Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

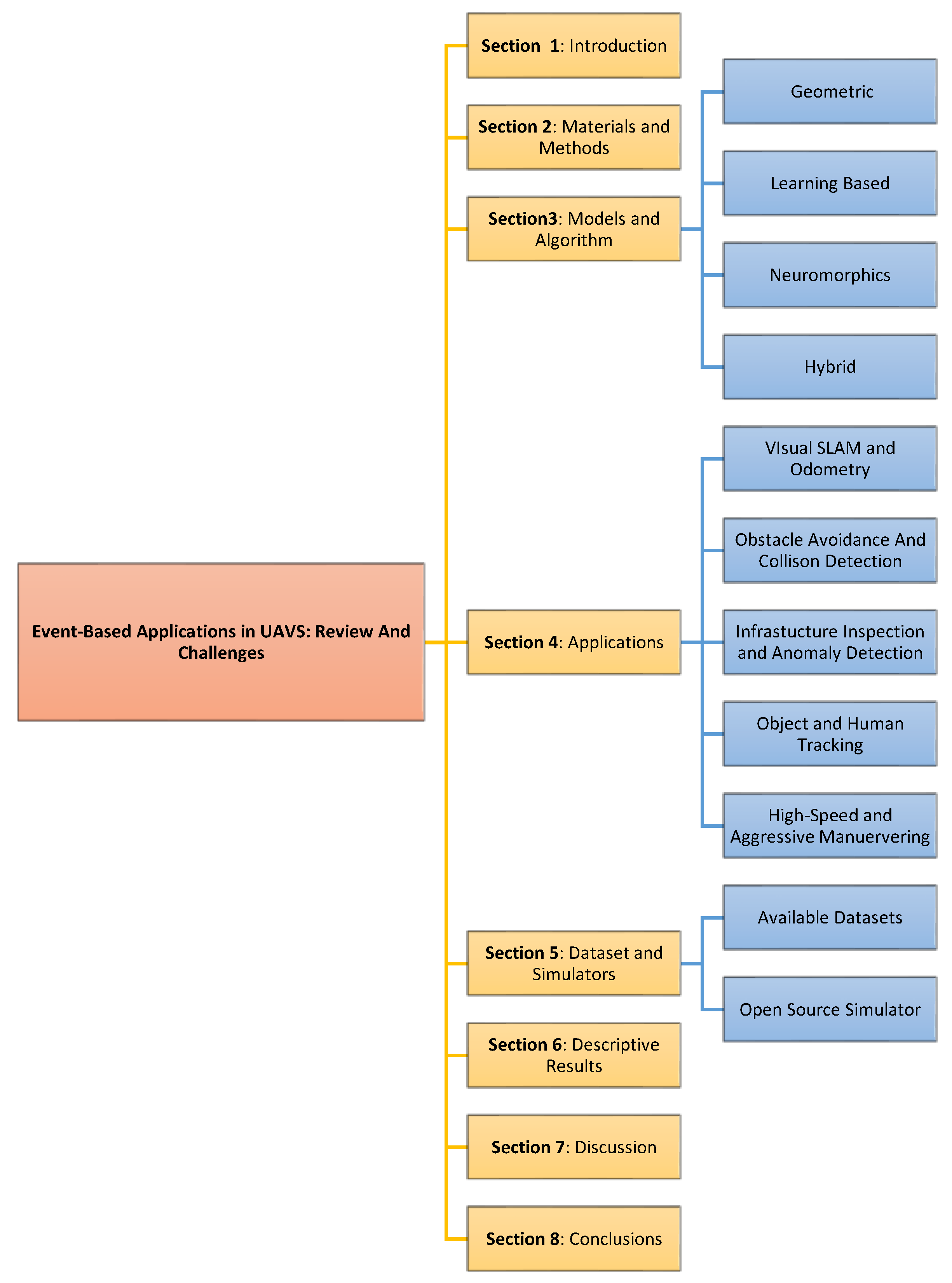

1. Introduction

1.1. Background to Study

- i.

- To examine existing algorithms and techniques - spanning geometric methods, deep learning-based approaches, neuromorphic computing, and hybrid strategies - for processing event data in UAV settings. Understanding how these algorithms outperform or fall short compared to traditional vision pipelines is central to validating the potential of event cameras.

- ii.

- To explore the diverse real-world applications of event cameras in UAVs, such as obstacle avoidance, SLAM, object tracking, infrastructure inspection, and GPS-denied navigation. This review highlights both the demonstrated benefits and operational challenges faced in field deployment.

- iii.

- To catalog and critically assess the publicly available event camera datasets relevant to UAVs, including their quality, scope, and existing limitations. A well-curated dataset is foundational for algorithm development and benchmarking.

- iv.

- Identify and evaluate open-source simulation tools that support event camera modeling and their integration into UAV environments. Simulators play a vital role in reducing experimental costs and enabling reproducible research.

- v.

- To project the future potential of event cameras in UAV systems, including the feasibility of replacing standard cameras entirely, emerging research trends, hardware innovations, and prospective areas for interdisciplinary collaboration.

