1. Introduction

1.1. The Invasion and Impacts of Mikania micrantha

Mikania micrantha is a perennial climbing herb native to Central and South America. It is known for its extremely strong reproductive capacity, making it one of the world’s 100 worst invasive alien species according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Its optimal growth environment is characterized by high temperature, high humidity, and abundant sunlight, which are all present in Taiwan, allowing it to spread rapidly in the country through seed and vegetative propagation. Studies have shown that M. micrantha grows at its fastest rate when soil moisture is more than 15% and the temperature is between 25°C to 30°C, allowing it to complete its flowering-to-fruiting process in just 15 days (Yang, Q. et al., 2003) [

27].

M. micrantha poses a serious threat to Taiwan’s ecosystems and agricultural production because it can quickly cover surrounding vegetation, block photosynthesis, and cause native plants to gradually die. Consequently, its high consumption of soil water and nutrients exacerbates environmental degradation. From an agricultural perspective, its climbing nature disrupts light and ventilation needed for fruit trees and crops, reducing yield and quality, ultimately resulting in economic losses (Wei, T. Y., 2003) [

24]. At present, it grows mainly in low-altitude plantations and abandoned orchards and farmland, imposing long-term pressure on both ecosystems and agriculture.

1.2. Existing Control Methods and Limitations

Currently, M. micrantha is mainly controlled using mechanical, chemical, and biological methods. Mechanical control involves manual removal or mechanical cutting, which requires high labor input, has low efficiency, can only temporarily reduce vine coverage, and cannot completely eradicate the weed. Chemical control, through herbicides, achieves immediate effects in the short term but may cause secondary pollution to soil and the environment and could disrupt ecological balance in the long term. Lastly, biological control using natural enemies is at the experimental stage, with uncertain effectiveness and the need for long-term monitoring (Huang, S. Y. et al., 2004) [

13].

These existing methods face limitations such as high cost, insufficient efficiency, or significant environmental impacts, highlighting the urgent need to develop a control strategy that ensures both long-term stability and environmental sustainability.

1.3. Opportunities for Smart Agriculture and IoT Applications

Through smart agriculture, Internet of Things (IoT) technologies have been increasingly applied to agricultural production, including environmental monitoring, smart irrigation, pest and disease forecasting, and automated control. IoT systems, using a data-driven closed-loop control model, collect real-time data through sensors, transmit it to the cloud for analysis, and subsequently trigger automated equipment to execute corresponding actions.

In terms of controlling M. micrantha control, IoT technologies provide: (1) precision control by integrating real-time environmental monitoring and algorithm-based decision-making and activating spraying devices at optimal times, reducing herbicide usage; (2) continuous monitoring by collecting long-term data, which enables the tracking of M. micrantha growth dynamics for early prevention of large-scale invasions; and (3) reduced labor burden by using remote controlled and automated spraying reducing the need for frequent manual fieldwork and lowering labor costs.

Based on these premises, this study designed and developed an IoT-integrated smart weed control system, and tested it in actual farm conditions to verify its stability, weed control efficiency, and impact on farmers’ labor costs. Our goal is to propose an innovative solution that balances environmental sustainability with agricultural productivity.

1.4. Research Objectives

The primary objective of this study is to design and develop a smart weed control system integrated with Internet of Things (IoT) technologies. Through this, we expect to provide an effective, environmentally friendly, and sustainable solution to the rapid spread of M. micrantha in Taiwan. This study will contribute greatly to the following:

System design and innovation: the Design Science Research (DSR) methodology was employed for the research process, from problem identification, system design, prototype construction, and field testing to optimization and dissemination; thus, both theoretical rigor and practical feasibility are ensured.

Quantification of control effectiveness: a Control Efficiency Index (CEI) measured the effectiveness of the system across different periods and test plots, thereby enhancing the scientific validity and comparability of the results.

User acceptance analysis: the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) assessed the farmers’ perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEOU), behavioral intention (BI), and attitude toward use (ATU), ensuring that the system meets practical user needs and providing evidence for its potential for broader adoption.

Economic feasibility evaluation: the Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) provided an economic basis for decision-making for the implementation of the proposed technology.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ecological Characteristics and Impacts of Mikania micrantha

Mikania micrantha is a perennial climbing herb belonging to the family Asteraceae. Its stems are slender and highly branched, and its leaves are opposite, triangular-ovate to ovate in shape, have a cordate or sagittate base, an acuminate apex, serrated margins, and glabrous surfaces. The inflorescences are capitula that are often arranged in corymbiform panicles, and the flowers are white, tubular, and fragrant. The fruit is an achene with five ridges, black in color, and topped with white pappus hairs that facilitate easy wind dispersal due to being lightweight. Moreover, it reproduces both sexually and asexually with each stem node, and even internodes, generating adventitious roots and new shoots. The presence of enations—semi-transparent, lacerated structures at the internodes—serves as a key morphological feature distinguishing M. micrantha from native congeners in Taiwan (Chen, C. Z. 2001) [

6].

This species can grow extremely rapidly and can sprawl or climb over surrounding vegetation; thus, it was nicknamed “mile-a-minute weed.” Its flowering and fruiting season extends from October to January, and blooms mainly between November and December. Seed production can reach up to 170,000 seeds per square meter, which are easily dispersed over long distances by wind through the pappus structure (Yang, Q. et al., 2003) [

27]. Due to its strong phototropism and capacity for vegetative propagation, M. micrantha quickly blankets, twines, and suppresses host plants, limiting photosynthesis and leading to their gradual decline and death.

Indigenous to Central and South America and the Caribbean, M. micrantha thrives in hot, humid, and bright environments. It grows optimally at 25°C to 30°C and with a soil moisture of above 15%, which are typical of tropical species (Huang, Z. L. et al., 2000; Yang, Q. et al., 2003) [

14,

27]. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed M. micrantha among the world’s 100 worst invasive alien species, and it is widely known in Asia as the “plant killer,” “green cancer,” and “green golden apple snail,” underscoring its ecological threat. In Taiwan, its earliest herbarium record was in 1986 in Wanluan, Pingtung, and the species has since expanded rapidly northward. Following the six invasion stages described by Cronk and Fuller (1995) [

10]—introduction, naturalization, adaptation, expansion, interaction, and stabilization—M. micrantha has advanced through each stage and continues to spread.

Currently, the species is commonly found in disturbed lowland habitats, including plantations, secondary forests, protection forests, abandoned orchards, fallow lands, roadsides, and slopes. Studies indicate that areas with low elevation, high temperature, high humidity, and strong sunlight are at risk for invasion. In Taiwan, M. micrantha grows most frequently in anthropogenically disturbed areas with slopes of 10° to 40° (Wei T. Y., 2003) [

24]. The weed is highly shade-intolerant and perishes under low-light conditions, but flourishes under high irradiance. Field studies further confirm that moist conditions increase invasion severity (Willis, M. et al., 2008) [

25]. Consequently, neglected and poorly maintained lands, particularly those previously disturbed, are susceptible to colonization and dominance by this weed.

Taiwan’s Bureau of Animal and Plant Health Inspection and Quarantine (2002) stated that M. micrantha has invaded agricultural lands across 17 counties and 130 townships, affecting a total area of 13,206 hectares. In 2001, infestations were concentrated in low-altitude foothills up to 1,400 m, but by 2003, the species had expanded into mid-elevation mountain zones. Observations done in 2018 showed that up to 4,948 hectares of public and private forests, national forests, and indigenous reserves have been invaded. Over the past three decades, M. micrantha has spread widely throughout Taiwan’s lowland and mid-elevation regions, with only the central high mountains largely unaffected.

In summary, M. micrantha reproduces and grows at a rapid pace and exhibits strong phototropism, enabling it to spread throughout lowland and foothill ecosystems in Taiwan. It threatens farmland, orchards, plantations, and protected forests, resulting in significant ecological disruption and socioeconomic losses. These impacts highlight the urgent necessity for systematic monitoring and effective management strategies (Huang, S. Y., 2004) [

13].

2.2. Research on Related Control Strategies and Their Findings

Recent international research on the control of M. micrantha can be broadly categorized into three strategies:

(1) Ecological competition strategies: Using replacement vegetation to suppress the growth of M. micrantha, such as planting leguminous crops (e.g., Desmodium) to occupy ecological niches and reduce regrowth through competition for light and nutrients (Jia, P. et al., 2022) [

15].

(2) Biological control strategies: Introducing specific pathogens, such as the rust fungus Puccinia spegazzinii and Alternaria gossypina, together with climate distribution models to predict suitable areas for improving the temporal and spatial precision of release (Qin, H. et al., 2025; Zhang, J. et al., 2023) [

22,

29].

(3) Chemical and physiological strategies: Employing environmentally-friendly chemical and molecular regulation methods, including exogenous phytohormones and RNAi-based herbicides, aimed at reducing the capacity to reproduce or inhibiting specific gene expression (Zhang, Q. et al., 2021; Chen, Y. et al., 2021) [

7,

30].

Previous studies focused mainly on the following detection technologies:

Hyperspectral and remote sensing identification: plant identification was done using spectral features between 450nm to 998nm with machine learning classifiers (Huang, J. et al., 2021; Zhou, L. et al., 2022) [

11,

32].

Low-cost sensing modules: sensors, such as the spectral triad sensors, were developed and paired with real-time classification algorithms that can be mounted on agricultural machinery for in-field detection (Lee, C. et al., 2022) [

16].

UAV and deep learning applications: unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) imagery with convolutional neural networks (CNN) or clustering algorithms was established to build distribution maps and classify invasion severity (Chen, Y. et al., 2020; Wang, X. et al., 2020) [

8,

23].

Although these studies provide diverse technological approaches, several common limitations remain. First, most research lacked system integration and focused mainly on a single aspect (detection or control); thus, they failed to establish a complete “detection–decision–execution” loop. Further, earlier studies performed their experiments primarily in greenhouses or small plots. This made the results difficult to apply to large-scale farmlands because of the limited scope of field validation. Finally, only a few studies evaluated user acceptance and economics, and failed to conduct farmers’ acceptance and cost-benefit analysis, which makes practical adoption and large-scale deployment questionable.

The present study bridges these gaps and contributes to the advancement of agricultural technologies by using a closed-loop system design, performing long-term field trials, and conducting a multi-dimensional evaluation.

Our paper integrated an IoT-based environmental monitoring with remote control and precision spraying modules to form a complete sensing–decision–execution cycle. Moreover, the experiment was conducted for over 6 months in commercial orchards, which demonstrated an 87% reduction in weed coverage with decreased manual weeding frequency to once per season, confirming our system’s stability and effectiveness. Lastly, we employed the Control Efficiency Index (CEI) to quantify weed suppression performance, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to assess user acceptance, and the Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) to evaluate economic feasibility; all these address the evaluation gaps in existing literature.

