1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia, significantly increasing the risk of stroke, heart failure, and death [

1,

2,

3]. Early detection and risk stratification are crucial for improving patient outcomes [

4]. While various risk factors and biomarkers for AF have been identified [

5], their predictive value remains a subject of ongoing research, particularly in patients already presenting with other forms of arrhythmia.

Troponin I (TnI) is a well-established biomarker for myocardial injury and is central to the diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes [

6,

7]. The development of high-sensitivity troponin I (hs-TnI) assays has enabled the detection of even minute elevations in troponin levels, reflecting subtle subclinical myocardial damage [

6]. Recent studies have suggested that these low-level elevations of hs-TnI, even in the absence of acute ischemia, may be indicative of chronic atrial remodeling and fibrosis - pathophysiological processes known to be fundamental to the development and maintenance of AF [

8,

9].

Current literature has explored the association between elevated hs-TnI and the incidence of new-onset AF in the general population and in specific high-risk groups, such as patients with heart failure or post-cardiac surgery [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Several studies have shown a positive correlation, with higher baseline hs-TnI levels being independently associated with a greater risk of developing AF [

10,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, a significant gap remains in understanding the specific role of hs-TnI as a prognostic marker for the development of AF in a cohort of patients with pre-existing arrhythmias other than AF. This specific population is at an inherently higher risk for arrhythmia-related complications, and a predictive biomarker could be invaluable for targeted monitoring and prophylactic strategies.

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the predictive value of high-sensitivity Troponin I for the development of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with other existing arrhythmias. By evaluating the relationship between baseline hs-TnI levels and subsequent AF events, this research aims to determine whether hs-TnI can serve as a useful tool for early risk stratification and guide management strategies for this vulnerable patient population.

Study Design and Setting

This was a prospective, single-center, observational cohort study designed to evaluate the association between baseline high-sensitivity Troponin I (hs-TnI) levels and the incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients presenting with non-AF arrhythmias. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Study Population and Recruitment

Patients were recruited from the outpatient Arrhythmia Treatment Department clinics at Cho Ray Hospital from December 2024 to June 2026.

Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

Prior documented history of Atrial Fibrillation or Atrial Flutter.

Diagnosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) [

16] or revascularization within the preceding six months.

Severe chronic kidney disease (estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73m2) [

17].

Active systemic inflammatory disease or malignancy.

Life expectancy less than 12 months due to a non-cardiac condition.

Baseline Data Collection and hs-TnI Measurement

At the time of enrollment, comprehensive clinical data were collected, including demographics (age, sex, BMI), cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia), echocardiographic parameters (left atrial volume index, left ventricular ejection fraction), and concurrent medications.

A blood sample was drawn from each patient at the time of the baseline visit. Serum hs-TnI concentration was measured using a validated high-sensitivity assay, specifically the Siemens Centaur XPT High Sensitive Troponin-I assay. The lower limit of detection (LoD) for this assay is 1,6 ng/L, and the 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL) is 47,34 ng/L. Assays were performed in a blinded fashion by laboratory personnel unaware of the patients’ clinical status.

Follow-up and Outcome Assessment

Participants were followed for 12 months during scheduled follow-up visits. At each follow-up visit, patients underwent a physical examination, review of symptoms, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG).

The Primary Outcome was the incidence of new-onset Atrial Fibrillation (AF) or Atrial Flutter (AFL). AF/AFL was defined as any episode lasting for ≥30 seconds, documented by ECG, 24-hour Holter monitoring, or continuous rhythm device interrogation (for patients with pre-existing implanted devices) [

18].

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or as the median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups (e.g., patients who did versus did not develop AF) were performed using the Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables.

The primary analysis used Cox Proportional Hazards Regression to assess the predictive relationship between baseline hs-TnI levels and time to incident AF/AFL. Initial analysis included hs-TnI as a continuous variable after log-transformation, and subsequent analysis categorized hs-TnI based on the 99th percentile URL. The final multivariate model was adjusted for clinically relevant confounders identified at baseline, including age, gender, left atrial volume index, and history of heart failure or hypertension.

AF survival rates were estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and differences between hs-TnI groups were assessed using the Log-Rank Test. Proportional hazards assumptions were verified using Schoenfeld residuals. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R software version 4.5.1.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocol was fully reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (Approval Number: Decision No. 806/HDĐĐ-ĐHYD dated September 22, 2023). All potential participants received a thorough explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained from every participant before any study procedure commenced. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without affecting their medical care.

