Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Chemical Composition | % Mass |

|---|---|

| Fe2O3 | 3.2 |

| SiO2 | 23.5 |

| MgO | 2.6 |

| Al2O3 | 3.5 |

| CaO | 63.5 |

| Alkalis | 0.54 |

| LOI | 0.82 |

| Others | 2.34 |

| Physical Properties | |

| Initial/final setting (min) | 140/480 |

| Specific gravity | 3.11 |

| Normal consistency (%) | 30 |

| Compressive strength, 28days (MPa) | 30.5 |

| Specific surface, Blaine (m2/kg) | 3.11 |

| Physical Properties | |

|---|---|

| Specific gravity | 2.60 |

| Bulk density | 1000 kg/m3 |

| Property | 10 mm Coarse Aggregate | 20 mm Coarse Aggregate |

|---|---|---|

| Water absorption (%) | 1.5 | 12.8 |

| Dry density (Mg/m3) | 2.57 | 1.42 |

| Shape index (%) | 12 | 32 |

| Fakiness index (%) | 23 | 37 |

| Impact value (%) | 18 | 12 |

3. Methodology

3.1. Mix Design

3.2. Sample Preparation

4. Results

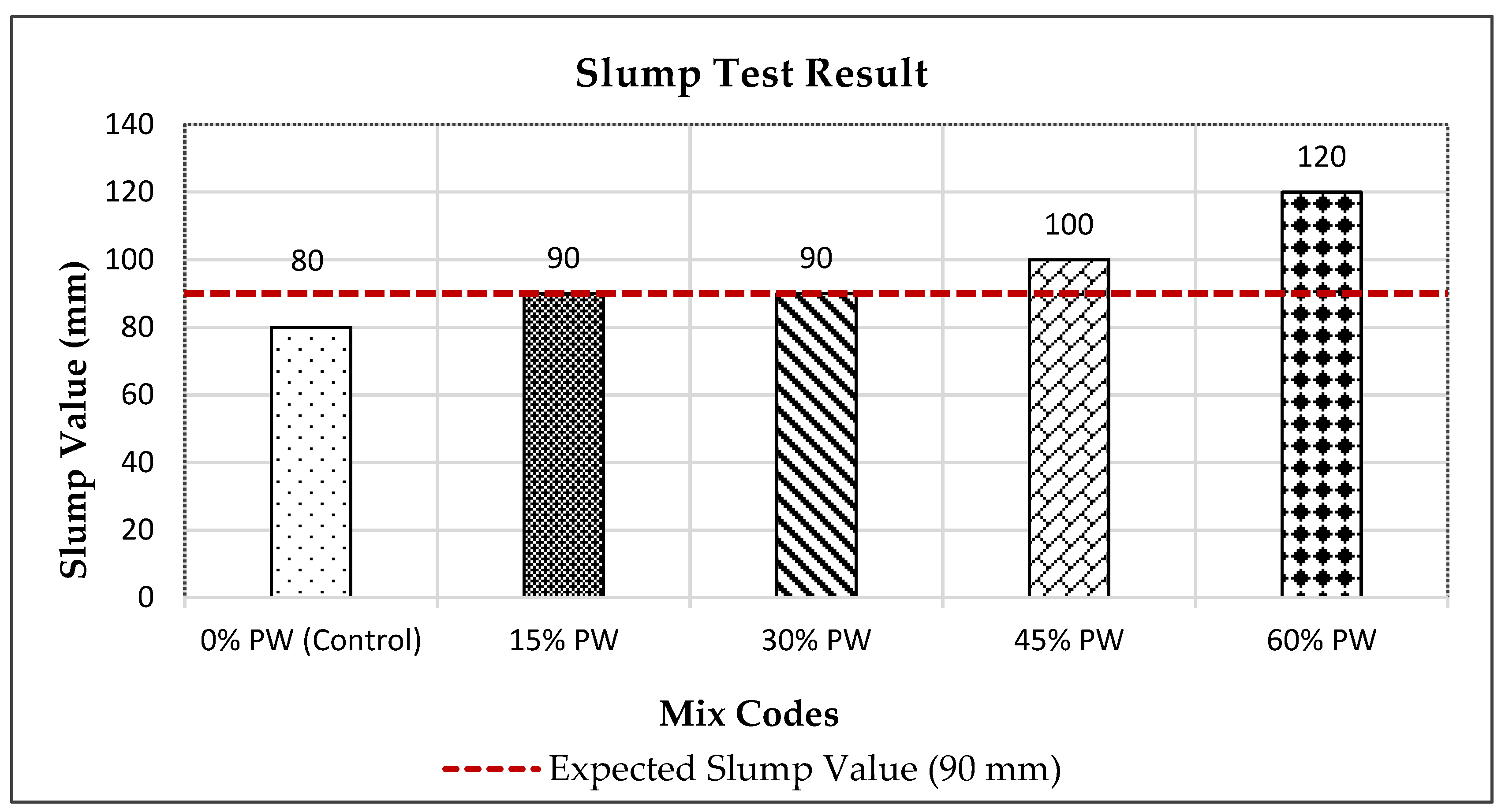

4.1. Workability Test

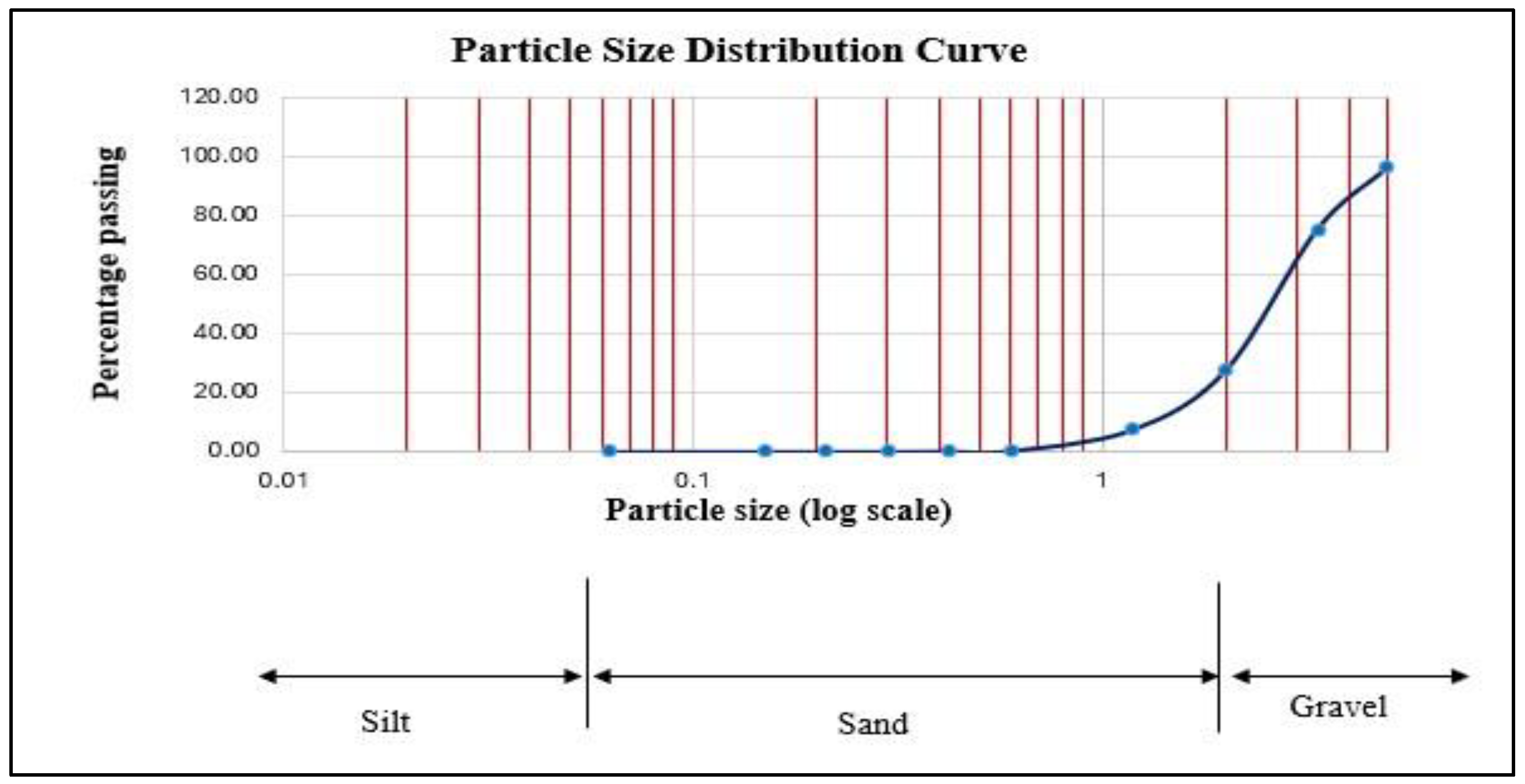

4.2. Sieve Analysis Test

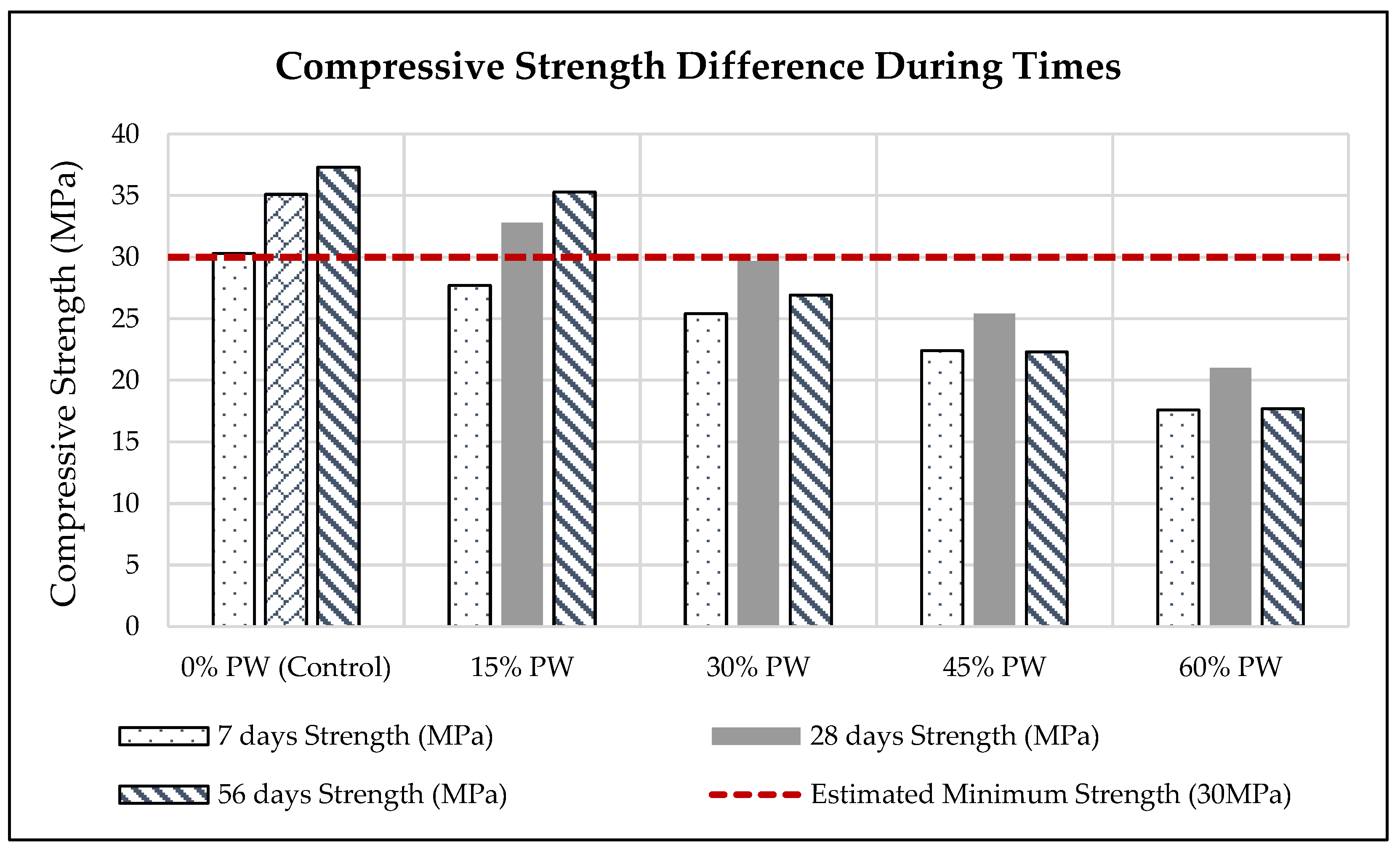

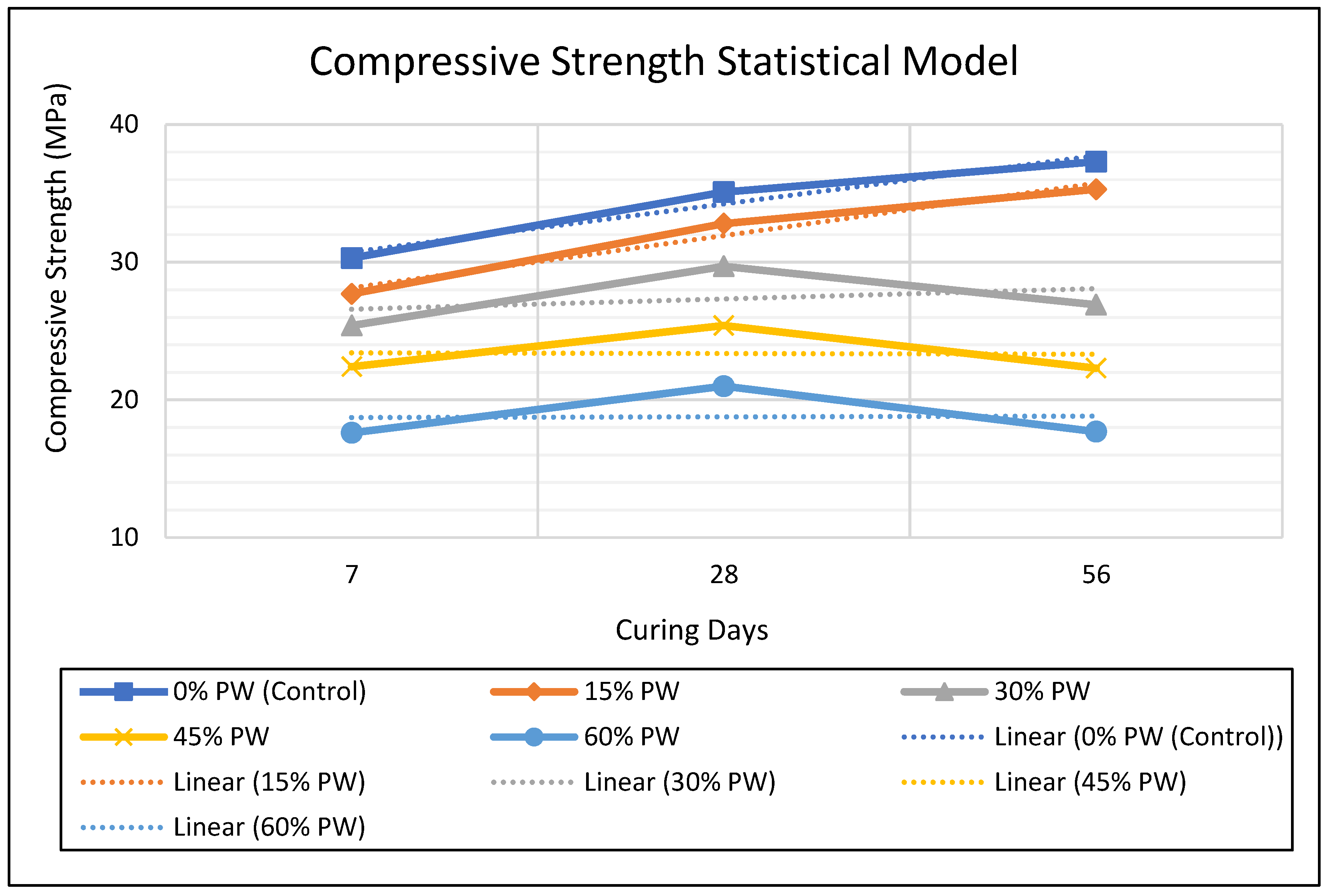

4.3. Compressive Strength Test