1.2. Basic Principles of an Event Camera

1.3. Types of Event Cameras

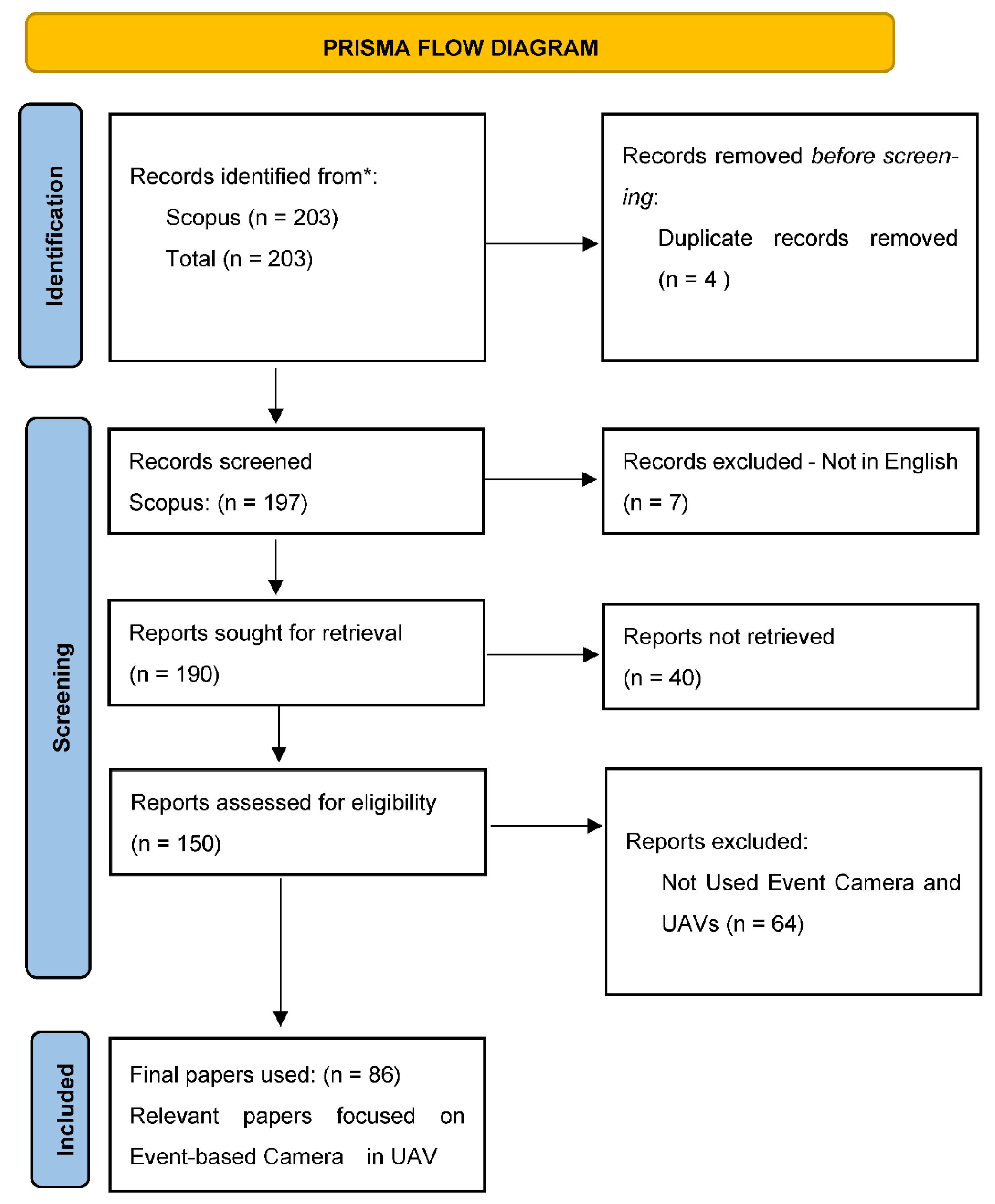

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Terms

2.2. Search Procedure

| keywords | event based camera, event-based camera, dynamic vision sensor, dvs, unmanned aerial vehicle, uavs, drone |

| Databases | Google Scholar, Scopus, Proquest and Web of Science |

| Boolean operator | OR, AND |

| Language | English |

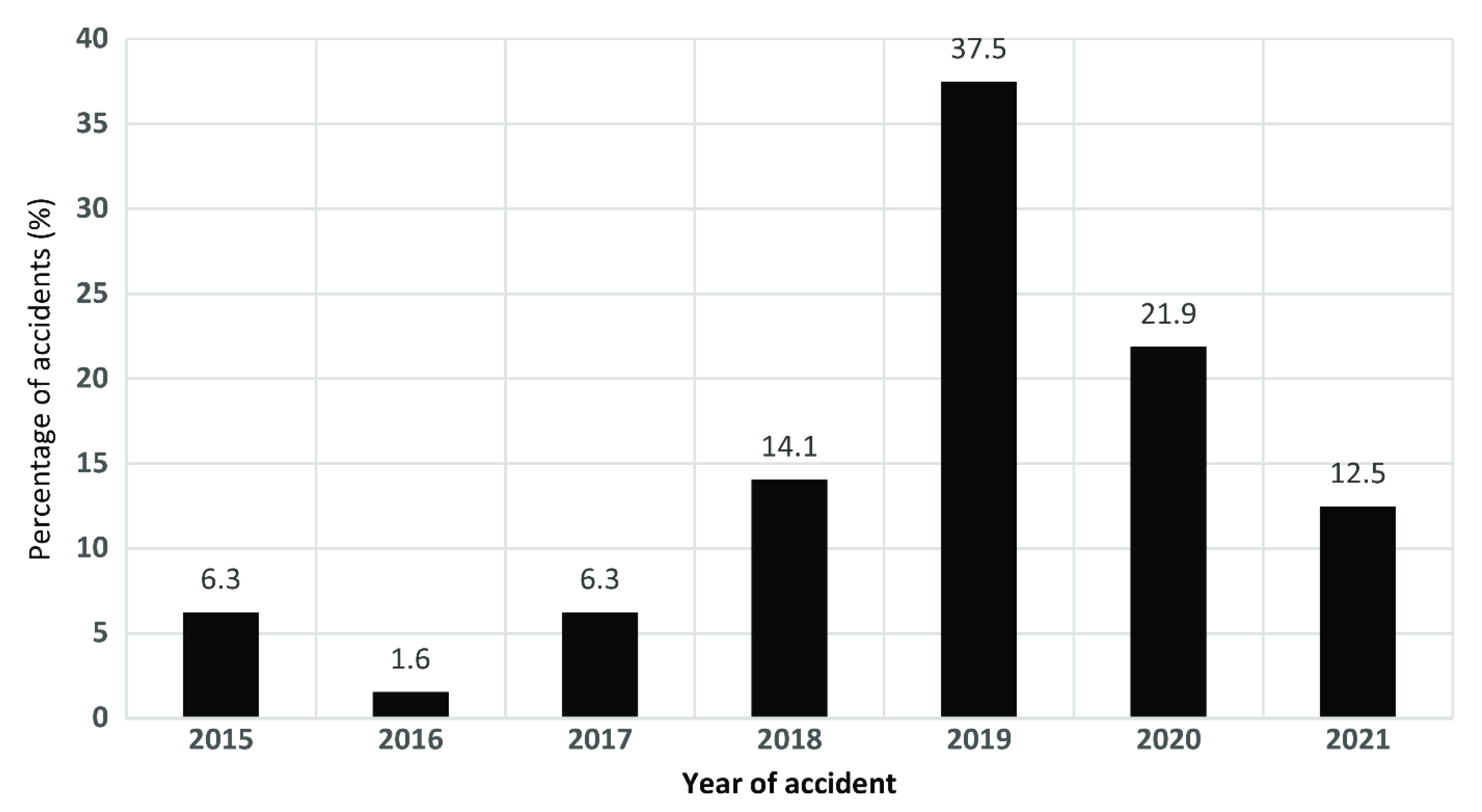

| Year of publication | 2015 to 2025 |

| Inclusion criteria | Event based camera in UAVs |

| Exclusion criteria | Not English |

| Document type | Published scientific paper in academic journals |

3. Models and Algorithms

3.1. Geometric Approach

| Author | Year | DVS Type | Evaluation | Application/Domain | Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [44] | 2015 | DVS 128 | Real Indoor test flight with a miniature quadcopter | Navigation | The research targeted indoor environment. Dynamic scenes with more complex environment is required |

