Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Procedure

2.1.1. Green Mesoporous Silica (GMS) Synthesis Starting Sodium Silicate

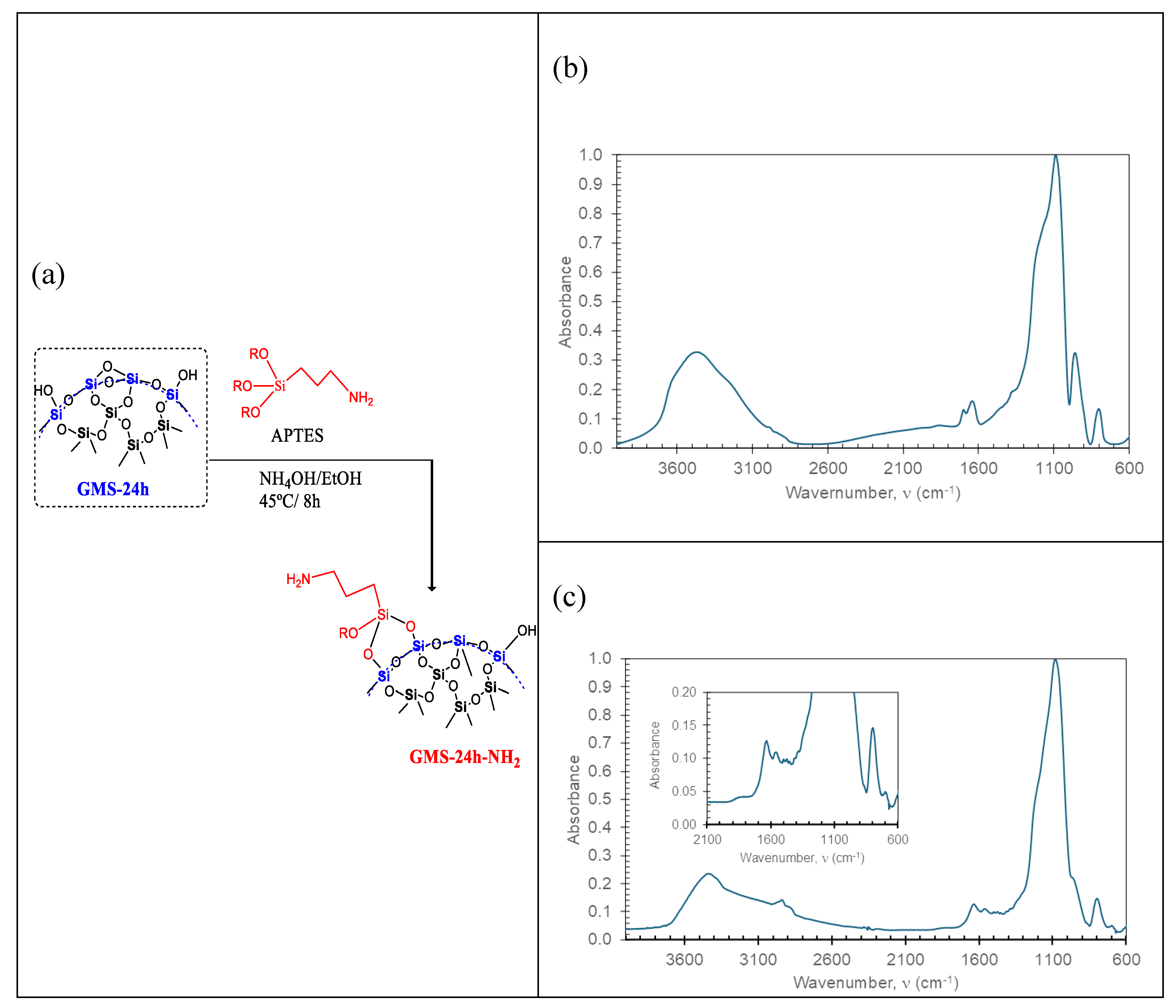

2.2. Functionalization of GMS with Amine Groups

2.3. Characterization Studies

2.4. Cr(III) Adsorption Studies

3. Results

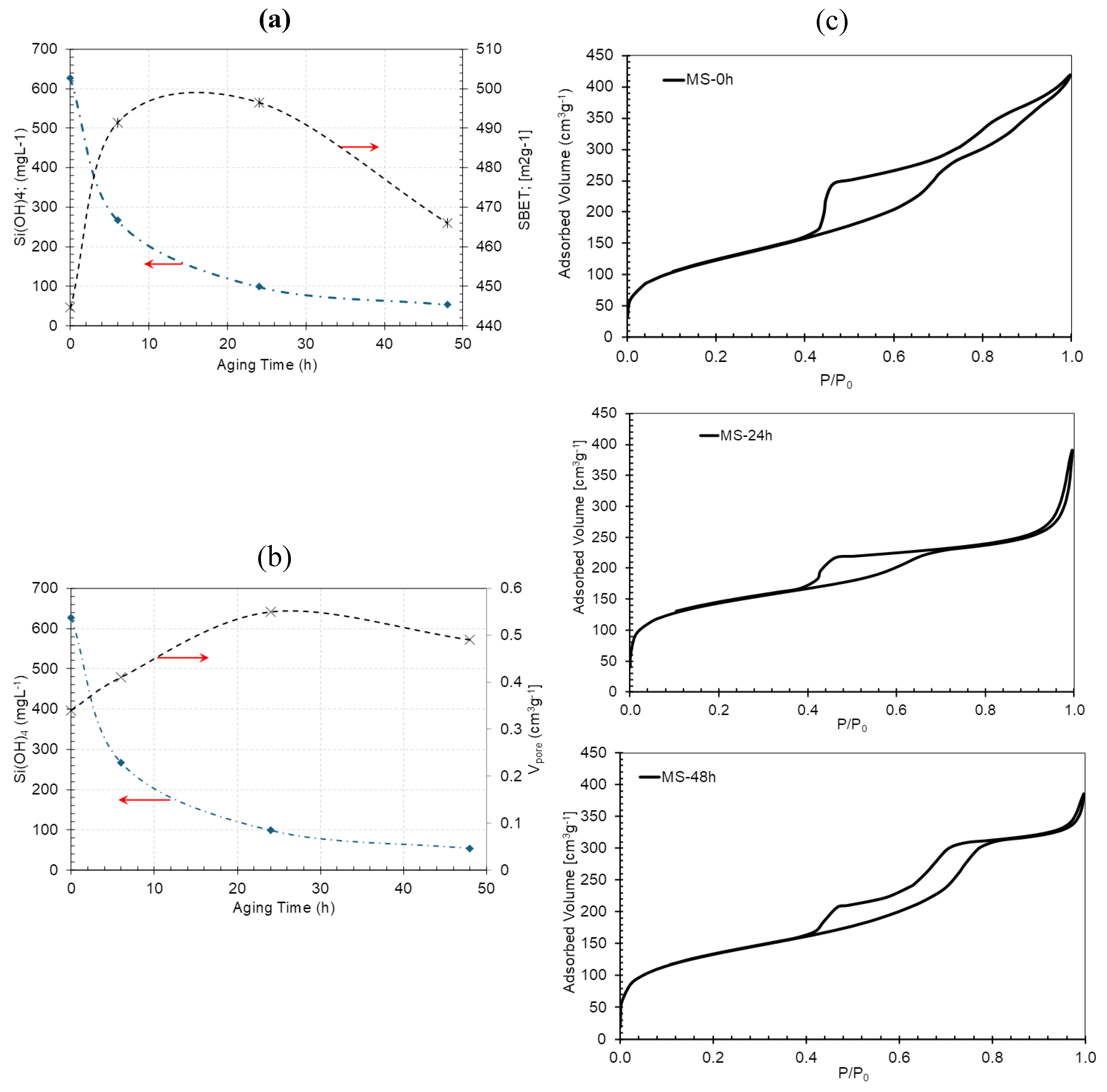

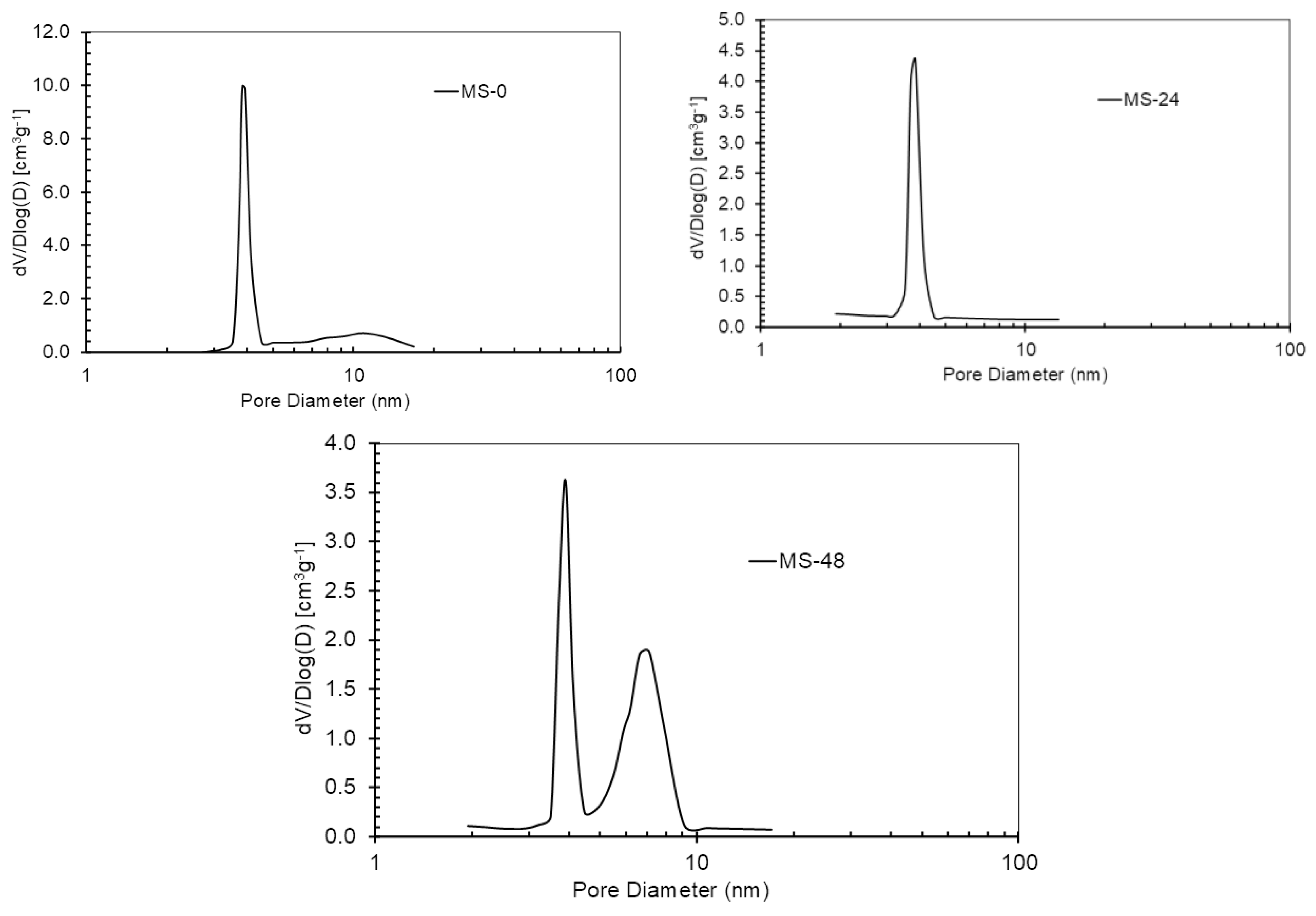

3.1. Effect of Aging on Textural Properties of GMS

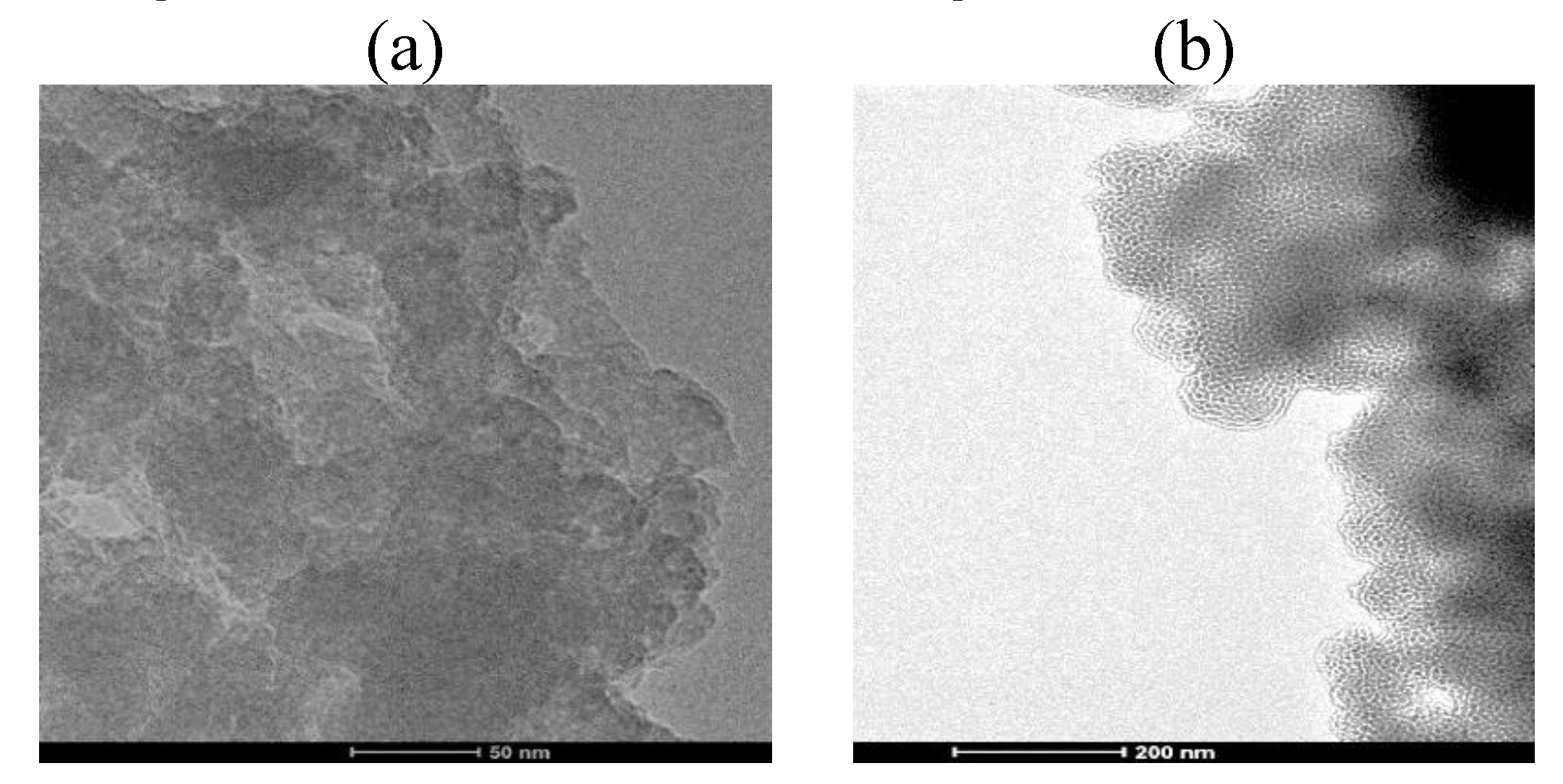

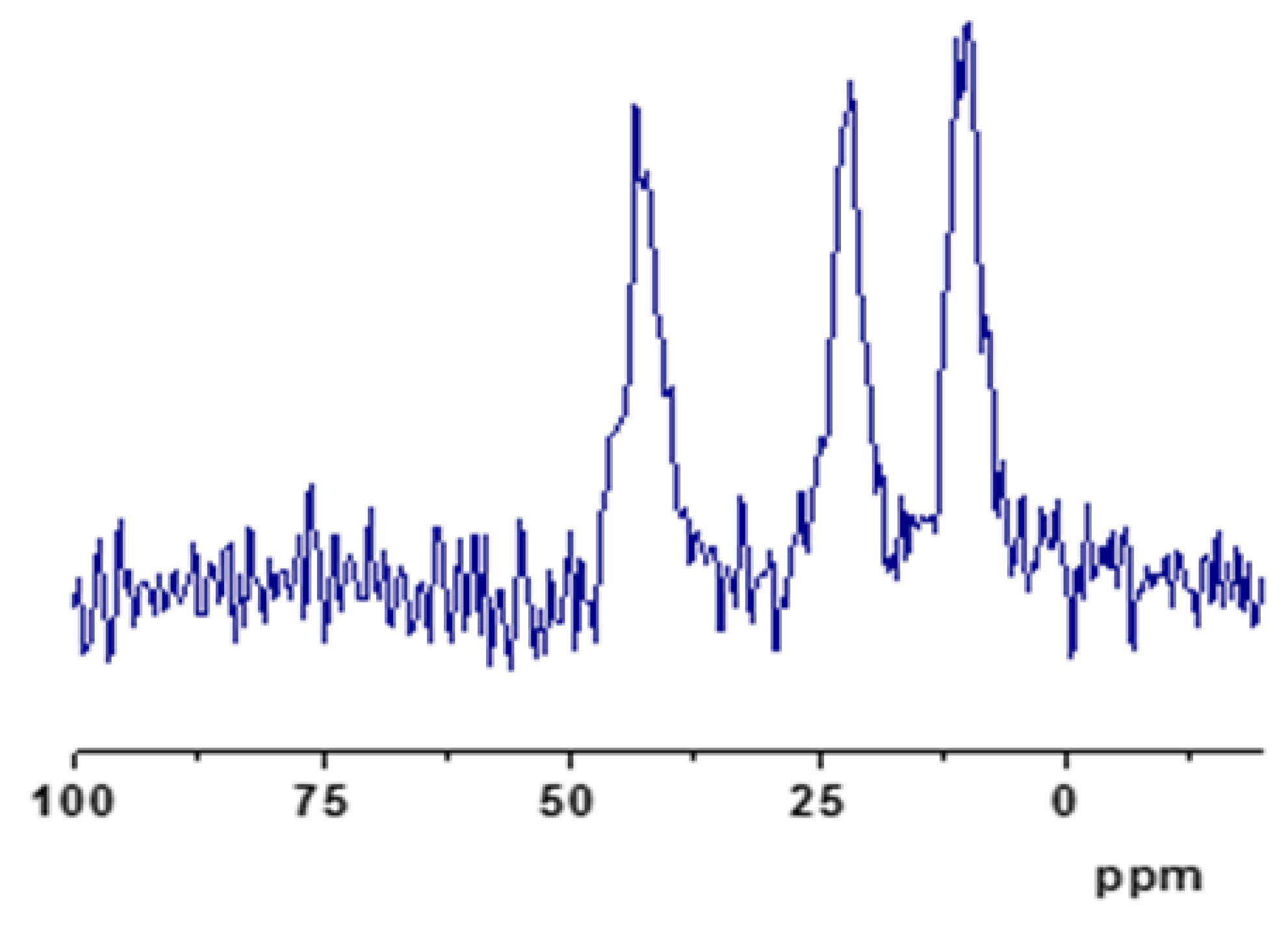

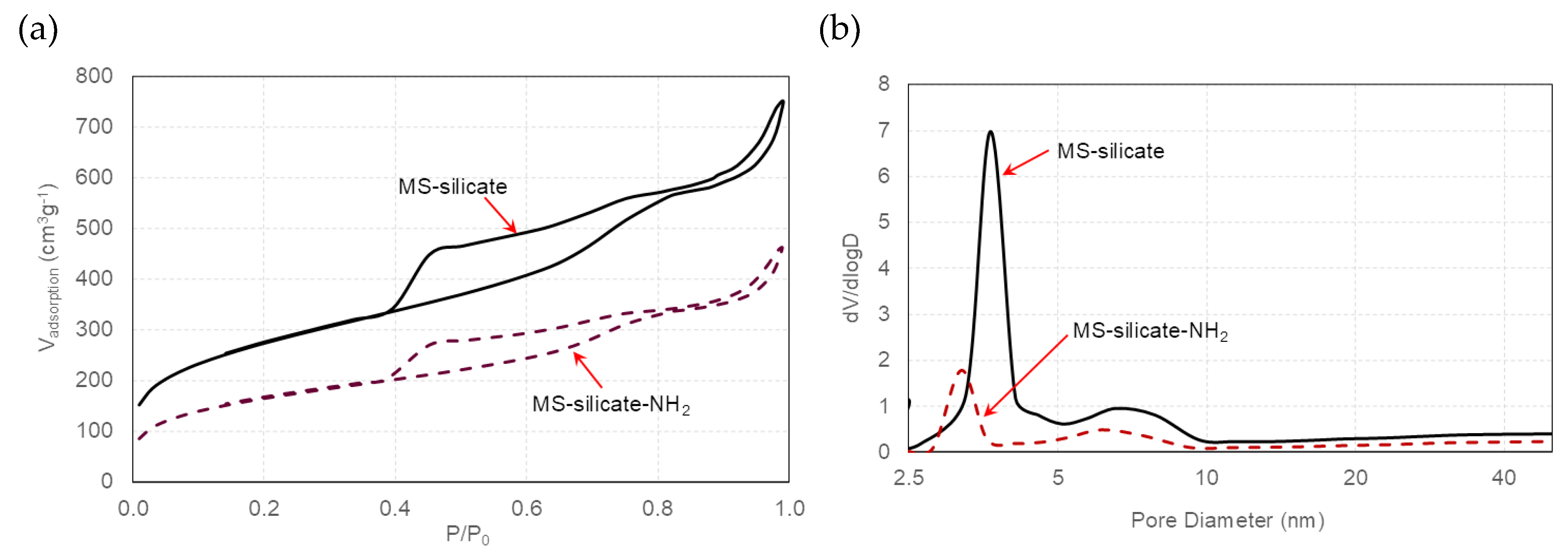

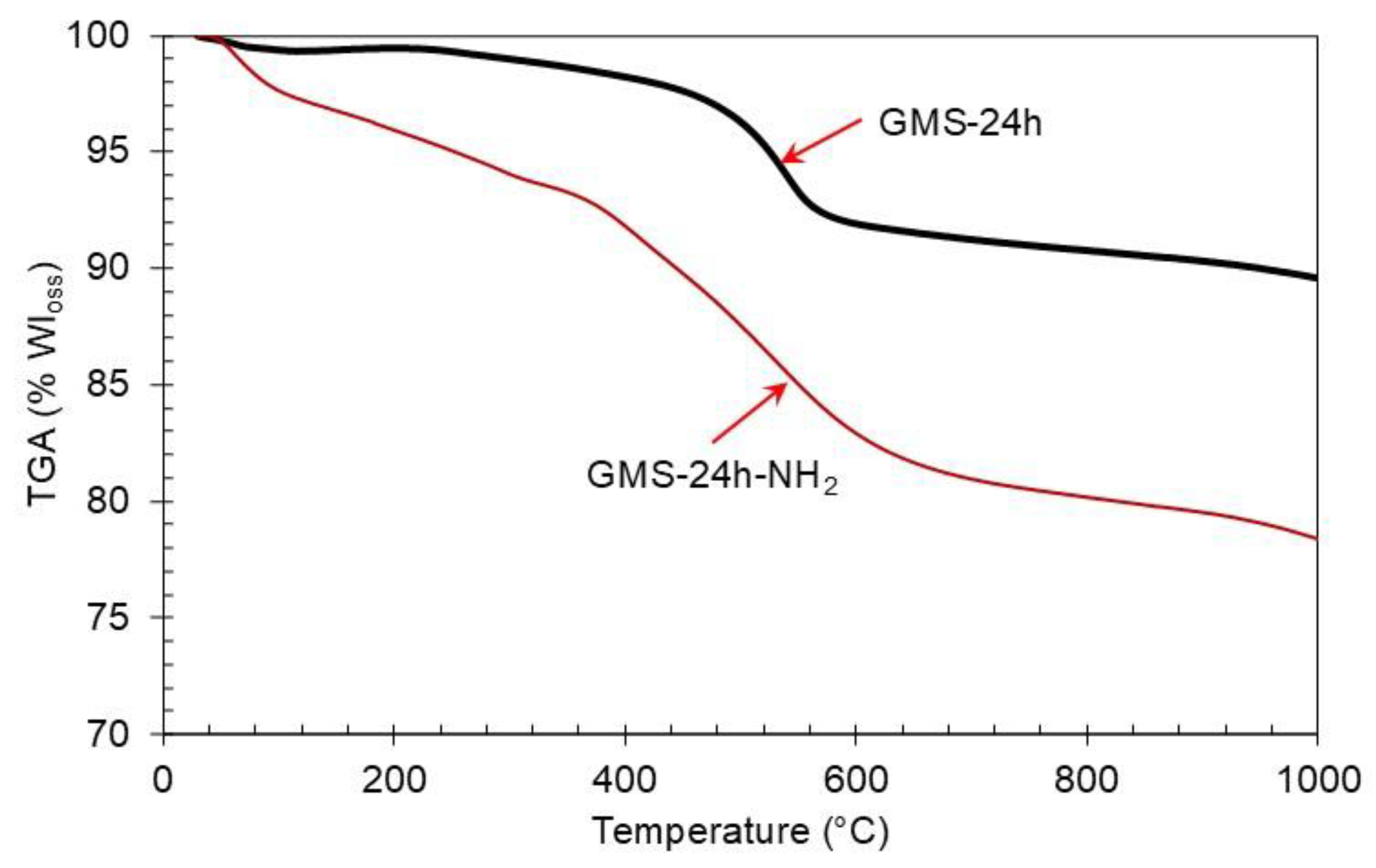

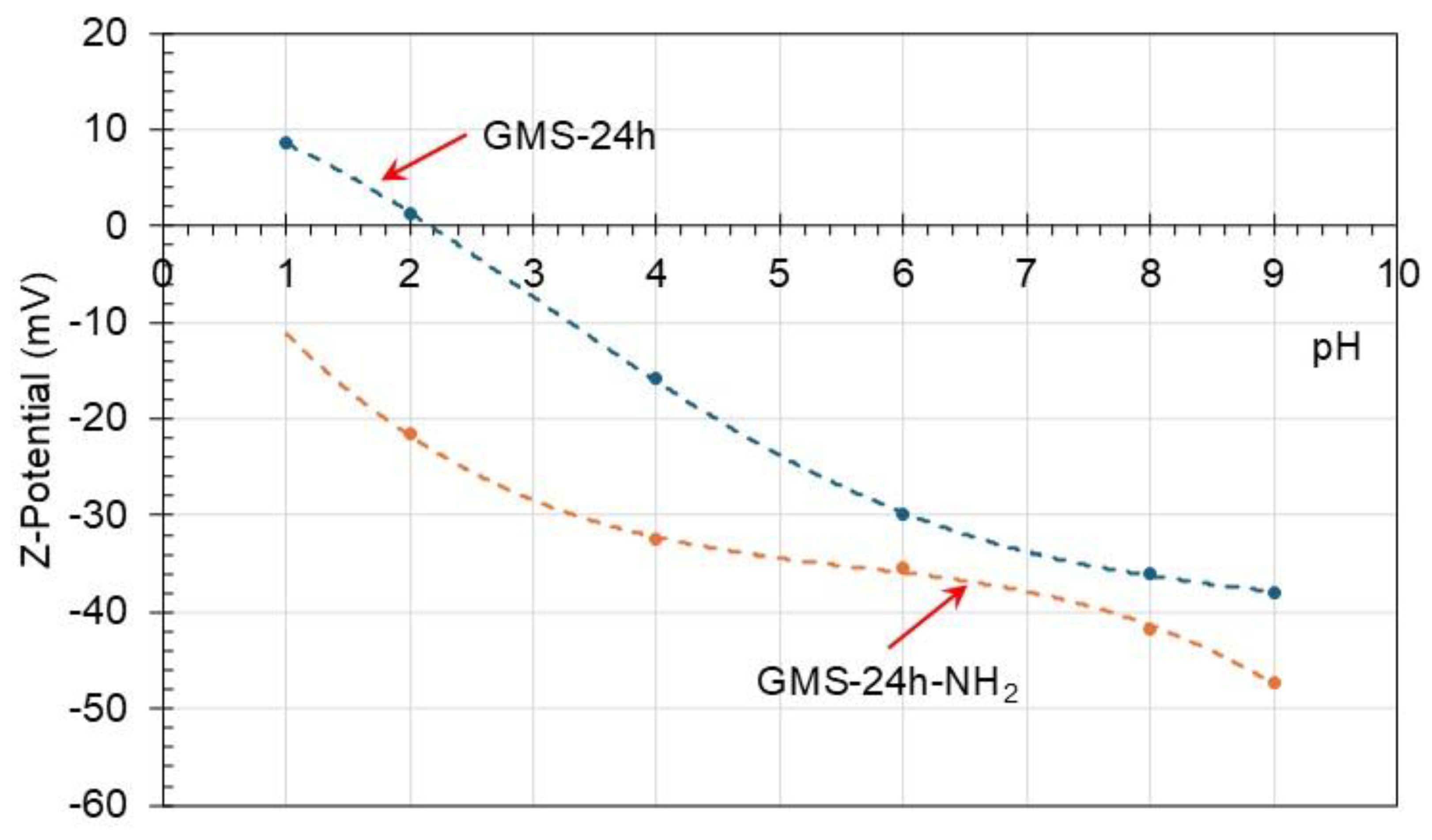

3.2. GMS Modification with Amine Groups

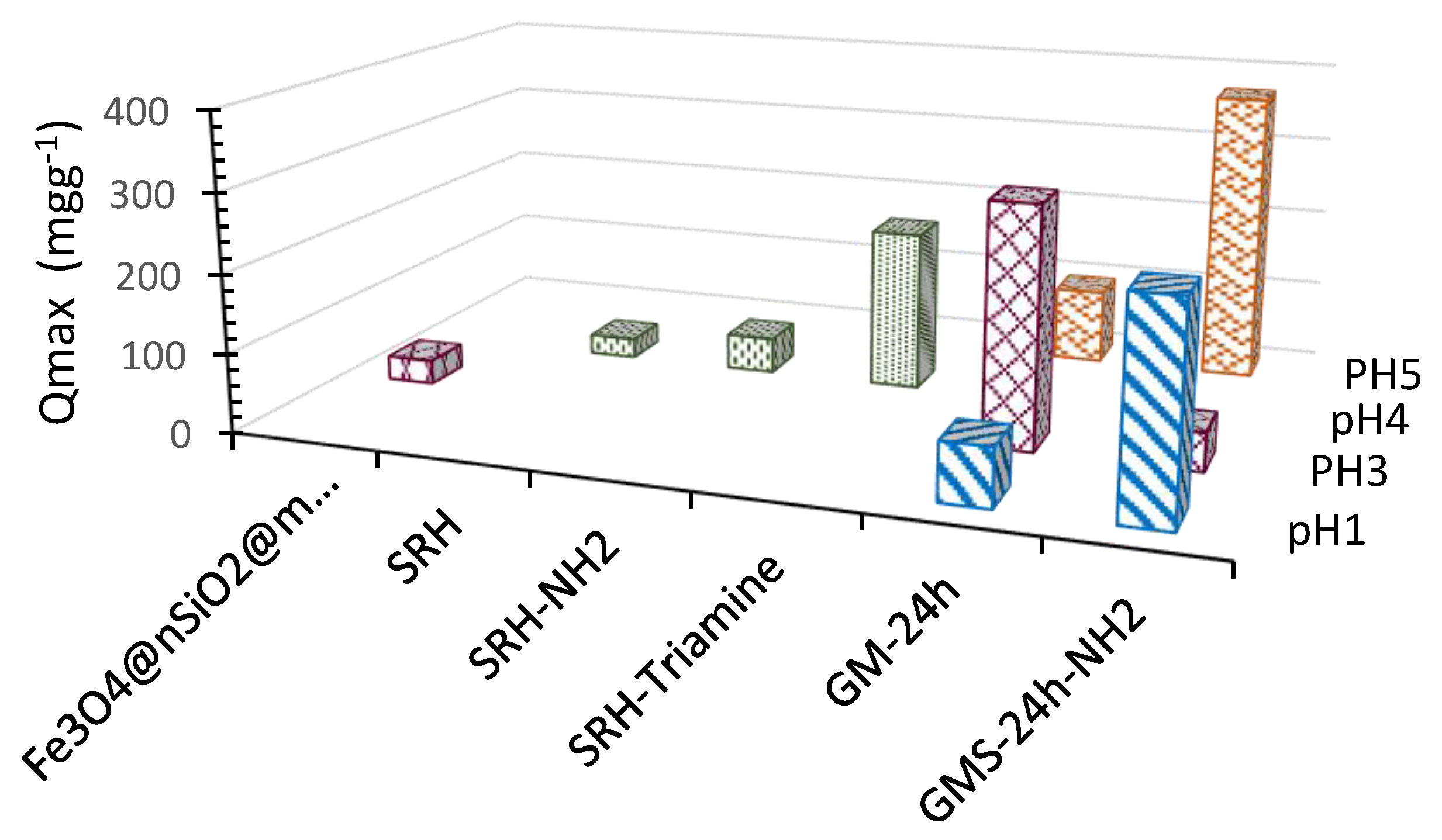

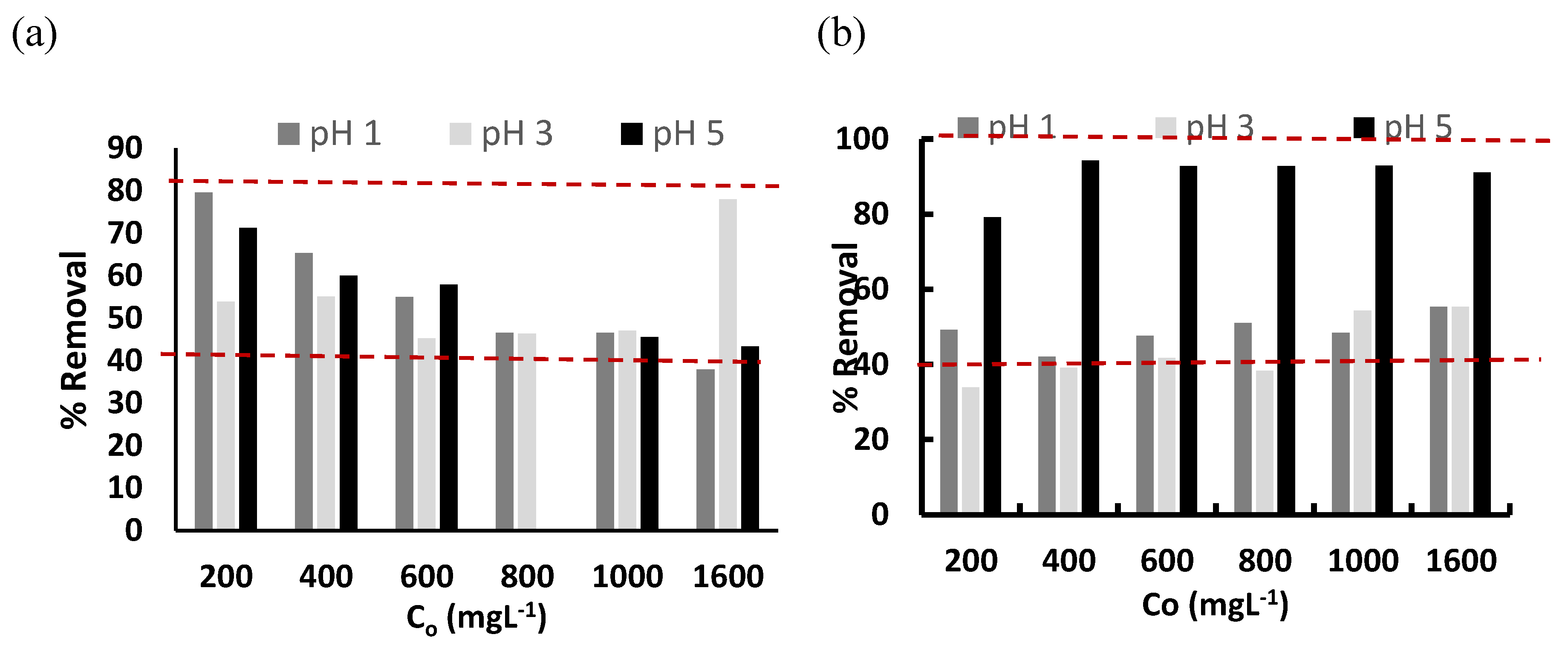

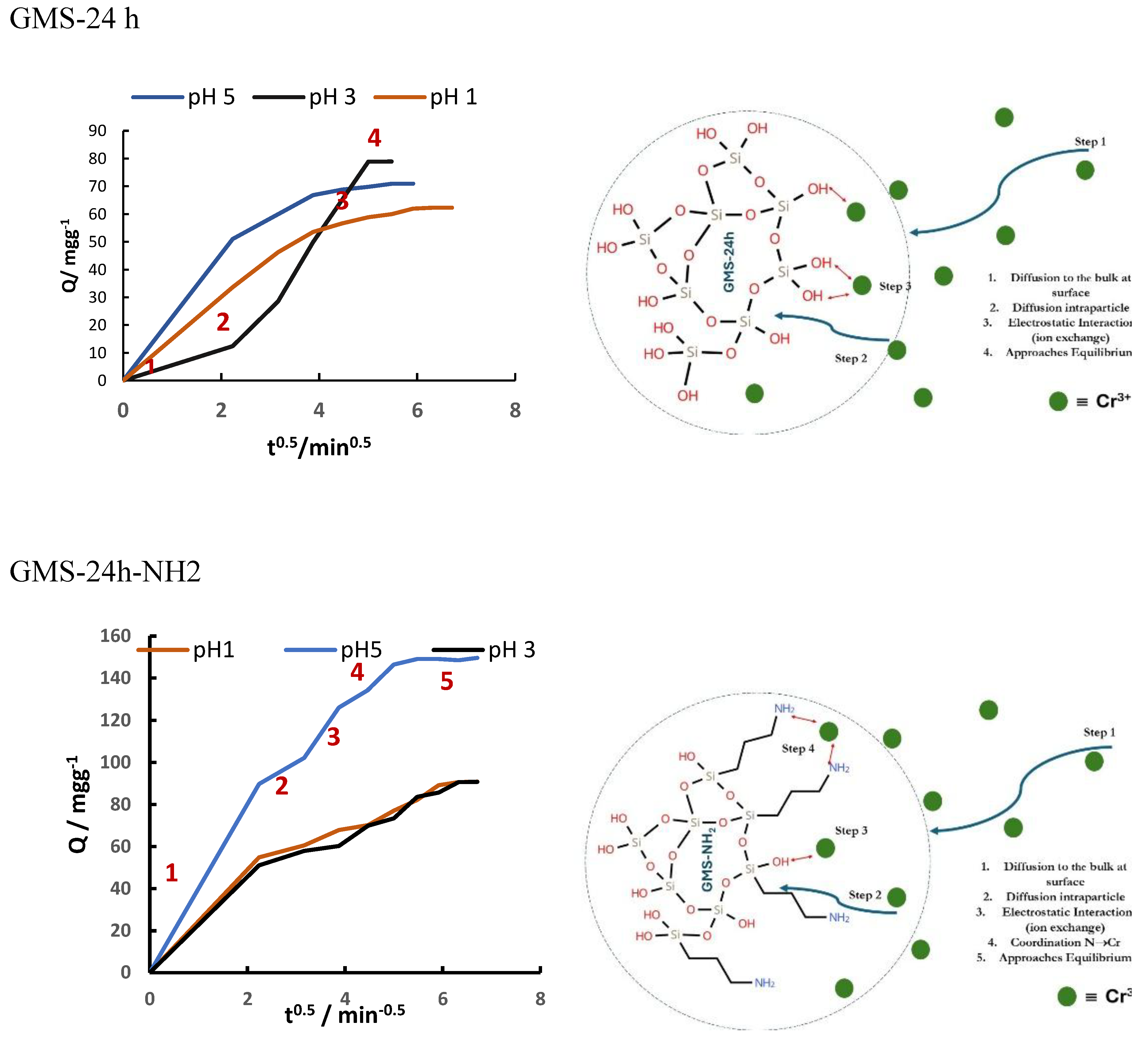

3.3. Cr(3+) Removal Using GMS-24h and GMS-24h-NH2

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shruthi, S.; Hemavathy, R.V. Myco-remediation of chromium heavy metal from industrial wastewater: A review. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 13, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Kamaraj, N.; Selvaraj, R.; Nanoth, R. Emerging trends and future outlook on chromium removal in the lab, pilot scale, and industrial wastewater system: An updated review exploring 10 years of research. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, J.; Xu, Q.; Liu, R.; Yang, F.; Xie, H. Synergistic oxygen vacancies and surface hydroxyl groups in NFM@γ-Al2O3 for enhanced catalytic ozonation of refractory organics and phosphorus in swine wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yin, M.; Du, W.; Zhang, S.; Wen, Z.; Yu, L.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, M.; Wang, X.; et al. Metal ion-induced structural reconstruction in a porphyrin MOF for ultrasensitive detection of Cr3+ and Al3+. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 344, 126624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, P.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Ma, S.; et al. Facile synthesis of polyethyleneimine-reinforced PHTA resin for efficient Cr(VI) removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosen, S.; Sahen, S.; Ahmed, H.; Reza, S.; Bhowmik, P.; Mim, F.; Islam, B.; Naim, A.H.K.; Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, M. Tannery shaving dust-based charcoal blended adsorbent for efficient heavy metal remediation: An experimental and machine learning approach. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, C.E.A.; Ruiz, Y.G.; Rios, J.F.U.; Escobar, E.G.L.; Rodrigues, M.A.S. Electrochemical separation of chromium/collagen from wet blue in a single step: Recycling of tannery waste to promote a circular economy. Results Eng. 