Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

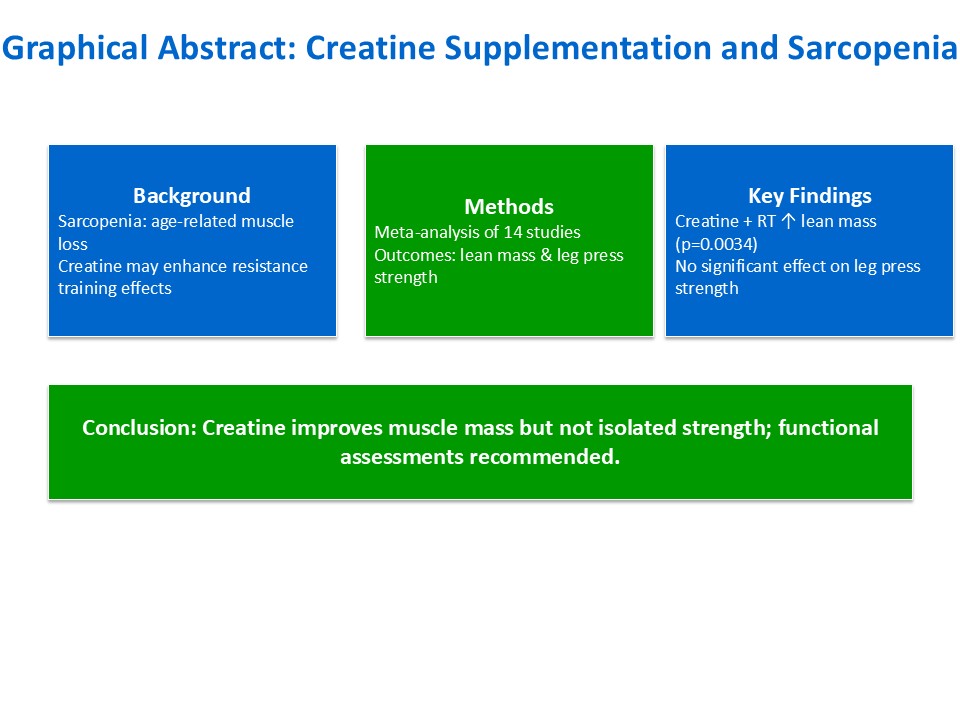

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

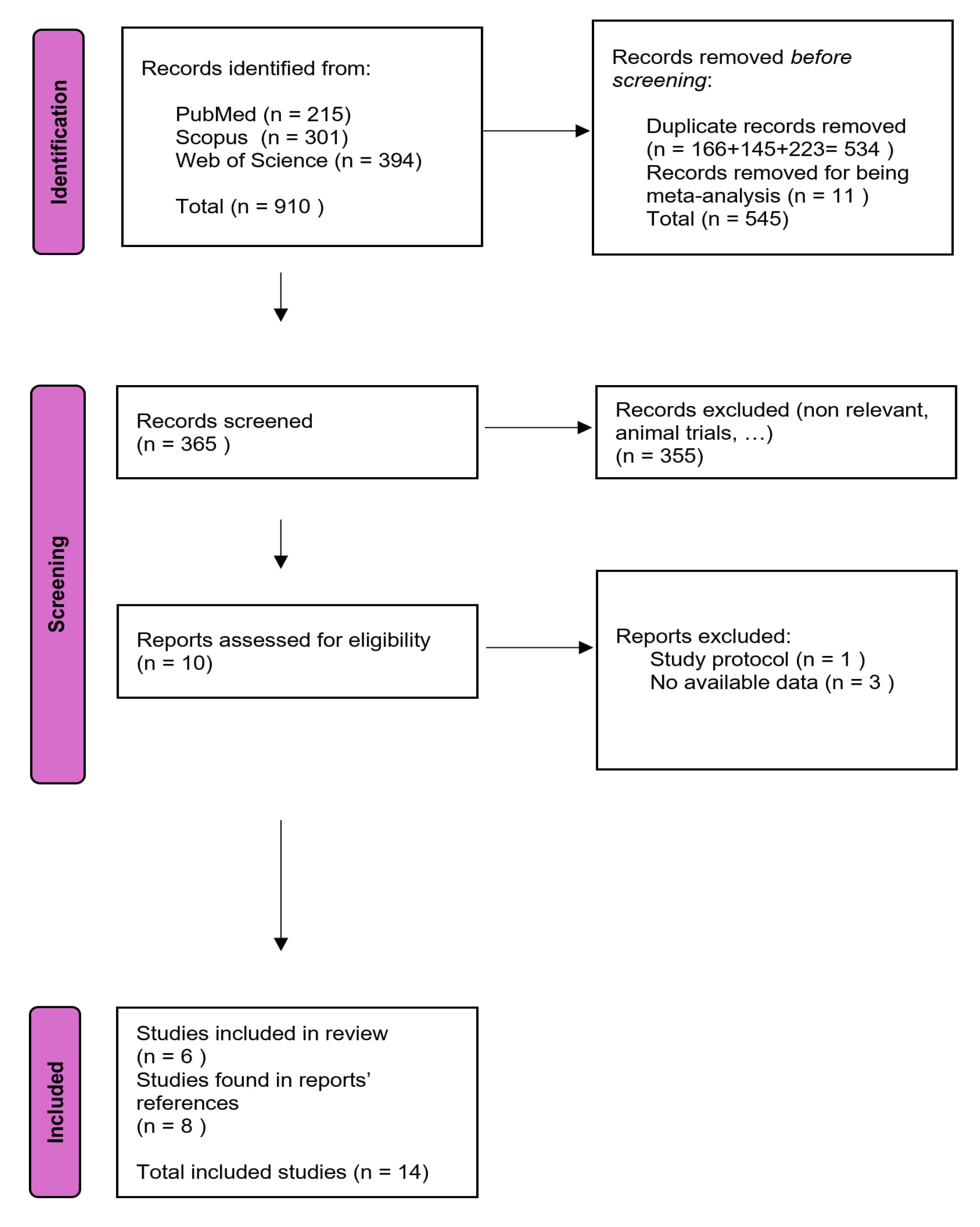

2.1. Search and Selection of Papers

- study population made of elderly or frail individuals

- interventions based on creatine supplementation (with or without exercise)

- presence of a control group

- quantitative outcomes related to muscle mass and/or muscle strength were considered.

- studies done on animals

- protocols not yet implemented

- studies lacking control groups

- studies lacking numerical quantification of outcomes

- studies already classified as meta-analyses

- studies whose research objective did not correspond to ours

- studies that presented confounding factors.