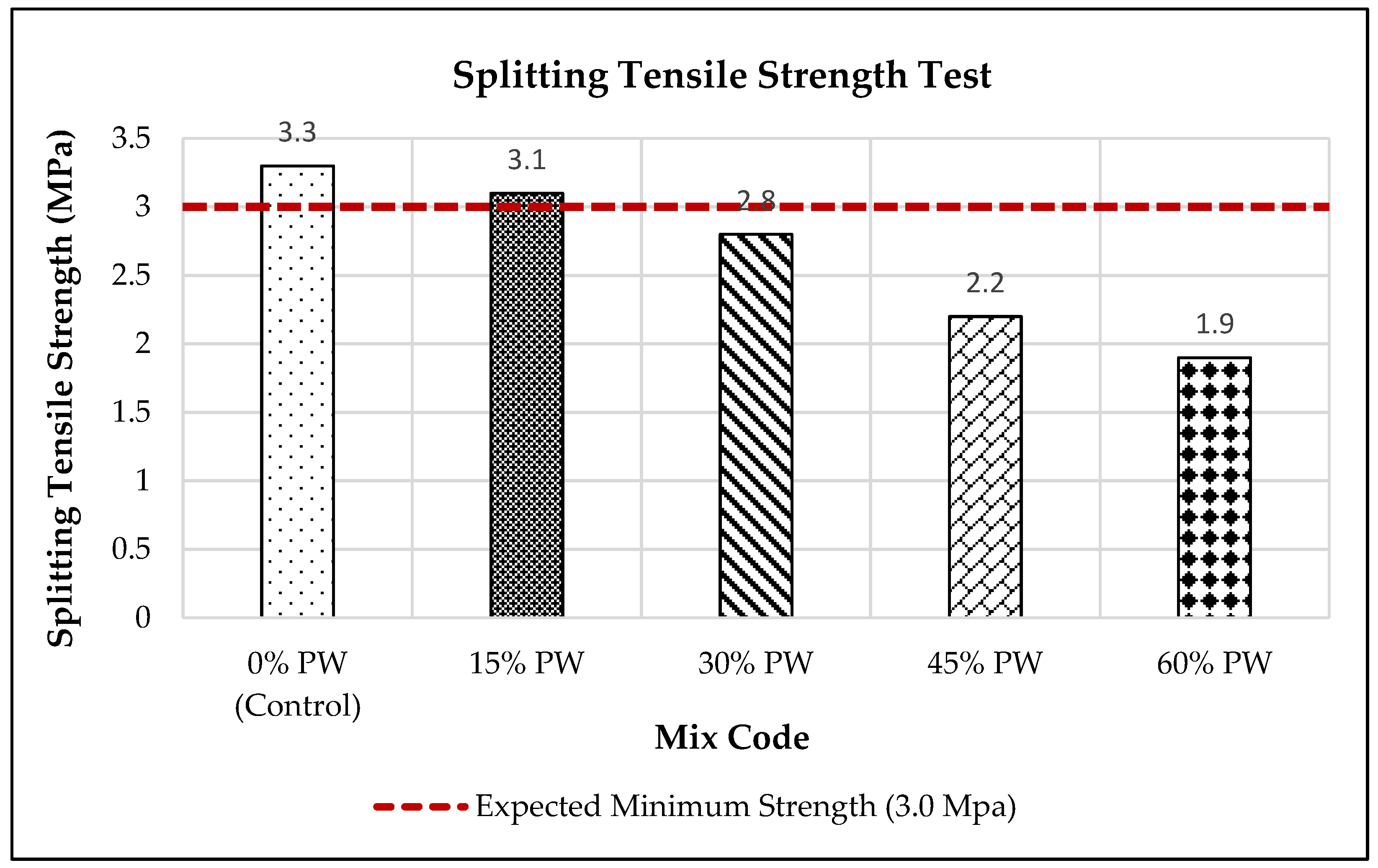

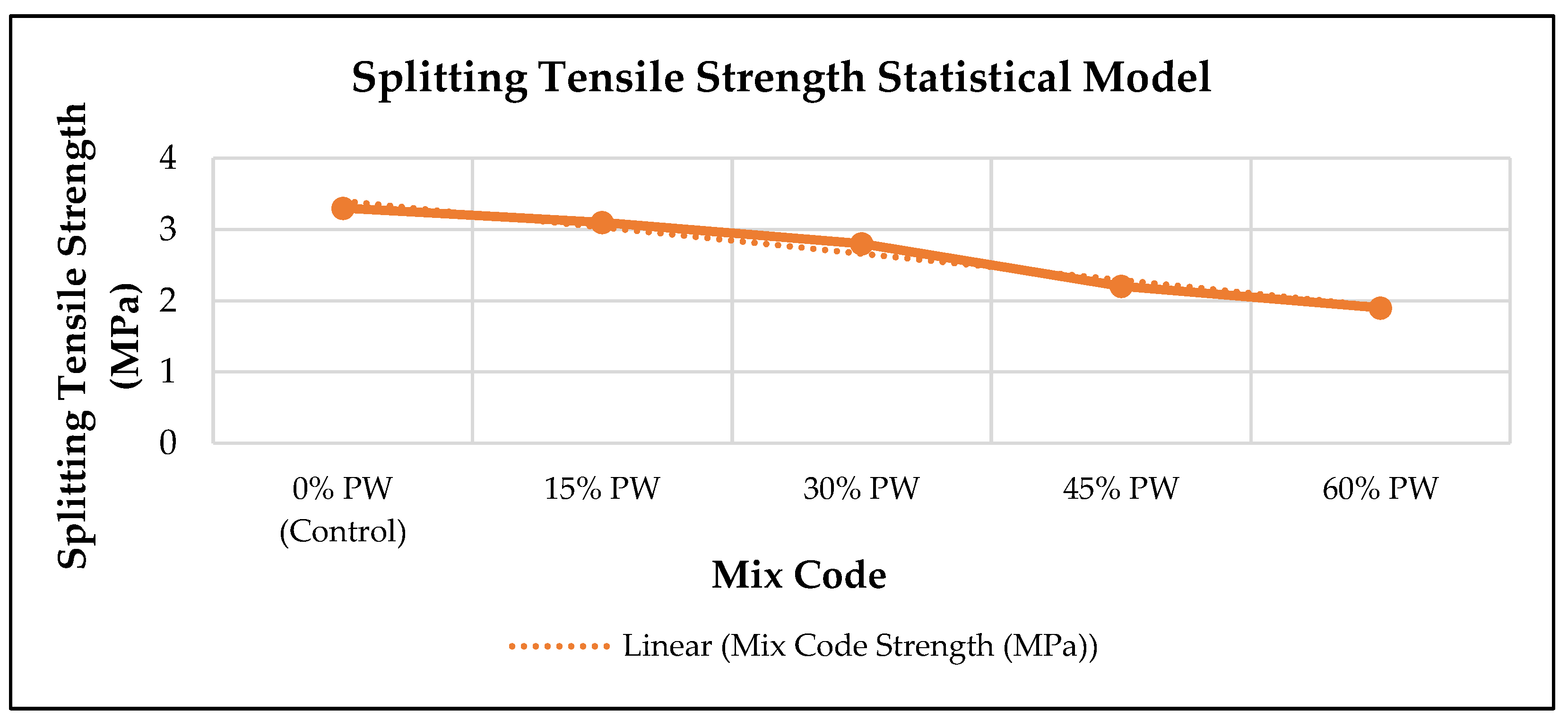

4.4. Splitting Tensile Strength Test

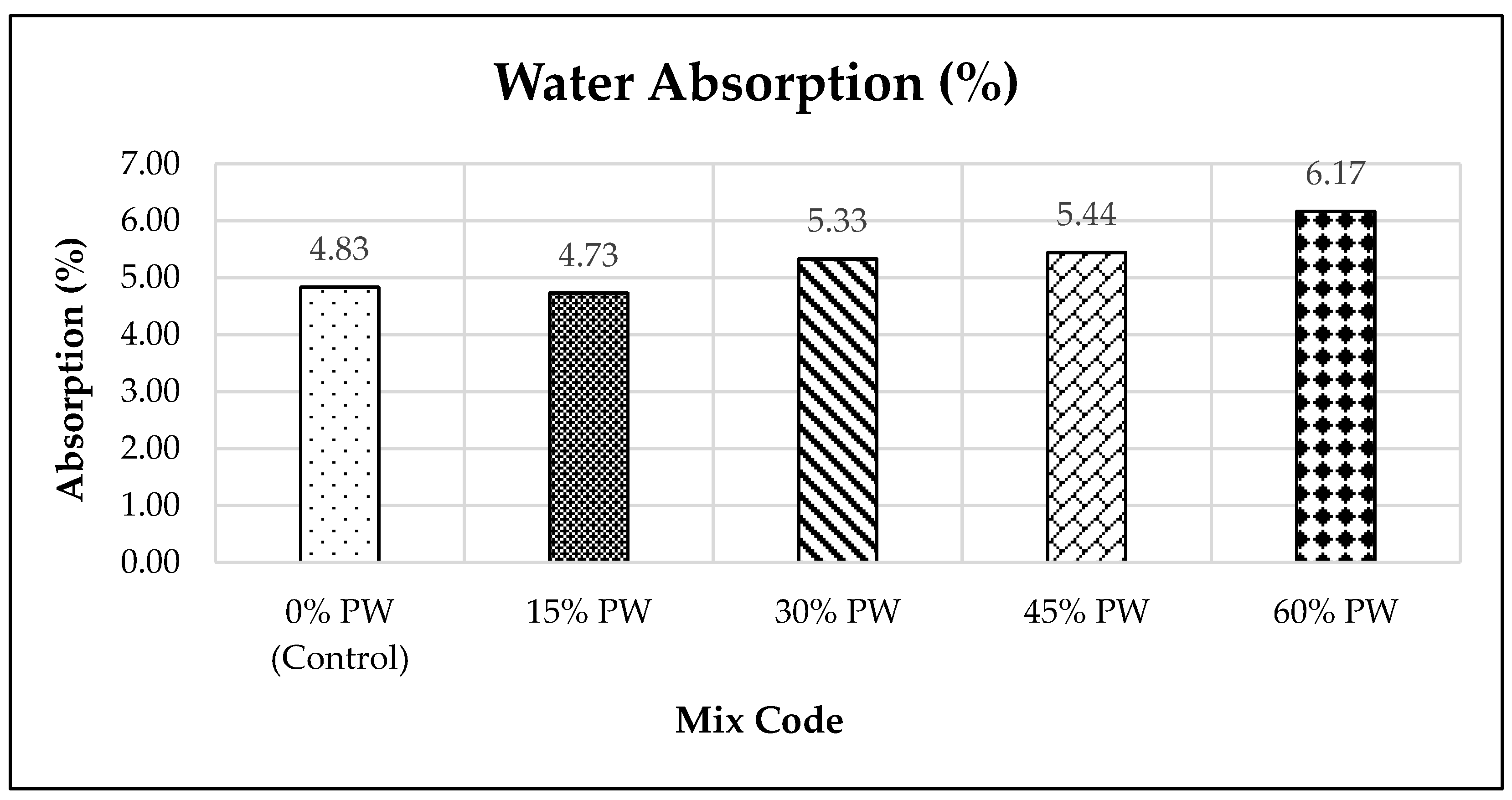

4.5. Durability: Water Absorption Test

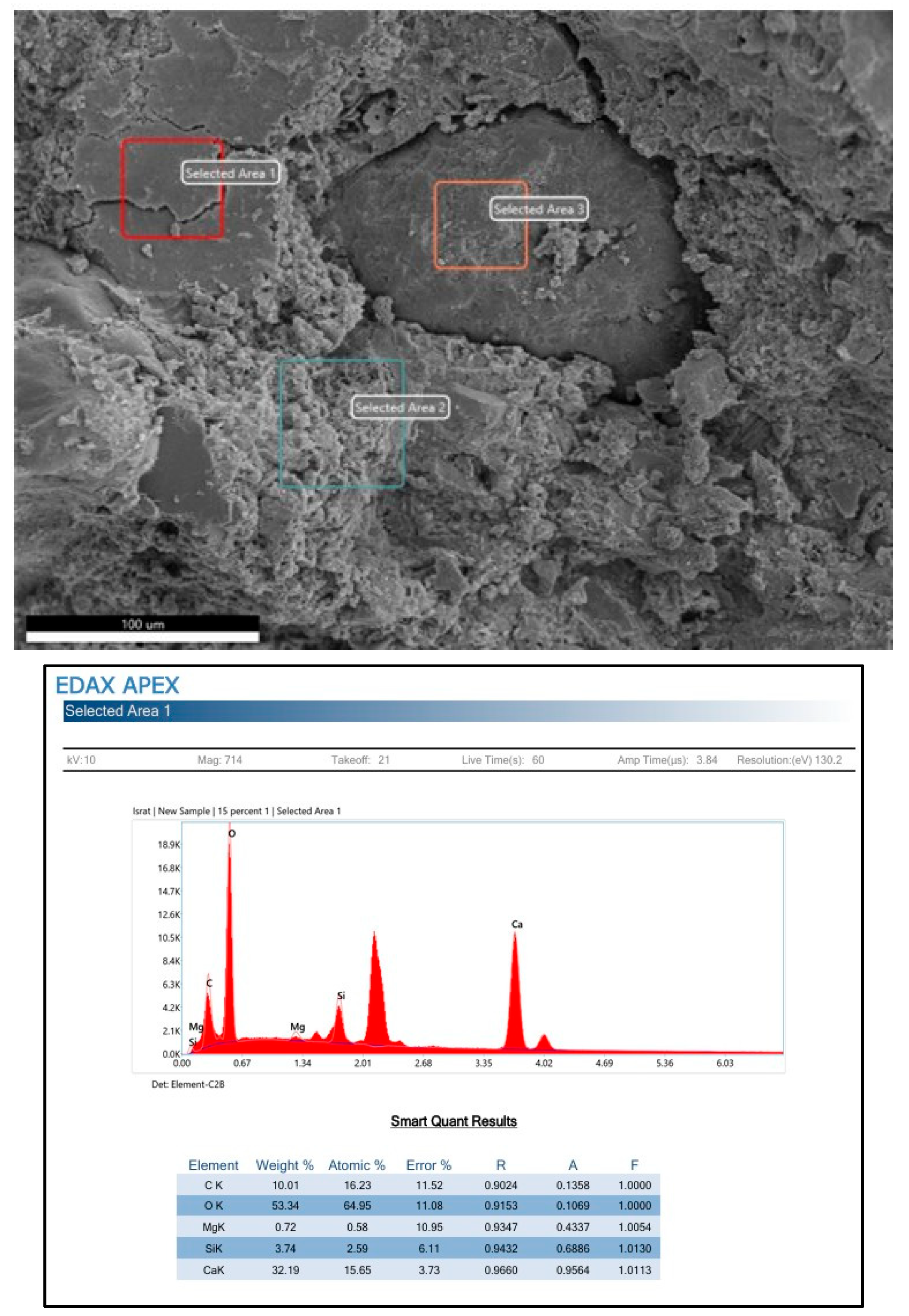

4.6. Microstructural Analysis (SEM)