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santis, A.; Arbeláez, O.; Mendivelso, K.; Riaño, M.; Prieto, V.; Velásquez, P. Sustainable innovation: Removal of chromium (VI) from wastewater from plastic chromium plating industries using rice husk as photocatalyst. Results Eng. 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, S.; Meenachi, S.; Ohm Prakash, K.; Kr, S.K.; Thamaraikannan, V. Removal of chromium from tannery wastewater by rice husk ash nanosilica. Appl. Res. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabago-Velasquez, Z.; Patiño-Saldivar, L.; A, A.N.A.; Talavera-Lopez, A.; Salazar-Hernández, M.; Hernández-Soto, R.; Hernández, J.A. Removal of Cr(III) from tannery wastewater using Citrus aurantium (grapefruit peel) as biosorbent. Desalination Water Treat. 2023, 283, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munagapati, V.S.; Wen, H.-Y.; Gutha, Y.; Wen, J.-C.; Venkateswarlu, S.; Yarramuthi, V.; Gollakota, A.R.; Shu, C.-M.; Lohith, E.; Jyothi, N. Advances in biocompatible chitosan composites for chromium, arsenic, and radionuclide remediation: Experimental and computational insights. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Mohamed, A.A. The use of chitosan-based composites for environmental remediation: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, Y.; Sun, D.; Wu, D.; Ban, L.; Zhang, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, J.; Du, H.; et al. Recent advances and perspectives in functional chitosan-based composites for environmental remediation, energy, and biomedical applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2025, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, S.; Liu, R.; Jiang, H.; Jing, S.; Zhuang, H. Smart-responsive chitosan-based materials for precise degradation control and environmental remediation: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 144982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathore, B.S.; Perumal, P.; Singh, G.P.; Rathore, R.; Rawal, M.K.; Jadoun, S.; Chauhan, N.P.S. Polyaniline, Chitosan and Metal Oxide based Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Characterization, and Their Water Remediation Applications. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purrostam, S.; Rahimi-Ahar, Z.; Babapoor, A.; Nematollahzadeh, A.; Salahshoori, I.; Seyfaee, A. Melamine functionalized mesoporous silica SBA-15 for separation of chromium (VI) from wastewater. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.D.; Feng, D.; Xu, J.; Gao, X.; Yan, K.; Tian, Z. Mesoporous silica modified zwitterionic poly(ionic liquids) with enhanced absorption for Cr3+ and dye as a tanning agent. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2025, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Yue, Q.; Wang, W.; Gao, B. Improving the removal of chromium by polymer epichlorohydrin- dimethylamine functionalized mesoporous silica. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 169, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylinska, N. Single-stage separation and quantitation of anionic and cationic forms of transition metals from environmental water using organo-functionalized ordered mesoporous silica. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2025, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Ding, K.; You, Y.; Sheng, G.; Dong, H.; Liu, H. In-situ fabrication of exceptionally efficient traps namely nanoscale zero valent iron wrapped on mesoporous silica microspheres with different size in effectively purifying and scavenging Re(VII) and Cr(VI) from water matrices. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.; Yogeshwaran, V.; Rajendran, S.; Hoang, T.K.; Soto-Moscoso, M.; Ghfar, A.A.; Bathula, C. Investigation of mechanism of heavy metals (Cr6+, Pb2+& Zn2+) adsorption from aqueous medium using rice husk ash: Kinetic and thermodynamic approach. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Valtierra, M.; Salazar-Hernández, C.; Mendoza-Miranda, J.M.; Elorza-Rodríguez, E.; Puy-Alquiza, M.J.; Caudillo-González, M.; Salazar-Hernández, M.M. Cr(III) removal from tannery effluents using silica obtained from rice husk and modified silica. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 158, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, S.; Kausar, A.; Iqbal, M.; El Messaoudi, N.; Miyah, Y.; Knani, S.; Graba, B. Advances in extraction of silica from rice husk and its modification for friendly environmental wastewater treatment via adsorption technology. J. Water Process. Eng. 2025, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Khemis, I.; Aouaini, F.; Knani, S.; Al-Mugren, K.S.; Ben Lamine, A. Microscopic and macroscopic analysis of hexavalent chromium adsorption on polypyrrole-polyaniline@rice husk ash adsorbent using statistical physics modeling. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirhandeh, S.Z.H.; Salem, A.; Salem, S. Sono-chemical extraction of silica from rice husk for uptake of chromium species from tannery wastewater: Effect of aging time on porous structure. Mater. Lett. 2022, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Din, I.; Aziz, F.; Qureshi, I.U.; Zahid, M.; Mustafa, G.; Sher, A.; Hakim, S. Chromium adsorption from water using mesoporous magnetic iron oxide-aluminum silicate adsorbent: An investigation of adsorption isotherms and kinetics. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaye, G.; Kiflie, Z.; Mekonnen, T.H.; Jida, M. Amine-functionalized magnetic bio-nanocomposite for fluoride and chromium removal in water. Results Chem. 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; He, L.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Q. Removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution using low-cost magnetic microspheres derived from alkali-activated iron-rich copper slag. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, P.; Pan, Y.; Wang, G. Fabrication of hydrophilic defective MOF-801 thin-film nanocomposite membranes via interfacial polymerization for efficient chromium removal from water. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 384, 125561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, A.S.; Salih, S.S.; Kadhom, M.; Ghosh, T.K. Removal of heavy metals from contaminated water using Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): A review on techniques and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosroshahi, N.; Bakhtian, M.; Safarifard, V. Mechanochemical synthesis of ferrite/MOF nanocomposite: Efficient photocatalyst for the removal of meropenem and hexavalent chromium from water. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2022, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokalıoğlu, Ş.; Moghaddam, S.T.H.; Demir, S. A zirconium metal–organic framework functionalized with a S/N containing carboxylic acid (MOF-808(Zr)-Tz) as an efficient sorbent for the ultrafast and selective dispersive solid phase micro extraction of chromium, silver, and rhodium in water samples. Talanta 2024, 274, 126094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Amitani, N.; Yokoyama, T.; Ueda, A.; Kusakabe, M.; Unami, S.; Odashima, Y. Synthesis of mesoporous silica from geothermal water. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J.H.; Chun, J. Facile approach for the synthesis of spherical mesoporous silica nanoparticles from sodium silicate. Mater. Lett. 2021, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, K.-Z.; Sayari, A. Synthesis of onion-like mesoporous silica from sodium silicate in the presence of α,ω-diamine surfactant. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 114, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewlad-Ahmed, A.M.; Morris, M.; Holmes, J.; Belton, D.J.; Patwardhan, S.V.; Gibson, L.T. Green Nanosilicas for Monoaromatic Hydrocarbons Removal from Air. Silicon 2021, 14, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Hernández, M.; Salazar-Hernández, C.; Rodríguez, E.E.; Mendoza-Miranda, J.M.; Puy-Alquiza, M.d.J.; Miranda-Aviles, R.; Rodríguez, C.R. Using of Green Silica Amine-Fe3O4 Modified from Rrecovery Ag(I) on Aqueous System. Silicon 2023, 16, 1509–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, T.J.; Bull, L.M.; Klemperer, W.G.; Loy, D.A.; McEnaney, B.; Misono, M.; Monson, P.A.; Pez, G.; Scherer, G.W.; Vartuli, J.C.; et al. Tailored Porous Materials. Chem. Mater. 