1. Introduction

Several studies have highlighted the potential of virtual, augmented and mixed reality to create new ways of enjoying tourism, support destination marketing and promote memorable experiences (Li & Jiang, 2023; Pestek & Sarvan, 2021; Talwar et al., 2022), while recent reviews on customer/tourist experience emphasise the need to understand the tourist experience as a multidimensional phenomenon, co-created and strongly dependent on interpretative and cultural processes (Câmara et al., 2023; Ortiz et al., 2024; Rusu et al., 2023). At the same time, other studies show that immersive technologies can contribute to sustainability, accessibility, and the decentralisation of tourist flows, particularly in sensitive cultural and natural heritage sites (Bec et al., 2021; Gonçalves et al., 2022; Suanpang et al., 2022).

Tourists are increasingly seeking Mixed Reality (MR) experiences, and because this is a recent trend, there are still many opportunities to create value with these technologies to meet new customer needs (Bec et al., 2021). This virtual presence can help address issues related to destination capacity, accessibility, and destination conservation (Buhalis et al., 2019). Thus, virtual tours are potential tools for increasing tourism offerings and attracting more visitors to cultural destinations (Pantano & Corvello, 2014). The creation of a virtual world or the metaverse itself can help tourists to visit various tourist destinations of different types, such as natural attractions and museums that they would like to visit but are unable to do so in person (Suanpang et al., 2022).

By understanding the needs of its target audience and applying innovative techniques and ideas, the tourism industry can benefit as a whole and, above all, can deliver a more satisfying experience for visitors and a more profitable one for businesses (Kim et al., 2020). Baglieri and Consoli (2009) put forward the idea that tourism businesses can increase their competitive advantage and innovation in their products by creating virtual communities where the sharing of knowledge, interests and needs of their customers can be matched. For the use of MR in tourism to continue to gain ground, marketing teams must be able to meet customer needs by creating a unique service that adds value for visitors, so that they are inclined to return and recommend the service to others (Huang et al., 2016).

While it is important for the business world to learn more about the profitability of MR and its contribution to the tourist experience, from an academic perspective, Bec et al. (2021) point out that there are gaps that can be addressed in new research, with a view to expanding the academic dialogue on the applications of virtual tourism and mixed realities as a viable solution for tourist destinations.

Thus, this study aims to contribute to the theory and practice of the use of mixed realities in tourism, focusing on two main aspects. At the theoretical level, it is expected to deepen comprehension of the impact of innovations such as mixed realities, which include virtual reality and augmented reality, on the tourism sector, identifying the components that promote their adoption by visitors/potential visitors and highlighting the role of new technologies in innovation and the creation of unique experiences for visitors. On a practical level, the results of this study will provide insights for tourism managers and professionals on how to apply mixed realities to attract visitors and promote innovation and sustainability in destinations. Mixed realities can reduce pressure on natural and cultural resources by offering alternative and complementary digital experiences. In addition, the study may guide investments aimed at integrating innovative technologies into tourism, strengthening the competitiveness of destinations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality and Mixed Reality

There are numerous concepts of Virtual Reality (VR), but the term can be summarised based on Tori et al. (2006) as a sophisticated interface for applications, allowing users to explore and interact in real time in a 3D environment with multisensory devices. More recently, Kadagidze and Ugrelidze (2023, p. 477) define VR as “computer-generated simulation of a three-dimensional environment that can be interacted with in a seemingly real or physical way”. The use of VR can create authentic and interactive experiences that add value for visitors and give them the opportunity to access cultural content through this medium (Li et al., 2023).

According to Saneinia et al. (2022), VR has opened a new path full of possibilities and different perspectives, which may prove important for the future of tourism. VR experiences in the sector attract visitors who want to explore and revisit destinations (Jorge et al., 2023). Various museum experiences created with VR (games and interactive 3D heritage, etc.) provide visitors with an enriching cultural experience (Li et al., 2023).

In turn, Augmented Reality (AR) “involves overlaying digital information onto the real-world environment, allowing users to see both the physical and digital worlds simultaneously” (Kadagidze, 2023 & Ugrelidze, p. 477). AR in tourism is recognised as a key technological aspect for the sustainable development of the industry (Li & Jiang, 2023), enhancing the long-term appeal of a tourist destination (Jung et al., 2015).

A VR and AR are considered tools with high potential, as they have the capacity to boost sustainability in tourism through their immersive and interactive experiences (Rane et al., 2023) and can be differentiating factors by providing innovative and unique experiences to visitors. Constant investment in the design and implementation of innovative experiences based on VR and AR will enable destinations to establish a competitive advantage that will attract new tourists and more economic and social investment (Martins et al., 2020).

Despite the positive aspects, there are intrinsic challenges and limitations, such as cost, accessibility, ethical reasons, and the need for physical experience (Ugrelidze & Kadagidze, 2023). Introducing VR and AR in a cultural tourist destination poses complex challenges that require a symbiosis between technological innovation and infrastructure (Gatelier et al., 2022). The use of VR and AR in a project to digitise a tourist destination is not intended to reduce demand, but rather to increase supply, giving visitors two completely different and complementary alternatives for visiting an attraction. This creates two target audiences (one focused on digital and the other on in-person experiences) that can be a viable alternative to combat mass tourism at a destination (Frey & Briviba, 2021). According to Dueholm and Smed (2014), the authenticity of a tourist destination exists both in person and in the virtual environment; technologies bring more versatility to cultural tourist attractions, without taking away from the magic of a visit in person.

