Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and Reagent

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Spheroid Culture and Growth for Initial Assessment of AHCC

2.4. Purification Characterization and Modification of EVs

2.5. Sphere Culture and Administration of Modified EVs

2.6. In-Vitro Assessment of the Immunostimulatory Effect of AHCC on Breast Cancer Cell Lines

2.7. Quantitative RT-PCR for MicroRNA Profiling

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

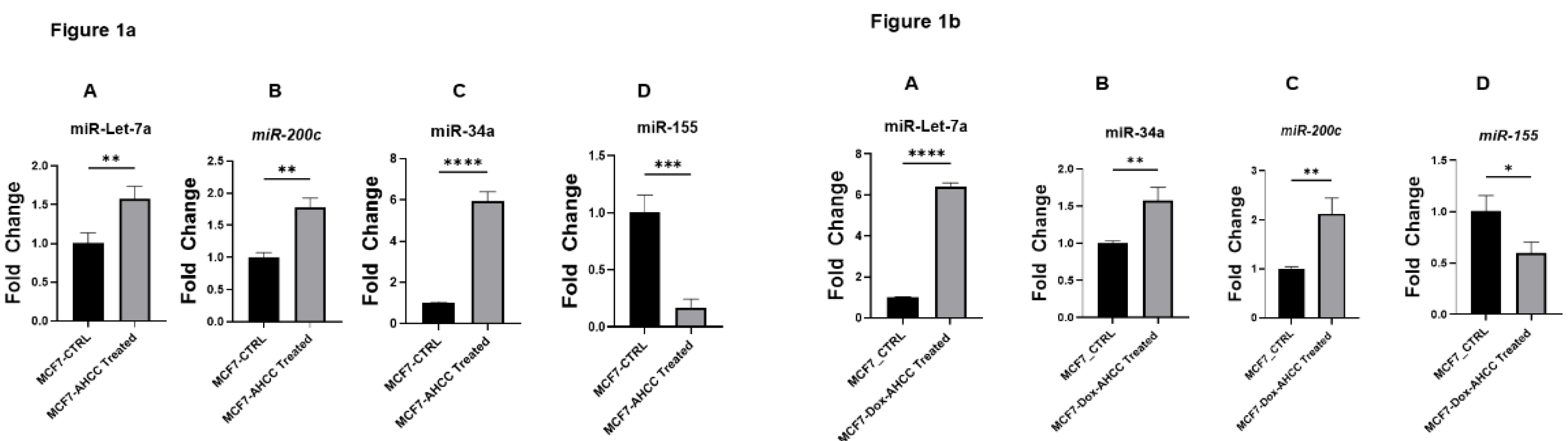

3.1. Regulatory Effects of AHCC on Tumor Suppressor miRNA and Oncogenic miRNA Expression in Breast Cancer Cell Lines

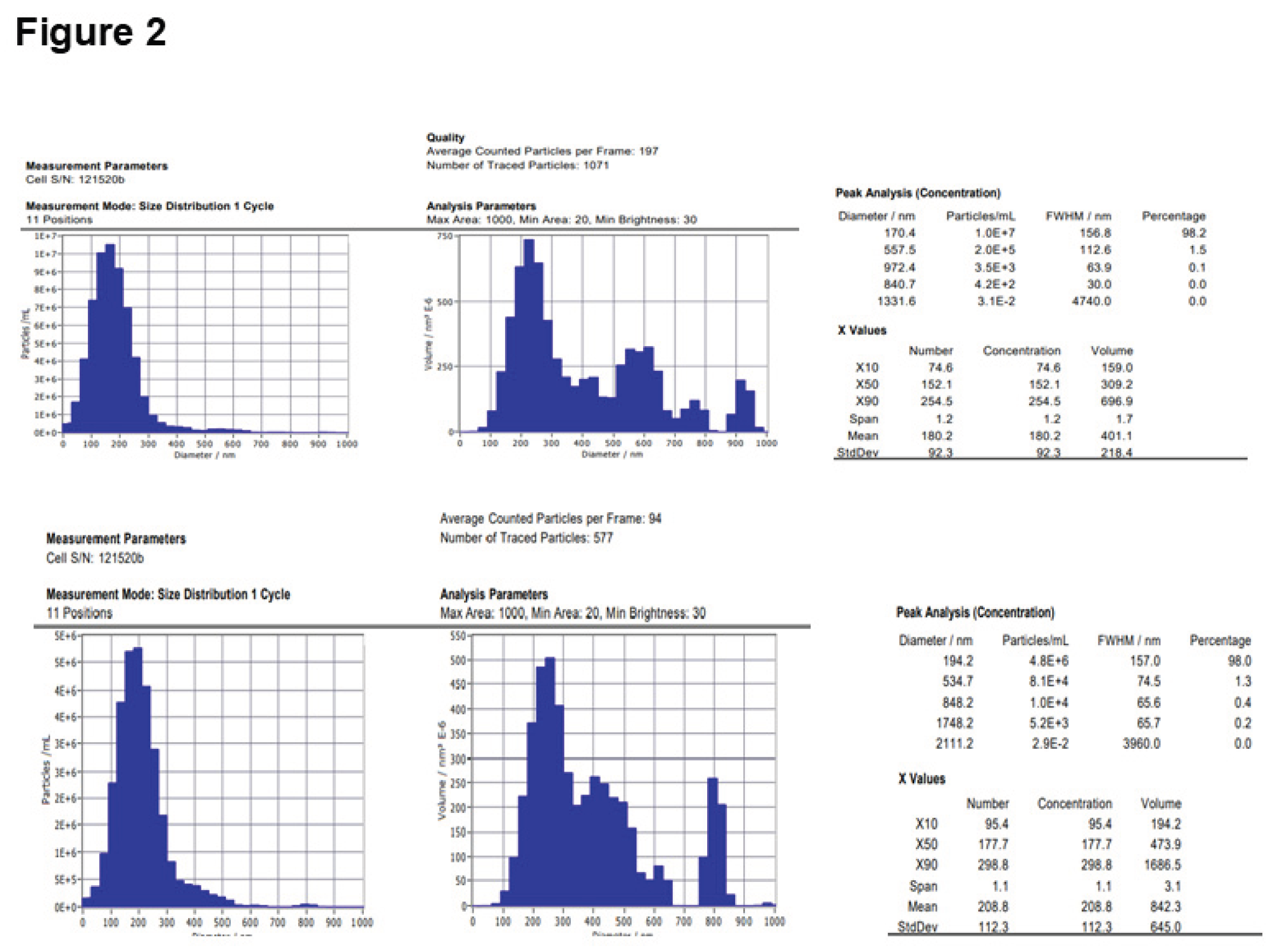

3.2. Purification and Characterization of EVs

3.3. Inhibitory Effects of AHCC-Treated MSC-Derived EVs on Colony Formation and Sphere Growth in MCF7 and MCF7-Dox Cells

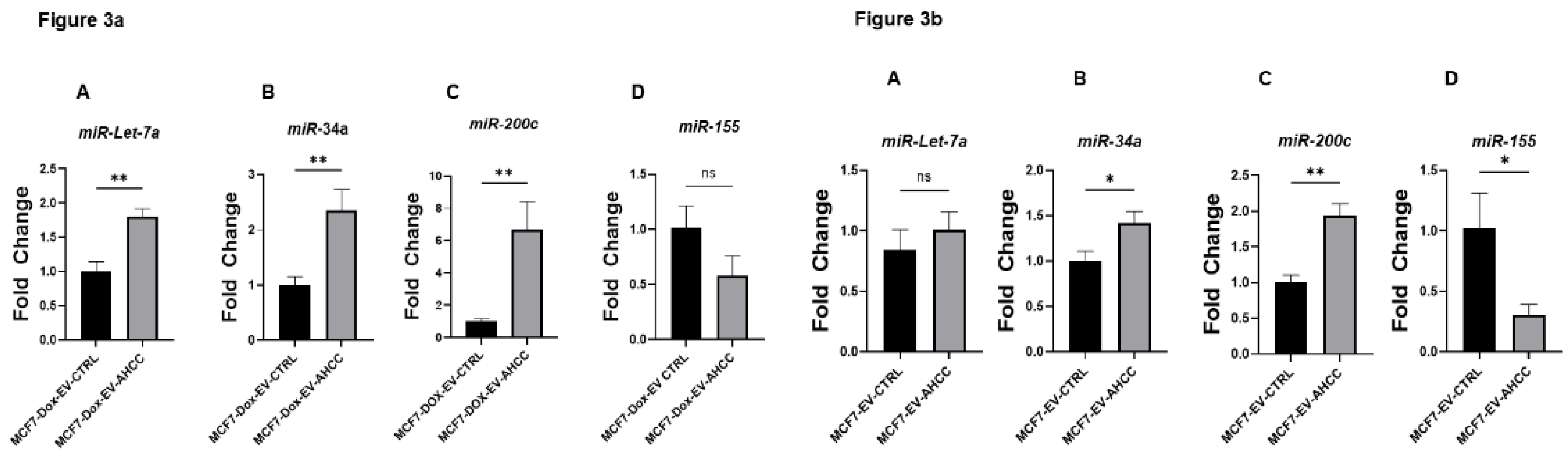

3.3. Modified EVs Delivered Their Cargo and Changed the Expression Level of Target miRNAs

4. Discussion

5. Future Investigation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EVs | Extracellular vehicles |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells |

| BCSCs | Breast cancer stem cells |

| FAMPS | Food-associated molecular patterns |

References

