1. Introduction

The production of bioethanol has grown in recent years, becoming one of the most important activities in the development of the renewable energy sector. This growth is closely tied to the value of its production and the increasing demand for renewable fuels [

1]; however, its production is associated with the generation of byproducts and waste that call its sustainability into question. Currently, agro-industrial waste has emerged as a valuable resource in the pursuit of renewable energy sources, as it can be exploited to produce a wide range of chemical components, thereby improving the sustainability of the production chain [

2].

Resulting from the distillation of the wine produced in the fermentation of sugarcane juice for bioethanol production, the byproduct fusel oil has high potential for transformation into high-value-added compounds [

3,

4]. It is primarily composed of a mixture of higher alcohols and water. Its prominent components include ethanol, isoamyl alcohol (3-methyl-1-butanol), 1-propanol, 2-propanol, butanol isomers (n-butanol, isobutanol), as well as traces of other organic compounds, such as esters and aldehydes. These components vary depending on the raw material source, fermentation and distillation conditions, and nitrogen content [

1,

3,

5,

6].

Fusel oil yields can vary between 1 to 11 L per 1,000 L of bioethanol produced [

2,

7,

8]. In countries with high bioethanol production, the potential to valorize fusel oil to produce more profitable and less polluting products represents a great opportunity to transform the bioethanol industry into a more sustainable one, with increasing circularity. Among the potential uses of fusel oil, the production of esters from its constituent alcohols emerges as an alternative for obtaining natural acetates from this low-cost agro-industrial byproduct. Esters, renowned for their flavor and fragrance properties, are valuable compounds in multiple industrial sectors, notably used in the development of fragrances, food additives, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, toiletries, and beverages [

9,

10,

11,

12].

In this context, Sánchez et al. [

13] propose two approaches for the esterification of alcohols present in fusel oil: the indirect process, which requires prior separation of individual alcohols before their esterification with carboxylic acids, and the direct process, where the complete mixture of alcohols reacts simultaneously with the carboxylic acid.

The separation of fusel oil into its constituent alcohols is achieved by batch or continuous distillation, which involves multiple columns in an energy-intensive process, since fusel oil contains several azeotropes that make separation difficult. In this sense, reactive distillation (RD) is presented as an innovative process intensification technology that offers significant advantages over conventional technologies by integrating the reaction and separation stages into a single unit. This synergy not only significantly reduces energy requirements but also avoids the difficult task of separating azeotropes, due to the consumption of components by the reaction [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Process simulation is a tool that enables the representation and analysis of complex real systems through mathematical models. Its application is particularly useful in scenarios involving multiple interrelated variables, as it facilitates conceptual design, optimization, control, and comparative evaluation of technologies. This justifies its use as a tool for assessing fusel oil valorization technologies [

19,

20].

Previous studies have proposed different alternatives for fusel oil valorization.

Table 1 presents a summary of the literature studies, highlighting the technologies employed and their main results.

These studies confirm the potential of this byproduct for obtaining high-value-added esters and highlight the need to evaluate the technical and economic efficiency of the processes involved.

This study aims to evaluate two processes for the synthesis of isoamyl acetate from fusel oil: a direct process and an indirect process using reactive distillation technology. The Aspen Hysys simulator was used to evaluate these technologies. A sensitivity analysis was performed to analyze the influence of different process variables (reflux ratio, temperature, reactant feed ratio, and feed stage) on process outputs. The economic viability of the most advantageous technology was then assessed.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on studies carried out in the literature, two technologies were evaluated for the synthesis of isoamyl acetate from fusel oil [

26]:

