Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

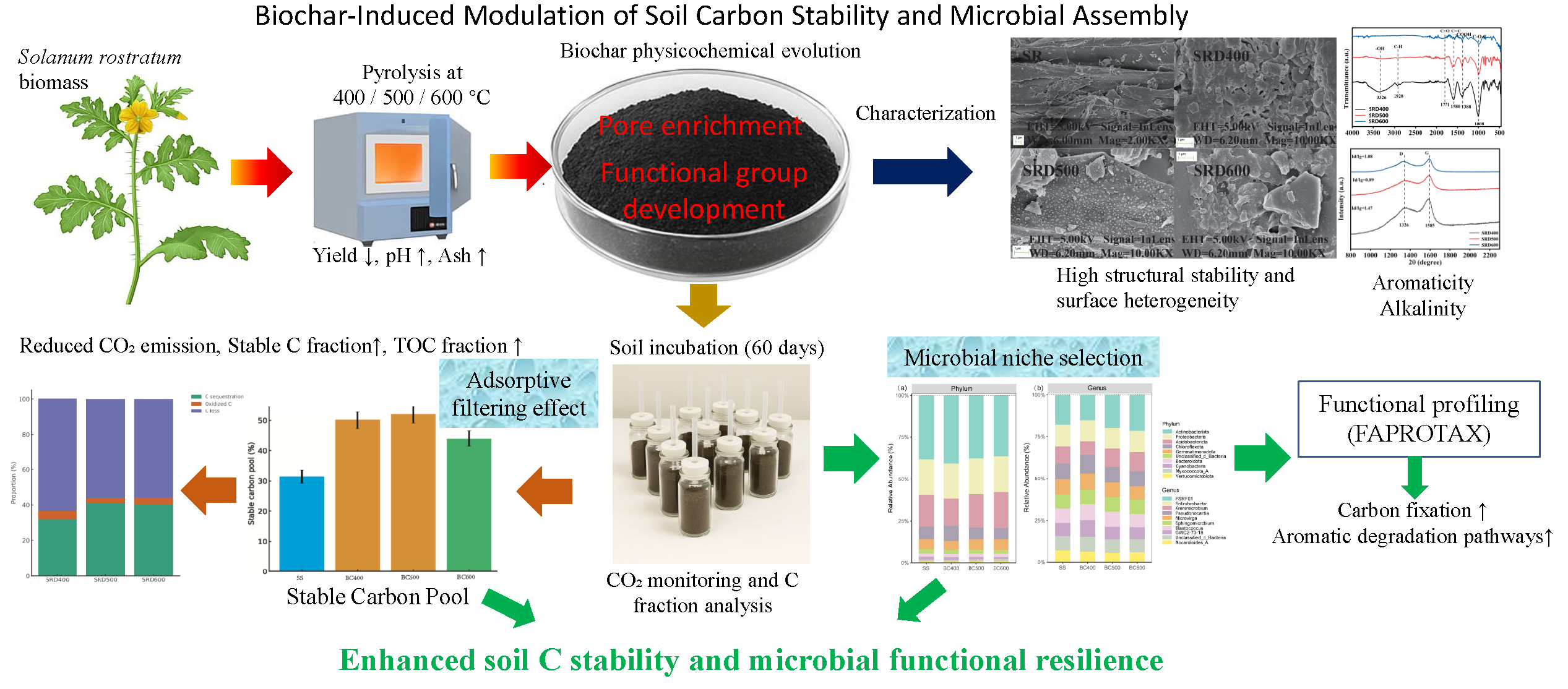

Biochar surface chemistry strongly influences the adsorption and partitioning of organic matter in soils, yet the sorption-mediated stabilization mechanisms of biochars derived from invasive plant biomass remain poorly constrained. In this study, Solanum rostratum biomass was pyrolyzed at 300–700 °C to generate biochars with distinct surface functionalities and structural characteristics. Multi-analytical characterization (FTIR, Raman, XPS, SEM) was used to quantify temperature-induced changes in aromaticity, oxygen-containing groups, and pore morphology, while soil incubation experiments assessed impacts on organic carbon fractions. High-temperature biochars showed reduced O-containing groups and enhanced aromatic condensation, indicating a shift from hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions to hydrophobic and π–π sorption mechanisms. These surface transformations were associated with increased stable carbon pools and reduced labile carbon in soil, consistent with stronger adsorption and protection of organic matter. Sequencing analysis revealed that biochar amendments significantly altered bacterial community composition and enhanced deterministic assembly processes, suggesting that microbial reorganization further reinforces sorption-driven carbon stabilization. These findings demonstrate that S. rostratum biochars possess strong sorptive properties that promote long-term carbon retention and modulate microbial ecological processes, supporting their potential use as sustainable adsorbents in soil carbon management.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil and Biomass Sampling and Preparation

2.2. Biochar Preparation

2.3. Soil Incubation Experiment

- SS: unamended soil (control);

- BC400: soil amended with SRD400 biochar at 10% (w/w);

- BC500: soil amended with SRD500 biochar at 10% (w/w);

- BC600: soil amended with SRD600 biochar at 10% (w/w).

