Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Glossary Table

- Reflex Tier — fastest safety-critical control with hard deadlines (Control).

- Reflex Island — isolated near-sensor partition executing the Reflex Tier (Platform).

- Reflex substrate (spintronic/CMOS) — technology implementing the Reflex Tier (Platform).

- Policy Tier — slower mapping/planning; publishes goals to Reflex (Control)

- FFI (freedom-from-interference) — faults/jitter in Policy can’t affect Reflex (Safety).

- ASIL allocation — ISO 26262 safety level assignment per function (Safety).

- DGC (Discontinuous Gas Exchange) — Closed–Flutter–Open; analogy for idle I/O gating (Biology↔Firmware).

- Thermal debt — required cool-down after a burst (Thermal).

- Set-point temperature — maintained flight-muscle band during work (Thermal/Biology).

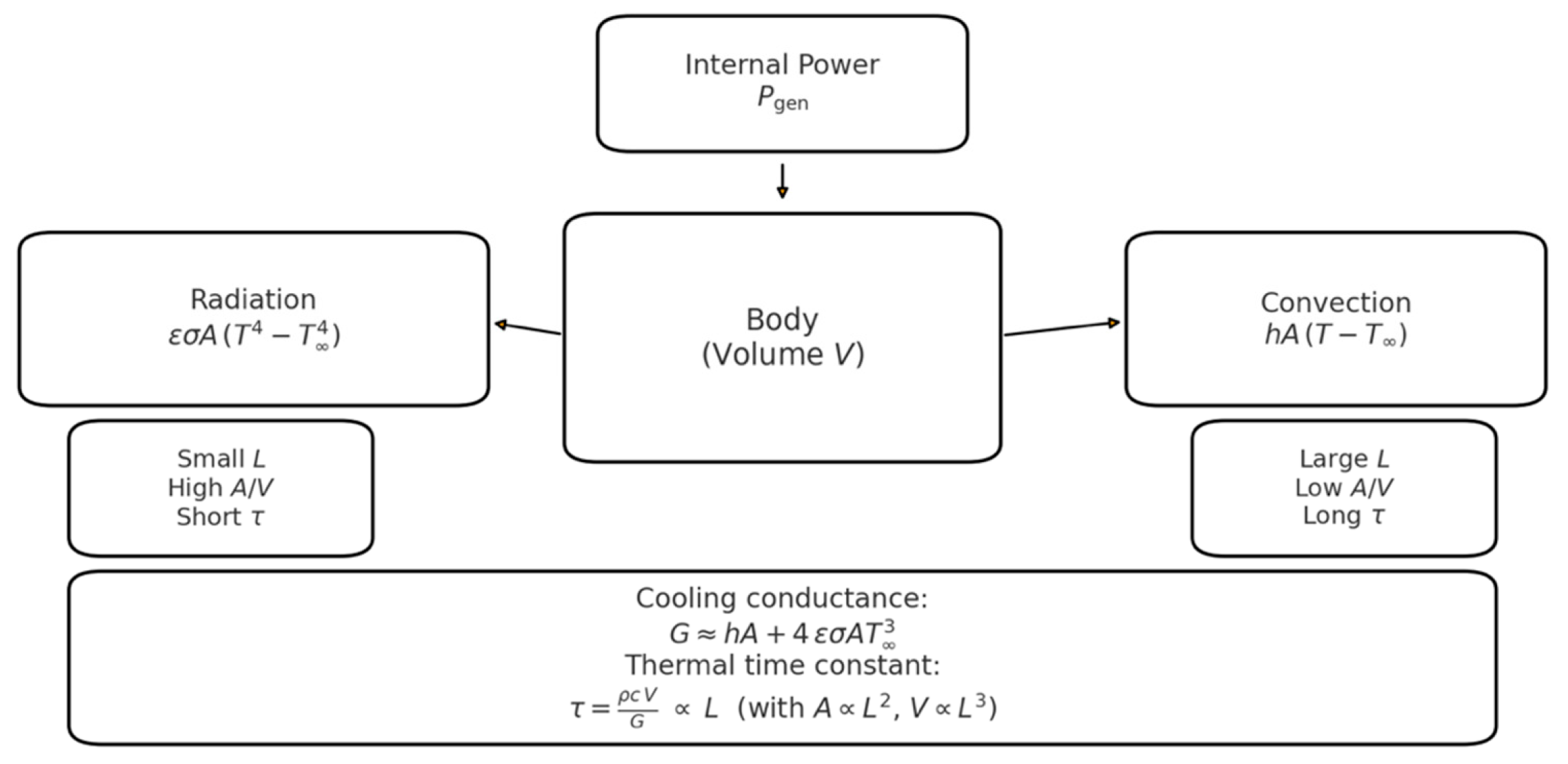

- Cooling conductance G — linearized convection + radiation loss (Physics).

- Thermal time constant τ — response time; scales roughly with size (Physics).

- Prime mover — fuel engine/turbine kept at efficiency island (Propulsion).

- Cold-to-idle latency — light-off to usable idle time (Propulsion).

- BSFC map — brake-specific fuel consumption vs rpm/load (Efficiency).

- Injection event (micro-injection) — one pulse in a split injection (Engines).

- Thoracic shivering — pre-flight warm-up of flight muscles (Biology/Thermal).

- Optic flow — wide-field visual motion cue (Sensing).

- Halteres — gyroscopic sensory organs in Diptera (Sensing).

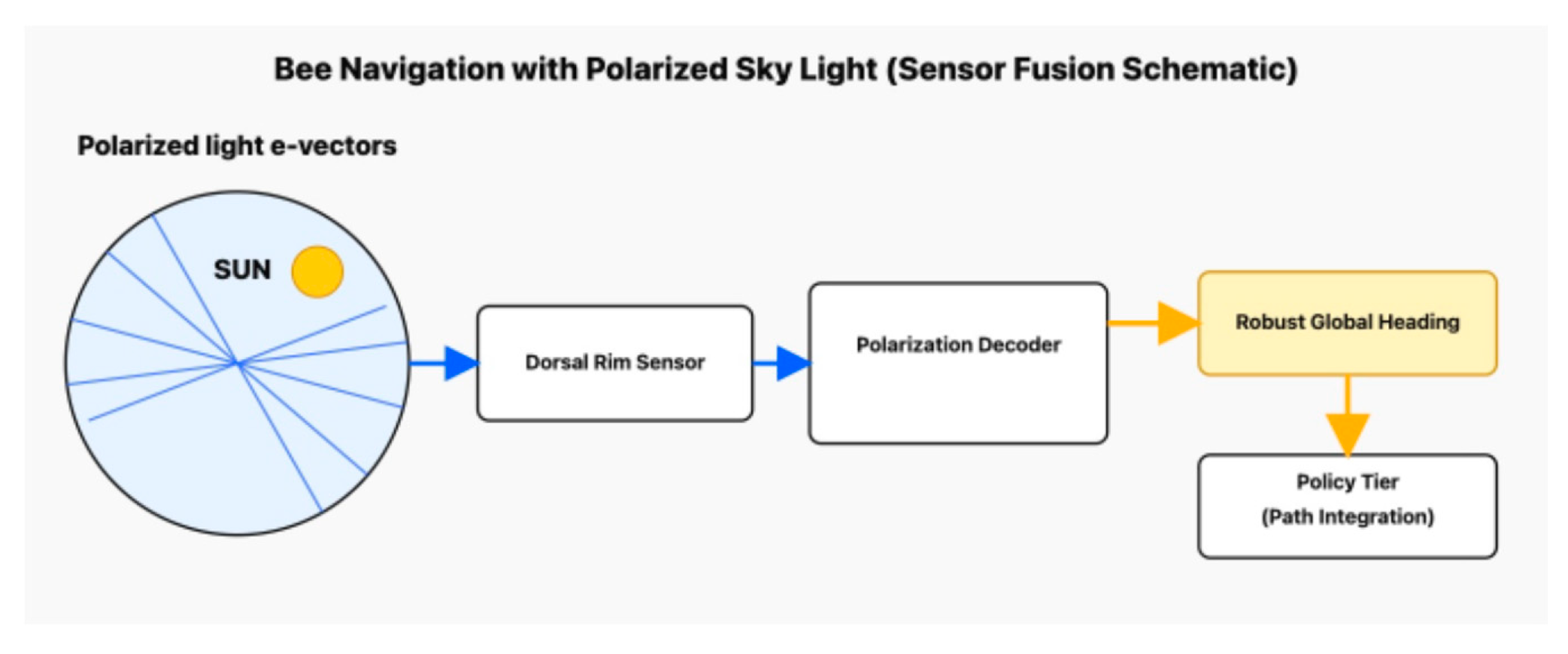

- Dorsal Rim Area (DRA) — polarization-sensitive zone for celestial compass (Sensing).

- Central Complex (ring attractor) — neural compass with an activity bump (Control/Biology).

- CPG (central pattern generator) — rhythmic actuation circuit (Control/Biology).

- STNO reservoir — spin-torque oscillator network for temporal processing (Hardware).

- MRAM synapse — non-volatile weight (MTJ) for instant-on reflex (Hardware).

- DVFS — dynamic voltage/frequency scaling under thermal control (Platform).

- WCET envelope — worst-case execution-time budget from sensor exposure to actuator update, including safety margin, defined per Reflex loop (Timing/Safety).

