Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cu’s Role in Cancer and Cancer Treatments

2.1. Role of Cu in Tumor Angiogenesis

2.2. Role of Cu in Tumor Metastasis

2.3. Role of Cu in Intrinsic and Acquired Chemotherapy Resistance

3. Can Copper be Considered a Metal with the Potential to Augment Anticancer Therapeutics?

3.1. Cu Ionophores

3.2. Cu Chelators

4. Copper’s Role in the Immune System

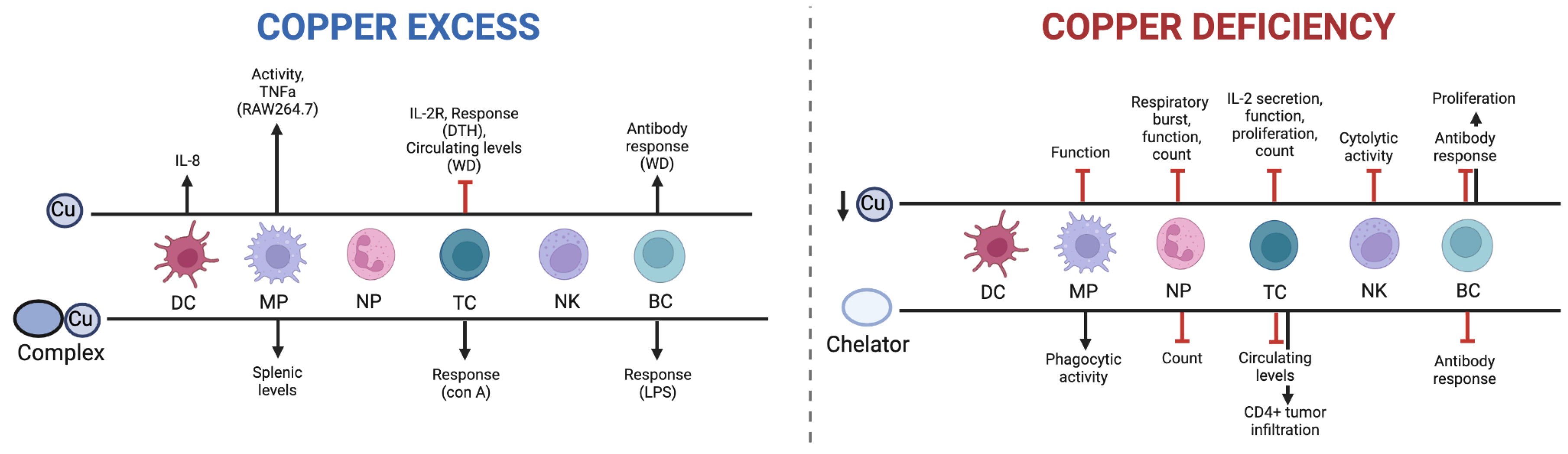

4.1. Cu and the Immune System

4.1. Dietary Cu Deficiency

4.2. Cu Chelation

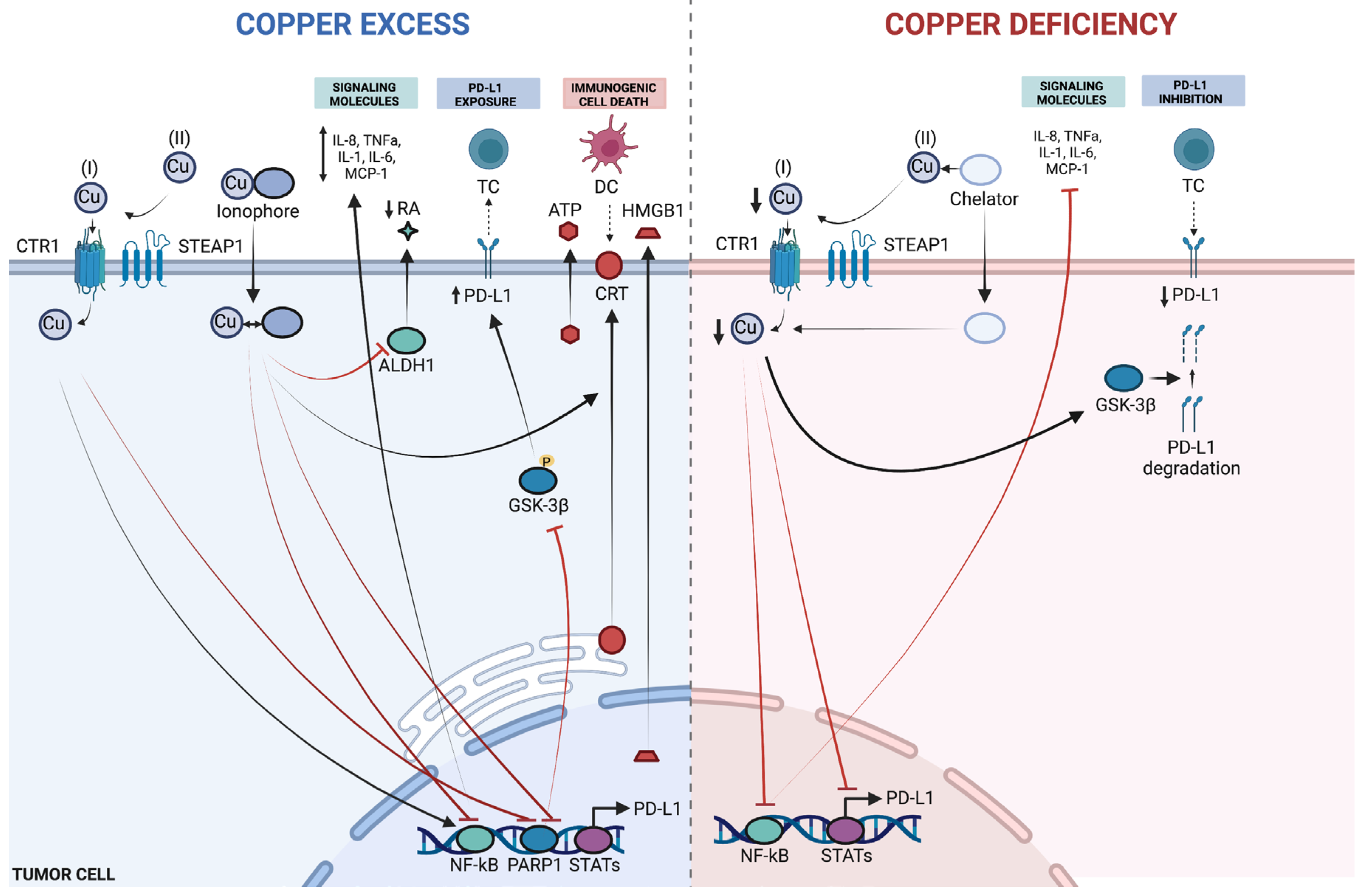

4.3. Cu and Immunogenic Cell Death of Cancer Cells

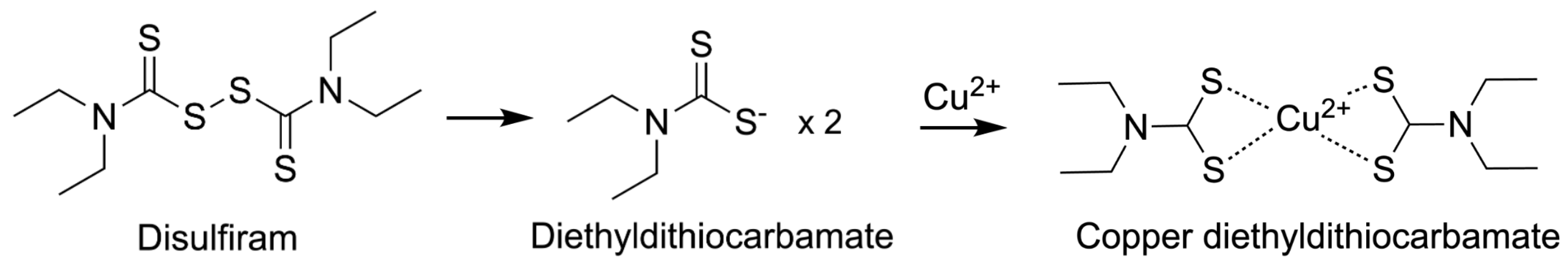

4.4. Approved ICD-Inducing Treatments with an Emphasis on Disulfiram

5. Cu, Cu-Complexes and PD-L1

5.1. Cu-Based Nanomedicines

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crans, D.C.; Kostenkova, K. Open questions on the biological roles of first-row transition metals. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.N.; Chang, C.J. Metalloallostery and Transition Metal Signaling: Bioinorganic Copper Chemistry Beyond Active Sites. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, T.; Davis, C.I.; Brady, D.C. Copper biology. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R421–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turski, M.L.; Brady, D.C.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, B.-E.; Nose, Y.; Counter, C.M.; et al. A Novel Role for Copper in Ras/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 1284–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, T.; Posimo, J.M.; Gudiel, A.A.; Cicchini, M.; Feldser, D.M.; Brady, D.C. Copper is an essential regulator of the autophagic kinases ULK1/2 to drive lung adenocarcinoma. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelièvre, P.; Sancey, L.; Coll, J.-L.; Deniaud, A.; Busser, B. The Multifaceted Roles of Copper in Cancer: A Trace Metal Element with Dysregulated Metabolism, but Also a Target or a Bullet for Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, D.; Brayton, D.; Shahandeh, B.; Meyskens; Frank, L. ; Farmer, P.J. Disulfiram Facilitates Intracellular Cu Uptake and Induces Apoptosis in Human Melanoma Cells. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 6914–6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardito, S.; Bassanetti, I.; Bignardi, C.; Elviri, L.; Tegoni, M.; Mucchino, C.; et al. Copper Binding Agents Acting as Copper Ionophores Lead to Caspase Inhibition and Paraptotic Cell Death in Human Cancer Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6235–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P.; Coy, S.; Petrova, B.; Dreishpoon, M.; Verma, A.; Abdusamad, M.; et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science 2022, 375, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.-Y.; Rui, W.; Chen, S.-T.; Chen, H.-C.; Liu, X.-W.; Huang, J.; et al. Process of immunogenic cell death caused by disulfiram as the anti-colorectal cancer candidate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 513, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Huang, H.; Pan, C.; Mei, Z.; Yin, S.; Zhou, L.; et al. Disulfiram/Copper Induces Immunogenic Cell Death and Enhances CD47 Blockade in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Yang, W.; Toprani, S.M.; Guo, W.; He, L.; DeLeo, A.B.; et al. Induction of immunogenic cell death in radiation-resistant breast cancer stem cells by repurposing anti-alcoholism drug disulfiram. Cell Commun. Signal 2020, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voli, F.; Valli, E.; Lerra, L.; Kimpton, K.; Saletta, F.; Giorgi, F.M.; et al. Intratumoral Copper Modulates PD-L1 Expression and Influences Tumor Immune Evasion 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Guo, L.; Zhang, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, K.; Yan, J.; et al. Disulfiram combined with copper induces immunosuppression via PD-L1 stabilization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 2442–2455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Mi, M.; Wen, Q.; Wu, G.; Zhang, L. Disulfiram Improves the Anti-PD-1 Therapy Efficacy by Regulating PD-L1 Expression via Epigenetically Reactivation of IRF7 in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Front Oncol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persichini, T.; Percario, Z.; Mazzon, E.; Colasanti, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Musci, G. Copper Activates the NF-κB Pathway In Vivo. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2006, 8, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.-C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, L.-H.; Li, Y.; Fu, S.-Y.; Xue, X.; Jia, L.-N.; et al. Targeting ALDH2 with disulfiram/copper reverses the resistance of cancer cells to microtubule inhibitors. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 362, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Lagos, K.; Benson, M.J.; Noelle, R.J. Retinoic Acid in the Immune System. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2008, 1143, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelievre, P.; Sancey, L.; Coll, J.L.; Deniaud, A.; Busser, B. The Multifaceted Roles of Copper in Cancer: A Trace Metal Element with Dysregulated Metabolism, but Also a Target or a Bullet for Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, B.L. Biochemistry of copper. Med. Clin. North. Am. 1976, 60, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apelgot, S.; Coppey, J.; Fromentin, A.; Guille, E.; Poupon, M.F.; Roussel, A. Altered distribution of copper (64Cu) in tumor-bearing mice and rats. Anticancer. Res. 1986, 6, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, R.J.; Weiss, N.S.; Daling, J.R.; Rettmer, R.L.; Warnick, G.R. Cancer risk in relation to serum copper levels. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 4353–4356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Shukla, V.K.; Vaidya, M.P.; Roy, S.K.; Gupta, S. Serum trace elements and Cu/Zn ratio in breast cancer patients. J. Surg. Oncol. 1991, 46, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.; Haddad, H.; Wassan Al-Elwee, M. Diagnostic values of copper, zinc and copper/zinc ratio compared to histopathological examination in patients with breast tumors. Bas J Surg 2010, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalioth, E.J.; Schenker, J.G.; Chevion, M. Copper and zinc levels in normal and malignant tissues. Cancer 1983, 52, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, S.L.; Sky-Peck, H.H. Comparison between concentrations of trace elements in normal and neoplastic human breast tissue. Cancer Res. 1984, 44, 5390–5394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.P.; Fofana, M.; Chan, J.; Chang, C.J.; Howell, S.B. Copper transporter 2 regulates intracellular copper and sensitivity to cisplatin. Metallomics 2014, 6, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinov, B.; Tsachev, K.; Doganov, N.; Dzherov, L.; Atanasova, B.; Markova, M. The copper concentration in the blood serum of women with ovarian tumors (a preliminary report). Akush Ginekol (Sofiia) 2000, 39, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yaman, M.; Kaya, G.; Simsek, M. Comparison of trace element concentrations in cancerous and noncancerous human endometrial and ovary tissues. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2007, 17, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhou, Y.C.; Zhou, B.; Huang, Y.C.; Wang, G.Z.; Zhou, G.B. Systematic analysis of concentrations of 52 elements in tumor and counterpart normal tissues of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 7720–7727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, M.; Arroyo, M.; Cerdàn, F.J.; Muñoz, M.; Martin, M.A.; Balibrea, J.L. Serum and tissue trace metal levels in lung cancer. Oncology 1989, 46, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xu, H.; Xue, S.; Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; et al. Combined effects of serum trace metals and polymorphisms of CYP1A1 or GSTM1 on non-small cell lung cancer: a hospital based case-control study in China. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011, 35, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T.; Matsuno, K.; Kawamoto, T.; Mitsudomi, T.; Shirakusa, T.; Kodama, Y. Efficiency of serum copper/zinc ratio for differential diagnosis of patients with and without lung cancer. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1994, 42, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaris N, Ahmad. Distribution of trace elements like calcium, copper, iron and zinc in serum samples of colon cancer – A case control study. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2011, 23, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juloski, J.T.; Rakic, A.; Ćuk, V.V.; Ćuk, V.M.; Stefanović, S.; Nikolić, D.; et al. Colorectal cancer and trace elements alteration. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 59, 126451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepien, M.; Jenab, M.; Freisling, H.; Becker, N.P.; Czuban, M.; Tjønneland, A.; et al. Pre-diagnostic copper and zinc biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanni, A.; Licciardello, L.; Trovato, M.; Tomirotti, M.; Biraghi, M. Serum Copper and Ceruloplasmin Levels in Patients with Neoplasias Localized in the Stomach, Large Intestine or Lung. Tumori J. 1977, 63, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaman, M.; Kaya, G.; Yekeler, H. Distribution of trace metal concentrations in paired cancerous and non-cancerous human stomach tissues. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosova, F.; Cetin, B.; Akinci, M.; Aslan, S.; Seki, A.; Pirhan, Y.; et al. Serum copper levels in benign and malignant thyroid diseases. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2012, 113, 718–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimir, Z. Content of Copper, Iron, Iodine, Rubidium, Strontium and Zinc in Thyroid Malignant Nodules and Thyroid Tissue adjacent to Nodules. J. Clin. Diagn. Pathol. 2022, 1, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, U.; Myers, J.; Thorpe, L.; Daeschner 3rd, C.W.; Haggard, M.E. Copper, zinc, and iron in normal and leukemic lymphocytes from children. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 981–984. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, X.L.; Chen, J.M.; Zhou, X.; Li, X.Z.; Mei, G.Y. Levels of selenium, zinc, copper, and antioxidant enzyme activity in patients with leukemia. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2006, 114, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharvand, M.; Manifar, S.; Akkafan, R.; Mortazavi, H.; Sabour, S. Serum levels of ferritin, copper, and zinc in patients with oral cancer. Biomed. J. 2014, 37, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shettar, S.S. Estimation of serum copper and zinc levels in patients with oral cancer. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2016, 5, 4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; David, C.M.; Mahesh, D.R.; Sambargi, U.; Rashmi, K.J.; Benakanal, P. Assessment of serum copper, iron and immune complexes in potentially malignant disorders and oral cancer. Braz. Oral. Res. 2016, 30, e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-H.; Lee, C.-C.; Yen, Y.-H.; Chen, H.-L. Oxidative damage in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer co-exposed to phthalates and to trace elements. Env. Int. 2018, 121, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, S.A.K.; Adly, H.M.; Abdelkhaliq, A.A.; Nassir, A.M. Serum Levels of Selenium, Zinc, Copper, Manganese, and Iron in Prostate Cancer Patients. Curr. Urol. 2020, 14, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margalioth, E.J.; Udassin, R.; Cohen, C.; Maor, J.; Anteby, S.O.; Schenker, J.G. Serum copper level in gynecologic malignancies. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 1987, 157, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyong, K.; Singh, Y.; Singh, L.; Devi, T.; Singh, W. Serum copper level in different stages of cervical cancer. JMS - J. Med. Soc. 2012, 26, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Senra Varela, A.; Lopez Saez, J.J.B.; Quintela Senra, D. Serum ceruloplasmin as a diagnostic marker of cancer. Cancer Lett. 1997, 121, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar-Waron, H.; Gluckman, A.; Spira, E.; Waron, M.; Trainin, Z. Ceruloplasmin as a marker of neoplastic activity in rabbits bearing the VX-2 carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1978, 38, 1296–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, S.A.; Harris, A.L. The role of copper in tumour angiogenesis. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2005, 10, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasulewicz, A.; Mazur, A.; Opolski, A. Role of copper in tumour angiogenesis--clinical implications. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2004, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbel, R.S. Tumor angiogenesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, L.; Vogt, S.; Fukai, T.; Glesne, D. Copper and angiogenesis: unravelling a relationship key to cancer progression. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2009, 36, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, F.; Linden, T.; Katschinski, D.M.; Oehme, F.; Flamme, I.; Mukhopadhyay, C.K.; et al. Copper-dependent activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1: implications for ceruloplasmin regulation. Blood 2005, 105, 4613–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Kang, Y.J. Role of copper in angiogenesis and its medicinal implications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1304–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Li, X.K.; Song, Y.; Cherian, M.G. Essentiality, toxicology and chelation therapy of zinc and copper. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 2753–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camphausen, K.; Sproull, M.; Tantama, S.; Venditto, V.; Sankineni, S.; Scott, T.; et al. Evaluation of chelating agents as anti-angiogenic therapy through copper chelation. Bioorg Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 5133–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sproull, M.; Brechbiel, M.; Camphausen, K. Antiangiogenic therapy through copper chelation. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2003, 7, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Guo, Z. Copper in medicine: homeostasis, chelation therapy and antitumor drug design. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006, 13, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuberger, D.M.; Harankhedkar, S.; Morgan, T.; Wolint, P.; Calcagni, M.; Lai, B.; et al. High-affinity Cu(I) chelator PSP-2 as potential anti-angiogenic agent. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, S.L.S.-P.H. Comparison between concentrations of trace elements in normal and neoplastic human breast tissue. Cancer Res. 1984, 44, 5390–5394. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.K.; Shukla, V.K.; Vaidya, M.P. .; Roy, S.K.; Gupta, S. Serum trace elements and Cu/Zn ratio in breast cancer patients. J Surg Oncol.