2.4. Biochar Characterization and Physicochemical Properties

2.5. Soil Physicochemical Analyses

2.6. Microbial Community Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

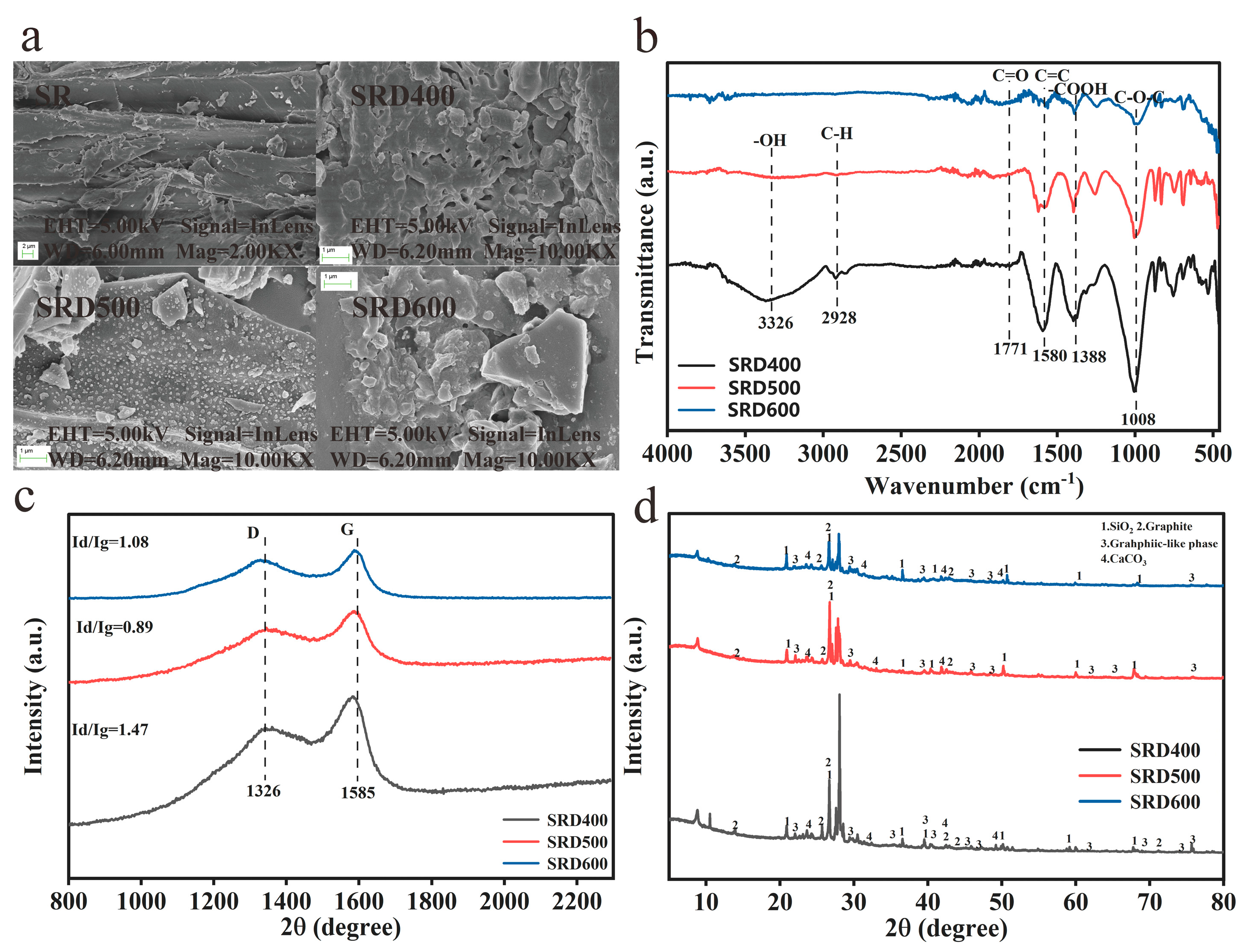

3.1. Structural Evolution of Biochars Governing Adsorption Capacity

3.1.1. Surface Morphology and Porosity Development

3.1.2. Functional Groups Relevant to Adsorption Sites

3.1.3. Aromaticity and Crystallinity as Adsorption Scaffolds

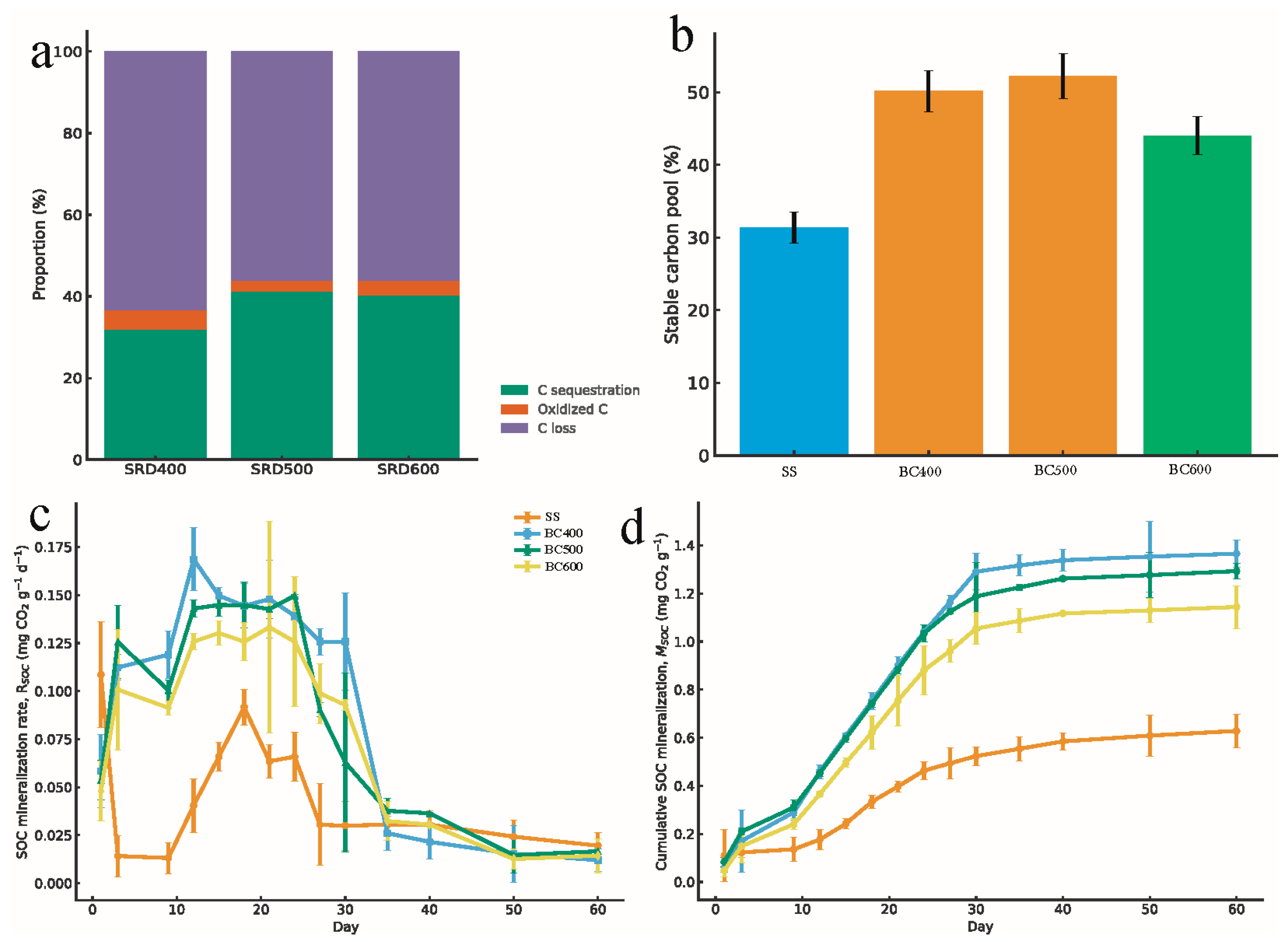

3.2. Soil Carbon Stability and Mineralization Dynamics

3.2.1. Biochar-Derived Carbon Pool Distribution

3.2.2. Stability of Biochar-Amended Soil Carbon

3.2.3. SOC Mineralization Kinetics

3.2. Soil Carbon Stability and Mineralization Dynamics

3.2.1. Biochar-Derived Carbon Pool Distribution

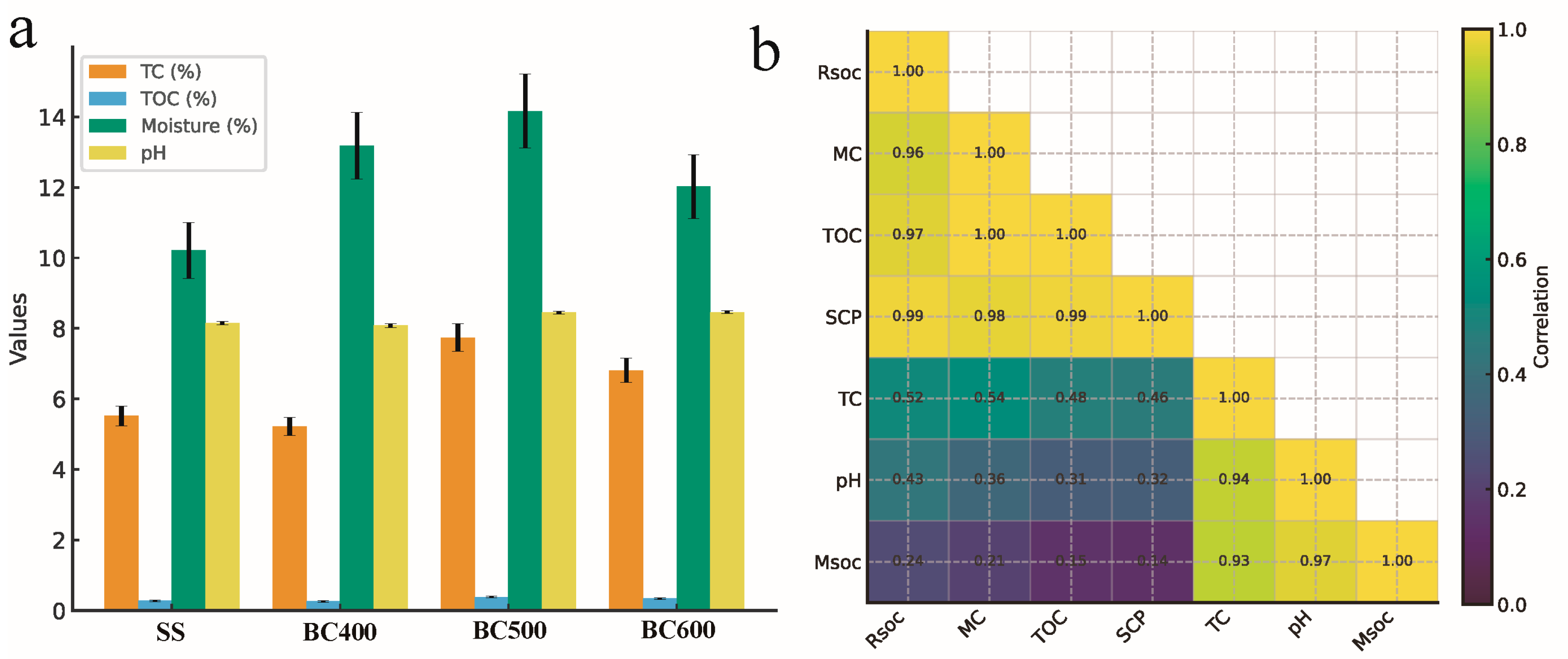

3.3. Soil Physicochemical Properties and Their Linkages to Carbon Stabilization

3.3.1. Changes in Soil TOC, pH, Moisture, and TC

3.3.2. Correlation Analysis Supports Adsorption-Mediated Stability

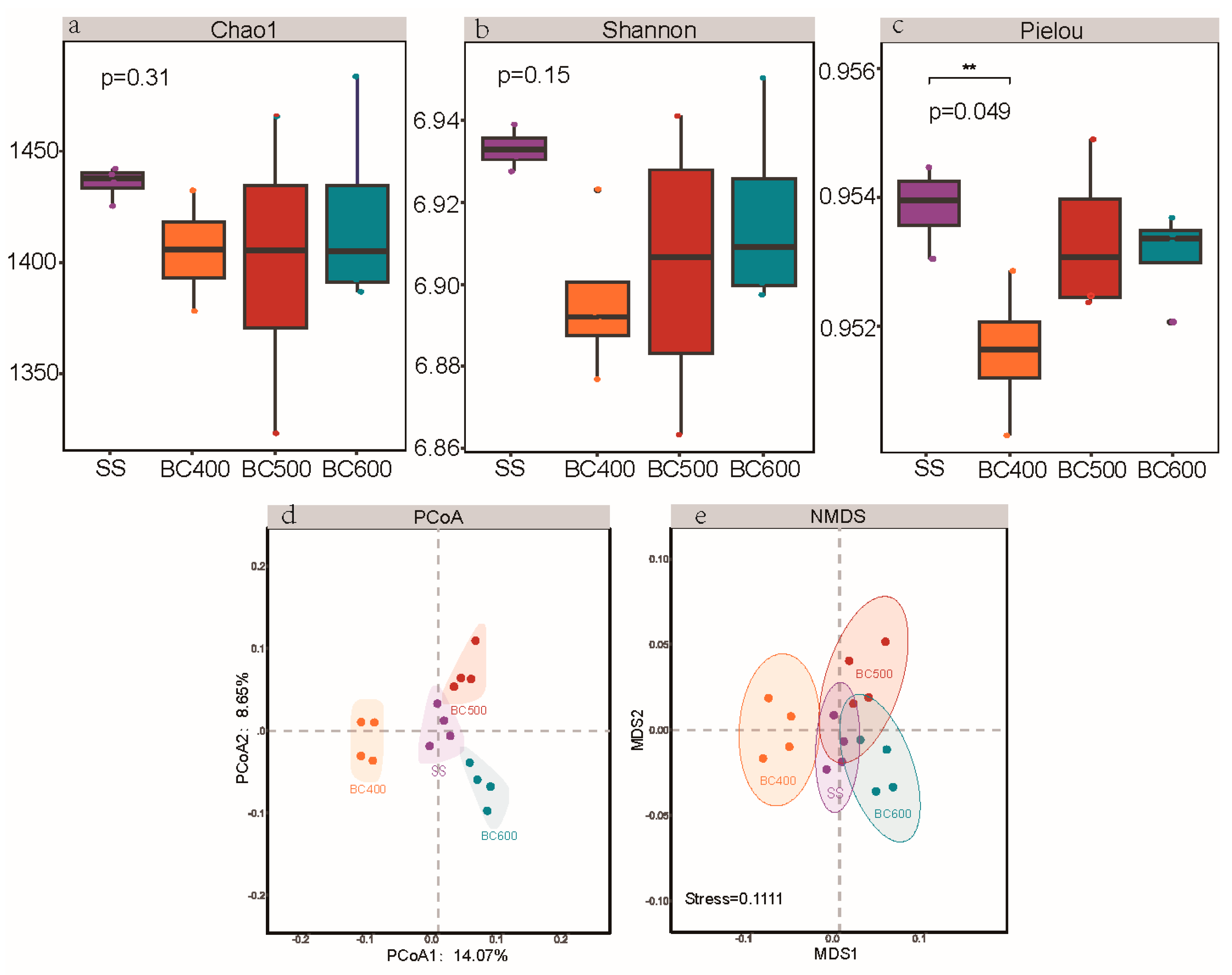

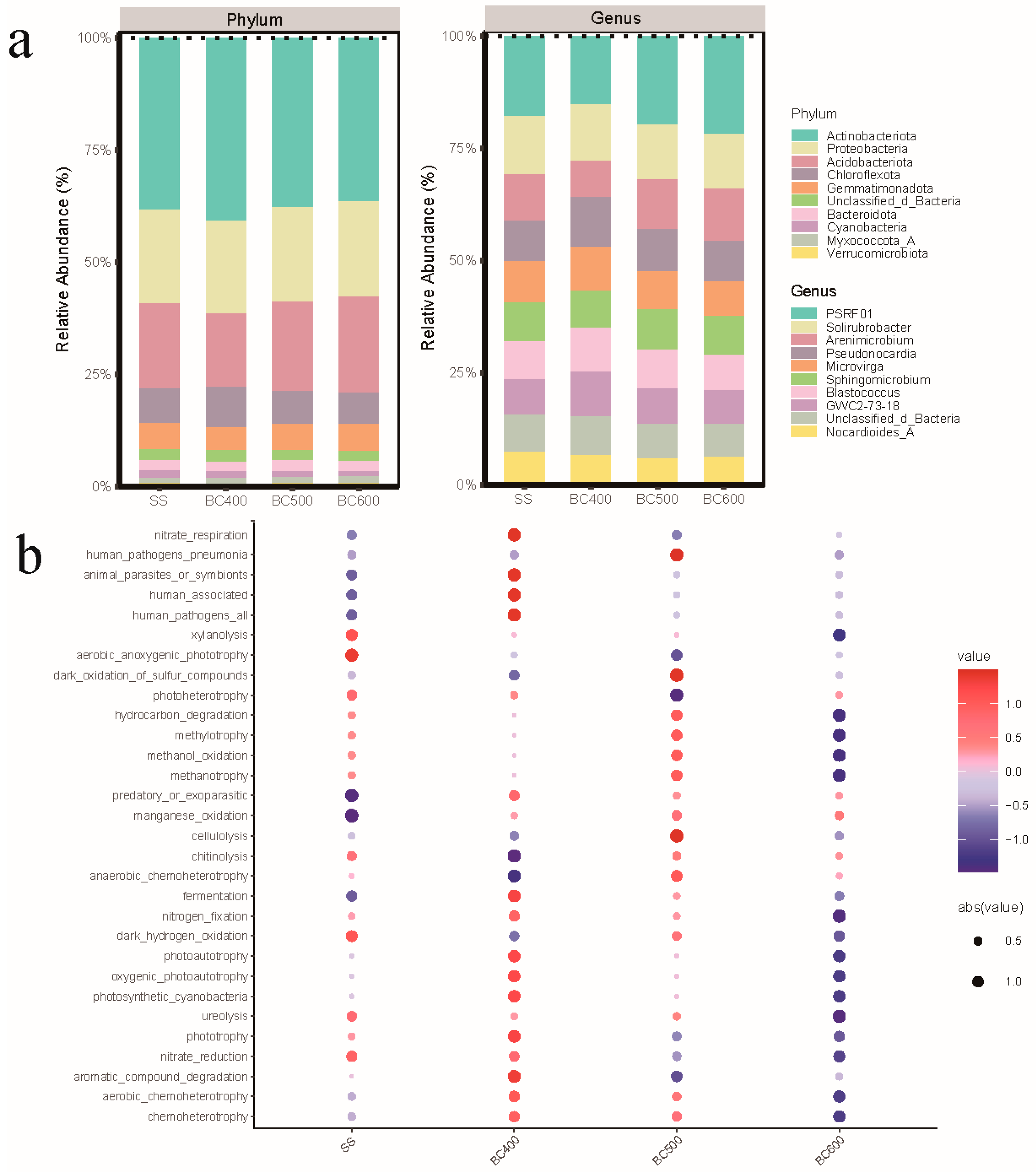

3.4. Biochar-Mediated Adsorptive Filtering of Microbial Communities

3.5. Microbial Taxonomic Shifts and Functional Responses to Biochar Amendments

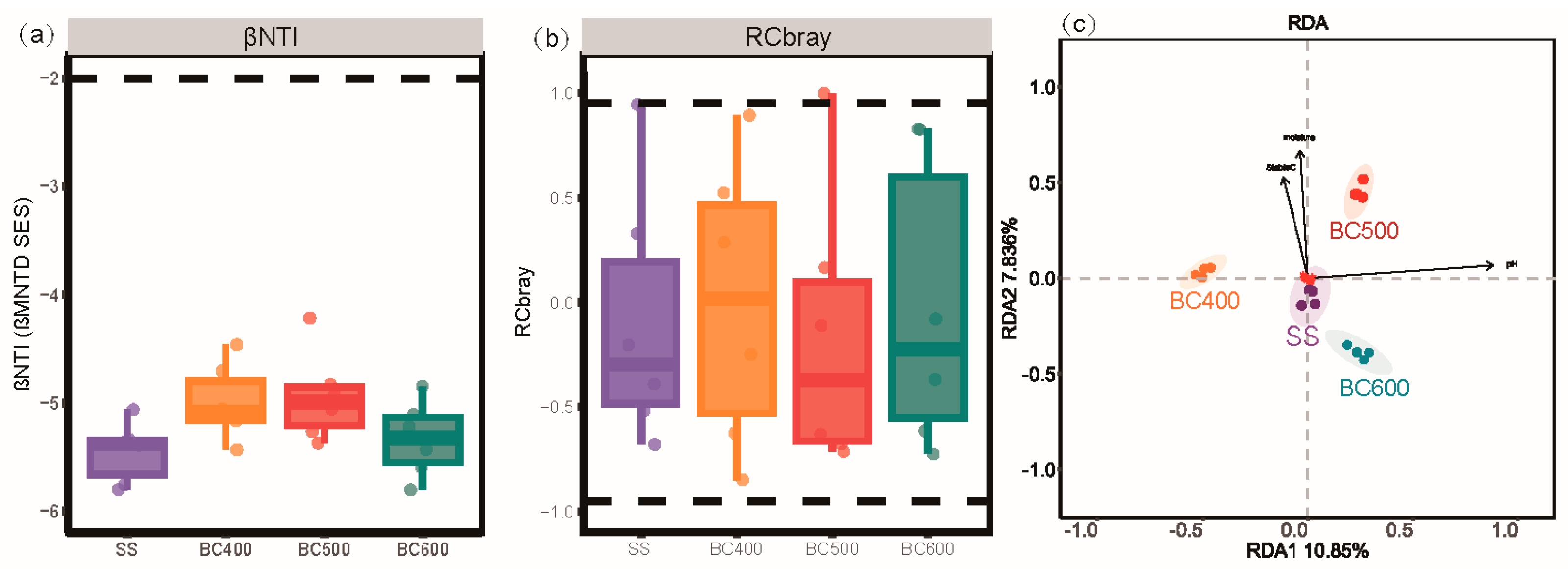

3.6. Environmental Determinants and Assembly Processes of Soil Microbial Communities

4. Discussion

4.1. Pyrolysis Temperature and Biochar Properties

4.2. Adsorption by Biochar: Surface Chemistry and Porosity

4.3. Adsorptive Filtering of Microbial Communities

4.4. Carbon Stabilization Mechanisms

4.5. Biochar-Modified Soil Environment and Community Outcomes