| [45] | 2019 | DVS 128 | Vision Aid Landing | Further work should focus on the robustness and the accuracy of the landmark detection especially in a complex scene. | |

| [25] | 2020 | SEES1 | Real world Experiment with Quadrotor | Dynamic obstacle avoidance | This approach model obstacles as ellipsoids and relies on sparse representation. Extending this approach to a more complex environments with non-ellipsoidal obstacles and clutter urban environments remain a challenge |

| [46] | 2023 | Nil | Real life with UAV | Navigation and control | The algorithm is limited to 3-DoF displacement (translation) and does not incorporate changes in orientation, limiting its capability to fully determine the 6-DoF pose. |

| [47] | 2023 | DAVIS 240C | MVSCEC Dataset | Navigation | The author recommended a complete SLAM framework for high speed UAV based on even camera |

| [48] | 2024 | CeleX-5 | Real world with UAV and simulation with Unreal engine and Airsim | Powerline inspection and tracking | Lack of dataset in that domain and inability of the model to accurately distinguish between powerlines and non-linear object in a complex scene |

| [49] | 2024 | DAVIS 326 | Real-world with Octorotor UAV in indoor and outdoor | Load transport; cable swing minimization | Future work could focus on enhancing event detection robustness during larger cable swings, developing more sophisticated fusion techniques, and extending the method's applicability to dynamic, highly noisy environments. |

3.2. Learning-Based Methods

| Author | Year | Event Camera Type | Method of Evaluation | Application/Domain | Learning Method | Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [55] | 2022 | DVS | The system was evaluated via simulation trials in Microsoft AirSim, | Event-based object detection, obstacle avoidance | Deep reinforcement learning | The study highlights the need to optimize network size for better perception range, design new reward functions for dynamic obstacles, and incorporate LSTM for improved dynamic obstacle sensing and avoidance in UAVs |

| [56] | 2023 | DAVIS346 | Real-world testing with a hexarotor UAV installed with both event and frame based camera and simulation in Matlab Simulink | Visual servoing robustness | Deep reinforcement learning | The proposed DNN with noise protected MRFT lack robust high-speed target tracking under noisy visual sensor data and slow update-rate sensors; future directions include developing adaptive system identification for high-velocity targets and optimizing neural network-based tuning to improve real-time accuracy under varying sensor delays and noise conditions |

| [57] | 2024 | Prophesee camera EVK4–HD | To bridge the data gap the first large scale high resolution event-based tracking dataset called EventVot was produced through UAVs and used for real world evaluation | Obstacle localization; navigation | Transformer-based neural networks |

The high-resolution capability of the Prophesee EVK4–HD camera (1280 × 720) opens new avenues for improving event-based tracking, but it also introduces additional challenges, such as increased computational complexity and data processing requirements. |

| [58] | 2024 | DAVIS 346c | Real world testing in a controlled environment with hexacopter | Obstacle avoidance | Graph Transformer Neural Network (GTNN) | Real world experiment in a complex environment is limited in the research |

3.3. Neuro-Morphic System Approach of Computing

| Author | Year | Event Camera Type | Method of Evaluation | Application/Domain | Model | Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [59] | 2017 | DVS | real-world recorded data from a DVS mounted on a QUAV | Obstacle avoidance | Spiking Neural network model of LGMD | Integrate motion direction detection (EMD) and enhance sensitivity for diverse stimuli |

| [64] | 2019 | DVS240 | Real-world testing in indoor environment using the actual data from the DVS sensor and simulation testing using data that was processed through an event simulator (PIX2NVS) | Drone detection |

SNNs) trained using spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP). | The model was tested in an inddor environment. Exploring the system in a resources-contrained environment is critical |

| [65] | 2020 | DAVIS240C | Real world experiment on two motor 1-DOF UAV | SLAM | PID+SNN | The authors suggested the potential for integrating adaptation mechnism and online learning into the SNN-based controllers by utilizing the chip’s on-chip plasticity |

| [66] | 2023 | Simulated DVS implemented through the v2e tool within the AirSim environment | Obstacle avoidance |

Deep Double Q-Network (D2QN) integrated with SNN and CNN | Improve network architecture for better performance in real world | |

| [67] | 2025 | - | Real-world experiment on drone | Obstacle avoidance | Chiasm-inspired Event Filtering (CEF) and LGN-inspired Event Matching (LEM), | Extending the design principle beyond obstacle avoidance to navigation |

3.4. Hybrid Sensor Integration Methods

| Author | Year | Event Camera Type | Method of Evaluation | Application/Domain | Model | Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [68] | 2018 | DVS | The result was evaluated with [39] | SLAM | Hybrid State Estimation combinining data from event, standard camera and IMU. | Future work should expand this multimodal sensor in more complex real world application |

| [69] | 2022 | DAVIS 346 | 6DOF quadrotor and also using dataset from [40] | VIO(Visual inertial domometry) | VIO model combining event camera, IMU and depth camera for range observations. | According to the author, the effect of noise and illumination on the algoithm is worth to study in the next step. |

| [70] | 2023 | DAVIS346 | Real world in a static and dynamic environment using AMOV-P450 drone. | Motion tracking and obstacle detection | It fuses asynchronous event streams and standard image utilizing nonlinear optimization through Photometric Bundle Adjustment with sliding windows of keyframes, refining pose estimates. | Future work aims to incorporate edge computing to accelerate processing |

| [71] | 2024 | Prophesee EVK4-HD sensor. |

Two insulator defect datasets, CPLID and SFID. | Power line inspection | YOLOv8 | While the experiment used reproduced event data derived from RGB images, the authors note that real-time captured event data could better exploit the advantages of neuromorphic vision sensors |

| [72] | 2024 | - | Simulated data and real-world nighttime traffic scenes captured by a paired RGB and event camera setup on drones | Object Tracking | Dual-input 3D CNN with self-attention | Integration of complementary sensors such as LIDAR and IMUs for depth-aware 3D representations and more robust object tracking |

| [73] | 2024 | Real world testing on Quadrotor in both indoor and outdoor | VIO | PL-EVIO which tightly-coupled optimization-based monocular event and inertial fusion. |

Extending the work to event-based multi-sensor fusion beyond visual-inertial, such as integrating LiDAR for local perception and visible light positioning or GPS for global perception, to further exploit complementary sensor advantages |

