Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

CCS CONCEPTS

1. Introduction

1.1. State of the Art

1.2. A New Approach

2. Problem Formulation

3. Methods

3.1. TWAP

3.2. VWAP

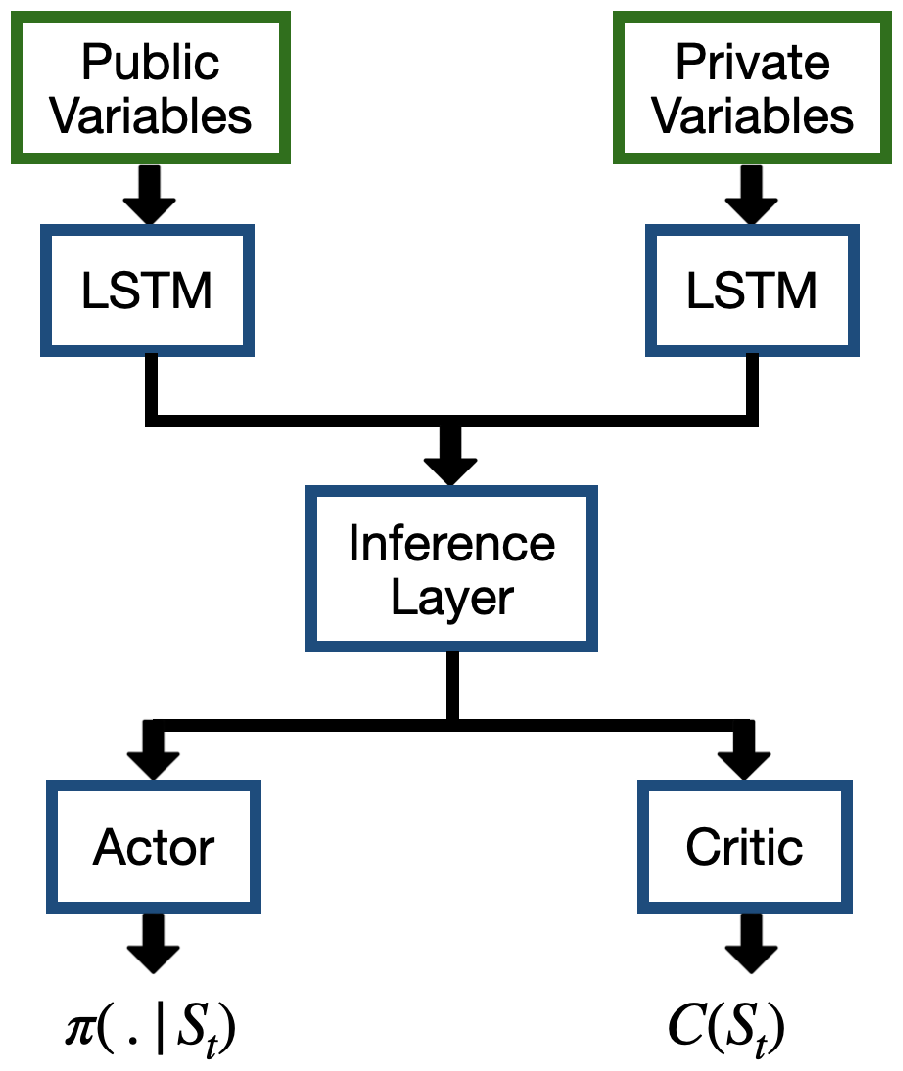

3.3. DRL

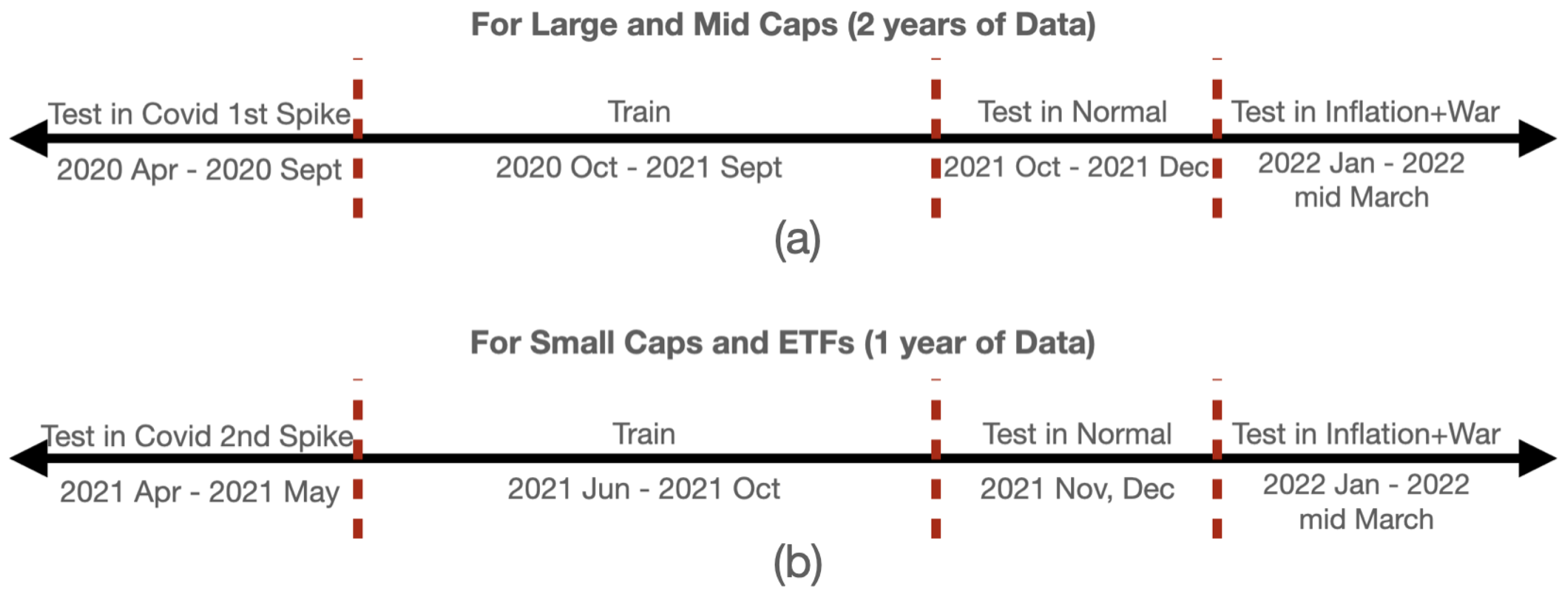

4. Results

4.1. Returns

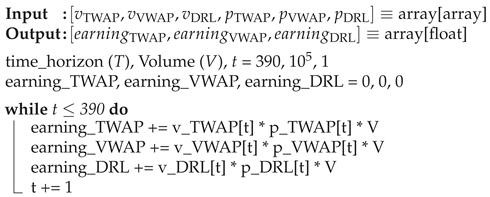

| Algorithm 1: Calculation of monetary gain by DRL over TWAP/VWAP |

|

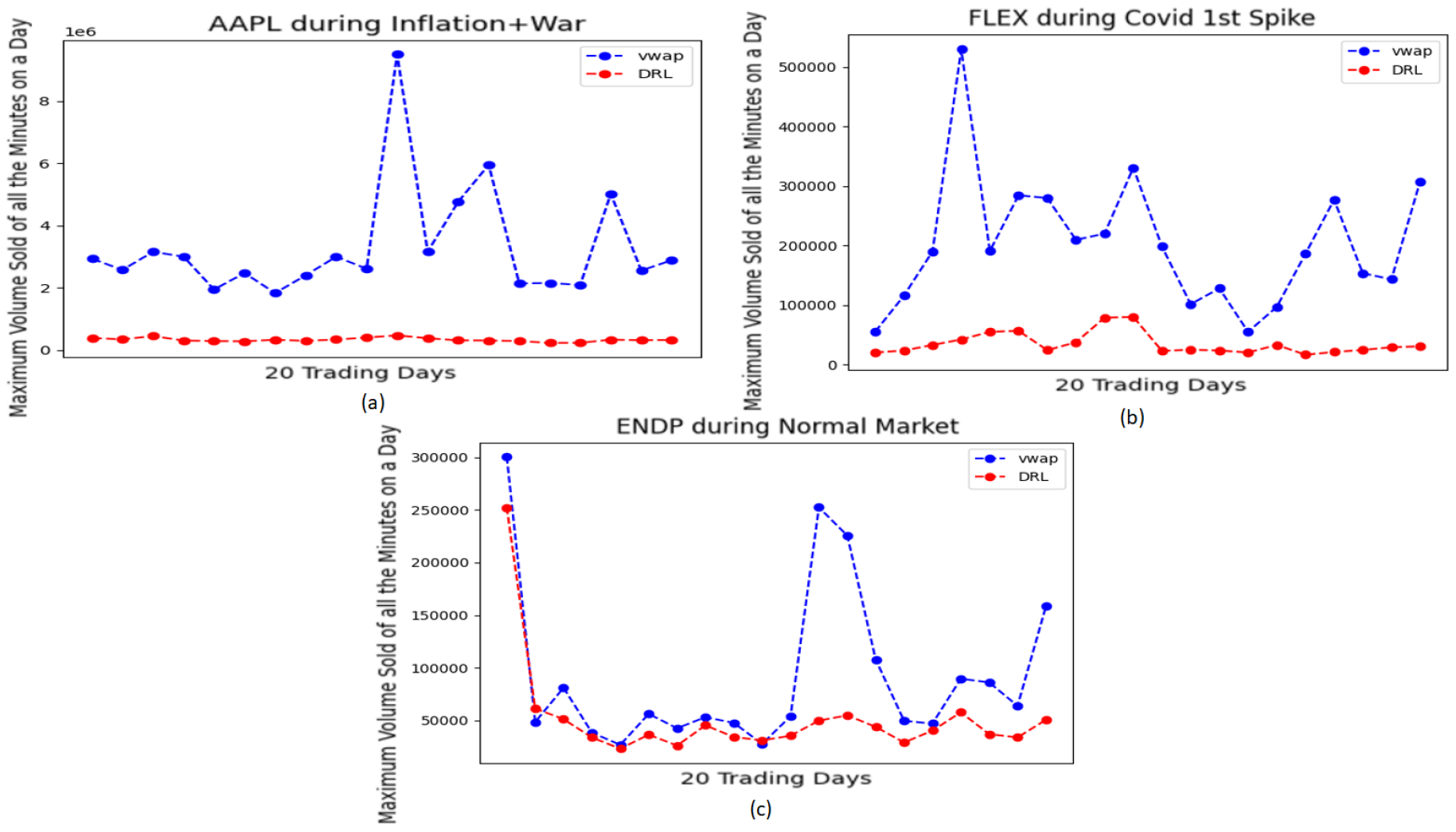

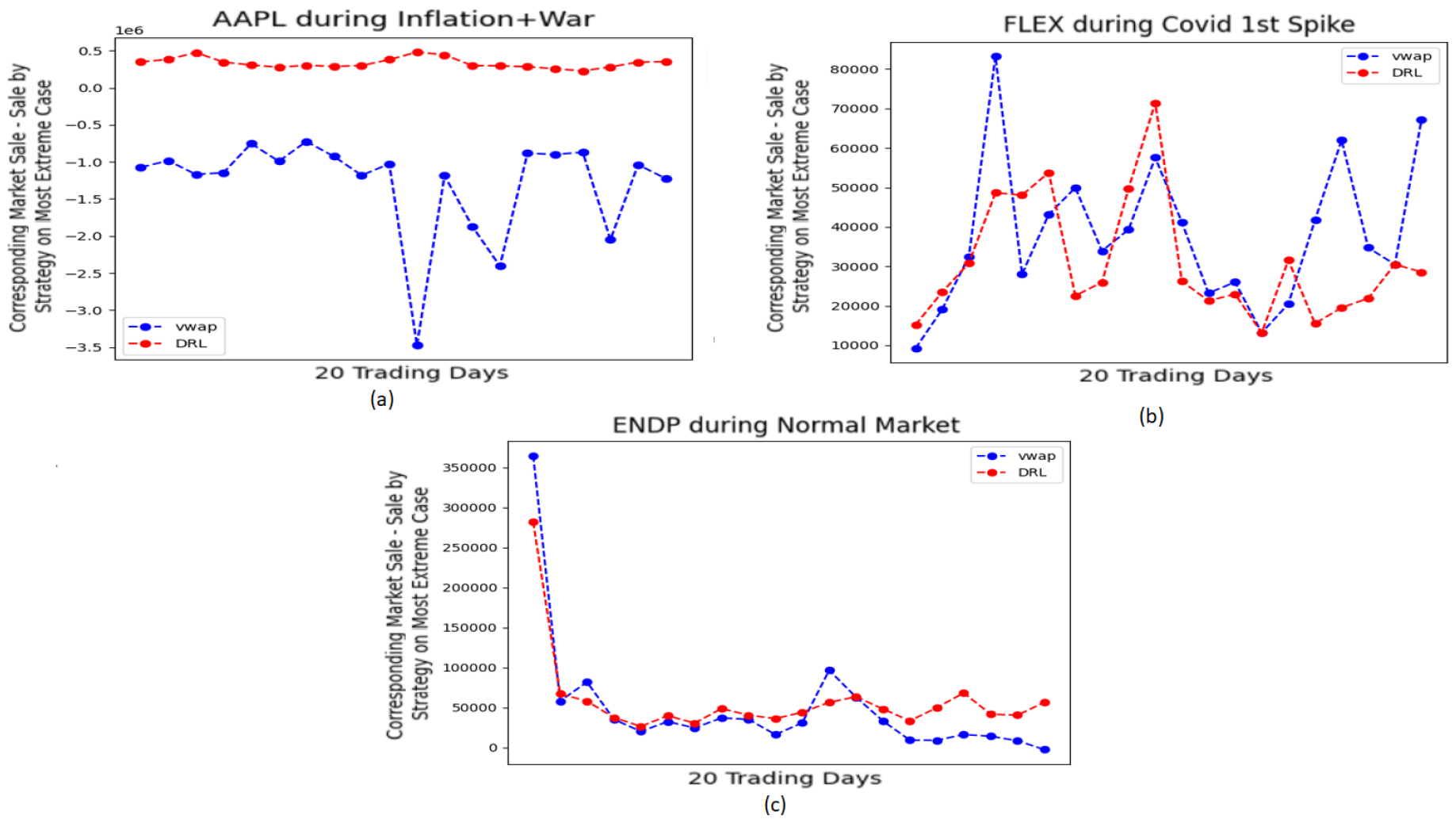

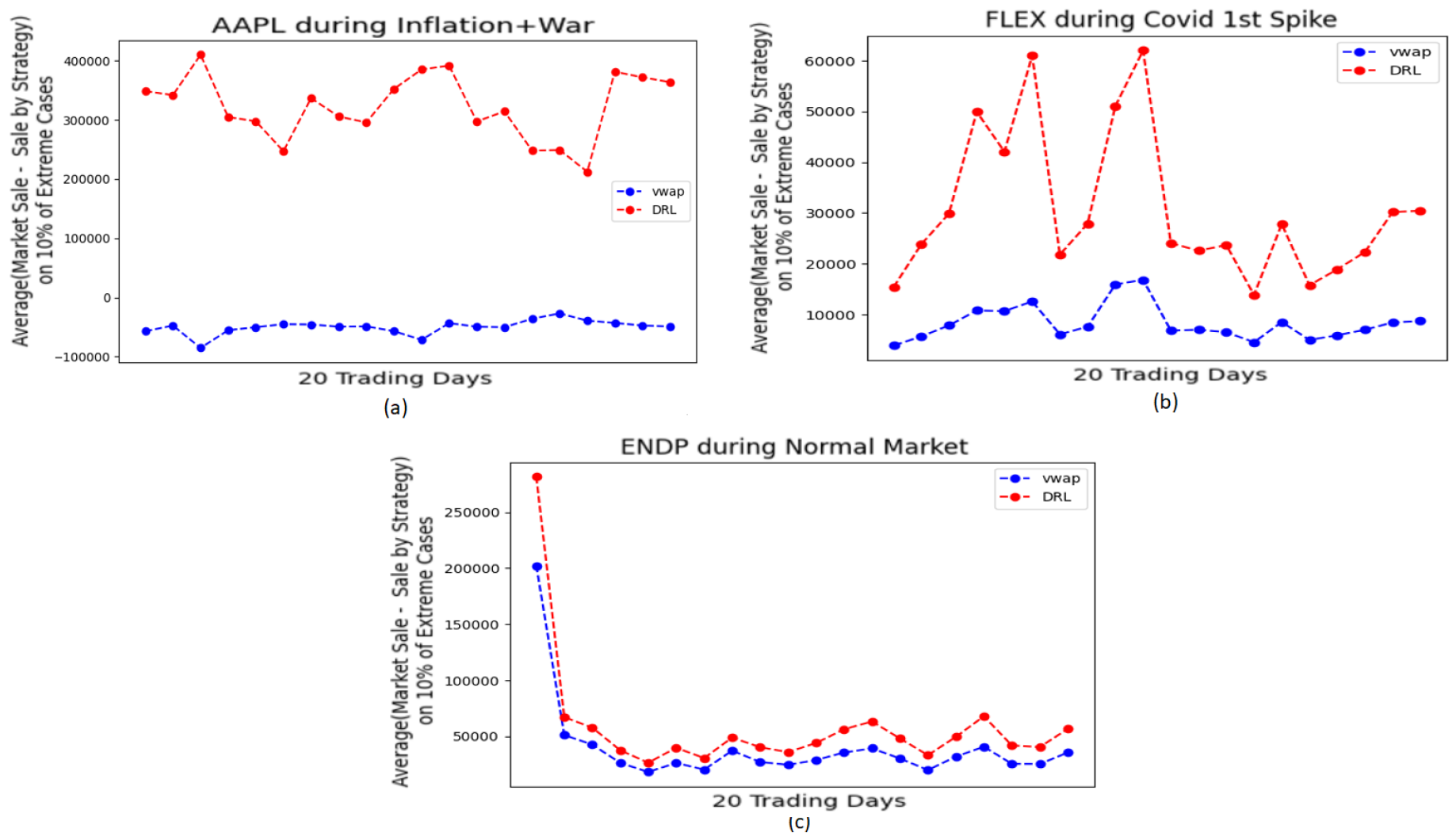

