1. Introduction: The Problem of the Reality of Time

Time remains one of the most contested concepts in philosophy and science. It figures not only as a measurable magnitude in physical processes but also as the qualitative horizon of consciousness and existence. Yet the reality of time cannot be reduced to a mere coordinate parameter; its intrinsic link to being and becoming calls for an ontological grounding that outstrips instrumental measurement (Heidegger 1962; McTaggart 1908). In contemporary physics, Smolin likewise contends that time is fundamental rather than derivative and argues that even effective laws may evolve over time, resisting timeless block-universe pictures (Smolin 2013; Smolin & Unger 2015; Smolin 2019; Rovelli 2018; Price 1996).

Reflecting on time therefore requires engagement with core metaphysical notions—being, causality, necessity and possibility, event, and duration. Foundational questions arise: Is time only a metric, or a real ontological structure? Is the future fixed or open? Is the order of nature governed by necessity or by custom (ʿāda)? These questions traverse cosmology and theology and bear directly on the philosophy of history and the history of knowledge, where accounts of causation, explanation, and evidence presuppose a stance on temporality (Ormsby 1984; Griffel 2009).

This article examines the ontological status of time through a comparative analysis of two paradigms: (i) al-Ghazālī’s theological model within the kalām tradition and (ii) Lee Smolin’s relational process model in contemporary physics. Despite emerging from divergent metaphysical frameworks, both converge on the claim that time is not merely a convenient measure but a foundational structure of reality. They diverge, however, in constitution:

Al-Ghazālī: time is a succession of discrete instants (

ānāt), each brought into being through God’s ongoing volitional act (

tajdīd al-khalqi). Succession is not necessary but chosen; every moment exists by divine will—hence time manifests volitional contingency (al-Ghazālī 2000; Marmura 1981; Griffel 2009; Dhanani 1994).

Smolin: time is an intrinsic evolutionary process of nature—the generative arena within which even laws may evolve—so that contingency reflects nature’s endogenous creativity and openness (Smolin 2013; Smolin & Unger 2015; Smolin 2019).

The comparative inquiry tracks four interrelated dimensions of temporality:

ontological succession and discreteness;

openness of the future and epistemic indeterminacy;

the status and transformability of natural laws; and

directionality and the metaphysical ground of temporality.