4. Application Benefits of Event Cameras Vision System on UAVs

4.1. Visual SLAM and Odometry

4.2. Obstacle Avoidance and Collison Detection

4.3. GPS-Denied Navigation and Terrain Relative Flight

4.4. Infrastructure Inspection and Anomaly Detection

4.5. Object and Human Tracking in Dynamic Scenes

4.6. High-Speed and Aggressive Maneurvering

| Cited Works | Application Area | Challenges / Future Directions |

|---|---|---|

| [30,39,42,60,68,79,80] | Visual SLAM and Odometry | Performance degrades in low-texture or highly dynamic scenes; need for stronger sensor fusion (e.g., with IMU, depth); robustness under aggressive manoeuvres. |

| [24,25,53,55,58,66,70,81,82,83,84] | Obstacle Avoidance and Collision Detection | Filtering noisy activations; setting adaptive thresholds in cluttered, multi-object environments; scaling to dense urban or swarming scenarios. |

| [85] | GPS-Denied Navigation and Terrain Relative Flight | Requires fusion with depth and inertial data for stability; limited long-term robustness; neuromorphic SLAM hardware still in early stages. |

| [74] | Infrastructure Inspection and Anomaly Detection | Lack of large, annotated datasets; absence of benchmarking standards; need for generalization across varied materials and lighting. |

| [86] | Object and Human Tracking in Dynamic Scenes | Sparse, non-textured data limits fine-grained classification; re-identification with event-only streams remains difficult; improved multimodal fusion needed. |

| [78] | High-Speed and Aggressive Maneuvering | Algorithms need to generalize from lab to real-world; neuromorphic hardware maturity; power-efficiency vs. control accuracy trade-offs. |

5. Datasets and Open-Source Tools

5.1. Available Datasets for Event Cameras in UAVs Applications

- A.

- Event-Camera Dataset for High-Speed Robotic Tasks

- B. Davis Drone Racing Dataset

- C. Extreme Event Dataset (EED)

- D. Multi-Vehicle Stereo Event Camera Dataset (MVSEC)

- D. RPG Group Zurich Event Camera Dataset

- E. EVDodgeNet Dataset

- F. Event-Based Vision Dataset (EV-IMO)

- G. DSEC

- H. EVIMO2

5.1.1. Summary of Available Datasets

5.2. Simulator and Emulators

- A.

- Robotic Operating System (ROS)

- B. Gazebo and Rviz

5.2.1. Challenges in Software Development for Event Cameras Vision System in UAVs

| S/N | Name | Inventor | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ESIM (Event Camera Simulator) | [97] | 2018 | https://github.com/uzh-rpg/rpg_esim |

| 2 | ESVO (Event-based Stereo Visual Odometry) | [99] | 2022 | https://github.com/HKUST-Aerial-Robotics/ESVO |

| 3 | UltimateSLAM | [68] | 2018 | https://github.com/uzh-rpg/rpg_ultimate_slam_open |

| 4 | DVS ROS (Dynamic Vision Sensor ROS Package) | [100] | 2015 | https://github.com/uzh-rpg/rpg_dvs_ros |

| 5 | rpg_evo (Event-based Visual Odometry) | [101] | 2020 | https://github.com/uzh-rpg/rpg_evo |