Accessibility to the surface is as important as accessibility to underwater tourist attractions. VR and AR systems increase accessibility for tourists who enjoy diving and exploring, but also for those who do not dive. The implementation of a complete VR and AR system makes it possible to dive into various tourist destinations using this technology, contributing to the continuous improvement of the scope of tourist experiences (Bruno et al., 2020). Personalised experiences allow visitors to overcome difficulties in various aspects inherent to a visit, as they are planned from start to finish considering the motivations and characteristics of each customer, which contributes to individual satisfaction.

The first authors to define Mixed Realities (MR), Milgram and Kishino (1994), indicated that the best way to understand the concept was to think of a world where the real and the virtual are together in a single dimension. According to Buhalis and Karatay (2022), MR combines the two previous concepts (real and virtual), thus contributing to a realistic increase in users' perception of the real world. MR allows for the recreation of tourist environments that are difficult to physically and in-person, which helps in the accessibility of different destinations and audiences (Sanchez Ruiz et al. 2020). Siddiqui et al. (2022) classify the virtual experience – VR/AR/MR – as non-immersive, semi-immersive, and fully immersive. The experiences are very engaging, sometimes making it virtually impossible to distinguish physical objects from virtual ones, thus providing a unique experience between what is real and what is digital. MR merges the virtual world with the real world, making it possible to distinguish between content that belongs to reality and content that belongs to the virtual world (Kunnen et al., 2020).

MR could be the key to the tourism sector, as new generations already live a life that integrates virtual and real aspects. There is a path laid out for the future of tourism experiences, more precisely related to cultural experiences, through dynamic interaction with real artefacts represented virtually, digital animations and much more through MR. This technology has the potential and power to leverage the future of diverse experiences, scattered across the different fields where innovation and tourism operate (Buhalis & Karatay 2022).

2.2. Tourism Content

Kuching (2023) argues that today's world is completely digitalised and accessible to all and, as a result, has evolved with the fusion of the real and virtual worlds. In turn, Mendonça et al. (2021) highlight that the processing capacity of electronic devices has increased, allowing for the development of new forms of communication, which are present in multimedia content, featuring three-dimensional (3D) environments, as well as VR.

For a destination to be smart, Buhalis et al. (2019) highlight the need to develop a customer-based ecosystem that provides personalised and optimised experiences. This will enable sustained competitive advantage and improve the quality of life for tourists and residents. For this to be possible, the authors consider that a set of factors must be in place, highlighting technology (including AR, VR and MR), innovation, human capital and leadership.

In the tourism sector, the applicability of RM in creating storytelling for a tourist destination can provide visitors with an optimised experience that generates more empathy, connection and entertainment (Mohd et al., 2023). Destinations that are experiencing serious sustainability problems due to overcrowding and poor management of their resources can gain new momentum by using these experiences (Bec et al., 2021). The creation of a 3D virtual world applied to a tourist destination can help attract new visitors and potential investors (Huang et al., 2016). Making this content available online can also be useful for planning trips and positively influencing consumer behaviour (Huang et al., 2016).

2.3. Tourist Experience

Tourist experience is important for understanding tourist behaviour, developing tourism products and destination marketing strategies. Several authors highlight its multidimensional, subjective and dynamic nature, involving emotional, cognitive, sensory, relational and behavioural aspects (Câmara et al., 2023; Godovykh and Tasci, 2020; Ortiz et al., 2024; Rusu et al., 2023).

The tourist experience is the totality of the tourist's interactions and responses to products, services and environments before, during and after the trip, influenced by individual, cultural and contextual factors (Godovykh and Tasci, 2020; Ortiz et al., 2024; Rusu et al., 2023). Thus, the tourist experience can be seen both as a subjective process of attributing meaning and as the result of external stimuli, such as activities, physical environment, and social interactions (Câmara et al., 2023; Godovykh and Tasci, 2020). In turn, the tourist experience in VR provides perceptions of novelty, reality, originality, exceptionality, or uniqueness of experiences, which should influence the tourist's well-being, as well-being has an impact on the tourist's intention to use technologies (Kim et al., 2020).

There are several instruments and methods for evaluating the tourist experience, including memorable experience scales, satisfaction and well-being questionnaires, and qualitative approaches to capture the depth and uniqueness of experiences (Câmara et al., 2023; Godovykh and Tasci, 2020; Ortiz et al., 2024; Rusu et al., 2023). The literature highlights the need for holistic assessments that are adapted to the cultural context and type of tourism analysed (Câmara et al., 2023; Ortiz et al., 2024; Rusu et al., 2023).