Nevertheless, this study also has limitations, such as being restricted to a single site and crop. Due to this, further verification across multiple crops and regions is required to assess generalizability and large-scale applicability. Moreover, it is suggested to integrate UAV imagery and AI-based models to monitor large areas. Biological control strategies can also be used in conjunction with our system to develop a multi-layered approach, enhancing the overall efficiency of managing invasive species.

2.3. IoT Applications in Smart Agriculture

The application of the Internet of Things (IoT) in smart agriculture has progressed from basic environmental monitoring and wireless sensor networks (WSN) to more sophisticated integrations with artificial intelligence (AI), edge computing, and digital twins (DT). These advancements have strengthened farm management through the use of data and promoted sustainability and precision agriculture. Some of the cases from key literature are presented below:

(1) Environmental monitoring and pest/disease prediction

IoT systems with temperature, humidity, soil moisture, and air sensors have been developed to continuously collect data for predicting pest outbreaks and crop growth status. These make early detection and decision support possible, leading to a more precise farm management, decreased disease incidence, and efficient use of resources (Rajak, P. et al., 2023) [

19].

(2) Smart greenhouse control

IoT and WSN platforms, combined with fuzzy logic controllers, have been applied to regulate light, water, and temperature in controlled environments, which optimize resource utilization. For instance, Benyezza et al. (2023) established a platform for greenhouses to significantly reduce water waste and labor costs [

1].

(3) Proximal sensing and decision support in vineyards

Proximal sensors and AI-based models have been employed in vineyards to collect soil and microclimate data through LoRa/IoT communication protocols. These data are integrated with predictive models to optimize irrigation, disease management, and fruit quality, aiding farmers’ decision-making (Araújo, S.O. et al., 2020) [

1].

(4) Integration of digital twins and IoT

DT technology in agriculture, such as combined IoT sensors, simulation, and real-time feedback control, is currently being explored for better crop management, pest detection, and resource optimization (Ma, Y. et al., 2023) [

17].

(5) Edge computing and multimodal data fusion

Edge AI, one of the latest technologies, enables field analysis and inference to reduce latency, allowing farmers to respond immediately to crop conditions or pest threats. For example, Xie et al. (2025) [

26] proposed the Farm-LightSeek framework, which integrates multimodal data (images, weather, geographic information) with lightweight AI models at the edge for faster and more efficient decision-making.

The IoT in agriculture is expected to continuously progress in the aspects mentioned above. Currently, future endeavors are mainly focused on the wider adoption of digital twins for real-time simulation and prediction of farm operations, and on further improving edge AI that will allow sensor nodes to collect data, detect symptoms, and trigger control actions with lowered dependence on cloud computing. Moreover, studies are set at enhancing multimodal data fusion (e.g., spectral imaging, meteorological, soil, UAV data) with AI/ML models to improve accuracy. These explorations are all aimed at achieving sustainability by establishing water- and energy-saving designs to minimize ecological impact.

Technical Innovation and Contributions of This Study

Compared to existing IoT applications that primarily focus on irrigation, climate monitoring, or livestock management, this study developed an innovative application for invasive plant management, specifically targeting M. micrantha. Its key features include:

Closed-loop design that integrates sensing, decision-making, and actuation to trigger automated spraying based on sensor data.

Modular architecture consisting of independent modules for environmental monitoring, spraying control, remote supervision, and delivering alerts for more flexible upgrades and easier maintenance.

Remote interface integration that allows users to monitor operations and adjust parameters through their mobile devices instead of making on-site manual adjustments, which is typically required in traditional WSN systems.

Novel application domain where the primary emphasis is controlling an invasive plant species, being one of the first to address this issue with an IoT-based field solution, while balancing sustainability and reducing labor costs.

Social dissemination potential through the Young Farmers’ Association as a dissemination channel, demonstrating the system’s scalability and policy/industry transfer potential.

2.4. Design Science Research (DSR)

In agricultural technology, Design Science Research (DSR) involves designing and validating innovative systems or tools, with emphasis on establishing a complete cycle that begins with problem identification and culminates in solutions; field testing and iterative improvement are also important components that will finalize the cycle. DSR has been recently applied in the design of smart irrigation systems, the development of farm data management platforms, and the implementation of IoT-based pest and disease monitoring systems. Such studies have provided conceptual frameworks, prototype implementations, and experimental data which ensured that the outcomes are theoretically feasible and practically applicable (Zhang, R. et al., 2025; Soussi, A. et al., 2024) [

21,

31].

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is commonly used to evaluate farmers’ or farm managers’ willingness to adopt new technologies, particularly smart agriculture platforms, mobile applications, UAVs, and sensor-based systems. It has been observed that perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) are key factors that determine the successful adoption of such technologies. Numerous studies gather data through surveys or interviews after system testing; then, TAM is utilized to assess users’ willingness to continue using the system in the long run. Subsequently, the system interfaces and functions are adjusted based on the results to enhance acceptance (Yeo, M.L. et al., 2023; Yang, Q. et al., 2024; Araújo, S.O. et al., 2020) [

1,

27,

28].

Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) has been widely applied in agricultural technology to assess the economic feasibility of innovations. It compares the cost saved from reduced water consumption, fertilizer usage, and labor with the investment and maintenance costs of the technology. By calculating payback periods, policymakers and farmers are provided with evidence-based decision-making tools to aid in determining whether large-scale adoption of the technology is justified.

Overall, DSR offers a systematic framework for research design, TAM ensures user-level acceptance of the technology, and CBA evaluates its economic viability. These three approaches allow agricultural technology research to address innovation, usability, and practical value (Sanyaolu, M. et al., 2024; Bahmutsky, S. et al., 2024) [

2,

20].

This present paper adopted a multi-layered research approach by integrating DSR, CEI, TAM, and CBA to establish a comprehensive framework that addresses technical, performance, user, and economic dimensions. The DSR provided systematic guidance in the establishment of the research process, the CEI presented an objective and comparable indicator for quantifying weed control effectiveness, enhancing the reproducibility of results, the TAM validated the system’s functional performance and ensured long-term user acceptance and adoption, and finally, the CBA enabled the quantification of investment returns and cost-effectiveness.

In contrast to many smart agriculture studies that focus on a single dimension, our research offers a holistic framework that guarantees academic rigor, technical practicality, user-friendliness, and economic viability, proving its potential for wider adoption and commercial implementation.

Table 1.

Application of DSR, CEI, TAM, and CBA in This Study and Their Innovations.

Table 1.

Application of DSR, CEI, TAM, and CBA in This Study and Their Innovations.

| Method |

Application in This Study |

Differences/Innovations Compared with Existing Research |

DSR

(Design Science Research) |

Applied DSR process: problem identification → system design → prototype construction → field testing → optimization and deployment. |

Many IoT studies in agriculture remain at the conceptual or experimental testing stage, while this study involves a full cycle of systematic design and iteration, with actual field deployment, enhancing external validity and applicability. |

CEI

(Control Efficiency Index) |

Designed CEI as an indicator to quantify changes in weed coverage before and after treatment; set ≥80% coverage reduction as the effective control standard. |

Existing literature often uses descriptive comparison of weed coverage, while this study established a standardized efficiency indicator for reproducible, cross-site benchmarking and continuous application in future studies. |

| TAM (Technology Acceptance Model) |

Conducted interviews/surveys measuring PU (Perceived Usefulness) and PEOU (Perceived Ease of Use) to analyze user acceptance and willingness to adopt. |

Many IoT system evaluations lack a systematic user acceptance assessment. Meanwhile, user perception factors are quantified in this study to ensure that the system is technically sound and socially acceptable to farmers. |

CBA

(Cost-Benefit Analysis) |

Calculated reductions in labor cost and pesticide use, and estimated payback period. |

In contrast to conventional studies, which often end with reporting technical effectiveness, this study included an economic decision-making dimension that supports policymakers and farmers in evaluating the value of large-scale adoption. |

2.5. Summary

This study adopted an interdisciplinary approach to control M. micrantha. The research team, with a strong background in industrial design, applied product-oriented problem-solving methods for both functionality and user experience, ensuring that the solution would lead to practical implementation. The project integrates three technological pillars:

Internet of Things (IoT): A network of sensors is used to continuously collect environmental data (e.g., temperature, humidity, soil conditions, and pest information), which is analyzed through decision-support systems for a more precise weed management, enhanced efficiency, and reduced resource waste.

Industrial Design: The design process is incorporated with aspects such as form, material selection, and human–machine interaction to ensure that the device is practical, durable, and aligned with farmers’ needs while maintaining aesthetic value.

Automatic Control: Automated modules are employed to regulate spraying and image collection with real-time feedback systems, allowing farmers to monitor and adjust operations remotely through smart devices. With this, labor requirements and operational costs are significantly lessened.

Through AIoT technologies, remote monitoring, automated spraying modules, and plant extract-based suppression strategies, this study aims to curb the rapid spread of M. micrantha. This solution was applied to the Cinnamomum kanehirae (bull camphor) plantation and showed promising results. Moreover, its potential applicability to long-term crop fields and low- to mid-altitude forests has been observed. By leveraging technological innovation, this study intends to fundamentally mitigate the ecological and agricultural threats posed by M. micrantha, delivering a precise, sustainable, and labor-efficient smart control system.

3. Materials and Methods

This study collaborated with young farmers in Miaoli, Taiwan, academic experts, and graduate students to create a team that will address the challenges of invasive species management. The DSR framework was adopted to ensure systematic and scientific rigor. Initially, problem identification and motivation analysis through field interviews and literature reviews were conducted to determine the agricultural threats posed by M. micrantha. Based on this, a comprehensive system architecture was established, consisting of IoT monitoring, remote control, automated spraying, and possible biocontrol techniques to formulate potential solutions.

The selected technologies were employed to design the system and the prototype with considerations on energy supply, sensor layout, and interface usability to ensure that the device would be adaptable to farm environments; through this, technical concepts were translated into a tangible product. After completion of the prototype, the system was evaluated through small-scale testing to verify its stability, data accuracy, and automated spraying performance. Next, the CEI was conducted to quantify the effectiveness of the weed control by measuring the changes in weed coverage before and after intervention; a CEI ≥ 80% entailed significant control effectiveness.

During the field deployment stage, the device was installed at the Shan-Shang Forest Leisure Farm in Dahu, Miaoli, Taiwan. Remote monitoring and data feedback were used to record weed control outcomes. At the same time, user feedback was collected, and the TAM was employed to analyze farmers’ PU and PEOU, ensuring that the system met user needs and enhanced adoption intention.