To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, all patient data collected were coded with a unique study ID. Personal identifying information was stored separately from clinical data in a secure, password-protected database accessible only to the research team. Aggregate data were used for publication. Furthermore, a plan was established for the appropriate clinical referral and management of any incidental findings or clinically significant changes detected during the follow-up period (e.g., highly elevated hs-TnI values suggesting acute pathology or detection of life-threatening arrhythmias).

1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

From an initial pool of 285 patients, the study enrolled 232 individuals. This was after excluding 41 patients with a history of atrial fibrillation (AF) and 12 patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR < 30 ml/min/m²). The median follow-up period for the remaining patients was 12 months, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 6.75 to 13 months.

The study included 232 patients, with a near-equal distribution of 124 males (53.4%) and 108 females (46.6%). The average age of the entire group was 63.7 years, with a median of 67. Females were significantly older, with an average age of 67.5 years, compared to 60.4 years for males. Physical characteristics also varied by gender. On average, males were taller (1.63 m) and heavier (61.4 kg) than females (1.55 m and 53.3 kg, respectively). The group's average BMI was 22.5 kg/m², which is considered a healthy weight. Both systolic (129 mmHg) and diastolic (75.1 mmHg) blood pressure readings were stable and within a healthy range. However, females tended to have slightly higher blood pressure, which may be linked to their older average age. (

Table 1)