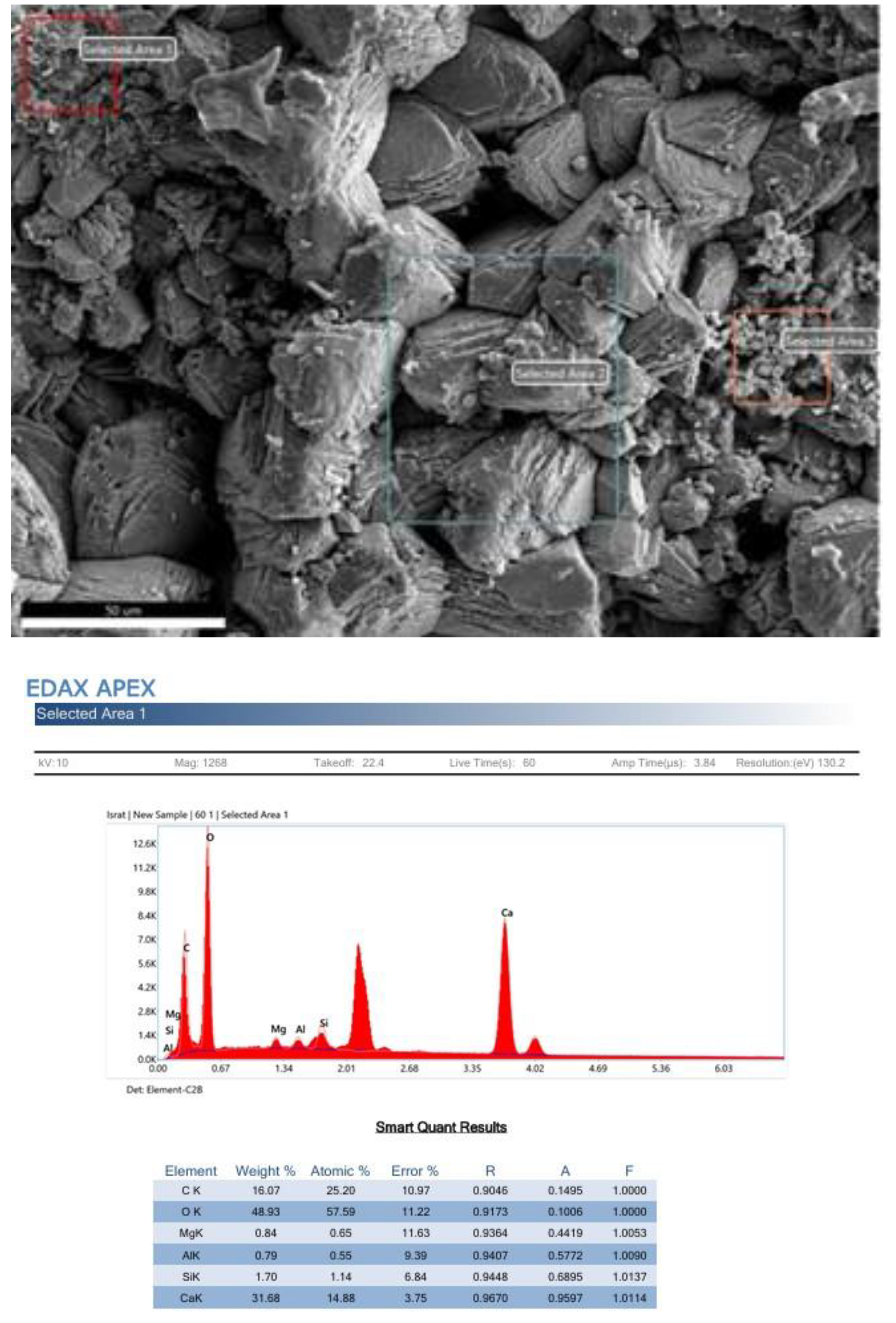

4.6.1. Controlled Mix Design SEM Test

4.6.2. SEM Results with Mix of Recycled Plastic Waste

4.7. Life Cycle Assessment (Numerical Results)

-

Cement Dominates Emissions

- Cement has a very high emission factor (≈0.95 kg CO₂/kg and 4.6 MJ/kg).