3. Development of Hypotheses and Conceptual Framework

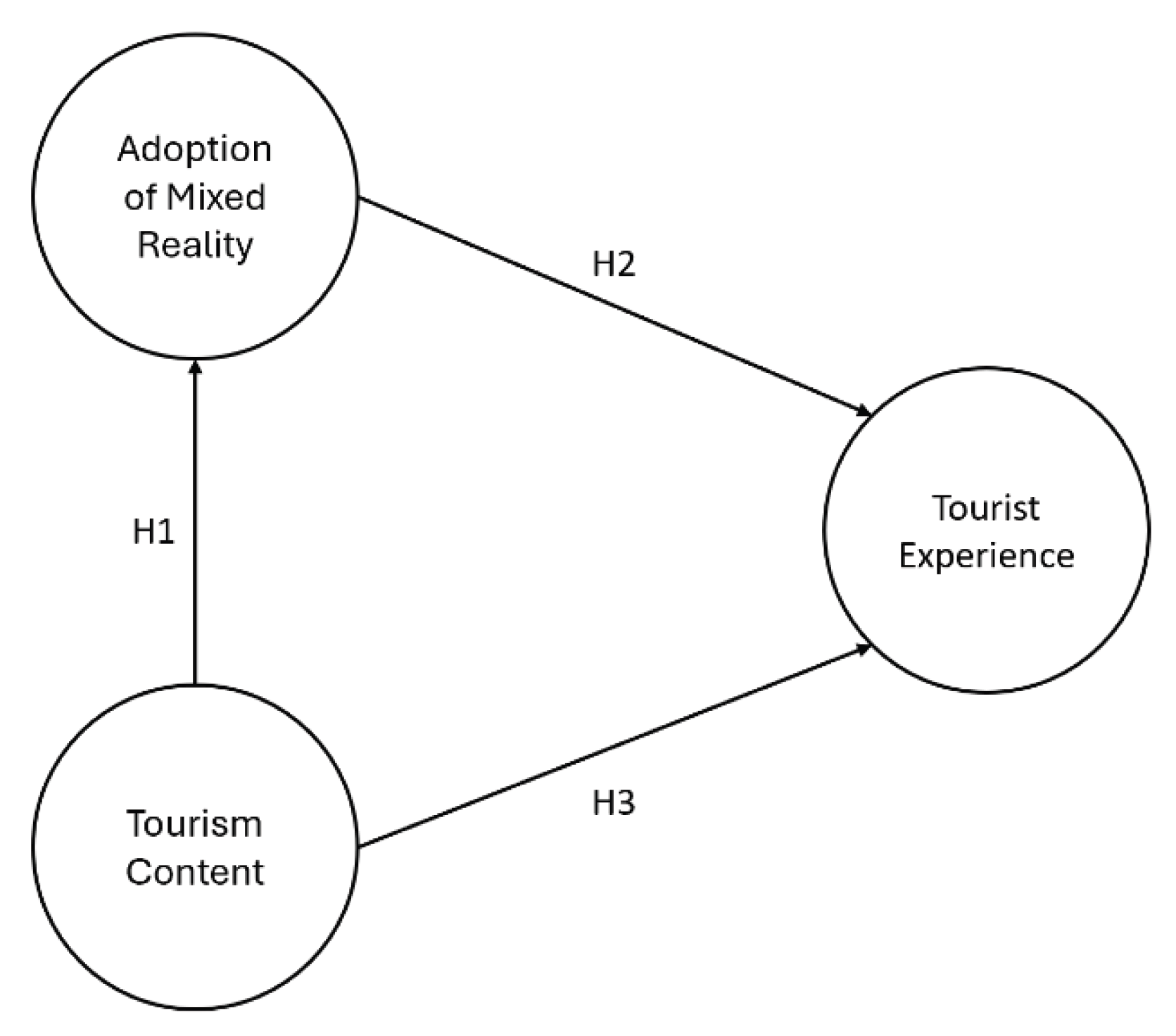

The literature review allowed for the formulation of three research hypotheses, which seek to discern relationships between the constructs “Tourism Content”, “Adoption of Mixed Reality” and “Tourist Experience”:

H1: Tourism content influences the adoption of mixed reality by tourists.

H2: The adoption of mixed reality by tourists enhances the tourist experience.

H3: Tourism content contributes to the tourist experience.

Based on the hypotheses formulated, the conceptual model is presented in

Figure 1.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Nature of the Study and Methodological Approach

This study falls within the quantitative research paradigm, adopting a positivist approach that aims to define causes and effects between variables and test previously formulated hypotheses. The research focuses on understanding the factors that influence the use of mixed reality technologies in the context of the tourism sector, seeking to contribute to the existing body of knowledge through the empirical validation of a structured theoretical model.

In terms of its purpose, this study is characterised as descriptive explanatory. The descriptive component allows the profile of users to be characterised, while the explanatory dimension enables the analysis of causal relationships between theoretical constructs, allowing the determinants of the behaviour of use of this emerging technology to be identified.

From a temporal point of view, the research is cross-sectional, as the data were collected at a single point in time, providing a snapshot of the participants' perceptions and behaviours regarding the use of mixed reality in tourism contexts.

The methodological strategy adopted is based on the collection of primary data through a structured online questionnaire, developed specifically to operationalise the theoretical constructs underlying the research model. This methodological choice is justified by the need to achieve a representative and geographically dispersed sample, maximising efficiency in data collection and allowing for a higher response rate.

For data processing and analysis, we used structural equation modelling approach, supported by PLS-SEM (Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling. There are several reasons for choosing this methodological technique. Firstly, PLS-SEM is particularly suitable for exploratory and confirmatory research, allowing complex models that include multiple relationships between latent variables to be tested. Secondly, this technique is robust in the face of less restrictive assumptions regarding data distribution, as it does not require multivariate normality. Additionally, PLS-SEM allows effective work with moderate-sized samples and offers high flexibility in modelling reflective and formative constructs.

The analysis using PLS-SEM is carried out in two fundamental stages: (i) the evaluation of the measurement model, which allows the reliability and validity of the constructs to be verified; and (ii) the evaluation of the structural model, which makes it possible to test the hypotheses formulated and analyse the causal relationships between the latent variables. This analytical procedure ensures the scientific rigour necessary for the empirical validation of the proposed theoretical model and the formulation of well-founded conclusions on the use of mixed reality in the tourism sector.

