1. Introduction

The growing human population and the consequent increase in nutritional demand are placing substantial pressure on food production systems, with these challenges closely intertwined with climate change [

1]. As natural resources are limited, increasing agricultural output relies primarily on achieving higher yields per unit of arable land or per animal. In livestock production, improving productivity is strongly influenced by genetic selection, reproduction management, feeding strategies, and overall health status, which are hallmarks of intensive farming systems [

2]. In highly concentrated production systems such as pig farming, there is rising attention to animal welfare [

3], biosecurity, food safety [

4], and the environmental impacts of production [

5].

Conventional pig production often relies on antibiotics to manage health issues and optimize growth. Antibiotic use across all growth phases improves weight gain, reduces morbidity and mortality, and offers economic benefits exceeding the cost of administration [

6,

7]. However, concerns have emerged regarding the widespread use of sub-therapeutic antibiotics, including antibiotic resistance [

8] and the presence of residues in food products [

9,

10]. These risks underscore the necessity for alternative strategies, including biostimulants and feed additives that support pig health and growth without antibiotics [

11]. Widely explored alternatives include probiotics, prebiotics, phytobiotics, enzymes, and acidifiers, which can also positively influence the rearing environment [

12,

13].

Among environmental challenges, the emission of harmful gases such as ammonia from intensive livestock operations poses threats to animal welfare and the environment [

14]. Nutritional strategies aimed at reducing ammonia emissions include lowering crude protein content with balanced amino acids [

15], supplementation with enzymes [

16,

17,

18], herbal products [

19], probiotics [

20,

21], and organic acids [

22,

23]. Organic acids, naturally occurring in animal, plant, and microbial sources, serve as energy substrates during gastrointestinal metabolism, lower gastric pH, stimulate digestive enzyme secretion, inhibit pathogens, and enhance nutrient digestibility, positioning them as promising antibiotic alternatives [

24,

25].

The efficacy of organic acids depends on multiple factors, including their chemical and physical properties, dosage, feed composition, animal age, and health status [

25,

26]. Salts of organic acids (e.g., sodium, calcium, potassium) are flavored in feed due to improved solubility, lower corrosivity, and ease of handling compared to free acids, while encapsulation technologies further optimize stability, bioavailability, and targeted delivery [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Commonly applied organic acids in pig and poultry nutrition include lactic, formic, acetic, propionic, fumaric, citric, and butyric acids, either individually, as mixtures, or in combination with other feed supplements [

24,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyric acid, have received considerable attention due to their multifaceted benefits on gut health, intestinal microbiota modulation, and host metabolism [

35,

38]. SCFAs are primarily produced via microbial fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates in the gut, with butyrate, acetate, and propionate comprising the majority [

39,

40]. Butyric acid, a volatile, pungent compound [

40,

41], can be supplemented in the form of its salts (e.g., sodium, calcium, magnesium butyrate), which facilitate handling, reduce odor and corrosivity, and maintain efficacy through the presence of the active butyrate ion [

32,

42,

43,

44,

45]. These properties make butyrates highly effective as feed additives to support intestinal health, growth performance, and overall pig productivity.

In summary, the transition from antibiotic use to alternative feed additives such as organic acids, particularly SCFAs, represents a critical strategy for sustainable pig production. These additives offer dual benefits by enhancing animal health and welfare while mitigating environmental impacts. The present work aims to explore the role of organic acids in pig nutrition, with a particular focus on their efficacy, mechanisms of action, and technological considerations to optimize their application in intensive pig farming systems.

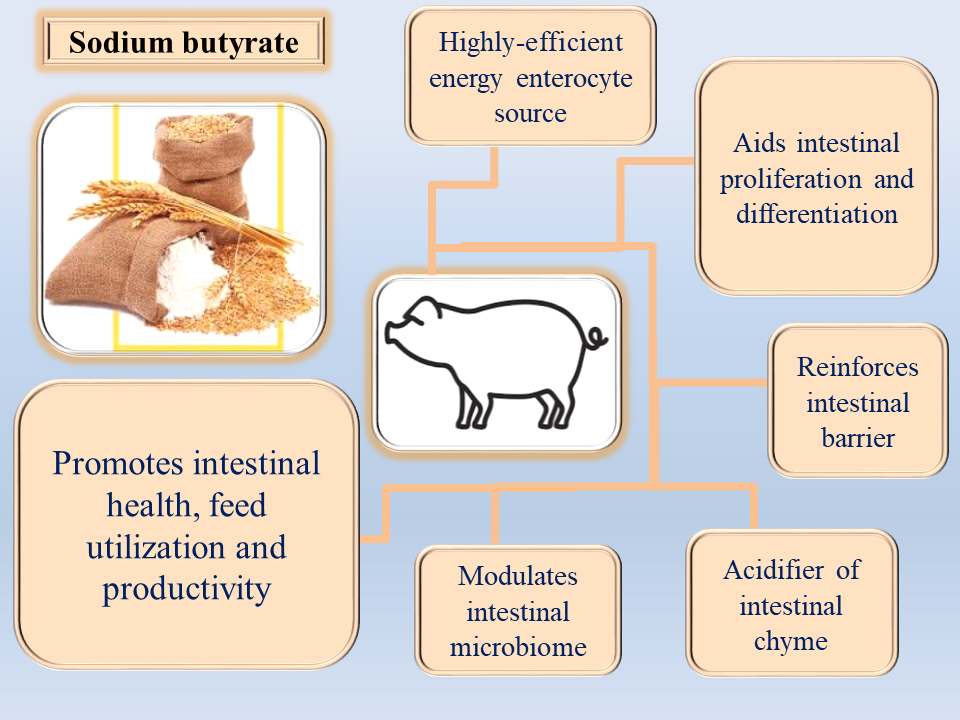

2. SB as a Feed Additive in Pig Production

SB is the sodium salt of butyric acid, with the molecular formula C

4H

7NaO

2, molecular weight 110.09, density 1.324 g/cm

3 (30 °C), and melting point 250–253 °C. It is a white crystalline substance or amorphous powder, highly soluble in water (>330 g/L) [

46,

47]. SB is widely utilized in human medicine, dietetics, and animal husbandry. In humans, research has focused on its role in intestinal homeostasis and as a potential therapeutic agent for gastrointestinal disorders [

48]. Butyrate, produced by the gut microbiota through the fermentation of dietary fiber, serves as a primary energy source for colonocytes and plays a critical role in gastrointestinal health by supporting cell function, maintaining the intestinal barrier, modulating the microenvironment, and reducing inflammation [

49,

50,

51,

52].

The beneficial effects of butyrate are largely attributed to its trophic function in the intestinal epithelium, where it promotes the renewal of damaged cells, regulates luminal pH, inhibits pathogenic microbes, modulates the microbiota, and improves nutrient absorption [

53]. These properties, whether via endogenous microbial production or oral supplementation, support intestinal metabolism and overall health, thereby enhancing productivity.

In animal husbandry, SB is primarily used as a feed additive in intensive systems such as pig and poultry production. It represents a feasible nutritional strategy to improve feed efficiency and growth performance [

54]. In pigs, butyrate promotes the proliferation and renewal of intestinal cells, improves mucosal morphology, and maintains the integrity of the intestinal wall, thereby enhancing nutrient digestion and absorption [

45,

55,

56]. Furthermore, SB strengthens the intestinal barrier by suppressing inflammation and enhancing protective mechanisms [

57,

58], modulates microbial balance by favoring beneficial bacteria over pathogens [

59,

60], and reduces post-weaning diarrhoea and other gastrointestinal disorders [

57,

61].