- In all mixes, the cement content remains constant (6 kg), so majority of the emissions and energy come from cement, not aggregates or plastic.

-

Plastic Processing Adds Energy

- Recycled plastic requires shredding, cleaning, and sometimes chemical treatment, which adds embodied energy (≈0.5 MJ/kg) and a small CO₂ footprint (≈0.02 kg CO₂/kg).

- Natural aggregates have very low energy and CO₂ factors (≈0.1 MJ/kg and 0.005 kg CO₂/kg).

- So, when you replace aggregates with plastic, you swap low-impact material for one with slightly higher energy and emissions.

-

Net Effect

- The increase is small because the quantities of aggregates and plastic are much smaller compared to cement.

- For example, going from 0% PW to 60% PW only changes total CO₂ from 5.75 kg to 5.84 kg (≈1.6% increase) and energy from 28.6 MJ to 31 MJ (≈8% increase).

5. Discussion

5.1. Durability: Water Absorption Test

5.2. Compressive Strength

5.3. Splitting Tensile Strength

5.4. Durability of Concrete: Water Absorption

5.5. Microstructural Analysis

5.6. Life Cycle Perspective

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusion

- The results of the slump test demonstrated that replacing coarse aggregates with plastic waste on volume basis increased the workability of fresh concrete. High slump means lots of water in the admixture, it can cause segregation, poor durability and voids. Improved workability shows because of the smooth texture and low density of plastic waste. The standard slump value shows in the replacement level of ≤15% PW that offers environmental benefits while maintaining structural integrity.

- Sieve analysis revealed that most PW particles in the range of 2 mm to 3.35 mm, within the range of Coarse Sand and Fine aggregate range. But mostly it is suitable for fine aggregate particles. Rather than throwing the plastic into dump, it is environmentally friendly to use it in the construction materials. Sieve analysis helps to find which replacement can be beneficial for the construction either with fine aggregate or coarse aggregate. In this study, it replaced with the coarse aggregate and the result shows less than 15% replacement can be usable for the concrete mix design.

- The focus of this study is on compressive strength analysis. The results show that compressive strength decreases with the increase of plastic waste content. At 15% replacement, the compressive strength was 35.3 MPa at 56 days which crossed the minimum strength range of our study. For the higher replacement, it shows that compressive strength decreases in 56 days compared to 28 days. It is because of the weak bonding in interfacial transition zone (ITZ). Plastic waste (PW) has a smooth, hydrophobic surface that does not chemically bond with cement paste. Over the time microcracks in this weak ITZ can propagate which reduce the load-carrying capacity instead of improving it.

- The splitting tensile strength also shows similar trends as the compressive strength test. The test occurred after 28 days of curing; 15% replacement only achieved the minimum strength with control mix. Higher PW showed decrease in strength. This indicates that a balance can be achieved between sustainability by using recycled materials and achieving the performance of design standards.

- Water absorption shows how much water can take in through its pores. Here, in this study, water absorption was slightly reduced at 15% PW by 4.73%, suggesting enhanced impermeability due to the non-porous nature of plastic. Increasing of the PW also increases the value of water absorption percentage which means high porosity, more interconnected voids and less resistance ingress.

- SEM analysis revealed that at low replacement of plastic waste, C-S-H gel was present and limited bonding showed between plastic particles and cement. But at higher PW replacement, ITZ showed weak bond, microcracks, voids become more prominent which explains why the compressive and tensile strength observed low strength.

- The LCA confirms that cement drives most environmental impacts, limiting direct carbon savings from PW substitution. However, PW integration supports circular economy principles by reducing landfill disposal and aggregate extraction. Combining mechanical performance data with full life cycle assessment is essential to ensure genuine sustainability gains across the concrete life span.

- All these findings proved that limited range of replacement of plastic waste in mix design can be usable for construction. Plastic waste is diverted from landfills, marine ecosystem, which reduces reliance on natural aggregate extraction. Reintegrating non-biodegradable waste into the construction cycle as a material. It will be cost efficient and environmentally sustainable.

6.2. Recommendations for Future Work

- Investigate the particle size and see which type of aggregate replacement will be beneficial for the mix design. Also, it needs to do chemical or mechanical modifications of PW to enhance adhesion with cement paste.

- Combining PW with supplementary cementitious materials such as fly ash, silica fume which may counterbalance strength loss while lowering CO₂ emissions from cement.

- Analyze overall environmental impact of using PW in concrete mix, considering embodied carbon, cost, energy savings and life cycle analysis.

- PW concrete should be prioritized for paving blocks, lightweight panels and non-load-bearing walls, where sustainability benefits outweigh strength demands.

- The durability and workability under the UV ray, temperature changes and chemical exposure also need to be proven. The costs of the whole collection of plastic and make usable for construction also need to be taken into consideration.

- Recent projects should be developed to assess real-world applicability, addressing practical concerns such as handling, scalability and economic feasibility, which will show the performance of partial replacement of plastic waste in concrete.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PW | Plastic Waste |

| PC | Portland Cement |

| PFA | Pulverised Fuel Ash |

| GGBS | Ground Granulated Blast-furnace Slag |

| ITZ | Interfacial Transition Zone |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| C-S-H | Calcium-Silicate-Hydrate |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

References

- Yu, Z.; Nurdiawati, A.; Kanwal, Q.; Al-Humaiqani, M.M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Assessing and mitigating environmental impacts of construction materials: Insights from environmental product declarations. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasiya, C. and Dayashankar, V.A., "Recycled Plastic in Concrete: A Comprehensive Review," nternational Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science, vol. 6, p. 11, 2024.

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Use of recycled plastics in concrete: A critical review. Waste Manag. 2016, 51, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeshal, I.; Tayeh, B.A.; Alyousef, R.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Mohamed, A.M. Eco-friendly concrete containing recycled plastic as partial replacement for sand. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 4631–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R.; Khatib, J.; Kaur, I. Use of recycled plastic in concrete: A review. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1835–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashaan, N.S. Waste Plastic In Concrete: Review And State Of The Art. Nanotechnology Perceptions 2024, 20, 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, N. and De Brito, J., ". Mechanical properties and abrasion behaviour of concrete containing shredded PET bottle waste as a partial substitution of natural aggregate," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 52, p. 236-244, 2014.