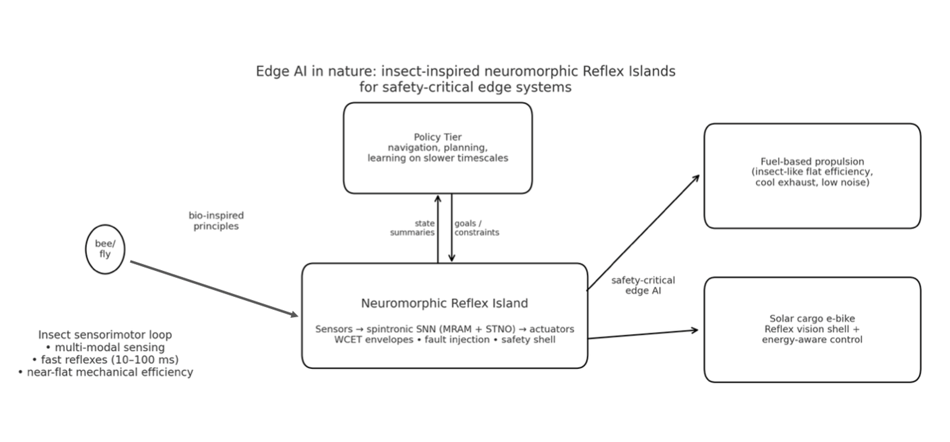

1. Introduction: Insects as Canonical Edge-AI Systems

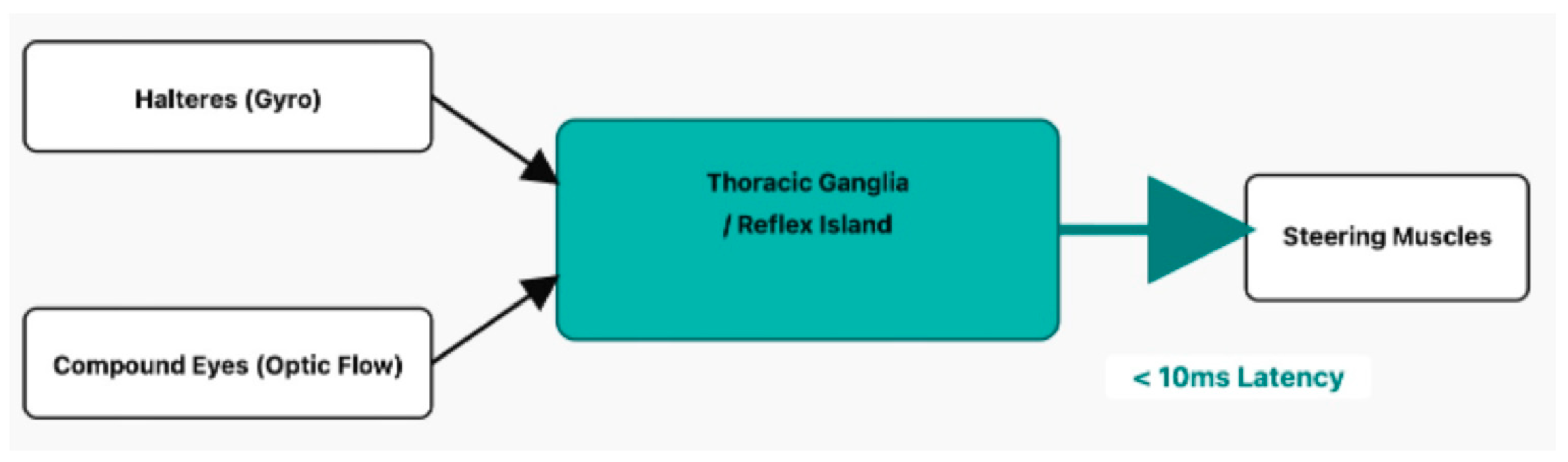

1.1. The Fly (Stabilization Specialist)

- Sensing: The halteres detect angular velocity via Coriolis forces, while the compound eyes detect wide-field optic flow.

- Compute (Fusion): These two streams are fused in thoracic reflex loops, creating a complementary filter where halteres handle fast perturbations and vision handles slow drift.

- Actuation: The resulting error signal directly modulates the phase and amplitude of tiny steering muscles, making micro-adjustments at each wingbeat to stabilize attitude.

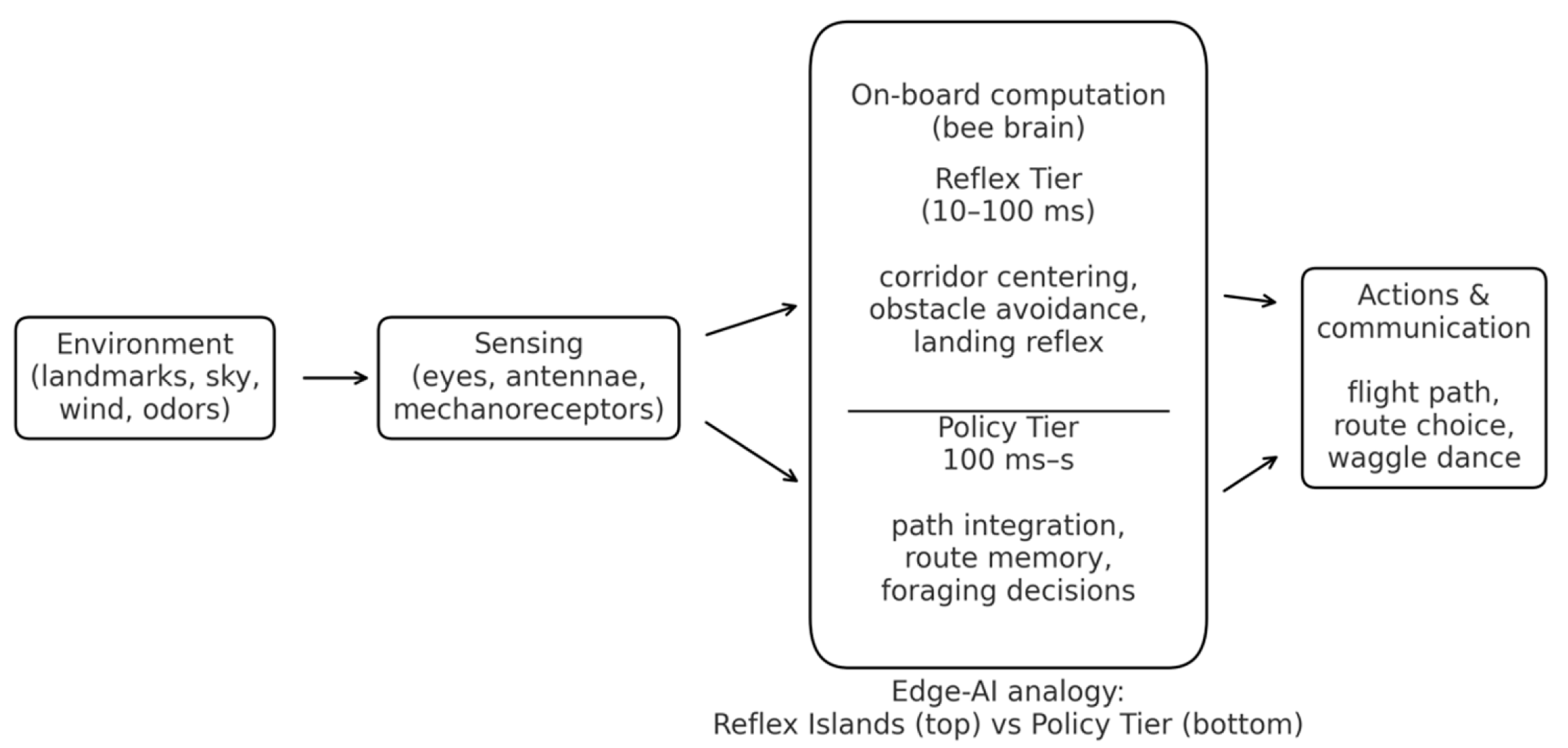

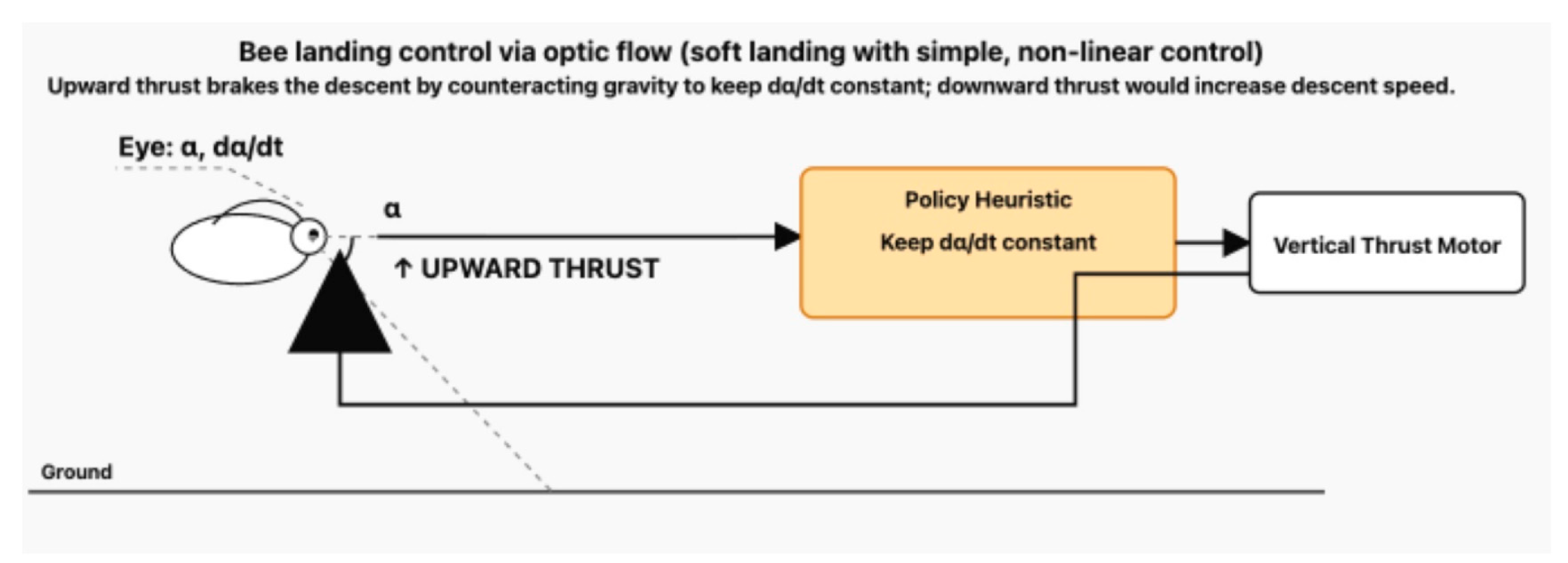

1.2. The Bee (Navigation and Task Specialist)

- Policy: The bee's control policy is a simple heuristic: "Modulate thrust to keep the optic expansion rate constant."