The dual benefits of SB include improving animal health and productivity [

62,

63,

64] while mitigating environmental impacts, such as reducing ammonia emissions from manure [

60,

65,

66].

Given its multifaceted effects on intestinal health, growth performance, and environmental sustainability, SB offers significant opportunities in pig production. The aim of this review is to summarize current knowledge regarding the use of sodium butyrate as a feed additive in pig nutrition, highlighting its mechanisms of action, benefits, and practical applications.

3. Effect of Sodium Butyrate on the Intestinal Microbiome

The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is a complex ecosystem that critically influences animal health and productivity. The gut microbiome plays a central role in nutrient absorption, immune function, and the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis, all of which directly impact pig performance [

67]. A healthy porcine gut harbors a diverse microbial population, with beneficial bacteria predominantly belonging to the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla, which together account for 85–90% of the microbial population in the GIT [

68,

69].

The composition and activity of the gut microbiome are dynamic and influenced by multiple factors, including diet, physiological status, substrate availability, pH, SCFAs, bile acids, and oxygen gradients. This spatial and temporal heterogeneity complicates direct comparisons between studies but underscores the importance of microbiome modulation as a strategy to improve pig health and growth efficiency [

67,

70]. Weaning represents a particularly critical period: the abrupt transition from milk to solid feed induces drastic changes in microbiota structure, and it typically takes 2–3 weeks for the large intestine to restore fermentation capacity [

71,

72,

73].

SB, administered as a feed additive, provides an opportunity to stabilize the gut microbiome during these vulnerable periods. It can be delivered directly or indirectly by promoting butyrate-producing microbes through prebiotic or probiotic supplementation [

53]. Although additional SB does not always lead to higher luminal concentrations [

74,

75], it can favorably modulate microbiota composition, increasing the abundance of SCFA-producing anaerobes such as

Clostridium spp. and

Prevotella [

59,

60,

69]. Supplementation with probiotic strains, including

Clostridium butyricum, can further enhance endogenous butyrate production and support intestinal homeostasis [

21,

76].

Endogenous butyrate is produced by microbial fermentation of undigested polysaccharides, oligosaccharides, and disaccharides in the large intestine [

43]. Fermentation yields pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, and butyryl-CoA, which is converted to butyrate via two major bacterial pathways: (i) the butyryl-CoA:acetate transferase pathway, utilized by species such as

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and

Roseburia, and (ii) the butyrate kinase pathway, predominant in

Clostridium butyricum and

Coprococcus spp. [

49]. Some bacteria also use fermentation end-products like acetate, lactate, or succinate to produce butyrate. The rate and quantity of butyrate production depend on microbiota composition, substrate type and availability, and feed composition [

43].

Butyrate and other SCFAs exert bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects, acting as natural modulators of mucosal growth, energy metabolism, and pathogen suppression [

11,

25,

26,

77]. The undissociated acid penetrates bacterial membranes, dissociates in the cytoplasm, lowers intracellular pH, denatures enzymes, and disrupts membranes, selectively reducing pathogenic bacteria while supporting beneficial species [

11,

25].

Butyrate also modulates microbial fermentation, alters bacterial populations, and lowers colonic pH, which inhibits the growth of pH-sensitive pathogens such as

Escherichia coli,

Salmonella spp., and

Clostridium perfringens, while promoting acid-tolerant beneficial bacteria like lactobacilli. The resulting increase in SCFA-producing anaerobes further enhances intestinal health and reduces pathogen load [

43,

52,

69,

78]. Studies in weaned, growing, and fattening pigs demonstrate similar benefits, including reduced Salmonella colonization in the gut, lymphatic tissues, and blood [

33,

55,

62,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84].

The impact of SB on the intestinal microbiome is highly context-dependent, influenced by age, health status, diet composition, management, dosage, duration, and interactions with other feed additives. When appropriately applied, SB supplementation can significantly improve intestinal microbial balance, support gut health, and enhance productivity in pigs.

4. Effects of Sodium Butyrate on Intestinal Morphology

Microbial fermentation in the large intestine contributes approximately 16.4% of the total energy required for vital processes in pigs, with butyrate being one of its key metabolic products [

73]. Butyrate has received particular attention as a primary energy source for colonocytes [

50,

85]. Absorption of butyrate and other SCFAs occurs through the apical membrane of colonocytes via multiple mechanisms, including passive diffusion of the undissociated form and active transport of the dissociated form through specific SCFA transporters, such as monocarboxylate-bicarbonate and Na

+-linked monocarboxylate transporters [

52]. Once absorbed, colonocytes rapidly metabolize butyrate through β-oxidation to acetyl-CoA, which serves as a key substrate for ATP (Adenosine triphosphate) production, supporting the energy needs of rapidly proliferating cells and reducing intestinal permeability, particularly during weaning [

43,

54,

71].

Butyrate stimulates cellular renewal and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium, influencing tissue growth and proliferation mechanisms [

86]. While microbial fermentation naturally produces butyrate in the large intestine, oral supplementation with feed additives such as SB can increase its availability throughout the GIT. The trophic effects of butyrate span the entire intestinal epithelium, enhancing villus height, crypt depth, and goblet cell number and density, which collectively increase the absorptive surface area of the small intestine [

43].

Multiple studies have reported positive effects of SB supplementation on intestinal histology in pigs, including improvements in the stomach and various intestinal segments [

36,

43,

55,

62,

63,

79,

86]. However, results are not entirely consistent. During the critical weaning period, some studies report no significant morphological changes following SB supplementation [

56,

74], potentially due to factors such as weaning age, additional stressors, or pre-existing disease. Similarly, Morel et al. [

87] observed no histological changes in the ileum of pigs from the growing to finishing stage when fed SB, benzoic acid, or their combination, suggesting that age may influence the responsiveness to organic acids.

Conversely, several studies highlight stronger trophic effects when SB is administered during early weaning or suckling periods, when the small and large intestines are rapidly growing [

88,

89]. During these stages, SB enhances proliferation of intestinal cells, improves mucosal morphology, and increases nutrient absorption capacity.

Weaning represents a critical period in piglet development, often associated with impaired intestinal health, altered morphology, microbial dysbiosis, and reduced growth performance due to stress and immature digestive function [

71,

90,

91]. Feed additives such as SB are generally most effective in young animals, where they can improve growth, support intestinal development, and reduce neonatal mortality [

73]. Although results are sometimes inconsistent, the majority of studies indicate that SB positively influences gastrointestinal morphology, particularly in suckling pigs.

Overall, the effect of SB on intestinal morphology is pronounced in early-life pigs but is highly dependent on factors such as age, physiological status, weaning practices, stress levels, diet composition, and administration strategies. Careful consideration of these variables is necessary to maximize the benefits of SB supplementation in pig production.

5. Immunomodulatory Properties of Sodium Butyrate

The protective function of the intestinal mucosa is closely linked to its integrity and histological structure. In addition to its trophic effects on colonic mucosa, butyrate plays a central role in regulating intestinal homeostasis and immunity, exerting anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, and barrier-protective effects [

48].

The intestinal ecosystem comprises the epithelium, immune cells, enteric neurons, microbiota and its metabolites, and nutrients, all of which contribute to mucosal defense and overall gut health [

52]. These components form the basis for nutritional and management strategies aimed at improving health and productivity in pigs [

71]. At the mucosal level, butyrate enhances intestinal protection by reducing inflammation, mitigating oxidative stress, and reinforcing the mucosal barrier [

50].