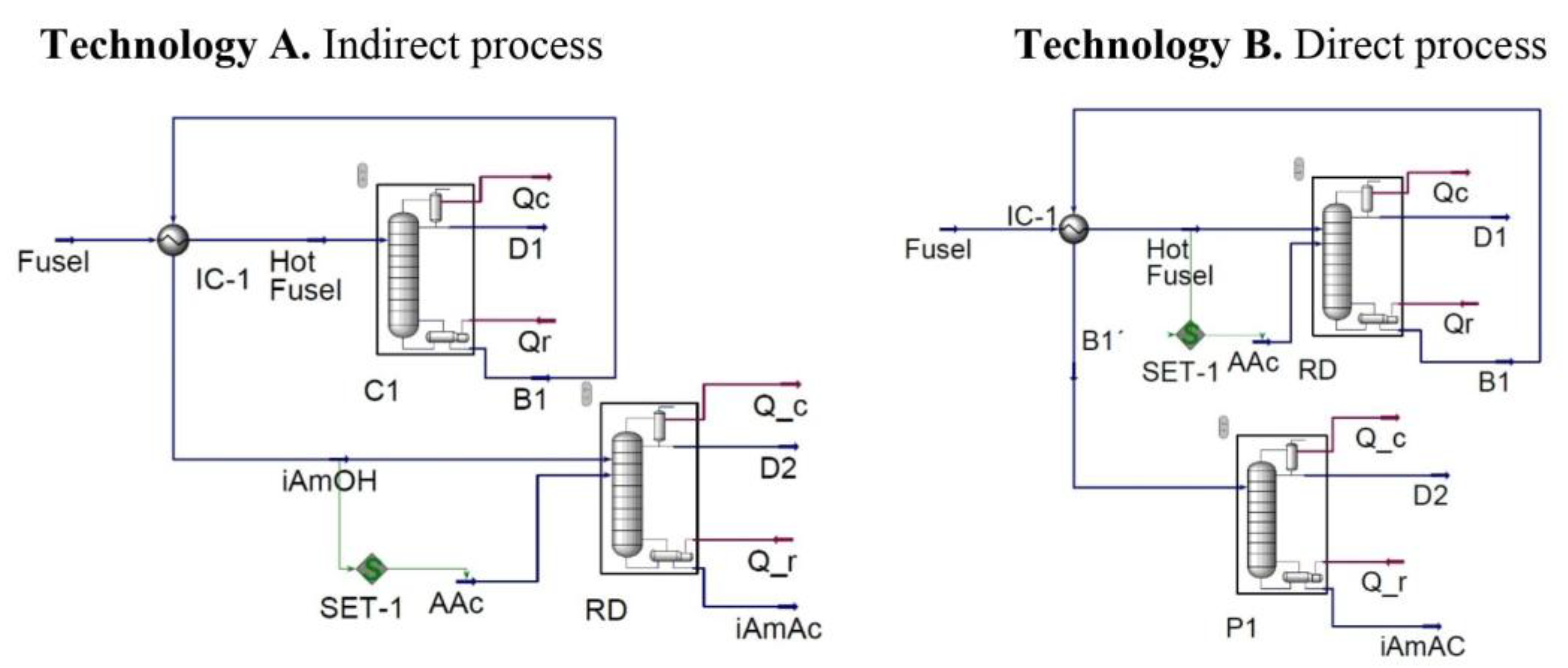

Technology A (indirect process): Separation of isoamyl alcohol followed by its esterification via reactive distillation.

Technology B (direct process): Esterification of fusel oil through reactive distillation, with subsequent purification of isoamyl acetate.

In the case of Technology A, the first step corresponds to a conventional distillation (column C1), whose objective is to separate the isoamyl alcohol in the bottom stream (B1), simultaneously removing water and other light components present in the fusel oil, which are collected in the distillate stream (D1). In the second step, the isoamyl alcohol (iAmOH stream) is fed to a reactive distillation (RD) column, where it reacts with acetic acid (AAc stream) to form the desired product, isoamyl acetate, which is obtained in the bottom stream (iAmAc).

Technology B proposes an inverse configuration: in the first step, the entire alcohol mixture from the fusel oil reacts directly with acetic acid in a reactive distillation (RD) column, generating isoamyl acetate as the main product, collected in the bottom stream (B1). This stream is subsequently treated in a second distillation column (P1), whose function is to purify the final product, obtaining a stream rich in isoamyl acetate (iAmAc).

2.1. Selecting Components and Property Packages

For this study, the Aspen Hysys v14.0 simulator was used as a tool widely recognized for its application in research, development, simulation, and design of chemical processes [

20]. For the simulation of the technologies, 31.36 kg/h of fusel was considered, whose composition in volumetric fraction was previously characterized by Aleaga et al. [

24], and is detailed in

Table 2.

For selecting thermodynamic properties based on the polar and non-electrolytic nature of fusel oil, the Nonrandom Two-Liquid (NRTL) property package was employed for the liquid phase. This model is recommended for equilibrium between water and organic substances at low pressures [

24]. For the vapor phase, due to the non-ideality of the system introduced by the dimerization of acetic acid in this phase [

27,

28], the Peng-Robinson (PR) equation of state was used. Therefore, the NRTL-PR thermodynamic model was selected to estimate the thermodynamic properties in the simulations.

2.2. Modeling and Operating Conditions

The simulated processes are structured in two main steps, as illustrated in

Figure 1. For the construction of the simulation models for both technologies, a total of three modules were used to represent the main steps of the process:

Heat Exchanger, Distillation column, and

Set.

In Technology A, the fractionation of fusel oil into its constituent alcohols is simulated using the Distillation column module (C1), and in the case of Technology B, this module simulates the isoamyl acetate purification column (P1) to obtain higher purity in the final product. The Heat Exchanger (IC-1) module is employed in both technologies to integrate the distillation bottom stream and the incoming fusel oil, allowing for a reduction in heat consumption.