1999, 11, 2633–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, J.O.; Ajanaku, K.O.; Adekoya, J.A.; Banerjee, R.; Patra, C.R.; Pavuluri, S.; Sreedhar, B. Physicochemical and textural properties of amino-functionalised mesoporous silica nanomaterials from different silica sources. Results Chem. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Lan, R.; He, L.; Liu, H.; Pei, X. A critical review of adsorption isotherm models for aqueous contaminants: Curve characteristics, site energy distribution and common controversies. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 329, 117104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Da'ana, D.A. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of adsorption isotherm models: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 393, 122383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafnan, S.; Awotunde, A.; Glatz, G.; Adjei, S.; Alrumaih, I.; Gowida, A. Langmuir adsorption isotherm in unconventional resources: Applicability and limitations. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.; Hameed, B. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, T.; Saleem, A.; Wang, C. Enhanced removal of Cr(III)-EDTA chelates from high-salinity water by ternary complex formation on DETA functionalized magnetic carbon-based adsorbents. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonin, J.P. On the comparison of pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws in the modeling of adsorption kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 300, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.-C.; Tseng, R.-L.; Huang, S.-C.; Juang, R.-S. Characteristics of pseudo-second-order kinetic model for liquid-phase adsorption: A mini-review. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 151, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largitte, L.; Pasquier, R. A review of the kinetics adsorption models and their application to the adsorption of lead by an activated carbon. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2016, 109, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| [Si(OH)4]; (mgL–1) | ABET [m2g–1] | Average Pore Volume [cm3g–1] | Pore Diameter (BJH) [nm] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMS-0h | 626.1 | 444.5 | 0.341 | 3.9; broad between 5-20 |