Once the field results validated the feasibility and effectiveness of the system, the CBA was employed to assess the economic advantages of lower labor costs and decreased weeding frequency, while calculating the return on investment (ROI) as a basis for determining whether large-scale adoption is possible.

Finally, in line with DSR’s iterative improvement and dissemination stages, results of the field trial, CEI, TAM, and CBA were integrated to further optimize the system design. Additional plans were also formulated to extend deployment to other farms and diverse cropping systems, since the long-term goal of this study is to apply the system to manage other invasive plant species. Through this, its value and societal impact are extended.

3.1. Research Framework (DSR Approach)

DSR has been widely applied in many fields such as information systems, engineering design, and human–computer interaction. Unlike traditional research methods that focus on describing phenomena, DSR proposes innovative solutions to real-world problems and validates their effectiveness through design, construction, testing, and iterative refinement. Its core objective is to create useful artifacts while simultaneously accumulating design knowledge that can be reused and extended in future research for reproducible and generalizable outcomes.

This study adopted the DSR approach because the issue entails designing and validating a smart weed control system that can effectively manage M. micrantha, and not just merely observing a natural phenomenon. Field interviews and literature reviews were first conducted to identify the problem, and then an IoT architecture and the control modules were developed. Next, a physical prototype was constructed and tested in real farm environments. Through the iterative process of DSR, sensor configurations, control logic, and user interfaces were adjusted after each testing cycle to better align with farmers’ practical needs.

In summary, using DSR ensured that the results of this research are academically sound and can be applied in real-world settings. This study can thus be clearly positioned as an applied case of DSR. The methodology highlights the creation, validation, and optimization of artifacts in real-world problem contexts, typically following five iterative steps: problem identification, solution design, implementation, evaluation, and refinement.

Table 2.

The design and experimental validation of this study correspond to the following five DSR steps.

Table 2.

The design and experimental validation of this study correspond to the following five DSR steps.

| DSR Stage |

Corresponding Actions |

| Problem Identification & Motivation |

Field interviews and literature review were conducted to determine the ecological threat of M. micrantha and farmers’ problem points. |

| Solution Design |

An IoT architecture was proposed, consisting of design sensing, spraying, and remote monitoring/control modules. |

| Prototype Build |

The first-generation device prototype was developed, integrating hardware and software. |

| Field Evaluation |

A 6-month field test was carried out, collecting environmental data and monitoring changes in weed coverage. |

| Improve & Deploy |

The system was refined based on farmers’ feedback, and large-scale deployment in other farms was planned. |

4. Results

This study interviewed local young farmers to obtain first-hand insights and understand the challenges they face in dealing with M. micrantha. The in-depth interviews provided practical information that has not been previously captured by other studies, such as the actual growth conditions of M. micrantha, and the current control measures being utilized and their effectiveness. This also validated and complemented the accuracy of earlier survey data.

The field site chosen for this study was the Shan-Shang Forest Leisure Farm, located in Dahu Township, Miaoli County, Taiwan, which cultivates Cinnamomum kanehirae, a native tree that is officially listed as a valuable and protected species. C. kanehirae is valued for its timber, which is mostly used for carving and furniture-making, and for its leaves and branches, which are processed for essential oils. More importantly, the tree supports the growth of Antrodia cinnamomea, a rare medicinal fungus.

For over a decade, the farm has refrained from using herbicides, managed the land sustainably, and used environmentally friendly practices. As one of the few farms in Taiwan dedicated to the cultivation and protection of C. kanehirae, the Shan-Shang Forest Leisure Farm represents not only an ecological asset but also an important cultural and economic heritage for Miaoli and Taiwan as a whole.

4.1.1. Field Interviews

This study collaborated with Mr. Lan, the owner of the Shan-Shang Forest Leisure Farm, and other local farmers to address the issues that they are experiencing from M. micrantha. The interview questions were designed to collect first-hand information on the agricultural impacts of the invasive species and to verify the accuracy of existing data, providing valuable insights into farmers’ practical difficulties and needs. The data obtained served as the foundation for product design and technological application.

Before the interviews, the research team investigated the growth environment of M. micrantha, the local agricultural context, and current control methods. During the on-site interviews, the orchards and C. kanehirae plantations were visited to directly observe the distribution of M. micrantha. Some of the issues discussed with farmers include: the extent of crop damage, the effectiveness and limitations of existing control strategies, and their technical requirements. Photos and videos were also taken to document the weed’s growth for subsequent analysis.

4.1.2. Online Interviews

To complement the on-site visits, online interviews were conducted with farmers and experts who were unable to attend in person. A list of questions was prepared in advance, focusing on key issues such as the applicability of control technologies, the frequency and difficulties of manual weeding, and the demand for mechanized equipment. The interviews were conducted either via video conferencing or phone calls, with transcripts and audio recordings archived. Some participants also shared farm photos and data to enrich the field observations and ensure data completeness.

4.1.3. Interview Results

The two young farmers who agreed to our request for an interview were Mr. L, who manages a C. kanehirae (bull camphor) plantation, and Mr. H, who manages an orchard that cultivates citrus trees.

Farmer A (Mr. L, managing a camphor plantation)

Main Concern: M. micrantha attaches to camphor seedlings, causing high mortality rates, with losses of up to 30%.

Current Control: Mainly relies on manual removal, which is laborious, costly, and ineffective because of the weed’s capacity to regenerate quickly.

Key Needs: A durable and less laborious control device that will reduce the frequency of weeding.

Expectation: The equipment should adapt to the plantation environment and prevent seedlings from being strangled.

Farmer B (Mr. H, managing a citrus orchard)

Main Concern: M. micrantha grows on fruit trees, obstructing ventilation and photosynthesis, which leads to reduced yield and poor fruit quality. This, in turn, results in financial losses.

Current Control: Also practices manual weeding, but because it has limited effects, they also rely on conventional herbicide spraying, which raises environmental and safety concerns.

Key Needs: A system that can reduce the frequency of manual weeding and maintain tree health.

Expectation: The equipment should be both efficient and environmentally friendly, and be flexible enough for use in different terrains.

Common Needs and Perspectives

M. micrantha severely affects crop growth, quality, and yield.

Existing control methods (manual weeding and herbicides) are inadequate due to high labor demands, costs, or environmental risks.

-

Farmers expect the system to:

Reduce labor input (lower frequency of manual removal).

Have better long-term control effectiveness that avoid rapid regrowth.

Ensure environmental sustainability by minimizing herbicide pollution.

Adapt to diverse agricultural and forestry settings (orchards and plantations).

4.1.4. Key Findings

The interview results were consolidated to identify common needs among farmers, which were incorporated into the design of the weeding device to improve its usability and acceptance. Mr. L reported that insufficient management in the past led to the spread of M. micrantha, which resulted in a seedling mortality rate of up to 30% in C. kanehirae plantations. This caused significant damage to the forest’s ecosystem. Similarly, Mr. H, noted that M. micrantha resulted in reduced ventilation and sunlight exposure in fruit-bearing trees, leading to lower fruit quality, reduced yield, and direct economic losses. These first-hand findings revealed the real-life challenges faced by local farmers and served as a critical guide for designing and optimizing the proposed control device.

4.1.5. Field Investigation

On April 16, 2024, the research team, together with experts in the field, visited the C. kanehirae forest for a site survey. Several feasible installation sites as well as a monitoring station were identified, and feasible implementation plans were discussed to prevent and control M. micrantha.

Figure 1.

On-site survey and monitoring station installation distance measurement.

Figure 1.

On-site survey and monitoring station installation distance measurement.

4.2. Solution Design (DSR)

4.2.1. Module Planning

After identifying the problems and requirements, the research team explored applicable AIoT technologies that could be integrated with existing smart agriculture solutions for the management of an invasive species. Due to the aging agricultural workforce and severe labor shortages in Taiwan, the development of smart agriculture has become an inevitable trend alongside labor-saving cultivation techniques. By leveraging information and communication technologies (ICT) and the advancement of intelligent agricultural machinery, innovative solutions can be effectively applied to enhance the overall agricultural productivity.

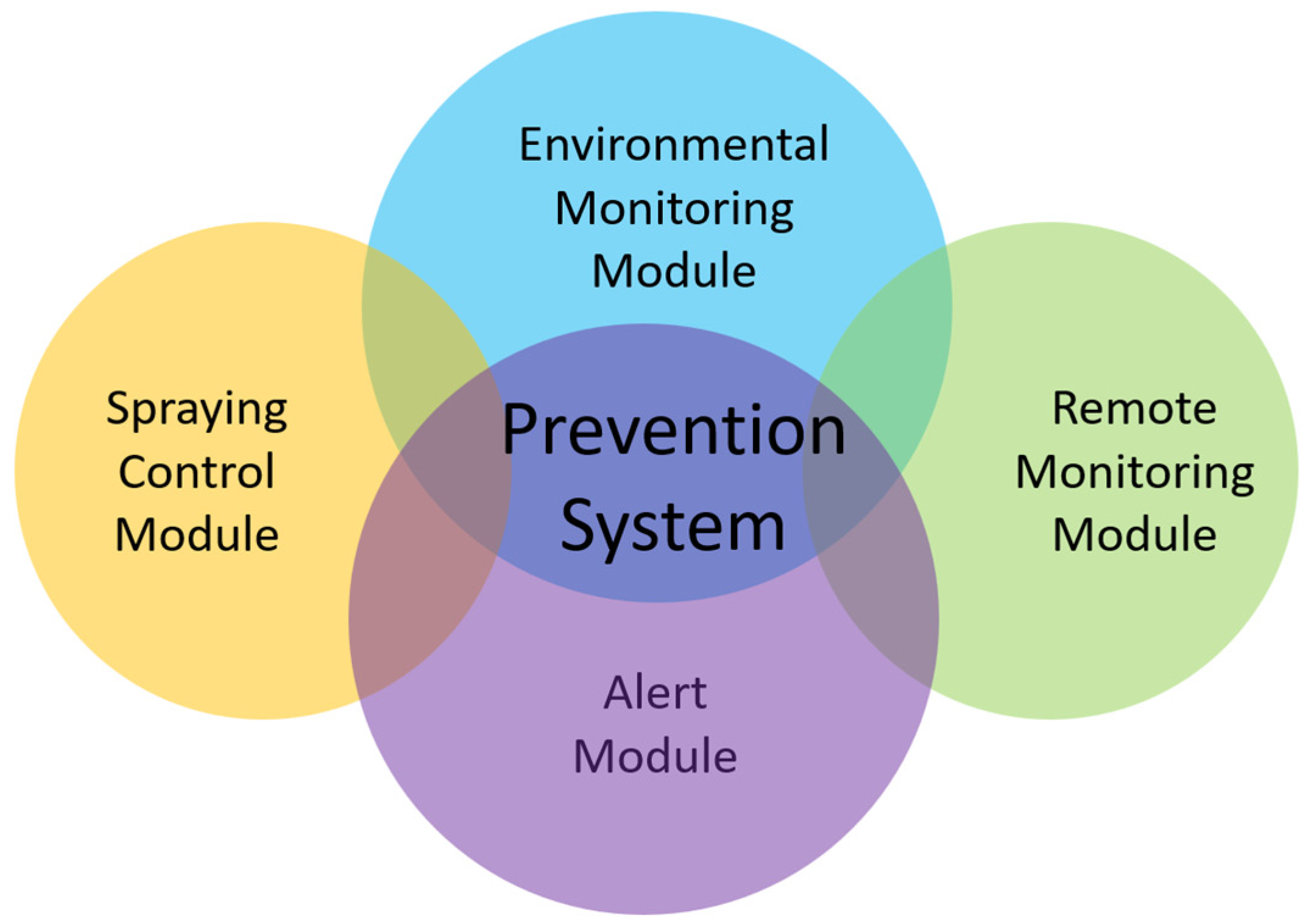

This study developed an IoT-integrated M. micrantha control device with a modular architecture consisting of four core modules:

Through AIoT technology, young farmers could use mobile phones, tablets, or computers to access both local and remote information about their camphor plantations and operate the system remotely, which will effectively reduce frequent on-site interventions. This smart management system could significantly lower the mortality rate of camphor seedlings caused by M. micrantha infestation, replace labor-intensive tasks to save time and manpower, enhance crop survival rates and agricultural productivity, and ultimately improve farmers’ quality of life.

In practice, the M. micrantha control device was deployed in camphor plantations, where automated equipment and environmental sensors are connected to a cloud-based platform to provide real-time monitoring and alert functions. For example, if the device malfunctions, the system will immediately detect the issue and send out alerts, allowing prompt response and uninterrupted control operations. Looking ahead, this study plans to optimize equipment configuration based on the specific needs of camphor plantations to achieve the best possible control outcomes.

4.2.2. Development of a Farmland Monitoring and Networking Platform

We developed a device for managing M. micrantha invasion that enables farmland environmental data to be visualized and charted through a remote application, integrating time, location, crops, and monitoring data. Through this, real-time field insights are provided to the farm managers. When the system detects abnormalities or potential risks, it automatically sends alerts to users; they can then use the device as a remote control to perform irrigation or spraying operations, thereby achieving smart monitoring and control for invasive weed management.

1. Camphor Plantation Monitoring and Networking Module

This module involves intelligent positioning, monitoring, tracking, and management, specifically applied to camphor plantations. Real-time monitoring of temperature, humidity, and soil moisture effectively reduces the frequency of on-site inspections, lowers labor costs, and improves overall economic efficiency.

2. Alert Module

Traditional agricultural sites are often located in remote areas, requiring additional manpower to patrol and inspect. As the farm scale increases, manpower demand grows proportionally. The alert module, through real-time monitoring and automated notifications, replaces extensive manual patrols, not only reducing labor requirements but also ensuring timely reporting of on-site conditions and rapid problem resolution.

3. Display Module

The display module enables farmers to view real-time data on temperature, humidity, and soil moisture via smartphones, tablets, or any display screens, which decreases the need for on-site visits. Importantly, this module supports simultaneous monitoring by multiple users, whether locally or remotely, ensuring shared real-time information and preventing losses caused by delays.

4. Automation Module

This module incorporates automatic control technology using timed and quantitative spraying devices to precisely apply herbicides. This approach reduces chemical waste, saves labor, and enhances both operational efficiency and weed control effectiveness.

Comprehensive Benefits:

By integrating the modules, the system is expected to improve the camphor plantations in Dahu Township through the following:

Reduced labor and time costs, minimizing the need for frequent patrols.

Remote monitoring to replace traditional manual practices, enhancing management efficiency.

Timed and precise spraying, reducing herbicide usage costs.

Improved efficiency and productivity for young farmers, easing labor burdens.

Lower risk of M. micrantha spread, ensuring seedling survival and crop quality.

Figure 2.

System functional module planning.

Figure 2.

System functional module planning.

4.2.3. System Architecture

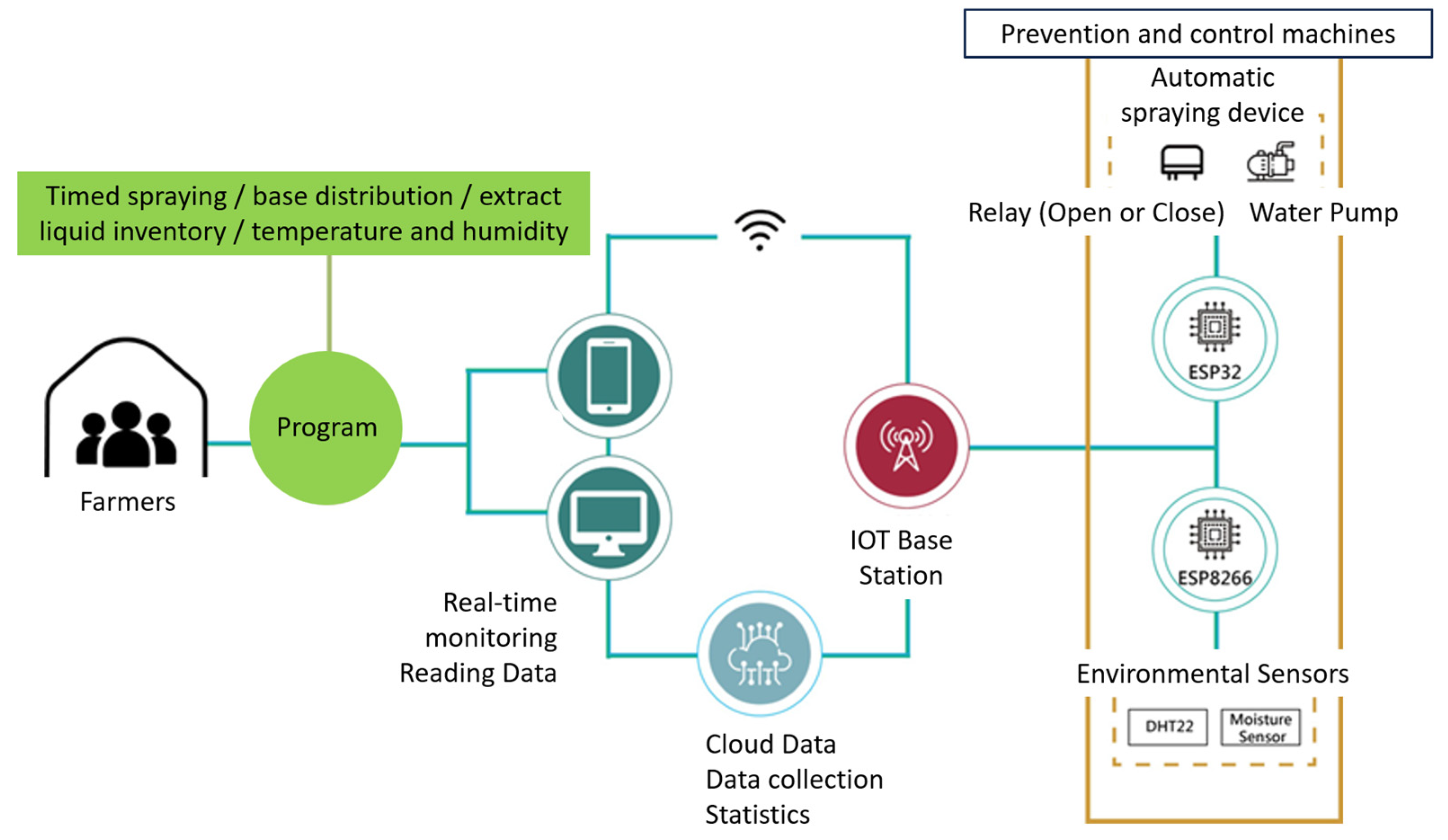

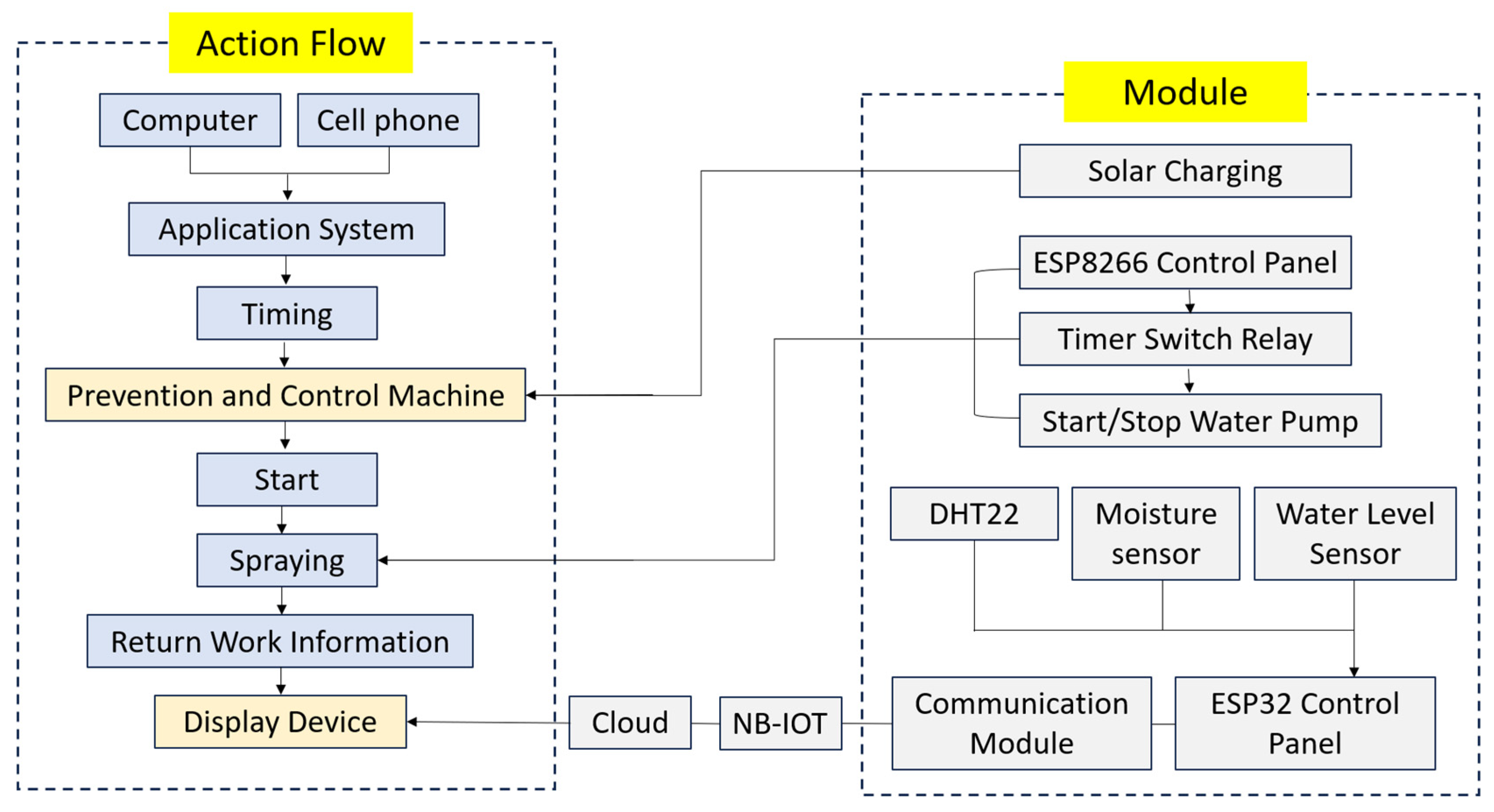

The system architecture is divided into two main components: remotely detecting farmland environmental conditions, combined with remote-control technology for irrigation and spraying operations.