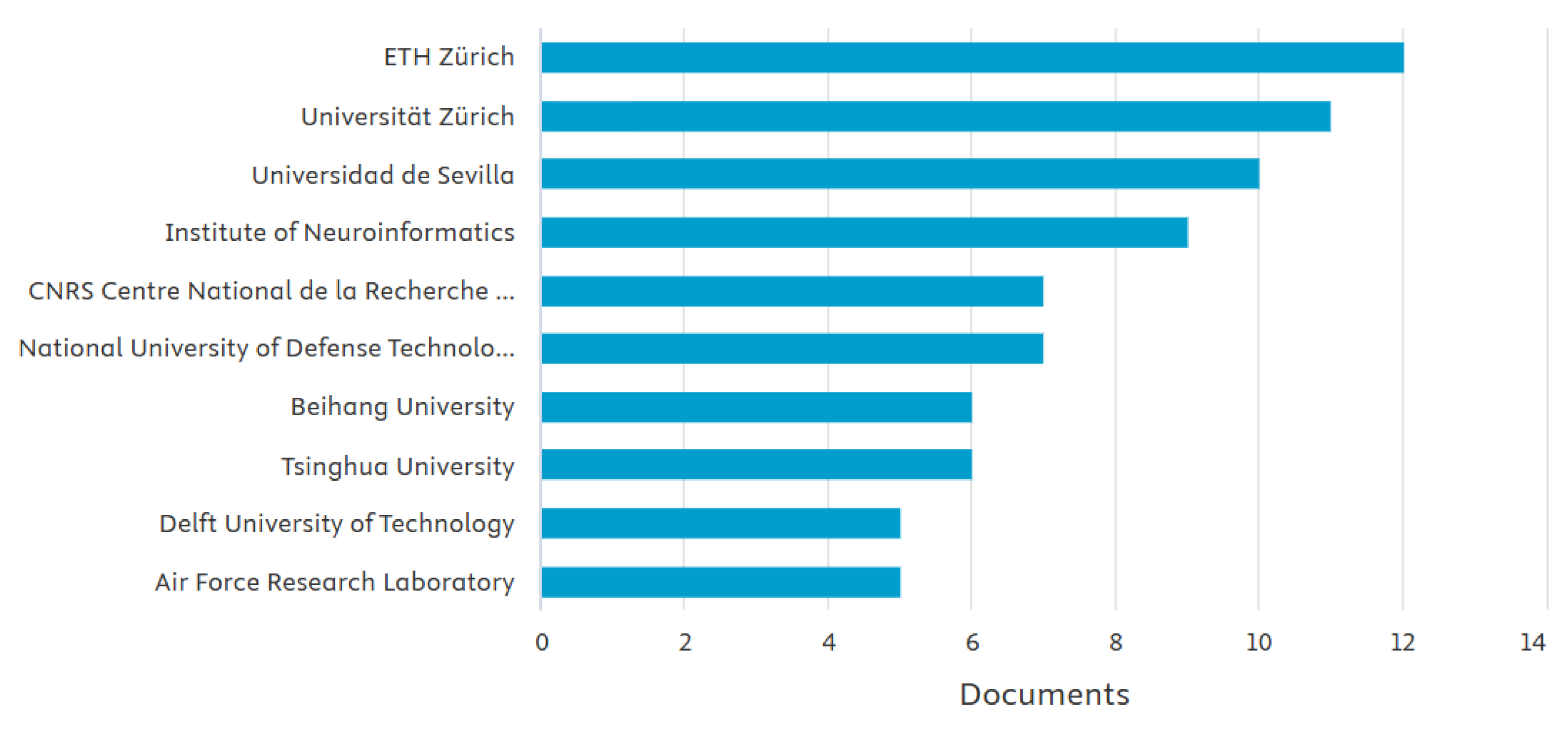

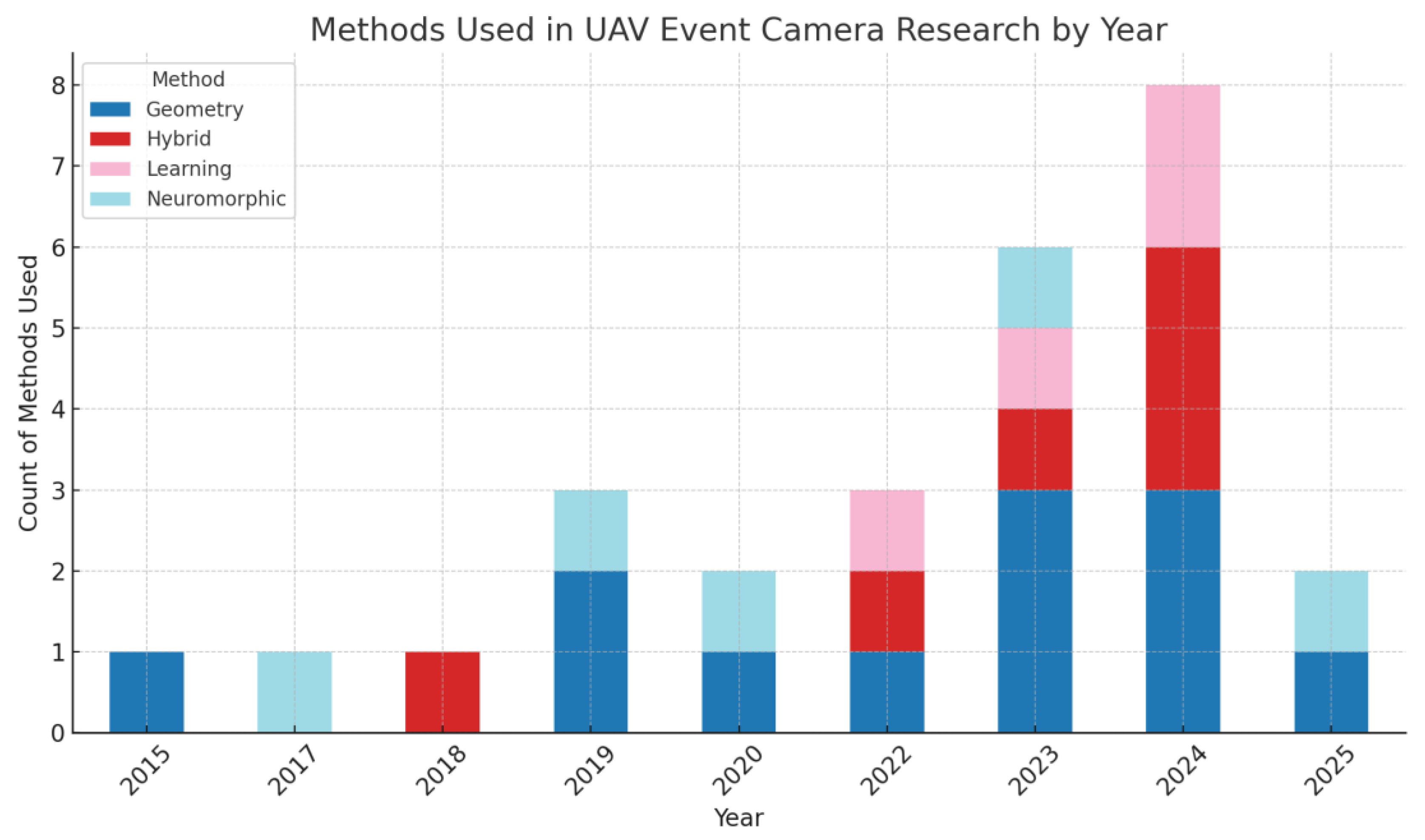

6. Discussion

| Year | Event Camera Type(s) |

|---|---|

| 2015 | DVS 128 |

| 2017 | DVS |

| 2018 | DVS |

| 2019 | DVS 128, DVS 240 |

| 2020 | SEES1, DAVIS 240C |

| 2022 | Celex4 Dynamic Vision Sensor, DAVIS 346 |

| 2023 | DAVIS, DAVIS 240C, DAVIS 346, DAVIS 346c |

| 2024 | CeleX-5, Prophesee EVK4-HD, DAVIS 326 |

| 2025 | DVS346 |

7. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| APS | Active Pixel Sensor |

| ATIS | Asynchronous Time-based Image Sensor |

| AirSIM | Aerial Information and Robotics Simulation |

| CEF | Chiasm-inspired Event Filtering |

| CNN | Convolution Neural Network |

| D2QN | Deep Double Q-Network |

| DAVIS | Dynamic and Active-pixel Vision Sensor |

| DNN | Deep Neura Network |

| DOF | Degree Of Freedom |

| DVS | Dynamic Vision Sensor |

| EED | Extreme Event Dataset |

| ESIM | Event-camera Simulator |

| EVO | Event-based Visual Inertia Odometry |

| GPS | Global Position System |

| GTNN | Graph Transformer Neural Network |

| HDR | High Dynamic Range |

| IMU | Inertia Measuring Unit |

| LGMD | Locus lobula Giant Movement Detecto |

| LIDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| MEMS | Micromechanical System |

| MOD | Moving Object Detection |

| MVSEC | Multi-Vehicle Stereo Event Camera |

| PID | Propotional Integra Derivative |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RGB | Red, Green Blue |

| ROS | Robotics Operating System |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| SNN | Spiking Neural Network |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UAS | Unmanned Aircraft System |

| VIO | Visual Inertia Odometry |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- F. Outay, H. A. Mengash, and M. Adnan. Applications of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) in road safety, traffic and highway infrastructure management: Recent advances and challenges. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 2020, 141, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Ahirwar, R. Swarnkar, S. Bhukya, and G. Namwade. Application of drone in agriculture. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 2019, 8, 2500–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Waharte and N. Trigoni. Supporting search and rescue operations with UAVs. in 2010 international conference on emerging security technologies, IEEE, 2010, pp. 142–147.

- S. Jung and H. Kim. Analysis of amazon prime air uav delivery service. Journal of Knowledge Information Technology and Systems 2017, 12, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Guo, X. Liu, L. Bi, H. Liu, and H. Lou. Un-yolov5s: A uav-based aerial photography detection algorithm. Sensors 2023, 23, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. F. Gonzalez, G. A. Montes, E. Puig, S. Johnson, K. Mengersen, and K. J. Gaston. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and artificial intelligence revolutionizing wildlife monitoring and conservation. Sensors 2016, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. J. Kim, Y. S. J. Kim, Y. Jeong, S. Park, K. Ryu, and G. Oh. A survey of drone use for entertainment and AVR (augmented and virtual reality). in Augmented reality and virtual reality: empowering human, place and business, Springer, 2017, pp. 339–352.