- Chan, A.; Wong, F.; Arumanayagam, M. Serum ultrafiltrable copper, total copper and caeruloplasmin concentrations in gynaecological carcinomas. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 1993, 30 (Pt 6) Pt 6, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.M.; Cox, T.R.; Bird, D.; Lang, G.; Murray, G.I.; Sun, X.F.; et al. The role of lysyl oxidase in SRC-dependent proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H.E.; Cox, T.R.; Erler, J.T. The rationale for targeting the LOX family in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, F.; Martin, A.; Lopez-Menendez, C.; Moreno-Bueno, G.; Santos, V.; Vazquez-Naharro, A.; et al. Lysyl Oxidase-like Protein LOXL2 Promotes Lung Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 5846–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, V.C.; Gudekar, N.; Jasmer, K.; Papageorgiou, C.; Singh, K.; Petris, M.J. Copper metabolism as a unique vulnerability in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 118893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liburkin-Dan, T.; Toledano, S.; Neufeld, G. Lysyl Oxidase Family Enzymes and Their Role in Tumor Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Ge, G. Lysyl oxidase, extracellular matrix remodeling and cancer metastasis. Cancer Microenviron. 2012, 5, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.M.; Bird, D.; Lang, G.; Cox, T.R.; Erler, J.T. Lysyl oxidase enzymatic function increases stiffness to drive colorectal cancer progression through FAK. Oncogene 2013, 32, 1863–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannafon, B.N.; Sebastiani, P.; de las Morenas, A.; Lu, J.; Rosenberg, C.L. Expression of microRNA and their gene targets are dysregulated in preinvasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, T.; Gungor, C.; Thieltges, S.; Moller-Krull, M.; Penas, E.M.; Wicklein, D.; et al. Establishment and characterization of a new human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line with high metastatic potential to the lung. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G.; Nalvarte, I.; Smirnova, T.; Vecchi, M.; Aceto, N.; Dolemeyer, A.; et al. Memo is a copper-dependent redox protein with an essential role in migration and metastasis. Sci Signal 2014, 7, ra56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, C.L.; Hilton, C.N.; Airas, J.; Blake, A.; Rubenstein, K.J.; Parish, C.A.; et al. Identification of Phenazine-Based MEMO1 Small-Molecule Inhibitors: Virtual Screening, Fluorescence Polarization Validation, and Inhibition of Breast Cancer Migration. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Jing, Y.X.; Zhou, Z.W.; Yang, J.W. Knockdown of circRNA-Memo1 Reduces Hypoxia/Reoxygenation Injury in Human Brain Endothelial Cells Through miRNA-17-5p/SOS1 Axis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 2085–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Shi, J.; Mo, D.; Yang, Y.; Fu, Q.; Luo, Y. miR-219a-1 inhibits colon cancer cells proliferation and invasion by targeting MEMO1. Cancer Biol Ther 2020, 21, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Huynh, M.; Fehrenbacher, L.; West, H.; Lara Jr, P.N.; Yavorkovsky, L.L.; et al. Phase II trial of irinotecan and carboplatin for extensive or relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 1401–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Chen, G.J.; Oh, W.K.; Bellmunt, J.; Roth, B.J.; Petrioli, R.; et al. Comparative effectiveness of cisplatin-based and carboplatin-based chemotherapy for treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jr, G.W.S.; Sr, P.J.L.; Roth, B.J.; Einhorn, L.H. Cisplatin as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1988, 6, 1811–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.B.; D’Souza, B.J.; Wharam, M.D.; Champion, L.A.; Sinks, L.F.; Woo, S.Y.; et al. Cisplatin therapy in recurrent childhood brain tumors. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1982, 66, 2013–2020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mandala, M.; Ferretti, G.; Barni, S. Oxaliplatin in colon cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1691–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.P.; Hoskins, W.J.; Brady, M.F.; Kucera, P.R.; Partridge, E.E.; Look, K.Y.; et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhang, Y. Platinum-based agents for individualized cancer treatment. Curr. Mol. Med. 2013, 13, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilari, D.; Guancial, E.; Kim, E.S. Role of copper transporters in platinum resistance. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 7, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.T.; Chen, H.H.; Song, I.S.; Savaraj, N.; Ishikawa, T. The roles of copper transporters in cisplatin resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007, 26, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.S.; Savaraj, N.; Siddik, Z.H.; Liu, P.; Wei, Y.; Wu, C.J.; et al. Role of human copper transporter Ctr1 in the transport of platinum-based antitumor agents in cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2004, 3, 1543–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalayda, G.V.; Wagner, C.H.; Jaehde, U. Relevance of copper transporter 1 for cisplatin resistance in human ovarian carcinoma cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 116, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Choi, C.H.; Do, I.G.; Song, S.Y.; Lee, W.; Park, H.S.; et al. Prognostic value of the copper transporters, CTR1 and CTR2, in patients with ovarian carcinoma receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 122, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Yin, J.Y.; Liu, Z.Q.; Li, X.P. Copper efflux transporters ATP7A and ATP7B: Novel biomarkers for platinum drug resistance and targets for therapy. IUBMB Life 2018, 70, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangala, L.S.; Zuzel, V.; Schmandt, R.; Leshane, E.S.; Halder, J.B.; Armaiz-Pena, G.N.; et al. Therapeutic Targeting of ATP7B in Ovarian Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3770–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cai, B.; Chen, J.L.; Li, L.X.; Zhang, J.R.; Sun, Y.Y.; et al. ATP7B antisense oligodeoxynucleotides increase the cisplatin sensitivity of human ovarian cancer cell line SKOV3ipl. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2008, 18, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cao, W.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J. ATPase copper transporter A, negatively regulated by miR-148a-3p, contributes to cisplatin resistance in breast cancer cells. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020, 10, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, V. Selective Targeting of Cancer Cells by Copper Ionophores: An Overview. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsvetkov, P.; Coy, S.; Petrova, B.; Dreishpoon, M.; Verma, A.; Abdusamad, M.; et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science 2022, 375, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveri, V. Selective Targeting of Cancer Cells by Copper Ionophores: An Overview. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannappan, V.; Ali, M.; Small, B.; Rajendran, G.; Elzhenni, S.; Taj, H.; et al. Recent Advances in Repurposing Disulfiram and Disulfiram Derivatives as Copper-Dependent Anticancer Agents. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, M.; Anantha, M.; Backstrom, I.; Leung, A.; Chen, K.; Malhotra, A.; et al. Nanoscale Reaction Vessels Designed for Synthesis of Copper-Drug Complexes Suitable for Preclinical Development. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0153416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, M.; Anantha, M.; Shi, M.; Leung, A.W.Y.; Dragowska, W.H.; Sanche, L.; et al. Development and optimization of an injectable formulation of copper diethyldithiocarbamate, an active anticancer agent. Int J Nanomedicine 2017. [CrossRef]