The Set module (SET-1) is used in both technologies to establish a relationship between two process streams. In the case of Technology A, the molar flow rate of acetic acid was related to the molar flow rate of isoamyl alcohol separated at the bottom of the first column. In Technology B, the molar flow rate of acetic acid was related to the molar flow rate of fusel oil at the reactive distillation column inlet. In both technologies, the Set module uses a ratio of 1 between the involved streams [

24,

26].

To simulate the reactive distillation process, a system that simultaneously integrates reaction and separation stages, the Distillation column module (RD) was used. This module allows the esterification chemical reactions of the process to be associated with it. The corresponding equilibrium reactions were added, in which isoamyl (C5H11OH), isobutyl (C4H9OH), and ethyl (C2H5OH) alcohols react with acetic acid (C2H4O2) to form their respective esters, isoamyl acetate (C7H14O2), isobutyl acetate (C6H12O2), and ethyl acetate (C2H5OH), along with water. The equilibrium reactions employed were as follows:

Technology A:

C5H11OH + C2H4O2 ↔ C7H14O2 + H2O

Technology B:

C5H11OH + C2H4O2 ↔ C7H14O2 + H2O

C4H9OH + C2H4O2 ↔C6H12O2 + H2O

C2H5OH + C2H4O2 ↔ C4H8O2 + H2O

The operating conditions for the simulation of the distillation columns are detailed in

Table 3 and

Table 4. In the case of Technology A, the feed conditions of the reactive column and the reactive stages correspond to those reported by Sánchez et al. [

26] for the synthesis of isoamyl acetate by indirect process (esterification of isoamyl alcohol with acetic acid).

In the case of Technology B, the operating conditions of the reactive distillation column were taken from the study conducted by Aleaga et al. [

24], in which the authors evaluated a reactive distillation process for the synthesis of esters from the direct process (esterification of the mixture of fusel alcohols with acetic acid).

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the influence of key operating parameters on process efficiency, product purity, and energy consumption. To do this, one operating variable was modified while holding all other parameters constant.

For the Technology A distillation column, three main variables were considered. Firstly, the influence of the fusel oil feed temperature (53 to 93 °C) on energy consumption was analyzed. Secondly, the effect of the reflux ratio (RR) (1 to 8) on the purity, mass flow rate, and recovery of isoamyl acetate, and energy consumption was evaluated. Finally, the influence of the fusel oil feed location, between stages 11 and 20, was studied to determine its effect on product purity and flow rate.

For the Technology A reactive column, the RR was varied between 7.5 and 11.5. The acid/alcohol molar ratio (1:1 to 2:1) was also analyzed to determine its influence on the flow rate and purity of isoamyl acetate. The influence of the feed location of the reactants within the reactive zone (stages 5 to 20) was evaluated by varying its position between stages 3 and 13. First, the acid feed stage was modified, keeping the alcohol feed constant (stage 3). Subsequently, the alcohol feed was shifted between the same stages, keeping the acid feed constant (stage 13).

In the case of Technology B, for the reactive column, the variation of the RR (1 to 8) was studied, the feed temperature of the fusel oil stream was evaluated (50 to 90 °C), keeping the acid temperature constant at 90 °C. The acid/fusel molar ratio (1:1 to 2:1) and the effect of the feed of the reactant mixture were analyzed, varying between stages 11 and 20 within the reactive zone (trays 5 to 20). Finally, in the purification column, the influence of the RR (7.5 to 11.5) and the isoamyl acetate feed stage (stages 20 and 28) was evaluated.

Sensitivity analysis does not allow for determining the effect of interactions associated with different values of the variables. To overcome this limitation, a Taguchi L9 fractional experimental design matrix was constructed to assess the impact of interactions at different levels of the independent variables (-1: pessimistic extreme value, 0: normal value, 1: optimistic extreme value)[

29].

Table 5 shows the Taguchi orthogonal arrangement used for each case with the corresponding factors and levels.

2.4. Economic Assessment

Based on the results obtained from the simulator, an economic evaluation of the most favorable technology for the process was conducted using Aspen Economic Analyzer v14.0. Capital expenditures (CAPEX) and operating expenses (OPEX) were calculated, in addition to economic indicators such as net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), and payback period (PP). For this purpose, an operating time of 8,000 h/y, a useful life of 10 years, and a general discount rate of 12% were considered. A cost of 13 US

$/kg for acetic acid [

30], a fusel oil price of 0.072 US

$/L [

31], and a selling price of isoamyl acetate of 38 US

$/L were considered. The unit cost of utility services (TUC) was calculated based on the cost of heating (LP steam) and cooling water.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results Obtained from the Simulation

The results were analyzed based on key process variables, such as reactant conversion, component distribution, and process operating conditions.

Table 6 and

Table 7 present the main results obtained for Technologies A and B, respectively.