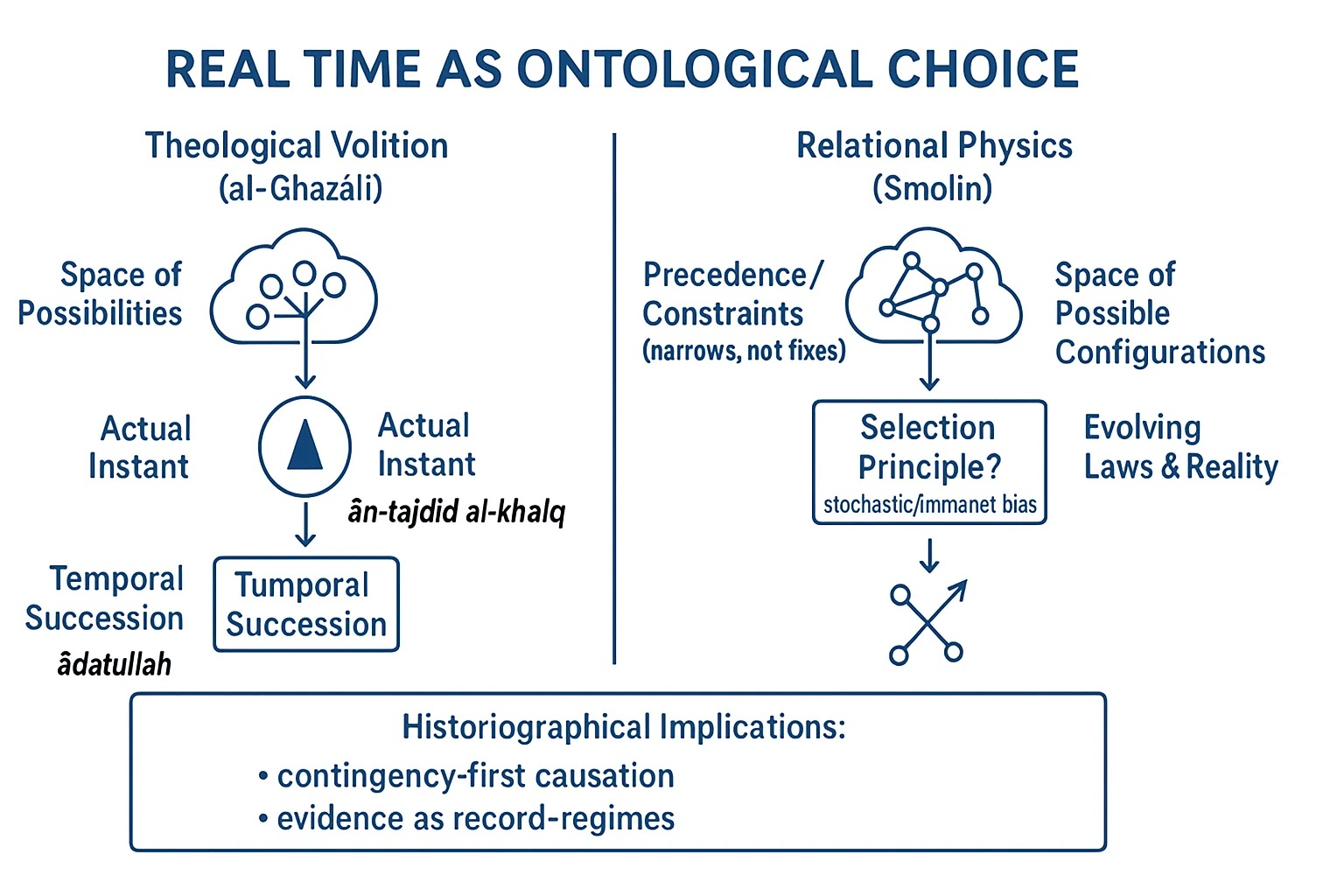

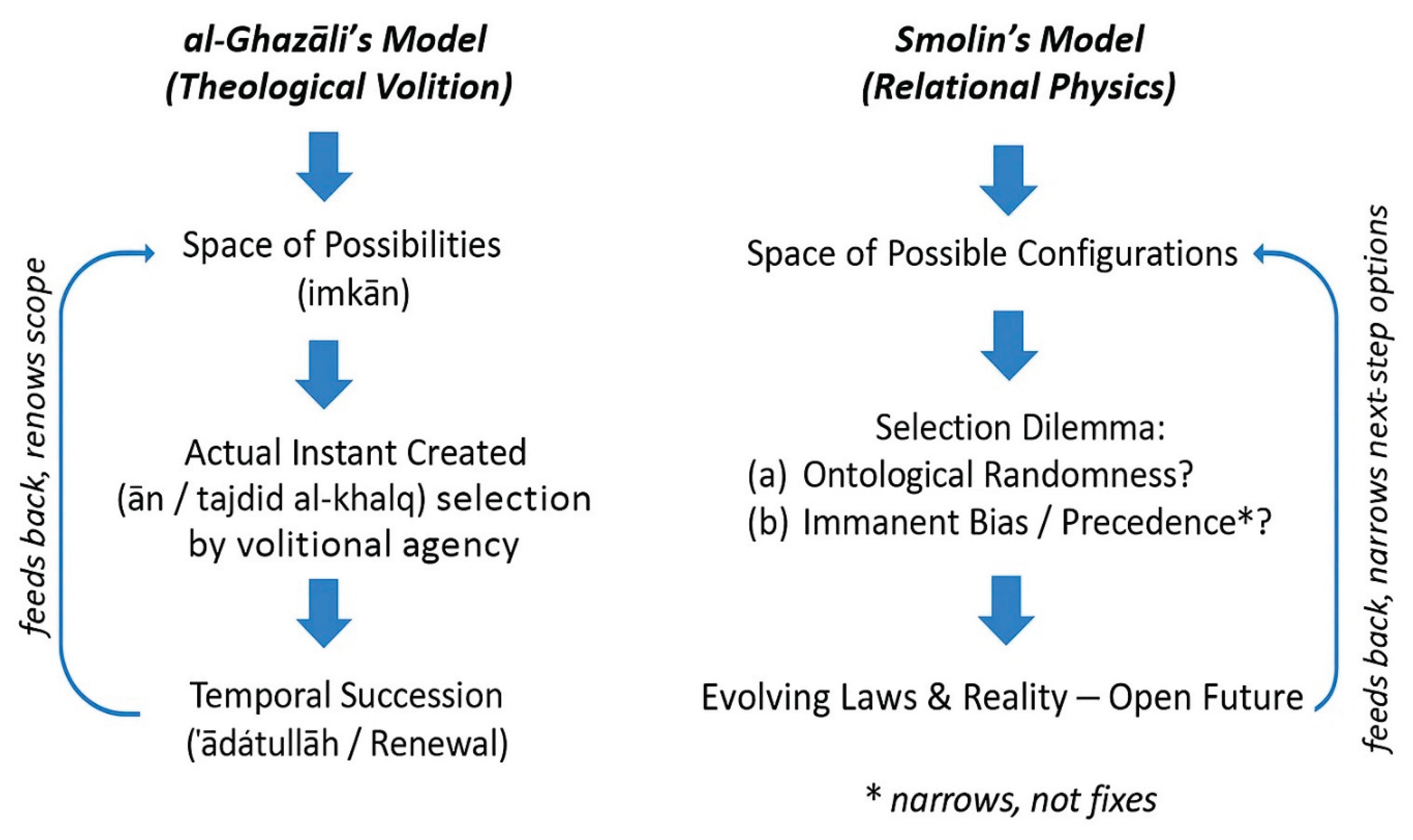

Rather than asking what time is, the study asks on what basis time exists. It argues that real time is neither an abstract container nor a passive continuum but an ontological decision process—constituted through agency, contingency, and acts of selection (Frank 1992; Smolin & Unger 2015). Bridging theological voluntarism and relational physics, the article develops a unified ontological account of temporality grounded in freedom and causative intent. In historiographical terms, if temporality is real, open, and decision-laden, then historical explanation must foreground contingency and agency, and the stability of evidence must be understood as an achievement of temporally structured record-regimes rather than a timeless given (Shannon 1948a;1948b; Landauer 1961; Zurek 2009; Lindsay 1959). Methodologically, the comparison is non-reductive and formally analogical. It advances actionable structural claims (not identities) and specifies principal disanalogies to avoid anachronism.

Thesis. Real time is an ontological decision process: across al-Ghazālī’s tajdīd al-khalq and Smolin’s law-evolving relationality, temporality is constituted by discreteness, contingency, and agency, not by timeless necessity. This reading changes historiographical practice: causal explanation must privilege contingency and agency, and the stability of evidence should be treated as an achievement of temporally structured record-regimes, rather than a given (cf. Lindsay 1959).

Roadmap.

Section 2 sketches the historical–conceptual background and states the non-reductive analogical method.

Section 3 reconstructs al-Ghazālī’s ontology of discrete time and volitional contingency.

Section 4 presents Smolin’s relational temporal ontology and law-evolution thesis.

Section 5 offers the comparative analysis (four axes: discreteness, openness, laws, directionality).

Section 6 develops the philosophical tensions between theological time and natural process.

Section 7 draws out implications for historiography and knowledge (decision principle,

logos, and record-regimes).

Section 8 concludes with the thesis of real time as ontological choice.

2. Historical Background: Three Conceptual Approaches to the Structure of Time

The ontological structure of time has preoccupied modern physics and metaphysics as well as classical traditions from ancient Greece through Islamic philosophy. What is at issue is not merely that time flows but what it flows through—its relation to being and to the orders that sustain or resist change. Competing models encode different commitments about continuity and discreteness, necessity and volition, and the standing of causality and agency.

Against this background, three broad approaches may be distinguished:

Aristotelian continuity: time as the measurable aspect of motion—a continuous, potentially divisible order grounded in natural necessity (Physics IV) (Aristotle 1984).

Avicennian metaphysical causality: time nested in a necessary hierarchy of being; moments follow as logical–ontological consequences within an emanationist framework (Avicenna 2009).

Kalām atomism: time as a succession of ontologically discrete, divinely created instants; regularities express ʿādātullāh (custom), not intrinsic necessity (Ormsby 1984; Griffel 2009; Dhanani 1994).

Each stance answers differently whether temporality is primarily physical, metaphysical, or theological, and thereby frames debates about the future’s openness, the nature of causal connection, the stability of laws, and the scope of agency. The remainder of this section clarifies these assumptions and tensions—showing what al-Ghazālī’s discontinuous account rejects and secures—so as to prepare a focused comparison with Smolin’s relational, law-evolving model in the next sections (Smolin and Unger 2015; Smolin 2019).

