Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Benchmark Simulation Models of Wastewater Treatment Plants: The BSM1 Benchmark

2.1. Brief Description of the BSM1, BSM1_LT and BSM2 Benchmarks

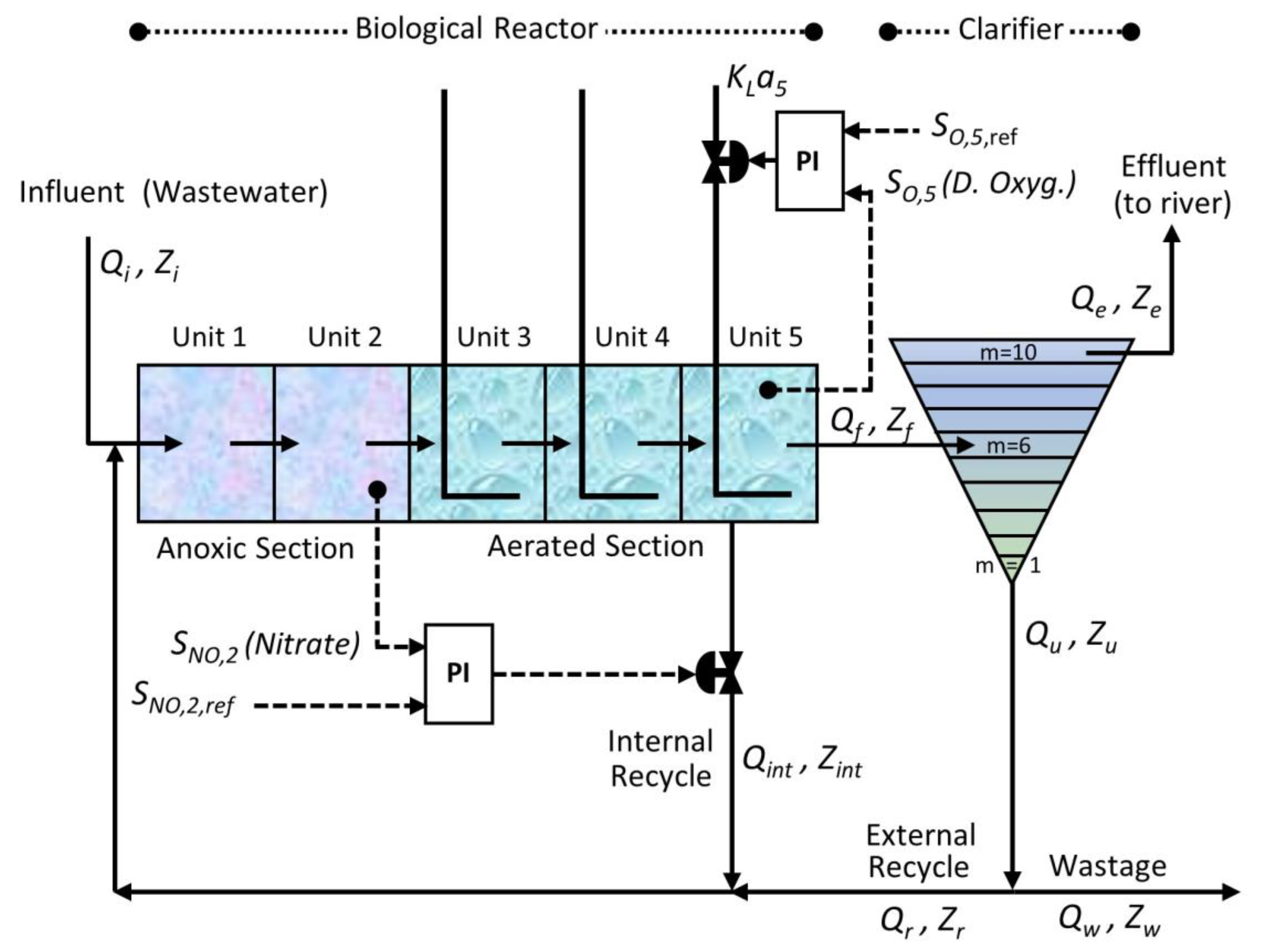

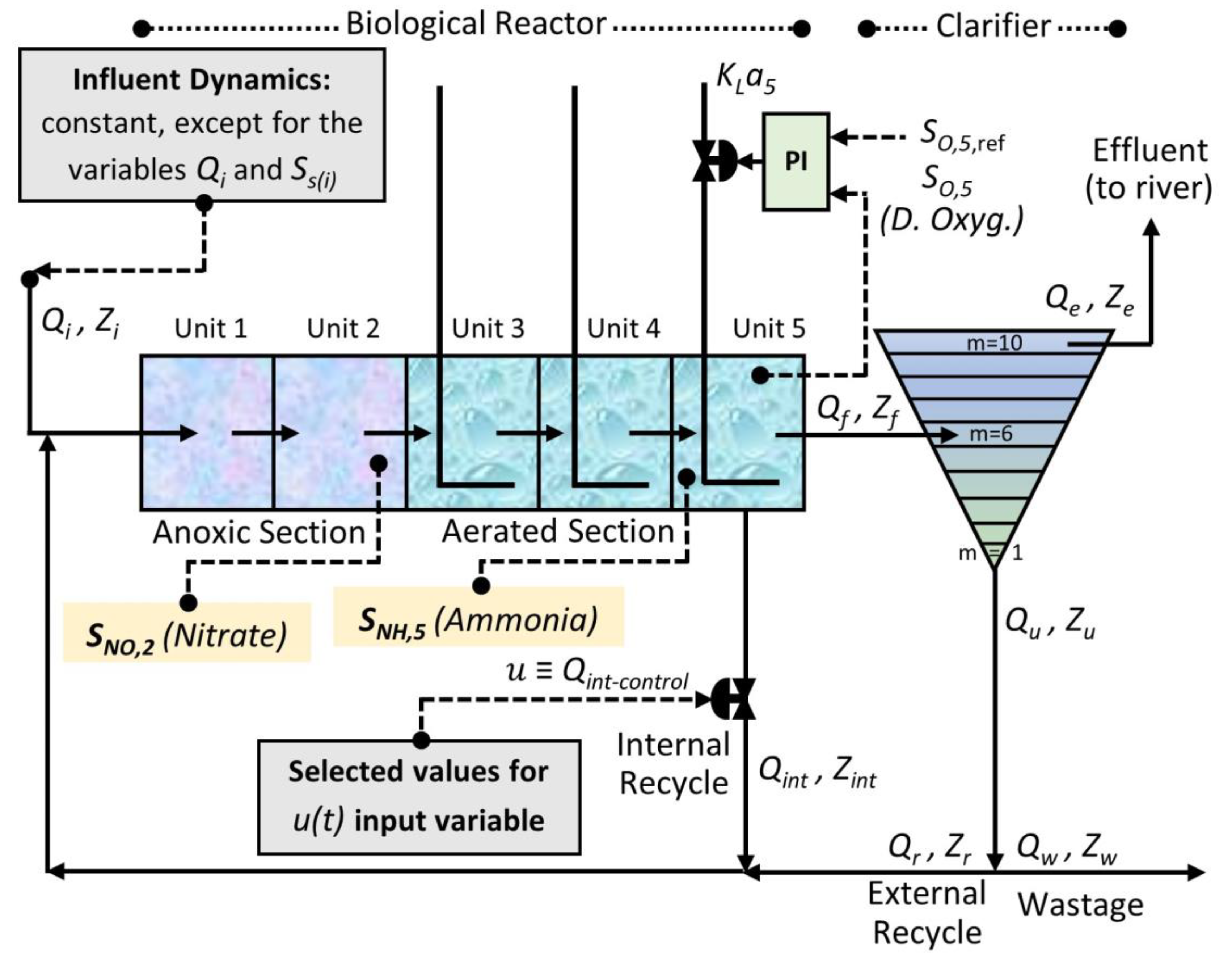

2.2. BSM1 Benchmark: Structure, Features, and Default Control Strategy

3. Alternative Control Configuration for the BSM1 Benchmark: Use of the FMBPC/CLP Predictive Control Strategy

3.1. FMBPC Predictive Control Strategy

3.2. CLP-MPC Predictive Control Strategy

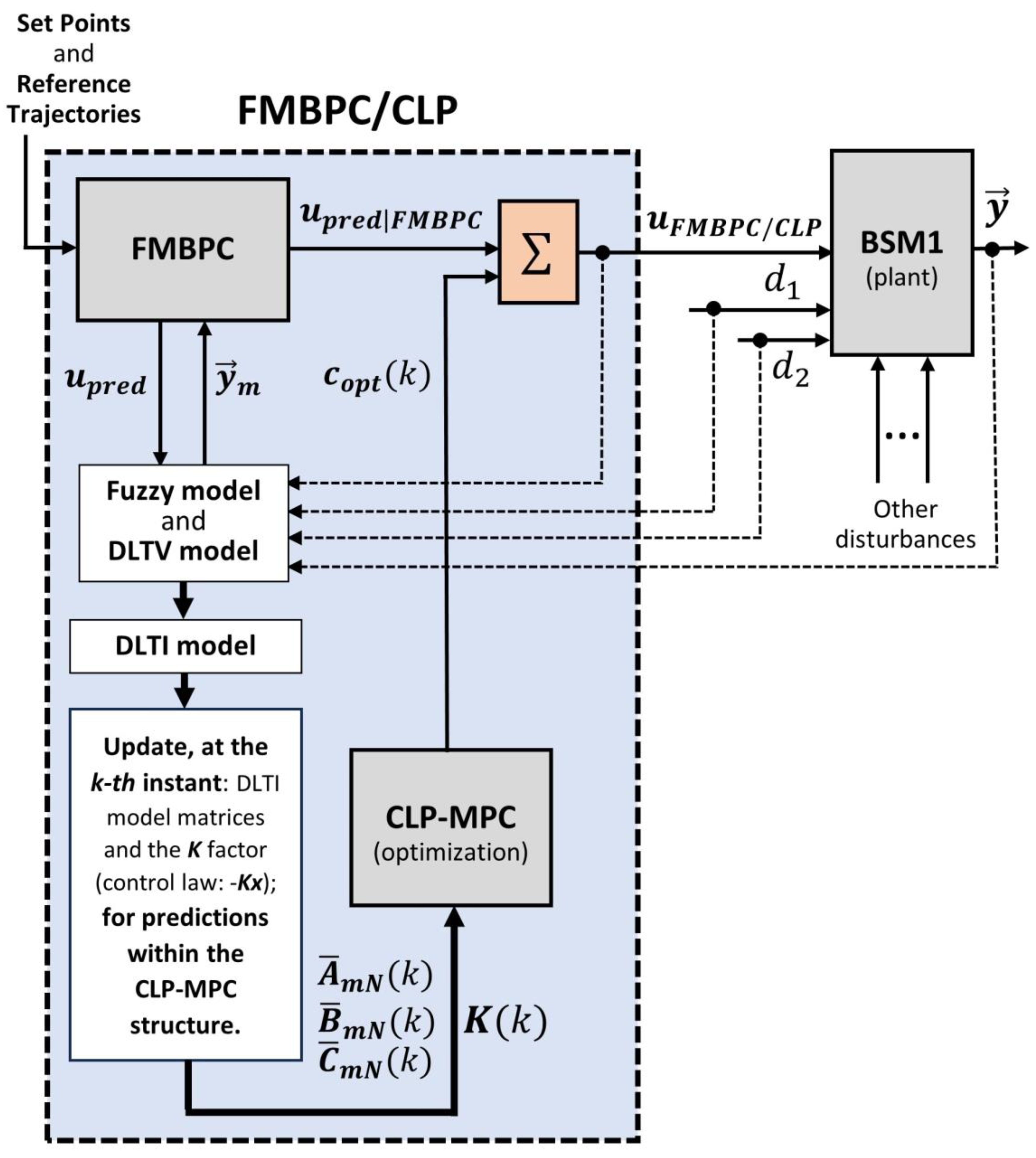

3.3. FMBPC/CLP Mixed Predictive Control Strategy: Implementation

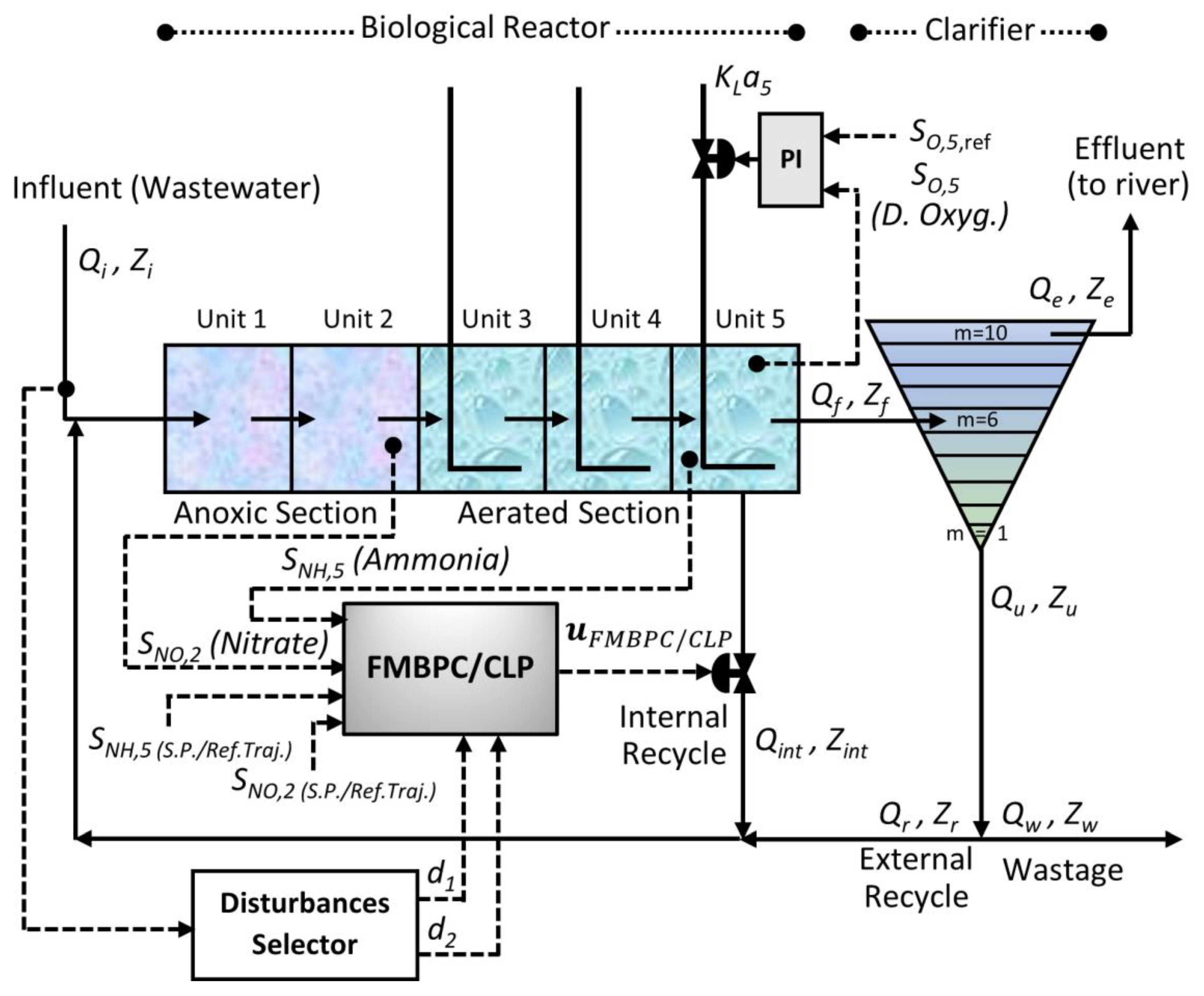