2.2. Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Literature Selection

3.3. Safety

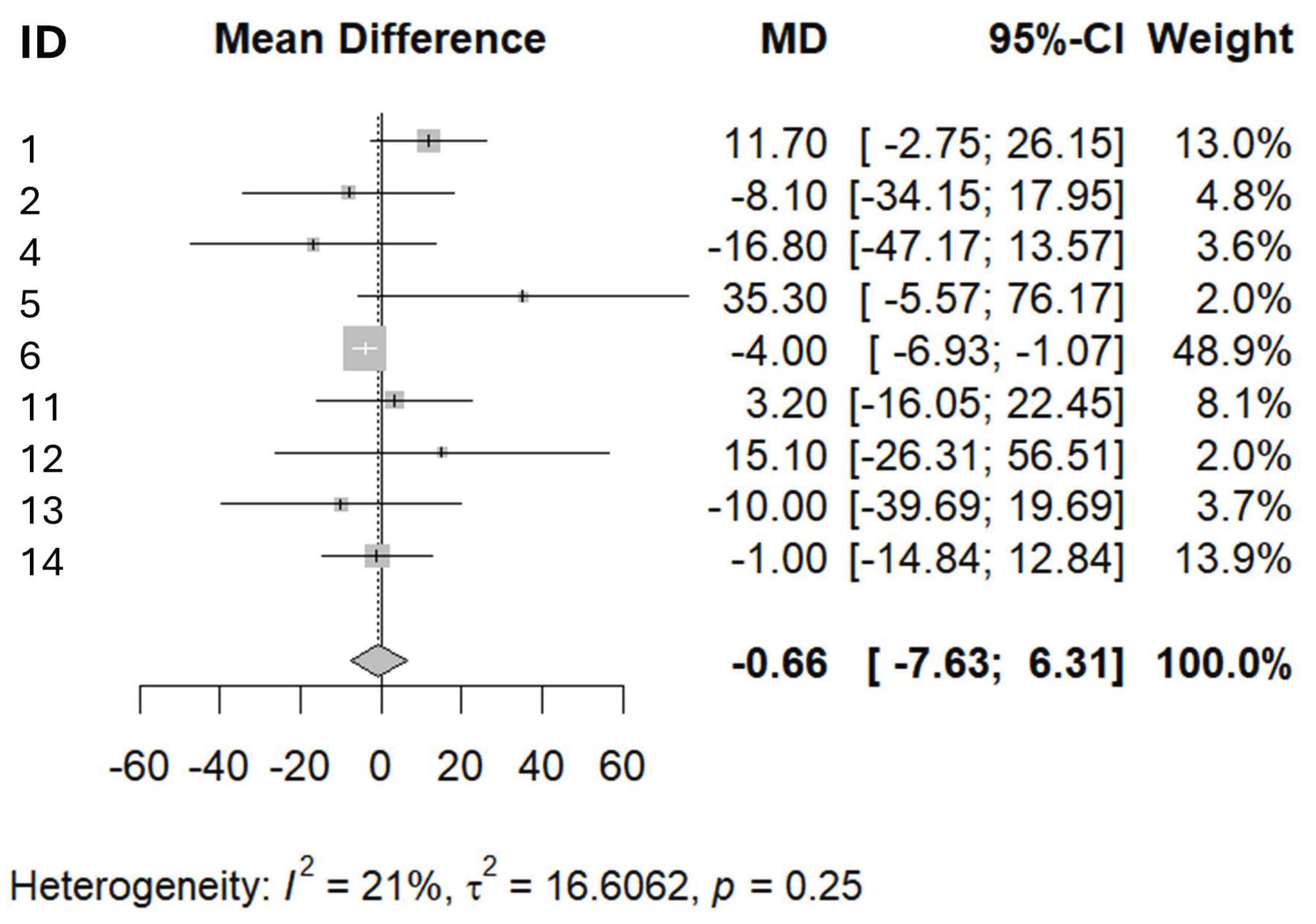

4. Discussion

- The leg press is a single, isolated movement that primarily measures the force generated by the quadriceps and gluteal muscles. However, muscle weakness in sarcopenia is often generalized and affects multiple muscle groups, not just those involved in the leg press. Thus, a patient might perform relatively well on the leg press but still have significant weakness in other muscle groups that are critical for daily activities (e.g., hip flexors, ankle dorsiflexors, core muscles) [31]

- Functional weakness in sarcopenic elderly is best assessed by tasks that mimic daily activities (e.g., chair rise, walking speed, balance tests), not just by isolated muscle force. Leg press force does not capture balance, coordination, or endurance, all of which are crucial for Joint pain, arthritis, neurological disorders, and cardiovascular limitations can all affect leg press performance independently of muscle strength. For example, knee osteoarthritis may limit leg press force due to pain, not muscle weakness per se [32].