Activation of mucosal mast cells is a critical factor associated with decreased barrier function, particularly in early-weaned pigs [

92]). Butyrate mediates anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting mast cell activation and suppressing the release of inflammatory mediators, including histamine, tryptase, and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. These effects contribute to reduced intestinal damage, enhanced barrier integrity, and improved growth performance in weaned pigs [

45,

55].

Sodium butyrate has also been shown to modulate humoral immunity. Supplementation in sows increases immunoglobulin A (IgA) content in colostrum, supporting better growth and health of piglets during the suckling period [

44,

58]. In addition, SB administration in pig feed can enhance systemic and mucosal immune responses, as evidenced by increased serum IgG and IgA concentrations in jejunal tissues [

57].

Beyond immunoglobulin regulation, butyrate strengthens the intestinal barrier by enhancing tight junction integrity, stimulating mucin production, and promoting antimicrobial peptide secretion, thereby providing robust protection against pathogens [

52]. Studies in pigs fed with protected SB have demonstrated increased numbers of goblet and mucin-secreting cells in the ileum, resulting in improved intestinal defense and overall gut health [

80].

Collectively, these findings indicate that SB not only supports intestinal morphology and nutrient absorption but also exerts profound immunomodulatory effects, enhancing the resilience of pigs to gastrointestinal challenges and contributing to improved health and productivity.

6. Immunomodulatory Properties of SB

The microbiome, one of the components characterizing intestinal homeostasis, is a functional unit related to the metabolism of nutrients and the efficiency of feed-absorbed substrates, directly affecting productivity [

54,

73]. During digestion, most of the available nutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, fats, minerals and vitamins) are absorbed in the small intestine, and in the large intestine continue the undigested by the enzymes components of food (crude fiber, lipids and insoluble protein) and endogenous secretions that are fermented by microorganisms [

93]. This microbial fermentation process for carbohydrates (sucrolytic bacterial fermentation) occurs primarily in the proximal colon. In the distal colon, with their depletion as an energy substrate, proteins (proteolytic fermentation) are broken down with the formation of SCFAs, mainly branched chain (iso-butyrate, valerate and iso-valerate) and potentially toxic ammonia metabolites containing sulfur compounds, indoles and phenols [

50,

94].

Ammonia (NH

3) derived from protein fermentation in the gut is among the major odorous compounds contributing to unpleasant sensations in pig farms [

60]. If the ammonia content of the air in the area with animal is above the optimal values, which range between 10-25 ppm [

95], it is irritating to the lungs and leads to health problems with negative consequences for both pigs and personnel [

18,

19]. Ammonia released by the livestock industry is an environmental pollutant affecting air, soil, water, biodiversity and is a prerequisite for serious local or global environmental crises [

15]. The fecal load itself has a negligible contribution to directly endangering animal health and the environment, compared to the amounts excreted by the mixing of urine and the urea contained in it, with fecal microorganisms containing the enzyme urease, which catalyzes hydrolysis [

95]. The concentration of NH

3 and the equilibrium between ionized NH

4+ and non-ionized NH

3 in the buildings directly depends on the temperature in them and the pH of the manure. It rises at higher temperatures and pH above 7 [

96], and the decrease in the pH of manure strongly influences the dissociation of total ammonia N and the effective reduction of NH

3 emissions [

97].

The main factors determining the quantities NH

3 are related to the housing conditions (type of floor, manure removal system and climatic conditions in the building), features characterizing the animals (physiological stage, age) and feed efficiency (composition of mixtures, phase feeding) [

15,

78,

96,

97]. They are most often taken into account when developing approaches for the correct management of N emissions from pig farms. In order to limit N losses and increase the sustainability of pork production, the efficiency of protein conversion should be maximised [

98]. Effective utilization of N (nitrogen) is economically important, due to the continuous increase in the prices of protein feed [

17] and it has environmental importance, because N in food is a major cause of the high ammonia levels in pig rearing in the conditions of modern industrial production [

96].

The nutritional strategies for pigs for reducing emitted NH

3 and N are interconnected, aimed at modifying the intestinal microbiome to reduce ammonia precursors and protein fermentation, shifting the pathway of excretion of N from urine to feces and lowering their pH. This is achieved through various models: reducing the amount of raw protein in the feeds; optimizing the protein content in combined feed, according to the specific needs; balance of the amino acids in the feed; the use of sources containing N with slow release; inclusion of fermenting carbohydrates; enzymes; food additives, aiding directly or indirectly the absorption of N-probiotics, enzymes, acidifiers, etc [

15,

23,

78,

93,

95,

98].

In pig farming as feed acidifiers are used organic acids, by themselves or in combinations with each other, with predominant participation of SCFA [

25]. Fermentation of undigested polysaccharides in the colon leads to acidification of the intestinal humus. As a result of the decay of the produced SCFA, the hydrogen ions emitted provoke a decrease in the pH of feces and ammonia emissions [

93]. In in vitro trials was found that organic acids (phosphoric, citric, fumaric and malic acids) had a positive influence on ammonia emissions in the caecal fermentation of feed with carbohydrate content [

22]. A similar result was reported by Upadhaya et al. [

23] when feeding pigs with the addition of a protected combination of organic acids. In a study by adding 0.03% SB to pig feed was found a reduction in emissions not only of ammonia but also of hydrogen sulphide and total gas [

60]. Other studies have indicated a positive impact of SB supplementation on hydrogen sulphide emissions only [

79]) or total gas emissions [

74] with neutral or negative impact on released ammonia.

The increase in SCFA concentration is associated with changes in the composition of the gut microbiome [

67]. Sodium butyrate can regulate NH

3 substrates producing NH

3 and some NH

3-producing microorganisms [

60]. Ammonia concentrations in the intestinal lumen can be reduced by active carbohydrate fermentation, which stimulates the bacterial need for N due to increased growth [

79] and the energy provided for it by butyrate in the form of ATP. A potential solution for a mutually reinforcing effect is a reduction of crude protein in food, without limiting the amounts of N and amino acids needed for protein synthesis and to avoid compromising growth [

53,

94,

97,

99].

Ammonia is the main waste product of amino acid catabolism (deamination), detoxified in the liver by urea synthesis. Most of it is excreted in the urine, but the ability in pigs to use a mechanism to convert it into amino acids for protein synthesis for the host is an option for N utilization [

100]. The available amounts of urea in the blood are a key source of N for bacterial proliferation in the colon [

93]. SB supplementation was found to have a benefitial influence in suckling pigs by reducing urea concentration in blood without affecting other haematological parameters [

62]. Fang et al. [

57] presented results of the use of SB in weanling pigs, which showed lower serum concentrations of urea N, cortisol, D-lactic acid, diamine oxidase, and higher for glucose and triglycerides with which the authors connect the more efficient N utilization. The concentration of urea in manure is highly dependent on protein nutrition and can be altered by changing the protein content of the diet [

93].

The information established so far gives indications and guidance for a positive impact on the harmful gas emissions generated in pig production by the addition of butyrates in compound feed for pigs, but further in-depth in vivo experiments would bring greater clarity.

7. Role of Sodium Butyrate in Nitrogen Optimization and Mitigation of Harmful Gas Emissions

The intestinal microbiome, a key component of gut homeostasis, plays a central role in nutrient metabolism and feed efficiency, directly influencing pig productivity [

54,

73]. During digestion, most nutrients—including carbohydrates, proteins, fats, minerals, and vitamins—are absorbed in the small intestine. Undigested components, such as crude fiber, lipids, and insoluble proteins, along with endogenous secretions, reach the large intestine, where microbial fermentation continues [

93].

