Introduction

Electronic medical record (EMR) systems have been widely adopted in the healthcare domain and have significantly improved patient care and safety while reducing the cost of healthcare delivery [

1]. However, some challenges have arisen alongside these advancements, including data quality issues such as duplicated patient records. Uganda operates a decentralized system of antiretroviral therapy (ART) service delivery where people living with HIV (PLHIV) can receive ART treatment at any accredited health facility across the country, resulting in duplicated records of unique PLHIV receiving drug refills. Patient record matching across different health facilities is challenging due to the lack of universally accepted unique identifiers.

While solutions such as fingerprint-based systems and national identification numbers (NINs) have been implemented to support patient identification, gaps remain in their coverage and integration with health information systems. Uganda’s National Identification and Registration Authority (NIRA) has made substantial progress, issuing over 17.5 million IDS and covering approximately 87.6% of adults aged 16 and above [

2]. However, incomplete NIN capture in health records and technical limitations with fingerprint devices in some settings still pose challenges for consistent record linkage [

3,

4].

The patient matching or deduplication process significantly contributes to health data integrity issues within EMR systems. Unique identification or accurate matching of patient records is also vital in ensuring the security of patient data, especially as these records are exchanged electronically [

6]. It is important to ensure that records are properly matched, because the impact of false positive matches and false negative non-matches could be medically dangerous. For example, a 2012 survey by the College of Healthcare Information Management Executives found that nearly 20% of hospital chief information officers reported their facilities had experienced at least one adverse medical event related to patient matching errors [

7].

Duplicated records are still a significant problem in Uganda’s EMR systems due to the absence of a national patient unique identifier. This has made it challenging to identify patients or match their data uniquely. To address this, patient matching uses variables containing partially identifying information, such as names, addresses, phone numbers, or dates of birth [

8]. Accurate and complete longitudinal patient profiles are essential for better healthcare delivery and data use. Deduplicating records also supports systems interoperability across HIV programs and facilities by enabling a unified view of each client.

Several patient identification and record linkage techniques are used to identify patients uniquely, including the traditional approaches, i.e., deterministic (heuristic), rule-based, and probabilistic matching methods [

9], and most recently, machine learning [

12,

13,

14,

39].

A study by Nagel et al. [

38] compared deterministic and probabilistic patient matching methods within two diagnostic imaging repositories in Ontario, Canada. The deterministic approach relied on exact matches of health numbers, while the probabilistic method used a scoring system based on various demographic fields. The study found that the probabilistic method identified more true matches but also required manual reviews for uncertain cases, whereas the deterministic method was simpler but less comprehensive.

Another study by Karr et al. [

39] evaluated various linkage software programs and algorithms using real-world data, including deterministic, probabilistic, and machine learning-based methods. The findings showed that machine learning algorithms, particularly those utilizing inexact matching techniques, achieved higher sensitivity and positive predictive value compared to traditional methods.

The above studies explored individual comparisons between deterministic and probabilistic methods or enhancements of probabilistic matching with machine learning. In this study, we assessed the level of duplication of PLHIV records in the UgandaEMR by creating two distinct variants of the probabilistic approach, i.e., threshold-based and weighted-average score-based, and compared their performance with a machine learning decision tree algorithm. Additionally, we identified a combination of variables that would be needed to identify unique PLHIV to validate the TX_CURR indicator (i.e., number of PLHIV currently on ART) in Uganda.

Methods

Deduplication Approaches

We used the threshold-based classification, weighted-average-score-based matching, and decision tree algorithms.