2.1. Aristotle: Continuity and Time as the Measure of Motion

In Physics IV, Aristotle defines time as “the number of motion with respect to before and after” (arithmos kinēseōs). Time is not a substance but a derivative magnitude grounded in the measurability of motion; the continuity of motion underwrites temporal continuity (Aristotle, 1984). Each “now” is articulated by “before” and “after,” yielding a continuous (muttasil) temporal order.

This is not the post-Cartesian analytic continuum. Aristotle denies actual infinity and allows only potential infinity—indefinite division without composition from infinitesimals. By contrast, modern analysis models continua as point-sets with completed infinities. Aristotelian continuity is thus ontological–kinematic rather than mathematical–set-theoretic (Frank 1992; Marmura 1981). (For how this becomes a point of critique in al-Ghazālī’s framework, see §3.)

2.2. Avicenna: Metaphysical Necessity and Ordered Temporality

Avicenna retains continuity but embeds temporality within a necessary order of being structured by emanation (ṣudūr). Moments follow not merely by observation but as logical–ontological consequences within a hierarchy grounded in the Necessary Existent (Wājib al-Wujūd) (Avicenna 2009). Time registers an intelligible structure whose necessity secures causal continuity.

This does not collapse time into clocked motion; rather, temporality expresses the rational order of causes. Read schematically, such necessity anticipates deterministic intuitions: given full knowledge of relevant conditions, outcomes would be fixed by the order of being. Although the path from Avicenna to early-modern determinisms is indirect, kalām theologians resist precisely this underwriting of succession by necessity (Ormsby 1984; Griffel 2009).

2.3. Kalām Atomism: Volitional Discreteness and ʿĀdātullāh

Kalām atomism reconceives time as ontologically discrete: successive instants (ān, pl. ānāt) are created event-by-event by divine will. Regularities reflect ʿādātullāh (customary divine regularities), not metaphysical necessity. Causation becomes the bestowal of existence at each instant; continuity in phenomena is contingent rather than guaranteed by inherent natures (Dhanani 1994; Ormsby 1984; Griffel 2009; Burrell et al. 2010).

This theological framework informed later Islamic intellectual traditions. In Ottoman and Safavid contexts, discussions of natural phenomena often construed regularity through the lens of divine will rather than inviolable natural law; see, for example, treatments of observation and instrumentation surrounding the sixteenth-century Istanbul observatory of Takī al-Dīn (Dallal 2010).

Note on Democritean comparison. While discreteness invites a superficial likeness to ancient atomisms, the bases differ: Democritean atoms move in a void under mechanical necessity; kalām discreteness is theological and volitional. The overlap is formal, not ontological (Frank 1992).

2.4. Stakes for Continuity, Causality, and Agency

The three approaches yield distinct answers to perennial questions. If time is primarily physical (Aristotle), continuity arises with motion; if metaphysical (Avicenna), necessity structures succession; if theological (kalām), discreteness and volition govern temporality. These alternatives bear on the openness of the future, the nature of causal connection, the stability of laws, and the scope of agency. For the philosophy of history and the history of knowledge, the adopted ontology of time shapes how we construct causal explanation, assess counterfactuals, and understand the formation, persistence, and reliability of records and evidence over time (Shannon 1948a;1948b; Landauer 1961; Zurek 2009).

2.5. Createdness and the Order of Instants

For the mutakallimūn, time—like the world—is ḥādith (created). Each instant exists because God wills it; connections among instants are volitional and contingent, not natural or necessary (al-Ghazālī 2000; Ormsby 1984). Apparent continuity is a phenomenological regularity sustained by ʿādātullāh. Temporal coherence, on this view, issues from sustained divine agency rather than from self-subsisting laws (Griffel 2009; Burrell et al. 2010).

2.6. Discreteness ≠ Incoherence

Discreteness does not entail chaos. Although ānāt are ontologically independent, their ordered sequence is maintained by continuous divine action (al-Ghazālī 2000; Marmura 1981). Contemporary physics programs sometimes entertain minimal or discrete temporal scales (often invoking Planck time), yet these remain theoretical and contested; they do not warrant identification with kalām’s theological discreteness. The usable point of contact is structural: both consider non-continuous temporal pictures, albeit for different reasons and with different ontological commitments (Rovelli 2004; Penrose 2010; Griffel 2009).

2.7. Al-Ghazālī’s Position within the Kalām Framework

Al-Ghazālī systematizes and defends the kalām model of temporal discreteness:

the order of time is volitional (ikhtiyārī), not necessary;

each instant (ān) is a distinct act of creation (tajdīd al-khalq); no necessary causal link binds successive moments;

the future is ontologically open and epistemically indeterminate (Marmura 1981; Ormsby 1984; Griffel 2009).

Within this framework, causality is recast in the language of will rather than necessity: real taʾthīr (efficacy) belongs to God; asbāb (secondary causes) are habitual connections operating within ʿādātullāh (divine custom) (Marmura 1981; Frank 1992). Thus what we call “natural law” is not the compulsory flow of an impersonal mechanism but the habitual persistence of divine wisdom (Burrell et al. 2010).

The ontological function of time. Time is not an impersonal continuity; it is the ontological stage of ongoing creation, co-constituted at every instant through continuous divine agency. This co-constitution encompasses not only the flow of events but also the corporeal order: substance–accident (jawhar–aʿrāḍ) structures and the persistence of phenomena exist at each instant by divine act within temporal succession (Dhanani 1994; Griffel 2009). The observed regularities express ʿādātullāh, not an intrinsic necessity.

Foreshadow. This discontinuous, decision-laden temporality stands in sharp contrast to Aristotelian and Avicennian necessitarianism and prepares the ground for a focused comparison with Smolin’s relational, law-evolving model (§§3–4), where openness and contingency are likewise central—yet grounded in the physical world rather than in divine volition (Smolin & Unger 2015; Smolin 2019). Although we read the topic through analogies aimed at understanding the physical world, much classical debate concentrated on how the universe’s architecture is constituted—at times even advancing claims of structural isomorphism. We adopt a formally analogical reading; by contrast, parts of the classical literature proceed not merely by analogy but by assertions of identity/sameness, and at points by explicit isomorphism claims

ii.

iii

3. The Ontological Structure of Time and Volitional Contingency in Al-Ghazālī

Al-Ghazālī’s account presupposes the kalām thesis of created discreteness outlined in §2.3: successive ānāt are brought into being by divine will. Time is not a pre-existing dimension within a continuous cosmos; it is a process of ongoing creation (tajdīd al-khalq) actualized at each discrete instant by divine will (irāda ilāhiyya) (al-Ghazālī, 2000; Griffel, 2009). Against Aristotelian continuity and Avicennian necessity, al-Ghazālī roots temporality in volitional contingency (ikhtiyārī), whereby each moment is ontologically independent and existentially open (Frank 1992; Dhanani 1994, Erdoğan at al. 2024).