Carbohydrate fermentation, primarily occurring in the proximal colon, produces SCFAs, while proteolytic fermentation in the distal colon generates branched-chain SCFAs (iso-butyrate, valerate, iso-valerate) and potentially toxic nitrogenous metabolites, including ammonia, indoles, phenols, and sulfur-containing compounds [

50,

94]. Ammonia (NH

3), a by-product of protein fermentation, is a major odorous compound in pig farms and, when exceeding the optimal 10–25 ppm range, can irritate the respiratory system, negatively affecting both pigs and personnel [

18,

19,

95]. Beyond local health impacts, ammonia represents a significant environmental pollutant, contributing to air, soil, and water contamination, biodiversity loss, and broader ecological challenges [

15]. The primary source of NH

3 is the hydrolysis of urea in urine catalyzed by microbial urease, rather than fecal matter alone [

95]. NH

3 concentration and the equilibrium between ionized NH

4+ and non-ionized NH

3 depend on temperature and manure pH, increasing at higher temperatures and pH above 7. Lowering manure pH strongly reduces NH

3 emissions by influencing urea dissociation [

96,

97].

Factors influencing ammonia emissions include housing conditions (floor type, manure removal, building climate), animal characteristics (physiological stage, age), and feed efficiency (composition and phase feeding) [

15,

78,

96,

97]. Consequently, strategies for mitigating N losses focus on maximizing protein utilization, which is both economically and environmentally critical given rising protein feed costs and the environmental impact of N excretion [

17,

96,

98]

Nutritional strategies aimed at reducing ammonia and N excretion include modifying the intestinal microbiome to limit ammonia precursors, shifting N excretion from urine to feces, and lowering fecal pH. Methods include reducing raw protein in feeds, optimizing dietary protein according to animal requirements, balancing amino acid composition, using slow-release N sources, and supplementing with fermentable carbohydrates, enzymes, probiotics, and acidifiers [

15,

23,

78,

93,

95,

98].

In pig nutrition, organic acids—especially SCFAs such as sodium butyrate—are used as feed acidifiers, either alone or in combinations [

25]. Fermentation of undigested polysaccharides in the colon produces SCFAs, releasing hydrogen ions that acidify intestinal contents and feces, thereby reducing ammonia emissions [

93]. In vitro studies demonstrated that organic acids (phosphoric, citric, fumaric, and malic acids) effectively reduced ammonia emissions during caecal fermentation of carbohydrate-rich feed [

22]. Similarly, feeding pigs protected combinations of organic acids reduced ammonia release [

23]. Sodium butyrate supplementation at 0.03% of feed has been shown to reduce emissions of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and total gases [

60], although some studies observed reductions primarily in hydrogen sulfide [

79] or total gas [

74] with minimal effects on ammonia.

The beneficial effects of SB on N metabolism are linked to its influence on gut microbiota composition and microbial N utilization. By stimulating carbohydrate fermentation, SB promotes bacterial growth and N incorporation into microbial protein, providing energy in the form of ATP and reducing ammonia concentration in the gut [

60,

67,

79]. This effect can be synergistically enhanced by reducing dietary crude protein without compromising essential N and amino acid availability for host protein synthesis [

53,

94,

97,

99].

Ammonia is primarily a waste product of amino acid catabolism, detoxified in the liver via urea synthesis and excreted mainly in urine. Blood urea also provides N source for microbial proliferation in the colon [

93,

100]. SB supplementation has been shown to reduce blood urea levels in suckling pigs without affecting other hematological parameters [

62], while in weaned pigs it improved N utilization efficiency, as evidenced by reduced serum urea, N, cortisol, D-lactic acid, and diamine oxidase, alongside increased glucose and triglycerides [

57]. The urea content in manure is closely related to dietary protein and can be modulated by feed composition [

93].

Overall, current evidence suggests that SB supplementation in pig diets can improve N utilization, reduce harmful gas emissions, and support sustainable production practices. However, further controlled in vivo studies are required to clarify the magnitude, mechanisms, and consistency of these effects under different production conditions.

8. Effect of Sodium Butyrate SB Supplementation on Productive Traits in Pigs

Economic efficiency in pig production largely depends on the reproductive performance of sows and the growth and feed conversion efficiency of pigs during the fattening period. Maximizing growth rate while minimizing feed consumption remains a central objective for swine producers. In this context, dietary supplementation with sodium SB has been investigated as a nutritional strategy to enhance productivity across different physiological stages in pigs.

In sows, the inclusion of SB during the final stage of gestation has been associated with improved reproductive outcomes and subsequent piglet performance during lactation. Studies have reported a reduced proportion of gilts failing to conceive and higher piglet growth rates during lactation following SB supplementation, effects that were attributed in part to enhanced colostrum and milk quality [

44].

Most research on SB has focused on its use during the critical post-weaning period, which is associated with substantial physiological and metabolic challenges. Consistent with its role in mitigating weaning-associated stress, SB supplementation has been linked to improved growth performance in weaned pigs. Positive responses were reported when SB was added at 0.45 kg/t feed in piglets weaned at 28 days [

45] and at 1.0 kg/t feed in piglets weaned earlier, at 21 days of age [

55]. Similar improvements in growth performance have also been observed in older and fattening pigs [

63,

87,

88]. However, not all studies have confirmed these effects, with some reporting neutral outcomes even at higher inclusion levels (2.0–4.0 kg/t feed) [

74].

The characteristic cheese-like aroma of butyrate is considered palatable to pigs and may stimulate feed intake. However, results regarding its influence on average daily feed intake (ADFI) remain inconsistent. While some studies demonstrated increased ADFI in fattening pigs fed SB-supplemented diets [

87]), others reported no significant effects on ADFI in weaned pigs [

36,

57,

102], even at inclusion rates up to 2.0 kg SB/t feed [

103]. Similarly, Walia et al. [

81] observed no changes in ADFI, growth, or feed conversion ratio in pigs fed diets containing 3.0 kg SB/t. In contrast, Sun et al. [

63] reported that dietary supplementation with 0.2% SB increased final body weight, ADFI, and feed efficiency, findings consistent with those of Morel et al. [

87].

The variability in responses observed among studies may be attributed to differences in dietary composition, SB dosage, feed formulation, animal age, intestinal maturity, duration of supplementation, and experimental conditions [

79]. These factors underscore the importance of context-specific optimization of SB inclusion levels to achieve consistent improvements in pig growth and feed efficiency.

9. Impact of SB on Pork Meat Quality

The use of functional feed additives that enhance growth performance and nutrient utilization in pigs can have consequential effects on meat quality. Intensive growth rates are frequently associated with increased deposition of intramuscular fat, which contributes to improved flavor, juiciness, and tenderness of pork [

104]. In this context, SB supplementation has been investigated for its potential to modulate muscle development and lipid metabolism, thereby influencing the overall sensory and technological properties of pork.

Zhang et al. [

105] reported that dietary inclusion of SB improved intramuscular fat content, muscle marbling, post mortem muscle pH (pH

24h), and meat tenderness, suggesting a beneficial effect on pork quality traits. Similarly, Sun et al. [

63] observed enhanced carcass characteristics in finishing pigs supplemented with SB. In contrast, Morel et al. [

87] found no significant differences in key meat quality parameters between control and SB-fed pigs, indicating that the response to SB supplementation may vary depending on production conditions and experimental design.

Although SB demonstrates promising potential for improving both growth and meat quality traits, findings across studies remain inconsistent. The variability may be attributed to differences in SB dosage, duration of supplementation, animal age, genetic background, and feeding phase. Furthermore, environmental and management factors—including housing, feed formulation, and health status—may influence the degree of SB responsiveness.