- Ma, S.; Li, W.; Shen, X. Study on the physical and chemical properties of Portland cement with THEED. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 213, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tararushkin, E.V., Shchelokova, T.N. and Kudryavtseva, V.D., "A study of strength fluctuations of Portland cement by FTIR," OP Conference Series Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 919, no. 2, p. 022017, 2020.

- Ismail, Z.Z.; Al-Hashmi, E.A. Use of waste plastic in concrete mixture as aggregate replacement. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2041–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashaan, N.S.; Ouano, C.A.E. An Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of Concrete with Different Types of Waste Plastics for Rigid Pavements. Appl. Mech. 2025, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Manaseer, A.A. and Dalal, B.J., "Concrete Containing Plastic Aggregate," Concrete International, vol. 19, p. 47-52, 1997.

- Chen, Z., Wang, X., Jiang, K., Zhao, X., Liu, X and Wu, Z. 2024. The splitting tensile strength and impact resistance of concrete reinforced with hybrid BFRP minibars and micro fibers. Journal of Building Engineering, Volume 88, p. 109188., "The splitting tensile strength and impact resistance of concrete reinforced with hybrid BFRP minibars and micro fibers," Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 88, p. 109188, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.M.; Al-Attar, A.; Abed, F.; Beddu, S.; Humada, A.M.; Majdi, A.; Yousif, S.T.; Thomas, B.S. Enhancing sustainability in concrete construction: A comprehensive review of plastic waste as an aggregate material. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamedsalih, M.A.; Radwan, A.E.; Alyami, S.H.; El Aal, A.K.A. The Use of Plastic Waste as Replacement of Coarse Aggregate in Concrete Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magbool, H.M. Sustainability of utilizing recycled plastic fiber in green concrete: A systematic review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.H.; Paul, S.C.; Kong, S.Y.; Susilawati, S.; Yang, X. Modification of Waste Aggregate PET for Improving the Concrete Properties. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Zhao, Z.-Y. Green building research–current status and future agenda: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrat, F.S.; Ghebrab, T.T. Effect of Mill-Rejected Granular Cement Grains on Healing Concrete Cracks. Materials 2020, 13, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, A.M., Properties of Concrete, 5th ed., Pearson Education Limited, 2011.

- Oti, J.; Adeleke, B.O.; Rathnayake, M.; Kinuthia, J.M.; Ekwulo, E. Strength and Durability Characterization of Structural Concrete Made of Recycled Plastic. Materials 2024, 17, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BS EN 12390-2:2019, "Testing hardened concrete, Part 2: Making and curing specimens for strength tests," 31 July 2019. [Online].

- BS EN 12390-3:2019, "Testing hardened concrete, Part 4: Compressive strength of test specimens," 31 July 2019. [Online].

- BS EN 12390-6:2023, "Testing hardened concrete, Part 6: Tensile splitting strength of test specimens," 30 November 2023. [Online].

- BS EN 12350-2:2019, "Testing fresh concrete, Part 2: Slump test," 31 July 2019. [Online].

- BS EN 1097-6:2022, "Tests for mechanical and physical properties of aggregates - Determination of particle density and water absorption," 31 March 2022. [Online].

- BS EN 933-1:2012, "Tests for geometrical properties of aggregates, Part 1: Determination of particle size distribution. Sieving method," 29 February 2012. [Online].

- BS 1881-211:2016, "Testing concrete - Procedure and terminology for the petrographic examination of hardened concrete," 30 November 2016. [Online].

- Shukur, M.H.; Ibrahim, K.A.; Al-Darzi, S.Y.; Salih, O.A. Mechanical properties of concrete using different types of recycled plastic as an aggregate replacement. Cogent Eng. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-García, D.C.; Vargas-Leal, A.J.; Serrania-Guerra, D.A.; González-Borrego, J.G.; Saldaña-Márquez, H. Sustainable Concrete with Recycled Aggregate from Plastic Waste: Physical–Mechanical Behavior. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoikar, P.P., Orr, J.J. and Borkar, S.P., "Advanced tests for durability studies of concrete with plastic waste," 2015.

| Sl. No. | Mix Codes | Cement (kg) | Fine Aggregate (kg) |

Recycled Plastic Waste (kg equivalent by volume) |

Coarse Aggregate 10mm (kg) | Coarse Aggregate 20mm (kg) | Water (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0% PW (Control) | 6 | 12 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 3.3 |

| 2 | 15% PW | 6 | 12 | 0.4 | 6.8 | 10 | 3.3 |

| 3 | 30% PW | 6 | 12 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 10 | 3.3 |

| 4 | 45% PW | 6 | 12 | 1.2 | 4.4 | 10 | 3.3 |

| 5 | 60% PW | 6 | 12 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 10 | 3.3 |

| BS Test Sieve Size | Mass Retained (g) |

% Retained | Cumulative % Retained | % Passing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mm | 6.8 | 3.41 | 3.41 | 96.59 |

| 3.35 mm | 42.3 | 21.18 | 24.59 | 75.41 |

| 2 mm | 95.4 | 47.77 | 72.36 | 27.64 |

| 1.18 mm | 40.4 | 20.23 | 92.59 | 7.41 |

| 600 µm | 14.1 | 7.06 | 99.65 | 0.35 |

| 425 µm | 0.5 | 0.25 | 99.90 | 0.10 |

| 300 µm | 0.2 | 0.10 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| 212 µm | — | — | — | — |

| 150 µm | — | — | — | — |

| 63 µm | — | — | — | — |

| Total = 199.7 | 100.00 |

| Mix | CO₂ Emissions (kg) |

Embodied Energy (MJ) |

|---|---|---|

| Control (0%) | 5.75 | 28.6 |

| 15% PW | 5.77 | 29.2 |

| 30% PW | 5.79 | 29.8 |

| 45% PW | 5.82 | 30.4 |

| 60% PW | 5.84 | 31.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).