Technology A produces 19.69 kg/h of isoamyl acetate with 99.05%w/w purity, with a total consumption of cooling water and heating of 123.59 MJ/h and 126.95 MJ/h, respectively. In terms of fractionation, it is possible to recover 95.39% of isoamyl alcohol in the bottom stream of column C1 with a mass composition of 0.9616, which demonstrates an efficient recovery of the compound of interest. In parallel, the most volatile compounds such as ethanol, water, and isobutanol are concentrated in the overhead stream (D1), indicating the correct separation of the fusel oil components.

In the reactive distillation column, an isoamyl alcohol conversion of 90.98% is achieved, demonstrating a favorable reaction under the established operating conditions. In addition, a bottom stream with a purity of 99.05%w/w isoamyl acetate by mass is obtained, confirming the efficiency of the process both in terms of conversion and quality of the final product.

Technology B produces 22.27 kg/h of isoamyl acetate with 98.10%w/w purity, with a total consumption of cooling water and heating of 87.6 MJ/h and 88.22 MJ/h, respectively. Despite the complexity of the multicomponent mixture, this technology allows for effective conversion of isoamyl alcohol in the reactive column, achieving 98.84% conversion and a mass fraction of 0.9382 of isoamyl acetate in the bottom stream. These results demonstrate a highly favorable reaction, even in the presence of other compounds in the feed stream. Furthermore, a conversion of 96.23% of ethanol and 71.67% of isobutanol is achieved.

In the purification stage, 81.04% of the isoamyl acetate is recovered, with a purity of 98.10%w/w at the bottom. However, despite the purification process, 1-pentanol is not completely separated, with a residual mass fraction of 0.0179. This limitation can be attributed to the proximity of its normal boiling point (138 °C) to that of isoamyl acetate (142 °C), which makes its separation by conventional distillation difficult.

After comparing both technologies, it is observed that Technology B, although producing the ester with a slightly lower purity (98%w/w) than Technology A (99%w/w), achieves a higher productivity (22.27 kg/h compared to 19.69 kg/h of Technology A), which represents an approximate increase of 13.10%. In terms of energy requirements, Technology B presents lower consumption, with reductions of 29% in the case of cooling water and 31% for heating, so it is considered more advantageous from a technical and operating point of view.

These results were compared with previous fusel oil valorization studies involving direct and indirect processes (

Table 1). Based on the results obtained in this work (Technology A), isoamyl alcohol was separated using a single distillation column, achieving a recovery of 95.39% and a purity of 0.9616 w/w. Although these values are slightly lower than those reported by Mendoza-Pedroza et al. [

2] and Montoya et al. [

22], the purity obtained is 17.55% higher than that reported by Ferreira et al. [

21]. It is worth noting that the configuration proposed in this study presents lower operational complexity compared to previous works, since it dispenses with additional units such as decanters or multiple columns. The high purity achieved (over 96%) demonstrates that even with a simpler configuration, it is possible to obtain a high-quality product.

Comparing the results obtained in the present work with the reactive distillation process proposed by Ali et al. [

14], a slightly lower purity of 99.05% w/w is evident, which is still high and suitable for industrial applications. Furthermore, in both cases, water was completely removed from the bottom stream, and in the proposed configuration, only a small amount of 1-pentanol was present (mass fraction of 0.0095). Similarly, the thermal profile in which the reactive column operates (96.53 to 141.4 °C) is in a similar range to that of the study by Ali et al. [

14] (85 to 140 °C). Regarding the conversion of isoamyl alcohol, the results also show very similar values; in Technology A of the present work, a value of 90.98% was achieved, very close to the 91% reported in the comparative study.

On the other hand, in the esterification process simulated by Patil and Kulkarni [

23], although the reported conversion was higher than that obtained in this work (90.98%), the purity achieved in this investigation (99.05%) was considerably higher, demonstrating greater effectiveness in terms of product purification within the reactive distillation process. Regarding the thermal profile, the operating temperatures obtained by Patil and Kulkarni [

23] are in a range of 90 to 140 °C, which is comparable with the interval recorded in this investigation (96.53 to 141.4 °C).

Compared to the direct esterification technology proposed by Aleaga et al. [

24], the Technology B developed in this work showed superior performance, achieving a conversion of 98.84% for isoamyl alcohol. Furthermore, despite the presence of other alcohols in the feed, high conversions (ethanol: 96.24%; isobutanol: 71.79%) and a recovery of 82.44% were achieved in the purification step, with a final purity of isoamyl acetate of 98.10%. These results demonstrate the greater efficiency of the proposed system in terms of both reaction and separation.

On the other hand, compared to the technology developed by Patidar and Mahajani [

25] this study showed a significantly higher conversion of isoamyl alcohol (98.84%), reaching a mass fraction of 93.82% of isoamyl acetate at the bottom of the reactive column, and a final purity of 98.10% with the purification step, a value that is not far from that obtained by those authors.