- Actuation: If expansion is too fast, the bee increases thrust; if too slow, it decreases thrust.

- Compute (Integration): Specialized neural circuits integrate the e-vector orientation to maintain a stable global heading, even when the sun is obscured.

- Policy: This stable heading signal feeds into the Policy Tier (Central Complex) to bias the path integration and course selection, providing a low-cost, long-range compass.

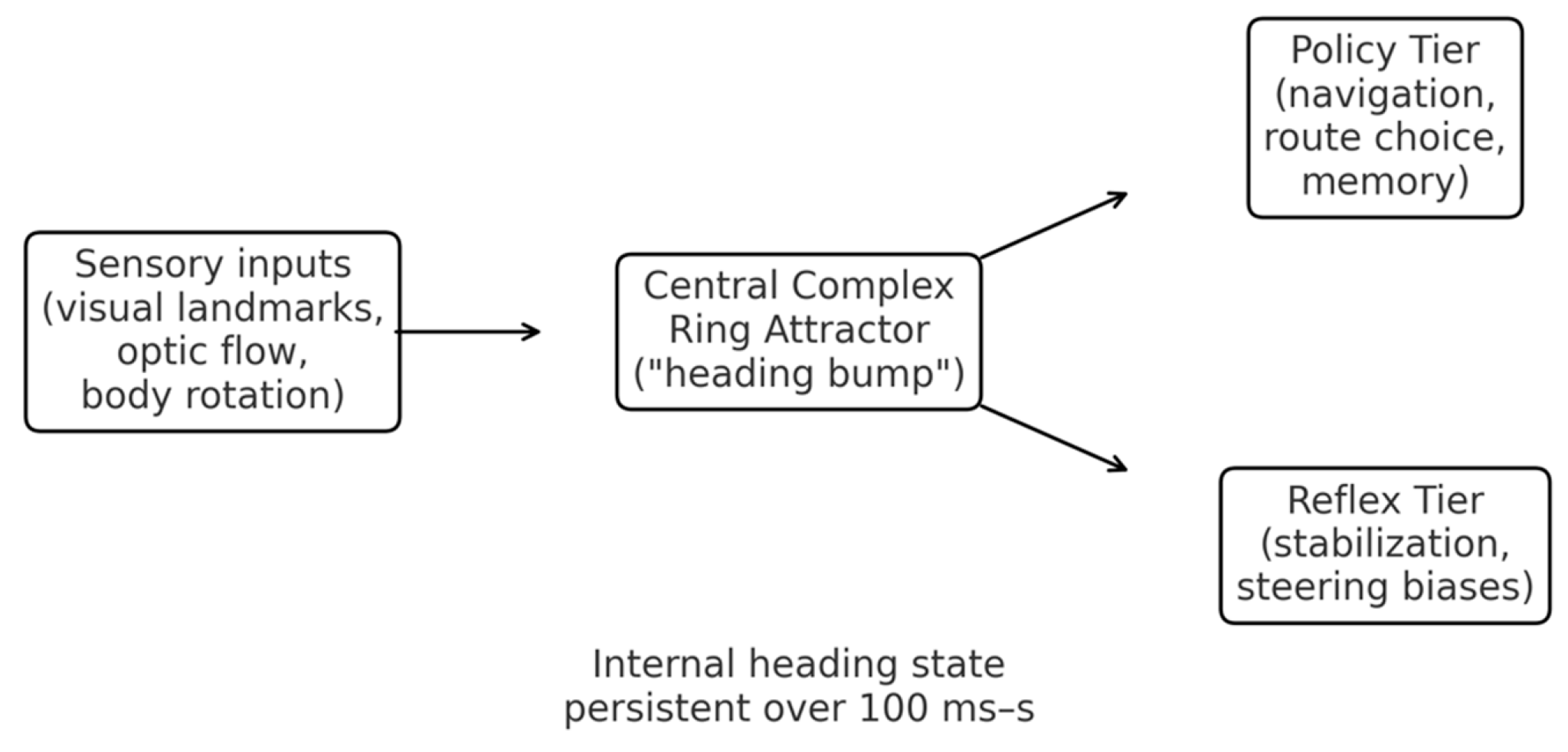

- Sensing/Input: Visual and proprioceptive inputs (e.g., optic flow, haltere signals) provide cues about angular velocity and landmarks.

- Compute (Ring Attractor): The Central Complex (specifically the Protocerebral Bridge) implements a recurrent neural network known as a ring attractor.

- This circuit maintains a persistent "bump" of activity that represents the animal's current heading.

- Policy: The position of the bump acts as a stable, internal state variable, a heading set-point that biases downstream motor reflexes, separating the high-level goal (direction) from low-level execution (torque).

2. Latency-First Architecture (Biology → Engineering)

- a fast Reflex Tier, co-located with sensors and actuators, responsible for stabilization and immediate safety, with tight worst-case execution-time (WCET) envelopes; and

2.1. Two-Tier Control: From Biological Hierarchy to WCET Envelopes

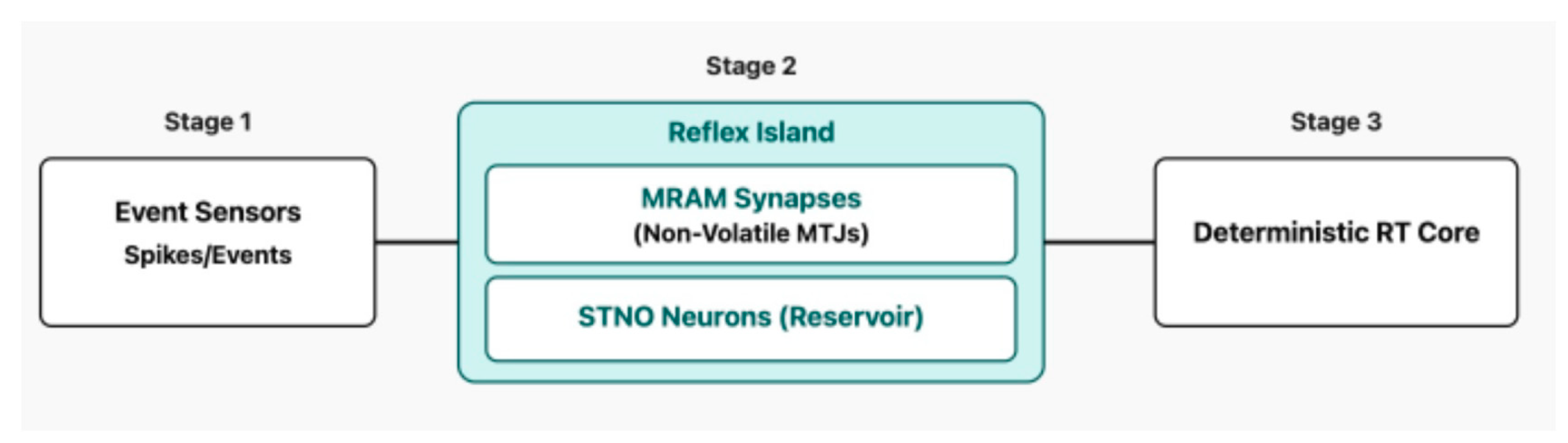

- The Reflex Tier corresponds to the haltere–thoracic loops of flies or the optic-flow landing controller of bees: short-path circuits that transform a small set of sensor streams into actuator commands within microseconds to milliseconds, handling stabilization, collision avoidance and other “must-not-miss” reactions. In our engineering instantiation this becomes a Reflex Island (typically a neuromorphic/spintronic partition) placed physically near sensors and drivers, with hard deadlines and minimal internal state.

- The Policy Tier corresponds to the central complex and mushroom bodies: circuits that integrate many cues, maintain internal state (e.g. head-direction bumps, value associations), and shape behaviour over tens to hundreds of milliseconds and beyond [5,6,7,8,9]. In engineering terms this is a real-time core, NPU or small cluster that runs mapping, heuristics and learning, and emits only goal states (speed corridors, thrust limits, route waypoints) to the Reflex Tier [4,5,10,11].

- The Reflex Tier (µs–ms) is located as close as possible to sensors and actuators; it runs on a pinned core or dedicated neuromorphic/spintronic die, uses fixed-priority scheduling, no dynamic memory, and one-way, lock-free single-producer/single-consumer queues for communication. It is the only place where plant-stabilizing loops (thrust, torque, braking, steering) are closed.

- The Policy Tier (ms–s) runs at lower priority on separate cores or tiles; it may use more complex software stacks, but its influence on the plant is strictly mediated through low-rate set-points and mode flags. Faults or jitter in Policy must not be able to delay or pre-empt Reflex work (FFI).