1. Remote Sensing System

The remote sensing system is built on an ESP32 development board, which serves as the data acquisition unit for sensing and transmitting farmland environmental data. It is equipped with a DHT22 air temperature and humidity sensor and a soil moisture sensor, both installed in the farmland to continuously collect data. These are then transmitted via Wi-Fi and uploaded to a cloud server every 10 minutes. Users can access the data by entering an API Key through a mobile application, which retrieves the stored information from the cloud. The app has an analysis interface for viewing environmental parameters and real-time conditions to support farmland monitoring and decision-making.

2. Remote Control and Spraying Operations:

The remote-control execution unit consists of an ESP8266 module, a relay, and a water pump. Users can operate the water pump remotely through the mobile application. Once a command is sent to the ESP8266, it switches the relay from “OFF” to”ON” and vice versa, carrying out precise irrigation tasks.

In addition, the ESP32 captures images and transmits these to the server, providing live visual monitoring of the field. Meanwhile, the ESP8266 also collects temperature, humidity, wind speed, and wind direction data, and controls the spraying module to ensure that irrigation and spraying operations match environmental conditions.

This system design enables continuous monitoring of farmland conditions as well as allows effective remote intervention, which reduces the need for manual field inspections while enhancing the intelligence and efficiency of agricultural management.

Figure 3.

System architecture planning diagram.

Figure 3.

System architecture planning diagram.

Figure 4.

Action diagram and module correspondence diagram.

Figure 4.

Action diagram and module correspondence diagram.

Table 3.

Description of System Components and Functions.

Table 3.

Description of System Components and Functions.

| No. |

Component |

Function |

| 1 |

ESP8266 |

Receives remote control signals to operate the water pump |

| 2 |

Water Pump |

Performs water extraction and spraying |

| 3 |

Relay |

Switches the water pump ON or OFF |

| 4 |

ESP32 |

Collects environmental data; equipped with Wi-Fi and dual-mode Bluetooth |

| 5 |

Moisture Sensor |

Detects soil moisture levels |

| 6 |

DHT22 |

Measures temperature and humidity |

| 7 |

Water Level Sensor |

Provides warning when water level is low |

| 8 |

Solar Charger |

Supplies power for outdoor continuous operation of devices and sensors |

| 9 |

Communication Module |

Handles data transmission |

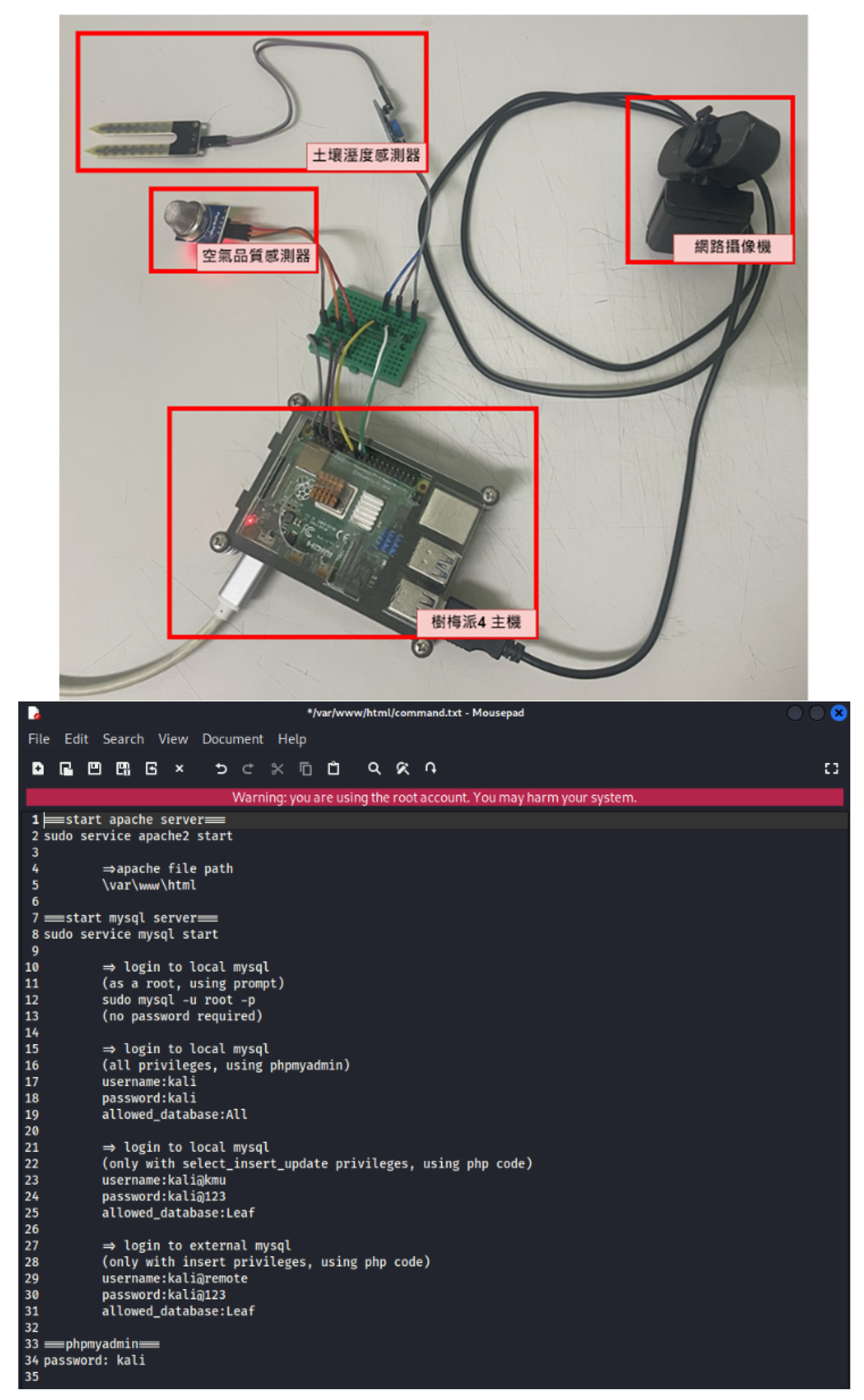

System Functions and Operations:

The Raspberry Pi, a powerful Wi-Fi microcontroller, was combined with a DHT22 sensor, a high-precision temperature and humidity sensor, for real-time monitoring of environmental temperature, humidity, and soil moisture. The functions of this system are as follows:

Environmental Monitoring: It continuously gather data for ambient temperature and humidity, which can be used in indoor and outdoor monitoring, greenhouse management, climate control, and agricultural applications.

Data Recording: Its collected data are automatically transmitted to a local server for storage.

Remote Monitoring: Using its Wi-Fi connectivity, data are uploaded to a cloud server, allowing users to access real-time information from any location.

Device Control: The system allows users to control devices (e.g., irrigation, spraying, or ventilation systems) to perform certain tasks, thereby achieving smart farming.

System Workflow:

System Initialization: Once powered on, the device automatically starts Apache and MySQL services. Next, it enters the desktop interface, then launches the recognition page and turns on the camera to capture images and identify the targets.

Data Processing and Storage: Recognition results are categorized and automatically saved in the corresponding database tables. The system ensures that the local MySQL and an external MySQL database are synchronized. If network connectivity is unreliable, there might be interruptions in the external database; nevertheless, the local database consistently maintains complete records.

Invasion Alerts: When M. micrantha is identified (confidence level set at 87%), the system sends an alert via Line group notification, which guarantees that farmers are informed of the warnings in real time.

Sensor Notifications: The system issues periodic Line broadcast notifications of soil and air sensor data regardless of the readings, enabling continuous observation of the farm’s environment.

The integration of the Raspberry Pi with the DHT22 sensor allows real-time environmental monitoring, data storage, remote access, and device control, all while incorporating image recognition and alert notifications. Through this, the timeliness and precision of agricultural management are significantly improved, making it highly suitable for IoT-based applications and scalable for diverse agricultural needs.

Figure 5.

Soil temperature and humidity monitoring components / system-related instructions.

Figure 5.

Soil temperature and humidity monitoring components / system-related instructions.

Figure 6.

Internal and External MySQL Table Structure and Data 1 (M. micrantha Identification Results) [Note] Soil test results (0 indicates humidity, 1 indicates humidity); air test results (0 indicates CO2 levels, 1 indicates CO2 levels).

Figure 6.

Internal and External MySQL Table Structure and Data 1 (M. micrantha Identification Results) [Note] Soil test results (0 indicates humidity, 1 indicates humidity); air test results (0 indicates CO2 levels, 1 indicates CO2 levels).

Figure 7.

A LINE group notification / Recognition effect video sent by the system.

Figure 7.

A LINE group notification / Recognition effect video sent by the system.