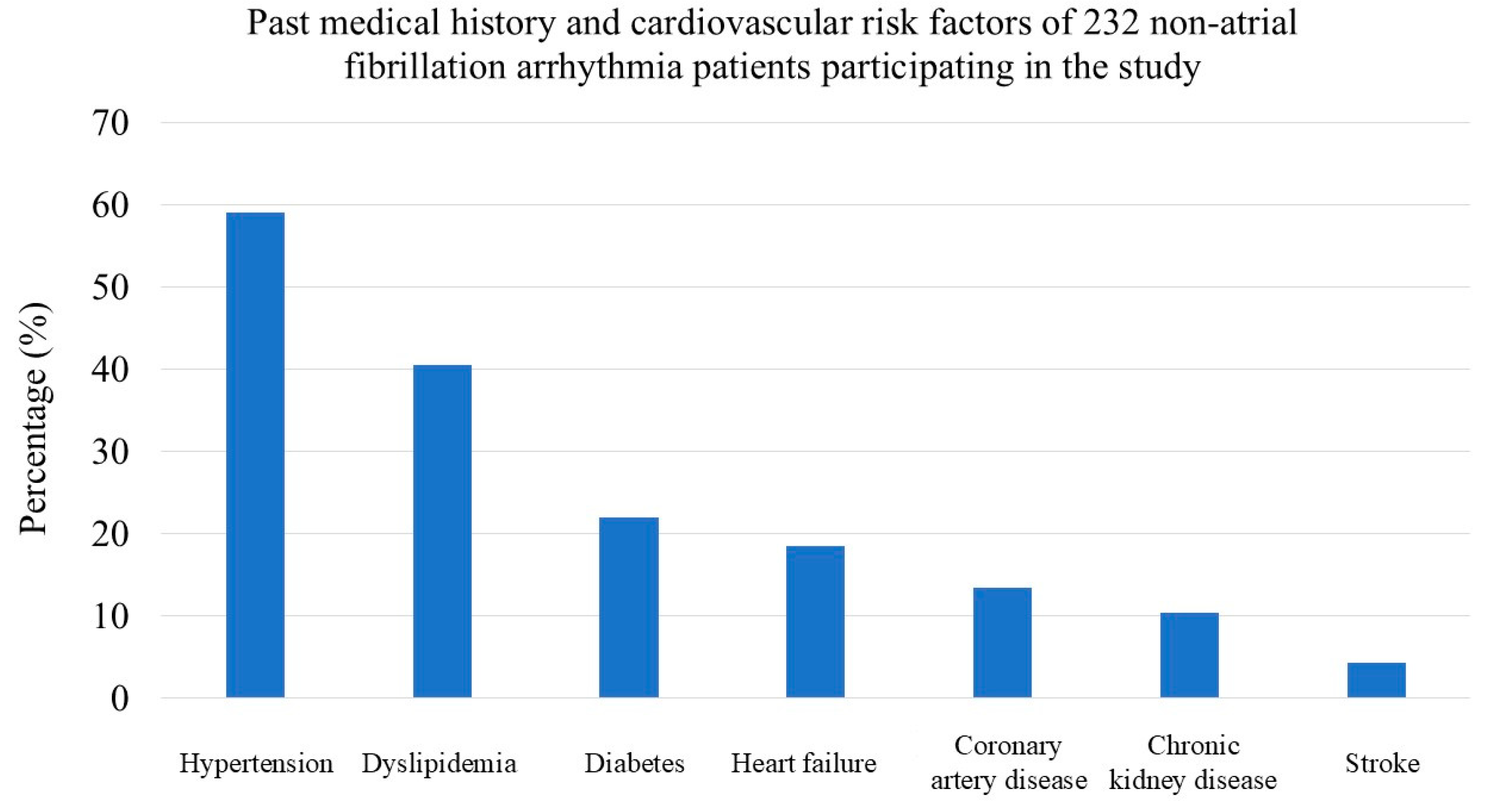

Hypertension was the most common cardiovascular risk factor, affecting 59.0% of patients. Dyslipidemia (40.5%) and diabetes mellitus (22.0%) were also prevalent. A significant portion of the patients also had a history of heart failure (18.0%), coronary artery disease (13.4%), and chronic kidney disease (10.3%). The most frequent symptoms upon presentation were syncope (59.9%) and dizziness (55.6%), each reported by over half of the patients. (

Figure 1,

Table 2)