- co-locate sensors, Reflex compute and drivers;

- wire interrupt → DMA → neuromorphic Reflex → RT core → PWM/FOC in a fixed pipeline;

- keep end-to-end stabilization loops below ≈5 ms, with the most critical safety paths below 1 ms; and

- expose only goal states upstream, not raw sensor streams or inner-loop variables.

| Stage | Function (example stack) | WCET (µs) | Cumulative (µs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DVS/IMU exposure → interrupt assertion | 50 | 50 |

| 2 | DMA + time-stamp + spike encoding into Reflex Island | 150 | 200 |

| 3 | FF-SNN layer 1 (elementary motion detectors) | 800 | 1,000 |

| 4 | STNO reservoir / RSNN update + readout | 1,200 | 2,200 |

| 5 | Reflex decision logic + watchdog comparators | 400 | 2,600 |

| 6 | RT core arbitration, FOC current reference update | 400 | 3,000 |

| 7 | PWM/timer update + gate-driver propagation | 400 | 3,400 |

3. Neuromorphic and Spintronic Hardware

3.1. Why Neuromorphic Matches the Insect Edge

- a feed-forward SNN (FF-SNN) front-end that performs rapid event filtering and early feature extraction (e.g. elementary motion detectors for optic flow, looming detectors for collision), and

- a small recurrent SNN / reservoir that integrates multiple modalities (e.g. visual flow + inertial signals) and implements the stateful part of the reflex (e.g. complementary filters, phase-locked loops, simple internal variables).

3.2. Spintronic Primitives as "Physical Synapses and Neurons"

- 1)

- ○

- Instant-on innate memory. The Reflex network’s weights persist with no standby power. When an event arrives, say, from an event camera or IMU, the island is ready to respond immediately, with no DRAM refresh or flash warm-up. This mimics biological “innate reflexes” that are present and usable as soon as the organism is awake.

- ○

- Energy efficiency and robustness. Eliminating continuous refresh and long erase/program cycles reduces energy and simplifies timing analysis, because memory access times are stable across the device’s lifetime.

- 2.

- STNO neurons / reservoirs. Spin-Torque Nano-Oscillators (STNOs) are nanoscale magnetic oscillators that can operate at GHz frequencies and exhibit rich, nonlinear dynamics [10,15,16,56]. When coupled into networks, they form physical reservoirs that process temporal streams (e.g., IMU, event camera outputs) by mapping them into high-dimensional, time-varying patterns. Readout circuits then learn simple linear or shallow nonlinear combinations of these patterns to implement the required reflex mapping. This is closely aligned with tasks such as optic-flow analysis, vibration-based anomaly detection, or haltere–visual fusion, where temporal structure matters at sub-millisecond scales.

- Sensing: Event streams from sensors (e.g., event cameras, IMU) are converted into spikes (electrical pulses).

- Compute (MRAM Synapses): Magnetic Tunnel Junctions (MTJs) in MRAM act as non-volatile synapses, storing neural network weights directly where they are used. This enables instant-on capability and near-zero standby power, emulating innate memory and reflexes.

- Compute (STNO Neurons): Spin-Torque Nano-Oscillators (STNOs) act as compact, high-frequency (GHz) spiking neurons. They can form reservoirs for processing temporal tasks and sensorimotor transformation, such as optic flow analysis.

- Actuation (RT Core): The output (set-points) of the spintronic SNN feeds a deterministic Real-Time Core (RT Core) that performs final control (PID/LQR) and drives the actuators.

4. Thermoregulation, Frequency Control, and “Natural Engine” Analogies

4.1. Discontinuous Gas Exchange (DGC) and Idle I/O Gating

- Closed ≙ deep idle. All non-essential interfaces are off; only an ultra-low-power time base or simple wake-up detector (e.g., RTC, threshold comparator) remains active. No sensor data are streamed; no neuromorphic or RT core is clocked.

- Flutter ≙ duty-cycled health checks. Short, low-duty bursts of sensing and computation verify liveness and environmental state: a brief sensor read, a minimal anomaly detector run, then return to Closed if nothing demands action. Total average duty cycle is kept very low, analogous to the low spiracle duty factor in DGC.

- Open ≙ full bandwidth on demand. When a relevant event is detected, e.g., a looming obstacle, threshold overshoot, or external wake-up, the system transitions to full-rate sensing and Reflex processing, analogous to the Open phase’s full spiracle opening.

- Sensor interfaces (camera, IMU, pressure, acoustic): event-driven or frame-based acquisition is fully off in Closed, lightly sampled in Flutter, and fully active only in Open.

- Neuromorphic Reflex Islands: synaptic weights remain resident in MRAM, but neuron arrays and on-chip routing are clock-gated except during Flutter or Open windows.

- Policy Tier: can remain entirely off in Closed and much of Flutter, only waking when the Reflex Tier raises a “need context” flag.

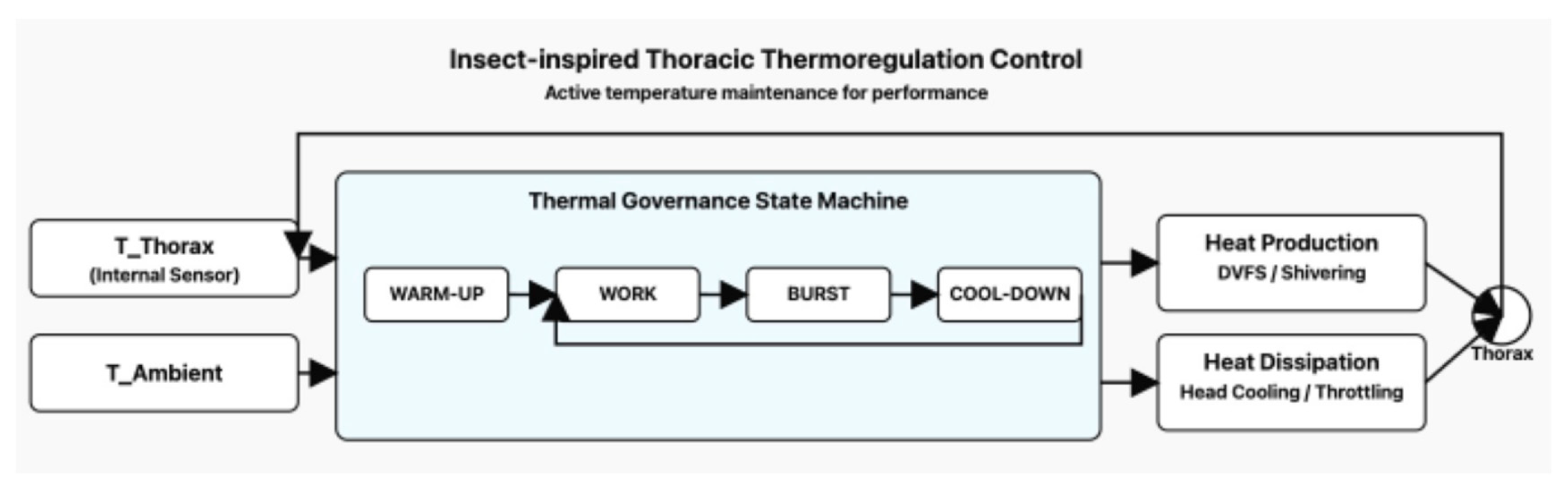

4.2. Thermal Governance as a State Machine

- REST. All but the most basic sensing (e.g., temperature/voltage monitors) and Reflex loops are quiescent; the system tracks ambient temperature and internal temperature but generates little heat.

- WARM-UP. On a demand for performance (e.g., activation of a thruster or high-load compute), the system proactively raises the temperature of the critical component cluster (e.g., neuromorphic/spintronic die, power stage) towards a set-point where timing and efficiency are optimal, analogous to shivering thermogenesis in bees [21,22,23].

- WORK. The system operates within its continuous-power envelope: clocks and currents are chosen so that average power dissipation does not exceed steady-state cooling capacity; temperature hovers near the set-point.

- BURST. For short intervals, the system is allowed to exceed its steady-state thermal budget—e.g., higher current to actuators or boosted compute frequency, drawing on the thermal capacitance of the hardware stack. The allowable burst duration depends on a simple lumped thermal model (time constant τ) and the current thermal debt (difference between current temperature and set-point), as worked out explicitly in Section 4.3.

- COOL-DOWN. After a burst, loads are reduced and cooling (convection, conduction, fan speed) is increased to “repay” thermal debt and return to the set-point without overshoot.

- FAULT-SAFE. If temperature approaches a critical limit Tcrit despite COOL-DOWN actions—or if sensors fail—the system enters a safe state: Reflex safety loops remain alive, but all non-essential Policy and high-power functions are shed.

4.3. Why Thermoregulation Tightens at Small Scale (Black-Body + Convection)

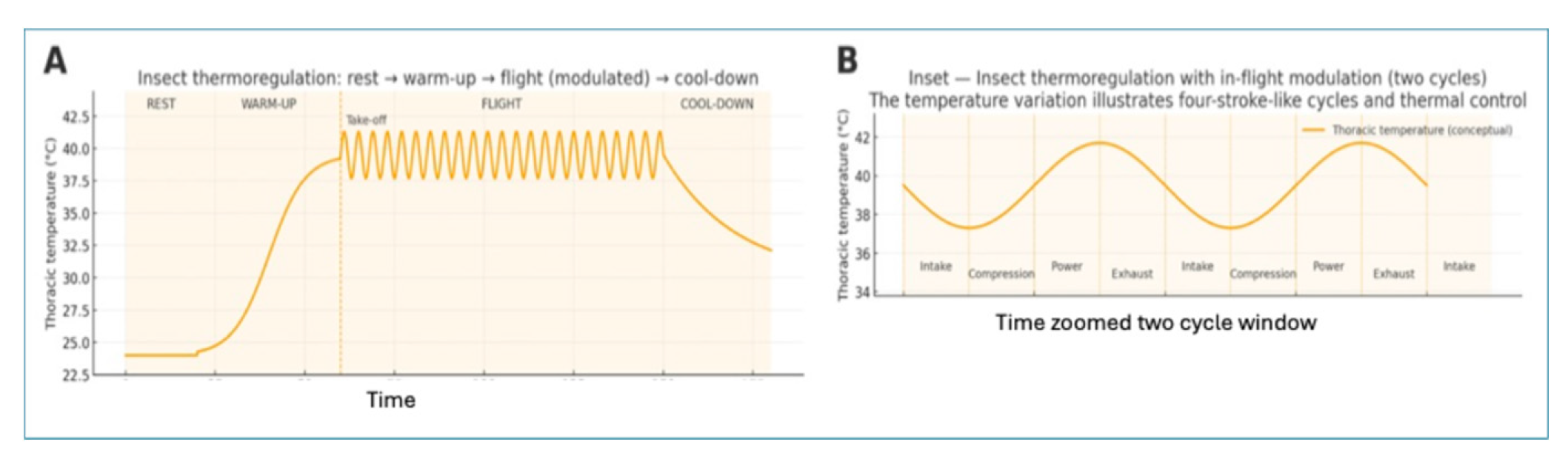

4.4. A Four-Stroke “Natural Engine” for Insect Thermoregulation

- WARM-UP (Compression). Shivering thermogenesis in the flight muscles raises thoracic temperature towards a narrow performance band (≈30–40 °C in bees), while the head is kept relatively cooler to protect neural timing [21,22,23]. This corresponds to building up “thermal pressure” before high-power operation.