3.4. Integration of the FMBPC/CLP Strategy in the Control System of the BSM1 Benchmark

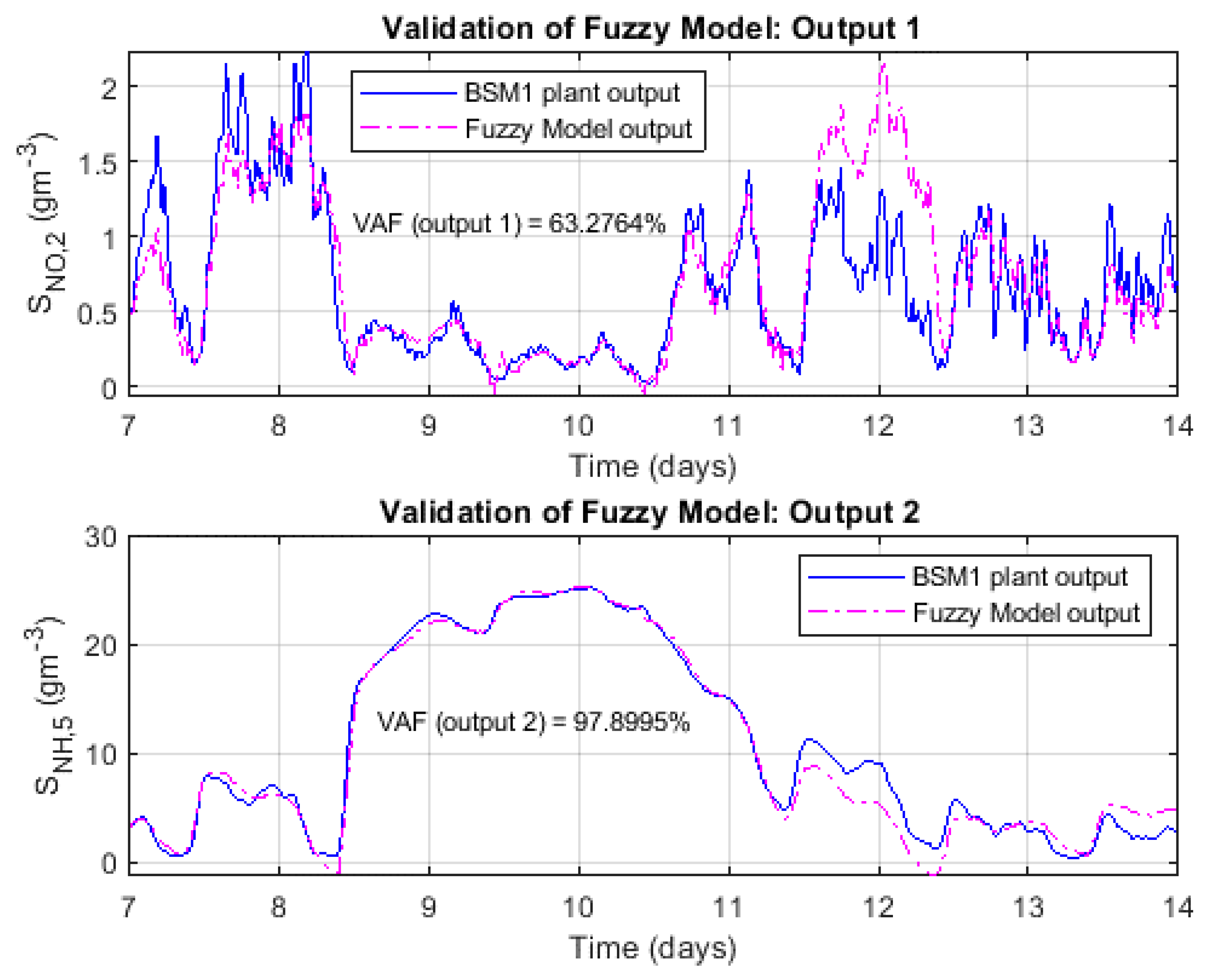

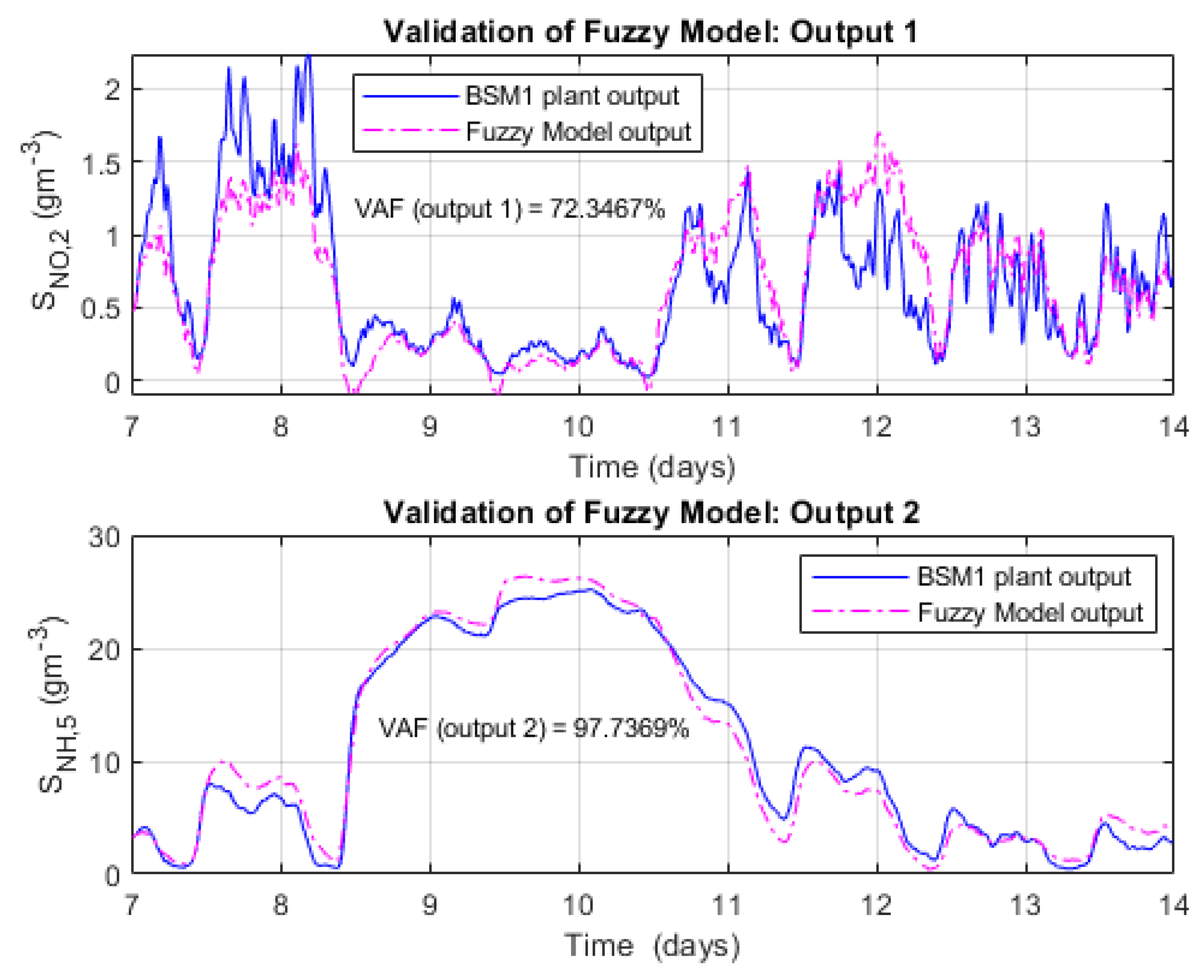

4. Fuzzy Identification of WWTP Represented by the BSM1 Benchmark

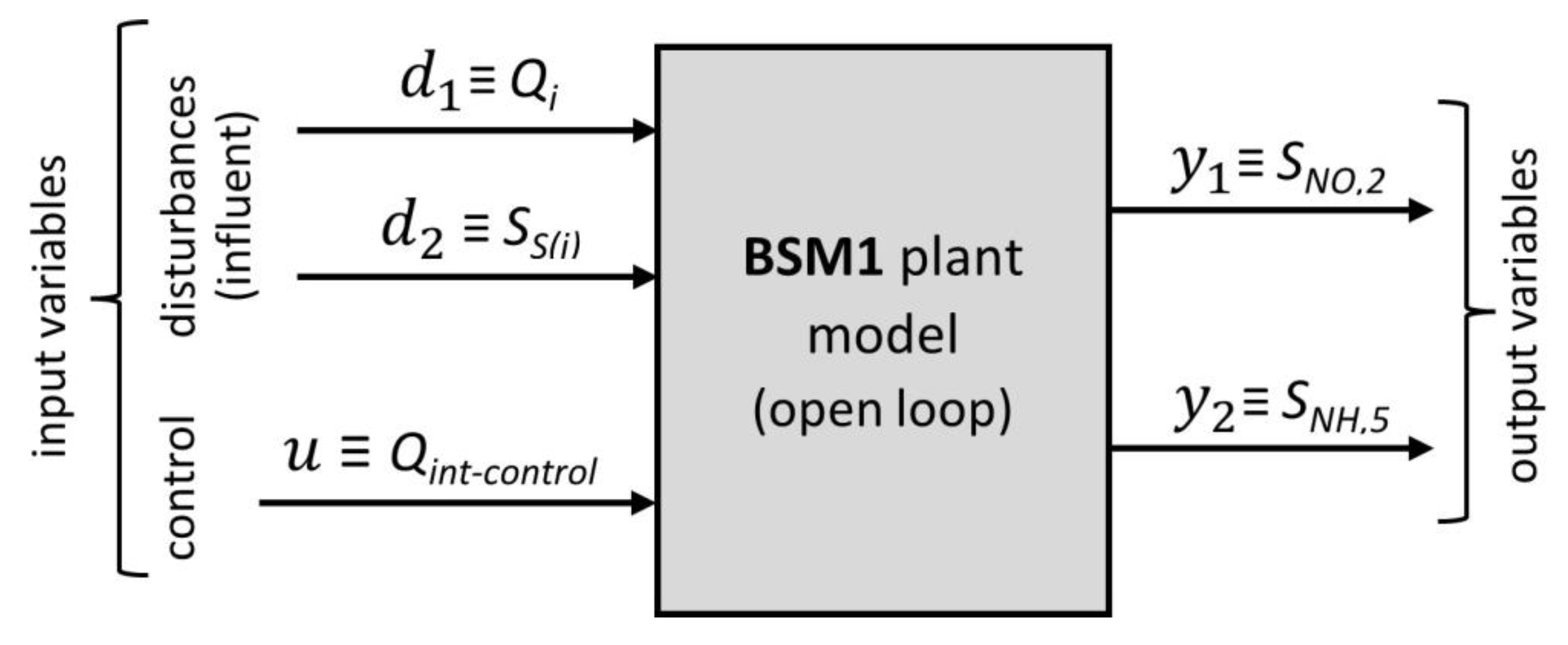

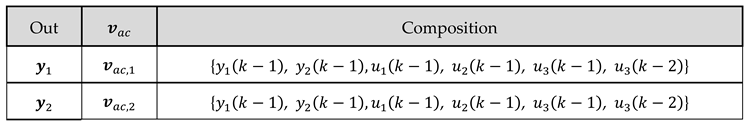

4.1. Representative Base Model of the Plant: Input-Output Structure

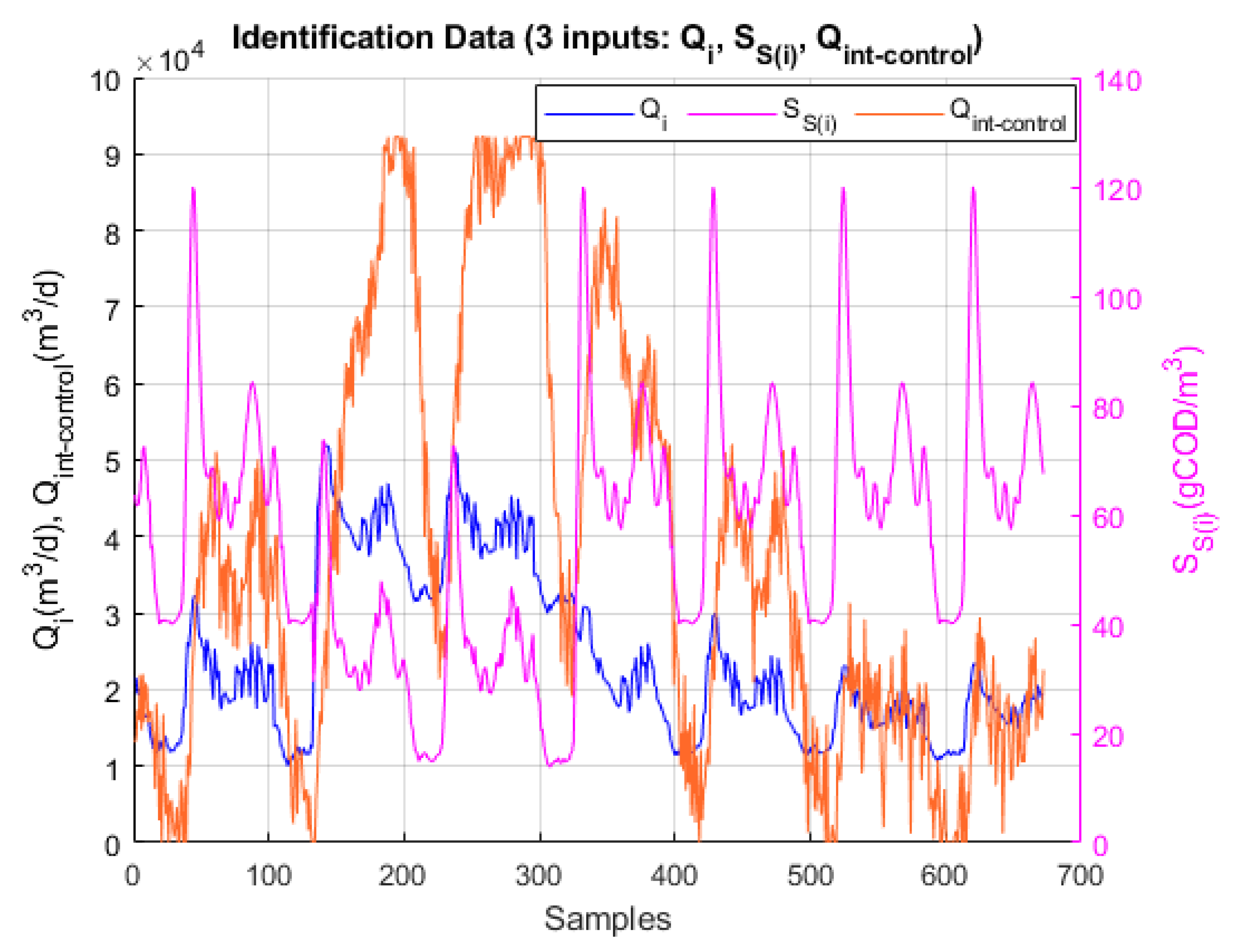

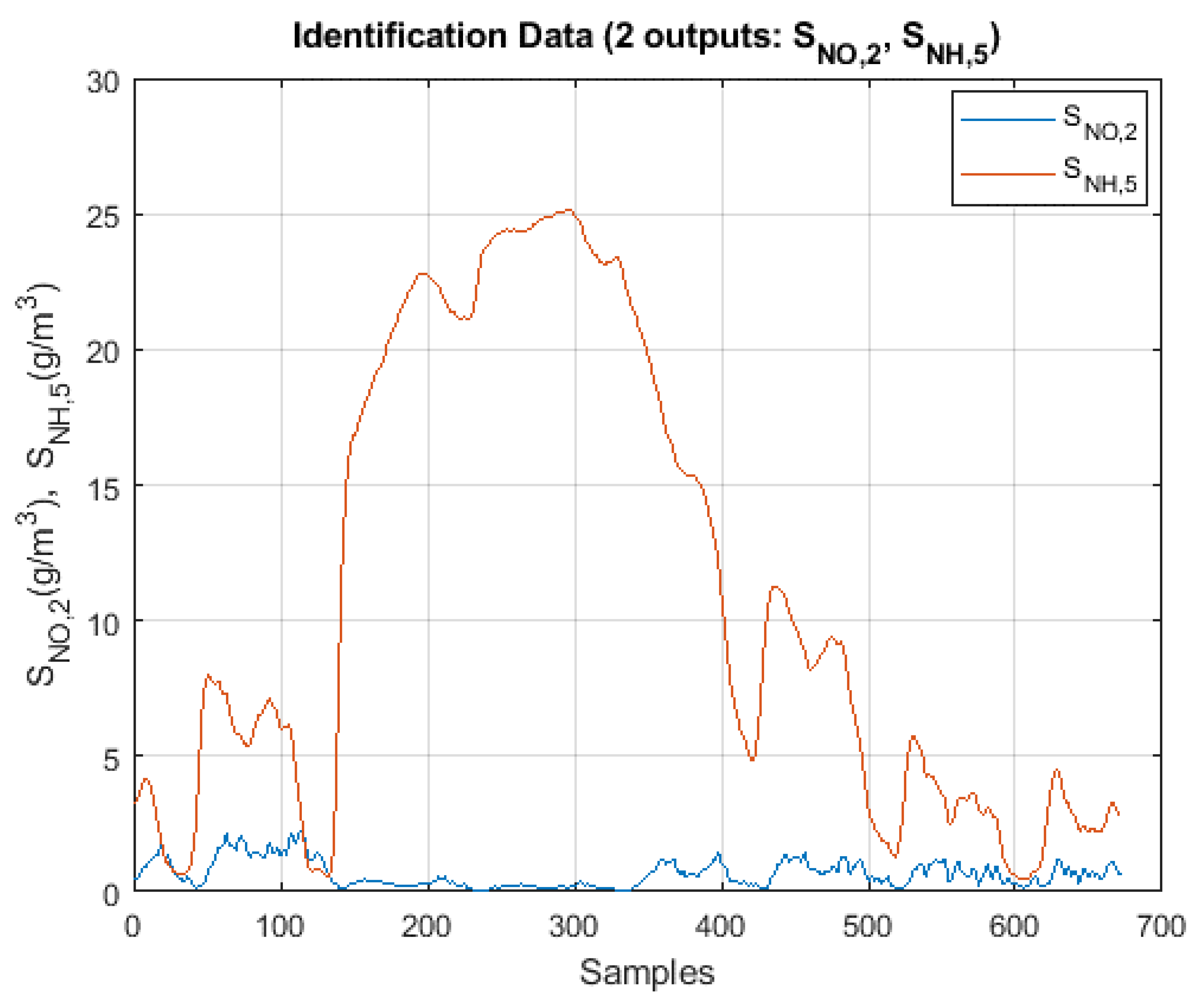

4.2. Obtaining Numerical Input-Output Data from the BSM1 Plant in Open Loop

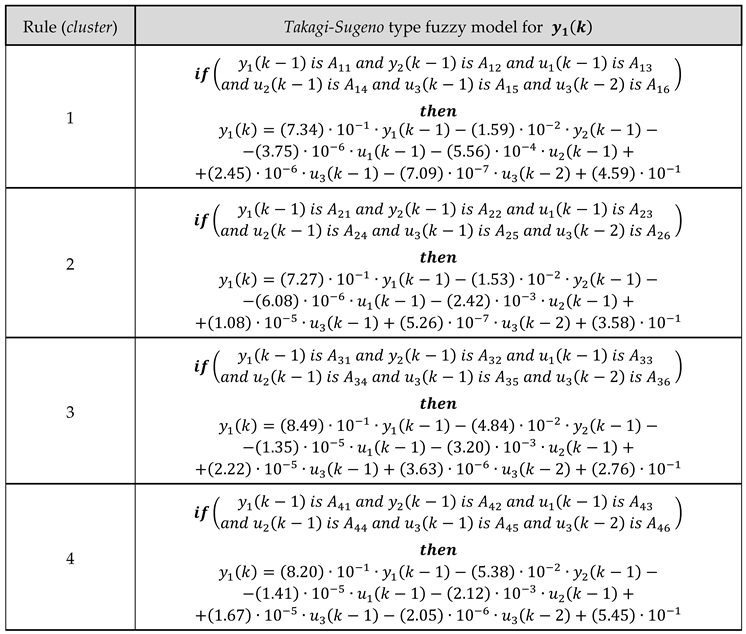

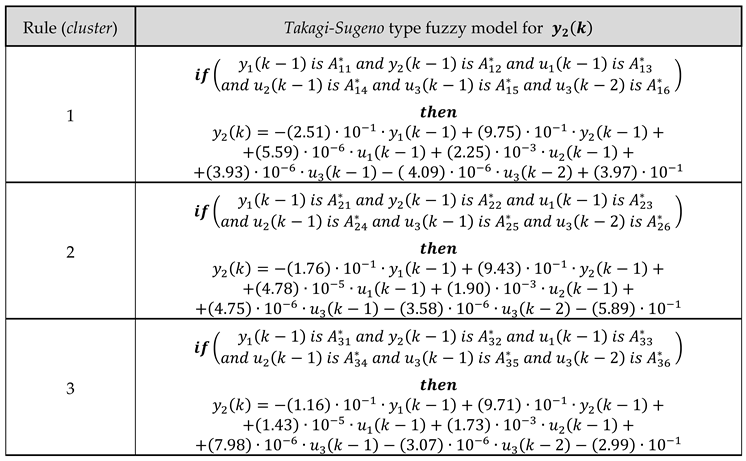

4.3. Identification of the Fuzzy Model Using the FMID Software Tool