2. Laboratory and Paraclinical Findings

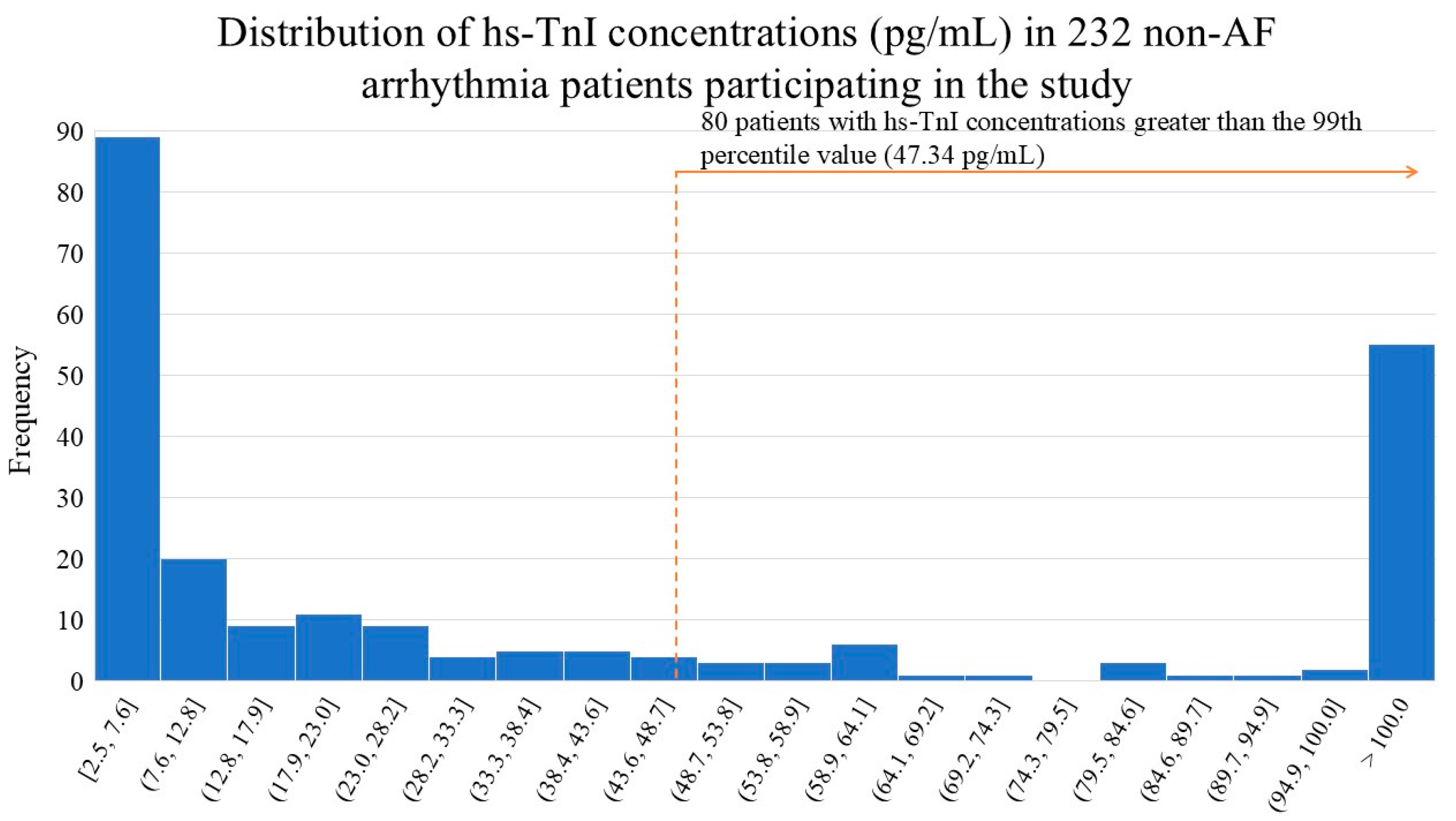

The median (interquartile range) hs-TnI concentration in the study patient group was 16.1 (4.54-90.0) pg/mL. The histogram illustrates the distribution of high-sensitivity troponin I (hs-TnI) concentrations in a study of 232 non-AF arrhythmia patients (

Figure 2). The data shows a heavily skewed distribution, with a large number of patients having very low hs-TnI levels. A significant portion of the patients (80 individuals) had hs-TnI concentrations above the 99th percentile cutoff (47.34 pg/mL), which is highlighted in the figure. This indicates that a substantial number of patients in this study cohort had elevated hs-TnI levels, which may warrant further investigation to determine the clinical implications of these findings.

Other lab results for the patients were largely normal. Kidney function was well-preserved, with a median creatinine of 0.87 mg/dL and a median eGFR of 83.9 mL/min/1.73m². Lipid levels (cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides) were also within the average range. Echocardiogram results showed that the patients' overall heart function was preserved, with a median left atrial size of 31 mm and a median ejection fraction of 65%. (

Table 3)