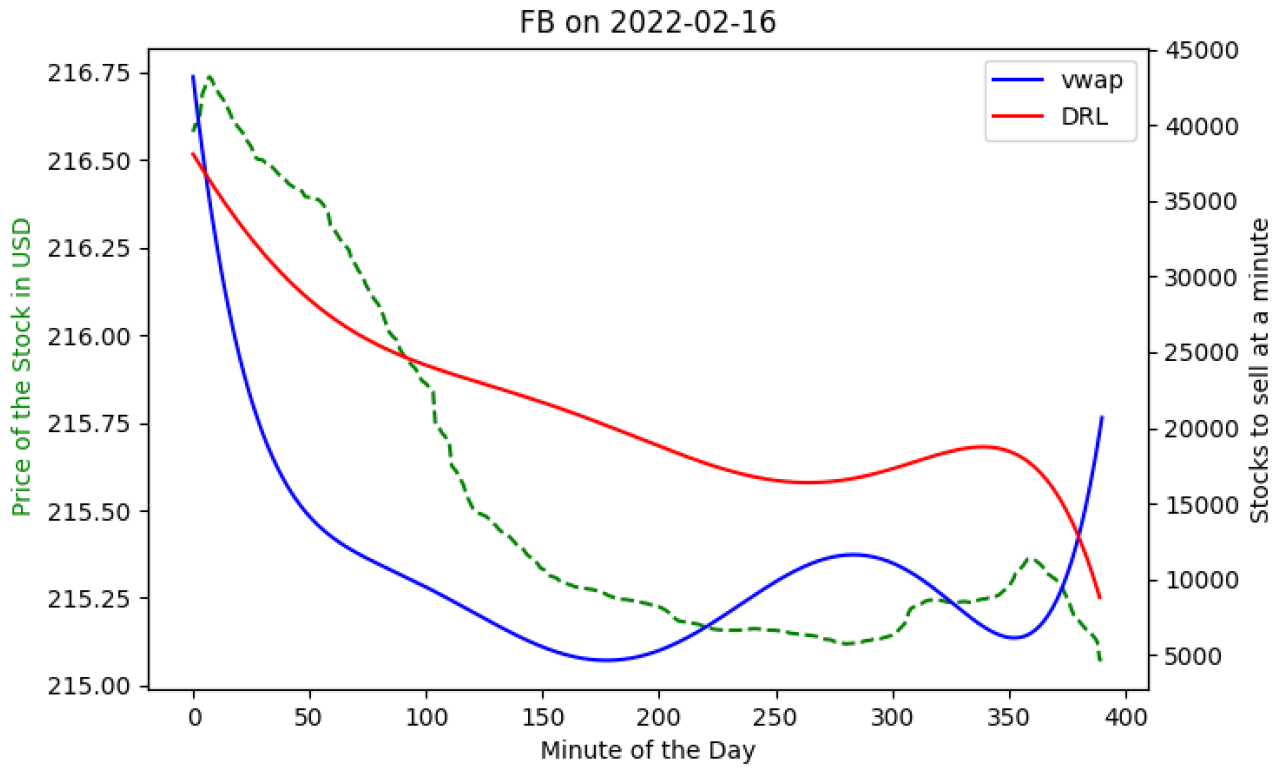

4.2. Market Risks

5. Conclusions and Discussion

References

- Aurélien Alfonsi, Antje Fruth, and Alexander Schied. 2009. Optimal Execution Strategies in Limit Order Books with General Shape Functions. SSRN Electronic Journal (2009). [CrossRef]

- Robert Almgren and Neil Chriss. 2001. Optimal execution of portfolio transactions. The Journal of Risk 3, 2 (Jan. 2001), 5–39. [CrossRef]

- Bastien Baldacci and Jerome Benveniste. 