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- society, A.c. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024 2024 [cited 2024 2024-10-12]; Available from: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/2024-cancer-facts-figures.html.

- in, C.C.S.A.C. , et al. Canadian statistic 2023 [cited 2024-02-17; Available from: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2023-statistics/2023_pdf_en.pdf?rev=7e0c86ef787d425081008ed22377754d&hash=DBD6818195657364D831AF0641C4B45C&_gl=1*1scrz89*_gcl_au*NDE0NDE3MTI1LjE3MDc3OTc3NTU.

- Agarwal, G. and P. J.B.c. Ramakant, Breast cancer care in India: the current scenario and the challenges for the future. 2008, 3, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.J.; Ow, S.G.W.; Sim, Y.; Liu, J.; Lim, S.H.; Tan, E.Y.; Tan, S.-M.; Lee, S.C.; Tan, V.K.-M.; Yap, Y.-S.; et al. Impact of deviation from guideline recommended treatment on breast cancer survival in Asia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, T.; Yuan, Y.; Li, H.; Shi, W.; Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, W. Tumor microenvironment of cancer stem cells: Perspectives on cancer stem cell targeting. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 101043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakarala, M. and M. S.J.J.o.c.o.o.j.o.t.A.S.o.C.O. Wicha, Implications of the cancer stem-cell hypothesis for breast cancer prevention and therapy. 2008, 26, 2813. [Google Scholar]

- Gooding, A.J.; Schiemann, W.P. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Programs and Cancer Stem Cell Phenotypes: Mediators of Breast Cancer Therapy Resistance. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 18, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifzad, F.; Ghavami, S.; Verdi, J.; Mardpour, S.; Sisakht, M.M.; Azizi, Z.; Taghikhani, A.; Łos, M.J.; Fakharian, E.; Ebrahimi, M.; et al. Glioblastoma cancer stem cell biology: Potential theranostic targets. Drug Resist. Updat. 2019, 42, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, H.G.; Seywald, M.; Wöckel, A.; Muco, B.; Tanriverdi, M.; Stepien, J. Psychological distress in breast cancer patients during oncological inpatient rehabilitation: incidence, triggering factors and correlation with treatment-induced side effects. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 307, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telang, N.T. Natural products as drug candidates for breast cancer (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2023, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.-L.; Gong, Y.; Qi, Y.-J.; Shao, Z.-M.; Jiang, Y.-Z. Effects of dietary intervention on human diseases: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, E. and A. J.T.J.o.n. DeMichele, Nutritional approaches to late toxicities of adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer survivors. 2003, 133, 3785S–3793S. [Google Scholar]