- WORK / BURST (Power). Wing actuation now couples mechanical work to ventilation and evaporative cooling. As flight intensity increases, both convective and evaporative heat export scale with effort, helping to hold the thorax near its set-point despite higher internal Pint [21,22,23,24]. This is the main “power stroke” where muscle efficiency remains near optimal while output power is modulated primarily by wingbeat frequency and stroke (Section 4.5).

- Sensing: Thoracic temperature (for power output) and ambient temperature are monitored.

- Compute (Control): A central control mechanism (analogous to a firmware state machine) actively regulates heat production (e.g., shivering) and heat dissipation (e.g., head cooling/evaporative cooling) to maintain a performance-optimal thoracic temperature set-point.

- Engineering Analogy: This is mirrored by an Edge AI system's thermal governance, which uses a state machine to dynamically adjust power/clock frequency (DVFS) and sensor duty cycles based on thermal sensors and predicted load, allowing for short, high-performance bursts while preventing thermal runaway.

4.5. Propulsion Analogy: Injection/Wingbeat Frequency and Efficiency

- in Section 4.5.1 we recall that modern common-rail engines already operate their injectors at command frequencies in the same 10²–10³ Hz decade as insect wingbeats;

- in Section 4.5.2 we note that insect wingbeat frequency itself lives in that same band, but arises from asynchronous muscle and thorax resonance rather than a central clock; and

- in Section 4.5.3 we compare efficiency maps of conventional engines and miniturbines against insect flight muscle, motivating the “flat-band, frequency-governed” behaviour we seek in insect-inspired thrusters.

4.5.1. Injection Event Frequency in ICEs

- per cylinder: ;

-

aggregate: .At 2000 rpm with the same

- per cylinder: ;

- aggregate: .

4.5.2. Wingbeat Frequency in Insects

- neural spikes gate contractions and set overall activation level,

- achieve high wingbeat frequencies with modest neural bandwidth and energy per spike,

- modulate power output primarily by changing frequency and stroke amplitude within a thermally managed band, and

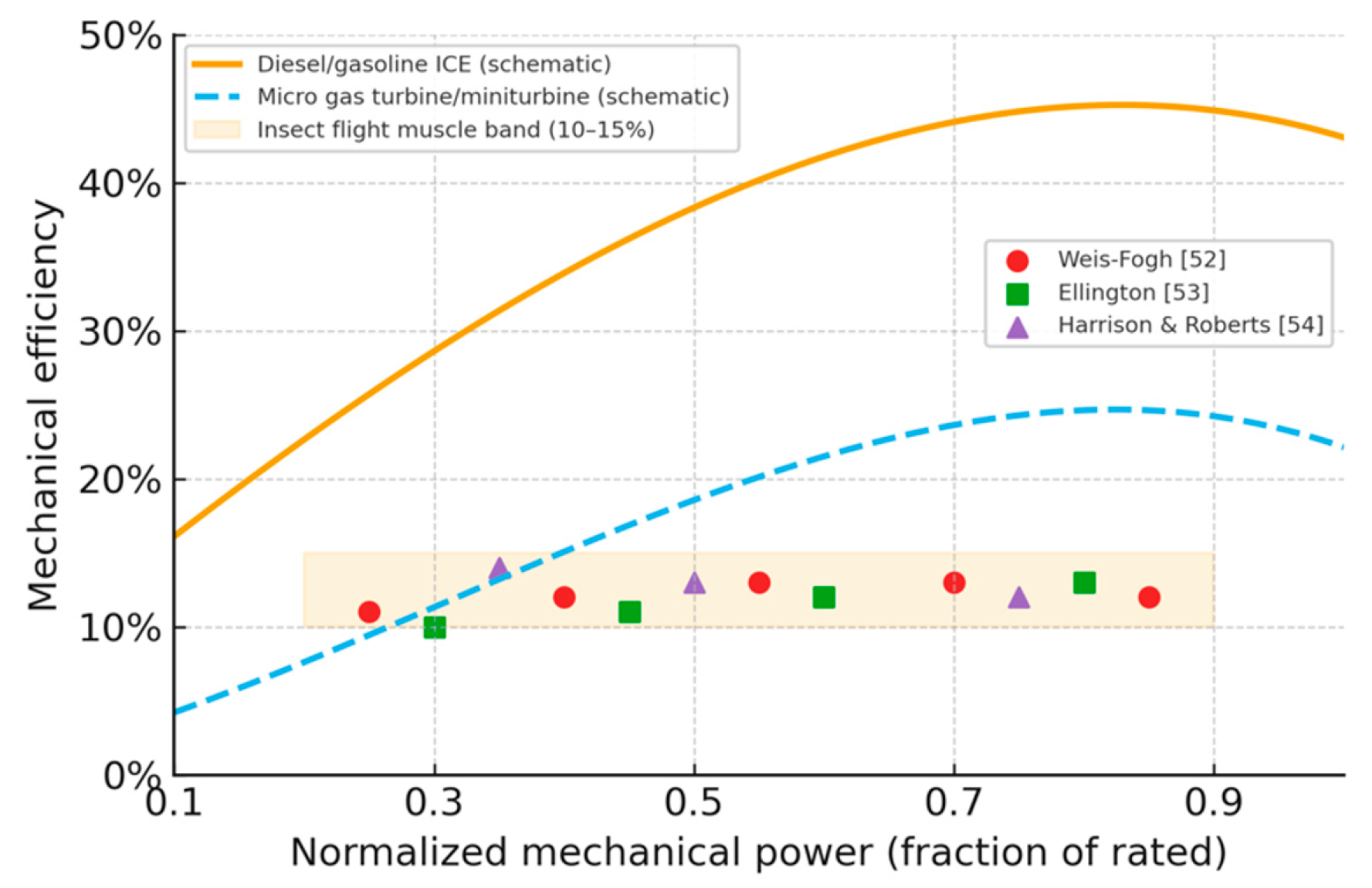

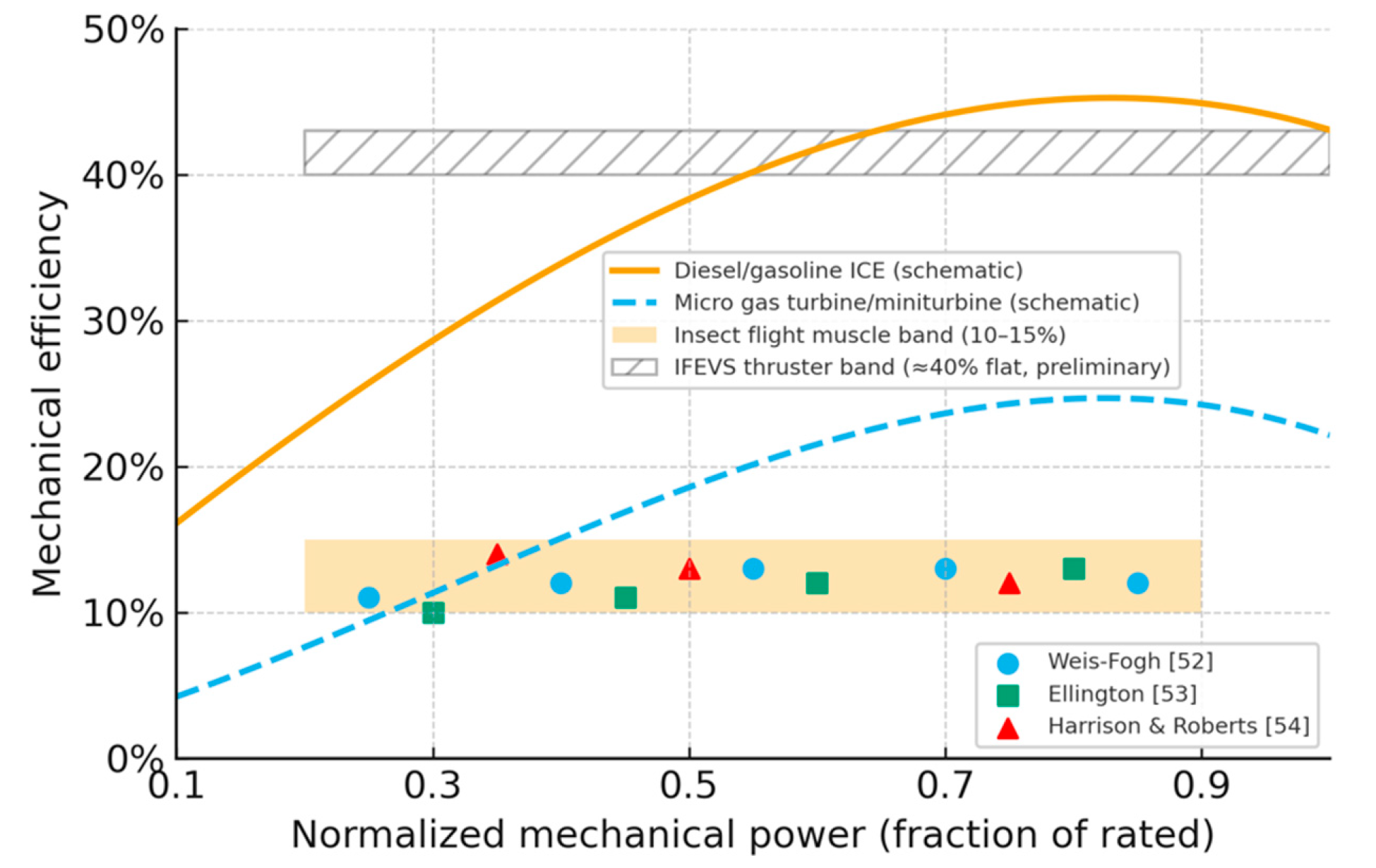

4.5.3. Efficiency Maps: Narrow Islands vs Near-Flat Bands

- Engines and miniturbines: high peak efficiency (≈40–45% for modern diesel; ≈20–25% for 200–400 N miniturbines) but confined to narrow islands in normalized power, with steep penalties at low load and noticeable degradation at the extremes.