2019. A Note on Almgren–Chriss Optimal Execution Problem with Geometric Brownian Motion. Market Microstructure and Liquidity 05, 01n04 (Dec. 2019). [CrossRef]

- Dimitris Bertsimas and Andrew Lo. 1998. Optimal Control of Execution Costs. Journal of Financial Markets 1, 1 (1998), 1–50. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:finmar:v:1:y:1998:i:1:p:1-50.

- Sabri Boubaker, John W. Goodell, Dharen Kumar Pandey, and Vineeta Kumari. 2022. Heterogeneous impacts of wars on global equity markets: Evidence from the invasion of Ukraine. Finance Research Letters 48 (Aug. 2022), 102934. [CrossRef]

- Christine Brentani. 2004. Portfolio Management in Practice (Essential Capital Markets). Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK.

- Scott Brown, Timothy Koch, and Eric Powers. 2009. SLIPPAGE AND THE CHOICE OF MARKET OR LIMIT ORDERS IN FUTURES TRADING. Journal of Financial Research 32, 3 (Sept. 2009), 309–335. [CrossRef]

- Alvaro Cartea and Sebastian Jaimungal. 2015. Incorporating order-flow into optimal execution. Mathematics and Financial Economics 10 (2015), 339–364. [CrossRef]

- Alvaro Cartea, Sebastian Jaimungal, and Jose Penalva. 2015. Algorithmic and High-Frequency Trading. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Arthur Charpentier, Romuald Elie, and Carl Remlinger. 2020. Reinforcement Learning in Economics and Finance. ArXiv abs/2003.10014 (2020).

- Jianyu Chen, Bodi Yuan, and Masayoshi Tomizuka. 2019. Model-free Deep Reinforcement Learning for Urban Autonomous Driving. In 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Ming Deng, Markus Leippold, Alexander F. Wagner, and Qian Wang. 2022. Stock Prices and the Russia-Ukraine War: Sanctions, Energy and ESG. SSRN Electronic Journal (2022). [CrossRef]

- Joris Dinneweth, Abderrahmane Boubezoul, René Mandiau, and Stéphane Espié. 2022. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for autonomous vehicles: a survey. Autonomous Intelligent Systems 2, 1 (Nov. 2022). [CrossRef]

- Matthew Francis Dixon and Igor Halperin. 2020. G-Learner and GIRL: Goal Based Wealth Management with Reinforcement Learning. SSRN Electronic Journal (2020). [CrossRef]

- Kevin Dowd. 2007. Measuring Market Risk. John Wiley & Sons, NJ, USA.