In general, current evidence suggests that SB can contribute to improved pork quality under specific conditions, particularly by promoting favorable muscle characteristics and lipid deposition. However, further well-controlled studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms by which SB affects muscle metabolism and to establish optimal inclusion levels and feeding strategies for consistent improvements in pork quality.

10. Cost-Effectiveness of SB Feed Additive

Economic evaluation is a crucial component in determining the feasibility of using feed additives such as SB in commercial pig production. While numerous studies have demonstrated the biological and physiological benefits of SB supplementation—including improved gut health, nutrient absorption, and growth performance—its practical application must also be justified through comprehensive cost-benefit analysis. Feed costs account for the majority of total production expenses in pig farming; therefore, any additive must demonstrate economic viability in addition to animal breeding efficacy.

The financial implications of SB supplementation vary depending on production conditions, dosage, formulation, and category of pigs. Lynch et al. [

83] reported that the inclusion of SB in diets for growing pigs increased overall feeding costs, primarily due to the higher price of butyrate-enriched feed formulations. Conversely, Galfi and Bokori [

62] observed a favorable economic balance in pigs supplemented with SB, attributing the improved profitability to enhanced growth performance and feed conversion efficiency. Such contrasting findings highlight the importance of optimizing both the form and inclusion rate of SB to achieve cost-effectiveness.

Upadhaya et al. [

79]) suggested that cost reduction and improved profitability could be achieved through the use of microencapsulated SB, which allows for gradual release along the GIT. This technology enhances the additive’s bioavailability and efficacy, thereby reducing the required dosage without compromising performance benefits. By minimizing waste and improving intestinal health, encapsulated SB formulations may offer a more sustainable and economically viable strategy for commercial application.

Comprehensive financial assessments, considering both the additive cost and the potential improvements in feed efficiency, growth rate, and health status, are therefore essential for large-scale adoption. Further research should focus on developing standardized economic models tailored to different production systems and pig categories to provide clear guidelines on the cost-effectiveness of SB supplementation under diverse farming conditions.

11. Conclusions

SB, when used as a feed additive, demonstrates multiple well-documented benefits, including the enhancement of intestinal morphology, modulation of local innate immunity, and regulation of the gut microbiome. These effects contribute to the improvement of key productivity indicators—reproductive performance, growth, and carcass quality—particularly in intensive pig farming systems.

The post-weaning period is the most extensively studied phase for SB supplementation, where it has shown potential to mitigate the negative effects of post-weaning stress (PWS), a critical concern in early- to mid-early weaning systems. In contrast, results during the fattening period are more variable and appear to depend on factors such as dosage, age, duration of supplementation, and farm management practices.

Beyond production performance, SB also offers environmental benefits by improving N utilization and reducing the N footprint, contributing to more sustainable pig farming practices. Its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and proliferative properties position SB as a promising alternative to traditional nutritional antibiotics, enhancing animal health and welfare while supporting ecologically responsible livestock production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B. methodology, K.B.; methodology, K.D.; investigation, K.B..; resources, K.B; writing—original draft preparation, K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.D.; writing—review and editing, K.B.; writing—review and editing, K.D.; supervision, K.B.; project administration, K.B.; funding acquisition, K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by “Faculty of Agriculture, Trakia University, Stara Zagora, grant number “AF/23 – University research project” and “The APC was funded by “ Project No. BG-RRP-2.004-0006 “Development of scientific research and innovation at Thrace University in the service of health and sustainable well-being”.

Acknowledgments

The team involved in the UNIVERSITY RESEARCH PROJECT – 5AF/23 expresses sincere gratitude to the Faculty of Agriculture, Trakia University, Stara Zagora, for the support and funding provided, which made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADFI Average daily feed intake |

| ATP Adenosine triphosphate |

| GIT Gastrointestinal tract |

| N Nitrogen |

| PWS Post weaning stress |

| SCFAs Short-chain fatty acids |

| SB Sodium butyrate |

| IgA Immunoglobulin A |

References

- European Environment Agency (EEA, 2019). Changing menus, changing landscapes – Agriculture and food in Europe. https://www.eea.europa.eu/bg/signals/signali-2019-g/statii/promyana-na-hranitelnite-navitsi-promyana, November 15, 2025.

- Maes D.; Dewulf J.; Pineiro C.; Edwards S; Kyriazakis I. A critical reflection on intensive pork production with an emphasis on animal health and welfare. J Anim Sci. 2020, 98(Suppl 1), 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Casa E.L.de la. Intensive pig farming: Ethical considerations. Derecho Animal Forum of Animal Law Studies August 2017, 8(3):1. [CrossRef]

- Delsart M.; Pol F.; Dufour B.; Rose N.; Fablet C. Pig Farming in Alternative Systems: Strengths and Challenges in Terms of Animal Welfare, Biosecurity, Animal Health and Pork Safety. Agriculture 2020, 10(7), 261. [CrossRef]

- De Brito S.A.P.; Duarte G.D.; Sobral F.E.daS., Christoffersen M.L. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF SWINE FARMING. Environmental Smoke 2022, 5(3), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Cromwell G.L. Why and how antibiotics are used in swine production. Anim Biotechnol. 2002, 13(1), 7-27. [CrossRef]

- Bradford H.; McKernan C.; Elliott C.; Dean M. Factors influencing pig farmers’ perceptions and attitudes towards antimicrobial use and resistance. Prev. Vet. Med. 2022, 208, 105769. [CrossRef]

- Monger X.C.; Gilbert A.-A.; Saucier L.; Vincent A.T. Antibiotic Resistance: From Pig to Meat. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10(10), 1209. [CrossRef]

- Chen J.; Ying G.; Deng W. Antibiotic Residues in Food: Extraction, Analysis, and Human Health Concerns. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67(27), 7569–7586. [CrossRef]

- Menkem E.Z.; Ngangom B.L.; Tamunjoh S.S.A.; Boyom F.F. Antibiotic residues in food animals: Public health concern. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39(5), 411-415. [CrossRef]

- Heo J.M.; Opapeju F.O.; Pluske J.R.; Kim J.C.; Hampson D.J.; Nyachoti C.M. Gastrointestinal health and function in weaned pigs: a review of feeding strategies to control post-weaning diarrhoea without using in-feed antimicrobial compounds. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2012, 97(2), 207–237. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y.; Espinosa C.D.; Abelilla J.J.; Casas G.A.; Lagos L.V.; Lee S.A.; Kwon W.B.; Mathai J.K.; Navarro D.M.D.L.; Jaworski N.W.; Stein H.H. Non-antibiotic feed additives in diets for pigs: A review. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4(2), 113–125. [CrossRef]

- Ikusika, O.; Haruzivi, C.; Mpendulo, T. Alternatives to the Use of Antibiotics in Animal Production. Chapter 4 In Book: Antibiotics and Probiotics in Animal Food - Impact and Regulation, Kamboh, A., Payan-Carreira, R.; 05 December 2022, UK. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Downing M.M.; Nejadhashemi A.P.; Harrigan T.; Woznicki S.A. Climate change and livestock: Impacts, adaptation, and mitigation. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 145-163. [CrossRef]

- Ball M.E.E.; Smyth S.; Beattie V.E.; McCracken K.J., McCormack U.; Muns R.;Gordon F.J.; Bradford R.; Reid L.A.; Magowan E. The Environmental Impact of Lowering Dietary Crude Protein in Finishing Pig Diets—The Effect on Ammonia, Odour and Slurry Production. Sustainability 2022, 14(19), 12016. [CrossRef]