- Insect flight muscle: lower absolute efficiency (10–15%), but comparatively weak load dependence over the biologically relevant range; small excursions at very low or very high loads, but no sharp peak like in ICEs.

4.6. Miniturbines: Scaling Limits, High rpm, and Cold-Start Latency

- Low peak efficiency at relevant scales. In the 200–500 N thrust range, typical microturbines achieve only ≈20–30% thermal efficiency at or near their design point [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Combined with partial-load penalties, this translates into fuel burn significantly higher than that of best-in-class piston engines at the same useful power [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

- Narrow best-efficiency island. As in larger Brayton machines, microturbines exhibit a narrow efficiency peak as a function of shaft speed and load. Operation at 30–50% of rated thrust can see efficiency degrade by tens of percent relative to the peak, exactly the regime where loiter, approach and partial-power climb occur. By contrast, insect flight muscle maintains mechanical efficiency in a relatively flat 10–15% band across its useful range (Section 4.5.3, Figure 9) [32,33,34,35,52,53,54].

- Cold-start and spool-up latency. From cold, microturbines require seconds to tens of seconds for safe ignition, acceleration and thermal stabilisation before usable power is available, and even from warm idle, spool-up to high thrust takes hundreds of milliseconds to seconds depending on inertia and control laws [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Insect flight, by contrast, is limited primarily by warm-up of the thorax (shivering) and then operates with cycle-by-cycle power modulation via wingbeat frequency, with effectively zero “spool-up” once airborne (Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4).

- Hot, high-speed exhaust. Microturbines typically exhaust gas at 500–1000 °C at high jet speeds, with acoustic signatures dominated by high-frequency components and potential ingestion risks in distributed configurations [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Insects, by contrast, exhaust metabolic heat via moderate temperature differentials and relatively low-speed convective and evaporative flows (Section 4.4).

- Efficiency is not flat across the useful thrust range.

- Burst capability is constrained by the thermal and mechanical inertia of the rotor and casing.

- Spool-up latency conflicts with the idea of “instant-on” Reflex behaviour that can support rapid manoeuvres, hopping or emergency climbs.

- The prime mover (piston engine, IFEVS thruster core, fuel cell, etc.) is operated as a “natural engine”: kept near its optimal efficiency band by thermal governance and modest power modulation (Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4).

- The distributed propulsors (electric fans, propellers, pumps, pumps-jets) are driven via electrical or mechanical power distribution networks and handle fine-grained thrust vectoring, redundancy and control authority.

- Flat-band operation of the prime mover. By designing the thermal core (e.g. an IFEVS thruster) to operate at nearly constant efficiency over a modest range of power and then using frequency or duty-cycle modulation in the electric propulsors to shape net thrust, we align hardware behaviour with the insect efficiency plateau of Figure 9 [32,33,34,35,52,53,54]. The prime mover stays in its sweet spot; the “wings” do the dynamic work.

- Fast thrust response with slow thermal dynamics. Electric propulsors respond on millisecond timescales; their Reflex loops can be implemented as neuromorphic Reflex Islands with tight WCET envelopes (Section 2, Section 3). The prime mover can ramp more slowly to follow envelope constraints and thermal budgets (Section 4.2 and Section 4.3) without compromising manoeuvre agility. This is directly analogous to insects: muscles and thorax temperature change slowly, but wingbeat frequency and stroke can change cycle-by-cycle.

- Compatibility with distributed propulsion and VTOL/eSTOL. Multiple small propulsors, arranged in wings, rings, ducts or matrices, can be controlled independently, enabling fault tolerance, smooth transitions between VTOL and eSTOL modes, and advanced noise management. Because each propulsor deals with relatively cool, low-speed flow, the integration challenges are closer to those of electric distributed propulsion (DEP), even if the upstream energy source is fuel-based [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

- Clear safety interfaces. The Reflex/Policy architecture maps naturally onto this hybrid setup. Each propulsor node has a local Reflex Island that guarantees basic stability and fast reaction to failures (loss of a rotor, gusts, sensor dropouts). A small number of central Reflex nodes supervise the prime mover and power distribution, enforcing thermal and power envelopes. On top of this, a Policy Tier runs guidance and mission logic. Shared safety envelopes, thermal, power and thrust, are implemented as explicit burst budgets and WCET guarantees (Section 2, Section 4.2–Section 4.3), rather than as implicit controller tuning.

4.7. Thermal-Debt ODE and Burst Budgets for Engineered Systems

- compute offline (with conservative parameter choices for );

- store the resulting burst budget curve (or a coarse table) in the Reflex Island; and

- have the thermal state machine consult this budget before admitting a new BURST, updating it online using the measured thermal debt

- Reflex loops maintain stabilisation and basic control even as BURST entry is denied when thermal margins vanish;

- the Policy Tier may propose trajectories or manoeuvres that would exceed the burst budget, but these are rejected or degraded by the Reflex layer if Tdebt is too high;

- faults in temperature sensors or thermal models drop the system into a conservative mode (e.g. disallow BURST, limit continuous power).

5. Use Cases and Actionable Guidance for Adoption

5.1. Insect-Inspired Fuel-Based Thruster (IFEVS) as a Conceptual Case Study

5.1.1. Concept and Relation to the Insect Template

- a fuel-burning core with no high-speed rotating machinery, where combustion is organised to favour high static-pressure recovery and moderate jet velocities;

- a compact augmenter/ejector, which entrains and accelerates ambient air, trading jet speed for mass flow and static pressure recovery; and

- a set of distributed exhaust ports that can be vectored or integrated into lifting or propulsive surfaces.

5.1.2. Thermal Efficiency and Flat-Band Behaviour (Model-Based)

- Core thermal efficiency varies only weakly with thrust, as long as temperature and pressure ratios are held within their designed operating window.

- The augmenter converts high-velocity core flow into higher mass flow and static pressure with relatively modest additional losses.

- Duty-cycle and “stroke” (e.g., pulsation frequency of the core, modulation of injection) modulate net thrust without materially degrading the underlying thermal conversion efficiency, as long as operation stays within the continuous WORK region of the thermal state machine.

5.1.3. Comparison with Microturbines at Equal Thrust (Table 5.1)

- the IFEVS thruster operating at several nominal thrust levels (50 N steps from 50 N up to 600 N), and

- the corresponding JetCat P400 and P550 microturbines after accounting for their augmenters and typical partial-load behaviour.

- the reference microturbine thrust and fuel flow (mL·min⁻¹) based on manufacturer data and standard scaling;

- the IFEVS thruster fuel flow at the same net thrust, according to the current cycle model; and

- the fuel-flow ratio .

- Around a 400 N design point, the IFEVS thruster uses roughly half the fuel of a state-of-the-art microturbine at equal net thrust.

5.1.4. Exhaust Temperature, Acoustic Signature and Distributed Propulsion

- The exhaust Mach number is kept subsonic at the outlet, which suppresses shock-associated noise and high-frequency components.

5.1.5. Integration with Neuromorphic Reflex Islands and Distributed Propulsion

- The thruster’s thrust is modulated primarily by frequency and duty-cycle control of fuel injection and augmenting flows, with time constants compatible with millisecond-range neuromorphic controllers. There is no heavy rotor inertia to “spool up” as in a turbine, so near-instant thrust modulation becomes feasible.

- MRAM-based Reflex Islands can host the core thrust and thermal-governance logic, with non-volatile weights and parameters enabling fast restart, deterministic timing and robust over-the-air updates (A/B images, safe rollback), as discussed in Section 3.2.

- In a distributed propulsion system, multiple IFEVS modules or a single IFEVS core feeding several electric propulsors can be controlled by a lattice of Reflex Islands, each responsible for local thrust vectoring, envelope protection and burst-budget enforcement.

5.1.6. Safety and Certification Hooks: Proposed Strategy

- Fault taxonomy. We consider permanent and transient faults across sensors (pressure, temperature, flow, vibration), compute (neuromorphic/spintronic Reflex Islands, RT cores) and actuators (valves, injectors, drivers). Fault modes include stuck-at, drift, noise bursts and timing violations.

- Reflex/Policy partitioning. All safety-critical control—inner thrust loop, thermal burst budget enforcement, envelope protection (over-thrust, over-temperature, over-pressure)—is executed on Reflex Islands and dedicated RT cores with explicit WCET envelopes (Section 2.1, Table 2.1). Policy-level functions (mission planning, optimization) are treated as non-safety-critical and cannot pre-empt Reflex work.