- Jayedi, A.; Emadi, A.; Khan, T.A.; Abdolshahi, A.; Shab-Bidar, S. Dietary Fiber and Survival in Women with Breast Cancer: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 73, 1570–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Kitagawa, T.; Baron, B.; Kuhara, K.; Nagayasu, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Chiba, I.; Kuramitsu, Y. A standardized extract of cultured Lentinula edodes mycelia downregulates cortactin in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqi, A.A.; Rakhmetova, V.; Kapanova, G.; Mussakhanova, A.; Tashenova, G.; Tulebayeva, A.; Akhenbekova, A.; Xu, B. Suppressive effects of bioactive herbal polysaccharides against different cancers: From mechanisms to translational advancements. Phytomedicine 2022, 110, 154624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, L.; Gaikwad, A.; Gonzalez, A.; Nugent, E.K.; Smith, J.A. Evaluation of Active Hexose Correlated Compound (AHCC) in Combination With Anticancer Hormones in Orthotopic Breast Cancer Models. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganelli, F.; Chiarini, F.; Palmieri, A.; Martinelli, M.; Sena, P.; Bertacchini, J.; Roncucci, L.; Cappellini, A.; Martelli, A.M.; Bonucci, M.; et al. The Combination of AHCC and ETAS Decreases Migration of Colorectal Cancer Cells, and Reduces the Expression of LGR5 and Notch1 Genes in Cancer Stem Cells: A Novel Potential Approach for Integrative Medicine. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, É.A.; Mallet, J.-F.; Jambi, M.; Nishioka, H.; Homma, K.; Matar, C. MicroRNA signature in the chemoprevention of functionally-enriched stem and progenitor pools (FESPP) by Active Hexose Correlated Compound (AHCC). Cancer Biol. Ther. 2017, 18, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, N.L.; Shin, Y.; Yang, G.; Furmanski, P.; Suh, N. Breast cancer stem cells: A review of their characteristics and the agents that affect them. Mol. Carcinog. 2021, 60, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, B.W.; Nogusa, S.; A Ackerman, E.; Gardner, E.M. Supplementation with Active Hexose Correlated Compound Increases the Innate Immune Response of Young Mice to Primary Influenza Infection. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2868–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Sun, B.; Fujii, H.; Kosuna, K.-I.; Yin, Z. Active hexose correlated compound enhances tumor surveillance through regulating both innate and adaptive immune responses. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2005, 55, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, M.S.; Park, H.-J.; Maeda, T.; Nishioka, H.; Fujii, H.; Kang, I. The Effects of AHCC®, a Standardized Extract of Cultured Lentinura edodes Mycelia, on Natural Killer and T Cells in Health and Disease: Reviews on Human and Animal Studies. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Fujii, H.; Walshe, T. Effects of active hexose correlated compound on frequency of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells producing interferon-γ and/or tumor necrosis factor–α in healthy adults. Hum. Immunol. 2010, 71, 1187–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.H. , et al., Modulation of T regulatory and dendritic cell phenotypes following ingestion of Bifidobacterium longum, active hexose correlated compound (AHCC®) and azithromycin in healthy individuals. 11(10).

- OYEDEPO, T.A. E.J.H.P.D.F. MORAKINYO, and Applications, Medicinal Mushrooms. 2020: p. 167.