- Garry B.P.; Fogarty M.; Curran T.P.; O’Doherty J.V. Effect of cereal type and exogenous enzyme supplementation in pig diets on odour and ammonia emissions. Livest. Sci. 2007, 109(1–3), 212-215. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen D.H.; Lee S.I.; Cheong J.Y.; Kim I.H. Influence of low-protein diets and protease and bromelain supplementation on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, blood urine nitrogen, creatinine, and faecal noxious gas in growing–finishing pigs. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 98(3), 488-497. [CrossRef]

- Kim J.-H.; Ko G.-P.; Son K.-H.; Ku B.-H.; Bang M.-A.; Kang M.-J.; Park H.-Y. Arazyme in combination with dietary carbohydrolases influences odor emission and gut microbiome in growing-finishing pigs. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157735. [CrossRef]

- Aufy A.; Zentner E.; Steiner T., Phytogenic Feed Additives and Ammonia Emissions – Thinking outside the Box. 6 December 2011, The Pig Site: https://www.thepigsite.com/articles/phytogenic-feed-additives-and-ammonia-emissions-thinking-outside-the-box, November 15, 2025.

- Tufarelli V.; Rossi G.; Laudadio V.; Crovace A. Effect of a dietary probiotic blend on performance, blood characteristics, meat quality and faecal microbial shedding in growing-finishing pigs. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 47, No. 6. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-af36a9892.

- Nguyen D.H.; Nyachoti C.M.; Kim I.H. Evaluation of effect of probiotics mixture supplementation on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, faecal bacterial enumeration, and noxious gas emission in weaning pigs. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 18(1), 466-473. [CrossRef]

- Piva A.; Casadei G.; Biagi G. An organic acid blend can modulate swine intestinal fermentation and reduce microbial proteolysis. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 82(4), 527-532. [CrossRef]

- Upadhaya S.D.; Lee K.Y.; Kim I.H. Protected Organic Acid Blends as an Alternative to Antibiotics in Finishing Pigs. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2014, 27(11), 1600-7. [CrossRef]

- Suiryanrayna M.V.A.N.; Ramana J.V. A review of the effects of dietary organic acids fed to swine. J. anim. sci. biotechnol. 2015, 6(1), 45. [CrossRef]

- Tugnoli B.; Giovagnoni G.; Piva A.; Grilli E. From Acidifiers to Intestinal Health Enhancers: How Organic Acids Can Improve Growth Efficiency of Pigs. Animals 2020, 10(1), 134. [CrossRef]

- Mroz Z. Organic Acids as Potential Alternatives to Antibiotic Growth Promoters for Pigs. Advances in Pork Production 2005, 16, 169.

- Piva A.; Grilli E.; Fabbri L.; Pizzamiglio V.; Campani I. Free versus microencapsulated organic acids in medicated or not medicated diet for piglets. Livest. Sci.2007, 108(1-3), 214-217. [CrossRef]

- C Jia G.; Yan J.-Y.; Cai J.-Y.; Wang K.-N. Effects of encapsulated and non-encapsulated compound acidifiers on gastrointestinal pH and intestinal morphology and function in weaning piglets. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2010, 19(1), 81-92. [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert G.; Ducatelle R.; Immerseel F.Van. An update on alternatives to antimicrobial growth promoters for broilers. Vet J. 2011, 187(2), 182-8. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk E.; Temiz U. Encapsulation Methods and Use in Animal Nutrition. Selcuk J Agr Food Sci 2018, 32(3), 624-631. [CrossRef]

- Giannenas I. A. Organic acids in pig and poultry nutrition. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2017, 57(1), 51–62. [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Higes A.; Andrés-Barranco S., Mainar-Jaime R.C. Short communication: Use of a new form of protected sodium butyrate to control Salmonella infection in fattening pigs. Span. j. agric. res. 2018, 16(4), e05SC02. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L.L.; Feng J.; Li H.; Zeng X.F.; Yang C.M. Effects of plant essential oil and sodium butyrate compound preparation on growth performance, serum antioxidant indices, fecal flora and ammonia loss of weaner piglets. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 30(2), 678-684. https://manu17.magtech.com.cn/dwyy/CN/abstract/html/20180233.htm.

- Nowak P.; Kasprowicz-Potocka M.; Zaworska A.; Nowak W.; Stefańska B.; Sip A.; Grajek W.; Grajek K.; Frankiewicz A. The Effect of Combined Feed Additives on Growing Pigs’ Performance and Digestive Tract Parameters. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2019, 19(3), 807-819. [CrossRef]

- Luise D.; Correa F.; Bosi P.; Trevisi P. A Review of the Effect of Formic Acid and Its Salts on the Gastrointestinal Microbiota and Performance of Pigs. Animals 2020, 10(5), 887. [CrossRef]

- Zeng X.; Yang Y.; Wang J.; Wang Z.; Li J.; Yin Y.; Yang H. Dietary butyrate, lauric acid and stearic acid improve gut morphology and epithelial cell turnover in weaned piglets. Anim Nutr. 2022, 11, 276-282. [CrossRef]

- You C.; Xu Q.; Chen J.; Xu Y.; Pang J.; Peng X.; Tang Z.; Sun W.; Sun Z. Effects of Different Combinations of Sodium Butyrate, Medium-Chain Fatty Acids and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on the Reproductive Performance of Sows and Biochemical Parameters, Oxidative Status and Intestinal Health of Their Offspring. Animals 2023, 13(6), 1093. [CrossRef]

- Kasubuchi M.; Hasegawa S.; Hiramatsu T.; Ichimura A.; Kimura I. Dietary gut microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, and host metabolic regulation. Nutrients. 2015, 7(4), 2839-49. [CrossRef]

- Bergman E.N. Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various species. Physiol Rev. 1990, 70(2), 567-90. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg I., Rokem J., 2009. Organic and Fatty Acid Production, Microbial. In book: Encyclopedia of Microbiology; Schaechter, M., San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, USA, December 2009, pp.421-442. [CrossRef]

- Huang J.; Tang W.; Zhu S.; Du M. Biosynthesis of butyric acid by Clostridium tyrobutyricum. Prep Biochem & Biotechnol. 2018, 48(5), 427-434. [CrossRef]

- Claus R.; Günthner D.; Letzguss H. Effects of feeding fat-coated butyrate on mucosal morphology and function in the small intestine of the pig. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2007, 91(7/8), 312-8. [CrossRef]

- Guilloteau P.; Martin L., Eeckhaut V., Ducatelle. R., Zabielski R., Van Immerseel. From the gut to the peripheral tissues: The multiple effects of butyrate. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010, 23(2), 366–384. [CrossRef]

- He B.; Wang M.; Guo H.; Jia Y.; Yang X.; Zhao R. Effects of sodium butyrate supplementation on reproductive performance and colostrum composition in gilts. Animal 2016, 10(10), 1722-7. [CrossRef]

- Wang C.C.; Wu H.; Lin F.H.; Gong R.; Xie F.; Peng Y.; Feng J.; Hu C.H. Sodium butyrate enhances intestinal integrity, inhibits mast cell activation, inflammatory mediator production and JNK signaling pathway in weaned pigs. Innate Immun. 2018, 24(1), 40-46. [CrossRef]

- ACS, 2021. Molecule of the Week Archive Sodium butyrate. https://www.acs.org/molecule-of-the-week/archive/s/sodium-butyrate.html, November 15, 2025.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, 2025). PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5222465, Sodium Butyrate. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Sodium-Butyrate, November 15, 2025.