- Noll, C.A.; Betz, L.D. Determination of Copper Ion by Modified Sodium Diethyldithiocarbamate Procedure. Anal. Chem. 1952, 24, 1894–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. A review of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of disulfiram and its metabolites. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1992, 86, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, E.; Rohondia, S.; Khan, R.; Dou, Q.P. Repurposing Disulfiram as An Anti-Cancer Agent: Updated Review on Literature and Patents. Recent. Pat. Anticancer. Drug Discov. 2019, 14, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, X.; Chen, X.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Lin, Z.; Yin, Y. Identification of a novel cuproptosis inducer that induces ER stress and oxidative stress to trigger immunogenic cell death in tumors. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 229, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.-Y.; Shen, Q.-H.; Hao, L.; Li, Z.-Y.; Yu, L.-B.; Chen, X.-X.; et al. Theranostic Rhenium Complexes as Suborganelle-Targeted Copper Ionophores To Stimulate Cuproptosis for Cancer Immunotherapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 15237–15249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldari, S.; Di Rocco, G.; Toietta, G. Current Biomedical Use of Copper Chelation Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowndes, S.A.; Harris, A.L. Copper chelation as an antiangiogenic therapy. Oncol. Res. 2004, 14, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrueck, A.; Sedgwick, A.C.; Brewster, J.T.; Yan, K.-C.; Shang, Y.; Knoll, D.M.; et al. Transition metal chelators, pro-chelators, and ionophores as small molecule cancer chemotherapeutic agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3726–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisawa, A.; Okui, T.; Shimo, T.; Ibaragi, S.; Okusha, Y.; Ono, M.; et al. Ammonium tetrathiomolybdate enhances the antitumor effects of cetuximab via the suppression of osteoclastogenesis in head and neck squamous carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Qin, J.; Zhou, C.; Wan, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. Multifunctional nanoparticles based on a polymeric copper chelator for combination treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Biomaterials 2019, 195, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Pradarelli, J.; Haseley, A.; Wojton, J.; Kaka, A.; Bratasz, A.; et al. Copper Chelation Enhances Antitumor Efficacy and Systemic Delivery of Oncolytic HSV. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 4931–4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Yu, J.-G.; Kaka, A.; Pan, Q.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, B.; et al. ATN-224 enhances antitumor efficacy of oncolytic herpes virus against both local and metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2015, 2, 15008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; McLeod, H.L.; Cassidy, J. Disulfiram-mediated inhibition of NF-?B activity enhances cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 104, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrott, Z.; Majera, D.; Gursky, J.; Buchtova, T.; Hajduch, M.; Mistrik, M.; et al. Disulfiram’s anti-cancer activity reflects targeting NPL4, not inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase. Oncogene 2019, 38, 6711–6722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah O’Brien, P.; Xi, Y.; Miller, J.R.; Brownell, A.L.; Zeng, Q.; Yoo, G.H.; et al. Disulfiram (Antabuse) activates ROS-dependent ER stress and apoptosis in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, K.G.; Chen, D.; Orlu, S.; Cui, Q.C.; Miller, F.R.; Dou, Q.P. Clioquinol and pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate complex with copper to form proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005, 7, R897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-H.; Lin, J.-K.; Liang, Y.-C.; Pan, M.-H.; Liu, S.-H.; Lin-Shiau, S.-Y. Involvement of activating transcription factors JNK, NF-κB, and AP-1 in apoptosis induced by pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate/Cu complex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 594, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, Z.H.; Haskó, G.; Vizi, E.S. PYRROLIDINE DITHIOCARBAMATE AUGMENTS IL-10, INHIBITS TNF-α, MIP-1α, IL-12, AND NITRIC OXIDE PRODUCTION AND PROTECTS FROM THE LETHAL EFFECT OF ENDOTOXIN. Shock. 1998, 10, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zhou, C.; Lu, L.; Liu, B.; Ding, Y. Elesclomol: a copper ionophore targeting mitochondrial metabolism for cancer therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupte, A.; Mumper, R.J. Copper chelation by D-penicillamine generates reactive oxygen species that are cytotoxic to human leukemia and breast cancer cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 43, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitman, S.K.; Huynh, T.; Bjarnason, T.A.; An, J.; Malkhasyan, K.A. A case report and focused literature review of <scp>d</scp> -penicillamine and severe neutropenia: A serious toxicity from a seldom-used drug. Clin. Case Rep. 2019, 7, 990–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, S.; Mumper, R.J. D-penicillamine and other low molecular weight thiols: Review of anticancer effects and related mechanisms. Cancer Lett. 2013, 337, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Bager, C.L.; Willumsen, N.; Ramchandani, D.; Kornhauser, N.; Ling, L.; et al. Tetrathiomolybdate (TM)-associated copper depletion influences collagen remodeling and immune response in the pre-metastatic niche of breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Abrams, G.D.; Dick, R.; Brewer, G.J. Efficacy of tetrathiomolybdate in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Transl. Res. 2008, 152, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshii, J.; Yoshiji, H.; Kuriyama, S.; Ikenaka, Y.; Noguchi, R.; Okuda, H.; et al. The copper-chelating agent, trientine, suppresses tumor development and angiogenesis in the murine hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 94, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, N.I.; Othman, I.; Abas, F.; H Lajis N, Naidu R. Mechanism of Apoptosis Induced by Curcumin in Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagetia, G.C.; Aggarwal, B.B. “Spicing Up” of the Immune System by Curcumin. J. Clin. Immunol. 2007, 27, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.; Lee, J.; Kambe, T.; Fritsche, K.; Petris, M.J. A Role for the ATP7A Copper-transporting ATPase in Macrophage Bactericidal Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 33949–33956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzanowska, H.; Wolcott, R.G.; Hannum, D.M.; Hurst, J.K. Bactericidal properties of hydrogen peroxide and copper or iron-containing complex ions in relation to leukocyte function. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 18, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toebak, M.J.; Pohlmann, P.R.; Sampat-Sardjoepersad, S.C.; von Blomberg, B.M.E.; Bruynzeel, D.P.; Scheper, R.J.; et al. CXCL8 secretion by dendritic cells predicts contact allergens from irritants. Toxicol. Vitr. 2006, 20, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- POCINOM Influence of the oral administration of excess copper on the immune response. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1991, 16, 249–256. [CrossRef]

- Turnlund, J.R.; Jacob, R.A.; Keen, C.L.; Strain, J.; Kelley, D.S.; Domek, J.M.; et al. Long-term high copper intake: effects on indexes of copper status, antioxidant status, and immune function in young men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Członkowska, A.; Milewski, B. Immunological observations on patients with Wilson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1976, 29, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderberg, L.S.F.; Barnett, J.B.; Sorenson, J.R.J. Copper Complexes Stimulate Hemopoiesis and Lymphopoiesis. Copper Bioavailability and Metabolism, Boston, MA: Springer US; 1989, p. 209–17. [CrossRef]

- Percival, S.S. Copper and immunity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabel, J.R.; Spears, J.W. Effect of Copper on Immune Function and Disease Resistance. Copper Bioavailability and Metabolism, Boston, MA: Springer US; 1989, p. 243–52. [CrossRef]