- Matsui, K.; Ozaki, T.; Oishi, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Kaibori, M.; Nishizawa, M.; Okumura, T.; Kwon, A.-H. Active Hexose Correlated Compound Inhibits the Expression of Proinflammatory Biomarker iNOS in Hepatocytes. Eur. Surg. Res. 2011, 47, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Ohashi, S.; Ohtsuki, A.; Kiyono, T.; Park, E.Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Sato, K.; Oishi, M.; Miki, H.; Tokuhara, K.; et al. Adenosine, a hepato-protective component in active hexose correlated compound: Its identification and iNOS suppression mechanism. Nitric Oxide 2014, 40, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terakawa, N.; Matsui, Y.; Satoi, S.; Yanagimoto, H.; Takahashi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamao, J.; Takai, S.; Kwon, A.-H.; Kamiyama, Y. Immunological Effect of Active Hexose Correlated Compound (AHCC) in Healthy Volunteers: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutr. Cancer 2008, 60, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spierings, E. , et al. , A phase 1 study of the safety of the nutritional supplement, active hexose correlated compound, AHCC, in healthy volunteers. 2008, 13, 81–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cowawintaweewat, S.; Manoromana, S.; Sriplung, H.; Khuhaprema, T.; Tongtawe, P.; Tapchaisri, P.; Chaicumpa, W. Prognostic improvement of patients with advanced liver cancer after active hexose correlated compound (AHCC) treatment. Journal of Immunotherapy 2006, 24, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Parida, D.K.; Wakame, K.; Nomura, T. Integrating Complimentary and Alternative Medicine in Form of Active Hexose Co-Related Compound (AHCC) in the Management of Head & Neck Cancer Patients. Int. J. Clin. Med. 2011, 02, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J.-F.; Graham, É.; Ritz, B.W.; Homma, K.; Matar, C. Active Hexose Correlated Compound (AHCC) promotes an intestinal immune response in BALB/c mice and in primary intestinal epithelial cell culture involving toll-like receptors TLR-2 and TLR-4. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 55, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, T. D.J.N. Kulkarni, Immunity,, and Infection, 25 AHCC Nutritional Supplement. 2017: p. 427.

- Olamigoke, L.T. , Multifactorial Effects of Biological Response Modifiers and Anti-Neoplastic Induced Immune Cell Activation and Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cell Inhibition. 2017, Texas Southern University.