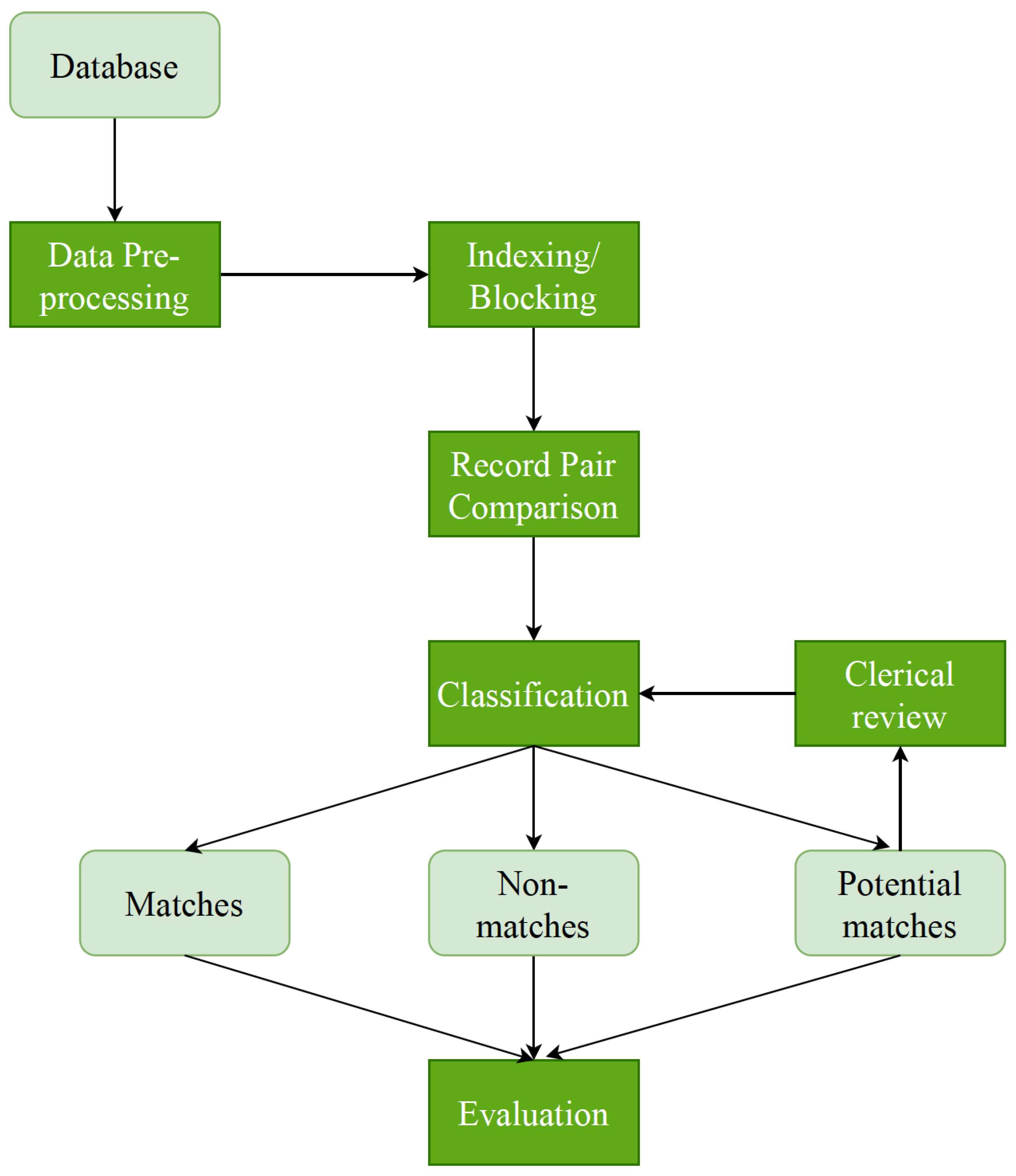

Process

The deduplication process was implemented through six stages, i.e., pre-processing, indexing, comparison, classification, and evaluation (

Figure 1). A Python framework was conducted using an open-source

Python Record Linkage Toolkit [

15]. This toolkit provides all the tools needed for record matching and deduplication.

Data Source

We abstracted demographic data of PLHIV active in care during June - November of 2022 from the UgandaEMR system - an electronic medical records platform used for registering and tracking HIV clients in Uganda - in 15 health facilities in the six districts that make up the Rwenzori region. Variables abstracted were: first name, middle name, last name, sex, age, date of birth, address, and phone number. Due to the absence of a ground truth-labeled dataset, we used a Febrl synthetic dataset, which contains 1,000 records (500 original and 500 duplicates with exactly one duplicate per original record), to further evaluate the performance of the trained algorithms [

16]. The Febrl synthetic dataset is widely used in record linkage studies and provides well-labeled data for testing de-duplication and entity resolution techniques.

Data Preprocessing

In this step, we cleaned out all the unwanted characters like commas, colons, periods, whitespaces, and brackets from all the strings and converted all the string variables to lowercase letters in order to eliminate errors that arise from inadvertent capitalization [

17]. To index words by their pronunciation, we applied phonetic encoding algorithms mainly in the indexing step, as described below, to ensure that similar records were grouped into the same block, even if they had some typographical variations [

18]. We used the Metaphone phonetic algorithm on both given and family names, as it performs better than other phonetic algorithms like Soundex on non-English names [

19].

Indexing

After cleaning and standardizing the data, we carried out

indexing to remove the obvious non-matches while maintaining the matching quality. Each record in the data set was compared with all other records to calculate similarities between two records [

8]. Full data set comparison resulted in a quadratic size of record pair comparisons, hence making the matching process slow and computationally expensive [

20]. Indexing generated candidate record pairs that were compared. We used the

blocking indexing approach, which has outperformed other techniques in a number of studies [

21,

22,

23].

Comparison

The candidate record pairs generated by the blocking algorithm were compared using similarity scores to determine their overall similarity. The similarity scores were calculated using the Jaro-Winkler [

24] and Levenshtein [

25] string comparators. Jaro-Winkler was used for string variables such as names and locations, whereas Levenshtein was applied to numeric-like fields such as phone numbers. These scores ranged from 0 (no match) to 1 (perfect match). See

Appendix A for formulas and additional details.

The variable comparisons produced similarity vectors, referred to as comparison vectors, which were used in the classification stage to decide whether a record pair was a match, a potential match, or a non-match.

Table 1 summarizes the methods used to compare the different variables with a 0.75 threshold equivalent to a similarity score of 1.0 for a distance

0.75 and a 0 otherwise. Different variables were compared using different comparison methods; Jaro-Winkler is suitable for string variables [

26] and Levenshtein for numerical variables [

27].

This threshold was selected through an iterative tuning process that tested multiple cutoffs. The value of 0.75 consistently yielded the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity when cross-validated against partially verified matches. It also performed well on the synthetic test dataset. Although 0.75 is slightly lower than thresholds used in some other linkage contexts, it was appropriate here. Data quality challenges, such as inconsistent spelling, name variations, and typographical errors, made higher thresholds prone to false negatives.

Classification

Classification was performed using threshold-based classification, weighted average score-based classification, and the supervised learning decision tree algorithm described below.

Threshold-based classification was used to classify pairs into three classes, i.e., matches, potential matches, and non-matches. In this method, similarity scores were summed up into a single total similarity value, known as

SimSum. Record pairs were then classified into lower and upper threshold values selected through an iterative string. A detailed description of the threshold selection process and classification formula has been added in

Appendix B.