4.2. Sampling and Data Collection

Non-probability sampling was used for convenience, targeting individuals with actual or potential contact with MR applications in tourism contexts (visitors, residents, professionals and/or students with MR previous experience).

The data collecting tool was designed after reviewing the scientific literature presented, integrating validated scales adapted to the specific context of mixed reality in tourism (

Table 1). The questionnaire includes items measured using Likert scales, allowing the perceptions, attitudes and behavioural intentions of respondents to be captured in a standardised and quantifiable manner.

The survey was conducted within a limited period, with informed consent and explicit eligibility criteria (legal age, understanding of the language, contact with MR).

5. Results

5.1. Characterisation and Description of the Sample

The sample consists of 104 valid responses, whose characteristics are presented in

Table 2 and reveals a slight predominance of males, with 57.69% of individuals being male and 42.31% female. In terms of age distribution, the 18–29 age group predominates (64.42%), followed by the 40–49 age group (15.38%), 50 years or older (11.54%) and 30–39 years (8.65%). In terms of education, most respondents had secondary education (35.58%) or higher education (41.35%), while 15.38% had postgraduate qualifications and 7.69% had only basic education. This distribution indicates a medium to high educational profile, consistent with samples obtained in urban and digitally active contexts.

Overall, the sample is characterised by a young, moderately educated profile with a slight male predominance, which should be considered when interpreting the results and generalising the conclusions, given the potential limitation of population representativeness.

5.2. Reflexive Constructs

The first step was to verify the reliability of the indicators (Indicator Reliability), that is, to verify whether each indicator contributes significantly to the construct. This was done by analysing the outer loadings, whose value above 0.70 (Hair et al., 2022) is generally considered ideal, indicating that the indicator shares more than 50% of its variance with the construct. All values obtained (

Table 3) are above 0.86, indicating that all indicators contribute significantly to the “Tourist Experience” construct.

In reflective constructs, as the focus is on internal consistency and validity, the objective is to ensure that the indicators are good reflections of the construct. Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability were used to assess the internal consistency of all indicators together, while average variance extracted (AVE) was used to analyse convergent validity.

The results presented in

Table 4 show that the ‘Tourist Experience’ construct has high internal consistency and composite reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha value (0.852) exceeds the minimum threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2022), indicating homogeneity among the items in the construct. In turn, composite reliability (rho_a=0.852; rho_c=0.910) falls within the recommended range (0.70–0.95), which reinforces the robustness of the measurement without suggesting excessive redundancy between indicators. In addition, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE=0.771) value reveals that the construct explains, on average, 77.1% of the variance of its indicators, amply exceeding the minimum criterion of 0.50 (Hair et al., 2022). This result confirms the strong convergent validity and indicates that the indicators adequately represent the theoretical concept of “Tourist Experience’.

Table 5 presents the results of the Fornell–Larcker criterion, used to assess the discriminant validity between constructs. According to this criterion, the square root of the AVE (values on the main diagonal) must be greater than the correlations between constructs (values off the diagonal). The square root of the AVE of the ‘Tourist Experience’ construct (√AVE=0.878) is greater than its correlations with ‘Adoption of Mixed Reality’ (0.659) and Tourism Content (0.663). Thus, it is confirmed that the construct shares more variance with its indicators than with those of other constructs, ensuring discriminant validity. The values obtained meet the Fornell–Larcker criterion, showing that the constructs are distinct and measure different theoretical concepts in the measurement model.

5.3. Formative Constructs

To assess the collinearity of the indicators associated with the formative constructs, the Outer VIF Values were analysed. The results obtained from the outer VIF (see

Table 6) revealed values ranging from 1.424 to 2.257, all significantly below the reference thresholds of 3.3 (most demanding value) (Hair et al., 2022). It was concluded that there is no collinearity between the indicators, ensuring that each variable contributes uniquely to the construct.

Regarding external weights (

Table 7), all indicators presented positive and statistically significant values (

p<0.001), demonstrating their relevance in explaining the constructs. In the case of the construct ‘Adoption of Mixed Reality’, both indicators (AR1 and AR2) exhibited significant weights (0.534 and 0.603, respectively), with AR2 contributing most to the construct. For the construct “Tourism Content”, it was observed that both indicators (TC1=0.393; TC2=0.691) are statistically relevant, although TC2 makes a more significant contribution, reflecting greater substantive importance in the composition of the construct.

The analysis of outer loadings (

Table 8) reveals high and statistically significant values (

p<0.001) for all indicators, ranging from 0.861 to 0.957. The results show a strong link between each indicator and its construct, confirming the convergent validity of the measurement model. In accordance with the recommendations of Hair et al. (2022), all values greatly exceed the minimum threshold of 0.70, indicating that the indicators explain a substantial proportion of the variance in the latent constructs. The bootstrap sample means are practically identical to the original estimates and the standard deviations are low, suggesting high stability of the estimates. In addition, all indicators reveal very high t-values (between 14.572 and 33.338), confirming the statistical significance of the loadings. Taken together, these results robustly support the individual reliability of the items and the quality of the measurement model, with no justification for removing any indicator. Thus, it is concluded that the constructs “Adoption of Mixed Reality” and “Tourism Content” exhibit high internal consistency and metric adequacy.

5.4. Assessment of the Validity of the Structural Model

To assess the validity of the structural model, we began by evaluating collinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) indicator. As show in

Table 9, the internal VIF values range from 1.000 to 2.106, all well below the critical limit of 3. It can be concluded that there are no collinearity problems between the predictor constructs and that the structural model demonstrates stability and consistency in the relationships between latent variables, reinforcing the validity of the estimated coefficients.