This model unfolds across three interdependent dimensions:

Temporal ontology as created discreteness — time consists of ontologically discrete instants (ānāt), not a continuous flow; any apparent continuity is the phenomenology of sustained willing (al-Ghazālī 2000; Dhanani 1994).

Causality as volitional, not necessary — temporal succession is grounded in will rather than metaphysical determinism; real taʾthīr (efficacy) belongs to God, while asbāb (secondary causes) mark habitual connections within ʿādātullāh (Marmura 1981; Griffel 2009; Ormsby 1984).

Time as an arena of renewal and responsibility — each instant is a site for renewal, guidance, and human kasb (acquisition); openness of the future is both ontological and epistemic, underwriting accountability without positing creaturely independent efficacy (Burrell et al. 2010; Griffel 2009).

3.1. Created Discreteness: Instants and Ongoing Creation

For al-Ghazālī, time comprises indivisible instants—ān (pl. ānāt)—each brought into existence through a fresh act of creation. Apparent continuity is a phenomenological regularity rather than an ontological given. What persists is not an inherent temporal medium but the continuous bestowal of existence, moment by moment (al-Ghazālī 2000; Griffel 2009). In this sense, time is neither a container nor a passive coordinate; it is the rhythm of divine creative choice.

3.2. Volitional Contingency and the Absoluteness of the Agent

Discontinuity is an ontological principle: a moment exists if God wills and does not exist if He does not will (al-Ghazālī 2000). Contingency here is not “probabilistic uncertainty” but volitional contingency—the dependence of existence on the deliberate choice of the ultimate agent (al-fāʿil al-muṭlaq). Natural regularities are therefore habitual rather than necessary: ʿādātullāh names the reliable repetition of divine preference, not an autonomous law. Stability in nature signals faithful choosing, not metaphysical compulsion (Ormsby 1984; Griffel 2009; Marmura 1981). This reorients causality: where classical models treat effects as necessarily flowing from causes, al-Ghazālī centers divine freedom. The future is genuinely open; natural “laws” are contingent rather than fixed; and intervention remains metaphysically available at any instant (Marmura 1981; Griffel 2009).

3.3. Detaching Causality from Continuity

One of al-Ghazālī’s most radical moves is to separate causality from continuity. Causal links are not necessary connections but habits sustained by will (al-Ghazālī 2000; Ormsby 1984). Each event is a novel occurrence, actualized by a fresh decision. Temporal order therefore arises from a voluntary sequence of discrete creative acts. Empirical science’s law-like patterns can be described, yet on this view they do not bind God; they record the history of repeated preference (ʿādātullāh) (Griffel 2009; Dhanani 1994). The upshot is both epistemic and metaphysical: time becomes an arena of agency, directionality, and openness—coherent not through intrinsic natures but through sustained intentionality. Thus the world is decision-laden yet dependable; any resemblance to discrete-time programs in physics remains structural and analogical rather than identificatory.

3.4. Al-Ghazālī’s Original Contribution within Kalām: Modal, Epistemic, Moral

Al-Ghazālī does not merely restate the kalām thesis of discrete time; he deepens it along five axes and frames temporality as an ontological process constituted by acts of selection.

Modal logic and will. Temporal succession is treated through the conjunction of possibility (imkān) and choice (ikhtiyār). Rejecting necessity (ḍarūra), al-Ghazālī explains how ʿādātullāh (habitual divine regularities) and volition operate together: an event’s occurrence is possible; its actualization is by choice. Time is thus not a neutral “space of possibilities” but a field of possibilities shaped by will (al-Ghazālī 2000; Marmura 1981; Griffel 2009).

Epistemic regime and the logic of expectation. Inferences from natural regularities yield not yaqīn (certainty) but—çoğu durumda—well-grounded ẓann (assent). Scientific, law-like statements underwrite high-reliability expectations rather than essential necessity; such expectations rest on accumulated qarīna regarding the persistence of ʿādātullāh. “Knowledge of the future” can therefore be epistemically strong without being logically necessary, precisely because ontological openness is real (Ormsby 1984; Griffel 2009).

Ontological stage and the jawhar–aʿrāḍ dynamic. Time is not merely a sequence of events; it is the ontological stage on which the jawhar–aʿrāḍ (substance–accident) order is re-established at every instant. The sense of continuity arises not from inherent persistence of substances but from the renewal (tajdīd) and confirmation (taqrīr) of accidents through divine action. No separate “temporal medium” is required as an ontic carrier; the carrier is agency (Dhanani 1994; al-Ghazālī 2000).

Moral agency and kasb. The renewability of the instant centers human kasb (acquisition) in moral responsibility: ontological openness makes repentance, guidance, and intervention genuinely possible. Time thereby becomes a structural condition for ethical orientation and accountability (Ormsby 1984; Burrell et al. 2010).

Reinterpreting “natural law.” “Law” is not a set of forces intrinsically inhering in things, but the stabilized history of divine preferences guided by wisdom. Science describes this history at a statistical–phenomenological level; at the metaphysical level it does not bind the divine will. This two-tier (descriptive–metaphysical) distinction provides a distinctive theological frame for debates on the evolution of laws (Marmura 1981; Griffel 2009).

Synthesis. Al-Ghazālī’s originality lies in systematizing discrete time across the modal (imkān–ikhtiyār), epistemic (ẓann–qarīna), and moral (kasb–responsibility) registers, yielding a picture of temporality as decision-laden discreteness. This sets the stage for §§4–5: Smolin’s relational, law-evolving ontology also affirms openness and contingency, yet grounds them in the endogenous creativity of the physical order rather than in the will of the ultimate agent (al-fāʿil al-muṭlaq).

4. Time, Evolution, and Ontological Contingency in Lee Smolin

Lee Smolin conceives time as a foundational ontological category, not a derived bookkeeping parameter (Smolin 2013). Time is real and constitutive: it underwrites not only the evolution of physical systems but—more radically—the historical development of the laws that govern them. Against Newtonian absolute time (external, homogeneous) and against block-universe readings sometimes drawn from relativistic spacetime (whose fundamental equations are typically time-reversal symmetric), Smolin argues for a directional, generative temporality that is not subordinate to timeless law but prior to it (Smolin 2013; Smolin & Unger 2015).

On this account, time is not a static backdrop; it is an active, productive medium through which the cosmos and its organizing principles undergo historical change. The metaphysical status of time thus shifts from geometric abstraction to processual unfolding (Smolin & Unger 2015). The model prioritizes becoming over being and openness over fixity:

natural “laws” are historically evolving regularities;

the future is genuinely open, not fully entailed by initial conditions or eternal equations;

the universe is a temporally unfolding structure whose principles admit revision.