- Leonel A.; Alvarez-Leite J. Butyrate: Implications for intestinal function. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2012, 15(5), 474-9. [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson K.; El Abbar F.; Dobranowski P.; Manoogian J.; Butcher J.; Figeys D.; Mack D.; Stintzi A. Butyrate’s role in human health and the current progress towards its clinical application to treat gastrointestinal disease. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42(2), 61-75. [CrossRef]

- Hamer H.M.; Jonkers D.; Venema K.,; Vanhoutvin S.; Troost F.J., Brummer R-J. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008, 27(2), 104-19. [CrossRef]

- Liu H.; Wang J.; He T.; Becker S.; Zhang G.; Li D.; Ma X. Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health? Adv Nutr. 2018, 9(1), 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Canani R.B.; Costanzo M.Di; Leone L.; Pedata M.; Meli R.; Calignano A. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17(12), 1519-28. [CrossRef]

- Connolly K.R.; Sweeney T.; O’Doherty, J.V. Sustainable Nutritional Strategies for Gut Health in Weaned Pigs: The Role of Reduced Dietary Crude Protein, Organic Acids and Butyrate Production. Animals 2025, 15(1), 66. [CrossRef]

- Gardiner G.E.; Metzler-Zebeli B.U.; Lawlor P.G. Impact of Intestinal Microbiota on Growth and Feed Efficiency in Pigs: A Review. Microorganisms 2020, 8(12), 1886. [CrossRef]

- Lu J.J.; Zou X.T.; Wang Y.M. Effects of sodium butyrate on the growth performance, intestinal microfl ora and morphology of weanling pigs. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2008, 17(4), 568-578. [CrossRef]

- Le Gall M.; Gallois M.; Sève B.; Louveau I.; Holst J.J.; Oswald I.P.; Lallès J.-P.; Guilloteau P. Comparative effect of orally administered sodium butyrate before or after weaning on growth and several indices of gastrointestinal biology of piglets. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102(9), 1285-1296. [CrossRef]

- Fang C.L.; Sun H.; Wu J.; Niu H.H.; Feng J. Effects of sodium butyrate on growth performance, haematological and immunological characteristics of weanling piglets. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2014, 98(4), 680-5. [CrossRef]

- Jang Y.D.; Lindemann M.D., Monegue H.J.; Monegue J.S. The effect of coated sodium butyrate supplementation in sow and nursery diets on lactation performance and nursery pig growth performance. Livest. Sci. 2017, 195, Pages 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Roca M.; Nofrarías M.; Majo N.; Pérez de Rozas A.M., Segalés J.; Castillo M.; Martín-Orúe S.M.; Espinal A.; Pujols J.; Badiola I. Changes in bacterial population of gastrointestinal tract of weaned pigs fed with different additives. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014(1), 269402. [CrossRef]

- Xu J.; Xie G.; Li X.; Wen X.; Cao Z.; Ma B.; Zou Y.; Zhang N.; Mi J.; Wang Y.; Liao X.; Wu Y. Sodium butyrate reduce ammonia and hydrogen sulfide emissions by regulating bacterial community balance in swine cecal content in vitro. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021, 226, 112827. [CrossRef]

- Piva A.; Morlacchini M.; Casadei G.; Gatta P.P.; Biagi G.; Prandini A. Sodium butyrate improves growth performance of weaned piglets during the first period after weaning. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 1(1), 35-41. [CrossRef]

- Gálfi P., Bokori J., 1990. Feeding trial in pigs with a diet containing sodium n-butyrate. Acta Vet Hung. 1990, 38(1-2), 3-17.

- Sun W.; Sun J.; Li M.; Xu Q.; Zhang X.; Tang Z.; Chen J.; Zhen J.; Sun Z. The effects of dietary sodium butyrate supplementation on the growth performance, carcass traits and intestinal microbiota of growing-finishing pigs. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128(6), 1613-1623. [CrossRef]

- Zhou N.; Tian Y.; Liu W.; Tu B.; Gu T.; Xu W.; Zou K.; Lu L. Effects of quercetin and coated sodium butyrate dietary supplementation in diquat-challenged pullets. Anim Biosci. 2022, 35(9), 1434-1443. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Colom P.; Castillejos L.; Barba-Vidal E.; Zhu Y.; Puyalto M.; Mallo J.J.; Martín-Orúe S.M. Response of gastrointestinal fermentative activity and colonic microbiota to protected sodium butyrate and protected sodium heptanoate in weaned piglets challenged with ETEC F4+. Arch Anim Nutr. 2019, 73(5), 339-359. [CrossRef]

- Zhong Z.; Wang C.; Zhang H.; Mi J.; Liang J.B.; Liao X.; Wu Y.; Wang Y. Sodium butyrate reduces ammonia emissions through glutamate metabolic pathways in cecal microorganisms of laying hens. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022, 233, 113299. [CrossRef]

- Vasquez R.; Oh J.K.; Song J.H.; Kang D.-K. Gut microbiome-produced metabolites in pigs: a review on their biological functions and the influence of probiotics. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022, 64(4), 671-695. [CrossRef]

- C Holman D.B.; Brunelle B.W.; Trachsel J.; Allen H.K. Meta-analysis to define a core microbiota in the Swine gut. MSystems. 2017, 2(3), e00004-17. [CrossRef]

- Bernad-Roche M.; Belles A.; Grasa L., Casanova- Higes A., Mainar-Jaime R.C. Effects of Dietary Supplementation with Protected Sodium Butyrate on Gut Microbiota in Growing-Finishing Pigs. Animals 2021, 11(7), 2137. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L.; Wu. W.; Lee Y.-K.; Xie J.; Zhang H. Spatial Heterogeneity and Co-occurrence of Mucosal and Luminal Microbiome across Swine Intestinal Tract. Front Microbiol. 2018, 9, 48. [CrossRef]

- Tang X.; Xiong K.; Fang R.; Li M. Weaning stress and intestinal health of piglets: A review. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1042778. [CrossRef]

- Li Y.; Wang X.; Wang X.-Q.; Wang J.; Zhao J. Life-long dynamics of the swine gut microbiome and their implications in probiotics development and food safety. Gut Microbes. 2020, 11(6), 1824–1832. [CrossRef]

- Jensen B.B. The impact of feed additives on the microbial ecology of the gut in young pigs. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 1998, 7 (Suppl.1), 45-64. [CrossRef]

- Biagi G.; Piva A.; Moschini M.; Vezzali E.; Roth F.X. Performance, intestinal microflora, and wall morphology of weanling pigs fed sodium butyrate. J Anim Sci. 2007, 85(5), 1184-91. [CrossRef]

- Chiofalo B.; Luigi L.; Presti V.Lo; Agnello A.S.; Montalbano G.; Marino A.M.F., Chiofalo A. Dietary Supplementation of Free or Microcapsulated Sodium Butyrate on Weaned Piglet Performances. J Nutr. Ecol. Food Res. 2014, 2, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Guo P.; Zhang K.; Ma X.; He P. Clostridium species as probiotics: potentials and challenges. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2020, 11(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Hijova E.; Chmelarova A. Short chain fatty acids and colonic health. Bratisl. Lek Listy. 2007, 108(8), 354-358, PMID: 18203540.