Based on the simulation results, an analysis of the concentration profiles for each technology was performed. The composition profiles associated with each column and their discussion are included in the Supplementary Material.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis allowed us to establish the best operating conditions for each technology. A detailed analysis of the process sensitivity to each parameter and its corresponding graphical behavior is presented in the Supplementary Material.

For Technology A, the results of the sensitivity analysis indicate that in column C1, the feed should be carried out in stage 11, since greater purity and product recovery are obtained, and an RR of 1 should be employed. For column RD, the acid/alcohol molar ratio corresponds to a 1:1 ratio; the alcohol and the acid feed should be located in stage 3 and between stages 8 and 10, respectively, to achieve high purity (>99%) and higher isoamyl acetate productivity (19.49 kg/h).

In the case of Technology B, the RD column must operate with an acid/fusel oil molar ratio of 1:1, the reactant feed must occur between stages 14 and 18, and the fusel oil stream feed temperature must be increased to 90 oC to reduce heating consumption and work at an RR of 1. Finally, for column P1, the proposed RR value must be maintained (RR=7.5), since increasing it does not improve purity, but does significantly increase energy consumption, and it is not recommended to vary the feed stage (stage 20) because it harms product recovery.

The analysis of the experimental data, based on Taguchi L9 arrays, allowed the identification of the main effects and the evaluation of interactions between the process operating parameters.

Table 8 shows the matrix to evaluate the interactions between the variables for column C1 of Technology A. It shows that the least favorable combinations of values result in case 3, where the lowest flow rate and purity are obtained. It is also evident that achieving a purity greater than 96% in the final product requires greater energy consumption, driven by an increase in the RR.

Table 9 shows the matrix to evaluate the interactions between the variables for column RD of Technology A. From

Table 9, it can be concluded that the least favorable combination of values is found in cases 3, 6, and 9, where the lowest purities are obtained in the final product. In contrast, the most favorable scenario is case 1, with a high purity value and adequate flow rate, and moderate energy consumption compared to the other cases.

Table 10 shows the matrix to evaluate the interactions between the variables for column RD of Technology B. From

Table 10, it can be concluded that the most favorable combination is found in case 1, where adequate purity and flow rate values are obtained in the final product with moderate energy consumption compared to the other cases.

Finally, it is possible to observe in

Table 11, which shows the Taguchi L9 matrix for the analysis of column P1of Technology B, that in all the scenarios analyzed, the purity is greater than 98%. However, the least favorable combinations are cases 3 and 6, with the lowest acetate flow rates. Case 1 is the most favorable, with the highest flow rate and lowest consumption.

This analysis demonstrated that achieving optimal process conditions requires evaluating the combination of several operating factors, as the process does not depend solely on the individual effects of its operating parameters. The analysis identified the most influential factors and their interactions in each configuration studied.

The designs of column C1 of Technology A show that the RR is the factor with the greatest impact on the purity, flow rate, recovery, and energy consumption of the process. Achieving purities above 96% requires a high RR, which leads to higher energy consumption. It was identified that total energy consumption is primarily influenced by the interactions between the feed stage and the feed temperature, while purity is influenced by the interactions between the feed stage and the feed temperature, and between the feed temperature and the RR. The analysis indicates that, in cases where the feed temperature is high with a low RR, lower purities and flow rates are obtained due to the interaction between the RR and the feed temperature. For mass flow rate and isoamyl alcohol recovery, interactions exist among all the analyzed parameters.

For the RD column, the design shows that the acid/alcohol feed molar ratio is the factor that most influences product purity; feeding the acid above the stoichiometric 1:1 ratio is not favorable for the process. It was identified that the acetate purity and mass flow rate are influenced by interactions between the RR and the feed stages (acid and alcohol). In the case of mass flow rate, it is also conditioned by interactions between the feed molar ratio and the feed stages (acid and alcohol). For total energy consumption, the only variable that does not show interactions is the RR. The analysis indicates that the combination of low RR levels, the acid/alcohol ratio, and feed stages provides the best balance between purity and energy consumption.

For the RD column of Technology B, the design also confirms that the acid/fusel oil molar ratio is the most influential factor in achieving high purities. It was identified that the mass flow rate is conditioned by the interaction between all the analyzed factors. In the case of purity, the interactions identified were the combination of the RR and the feed stage and temperature. In the case of energy consumption, the interaction between the acid/fusel oil feed molar ratio and the feed stage and temperature was observed, while the RR was the only factor that did not interact with any other. The interactions between these parameters demonstrated that cases 1, 4, and 7 are the only ones that achieve a purity above 90%.

Finally, in column P1, the most influential parameter was RR. It was identified that the combination of RR and the feed stage factors exhibits interactions for all the analyzed response variables. The interaction between RR and the feed stage demonstrated that combining a low RR with the most suitable feed stage can result in a more efficient process than simply increasing RR.

The graphs showing the interactions between the factors analyzed for each response variable of both technologies are presented in the Supplementary Material.