Throughout the study, we distinguish between two levels of duplicates. Pair-level duplicates refer to record pairs classified as matches or potential matches. Records-level duplicates refer to the unique patient records involved in those matching pairs. This distinction is important because one record may appear in multiple matched pairs, but it is only counted once at the record level. We report both levels in the Results.

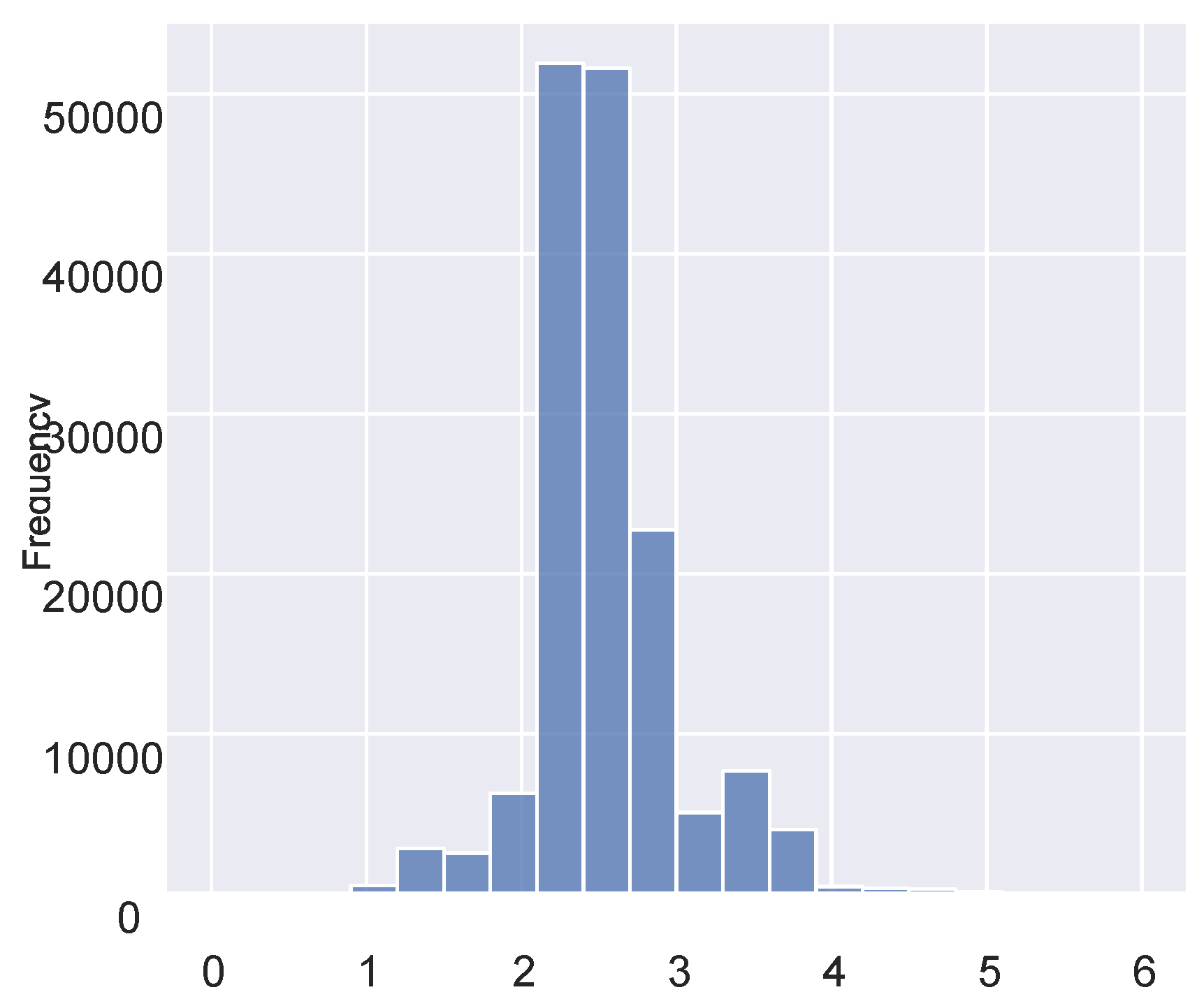

Figure 2.

A histogram of the summed similarity scores.

Figure 2.

A histogram of the summed similarity scores.

Weighted Average Score-Based Matching

After summing up the weighted similarity scores and classifying pair records into matches, potential matches, and non-matches, each variable was assigned a weight based on its discriminative power, where weights quantify each variable’s contribution to the probability of accurately classifying the records. The weighted sum was calculated by multiplying the variable’s similarity score by an assigned weight prior to the summation. The summation output was divided by the sum of the weights to obtain the final score used in classification; see Equation 4.

We assigned a weight of 2 to the surname, given name, and phone contact variables, and a weight of 1 to the date of birth, village, and sub-county variables. These weights were based on our domain knowledge and prior experience with HIV programmatic data. Variables with greater potential to uniquely identify a patient were assigned higher weights. The final weights were refined through iterative testing to improve match quality using partially verified data. While this approach performed well in our context, we acknowledge that weight configurations are not universal and may require recalibration in other settings.

Patient matching was performed after summing up the weight similarities and computing the weight average scores. Pairs with a score greater than or equal to 0.7 were classified as matches; pairs with scores between 0.5 and 0.7 were classified as potential matches, and pairs with scores less than 0.5 were classified as non-matches.

Supervised Learning

We explored the use of supervised machine learning techniques for de-duplication, focusing on the decision tree algorithm. The algorithm was trained on a dataset labeled using the two rule-based methods, with partial manual validation from facility-level data officers during routine data cleaning and quality assurance. While this does not constitute a fully human-verified gold-standard dataset, it provided a semi-supervised basis to test feasibility under real-world constraints.