Here contingency is not an epistemic defect but an ontological principle: reality is not governed by atemporal mathematical truths “outside time,” but by structures whose very rules can change (Smolin 2019). Smolin’s temporal ontology resonates with themes in process philosophy (temporal creativity) and shows structural affinities to classical Islamic kalām—especially al-Ghazālī’s decision-laden discreteness—while remaining naturalistic rather than volitional (Griffel 2009; Ormsby 1984). The common horizon is a vision of time as the site of continual novelty.

4.1. The Ontological Priority of Time

Smolin’s central thesis is that time is most fundamental (Smolin 2013). Space, matter, energy—and crucially, the laws—are time-bound and changeable. In contrast to Newton’s absolute clock and to block-universe pictures, Smolin maintains that time is directional, transformative, and causally efficacious. It should not be reduced to a passive coordinate constrained by timeless symmetries; it conditions the very possibility of events and laws (Smolin & Unger 2015). Accordingly, time is:

irreducible—removing it drains explanatory power;

generative—a condition for novelty, not merely motion; and,

ontologically foundational—the ground of change, development, and emergence.

4.2. Evolution of Laws and Deep Contingency

A defining claim is that not only events but the laws themselves evolve (Smolin 2013; Smolin & Unger 2015). Against Platonic ideals of timeless, immutable law, Smolin holds that laws are historically contingent regularities that co-evolve with the universe. The consequence is a radicalized temporality:

the future is open, not merely uncertain;

no law is metaphysically necessary;

long-run predictability is limited because the rules of prediction may themselves change.

This is contingency without transcendence: creativity emerges from within nature’s dynamics, rather than by imposition from outside. Law and time co-constitute one another—laws evolve in time, and time enables the evolution of law.

Principle of precedence. Smolin concretizes this framework with the principle of precedence: when a new kind of process occurs for the first time, the dynamics are relatively unconstrained; as similar events repeat, the accumulation of past instances partly restricts subsequent occurrences, and in this way effective laws gain stability over historical time. The model (i) explains temporal directionality via path-dependence; (ii) limits predictability to domains covered by accumulated precedents; and (iii) replaces timeless necessity with historical consolidation (Smolin 2013; Smolin & Unger 2015; Smolin 2019). Thus the law–time relation is not co-eternal but forged within time—a point that bridges to the decision principle in §6 (a selection mechanism for which of the possible futures becomes actual).

4.3. Natural Creativity without Transcendence

In Smolin’s framework, contingency names the endogenous generativity of nature. Novel structures, rules, and patterns arise through self-organizing processes, not through an extra-natural will (Smolin 2013; Smolin 2019; Smolin & Unger 2015; Guler 2025). Three pillars summarize the stance:

Self-organization: cosmic order emerges from internal dynamics;

Creative time: novelty is a function of temporal unfolding, not a timeless design;

Openness & transformation: reality can reconfigure itself as laws and structures change.

Despite different grounds, this naturalistic creativity bears a formal likeness to al-Ghazālī’s volitional discreteness: both reject timeless determinism and insist on a future open to genuine possibility. In Smolin, renewal arises from nature’s own temporal dynamics; in al-Ghazālī, from divine will. The comparison in §§5–6 will specify how these distinct grounds generate shared implications for historiography—especially concerning causal explanation, counterfactuals, and the durability of record-regimes over time.

5. Ontological Convergence: Formal Parallels between al-Ghazālī and Lee Smolin

Despite emerging from distinct traditions—classical Islamic

kalām and contemporary theoretical physics—al-Ghazālī and Lee Smolin converge on a shared picture of real, constitutive temporality. The grounds differ (divine volition vs. natural process), yet the structure shows parallels across discreteness, openness, and evolving order. The claim here is formal and non-reductive; no identity between theology and physics is asserted (see

Table 1).

Upshot. Whether grounded in volition or in process, both pictures relocate order inside time rather than above it. On succession, each new state is fixed in time (by will vs. by emergent precedence). On laws, stability reads as historical consolidation, not timeless necessity. On future, both frameworks license genuine openness—hence responsibility and counterfactual practice.

6. Philosophical Unfolding: A Tension Between Theological Time and Natural Process

The structural affinities between al-Ghazālī’s theological model and Lee Smolin’s naturalistic framework show that two very different traditions converge on overlapping structures of temporality: both affirm time as contingent, sequential, and ontologically open. Beneath this convergence, however, lies a deeper philosophical tension—not only about the function of time but about its source, meaning, and direction. This section presumes the formal parallels established in §5 and turns to the fault lines.

6.1. The Source of Time: Agency or Process?

In al-Ghazālī’s theological model, time originates in the volitional act of a transcendent agent. Each instant—ān (pl. ānāt)—is created ex nihilo by the sovereign will of God; reality is sustained through ongoing re-creation (tajdīd al-khalq). Time is thus an ontically active domain contingent on divine intentionality and governed by the absolute agent (al-fāʿil) (Griffel 2009).

By contrast, in Smolin’s naturalistic model, time arises from the self-organizing dynamics of nature. Physical “laws” are not externally imposed fixities but evolving regularities that emerge within the cosmos’s historical unfolding. There is no transcendent chooser; the universe generates order from within its own temporal evolution (Smolin 2013; Smolin & Unger 2015).

The contrast is therefore both ontological and epistemological. Al-Ghazālī begins with agency and intention; Smolin begins with immanent process accessible to empirical inquiry. In short, al-Ghazālī’s time begins with a will; Smolin’s with a process.

6.2. Burdens and Payoffs: Meaning, Direction, and Theodicy vs. Openness

Al-Ghazālī’s horizon allows for purposive orientation (ḥikma) within temporal succession; directionality arises from chosen renewal. Smolin’s horizon, by design, excludes transcendent teleology: directionality emerges from historical constraints and precedence effects. Consequently, “meaning” is given in the former, whereas in the latter it is—if at all—something that emerges over time.

This divergence imposes different philosophical costs. The theological model secures stability, yet it bears the burden of theodicy: if every moment is created ex nihilo, then disorder and moral evil sit, to some degree, within the scope of divine creative action (Ormsby 1984). The problem of evil thus acquires a temporal register: volitional creation and suffering coincide at the level of the instant.

Some cosmological proposals echo aspects of the theological picture without entailing it: debates about a universe arising “from nothing” via quantum tunneling (Vilenkin 1982) resonate with ḥudūth al-ʿālam; likewise, Penrose (2010) argues that the early universe possessed extraordinarily low entropy—features a teleological reading might take as intentional order rather than mere contingency.