5. Control Experiments with the BSM1 Benchmark Using the FMBPC/CLP Strategy: Simulation Results and Discussion

- Abbreviations: react. unit is the reactor unit number; Simul. interval is the Simulation interval (0 to 14 days); s.p. is the set point;

- PI: special case of the Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control algorithm. The values and the units of the parameters of the different PI control algorithms included in this table are the same as those considered in the default control configuration of the BSM1 benchmark

- FMBPC/CLP: mixed strategy of Fuzzy Model-Based Predictive control and Closed-Loop Predictive Control (with constraints)

- Q1, Q2, R, nc, |Δu|máx: parameters corresponding to the CLP-MPC strategy (see the structure of the CLP-MPC strategy in section 3.2 of this article); being Q1, Q2 and R, tuning parameters corresponding to the cost function , nc, the number of steps of mode 1, and |Δu|máx=, the maximum bound (in absolute value) of the control action increments (incremental prediction model) [26,27]

- Set point and units of the oxygen control loop (fifth tank): SO,5|s.p.=2 mg (-COD)/l (equivalent to: 2 g (-COD)/m3)

- Set point and units of the nitrate control loop (second tank): SNO,2|s.p.=1 mg N/l (equivalent to: 1 g N/m3)

- Set point and units of the ammonia control loop (fifth tank): SNH,5|s.p.= 0.67 mg N/l (equivalent to: 0.67 g N/m3)