The results in

Table 10 show that the model has good explanatory power with moderate

R² values for both endogenous constructs. Thus, approximately half of the variance in “Adoption of Mixed Reality” and “Tourist Experience” is explained by the respective predictors, which confirms the overall adequacy of the structural model and the consistency of the proposed theoretical relationships.

Table 11, referring to

Q² values, shows that the model has overall predictive relevance for all constructs, since all coefficients are positive and greater than 0.15 (Hair et al., 2022). The construct “Adoption of Mixed Reality” obtained a

Q² of 0.293, indicating moderate predictive relevance, while “Tourism Content” reached 0.436, reflecting strong predictive capacity. In turn, “Tourist Experience” had the highest value (0.521), demonstrating very high predictive relevance and confirming the robustness of the model in explaining the tourist experience. In summary, the results suggest that the proposed model is effective in predicting the constructs analysed, with particular emphasis on tourist content and tourist experience.

The effect size (see

Table 12) indicates that ‘Tourism Content’ has a very high incremental impact on ‘Adoption of mixed reality’ (

f²=1.106), while both ‘Adoption of Mixed Reality’ (

f²=0.136) and ‘Tourism Content’ (

f²=0.148) have small-to-medium effects on ‘Tourist Experience’. Overall, the results confirm the incremental relevance of the predictors, with emphasis on the dominant role of ‘Tourism Content’ in explaining the adoption of mixed realities.

The estimation reveals positive and statistically significant direct effects between the constructs (

Table 13): Tourism Content → Adoption of Mixed Reality presented the highest coefficient (β=0.725;

t=14.826;

p<0.001), evidencing a strong influence of tourism content on the adoption of mixed reality. There is also a direct impact of Adoption of Mixed Reality → Tourist Experience (β=0.375;

t=3.546;

p<0.001) and Tourism Content → Tourist Experience (β=0.392;

t=3.212;

p=0.001), both of moderate magnitude.

The analysis of the indirect effect (

Table 14) confirms that the relationship between ‘Tourism Content’ and ‘Tourist Experience’ is significantly mediated by ‘Adoption of Mixed Reality’ (β=0.272;

t=3.242;

p=0.001). The significance of the indirect effect, combined with the persistence of the direct effect, indicates the existence of complementary partial mediation, since both effects have the same positive sign. The calculation of VAF (Variance Accounted For), approximately 41%, reinforces this result, suggesting that about two-fifths of the total impact of Tourism Content on Tourist Experience is transmitted through Adoption of Mixed Reality.

Together, these results demonstrate that richer tourism content promotes the adoption of mixed realities, which in turn enhances tourism experience, with a positive and significant direct effect of Tourism Content on Tourist Experience also coexisting. Thus, the adoption of mixed reality acts as a relevant mediating mechanism, reinforcing the link between the quality of tourism content and the overall perception of the visitor experience.

As can be seen in

Table 15, the model shows good overall fit (SRMR=0.047) and acceptable fit according to the NFI (0.909). The d_ULS and d_G discrepancies are small, reinforcing the adequacy of the model. Overall, the metrics indicate that the estimated model is consistent with the data, with no loss of fit compared to the saturated model.

6. Discussion

The results obtained contribute to the emerging literature on the application of RM technologies in tourism, providing empirical evidence that supports the theoretical propositions of authors such as Buhalis and Karatay (2022), Bec et al. (2021) and Kim et al. (2020). From a practical point of view, the results offer clear guidance to tourism destination managers on the importance of integrated investments in quality content and facilitating technological adoption, with the potential to simultaneously promote innovation, sustainability and competitiveness of destinations.

The validation of the conceptual model confirms that the perception of clear, relevant and informationally rich content is the main driver of user adoption of these technologies. In theoretical terms, this evidence is consistent with classical frameworks on MR as a continuum between real and virtual environments (Milgram & Kishino, 1994; Tori et al., 2006) and with approaches that emphasise that technology alone is insufficient to generate value without a layer of meaning anchored in content. Studies such as those by Jung et al. (2015), Huang et al. (2016) and Pantano and Corvello (2014) had already shown, in AR/VR contexts, that perceived usefulness, gratification and recommendation strongly depend on the quality and relevance of the information and narrative provided. The results now obtained reinforce this conclusion by quantifying that content is a much more important antecedent than any other variable in the RM adoption process.

This central role of content is consistent with the literature discussing collaborative innovation and the design of digital services in tourism. Baglieri and Consoli (2009) highlight the importance of virtual communities in the co-creation of value and knowledge; Mendonça et al. (2021) show how collaborative platforms can leverage the creation and integration of VR content in the tourism sector; Chen and Chen (2024) demonstrate that computer-assisted design of cultural tourism products, when service-oriented, requires a strong content design component; and Gatelier et al. (2022) propose a methodology for innovating business models for digital interpretation experiences in heritage attractions. The present study converges with these perspectives by indicating that the adoption of MR depends, to a large extent, on content curation and design processes, rather than on a purely technological logic, bringing the discussion closer to the dynamics of collaborative innovation and user-centred experience design.