- Dhawan, A.; Scott, J.G.; Harris, A.L.; Buffa, F.M. Pan-cancer characterisation of microRNA across cancer hallmarks reveals microRNA-mediated downregulation of tumour suppressors. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A. , Breast cancer invasion by microRNAs aid. Authorea Preprints 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ocansey, D.K.W.; Pei, B.; Yan, Y.; Qian, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Mao, F. Improved therapeutics of modified mesenchymal stem cells: an update. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, Y.; Ah-Pine, F.; Khettab, M.; Arcambal, A.; Begue, M.; Dutheil, F.; Gasque, P. The Dual Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cancer Pathophysiology: Pro-Tumorigenic Effects versus Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q. Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Potential Therapeutics as MSC Trophic Mediators in Regenerative Medicine. Anat. Rec. 2019, 303, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiapalis, D. and L.J. C. O’Driscoll, Mesenchymal stem cell derived extracellular vesicles for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Cells 2020, 9, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardpour, S.; Hamidieh, A.A.; Taleahmad, S.; Sharifzad, F.; Taghikhani, A.; Baharvand, H. Interaction between mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles and immune cells by distinct protein content. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 8249–8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaschke, N.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Göbel, A.; Rachner, T.D. Evolving functions of Dickkopf-1 in cancer and immunity. Cancer Lett. 2020, 482, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Song, J.; Chen, W.; Yuan, D.; Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Su, H.; Zhu, J. Expression and Role of Dickkopf-1 (Dkk1) in Tumors: From the Cells to the Patients. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ashton, R.; Hensel, J.A.; Lee, J.H.; Khattar, V.; Wang, Y.; Deshane, J.S.; Ponnazhagan, S. RANKL-Targeted Combination Therapy with Osteoprotegerin Variant Devoid of TRAIL Binding Exerts Biphasic Effects on Skeletal Remodeling and Antitumor Immunity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 2585–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Xu, Z.-L.; Zhao, T.-J.; Ye, L.-H.; Zhang, X.-D. Dkk-1 secreted by mesenchymal stem cells inhibits growth of breast cancer cells via depression of Wnt signalling. Cancer Lett. 2008, 269, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, K.; Das, S.; Houser, S.D.; Quadri, S.K.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, J. Concentration-dependent inhibition of angiogenesis by mesenchymal stem cells. Blood 2009, 113, 4197–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Farhadihosseinabadi, B.; Zali, H.; Niknejad, H. Human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells to promote/suppress cancer: two sides of the same coin. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindhan, S.; Ejam, S.S.; Lafta, M.H.; Markov, A.; Yumashev, A.V.; Ahmadi, M. Mesenchymal stem cells and cancer therapy: insights into targeting the tumour vasculature. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.L.N.; Breakefield, X.O.; Weaver, A.M. Extracellular Vesicles: Unique Intercellular Delivery Vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Natalia, A.; Lim, C.Z.J.; Ho, N.R.Y.; Chowbay, B.; Loh, T.P.; Tam, J.K.C.; Shao, H. Extracellular vesicle drug occupancy enables real-time monitoring of targeted cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescitelli, R.; LäsSer, C.; LötVall, J. Isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicle subpopulations from tissues. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 1548–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghikhani, A.; Farzaneh, F.; Sharifzad, F.; Mardpour, S.; Ebrahimi, M.; Hassan, Z.M. Engineered Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Potentials in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardpour, S. , et al., Hydrogel-Mediated Sustained Systemic Delivery of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Improves Hepatic Regeneration in Chronic Liver Failure. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2019, 11, 37421–37433. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Xiong, D. Mesenchymal stromal cells as vehicles of tetravalent bispecific Tandab (CD3/CD19) for the treatment of B cell lymphoma combined with IDO pathway inhibitor d-1-methyl-tryptophan. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhu, B.; Huang, G.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, C. Microvesicles derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote U2OS cell growth under hypoxia: the role of PI3K/AKT and HIF-1α. Hum. Cell 2018, 32, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, S.; Collino, F.; Deregibus, M.C.; Grange, C.; Tetta, C.; Camussi, G. Microvesicles Derived from Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Inhibit Tumor Growth. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ju, G.-Q.; Du, T.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Liu, G.-H. Microvesicles Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuate Bladder Tumor Cell Growth In Vitro and In Vivo. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahand, J.S.; Vandchali, N.R.; Darabi, H.; Doroudian, M.; Banafshe, H.R.; Moghoofei, M.; Babaei, F.; Salmaninejad, A.; Mirzaei, H. Exosomal MicroRNAs: Novel Players in Cervical Cancer. Epigenomics 2020, 12, 1651–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Chaleshtori, M.; Bandehpour, M.; Heidari, N.; Mohammadi-Yeganeh, S.; Hashemi, S.M. Exosome-mediated miR-33 transfer induces M1 polarization in mouse macrophages and exerts antitumor effect in 4T1 breast cancer cell line. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 90, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Wang, X.; Gong, Z.; Yu, M.; Wu, H.; Zhang, D. Exosome-mediated metabolic reprogramming: the emerging role in tumor microenvironment remodeling and its influence on cancer progression. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmatzadeh, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Jadidi-Niaragh, F.; Asghari, F.; Yousefi, M. The role of oncomirs in the pathogenesis and treatment of breast cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 78, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yuan, L.; Luo, J.; Gao, J.; Guo, J.; Xie, X. MiR-34a inhibits proliferation and migration of breast cancer through down-regulation of Bcl-2 and SIRT1. Clin. Exp. Med. 2012, 13, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Sharifi-Zarchi, A.; Firouzi, J.; Azizmi, M.; Zarghami, N.; Alizadeh, E.; Ebrahimi, M. An integrated analysis to predict micro-RNAs targeting both stemness and metastasis in breast cancer stem cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2442–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MicroRNA-200c Increases Radiosensitivity of Human Cancer Cells with Activated EGFR-associated Signaling. 2018, 서울대학교 대학원.