The dataset was highly imbalanced, with non-matches significantly outnumbering matches. To address this challenge, we applied two commonly used strategies for handling imbalanced datasets: Undersampling and Oversampling [

31] and cost-sensitive methods [

32].

To refine the decision tree, we performed hyperparameter tuning using a grid search to identify the optimal combination of parameters. The parameters evaluated included the splitting criterion (Gini or entropy), the splitting strategy (best or random), maximum tree depth, minimum number of samples required to split an internal node, and minimum number of samples required to be a leaf node. The optimal parameters identified were Gini as the splitting criterion, a “best” splitter, no limit on the tree depth, a minimum of two samples to split a node, and one sample for a leaf node. Additionally, we applied ten-fold cross-validation to ensure robust model validation. However, even with these optimizations, the decision tree algorithm struggled to achieve satisfactory performance in predicting duplicate records, reflecting the inherent difficulty of handling imbalanced datasets in record de-duplication tasks.

Ethical Approval

This activity was reviewed by the U.S. CDC and was determined to be research not involving human subjects and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy, under 45 C.F.R. part 46; 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d), 5 U.S.C. §552a, 44 U.S.C. §3501. It was also reviewed and approved by the Makerere University School of Public Health, Research and Ethics Committee.

Results

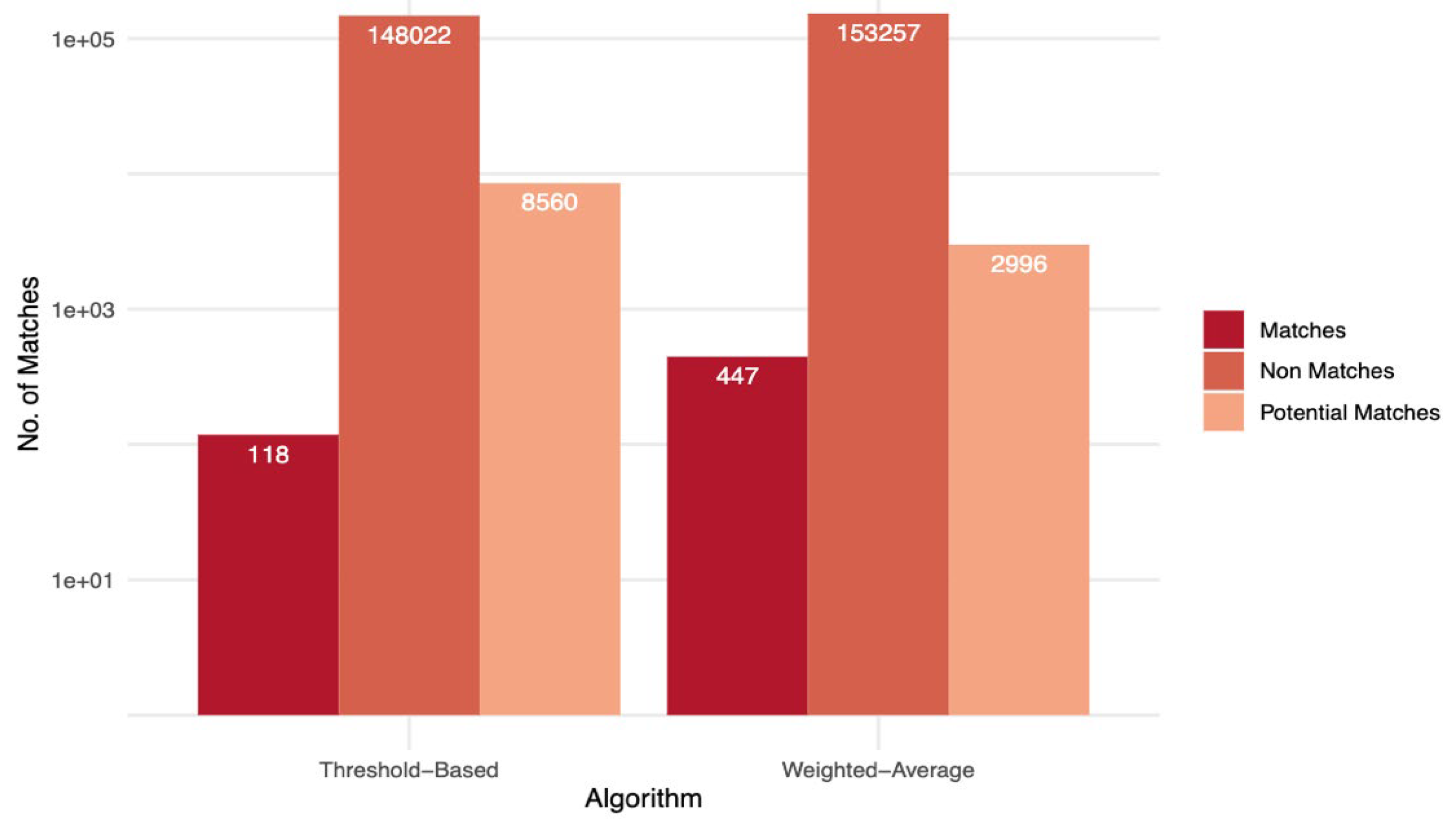

Figure 3 summarizes the matching results achieved by the different algorithms. The classification was performed on 156,700 reference candidate pairs, which were derived from an initial 1,999,610,089 possible record pairs. These pairwise combinations were generated from the original dataset of 44,717 records using all-to-all comparisons. Blocking indexing techniques were used to reduce the number of comparisons by splitting the dataset into smaller blocks based on combinations of metaphone transformations of given names, family names, and sub-county information. This approach eliminated the majority of clearly non-matching pairs, significantly reducing the computational burden while preserving pairs likely to match. The resulting 156,700 candidate pairs were subjected to detailed comparison and classification. Decision tree results are not shown on the graph because the ground truth data set that was used to train and validate the decision tree algorithm was crafted from the matches and the non-matches of the weighted average algorithm.