- Percival, S.S. Neutropenia caused by copper deficiency: possible mechanisms of action. Nutr. Rev. 1995, 53, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, L.D.; Mulhern, S.A.; Frankel, N.C.; Steven, M.G.; Williams, J.R. Immune dysfunction in rats fed a diet deficient in copper. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1987, 45, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukasewycz, O.A.; Prohaska, J.R.; Meyer, S.G.; Schmidtke, J.R.; Hatfield, S.M.; Marder, P. Alterations in lymphocyte subpopulations in copper-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 1985, 48, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonham, M.; O’Connor, J.M.; Hannigan, B.M.; Strain, J.J. The immune system as a physiological indicator of marginal copper status? British Journal of Nutrition 2002, 87, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosada, M.; Fiocco, U.; De Silvestro, G.; Doria, A.; Cozzi, L.; Favaretto, M.; et al. Effect of D-penicillamine on the T cell phenotype in scleroderma. Comparison between treated and untreated patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1993, 11, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.F.R.; Wyllie, A.H.; Currie, A.R. Apoptosis: A Basic Biological Phenomenon with Wideranging Implications in Tissue Kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 1972, 26, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casares, N.; Pequignot, M.O.; Tesniere, A.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Roux, S.; Chaput, N.; et al. Caspase-dependent immunogenicity of doxorubicin-induced tumor cell death. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2005. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MOLERH Whole body irradiation; radiobiology or medicine? Br J Radiol 1953. [CrossRef]

- Craig, D.J.; Nanavaty, N.S.; Devanaboyina, M.; Stanbery, L.; Hamouda, D.; Edelman, G.; et al. The abscopal effect of radiation therapy. Future Oncol. 2021, 17, 1683–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Warren, S.; Adjemian, S.; Agostinis, P.; Martinez, A.B.; et al. Consensus guidelines for the definition, detection and interpretation of immunogenic cell death. J Immunother Cancer 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kepp, O.; Tartour, E.; Vitale, I.; Vacchelli, E.; Adjemian, S.; Agostinis, P.; et al. Consensus guidelines for the detection of immunogenic cell death. Oncoimmunology 2014. [CrossRef]

- Obeid, M.; Tesniere, A.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Fimia, G.M.; Apetoh, L.; Perfettini, J.L.; et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Hua, Y.; Cai, Z. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy: Present and emerging inducers. J Cell Mol Med 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitvogel, L.; Kepp, O.; Senovilla, L.; Menger, L.; Chaput, N.; Kroemer, G. Immunogenic Tumor Cell Death for Optimal Anticancer Therapy: The Calreticulin Exposure Pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3100–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaretakis, T.; Kepp, O.; Brockmeier, U.; Tesniere, A.; Bjorklund, A.C.; Chapman, D.C.; et al. Mechanisms of pre-apoptotic calreticulin exposure in immunogenic cell death. EMBO Journal 2009. [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Humeau, J.; Buqué, A.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Immunostimulation with chemotherapy in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Gunti, S.; Allen, C.T.; Hong, Y.; Clavijo, P.E.; Van Waes, C.; et al. ASTX660, an antagonist of cIAP1/2 and XIAP, increases antigen processing machinery and can enhance radiation-induced immunogenic cell death in preclinical models of head and neck cancer. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, E.; Chargari, C.; Galluzzi, L.; Kroemer, G. Optimising efficacy and reducing toxicity of anticancer radioimmunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e452–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepp, O.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Clinical evidence that immunogenic cell death sensitizes to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1637188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Guo, J.; Hu, M.; Gao, Y.; Huang, L. Icaritin Exacerbates Mitophagy and Synergizes with Doxorubicin to Induce Immunogenic Cell Death in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 4816–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Shan, Y.; Ge, K.; Lu, J.; Kong, W.; Jia, C. Oxaliplatin induces immunogenic cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma cells and synergizes with immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cell. Oncol. 2020, 43, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gupta, S.; Bedke, J.; Kikuchi, E.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; et al. Enfortumab Vedotin and Pembrolizumab in Untreated Advanced Urothelial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden, M.S.; Sonpavde, G.; Powles, T.; Necchi, A.; Burotto, M.; Schenker, M. , et al. Nivolumab plus Gemcitabine–Cisplatin in Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucikova, J.; Kepp, O.; Kasikova, L.; Petroni, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Liu, P.; et al. Detection of immunogenic cell death and its relevance for cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, E.; Chargari, C.; Galluzzi, L.; Kroemer, G. Optimising efficacy and reducing toxicity of anticancer radioimmunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. [CrossRef]

- Vacchelli, E.; Galluzzi, L.; Fridman, W.H.; Galon, J.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Tartour, E.; et al. Trial watch: Chemotherapy with immunogenic cell death inducers. Oncoimmunology 2012. [CrossRef]

- Vacchelli, E.; Senovilla, L.; Eggermont, A.; Fridman, W.H.; Galon, J.; Zitvogel, L.; et al. Trial watch: Chemotherapy with immunogenic cell death inducers. Oncoimmunology 2013. [CrossRef]

- Vacchelli, E.; Aranda, F.; Eggermont, A.; Galon, J.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Cremer, I.; et al. Trial watch: Chemotherapy with immunogenic cell death inducers. Oncoimmunology 2014. [CrossRef]

- Pol, J.; Vacchelli, E.; Aranda, F.; Castoldi, F.; Eggermont, A.; Cremer, I.; et al. Trial Watch: Immunogenic cell death inducers for anticancer chemotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2015. [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.D.; More, S.; Rufo, N.; Mece, O.; Sassano, M.L.; Agostinis, P.; et al. Trial watch: Immunogenic cell death induction by anticancer chemotherapeutics. Oncoimmunology 2017. [CrossRef]

- Vanmeerbeek, I.; Sprooten, J.; De Ruysscher, D.; Tejpar, S.; Vandenberghe, P.; Fucikova, J.; et al. Trial watch: chemotherapy-induced immunogenic cell death in immuno-oncology. Oncoimmunology 2020. [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, R.; Choi, J.U.; Kweon, S.; Pangeni, R.; Lee, N.K.; Park, S.J.; et al. A novel oral metronomic chemotherapy provokes tumor specific immunity resulting in colon cancer eradication in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy. Biomaterials 2022, 281, 121334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wu, H.; Han, E.; Guo, Q. Chemoimmunotherapy by combining oxaliplatin with immune checkpoint blockades reduced tumor burden in colorectal cancer animal model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 487, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Shen, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Goodwin, T.J.; Li, J.; et al. Synergistic and low adverse effect cancer immunotherapy by immunogenic chemotherapy and locally expressed PD-L1 trap. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitara, K.; Van Cutsem, E.; Bang, Y.-J.; Fuchs, C.; Wyrwicz, L.; Lee, K.-W.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab or Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy vs Chemotherapy Alone for Patients With First-line, Advanced Gastric Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janjigian, Y.Y.; Shitara, K.; Moehler, M.; Garrido, M.; Salman, P.; Shen, L.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, J.; Zhao, L.; Hollebecque, A.; Kepp, O.; Zitvogel, L.; et al. PD-1 blockade synergizes with oxaliplatin-based, but not cisplatin-based, chemotherapy of gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, H.; Xiao, Y.; Loupakis, F.; Kawanishi, N.; Wang, J.; Battaglin, F.; et al. Immunogenic cell death pathway polymorphisms for predicting oxaliplatin efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer, 0017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, M.; Stecca, C.; Tobin, S.; Jiang, D.M.; Sridhar, S.S. Enfortumab Vedotin in urothelial cancer. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2020, 12, 175628722098019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.; Younan, P.; Liu, B.; Blahnik-Fagan, G.; Gosink, J.; Snead, K.; et al. 1187 Enfortumab vedotin induces immunogenic cell death, elicits antitumor immune memory, and shows enhanced preclinical activity in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Regular and Young Investigator Award Abstracts, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2022, p. A1229–A1229. [CrossRef]