- Pearlin B.V.; Muthuvel S.; Govidasamy P.; Villavan M.; Alagawany M.; Farag M.R.; Dhama K.; Gopi M. Role of acidifiers in livestock nutrition and health: A review. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2020, 104(2), 558–569. [CrossRef]

- Upadhaya S.D.; Jiao Y.; Kim Y.M.; Lee K.Y.; Kim I.H. Coated sodium butyrate supplementation to a reduced nutrient diet enhanced the performance and positively impacted villus height and faecal and digesta bacterial composition in weaner pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 265, 114534. [CrossRef]

- Sadurni M.; Barroeta A.C.; Sol C.; Puyalto M.; Castillejos L. Effects of dietary crude protein level and sodium butyrate protected by medium-chain fatty acid salts on performance and gut health in weaned piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad090. [CrossRef]

- Walia K.; Argüello H.; Lynch H.; Leonard F.C.; Grant J.; Yearsley D.; Kelly S.; Duffy G.; Gardiner G.E.; Lawlor P.G. Effect of feeding sodium butyrate in the late finishing period on Salmonella carriage, seroprevalence, and growth of finishing pigs. Prev Vet Med. 2016, 131, 79-86. [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Higes A.; Andrés-Barranco S., Mainar-Jaime R.C. Effect of the addition of protected sodium butyrate to the feed on Salmonella spp. infection dynamics in fattening pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 231, 12-18. [CrossRef]

- Lynch H.; Leonard F.C.; Walia K.; Lawlor P.G.; Duffy G.; Fanning S.; Markey B.K.; Brady C.; Gardiner G.E.; Argüello H. Investigation of in-feed organic acids as a low cost strategy to combat Salmonella in grower pigs. Prev Vet Med. 2017, 139(Pt A), 50-57. [CrossRef]

- Basanta, A.; Ortiz, A., López, A; Carrasco, C. Effect of the addition of high doses of protected sodium butyrate in fattening pigs on Salmonella prevalence. Jornadas sobre Producción Animal, AIDA XVII, 30/05/2017-31/05/2017, Zaragoza, ES, pp 87-89.

- Roediger W.E. Role of Anaerobic Bacteria in the Metabolic Welfare of the Colonic Mucosa in Man. Gut 1980, 21(9), 793-798. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni M.L.; Le Gall M.; De Filippi S.; Minieri L.; Trevisi P.; Wolinski J.; Lalatta-Costerbosa G.; Lalles J.-P.; Guilloteau P.; Bosi P. Supplemental Sodium Butyrate Stimulates Different Gastric Cells in Weaned Pigs. J Nutr. 2008, 138(8), 1426-31. [CrossRef]

- Morel P.C.H.; Chidgey K.L.; Jenkinson C.M.C.; Lizarraga I.; Schreurs N.M. Effect of benzoic acid, sodium butyrate and sodium butyrate coated with benzoic acid on growth performance, digestibility, intestinal morphology and meat quality in grower-finisher pigs. Livest. Sci. 2019, 226, 107-113. [CrossRef]

- Racevičiūtė-Stupelienė A.; Šašytė V.; Vilienė V.; Alijošius S.; Slausgalvis V.; Bauwens S.; Klementavičiūtė J.; Nutautaitė M.; Buckūnienė V.; Paleckaitis M. The Influence of sodium butyrate and vegetable fatty acids on productivity and meat quality of fattening pigs. Vet. zootech. 2018, 76(98), 91-95. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12512/20523.

- Kotunia A.; Woliński J.; Laubitz D.; Jurkowska M.; Romé V.; Guilloteau P.; Zabielski R. Effect of sodium butyrate on the small intestine development in neonatal piglets fed [correction of feed] by artificial sow. J Physiol. Pharmacol. 2004, 55 (Suppl 2), 59-68 PMID: 15608361.

- Lallès J.-P.; Boudry G.; Favier C.; Le Floc’h N.; Luron I.; Montagnea L.; Oswald I.P.; Pié S.; Piel C.; Sève B. Gut function and dysfunction in young pigs: physiology. Anim. Res., 53(4), 301-316. [CrossRef]

- Patil Y.; Gooneratne R.; Ju X.-H. Interactions between host and gut microbiota in domestic pigs: A review. Gut Microbes. 2020, 11(3), 310–334. [CrossRef]

- Moeser A.J.; Ryan K.A.; Nighot P.K.; Blikslager A.T. Gastrointestinal dysfunction induced by early weaning is attenuated by delayed weaning and mast cell blockade in pigs. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007, 293(2), 413-421. [CrossRef]

- Jha R.; Berrocoso J.F.D. Dietary fiber and protein fermentation in the intestine of swine and their interactive effects on gut health and on the environment: A review. Anim. Feed Sci. and Technol. 2016, 212, 18-26 (Suppl. 1). [CrossRef]

- Rist V.T.S.; Weiss E.; Eklund M.; Mosenthin R. Impact of dietary protein on microbiota composition and activity in the gastrointestinal tract of piglets in relation to gut health: a review. Animal. 2013, 7(7), 1067-78. [CrossRef]

- Kempen, T A Strategy for Reducing Ammonia in Animal Production. North Carolina State University Swine Nutrient Management Research from 2001; College of Agriculture & Life Sciences, Department of Animal Science, Annual Swine Report 2001. https://porkgateway.org/resource/a-strategy-for-reducing-ammonia-in-animal-production/, November 15, 2025.

- Le Dinh P.; Van der Peet-Schwering C.M.C.; Ogink N.W.M.; Aarnink. A.J.A. Effect of Diet Composition on Excreta Composition and Ammonia Emissions from Growing-Finishing Pigs. Animals 2022, 12(3), 229. [CrossRef]

- Philippe F.; Cabaraux J.; Nicks B. Ammonia emissions from pig houses: Influencing factors and mitigation techniques. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 141(3–4), 245-260. [CrossRef]

- Millet S.; Aluwé M.; Van den Broeke A.; Leen F.; De Boever J.; De Campeneere S. Review: Pork production with maximal nitrogen efficiency. Animal 2018, 12(5), 1060-1067. [CrossRef]

- Hansen M.J.; Nørgaard J.V.; Adamsen A.P.S.; Poulsen H.D. Effect of reduced crude protein on ammonia, methane, and chemical odorants emitted from pig houses. Livest. Sci. 2014, 169, 118-124. [CrossRef]

- Krone J.E.C.; Agyekum A.K.; Borgh M.T.; Hamonic K.; Penner G.B.; Columbus D.A. Characterization of urea transport mechanisms in the intestinal tract of growing pigs. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019, 317(6), 839-844. [CrossRef]

- Lu H.; Su S.; Ajuwom K. Butyrate supplementation to gestating sows and piglets induces muscle and adipose tissue oxidative genes and improves growth performance. Sci. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90 (Suppl. S4), 430–432. [CrossRef]

- Weber T.E.; Kerr B.J. Effect of sodium butyrate on growth performance and response to lipopolysaccharide in weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86(2), 442-450. [CrossRef]

- Feng W.; Wu Y.; Chen G.; Fu S.; Li B.; Huang B.; Wang D.; Wang W.; Liu J. Weaned Piglets and Promotes Tight Junction Protein Expression in Colon in a GPR109A-Dependent Manner. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 47(4), 1617–1629. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H.; Ren E.; Xu R.; Su Y. Transcriptomic Responses Induced in Muscle and Adipose Tissues of Growing Pigs by Intravenous Infusion of Sodium Butyrate. Biology 2021, 10(6), 559. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y.; Yu B.; Yu J.; Zheng P.; Huang Z.; Luo Y.; Luo J.; Mao X.; Yan H.; He J.; Chen D. Butyrate promotes slow-twitch myofiber formation and mitochondrial biogenesis in finishing pigs via inducing specific microRNAs and PGC-1α expression1. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97(8), 3180-3192. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).