- Yuchen Fang, Kan Ren, Weiqing Liu, Dong Zhou, Weinan Zhang, Jiang Bian, Yong Yu, and Tie-Yan Liu. 2021. Universal Trading for Order Execution with Oracle Policy Distillation. [CrossRef]

- Jonathan Federle and Victor Sehn. 2022. Costs of Proximity to War Zones: Stock Market Responses to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine. SSRN Electronic Journal (2022). [CrossRef]

- Shubha Ghosh and David M. Driesen. 2003. The Functions of Transaction Costs: Rethinking Transaction Cost Minimization in a World of Friction. SSRN Electronic Journal (2003). [CrossRef]

- John Greenwood and Steve H. Hanke. 2021. On Monetary Growth and Inflation in Leading Economies, 2021-2022: Relative Prices and the Overall Price Level. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 33, 4 (Dec. 2021), 39–51. [CrossRef]

- Tobin Hanspal, Annika Weber, and Johannes Wohlfart. 2021. Exposure to the COVID-19 Stock Market Crash and Its Effect on Household Expectations. The Review of Economics and Statistics 103, 5 (Nov. 2021), 994–1010. [CrossRef]

- Jeff Heaton. 2017. Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville: Deep learning. Genetic Programming and Evolvable Machines 19, 1-2 (Oct. 2017), 305–307. [CrossRef]

- Sepp Hochreiter and Jürgen Schmidhuber. 1997. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation 9, 8 (Nov. 1997), 1735–1780. [CrossRef]

- L. P. Kaelbling, M. L. Littman, and A. W. Moore. 1996. Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 4 (May 1996), 237–285. [CrossRef]

- B Ravi Kiran, Ibrahim Sobh, Victor Talpaert, Patrick Mannion, Ahmad A. Al Sallab, Senthil Yogamani, and Patrick Perez. 2022. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 23, 6 (June 2022), 4909–4926. [CrossRef]

- Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. 2015. Deep learning. Nature 521, 7553 (May 2015), 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Yuxi Li. 2017. Deep Reinforcement Learning: An Overview. ArXiv abs/1701.07274 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Siyu Lin and Peter A. Beling. 2020. An End-to-End Optimal Trade Execution Framework based on Proximal Policy Optimization. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization. [CrossRef]

- Mieszko Mazur, Man Dang, and Miguel Vega. 2021. COVID-19 and the march 2020 stock market crash. Evidence from SnP500. Finance Research Letters 38 (Jan. 2021), 101690. [CrossRef]

- Volodymyr Mnih, Koray Kavukcuoglu, David Silver, Alex Graves, Ioannis Antonoglou, Daan Wierstra, and Martin Riedmiller. 2013. Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning. [CrossRef]

- Volodymyr Mnih, Koray Kavukcuoglu, David Silver, Andrei A. Rusu, Joel Veness, Marc G. Bellemare, Alex Graves, Martin Riedmiller, Andreas K. Fidjeland, Georg Ostrovski, Stig Petersen, Charles Beattie, Amir Sadik, Ioannis Antonoglou, Helen King, Dharshan Kumaran, Daan Wierstra, Shane Legg, and Demis Hassabis. 2015. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 518, 7540 (Feb. 2015), 529–533. [CrossRef]

- Yuriy Nevmyvaka, Yi Feng, and Michael Kearns. 2006. Reinforcement learning for optimized trade execution. In Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning - ICML ’06. ACM Press. [CrossRef]

- Y. Nevmyvaka, M. Kearns, A. Papandreou, and K. Sycara. [n. d.]. Electronic Trading in Order-Driven Markets: Efficient Execution. In Seventh IEEE International Conference on E-Commerce Technology (CEC’05). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Jürgen Schmidhuber. 2015. Deep learning in neural networks: An overview. Neural Networks 61 (Jan. 2015), 85–117. [CrossRef]

- Shai Shalev-Shwartz, Shaked Shammah, and Amnon Shashua. 2016. Safe, Multi-Agent, Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving. ArXiv abs/1610.03295 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Min Shu, Ruiqiang Song, and Wei Zhu. 2021. The ‘COVID’ crash of the 2020 U.S. Stock market. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 58 (Nov. 2021), 101497. [CrossRef]

- Philip Sommer and Stefano Pasquali. 2016. Liquidity-How to Capture a Multidimensional Beast. The Journal of Trading (March 2016). [CrossRef]

