | 17 | 2.98×10−2 | 1.63×10−20 | 32 | 4.45×10−3 | 2.39×10−12 | 47 | 1.04×10−1 | 3.50×101 |

| 3 | 3.59×10−3 | 1.26×10−23 | 18 | 3.73×10−3 | 3.98×10−20 | 33 | 7.41×10−3 | 1.26×10−11 | 48 | 1.49×10−2 | 3.98×102 |

| 4 | 2.10×10−4 | 1.51×10−23 | 19 | 1.01×10−2 | 1.03×10−19 | 34 | 2.21×10−2 | 6.99×10−11 | 49 | 3.46×10−2 | 4.76×103 |

| 5 | 4.25×10−2 | 1.90×10−23 | 20 | 2.34×10−2 | 2.78×10−19 | 35 | 3.33×10−2 | 4.08×10−10 | 50 | 3.49×10−2 | 5.99×104 |

| 6 | 2.73×10−3 | 2.51×10−23 | 21 | 6.15×10−3 | 7.94×10−19 | 36 | 2.87×10−3 | 2.51×10−9 | 51 | 3.28×10−2 | 7.94×105 |

| 7 | 5.56×10−3 | 3.50×10−23 | 22 | 9.26×10−3 | 2.39×10−18 | 37 | 2.04×10−2 | 1.63E×10−8 | 52 | 3.62×10−2 | 1.11×107 |

| 8 | 2.64×10−2 | 5.14×10−23 | 23 | 2.94×10−2 | 7.55×10−18 | 38 | 7.08×10−3 | 1.11×10−7 | 53 | 3.50×10−2 | 1.63×108 |

| 9 | 5.99×10−5 | 7.94×10−23 | 24 | 5.20×10−3 | 2.51×10−17 | 39 | 2.68×10−2 | 7.94×10−7 | 54 | 3.37×10−2 | 2.51×109 |

| 10 | 7.64×10−3 | 1.29×10−22 | 25 | 2.28×10−3 | 8.80×10−17 | 40 | 6.81×10−4 | 5.99×10−6 | 55 | 1.42×10−2 | 4.08×1010 |

| 11 | 1.74×10−2 | 2.21×10−22 | 26 | 4.68×10−2 | 3.24×10−16 | 41 | 1.31×10−3 | 4.76×10−5 | 56 | 7.62×10−3 | 6.99×1011 |

| 12 | 5.14×10−3 | 3.98×10−22 | 27 | 3.96×10−2 | 1.26×10−16 | 42 | 6.85×10−3 | 3.98×10−4 | 57 | 1.86×10−3 | 1.26×1013 |

| 13 | 8.18×10−3 | 7.55×10−22 | 28 | 2.22×10−2 | 5.14×10−15 | 43 | 5.09×10−2 | 3.50×10−3 | 58 | 1.11×10−3 | 2.39×1014 |

| 14 | 1.24×10−2 | 1.51×10−21 | 29 | 2.10×10−3 | 2.21×10−14 | 44 | 6.82×10−3 | 3.24×10−2 | 59 | 3.26×10−4 | 4.76×1015 |

| 15 | 3.28×10−3 | 3.16×10−21 | 30 | 1.39×10−3 | 1.00×10−13 | 45 | 3.36×10−2 | 3.16×10−1 | 60 | 5.48×10−5 | 1.00×1017 |

| TEC | cycle 1 | cycle 2 | cycle 3 |

| 76.83% | 57.35% | 38.28% | |

| 72.49% | 54.26% | 36.31% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).