- Venturella, G.; Ferraro, V.; Cirlincione, F.; Gargano, M.L. Medicinal Mushrooms: Bioactive Compounds, Use, and Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.-N., G. Deng, and J.J. Mao, Practical Application of "About Herbs" Website: Herbs and Dietary Supplement Use in Oncology Settings. Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass.) 2019, 25, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedepo, T.A. and A.E. Morakinyo, Medicinal Mushrooms, in Herbal Product Development. 2020, Apple Academic Press. p. 167-203.

- Chakraborty, C.; Chin, K.-Y.; Das, S. miRNA-regulated cancer stem cells: understanding the property and the role of miRNA in carcinogenesis. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 13039–13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ochiya, T. miRNA signaling networks in cancer stem cells. Regen. Ther. 2021, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Prieto-Vila, M.; Kohama, I.; Ochiya, T. Development of miRNA-based therapeutic approaches for cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, H.-W.; Lu, M.-H.; He, X.-H.; Li, Y.; Gu, H.; Liu, M.-F.; Wang, E.-D. MicroRNA-155 Functions as an OncomiR in Breast Cancer by Targeting theSuppressor of Cytokine Signaling 1Gene. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 3119–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiske, S.; Suetani, R.J.; Neilsen, P.M.; Callen, D.F. The Oncogenic Role of miR-155 in Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2012, 21, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chai, N.; Jiang, Q.; Chang, Z.; Chai, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Hou, J.; Linghu, E. DNA methyltransferase mediates the hypermethylation of the microRNA 34a promoter and enhances the resistance of patient-derived pancreatic cancer cells to molecular targeting agents. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 160, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Chang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, X.; Mi, M. 3,6-Dihydroxyflavone regulates microRNA-34a through DNA methylation. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.; Wang, W. A Systemic Review on the Regulatory Roles of miR-34a in Gastrointestinal Cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 2855–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, P.; Climent, M.; Panebianco, F.; Tordonato, C.; Santoro, A.; Marzi, M.J.; Pelicci, P.G.; Ventura, A.; Nicassio, F. Dual role for miR-34a in the control of early progenitor proliferation and commitment in the mammary gland and in breast cancer. Oncogene 2018, 38, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Yang, M.; Jiang, R.; An, N.; Wang, X.; Liu, B. Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIR Regulates the Proliferation, Self-Renewal Capacity, Tumor Formation and Migration of the Cancer Stem-Like Cell (CSC) Subpopulation Enriched from Breast Cancer Cells. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0170860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Bastami, M.; Solali, S.; Alivand, M.R. Aberrant miRNA promoter methylation and EMT-involving miRNAs in breast cancer metastasis: Diagnosis and therapeutic implications. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 233, 3729–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L.-. .-G.; Shi, J.-.-C.; Shang, J.; Hao, J.-.-G.; Du, X. Effect of miR-34a on resistance to sunitinib in breast cancer by regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Sciences 2019, 23, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Cao, T.; Huang, H.; Lian, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J.; Xia, J. Arsenic trioxide inhibits cell growth and motility via up-regulation of let-7a in breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 2396–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Fan, J.J.; Dong, C.; Li, H.-T.; Ma, B.-L. Inhibition effect of exosomes-mediated Let-7a on the development and metastasis of triple negative breast cancer by down-regulating the expression of c-Myc. European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Sciences 2019, 23, 5301–5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhayaya, S.; Mandal, C.C. A Differential Role of miRNAs in Regulation of Breast Cancer Stem Cells, in Cancer Stem Cells: New Horizons in Cancer Therapies. 2020, Springer. p. 87-109.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).