3.3. Economic Assessment

Based on the results obtained in the simulation, the technical-economic analysis of Technology B was carried out, identified as the most advantageous to evaluate its economic viability. The analysis was carried out considering two alternatives: one in which the acetic acid that constitutes the original process is not recirculated (Alternative 1) and another in which the recirculation of the acid is considered (Alternative 2). The results obtained from the economic analysis are shown in

Table 12.

As can be seen, the technology analyzed is economically advantageous, reaching an NPV of US$3,587,110. The IRR (38.95%) presents values above the rate at which the company can obtain funds (interest rate of 12%), recovering the investment in a period of 5.05 years, which demonstrates its economic feasibility.

Regarding operating costs, the annual OPEX was estimated at US$5,054,440/year for a production capacity of 178,160 kg/year of isoamyl acetate, corresponding to a unit operating cost of US$28.37/kg of isoamyl acetate. Raw material costs represent 75.56% of total OPEX (US$3,819,010/year), while utilities consumption only represents 1.16% (US$58,627/year). This is because the cost of acetic acid (US$3,798,263/year ) accounts for more than 99% of raw material costs, indicating that the economic viability of the process is critically influenced by acid costs in the market.

Considering the recirculation of acetic acid in the process, this would allow the recovery of 16 kg/h of this compound, representing a 43.81% reduction in net acid consumption and significantly reducing associated costs. The estimated economic savings in raw material costs would amount to US$1,680,000/year, which would consequently help increase the economic viability of the process. In this case, the annual OPEX is reduced by 29.56% compared to Alternative 1, and the unit operating cost is US$19.99/kg of isoamyl acetate.

4. Conclusions

In this work, a study was carried out to evaluate two processes for the synthesis of isoamyl acetate from fusel oil (A. Indirect process, B. Direct process) using the Aspen Hysys v14.0 simulator. Both processes were favorable for obtaining isoamyl acetate. However, Technology B leads to the best configuration, with reductions of 29% in the case of cooling water consumption and 31% in the case of heating compared to the other technology, obtaining a mass flow rate of isoamyl acetate of 22.18 kg/h with a purity of 98%.

Sensitivity analysis determined the best operating conditions for each technology. For Technology A, column C1 performed best with a feed in stage 11 and RR=1, while for the RD column, a molar ratio of 1:1, alcohol feed in stage 3, and acid in stages 8-10 was used, achieving >99% purity and 19.49 kg/h of productivity. For Technology B, the RD column showed greater efficiency with a 1:1 ratio, feed between stages 14 and 18, and a fusel feed temperature of 90 °C, while column P1 must maintain RR=7.5 and acetate feed in stage 20.

The Taguchi L9 fractional experimental design allowed for the identification of the influence of the combination of operating factors on acetate purity and flow rate, recovery, and energy consumption of the process, as well as facilitating the combination of favorable and unfavorable scenarios. In Technology A, column C1 exhibited its worst performance in case 3, while in column RD, cases 3, 6, and 9 were the least favorable, and case 1 was the most favorable. In Technology B, in both column RD and column P1, case 1 showed the best performance, while cases 3 and 6 registered the least favorable results. The factors that most influenced Technology A were the RR and the acid/alcohol feed ratio, while for Technology B, they were the acid/fusel oil feed ratio and the RR.

Based on the optimal configuration, a technical-economic analysis was performed, proving to be economically feasible, achieving an NPV of 3,587,110 US$, an IRR of 38.95%, and a PP of 5.05 years. If acid recirculation is considered in the process, an NPV of 7,232,950 US$, an IRR of 56.34%, and a PP of 3.56 years are obtained.