| GMS-6h | 265.9 | 491.4 | 0.416 | 3.9 |

| GMS-24h | 97.7 | 496.5 | 0.552 | 3.9 |

| GMS-48 h | 52.9 | 466 | 0.497 | 3.9 and 7.8 |

| SiO2-HCl* | – | 13.27 | 0.052 | – |

| MS-TEOS [39] | – | 543-908 | 0.63-0.67 | 6-7 |

| ABET [m2g–1] | Average Pore Volume [cm3g–1] | Pore Diameter (BJH) [nm] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMS-24 h | 496.5 | 0.552 | 3.9 |

| GMS-24h-NH2 | 171.1(-65.5%) | 0.368 (-33.3%) | 3.2 (-17.9%) |

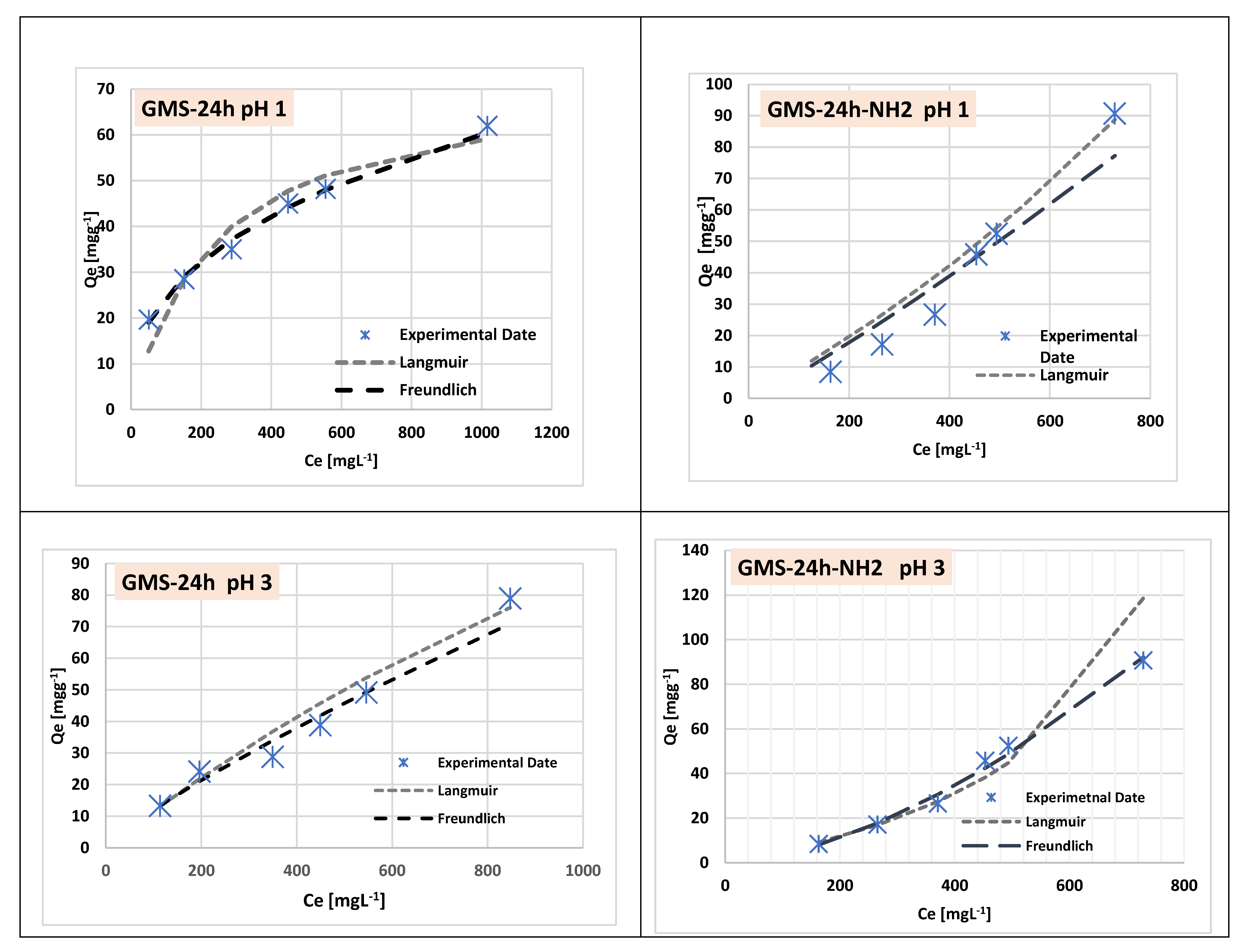

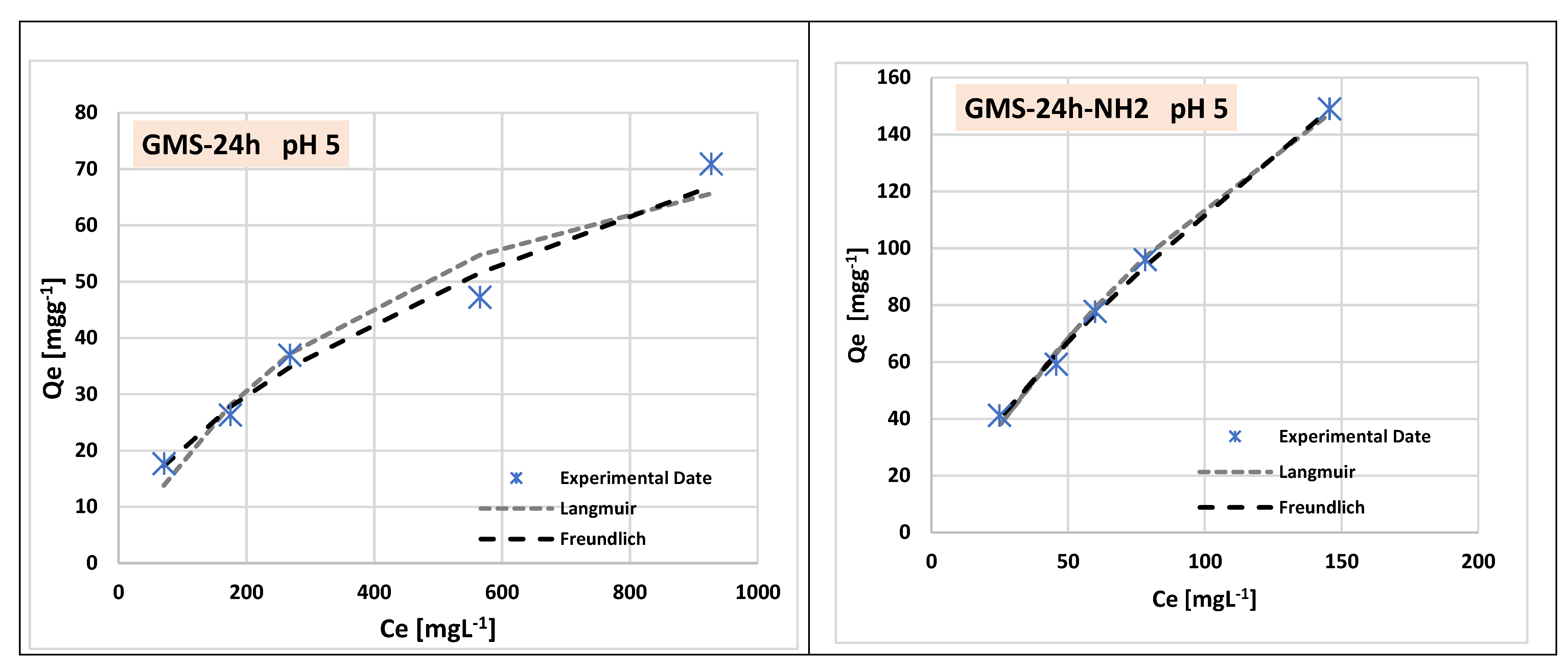

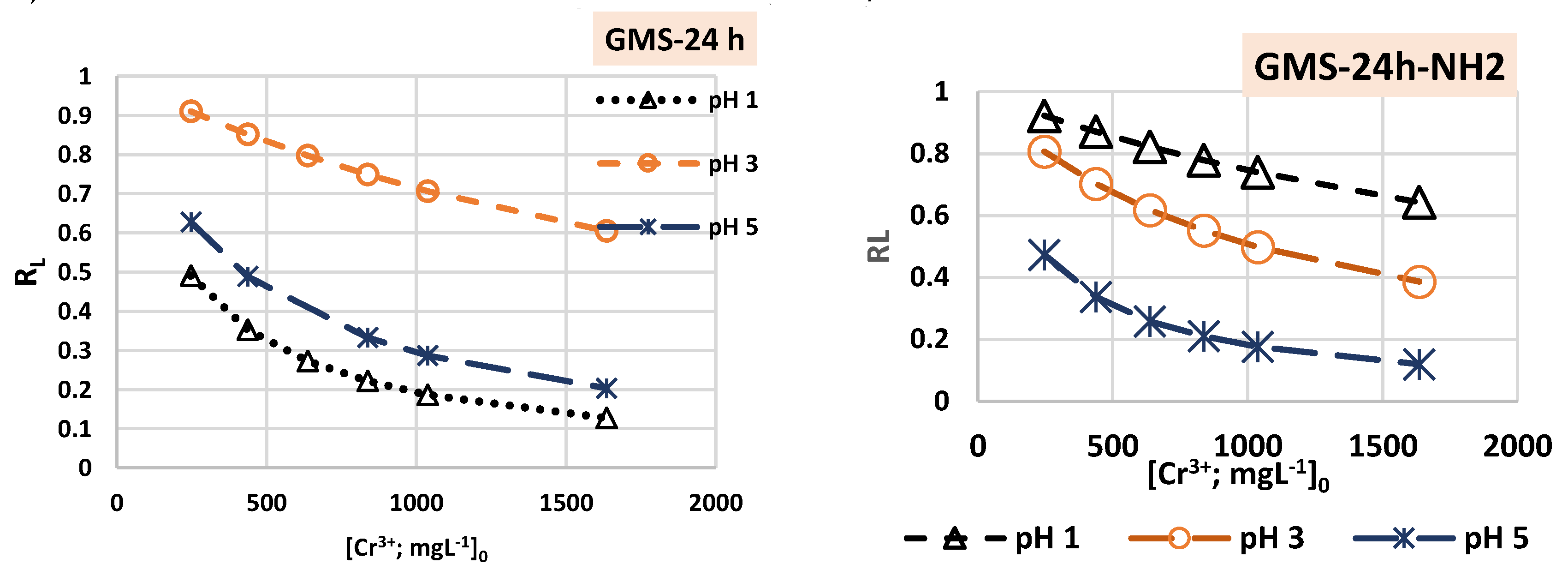

| Parameters | pH 1 | pH 3 | pH 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMS-24h | GMS-24h-NH2 | GMS-24h | GMS-24h-NH2 | GMS-24h | GMS-24h-NH2 | ||