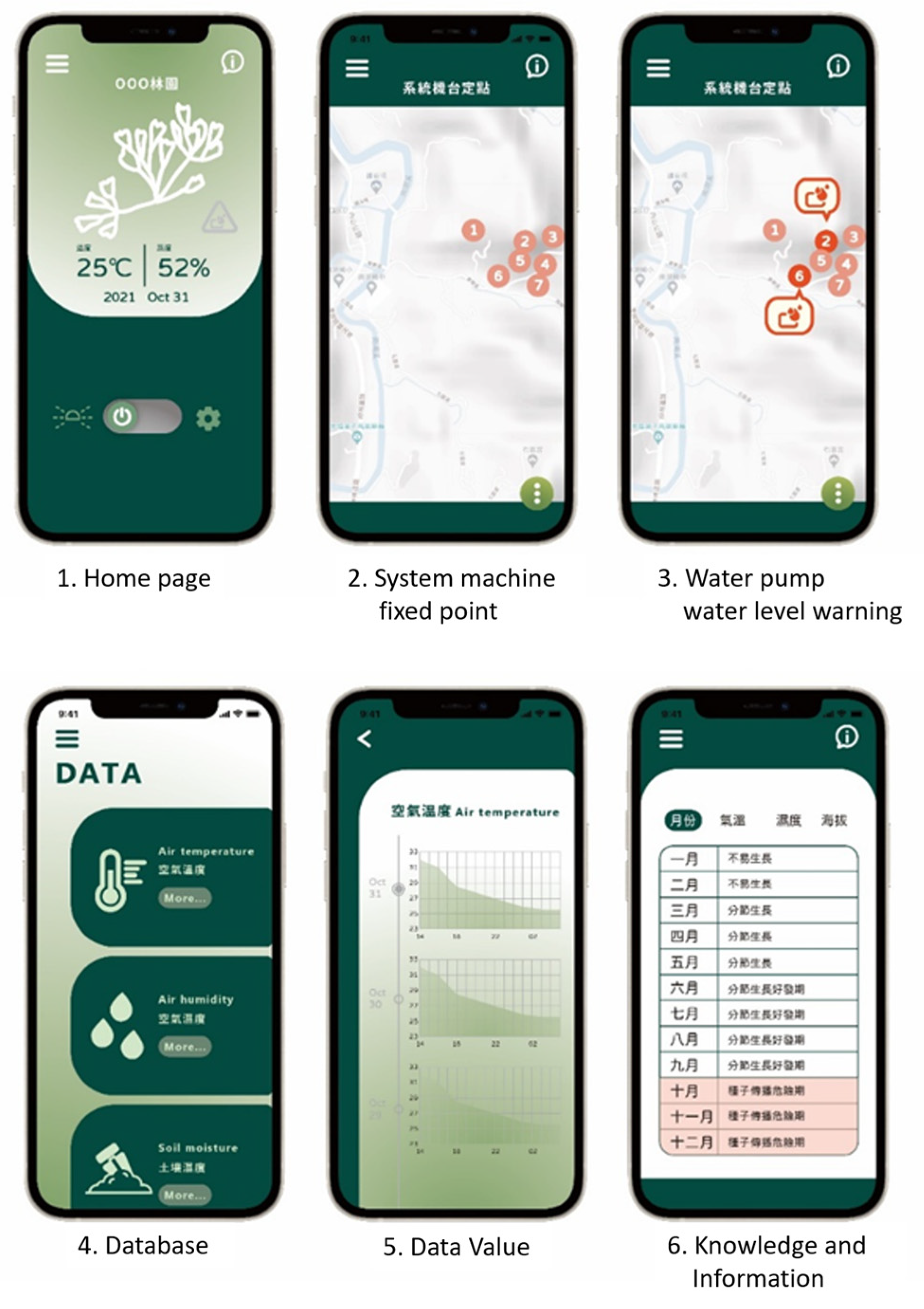

4.2.4. System Functions and Mobile Application Interfaces Design

This system employs IoT technology to transmit real-time data gathered by the sensors installed in the forests and farmland to a mobile application (APP). This allows users to monitor environmental data (temperature, humidity), check the operation status of the device, and receive alert notifications at any time.

Figure 8 illustrates the six key interface functions, which are described below:

Displays air temperature and humidity.

Provides a real-time status of M. micrantha (vegetative growth stage, flowering stage, fruiting stage).

- 2.

Device Status Interface (Second and Third Screens)

Allows users to monitor the operation of each machine via device ID and IoT settings.

Displays real-time operational status and alert messages for quick troubleshooting.

Shows a flashing alert icon (gray symbol) on the home screen when the water pump level is abnormal.

- 3.

Data Monitoring Interface (Fourth and Fifth Screens)

Provides data on the stats of air temperature, air humidity, and soil moisture.

Users can tap on each data category to view the records and trend charts (updated every two hours).

A slider at the bottom allows users to activate the sprinkler.

The settings button in the top-right corner can be used to adjust the automatic irrigation parameters.

Assists farmers in tracking environmental changes and making informed irrigation and control decisions.

- 4.

Knowledge Information Interface (Sixth Screen)

Information on M. micrantha can be accessed by tapping the “i” icon in the top-right corner.

Provides scientific knowledge about its occurrence period, rapid growth factors, and related risks.

Helps farmers activate the system functions at the correct time for more efficient management of the invasive species.

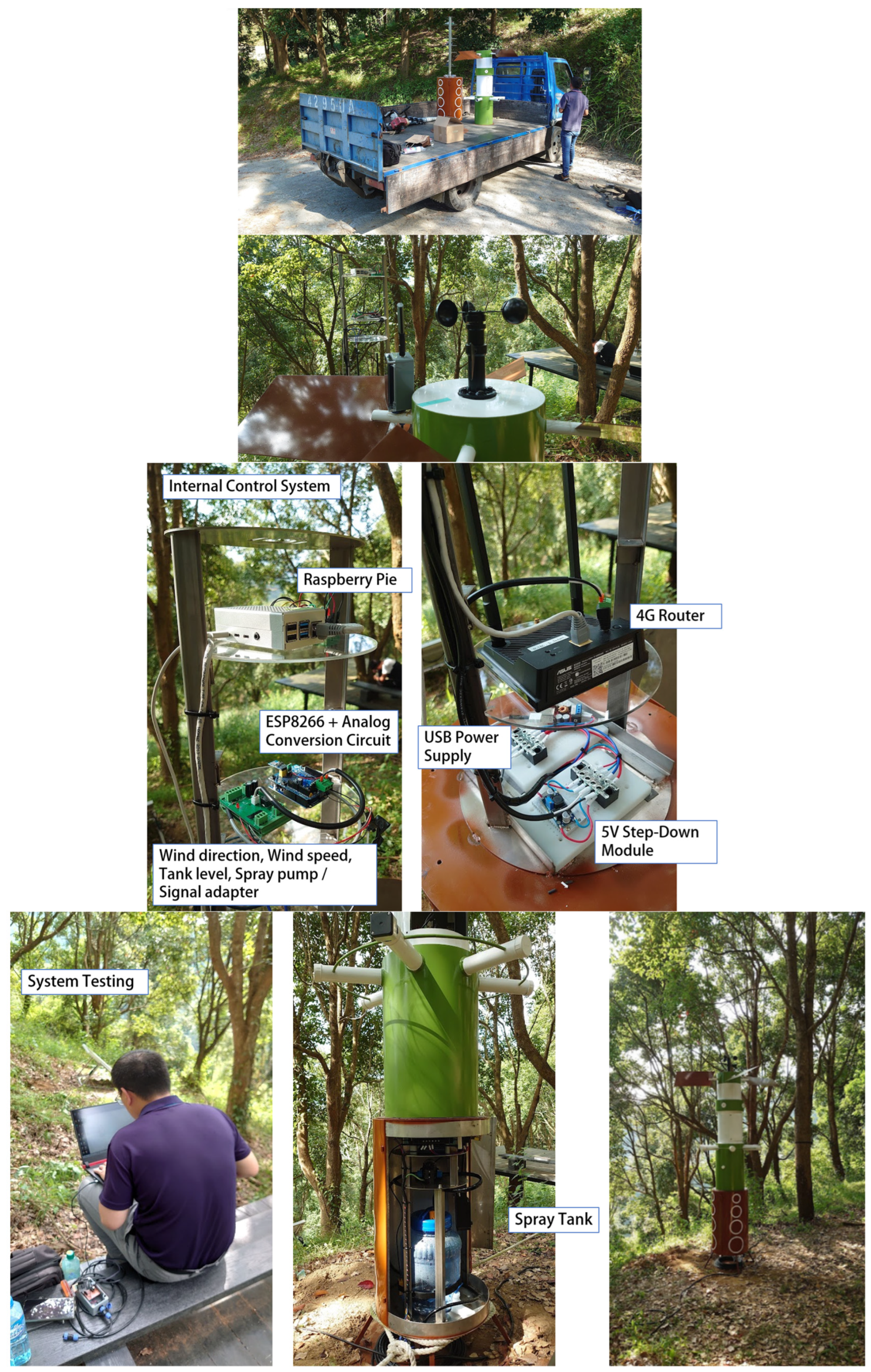

4.3. Prototype Build (DSR)

The project team was formed in February 2023, which initiated the design process and officially launched the study. The team was divided into eight groups of students assigned to different aspects of the simulation design, including the investigation of existing weather stations, data collection of required components, analysis of system architecture, and drafting of sketches. Weekly meetings were held to review their progress, discuss results, and make necessary adjustments.

After the initial simulations and analyses were completed, 3D modeling was done, and scaled-down prototypes were 3D-printed to verify the integrity and feasibility of the overall design, ensuring that the system architecture meets practical application requirements.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagrams of some of the 3D models.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagrams of some of the 3D models.

Meeting with the Manufacturer and Sample Production

Following simulation design, system architecture analysis, and sketching, the team met with the manufacturer to discuss the feasibility of the sample device.

Figure 10.

Meeting and discussion with the manufacturer, and assembly and testing of the sample device.

Figure 10.

Meeting and discussion with the manufacturer, and assembly and testing of the sample device.

4.4. Field Evaluation (DSR)

The team visited the camphor forest on 10th November 2023 to install and assemble the system on the same day. It was then tested on 13th November 2023, and all system operations were completed. The installation test results are presented in

Figure 11.

The control device was installed at the Niu-Chang Forest Leisure Farm for a 6-month field trial. During the experiment, the research team continuously monitored the system’s operational stability under varying weather conditions, the accuracy of environmental data collection, and the effectiveness of the spraying module. Compared with the control plots, the results indicated that the device effectively suppressed the growth and spread of M. micrantha.

Since most of the monitoring and control processes were automated by the system, manual weeding significantly decreased, thereby lowering farmers’ labor costs. The device’s intelligent operation and remote monitoring functions further allowed farmers to track the progress of weed control and farming conditions in real time, which enhanced the efficiency of managing the invasive species.