Smolin’s framework sidesteps theodicy by excluding a purposive agent: disorder and complexity arise as statistical outcomes of non-teleological processes rather than from will. Yet this openness introduces a different difficulty: the risk of erosion of meaning. Without a transcendent referent, grounding moral value, purpose, or responsibility can be more fragile (Smolin 2013). (For a contrasting path, see Kant’s attempt to secure normativity via practical reason rather than teleology; this sits uneasily with realist accounts of time and with agency-laden frameworks here considered) (Kant 1996a; 1996b).

Tension in brief. Theological time entails metaphysical responsibility; naturalistic time entails ontological freedom—and possibly existential ambiguity(see

Table 2).

6.3. Possibility of a Metaphysical Convergence?

While al-Ghazālī and Lee Smolin work within divergent ontologies—one grounded in divine agency, the other in naturalistic process—their models exhibit structural affinities that open room for a limited metaphysical convergence. The point is not doctrinal synthesis but a narrow, formal isomorphism between continuous creation (tajdīd al-khalq) and a physical picture of dynamic, relational temporality.

On al-Ghazālī’s view, the world is re-created at every instant by volition. Each ān is not the necessitated effect of its predecessor but a fresh ontic act; coherence arises not from metaphysical necessity but from ʿādātullāh, a freely maintained habitual order (al-Ghazālī Iḥyāʾ, Book I; Griffel 2009, 146–54). Smolin’s framework, without theological presuppositions, likewise treats time as real and generative. In relational programs to which his work contributes, spacetime is read (on some accounts) as an emergent network of evolving relations—often modeled via vertices and links—where history-sensitivity and local constraints are constitutive (Smolin 2013). Cautiously taken, heuristic links to holographic constraints and Planck-scale minimalities suggest a granular, history-sensitive temporality that resonates analogically with al-Ghazālī’s moment-to-moment actualization.

The convergence is therefore structural rather than substantive. Al-Ghazālī attributes order to an intentional Creator; Smolin, to self-organizing nature. Yet both deny timeless necessity, affirm temporal succession as foundational, and locate regularity in local, relational, contingent patterns rather than in immutable, atemporal laws. From this angle, tajdīd al-khalq and law-evolution play analogous roles: each moment functions as a decision-point—by will in one case, by emergent interaction/precedence in the other—through which reality is continuously built. Such convergence does not collapse theology into physics; it invites a bridging metaphysics in which time is not a passive dimension but an active ontological process: generative, relational, irreducible.

6.4. The Decision Point in Relationality: A Dilemma in Smolin’s Model

Smolin’s relational picture portrays the universe not as ruled by fixed, universal laws but as constituted by evolving topological relations among discrete elements at very small scales (Smolin 2013). As argued in §4.2, precedence constrains by path-dependence; here the question is what selects among equipossible futures. Absent a selection principle, it is hard to explain how directional, creative temporality arises from a field of symmetric potentials (Smolin 2013, 71–103). Relationality maps possibilities; real time seems to require not only succession but decision and orientation. If only one of several possible futures occurs, actualization must rest either on stochastic choice or on some directive principle.

Smolin gestures toward a constraint via the principle of precedence—past instances partly restrict subsequent ones, stabilizing effective regularities over historical time (Smolin 2013; Smolin 2019)—but this explains constraint more than selection among equipossible futures.

6.4.1. Ontological Randomness: Limits of Non-Agentive Selection

Invoking pure randomness preserves openness but attenuates agency and orientation. It tells us how events happen, not why this outcome rather than another becomes real. Dice preserve possibility but do not ground directed becoming (Born 1971).

6.4.2. Immanent Orientation: Encoded Teleology without Agency?

Alternatively, immanent biases or relational constraints might tilt transitions. If such orientation is pre-inscribed, however, it risks reintroducing deterministic structure at odds with the model’s anti-Platonism; if it is not, one falls back to randomness. Either way, the ground of temporal direction remains unsettled.

6.4.3. Real Time Requires Decision: A Case for Ontological Agency

For any ontology of real temporality, becoming seems to require more than successive states; it requires selection. A universe that generates alternatives but never explains which becomes actual dissolves into modal equivalence. Multiverse appeals (where all outcomes occur) evade the choice but undercut a single historical universe—which Smolin explicitly defends (Smolin 2013). Al-Ghazālī offers a contrasting resolution: each instant is instantiated by volition—

tajdīd al-khalq—so that reality is an ordered chain of intentional acts rather than a random drift (Griffel 2009; Burrell et al. 2010). The comparative moral is

not that physics must adopt theology, but that real time is chosen time: any account that rejects both timeless necessity and transcendent will must still furnish a decision principle adequate to directed becoming(see

Figure 1).

7. Implications for History and Knowledge

7.1. The Historical Horizon of Logos: Necessity or Process?

Aristotle/Avicenna. A rational order (logos) operates through continuity and necessity; time measures that order (Aristotle 1984; Avicenna 2009). In the Peripatetic line (al-Fārābī, Ibn Sīnā, Ibn Rushd), the cosmos bears an immutable structure harmonious with God’s eternal knowledge; time is derivative of this fixed order (Ibn Rushd 1998). Analogically, this stance aligns with block-universe eternalism (Price 1996; Barbour 1999).

Kalām / al-Ghazālī. (The term logos is not ascribed to al-Ghazālī.) Order is volitional and contingent: by tajdīd al-khalq each instant is newly given; regularities are ʿādātullāh—habit, not intrinsic law (al-Ghazālī 2000; Griffel 2009). Ashʿarī theology rejects Peripatetic necessity and grounds causality in divine will (see al-Ghazālī 2000).

Smolin. By challenging timeless, Platonic conceptions of law, Smolin relocates order within a time-formed and evolving rationality; “logos” (in a broad sense) becomes process-centered (Smolin 2013; Smolin & Unger 2015). His model thereby opposes classical metaphysics of necessity and reframes rational order as historically achieved.

7.2. Smolin as a “Temporal Logos”: Yes and No

No (no personified mind). Smolin does not posit a teleological or intending reason; there is no transcendent agent.

Yes (structural rationality). Time is an immanent medium through which order arises; laws stabilize historically and can change—“rationality formed in time” (Smolin 2013). For example, early-universe conditions partly shape later effective laws; and, as in Prigogine’s account of arrows of time, order emerges from non-equilibrium processes (Prigogine & Stengers 1984). This “yes/no” duality clarifies both affinities and differences between Smolin and historical models—especially al-Ghazālī.