| Langmuir | Q0 [mgg–1] | 72.99 | 263.16 | 303.03 | 48.31 | 95.24 | 370.37 |

| KL [L mg–1] | 0.0042 | 0.00034 | 0.00039 | 0.00097 | 0.0024 | 0.0045 | |

| R2 | 0.9632 | 0.9568 | 0.8783 | 0.8675 | 0.9099 | 0.9052 | |

| Δq(%) | 0.1389 | 0.1832 | 0.313 | 0.1967 | 0.00012 | 0.09134 | |

| G [KJmol–1] | 3.59 | 9.79 | 9.46 | 7.23 | 5.04 | 3.42 | |

| Freundlich | KF [(mg/g)/(mg/L)]1/n | 4.21 | 0.042 | 3.843 | 0.00197 | 1.823 | 3.653 |

| 1/n | 0.385 | 1.14 | 0.832 | 1.63 | 0.527 | 0.744 | |

| R2 | 0.9929 | 0.956 | 0.9666 | 0.9907 | 0.9842 | 0.9945 | |

| Δq(%) | 0.0718 | 0.3552 | 0.2199 | 0.1068 | 0.1269 | 0.0561 | |

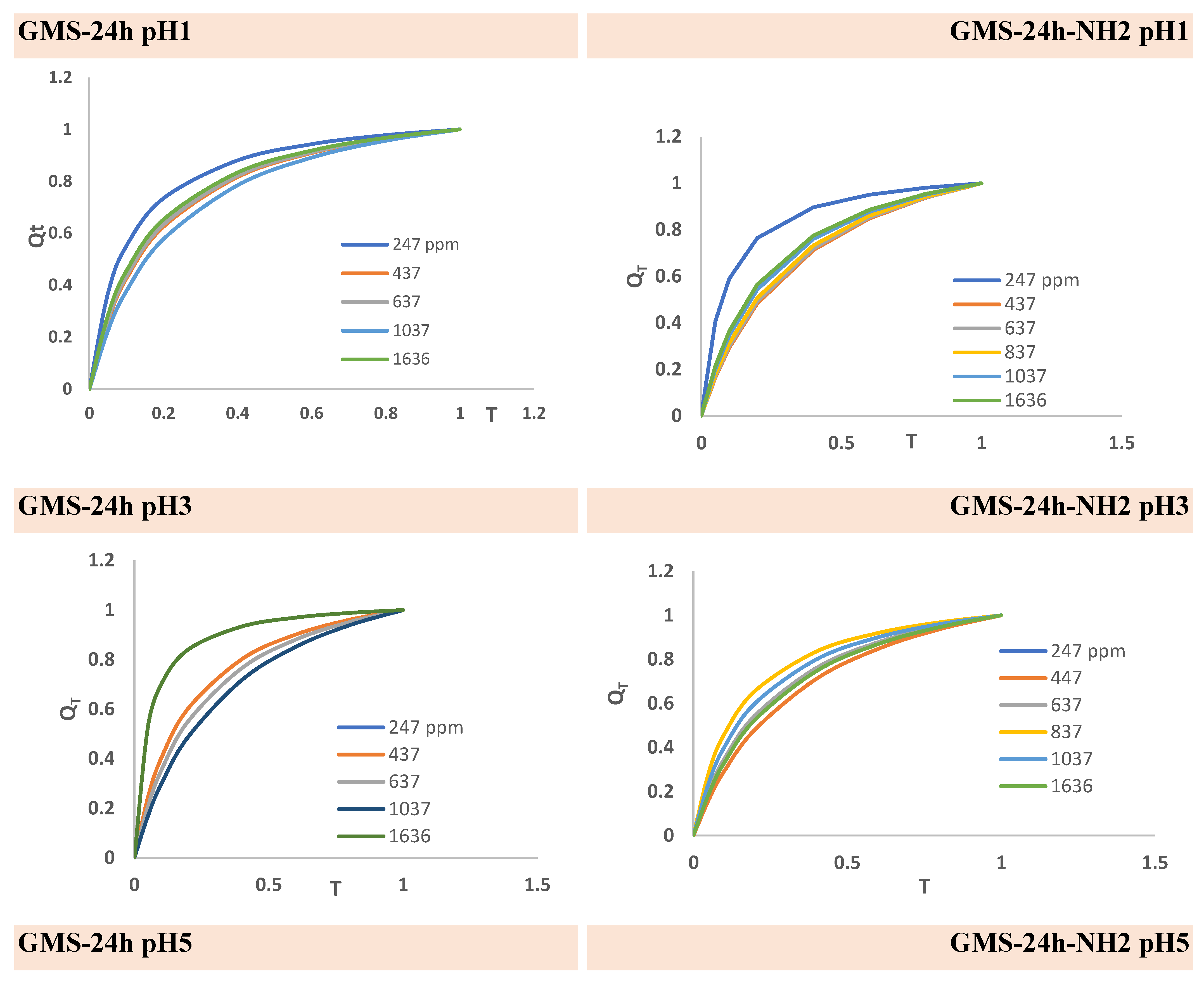

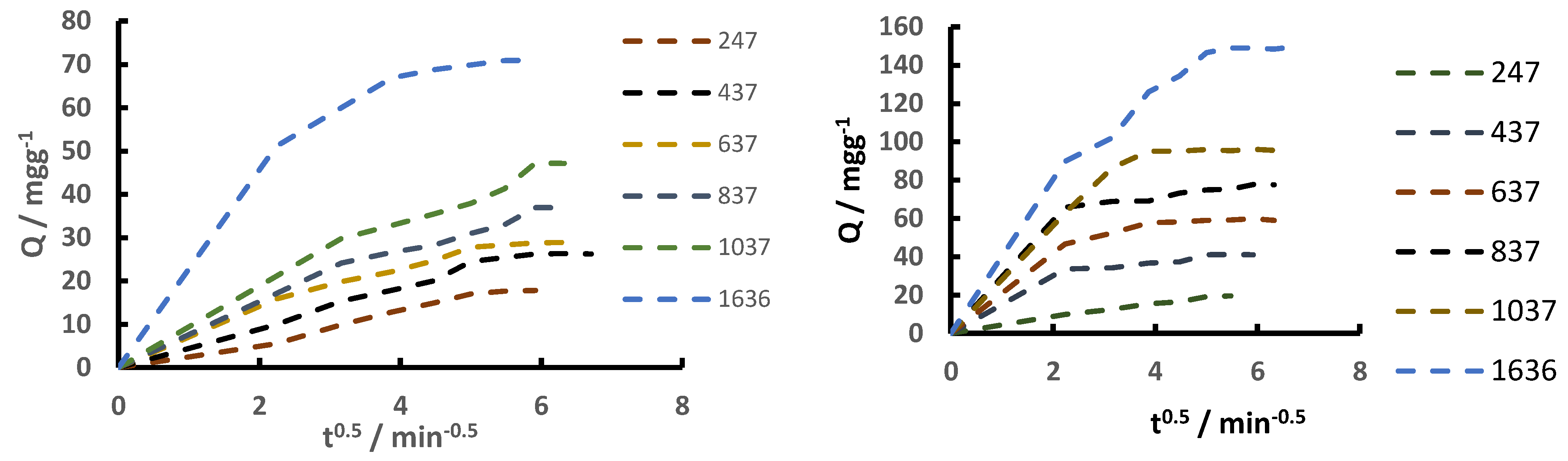

| GMS-24h | GMS-24hNH2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | [Ag(I)]0 mgL-1 |

247 | 437 | 637 | 837 | 1037 | 1636 | 247 | 437 | 637 | 837 | 1037 | 1636 |

| 1 | Qeexp [mgg-1] |

19.66 | 28.5 | 35 | 38.9 | 48.2 | 62 | 12.1 | 28.5 | 30.3 | 42.5 | 50.2 | 90.61 |

| Qecal [mgg-1] |

19.62 | 21.18 | 37.6 | 50.36 | 41.54 | 52.47 | 14.6 | 21.18 | 30.65 | 55.61 | 40.67 | 96.64 | |

| K1 [min-1] |

0.148 | 0.068 | 0.0792 | 0.0817 | 0.0568 | 0.0242 | 0.044 | 0.1124 | 0.0845 | 0.0741 | 0.0691 | 0.1022 | |

| R2 | 0.9128 | 0.9355 | 0.9411 | 0.9599 | 0.9838 | 0.9922 | 0.9575 | 0.9035 | 0.9574 | 0.9057 | 0.9662 | 0.9181 | |

| Δq(%) |

9.5 | 37.98 | 31.81 | 49.87 | 26.78 | 21.29 | 21.66 | 50.38 | 6.4 | 27.07 | 31.27 | 15.35 | |

| 3 | Qeexp [mgg-1] |

13.3 | 24.1 | 28.8 | - | 49 | 78.9 | 8.4 | 17.12 | 26.6 | 38.34 | 54.3 | 90.68 |

| Qecal [mgg-1] |

9.17 | 23.82 | 60.98 | - | 49 | 155.63 | 10.52 | 16.27 | 18.78 | 49.27 | 46.27 | 78.72 | |

| K1 [min-1] |

0.0649 | 0.0762 | 0.1789 | - | 0.0831 | 0.1697 | 0.1273 | 0.0776 | 0.1291 | 0.1276 | 0.09372 | 0.0739 | |

| R2 | 0.9054 | 0.9913 | 0.8781 | - | 0.997 | 0.8984 | 0.8601 | 0.9564 | 0.9734 | 0.8884 | 0.9819 | 0.9422 | |

| Δq(%) |

41.35 | 0.3186 | 26.44 | - | 4.47 | 263.93 | 24.20 | 14.92 | 20.28 | 29.62 | 23.26 | 25.13 | |

| 5 | Qeexp [mgg-1] |

17.6 | 26.3 | 28.7 | 36.2 | 47.2 | 70.89 | 19.56 | 41.2 | 59.12 | 77.7 | 95.87 | 149.03 |

| Qecal [mgg-1] |

22.87 | 28.56 | 24.38 | 35.93 | 40.63 | 56.76 | 16.87 | 38.01 | 30.70 | 35.94 | 60.67 | 184.84 | |

| K1 [min-1] |

0.1236 | 0.095 | 0.0907 | 0.0025 | 0.0637 | 0.1686 | 0.0654 | 0.1768 | 0.1596 | 0.1002 | 0.135 | 0.1607 | |

| R2 | 0.9245 | 0.9155 | 0.9649 | 0.818 | 0.9641 | 0.9898 | 0.9905 | 0.7857 | 0.9513 | 0.8532 | 0.945 | 0.9471 | |

| Δq(%) | 49.085 | 49.06 | 190 | 92.12 | 6.47 | 3.21 | 5.35 | 13.24 | 11.44 | 14.4 | 18.91 | 29.85 | |