The overall best-performing algorithm was the weighted average score-based algorithm, as it achieved a higher number of matches with fewer false positives and false negatives compared to the threshold-based algorithm. Specifically, at the pair level, the weighted average algorithm obtained 447 (0.3%) matches, 2,996 (1.9%) potential matches, and 153,257 (97.8%) non-matches. In contrast, the threshold-based algorithm achieved 118 (0.1%) matches, 8,560 (5.5%) potential matches, and the remaining 148,022 (94.5%) as non-matches. A subset of matched and potential match pairs identified by both algorithms was reviewed by the facility data officers during the routine data quality reviews to assign ground truth labels.

At the record level, out of 44,717 patient records, the threshold-based algorithm identified 223 (0.5%) of the records as duplicates, while the weighted average algorithm identified 2,459 (5.8%) as duplicates. These counts represent unique patient records involved in matched or potentially matched pairs, accounting for instances where a single record appeared in multiple duplicate pairs.

To further evaluate the performance of the algorithms beyond the primary dataset, we tested them on a synthetic gold standard reference dataset. This test dataset comprised 200 true matches (duplicates) and 320 true non-matches (non-duplicates). The evaluation was conducted using several key metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, and F-score - results are summarized in

Table 2. Among the algorithms, the weighted-average model demonstrated superior performance with the highest sensitivity (99.0%), specificity (98.8%), and F-score (98.9%). These results show the robustness and accuracy of the weighted-average model in identifying duplicates, outperforming the threshold-based and decision tree algorithms.

When we examined records flagged as duplicates by all three algorithms, we observed that many had minor variations in their names. For example, one record might list the name as “Semaganda,” while another might spell it “Ssemaganda.” There were also some instances where records for the same client differed in the number of names provided, with one record listing two names and another listing three. In some cases, two or more records classified as duplicates belonged to the same individual receiving treatment at different facilities, indicating potential cross-facility care.

We also observed that duplicates were more readily identifiable among clients with NINs recorded, suggesting that NINs can improve the accuracy of patient matching.

Discussion

This study represents one of the initial efforts to systematically identify duplicate records of PLHIV in Uganda by utilizing demographic variables through score-based and supervised machine learning techniques. We explored three matching algorithms trained to identify duplicates or potential HIV client duplicates at fifteen health facilities from six districts of the Rwenzori region. The focus on the Rwenzori region allowed for a controlled and detailed exploration of de-duplication algorithms using high-quality data. Although this regional focus may limit the generalizability of the findings, it provides a foundation for scaling this approach to other regions and eventually the entire country. Future studies should aim to extend this methodology to all regions of Uganda to better understand duplication patterns and rates nationally, as well as across diverse healthcare settings.

This study revealed that approximately 5.8% of client records were duplicates as identified by the weighted-average algorithm. While this percentage may appear modest, it translates to significant inaccuracies when scaled to the national cohort of 1.4 million PLHIV currently receiving antiretroviral treatment. Duplication in Uganda is compounded by the lack of a national unique patient identifier, a challenge that is similarly faced by other high HIV-burden countries such as Kenya [

40] and Nigeria [

41]. Although limited comparable studies exist, duplication rates in similar settings without unique identifiers have been reported to range between 4% and 10%, depending on the context and method used [

40].

When choosing the best de-duplication algorithm, it is important to consider the cost associated with false positive and false negative matches. In health data systems, the cost of high false positive error rates is particularly significant, as it could lead to merging records of two or more patients who are not the same person. Such errors could undermine the integrity of client records, potentially compromising continuity of care, clinical decision-making, and the delivery of accurate and timely healthcare services. This highlights the importance of algorithms that minimize false positives, even if they come at the cost of slightly higher computational requirements. Our findings are consistent with prior studies [

38,

39] that probabilistic and machine learning methods can achieve strong performance in patient matching. While we did not include deterministic methods in our comparison, the weighted average methods demonstrated superior performance among the approaches evaluated, with fewer false positives and reduced manual review effort.

The weighted-average algorithm, integrating multiple criteria and assigning differing levels of weights to various variables, has proven to be more effective, resulting in a greater number of true positives and a reduction in both false negatives and positives. This demonstrates the method’s strength in handling the complexities of patient data and its increased dependability in identifying duplicates. The improved sensitivity and specificity rates further emphasize the algorithm’s ability to accurately identify true matches, while the enhanced F-score indicates its balanced precision and recall—essential aspects for the effective implementation of de-duplication processes.

However, although the weighted-average algorithm was statistically superior, its implementation might result in increased computational complexity and, potentially, higher resource consumption during the de-duplication process. Training this algorithm required nearly two hours, compared to the 20 minutes and 10 minutes needed for the threshold-based and decision-tree techniques, respectively. This indicates that significant time and computational resources might be necessary to apply this algorithm to the entire cohort of 1.4 million PLHIV currently undergoing treatment. Therefore, the decision to use this algorithm should be carefully weighed against the available resources and the specific requirements of the healthcare provider.