4.6. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stockmann, U.; Adams, M.A.; Crawford, J.W.; Field, D.J.; Henakaarchchi, N.; Jenkins, M.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Courcelles, V. de R. de; Singh, K.; Wheeler, I.; Abbott, L.; Angers, D.A.; Baldock, J.; Bird, M.; Brookes, P.C.; Chenu, C.; Jastrow, J.D.; Lal, R.; Lehmann, J.; O’Donnell, A.G.; Parton, W.J.; Whitehead, D.; Zimmermann, M. The knowns, known unknowns and unknowns of sequestration of soil organic carbon. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 164, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Divya, D.; Nath, A.; Yadav, V.S.; Singh, S.; Andleebajan, S.; Hansda, S.; Kumar, A. Carbon sequestration in agricultural soils: Strategies for climate change mitigation-A Review. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2024, 8, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Leifheit, E.F.; Lehmann, A.; Rillig, M.C. Soil organic carbon stabilization is influenced by microbial diversity and temperature. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H. Biochar and soil physical properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2017, 81, 687–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkolu, M.; Gundekari, S.; Omvesh; Palla, V. C.; Kumar, P.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Vinodkumar, T. Recent advances in biochar production, characterization, and environmental applications. Catalysts 2025, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, T.; Fernando, D.; Gunatilake, S.; Zhang, X. Biochar-based contaminant removal: A tutorial on analytical quality assurance and best practices in batch sorption. J. Chromatogr. Open 2025, 7, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Hui, K.; Zhang, X.; Yao, H. Insight into the role of the pore structure and surface functional groups in biochar on the adsorption of sulfamethoxazole from synthetic urine. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiluweit, M.; Nico, P.S.; Johnson, M.G.; Kleber, M. Dynamic molecular structure of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Bao, Z.; Meng, J.; Chen, T.; Liang, X. Biochar makes soil organic carbon more labile, but its carbon sequestration potential remains large in an alternate wetting and drying paddy ecosystem. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Gao, Q.; Sun, F.; Liu, B.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, Q. Agricultural soil microbiomes at the climate frontier: Nutrient-mediated adaptation strategies for sustainable farming. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 295, 118161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, M.; Amirahmadi, E.; Neugschwandtner, R.W.; Konvalina, P.; Kopecký, M.; Moudrý, J.; Perná, K.; Murindangabo, Y.T. The impact of pyrolysis temperature on biochar properties and its effects on soil hydrological properties. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyabama, K.; Firdous, S. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on the physicochemical properties and structural characteristics of agricultural wastes-derived biochar. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 37013–37024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, P.; Bertani, R.; Sgarbossa, P.; Bambina, P.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Raga, R.; Lo Papa, G.; Chillura Martino, D.F.; Lo Meo, P. Recent developments in understanding biochar’s physical–chemistry. Agronomy 2021, 11, 0615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.P.; Cowie, A.L.; Smernik, R.J. Biochar carbon stability in a clayey soil as a function of feedstock and pyrolysis temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11770–11778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Tan, X.; Huang, X.; Zeng, G.