The results of this work contribute to the development of technological alternatives for the production of isoamyl acetate from fusel oil, contributing to its valorization as a raw material and improving the circularity of sugarcane mills. Furthermore, it demonstrates the potential of reactive distillation as a process intensification strategy for synthesizing esters by integrating reaction and separation in a single unit, which favors the energy and operational efficiency of the system.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1. Mass fraction profiles in the liquid phase for each column of Technology A (a,b) and B (c,d); Figure S2. Influence of temperature variation (a), RR (b,c,d,e), and feed stage (f,g) in column C1 of Technology A; Figure S3. Influence of the variation of the RR (a,b,c), the acid/alcohol ratio (d,e), and the reactant feed stage (f,g,h,i) of the RD column of Technology A; Figure S4. Influence of the variation of the RR temperature (a,b,c), feed temperature (d), acid/fusel oil feed ratio (e,f), reactant feed stage (g,h) of the RD column of Technology B; Figure S5. Influence of the variation of the RR (a,b,c,d) and feed stage (e,f) in column P1 of Technology B; Figure S6. Interactions between the operating parameters of column C1 of Technology A for purity (a), recovery (b), mass flow (c) and total energy consumption (d); Figure S7. Interactions between the operating parameters of column RD of Technology A for purity (a), mass flow (b) and total energy consumption (c); Figure S8. Interactions between the operating parameters of column RD of Technology B for purity (a), mass flow (b) and total energy consumption (c); Figure S9. Interactions between the operating parameters of column P1 of Technology B for purity (a), recovery (b), mass flow (c) and total energy consumption (d).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.G.A., A.C.L., L.Z.C., L.V.P., M.A.S.S.R., C.B.B.C. and O.P.O.; methodology, C.L.G.A., A.C.L., L.Z.C., L.V.P., M.A.S.S.R., C.B.B.C. and O.P.O.; software, C.L.G.A.; validation, C.L.G.A.; formal analysis, C.L.G.A., A.C.L., L.Z.C., L.V.P., M.A.S.S.R., C.B.B.C. and O.P.O.; investigation, C.L.G.A., A.C.L., L.Z.C., L.V.P., M.A.S.S.R., C.B.B.C. and O.P.O.; data curation, C.L.G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.G.A., A.C.L.; C.B.B.C. and O.P.O., writing—review and editing, C.L.G.A., A.C.L., L.V.P., M.A.S.S.R., C.B.B.C. and O.P.O.; visualization, C.L.G.A.; supervision, A.C.L.; C.B.B.C. and O.P.O.; project administration, C.B.B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Move La America Program – Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Move La America Program – Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES), Process 88881.996448/2024-01, for providing financial support to one of them (C.L.G. Aleaga) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Processes 309026/2022-9, 406544/2023-9, and 307705/2025-0. During the preparation of this study, the authors used Grammarly in order to verify possible English typos. The authors have re-viewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RD |

Reactive distillation |

| C1 |

Distillation column |

| P1 |

Purification column |

| B1 |

Bottom stream of distillation column C1 |

| D1 |

Distillate stream of distillation column C1 |

| AAc |

Acetic acid |

| iAmOH |

Isoamyl alcohol |

| iAmAc |

Isoamyl acetate |

| NRTL |

Nonrandom Two-Liquid model |

| PR |

Peng-Robinson |

| RR |

Reflux ratio |

| CAPEX |

Capital expenditures |

| OPEX |

Operating expenses |

| NPV |

Net present value |

| IRR |

Internal rate of return |

| PP |

Payback period |

| TUC |

Utility services |

References

- García-Aleaga, C.L.; Cruz-Llerena, A.; Pérez-Ones, O.; de Cárdenas, L.Z.; Fernández-Casiis, M. Potencialidades del aceite fusel. Tecnologías para su revalorización. Bionatura. 2024, 9, 91-112. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Pedroza, J.J.; Sánchez-Ramírez, E.; Segovia-Hernández, J.G.; Hernández, S.; Orjuela, A. Recovery of alcohol industry wastes: Revaluation of fusel oil through intensified processes. Chem. Eng. Process. 2021,163, 108329. [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.L.B.; da Cunha, G.N.; dos Santos, P.; Meireles, M.A.A.; Martínez, J. Fusel oil: Water adsorption and enzymatic synthesis of acetate esters in supercritical CO2. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2018, 142, 22-31. [CrossRef]

- Neagu, M.; Cursaru, D.L.; Missyurin, A.; Goian, O. Efficient separation of isoamyl alcohol from fusel oil using non-polar solvent and hybrid decanter–distillation process. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9954. [CrossRef]

- Studziński, W.; Podczarski, M.; Piechota, J.; Buziak, M.; Yakovenko, M.; Khokha Y. Recovery of Natural Pyrazines and Alcohols from Fusel Oils Using an Innovative Extraction Installation. Molecules. 2025, 30, 3028. [CrossRef]

- Marinho, L.H.N.; Aragão, F.V.; de Genaro Chiroli, D.M.; Zola, F.C.; Tebcherani, S.M. A systematic review of fusel oil as a renewable biofuel: Challenges, opportunities, and circular economy integration. Fuel. 2025, 402, 135924. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, R.; Bento, H.B.S.; Reis, C.E.R.; Bôas, R.N.V.; de Freitas, L.; Carvalho, A.K.F., de Castro, H.F. Biolubricant Production from Stearic Acid and Residual Secondary Alcohols: System and Reaction Design for Lipase-Catalyzed Batch and Continuous Processes. Catal. Lett. 2022, 152, 547-58. [CrossRef]

- Erol, D.; Yaman, H.; Doğan, B.; Yeşilyurt, M.K. The assessment of fusel oil in a compression-ignition engine in the perspective of the waste to energy concept: investigation of the performance, emissions, and combustion characteristics. Biofuels. 2022, 13, 1147-64. [CrossRef]

- Massa, T.B.; Raspe, D.T.; Feiten, M.C.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; da Silva, C.D. Fusel Oil: Chemical Composition and an Overview of Its Potential Application. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2023, 34, 153-66. [CrossRef]