3. Atrial Fibrillation Status After Follow-up

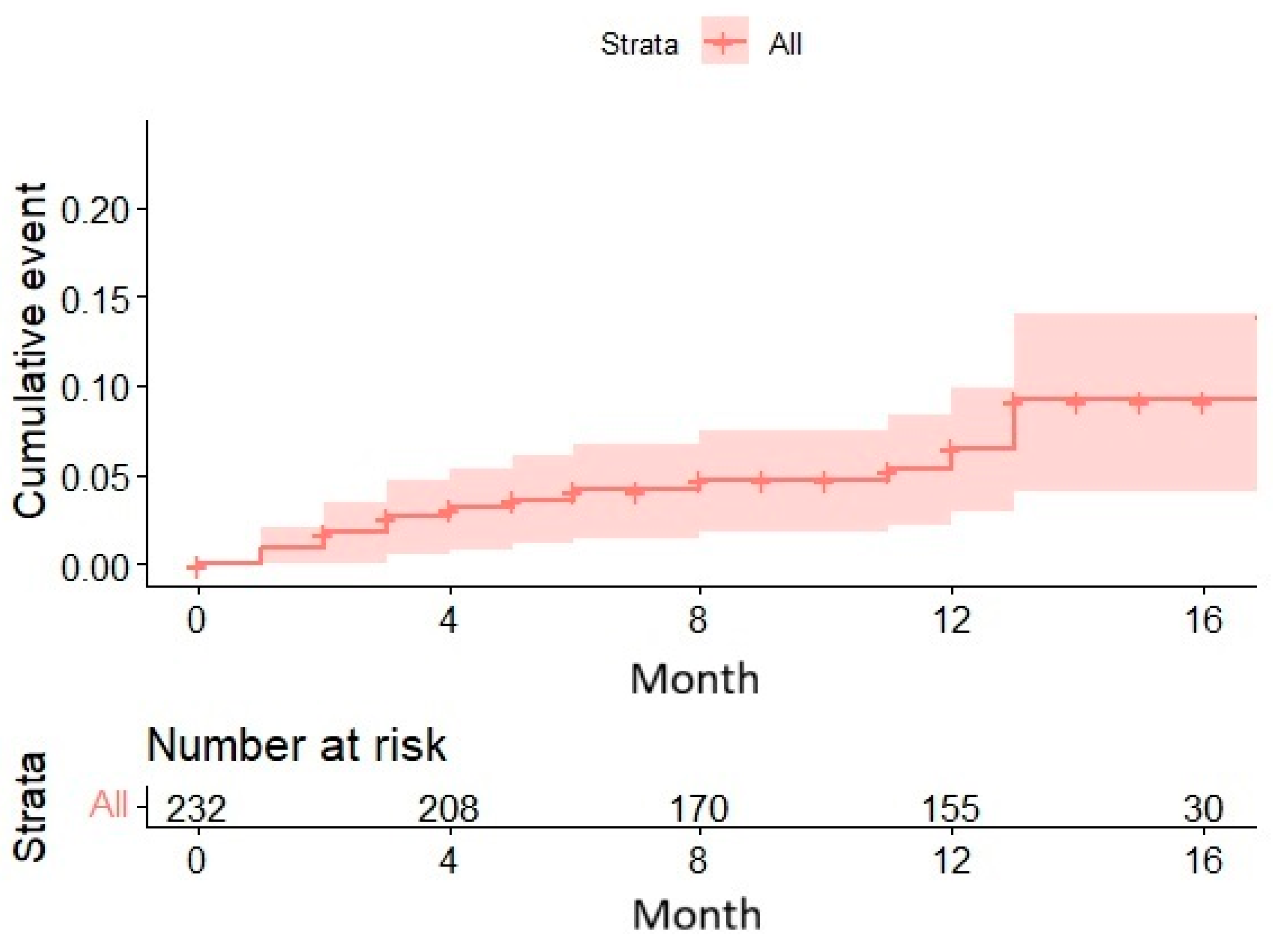

After a median follow-up period of 12 months, 16 cases (6.9%) of new-onset atrial fibrillation developed among the 232 baseline patients.

The Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrated a gradual increase in the cumulative incidence of AF over time, reaching nearly 10% after 12 months. The 95% confidence intervals were narrow initially but widened progressively, indicating that the precision of the estimate decreased as the number of remaining patients diminished. The patient count declined significantly over time: from 232 at baseline to just 19 at 17 months, due to events or loss to follow-up. (

Figure 3)

4. Role of hs TnI and Predictors of Atrial Fibrillation

From the initial 232 patients without atrial fibrillation (AF), 16 cases of new-onset AF were observed. The baseline hs-TnI concentration (pg/mL) in these 16 cases was a median (IQR) of 40.3 (4.61-98.9). This was higher, but not statistically significant, compared to the 216 patients who did not develop AF, whose median (IQR) was 16.5 (4.63-85.5), with a p-value of 0.205 using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

The Kaplan-Meier curves show a clear trend: higher hs-TnI levels, categorized by quartiles, are associated with an increased risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF). The highest quartile had a significantly higher cumulative event rate, reaching about 15% by 12 months. In contrast, the lowest quartiles had very few events throughout the study. The third quartile showed a moderate increase in events, but their rate was still much lower than the highest quartile. Despite this clear trend, the association was not statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.07. (

Figure 4)

After analyzing several variables, a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model identified three independent predictors for the risk of developing atrial fibrillation (AF):

Left Atrial (LA) Size: This was the most significant predictor (HR = 1.27, p < 0.001). The risk of AF increased with every millimeter increase in left atrial size.

History of Diabetes Mellitus: Patients with a history of diabetes were at a nearly 6-fold higher risk of developing AF (HR = 5.99, p = 0.006).

History of Stroke: This was a strong risk factor, increasing the risk of AF more than 10-fold for those with a prior stroke (HR = 10.18, p = 0.032).

Other factors, including NT-proBNP, age, sex, hypertension, heart failure, and eGFR, were not found to be statistically significant predictors of AF risk in this model. While a history of myocardial infarction showed a high hazard ratio (HR = 5.12), it did not meet the threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.094). (

Table 4)

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this prospective, single-center study was to investigate the predictive value of baseline hs-TnI for the development of new-onset AF in a vulnerable cohort of 232 patients presenting with other non-AF arrhythmias. Our central hypothesis was that elevated hs-TnI levels, reflecting subclinical myocardial injury and remodeling, would be independently associated with a higher risk of incident AF during the 12-month follow-up.