- Leg press machines may not be accessible or safe for all frail elderly patients, and results can be influenced by motivation, technique, and familiarity with the equipment. This can lead to underestimation or overestimation of true muscle strength For example, Wilson et al. found that older adults show greater variability in leg press results and less variability in technique, suggesting that rigidity in movement and lack of familiarity with the equipment may negatively impact muscle strength measurements [33].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirk, B.; Cawthon, P.M.; Arai, H.; Ávila-Funes, J.A.; Barazzoni, R.; Bhasin, S.; Binder, E.F.; Bruyere, O.; Cederholm, T.; Chen, L.-K.; et al. The Conceptual Definition of Sarcopenia: Delphi Consensus from the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS). Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Larsson, S.C. Epidemiology of Sarcopenia: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Consequences. Metabolism 2023, 144, 155533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European Consensus on Definition and Diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudart, C.; Zaaria, M.; Pasleau, F.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Bruyère, O. Health Outcomes of Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0169548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, W.; Bruns, C.J. [Sarcopenia as prognostic factor of overall survival in esophageal cancer patients]. Chirurgie (Heidelb) 2022, 93, 1192–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.N.; Park, M.S.; Yang, S.J.; Yoo, H.J.; Kang, H.J.; Song, W.; Seo, J.A.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, N.H.; Baik, S.H.; et al. Prevalence and Determinant Factors of Sarcopenia in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: The Korean Sarcopenic Obesity Study (KSOS). Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1497–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, M.-J.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, W.; Sung, K.W.; Seo, J.-M. Sarcopenia with Decreased Total Psoas Muscle Area in Children with High-Risk Neuroblastoma. Asian J Surg 2024, 47, 2584–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Monaco, M.; Vallero, F.; Di Monaco, R.; Tappero, R. Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Its Association with Osteoporosis in 313 Older Women Following a Hip Fracture. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011, 52, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.; Liperoti, R.; Fusco, D.; Mastropaolo, S.; Quattrociocchi, D.; Proia, A.; Tosato, M.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Sarcopenia and Mortality among Older Nursing Home Residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012, 13, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative Effects of Pre-Operative Isolation on Postoperative Pulmonary Complications after Elective Surgery: An International Prospective Cohort Study. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 1454–1464. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.D.; Rhea, M.R.; Sen, A.; Gordon, P.M. Resistance Exercise for Muscular Strength in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2010, 9, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrusch, M.J.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Chad, K.E.; Davison, K.S.; Burke, D.G. Creatine Supplementation Combined with Resistance Training in Older Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001, 33, 2111–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyss, M.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Creatine and Creatinine Metabolism. Physiol Rev 2000, 80, 1107–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buford, T.W.; Kreider, R.B.; Stout, J.R.; Greenwood, M.; Campbell, B.; Spano, M.; Ziegenfuss, T.; Lopez, H.; Landis, J.; Antonio, J. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Creatine Supplementation and Exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2007, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.C.; Söderlund, K.; Hultman, E. Elevation of Creatine in Resting and Exercised Muscle of Normal Subjects by Creatine Supplementation. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992, 83, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano; B.; Macedo; R, A.; Alves; R, C.; Roschel; H.; Benatti; B, F.; et al. Creatine Supplementation and Resistance Training in Vulnerable Older Women: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Experimental Gerontology 2014. [CrossRef]

- Johannsmeyer; S.; Candow; G, D.; Brahms; M, C.; Michel; D.; Zello; A, G. Effect of Creatine Supplementation and Drop-Set Resistance Training in Untrained Aging Adults. Experimental Gerontology 2016. [CrossRef]

- Rawson; S, E. ; Wehnert; L, M.; Clarkson; M, P. Effects of 30 Days of Creatine Ingestion in Older Men. European Journal of Applied Physiology 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.L.; Botelho, P.B.; Carneiro, J.A.; Mota, J.F. Impact of Creatine Supplementation in Combination with Resistance Training on Lean Mass in the Elderly. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candow, D.G.; Vogt, E.; Johannsmeyer, S.; Forbes, S.C.; Farthing, J.P. Strategic Creatine Supplementation and Resistance Training in Healthy Older Adults. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2015, 40, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschel; H.; Hayashi; P, A.; Fernandes; L, A.; Jambassi-Filho; C, J.; Hevia-Larraín; V.; et al. Supplement-Based Nutritional Strategies to Tackle Frailty: A Multifactorial, Double-Blind, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clinical Nutrition 2021. [CrossRef]

- Aguiar; F, A. ; Januário; B, R.S.; Junior, P.; R.; Gerage; M, A.; Pina; C, F.L.; et al. Long-Term Creatine Supplementation Improves Muscular Performance during Resistance Training in Older Women. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrusch, M.J.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Chad, K.E.; Davison, K.S.; Burke, D.G. Creatine Supplementation Combined with Resistance Training in Older Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001, 33, 2111–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliot, K.A.; Knehans, A.W.; Bemben, D.A.; Witten, M.S.; Carter, J.; Bemben, M.G. The Effects of Creatine and Whey Protein Supplementation on Body Composition in Men Aged 48 to 72 Years during Resistance Training. J Nutr Health Aging 2008, 12, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijnde; O, B.; Leemputte, V.; M.; Goris; M.; Labarque; V.; Taes; Y.; et al. Effects of Creatine Supplementation and Exercise Training on Fitness in Men 55–75 Yr Old. Journal of Applied Physiology 2003. [CrossRef]

- Gotshalk; A, L. ; Kraemer; J, W.; Mendonca; G, M.A.; Vingren; L, J.; Kenny; M, A.; et al. Creatine Supplementation Improves Muscular Performance in Older Women. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotshalk; A, L.; Volek; S, J.; Staron; S, R.; Denegar; R, C.; Hagerman; C, F.; et al. Creatine Supplementation Improves Muscular Performance in Older Men. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2002. [CrossRef]