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, B. Biochar to improve soil fertility. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korai, S.K.; Korai, P.K.; Jaffar, M.A.; Qasim, M.; Younas, M.U.; Shabaan, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Wang, X.; Artyszak, A. Leveraging biochar amendments to enhance food security and plant resilience under climate change. Plants 2025, 14, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, B.; Zhu, L.; Xing, B. Effects and mechanisms of biochar-microbe interactions in soil improvement and pollution remediation: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Ye, J.; Lin, Y.; Wu, X.; Shu, W.; Wang, Y. Effects of co-application of biochar and nitrogen fertilizer on soil properties and microbial communities in tea plantation. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sarkar, B.; Aralappanavar, V.K.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Basak, B.B.; Srivastava, P.; Marchut-Mikołajczyk, O.; Bhatnagar, A.; Semple, K.T.; Bolan, N. Biochar-microorganism interactions for organic pollutant remediation: challenges and perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dini-Andreote, F.; Stegen, J.C.; van Elsas, J.D.; Salles, J.F. Disentangling Mechanisms That mediate the balance between stochastic and deterministic processes in microbial succession. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E1326–E1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegen, J.C.; Lin, X.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Chen, X.; Kennedy, D.W.; Murray, C.J.; Rockhold, M.L.; Konopka, A. Quantifying community assembly processes and identifying features that impose them. ISME J. 2013, 7, 2069–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Xue, P.