- Paul Stoewer, Christian Schlieker, Achim Schilling, Claus Metzner, Andreas Maier, and Patrick Krauss. 2022. Neural network based successor representations to form cognitive maps of space and language. Scientific Reports 12, 1 (July 2022). [CrossRef]

- R.S. Sutton and A.G. Barto. 1998. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 9, 5 (1998), 1054–1054. [CrossRef]

- Christopher J. C. H. Watkins and Peter Dayan. 1992. Q-learning. Machine Learning 8, 3-4 (May 1992), 279–292. [CrossRef]

- Kenta Yamada and Takayuki Mizuno. 2020. Analyses of Daily Market Impact Using Execution and Order Book Information. Frontiers in Physics 8 (Nov. 2020). [CrossRef]

- Deheng Ye, Guibin Chen, Wen Zhang, Sheng Chen, Bo Yuan, Bo Liu, Jia Chen, Zhao Liu, Fuhao Qiu, Hongsheng Yu, Yinyuting Yin, Bei Shi, Liang Wang, Tengfei Shi, Qiang Fu, Wei Yang, Lanxiao Huang, and Wei Liu. 2020. Towards Playing Full MOBA Games with Deep Reinforcement Learning. [CrossRef]

| Stock | VWAP | DRL | VWAP | DRL | VWAP | DRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covid | Covid | Normal Market | Normal Market | Inflation+War | Inflation+War | |

| AAPL | -0.009 | 6.3161 | 1.59 | 2.68 | -0.027 | 0.59 |

| FB | -0.004 | 4.57 | -0.03 | 0.79 | -0.009 | 10.02 |

| IBM | 0.068 | 1 | 1.67 | 2.82 | 0.056 | 0.71 |

| MSFT | -0.009 | 2.434 | 1.61 | 2.44 | -0.015 | 0.77 |

| goog | 0.957 | 3.063 | 1.16 | 1.72 | 4.3 | 5 |

| AMZN | 0.104 | 5.175 | 2.5 | 3.05 | 0.48 | 1.1 |

| GDS | 5.65 | 11.56 | 17.9 | 18.58 | 9.68 | 10.46 |

| LECO | 45.125 | 47.3287 | 51.97 | 55.06 | 51.97 | 55.06 |

| FLEX | 1.18 | 4.18 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 1.66 | 2.53 |

| OLLI | 3.95 | 19.51 | 13.29 | 13.9 | 6.05 | 7 |

| SFIX | 1.44 | 11.01 | 3.5 | 10.9 | 0.32 | 7.63 |

| AMBA | 33.8 | 34.46 | 20.94 | 24.38 | 20.36 | 30.12 |

| ARES | 14.9 | 16.9 | 31 | 31.4 | 17.68 | 18.31 |

| VO | 8.8 | 10.2 | 12.5 | 13 | 5.18 | 5.72 |

| PRTS | 16.178 | 17 | 25.368 | 26.69 | 17.83 | 21.77 |

| PUBM | 23.09 | 29.56 | 11.8 | 20.63 | 9.1 | 12.74 |

| INSG | 5.168 | 7.06 | 9.48 | 11.62 | 11.43 | 13 |

| APPH | 7.48 | 13.64 | 10.55 | 12 | 27.73 | 28.86 |

| PERI | 0.63 | 37.603 | 34.2 | 36.5 | 27.73 | 29.03 |

| ARLO | 26.07 | 27.02 | 38.68 | 46.45 | 17.26 | 17.71 |

| ENDP | 3.31 | 9.74 | 6.14 | 8.1 | 2.82 | 7.53 |

| CVLT | 56.44 | 58.57 | 89.64 | 90.69 | 71.49 | 72.01 |

| NDAQ | 12.8 | 14.47 | 20.3 | 20.8 | 13.44 | 13.88 |

| DOW | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.47 | 2.27 | 0.1 | 0.72 |

| Stock | Covid | Normal Market | Inflation+War | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TWAP | VWAP | TWAP | VWAP | TWAP | VWAP | |

| AAPL | $55,000 | $91,000 | $237,000 | $240,000 | $45,000 | $60,000 |

| GDS | $770,000 | $80,000 | $830,000 | $30,000 | $530,000 | $50,000 |

| ACMR | $4,830,000 | $40,000 | $6,100,000 | $40,000 | $4,170,000 | $50,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).