7.3. Structural Affinity with al-Ghazālī—and the Basic Divide

Affinity. Both models reject timeless necessity and emphasize an open future, discreteness, and evolving order (Griffel 2009; Smolin 2013). For instance, al-Ghazālī’s ʿādātullāh (e.g., fire burning as divine habit rather than necessary causation) is structurally parallel to Smolin’s historically evolving laws: both make order renewable rather than fixed.

Divide. The ground of order in al-Ghazālī is volitional agency (divine will); in Smolin it is self-organizing nature. The former yields an intentional, the latter a non-voluntarist outline of “logos.” While Ashʿarī theological contingency overlaps at points with Smolin’s naturalism—and both challenge the Peripatetic eternal order—the difference becomes sharp at the level of a decision mechanism (next subsection).

7.4. The Decision Principle Question: Fine-Tuning the “Logos”

The question. In a relational network, if multiple futures are equally possible at a vertex, what selects the one that becomes actual?

Pure randomness preserves openness but weakens direction/meaning.

Immanent biases/constraints can guide outcomes but risk smuggling in determinism.

Without appealing to a transcendent “mind,” Smolin needs an immanent decision principle to explain directionality and selection (Smolin 2013, 71–103). The principle of precedence is relevant here: past instances/events constrain future possibilities and thereby guide outcomes—without yielding full determinism (Smolin 2013; Smolin & Unger 2015). In al-Ghazālī, this role is performed by will within tajdīd al-khalq; order is chosen and sustained in the renewal of each instant. This fine-tuning issue shapes the practical consequences of the two models.

7.5. Implications for History and Knowledge: Writing Order with Time

Stability narratives instead of necessity. Whether ʿādātullāh or law-evolution, “law” becomes a story of historical consolidation, open to rupture and renewal.

The temporality of evidence. Order and record are achievements of temporal regimes, not timeless givens.

Responsibility and openness. Decision-laden time writes ethical/political accountability into history; order (via divine renewal or law-evolution) appears in future-making practices (e.g., in environmental crises, collective action selects among possible futures).

Interim judgment. Smolin offers not a transcendent or eternal logos in the classical sense but a rationality that emerges and evolves within time: laws are historically shaped (e.g., by precedence and early-universe fluctuations). Al-Ghazālī grounds order in divine will (tajdīd al-khalq) and ʿādātullāh. Read together, logos appears not as a timeless essence but as a principle written by time itself. Smolin’s naturalistic evolution shares a structural (not substantive) analogy with Ashʿarī contingency and poses a clear challenge to the Peripatetic eternal order; directionality is present, but without the theological orientation supplied by al-Ghazālī’s ḥikma.

Penrose sharpens the tension around determinism without collapsing physics into it. A strong mathematical Platonist, he contends that the lawful character of physical order rests on timeless mathematical realities (Penrose 1989; 1994; 2004). Yet he also maintains that quantum processes display objective, partly stochastic, and even non-computable features (Hameroff & Penrose 2010; Penrose 1994). Thus the claim that “determinism is governed by timeless equations” is overgeneral; a more accurate formulation is that “lawfulness is framed by timeless mathematical structures” (Penrose 2004). Penrose’s sense of “transcendence” is not theological but oriented to Platonic mathematical reality (Penrose 1989; 1994). In parallel, for contemporary empirical evidence that order can emerge endogenously within processual interactions, see Guler (2025).

8. Conclusion: Real Time as Ontological Choice

This article has argued that real time is best understood as an ontological decision process—a horizon in which novelty, agency, and responsibility become possible. Through an analogical (non-reductive) comparison, al-Ghazālī’s theology of ongoing creation (tajdīd al-khalq) and Smolin’s temporal naturalism jointly undermine timeless determinism while converging on a view of temporality that is open, directional, and generative. Their metaphysical grounds diverge—volitional on the one side, naturalistic on the other—yet their shared structural commitments (discreteness, contingency, evolving order) relocate both explanation and evidence inside time rather than above it.

Implications for the Philosophy of History and the History of Knowledge

Causal explanation as contingent and agent-sensitive. If order reflects ʿādātullāh or evolving law, historical causes operate under stabilized habits rather than necessities; counterfactuals gain legitimacy as probes of genuine openness.

Evidence as a temporal achievement. Records and regularities persist through temporally structured regimes (institutional, material, cosmological), not by nature’s essence; archival stability is historically produced, not timelessly given.

Laws as narratives of stabilization. Whether “divine habit” or “law evolution,” regularities read as histories of consolidation—open to rupture, decay, and renewal.

Responsibility within becoming. Decision-laden time writes ethical and political accountability into history; necessity cannot absolve agents when futures remain genuinely open.

Methodological pluralism with guardrails. Cross-domain analogies (theology ↔ physics) clarify metaphysical stakes when kept structural (not reductionist) and when disanalogies are explicit.

Limitations and Guardrails

The analogies here are formal, not substantive: ānāt are volitional-theological, not empirical time quanta; likewise, Planck-scale speculation does not vindicate kalām.

Presentism and law-evolution remain contested in physics and metaphysics; claims are programmatic, not definitive.

Translational risks persist: theological terms (e.g., ikhtiyārī, ʿādātullāh) do not map one-to-one onto naturalistic categories.

A Research Program Ahead

Comparative metaphysics of decision. Can a non-theological selection principle deliver directed becoming without lapsing into hidden determinism or mere randomness?

Historiography of regularities. Case studies tracing how scientific, legal, or liturgical “laws” stabilize and destabilize across centuries, testing the thesis that order is historical.

Bridging formalisms. Process- or category-theoretic tools to model selection across instants (volitional vs. immanent biases) while preserving openness.

Ethics of contingency. If the future is genuinely open, design normative frameworks that treat responsibility under uncertainty as foundational rather than exceptional.

Take-home. Whether grounded in divine will or in nature’s self-organization, both frameworks treat time as the constitutive medium in which worlds—and laws—are made. The deepest common lesson is not that theology reduces to physics (or vice versa), but that freedom and novelty are ontological features of the real. To do justice to history and to knowledge alike, our explanations must therefore be written in the tense that time itself permits: future-creating, decision-laden, and open.

Author Contributions

This is a single-author article. Author is solely responsible for all contribution roles: Conceptualization; Methodology (comparative/analogical); Investigation; Writing—Original Draft; Writing—Review & Editing; Visualization (

Figure 1;

Table 1 and

Table 2). The author has approved the manuscript and is accountable for all content.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) has been covered personally by the author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I thank my colleagues for their constructive feedback on earlier drafts. A large language model (ChatGPT, OpenAI) was used solely for language refinement and clarity; content development, reasoning, fact-checking, citations, and final revisions are entirely the author’s responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad. n.d. Iḥyāʾ ʿUlūm al-Dīn, Book I: Kitāb al-ʿIlm. (Original work in Arabic.).