Future considerations for refining de-duplication algorithms should focus on enhancing computational efficiency and further reducing the need for manual verification. The implementation of machine learning and artificial intelligence could play a significant role in achieving these objectives. These technologies could provide dynamic learning capabilities, adaptively improving the algorithms’ accuracy and efficiency as more data is being considered.

Limitations

This study had three main limitations. The low level of completeness of most variables within the UgandaEMR. This incompleteness poses a challenge when utilizing patient matching algorithms, as it greatly impacts the accuracy and reliability of the matching process. The lack of completeness in important variables such as phone numbers, date of birth, addresses, and NIN makes it increasingly difficult to accurately identify and de-duplicate patients. Incomplete data introduces uncertainty and ambiguity into the matching algorithm, making it harder to distinguish between different individuals who may share similar or identical partial details [

36]. Consequently, there is a risk of false matches, where distinct patients are mistakenly identified as duplicates, or of missed potential matches, where actual duplicates go unrecognized. In both scenarios, the efficacy of the algorithm is undermined, potentially leading to unreliable matching results. Therefore, it is recommended that the UgandaEMR development team works closely with various implementing partners and health facilities to ensure a comprehensive and accurate capture of demographic variables within the system.

The analysis was limited to the Rwenzori region, comprising six districts and 15 health facilities, primarily due to the availability of high-quality data and resource constraints that would not allow a national-level study. While this focus limits the generalizability of the findings, it allowed for a controlled and detailed exploration of de-duplication algorithms. The Rwenzori Region provided an appropriate testing ground for the methodology, but different regions may face unique challenges that influence duplication rates, such as variations in data quality and healthcare access. Future studies should aim to extend this methodology to the entire country to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the duplication problem at a national scale. Expanding the scope would not only improve generalizability but also allow for a comparison of duplication rates and patterns across different regions, providing valuable insights for targeted interventions.

It should also be noted that these algorithms are not capable of identifying duplicate clients who have entirely distinct records. For instance, if Client A and Client B are actually the same individuals, but their records show completely different names, addresses, and phone numbers, the algorithms will be unable to recognize them as duplicates.

Recommendations

To continue improving the integrity and efficiency of the patient deduplication process in Uganda’s EMR systems, several measures are recommended. First, efforts should be increased to capture NINs consistently across all health facilities. Our findings indicate that duplicates were more readily identifiable among clients who had their NINs recorded. Therefore, improving the capture and accuracy of NINs can significantly aid in the unique identification of clients, simplifying the deduplication process.

Secondly, the implementation of robust data validation checks within the UgandaEMR is important. Specifically, validation checks for key fields such as phone numbers, sex, NIN, and ART numbers need to be stringent to ensure correct data entry. Enhancing these checks will help in preventing errors at the point of data entry, which is vital for reducing the occurrence of duplicate records and ensuring that no individuals share the same identifiers erroneously.

Lastly, we recommend integrating a weighted average algorithm into the routine operations of EMRs at the facility level. Most duplicates identified in this study were within the same facilities, suggesting that an algorithmic approach could effectively reduce duplication by systematically evaluating the consistency of client data entries. This method would allow healthcare providers to identify and resolve duplicates more efficiently, thereby enhancing the overall quality of patient data management and care coordination.

Conclusions

In conclusion, as Uganda continues its search for an optimal national patient unique identifier, the findings from this study offer a viable interim solution for patient record de-duplication. The shift from paper-based to electronic medical records across health facilities has required the development of more sophisticated patient matching and de-duplication algorithms. Our comprehensive evaluation has determined that the weighted average score-based matching algorithm outperforms traditional methods, successfully identifying a significant portion of records as duplicates or potential duplicates. This study also shows the impact of data completeness on the performance of matching algorithms and underscores the necessity for the UgandaEMR development team to collaborate with partners to improve data entry practices. While effective in the short term, such algorithmic approaches remain a workaround in the absence of a nationally implemented and consistently integrated unique identifier. Continued investment in a UID system will be critical to achieving sustained improvements in patient-level data accuracy. Therefore, our study reaffirms the promising capabilities of machine learning techniques in refining patient matching processes, with the potential for further improvements by increasing the size of the training dataset. This strategy, therefore, stands as a robust approach for addressing current EMR challenges in Uganda until a more permanent identification system is established.

Funding

This project has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under the terms of the 6NU2GGH0022280-04-00.

Data Availability

Due to Ugandan data privacy laws and ethical guidelines related to patient-level data, the data used in this study cannot be made available to other researchers or the publishing journal.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to all the reviewers for their insightful feedback and constructive comments, which greatly contributed to the success of this article

Potential Conflict of Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Full Term |

| EMR |

Electronic Medical Records |

| PLHIV |

People Living with HIV |

| ART |

Antiretroviral Therapy |

| NIN |

National Identification Number |

| NIRA |

National Identification and Registration Authority |

| CDC |

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| UID |

Unique Identifier |

| MPI |

Master Patient Index |

| PEPFAR |

President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief |

| TX_CURR |

Number of PLHIV currently on ART (Indicator in PEPFAR Monitoring) |

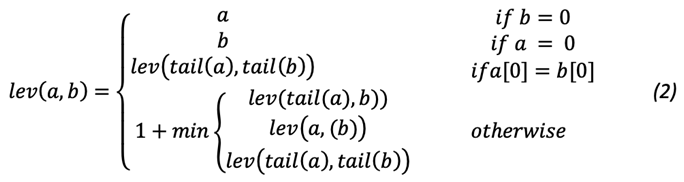

Appendix A: String Similarity Metrics

Jaro-Winkler is a string comparison metric that measures the similarity between two strings. The higher the Jaro–Winkler distance for two strings is, the more similar the strings are. It counts the number of characters that are common in two strings within a certain window of characters, similar to the positional q-gram-based comparison approach. Jaro-Winkler scores range from 0 (a non-matching record) to 1 (a perfect matching record).