Overall, the trial results confirmed the stability of the device and the system’s high data reliability. The monitoring module provided accurate environmental information for further analysis, while the spraying module delivered precise application during the peak growth stages of M. micrantha, which substantially lowered labor input and improved control effectiveness.

4.5. Improve & Deploy (DSR)

4.5.1. User Feedback (Summary of Farmer Interviews)

Based on preliminary interviews and field testing, the feedback from farmers is generally positive. After testing the system and achieving successful outcomes, they found the introduction of the IoT monitoring system highly beneficial and effective in reducing the frequency of on-site inspections. According to them, it was convenient to use the system for monitoring farm conditions in real time through their mobile phones. Further, the system’s ability to transmit photos from the orchard and conduct on-device recognition directly on the phone significantly improved their monitoring efficiency and responsiveness. Nevertheless, farmers emphasized that, for ecological conservation and to ensure complete eradication, periodic manual weeding would still be necessary as a complementary measure.

4.5.2. Control Efficiency Index, CEI

The CEI was obtained to objectively measure the control effectiveness of the system. It is designed to compare the change in weed coverage before and after intervention to quantify the system’s effectiveness in suppressing weed proliferation. A higher CEI value indicates better control performance; when the CEI ≥ 80%, it is considered to have achieved a significant suppression effect. It is calculated using the following formula and the six steps described below:

Where:

Co:Weed coverage rate before testing (baseline value)

Ct:Weed coverage rate after testing

Steps in calculating the CEI:

Define the experimental area: establish the boundary of the test plot.

Set up sampling plots or transects: e.g., using 1 m × 1 m quadrats.

Data collection: conduct visual estimation, ground photography, or UAV aerial imaging.

Area measurement: record manually or analyze images to determine coverage.

Coverage calculation: area covered by the weed divided by the total area

Establish baseline data: use the initial measurements as a reference for subsequent CEI calculations.

Figure 12.

Demarcation of the test sample area.

Figure 12.

Demarcation of the test sample area.

The results of this study showed that the weed control efficiency gradually improved from an initial CEI of 46% in the first month to 87% by the third month. Consequently, the frequency of manual weeding decreased significantly, from once every three days to once every seven days. This indicates that the smart weeding system effectively suppressed the growth of M. micrantha (reduction in coverage by 87%), leading to decreased labor costs and improved ecological conditions. Ultimately, CEI is expected to serve as a standardized performance indicator for future research and practical deployment, supporting the broader promotion and application of this technology across various agricultural settings.

Table 4.

Control Efficiency Index (CEI) data.

Table 4.

Control Efficiency Index (CEI) data.

| |

Total Area

(Hectares)

|

Coverage |

Area

(Hectares)

|

CEI

(%)

|

Days |

Average Weeding (times/days) |

Average Weeding (times/month) |

| Month 0 |

7.24 |

0.54 |

3.91 |

46 |

30 |

3 |

10.00 |

| Month 1 |

7.24 |

0.43 |

3.11 |

57 |

30 |

5 |

6.20 |

| Month 2 |

7.24 |

0.24 |

1.74 |

76 |

30 |

6 |

5.00 |

| Month 3 |

7.24 |

0.18 |

1.30 |

82 |

30 |

7 |

4.43 |

| Month 4 |

7.24 |

0.15 |

1.09 |

85 |

30 |

7 |

4.29 |

| Month 5 |

7.24 |

0.13 |

0.94 |

87 |

30 |

7 |

4.43 |

4.5.3. Technology Acceptance Model, TAM

The TAM is widely used to understand users’ acceptance and adoption behaviors toward new technologies. In this study, it was used to evaluate the user acceptance of the smart weed control system.

Through farmer interviews and questionnaire feedback, two key dimensions of TAM were analyzed: Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU). According to the farmers, the system effectively reduced the frequency of on-site inspections and manual weeding; thus, it provided them with practical benefits for farm management. Moreover, they found the mobile monitoring interface intuitive and easy to operate, with timely alert notifications that enhanced usability and reliability.

By incorporating TAM into this study, the system was evaluated beyond the technological aspect to encompass human–technology interaction, ensuring its long-term feasibility and scalability in practical agricultural applications.

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) Measurement and Calculation

To determine the TAM, a structured process is performed involving survey design, followed by a Likert-scale scoring, and then statistical analysis. The following outlines the key steps and computational logic applied in this study.

1. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

The core constructs of TAM include:

Each construct consisted of three to five questionnaire items, with respondents rating their agreement using a five- or seven-point Likert scale (e.g., 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree).

TAM Questionnaire Design

1. Perceived Usefulness (PU)

Using this IoT weed-control system effectively reduces the spread of M. micrantha.

The system helps me save labor time and reduce manual weeding costs.

Using this system improves my productivity and the quality of my crops.

Overall, this system is valuable to my agricultural management practices.

2. Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)

I can easily learn how to operate this IoT weed-control system.

The system interface (e.g., mobile app or control platform) is easy to understand and use.

Using this system in my daily work does not cause any difficulties.

I believe that even without a technical background, I can conveniently use this system.

3. Attitude Toward Use (ATU) (optional construct; included in some TAM models)

I believe that using this IoT weed-control system is a good idea.

For me, using this system is worth trying.

My overall impression of using this system is positive.

4. Behavioral Intention to Use (BI)

If available in the future, I am willing to continue using this IoT weed-control system.

I would recommend this system to other farmers or peers in the agricultural sector.

If promoted by the farmers’ association or government, I am willing to adopt this system as a primary weed-control tool.

Questionnaire Results

To explore users’ acceptance of the system, this study analyzed the findings in TAM’s PU and PEOU. This correspondence helps transform user experiences into quantifiable and interpretable theoretical evidence, thereby reinforcing the rationale for promoting the broader implementation of the system.

Table 5.

TAM Constructs and Corresponding User Feedback.

Table 5.

TAM Constructs and Corresponding User Feedback.

TAM

Construct

|

Interview Feedback from This Study |

Empirical Observation |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) |

Farmers reported that the system helped “reduce the number of field visits” and “lower the frequency of manual weeding.” |

Labor costs were reduced by approximately 33%, and the CEI by 87%. |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) |

Farmers found the mobile monitoring interface intuitive and convenient to operate. |

Users were able to learn the system operation quickly, and alert notifications responded in real time. |

The findings showed that participating farmers rated both PU (4.15 ± 0.62) and BI (4.22 ± 0.55) above 4.0, which indicates that they generally believe the system is effective in reducing labor demands and improving weed control efficiency, and that they are willing to continue using it in the future.

Meanwhile, the PEOU (3.78 ± 0.74) was relatively low, suggesting that some users found the system’s operation interface required additional optimization to make it more convenient and easier to use.

As shown in

Table 6, BI and PU received the highest ratings, reflecting that farmers recognized the system’s value and expressed willingness to adopt it. Meanwhile, the low score of PEOU indicates room for improvement in interface design and user experience.

A total of four valid questionnaires were collected in this study. Although the sample size is limited, the data provided preliminary insights into user perceptions of the system. Based on the findings, farmers perceive the IoT weed control system as useful and worth adopting; however, they noted that its ease of operation needs improvement.

These results should be interpreted as exploratory observations rather than statistically representative findings. Future studies should involve larger sample sizes to further validate the system’s acceptance and refine its design.

4.5.4. Cost-Benefit Analysis, CBA

The CBA was employed in this study to determine whether the new technology, the IoT-based M. micrantha control system, is economically viable or “worth the investment.” It is calculated using the following steps:

Define the Cost and Benefit Components: Identify all relevant cost items (e.g., equipment, installation, maintenance, and labor) and benefit items (e.g., labor savings, yield improvement, reduced chemical usage).

Calculate Net Benefit (NB): NB=Total Benefit−Total Cost

Determine the Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR): When BCR > 1, the benefits exceed the costs, indicating that the investment is economically feasible; conversely, when BCR < 1, the benefits are less than the costs, suggesting that the investment is not worthwhile.

Evaluate the Payback Period: The payback period indicates the time in years needed for the accumulated benefits to recover the initial investment cost.

The CBA results for this study are as follows:

Total Cost (First Year) = Initial Investment (250,000) + Maintenance (25,000) = 275,000 NTD

Total Annual Benefit = 40,000 NTD

Net Benefit (NB) = Total Benefit (40,000) − Annual Maintenance (25,000) = 15,000 NTD / year

Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR) = 40,000 ÷ 275,000 ≈ 0.15 (First Year)

Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR) = 40,000 ÷ 25,000 ≈ 1.6 (Annual)

Payback Period = 25,000 ÷ 15,000 ≈ 1.67 years

Originally, manual weeding was performed once every two months (six times a year), requiring two days per session at 2,500 NTD/day, for a total of 30,000 NTD per year.

After the system was implemented, the weeding frequency was reduced to once every six months (two times per year), totaling 10,000 NTD annually.

Table 7.

Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA).

Table 7.

Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA).

| Item |

Description |

Amount (NTD) |

Remarks |

| Initial Investment Cost |

Purchase of equipment (sensors, controllers, sprayer units) |

200,000 |

One-time expense |

| Installation and setup |

50,000 |

One-time expense |

| Annual Maintenance Cost |

System maintenance and consumables |

15,000 |

Fixed annual cost |

| Electricity consumption |

5,000 |

Fixed annual cost |

| Chemical usage |

5,000 |

Reduced usage due to precision spraying |

| Annual Benefits |

Savings in manual weeding labor cost |

20,000 |

Original cost: NTD 30,000/year

→ reduced to 10,000/year |

| Increased crop yield |

20,000 |

Improved production and quality |

The analysis shows that in the first year, the BCR < 1 because of the equipment expenses, indicating that the system failed to recover the cost in the short term. Nevertheless, starting from the second year, when only the maintenance costs are expected, the computed annual BCR increased to 1.6, and the payback period obtained was approximately 1.67 years. These results suggest that the IoT-based weed control system has a strong medium- to long-term economic viability and holds considerable potential for large-scale implementation.

5. Discussion

5.1. System Applicability Under Different Environmental Conditions

The M. micrantha control system developed in this study was field-tested for six months in the Shan Shang Zhong Shu Cinnamomum Kanehirae Forest Farm in Dahu, Miaoli, Taiwan. The results demonstrated that the system remained stable and continued to be reliable under diverse climatic conditions. It was observed that the sensing modules effectively monitored key environmental parameters such as air temperature, humidity, and soil moisture, and data transmission performance was generally consistent.

However, during periods of high humidity and heavy rainfall, certain sensors had delays and minor inaccuracies. This suggests that the waterproofing of the device and the stability of communication need to be improved to prevent problems from occurring during extreme weather or low network signal conditions. Overall, the system proved to be highly adaptable to Taiwan’s mid- and low-altitude agricultural and forestry environments and shows strong potential for expansion to other regions.