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.; Tang, Y. Soil bacterial, fungal, and protistan assembly processes across a 1300 km climate and land-use transect. CATENA 2026, 262, 109609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuzu, S.A.; Hussain, R.S.A.; Kuchkarova, N.; Fidelis, G.D.; Zhou, S.; Habumugisha, T.; Shao, H. Buffalo-bur (Solanum rostratum Dunal) invasiveness, bioactivities, and utilization: a review. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Nassar, J.; Gal, S.; Shtein, I.; Distelfeld, A.; Matzrafi, M. Functional leaf anatomy of the invasive weed Solanum rostratum Dunal. Weed Res. 2022, 62, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, D.; Amonette, J.E.; Street-Perrott, F.A.; Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Yi, Q.; Xu, M.; Zheng, J.; Bian, R.; Zhang, X.; Pan, G. Biochar improves soil organic carbon stability by shaping the microbial community structures at different soil depths four years after an incorporation in a farmland soil. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 5, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, T.; Wang, L.; Yu, X.; Zhao, X.; Gao, W.; Van Zwieten, L.; Singh, B.P.; Li, G.; Lin, Q.; Chadwick, D.R.; Lu, S.; Xu, J.; Luo, Y.; Jones, D.L.; Jeewani, P.H. Distinct biophysical and chemical mechanisms governing sucrose mineralization and soil organic carbon priming in biochar amended soils: evidence from 10 years of field studies. Biochar 2024, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, A.R.; Gao, B.; Ahn, M.-Y. Positive and negative carbon mineralization priming effects among a variety of biochar-amended soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar physicochemical properties: pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Paiva, I.; de Morais, E.G.; Jindo, K.; Silva, C.A. Biochar N content, pools and aromaticity as affected by feedstock and pyrolysis temperature. Waste Biomass Valor. 