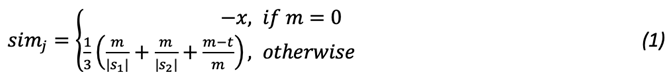

The Jaro similarity of two given strings and is calculated by;

Where; is the length of the string , is the number of matching characters, and is the number of transpositions.

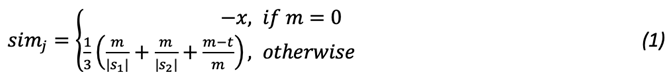

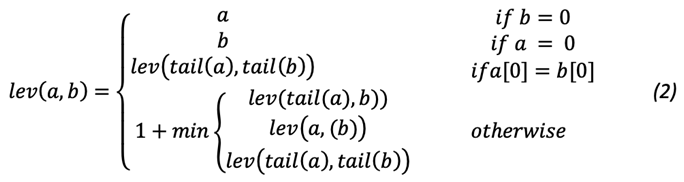

Levenshtein is a measure of the similarity between two strings, which we are referred to as the source string () and the target string (). The distance score is the number of deletions, insertions, or substitutions required to transform into . Levenshtein similarity scores are normalised numerical values, with a similarity of 1.0 corresponding to an exact match between two variables and 0.0 corresponding to a total dissimilarity between two variables.

The Levenshtein distance score between two strings (of length and is given by

where the of some string is a string of all but the first character of , and is the character of the string , counting from 0.

Appendix B: Threshold-Based Classification Details

We used the SimSum score to classify client record pairs into three categories based on two classification thresholds,

(lower) and

(upper) are set, and a record pair

is classified according to Equation 3, as shown below.

The selection of these thresholds is an iterative process until satisfactory matching results are obtained. Increasing the upper threshold and lowering the lower threshold will result in fewer false matches and non-matches but lead to more potential matches that must be inspected and classified manually. On the other hand, lowering and increasing results in a smaller number of potential matches but likely also in an increase.

In this study, we compared seven variables for each record pair, resulting in a maximum possible SimSum score of 7.0. Based on histogram analysis (see

Figure 2), we set classification thresholds as follows: record pairs with a SimSum score of 6.5 or higher were classified as matches, those with scores between 4.5 and 6.5 were classified as potential matches, and those with scores below 4.5 were classified as non-matches.

References

- Just BH, Marc D, Munns M, Sandefer R. Why patient matching is a challenge: research on master patient index (MPI) data discrepancies in key identifying fields. Perspect Heal Inf Manag American Health Information Management Association; 2016;13(Spring). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27134610/.

- Monitor. 2.4 million Ugandans don’t have national IDs. Dly Monit 2020;8. Available from: https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/2-4-million-ugandans-don-t-have-national-ids-1805512.

- U. Uludag, S. Pankanti, S. Prabhakar and A. K. Jain, “Biometric cryptosystems: issues and challenges,” in Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 92, no. 6, pp. 948-960, June 2004. [CrossRef]

- Maltoni, Davide, Dario Maio, Anil K. Jain, and Jianjiang Feng. “Fingerprint matching.” In Handbook of Fingerprint Recognition, pp. 217-297. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bohensky MA, Jolley D, Sundararajan V, Evans S, Pilcher D V, Scott I, Brand CA. Data linkage: a powerful research tool with potential problems. BMC Health Serv Res BioMed Central; 2010;10(1):1–7. [CrossRef]

- Riplinger, Lauren, Jordi Piera-Jiménez, and Julie Pursley Dooling. “Patient identification techniques–approaches, implications, and findings.” Yearbook of medical informatics 29, no. 01 (2020): 081-086. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27134610/.

- College of Healthcare Information Management Executives. “Summary of CHIME Survey on Patient Data-Matching.” May 16, 2012. http://chimecentral.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Summary_of_CHIME_Survey_on_Patient_Data.pdf.

- Christen, Peter. “The data matching process.” In Data matching: concepts and techniques for record linkage, entity resolution, and duplicate detection, pp. 23-35. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Waruhari, Philomena, Ankica Babic, Lawrence Nderu, and Martin C. Were. “A review of current patient matching techniques.” Informatics Empowers Healthcare Transformation (2017): 205-208. [CrossRef]

- Lajmanovich A, Yorke JA. A deterministic model for gonorrhea in a nonhomogeneous population. Math Biosci Elsevier; 1976;28(3–4):221–236. [CrossRef]

- Fellegi IP, Sunter AB. A theory for record linkage. J Am Stat Assoc Taylor & Francis; 1969;64(328):1183–1210. [CrossRef]

- Koudas N, Sarawagi S, Srivastava D. Record linkage: similarity measures and algorithms. Proc 2006 ACM SIGMOD Int Conf Manag Data 2006. p. 802–803. [CrossRef]

- Michelson M, Knoblock CA. Learning blocking schemes for record linkage. AAAI 2006. p. 440–445.