- Fault-injection campaigns. We envisage systematic transient fault injection targeting MRAM synapses, spintronic oscillators and communication paths, and policy/reflex-boundary violations (e.g., corrupted set-points) to verify that faults are either masked or drive the system into a safe degraded mode.

5.1.7. Example Validation Path and Open Data

- Component-level tests. Calibrated measurements of injectors, combustion chambers, augmenters and nozzles: pressure ratios, flow coefficients, loss factors, noise spectra. These feed into the cycle model used for the estimates in Section 5.1.2, Section 5.1.3 and Section 5.1.3.

- Sub-scale thruster rigs. Construction of a stationary test rig with well-instrumented thrust stand (load cells), fuel metering, and thermocouple arrays. Measurement of thrust, fuel flow, exhaust temperature, noise, and transient response under controlled ambient conditions.

- Model validation and uncertainty quantification. Use the rig data to validate and refine the cycle model; quantify uncertainties (e.g., ±5 percentage points on efficiency, ±5–10% on fuel-flow ratios) and propagate them into mission-level assessments.

- Integrated Reflex-Island controller tests. Hardware-in-the-loop and then engine-in-the-loop experiments where neuromorphic/spintronic Reflex Islands implement the thrust and thermal controllers under fault injection and timing analysis.

- Flight-like demonstrations. Limited-flight or wind-tunnel tests of distributed thruster arrays under representative mission profiles (hover, climb, cruise, approach), including time-series plots of thrust, fuel, exhaust temperature and noise.

5.1.8. Status, Limitations and Role in This Roadmap

- All efficiency and fuel-consumption figures in Section 5.1.2 and Section 5.1.3 are model-based engineering estimates, informed by subsystem tests but not yet by a full end-to-end thruster campaign.

- We report efficiency as ~40% ± 5 percentage points and fuel-saving ratios as indicative (≈½ at 400 N, down to ≈⅓ at low thrust); these values may shift as the model and rig data are refined.

- Noise, exhaust temperature and transient-response claims are similarly preliminary, based on component-level measurements and simulations, and are presented here to show direction of travel rather than to define product specifications.

- flat-band efficiency inspired by insect flight muscle,

- thermal governance and burst budgeting inspired by insect thermoregulation and DGC, and

- neuromorphic/spintronic Reflex Islands providing the safety-critical control shell.

5.1.9. Insect-Inspired Fuel-Based IFEVS Thruster: Synthesis and Outlook

| Thrust (N) | IFEVS fuel (mL/min) | P400 fuel (mL/min) | Fuel ratio IFEVS / P400 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80 | 143 | 391 | 0.37 |

| 120 | 215 | 507 | 0.42 |

| 160 | 287 | 623 | 0.46 |

| 200 | 358 | 739 | 0.48 |

| 240 | 430 | 855 | 0.50 |

| 280 | 502 | 971 | 0.52 |

| 320 | 573 | 1087 | 0.53 |

| 360 | 645 | 1203 | 0.54 |

| 400 | 717 | 1319 | 0.54 |

| 440 | 788 | — | — |

| 480 | 860 | — | — |

| 520 | 932 | — | — |

| 540 | 968 | — | — |

- Model sensitivity to assumed combustor/augmenter pressure losses and mixing efficiency (≈±3–4 percentage points on thermal efficiency).

- Instrumentation accuracy of mass-flow and temperature measurements in current rigs (≈±2–3% on flow and temperature, dominated by calibration and alignment).

- Variability in augmenter entrainment ratio and back-pressure (≈±0.05 on thrust multiplication).

- Ambient deviations from ISA sea-level static (≈±5% density variation over a 10–15 °C swing).

- an insect-style prime mover whose efficiency degrades gently with load instead of collapsing away from a narrow BSFC island;

- instantaneous thrust response, limited by valves and ignition rather than seconds-scale spool dynamics;

- cool, slow exhaust (~150 °C at the augmenter exit) enabling safe operation near people and structures and easing IR/acoustic constraints; and

- a mechanically simple, non-rotating core naturally compatible with the Reflex/Policy split and WCET reasoning of Section 2 and Section 5.1.6.

| Metric | IFEVS thruster (concept) | State-of-the-art microturbine (similar thrust) |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal efficiency (core) | > 40% before augmenter (fuel → jet power) | ~20–30% peak; sharp drop off-design |

| Thrust–load behaviour | Flat efficiency from ~30 N → 600+ N after augmenter | Narrow island; poor partial-load BSFC |

| Fuel use @ ≈400 N | ≈ ½ the fuel of miniturbine (±0.05 ratio) | Baseline |

| Fuel use @ ≈50 N | ≈ ⅓ the fuel vs. turbine at low-load operation (±0.05 ratio) | Strong efficiency loss at low throttle |

| Exhaust temperature | ~150 °C at augmenter exit | ~500–1000 °C EGT; hot jet |

| Acoustic signature | ≤100 dB @ 3 m, subsonic ejector exit | Hot, often supersonic microjets; much louder |

| Response time | Near-instant; no spool-up | Spool-up / light-off delays (seconds) |

| Architecture / maintenance | No rotating parts; ≈½ weight; low maintenance | High-speed rotor/bearings; higher maintenance load |

5.2. Insect-Inspired Neuromorphic Safety Shell for Solar Cargo E-Bikes

- Looming detectors for collision warning (expanding flow fields in image space).

- Corridor-centering and gap-selection modules based on lateral optic flow, helping the rider to maintain safe clearance from parked cars and walls.

- Overtaking and rear-approach detectors, using temporal differences in lateral and rear cameras.

5.2.2. Latency Budget and Reflex Loop WCET

| Stage | Description | WCET (µs) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sensor exposure & read-out | ~1,000–2,000 | Event camera or 200–500 fps rolling-shutter sensor; exposure + read; DMA to buffer |

| 2 | Preprocessing & spike encoding | ~300–500 | Simple spatial pooling / contrast normalisation; frame-to-event conversion |

| 3 | Looming SNN inference | ~1,000–2,000 | Small FF-SNN / reservoir on neuromorphic core; single forward pass |

| 4 | Reflex decision & arbitration | ~100–200 | Thresholding, hysteresis, priority between left/right/ rear channels |

| 5 | Haptic/LED driver command | ~100–300 | SPI / PWM update; driver response |

| Total Reflex WCET | sensor → haptic cue | ≈2.5–5 ms | Worst case at hot electrical corner with guard band |

5.2.3. Energy Budget and Solar Sizing

- A 1 m² panel area mounted on the cargo box roof and side surfaces, using commercial modules of ≈22% efficiency, yields a nameplate power of roughly 200–220 Wp under standard test conditions.

- For mid-southern European latitudes, the annual average insolation on a reasonably oriented surface is on the order of 4–5 kWh·/m²day, with ≈2–3 kWh·/m²day in winter and ≈6–7 kWh/m²day in summer [].

- Assuming 70–80% system efficiency (MPPT + battery charging + wiring) and 1 m² area, the panel can thus deliver roughly 0.6–0.8 kWh/day on average, with summer days often exceeding 1 kWh.

- On the consumption side:

- Typical cargo e-bike propulsion energy falls in the 10–15 Wh/km range depending on speed, load and terrain. For 25–30 km/day, this yields 0.25–0.45 kWh/day for propulsion.

- The neuromorphic safety shell and auxiliary electronics can be designed to stay below 20–30 W average (including cameras, SNN inference, communication), adding another 0.1–0.2 kWh/day for ~5–8 h of operation.

5.2.4. Integration in the Reflex/Policy Architecture and Status

- Reflex Islands on board the bike, implementing looming detection, gap-keeping and basic traction control with millisecond-range WCET envelopes (Section 5.2.2);

- a Policy Tier distributed between the bike (routing, task logic) and the rider (tactical decisions), akin to the bee’s central-complex and mushroom-body functions (Section 1.2); and

- a shared energy and thermal budget that couples propulsion, sensing and compute to the solar harvest and battery state, using the same “thermal/energy debt” reasoning as in Section 4.8.

5.3. Beyond Mobility: Implants and Bio-Sensing as Ultra-Constrained Reflex Islands

- hard energy budgets (years of operation from a small battery or harvested energy);

- strict WCET constraints (e.g., maximum inter-beat latency for pacing, minimum reaction time to arrhythmias or hypoglycaemia); and

- strong freedom-from-interference requirements, since failures can be immediately life-threatening.

- Neuromorphic micro-reflexes. Small SNNs can implement richer temporal detectors—arrhythmia morphologies, seizure precursors, tremor patterns—within the same or lower power budget as current threshold-based logic [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. Event-based sensing (e.g., DVS-like optical or neural interfaces) aligns naturally with this, reducing the data that must be processed. These neuromorphic micro-reflexes correspond to local insect ganglia: they handle fast pattern recognition and actuation, while higher-level therapy decisions remain with clinicians (Policy Tier).

- Spintronic non-volatility and OTA updates. MRAM-based controllers allow implants to retain code and parameters across brown-outs or partial failures, simplify WCET analysis (no refresh traffic), and support safe over-the-air updates (A/B images, rollback) over multi-year lifetimes, as already emerging in automotive microcontrollers. For implants that must evolve as medical knowledge advances, this combination of non-volatility, robustness and certifiability is crucial.

5.4. Towards a Generic Safety and Certification Methodology

- Fault taxonomy and injection for Reflex Islands. We distinguish permanent vs transient and sensor vs compute vs actuator faults, and consider spintronic-specific modes (MRAM retention loss, write disturb, STNO jitter) alongside conventional digital faults (bit flips, stuck-at, timing violations). For each Reflex Island, we define a fault injection campaign that exercises these modes in software (bit manipulations), at pins (glitching, sensor emulation) and, where feasible, through controlled environmental stress (temperature, radiation). The key property we seek to demonstrate is containment: Reflex faults must either be masked or drive the system into a safe degraded state, without violating WCET envelopes or corrupting neighbouring Reflex Islands.