While 16 cases (6.9%) of new-onset AF were observed, and initial Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a notable trend - the highest hs-TnI quartile had a cumulative AF rate of approximately 15% compared to near-zero rates in the lowest quartiles - this association did not reach statistical significance in the adjusted Cox regression model (p = 0.844). Instead, the multivariate analysis revealed three strong, independent predictors of new-onset AF: Left Atrial (LA) size (HR = 1.27, p < 0.001), History of Diabetes Mellitus (HR = 5.99, p = 0.006), and History of Stroke (HR = 10.18, p = 0.032).

Our findings both align with and diverge from established literature regarding AF prediction. The high predictive power of LA size is consistent with numerous studies recognizing left atrial enlargement as the single strongest morphological substrate for AF due to increased wall stress, fibrosis, and conduction heterogeneity [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Similarly, the significant hazard ratios observed for Diabetes Mellitus (HR ≈ 6) and History of Stroke (HR ≈ 10) reinforce their roles as powerful systemic and embolic risk factors, likely mediated through mechanisms such as diabetic cardiomyopathy and atrial stunning post-stroke [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

Conversely, our result showing no statistically significant independent association between baseline hs-TnI and incident AF contrasts with several large population studies that reported a clear link between even low-level troponin elevation and future AF risk. For instance, some studies found hs-TnI to be an independent predictor in cohorts with heart failure or general cardiovascular disease [

10,

12,

13,

15]. The disparity in our results, however, may be partially explained by the specific nature of our cohort—patients with pre-existing, often symptomatic, non-AF arrhythmias. This patient group likely already harbors a high baseline burden of atrial remodeling that might override the incremental prognostic value of a single baseline hs-TnI measurement over a short follow-up period.

The strong, albeit non-significant, trend observed in the Kaplan-Meier analysis (

Figure 4) suggests that while hs-TnI may reflect underlying pathology, its predictive utility in this specific high-risk arrhythmia cohort is eclipsed by established structural (LA size) and systemic (Diabetes, Stroke) risk factors.

The model’s preference for LA size and Diabetes as predictors suggests that the final common pathway to new-onset AF in this group is dominated by advanced atrial remodeling. A key hypothesis emerging from this work is the potential role of dynamic troponin changes. While baseline hs-TnI may capture static myocardial health, a new model could investigate whether the rate of change or serial measurements of hs-TnI over time better reflect rapid or progressive atrial injury that precipitates AF. In this already compromised population, small, acute spikes in hs-TnI may be more relevant than a single baseline value.

Furthermore, the non-significant but notable high Hazard Ratio for History of Myocardial Infarction (HR ≈ 5.1, p = 0.094) suggests that with a larger sample size, this factor, which is clearly linked to myocardial stress and fibrosis, may reach significance, supporting a broader mechanism of global myocardial strain leading to AF.

Our findings have crucial implications for the risk stratification of patients presenting with non-AF arrhythmias. The results strongly suggest that risk assessment should be driven primarily by structural parameters, particularly LA size, and major cardiovascular comorbidities like Diabetes and prior Stroke. Clinicians should aggressively screen for AF in arrhythmia patients who present with any of these three factors. Given the 10-fold increased risk associated with a history of stroke, enhanced and continuous rhythm monitoring (e.g., implantable loop recorders) is warranted in this specific subset to prevent recurrent stroke.

While hs-TnI did not emerge as an independent predictor in this specific model, the finding that 80 patients (over one-third of the cohort) had hs-TnI levels above the 99th percentile cutoff is clinically relevant, indicating a high prevalence of subclinical myocardial injury in patients with non-AF arrhythmias. This underscores the need to address underlying cardiovascular comorbidities vigorously, even if the troponin value itself does not independently predict AF in this model.

This study possesses several strengths, including its prospective cohort design and the focus on a highly specific, high-risk patient population (non-AF arrhythmia patients). We used a validated high-sensitivity assay for hs-TnI and employed a robust multivariate Cox regression model adjusted for major confounders. The clear exclusion of patients with pre-existing AF and severe renal impairment (eGFR<30 ml/min/m2) ensures a purer assessment of new-onset AF risk.

The study also has limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small (N = 232), and the number of incident AF events was low (n=16), which may have contributed to the borderline statistical significance observed for variables like hs-TnI and Myocardial Infarction history. Second, the median follow-up period was relatively short (12 months), meaning late-onset AF may have been missed. Third, the diagnosis of AF relied primarily on scheduled follow-up ECGs and Holter monitoring, potentially missing asymptomatic, paroxysmal AF episodes between visits. Lastly, the study’s single-center origin may limit the generalization of the findings to more diverse populations

5. Conclusions

In this prospective cohort of patients with non-AF arrhythmias, baseline hs-TnI was not found to be an independent predictor of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF) during the 12-month follow-up period. Instead, the risk of developing AF was overwhelmingly predicted by established clinical and structural factors. Specifically, Left Atrial (LA) size, a History of Diabetes Mellitus, and a History of Stroke emerged as powerful, independent predictors of incident AF.