5.2. Comparison with Traditional Control Methods

Compared to conventional weed control methods such as manual weeding and chemical spraying, the proposed IoT-based intelligent control system demonstrates significant advantages such as reduced labor costs, environmental sustainability, and enhanced management efficiency.

First, the system reduced the weeding frequency from three times per month to once per quarter, substantially lowering manual labor input and costs. Next, the precision spraying module was effective in minimizing pesticide use, avoiding chemical residues and secondary soil contamination, thereby preserving the environment. Finally, the system’s remote monitoring and alert functions enabled farmers to track field conditions in real time, enhancing operational efficiency and safety.

In contrast to traditional approaches, though lower in initial cost and easier to operate, they are labor-intensive in the long run and impose greater environmental burdens.

5.3. System Limitations and Challenges

Despite its strong technical performance, the system still faces several challenges, such as high initial costs, issues with interface design, and connectivity problems.

Based on the result of the CBA (BCR <1), since the equipment is relatively expensive, the system requires a certain payback period before profitability is achieved. Further, some farmers, especially those who are less familiar with smartphone applications, find the system difficult to operate due to the interface (PEOU = 3.78 ± 0.74). Lastly, unstable internet connectivity in remote areas may affect the accuracy of real-time data transmission and alert notifications.

In line with this, further improvements in user experience, system stability, and accessibility are needed to enhance the practical applicability of the system in diverse agricultural settings.

5.4. Research Contributions and Social Implications

This study integrated the DSR with smart agricultural technologies to develop an innovative, practical, and sustainable solution for managing an invasive plant species (M. micrantha).

The developed system not only effectively slows the spread of the weed but also lowers the need for manual labor and pesticide dependency, achieving both ecological conservation and economic benefits. Furthermore, we provided a reproducible and integrative evaluation framework that combines the CEI, TAM, and CBA, which contributes to the establishment of standardized validation models for future smart agriculture studies.

Ultimately, by realizing human–machine collaboration and intelligent decision-making, this system holds great potential to serve as a sustainable development model for controlling invasive species in Taiwan’s farmlands and forestry.

6. Conclusion

By adopting the DSR methodology, this paper developed an intelligent control system that combines IoT and automatic control technologies to control the spread of an invasive plant species in Taiwan. The system comprises four major modules: environmental monitoring, spraying control, remote monitoring, and warning modules. Through the combination of sensor data transmission, cloud-based analytics, and mobile application monitoring, smart agricultural management and automated invasive plant control were achieved.

The system was tested at the Shan-Shang Forest Leisure Farm in Dahu, Miaoli County, Taiwan. The results showed that the system remained generally stable under various climatic conditions, and the environmental monitoring data were mostly accurate and reliable; however, some inaccuracies in data were observed during extreme weather conditions and unstable connectivity. Additionally, the automated spraying module was found to be effective in suppressing the spread of M. micrantha due to its precision. Finally, it was noted that the remote monitoring and alert functions resulted in real-time detection of anomalies, significantly reducing the need for manual field inspection.

Overall, the findings confirm the high feasibility of applying IoT technology to invasive plant management, combining ecological sustainability with operational convenience. The key findings of this study are as follows:

The developed system integrated IoT sensing, remote control, and automated spraying technologies, establishing a smart control framework centered on “Sensing – Decision – Execution.” It enables real-time environmental monitoring and autonomous control of weed management operations, reducing manual intervention while enhancing precision and efficiency.

- 2.

Effectiveness Verification

The results of the CEI demonstrated that the system improved weed control efficiency from 46% to 87% within six months, achieving a significant suppression effect. Further, the outcomes of TAM indicated positive user evaluations, with PU (4.15) and BI (4.22) suggesting that the farmers found the system valuable and can be used long-term. Moreover, the CBA revealed that although the BCR in the first year was less than 1 (0.15) due to the initial cost of the equipment, it increased to 1.6 in subsequent years, with a payback period of approximately 1.67 years; thus, the system has a strong medium- to long-term economic feasibility.

- 3.

Social and Environmental Impact

The system effectively reduced herbicide use and labor demand, promoting environmentally friendly and sustainable agricultural practices. Also, the collaboration with local young farmers strengthened industry–academia partnerships and community engagement, offering potential for broader policy implementation and regional promotion.

To summarize, this study successfully developed an intelligent invasive plant control system that integrates IoT technology, environmental sensing, and automated control. Through field testing, its technical reliability, economic viability, and user acceptance were verified, confirming its potential to effectively suppress M. micrantha growth while enhancing agricultural sustainability. Aside from offering an innovative solution to the M. micrantha problem, this research also laid a foundation for the advancement of smart agriculture and ecological conservation technologies in Taiwan.

References

- Araújo, S.O.; Peres, R.S.; Pian, L.B.; Lidon, F.; Ramalho, J.C.; Barata, J. Smart Agricultural System Using Proximal Sensing, Artificial Intelligence, and LoRa Technology: A Case Study in Vineyard Management. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 183593–183607. [CrossRef]

- Bahmutsky, S.; Grassauer, F.; Arulnathan, V.; Pelletier, N. A Review of Life Cycle Impacts and Costs of Precision Agriculture for Cultivation of Field Crops. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 347–362. [CrossRef]

- Benyezza, H.; Bouhedda, M.; Kara, R.; Rebouh, S. Smart Platform Based on IoT and WSN for Monitoring and Control of a Greenhouse in the Context of Precision Agriculture. Internet Things 2023, 23, 100830. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.C. Energy Saving and Sprinkling Efficiency of Sensor Networks in Irrigation Systems; Master’s Thesis, National Central University, Department of Communication Engineering: Taoyuan, Taiwan, 2016.

- Chen, C.H.; Chen, J.C.; Wang, T.H.; Wang, J.L.; Chao, Y.C. Biological Control of Mikania micrantha; In Proceedings of the Symposium on the Harm and Management of Mikania micrantha, Taipei, Taiwan, 2003.

- Chen, C.Z. Monitoring the Spatial Distribution of Mikania micrantha; Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan: Taipei, Taiwan, 2001; p. 29.

- Chen, Y.; Luo, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, M.; Huang, H. Study on RNAi-Based Herbicide for Mikania micrantha. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 30, e00625. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; Huang, H. MmNet: Identifying Mikania micrantha Kunth in the Wild via a Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Inf. Sci. 2020, 512, 1372–1384. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L. Spatial Distribution and Landscape Pattern of Mikania micrantha; Master’s Thesis, National Taipei University, Graduate Institute of Natural Resources and Environmental Management: Taipei, Taiwan, 2020.

- Cronk, C.B.; Fuller, J.L. Plant Invaders: The Threat to Natural Ecosystems; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1995; pp. 15–59.

- Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Hyperspectral Imaging for Identification of an Invasive Plant Mikania micrantha Kunth. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 626516. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y.; Peng, J.C.; Kuo, Y.H. The Spread and Monitoring of Mikania micrantha in Taiwan; In Proceedings of the Symposium on the Harm and Management of Mikania micrantha, Taipei, Taiwan, 2003.

- Huang, S.Y.; Yeh, S.C.; Peng, J.C. The Ecological Traits and Spread Monitoring of Mikania micrantha. Agric. Policy Agric. Trends 2004, 145. Available online: https://www.coa.gov.tw/ws.php?id=7564 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Huang, Z.L.; Cao, H.L.; Liang, X.D.; Yeh, W.H.; Feng, H.L.; Cai, C.X. Survival and Damage of Mikania micrantha in Different Habitats and Forest Environments. J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 2000, 8(2), 131–138.

- Jia, P.; Wang, J.; Liang, H.; Wu, Z.; Li, F.; Li, W. Replacement Control of Mikania micrantha in Orchards and Its Eco-Physiological Mechanism. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 1095946. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lin, Y.; Chang, C. Weed Warden: A Low-Cost Weed Detection Device Implemented with Spectral Triad Sensor for Agricultural Applications. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107019. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twins Technology in Agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 15(9), 903. [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.T.; Chiu, M.L. (Eds.) Greening the Countryside: A Guide to Common Plants in Rural Communities; Endemic Species Research Institute, Council of Agriculture: Nantou, Taiwan, 2006.

- Rajak, P.; Ganguly, A.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Internet of Things and Smart Sensors in Agriculture: Scopes and Challenges. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100776. [CrossRef]

- Sanyaolu, M.; Sadowski, A. The Role of Precision Agriculture Technologies in Enhancing Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2024, 16(15), 6668. [CrossRef]

- Soussi, A.; Zero, E.; Sacile, R.; Trinchero, D.; Fossa, M. Smart Sensors and Smart Data for Precision Agriculture: A Review. Sensors 2024, 24(8), 2647. [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Guo, W.; Ma, J.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, J.; You, L.; Li, Y. Predicting the Potential Distribution of the Invasive Weed Mikania micrantha and Its Biological Control Agent Puccinia spegazzinii under Climate Change. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 163, 112655. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Chen, J. Monitoring Technology of Mikania micrantha in Flowering Period Based on UAV Remote Sensing. J. Agric. Eng. Inform. 2020, 32(2), 56–63. Available online: https://www.aeeisp.com/nyjxxb/en/article/id/5edda045-9410-4125-b5c3-fa69a5120106.

- Wei, T.Y. Exploring the Spatial Distribution of Mikania micrantha Invasion Using GIS; Master’s Thesis, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Department of Forestry: Pingtung, Taiwan, 2003.

- Willis, M.; Zerbe, S.; Kuo, Y.L. Distribution and Ecological Range of the Alien Plant Species Mikania micrantha Kunth (Asteraceae) in Taiwan. J. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 31(4), 277–290.

- Xie, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, T. Vision-Based Weed Detection for Smart Agriculture Using Deep Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.03168. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Feng, H.; Ye, W.; Cao, H.; Deng, X.; Xu, K. An Investigation of the Effects of Environmental Factors on the Flowering and Seed Setting of Mikania micrantha HBK (Compositae). J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 2003, 11(2), 123–126.

- Yeo, M.L.; Keske, C.M. From Profitability to Trust: Factors Shaping Digital Agriculture Adoption. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 112233. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y. Identification and Biological Characteristics of Alternaria gossypina as a Promising Biocontrol Agent for the Control of Mikania micrantha. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 691. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Xu, S.; Ding, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, C.; He, Y. Exogenous Phytohormone Application and Transcriptome Analysis of Mikania micrantha Provides Insights for a Potential Control Strategy. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 174, 104818. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, H.; Chang, Q.; Mao, Q. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twins Technology in Agriculture. Agriculture 2025, 15(9), 903. [CrossRef]