- WCET tables and end-to-end envelopes. As argued in Section 2.1 and illustrated in Table 2.1 and Table 5.3, each Reflex loop is equipped with a component-level WCET breakdown: sensor exposure and read-out, spike encoding, SNN inference, arbitration, actuator update. These numbers can be obtained from a mix of measurement, vendor data and conservative modelling, and are combined into end-to-end WCET envelopes with explicit margins at hot electrical and thermal corners. The safety case then shows that:

- o under all fault-free conditions, WCET < deadline with margin; and

- o under specified fault conditions, the system either still meets deadlines or enters a well-defined safe state within a bounded latency.

- Thermal and energy burst budgets as formal contracts. The thermal-debt ODE and burst-budget logic of Section 4.8 serve as a contract for prime movers and compute islands: they define admissible BURST durations and continuous WORK envelopes as functions of temperature, ambient conditions and cooling. In the safety case, these contracts are treated like timing contracts: violating them is not permitted; attempts by higher-level policies to request impossible manoeuvres or power profiles are rejected or degraded by the Reflex layer.

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Chan, W.-P.; Prete, F.; Dickinson, M. H. Visual input to the efferent control of wing steering in Drosophila. Nature 1998, 396, 460–464. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, M. H. Halteres in Diptera: the gyroscope of the insect world. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 1999, 354, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egelhaaf, M.; Kern, R.; Juusola, M. Optic-flow based spatial vision in insects. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2023, 209, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palka, J.; et al. The giant fiber pathway of Drosophila. J. Neurogen. 1986, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson, B. H.; et al. A fly’s view of the world. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2019, 54, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, E.; Srinivasan, M. V.; et al. Visual control of flight speed in honeybees. J. Exp. Biol. 2005, 208, 3895–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, R. J.; Menzel, R. Encoding spatial information in the waggle dance. J. Exp. Biol. 2005, 208, 3885–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. S.; et al. Ring attractor dynamics in the Drosophila central brain. Science 2017, 356, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulse, B. K.; et al. A neural circuit for an internal compass in Drosophila. eLife 2021, 10, e66039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grollier, J.; Querlioz, D.; Stiles, M. D. Neuromorphic Spintronics. Nat. Electron. 2020, 3, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infineon Technologies. AURIX™ TC39x Product Brief (2019): up to ~2700 DMIPS; ASIL-D.

- Schuman, C. D.; et al. A survey of neuromorphic computing and applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2022, 9, 011307. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M.; et al. Loihi: A neuromorphic manycore processor with on-chip learning. Proc. IEEE 2019, 107, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indiveri, G.; et al. Neuromorphic vision sensors and processors. Proc. IEEE 2011, 99, 1524–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.-J.; et al. Spintronic devices for in-memory and neuromorphic computing—A review. Materials Today 2023, 70, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrows, C. H.; et al. Neuromorphic computing with spintronics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2024, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lighton, J. R. B. Discontinuous gas exchange in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1996, 41, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chown, S. L.; et al. Discontinuous gas exchange: consensus view. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 3719–3725. [Google Scholar]

- Hetz, S. K.; Bradley, T. J. Insects breathe discontinuously to avoid oxygen toxicity. Nature 2005, 433, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chown, S. L. Discontinuous gas exchange: new perspectives. Funct. Ecol. 2011, 25, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, B. Keeping a cool head: Honeybee thermoregulation. Science 1979, 205, 1269–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, B. The Hot-Blooded Insects; Springer, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner, A.; Kovac, H.; Brodschneider, R. Honeybee colony thermoregulation. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8967. [Google Scholar]

- May, M. L. Thermoregulation in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1991, 36, 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F. P.; et al. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 8th ed.; Wiley, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NIST CODATA. Stefan–Boltzmann constant 5.670374419 × 10−8 W·m−2·K−4.

- Bosch Mobility. Modular common-rail systems: up to 8 injections per cycle. Tech note (accessed 2025).

- Postrioti, L.; et al. Zeuch method-based injection rate analysis of a CR system. Fuel 2014, 130, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.; et al. Split injection in homogeneous-stratified GDI. Energy 2016, 109, 608–620. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, A.; et al. Response of injector typologies to dwell-time variation. Appl. Energy 2016, 169, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; et al. Impact of common-rail systems on diesel engines. Energies 2025, 18, 5259. [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler, D. L.; et al. High-frequency wing strokes in honeybee flight. PNAS 2005, 102, 18213–18218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedrick, T. L.; Miller, L.; Combes, S. A. Recent developments in insect flight. Can. J. Zool. 2015, 93, 925–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, J. W. S. Insect Flight.; Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Syme, D. A. How to build fast muscles. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2002, 42, 762–770, And Syme, D. A., & Josephson, R. K. The efficiency of an asynchronous flight muscle from a beetle. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2002, 205(2), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, J. B. Internal Combustion Engine Fundamentals, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, R. Introduction to Internal Combustion Engines, 4th ed.; Palgrave, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, B. N.; et al. Tip-clearance vs turbine performance. Energies 2020, 13, 4055. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J.; et al. Tip-clearance flow in miniature compressors. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 140, 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, K.; et al. Low-Re effects in small turbomachinery. J. Turbomach. 2019, 141, 111004. [Google Scholar]

- AIP Advances: Tip-clearance & pre-stall features 2023, 13, 115108.

- Capstone Turbine Corp. C30 Microturbine Data Sheet (NG): ≈26% LHV.

- Pure World Energy. Capstone C30 (30 kW): heat rate ≈13.8 MJ/kWh (26% LHV).

- Barnard Microsystems (UAV Engines). Typical rotor ranges: 35k–120k rpm (accessed 2025).

- Garrett/Turbo technical notes. High-speed micro-turbocharger dynamics (accessed 2025).

- JetCat. P250-PRO-S Turbojet: 13–20 s start-to-idle (2019).

- NXP. MPC5777C engine-control MCU: dual 300 MHz + eTPU2 (96 ch), eMIOS (32 ch).

- Renesas. VC4 domain controller: A55 + RH850, tens of kDMIPS (accessed 2025).

- ISO 26262; Road vehicles, Functional safety. 2018.

- Goodman, D.; et al. Descending neurons in Drosophila control behavior. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R928–R934. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, A.; et al. Network statistics of the whole-brain connectome of Drosophila. Nature 2024, 628, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis-Fogh, T. Energetics of hovering flight in hummingbirds and in Drosophila. J. Exp. Biol. 1972, 56, 79–104, and Weis-Fogh, T. (1977). A comparative study of the flight of insects and the mechanical efficiency of their flight muscles. Journal of Experimental Biology, 66(1), 171-205. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.66.1.171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, C. P. Power and efficiency of insect flight muscle. J. Exp. Biol. 1985, 115, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J. F.; Roberts, S. P. Flight respiration and energetics. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000, 62, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; et al. Loihi: A neuromorphic manycore processor with on-chip learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grollier, J.; et al. Neuromorphic Spintronics. Nature Electronics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N. G. A new accident model for engineering safer systems. Safety Science 2004. [Google Scholar]

- MaBouDi, H.; Roper, M.; Guiraud, M.-G.; Juusola, M.; Chittka, L.; Marshall, J. A. R. A neuromorphic model of active vision shows how spatiotemporal encoding in lobula neurons can aid pattern recognition in bees. eLife 2025, 14, e89929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgaty, T.; Vianello, E.; De Salvo, B.; Casas, J. Insect-inspired neuromorphic computing. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 30, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanguas-Gil, A.; Madireddy, S. General policy mapping: online continual reinforcement learning inspired on the insect brain. NeurIPS 2022 Workshop on Offline Reinforcement Learning, OpenReview. 2022. Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=G7IUNe224F.

- Lin, Z.; Hao, Q.; Zhao, B.; Hu, M.; Pei, G. Performance analysis of solar electric bikes. Transp. Res. Part D: Transport Environ. 2024, 132, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furber, S.; Bogdan, P. (Eds.) SpiNNaker: A Spiking Neural Network Architecture; Now Publishers: Hanover, MA, 2020; (Monograph describing the Manchester SpiNNaker neuromorphic platform and its large-scale deployments). [Google Scholar]

- Akopyan, F.; Sawada, J.; Cassidy, A.; et al. TrueNorth: Design and Tool Flow of a 65 mW 1 Million Neuron Programmable Neurosynaptic Chip. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2015, 34(10), 1537–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BrainChip Holdings Ltd. BrainChip Akida neuromorphic processor and MetaTF development environment. Company technical overview and product pages, accessed 2025. (Describes the AKD1000 neuromorphic SoC used in commercial edge-AI kits.).

- Christensen, D. V.; Dittmann, R.; Linares-Barranco, B.; et al. 2022 roadmap on neuromorphic computing and engineering. Neuromorph. Comput. Eng. 2022, 2(2), 022501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE International Roadmap for Devices and Systems (IRDS). Emerging Research Devices / Beyond CMOS Chapter, IRDS 2020 Edition, IEEE, 2020. Available at irds.ieee.org.

- Semiconductor Research Corporation; Semiconductor Industry Association. Decadal Plan for Semiconductors. Full report, 2021. Defines research priorities including spintronic memories and beyond-CMOS logic for energy-efficient computing.

- Available online: www.solbian.eu.

- Available online: https://www.edgeai-trust.eu/.

- Josephson, R. K. The mechanical power output of insect flight muscle. Annual Review of Physiology 1985, 47(1), 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marden, J. H.; Fitzpatrick, M. J.; Møller, C.; Butler, T. B. Limits to flying speed, body size, and the power requirements for insect flight. Journal of Experimental Biology 2000, 203(2), 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photovoltaic Geographical Information system (PVGIS). Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/photovoltaic-geographical-information-system-pvgis_en.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).