These findings suggest that in patients already presenting with other arrhythmias - a population likely to have significant underlying atrial pathology - risk stratification for future AF should prioritize structural changes and major comorbidities over a single baseline measurement of hs-TnI. Clinically, aggressive screening and management strategies should be focused on arrhythmia patients exhibiting LA enlargement, diabetes, or a history of stroke to mitigate the substantial associated AF risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.V.L. and D.H.K.L.; methodology, T.V.L.; software, T.V.L.; validation, T.V.L., S.D., and D.H.K.L.; formal analysis, T.V.L.; investigation, T.V.L. and S.D.; resources, S.D.; data curation, T.V.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.V.L.; writing—review and editing, D.H.K.L.; visualization, T.V.L.; supervision, D.H.K.L.; project administration, D.H.K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (protocol code Decision No. 806/HDĐĐ-ĐHYD and date of approval 22 September 2023). The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT06174506).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the individuals and organizations that contributed to the completion of this study. We are deeply grateful to The University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City for their institutional support. We extend sincere thanks to the leadership and staff of the Arrhythmia Treatment Department at Cho Ray Hospital for their support in patient recruitment and data collection. Special acknowledgement is due to the Department of Biochemistry at Cho Ray Hospital for their meticulous laboratory work, including the high-sensitivity Troponin I assays. Above all, we are immensely grateful to all 232 patients who volunteered; their cooperation made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AF |

Atrial Fibrillation |

| AFL |

Atrial Flutter |

| ACS |

Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| eGFR |

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| EF |

Ejection Fraction |

| HR |

Hazard Ratio |

| hs-TnI |

High-Sensitivity Troponin I |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| LA |

Left Atrial |

| LoD |

Lower Limit of Detection |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| URL |

Upper Reference Limit |

References

- Desai, D.S.; Hajouli, S. Arrhythmias. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Said Hajouli declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Buttner, E.B.a.R. Atrial Fibrillation. Available online: https://litfl.com/atrial-fibrillation-ecg-library/ (accessed on 21/08).

- Kornej, J.; Borschel, C.S.; Benjamin, E.J.; Schnabel, R.B. Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation in the 21st Century: Novel Methods and New Insights. Circ Res 2020, 127, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society, H.R. Guide to Atrial Fibrillation. 2014.