- Skrott, Z.; Cvek, B. Diethyldithiocarbamate complex with copper: the mechanism of action in cancer cells. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Skrott, Z.; Mistrik, M.; Andersen, K.K.; Friis, S.; Majera, D.; Gursky, J.; et al. Alcohol-abuse drug disulfiram targets cancer via p97 segregase adaptor NPL4. Nature 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Jia, L.; Xie, L.; Kiang, J.G.; Wang, Y.; Sun, F.; et al. Turning anecdotal irradiation-induced anticancer immune responses into reproducible in situ cancer vaccines via disulfiram/copper-mediated enhanced immunogenic cell death of breast cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmel, S.; Gluz, O.; Reinisch, M.; Kostara, A.; Scheffen, I.; Graeser, M.; et al. Abstract PD10-11: Keyriched-1- A prospective, multicenter, open label, neoadjuvant phase ii single arm study with pembrolizumab in combination with dual anti-HER2 blockade with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in early breast cancer patients with molecular HER2-enriched intrinsic subtype. Cancer Res 2022, 82, PD10–PD11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, S.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Gombos, A.; Bachelot, T.; Hui, R.; Curigliano, G.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus trastuzumab in trastuzumab-resistant, advanced, HER2-positive breast cancer (PANACEA): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1b–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Rugo, H.S.; Adams, S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; et al. Atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel as first-line treatment for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (IMpassion130): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Dent, R.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; et al. Event-free Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Nowecki, Z.; Im, S.-A.; Yusof, M.M.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, S.P.; Wicha, M.S. Targeting breast cancer stem cells. Mol. Oncol. 2010, 4, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.M.L.; Lee, T.K.W. Cancer Stem Cells: Emerging Key Players in Immune Evasion of Cancers. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, S.; Ng, B.; Devitt, M.L.; Babb, J.S.; Kawashima, N.; Liebes, L.; et al. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. *Biol. *Phys. 2004, 58, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, M.Z.; Galloway, A.E.; Kawashima, N.; Dewyngaert, J.K.; Babb, J.S.; Formenti, S.C.; et al. Fractionated but Not Single-Dose Radiotherapy Induces an Immune-Mediated Abscopal Effect when Combined with Anti–CTLA-4 Antibody. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 5379–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.-L.; Chien, P.-J.; Hsieh, H.-C.; Shen, H.-T.; Lee, H.-T.; Chen, S.-M.; et al. Disulfiram/Copper Suppresses Cancer Stem Cell Activity in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Cells by Inhibiting BMI1 Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Cui, W.; Yuan, X.; Lin, L.; Cao, Q.; et al. Targeting ALDH1A1 by disulfiram/copper complex inhibits non-small cell lung cancer recurrence driven by ALDH-positive cancer stem cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 58516–58530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Castet, F.; Heikenwalder, M.; Maini, M.K.; Mazzaferro, V.; Pinato, D.J.; et al. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangro, B.; Sarobe, P.; Hervás-Stubbs, S.; Melero, I. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventura, P.; Shekarian, T.; Alcazer, V.; Valladeau-Guilemond, J.; Valsesia-Wittmann, S.; Amigorena, S.; et al. Cold Tumors: A Therapeutic Challenge for Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Suzuki, E.; Yuki, K.; Zen, Y.; Oshima, M.; Miyagi, S.; et al. Disulfiram Eradicates Tumor-Initiating Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells in ROS-p38 MAPK Pathway-Dependent and -Independent Manners. PLoS One 2014, 9, e84807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Johnson, A.; Northcote-Smith, J.; Lu, C.; Suntharalingam, K. Immunogenic Cell Death of Breast Cancer Stem Cells Induced by an Endoplasmic Reticulum-Targeting Copper (II) Complex. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 3618–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, L. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: current researches in cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 727–742. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.; Pelosof, L.; Lemery, S.; Gong, Y.; Goldberg, K.B.; Farrell, A.T.; et al. Systematic Review of PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors in Oncology: From Personalized Medicine to Public Health. Oncologist 2021, 26, e1786–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, F.; Sofiya, L.; Sykiotis, G.P.; Lamine, F.; Maillard, M.; Fraga, M.; et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroshow, D.B.; Bhalla, S.; Beasley, M.B.; Sholl, L.M.; Kerr, K.M.; Gnjatic, S.; et al. PD-L1 as a biomarker of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.A.; Patel, V.G. The role of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker: an analysis of all US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, P.; Roth, M.E.; Gill, J.; Piperdi, S.; Chinai, J.M.; Geller, D.S.; et al. Immune infiltration and PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment are prognostic in osteosarcoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okita, R.; Maeda, A.; Shimizu, K.; Nojima, Y.; Saisho, S.; Nakata, M. PD-L1 overexpression is partially regulated by EGFR/HER2 signaling and associated with poor prognosis in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shi, F.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, R.; et al. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 in advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma. Medicine 2020, 99, e23172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.-H.; Chan, L.-C.; Li, C.-W.; Hsu, J.L.; Hung, M.-C. Mechanisms Controlling PD-L1 Expression in Cancer. Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Chang, C.; Liu, B.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Cai, N.; et al. Copper (II) Ions Activate Ligand-Independent Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) Signaling Pathway. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannappan, V.; Ali, M.; Small, B.; Rajendran, G.; Elzhenni, S.; Taj, H.; et al. Recent Advances in Repurposing Disulfiram and Disulfiram Derivatives as Copper-Dependent Anticancer Agents n.d. [CrossRef]

- GRenoux MRELMLJGPBJMLABFOJAet, a.l. Sodium diethyldithiocarbamate (imuthiol) and cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1983, 166, 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Disulfiram in Patients With Metastatic Melanoma. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00256230. Updated , 2016. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00256230 n.d. 8 December.

- Disulfiram Plus Arsenic Trioxide In Patients With Metastatic Melanoma and at Least One Prior Systemic Therapy. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00571116. Updated , 2019. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00571116. n.d. 7 August.

- Goswami, M.; Gui, G.; Dillon, L.W.; Lindblad, K.E.; Thompson, J.; Valdez, J.; et al. Pembrolizumab and decitabine for refractory or relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Study of Chidamide, Decitabine and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in R/R NHL and Advanced Solid Tumors. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05320640. Updated , 2022. Accessed , 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05320640. n.d. 11 April.