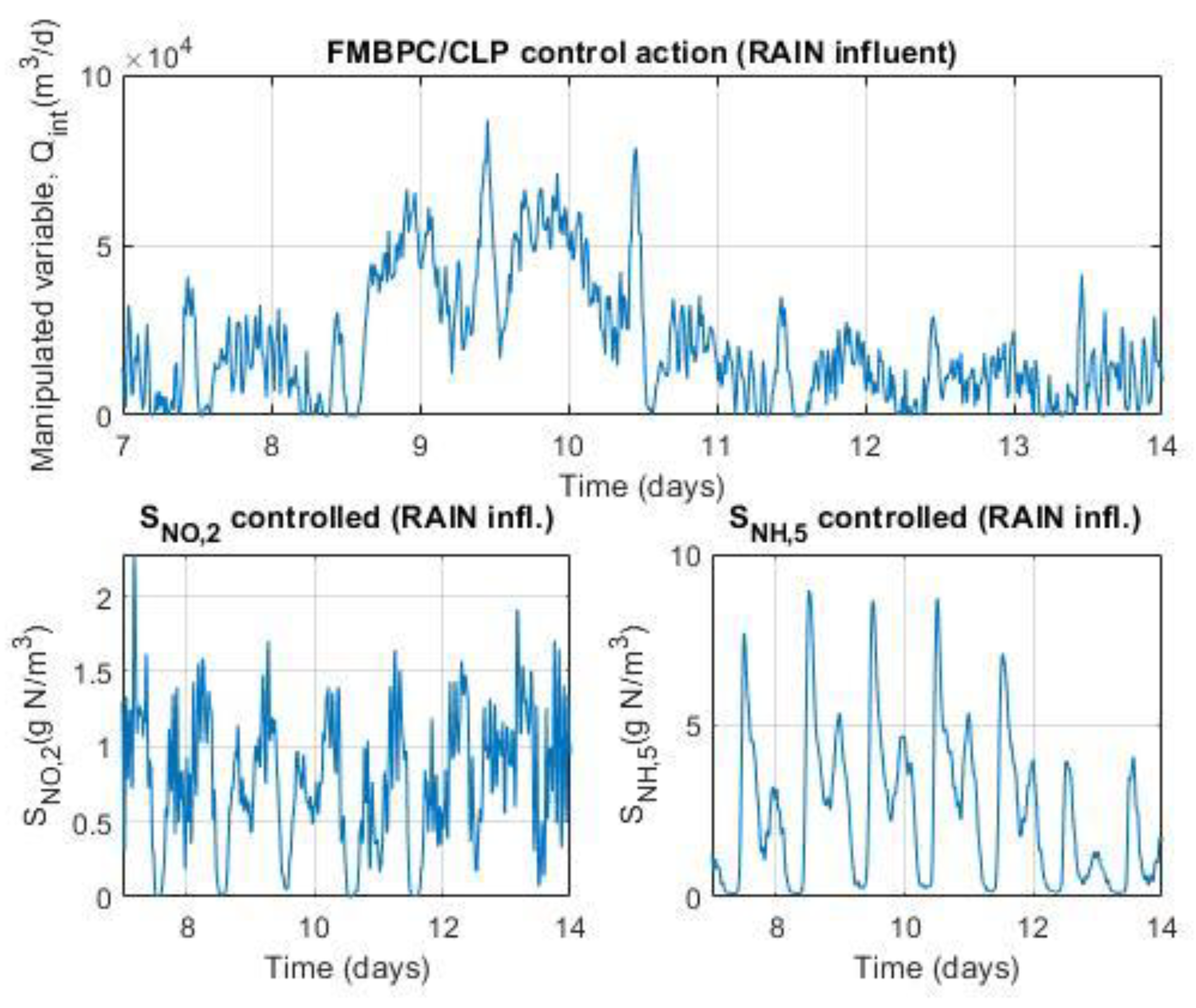

5.1. Behavior of the BSM1 Plant Controlled by the FMBPC/CLP Strategy

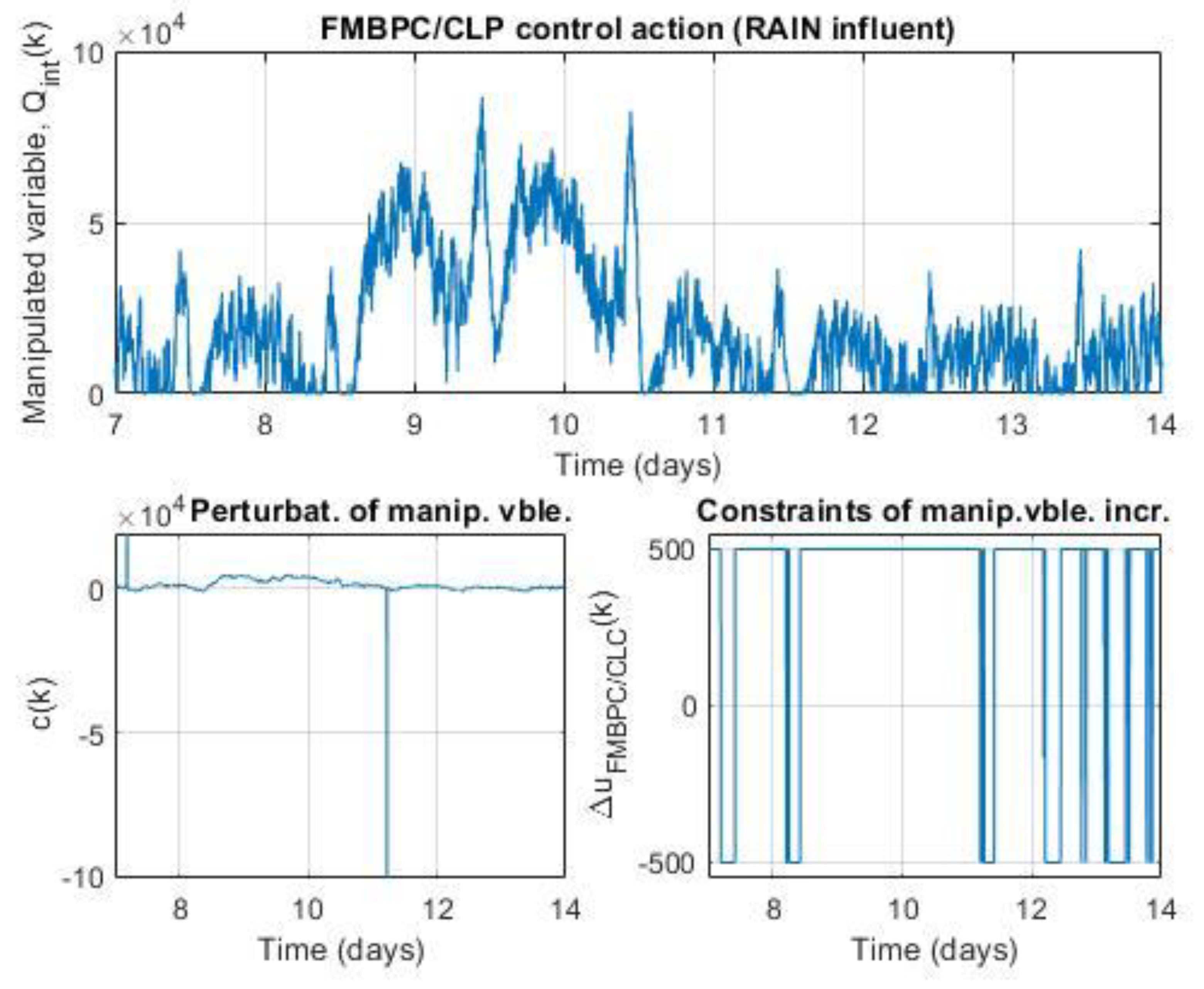

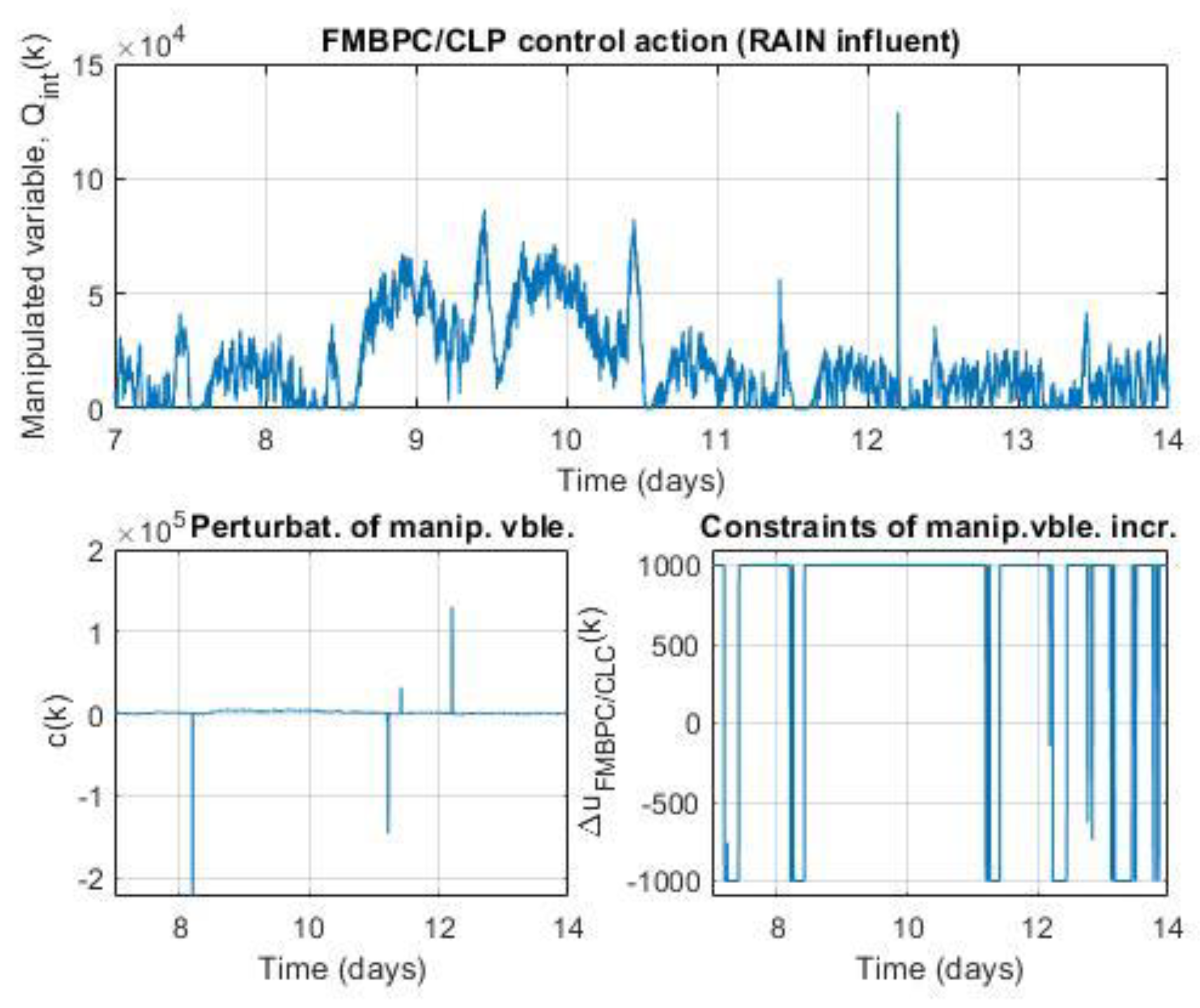

5.2. Handling Constraints in Control Action with the FMBPC/CLP Strategy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | VAF: percentile Variance Accounted For between two signals |

References

- Pell, M.; Wörman, A. Biological Wastewater Treatment Systems. Compr. Biotechnol., 2011, 6, 275–290. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Al, R.; Behera, C.R.; Sin, G. Process Synthesis, Design, and Control of Wastewater Treatment Plants. In Reference Module in Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering, 2018; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–14.

- Wahlberg, E.J. Activated Sludge Wastewater Treatment. Process Control & Optimization for the Operations Professional; DEStech Publications, Inc.: Lancaster, PA, USA, 2019.

- M. Faisal; Kashem M. Muttaqi; Danny Sutanto; Ali Q. Al-Shetwi; Pin Jern Ker, M.A. Hannan. Control technologies of wastewater treatment plants: The state-of-the-art, current challenges, and future directions. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 181, 113324. [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, R.; Santín, I.; Pedret, C. Control y Operación de Estaciones Depuradoras de Aguas Residuales: Modelado y Simulación. Revista Iberoamericana de Automática e Informática industrial 2017, 14(3), pp. 217–233. [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, R.; Santín, I.; Pedret, C. Control en Estaciones Depuradoras de Aguas Residuales: Estado actual y perspectivas. Revista Iberoamericana de Automática e Informática industrial 2017, 14(4), pp. 329–345. [CrossRef]

- E. F. Camacho; C. Bordons. Model Predictive Control; Springer: London, UK, 2004.

- J. M. Zamarreño; P. Vega. Identification and Predictive Control of a Melter Unit used in the sugar Industry. Artificial Intelligence in Engineering 1997, Vol. 11, Issue 4, pp 365-373.

- Wenhao Shen; Xiaoquan Chen; M.N. Pons; J.P. Corriou. Model predictive control for wastewater treatment process with feedforward compensation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2009, Volume 155, Issues 1–2, pp 161-174.

- Ocampo-Martínez, Carlos. Model predictive control of wastewater systems. Springer Science & Business Media, 2010.

- Han Hong-gui; Zhang, Lu; Qiao, Jun-fei. Data-based predictive control for wastewater treatment process. Ieee Access 2017, vol. 6, 1498-1512.