Regarding the relationship between the adoption of MR and the tourist experience, the results show a positive and statistically significant effect, with a small to moderate magnitude, suggesting that MR contributes to the experience being perceived as more enjoyable, fun, and rewarding, but is only one of the factors that shape it. This finding is consistent with the literature that associates immersive technologies with the creation of memorable and hedonic experiences (Jorge et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2020; Li & Jiang, 2023; Sanchez Ruiz et al., 2020), as well as with the synthesis by Li et al. (2023), which identifies interactivity, immersion, and engagement as central dimensions of the experience in museum and digital heritage contexts. However, the moderate magnitude of the effect contrasts with some studies in controlled VR environments – such as Kim et al. (2020) or Jorge et al. (2023) – where the impact of technology on the experience tends to be more pronounced, probably because technology is at the core of the experience itself. In the present case, MR appears as a complement to the visit or contact with the destination, which helps to explain a positive contribution, but one shared with other determinants already identified in the literature on tourist experience, namely environmental, social and cultural factors (Câmara et al., 2023; Godovykh & Tasci, 2020; Ortiz et al., 2024; Rusu et al., 2023).

A particularly relevant contribution of this study lies in identifying the dual role of tourism content: on the one hand, as a direct determinant of the experience, and on the other, as a precursor to the adoption of RM, which in turn influences the experience. The direct effect of content on the experience, similar in magnitude to that of the adoption of RM, shows that the way information is structured, clarified and narrated impacts the overall evaluation of the visit, even when technology is used little or not at all. This evidence is in line with the body of literature on meaningful experiences and meaning construction in tourism, which emphasises the role of narratives and interpretive devices in attributing meaning, emotional connection to place, and memorability (Câmara et al., 2023; Dueholm & Smed, 2014; Gonçalves et al., 2022). At the same time, the significant indirect effect – translated into partial mediation – reinforces that better quality content enhances the adoption of RM, which amplifies the experience by providing more immersive, interactive, and personalised ways of accessing that same information, which converges with the conclusions of Siddiqui et al. (2022), Kuching (2023) and Kadagidze and Ugrelidze (2023) on the role of AR/VR/MR technologies in intensifying visitor immersion and participation

This partial mediation also complements the debate on authenticity and technological mediation. Studies on perceived authenticity in heritage contexts, such as Dueholm and Smed (2014), have emphasised that interpretation and narrative framing decisively condition the perception of authenticity, either reinforcing or diluting it. By showing that content has a direct positive effect on the experience, even after controlling for the adoption of RM, the present study suggests that immersive technologies do not replace the need for careful interpretative work; rather, they function as an extension of mediation and storytelling practices already described in the heritage and cultural tourism literature (Bruno et al., 2020; Buhalis & Karatay, 2022; Gatelier et al., 2022). Thus, the results support the idea that MR should be conceived as an additional layer of interpretation – and not just as a technological spectacle – capable of reinforcing meanings, promoting more accessible readings of complex content, and creating experiences more aligned with expectations of subjective authenticity.

Another dimension that brings together the results of recent literature concerns sustainability and the management of pressures on cultural destinations. The inclusion, in the adoption of RM, of items associated with innovation and sustainability is echoed in works that defend VR/MR as instruments for ‘second chance tourism’ (Bec et al., 2021), for the sustainable enhancement of underwater heritage (Bruno et al., 2020) or for the reduction of physical travel in the form of virtual reality tourism (Pestek & Sarvan, 2021; Talwar et al., 2022). At the same time, authors such as Frey and Briviba (2021) and Rane et al. (2023) relate digitalisation – including AR/VR – to strategies for mitigating overtourism, improving flow management and promoting more sustainable tourism. The positive relationship between MR adoption and tourist experience observed in this study suggests that, when well-grounded in content, MR solutions can simultaneously enhance the quality of the experience and offer alternatives or complements to physical visits, aligning with proposals for smart tourism cities and the tourism metaverse (Siddiqui et al., 2022; Suanpang et al., 2022). Although behavioural or environmental variables were not analysed, these results reinforce the potential of MR as a policy and destination management tool, in line with concerns already identified in contexts such as rural tourism and seasonality (Lusa, 2023) and the safeguarding of intangible heritage (Gonçalves et al., 2022).

The socio-demographic profile of the sample – predominantly individuals aged between 18 and 29 – also helps to interpret the openness to adopting MR and its positive impact on the experience. Several studies indicate that Generation Z and younger audiences demonstrate a high level of familiarity and comfort with immersive environments and digital platforms, which increases the likelihood of accepting MR in tourism (Buhalis & Karatay, 2022; Saneinia et al., 2022). The results of this study seem consistent with this framework: the adoption of MR emerges as a relevant factor for the experience, but not an exclusive one, suggesting that even digitally competent segments simultaneously value content and physical context, corroborating the idea that MR is perceived as a complement to and not a substitute for in-person visits (Pestek & Sarvan, 2021; Talwar et al., 2022). This finding points to the need for caution in generalising to segments less familiar with technology, such as senior tourists or audiences with lower digital literacy, which the literature identifies as facing specific challenges when it comes to immersive solutions (Rusu et al., 2023; Siddiqui et al., 2022).

7. Conclusions

The study shows that the quality of tourism content plays a central role both in the adoption of mixed reality and in the perceived tourism experience, with MR being an important mediating mechanism that enhances the impact of this content. These findings reinforce the need to think about technological innovation in tourism in an integrated way, linking technology, content and experience to promote more sustainable, attractive and competitive destinations.

In conclusion, the results demonstrate that content is not an accessory element, but the main explanatory factor for the adoption of MR and a direct determinant of the tourist experience. MR thus emerges as an extension of this content, amplifying its impact by providing more immersive, interactive and personalised ways of engaging with the destination. This evidence helps to consolidate the idea that the value of immersive technologies in tourism depends largely on the quality and relevance of the content they convey.