- L. F. Gonzalez, G. A. Montes, E. Puig, S. Johnson, K. Mengersen, and K. J. Gaston. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and artificial intelligence revolutionizing wildlife monitoring and conservation. Sensors 2016, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. -K. Wang, S.-E. Wang, and P.-H. Wu. Spike-event object detection for neuromorphic vision. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 5215–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Chamola, V. Hassija, V. Gupta, and M. Guizani. A comprehensive review of the COVID-19 pandemic and the role of IoT, drones, AI, blockchain, and 5G in managing its impact. Ieee access 2020, 8, 90225–90265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Makam, B. K. Komatineni, S. S. Meena, and U. Meena. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): an adoptable technology for precise and smart farming. Discover Internet of Things 2024, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Sudhakar, V. Vijayakumar, C. S. Kumar, V. Priya, L. Ravi, and V. Subramaniyaswamy. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) based Forest Fire Detection and monitoring for reducing false alarms in forest-fires. Comput Commun 2020, 149, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Gupta, and S. K. Gupta. Emerging UAV technology for disaster detection, mitigation, response, and preparedness. J Field Robot 2022, 39, 905–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen. Application of UAV remote sensing in natural disaster monitoring and early warning: an example of flood and mudslide and earthquake disasters. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology 2024, 85, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate De Mey. Event Cameras – An Evolution in Visual Data Capture. https://robohub.org/event-cameras-an-evolution-in-visual-data-capture.

- W. Shariff, M. S. Dilmaghani, P. Kielty, M. Moustafa, J. Lemley, and P. Corcoran. Event cameras in automotive sensing: A review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 51275–51306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Chakravarthi, A. A. B. Chakravarthi, A. A. Verma, K. Daniilidis, C. Fermuller, and Y. Yang. Recent event camera innovations: A survey. in European Conference on Computer Vision, Springer, 2024, pp. 342–376.

- K. Iddrisu, W. Shariff, P. Corcoran, N. E. O’Connor, J. Lemley, and S. Little. Event camera-based eye motion analysis: A survey. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 136783–136804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Gehrig and D. Scaramuzza. Low-latency automotive vision with event cameras. Nature 2024, 629, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune Business Insights. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle [UAV] Market Size, Share, Trends & Industry Analysis, By Type (Fixed Wing, Rotary Wing, Hybrid), By End-use Industry, By System, By Range, By Class, By Mode of Operation, and Regional Forecast, 2024–2032. https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/industry-reports/unmanned-aerial-vehicle-uav-market-101603.

- T. Li, J. T. Li, J. Liu, W. Zhang, Y. Ni, W. Wang, and Z. Li. Uav-human: A large benchmark for human behavior understanding with unmanned aerial vehicles. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 16266–16275.

- G. Gallego et al.. Event-based vision: A survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2020, 44, 154–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrokhin, C. Fermüller, C. Parameshwara, and Y. Aloimonos. Event-based moving object detection and tracking. in 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–9.

- D. Falanga, K. Kleber, and D. Scaramuzza. Dynamic obstacle avoidance for quadrotors with event cameras. Sci Robot 2020, 5, eaaz9712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. J. Sanket et al.. Evdodgenet: Deep dynamic obstacle dodging with event cameras. in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), IEEE, 2020, pp. 10651–10657.

- J. P. Rodríguez-Gómez, R. Tapia, M. del M. G. Garcia, J. R. Martínez-de Dios, and A. Ollero. Free as a bird: Event-based dynamic sense-and-avoid for ornithopter robot flight. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2022, 7, 5413–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Cazzato and F. Bono. An application-driven survey on event-based neuromorphic computer vision. Information 2024, 15, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Stoffregen, G. T. Stoffregen, G. Gallego, T. Drummond, L. Kleeman, and D. Scaramuzza. Event-based motion segmentation by motion compensation. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2019, pp. 7244–7253.

- C. Brandli, R. Berner, M. Yang, S.-C. Liu, and T. Delbruck. A 240× 180 130 db 3 µs latency global shutter spatiotemporal vision sensor. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 2014, 49, 2333–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Gehrig, A. D. Gehrig, A. Loquercio, K. G. Derpanis, and D. Scaramuzza. End-to-end learning of representations for asynchronous event-based data. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 5633–5643.

- J. Wan et al.. Event-based pedestrian detection using dynamic vision sensors. Electronics (Basel) 2021, 10, 888. [Google Scholar]

- P. Lichtsteiner, C. Posch, and T. Delbruck. A 128$\times $128 120 dB 15$\mu $ s latency asynchronous temporal contrast vision sensor. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 2008, 43, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Mueggler, H. Rebecq, G. Gallego, T. Delbruck, and D. Scaramuzza. The event-camera dataset and simulator: Event-based data for pose estimation, visual odometry, and SLAM. Int J Rob Res 2017, 36, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Posch, D. C. Posch, D. Matolin, and R. Wohlgenannt. An asynchronous time-based image sensor. in 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), IEEE, 2008, pp. 2130–2133.

- D. Joubert, A. Marcireau, N. Ralph, A. Jolley, A. Van Schaik, and G. Cohen. Event camera simulator improvements via characterized parameters. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 702765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Beck et al.. An extended modular processing pipeline for event-based vision in automatic visual inspection. Sensors 2021, 21, 6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. P. Moeys et al.. Color temporal contrast sensitivity in dynamic vision sensors. in 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–4.

- C. Scheerlinck, H. C. Scheerlinck, H. Rebecq, T. Stoffregen, N. Barnes, R. Mahony, and D. Scaramuzza. CED: Color event camera dataset. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 2019, p. 0.

- D. Moher, A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, and P. Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. International journal of surgery 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Mueggler, H. Rebecq, G. Gallego, T. Delbruck, and D. Scaramuzza. The event-camera dataset and simulator: Event-based data for pose estimation, visual odometry, and SLAM. Int J Rob Res 2017, 36, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Vidal, H. Rebecq, T. Horstschaefer, and D. Scaramuzza. Ultimate SLAM? Combining events, images, and IMU for robust visual SLAM in HDR and high-speed scenarios. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2018, 3, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Gallego, H. G. Gallego, H. Rebecq, and D. Scaramuzza. A unifying contrast maximization framework for event cameras, with applications to motion, depth, and optical flow estimation. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 3867–3876.

- E. Mueggler, G. Gallego, H. Rebecq, and D. Scaramuzza. Continuous-time visual-inertial odometry for event cameras. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2018, 34, 1425–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Rebecq, T. Horstschäfer, G. Gallego, and D. Scaramuzza. Evo: A geometric approach to event-based 6-dof parallel tracking and mapping in real time. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2016, 2, 593–600. [Google Scholar]

- J. Conradt. On-board real-time optic-flow for miniature event-based vision sensors. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2015, pp. 1858–1863. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu and T. Delbrück. Adaptive time-slice block-matching optical flow algorithm for dynamic vision sensors. BMVA Press, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2. 8508.