- Al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid. 1998. The Niche of Lights (Mishkāt al-anwār). Translated by David Buchman. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press.

- Al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad. 2000. The Incoherence of the Philosophers: A Parallel English–Arabic Text (Tahāfut al-Falāsifa). Translated by Michael E. Marmura. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press.

- Alon, Ilai. 1980. “Al-Ghazālī on Causality.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 100 (4): 395–405. [CrossRef]

- Aristotle. 1984. The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation. Edited by Jonathan Barnes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Avicenna. 2009. The Physics of The Healing: Books I & II. A Parallel English–Arabic Text. Translated by Jon McGinnis. Provo, UT: BYU Press.

- Barbour, Julian. 1999. The End of Time. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Born, Max. 1971. The Born–Einstein Letters: Correspondence between Albert Einstein and Max and Hedwig Born from 1916 to 1955. London: Macmillan.

- Burrell, David B., Carlo Cogliati, Janet Martin Soskice, and William R. Stoeger, eds. 2010. Creation and the God of Abraham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Sean. 2010. From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time. New York: Dutton.

- Dallal, Ahmad. 2010. Islam, Science, and the Challenge of History. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Dhanani, Alnoor. 1994. The Physical Theory of Kalām: Atoms, Space, and Void in Basrian Muʿtazilī Cosmology. Leiden/New York: E. J. Brill.

- Erdoğan, İbrahim Halil, and Sema Eryücel. 2024. “The Concept of Divine Revelation According to Ibn Sīnâ and al-Ghazālī: A Comparative Analysis.” Religions 15 (11): 1383. [CrossRef]

- Frank, Richard M. 1992. Creation and the Cosmic System: Al-Ghazālī & Avicenna. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter.

- Goodman, Lenn E. 1978. “Did Al-Ghazālī Deny Causality?” Studia Islamica 47: 83–120. [CrossRef]

- Griffel, Frank. 2009. Al-Ghazālī’s Philosophical Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Guler, Adil. 2025. “Thermodynamic and Structural Signatures of Arginine Self-Assembly Across Concentration Regimes.” Processes 13(7): 1998. [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1962. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Kant, I. (1996a). Practical philosophy (M. J. Gregor, Trans. & Ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Kant, I. (1996b). Religion and rational theology (A. W. Wood & G. di Giovanni, Eds.). Cambridge University Press.

- Landauer, Rolf. 1961. “Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process.” IBM Journal of Research and Development 5 (3): 183–191. [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, Robert B. 1959. “Entropy Consumption and Values in Physical Science.” American Scientist 47 (3): 377–392.

- Marmura, Michael E. 1981. “Al-Ghazālī’s Second Causal Theory in the 17th Discussion of his Tahāfut.” In Islamic Philosophy and Mysticism, edited by Parviz Morewedge, 85–112. Delmar, NY: Caravan Books.

- McTaggart, J. M. E. 1908. “The Unreality of Time.” Mind 17 (68): 457–474. [CrossRef]

- Ormsby, Eric. 1984. Theodicy in Islamic Thought: The Dispute over al-Ghazālī’s “Best of All Possible Worlds”. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [CrossRef]

- Parrondo, Juan M. R., Jordan M. Horowitz, and Takahiro Sagawa. 2015. “Thermodynamics of Information.” Nature Physics 11: 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1989). The emperor’s new mind: Concerning computers, minds, and the laws of physics. Oxford University Press.

- Penrose, R. (1994). Shadows of the mind: A search for the missing science of consciousness. Oxford University Press.

- Penrose, R. (2004). The road to reality: A complete guide to the laws of the universe. Vintage Books.

- Penrose, Roger. 2010. Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. London: Bodley Head.

- Price, Huw. 1996. Time’s Arrow and Archimedes’ Point. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Prigogine, Ilya, and Isabelle Stengers. 1984. Order Out of Chaos. New York: Bantam.

- Rovelli, Carlo. 2004. Quantum Gravity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rovelli, Carlo. 2018. The Order of Time. Translated by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell. New York: Riverhead Books.

- Shannon, Claude E. 1948a. “A Mathematical Theory of Communication, Part I.” Bell System Technical Journal 27 (3): 379–423. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, Claude E. 1948b. “A Mathematical Theory of Communication, Part II.” Bell System Technical Journal 27 (4): 623–656. [CrossRef]

- Smolin, Lee. 2013. Time Reborn: From the Crisis in Physics to the Future of the Universe. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Smolin, Lee. 2019. Einstein’s Unfinished Revolution: The Search for What Lies Beyond the Quantum. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- Smolin, Lee, and Roberto Mangabeira Unger. 2015. The Singular Universe and the Reality of Time: A Proposal in Natural Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. e-book DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Tegmark, Max. 2003. “Parallel Universes.” Scientific American 288 (5): 40–51.

- Vilenkin, Alexander. 1982. “Creation of Universes from Nothing.” Physics Letters B 117 (1–2): 25–28. [CrossRef]

- Zurek, Wojciech H. 2009. “Quantum Darwinism.” Nature Physics 5: 181–188. [CrossRef]

| i |

Tajdīd al-khalq: In Ashʿarī kalām, the cosmos is re-created by God at every instant; causality depends on the divine will (Griffel 2009). |

| ii |

Structural isomorphism denotes a relation-preserving one-to-one mapping between two theoretical structures: it preserves relations, not the identity of individual elements. It is thus stronger than analogy yet weaker than ontological identity. |

| iii |

Contingency here has two axes: (i) “creates what He wills” (yakhluqu mā yashāʾ; Q 3:47; 28:68; 42:49–50) — selection among possibles (object axis); (ii) “as He wills” (kayfa yashāʾ; Q 3:6; cf. 25:2; 87:2) — specification of mode/form, measure, and proportion (modal axis). Thus, divine will determines both what exists (al-Murīd) and how it exists (al-Muqaddir, al-Muṣawwir). In the Tahāfut, al-Ghazālī targets emanationist necessitarianism and the world’s eternity rather than modern evolutionism, since these suspend divine ikhtiyār. He therefore reserves real taʾthīr to God and reads secondary causes (asbāb) as habitual connections within ʿādātullāh (al Ghazālī 1998; al Ghazālī 2000; Ormsby 1984; Griffel 2009; Burrell 2010). Regularities arise from wise will, not intrinsic essences: yafʿalu’Llāhu mā yashāʾ signals will bounded by ḥikma, not caprice. See kasb: divine creation does not cancel human acquisition. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).