- J. F. Qiao; G. T. Han; H. G. Han; C. L. Yang; W. Li. Decoupling Control for Wastewater Treatment Process Based On Recurrent Fuzzy Neural Network. Asian Journal of Control 2019, 21, no. 3, 1270–1280.

- Aponte-Rengifo, Oscar; Francisco, M.; Vilanova, Ramon; Vega, Pastora; Revollar, Silvana. Intelligent Control of Wastewater Treatment Plants Based on Model-Free Deep Reinforcement Learning. Processes 2023, 11, 2269. [CrossRef]

- Eshbobaev, J.; Norkobilov, A.; Usmanov, K.; Khamidov, B.; Kodirov, O.; Avezov, T. Control of Wastewater Treatment Processes Using a Fuzzy Logic Approach. Eng. Proc. 2024, 67, 39.

- YE, Chengyan; Tran, Thu Thao Thi; Yang, Yu. Machine learning and genetic algorithm for effluent quality optimization in wastewater treatment. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2025, vol. 71, p. 107294.

- Du, S.; Sun, R.; Chen, P. Multivariable Control of Wastewater Treatment Process Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IET Control Theory Appl. 2025, 19(1): e70021. [CrossRef]

- J. Qiao, D. Chen, C. Yang and D. Li. Double-Layer Fuzzy Neural Network Based Optimal Control for Wastewater Treatment Process. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2025, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 2062-2073. [CrossRef]

- Babuška, R. Fuzzy Modeling for Control; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1998.

- Roubos, J.; Mollov, S.; Babuška, R.; Verbruggen, H. Fuzzy model based predictive control using Takagi–Sugeno models. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 1999, 22, 3–30. [CrossRef]

- Mollov, S.; Babuška, R.; Abonyi, J.; Verbruggen, H. Effective Optimization for Fuzzy Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2004, 12, 661–675. [CrossRef]

- Blažič, S.; Škrjanc, I. Design and Stability Analysis of Fuzzy Model based Predictive Control—A Case Study. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2007, 49, 279–292. [CrossRef]

- Bououden, S.; Chadli, M.; Karimi, H. An ant colony optimization based fuzzy predictive control approach for nonlinear processes. Inf. Sci. 2015, 299, 143–158. [CrossRef]

- Škrjanc, I.; Blažič, S. Fuzzy Model based Control - Predictive and Adaptive Approaches. In: Handbook on Computational Intelligence; Angelov, Plamen (Ed.); World Scientific: New Jersey, USA, 2016; Vol. I., Ch. 6, pp. 209–240. [CrossRef]

- Boulkaibet, I.; Belarbi, K.; Bououden, S.; Marwala, T.; Chadli, M. A new T-S fuzzy model predictive control for nonlinear processes. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 88, 132–151. [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, P. M., Vega, P. Analytical Fuzzy Predictive Control Applied to Wastewater Treatment Biological Processes. Complex. 2019, 5720185. [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, P. M., Vega, P. Practical Computational Approach for the Stability Analysis of Fuzzy Model-Based Predictive Control of Substrate and Biomass in Activated Sludge Processes. Processes 2021, 9(3), 531. [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, P.M.; Vega, P. Integración de la estrategia FMBPC en una estructura de Control Predictivo en Lazo Cerrado. Aplicación al control de fangos activados. Revista Iberoamericana de Automática e Informática Industrial (RIAI) 2021, 19(1), 13-26. [CrossRef]

- Alex, J.; Benedetti, L.; Copp, J.; Gernaey, K.; Jeppsson, U.; Nopens, I.; Pons, M.; Rieger, L.; Rosen, C.; Steyer, J.; P. Vanrolleghem, P.; Winkler, S. Benchmark Simulation Model No. 1 (BSM1), IWA Task Group on Benchmarking of Control Strategies for WWTPs; Cod.: LUTEDX-TEIE 7229. 1-62; Department of Industrial Electrical Engineering and Automation, Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229091128_Benchmark_Simulation_Model_no_1_BSM1.

- Corriou, Jean Pierre; M. N. Pons. Model predictive control of wastewater treatment plants: Application to the BSM1 benchmark. Computer-aided chemical engineering 18, 2004, 625-630.

- Cristea, Vasile-Mircea; Pop, Cristian; Agachi, Paul Serban. Model Predictive Control of the waste water treatment plant based on the Benchmark Simulation Model No. 1-BSM1. Computer Aided Chemical Engineering 2008, Elsevier, Volume 25, 2008, p. 441-446. [CrossRef]

- Wenhao Shen; Xiaoquan Chen; J.P. Corriou. Application of model predictive control to the BSM1 benchmark of wastewater treatment process. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2008, Volume 32, Issues 12, 22, pp 2849-2856.

- M. Francisco; P. Vega; S. Revollar. Model Predictive Control of BSM1 benchmark of wastewater treatment process: A tuning procedure. 2011 50th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control and European Control Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 2011, pp. 7057-7062. [CrossRef]

- Revollar, S.; Vega, P.; Vilanova, R.; Francisco, M. Optimal Control of Wastewater Treatment Plants Using Economic-Oriented Model Predictive Dynamic Strategies. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 813. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodelo, K.; Francisco, M.; Alvarez, H.; Vega, P.; Revollar, S. Collaborative Control Applied to BSM1 for Wastewater Treatment Plants. Processes 2020, 8, 1465. [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, A.; Pani, A.K. Machine learning approaches for data-driven process monitoring of biological wastewater treatment plant: A review of research works on benchmark simulation model No. 1(BSM1). Environ Monit Assess 2023, 195, 916. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Yongzhi; Zhao, Haifeng. Study of Dissolved Oxygen Concentration Control by the BSM1 Benchmark Model. International Core Journal of Engineering 2025, vol. 11, no 4, p. 542-547.

- Francisco, M.; Vega, P. Diseño Integrado de Procesos de Depuración de Aguas utilizando Control Predictivo Basado en Modelos. Revista Iberoamericana de Automática e Informática Industrial (RIAI) 2009, 3(4), 87-97. https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/146245.

- Takagi, T.; Sugeno, M. Fuzzy identification of systems and its applications to modeling and control. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1985, 15, 116–132. [CrossRef]

- Richalet, J. Industrial applications of model based predictive control. Automatica 1993, 29, 1251–1274. [CrossRef]

- Richalet, J.; O’Donovan, D. Predictive Functional Control: Principles and Industrial Applications; Springer: London, UK, 2009.

- Haber, R.; Rossiter, J.; Zabet, K. An alternative for PID control: Predictive Functional Control—A tutorial. In Proceedings of the 2016 American Control Conference (ACC), Boston, MA, USA, 6–8 July 2016; pp. 6935–6940.

- Rossiter, J.A. Model-Based Predictive Control: A Practical Approach; CRC Press-Taylor & Francis Inc.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Alex J.; Beteau J.F.; Copp J.B.; Hellinga C.; Jeppsson U.; Marsili-Libelli S.; Pons M.N.; Spanjers H.; Vanhooren H. (1999). Benchmark for evaluating control strategies in wastewater treatment plants. In Proceedings of the ECC'99 (European Control Conference), Karlsruhe, Germany, 31 Aug 1999—Sep 1999. [CrossRef]

- Pons, M.N.; Spanjers, H.; Jeppsson, U. Towards a benchmark for evaluating control strategies in wastewater treatment plants by simulation. Comp. Chem. Eng. 1999, 23s, 403–406. [CrossRef]

- Copp J. (Ed.). The COST Simulation Benchmark: Description and Simulator Manual; Office for Official Publications of the European Community: Luxembourg, 2002; ISBN 92-894-1658-0. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/243774782_The_COST_Simulation_Benchmark-Description_and_Simulator_Manual.

- Rosen C.; Jeppsson U.; Vanrolleghem PA. Towards a common benchmark for long-term process control and monitoring performance evaluation. Water Sci Technol. 2004, 50(11): 41-9. PMID: 15685978. [CrossRef]

- Alex, J.; Benedetti, L.; Copp, J.; Corominas, L.; Gernaey, K.V.; Jeppsson, U.; Nopens, I.; Pons, M.N.; Rosén, C.; Steyer, J.P.; Vanrolleghem, P. Long Term Benchmark Simulation Model no. 1 (BSM1_LT). Technical Report no. 2. IWA Task Group on Benchmarking of Control Strategies for WWTPs, 2008. Retrieved from: https://wwtmodels.pubpub.org/pub/psw2ha4d/release/1.

- Alex, J., Benedetti, L., Copp, J., Gernaey, K.V., Jeppsson, U., Nopens, I., Pons, M.N., Steyer, J.P. and Vanrolleghem, P. Benchmark Simulation Model no. 2 (BSM2). Technical Report no. 3. IWA Task Group on Benchmarking of Control Strategies for WWTPs, 2008. Retrieved from: http://iwa-mia.org/benchmarking.