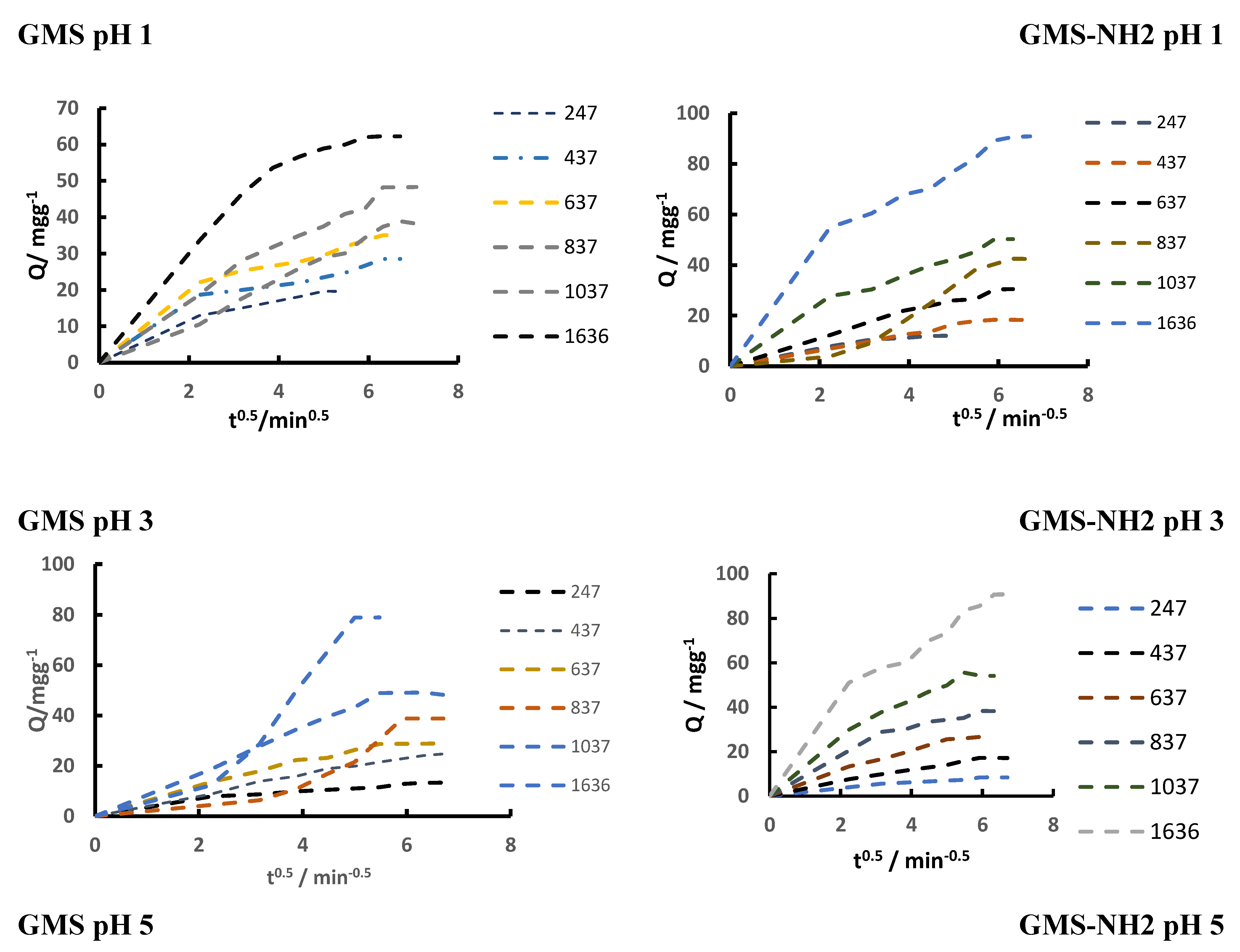

| GMS-24h | GMS-24hNH2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | [Ag(I)]0 mgL-1 |

247 | 437 | 637 | 837 | 1037 | 1636 | 247 | 437 | 637 | 837 | 1037 | 1636 |

| 1 | Qeexp [mgg-1] |

19.66 | 28.5 | 35 | 38.9 | 48.2 | 62 | 12.1 | 18.4 | 30.3 | 42.5 | 50.2 | 90.61 |

| Qecal [mgg-1] |

20.57 | 29.3 | 36.5 | 46.29 | 45.66 | 66.22 | 12.73 | 20.7 | 33.67 | 27.32 | 53.7 | 97 | |

| K2 [gmg-1min-1] |

0.024 | 0.0096 | 0.008 | 0.0018 | 0.0048 | 0.0049 | 0.049 | 0.0074 | 0.0047 | 0.0036 | 0.0037 | 0.0023 | |

| K2qe [min-1] | 0.494 | 0.281 | 0.292 | 0.0833 | 0.219 | 0.324 | 0.624 | 0.153 | 0.158 | 0.098 | 0.198 | 0.223 | |

| R2 | 0.9872 | 0.9773 | 0.9834 | 0.9135 | 0.9646 | 0.9926 | 0.9949 | 0.9375 | 0.9537 | 0.735 | 0.9631 | 0.977 | |

| Δq(%) | 8.9 | 7.7 | 6.4 | 13.7 | 14.3 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 12.5 | 10.2 | 54 | 9.1 | 8.1 | |

| Rw | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.145 | 0.377 | 0.182 | 0.133 | 0.077 | 0.268 | 0.256 | 0.243 | 0.21 | 0.193 | |

| Zone | II | I | I | I | I | I | II | I | I | I | I | I | |

| 3 | Qeexp [mgg-1] |

13.3 | 24.1 | 28.8 | - | 49 | 78.9 | 8.4 | 17.12 | 26.6 | 38.3 | 54.3 | 90.7 |

| Qecal [mgg-1] |

14.1 | 27.7 | 31.9 | - | 55.9 | 78.7 | 8.8 | 19.3 | 29.6 | 40.1 | 59.2 | 98.0 | |

| K2 [gmg-1min-1] |

0.0179 | 0.0045 | 0.0061 | - | 0.0026 | 0.0127 | 0.0396 | 0.0079 | 0.0071 | 0.0086 | 0.0046 | 0.0019 | |

| K2qe [min-1] | 0.252 | 0.125 | 0.194 | 0.145 | 0.999 | 0.348 | 0.152 | 0.210 | 0.345 | 0.272 | 0.186 | ||

| R2 | 0.9814 | 0.9481 | 0.9755 | - | 0.9576 | 1 | 0.982 | 0.962 | 0.9796 | 0.9889 | 0.9801 | 0.9663 | |

| Δq(%) | 0.384 | 10.66 | 9.52 | - | 8.5 | 0.51 | 8.75 | 10.28 | 10.39 | 5.64 | 9.97 | 9.86 | |

| Rw | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.204 | - | 0.262 | 0.0475 | 0.131 | 0.269 | 0.209 | 0.131 | 0.1667 | 0.226 | |

| Zone | I | I | I | - | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| 5 | Qeexp [mgg-1] |

17.6 | 26.3 | 28.7 | 36.2 | 47.2 | 70.89 | 19.56 | 41.2 | 59.12 | 77.7 | 95.87 | 149.03 |

| Qecal [mgg-1] |

19.76 | 30.3 | 31.15 | 39.06 | 50 | 72.88 | 21.01 | 42.19 | 60.6 | 78.74 | 99 | 158.7 | |

| K2 [gmg-1min-1] |

0.0097 | 0.0047 | 0.0321 | 0.0256 | 0.0038 | 0.0012 | 0.0118 | 0.0173 | 0.0186 | 0.0117 | 0.0087 | 0.0021 | |

| K2qe [min-1] | 0.192 | 0.142 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.19 | 0.087 | 0.248 | 0.729 | 1.127 | 0.921 | 0.861 | 0.333 | |

| R2 | 0.9292 | 0.9595 | 0.9797 | 0.9574 | 0.9451 | 0.9975 | 0.9722 | 0.9943 | 0.9987 | 0.9978 | 0.9966 | 0.9904 | |

| Δq(%) | 12.7 | 28.5 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 8.6 | 29.7 | 10.2 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 2.7 | 10.2 | 8.0 | |

| Rw | 0.2068 | 0.2558 | 0.0514 | 0.047 | 0.208 | 0.345 | 0.168 | 0.064 | 0.042 | 0.0515 | 0.0548 | 0.1304 | |

| Zone | I | I | II | II | I | I | I | II | II | II | II | I | |

| Rw | Zone | Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Rw=1 | 0 | Type of Kinetic curve: line. System not approaching equilibrium |

| 1>Rw>0.1 | I | Type of Kinetic curve: slightly curved. System approaching equilibrium |

| 0.1>Rw>0.01 | II | Type of Kinetic curve: largely curved System well approaching equilibrium |

| Rw<0.01 | III | Type of Kinetic curve: Pseudo-rectangular curved System drastically approaching equilibrium |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).