2024, 15, 3599–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.A.; Ahmad, M.; Rafique, M.I.; Al-Wabel, M.I. Variations in composition and stability of biochars derived from different feedstock types at varying pyrolysis temperature. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2023, 22, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barszcz, W.; Łożyńska, M.; Molenda, J. Impact of pyrolysis process conditions on the structure of biochar obtained from apple waste. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Chu, Y.; Tong, Z.; Sun, M.; Meng, D.; Yi, X.; Gao, T.; Wang, M.; Duan, J. Mechanisms of adsorption and functionalization of biochar for pesticides: a review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 272, 116019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, N.; Sundaram, B. Adsorption of pollutants from wastewater by biochar: a review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 9, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H. Biochar amendments for soil restoration: impacts on nutrient dynamics and microbial activity. Environments 2025, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalu, S.; Seppänen, A.; Mganga, K.Z.; Sietiö, O.-M.; Glaser, B.; Karhu, K. Biochar reduced the mineralization of native and added soil organic carbon: evidence of negative priming and enhanced microbial carbon use efficiency. Biochar 2024, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, D.; Shen, J.; Yuan, Q.; Fan, F.; Wei, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. Biochar alters soil microbial communities and potential functions 3–4 years after amendment in a double rice cropping system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 311, 107291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palansooriya, K.N.; Wong, J.T.F.; Hashimoto, Y.; Huang, L.; Rinklebe, J.; Chang, S.X.; Bolan, N.; Wang, H.; Ok, Y.S. Response of microbial communities to biochar-amended soils: a critical review. Biochar 2019, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, B.; Gupta, S.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, R. A comprehensive review on biochar against plant pathogens: current state-of-the-art and future research perspectives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, C.; Lu, T.; Qian, H.; Liu, Y. Machine learning models reveal how biochar amendment affects soil microbial communities. Biochar 2023, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.; Metz, S.; Unrein, F.; Mayora, G.; Sarmento, H.; Devercelli, M. Environmental heterogeneity determines the ecological processes that govern bacterial metacommunity assembly in a floodplain river system. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2951–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, R.; Ge, Z.; Miao, Z. Biochar enhances soil organic carbon by stabilizing microbial necromass carbon in saline–alkaline topsoil. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.Z.; Bahar, M.M.; Sarkar, B.; Donne, S.W.; Ok, Y.S.; Palansooriya, K.N.; Kirkham, M.B.; Chowdhury, S.; Bolan, N. Biochar and its importance on nutrient dynamics in soil and plant. Biochar 2020, 2, 379–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Song, X.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Han, Z.; Gao, H.; Gao, Q.; Zha, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, G. Biochar enhances soil hydrological function by improving the pore structure of saline soil. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 306, 109170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).