- Wang, Q.; Zhu, T.; Miao, N.; Qu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chao, Y.; et al. Disulfiram bolsters T-cell anti-tumor immunity through direct activation of LCK-mediated TCR signaling. EMBO J 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.W.; Palle, K. Aldehyde dehydrogenases in cancer stem cells: potential as therapeutic targets. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 518–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazewicz, C.G.; Dinavahi, S.S.; Schell, T.D.; Robertson, G.P. Aldehyde dehydrogenase in regulatory T-cell development, immunity and cancer. Immunology 2019, 156, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T.; Suzuki, N.; Makino, H.; Furui, T.; Morii, E.; Aoki, H.; et al. Cancer stem-like cells of ovarian clear cell carcinoma are enriched in the ALDH-high population associated with an accelerated scavenging system in reactive oxygen species. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 137, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, B.; Chang, W.; Yuan, W.; Ma, Z.; et al. Prognostic Value of Cancer Stem Cell Marker ALDH1 Expression in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigoro, S.S.; Kurnia, D.; Kurnia, A.; Haryono, S.J.; Albar, Z.A. ALDH1 Cancer Stem Cell Marker as a Prognostic Factor in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino-Lagos, K.; Guo, Y.; Noelle, R.J. Retinoic acid: A key player in immunity. BioFactors 2010, 36, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mo, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wen, Z.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. The ALDH Family Contributes to Immunocyte Infiltration, Proliferation and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transformation in Glioma. Front Immunol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazewicz, C.G.; Dinavahi, S.S.; Schell, T.D.; Robertson, G.P. Aldehyde dehydrogenase in regulatory T-cell development, immunity and cancer. Immunology 2019, 156, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Flores, M.; Honrado Franco, E.; Sánchez Cousido, L.F.; Minguito-Carazo, C.; Sanz Guadarrama, O.; López González, L.; et al. Relationship between Aldehyde Dehydrogenase, PD-L1 and Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes with Pathologic Response and Survival in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xia, Y.; Wang, F.; Luo, M.; Yang, K.; Liang, S.; et al. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 2 Mediates Alcohol-Induced Colorectal Cancer Immune Escape through Stabilizing PD-L1 Expression. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2003404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almozyan, S.; Colak, D.; Mansour, F.; Alaiya, A.; Al-Harazi, O.; Qattan, A.; et al. PD-L1 promotes OCT4 and Nanog expression in breast cancer stem cells by sustaining PI3K/AKT pathway activation. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell, J.B.; Douglas, N.; Ukani, V.; Beumer, J.H.; Guo, J.; Payne, J.; et al. ALDH1A1 Gene Expression and Cellular Copper Levels between Low and Highly Metastatic Osteosarcoma Provide a Case for Novel Repurposing with Disulfiram and Copper. Sarcoma 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, L.-H.; Li, Y.; Fu, S.-Y.; Xue, X.; Jia, L.-N.; et al. Targeting ALDH2 with disulfiram/copper reverses the resistance of cancer cells to microtubule inhibitors. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 362, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, N.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, L. Disulfiram/copper targets stem cell-like ALDH + population of multiple myeloma by inhibition of ALDH1A1 and Hedgehog pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 6882–6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Cui, W.; Yuan, X.; Lin, L.; Cao, Q.; et al. Targeting ALDH1A1 by disulfiram/copper complex inhibits non-small cell lung cancer recurrence driven by ALDH-positive cancer stem cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 58516–58530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allensworth, J.L.; Evans, M.K.; Bertucci, F.; Aldrich, A.J.; Festa, R.A.; Finetti, P.; et al. Disulfiram (DSF) acts as a copper ionophore to induce copper-dependent oxidative stress and mediate anti-tumor efficacy in inflammatory breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, D.C.; Nelson, A.N.; Fauq, A.H.; Shriver, Z.H.; Veverka, K.A.; Naylor, S.; et al. S-Methyl N,N-diethylthiocarbamate sulfone, a potential metabolite of disulfiram and potent inhibitor of low Km mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995, 49, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinavahi, S.S.; Bazewicz, C.G.; Gowda, R.; Robertson, G.P. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Inhibitors for Cancer Therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persichini, T.; Percario, Z.; Mazzon, E.; Colasanti, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Musci, G. Copper Activates the NF-κB Pathway In Vivo. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2006, 8, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liao, J.; Yu, W.; Pei, R.; Qiao, N.; Han, Q.; et al. Copper induces oxidative stress with triggered NF-κB pathway leading to inflammatory responses in immune organs of chicken. Ecotoxicol. Env. Saf. 2020, 200, 110715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Xing, M. Oxidative stress-induced skeletal muscle injury involves in NF-κB/p53-activated immunosuppression and apoptosis response in copper (II) or/and arsenite-exposed chicken. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Guo, H.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; et al. Copper induces hepatic inflammatory responses by activation of MAPKs and NF-κB signalling pathways in the mouse. Ecotoxicol. Env. Saf. 2020, 201, 110806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Guo, C.; Gao, H.-L.; Zhong, M.-L.; Huang, T.-T.; et al. Tetrathiomolybdate Treatment Leads to the Suppression of Inflammatory Responses through the TRAF6/NFκB Pathway in LPS-Stimulated BV-2 Microglia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintin, P.a.n.; Celina, G. Kleer; Kenneth, L. van Golen; Jennifer Irani; Kristen M. Bottema; Carlos Bias; Magda De Carvalho; Enrique A. Mesri; Diane M. Robins; Robert D. Dick; George J. Brewer; Sofia D. Merajver. Copper deficiency induced by tetrathiomolybdate suppresses tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 4854–4859. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.; Tan, S.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Oyang, L.; et al. Role of the NFκB-signaling pathway in cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 2063–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.J.; Ratnam, N.M.; Byrd, J.C.; Guttridge, D.C. NF-κB Functions in Tumor Initiation by Suppressing the Surveillance of Both Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalle, G.; Twardowski, J.; Grinberg-Bleyer, Y. NF-κB in Cancer Immunity: Friend or Foe? Cells 2021, 10, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, C.M.; Hintzsche, J.D.; Wells, K.; Applegate, A.; Gorden, N.T.; Vorwald, V.M.; et al. Pre-Treatment Mutational and Transcriptomic Landscape of Responding Metastatic Melanoma Patients to Anti-PD1 Immunotherapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, C.S.; Tsoi, J.; Onyshchenko, M.; Abril-Rodriguez, G.; Ross-Macdonald, P.; Wind-Rotolo, M.; et al. Conserved Interferon-γ Signaling Drives Clinical Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy in Melanoma. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 500–515.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmi, R.R.; Sakthivel, K.M.; Guruvayoorappan, C. NF-κB inhibitors in treatment and prevention of lung cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hideshima, T.; Ikeda, H.; Chauhan, D.; Okawa, Y.; Raje, N.; Podar, K.; et al. Bortezomib induces canonical nuclear factor-κB activation in multiple myeloma cells. Blood 2009, 114, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolowska, O.; Rodziewicz-Lurzynska, A.; Pilch, Z.; Kedzierska, H.; Chlebowska-Tuz, J.; Sosnowska, A.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition improves antimyeloma activity of bortezomib and STING agonist combination in Vk*MYC preclinical model. Clin Exp Med 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standard Doses of Bortezomib and Pembrolizumab With or Without Pelareorep for the Treatment of Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma, AMBUSH Trial. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05514990. Updated , 2022. Accessed January 12, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05514990. n.d. 15 November.

- Bessho, R.; Matsubara, K.; Kubota, M.; Kuwakado, K.; Hirota, H.; Wakazono, Y.; et al. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate, a potent inhibitor of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activation, prevents apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells and thymocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994, 48, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, P.; Lam, P.; Zhou, Y.; Gasparello, J.; Finotti, A.; Chilin, A.; et al. Targeting DNA Binding for NF-κB as an Anticancer Approach in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cells 2018, 7, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; Chen, F.; Dong, H.; Shi, P.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Disulfiram targeting lymphoid malignant cell lines via ROS-JNK activation as well as Nrf2 and NF-kB pathway inhibition. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, S.; Li, R.; Chen, K.; He, L.; Deng, M.; et al. Disulfiram/copper selectively eradicates AML leukemia stem cells in vitro and in vivo by simultaneous induction of ROS-JNK and inhibition of NF-κB and Nrf2 2017. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xu, B.; Pandey, S.; Goessl, E.; Brown, J.; Armesilla, A.L.; et al. Disulfiram/copper complex inhibiting NFκB activity and potentiating cytotoxic effect of gemcitabine on colon and breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2010, 290, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A. DISulfiram for COvid-19 (DISCO) Trial (DISCO) n.d.:ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04485130.

- Knights, H.D.J. A Critical Review of the Evidence Concerning the HIV Latency Reversing Effect of Disulfiram, the Possible Explanations for Its Inability to Reduce the Size of the Latent Reservoir In Vivo, and the Caveats Associated with Its Use in Practice. AIDS Res. Treat. 2017, 2017, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Hu, C.; Zou, X. Preparation and antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Res. 2004, 339, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dautremepuits, C.; Betoulle, S.; Paris-Palacios, S.; Vernet, G. Immunology-related perturbations induced by copper and chitosan in carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Arch. Env. Contam. Toxicol. 2004, 47, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadhassan, Z.; Mohammadkhani, R.; Mohammadi, A.; Zaboli, K.A.; Kaboli, S.; Rahimi, H.; et al. Preparation of copper oxide nanoparticles coated with bovine serum albumin for delivery of methotrexate. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 67, 103015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameh, T.; Sayes, C.M. The potential exposure and hazards of copper nanoparticles: A review. Env. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 103220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariadoss, A.V.A.; Saravanakumar, K.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Venkatachalam, K.; Wang, M.-H. Folic acid functionalized starch encapsulated green synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery in breast cancer therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2073–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.T.T.; Peng, T.-Y.; Nguyen, T.H.; Bui, T.N.H.; Wang, C.-S.; Lee, W.-J.; et al. The crosstalk between copper-induced oxidative stress and cuproptosis: a novel potential anticancer paradigm. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naz, S.; Gul, A.; Zia, M. Toxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles: a review study. IET Nanobiotechnol 2020, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.W.Y.; Amador, C.; Wang, L.C.; Mody, U.V.; Bally, M.B. What Drives Innovation: The Canadian Touch on Liposomal Therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, A.C.; Gao, X.; Li, L.; Manning, M.L.; Patel, P.; Fu, W.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: (Daunorubicin and Cytarabine) Liposome for Injection for the Treatment of Adults with High-Risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2685–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H.A. Daunorubicin/Cytarabine Liposome: A Review in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. Drugs 2018, 78, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, E.C.; Anantha, M.; Zastre, J.; Meijs, M.; Zonderhuis, J.; Strutt, D.; et al. Irinophore C: A Liposome Formulation of Irinotecan with Substantially Improved Therapeutic Efficacy against a Panel of Human Xenograft Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, E.; Alnajim, J.; Anantha, M.; Taggar, A.; Thomas, A.; Edwards, K.; et al. Transition Metal-Mediated Liposomal Encapsulation of Irinotecan (CPT-11) Stabilizes the Drug in the Therapeutically Active Lactone Conformation. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 2799–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patankar, N.; Anantha, M.; Ramsay, E.; Waterhouse, D.; Bally, M. The Role of the Transition Metal Copper and the Ionophore A23187 in the Development of Irinophore CTM. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardi, P.G.; Gallagher, R.C.; Johnstone, S.; Harasym, N.; Webb, M.; Bally, M.B.; et al. Coencapsulation of irinotecan and floxuridine into low cholesterol-containing liposomes that coordinate drug release in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 2007, 1768, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicko, A.; Tardi, P.; Xie, X.; Mayer, L. Role of copper gluconate/triethanolamine in irinotecan encapsulation inside the liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 337, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, M.; Anantha, M.; Backstrom, I.; Leung, A.; Chen, K.; Malhotra, A.; et al. Nanoscale Reaction Vessels Designed for Synthesis of Copper-Drug Complexes Suitable for Preclinical Development. PLoS One, 0153. [Google Scholar]