From a theoretical perspective, the study contributes to the literature by integrating, in a single model, tourism content, MR adoption and tourism experience, highlighting direct and mediated relationships between these constructs. In doing so, it brings together research traditions that have often been treated separately: on the one hand, the acceptance and use of immersive technologies; on the other, the analysis of meaningful tourism experiences and their relationship with storytelling, interpretation, and authenticity. The empirical demonstration that content has a direct effect on the experience, even in the presence of MR, reinforces the role of interpretive mediation practices as a structuring axis of the experience, confirming that technology should be conceived as a complement to, rather than a substitute for, the visitor's relationship with places.

On a practical level, the results offer clear clues for public decision-makers, destination managers and tourism organisations. The priority should not lie solely in the acquisition of hardware or the development of platforms, but in the definition of strategies for curating, designing and updating content, aligned with the characteristics of the target segments and with sustainability objectives. MR projects that do not incorporate a deep reflection on what narratives they intend to construct, what messages they wish to convey, and what types of engagement they want to stimulate run the risk of becoming mere technological exercises, with reduced impact on the experience and competitiveness of destinations.

Although the model is methodologically and theoretically robust, some limitations should be recognised, offering clues for future work. The sample is non-probabilistic, with a predominance of young individuals with medium to high levels of education. This limits the generalisation of the results to other segments (e.g. senior tourists or audiences with lower digital literacy). Future studies may use probabilistic or stratified samples, comparing different generational segments and technological literacy profiles.

Transversal studies do not capture the evolution of perceptions about RM over time. (before, during, and after the visit). Longitudinal investigations could track the effective use of MR in real visit contexts, assessing impacts on memorable experiences, intention to revisit, and recommendation.

The model focuses on three central constructs (content, MR adoption, and experience), not including other potentially relevant variables such as overall satisfaction, well-being, behavioural intention, perception of authenticity, or technological risk. Subsequent studies could extend the model by incorporating these dimensions and exploring more complex mediations and moderations.

The study treats MR in tourism in a relatively aggregated manner, without differentiating between types of destinations (natural, urban, cultural, underwater, etc.) or between different degrees of immersion (non-immersive, semi-immersive, fully immersive). Future research may compare different VR contexts and formats, assessing whether the role of content and adoption remains the same or varies depending on the type of experience and the tourism environment.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, I.O.G. and L.M.S.; methodology, I.O.G, L.M.S., B.B.S. and J.D.S.; software, J.D.S.; validation, I.O.G, L.M.S., B.B.S. and J.D.S.; formal analysis, I.O.G., L.M.S. and J.D.S; investigation, I.O.G, L.M.S., B.B.S. and J.D.S.; resources, I.O.G, L.M.S., B.B.S. and J.D.S.; data curation, I.O.G. and L.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.O.G., L.M.S. and J.D.S.; writing—review and editing, L.M.S., B.B.S. and J.D.S.; visualization, I.O.G, L.M.S., B.B.S. and J.D.S.; supervision, L.M.S.; project administration, J.D.S.; funding acquisition, J.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it involved an anonymous and voluntary online survey of adults without sensitive data, interventions, or vulnerable populations. The study complied with Portuguese legislation (Decree-Law No. 80/2018), the EU GDPR, and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be requested to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baglieri, D., & Consoli, R. (2009). Collaborative innovation in tourism: Managing virtual communities. TQM Journal, 21(4), 353–364. [CrossRef]

- Bec, A., Moyle, B., Schaffer, V., & Timms, K. (2021). Virtual reality and mixed reality for second chance tourism. Tourism Management, 83(November 2020), 104256. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F., Ricca, M., Lagudi, A., Kalamara, P., Manglis, A., Fourkiotou, A., Papadopoulou, D., & Veneti, A. (2020). Digital technologies for the sustainable development of the accessible underwater cultural heritage sites. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 8(11), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Karatay, N. (2022). Mixed Reality (MR) for Generation Z in Cultural Heritage Tourism Towards Metaverse. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2022 (pp. 16-27). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., Harwood, T., Bogicevic, V., Viglia, G., Beldona, S., & Hofacker, C. (2019). Technological disruptions in services: lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Service Management, 30(4), 484–506. [CrossRef]

- Câmara, E., Pocinho, M., Agapito, D., & de Jesus, S. N. (2023). Meaningful experiences in tourism: A systematic review of psychological constructs. European Journal of Tourism Research, 34, 3403-3403. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., & Chen, J. (2024). Innovation of Computer Aided Design of Tourism Cultural Products with Service Design Concept. Computer-Aided Design and Applications, 21(S12), 220–235. [CrossRef]

- Dueholm, J., & Smed, K. M. (2014). Heritage authenticities – A case study of authenticity perceptions at a Danish heritage site. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9(4), 285–298. [CrossRef]

- Frey, B. S., & Briviba, A. (2021). A policy proposal to deal with excessive cultural tourism. European Planning Studies, 29(4), 601–618. [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M., & Tasci, A. D. (2020). Customer experience in tourism: A review of definitions, components, and measurements. Tourism management perspectives, 35, 100694. [CrossRef]

- Gatelier, E., Ross, D., Phillips, L., & Suquet, J. B. (2022). A business model innovation methodology for implementing digital interpretation experiences in European cultural heritage attractions. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 17(4), 391-408. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A. R., Dorsch, L. L. P., & Figueiredo, M. (2022). Digital Tourism: An Alternative View on Cultural Intangible Heritage and Sustainability in Tavira, Portugal. Sustainability, 14(5), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Huang, Y., Backman, K., Backman, S., & Chang, L. (2016). Exploring the Implications of Virtual Reality Technology in Tourism Marketing: An Integrated Research Framework. International Journal of Tourism Research, 116–128. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Ruiz, J., Larrea Silva, J., & Caisachana Torres, D. (2020). The Augmented reality and virtual reality as a tool to create tourist experiences. Iberian Journal of Information Systems and Technologies (RISTI), E31, 87–96.