- J. Zhang, Y. J. Zhang, Y. Hu, B. Zhang, and Q. Gao. Research on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle vision-aid landing with Dynamic vision sensor. B. Xu and K. Mou, Eds., Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2019, pp. 965–969. [CrossRef]

- H. Stuckey, A. Al-Radaideh, L. Sun, and W. Tang. A Spatial Localization and Attitude Estimation System for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using a Single Dynamic Vision Sensor. IEEE Sens J 2022, 22, 15497–15507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Jianguo, W. Z. Jianguo, W. Pengfei, H. Sunan, X. Cheng, and T. S. Huat Rodney. Stereo Depth Estimation Based on Adaptive Stacks from Event Cameras. in IECON Proceedings (Industrial Electronics Conference), 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Escudero, M. W. N. Escudero, M. W. Hardt, and G. Inalhan. Enabling UAVs night-time navigation through Mutual Information-based matching of event-generated images. in AIAA/IEEE Digital Avionics Systems Conference - Proceedings, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. 845 LNEE. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, W. J. Zhao, W. Zhang, Y. Wang, S. Chen, X. Zhou, and F. Shuang. EAPTON: Event-based Antinoise Powerlines Tracking with ON/OFF Enhancement. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Panetsos, G. C. Karras, and K. J. Kyriakopoulos. Aerial Transportation of Cable-Suspended Loads with an Event Camera. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2024, 9, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Rebecq, R. H. Rebecq, R. Ranftl, V. Koltun, and D. Scaramuzza. Events-to-video: Bringing modern computer vision to event cameras. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019, pp. 3857–3866.

- I. Maqueda, A. I. Maqueda, A. Loquercio, G. Gallego, N. García, and D. Scaramuzza. Event-based vision meets deep learning on steering prediction for self-driving cars. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 5419–5427.

- Z. Zhu, L. Z. Zhu, L. Yuan, K. Chaney, and K. Daniilidis. EV-FlowNet: Self-supervised optical flow estimation for event-based cameras. arXiv, arXiv:1802.06898.

- Mitrokhin, C. Ye, C. Fermüller, Y. Aloimonos, and T. Delbruck. EV-IMO: Motion segmentation dataset and learning pipeline for event cameras. in 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), IEEE, 2019, pp. 6105–6112.

- Mitrokhin, C. Fermüller, C. Parameshwara, and Y. Aloimonos. Event-based moving object detection and tracking. in 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–9.

- X. 13606 LNAI. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Hay et al.. Noise-Tolerant Identification and Tuning Approach Using Deep Neural Networks for Visual Servoing Applications. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2023, 39, 2276–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Wang et al.. Event Stream-Based Visual Object Tracking: A High-Resolution Benchmark Dataset and A Novel Baseline. in Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, IEEE Computer Society, 2024, pp. 19248–19257. [CrossRef]

- Y. Alkendi, O. A. Y. Alkendi, O. A. Hay, M. A. Humais, R. Azzam, L. D. Seneviratne, and Y. H. Zweiri. Dynamic-Obstacle Relative Localization Using Motion Segmentation with Event Cameras. 2024, pp. 1056–1063. [CrossRef]

- L. Salt, G. L. Salt, G. Indiveri, and Y. Sandamirskaya. Obstacle avoidance with LGMD neuron: Towards a neuromorphic UAV implementation. in Proceedings - IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. -H. Yoon and A. Raychowdhury. NeuroSLAM: A 65-nm 7.25-to-8.79-TOPS/W Mixed-Signal Oscillator-Based SLAM Accelerator for Edge Robotics. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits 2021, 56, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Sandamirskaya, M. Kaboli, J. Conradt, and T. Celikel. Neuromorphic computing hardware and neural architectures for robotics. Sci Robot 2022, 7, eabl8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Davies et al.. Advancing neuromorphic computing with loihi: A survey of results and outlook. Proceedings of the IEEE 2021, 109, 911–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Lele and A. Raychowdhury. Fusing frame and event vision for high-speed optical flow for edge application. in 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), IEEE, 2022, pp. 804–808.

- P. Kirkland, G. P. Kirkland, G. Di Caterina, J. Soraghan, Y. Andreopoulos, and G. Matich. UAV Detection: A STDP Trained Deep Convolutional Spiking Neural Network Retina-Neuromorphic Approach. in Lecture Notes in Computer Science, I. V Tetko, P. Karpov, F. Theis, and V. Kurková, Eds., Springer Verlag service@springer.de, 2019, pp. 724–736. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Stagsted, A. R. K. Stagsted, A. Vitale, J. Binz, A. Renner, L. B. Larsen, and Y. Sandamirskaya. Towards neuromorphic control: A spiking neural network based PID controller for UAV. in Robotics: Science and Systems, M. Toussaint, A. Bicchi, and T. Hermans, Eds., MIT Press Journals, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Zanatta, A. Di Mauro, F. Barchi, A. Bartolini, L. Benini, and A. Acquaviva. Directly-trained spiking neural networks for deep reinforcement learning: Energy efficient implementation of event-based obstacle avoidance on a neuromorphic accelerator. Neurocomputing 2023, 562, 126885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Li et al.. Taming Event Cameras With Bio-Inspired Architecture and Algorithm: A Case for Drone Obstacle Avoidance. IEEE Trans Mob Comput 2025, 24, 4202–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Vidal, H. Rebecq, T. Horstschaefer, and D. Scaramuzza. Ultimate SLAM? Combining events, images, and IMU for robust visual SLAM in HDR and high-speed scenarios. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2018, 3, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, B. Y. Wang, B. Shao, C. Zhang, J. Zhao, and Z. Cai. REVIO: Range- and Event-Based Visual-Inertial Odometry for Bio-Inspired Sensors. Biomimetics, 2022; 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Guan, P. Chen, Y. Xie, and P. Lu. PL-EVIO: Robust Monocular Event-Based Visual Inertial Odometry with Point and Line Features. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2024, 21, 6277–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu et al.. FlyTracker: Motion Tracking and Obstacle Detection for Drones Using Event Cameras. in Proceedings - IEEE INFOCOM, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. 14261 LNCS. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Q. Han, X. H. Y. Q. Han, X. H. Yu, H. Luan, and J. L. Suo. Event-Assisted Object Tracking on High-Speed Drones in Harsh Illumination Environment. DRONES, 2024; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Sun, Y. L. Sun, Y. Li, X. Zhao, K. Wang, and H. Guo. Event-RGB Fusion for Insulator Defect Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024, pp. 794–802. [CrossRef]

- D. Hannan, R. D. Hannan, R. Arnab, G. Parpart, G. T. Kenyon, E. Kim, and Y. Watkins. Event-To-Video Conversion for Overhead Object Detection. in Proceedings of the IEEE Southwest Symposium on Image Analysis and Interpretation, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024, pp. 89–92. [CrossRef]

- U. G. Gamage et al.. Event-based Civil Infrastructure Visual Defect Detection: ev-CIVIL Dataset and Benchmark. arXiv, arXiv:2504.05679.