- Candow; G, D.; Little; P, J.; Chilibeck; D, P.; Abeysekara; S.; Zello; A, G.; et al. Low-Dose Creatine Combined with Protein during Resistance Training in Older Men. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2008. [CrossRef]

- Brose, A.; Parise, G.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Creatine Supplementation Enhances Isometric Strength and Body Composition Improvements Following Strength Exercise Training in Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003, 58, B11–B19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seene, T.; Kaasik, P. Muscle Weakness in the Elderly: Role of Sarcopenia, Dynapenia, and Possibilities for Rehabilitation. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2012, 9, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taking Care of Elderly Patients with Muscle Weakness Available online:. Available online: https://www.care365.care/resources/taking-care-elderly-patients-muscle-weakness (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Wilson, C.; Perkin, O.J.; McGuigan, M.P.; Stokes, K.A. The Effect of Age on Technique Variability and Outcome Variability during a Leg Press. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0163764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number assigned to paper for data analysis | Number assigned to paper in the bibliography at the end of this paper | Paper (citation) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 | Gualano; B.; Macedo; R, A.; Alves; R, C.; Roschel; H.; Benatti; B, F.; et al. Creatine Supplementation and Resistance Training in Vulnerable Older Women: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Experimental Gerontology 2014, |

| 2 | 18 | Johannsmeyer; S.; Candow; G, D.; Brahms; M, C.; Michel; D.; Zello; A, G. Effect of Creatine Supplementation and Drop-Set Resistance Training in Untrained Aging Adults. Experimental Gerontology 2016, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2016.08.005. |

| 3 | 19 | Rawson; S, E.; Wehnert; L, M.; Clarkson; M, P. Effects of 30 Days of Creatine Ingestion in Older Men. European Journal of Applied Physiology 1999, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s004210050570. |

| 4 | 20 | Pinto, C.L.; Botelho, P.B.; Carneiro, J.A.; Mota, J.F. Impact of Creatine Supplementation in Combination with Resistance Training on Lean Mass in the Elderly. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 413–421, doi:10.1002/jcsm.12094. |

| 5 | 21 | Candow, D.G.; Vogt, E.; Johannsmeyer, S.; Forbes, S.C.; Farthing, J.P. Strategic Creatine Supplementation and Resistance Training in Healthy Older Adults. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2015, 40, 689–694, doi:10.1139/apnm-2014-0498. |

| 6 | 22 | Roschel; H.; Hayashi; P, A.; Fernandes; L, A.; Jambassi-Filho; C, J.; Hevia-Larraín; V.; et al. Supplement-Based Nutritional Strategies to Tackle Frailty: A Multifactorial, Double-Blind, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clinical Nutrition 2021, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.06.024. |

| 7 | 23 | Aguiar; F, A.; Januário; B, R.S.; Junior, P.; R.; Gerage; M, A.; Pina; C, F.L.; et al. Long-Term Creatine Supplementation Improves Muscular Performance during Resistance Training in Older Women. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2013, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-012-2514-6. |

| 8 | 24 | Chrusch, M.J.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Chad, K.E.; Davison, K.S.; Burke, D.G. Creatine Supplementation Combined with Resistance Training in Older Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001, 33, 2111–2117, doi:10.1097/00005768-200112000-00021. |

| 9 | 25 | Eliot, K.A.; Knehans, A.W.; Bemben, D.A.; Witten, M.S.; Carter, J.; Bemben, M.G. The Effects of Creatine and Whey Protein Supplementation on Body Composition in Men Aged 48 to 72 Years during Resistance Training. J Nutr Health Aging 2008, 12, 208–212, doi:10.1007/BF02982622. |

| 10 | 26 | Eijnde; O, B.; Leemputte, V.; M.; Goris; M.; Labarque; V.; Taes; Y.; et al. Effects of Creatine Supplementation and Exercise Training on Fitness in Men 55–75 Yr Old. Journal of Applied Physiology 2003, doi:https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00891.2002. |

| 11 | 27 | Gotshalk; A, L.; Kraemer; J, W.; Mendonca; G, M.A.; Vingren; L, J.; Kenny; M, A.; et al. Creatine Supplementation Improves Muscular Performance in Older Women. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2008, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-007-0580-y. |