- Wilson DR. Beyond probabilistic record linkage: Using neural networks and complex features to improve genealogical record linkage. 2011 Int Jt Conf neural networks IEEE; 2011. p. 9–14. [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, Jonathan. “Python Record Linkage Toolkit: A toolkit for record linkage and duplicate detection in Python.” (2019). [CrossRef]

- Christen P, Churches T, Hegland M. Febrl–a parallel open-source data linkage system. Adv Knowl Discov Data Min 8th Pacific-Asia Conf PAKDD 2004, Sydney, Aust May 26-28, 2004 Proc 8 Springer; 2004. p. 638–647. [CrossRef]

- Demelius L, Kreiner K, Hayn D, Nitzlnader M, Schreier G. Encoding of Numerical Data for Privacy-Preserving Record Linkage. dHealth 2020. p. 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Grannis SJ, Overhage JM, McDonald C. Real world performance of approximate string comparators for use in patient matching. MEDINFO 2004 IOS Press; 2004. p. 43–47. [CrossRef]

- Snae C. A comparison and analysis of name matching algorithms. Int J Comput Inf Eng Citeseer; 2007;1(1):107–112.

- Goel A, Prasad R. Efficient indexing techniques for record matching and deduplication. Int J Comput Vis Robot Inderscience Publishers Ltd.; 2014;4(1–2):75–85. [CrossRef]

- O’Hare K, Jurek-Loughrey A, Campos C de. A review of unsupervised and semi-supervised blocking methods for record linkage. Link Min Heterog Multi-view Data Springer; 2019;79–105. [CrossRef]

- Fan W, Jia X, Li J, Ma S. Reasoning about record matching rules. Proc VLDB Endow VLDB Endowment; 2009;2(1):407–418. http://www.vldb.org/pvldb/2/vldb09-654.pdf.

- Dou C, Sun D, Chen Y-C, Li G, Liu J. Probabilistic parallelisation of blocking non-matched records for big data. 2016 IEEE Int Conf Big Data (Big Data) IEEE; 2016. p. 3465–3473. [CrossRef]

- Dreßler, Kevin, and Axel-Cyrille Ngonga Ngomo. “On the efficient execution of bounded Jaro-Winkler distances.” Semantic Web 8, no. 2 (2016): 185-196. [CrossRef]

- Yujian L, Bo L. A normalized Levenshtein distance metric. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell IEEE; 2007;29(6):1091–1095. [CrossRef]

- Cohen WW, Ravikumar P, Fienberg SE. A Comparison of String Distance Metrics for Name-Matching Tasks. IIWeb 2003. p. 73–78.

- Runkler TA, Bezdek JC. Automatic keyword extraction with relational clustering and Levenshtein distances. Ninth IEEE Int Conf Fuzzy Syst FUZZ-IEEE 2000 (Cat No 00CH37063) IEEE; 2000. p. 636–640. [CrossRef]

- Sarawagi S, Bhamidipaty A. Interactive deduplication using active learning. Proc eighth ACM SIGKDD Int Conf Knowl Discov data Min 2002. p. 269–278. [CrossRef]

- Winkler WE. Matching and record linkage. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat Wiley Online Library; 2014;6(5):313–325. [CrossRef]

- Laender AHF, Da Silva AS, Goncalves MA, De Carvalho MG. Learning to deduplicate. Proc 6th ACM/IEEE-CS Jt Conf Digit Libr IEEE; 2006. p. 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Hoens TR, Chawla N V. Imbalanced datasets: from sampling to classifiers. Imbalanced Learn Found algorithms, Appl Wiley Online Library; 2013;43–59. [CrossRef]

- Thai-Nghe N, Gantner Z, Schmidt-Thieme L. Cost-sensitive learning methods for imbalanced data. 2010 Int Jt Conf neural networks IEEE; 2010. p. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Kamel MS, Wong AKC, Wang Y. Cost-sensitive boosting for classification of imbalanced data. Pattern Recognit Elsevier; 2007;40(12):3358–3378. [CrossRef]

- Grannis SJ, Williams JL, Kasthuri S, Murray M, Xu H. Evaluation of real-world referential and probabilistic patient matching to advance patient identification strategy. J Am Med Informatics Assoc Oxford University Press; 2022;29(8):1409–1415.

- Brodersen KH, Ong CS, Stephan KE, Buhmann JM. The balanced accuracy and its posterior distribution. 2010 20th Int Conf Pattern Recognit IEEE; 2010. p. 3121–3124. [CrossRef]

- Duggal R, Khatri SK, Shukla B. Improving patient matching: single patient view for Clinical Decision Support using Big Data analytics. 2015 4th Int Conf Reliab Infocom Technol Optim (ICRITO)(Trends Futur Dir IEEE; 2015. p. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Data.FI. (2021). Guidance for deduplicating client-level data. Washington, DC, USA: Data.FI, Palladium. Retrieved from: https://datafi.thepalladiumgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Data.FI_Guidance-for-Deduplicating-ClientLevel-Data_Solutions_Brief_SB-20-01.pdf.

- Nagels, J., Wu, S. & Gorokhova, V. Deterministic vs. Probabilistic: Best Practices for Patient Matching Based on a Comparison of Two Implementations. J Digit Imaging 32, 919–924 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Karr AF, Taylor MT, West SL, Setoguchi S, Kou TD, Gerhard T, et al. (2019) Comparing record linkage software programs and algorithms using real-world data. PLoS ONE 14(9): e0221459. [CrossRef]

- Omoro, G., Awuor, M., & Omamo, A. (2018). National Unique Patient Identifier in HIV/AIDS Healthcare in Kenya. National Unique Patient Identifier in HIV/AIDS Healthcare in Kenya, 15(1), 3-3. https://ijrp.org/paper-detail/397.

- Chukwu, E., Ekong, I., & Garg, L. (2022). Scaling up a decentralized offline patient ID generation and matching algorithm to accelerate universal health coverage: Insights from a literature review and health facility survey in Nigeria. Frontiers in Digital Health, 4, 985337. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).