- Pons, M.-N., Alex, J., Benedetti, L., Copp, J. B., Gernaey, K., Jeppsson, U., Nopens, I., Rosen, C., Steyer, J.-P., & Vanrolleghem, P. Benchmark Simulation Model no. 1 (BSM1). Scientific technical report (on the final). IWA Task Group on Benchmarking of Control Strategies for WWTPs, Wastewater Modelling, 2014-2021 (last released). Retrieved from https://wwtmodels.pubpub.org/pub/web0fxkd.

- Gernaey, K. V.; Jeppsson, U.; Vanrolleghem, P. A.; Copp, J. B. (Eds.). Benchmarking of Control Strategies for Wastewater Treatment Plants. Scientific and Technical Report No. 23. IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2014-2020 (last released). [CrossRef]

- Henze, M.; Grady, C.P.L.; Gujer, W.; Marais, G.v.R.; Matsuo, T. Activated Sludge Model No. 1. Report of IAWPRC Task Group on Mathematical Modelling for Design and Operation of Biological Wastewater Treatment, IAWPRC Publishing: London SW1H 9BT, England, UK, 1987. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/243624144_Activated_Sludge_Model_No_1.

- Takács, I.; Patry, G.G.; Nolasco, D. A dynamic model of the clarification thickening process. Water Res. 1991, 25, 1263–1271. [CrossRef]

- R. Babuška, M. Setnes, S. Mollov, and P. van der Veen. Fuzzy Modeling and Identification Toolbox for use with Matlab-User’s Guide; R. Babuška, Ed., Faculty of Information Technology and Systems, Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 1998.

- R. Babuška. Fuzzy Modeling for Control; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Gustafson and W. C. Kessel. Fuzzy clustering with a fuzzy covariance matrix. 1978 IEEE Conference on Decision and Control including the 17th Symposium on Adaptive Processes, San Diego, CA, USA, 1978, pp. 761-766. [CrossRef]

| Control loop -controlled variables- (reactor unit no.) |

Control algorithm |

Input variables to the controller |

Control variables |

Manipulated variables |

|

Oxygen Control Loop SO,5 (5th unit) |

PI | SO,5 (measure) | PI output | KLa5 |

| SO,5,ref | ||||

|

Nitrate and Ammonia Control Loop SNO,2 (2nd unit) y SNH,5 (5th unit) |

FMBPC/CLP | SNO,2 (measure) | Qint | |

| SNH,5 (measure) | ||||

| SNO,2 (S.P. / Ref.Traj.) | ||||

| SNH,5 (S.P. / Ref.Traj.) | ||||

| d1 ≡ Qi | ||||

| d2 ≡ SS(i) |

| Variables | Description |

| Soluble inert organic matter | |

| Readily biodegradable substrate | |

| Particulate inert organic matter | |

| Slowly biodegradable substrate | |

| Active heterotrophic biomass | |

| Active autotrophic biomass | |

| Particulate products arising from biomass decay | |

| Oxygen | |

| Nitrate and nitrite nitrogen | |

| NH4+ + NH3 nitrogen | |

| Soluble biodegradable organic nitrogen | |

| Particulate biodegradable organic nitrogen | |

| Alkalinity | |

| Influent flow rate |

| Input/Output (role) |

Generic notation |

Physicochemical notation |

Description |

| Input 1 of 3 (disturbance) | Influent flow rate at the plant inlet | ||

| Input 2 of 3 (disturbance) | Concentration of readily biodegradable substrate in the influent | ||

| Input 3 of 3 (control) | Control of internal recirculation flow rate | ||

| Output 1 of 2 | Nitrate concentration in the second reactor unit | ||

| Output 2 of 2 | Ammonia concentration in the fifth reactor unit |

| Parameter | Values | Meaning (dynamics of the recursive model) |

|

: 4 data clusters ⇒ 4 rules : 3 data clusters ⇒ 3 rules |

||

| (Row 1) → depends on: {, } (Row 2) → depends on: {, } |

||

| (Row 1) → depends on: {, , , } (Row 2) → depends on: {, , , } |

||

| (Row 1) → inputs , , e each have one transport delay with respect to output (Row 2) → inputs , , e each have one transport delay with respect to output |

||

| Sample time (days) |

|

|

Control

Strategy |

Ammonia

(SNH) < 4 mg N/l (g N/m3) |

Total Nitrogen

(TN) < 18 mg N/l (g N/m3) |

Suspended Solids

(TSS) < 30 mg SS/l (g SS/m3) |

BOD5 < 10 mg BOD/l (g BOD/m3) |

CODtotal < 100 mg COD/l (g COD/m3) |

| FMBPC/CLP | 2.99 | 15.43 | 16.18 | 3.46 | 45.45 |

| PID | 3.23 | 14.75 | 16.18 | 3.46 | 45.43 |

|

Control

Strategy |

Ammonia Nitrogen (SNH) maximum level

violations → Limit: 4 mg N/l ( ≡ 4 g N/m3) |

Total Nitrogen (TN) maximum level

violations → Limit: 18 mg N/l ( ≡ 18 g N/m3) |

||

| number of days (%) | number of different occasions | number of days (%) | number of different occasions | |

| FMBPC/CLP | 1.78 (25.45%) | 8 | 2.04 (29.17%) | 9 |

| PID | 1.90 (27.08%) | 8 | 0.77 (11.01%) | 5 |

|

Control

Strategy |

Ammonia95

→ 95th percentile of SNH (mg N/l ≡ g N/m3) |

TN95

→ 95th percentile of TN (mg N/l ≡ g N/m3) |

TSS95

→ 95th percentile of TSS (mg SS/l ≡ g SS/m3) |

| FMBPC/CLP | 6.05 | 20.62 | 21.68 |

| PID | 8.04 | 19.14 | 21.70 |

|

Control

Strategy |

Effluent quality index

EQI (kg poll.units/day) |

Average aeration energy per day

AE (kWh/day) |

Average pumping energy per day

PE (kWh/day) |

Total operational cost Index

OCI |

| FMBPC/CLP | 8240.22 | 7203.75 | 1576.13 | 15970.64 |

| PID | 8184.73 | 7170.74 | 1937.70 | 15984.55 |

|

Control

Strategy |

Integral of square error (ISE) | Integral of absolute error (IAE) | ||

| Control of SNO,2 | Control of SNH,5 | Control of SNO,2 | Control of SNH,5 | |

| FMBPC/CLP | 1.79 | 55.97 | 2.88 | 14.30 |

| PID | 0.79 | Not controlled | 1.73 | Not controlled |

|

|

| Parameter | |||||

| Values |

| Influent data (weather type) | Case | Control loop and controlled variables (react. unit) |

Control Algorithm (manipulate variable) |

Control strategy parameters |

Simulation parameters | ||

| Set Point | Simul. interval | ||||||

| Rain weather | 1a |

Oxygen SO,5 (5th u.) |

PI1 (KLa5) | K = 25 | SO,5|s.p. = 2 | 0 to 14 (days) | |

| Ti = 0.002 | |||||||

| Tt = 0.001 | |||||||

|

Nitrate & Ammonia SNO,2 (2nd u.) SNH,5 (5th u.) |

FMBPC/CLP (Qint) | FMBPC | Fuzzy Model: FM |

SNO,2|s.p. = 1 SNH,5|s.p.= 0.67 |

|||

| ar1 = 0.76 | |||||||

| ar2 = 0.96 | |||||||

| H = 25 | |||||||

| CLP | Q1 = 1 | ||||||

| Q2 = 1 | |||||||

| R = 1 | |||||||

| nc = 42 (steps) | |||||||

| |Δu|máx = 5 | |||||||

| 1b |

Oxygen SO,5 (5th u.) |

PI1 (KLa5) | K = 25 | SO,5|s.p. = 2 | |||

| Ti = 0.002 | |||||||

| Tt = 0.001 | |||||||

|

Nitrate SNO,2 (2nd u.) |

PI2 (Qint) | K = 104 | SNO,2|s.p. = 1 | ||||

| Ti = 0.025 | |||||||

| Tt = 0.015 | |||||||

| Dry weather | 1c | Same specifications as in Case 1a (control strategy for the variables Nitrate & Ammonia: FMBPC/CLP) | |||||

| Storm weather | 1d | Same specifications as in Case 1a (control strategy for the variables Nitrate & Ammonia: FMBPC/CLP) | |||||

| Influent data (climate type) |

Case | Control loop and controlled variables (react. unit) |

Control algorithm (capable of handling constraints) |

Constraints |Δu|máx |

Simulation parameters | |

| Set Point | Simul. interval | |||||

| Rain weather | 2a |

Nitrate & Ammonia SNO,2 (2nd u.) SNH,5 (5th u.) |

FMBPC/CLP | |Δu|máx=5 |

SNO,2|s.p.=1 SNH,5|s.p.= 0.67 |

0 to 14 (days) |

| 2b | -ídem- | -ídem- | |Δu|máx=500 | -ídem- | ||

| 2c | -ídem- | -ídem- | |Δu|máx=1000 | -ídem- | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).