| 12 | 28 | Gotshalk; A, L.; Volek; S, J.; Staron; S, R.; Denegar; R, C.; Hagerman; C, F.; et al. Creatine Supplementation Improves Muscular Performance in Older Men. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2002, doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200203000-00026. |

| 13 | 29 | Candow; G, D.; Little; P, J.; Chilibeck; D, P.; Abeysekara; S.; Zello; A, G.; et al. Low-Dose Creatine Combined with Protein during Resistance Training in Older Men. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2008, doi:https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318176b310. |

| 14 | 30 | Brose, A.; Parise, G.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Creatine Supplementation Enhances Isometric Strength and Body Composition Improvements Following Strength Exercise Training in Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003, 58, B11–B19, doi:10.1093/gerona/58.1.B11 |

| Paper number (assigned for data analysis) | Treatment group |

Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Total N | Males (N) | Age, years | Total N | Males (N) | Age, years |

| 1 | 30 | 0 | ~72 | 30 | 0 | ~72 |

| 2 | 14 | 7 | 58.0 ± 3.0 | 17 | 10 | 57.6 ± 5.0 |

| 3 | 10 | 10 | 60–82 | 10 | 10 | 60–82 |

| 4 | 13 | NA | 66.5 ± 4.5 | 14 | NA | 67.2 ± 5.1 |

| 5 | 27 | 14 | 50–71 | 12 | 3 | 50–71 |

| 6 | ~50 | 0 | 72 ± 6 | ~50 | 0 | 72 ± 6 |

| 7 | 9 | 0 | 64.9 ± 5.0 | 9 | 0 | 64.9 ± 5.0 |

| 8 | 16 | 16 | 70.4 ± 1.6 | 14 | 14 | 71.1 ± 1.8 |

| 9 | 21 | 21 | 48–72 | 10 | 10 | 48–72 |

| 10 | 23 | 23 | 55–75 | 23 | 23 | 55–75 |

| 11 | 15 | 0 | 63.3 ± 1.2 | 12 | 0 | 63.0 ± 1.1 |

| 12 | 10 | 10 | 59–72 | 8 | 8 | 59–72 |

| 13 | 23 | 23 | 59–77 | 12 | 12 | 59–77 |

| 14 | 14 | 8 | >65 | 14 | 7 | >65 |

| NA = not available | ||||||

| Paper number (assigned for data analysis) | Creatine dose (as per protocol) | Additional supplements | Duration, weeks | Physical exercise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 g/day for 5 days, then 5 g/day | 0.1 g/kg/day maltodextrin | 24 | 2x/week RT |

| 2 | 0.1 g/kg/day | 0.1g/kg/day of maltodextrin | 12 | RT |

| 3 | 5 g x 4/day x 10 days, then 4g/day x 20 days | 7 g dextrose x 4/day x 10 days, then 6.8g dextrose x 20 days | 4.3 | Not specified |

| 4 | 5 g/day | 100 g of lemon-flavoured maltodextrin (on training days only) | 12 | 3x/week RT |

| 5 | 0.1 g/kg occasional (2x15g/day) | Maltodextrin from corn starch (2x15g/day) | 32 | RT |

| 6 | 3g x2/day | either whey (15g x2/day) or placebo (corn starch) (15g x2/day) |

16 | RT |

| 7 | 5 g/day | CHO drink | 12 | 3x/week RT |

| 8 | 0.3 g/kg/day x 5days, 0.07g/kg/day thereafter | sucrose-flour mixture to mask the substance | 12 | 3x/week RT |

| 9 | Loading phase: 7g/day Maintenance phase: 5g/day (both only on training days) |

Some subjects received 35 g/day wheat proteins | 1+14 (loading+treatment phases) | 3x/week RT |

| 10 | 5g/ day | none | 24 (6 months) | 2-3 sessions/ week |

| 11 | 0.3 g/kg/day x 7 days |

none | 1 week supplementation protocol | familiarization tests, but the training program after that is not specified |

| 12 | 0.3 g/kg/day x 7days | none | 1 | 3x/week RT |

| 13 | 0.1 g·kg−1/day only on training days | Proteins, 0.1 g·kg−1/day only on training days | 10 | 3 days/week |

| 14 | 5g/day | 2g dextrose | 14 | 3x week RT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).