- Jorge, F., Sousa, N., Losada, N., Teixeira, M. S., Alén, E., Melo, M., & Bessa, M. (2023). Can Virtual Reality be used to create memorable tourist experiences to influence the future intentions of wine tourists? Journal of Tourism and Development, 43, 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Kadagidze, L., & Ugrelidze, E. (2023, May). Virtual and augmented reality in adventure tourism: A review of applications and future prospects. In VIII International New York Conference on Evolving Trends in Interdisciplinary Research and Practices (pp. 476-484).

- Kim, M. J., Lee, C. K., & Preis, M. W. (2020). The impact of innovation and gratification on authentic experience, subjective well-being, and behavioral intention in tourism virtual reality: The moderating role of technology readiness. Telematics and Informatics, 49(January), 101349. [CrossRef]

- Kuching, S. (2023). A Framework for Museum Transformation Using AR-VR Technologies to Support Tourism. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Applied Science (Ijrias), VIII(I January 2023), 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Kunnen, S., Adamenko, D., Pluhnau, R., Loibl, A., & Nagarajah, A. (2020). System-based concept for a mixed reality supported maintenance phase of an industrial plant. Procedia CIRP, 91, 15–20. [CrossRef]

- Jung, T., Chung, N., & Leue, M. C. (2015). The determinants of recommendations to use augmented reality technologies: The case of a Korean theme park. Tourism Management, 49, 75–86. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Wider, W., Ochiai, Y., & Fauzi, M. A. (2023). A bibliometric analysis of immersive technology in museum exhibitions: exploring user experience. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 4(September), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., & Jiang, S. (2023). The Technology Acceptance on AR Memorable Tourism Experience—The Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability, 15(18), 13349. [CrossRef]

- Lusa. (2023). Sazonalidade é um problema com “peso muito grande” no turismo rural. Turismo. https://eco.sapo.pt/2023/02/10/sazonalidade-e-um-problema-com-peso-muito-grande-no-turismo-rural/.

- Martins, J., Gonçalves, R., Au-Yong-Oliveira, M., Moreira, F., & Branco, F. (2020). Qualitative analysis of virtual reality adoption by tourism operators in low-density regions. IET Software, 14(6), 684–692. [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, V., Cunha, C., Morais, E., & Gomes, J. (2021). Alavancar a criação e integração de conteúdos de Realidade Virtual através de uma plataforma colaborativa: o caso do sector do turismo. RISTI - Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação, (E46), 545–556.

- Milgram, P., & Kishino, F. (1994). A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays. IEICE Transactions on Information Systems, 77(12), 1321-1329.

- Mohd, C. K. N. C. K., Shahbodin, F., Sedek, M., Zakaria, T. T., Anggrawan, A., & Kasim, H. M. (2023). Unveiling the Potential of Mixed Reality: Opportunities, Challenges and Future Prospects. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 101(20), 6650–6662.

- Ortiz, O., Rusu, C., Rusu, V., Matus, N., & Ito, A. (2024). Tourist experience considering cultural factors: a systematic literature review. Sustainability, 16(22), 10042. [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E., & Corvello, V. (2014). Tourists’ acceptance of advanced technology-based innovations for promoting arts and culture. International Journal of Technology Management, 64(1), 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Pestek, A., & Sarvan, M. (2021). Virtual reality and modern tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures, 7(2), 245–250. [CrossRef]

- Rane, N., Choudhary, S., & Rane, J. (2023). Sustainable tourism development using leading-edge Artificial Intelligence (AI), Blockchain, Internet of Things (IoT), Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) technologies. SSRN Electronic Journal, December. [CrossRef]

- Rusu, V., Rusu, C., Matus, N., & Botella, F. (2023). Tourist experience challenges: A holistic approach. Sustainability, 15(17), 12765.

- Saneinia, S., Zhou, R., Gholizadeh, A., & Asmi, F. (2022). Immersive Media-Based Tourism Emerging Challenge of VR Addiction Among Generation Z. Frontiers in Public Health, 10(July), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M. S., Syed, T. A., Nadeem, A., Nawaz, W., & Alkhodre, A. (2022). Virtual Tourism and Digital Heritage: An Analysis of VR/AR Technologies and Applications. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 13(7), 303–315. [CrossRef]

- Suanpang, P., Niamsorn, C., Pothipassa, P., Chunhapataragul, T., Netwong, T., & Jermsittiparsert, K. (2022). Extensible Metaverse Implication for a Smart Tourism City. Sustainability, 14(21), 14027. [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S., Kaur, P., Escobar, O., & Lan, S. (2022). Virtual reality tourism to satisfy wanderlust without wandering: An unconventional innovation to promote sustainability. Journal of Business Research, 152(July), 128–143. [CrossRef]

- Tori, R., Kirner, C., & Siscouto, R. (2006). Fundamentos e tecnologia de Realidade Virtual e Aumentada. In Fundamentos e Tecnologia de Realidade Virtual e Aumentada. Sociedade Brasileira de Computação.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).