- Staerk, L.; Preis, S.R.; Lin, H.; Lubitz, S.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; Levy, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Trinquart, L. Protein Biomarkers and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: The FHS. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2020, 13, e007607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, D.R.; Lazar, F.L.; Homorodean, C.; Cainap, C.; Focsan, M.; Cainap, S.; Olinic, D.M. High-Sensitivity Troponin: A Review on Characteristics, Assessment, and Clinical Implications. Dis Markers 2022, 2022, 9713326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.C.; Gaze, D.C.; Collinson, P.O.; Marber, M.S. Cardiac troponins: from myocardial infarction to chronic disease. Cardiovasc Res 2017, 113, 1708–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maayah, M.; Grubman, S.; Allen, S.; Ye, Z.; Park, D.Y.; Vemmou, E.; Gokhan, I.; Sun, W.W.; Possick, S.; Kwan, J.M.; et al. Clinical Interpretation of Serum Troponin in the Era of High-Sensitivity Testing. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roongsritong, C.; Warraich, I.; Bradley, C. Common causes of troponin elevations in the absence of acute myocardial infarction: incidence and clinical significance. Chest 2004, 125, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borschel, C.S.; Geelhoed, B.; Niiranen, T.; Camen, S.; Donati, M.B.; Havulinna, A.S.; Gianfagna, F.; Palosaari, T.; Jousilahti, P.; Kontto, J.; et al. Risk prediction of atrial fibrillation and its complications in the community using hs troponin I. Eur J Clin Invest 2023, 53, e13950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Kwon, C.H.; Chang, H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Hwang, H.K.; Chung, S.M. Usefulness of High-Sensitivity Troponin I to Predict Outcome in Patients With Newly Detected Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2020, 125, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaura, A.; Arnold, A.D.; Panoulas, V.; Glampson, B.; Davies, J.; Mulla, A.; Woods, K.; Omigie, J.; Shah, A.D.; Channon, K.M.; et al. Prognostic significance of troponin level in 3121 patients presenting with atrial fibrillation (The NIHR Health Informatics Collaborative TROP-AF study). J Am Heart Assoc 2020, 9, e013684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Hung, J.; Divitini, M.; Murray, K.; Lim, E.M.; St John, A.; Walsh, J.P.; Knuiman, M. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I and risk of incident atrial fibrillation hospitalisation in an Australian community-based cohort: The Busselton health study. Clin Biochem 2018, 58, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costabel, J.P.; Burgos, L.M.; Trivi, M. The Significance Of Troponin Elevation In Atrial Fibrillation. J Atr Fibrillation 2017, 9, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filion, K.B.; Agarwal, S.K.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Eberg, M.; Hoogeveen, R.C.; Huxley, R.R.; Loehr, L.R.; Nambi, V.; Soliman, E.Z.; Alonso, A. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J 2015, 169, 31–38 e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.V.; O'Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, e771–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancioglu, R.; et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease: known knowns and known unknowns. Kidney Int 2024, 105, 684–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Writing Committee, M.; Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Chyou, J.Y.; Cronin, E.M.; Deswal, A.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Goldberger, Z.D.; et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 83, 109–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckin, O.; Unlu, S.; Yalcin, M.R. The hidden role of left atrial strain: insights into end-organ damage in dipper and nondipper hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 2025, 39, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parajuli, P.; Alahmadi, M.H.; Ahmed, A.A. Left Atrial Enlargement. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Mohamed Alahmadi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Andaleeb Ahmed declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bakir, E.O.; Yurdam, F.S.; Dolu, A.K.; Aguloglu, S. The relationship between the left atrium/left ventricle ratio and atrial fibrillation in patients with ischemic stroke without significant left atrial enlargement. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryabanshi, A.; Timilsina, B.; Shakya, S.; Khanal, S.; Yadav, V.; Joshi, A. Left Atrial Enlargement as a Predictor of Atrial Fibrillation in Rheumatic Mitral Valve Disease: An Echocardiography-based Retrospective Cross-sectional Study. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2024, 21, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, R.; Abu Jaber, B.; Alzuqaili, T.; Ghura, S.; Al-Ajlouny, T.; Saadeh, A.M. The relationship of atrial fibrillation with left atrial size in patients with essential hypertension. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopoulou, M.; Theofilis, P.; Kordalis, A.; Papageorgiou, N.; Sagris, M.; Oikonomou, E.; Tousoulis, D. Diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation-from pathophysiology to treatment. World J Diabetes 2023, 14, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed Ahmadi, S.; Svensson, A.M.; Pivodic, A.; Rosengren, A.; Lind, M. Risk of atrial fibrillation in persons with type 2 diabetes and the excess risk in relation to glycaemic control and renal function: a Swedish cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2020, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Green, J.B.; Halperin, J.L.; Piccini, J.P., Sr. Atrial Fibrillation and Diabetes Mellitus: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019, 74, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Feng, T.; Schlesinger, S.; Janszky, I.; Norat, T.; Riboli, E. Diabetes mellitus, blood glucose and the risk of atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Diabetes Complications 2018, 32, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dublin, S.; Glazer, N.L.; Smith, N.L.; Psaty, B.M.; Lumley, T.; Wiggins, K.L.; Page, R.L.; Heckbert, S.R. Diabetes mellitus, glycemic control, and risk of atrial fibrillation. J Gen Intern Med 2010, 25, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, A.Z.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; Carson, A.P.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, e153–e639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachmann, J.; Morillo, C.A.; Sanna, T.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Diener, H.C.; Bernstein, R.A.; Rymer, M.; Ziegler, P.D.; Liu, S.; Passman, R.S. Uncovering Atrial Fibrillation Beyond Short-Term Monitoring in Cryptogenic Stroke Patients: Three-Year Results From the Cryptogenic Stroke and Underlying Atrial Fibrillation Trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2016, 9, e003333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, T.; Diener, H.C.; Passman, R.S.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Bernstein, R.A.; Morillo, C.A.; Rymer, M.M.; Thijs, V.; Rogers, T.; Beckers, F.; et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 2478–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).