- Szymański, P.; Frączek, T.; Markowicz, M.; Mikiciuk-Olasik, E. Development of copper based drugs, radiopharmaceuticals and medical materials. Biometals 2012, 25, 1089–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, M.; Malhotra, A.K.; Anantha, M.; Lo, C.; Dragowska, W.H.; Dos Santos, N.; et al. Development of a copper-clioquinol formulation suitable for intravenous use. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2018, 8, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Lin, W. Nanoparticles Synergize Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis to Potentiate Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2310309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Baatarbolat, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Y.; et al. Biomimic Nanodrugs Overcome Tumor Immunosuppressive Microenvironment to Enhance Cuproptosis/Chemodynamic-Induced Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhou, A.; Zhou, X.; He, J.; Xu, Y.; Ning, X. Cellular Trojan Horse initiates bimetallic Fe-Cu MOF-mediated synergistic cuproptosis and ferroptosis against malignancies. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-K.; Liang, J.-L.; Zhang, S.-M.; Huang, Q.-X.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, C.-J.; et al. Orchestrated copper-based nanoreactor for remodeling tumor microenvironment to amplify cuproptosis-mediated anti-tumor immunity in colorectal cancer. Mater. Today 2023, 68, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Luo, X.; Ru, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, D.; Huang, Q.; et al. Copper(II)-Based Nano-Regulator Correlates Cuproptosis Burst and Sequential Immunogenic Cell Death for Synergistic Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomater. Res. 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Qian, H.; Wang, X. Copper-based nanomaterials for cancer theranostics. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 14, e1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryon, E.B.; Molloy, S.A.; Kaplan, J.H. Cellular glutathione plays a key role in copper uptake mediated by human copper transporter 1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2013, 304, C768–C779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamchuea, K.; Batchelor-McAuley, C.; Compton, R.G. The Copper(II)-Catalyzed Oxidation of Glutathione. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2016, 22, 15937–15944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chang, L.; Tian, Y.; Hu, J.; Cao, Z.; Guo, X.; et al. Graphene Quantum Dot Sensitized Heterojunctions Induce Tumor-Specific Cuproptosis to Boost Sonodynamic and Chemodynamic Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Sahi, S.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Nanosonosensitization by Using Copper–Cysteamine Nanoparticles Augmented Sonodynamic Cancer Treatment. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2018, 35, 1700378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, M.; Anantha, M.; Shi, M.; Leung, A.W.-Y.; Dragowska, W.H.; Sanche, L.; et al. Development and optimization of an injectable formulation of copper diethyldithiocarbamate, an active anticancer agent. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 4129–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hébert, C.D.; Elwell, M.R.; Travlos, G.S.; Fitz, C.J.; Bucher, J.R. Subchronic Toxicity of Cupric Sulfate Administered in Drinking Water and Feed to Rats and Mice. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1993, 21, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, C.; Martoriati, A.; Pelinski, L.; Cailliau, K. Copper Complexes as Anticancer Agents Targeting Topoisomerases I and II. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; AlAjmi, M.F.; Rehman, M.d.T.; Amir, S.; Husain, F.M.; Alsalme, A.; et al. Copper(II) complexes as potential anticancer and Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents: In vitro and in vivo studies. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Ye, S.; Cao, N.; Huang, J.; Gao, J.; Chen, Q. ROS-mediated autophagy was involved in cancer cell death induced by novel copper(II) complex. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2010, 62, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolozzi, R.; Viola, G.; Porcù, E.; Consolaro, F.; Marzano, C.; Pellei, M.; et al. A novel copper(I) complex induces ER-stress-mediated apoptosis and sensitizes B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 5978–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S.; Squitti, R.; Haertlé, T.; Siotto, M.; Saboury, A.A. Role of Copper in the Onset of Alzheimer’s Disease Compared to Other Metals. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Deng, W.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, B.; Bai, B.; et al. PEGylated Elesclomol@Cu(Ⅱ)-based Metal‒organic framework with effective nanozyme performance and cuproptosis induction efficacy for enhanced PD-L1-based immunotherapy. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 29, 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, X.; Lin, C.; Yi, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, B.; et al. Elesclomol Loaded Copper Oxide Nanoplatform Triggers Cuproptosis to Enhance Antitumor Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Lin, W. Nanoparticles Synergize Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis to Potentiate Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heroux, D.; Leung, A.W.Y.; Gilabert-Oriol, R.; Kulkarni, J.; Anantha, M.; Cullis, P.R.; et al. Liposomal delivery of a disulfiram metabolite drives copper-mediated tumor immunity. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 683, 126010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heroux, D.; Leung, A.W.Y.; Gilabert-Oriol, R.; Farzaneh, S.; Milne, K.; Wolf, M.; et al. Immunogenic cell death in colorectal cancer models is modulated by baseline and ionophore-induced copper accumulation 2025. [CrossRef]

- Heroux, D.; Sun, X.X.; Zhang, S.; Sharifiaghdam, M.; Leung, A.W.Y.; Farzaneh, S.; et al. Copper ionophores drive divergent responses to immune checkpoint inhibition across colorectal tumor models 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cao, L.; Shen, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Li, C.; et al. Inducing Cuproptosis with Copper Ion-Loaded Aloe Emodin Self-Assembled Nanoparticles for Enhanced Tumor Photodynamic Immunotherapy. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Lan, J.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; et al. Disrupting intracellular redox homeostasis through copper-driven dual cell death to induce anti-tumor immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2026, 324, 123523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Li, X.; Wan, S.; Ji, S.; Wang, Q.; Hu, S.; et al. Copper-Doped Polydopamine Nanoparticles-Mediated GSH/GPX4-Depleted Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis Sensitizes Lung Tumor to Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy. Small 2025, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cancer | Serum Cu Level (µg/dL) | Tissue Cu Level (µg/g) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Cancer | Normal | Cancer | |||||

| Breast | 50.6 ±12.8 | 105.6 ± 12.8 | [25] | 9.3 ± 2.3 | 21.0 ± 10.7 | [67] | ||

| 98.8 ± 24.3 | 167.3 ±37.9 | [68] | 1.58 ± 0.62 | 1.91 ± 0.56 | [26] | |||

| Ovarian | 106.73 ± 26.37 | 146 ± 24.78 | [29] | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | [30] | ||

| 92.9 | 139.5 | [69] | 1.26 ± 0.45 | 2.16 ± 0.63 | [26] | |||

| Lung | 109.5 ± 5.39 | 122.9 ± 3.77 | [34] | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 1.52 ± 0.08 | [31] | ||

| 128.5 ±5.23 | 162.4 ± 8.18 | [33] | 5.08 ± 1.09 | 8.23 ± 4.88 | [32] | |||

| Colon | 152.08 ± 112.56 | 154.60 ± 91.71 | [35] | 1.53 ± 0.35 | 1.90 ± 0.6 | [26] | ||

| 135.8 ± 30.5 | 138.6 ± 30.8 | [37] | 1.26 ± 0.37 | 1.47 ± 0.58 | [36] | |||

| Stomach | 143.03 ± 3.25 | 171.94 ± 7.27 | [38] | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | [39] | ||

| Thyroid | 105.87±10.68 | 131.61±33.9 | [40] | 4.23 ± 0.18 | 14.5 ± 2.6 | [41] | ||

| Leukemia | 86.7 ± 25.3 | 132.8 ± 50.6 | [43] | 15 ± 4 * | 52 ± 16 * | [42] | ||

| Oral | 124.83 ± 20.68 | 151.20 ± 11.20 | [45] | |||||

| 114.20 ± 38.69 | 209.85 ± 160.28 | [44] | ||||||

| 105.5 + 18.81 | 141.99 ± 21.44 | [46] | ||||||

| Prostate | 97 ± 22 | 169 ± 31 | [48] | |||||

| 94.45 ± 34.37 | 100.31 32.38 | [47] | ||||||

| Cu like-Ionophores *(added Cu) | Cellular effect | Immune effect |

|---|---|---|

| Disulfiram [11,14,117,118,119] | *↓NF-κB, PSM, ALDH, *↑ROS | *↑ICD, PD-L1; ↓RA |

| Clioquinol [120] | *↓NF-κB, PSM | n.d. |

| Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate [120,121,122] | *↓NF-κB, PSM, ↑CSP3 | ↓TNF-α, ↓IL-12, ↑IL-10 |

| Elesclomol [123] | ↑ROS, ↓ATP7A | n.d. |

| Cu Chelators | ||

| Penicillamine [124,125,126] | ↑ROS, ↑dsDNA breaks | ↓TC, BC, NK, NP |

| Tetrathiomobdylate [127,128] | ↓NF-κB, RAS/MAPK | ↓TNF, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IFN-γ; ↑CD4+ infiltrate |

| Trientine [129] | ↓Angiogenesis | ↓IL-8 |

| Curcumin [130,131] | ↓NF-κB, ↑ROS | ↓IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).