- SÁ, A.G.A; de Meneses, A.C.; de Araújo, P.H.H.; de Oliveira, D. A review on enzymatic synthesis of aromatic esters used as flavor ingredients for food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals industries. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, B.; Deniz, İ.; Fazlı, H.; Gürsoy, S.; Yarıcı, T.; Bengü, B. Synthesis of iso-amyl ester rosin and its evaluation as an alternative to paraffin in medium density fiberboard production. Bioresources. 2024, 19, 2077-91. [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.V.; Kongparakul, S.; Karnjanakom, S.; Reubroycharoen, P.; Guan, G.; Chanlek, N.; Samart, C. Selective production of green solvent (isoamyl acetate) from fusel oil using a sulfonic acid-functionalized KIT-6 catalyst. Mol. Catal. 2020, 484, 110724. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.A.; Sánchez, O.A.; Orjuela, A.; Gil, I.D.; Rodríguez, G. Vapor–Liquid Equilibrium for Binary Mixtures of Acetates in the Direct Esterification of Fusel Oil. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2017, 62, 11-9. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Hossain, S. K.; Asif, M. Dynamic modeling of the isoamyl acetate reactive distillation process. Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 2017, 19, 59-66. [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, D.A.; Fernandez, B.; Morante, R.; Rivera, H.R.; Simeon, K.; Lopez, E.C.R. Recent Advances in Reactive Distillation. Eng. Proc. 2023, 56, 99. [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.A.; Muthia, R.; Pazmiño-Mayorga, I.; Harmsen, J.; Jobson, M.; Gao, X. Conceptual methods for synthesis of reactive distillation processes: recent developments and perspectives. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2024, 99, 1263-90. [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.A. Novel Catalytic Reactive Distillation Processes for a Sustainable Chemical Industry. Top. Catal. 2019, 62, 1132-48. [CrossRef]

- Missyurin, A.; Cursaru, D.L.; Neagu, M.; Nicolae, M. Hybrid Process Flow Diagram for Separation of Fusel Oil into Valuable Components. Processes. 2024, 12, 2888. [CrossRef]

- Valverde, J.L.; Ferro, V.R.; Giroir-Fendler, A. Automation in the simulation of processes with Aspen HYSYS: An academic approach. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2023, 31, 376-88. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Llerena, A.; Pérez-Ones, O.; de Cárdenas, L.Z.; de los Ríos, J.L.P. Techno-Economic Analysis of Vinasse Treatment Alternatives Through Process Simulation: A Case Study of Cuban Distillery. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2021, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.C.; Meirelles, A.J.; Batista, E.A. Study of the fusel oil distillation process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 2336-51. [CrossRef]

- Montoya, N.; Córdoba, F.; Trujillo, C.; Gil, I.; Rodríguez, G. Fusel oil process separation. In AIChE Annual Meeting, American Institute of Chemical Engineers, Minneapolis, USA, 2011. p.p 332-7.

- Patil, K.D.; Kulkarni, B.D. Modeling and simulation for reactive distillation process using aspen plus. In National Symposium on Reaction Engineering (NSRE), Raipur, India, 2010. p.p 199-209.

- García-Aleaga, C.L.; Cruz-Llerena, A.; Pérez-Ones, O.; de Cárdenas, L.Z. Destilación reactiva para la revalorización de aceite de fusel: caracterización de muestras y simulación de procesos. Rev. Cen. Azúcar. 2024, 51, e1085-07.

- Patidar, P.; Mahajani, S.M. Esterification of fusel oil using reactive distillation–Part I: Reaction kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 207, 377-87. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.A.; Gil, I.D.; Rodríguez, G. Fluid phase equilibria for the isoamyl acetate production by reactive distillation. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2020, 518, 112647. [CrossRef]

- Patidar, P.; Mahajani, S. M. Esterification of fusel oil using reactive distillation. Part II: Process alternatives. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 16637-47. [CrossRef]

- González, D.R.; Bastidas, P.; Rodríguez, G.; Gil, I. Design alternatives and control performance in thepilot scale production of isoamyl acetate viareactive distillation. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2017, 123, 347-59. [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.; Anuradha, N. Use of orthogonal arrays and design of experiment via Taguchi L9 method in probability of default. Account. 2018, 4, 113-22. [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Fernandez, D.; Proano-Aviles, J. Techno-economic analysis of the production of acetic acid via thermochemical processing of residual woody biomass in Ecuador. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2022, 16, 335-48. [CrossRef]

- Eustácio, R.S; da Silva, L.F.; Souza, C.; Mendes, M.F.; Neto, M.R.F.; Pereira, C.S.S. Simulação do processo de destilação da mistura etanol-óleo fúsel utilizando o simulador de processos ProSimPlus. Rev. Eletrônica Teccen. 2018, 11, 61-7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).