- Safa, T. Verbelen, I. Ocket, A. Bourdoux, F. Catthoor, and G. G. E. Gielen. Fail-Safe Human Detection for Drones Using a Multi-Modal Curriculum Learning Approach. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2022, 7, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Lele, Y. Fang, A. Anwar, and A. Raychowdhury. Bio-mimetic high-speed target localization with fused frame and event vision for edge application. Front Neurosci 2022, 16, 1010302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . A neuromorphic SLAM architecture using gated-memristive synapses. Neurocomputing 2020, 381, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. J. Cai et al.. TrinitySLAM: On-board Real-time Event-image Fusion SLAM System for Drones. ACM Trans Sens Netw, 2024; 6. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang <i></i>. Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Using Dynamic Vision Sensor. in <i>Lecture Notes in Computer Science</i>, L.; et al. X. Zhang et al.. Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Using Dynamic Vision Sensor. in Lecture Notes in Computer Science, L. Iliadis, A. Papaleonidas, P. Angelov, and C. Jayne, Eds., Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2023, pp. 161–173. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wan et al.. A Fast and Safe Neuromorphic Approach for Obstacle Avoidance of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. in Conference Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024, pp. 1963–1968. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu, Z. X. Hu, Z. Liu, X. Wang, L. Yang, and G. Wang. Event-Based Obstacle Sensing and Avoidance for an UAV Through Deep Reinforcement Learning. in Lecture Notes in Computer Science, L. Fang, D. Povey, G. Zhai, T. Mei, and R. Wang, Eds., Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2022, pp. 402–413. [CrossRef]

- L. Salt, D. Howard, G. Indiveri, and Y. Sandamirskaya. Parameter Optimization and Learning in a Spiking Neural Network for UAV Obstacle Avoidance Targeting Neuromorphic Processors. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2020, 31, 3305–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elamin, A. El-Rabbany, and S. Jacob. Event-based visual/inertial odometry for UAV indoor navigation. Sensors 2024, 25, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safa, T. Verbelen, I. Ocket, A. Bourdoux, F. Catthoor, and G. G. E. Gielen. Fail-safe human detection for drones using a multi-modal curriculum learning approach. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2021, 7, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueckauer and, T. Delbruck. Evaluation of event-based algorithms for optical flow with ground-truth from inertial measurement sensor. Front Neurosci 2016, 10, 176. [Google Scholar]

- J. Yin, A. Li, T. Li, W. Yu, and D. Zou. M2dgr: A multi-sensor and multi-scenario slam dataset for ground robots. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2021, 7, 2266–2273. [Google Scholar]

- J. Delmerico, T. J. Delmerico, T. Cieslewski, H. Rebecq, M. Faessler, and D. Scaramuzza. Are we ready for autonomous drone racing? the UZH-FPV drone racing dataset. in 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), IEEE, 2019, pp. 6713–6719.

- T. Stoffregen, G. T. Stoffregen, G. Gallego, T. Drummond, L. Kleeman, and D. Scaramuzza. Event-based motion segmentation by motion compensation. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2019, pp. 7244–7253.

- Z. Zhu, D. Thakur, T. Özaslan, B. Pfrommer, V. Kumar, and K. Daniilidis. The multivehicle stereo event camera dataset: An event camera dataset for 3D perception. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2018, 3, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kueng, E. Mueggler, G. Gallego, and D. Scaramuzza. Low-latency visual odometry using event-based feature tracks. in 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), IEEE, 2016, pp. 16–23.

- N. J. Sanket et al.. Evdodgenet: Deep dynamic obstacle dodging with event cameras. in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), IEEE, 2020, pp. 10651–10657.

- M. Gehrig, W. Aarents, D. Gehrig, and D. Scaramuzza. Dsec: A stereo event camera dataset for driving scenarios. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2021, 6, 4947–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Burner, A. L. Burner, A. Mitrokhin, C. Fermüller, and Y. Aloimonos. Evimo2: an event camera dataset for motion segmentation, optical flow, structure from motion, and visual inertial odometry in indoor scenes with monocular or stereo algorithms. arXiv, arXiv:2205.03467.

- J. Delmerico, T. J. Delmerico, T. Cieslewski, H. Rebecq, M. Faessler, and D. Scaramuzza. Are we ready for autonomous drone racing? the UZH-FPV drone racing dataset. in 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), IEEE, 2019, pp. 6713–6719.

- H. Rebecq, D. H. Rebecq, D. Gehrig, and D. Scaramuzza. Esim: an open event camera simulator. in Conference on robot learning, PMLR, 2018, pp. 969–982.

- Koubâa, Robot Operating System (ROS)., vol. 1. Springer, 2017.

| Type | Operation | Gaps |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Vision Sensors (DVS). [29] |

Detecting variations in brightness is the sole method used by DVS, the most popular kind of event camera. When the amount of light in the scene varies enough, each pixel in a DVS independently scans the area and initiates an event. With their high temporal resolution and lack of motion blur, DVS sensors work especially well in situations involving rapid movement. DVS has a number of benefits over conventional high-speed cameras, one of which being their incredibly low data rate, which qualifies them for real-time applications. | Despite these capabilities, integrating DVS sensors with UAVs remains a challenge, especially on the issues of real-time processing and data synchronization [23]. Lack of standardized datasets is also making it difficult to evaluate the performance of DVS camera-based UAV applications [30]. |

| Asynchronous Time-based Image Sensors (ATIS) [31] | ATIS combines the capability of capturing absolute intensity levels with event detection. Not only can ATIS record events that are prompted by brightness variations, but it can also record the scene's actual brightness at particular times. Rebuilding intensity images alongside event data is made possible by this hybrid technique, which enables greater information acquisition and is especially helpful for applications that need both temporal precision and intensity information. | Data from an event-based ATIS camera can be noisy, especially in low light conditions. So, there is a need for an efficient noise filtering model to address this [32] |

| Dynamic and Active Pixel Vision Sensors (DAVIS) [33] | DAVIS sensors combine traditional active pixel sensors (APS) and DVS capability. Because of its dual-mode functionality, DAVIS may be used as an event-based sensor to identify changes in brightness or as a conventional camera to record full intensity frames. DAVIS's dual-mode capacity makes it adaptable to a variety of scenarios, including those in which high-speed motion must be monitored while retaining the ability to capture periodic full-frame photos. | This capability of combining both APS and DVS capability poses challenges in complex data integration and sensor fusion [34] |

| Colour Event Cameras [35] | Color event cameras are one of the more recent innovations that increase the functionality of traditional DVS by capturing color information. These sensors enable the camera to record color events asynchronously by detecting changes in intensity across various color channels using a modified pixel architecture. This breakthrough enables event cameras to be utilized in more complicated visual settings where colour separation is critical. | There is scarcity of comprehensive dataset repository specifically for training and evaluating models that use this camera [36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).